Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

North American Free Trade Agreement

NAAEE conducts an annual conference and produces

publications, including a member newsletter, the Environ-

mental Communicator, and a Directory of Environmental Edu-

cators. It also operates a Skills Bank and numerous programs.

Several of these programs focus on community-based activi-

ties. The VINE (Volunteer-led Investigations of Neighbor-

hood Ecology) Network promotes programs using volun-

teers to lead children in explorations of the ecology of their

urban neighborhoods. The Urban Leadership Collaboratives

Program aims to develop collaborative environmental educa-

tion programs in cities. The Environmental Issues Forums

(EIF) Program assists students and adults in working with

controversial environmental issues in their communities and

nationally.

Other NAAEE programs have a wider focus. The

NAAEE Training and Professional Development Institute

offers workshops and training events on such topics as fun-

draising and long-range planning, as well as courses for

educators from developing countries in cooperation with

United States Assistance for International Development

(USAID) and the Smithsonian Institute. The Environmen-

tal Education and Training Partnership (EETAP), under a

U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

grant, coordinates

a consortium of 18 environmental education organizations

that promote training. The NAAEE Policy Institute aims to

develop standards for environmental education. Additional

NAAEE activities include writing reports to the United

States Congress on environmental education issues, re-

viewing proposals submitted for funding under the National

Environmental Education Act of 1990, and testifying to

support environmental education legislation and innovative

programs. Internationally, the organization has helped to

establish environmental education centers in Moscow and

Kiev and a program in Thailand, and has assisted with

developing educational materials in Sri Lanka.

NAAEE maintains four member sections that repre-

sent different contexts of environmental education and con-

duct individual activities:

Conservation

Education Section,

Elementary and Secondary Education Section, Environ-

mental Studies Section, and Nonformal Section (for mem-

bers working outside of formal school settings).

In 1996, the Conservation Education Association was

incorporated into NAAEE.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

North American Association for Environmental Education, 410 Tarvin

Road, Rock Spring, GA USA 30739 (706) 764-2926, Fax: (706) 764-

2094, Email: email@naaee.org, <http://www.naaee.org>

987

North American Free Trade

Agreement

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is

an international trade agreement among the United States,

Canada, and Mexico that became effective on January 1,

1994. Pursuant to NAFTA most tariffs among the three

countries are being phased out over a period of fifteen years.

In addition, the agreement liberalizes rules regulating invest-

ment by United States and Canadian firms in Mexico.

NAFTA includes side agreements on

environment

, labor,

and dealing with import surges. Controversy surrounding

the adoption of NAFTA by the United States in 1993 in-

cluded issues related to trade, employment, immigration,

labor law, and environmental protection. And, several years

after its effective date, observers continue to debate the wis-

dom of the agreement. The economic slowdown in the

United States that began in 2001 has intensified public de-

bate over NAFTA’s provisions.

While NAFTA’s adoption was being debated, envi-

ronmentalists were divided in response to whether or not

we are environmentally better off with NAFTA. Thus, its

adoption was opposed by some environmental groups and

supported by others. Major groups opposing it included the

Sierra Club

,

Greenpeace

, the United States Public Interest

Research Group (U.S. PIRG), Citizen’s Action, Public Citi-

zen: the Clean Water Fund, and the

Student Environmen-

tal Action Coalition

. NAFTA was supported, however, by

a coalition of major environmental organizations including

the

National Wildlife Federation

, the

World Wildlife

Fund

, the

National Audubon Society

, the

Environmental

Defense

Council, the

Natural Resources Defense Council

,

Conservation International

, and

Defenders of Wildlife

,

and

the Nature Conservancy

. Such division among envi-

ronmentalists with respect to NAFTA and its consequences

for the environment continues through the present day.

NAFTA’s provisions

NAFTA is first and overall a trade agreement. Thus,

the majority of the provisions within its over 1,200 pages

focus on elimination of barriers to trade. Over a period of

fifteen years, beginning on January 1, 1994, tariffs on over

9,000 products traded among the United States, Mexico,

and Canada are being phased out. In addition, other “non-

tariff” barriers to trade are being eased or eliminated.

Elimination of tariffs

Tariffs on approximately 4,500 products traded among

the NAFTA parties were eliminated on January 1, 1994,

and by 1999 tariffs will remain on only about 3,000 products.

The remainder will be phased out by the year 2009. The

period during which tariffs are phased out gives producers

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

North American Free Trade Agreement

time to adjust gradually to competition from products of

other NAFTA countries. Those products for which tariffs

are being phased out gradually are labeled “sensitive prod-

ucts” and include many farm commodities. For example, to

protect Mexican producers, corn and dry beans are being

protected through a “phase-out” period for tariffs. Producers

in the United States are being protected with respect to

sugar, asparagus, orange juice concentrate, and melons.

The

automobile

industry is another area for which

NAFTA includes special provisions. NAFTA sets out for-

mulas requiring a certain minimum percentage of content

from North America (the three NAFTA parties) for an

automobile to qualify for duty-free treatment. By 2002, auto-

mobiles must contain 62.5% North American content to

qualify for such treatment.

The fact that Mexico agreed to abolish tariffs in certain

sectors of the economy is important to U.S. investors. For

example, telecommunications in Mexico are underdevel-

oped, and that country has a poor quality telephone system.

By 1998, Mexico phased out all tariffs on telecommunica-

tions service and equipment.

Removal of non-tariff barriers to trade

NAFTA removes certain barriers to trade that are not

in the form of tariffs. For example, NAFTA allows financial

service providers of a NAFTA country to establish banking,

insurance, securities operations, and other types of financial

services in another NAFTA country. NAFTA also provides

U.S. and Canadian firms with greater access to Mexico’s

energy markets. Under NAFTA, U.S. and Canadian firms

can sell products to PEMEX, Mexico’s federally owned

petroleum

company. In addition, Mexico has opened opera-

tion of self-generation,

cogeneration

, and independent

power plants

in Mexico to investment by U.S. or Cana-

dian firms.

Transportation

has also been facilitated by NAFTA.

Since 1995, U.S., Mexican, and Canadian firms have been

allowed to establish cross-border routes. In the early summer

of 2002, the United States signed an agreement allowing

Mexican trucks to travel throughout the United States. The

long-term effects of transportation agreements are difficult

to evaluate, however.

