Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Human ecology

florida), together with a wide variety of small herbaceous

plants.

The Hudson River is comparatively short. More than

80 American rivers are longer than it, but it plays a major

role in New York’s economy and

ecology

. Pollution threats

to the river have been caused by the

discharge

of industrial

and municipal waste, as well as pesticides washed off the

land by rain. From 1930 to 1975, one chemical company

on the river manufactured approximately 1.4 billion pounds

of

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs), and an estimated

10 million pounds a year entered the

environment

. In all,

a total of 1.3 million pounds of PCB contamination allegedly

occurred during the years prior to the ban, with the pollution

originating from plants at Ford Edward and Hudson Falls.

A ban was put in place for a time prohibiting the possession,

removal, and eating of fish from the waters of the upper

Hudson River. A proposed cleanup was designated, to pro-

ceed by means of a 40-mile

dredging

and sifting of 2.65

million cubic yards of

sediment

north of Albany, with an

anticipated yield of 75 tons of PCBs.

In February of 2001 the U.S.

Environmental Protec-

tion Agency

(EPA), having invoked the Superfund law,

required the chemical company to begin planning the

cleanup. The company was given several weeks to present

a viable plan of attack, or else face a potential $1.5 billion

fine for ignoring the directive in lieu of the cost of cleanup.

The cleanup cost, estimated at $500 million was presented

as the preferred alternative. The engineering phase of the

cleanup project was expected to take three years of planning

and was to be scheduled after the offending company filed

a response to the EPA. The company responded within the

allotted time frame in order to placate the EPA, although

the specifics of a drafted work plan remained undetermined,

and the company refused to withdraw a lawsuit filed in

November of 2000, which challenged the constitutionality

of the so-called Superfund law that authorized the EPA

to take action. The river meanwhile was ranked by one

environmental watchdog group as the fourth most endan-

gered in the United States, specifically because of the PCB

contamination. Environmental groups demanded also that

attention be paid to the issues of

urban sprawl

, noise,

and other pollution, while proposals for potentially polluting

projects were endorsed by industrialists as a means of spur-

ring the area’s economy. Among these industrial projects,

the construction of a cement plant in Catskill where there

is easy access to a limestone quarry, and the development

of a power plant along the river in Athens generated contro-

versy, stemming from the industrial asset afforded by devel-

opment along the river versus the advantages of a less fouled

environment. Additionally, the power plant, which threat-

ened to add four new smokestacks to the skyline and to

aggravate pollution, was seen as potentially detrimental to

727

tourism in that area. Also in recent decades,

chlorinated

hydrocarbons

, dieldrin, endrin, DDT, and other pollutants

have been linked to the decline in populations of the once

common Jefferson salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum),

fish hawk (Pandion haliaetus), and

bald eagle

(Haliaeetus

leucocephalus).

Concerns over the condition of the lower river spread

anew following a severe September 11 terrorist attack on

New York City in 2001. In this coastal tri-state urban area

where anti-dumping laws were put in place in the mid twen-

tieth century to protect the river from deterioration due to

pollution, new threats of pollution surfaced regarding the

potential for assorted types of leakage into the river caused

when the integrity of some land-based structures including

seawalls and underwater tunnels was compromised by the

impact of exploding commercial jetliners involved in the

attack. See also Agricultural pollution; Dams; Estuary;

Feedlot runoff; Fertilizer runoff; Industrial waste treatment;

Sewage treatment; Wastewater

[David Clarke]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Boyle, R. H. The Hudson River, A Natural and Unnatural History. New

York: Norton, 1979.

Peirce, N. R., and J. Hagstrom. The Book of America, Inside the Fifty States

Today. New York: Norton, 1983.

P

ERIODICALS

The Scientist, March 19, 2001.

