Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clean Air Act (1963, 1970, 1990)

development of state pollution control agencies, and federal

involvement in cross-boundary air pollution cases. An

amendment to the act in 1965 directed the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) to establish federal

emission standards

for motor vehicles. (At this time,

HEW administered air pollution laws. The

Environmental

Protection Agency

(EPA) was not created until 1970.) This

represented a significant move by the federal government

from a supportive to an active role in setting air pollution

policy. The 1967 Air Quality Act provided additional fund-

ing to the states, required them to establish Air Quality

Control Regions, and directed HEW to obtain and make

available information on the health effects of air pollutants

and to identify pollution control techniques.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 marked a dramatic change

in air pollution policy in the United States. Following enact-

ment of this law, the federal government, not the states,

would be the focal point for air pollution policy. This act

established the framework that continues to be the founda-

tion for air pollution control policy today. The impetus for

this change was the belief that the state-based approach

was not working and increased pressure from a developing

environmental consciousness across the country. Public sen-

timent was growing so significantly that environmental is-

sues demanded the attention of high-ranking officials. In

fact, the leading policy entrepreneurs on the issue were Presi-

dent Richard Nixon and Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine.

The regulatory framework of The Clean Air Act fea-

tured four key components. First, National Ambient Air

Quality Standards (NAAQSs) were established for six major

pollutants:

carbon monoxide

,

lead

(in 1977),

nitrogen

dioxide, ground-level

ozone

(a key component of

smog

),

particulate

matter, and

sulfur dioxide

. For each of these

pollutants, sometimes referred to as criteria pollutants, pri-

mary and

secondary standards

were set. The

primary

standards

were designed to protect human health; the sec-

ondary standards were based on protecting crops, forests,

and buildings if the primary standards were not capable of

doing so. The Act stipulated that these standards must apply

to the entire country and be set by the EPA, based on the

best available scientific information. The costs of attaining

these standards were not among the factors considered. The

EPA was also directed to set standards for less common

toxic air pollutants.

Second, New Source Performance Standards (NSPSs)

would be set by the EPA. These standards would determine

how much air pollution would be allowed by new plants in

various industrial sectors. The standards were to be based

on the

best available control technology

(BACT) and

best available retrofit technology (BART) available for the

control of pollutants at sources such as

power plants

, steel

factories, and chemical plants.

257

Third, mobile source

emission

standards were estab-

lished to control

automobile emissions

. These standards

were specified in the statute (rather than left to the EPA),

and schedules for meeting them were also written into the

law. It was thought that such an approach was crucial to

ensure success with the powerful auto industry. The pollut-

ants regulated were

carbon

monoxide,

hydrocarbons

, and

nitrogen oxides

, with goals of reducing the first two pollut-

ants by 90% and nitrogen oxides by 82% by 1975.

The final component of the air protection act dealt

with the implementation of the new air quality standards.

Each state would be encouraged to devise a state implemen-

tation plan (SIP), specifying how the state would meet the

national standards. These plans had to be approved by the

EPA; if a state did not have an approved SIP, the EPA

would administer the Clean Air Act in that state. However,

since the federal government was in charge of establishing

pollution standards for new mobile and stationary sources,

even the states with an SIP had limited flexibility. The main

focal point for the states was the control of existing stationary

sources, and if necessary, mobile sources. The states had to

set limits in their SIPs that allowed them to achieve the

NAAQSs by a statutorily determined deadline. One problem

with this approach was the construction of tall smokestacks,

which helped move pollution out of a particular

airshed

but did not reduce overall pollution levels. The states were

also charged with monitoring and enforcing the Clean Air

Act.

The 1977 amendments to the Clean Air Act dealt

with three main issues: nonattainment, auto emissions, and

the prevention of air quality deterioration in areas where the

air was already relatively clean. The first two issues were

resolved primarily by delaying deadlines and increasing pen-

alties. Largely in response to a court decision in favor of

environmentalists (

Sierra Club

v. Ruckelshaus, 1972), the

1977 amendments included a program for the prevention

of significant deterioration (PSD) of air that was already

clean. This program would prevent polluting the air up to

the national levels in areas where the air was cleaner than

the standards. In Class I areas, areas with near pristine air

quality, no new significant air pollution would be allowed.

Class I areas are airsheds over large national parks and

wil-

derness

areas. In Class II areas, a moderate degree of air

quality deterioration would be allowed. And finally, in Class

III areas, air deterioration up to the national secondary stan-

dards would be allowed. Most of the country that had air

cleaner than the NAAQSs was classified as Class II. Related

to the prevention of significant deterioration was a provision

to protect and enhance

visibility

in national parks and wil-

derness areas even if the air pollution was not a threat to

human health. The impetus for this section of the bill was

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clean Air Act (1963, 1970, 1990)

the growing visibility problem in parks, especially in the

Southwest.

Throughout the 1980s, efforts to further amend the

Clean Air Act were stymied. President Ronald Reagan was

opposed to any strengthening of the Act, which he argued

would hurt the economy. In Congress, the controversy over

acid rain

between members from the Midwest and the

Northeast further contributed to the stalemate. Gridlock on

the issue broke with the election of George Bush, who

supported amendments to the Act, and the rise of Senator

George Mitchell of Maine to Senate Majority Leader. Over

the next two years, the issues were hammered out between

environmentalists and industry and between different re-

gions of the country. Major players in Congress were Repre-

sentatives John Dingell of Michigan and Henry Waxman

of California and Senators Robert Byrd of West Virginia

and Mitchell.

Major amendments to the Clean Air Act were passed

in the fall of 1990. These amendments addressed four major

topics: (1)

acid

rain, (2) toxic air pollutants, (3) nonattain-

ment areas, and (4)

ozone layer depletion

. To address acid

rain, the amendments mandated a 10 million ton reduction

in annual sulfur dioxide emissions (a 40% reduction based

on the 1980 levels) and a two million ton annual reduction

in nitrogen oxides to be completed in a two-phase program

by the year 2010. Most of this reduction will come from

old utility power plants. The law also creates marketable

pollution allowances, so that a utility that reduces emissions

more than required can sell those pollution rights to another

source. Economists argue that, to increase efficiency, such an

approach should become more widespread for all pollution

control.