Statistics

for 2001 indicate that truck

crossings into the United States from Canada and Mexico

fell by 4.2% from their level in 2000. This decrease represents

the first annual decline since the agreement among the three

countries took effect in 1994. On the other hand, this de-

crease may be only temporary, as it reflects the impact of

tightened border security measures following the terrorist

attacks of September 11, 2001.

NAFTA does not create a common market for move-

ment of labor, but it does provide for temporary entry of

business people from one NAFTA country into another.

The four different categories for such movement of workers

988

include business visitors in marketing, sales and related activ-

ities, traders and investors, specified kinds of intracompany

transfers, and specified professionals meeting educational or

special knowledge requirements.

Dispute resolution

Administration of NAFTA is handled by a Commis-

sion of cabinet-level officers each of whom has been ap-

pointed by one of the NAFTA countries. The Commission

includes a Secretary, who is the chief administrator.

The process for resolution of disputes under NAFTA

is cumbersome and time-consuming. When a dispute arises

with respect to a NAFTA country’s rights under the

agreement, a consultation can be requested. If the consulta-

tion does not resolve the dispute, the Commission will seek

to resolve the dispute through alternative dispute resolution

procedures. If those are unsuccessful, the complaining coun-

try can request the establishment of a five member arbitration

panel which will recommend solutions, monitor results, and,

if necessary, impose sanctions.

NAFTA’s side agreements

In areas involving labor law and environmental protec-

tion, NAFTA’s provisions are limited.

Labor side agreement

The North American Agreement on Labor Coopera-

tion, also known as the “Side Agreement on Labor” or

“Labor Side Agreement,” was negotiated in response to con-

cerns that NAFTA itself did little to protect workers in

Mexico, the United States, and Canada. In the Labor Side

Agreement, the three countries articulate their desire to

improve labor conditions and encourage compliance with

labor laws. Each party agrees to enforce its own labor laws,

but new laws protecting workers are not established. The

Agreement establishes a multiple-step process for dealing

with instances in which a NAFTA country has exhibited a

“consistent pattern of ... failure to effectively enforce its own

occupational safety and health, child labor, or minimum

wage labor standards.” If the three NAFTA parties cannot

agree to a resolution, then a committee of experts can be

convened to assist in resolving the dispute.

Seven years after NAFTA was enacted, a number of

observers consider its side agreement on labor a conspicuous

failure that protected international investors at the expense

of ordinary workers in all three countries. In the United

States, NAFTA led to the elimination of 800,000 manufac-

turing jobs. Contrary to predictions in 1995, the agreement

did not result in an increased trade surplus with Mexico,

but the reverse. As manufacturing jobs disappeared, workers

in the United States were downscaled to lower-paying, less-

secure services jobs. Employers’ threats to move production

to Mexico became a powerful weapon for undercutting work-

ers’ bargaining power. In Canada, a similar process has

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

North American Free Trade Agreement

brought about a decline in stable full-time employment as

well as damaging Canada’s social safety net.

Mexican workers have not benefited from this redistri-

bution of jobs. While some manufacturing jobs did move

to Mexico, they are largely confined to maquiladoras just

across the border. Maquiladoras are factories that assemble

electronics equipment and small appliances for export.

Workers are typically paid low wages and have few rights.

The maquiladoras are isolated from the rest of the Mexican

economy and contribute very little to its development. In

addition, the expiration of the duty-free status of maquiladora

products in 2001 means that these factories are less competi-

tive in the global market. As a result, many foreign compa-

nies began to shut down their plants in Mexico in 2002.

Environmental side agreement

The North American Agreement on Environmental

Cooperation, also known as the “Environmental Side

Agreement,” was adopted along with the Labor Side

Agreement and was negotiated in response to concerns that

the body of NAFTA did little to protect the environment.

In the Environmental Side Agreement, the three parties

articulate their desire to promote environmental concerns

without harming the economy, and promote open public

discussion of environmental issues. As in the Labor Side

Agreement with respect to labor laws, each party agrees to

enforce its own environmental laws, but no new environmen-

tal laws are made. The agreement establishes a

Commission

for Environmental Cooperation

(CEC) that includes a

Secretariat and a Council, which is charged with implement-

ing the side agreement.

The Environmental Side Agreement allows a

nongov-

ernmental organization

(such as an environmental group)

or a private citizen to file a complaint with the Commission

asserting that a NAFTA country “has shown a persistent

pattern of failure to effectively enforce its environmental

laws.” Thus, such groups and individuals can serve as watch-

dogs for the Commission.

The Environmental Side Agreement allows a NAFTA

country to request a consultation with a second NAFTA

country regarding that second country’s persistent pattern

of failure to enforce its environmental laws. If a resolution

is not reached as a result of the consultation, a party can

request that the Council meet. If the Council is unable to

resolve the dispute, it can convene an arbitration panel, which

will study the dispute and issue a report. After the parties

submit comments, the report is made final. The parties are

given an opportunity to reach their own action plan, but, if

there is no such agreement, the panel can be reconvened to

establish a plan. If an imposed fine is not paid, as under the

Labor Side Agreement, NAFTA benefits can be suspended.

989

Environmental consequences of NAFTA

Environmentalists share many concerns with respect

to NAFTA, three of which will be introduced here. First,

environmentalists are concerned that NAFTA represents a

threat to the sovereignty of the United States because U.S.

environmental laws may be challenged under NAFTA. For

example, it is feared that the U.S. will not be allowed to

refuse entry of goods produced in Mexico even if those goods

are produced using production methods that do not meet

U.S. environmental, health, or food safety standards. This

is based on U.S. experience under the General Agreement

on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) when a GATT panel declared

that a U.S. embargo on Mexican tuna caught using methods

violating the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act was ille-

gal. The GATT panel held that products must be treated

equally regardless of how they are produced.

Ironically, the first major challenge to national sover-

eignty came from Canadian corporations. A Canadian con-

glomerate known as Methanex made use of a little-known

section of NAFTA known as Chapter 11 to sue the state

of California, demanding financial compensation for loss of

market share. Methanex is the world’s largest producer of

the key ingredient in a

gasoline

additive known as MBTE,

a substance that California ordered to be phased out after

it began to contaminate public water systems in 1995. A

phrase in Chapter 11 written to protect investors from having

their property seized by foreign governments has been in-

voked to justify corporate lawsuits against state and federal

environmental regulations. Other examples of cross-border

lawsuits include another Canadian company’s suit against

the state of Mississippi, and a United States corporation’s

suit against the government of Canada for banning another

gasoline additive.

