Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Giardia

The anatomy of the giant panda indicates that it is a

carnivore, however, its diet consists almost entirely of bam-

boo, whose cellulose cannot be digested by the panda. Since

the giant panda obtains so little

nutrient

value from the

bamboo, it must eat enormous quantities of the plant each

day, about 35 lb (16 kg) of leaves and stems, in order to

satisfy its energy requirements. Whenever possible, it feeds

solely on the young succulent shoots of bamboo, which,

being mostly water, requires it to eat almost 90 lb (41 kg)

per day. This translates into 10–12 hours per day that pandas

spend eating. Giant pandas have been known to supplement

their diet with other plants such as horsetail and pine bark,

and they will even eat small animals, such as rodents, if they

can catch them, but well over 95% of their diet consists of

the bamboo plant.

Bamboo normally grows by sprouting new shoots from

underground rootstocks. At intervals from 40 to 100 years,

the bamboo plants blossom, produce seeds, then die. New

bamboo then grows from the seed. In some regions it may

take up to six years for new plants to grow from seed and

produce enough food for the giant panda. Undoubtedly this

has produced large shifts in panda population size over the

centuries. Within the last quarter century, two bamboo flow-

erings have caused the starvation of nearly 200 giant pandas,

a significant portion of the current population. Although

the wildlife reserves contain sufficient bamboo, much of the

vast bamboo forests of the past have been destroyed for

agriculture, leaving no alternative areas to move to should

bamboo blossoming occur in their current range.

Low

fecundity

and limited success in captive breeding

programs in zoos does not bode well for replenishing any

significant losses in the wild population. Although there are

150 pandas in captivity, only about 28% are breeding. In

1999, the first giant panda to live more than a few days

was born in captivity. For the time being, the giant panda

population appears stable, a positive sign for one of the

world’s scarcest and most popular animals.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Nowak, R. M., ed. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 5th ed. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

“China goes High Tech to Help Panda Population.” USA Today, August

13, 2001.

Drew, L. “Are We Loving the Panda to Death?” National Wildlife 27

(1989): 14–17.

“Pandas Still under Threat of Extinction.” USA Today, February 16, 2001.

637

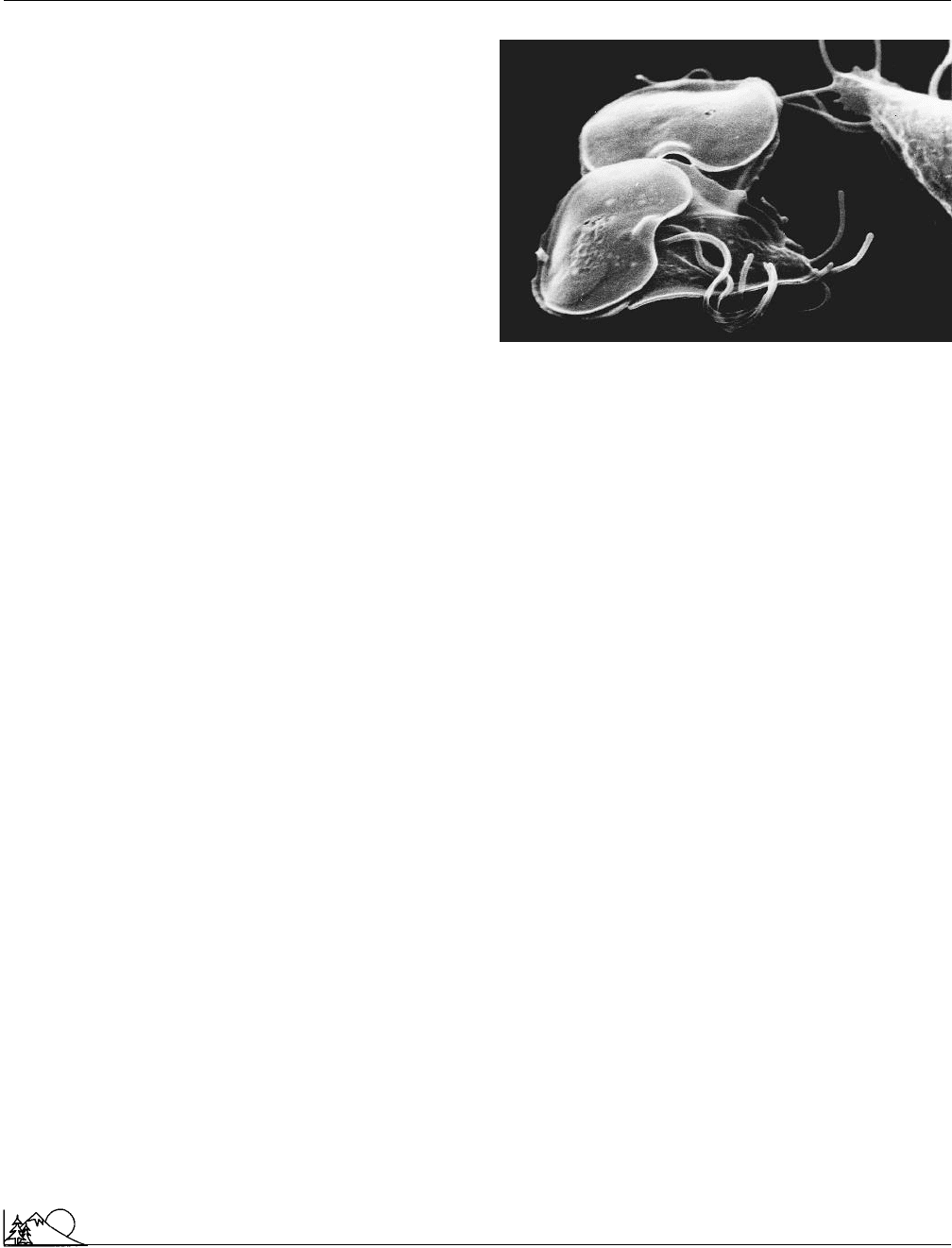

Giardia. (Photograph by J. Paulin. Visuals Unlimited.

Reproduced by permission.)

Giardia

Giardia is the genus (and common) name of a protozoan

parasite in the phylum Sarcomastigophora. It was first de-

scribed in 1681 by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (called “The

Father of Microbiology"), who discovered it in his own stool.

The most common

species

is Giardia intestinalis (also called

lamblia), which is a fairly common parasite found in humans.

The disease it causes is called giardiasis.

The trophozoite (feeding) stage is easily recognized

by its pear-shaped, bilaterally-symmetrical form with two

internal nuclei and four pairs of external flagella; the thin-

walled cyst (infective) stage is oval. Both stages are found

in the upper part of the small intestine in the mucosal lining.