Due to the failure of the toxic air pollutant provisions

of the 1970 Clean Air Act, new, more stringent provisions

were adopted requiring regulations for all major sources of

189 varieties of toxic air pollution within ten years. Areas

of the country still in nonattainment for criteria pollutants

were given from three to twenty years to meet these stan-

dards. These areas were also required to impose tighter con-

trols to meet the standards. To help these areas and other

parts of the country, the Act required stiffer motor vehicle

emissions standards and cleaner

gasoline

. Finally, three

chemical families that contribute to the destruction of the

stratospheric ozone layer (

chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs),

hydrochloroflurocarbons (HCFCs), and methyl chloroform)

were to be phased out of production and use.

In 1997, the EPA issued revised national ambient air

quality standards (NAAQS), setting stricter standards for

ozone and particulate matter. The American Trucking Asso-

ciation and other state and industry groups legally challenged

the new standards on the grounds that the EPA did not

have the authority under the Act to make such changes. On

258

February 27, 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously

upheld the constitutionality of the Clean Air Act as interpre-

ted by the EPA, and all remaining legal challenges to other

aspects of the standards change were rejected by a Washing-

ton DC District Court ruling in early 2002.

The Clean Air Act has met with mixed success. The

national average pollutant levels for the criteria pollutants

have decreased. Nevertheless, many localities have not

achieved these standards and are in perpetual nonattainment.

Not surprisingly, major urban areas are those most frequently

in nonattainment. The pollutant for which standards are

most often exceeded is ozone, or smog. This is due in part

to increases in nitrogen oxides (NOx), which disperse ozone.

NOx emissions increased by approximately 20% between

1970 and 2000. As a result, some parts of the country have

had worsening ozone levels. According to the EPA, the

average ozone levels in 29 national parks increased by over

4% between 1990 and 2000.

The greatest successes of air pollution control have

come with lead, which between 1981 and 2000 was reduced

by 93% (largely due to the phasing-out of leaded gasoline),

and particulates, which were reduced by 47% in the same

period. Overall particulate emissions were down 88% since

1970. Carbon monoxide has dropped by 25% and volatile

organic compounds and sulfur dioxides have declined by

over 40% each between 1970 and 2000. However, air quality

analysis is complex, and it is important to note that some

changes may be due to shifts in the economy, changes in

weather patterns, or other such variables rather than directly

attributable to the Clean Air Act.

In February 2002, President Bush introduced the

“Clear Skies” legislation, an initiative that, if fully adopted,

would make some significant changes to the Clean Air Act.

Among them would be a weakening or elimination of new

source review regulations and BART rules, and a new “cap

and trade” plan that would allow power plants that produced

excessive toxic emissions to ’buy credits’ from other plants

who had levels under the standards. The Bush administration

hailed the initiative as a less expensive way to accelerate air

pollution clean-up and a more economy-friendly alternative

to the Kyoto Protocol for greenhouse gas reductions, while

environmental groups and other critics called it a roll-back

of the Clean Air Act progress.

[Christopher McGrory Klyza and Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Belden, Roy S. The Clean Air Act. Washington, DC: ABA Publishing, 2001.

Dewey, Scott Hamilton. Don’t Breathe the Air: Air Pollution and U.S.

Environmental Politics, 1945–1970. College Station, TX: Texas A&M Uni-

versity Press, 2000.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clean Water Act (1972, 1977, 1987)

Erbes, Russell E. A Practical Guide to Air Quality Compliance. New York:

John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

U.S. Government Printing Office and R. A. Leiter. Legislative History of

the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. Buffalo, NY: William s Hein &

Co, 1998.

P

ERIODICALS

Adams, Rebecca. “ Hill Demands Clean Air Act Rewrite Data.” CQ Weekly.

60, no.18 (May 4 2002): 1161 (2).

O

THER

Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration. Emissions of

Greenhouse Gases in the United States: 2000. Report #DOE/EIA-

0573(2000): December 2001. Full-text available online at http://www.eia.-

doe.gov/oiaf/1605/ggrpt/index.html

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). AIRNow http://www.epa.gov/

airnow/index.html.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Office of Air and Radiation.

Latest Findings on National Air Quality: 2000 Status and Trends [Accessed

June 5, 2002.] http://www.epa.gov/oar/aqtrnd00/

Clean coal technology

Coal

is rapidly becoming the world’s most popular fuel.

Today in the United States, more than half of the electricity

produced comes from coal-fired

power plants

. The demand

for coal is expected to triple by the middle of the next

century, making it more widely used than

petroleum

or

natural gas

.

The unpleasant aspect of this trend is that coal is a

relatively dirty fuel. When burned, it releases particulates

and pollutants such as

carbon monoxide

,

nitrogen

and

sulfur oxides into the

atmosphere

. If the use of coal is to

expand continually, something must be done to reduce the

hazard its use presents to the

environment

.

Over the past two decades, therefore, there has been

an increasing amount of research on clean coal technologies,

methods by which the

combustion

of coal releases fewer

pollutants to the atmosphere. As early as 1970, the United

States Congress acknowledged the need for such technolo-

gies in the

Clean Air Act

of that year. One provision of that

Act required the installation of

flue gas

desulfurization

(FGD) systems ("scrubbers") at all new coal-fired plants.

More than a dozen different technologies are now

available on at least an experimental basis for the cleaning

of coal. Some of these technologies are used on coal before

it is even burned. Chemical, physical, and biological methods

have all been developed for pre-combustion cleaning. For

example, pyrite (FeS

2

) is often found in conjunction with

coal when it is mined. When the coal is burned, pyrite is

also oxidized, releasing

sulfur dioxide

to the atmosphere.

Yet pyrite can be removed from coal by rather simple,

straightforward physical means because of differences in the

densities of the two substances.