Second, environmentalists label Mexico as a “pollution

haven” for U.S. businesses seeking less-stringent enforce-

ment of environmental laws than that which occurs in the

United States. Concerns about

environmental degrada-

tion

in Mexico due to increased industrialization do seem

to be valid. Environmentalists, business leaders, and govern-

ment officials from the three NAFTA countries agree that

environmental contamination had reached serious propor-

tions in northern Mexico in the decades preceding the 1994

effective date of NAFTA. Such contamination continues to

spread as Mexico becomes more heavily industrialized under

NAFTA. A report published by the CEC in 2002 indicates

that chemical producers accounted for the largest amount

of pollutants.

On paper, Mexico has environmental laws that parallel

many, but not all, of the federal environmental laws of the

United States. Mexico’s 1988 Co

´

digo Ecolo

´

gico, known in

English as the “General Ecology Law,” is a comprehensive

statute addressing

pollution

, resource

conservation

, and

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

North American Water and Power Alliance

environmental enforcement

. Often, however, Mexico’s

environmental laws are not enforced. This lack of enforce-

ment can be attributed to a variety of reasons. For one thing,

the statutes are relatively new, dating only from 1988, and

regulations have not been made to supplement the laws.

Also, Mexico is a country in which people distrust the legal

system and where there are widespread violations of law in

various areas (not limited to environmental laws.) Noncom-

pliance with law is accepted and expected in many areas in

Mexico. Since Mexico is a developing country striving to

implement open, democratic systems of government, this

casual attitude toward legislation is a significant hurdle to

be overcome throughout Mexican society.

Third, Mexico is a debt-ridden country that continues

to struggle with periodic financial crises. Thus, even if Mexi-

co’s leaders were convinced that there should be vigorous

enforcement of environmental laws and regulations, Mexico

lacks money for such enforcement. In connection with its

lack of capital, Mexico lacks technology and it lacks infra-

structure such as

water treatment

plants, sewage systems,

and waste disposal facilities. For example, as of mid-1997,

in the entire country of Mexico, there was only one facility

licensed for disposal of hazardous wastes. Lacking a place

to dispose of toxics and knowing the low

probability

of

being cited by government officials for violations, most com-

panies and individuals continue to dump hazardous wastes

into Mexico’s waters and air and onto its land. Mexico’s

citizens do not want to live with the contamination any

more than we do in the United States. They feel, however,

that they are less empowered to “do something about it”

than we are as U.S. citizens.

Looking ahead

NAFTA represents a significant turning point in in-

ternational law, because it recognizes explicitly that trade

policy and

environmental policy

are inextricably linked.

Through its Environmental Side Agreement, it establishes

mechanisms for dealing with citizens’ concerns and for deal-

ing with that party or country that systematically fails to

enforce its own environmental laws. However, NAFTA’s

environmental provisions provide only a foundation upon

which citizens and governments of the U.S., Mexico, and

Canada must build if the environment of North America is to

be protected from the often detrimental effects of expanded

trade. As of 2002, those detrimental effects have been suffi-

ciently obvious to produce a growing chorus of criticisms of

NAFTA. Proposals to create a Free Trade Area of the

Americas (FTAA), which would represent an extension of

NAFTA’s provisions to every country in Central America,

South America, and the Caribbean except Cuba, have pro-

voked widespread protest from a variety of environmental

and social justice organizations.

[Rebecca J. Frey, Ph.D.]

990

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bello, J. H., A. F. Holmer, and J. J. Norton, eds. NAFTA: a New Frontier

in International Trade and Investment in the Americas. American Bar Associa-

tion Section of International Law & Practice, 1994.

Hufbauer, G. C., and J. J. Schott, NAFTA: An Assessment. The Institute

for International Economics, 1993.

MacArthur, John R. The Selling of Free Trade: NAFTA, Washington, and

the Subversion of American Democracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Gir-

oux, 2000.

Moran, R. T., and J. Abbott, NAFTA: Managing the Cultural Differences.

Gulf Publishing Company, 1994.

P

ERIODICALS

Franz, Neil. “Report Tracks NAFTA Region Emissions.” Chemical Week

164 (June 5, 2002): 39.

Knight, Danielle. “Environment Groups Organise Against NAFTA Rules.”

International Third World Press Service (IPS), September 8, 2000.

Smith, Geri. “The Decline of the Maquiladora.” Business Week. April

29, 2002.

Stenzel, P.L. “Can NAFTA’s Environmental Provisions Promote Sustain-

able Development?” 59 Albany Law Review 59 (1995): 423–480.

O

THER

Economic Policy Institute. NAFTA at Seven. Washington, DC: Economic

Policy Institute, 2001.

Global Exchange. Documentary Exposing How NAFTA’s Chapter 11 Has

Become Private Justice for Foreign Companies. January 7, 2002.

Williams, Edward J. The Maquiladora Industry and Environmental Degrada-

tion in the United States–Mexican Borderlands. Paper presented at the annual

meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, Washington, DC,

September 1995.

O

RGANIZATIONS

NAFTA Information Center, Texas A&M International University,

College of Business Administration, 5201 University Blvd., Laredo, TX

USA 78041-1900 (956)326-2550, Fax: (956)326-2544, Email:

nafta@tamiu.edu, <www.tamiu.edu/coba/usmtr/>

North American Water and Power

Alliance

Numerous schemes were suggested in the 1960s to accom-

plish large-scale water transfers between major basins in

North America, and one of the best known is the North

American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA). The

plan was devised by the Ralph M. Parson Company of Los

Angeles “to divert 36 trillion gallons of water (per year) from

the Yukon River in Alaska (through the Great Bear and

Great Slave Lakes) southward to 33 states, seven Canadian

provinces, and northern Mexico.”

The proposed NAWAPA system would bring water

in immense quantities from western Canada and Alaska

through the plains and

desert

states all the way down to

the Rio Grande

watershed

and into the Northern Sonora

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Northern spotted owl

and Chihuahua provinces of Mexico. The Rocky Mountain

Trench, Peace River, Great Slave Lake, Lesser Slave Lake,

North Saskatchewan River, Columbia River, Lake Winni-

peg,

Hudson River

, James Bay, and numerous tributaries

are part of the proposed NAWAPA feeder system designed

to channel water from Canada to Mexico.