The anterior region of the ventral surface of the troph stage

is modified into a sucking disc used to attach to the host’s

abdominal epithelial tissue. Each troph attaches to one epi-

thelial cell. In extreme cases, nearly every cell will be covered,

causing severe symptoms. Infection usually occurs through

drinking contaminated water. Symptoms include diarrhea,

flatulence (gas), abdominal cramps, fatigue, weight loss, an-

orexia, and/or nausea and may last for more than five days.

Diagnosis is usually done by detecting cysts or trophs of this

parasite in fecal specimens.

Giardia has a worldwide distribution. It is more com-

mon in warm, tropical regions than in cold regions. Hosts

include

frogs

, cats, dogs, beaver, muskrat, horses, and hu-

mans. Children as well as adults can be affected, although it

is more common in children. It is highly contagious. Normal

infection rate in the United States ranges from 1.5 to 20%. In

one case involving scuba divers from the New York City police

and fire fighters, 22–55% were found to be infected, presum-

ably after they accidentally drank contaminated water in the

local rivers while diving. In another case, an epidemic of giar-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gibbons

diasis occurred in Aspen, Colorado, in 1965 during the popu-

lar ski season and 120 people were infected. Higher infection

rates are common in some areas of the world, including Iran

and countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Giardia can typically withstand sophisticated forms of

sewage treatment

, including

filtration

and

chlorination

.

It is therefore hard to eradicate and may potentially increase

in polluted lakes and rivers. For this reason, health officials

should make concerted efforts to prevent contaminated feces

from infected animals (including humans) from entering

lakes used for drinking water.

The most effective treatment for giardiasis is the drug

Atabrine (quinacrine hydrochloride). Adult dosage is 0.1 g

taken after meals three times each day. Side effects are rare

and minimal. See also Cholera; Coliform bacteria

[John Korstad]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Markell, E. K., M. Voge, and D. T. John. Medical Parasitology. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1992.

Schmidt, G. D., and L. S. Roberts. Foundations of Parasitology. 4th ed. St.

Louis: Times Mirror/Mosby, 1989.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Information for

International Travel. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Of-

fice, 1991.

Gibbons

Gibbons (genus Hylobates, meaning “dweller in the trees")

are the smallest members of the ape family which also in-

cludes gorillas,

chimpanzees

, and orangutans. They spend

most of their lives at the tops of trees in the jungle, eating

leaves and fruit. They are extremely agile, swinging at speeds

of 35 mph (56 km/h) with their long arms on branches to

move from tree to tree. The trees can even be 50 ft (15 m)

apart. They have no tails and are often seen walking upright

on tree branches. Gibbons are known for their loud calls

and songs, which they use to announce their territory and

warn away others. They are devoted parents, raising usually

one or two offspring at a time and showing extraordinary

affection in caring for them. Conservationists and animal

protectionists who have worked with gibbons describe them

as extremely intelligent, sensitive, and affectionate.

Gibbons have long been hunted for food, for medical

research, and for sale as pets and

zoo

specimens. A common

method of collecting them is to shoot the mother and capture

the nursing or clinging infant, if it is still alive. The

mortality

rate in collecting and transporting gibbons to areas where

they can be sold is extremely high. This, coupled with the

fact that their jungle

habitat

is being destroyed at a rate of

638

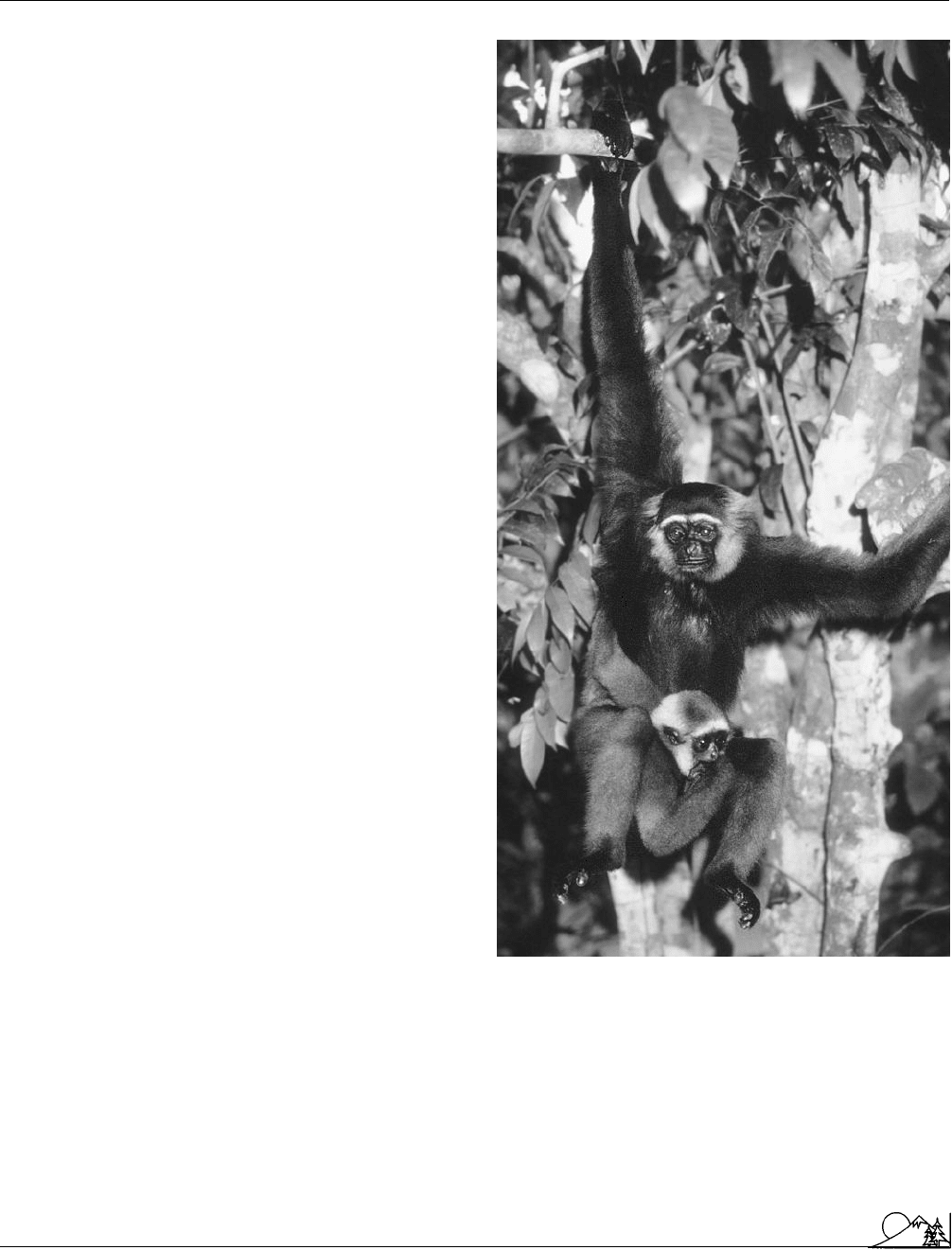

A gibbon. (©Breck P. Kent/JLM Visuals. Reproduced by

permission.)

