Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Furans

For a period of time, compounds of

mercury

and

cadmium

were very popular as fungicides. Until quite re-

cently, for example, the compound methylmercury was

widely used by farmers in the United States who used it to

protect growing plants and to treat stored grains.

During the 1970s, however, evidence began to accu-

mulate about a number of adverse effects of mercury- and

cadmium-based fungicides. The most serious effects were

observed among birds and small animals who were exposed

to sprays and dusting or who ate treated grain. A few dra-

matic incidents of methylmercury

poisoning

among hu-

mans, however, were also recorded. The best known of these

was the 1953 disaster at Minamata Bay, Japan.

At first, scientists were mystified by an epidemic that

spread through the Minamata Bay area between 1953 and

1961. Some unknown factor caused serious nervous disorders

among residents of the region. Some sufferers lost the ability

to walk, others developed mental disorders, and still others

were permanently disabled. Eventually researchers traced the

cause of these problems to methylmercury in fish eaten by

residents of the area. For the first time, the terrible effects

of the compound had been confirmed.

As a result of the problems with mercury and cadmium

compounds, scientists have tried to develop less toxic substi-

tutes for the more dangerous fungicides. Dinocap, binapa-

cryl, and benomyl are three examples of such compounds.

Another approach has been to use

integrated pest

management

and to develop plants that are resistant to

fungi. The latter approach was used with great success during

the corn blight disaster of 1970. Researchers worked quickly

to develop strains of corn that were resistant to the corn-

leaf blight fungus and by 1971 had provided farmers with

seeds of the new strain. See also Minamata disease

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Chemistry and the Food System. A Study by the Committee on Chemistry

and Public Affairs. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 1980.

Fletcher, W. W. The Pest War. New York: Wiley, 1974.

Selinger, B. Chemistry in the Marketplace. 4th ed. Sydney: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, 1989.

Furans

Furans are by-products of natural and industrial processes

and are considered environmental pollutants. They are

chemical substances found in small amounts in the

environ-

ment

, including air, water and

soil

. They are also present

in some foods. Although the amounts are small, they are

persistent and remain in the environment for long periods

607

of time, also accumulating in the food chain. The U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Persistent Bi-

oaccumulative and Toxic (PBT) Chemical Program classifies

furans as priority PBTs.

Furans belong to a class of organic compounds known

as heterocyclic aromatic

hydrocarbons

. The basic furan

structure is a five-membered ring consisting of four atoms

of

carbon

and one oxygen. Various types of furans have

additional atoms and rings attached to the basic furan struc-

ture. Some furans are used as solvents or as raw materials

for synthesizing

chemicals

.

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) are of partic-

ular concern as environmental pollutants. These are three-

ringed structures, with two rings of six carbon atoms each

(

benzene

rings) attached to the furan. Between one and

eight

chlorine

atoms are attached to the rings. There are

135 types of PCDFs, whose properties are determined by

the number and position of the chlorine atoms. PCDFs

are closely related to polychlorinated dioxins (PCDDs) and

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs). These three types of

toxic compounds often occur together and PCDFs are major

contaminants of manufactured PCBs. In fact, the term

di-

oxin

commonly refers to a subset of these compounds that

have similar chemical structures and toxic mechanisms. This

subset includes 10 of the PCDFs, as well as seven of the

PCDDs and 12 of the PCBs. Less frequently, the term

dioxin is used to refer to all 210 structurally-related PCDFs

and PCDDs, regardless of their toxicities.

Furans are present as impurities in various industrial

chemicals. PCDFs are trace byproducts of most types of

combustion

, including the

incineration

of chemical, indus-

trial, medical, and municipal waste, the burning of wood,

coal

, and peat, and

automobile emissions

. Thus most

PCDFs are released into the environment through smoke-

stacks. However the backyard burning of common household

trash in barrels has been identified as potentially one of the

largest sources of dioxin and furan emissions in the United

States. Because of the lower temperatures and inefficient

combustion in burn barrels, they release more PCDFs than

municipal incinerators. Some industrial chemical processes,

including chlorine bleaching in

pulp and paper mills

, also

produce PCDFs.

PCDFs that are released into the air can be carried

by currents to all parts of the globe. Eventually they fall to

earth and are deposited in soil, sediments, and surface water.

Although furans are slow to volatilize and have a low solubil-

ity in water, they can wash from soils into bodies of water,

evaporate, and be re-deposited elsewhere. Furans have been

detected in soils, surface waters, sediments, plants, and ani-

mals throughout the world, even in arctic organisms. They

are very resistant to both chemical breakdown and biological

degradation by

microorganisms

.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Future generations

Most people have low but detectable levels of PCDDs

and PCDFs in their tissues. Furans enter the food chain

from soil, water, and plants. They accumulate at the higher

levels of the food chain, particularly in fish and animal fat.