A second feeder system in the plan would channel

large quantities of water into the western portion of Lake

Superior. This influx of water would wash the pollutants

dumped into the

Great Lakes

out into the Atlantic Ocean.

It would also boost the capacity of the area for generating

hydroelectricity.

The NAWAPA plan was also designed to develop

hydroelectric plants within northern Quebec and Ontario

which would produce power that would be diverted to the

United States. The

James Bay hydropower project

in

Quebec was completed in the early 1970s. It flooded an area

4,250 mi

2

(11,000 km

2

), and 90% of its power goes directly

into the Northeastern United States and Ohio. The James

Bay II Project in Ontario will eventually incorporate over

80

dams

, divert three major rivers, and flood traditional

Cree land. The majority of its hydroelectric output will also

go to the United States.

Proponents of inter-basin transfers tend to focus on the

impending water shortages in the western and southwestern

United States. In the Great Plains, the

Ogallala Aquifer

is rapidly being depleted. The Black Mesa

water table

is

almost exhausted, due to the excessive quantities of water

used in mining operations, and California has been consist-

ently unable to meet the needs of both its industries and its

population. Supporters of NAWAPA have long argued that

this plan is the only way the nation can solve these problems.

On February 22, 1965, Newsweek hailed the NAWAPA

plan as “the greatest, the most colossal, stupendous, super-

splendificent public works project in history.”

NAWAPA was described as “a monstrous concept—

a diabolical thesis” by a former chairperson of the

Interna-

tional Joint Commission

. Much of the opposition to the

plan in the 1960s was nationalist rather than environmental

in character: The plans were viewed as an attempt to appro-

priate Canadian resources. Today, many people are asking

whether it is necessary or even right to hydrologically re-

engineer the ecosystems of North America in order to meet

the water needs of the United States. Environmentalists

point out that entire ecosystems in many western states have

already been disrupted by various water projects. They argue

that it is time to investigate other methods, such as

conser-

vation

, which would bring water consumption to levels

sustainable by the watersheds of the plains and deserts.

[Debra Glidden]

991

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Higgins, J. “Hydro-Quebec and Native People.” Cultural Survival Quarterly

11 (1987).

Reisner, M. Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water.

New York: Viking Press, 1986.

Royal Society of Canada. Water Resources of Canada. Ottawa: Royal Society

of Canada, 1968.

Welsh, F. How to Create a Water Crisis. Boulder: Johnson Publishing, 1985.

P

ERIODICALS

Canadian Council of Resource Ministers. Water Diversion Proposals of North

America. Ottawa: Canadian Council of Resource Ministers, 1968.

Northern spotted owl

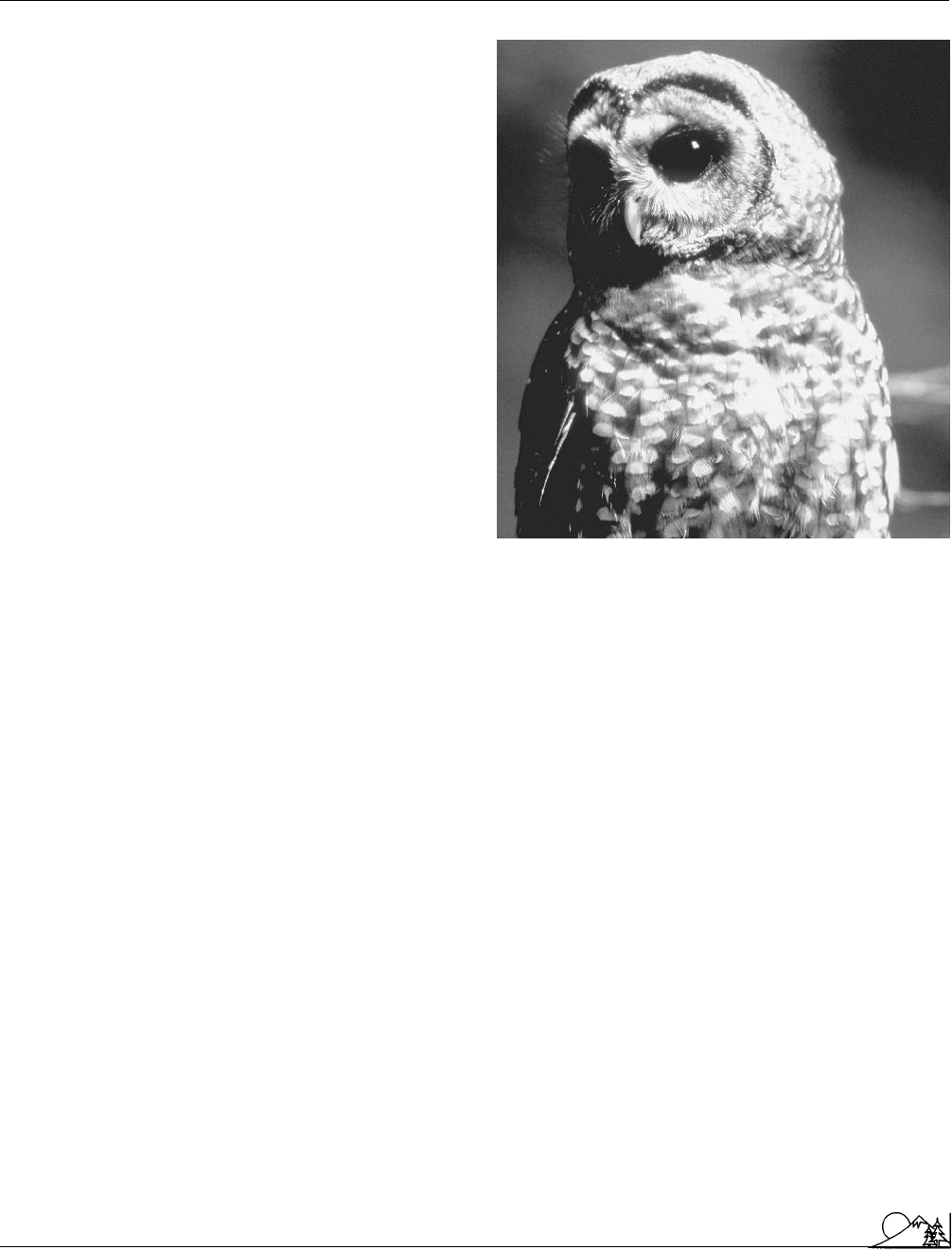

The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina)isone

of three subspecies of the spotted owl (Strix occidentalis).