259

Biological methods for removing sulfur from coal are

also being explored. The bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans

has the ability to change the surface properties of pyrite

particles, making it easier to separate them from the coal

itself. The bacterium may also be able to extract sulfur that

is chemically bound to

carbon

in the coal.

A number of technologies have been designed to mod-

ify existing power plants to reduce the release of pollutants

produced during the combustion of coal. In an attempt to

improve on traditional wet

scrubbers

, researchers are now

exploring the use of dry injection as one of these technolo-

gies. In this approach, dry compounds of calcium, sodium,

or some other element are sprayed directly into the furnace or

into the ducts downstream of the furnace. These compounds

react with non-metallic oxide pollutants, such as sulfur diox-

ide and nitrogen dioxide, forming solids that can be removed

from the system. A variety of technologies are being devel-

oped especially for the release of oxides of nitrogen. Since

the amount of this pollutant formed is very much dependent

on combustion temperature, methods of burning coal at

lower temperatures are also being explored.

Some entirely new technologies are also being devel-

oped for installation in power plants to be built in the future.

Fluidized bed combustion

, integrated gasification com-

bined cycle, and improved coal pulverization are three of

these. In the first of these processes, coal and limestone are

injected into a stream of upward-flowing air, improving

the degree of oxidation during combustion. In the second

process, coal is converted to a gas that can be burned in a

conventional power plant. The third process involves im-

proving on a technique that has long been used in power

plants, reducing coal to very fine particles before it is fed

into the furnace.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Cruver, P. C. “What Will Be the Fate of Clean-Coal Technologies?”

Environmental Science & Technology (September 1989): 1059-1060.

Shepard, M. “Coal Technologies for a New Age.” EPRI Journal (January-

February 1988): 4-17.

Clean Water Act (1972, 1977, 1987)

Federal involvement in protecting the nation’s waters began

with the

Water Pollution

Control Act of 1948, the first

statute to provide state and local governments with the fund-

ing to address water

pollution

. During the 1950s and 1960s,

awareness grew that more action was needed and federal

funding to state and local governments was increased. In

the

Water Quality

Act of 1965

water quality standards

,

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clean Water Act (1972, 1977, 1987)

to be developed by the newly created Federal Water

Pollu-

tion Control

Administration, became an important part of

federal water pollution control efforts.

Despite these advances, it was not until the Water

Pollution Control Amendments of 1972 that the federal

government assumed the dominant role in defining and

directing water pollution control programs. This law was

the outcome of a battle between Congress and President

Richard M. Nixon. In 1970, facing a presidential re-election

campaign, Nixon responded to public outcry over pollution

problems by resurrecting the Refuse Act of 1899, which

authorized the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers

to issue

discharge

permits. Congress felt its prerogative to set na-

tional policy had been challenged. It debated for nearly 18

months to resolve differences between the House and Senate

versions of a new law, and on October 18, 1972, Congress

overrode a presidential veto and passed the Water Pollution

Control Amendments.

Section 101 of the new law set forth its fundamental

goals and policies, which continue to this day “to restore

and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity

of the Nation’s waters.” This section also set forth the na-

tional goal of eliminating discharges of pollution into naviga-

ble waters by 1985 and an interim goal of achieving water

quality levels to protect fish, shellfish, and

wildlife

.Asna-

tional policy, the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic

amounts was now prohibited; federal financial assistance was

to be given for constructing publicly owned waste treatment

works; area-wide pollution control planning was to be insti-

tuted in states; research and development programs were to

be established for technologies to eliminate pollution; and

nonpoint source

pollution—runoff from urban and rural

areas—was to be controlled. Although the federal govern-

ment set these goals, states were given the main responsibility

for meeting them, and the goals were to be pursued through

a permitting program in the new

national pollutant dis-

charge elimination system

(NPDES).

Federal grants for constructing publicly owned treat-

ment works (POTWs) had totalled $1.25 billion in 1971,

and they were increased dramatically by the new law. The

act authorized five billion dollars in fiscal year 1973, six

billion for fiscal year 1974, and seven billion for fiscal year

1975, all of which would be automatically available for use

without requiring Congressional appropriation action each

year. But along with these funds, the act conferred the re-

sponsibility to achieve a strict standard of secondary treat-

ment by July 1, 1977. Secondary treatment of sewage consists

of a biological process that relies on naturally occurring

bacteria and other micro-organisms to break down organic

material in sewage. The

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) was mandated to publish guidelines on secondary

treatment within 60 days after passage of the law. POTWs

260

also had to meet a July 1, 1983, deadline for a stricter level

of treatment described in the legislation as “best practicable

wastewater

treatment.” In addition, pretreatment pro-

grams were to be established to control industrial discharges

that would either harm the treatment system or, having

passed through it, pollute receiving waters.

The act also gave polluting industries two new dead-

lines. By July 1, 1977, they were required to meet limits

on the pollution in their discharged

effluent

using Best

Practicable Technology (BPT), as defined by EPA. The

conventional pollutants to be controlled included

organic

waste

,

sediment

,

acid

, bacteria and viruses, nutrients, oil

and grease, and heat. Stricter state water quality standards

would also have to be met by that date. The second deadline

was July 1, 1983, when industrial dischargers had to install

Best Available Control Technology

(BAT), to advance the

goal of eliminating all pollutant discharges by 1985. These

BPT and BAT requirements were intended to be “technol-

ogy forcing,” as envisioned by the Senate, which wanted the

new water law to restore water quality and protect ecological

systems.

On top of these requirements for conventional pollut-

ants, the law mandated the EPA to publish a list of toxic

pollutants, followed six months later by proposed effluent

standards for each substance listed. The EPA could require

zero discharge

if that was deemed necessary. The zero

discharge provisions were the focus of great controversy

when Congress began oversight hearings to assess imple-

mentation of the law. Leaders in the House considered the

goal a target and not a legally binding requirement. But

Senate leaders argued that the goal was literal and that its

purpose was to ensure rivers and streams ceased being re-

garded as components of the waste treatment process. In

some cases, the EPA has relied on the Senate’s views in

developing effluent limits, but the controversy over what

zero discharge means continues to this day.