The concentrations of PCDDs and PCDFs may be hundreds

or thousands of times higher in aquatic organisms than in

the surrounding waters. Most humans are exposed to furans

through animal fat, milk, eggs, and fish. Some of the highest

levels of furans are found in human breast milk. The presence

of dioxins and furans in breast milk can lead to the develop-

ment of soft, discolored molars in young children. Industrial

workers can be exposed to furans while handling chemicals

or during industrial accidents.

Furans bind to aromatic hydrocarbon receptors in cells

throughout the body, causing a wide range of deleterious

effects, including developmental defects in fetuses, infants,

and children. Furans also may adversely affect the reproduc-

tive and immune systems. At high exposure levels, furans

can cause chloracne, a serious acne-like skin condition. Furan

itself, as well as PCDFs, are potential cancer-causing agents.

The switch from leaded to unleaded

gasoline

, the

halting of PCB production in 1977, changes in paper manu-

facturing processes, and new air and

water pollution

con-

trols, have reduced the emissions of furans. In 1999 the

United States, Canada, and Mexico agreed to cooperate to

further reduce the release of dioxins and furans.

On May 23, 2001, EPA Administrator Christie Whit-

man, along with representatives from more than 90 other

countries, signed the global treaty on

Persistent Organic

Pollutants

. The treaty phases out the manufacture and use of

12 toxic chemicals, the so-called “dirty dozen,” that includes

furans. The United States opposed a complete ban on furans

and dioxins; thus, unlike eight of the other chemicals that

were banned outright, the treaty calls for the use of dioxins

and furans to be minimized and eliminated where feasible.

[Margaret Alic Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lippmann, Morton, ed. Environmental Toxicants: Human Exposures and

their Health Effects. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 2000.

Paddock, Tod. Dioxins and Furans: Questions and Answers. Philadelphia:

Academy of Natural Sciences, 1989.

Wittich, Rolf-Michael, ed. Biodegradation of Dioxins and Furans. Austin:

R. G. Landes Co., 1998.

O

THER

“Dioxins, PCBs, Furans, and Mercury.” Fox River Watch. [cited May 15,

2002]. <http://www.foxriverwatch.com/dioxins_pcb_pcbs_1.html?source=

overture>.

“Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins and Related Compounds Update: Im-

pact on Fish Advisories.” EPA Fact Sheet. United States Environmental

Protection Agency. September 1999. [cited May 8, 2002]. <http://www.ep-

a.gov/ost/fish/dioxin.pdf>.

608

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Priority PBTs: Dioxins and Fu-

rans.” Persistent Bioaccumulative and Toxic (PBT) Chemical Program. March

9, 2001 [cited May 13,2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/pbt/dioxins.htm>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Clean Water Action Council, 1270 Main Street, Suite 120, Green Bay,

WI USA 54302 (920) 437-7304, Fax: (920) 437-7326, Email:

CleanWater@cwac.net, <http://www.cwac.net/index.html>

United Nations Environment Programme: Chemicals, 11-13, chemin des

Ane

´

mones, 1219 Cha

ˆ

telaine, Geneva, Switzerland, Email: opereira@

unep.ch, <http://www.chem.unep.ch>

United States Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania

Avenue, NW, Washington , DC USA 20460 Toll Free: (800) 490-9198,

Email: public-access@epa.gov, <http://www.epa.gov>

Fusion

see

Nuclear fusion

Future generations

According to demographers, a generation is an age-cohort

of people born, living, and dying within a few years of each

other. Human generations are roughly defined categories,

and the demarcations are not as distinct as they are in many

other

species

. As the Scottish philosopher David Hume

noted in the eighteenth century, generations of human be-

ings are not like generations of butterflies, who come into

existence, lay their eggs, and die at about the same time, with

the next generation hatching thereafter. But distinctions can

still be made, and future generations are all age-cohorts of

human beings who have not yet been born.

The concept of future generations is central to

envi-

ronmental ethics

and

environmental policy

, because the

health and well-being—indeed the very existence—of hu-

man beings depends on how people living today care for the

natural

environment

.