Adults are brown, irregularly spotted with white or light

brown spots. The face is round with dark brown eyes and

a dull yellow colored bill. They are 16–19 in (41–48 cm)

long and have wing spans of about 42 in (107 cm). The

average weight of a male is 1.2 lb (544 g), whereas the

average female weighs 1.4 lb (635 g).

This subspecies of the spotted owl is found only in

the southwestern portion of British Columbia, western

Washington, western Oregon, and the western coastal region

of California south to the San Francisco Bay. Occasionally

the bird can be found on the eastern slopes of the Cascade

Mountains in Washington and Oregon. It is estimated that

there are about 3,000–5,000 individuals of this subspecies.

The other two subspecies of spotted owl are the Cali-

fornia spotted owl (S. o. occidentalis) found in the coastal

ranges and western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains

from Tehama to San Diego counties, and the Mexican spot-

ted owl (S. o. lucida) found from northern Arizona, south-

eastern Utah, southwestern Colorado, south through west-

ern Texas to central Mexico.

It is thought that spotted owls mate for life and are

monogamous. Breeding does not occur until the birds are

two to three years of age. The typical clutch size is two, but

sometimes as many as four eggs are laid in March or early

April. The incubation period is 28–32 days. The female

performs the task of incubating the eggs while the male bird

brings food to the newly-hatched young. The owlets leave

the nest for the first time when they are around 32–36 days

old. Without fully mature wings, the young are not yet able

to fly well and must often climb back to the nest using their

talons and beak. Juvenile

survivorship

may be only 11%.

Spotted owls hunt by sitting quietly on elevated

perches and diving down swiftly on their prey. They forage

during the night and spend most of the day roosting. Mam-

mals make up over 90% of the spotted owl’s diet. The most

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Northern spotted owl

important prey

species

is the northern flying squirrel (Glau-

comys sabrinus) which makes up about 50% of the owl’s diet.

Woodrats and hares also are important. In all, 30 species of

mammals, 23 species of birds, two reptile species, and even

some invertebrates have been found in the diets of spotted

owls.

Northern spotted owls live almost exclusively in very

old coniferous forests. They are found in virgin stands of

Douglas fir, western hemlock, grand fir, red fir, and areas

of

redwoods

that are at least 200 years old. They favor

areas that have an old-growth overstory with layers of sec-

ond-growth understory beneath. The overstory is the pre-

ferred nesting site and the owls tend to build their nests in

trees that have broken tops or cavities, or on stick platforms.

In one study, 64% of the nests were in cavities, and the

remainder were on stick platforms or other debris on tree

limbs. All of the nests in this study were in conifers, all but

two of which were living.

Little is known about what features of a stand are

critical for spotted owls. The large trees that have nest sites

may be important, particularly those producing a multi-

layered canopy in which the owls can find a benign

microcli-

mate

. A thick canopy may be critical in sheltering juvenile

owls from avian predators, whereas the understory may be

important in providing a cool place for the birds to roost

during the warm summer months.

Because of this subspecies’ dependence on old-growth

coniferous forests and because it feeds at the top

trophic

level

in the

old-growth forest food chain/web

, it is con-

sidered an “indicator species.” Indicator species are used by

ecologists to measure the health of the

ecosystem

.Ifthe

indicator species is endangered, then it is likely that scores

of other species in the ecosystem are just as endangered.

The owls are nonmigratory, with dispersal of young

being the only regularly observed movement out of estab-

lished home ranges. The home range size of spotted owls

varies from an average of 4,200 acres (1,700 ha) in Washing-

ton to about 2,000 acres (800 ha) in California. In 1987, a

team of scientists recommended that in order to be reason-

ably sure of the species’ survival that

habitat

for 1,500 pairs

be set aside. This would necessitate preserving 4–5 million

acres (1.5–2 million ha) of old-growth forests—most of what

remains.

Unfortunately for these owls, old-growth forests are

a scarce habitat which is commercially valuable for timber.

Because of the demand for old-growth timber these birds

have been the center of controversy between timber interests

and environmentalists. The declining numbers of owls alarm

preservationists who want old-growth forests set aside to

protect the owls, while the loggers feel it is in the public’s

best interest to continue to cut the economically valuable

old-growth timber. Timber companies claim that 12,000

992

Northern spotted owl. (Photograph by John and

Karen Hollingsworth. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.)

jobs will be lost along with about $300 million annually if

felling is restricted.

It has been argued that since old-growth forests are

being destroyed, these jobs and revenue will be lost eventually

anyway. It has also been argued that the U. S.

Forest Service

,

which manages most of the remaining old-growth forests,

subsidizes the timber industry by building expensive access

roads and selling the timber at artificially low prices. Envi-

ronmentalists suggest that the social costs associated with

not cutting old growth could be mitigated by redirecting

these monies to retraining programs and income supple-

ments.

In 1990, the northern spotted owl was designated by

the U. S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

as a “threatened species.”

This requires that the owl’s habitat be protected from

log-

ging

. Although the decision to list the spotted owl as “threat-

ened” did not affect existing logging contracts, timber com-

panies are trying to avoid compliance with the decision.

Specifically, they are trying to persuade the President and

Congress to revise the

Endangered Species Act

to allow

consideration of economic impacts or to make a specific

exception for some or all of the spotted owl’s habitat. Cur-

rently, under certain circumstances, economic factors can

take precedence over biological criteria in deciding whether

it is necessary to comply with habitat protection measures.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Not In My Backyard

In these cases a special seven-person interdisciplinary com-

mittee can assess the economic impacts of protecting the

habitat and circumvent the

Endangered Species

Act if they

believe it is warranted. President Bush’s Secretary of Interior

Manuel Lujan convened the committee to consider allowing

logging in spotted owl habitat on some

Bureau of Land

Management

lands.