32 acres (13 ha) per minute, has resulted in severe depletion

of their numbers.

Gibbons are found in southeast Asia, China, and In-

dia, and nine

species

are recognized. All nine species are

considered endangered by the

U.S. Department of the Inte-

rior

and are listed in the most endangered category of the

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lois Marie Gibbs

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Spe-

cies of Wild Fauna and Flora

(CITES).

IUCN—The World

Conservation Union

considers three species of gibbon to

be endangered and two species to be vulnerable. Despite the

ban on international trade in gibbons conferred by listing

in Appendix I of CITES, illegal trade in gibbons, particularly

babies, continues on a wide scale in markets throughout Asia.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Benirschke, K. Primates: The Road to Self-sustaining Populations. New York:

Springer-Verlag, 1986.

Preuschoft, H., et al. The Lesser Apes: Evolutionary and Behavioral Biology.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1984.

O

THER

International Center for Gibbon Studies. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.gib-

boncenter.org>.

Lois Marie Gibbs (1951 – )

American environmentalist and community organizer

An activist dedicated to protecting communities from haz-

ardous wastes, Lois Gibbs began her political career as a

housewife and homeowner near the

Love Canal

, New York.

She was born in Buffalo on June 25, 1951, the daughter of

a bricklayer and a full-time homemaker. Gibbs was 21 and

a mother when she and her husband bought their house

near a buried dump containing hazardous materials from

industry and the military, including wastes from the research

and manufacture of chemical weapons.

From the time the first articles about Love Canal

began appearing in newspapers in 1978, Gibbs has petitioned

for state and federal assistance. She began when she discov-

ered the school her son was attending had been built directly

on top of the buried canal. Her son had developed epilepsy

and there were many similar, unexplained disorders among

other children at the school, yet the superintendent was

refusing to transfer anyone. The New York State Health

Department then held a series of public meetings in which

officials appeared more committed to minimizing the com-

munity perception of the problem than to solving the prob-

lem itself. The governor made promises he was unable to

keep, and Gibbs herself was flown to Washington to appear

at the White House for what she later decided was little

more than political grandstanding. In the book she wrote

about her experience, Love Canal: My Story, Gibbs describes

her frustration and her increasing disillusionment with gov-

639

ernment, as the threats to the health of both adults and

children in the community became more obvious and as it

became clearer that no one would be able to move because

no one could sell their homes.

While state and federal agencies delayed, the media

took an increasing interest in their plight, and Gibbs became

more involved in political action. To force federal action,

Gibbs and a crowd of supporters took two officers from

the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) hostage. A

group of heavily armed FBI agents occupied the building

across the street and gave her seven minutes before they

stormed the offices of the Homeowners’ Association, where

the men were being held. With less than two minutes left

in the countdown, Gibbs appeared outside and released the

hostages in front of a national television audience. By the

middle of the next week, the EPA had announced that

the Federal Disaster Assistance Administration would fund

immediate evacuation for everyone in the area.

But the families who left the Love Canal area still

could not sell their homes, and Gibbs fought to force the

federal government to purchase them and underwrite low-

interest loans. After she accused President Jimmy Carter of

inaction on a national talk show, in the midst of an ap-

proaching election, he agreed to purchase the homes. But

he refused to meet with her to discuss the loans. Carter

signed the appropriations bill in a televised ceremony at the

Democratic National Convention in New York City, and

Gibbs simply walked onstage in the middle of it and repeated

her request for mortgage assistance. The president could do

nothing but promise his political support, and the assistance

she had been asking for was soon provided.

Gibbs was divorced soon after her family left the Love

Canal area. She moved to Washington D.C. with her two

children and founded the Citizen’s Clearinghouse for Haz-

ardous Wastes in 1981 (later renamed the Center for Health,

Environment and Justice in 1997). Its purpose is to assist

communities in fighting toxic waste problems, particularly

plans for toxic waste dumping sites, and the organization

has worked with over 7,000 neighborhood and community

groups. Gibbs has also published Dying from Dioxin, A Citi-

zen’s Guide to Reclaiming Our Health and Rebuilding Democ-

racy. She has appeared on many television and radio shows

and has been featured in hundreds of newspaper and maga-

zine articles. Gibbs has also been the subject of several docu-

mentaries and television movies. She often speaks at confer-

ences and seminars and has been honored with numerous

awards, including the prestigious Goldman Environmental

Prize in 1991. Because of Gibbs’ activist work, no commer-

cial sites for hazardous wastes have been opened in the

United States since 1978.

[Lewis G. Regenstein and Douglas Smith]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Gill nets