The law also established provisions authorizing the

Army Corps of Engineers to issue permits for discharging

dredge or fill material into navigable waters at specified

disposal sites. In recent years this program, a key component

of federal efforts to protect rapidly diminishing

wetlands

,

has become one of the most explosive issues in the Clean

Water Act. Farmers and developers are demanding that

the federal government cease “taking” their private property

through wetlands regulations, and recent sessions of Con-

gress have been besieged with demands for revisions to this

section of the law.

In 1977, Congress completed its first major revisions

of the Water Pollution Control Amendments (which was

renamed the “Clean Water Act"), responding to the fact

that by July 1, 1977 only 30 percent of major municipalities

were complying with secondary treatment requirements.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clean Water Act (1972, 1977, 1987)

Moreover, a National Commission on Water Quality had

issued a report which recommended that zero discharge be

redefined to stress

conservation

and

reuse

and that the

1983 BAT requirements be postponed for five to ten years.

The 1977 Clean Water Act endorsed the goals of the 1972

law, but granted states broader authority to run their con-

struction grants programs. The act also provided deadline

extensions and required EPA to expand the lists of pollutants

it was to regulate.

In 1981, Congress found it necessary to change the

construction grants program; thousands of projects had been

started, with $26.6 billion in federal funds, but only 2,223

projects worth $2.8 billion had been completed. The Con-

struction Grant Amendments of 1981 restricted the types

of projects that could use grant money and reduced the

amount of time it took for an application to go through the

grants program.

The Water Quality Act of 1987 phased out the grants

program by fiscal year 1990, while phasing in a state revolving

loan fund program through fiscal year 1994, and thereafter

ending federal assistance for wastewater treatment. The 1987

act also laid greater emphasis on toxic substances; it required,

for instance, that the EPA identify and set standards for

toxic pollutants in sewage

sludge

, and it phased in require-

ments for stormwater permits. The 1987 law also established

a new toxics program requiring states to identify “toxic hot

spots"—waters that would not meet water quality standards

even after technology controls have been established—and

mandated additional controls for those bodies of water.

These mandates greatly increased the number of

NPDES permits that the EPA and state governments issued,

stretching budgets of both to the limit. Moreover, states

have billions of dollars worth of wastewater treatment needs

that remain unfunded, contributing to continued violations

of water quality standards. The new permit requirements

for stormwater, together with sewer overflow, sludge, and

other permit requirements, as well as POTW construction

needs, led to a growing demand for more state flexibility in

implementing the clean water laws and for continued federal

support for wastewater treatment. State and local govern-

ments insist that they cannot do everything the law requires;

they argue that they must be allowed to assess and prioritize

their particular problems.

Yet despite these demands for less prescriptive federal

mandates, on May 15, 1991, a bipartisan group of senators

introduced the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Act

to expand the federal program. The proposal was eventually

set aside after intense debate in both the House and Senate

over controversial wetlands issues. Amendments to the Clean

Water Act proposed in both 1994 and 1995 also failed to

make it to a vote.

261

In 1998, President Clinton introduced a Clean Water

Action Plan, which primarily focused on improving compli-

ance, increasing funding, and accelerating completion dates

on existing programs authorized under the Clean Water

Act. The plan contained over 100 ’action items’ that involved

interagency cooperation of EPA,

U.S. Department of Agri-

culture

(USDA), Army Corps of Engineers, Department

of the Interior, Department of Energy,

Tennessee Valley

Authority

, Department of

Transportation

, and the Depart-

ment of Justice. Key goals were to control nonpoint pollu-

tion, provide financial incentives for conservation and stew-

ardship of private lands, restore wetlands, and expand the

public’s ’right to know’ on water pollution issues.

New rules were proposed in 1999 to strengthen the

requirements for states to set limits for and monitor the

Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of pollution in their

waterways. The TMDL rule has been controversial, primar-

ily because states and local authorities lack the funds and

resources to carry out this large-scale project. In addition,

agricultural and forestry interests, who previously were not

regulated under the Clean Water Act, would be affected by

TMDL rules. As of May 2002, the Bush administration has

delayed the rule for further review.

In May 2002 the EPA announced a new rule changing

the definition of “fill material” under the Clean Water Act

to allow dirt, rocks, and other displaced material from moun-

taintop

coal

mining operations to be deposited into rivers

as waste under permit from the Army Corps of Engineers,

a practice that was previously unlawful under the Clean

Water Act. Shortly thereafter, a group of congressional rep-

resentatives introduced new legislation to overturn this rule,

and a federal district court judge in West Virginia ruled that

such amendments to the Clean Water Act could only be

made by Congress, not by an EPA rule change. Whether

or not the fill material rule will remain part of the Act

remains to be seen.

As the Federal Water Pollution Control Act marks

its thirtieth anniversary, the EPA state and federal regulators

are increasingly recognizing the need for a more comprehen-

sive approach to water pollution problems than the current

system, which focuses predominantly on POTWs and indus-

trial facilities. Nonpoint source pollution, caused when rain

washes pollution from farmlands and urban areas, is the

largest remaining source of water quality impairment, yet

the problem has not received a fraction of the regulatory

attention addressed to industrial and municipal discharges.

Despite this fact, the EPA claims that the Clean Water Act

is responsible for a one billion ton decrease in annual

soil

runoff

from farming, and an associated reduction in

phos-

phorus

and

nitrogen

levels in water sources. EPA also

asserts that wetland loss, while still a problem, has slowed

significantly—from 1972 levels of 460,000 acres per year to

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clear-cutting

current losses of 70,000-90,000 annually. However, critics

question these figures, citing abandoned mitigation projects

and reclaimed wetlands that bear little resemblance to the

habitat

they are supposed to replicate. See also Agricultural

pollution; Environmental policy; Industrial waste treat-

ment; Sewage treatment; Storm runoff; Urban runoff

[David Clarke and Paula Anne Ford-Martin]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Committee on Mitigating Wetland Losses, Board on Environmental Stud-

ies and Toxicology, Water Science and Technology Board, Division on

Earth and Life Sciences, National Research Council. Compensating for

Wetland Losses Under the Clean Water Act. Washington, DC: National

Academy Press, 2001. (Full-text available online at http://books.nap.edu/

books/0309074320/html/index.html)

P

ERIODICALS

Kaiser, Jocelyn. “Wetlands Policy is All Wet.” Science Now (June 26,

2001): 3.