Proper stewardship of the environment affects not only

the health and well-being of people in the future but their

character and identity. In The Economy of the Earth, Mark

Sagoff compares environmental damage to the loss of our

rich cultural heritage. The loss of all our art and literature

would deprive future generations of the benefits we have

enjoyed and render them nearly illiterate. By the same token,

if we destroyed all our wildernesses and dammed all our

rivers, allowing

environmental degradation

to proceed at

the same pace, we would do more than deprive people of

the pleasures we have known. We would make them into

what Sagoff calls “environmental illiterates,” or “yahoos” who

would neither know nor wish to experience the beauties and

pleasures of the natural world. “A pack of yahoos,” says

Sagoff, “will like a junkyard environment” because they will

have known nothing better.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Future generations

The concept of future generations emphasizes both

our ethical and aesthetic obligations to our environment. In

relations between existing and future generations, however,

the present generation holds all the power. While we can

affect them, they can do nothing to affect us. Though, as

some environmental philosophies have argued, our moral

code is in large degree based on reciprocity, the relationship

between generations cannot be reciprocal. Adages such as

“like for like,” and “an eye for an eye,” can apply only among

contemporaries. Since an adequate environmental ethic

would require that moral consideration be extended to in-

clude future people, views of justice based on the norm of

reciprocity may be inadequate.

A good deal of discussion has gone into what an alter-

native environmental ethic might look like and on what it

might be based. But perhaps the important point to note is

609

that the treatment of generations yet unborn has now become

a lively topic of philosophical discussion and political debate.

See also Environmental education; Environmentalism; Inter-

generational justice

[Terence Ball]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Barry, B., and R. I. Sikora, eds. Obligations to Future Generations. Philadel-

phia: Temple University Press, 1978.

Fishkin, J., and P. Laslett, eds. Justice Between Age Groups and Generations.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.

Partridge, E., ed. Responsibilities to Future Generations. Buffalo, NY: Pro-

metheus Books, 1981.

Sagoff, M. The Economy of the Earth: Philosophy, Law and the Environment.

Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

G

Gaia hypothesis

The Gaia hypothesis was developed by British biochemist

James Lovelock, and it incorporates two older ideas. First,

the idea implicit in the ancient Greek term Gaia, that the

earth is the mother of all life, the source of sustenance for

all living beings, including humans. Second, the idea that

life on earth and many of earth’s physical characteristics have

coevolved, changing each other reciprocally as the genera-

tions and centuries pass.

Lovelock’s theory contradicts conventional wisdom,

which holds “that life adapted to the planetary conditions

as it and they evolved their separate ways.” The Gaia hypoth-

esis is a startling break with tradition for many, although

ecologists have been teaching the

coevolution

of organisms

and

habitat

for at least several decades, albeit more often

on a local than a global scale.

The hypothesis also states that Gaia will persevere no

matter what humans do. This is undoubtedly true, but the

question remains: in what form, and with how much diver-

sity? If humans don’t change the nature and scale of some

of their activities, the earth could change in ways that people

may find undesirable—loss of

biodiversity

, more “weed”

species

, increased

desertification

, etc.

Many people, including Lovelock, take the Gaia hy-

pothesis a step further and call the earth itself a living being,

a long-discredited organismic analogy. Recently a respected

environmental science

textbook defined the Gaia hypothe-

sis as a “proposal that Earth is alive and can be considered

a system that operates and changes by feedbacks of informa-

tion between its living and nonliving components.” Similar

sentences can be found quite commonly, even in the scholarly

literature, but upon closer examination they are not persua-

sive. A furnace operates via a positive and negative feedback

system—does that imply it is alive? Of course not. The

important message in Lovelock’s hypothesis is that the health

of the earth and the health of its inhabitants are inextricably

intertwined. See also Balance of nature; Biological commu-

nity; Biotic community; Ecology; Ecosystem; Environment;

611

Environmentalism; Evolution; Nature; Sustainable bio-

sphere

[Gerald L. Young]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Schneider, S. H., and P. J. Boston, eds. Scientists on Gaia. Cambridge:

MIT Press, 1991.

Joseph, L. E. Gaia: The Growth of an Idea. New York: St. Martin’s

Press, 1990.

Lovelock, J. E. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1979.

———. The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth. New York:

Norton, 1988.

P

ERIODICALS

Lyman, F. “What Gaia Hath Wrought: The Story of a Scientific Contro-

versy.” Technology Review 92 (July 1989): 54–61.

Gala

´

pagos Islands

Within the theory of

evolution

, the concept of adaptive

radiation (evolutionary development of several

species

from

a single parental stock) has had as its prime example, a

group of birds known as Darwin’s finches. Charles Darwin

discovered and collected specimens of these birds from the

Gala

´

pagos Islands in 1835 on his five-year voyage around the

world aboard the HMS Beagle. His cumulative experiences,

copious notes, and vast collections ultimately led to the

publication of his monumental work, On the Origin of Species,

in 1859. The Gala

´

pagos Islands and their unique assemblage

of plants and animals were an instrumental part of the devel-

opment of Darwin’s evolutionary theory.