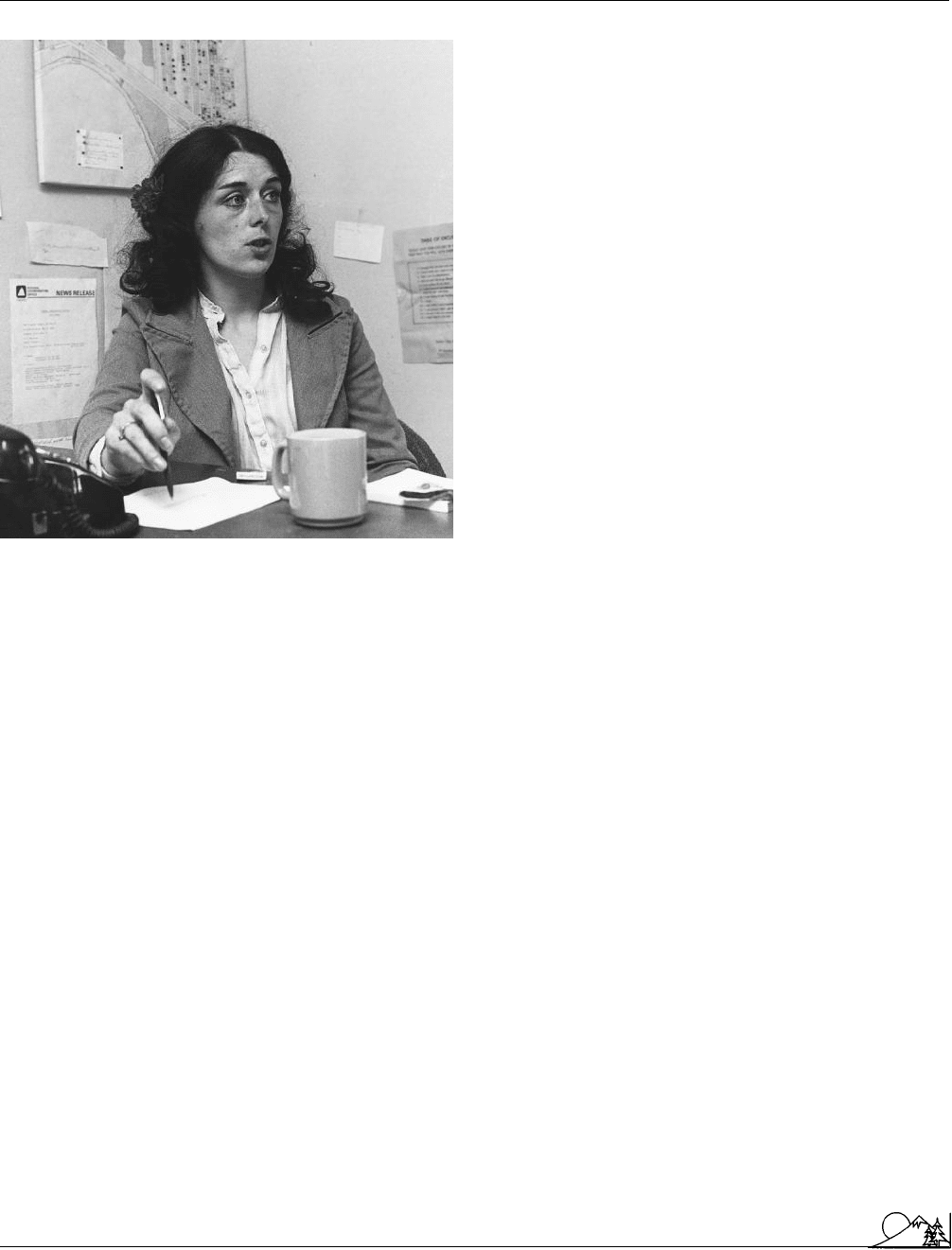

Lois Gibbs at her desk during her fight to win

permanent relocation for the families living at

Love Canal. (Corbis-Bettmann. Reproduced by per-

mission.)

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gibbs, L. Love Canal: My Story. Albany: State University of New York

Press, 1982.

Wallace, A. Eco-Heroes. San Francisco: Mercury House, 1993.

Gill nets

Gill nets are panels of diamond-shaped mesh netting used

for catching fish. When fish attempt to swim through the

net their gill covers get caught and they cannot back out.

Depending on the

target species

, different mesh sizes are

available for use. The top line of the net has a series of floats

attached for buoyancy, and the bottom line has

lead

weights

to hold the net vertically in the water column.

Gill nets have been in use for many years. They became

popular in commercial fisheries in the nineteenth century,

evolving from cotton twine netting to the more modern

nylon twine netting and monofilament nylon netting. As

with many other aspects of

commercial fishing

, the use of

gill nets has developed from minor utilization to a major

environmental issue. Coupled with

overfishing

, the use of

gill nets has caused serious concern throughout the world.

640

Because gill nets are so efficient at catching fish, they

are just as efficient at catching many non-target

species

,

including other fishes,

sea turtles

, sea mammals, and sea

birds. Gill nets have been used extensively in the commercial

fishery for

salmon

and capelin (Mallotus villosus).

Dolphins

,

seals

, and sea otters (Enhydra lutris) get tangled in the nets,

as do diving sea birds such as murres, guillemots, auklets,

and puffins that rely on capelin as a mainstay in their diet.

Sea turtles are also entangled and drown.

The problem has gotten worse over the last decade

with the introduction and extensive use, primarily by foreign

fishing fleets, of drift nets. Described as “the most indiscrim-

inate killing device used at sea,” drift nets are monofilament

gill nets up to 40 mi (64 km) in length. Left at sea for several

days and then hauled on board a fishing vessel, these drift

nets contain vast numbers of dead marine life, besides the

target species, that are simply discarded over the side of the

boat. The outrage expressed regarding these “curtains of

death” led to a United Nations resolution banning their use

in commercial fisheries after the end of 1992. Commercial

fishermen who use other types of nets for catching fish, such

as the purse seines used in the tuna fishing industry and the

bag trawls used in the shrimping industry, have modified

their nets and fishing techniques to attempt to eliminate the

killing of dolphins and sea turtles, respectively. Unfortu-

nately, such modifications of gill nets are nearly impossible

due to the nets’ design and the way these nets are used. See

also Turtle excluder device

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Norris, K. “Dolphins in Crisis.” National Geographic 182 (1992): 2–35.

GIS

see

Geographic information systems

Glaciation

The covering of the earth’s surface with glacial ice. The term

also includes the alteration of the surface of the earth by

glacial

erosion

or deposition. Due to the passage of time,

ice erosion can be almost unidentifiable; the

weathering

of hard rock surfaces often eliminates minor scratches and

other evidence of such glacial activities as the carving of deep

valleys. The evidence of deposition, known as depositional

imprints, can vary. It may consist of specialized features a

few meters above the surrounding terrain, or it may consist

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Henry A. Gleason

of ground materials several meters in thickness covering wide

areas of the landscape.

Only 10% of the earth’s surface is currently covered

with glacial ice, but it is estimated that 30% had been covered

with glacial ice at some time. During the last major glacial

period, most of Europe and more than half of the North

American continent were covered with ice. The glacial ice

of modern day is much thinner than it was in the

ice age

,

and the majority of it (85%) is found in

Antarctica

. About

11% of the remaining glacial ice is in Greenland, and the

rest is scattered in high altitudes throughout the world.

Moisture and cold temperatures are the two main fac-

tors for the formation of glacial ice. Glacial ice in Antarctica

is the result of relatively small quantities of snow deposition

and low loss of ice because of the cold

climate

. In the middle

and low latitudes where the loss of ice, known as ablation,

is higher, snowfall tends to be much higher and the glaciers

are able overcome ablation by generating large amounts of

ice. These types of systems tend to be more active than the

glaciers in Antarctica, and the most active of these are often

located at high altitudes and in the path of prevailing winds

carrying marine moisture.