O

THER

Copeland, Claudia. “Water Quality: Implementing the Clean Water Act.”

CRS Issue Brief for Congress IB89102 (August 2001). Online at http://

cnie.org/NLE/CRSreports/water/h2o-15.cfm

Sierra Club. Clean Water Online [Accessed June 1, 2002]. http://www.sier-

raclub.org/cleanwater/waterquality/

O

RGANIZATIONS

America’s Clean Water Foundation, 750 First Street NE, Suite 1030,

Washington, DC USA 20002 (202) 898-0908, Fax: (202) 898-0977,

Email: , http://yearofcleanwater.org/

Clear-cutting

Webster’s Dictionary defines clear-cutting as “removal of all

the trees in a stand of timber.” This

forest management

technique has been used in a variety of forests around the

world. For many years, it was considered the most economi-

cal and environmentally sound way of harvesting timber.

Since the 1960s and 1970s, the practice has been increasingly

called into question as more has been learned about the

ecological benefits of old growth timber especially in the

Pacific Northwest of the United States and the global ecolog-

ical value of tropical rain forests.

Foresters and loggers point out that there are practical

economic and safety reasons for the practice of clear-cutting.

For example, in the Pacific Northwest, these reasons revolve

around the volume of wood that is present in the old growth

forests. This volume can actually be an obstacle at times to

harvesting, so that the most inexpensive way to remove the

trees is to cut everything.

During the post-World War II housing boom in the

1950s, clear-cutting overtook selective cutting as the pre-

ferred method for harvesting in the Pacific Northwest. Since

262

that time, worldwide demand for lumber has continued to

rise. Practical arguments that the practice should continue

despite its ecological implications are tied directly to the

volume and character of the forest itself. Wood in temperate

climates decays slowly, resulting in a large number of fallen

logs—making even walking difficult, much less dragging cut

trees to areas where they can be hauled to mills. Tall trees

with narrow branch structures produce a lot of stems in a

small area, therefore, the total

biomass

(or total input of

living matter) in these temperate forests is typically four

times that of the densest

tropical rain forest

. Some redwood

forest groves in California have been measured with 20 times

the biomass of similar sites in the tropics. Those supporting

the harvest of these trees and clear-cutting point out that if

these trees are not used, it will put increased pressure on

other timber producers throughout the world to supply this

wood. This could have high environmental costs globally,

since it could take 10–30 acres (4–12 ha) of

taiga

forest in

northern Canada, Alaska, or Siberia to produce the wood

obtainable from one acre in the state of Washington.

Clear-cutting makes harvesting these trees very lucra-

tive. The number of trees and downed logs makes it difficult

to cut only some of the trees, and falling trees can damage

the survivors; in addition, they can be damaged when

dragged across the ground to be loaded onto trucks. This is

made more expensive and time consuming by working

around the standing trees. In areas that have been selectively

logged, the trees left standing are may be knocked down by

winds or may drop branches, presenting a considerable safety

risk to loggers working in the area.

Old growth forests leave so much woody debris and

half-decayed logs on the ground that it can be difficult to

walk through a harvested patch to plant seedlings. This is

why an accepted part of the clear-cut practice in the past

has been to burn the leftover

slash

, after which seedlings

are planted. Brush that grows on the site is treated with

herbicide

to allow the seedlings time to grow to the point

at which they can compete with other vegetation.

Supporters of clear-cutting contend that it has unique

advantages: burning consumes fuel that would otherwise be

available to feed forest fires;

logging

roads built to haul the

trees out open the forests to recreational uses and provide

firebreaks; clear-cutting leaves no snags or trees to interfere

with reseeding the forest, and allows use of helicopters and

planes to spray herbicides—the brush that grows up naturally

in the sunlight and provides browse for big-game

species

such as deer and elk.