The Gala

´

pagos Islands are located at 90° W longitude

and 0° latitude (the equator), about 600 mi (965 km) west

Ecuador. These islands are volcanic in origin and are about

10 million years old. The original colonization of the Gala

´

pa-

gos Islands occurred by chance transport over the ocean as

indicated by the gaps in the

flora

and

fauna

of this archipel-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gala

´

pagos Islands

ago compared to the mainland. Of the hundreds of species

of birds along the northwestern South American coast, only

seven species colonized the Gala

´

pagos Islands. These evolved

into 57 resident species, 26 of which are endemic to the

islands, through adaptive radiation. The only native land

mammals are a rat and a bat. The land reptiles include

iguanas, a single species each of snake, lizard, and gecko,

and the Gala

´

pagos giant tortoise (Geochelone elephantopus).

No amphibians and few insects or mollusks are found in the

Gala

´

pagos. The flora has large gaps as well—no conifers or

palms have colonized these islands. Many of the open niches

have been filled by the colonizing groups. The tortoises and

iguanas are large and have filled niches normally occupied

by mammalian herbivores. Several plants, such as the prickly

pear cactus, have attained large size and occupy the ecological

position of tall trees.

The most widely known and often used example of

adaptive radiation is Darwin’s finches, a group of 14 species

of birds that arose from a single ancestor in the Gala

´

pagos

Islands. These birds have specialized on different islands or

into niches normally filled by other groups of birds. Some

are strictly seed eaters, while others have evolved more war-

bler-like bills and eat insects, still others eat flowers, fruit,

and/or nectar, and others find insects for their diet by digging

under the bark of trees, having filled the

niche

of the wood-

pecker. Darwin’s finches are named in honor of their discov-

erer, but they are not referred to as Gala

´

pagos finches because

there is one of their numbers that has colonized Cocos

Island, located 425 mi (684 km) north-northeast of the

Gala

´

pagos.

Because of the Gala

´

pagos Islands’ unique

ecology

,

scenic beauty and tropical

climate

, they have become a

mecca for tourists and some settlement. These human activi-

ties have introduced a host ofenvironmental problems, in-

cluding

introduced species

of goats, pigs, rats, dogs, and

cats, many of which become feral and damage or destroy

nesting bird colonies by preying on the adults, young, or

eggs. Several races of giant tortoise have been extirpated or

are severely threatened with

extinction

, primarily due to

exploitation for food by humans, destruction of their food

resources by goats, or predation of their hatchlings by feral

animals. Most of the 13 recognized races of tortoise have

populations numbering only in the hundreds. Three races

are tenuously maintaining populations in the thousands, one

race has not been seen since 1906, but it is thought to

have disappeared due to natural causes, another race has a

population of about 25 individuals, and the Abingdon Island

tortoise is represented today by only one individual, “Lone-

some George,” a captive male at the Charles Darwin Biologi-

cal Station. For most of these tortoises to survive, an active

capture or extermination program of the feral animals will

have to continue. One other potential threat to the Gala

´

pa-

612

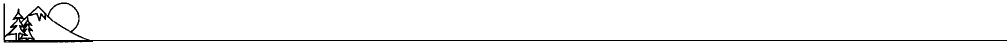

Coastline in the Gala

´

pagos Islands. (Photograph

by Anthony Wolff. Phototake NYC. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

gos Islands is tourism. Thousands of tourists visit these

islands each year and their numbers can exceed the limit

deemed sustainable by the Ecuadoran government. These

tourists have had, and will continue to have, an impact on the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Birute Marija Filomena Galdikas

fragile habitats of the Gala

´

pagos. See also Endemic species;

Ecotourism

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Harris, M. A Field Guide to the Birds of the Gala

´

pagos. London: Collins, 1982.

Root, P., and M. McCormick. Gala

´

pagos Islands. New York: Macmillan,

1989.

Steadman, D. W., and S. Zousmer. Gala

´

pagos: Discovery on Darwin’s Islands.

Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

Birute Marija Filomena Galdikas

(1948 – )

Lithuanian/Canadian primatologist

The world’s leading expert on orangutans, Birute Galdikas

has dedicated much of her life to studying the orangutans

of Indonesia’s Borneo and Sumatra islands. Her work, which

has complemented that of such other scientists as

Dian

Fossey

and

Jane Goodall

, has led to a much greater under-

standing of the primate world and more effective efforts to

protect orangutans from the effects of human infringement.

Galdikas has also been credited with providing valuable in-

sights into human culture through her decades of work with

primates. She discusses this aspect of her work in her 1995

autobiography, Reflections of Eden: My Years with the

Orangutans of Borneo.

Galdikas was born on May 10, 1948 in Wiesbaden in

what was then West Germany, while her family was en

route from their native Lithuania. She was the first of four

children. The family moved to Toronto, Canada when she

was two, and she grew up in that city. As a child, Galdikas

was already enamored of the natural world, and spent much

of her time in local parks and reading books on jungles and

their inhabitants. She was already especially interested in

orangutans. The Galdikas family eventually moved to Los

Angeles, where Birute attended the local campus of the

University of California. She earned a BA there in 1966 and

immediately began work on a master’s degree in anthropol-

ogy. Galdikas had already decided to start a long-term study

of orangutans in the rain forests of Indonesia, where most

of the world’s last remaining wild individuals live.