The

topography

of the earth has been shaped by glaci-

ation. Hills have been reduced in height and valleys created

or filled in the movement of glacial ice. Moraine is a French

term used to describe the ridges and earthen dikes formed near

the edges of regional glaciers. Ground moraine is material that

accumulates beneath a glacier and has low-relief characteris-

tics, and end moraine is material that builds up along the ex-

tremities of a glacier in a ridge-like appearance.

In England, early researchers found stones that were

not common to the local ground rock and decided they must

have “drifted” there, carried by icebergs on water. Though

geology has changed since that time, the term remains and

all deposits made by glacial ice are usually identified as drift.

These glacial deposits, also known as till, are highly varied

in composition. They can be a fine grained deposit, or very

coarse with rather large stones present, or a combination

of both.

Rock and other soil-like debris are often crushed and

ground into very small particles, and they are commonly

found as

sediment

in waters flowing from a glacial mass.

This material is called glacial flour, and it is carried down-

stream to form another kind of glacial deposit. During cer-

tain cold, dry periods of the year winds can pick up portions

of this deposit and scatter it for miles. Many of the different

soils in the American “Corn Belt” originated in this way,

and they have become some of the more important agricul-

tural soils in the world.

[Royce Lambert]

641

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Flint, R. F. Glacial and Pleistocene Geology. New York: Wiley, 1972.

Henry A. Gleason (1882 – 1975)

American ecologist

Henry A. Gleason was a half generation after that small

group of midwesterners who founded

ecology

as a discipline

in the United States. He was a student of

Stephen Forbes

and his early work in ecology was influenced strongly by

Cowles and

Frederic E. Clements

. He did later, however, in

1935, claim standing—bowing only to Cowles and Clements

and for some reason not including Forbes—as “the only

other original ecologist in the country.” And he was original.

His work built on that of the founders, but he quickly and

actively questioned their ideas and concepts, especially those

of Clements, in the process creating controversy and polar-

ization in the ecological community. Gleason called himself

an “ecological outlaw” and probably over-emphasized his

early lack of acceptance in ecology, but in a resolution of

respect from the Ecological Society of America after his

death, he was described as a revolutionary and a heretic for

his skepticism toward ’established’ ideas in ecology. Stanley

Cain said that Gleason was never “impressed nor fooled by

the philosophical creations of other ecologists, for he has

always tested their ideas concerning the association,

succes-

sion

, the climax, environmental controls, and

biogeogra-

phy

against what he knew in

nature

.” Gleason was a critical

rather than negative thinker and never fully rejected the

utility of the idea of community, but the early marginaliza-

tion of his ideas by mainstream ecologists, and the contro-

versy they created, may have played a role in his later concen-

tration on taxonomy over ecology.

He claimed that if plant associations did exist, they

were individualistic and different from area to area, even

where most of the same species were present. Gleason did

clearly reject, however, Clements’ idea of a monoclimax,

proclaiming that “the Clementsian concept of succession, as

an irreversible trend leading to the climax, was untenable.”

His field observations also led him to repudiate Clements’

organismic concept of the plant community, asking “are we

not justified in coming to the general conclusion, far removed

from the prevailing opinion, that an association is not an

organism?” He went on to say that it is “scarcely even a

vegetation unit.” He also pointed out the errors in ’Raunki-

aer’s Law,’ on frequency distribution, which as Robert McIn-

tosh noted, was “widely interpreted [in early ecology] as

being a fundamental community characteristic indicating

homogeneity,” and questioned Jaccard’s comparison of two

communities through a coefficient of similarity that Gleason

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Henry A. Gleason

believed unduly gave as much weight to rare as to common

species.

Gleason’s own approach to the study of vegetation

emerged from his skills as a floristic botanist, an approach

rejected as “old botany” by the founders of ecology. As

Nicolson suggests, “a floristic approach entailed giving pri-

macy to the study of the individual plants and their species.

This was the essence of [Gleason’s] individualistic concept.”

In hindsight, somewhat ironically then, Gleason used old

botany to create a new alternative to what had quickly be-

come dogma in ecology, the centrality of the idea that units

of vegetation were real, that the plant association was indis-

pensable to an ecological approach.

Clements was more accepted in the early part of the

twentieth century than Gleason, though many ecologists at

the time considered both too extreme, just in opposite ways.

Today, Clements’ theories remain out of favor and some of

Gleason’s have been revived, though not all of them. Con-

trary to his own observations, he was persuaded that plants

are distributed randomly, at least over small areas, which is

seldom if ever the case, though he later backed away from

this assertion. He could not accept the theory of continental

drift, stating that “the theory requires a shifting of the loca-

tion of the poles in a way which does considerable violence

to botanical and geological facts,” and therefore should have

few adherents among botanists.

Despite Gleason’s skepticism about some of Clements’

major ideas, the older botanist was a major influence, espe-

cially early in Gleason’s career. Especially influential was

Clements’ rudimentary development of the quadrat method

of sampling vegetation, which shaped Gleason’s approach

to field work; Gleason took the method much further than

Clements, and though not trained in mathematics, was the

first ecologist to employ a number of quantitative approaches

and methods. As McIntosh demonstrated, Gleason, follow-

ing Forbes lead in aquatic ecology “was clearly one of the

earliest and most insightful proponents of the use of quanti-

tative methods in terrestrial ecology.”

Gleason was born in the heart of the area where ecol-

ogy first flourished in the United States. His interest in

vegetation and his contributions to ecology were both stimu-

lated by growing up in and doing research on the dynamics

of the prairie-forest border. He won bachelor’s and master’s

degrees from the University of Illinois and a Ph.D. from

Columbia University. He returned to the University of Illi-

nois as an instructor in botany (1901–1910), where he

worked with Stephen Forbes at one of the major American

centers of ecological research at the time. In 1910, he moved

to the University of Michigan (1910) and while in Ann

Arbor, married Eleanor Mattei. Then, in 1919, he moved

to the New York Botanical Garden, where he spent the rest

of his career, sometimes (reluctantly) as an administrator,

642

always as a research taxonomist. He retired from the Garden

in 1951.

Moving out of the Midwest, Gleason also moved out

of ecology. Most of his work at the Botanic Garden was

taxonomic. He did some ecological work, such as a three-

month ecological survey of Puerto Rico in 1926, and a re-

statement of his “individualistic concept of the plant associa-

tion, (also in 1926 and also in the Bulletin of the Torrey

Botanical Club), in which he posed what Nicolson described

as “a radical challenge” to the basis of contemporary ecologi-

cal practice. Gleason’s challenge to his colleagues and critics

in ecology was to “demolish our whole system of arrangement

and classification and start anew with better hope of success.”