A team of scientists appointed by the federal govern-

ment to study the situation recommended that the annual

harvest on old-growth forests be reduced by 47%. However,

former President George Bush rejected this recommendation

and instead proposed that harvest be reduced by 21%. This

angered both the environmentalists and the timber industry

and the two sides became deadlocked. In the meantime,

spotted owl policy is being determined by federal judges

rather than biologists. For example, it was a court order that

forced the U. S. Fish and

Wildlife

Service to identify 11.6

million acres (4.7 million ha) as

critical habitat

. In 1991,

a federal judge issued an injunction stopping all new timber

sales in areas where the spotted owls live on

national forest

land. The judge also mandated that the Forest Service pro-

duce a

conservation

plan and

Environmental Impact

Statement

by March 1992. This controversy continued into

the presidency of Bill Clinton who convened a Forest Sum-

mit in Portland, Oregon on April 2, 1993, to gather informa-

tion from loggers and environmentalists. Following the sum-

mit President Clinton asked his cabinet to devise a balanced

solution to the old-growth forest dilemma within 60 days.

Ultimately the fate of the northern spotted owl will

be decided in the court rooms and halls of government,

where environmentalists and timber interests continue to

battle. It is important to realize that the dispute is not merely

over one species of owl. The spotted owl is just one of many

species dependent on old-growth forests, and may not be

in the greatest danger of

extinction

. As an indicator of the

prosperity of old-growth ecosystems in the Pacific North-

west, though, its survival means continued health for the

entire

biological community

.

[Ted T. Cable]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hunter Jr., M. L. Wildlife, Forests, and Forestry. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall, 1990.

“Northern Spotted Owl.” Beacham’s Guide to the Endangered Species of North

America. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Casey, C. “The Bird of Contention.” American Forests 97 (1991): 28–68.

O

THER

“Northern Spotted Owl.” The Sierra Club. [cited May 2002]. <http://

www.sierraclub.org/lewisandclark/species/owl.asp>.

993

Not In My Backyard

NIMBY is an acronym for “Not In My Backyard” and is

often heard in discussions of

waste management

. While

every community needs a site for waste disposal, frequently

no one wants it near his or her home. In the early part of

this century, in fact, up until the early 1970s, the town

dump was a smelly, rodent-infested place that caught fire

on occasion. Loose debris from these facilities would also

blow onto adjacent property. Citizens were justified in their

aversion to landfills because

hazardous waste

and

chemi-

cals

were often dumped into landfills, which contaminated

groundwater

and surface water. After the passage of the

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

(RCRA) in

1976, many of these facilities were closed and dumps con-

verted into sanitary landfills that required daily cover, fenc-

ing, leachate collection systems, and other design elements

that made them much better neighbors. Still, many citizens

refused to have landfills close to their homes.

In addition to landfills, citizens are also concerned

about having other waste management facilities near them.

Large open air

composting

facilities are not popular because

of the odor they produce. A materials

recycling

facility

(MRF) is not always a desirable neighbor because of the

noise it generate.

Despite assurances by experts of the improvements and

safety of modern waste management facilities, communities

continue to be wary of them. In order to overcome the

NIMBY attitude, professionals in the waste management

field must collaborate with communities so that citizens gain

understanding and ownership of

solid waste

management

problems. The problem of waste is generated at the commu-

nity level so the solution must be generated at the community

level. With sensible planning and patience there may be less

NIMBY-mentality in the future.

[Cynthia Fridgen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brion, D. J. Essential Industry and the NIMBY Phenomenon: A Problem of

Distributive Justice. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1991.

Piller, C. The Fail-Safe Society: Community Defiance and the End of American

Technological Optimism. New York: Basic Books, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

Guerra, S. “NIMBY, NIMTOF, and Solid Waste Facility Siting.” Public

Management 73 (October 1991): 11–15.

Shields, P. “Overcoming the NIMBY Syndrome.” American City and County

105 (May 1990): 54.

NRC

see

Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nuclear fission

Nuclear accidents

see

Chelyabinsk, Russia; Chernobyl

Nuclear Power Station; Radioactive pollution;

Three Mile Island Nuclear Reactor; Windscale

(Sellafield) plutonium reactor

Nuclear fission

When a

neutron

strikes the nucleus of certain isotopes, the

nucleus breaks apart into two roughly equal parts in a process

known as nuclear fission. The two parts into which the

nucleus splits are called fission products. In addition to fis-

sion products, one or more neutrons is also produced. The

fission process also results in the release of large amounts

of energy.

The release of neutrons during fission makes possible

a

chain reaction

. That is, the particle needed to initiate a

fission reaction—the neutron—is also produced as a result

of the reaction. Each neutron produced in a fission reaction

has the potential for initiating one other fission reaction.

Since the average number of neutrons released in any one

fission reaction is about 2.3, the rate of fission in a block of

material increases rapidly.

A chain reaction will occur in a block of fissionable

material as long as neutrons (1) do not escape from the block

and (2) are not captured by nonfissionable materials in the

block. Two steps in making fission commercially possible,

then, are (1) obtaining a block of fissionable material large

enough to sustain a chain reaction—the critical size—and

(2) increasing the ratio of fissionable to nonfissionable mate-

rial in the block—enriching the material.

Atomic bombs, developed in the 1940s, obtain all of

their energy from fission reactions while

hydrogen

bombs

use fission reactions to trigger

nuclear fusion

. A long-

term environmental problem accompanying the use of these

weapons is their release of radioactive fission products during

detonation.

The energy available from fission reactions is far

greater, pound for pound, than can be obtained from the

combustion

of

fossil fuels

. This fact has made fission reac-

tions highly desirable as a source of energy in weapons and

in power production.

Many experts in the post-World War II years argued

for a massive investment in nuclear

power plants

. Such

plants were touted as safe, reliable, nonpolluting sources of

energy. When operating properly, they release none of the

pollutants that accompany power generation in fossil fuel

plants. By the 1970s, more than a hundred

nuclear power

plants were in operation in the United States.