Detractors point to a number of very negative environ-

mental and economic consequences that need to be consid-

ered: particularly where clear cuts have been done near urban

areas, plumes of

smoke

produced by burning slash have

polluted cities; animal browse is choked out after a few years

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Clear-cutting

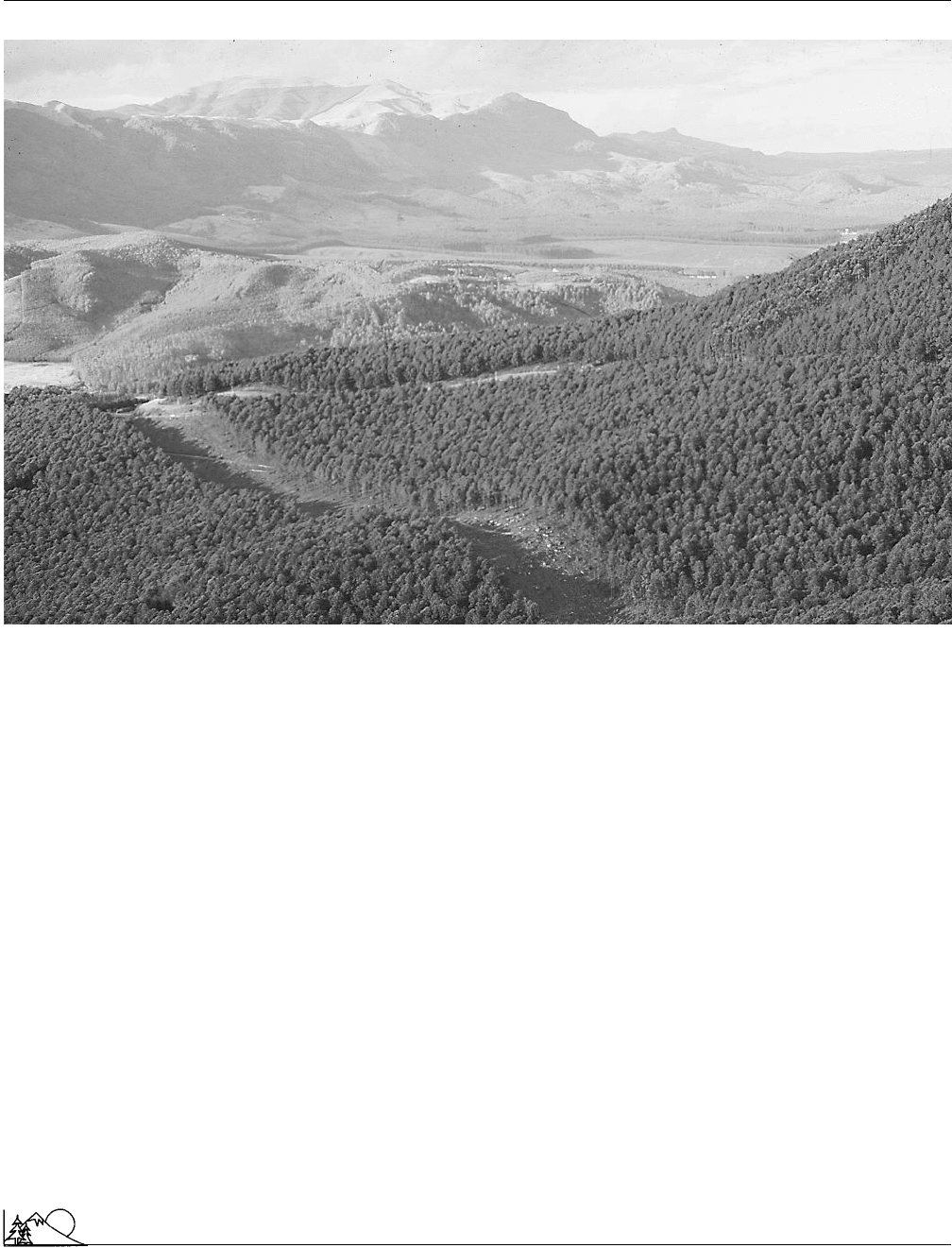

An aerial view of a clear-cut area snaking its way through a South African forest (Photograph by Marco Polo.

Phototake. Reproduced by permission.)

by the new seedlings, creating a darkened forest floor that

lacks almost any vegetation or

wildlife

for at least three

decades; herbicides applied to control vegetation contribute

to the degradation of surface

water quality

; mining the

forest causes declines in species diversity and loss of habitats

(declaration of the

northern spotted owl

as an

endan-

gered species

and the efforts to preserve its

habitat

is an

example of the potential loss of diversity); new microclimates

appear that promote less desirable species than the trees they

replace; so much live and rotting wood is harvested or burned

that the

soil

fertility is reduced, affecting the potential for

future tree growth.

Critics also point out that

erosion

and

flooding

in-

creases from clear-cut areas have significant economic impact

downstream in the watersheds. Studies have shown that

since the clear-cut practice increased following World War

II, landslides have increased to six times the previous rate.

This has resulted in increased

sediment

delivery to rivers

and streams where it has a detrimental impact on the stream

fishery.

263

Loss of

critical habitat

for endangered species such

as the spotted owl and the impact of sediment on the

salmon

fishery have resulted in government efforts to set aside old

growth forest

wilderness

to preserve the unique forest

eco-

system

. The practice of clear-cutting with its pluses and

minuses, however, continues not only in the Pacific North-

west, but in other forests in the United States and in other

areas of the world.

Clear-cutting and rain forests

Another area where clear-cutting has become the focus

of ecological debate is in the tropical rain forests. Many

of the same economic pressures that make clear-cutting a

lucrative practice in the United States make it equally attrac-

tive in the

rain forest

, but there are significant environmen-

tal consequences.

Since 1960, the world demand for wood has increased

by 90%, and as indicated above, the pressure to supply lumber

to meet this demand has also increased. Nearly one-half of

the Earth’s rain forests have been cut in the last 30 years.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Frederic E. Clements

Besides the demand for building material or fuel, these for-

ests are also subject to significant clearing to later be worked

to produce food in new agricultural areas and to facilitate

the exploration for oil and minerals. If this loss continues

at present estimated rates, the rain forests will be totally

harvested by the year 2040.

Rain forest activists continually work to remind the

world of the importance of the forests. Locally, for instance,

the presence or absence of the rain forest can change the

climate

and the local water budget. For example, times of

drought

are more severe and when the rains come, flooding

is increased. As well, rain forests can have a major impact

on the global climate. When they are cut and the slash

burned, significant amounts of

carbon dioxide

are released

into the

atmosphere

, which may contribute to the overall

greenhouse effect

and general warming of the earth.

The biological diversity of these forest ecosystems is

vast. Rain forests contain about one-half the known plant

and animal species in the world and very few of these species

have ever been studied by scientists for their potential bene-

fits. (More that 7,000 medicines have already been derived

from tropical plants. It is uncertain how many more such

uses are yet to be found.)

Most rain forests occur in less-developed countries

where it is difficult to meet the expanding needs of rapidly

increasing populations for food and shelter. They need the

economic benefits that can be derived from the rain forest

for their very survival. Any attempt at stopping the clear-

cutting practice must provide for their needs to be successful.

Until a better practice is developed, clear-cutting will remain

an environmental issue on a global scale for the next several

decades.

[James L. Anderson]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dietrich, W. The Final Forest. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

Harris, D. The Last Stand: The War between Wall Street and Main Street.

Times Books, Random House, 1995.

Frederic E. Clements (1874 – 1945)

American ecologist

For Frederick Clements, trained in botany as a plant physiol-

ogist, ecology became “the dominant theme in the study of

plants, indeed...the central and vital part of botany.” He

became a leader in the new science, still described as “the

leading plant ecologist of the day.”