His reasoning was that ecologists had “attempted to arrange

all our facts in accordance with older ideas, and have come

as a result into a tangle of conflicting ideas and theories.”

He anticipated twenty-first century thinking that identifica-

tion on the ground of community and ecosystem as ecological

units is arbitrary, noting that vegetation was too continuously

varied to identify recurrent associations. He claimed, for

example, that “no ecologist would refer the alluvial forests

of the upper and lower Mississippi to the same association,

yet there is no place along their whole range where one

can logically mark a boundary between them. As Mcintosh

suggests, “one of Gleason’s major contributions to ecology

was that he strove to keep the conceptual mold from harden-

ing prematurely.”

In his work as a taxonomist for the Garden, Gleason

traveled as a plant collector, becoming what he described as

“hooked” on tropical American botany, specializing in the

large family of melastomes, tropical plants ranging from

black mouth fruits to handsome cultivated flowers, a group

which engaged him for the rest of his career. His field work,

on this family but especially many others, was reinforced by

extensive study and identification on material collected by

others and made available to him at the Garden.

A major assignment during his New York years, em-

blematic of his work as a taxonomist, was a revision of the

Britton and Brown Illustrated Flora of the Northeastern United

States (1952) which Maguire describes as a “heavy duty [that]

intervened and essentially brought to a close Gleason’s excel-

lent studies of the South American floras and [his] detailed

inquiry into the Melastomataceae...this great work...occu-

pied some ten years of concentrated, self-disciplined atten-

tion.” He did publish a few brief pieces on the melastomes

after the Britton and Brown, and also two books with Arthur

Cronquist, Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United

States and Adjacent Canada (1963) and the more general The

Natural Geographyof Plants (1964). The latter, though co-

authored, was an overt attempt by Gleason to summarize a

life’s work and make it accessible to a wider public.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Glen Canyon Dam

Gleason’s early ecological work on species-area rela-

tions, the problem of rare species, and his extensive taxo-

nomic work all laid an initial base for contemporary concern

among biologists (especially) about the threat to the earth’s

bio-diversity. Gleason wrote that analysis of “the various

species in a single association would certainly show that

their optimum environments are not precisely identical,” a

foreshadowing of later work on niche separation.

McIntosh claimed in 1975 that Gleason’s individual-

istic concept “must be seen not simply as one of historical

interest but very likely as one of the key concepts of modern

and, perhaps, future ecological thought.” A revival of Glea-

son’s emphasis on the individual at mid-twentieth century

became one of the foundations for what some scientists in

the second half of the twentieth century called a “new ecol-

ogy,” one that rejects imposed order and system and empha-

sizes the chaos, the randomness, the uncertainty and the

unpredictability of natural systems. A call for ’adaptive’ re-

source and environmental management policies flexible

enough to respond to unpredictable change in individually

variant natural systems is one outgrowth of such changes in

thinking in ecology and the

environmental sciences

.

[Gerald L. Young]

F

URTHER

R

EADING

B

OOKS

Gleason, H. A. “Twenty-Five Years of Ecology, 1910–1935.” Vol. 4, Mem-

oirs, Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 1936.

P

ERIODICALS

Cain, Stanley A. “Henry Allan Gleason: Eminent Ecologist 1959.” Bulletin

of the Ecological Society of America 40, no. 4 (December 1959): 105–110.

Gleason, H. A. “Delving Into the History of American Ecology—Reprint

of 1952 Letter to C. H. Muller.” The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of

America 56, no. 4 (December 1975): 7–10.

Maguire, Bassett. “Henry Allan Gleason—1881–1975.” Bulletin of the Tor-

rey Botanical Club 102, no. 5 (September/October 1975): 274–282.

McIntosh, Robert P. “H.A. Gleason—"Individualistic Ecologist” 1882–

1975: His Contributions to Ecological Theory.” Bulletin of the Torrey Botan-

ical Club 102, no. 5 (September/October 1975): 253–273.

Nicolson, Malcolm. “Henry Allan Gleason and the Individualistic Hypoth-

esis: The Structure of a Botanist’s Career.” The Botanical Review 56, no.

2 (April/June 1990): 91–161.

Glen Canyon Dam

Until 1963, Glen Canyon was one of the most beautiful

stretches of natural scenery in the American West. The

canyon had been cut over thousands of years as the

Colorado

River

flowed over sandstone that once formed the floor of

an ancient sea. The colorful walls of Glen Canyon were

often compared to those of the Grand Canyon, only about

50 mi (80 km) downstream.

643

Humans have long seen more than beauty in the can-

yon, however. They have envisioned the potential value of

a water

reservoir

that could be created by damming the

Colorado. In a region where water can be as valuable as

gold, plans for the construction of a giant

irrigation

project

with water from a Glen Canyon dam go back to at least 1850.

Flood control was a second argument for the construc-

tion of such a dam. Like most western rivers, the Colorado

is wild and unpredictable. When fed by melting snows and

rain in the spring, its natural flow can exceed 300,000 ft

4

(8,400 m

4

) per second. At the end of a hot dry summer,

flow can fall to less than 1% of that value. The river’s water

temperature can also fluctuate widely, by more than 36°F

(20°C) in a year. A dam in Glen Canyon held the promise

of moderating this variability.

By the early 1900s, yet a third argument for building

the dam was proposed—the generation of hydroelectric

power. Both the technology and the demand were reaching

the point that power generated at the dam could be supplied

to Phoenix, Los Angeles, San Diego, and other growing

urban areas in the Far West.

Some objections were raised in the 1950s when con-

struction of a Glen Canyon Dam was proposed, and environ-

mentalists fought to protect this unique natural area. The

1950s and early 1960s were not, however, an era of high

environmental sensitivity, and plans for the dam eventually

were approved by the U. S. Congress. Construction of the

dam, just south of the Utah-Arizona border, was completed

in 1963 and the new lake it created, Lake Powell, began to

develop. Seventeen years later, the lake was full holding a

maximum of 27 million acre-feet of water.

The environmental changes brought about by the dam

are remarkable. The river itself has changed from a muddy

brown color to a clear crystal blue as the sediments it carries

are deposited behind the dam in Lake Powell.

Erosion

of

river banks downstream from the dam has lessened consider-

ably as spring floods are brought under control. Natural

beaches and sandbars, once built up by deposited

sediment

,

are washed away. River temperatures have stabilized at an

annual average of about 50°F (10°C). These physical changes

have brought about changes in

flora

and

fauna

also. Four

species

of fish native to the Colorado have become extinct,

but at least 10 species of birds are now thriving where they

barely survived before. The

biotic community

below the

dam is significantly different from what it was before con-

struction.