Galdikas began to realize her dream in 1969 when she

approached famed paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey after

he gave a lecture at UCLA. Leakey had helped launch the

research efforts of Fossey and Goodall, and she asked him

to do the same for her. He agreed, and by 1971 had helped

her raise enough money to get started. With her first hus-

band, Galdikas traveled to southern Borneo’s Tanjung Put-

ing

National Park

in East Kalimantan to start setting up her

613

research station. Such challenges as huge leeches, extremely

toxic plants, perpetual dampness, swarms of insects, and

aggressive viruses slowed Galdikas down, but did not ruin

her enthusiasm for her new project.

After finally locating the area’s elusive

orangutan

population, Galdikas faced the difficulty of getting the shy

animals accustomed enough to her presence that they would

permit her to watch them even from a distance.

Once Galdikas accomplished this, she was able to

begin documenting some of the traits and habits of the little-

studied orangutans. She compiled a detailed list of staples

in the animals’ diets, discovered that they occasionally eat

meat, and recorded their complex behavioral interactions.

Eventually, the animals came to accept Galdikas and

her husband so thoroughly that their camp was often overrun

by them. Galdikas recalled in a 1980 National Geographic

article that she sometimes felt as though she were “sur-

rounded by wild, unruly children in orange suits who had

not yet learned their manners.” Meanwhile, she applied her

findings to her UCLA education, earning both her master’s

degree and doctorate in 1978.

During her first decade on Borneo, Galdikas founded

the Orangutan Project, which has since been funded by

such organizations as the National Geographic Society, the

World Wildlife Fund

, and

Earthwatch

. The Project not

only carries out primate research, but also rehabilitates hun-

dreds of former captive orangutans. She also founded the

Los Angeles-based nonprofit Orangutan Foundation Inter-

national in 1987.

From 1996 to 1998, Galdikas served as a senior adviser

to the Indonesian Forestry Ministry on orangutan issues as

that government attempted to rectify the mistreatment of

the animals and the mismanagement of their dwindling

rain

forest habitat

. As part of these efforts, the Jakarta govern-

ment also helped Galdikas establish the Orangutan Care

Center and Quarantine near Pangkalan Bun, which opened

in 1999. This center has since cared for many of the primates

injured or displaced by the devastating fires in the Borneo

rain forest in 1997–1998.

Divorced in 1979, Galdikas married a native Indone-

sian man of the Dayak tribe in 1981. She has one son with

her first husband and two children with her second. Galdikas

and her second husband currently live in a Dayak village,

but Galdikas travels to Canada once a year to visit her

first son. She became a visiting professor at Simon Fraser

University in 1981, but since then has been appointed full

professor. Besides her work, Galdikas reportedly most enjoys

playing with her children, reading, walking, and listening

to native Indonesian music. She has been featured on such

popular television shows as “Good Morning, America” and

“Eye to Eye,” using such exposure to increase public aware-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Game animal