Then, questions began to arise about the safety of

nuclear power plants. These concerns reached a peak when

994

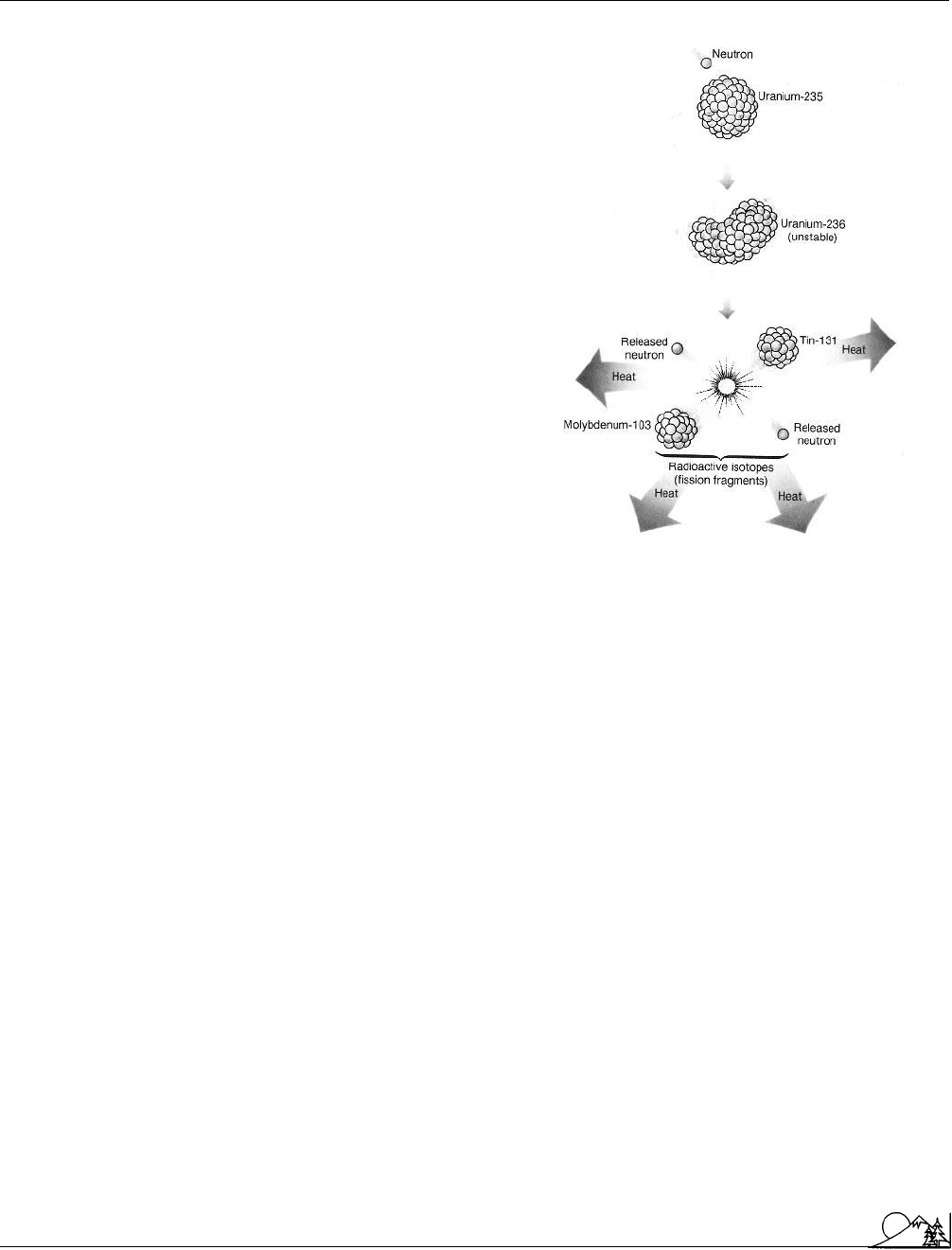

The process of nuclear fission as carried out in

the core of a nuclear reactor. A neutron strikes

the unstable isotope Uranium-235. This isotope

absorbs the neutron and splits or fissions into

tin-131 and molybdenum-103. Two or three

neutrons are released per fission event and

continue the chain reaction. The reaction prod-

uct has a total mass slightly less than the start-

ing material with the residual mass converted

into energy (primarily heat). (McGraw-Hill Inc. Re-

produced by permission.)

the cooling water system failed at the

Three Mile Island

Nuclear Reactor

at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in March

1979. That accident resulted in at least a temporary halt in

nuclear power plant construction in the United States. No

new plants have been authorized since that time. A much

more serious accident occurred at Chernobyl, Ukraine, in

1986 when one of four reactors on the site exploded, spread-

ing a cloud of radioactive material over parts of the USSR,

Poland, and northern Europe.

Perhaps the most serious environmental concern about

fission reactions relates to fission products. The longer a

fission reaction continues, the more fission products accumu-

late. These fission products are all radioactive, some with

short half lives, other with longer half lives. The former can

be stored in isolation for a few years until their

radioactivity

has reduced to a safe level. The latter, however, may remain

hazardous for hundreds or thousands of years. As of the

early 1990s, no completely satisfactory method for storing

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nuclear fusion

these nuclear wastes had been developed. See also Nuclear

fusion; Nuclear weapons; Radiation exposure; Radioactive

pollution; Radioactive waste; Radioactive waste manage-

ment; Radioactivity

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Fowler, J. M. Energy-Environment Source Book. Washington, DC: National

Science Teachers Association, 1975.

Inglis, D. R. Nuclear Energy: Its Physics and Social Challenge. Reading, MA;

Addison-Wesley, 1973.

Joesten, M. D., et al. World of Chemistry. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1991.

Nuclear fusion

The process by which stars produce energy has always been

of great interest to scientists. Not only would the answer to

that puzzle be of value to astronomers, but it might also

suggest a method by which energy could be generated for

human use on earth.

In 1938, German-American physicist Hans Bethe

suggested a method by which

solar energy

might be pro-

duced. According to Bethe’s hypothesis, four

hydrogen

atoms come together and fuse—join together—to produce

a helium atom. In the process, very large amounts of energy

are released.

This process is not a simple one, but one that requires

a series of changes. In the first step, two hydrogen atoms

fuse to form an atom of deuterium, or “heavy” hydrogen. In

later steps, hydrogen atoms are regenerated, providing the

materials needed to start the process over again. Like

nuclear

fission

, then, nuclear fusion is a

chain reaction

.

Since Bethe’s original research, scientists have discov-

ered other fusion reactions. One of these was used in the first

practical demonstration of fusion on earth, the “hydrogen”

bomb. It involved the fusion of two hydrogen isotopes, deu-

terium and tritium.