During the 1980s, questions about the dam’s operation

began to grow. A number of observers were especially con-

cerned about the fluctuations in flow through the dam, a

pattern determined by electrical needs in distant cities. Dur-

ing peak periods of electrical demand, operators increase the

flow of water though the dam to a maximum of 30,000 ft

4

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Global Environment Monitoring System

(840 m

4

) per second. At periods of low demand, that flow

may be reduced to 1,000 ft

4

(28 m

4

) per second. As a result

of these variations, the river below the dam can change by

as much as 13 ft (4 m) in height in a single 24-hour period.

This variation can severely damage riverbanks and can have

unsettling effects on

wildlife

in the area as, for example,

fish are stranded on the shore or swept away from spawning

grounds. River-rafting is also severely affected by changing

river levels as rafters can never be sure from day to day what

water conditions they may encounter.

Operation of the Glen Canyon Dam is made more

complex by the fact that control is divided up among at least

three different agencies in the U. S. Department of the

Interior, the

Bureau of Reclamation

, the

Fish and Wildlife

Service

, and the

National Park Service

, all with somewhat

different missions. In 1982, a comprehensive re-analysis of

the Glen Canyon area was initiated. A series of environmen-

tal studies called the Glen Canyon Environmental Studies

were designed and carried out over much of the following

decade. In addition, Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan an-

nounced in 1989 that an

environmental impact statement

on the downstream effects of the dam would be conducted.

The purpose of the environmental impact statement

was to find out if other options were available for operating

the dam that would minimize harmful effects on the

envi-

ronment

, recreational opportunities, and Native American

activities while still allowing the dam to produce sufficient

levels of hydroelectric power. The effects studied included

water, sediment, fish, vegetation, wildlife and

habitat

, en-

dangered and other special-status species, cultural resources,

air quality

,

recreation

, hydropower, and non-use value

(i.e., general appreciation of

natural resources

).

Nine different operating options for the dam were

considered. These options fell into three general categories:

unrestricted fluctuating flows (two alternative modes); re-

stricted fluctuating flows (four modes); and steady flows

(three modes).

The final choice made was one that involves “periodic

high, steady releases of short duration” that reduce the dam’s

performance significantly below its previous operating level.

The criterion for this decision was the protection and en-

hancement of downstream resources while continuing to

permit a certain level of flexibility in the dam’s operation.

A later series of experiments was designed to see what

could be done to restore certain downstream resources that

have been destroyed or damaged by the dam’s operation.

Between March 26 and April 2, 1996, the U.S. Bureau of

Reclamation

released unusually large amounts of water from

the dam. The intent was to reproduce the large scale

flood-

ing

on the Colorado River that had normally occurred every

spring before the dam was built.

644

The primary focus of this project was to see if down-

stream sandbars could be restored by the flooding. The

sandbars have traditionally been used as campsites and have

been a major mechanism for the removal of

silt

from backwa-

ter channels used by native fish. Depending on the final

results of this study, the Bureau will determine what changes,

if any, should be taken in adjusting flow patterns over the

dam to provide for maximum environmental benefit down-

stream along with power output. See also Alternative energy

sources; Riparian land; Wild river

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Elfring, C. “Conflict in the Grand Canyon.” BioScience (November 1990):

709–711.

Udall, J. R. “A Wild, Swinging River.” Sierra (May 1990): 22–26.

Global Environment Monitoring

System

A data-gathering project administered by the

United Na-

tions Environment Programme

. The Global Environment

Monitoring System (GEMS) is one aspect of the modern

understanding that environmental problems ranging from

the

greenhouse effect

and

ozone layer depletion

to the

preservation of

biodiversity

are international in scope. The

system was inaugurated in 1975, and it monitors weather

and

climate

changes around the world, as well as variations

in soils, the health of plant and animal

species

, and the

environmental impact of human activities.

GEMS was not intended to replace any existing sys-

tems; it was designed to coordinate the collection of data

on the environment, encouraging other systems to supply

information it believed was being omitted. In addition to

coordinating the gathering of this information, the system

also publishes it in an uniform and accessible fashion, where

it can be used and evaluated by environmentalists and policy

makers.

GEMS operates 25 information networks in over 142

countries. These networks monitor

air pollution

, including

the release of

greenhouse gases

and changes in the

ozone

layer, and

air quality

in various urban center; they also

gather information on

water quality

and food contamina-

tion in cooperation with the World Health Organization

and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Global Releaf

Global Forum

The Global Forum of Spiritual and Parliamentary Leaders

on Human Survival is a worldwide organization of scien-

tists, leaders of world religions, and parliamentarians who

are attempting to change environmental and developmental

values in their countries. Members include local, national,

and international leaders in the arts, business, community

action, education, faith, government, media, and youth

sectors.

Historically, lawmakers and spiritual leaders have

differed in their views toward stewardship of the earth.

A conference held in Oxford, England, in 1988, and

attended by 200 spiritual and legislative leaders brought

these groups together with scientists to discuss solutions

to worldwide environmental problems. Speakers included

the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa, and the Archbishop of

Canterbury, who conferred with experts such as Carl

Sagan, Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai, and

Gaia hypothesis

scientist James Lovelock. As a result of

the Oxford conference, the Soviet Union invited the Global

Forum to convene an international meeting on critical

survival issues. The Moscow conference, called the Global

Forum on Environment and Development, took place in

January 1990. Over 1,000 spiritual and parliamentary lead-

ers, scientists, artists, journalists, businessmen, and young

people from eighty-three countries attended the Moscow

Forum. One initiative of the Moscow Forum was a joint

commitment by scientists and religious leaders to preserve

and cherish the earth.

The Global Forum tries not to duplicate the activities

of other environmental groups but works to relate global

issues to local environments. For example, participants at

the first U.S.-based Global Forum conference in Atlanta in

May 1992, learned about the local effects of global problems

such as

tropical rain forest

destruction, global warming,

and

waste management

. The Global Forum has initiated

seminars worldwide on ethical implications of the environ-

mental crisis. Artists learn about the role of the arts in

communicating global survival issues. Business leaders pro-

mote

sustainable development

at the highest levels of

business and industry. Young people petition their schools

to include curriculum on environmental issues as required

subjects.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Global Forum, East 45th St., 4th Floor , New York , NY USA 10017

645

Global Releaf

Global Releaf, an international citizen action and education

program, was initiated in 1988 by the 115-year-old Ameri-

can Forestry Association in response to the worldwide con-

cern over global warming and the

greenhouse effect

. Cam-

paigning under the slogan “Plant a tree, cool the globe,” its

over 112,000 members began the effort to reforest the earth

one tree at a time.