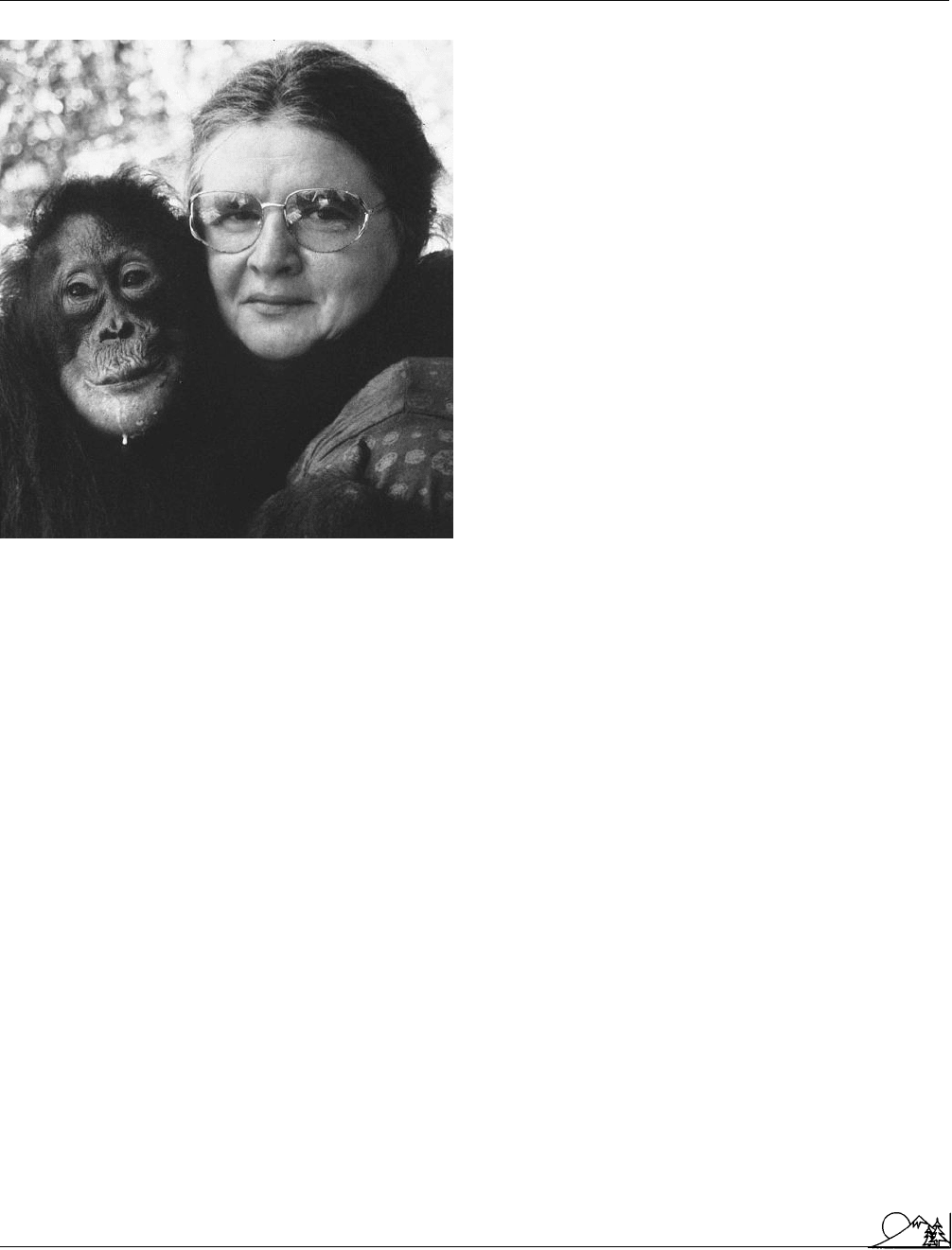

Birute Galdikas being embraced by two orang-

utans in Borneo. (The Liaison Network. ©Liaison

Agency. Reproduced by permission.)

ness of her programs and the danger faced by the world’s

remaining orangutan population.

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Galdikas, Birute. Reflections of Eden: My Years with the Orangutans of Borneo.

Little, Brown: New York, 1995.

Montgomery, Sy. Walking with the Great Apes: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey,

Birute Galdikas. 1991.

Notable Scientists: From 1900 to the Present. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale

Group, 2001.

Game animal

Birds and mammals commonly hunted for sport. The major

groups include upland game birds (quail, pheasant, and par-

tridge), waterfowl (ducks and geese), and big game (deer,

antelope, and bears). Game animals are protected to varying

degrees throughout most of the world, and

hunting

levels

are regulated through the licensing of hunters as well as by

seasons and bag limits. In the United States, state

wildlife

agencies assume primary responsibility for enforcing hunting

regulations, particularly for resident or non-migratory

spe-

cies

. The

Fish and Wildlife Service

shares responsibility

614

with state agencies for regulating harvests of migratory game

animals, principally waterfowl.

Game preserves

Game preserves (also known as game reserves, or

wildlife

refuges) are a type of protected area in which

hunting

of

certain

species

of animals is not allowed, although other

kinds of resource harvesting may be permitted. Game pre-

serves are usually established to conserve populations of

larger game species of mammals or waterfowl. The protec-

tion from hunting allows the hunted species to maintain

relatively large populations within the sanctuary. However,

animals may be legally hunted when they move outside of

the reserve during their seasonal migrations or when search-

ing for additional

habitat

.

Game preserves help to ensure that populations of

hunted species do not become depleted through excessive

harvesting throughout their range. This

conservation

allows the species to be exploited in a sustainable fashion

over the larger landscape.

Although hunting is not allowed, other types of re-

source extraction may be permitted in game reserves, such as

timber harvesting, livestock grazing, some types of cultivated

agriculture, mining, and exploration and extraction of

fossil

fuels

. However, these land-uses are managed to ensure that

the habitat of game species is not excessively damaged. Some

game preserves are managed as true ecological reserves,

where no extraction of

natural resources

is allowed. How-

ever, low-intensity types of land-use may be permitted in

these more comprehensively protected areas, particularly

non-consumptive

recreation

such as hiking and wildlife

viewing.