Nuclear fusion reactions pose a difficult problem. Fus-

ing isotopes of hydrogen requires that two particles with

like electrical charges be forced together. Overcoming the

electrical repulsion of these two particles requires the initial

input into a fusion reaction of very large amounts of energy.

In practice, this means heating the materials to be fused to

very high temperatures, a few tens of millions of degrees

Celsius. Because of these very high temperatures, fusion

reactions are also known as thermonuclear reactions.

Temperatures of a few millions of degrees Celsius are

common in the center of stars, so nuclear fusion can easily

be imagined there. On earth, the easiest way to obtain such

995

Tokamak nuclear fusion reactor in Oak Ridge,

Tennessee. (Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

temperatures is to explode a fission (atomic) bomb. That

explosion momentarily produces temperatures of a few tens

of millions of degrees Celsius. A fusion weapon such as a

hydrogen bomb consists, therefore, of nothing other than a

fission bomb surrounded by a mass of hydrogen isotopes.

As with nuclear fission, there is a strong motivation

to find ways of controlling nuclear fusion reactions so that

they can be used for the production of power. This research,

however, has been hampered by some extremely difficult

technical challenges. Obviously, no ordinary construction

material can withstand the temperatures of the hot, gaseous-

like material, or

plasma

, involved in a fusion reaction. Ef-

forts have been aimed, therefore, at finding ways of con-

taining the reaction with a magnetic field. The tokamak

reactor, originally developed by Russian scientists, appears

to be one of the most promising methods of solving this

problem.

Research on controlled fusion has been a slow, but

continuous, progress. Some researchers are confident that a

solution is close at hand. Others doubt the possibility of

bringing nuclear fusion under human control. All agree,

however, that successful completion of this research could

provide humans with perhaps the “final solution” to their

energy needs.

[David E. Newton]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Nuclear power

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hippenheimer, T. A. The Man-Made Sun: The Quest for Fusion Power.

Boston: Little Brown, 1984.

Inglis, D. R. Nuclear Energy: Its Physics and Social Challenge. Reading, MA;

Addison-Wesley, 1973.

P

ERIODICALS

Lidsky, L. M. “The Trouble With Fusion.” Technology Review (1984): 52–6.

Rafelski, J., and S. E. Jones. “Cold Nuclear Fusion.” Scientific American

257 (1987): 84–9.

Nuclear power

When nuclear reactions were first discovered in the 1930s,

many scientists doubted they would ever have any practical

application. But the successful initiation of the first con-

trolled reaction at the University of Chicago in 1942 quickly

changed their views.

In the first controlled nuclear reaction, scientists dis-

covered a source of energy greater than anyone had previously

imagined possible. They discovered that the nuclei of

ura-

nium

isotopes could be split, thus releasing tremendous

energy. The reaction occurred when the nuclei of certain

isotopes of uranium were struck and split by neutrons. This

is now known as

nuclear fission

, and the fission reaction

results in the formation of three types of products: energy,

neutrons, and smaller nuclei about half the size of the original

uranium nucleus.

Neutrons are actually produced in a fission reaction,

and this fact is critical for energy production. The release

of neutrons in a fission reaction means that the particles

required to initiate fission are also a product of the reaction.

Once initiated in a block of uranium, fission occurs over

and over again, in a

chain reaction

. Calculations done dur-

ing these early discoveries showed that the amount of energy

released in each fission reaction is many times greater than

that released by the chemical reactions that occur during a

conventional chemical explosion.

The possibility to release such high energies with nu-

clear reactions was used in the development of the atomic

bomb. After the dropping of this bomb brought World War

II to an end, scientists began researching the harnessing of

nuclear energy for other applications, primarily the genera-

tion of electricity. In developing the first

nuclear weapons

,

scientists only needed to find a way to initiate nuclear fis-

sion—there was no need to control it once it had begun.

In developing the peacetime application of nuclear power

however, the primary challenge was to develop a mechanism

for keeping the reaction under control once it had begun so

that the energy released could be managed and used. This

996

is the main purpose of nuclear power plants—controlling

and converting the energy produced by nuclear reactions.

There are many types of nuclear

power plants

, but

all plants have a reactor core and every core consists of

three elements. First, the fuel rods; these are long, narrow,

cylindrical tubes that hold small pellets of some fissionable

material. At present only two such materials are in practical

use, uranium-235 and plutonium-239. The uranium used

for nuclear fission is known as enriched uranium, because

it is actually a mixture of uranium-235 with uranium-238.

Uranium-238 is not fissile and the required chain reaction

will not occur if the fraction of uranium-235 present is not

at least 3%.

The second component of a reactor core is the modera-

tor. Only slow-moving neutrons are capable of initiating

nuclear fission, but the neutrons produced as a result of

nuclear fission are fast-moving. These neutrons move too

fast to initiate other reactions, thus moderators are used to

slow them down. Two of the most common moderators are

graphite (pure

carbon

) and water.

The third component of a reactor core is the control

rods. In operating a nuclear power plant safely and efficiently,

it is of the utmost importance to have exactly the right

amount of neutrons in the reactor core. If there are too few,

the chain reaction comes to an end and energy ceases to be

produced. If there are too many, fission occurs too quickly,

too much energy is released all at once, and the rate of

reaction increases until it can no longer be controlled or

contained. Control rods decrease the number of neutrons

in the core because they are made of a material that has a

strong tendency to absorb neutrons.

Cadmium

and boron

are materials that are both commonly used. The rods are

mounted on pulleys allowing them to be raised or lowered

into the reactor core as need may be. When the rods are

fully inserted, most of the neutrons in the core are absorbed

and relatively few are available to initiate a chain reaction.

As the rods are withdrawn from the core, more and more

neutrons are available to initiate fission reactions. The reac-

tions reach a point where the number of neutrons produced

in the core is almost exactly equal to the number being used

to start fission reactions, and it is then that a controlled

chain reaction occurs.

The heat energy produced in a reactor core is used to

boil water and make steam, which is then used to operate a

turbine and generate electricity. The various types of nuclear

power plants differ primarily in the way in which heat from

the core is used to do this. The most direct approach is to

surround the core with a huge tank of water, some of which

can be boiled directly by heat from the core. One problem

with boiling-water reactors is that the steam produced can be

contaminated with radioactive materials. Special precautions

must be taken with these reactors to prevent contaminated