In 1990, Global Releaf began Global Releaf Forest,

an effort to restore damaged

habitat

on public lands through

tree plantings Global Releaf Fund is its urban counterpart.

Using each one-dollar donation to plant one tree resulted

in the planting of more than four million trees on 70 sites

in 33 states. By involving local citizens and resource experts

in each project, the program ensures that the right

species

are planted in the right place at the right time. Results

include the protection of endangered and threatened ani-

mals, restoration of native species, and improvement of rec-

reational opportunities.

Funding for the program has come largely from gov-

ernment agencies, corporations, and non-profit organiza-

tions. Chevrolet-Geo celebrated the planting of its millionth

tree in October 1996. The Texaco/Global Releaf Urban

Tree Initiative, utilizing more than 6,000 Texaco volunteers,

has helped local groups plant more than 18,000 large trees

and invested over $2.5 million in projects in twelve cities.

Outfitter Eddie Bauer began an “Add a Dollar, Plant a Tree”

program to fund eight Global Releaf Forest sites in the

United States and Canada, planting close to 350,000 trees.

The Global Releaf Fund also helps finance urban and

rural reforestation on foreign

soil

in projects undertaken with

its international partners. Engine manufacturer, Briggs &

Stratton, for example, has made possible tree plantings both

in the United States and in Ecuador, England, Germany,

Poland, Romania, Slovakia, South Africa, and Ukraine,

while Costa Rica, Gambia, and the Philippines have benefit-

ted from picture-frame manufacturer Larsen-Juhl.

Unfortunately, not enough funding exists to grant all

the requests; in 1996, only 40% of the proposed projects

received financial backing. Forced to pick and choose, the

review board favors those projects which aim to protect

endangered and threatened species. Burned forests and natu-

ral disaster areas—like the Francis Marion

National Forest

in South Carolina, devastated by 1989’s

Hurricane

Hugo—

are also high on the priority list, as are streamside woodlands

and landfills.

Looking to the future, Global Releaf 2000 was

launched in 1996 with the aim of encouraging the planting

of 20 million trees, increasing the canopy in select cities by

20%, and expanding the program to include private lands

and sanitary landfills. A 20-city survey done in 1985 by

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Goiter

American Forests

showed that four trees die for every one

planted in United States cities and that the average city tree

lives only 32 years (just seven years, downtown). With these

facts in mind, Global Releaf asks that communities plant

twice as many trees as are lost in the next decade. In August

of 2001, more than 19 million trees had been planted.

[Ellen Link]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Sobel K. L., S. Orrick, and R. Honig. Environmental Profiles: A Global

Guide to Projects and People. New York: Garland, 1993.

P

ERIODICALS

“Global Releaf 2000.” American Forests 103, no. 4 (Autumn 1996): 30.

“A Helping Hand for Damaged Land.” American Forests 102, no. 3 (Summer

1996): 33–35.

“Planting One for the Millennium.” American Forests 102, no. 3 (Summer

1996): 13–15.

O

RGANIZATIONS

American Forests, P.O. Box 2000, Washington , D.C. USA 20013 (202)

955-4500, Fax: (202) 955-4588, Email: info@amfor.org, <http://

www.americanforests.org>

Global 2000 Report

see The Global 2000 Report

Global warming

see

Greenhouse effect

GOBO

see

Child survival revolution

Goiter

Generally refers to any abnormal enlargement of the thyroid

gland. The most common type of goiter, the simple goiter,

is caused by a deficiency of iodine in the diet. In an attempt

to compensate for this deficiency, the thyroid gland enlarges

and may become the size of a large softball in the neck. The

general availability of table salt to which potassium iodide

has been added ("iodized” salt) has greatly reduced the inci-

dence of simple goiter in many parts of the world. A more

serious form of goiter, toxic goiter, is associated with hyper-

thyroidism. The etiology of this condition is not well under-

stood. A third form of goiter occurs primarily in women and

is believed to be caused by changes in hormone production.

Golf courses

The game of golf appears to be derived from ancient stick-

and-ball games long played in western Europe. However,

646

the first documented rules of golf were established in 1744,

in Edinburgh, Scotland. Golf was first played in the United

States in the 1770s, in Charleston, South Carolina. It was

not until the 1880s, however, that the game began to become

widely popular, and it has increasingly flourished since then.

In 2002, there were about 16,000 golf courses in the United

States, and thousands more in much of the rest of the world.

Golf is an excellent form of outdoor

recreation

. There

are many health benefits of the game, associated with the

relatively mild form of exercise and extensive walking that

can be involved. However, the development and manage-

ment of golf courses also results in environmental damage

of various kinds. The damage associated with golf courses

can engender intense local controversy, both for existing

facilities and when new ones are proposed for development.

The most obvious environmental affect of golf courses

is associated with the large amounts of land that they appro-

priate from other uses. Depending on its design, a typical

18-hole golf course may occupy an area of about 100-200

acres. If the previous use of the land was agricultural, then

conversion to a golf course results in a loss of food produc-

tion. Alternatively, if the land previously supported forest or

some other kind of natural

ecosystem

, then the conversion

results in a large, direct loss of

habitat

for native

species

of plants and animals.

In fact, some particular golf courses have been ex-

tremely controversial because their development caused the

destruction of the habitat of

endangered species

or rare

kinds of natural ecosystems. For instance, the Pebble Beach

Golf Links course, one of the most famous in the world,

was developed in 1919 on the Monterey Peninsula of central

California, in natural coastal and forest habitats that harbor

numerous rare and endangered species of plants and animals.

Several additional gold courses and associated tourist facili-

ties were subsequently developed nearby, all of them also

displacing natural ecosystems and destroying the habitat of

rare species

. Most of those recreational facilities were de-

veloped at a time when not much attention was paid to the

needs of endangered species. Today, however, the

conserva-

tion

of

biodiversity

is considered an important issue. It is

quite likely that if similar developments were now proposed

in such critical habitats, citizen groups would mount intense

protests and government regulators would not allow the golf

courses to be built.

The most intensively modified areas on golf courses

are the fairways, putting greens, aesthetic lawns and gardens,

and other highly managed areas. Because these kinds of

areas are intrinsic to the design of golf courses, a certain

amount of loss of natural habitat is inevitable. To some

degree, however, the net amount of habitat loss can be

decreased by attempting, to the degree possible, to retain

natural community types within the golf course. This can