Game preserves as a tool in conservation

The term “conservation” refers to the wise (i.e., sus-

tainable) use of natural resources. Conservation is particularly

relevant to the use of renewable resources, which are capable

of regenerating after a portion has been harvested. Hunted

species of animals are one type of renewable resource, as are

timber, flowing water, and the ability of land to support the

growth of agricultural crops. These renewable resources have

the potential to be harvested forever, as long as the rate of

exploitation is equal to or less than the rate of regeneration.

However, potentially renewable resources can also be har-

vested at a rate exceeding their regeneration. This is known

as over-exploitation, a practice that causes the stock of the

resource to decline and may even result in its irretrievable

collapse.

Wildlife managers can use game preserves to help

conserve populations of hunted species. Other methods of

conservation of game animals include: (1) regulation of the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Game preserves

time of year when hunting can occur; (2) setting of “bag

limits” that restrict the maximum number of animals that

any hunter can harvest; (3) limiting the total number of

animals that can be harvested in a particular area, and; (4)

restricting the hunt to certain elements of the population.

Wildlife managers can also manipulate the habitat of game

species so that larger, more productive populations can be

sustained, for example by increasing the availability of food,

water, shelter, or other necessary elements of habitat. In

addition, wildlife managers may cull the populations of natu-

ral predators to increase the numbers of game animals avail-

able to be hunted by people.

Some or all of these practices, including the establish-

ment of game preserves, may be used as components of an

integrated game management system. Such systems may be

designed and implemented by government agencies that are

responsible for managing game populations over relatively

large areas such as counties, states, provinces, or entire coun-

tries.

Conservation is intended to benefit humans in their

interactions with other species and ecosystems, which are

utilized as valuable natural resources. When defined in this

way, conservation is very different from the preservation of

indigenous species and ecosystems for their ecocentric and

biocentric values, which are considered important regardless

of any usefulness to humans or their economic activities.

Examples of game preserves

The first

national wildlife refuge

in the United

States was established by President

Theodore Roosevelt

in

1903. This was a breeding site for brown pelicans (Pelecanus

occidentalis) and other birds in Florida. The U.S. national

system of wildlife refuges now totals some 437 sites covering

91.4 million acres (37 million ha); an additional 79 million

acres (32 million ha) of habitat are protected in national

parks and monuments. The largest single wildlife reserve is

the Alaska Maritime Wildlife Refuge, which covers 3.5 mil-

lion acres (1.4 million ha); in fact, about 85% of the national

area of

wildlife refuges

is in Alaska. Most of the national

wildlife refuges protect migratory, breeding, and wintering

habitats for waterfowl, but others are important for large

mammals and other species. Some wildlife refuges have been

established to protect

critical habitat

of

endangered spe-

cies

, such as the Aransas Wildlife Refuge in coastal Texas,

which is the primary wintering grounds of the

whooping

crane

(Grus americana). Since 1934, sales of Migratory Bird

Hunting Stamps, or “duck stamps,” have been critical to

providing funds for the acquisition and management of fed-

eral wildlife refuges in the United States.

Although hunting is not permitted in many National

wildlife refuges, in 1988, closely regulated hunting was per-

mitted in 60% of the refuges, and fishing was allowed in

50%. In addition, some other resource-related activities are

615

allowed in some refuges. Depending on the site, it may be

possible to harvest timber, graze livestock, engage in other

kinds of agriculture, or explore for or mine metals or fossil

fuels. The various components of the multiple-use plans of

particular national wildlife refuges are determined by the

Secretary of the Interior. Any of these economically impor-

tant activities may cause damage to wildlife habitats, and

this has resulted in intense controversy between economic

interests and some environmental groups. Environmental

organizations such as the

Sierra Club

,

Ducks Unlimited

,

and the Audubon Society have lobbied federal legislators to

further restrict exploration and extraction in national wildlife

refuges, but business interests demand greater access to valu-

able resources within national wildlife refuges.

Many states and provinces also establish game pre-

serves as a component of wildlife-management programs on

their lands. For example, many jurisdictions in eastern North

America have set up game preserves for management of

populations of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), a

widely hunted species. Game preserves are also used to con-

serve populations of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and

elk (Cervus canadensis) in more western regions of North

America.

Some other types of protected areas, such as state,

provincial, and national parks are also effective as wildlife

preserves. These protected areas are not primarily established

for the conservation of natural resources—rather, they are

intended to preserve natural ecosystems and wild places for

their

intrinsic value

. Nevertheless, relatively large and pro-

ductive populations of hunted species often build up within

parks and other large ecological reserves, and the surplus

animals are commonly hunted in the surrounding areas.

In addition, many protected areas are established by non-

governmental organizations, such as

The Nature Conser-

vancy

, which has preserved more than 16 million acres (6.5

million ha) of natural habitat throughout the United States.