Clements was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, and earned

all of his degrees in botany from the University of Nebraska,

264

attaining his Ph.D. under Charles Bessey in 1989. As a

student, he participated in Bessey’s famous “Botanical Semi-

nar” and helped carry out an ambitious survey of the vegeta-

tion of Nebraska, publishing the results—co-authored with

a class-mate—in an internationally recognized volume titled

The Phytogeography of Nebraska, out in print the same

year (1898) that he received his doctorate. He then accepted

a faculty position at the university in Lincoln.

Clements married Edith Schwartz in 1899, described

(in Ecology in 1945) as a wife and help-mate, who “unspar-

ingly devoted her unusual ability as an illustrator, linguist,

and botanist” to become his life-long field assistant and also

a collaborator on research and books on flowers, particularly

those of the Rocky Mountains. Clements rose through the

ranks as a teacher and researcher at Nebraska and then,

in 1907, he was appointed as Professor and Head of the

department of botany at the University of Minnesota. He

stayed there until 1917, when he moved to the Carnegie

Institution in Washington, D.C., where he focused full-

time on research for the rest of his career. Retired from

Carnegie in 1941, he continued a year-round work-load in

research, spending summers on Pikes Peak at an alpine

laboratory and winters in Santa Barbara at a coastal labora-

tory. He died in Santa Barbara on July 26, 1945.

Publication of Research Methods in Ecology in 1905

marked his promotion to full professor at the University of

Nebraska, but more importantly it marked his turn from taxo-

nomic and phytogeographical work to ecology. It has been

called “the earliest how-to book in ecology,” and “a manifesto

for theemerging field.” More broadly, Arthur Tansley, a lead-

ing plant ecologist of the time in Great Britain, though critical

of some of Clements’ views, described him as “by far the great-

est individual creator of the modern science of vegetation.”

Henry a. Gleason, though an early and severe critic of Clem-

ents’ ideas, also recognized him as “an original ecologist, one

inspired by Europeans but developing his ideas entirely de

novo from his own fertile brain.”

Clements deplored the “chaotic and unsystematized”

state of ecology and assumed the task of remedying it. He

did bring rigor, standardization, and an early quantitative

approach to research processes in plant ecology, especially

through his development of sampling procedures at the turn

of the century. Robert McIntosh, writing on the background

of ecology, argues that Clements was the “pioneer in devel-

oping the quadrat as the basis of quantitative community

ecology,” was “an earnest cheerleader for quantitative plant

ecology, and was the notable American developer and advo-

cate of the quadrat method,” though he also declares that

“Clements did not get beyond simple counting, and more

sophisticated statistical considerations were left to others.”

However, McIntosh still credits Clements’ work as a giant

step to quantification in ecology, the crux being that Clem-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Frederic E. Clements

ents methods “were designed to examine and follow change

in vegetation, not only to report the status quo.”

Clements is often described as rigid and dogmatic,

which seems at odds with his importance in emphasizing

change in natural systems; that emphasis on what he called

“dynamic ecology” became his research trademark. Clements

also stressed the importance of process and function. Clem-

ents anticipated ecosystem ecology through his concern for

changes through time of plant associations, in correspon-

dence to changes in the physical sites where the communities

were found. His rudimentary conception of such systems

carried his ecological questions beyond the traditional con-

fines of plant ecology to what McIntosh described as “the

larger system transcending plants, or even living organisms”

to link to the abiotic environment, especially climate. McIn-

tosh also credits him with a definition of paleoecology that

antedated major developments that would studies of vegeta-

tion and pollen analysis (or palynology). Clements being

Clements, he went into print with a book, Methods and

Principles of Paleo-Ecology (1924) appropriate to the new

topic. Clements even played a role, if not a major one

relative to figures like Forbes, toward understanding what

ecologists came to call eutrophic changes in lakes, an area

of major current consideration in the environmental science

of water bodies.

One of the stimulants for botanical, and then plant

ecological, research for Clements and other students of Bes-

sey’s at Nebraska was their location in a major agricultural

area dependent on plants for crops. Problems of agriculture

remained one of Clements’ interests for all of his life. During

his long career, Clements remained continually involved in

various ways of applying ecology to problems of land use

such as grazing and soil erosion, even the planning of shelter

belts. In large part because of the early work by Bessey

and Clements and their colleagues and collaborators, the

Midwest became a center for the development of grassland

ecology and range management. Worster (in Nature’s Econ-

omy, 1994) suggests that Clements’ “dynamic ecology pro-

vided much of the scientific authority for the new ecological

conservation movement” which, from the 1930’s on, relied

heavily on his “climax theory as a yardstick by which man’s

intrusions into nature could be measured.” Though consid-

ered misguided by some, pleas for wilderness set-asides still

argue today that land-use policy should leave “the climax”

undisturbed or preserved areas returned to a perceived climax

condition. Clements believed early that homesteaders in

Nebraska were wrong to destroy the sod covering the san-

dhills of Nebraska and that the prairies should be grazed

and not tilled. Farmers objected early to the implications of

climax theory because they feared threats to their livelihoods

from calls for cautious use of marginal lands. Even some

scientific attempts to discredit the idea of the climax were

265

based on the desire to undermine its importance to the

conservation movement.

Clements even anticipated a century of sporadic con-

nections between biological ecology and human ecology in

the social sciences, arguing that sociology “is the ecology of

a particular species of animal and has, in consequence, a

similar close association with plant ecology.” That connec-

tion was lost in in professional ecology in the early forties

and has still not been reestablished, even at the beginning

of the twenty-first century. Though Clements’ name is still

recognized today as one of ecology’s foundation thinkers,

and though he gained considerable respect and influence

among the ecologists of his day, his work from the beginning

was controversial. One reason was that ecologists were

skeptical that approaches from plant physiology could be

transposed directly to ecology. Another reason, and the idea

with which Clements is still associated three-quarters of a

century later, was his conviction that the successional process

was the same as the development of an organism and that

the communities emerging as the end-points of succession

were in fact super-organisms. Clements believed that succes-

sion was a dynamic process of ’progressive’ development of

the plant formation, that it was controlled absolutely by

climate, developed in an absolutely predictable way (and in

the same way in all similar climates) and then was absolutely

stable for long periods of time. A cautionary note from

MacIntosh: “Clements’s ideas are notably resilient and per-

sist, often under different names,” even “some of his suspect

ideas persist in the new ecology under new rubrics.” Synony-

mizing Gaia with a super organism is one frequently cited

example.

Clements’ fondness for words, and especially for coin-

ing his own nonce terms for about every conceivable nuance

of his work also got him in trouble with his colleagues in

ecology. As McIntosh terms it, Clements was known for

his “labyrinthine logic and proliferation of terminology,”

characterized by others as “chronic logorrhea.” This fond-

ness for coining new words to describe his work, e.g., ’the-

rium’ to describe a successional stage caused by animals,

added to the fuel for critics who wished to find fault with

the substance of his ideas. Unfortunately, Clements also gave

further cause to those, then and now, wishing to discount all

of his ideas by retaining a belief in Lamarckian evolution,

and by doing experiments during retirement at his alpine

research station, in which he even claimed he been able to

convert “several Linnean species into each other, histologi-

cally as well as morphologically.”

Kingsland, writing in 1991, in Foundations of Ecol-

ogy, identified Clements’ 1936 article “The Nature and

Structure of the Climax” as a classic paper and included its

author as among those who defined ecology, but she could

still claim that “by the 1950s plant ecologists had abandoned

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Climate

many of the central principles of Clementsian dogma, as

well as the more cumbersome features of his classification

system, as inappropriate or unproductive.” But without the

work and thinking of the early ecologists that created a

foundation on which to build, ecology might be considerably

the lesser today. Missteps certainly were made, but the

stones were laid and some of that foundation is based on

the dynamics of ecological processes as first conceived by

Clements in a considerable body of pioneering work.

[Gerald L. Young Ph.D.]

F

URTHER

R

EADING

B

OOKS

Clements, Edith S. Adventures in Ecology: Half a Million Miles...From

Mud to Macadam. NY: Pageant Press, 1960.

Humphrey, Harry B. “Frederick Edward Clements 1874–1945.” In Makers

of North American Botany. NY: The Ronald Press Company, 1961.

P

ERIODICALS

Phillips, John. “A Tribute to Frederic E. Clements and His Concepts in

Ecology.” Ecology 35, no. 2 (April 1954): 1114–115.

Pound, Roscoe. “Frederic E. Clements as I Knew Him.” Ecology 35, no.

2 (April 1954): 112–113.

Climate

Climate is the general, cumulative pattern of regional or

global weather patterns. The most apparent aspects of cli-

mate are trends in air temperature and humidity, wind,

and precipitation. These observable phenomena occur as the

atmosphere

surrounding the earth continually redistrib-

utes, via wind and evaporating and condensing water vapor,

the energy that the earth receives from the sun.

Although the climate remains fairly stable on the hu-

man time scale of decades or centuries, it fluctuates continu-

ously over thousands or millions of years. A great number

of variables simultaneously act and react to create

stability

or fluctuation in this very complex system. Some of these

variables are atmospheric composition, rates of

solar energy

input,

albedo

(the earth’s reflectivity), and terrestrial geog-

raphy. Extensive research helps explain and predict the be-

havior of individual climate variables, but the way these

variables control and respond to each other remains poorly

understood. Climate behavior is often likened to “chaos,”

changes and movements so complex that patterns cannot be

perceived in them, even though patterns may exist. Never-

theless, studies indicate that human activity may be dis-

turbing larger climate trends, notably by causing global

warming. This prospect raises serious concern because rapid

anthropogenic

climate change could severely stress ecosys-

tems and

species

around the world.

266

Solar energy and climate

Solar energy is the driving force in the earth’s climate.

Incoming radiation from the sun warms the atmosphere

and raises air temperatures, warms the earth’s surface, and

evaporates water, which then becomes humidity, rain, and

snow. The earth’s surface reflects or re-emits energy back

into the atmosphere, further warming the air. Warming

air expands and rises, creating convection patterns in the

atmosphere that reach over several degrees of latitude. In

these convection cells, low pressure zones develop under

rising air, and high pressure zones develop where that air

returns downward toward the earth’s surface. Such differ-

ences in atmospheric pressure force air masses to move, from

high to low pressure regions. Movement of air masses creates

wind on the earth’s surface. When these air masses carry

evaporated water, they may create precipitation when they

move to cooler regions.

The sun’s energy comes to the earth in a spectrum of

long and short radiation wavelengths. The shortest wave-

lengths are microwaves and infrared waves. Infrared radia-

tion is felt as heat. A small range of medium wavelength

radiation makes up the spectrum of visible light. Longer

wavelengths include ultraviolet (UV) radiation and radio

waves. These longer wavelengths cannot be sensed, but UV

radiation can cause damage as organic tissues (such as skin)

absorb them. The difference in wavelengths is important

because long and short wavelengths react differently when

they encounter the earth and its atmosphere.

Solar energy approaching the earth encounters

filters

,

reflectors, and absorbers in the form of atmospheric gases,

clouds, and the earth’s surface. Atmospheric gases filter in-

coming energy, selectively blocking some wavelengths and

allowing other wavelengths to pass through. Blocked wave-

lengths are either absorbed and heat the air or scattered and

reflected back into space. Clouds, composed of atmospheric

water vapor, likewise reflect or absorb energy but allow some

wavelengths to pass through. Some energy reaching the

earth’s surface is reflected; a great deal is absorbed in heating

the ground, evaporating water, and conducting

photosyn-

thesis

. Most energy that the earth absorbs is re-emitted in

the form of short, infrared wavelengths, which are sensed

as heat. Some of this heat energy circulates in the atmosphere

for a time, but eventually it all escapes. If this heat did not

escape, the earth would overheat and become uninhabitable.

Variables in the climate system

Climate responds to conditions of the earth’s energy

filters, reflectors, and absorbers. As long as the atmosphere’s

filtering effect remains constant, the earth’s reflective and

absorptive capacities do not change, and the amount of

incoming energy does not vary, climate conditions should

stay constant. Most of the time, though, some or all of these

elements fluctuate. The earth’s reflectivity changes as the