Yellowstone National Park

is one of the most fa-

mous protected areas in North America. Hunting is not

allowed in Yellowstone, and this has allowed the build-up

of relatively large populations of various species of big-game

mammals, such as white-tailed deer, elk,

bison

(Bison bison),

and

grizzly bear

(Ursus arctos). Because of the large popula-

tions in the park, the overall abundance of game species on

the greater landscape is also larger. This means that a rela-

tively high intensity of hunting can be supported. This is

considered important because it provides local people with

meat and subsistence as well as economic opportunities

through guiding and the marketing of equipment, accommo-

dations, food, fuel, and other necessities to non-local

hunters.

By providing a game-preserve function for the larger

landscape, wildlife refuges and other kinds of protected areas

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gamma ray

help to ensure that hunting can be managed to allow popula-

tions of exploited species to be sustained, while providing

opportunities for people to engage in subsistence and eco-

nomic activities.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Freedman, B. Environmental Ecology. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic

Press, 1995.

Miller, G. T. Resource Conservation and Management. Belmont, CA: Wad-

sworth Publishing Co., 1990.

Owen, O. S., and D. D. Chiras. Natural Resource Conservation. Management

for a Sustainable Future. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995.

Robinson, W.L., and E. G. Bolen. Wildlife Ecology and Management. 3rd

ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1995.

Gamma ray

High energy forms of electromagnetic radiation with very

short wavelengths. Gamma rays are emitted by cosmic

sources or by

radioactive decay

of atomic nuclei which

occurs during nuclear reactions or the detonation of

nuclear

weapons

. Gamma rays are the most penetrating of all forms

of nuclear radiation. They travel about 100 times deeper

into human tissue than beta particles and 10,000 times

deeper than alpha particles. Gamma rays cause chemical

changes in cells through which they pass. These changes

can result in the cells’ death or the loss of their ability to

function properly. Organisms exposed to gamma rays may

suffer illness, genetic damage, or death. Cosmic gamma rays

do not usually pose a danger to life because they are absorbed

as they travel through the

atmosphere

. See also Ionizing

radiation; Radiation exposure; Radioactive fallout

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

(1869 – 1948)

Indian Religious leader

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi led the movement that

freed India from colonial occupation by the British. His

leadership was based not only on his political vision but also

on his moral, economic, and personal philosophies. Gandhi’s

beliefs have influenced many political movements through-

out the world, including the civil rights movement in the

United States, but their relevance to the modern environ-

mental movement has not been widely recognized or under-

stood until recently.

616

In developing the principles that would enable the

Indian people to form a united independence movement, one

of Gandhi’s chief concerns was preparing the groundwork for

an economy that would allow India to be both self-sustaining

and egalitarian. He did not believe that an independent

economy in India could be based on the Western model;

he considered a consumer economy of unlimited growth

impossible in his country because of the huge population

base and the high level of poverty. He argued instead for

the development of an economy based on the careful use of

indigenous

natural resources

. His was a philosophy of

conservation

, and he advocated a lifestyle based on limited

consumption,

sustainable agriculture

, and the utilization

of labor resources instead of imported technological devel-

opment.

Gandhi’s plans for India’s future were firmly rooted

both in moral principles and in a practical recognition of its

economic strengths and weaknesses. He believed that the

key to an independent national economy and a national sense

of identity was not only indigenous resources but indigenous

products and industries. Gandhi made a point of wearing

only homespun, undyed cotton clothing that had been hand-

woven on cottage looms. He anticipated that the practice

of wearing homespun cotton cloth would create an industry

for a product that had a ready market, for cotton was a

resource that was both indigenous and renewable. He recog-

nized that India’s major economic strength was its vast labor

pool, and the low level of technology needed for this product

would encourage the development of an industry that was

highly decentralized. It could provide employment without

encouraging mass

migration

from rural to urban areas, thus

stabilizing rural economies and national demography. The

use of cotton textiles would also prevent dependence on

expensive synthetic fabrics that had to be imported from

Western nations, consuming scarce foreign exchange. He

also believed that synthetic textiles were not suited to India’s

climate

, and that they created an undesirable distinction

between the upper classes that could afford them and the

vast majority that could not.

The essence of his economic planning was a philo-

sophical commitment to living a simple lifestyle based on

need. He believed it was immoral to kill animals for food

and advocated

vegetarianism

; advocated walking and other

simple forms of

transportation

contending that India could

not afford a car for every individual; and advocated the

integration of ethical, political, and economic principles into

individual lifestyles. Although many of his political tactics,

particularly his strategy of civil disobedience, have been

widely embraced in many countries, his economic philoso-

phies have had a diminishing influence in a modern, inde-

pendent India, which has been pursuing sophisticated tech-

nologies and a place in the global economy. But to some,