Human ecology

Human

ecology

may be defined as the branch of knowledge

concerned with relationships between human beings and

their environments. Among the disciplines contributing

seminal work in this field are sociology, anthropology, geog-

raphy, economics, psychology, political science, philosophy,

and the arts. Applied human ecology emerges in engineering,

planning, architecture, landscape architecture,

conserva-

tion

, and public health. Human ecology, then, is an interdis-

ciplinary study which applies the principles and concepts of

ecology to human problems and the human condition. The

notion of interaction—between human beings and the

envi-

ronment

and between human beings—is fundamental to

human ecology, as it is to biological ecology.

Human ecology as an academic inquiry has disciplinary

roots extending back as far as the 1920s. However, much

work in the decades prior to the 1970s was narrowly drawn

and was often carried out by a few individuals whose intellec-

tual legacy remained isolated from the mainstream of their

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Humane Society of the United States

disciplines. The work done in sociology offers an exception

to the latter (but not the former) rule; sociological human

ecology is traced to the Chicago school and the intellectual

lineage of Robert Ezra Park, his student Roderick D. Mac-

kenzie, and Mackenzie’s student Amos Hawley. Through

the influence of these men and their school, human ecology,

for a time, was narrowly identified with a sociological analysis

of spatial patterns in urban settings (although broader ques-

tions were sometimes contemplated).

Comprehensive treatment of human ecology is first

found in the work of Gerald L. Young, who pioneered the

study of human ecology as an interdisciplinary field and as

a conceptual framework. Young’s definitive framework is

founded upon four central themes. The first of these is

interaction, and the other three are developed from it: levels

of organization, functionalism (part-whole relationships),

and holism. These four basic concepts form the foundation

for a series of field derivatives (

niche

, community, and

eco-

system

) and consequent notions (institutions, proxemics,

alienation, ethics, world community, and stress/capacitance).

Young’s emphasis on linkages and process set his approach

apart from other synthetic attempts in human ecology, which

were largely cumbersome classificatory schemata. These were

subject to harsh criticism because they tended to embrace

virtually all knowledge, resolve themselves into superficial

lists and mnemonic “building blocks,” and had little applica-

bility to real-world problems.

Generally, comprehensive treatment of human ecology

is more advanced in Europe than it is in the United States.

A comprehensive approach to human ecology as an interdis-

ciplinary field and conceptual framework gathered momen-

tum in several independent centers during the 1970s and

1980s. Among these have been several college and university

programs and research centers, including those at the Uni-

versity of Go

¨

teborg, Sweden, and, in the United States, at

Rutgers University and the University of California at Davis.

Interdisciplinary programs at the undergraduate level were

first offered in 1972 by the College of the Atlantic (Maine)

and The Evergreen State College (Washington). The Com-

monwealth Human Ecology Council in the United King-

dom, the International Union of Anthropological and Eth-

nological Sciences’ Commission on Human Ecology, the

Centre for Human Ecology at the University of Edinburgh,

the Institute for Human Ecology in California, and profes-

sional societies and organizations in Europe and the United

States have been other centers of development for the field.

Dr. Thomas Dietz, President of the Society for Hu-

man Ecology, defined some of the priority research problems

which human ecology addresses in recent testimony before

the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Envi-

ronment and the

National Academy of Sciences

Commit-

tee on Environmental Research. Among these, Dietz listed

728

global change, values, post-hoc evaluation, and science and

conflict in

environmental policy

. Other human ecologists

would include in the list such items as commons problems,

carrying capacity

,

sustainable development

, human

health, ecological economics, problems of resource use and

distribution, and family systems. Problems of epistemology

or cognition such as environmental perception, conscious-

ness, or paradigm change also receive attention.

Our Common Future, the report of the United Nation’s

World Commission on Environment and Development of

1987, has stimulated a new phase in the development of

human ecology. A host of new programs, plans, conferences

and agendas have been put forth, primarily to address phe-

nomena of global change and the challenge of sustainable

development. These include the Sustainable Biosphere Initia-

tive published by the

Ecological Society of America

in

1991 and extended internationally; the United Nations Con-

ference on Environment and Development; the proposed

new United States National Institutes for the Environment;

the Man and the

Biosphere

Program’s Human-Dominated

Systems Program; the report of the

National Research

Council

Committee on Human Dimensions of Global

Change and the associated National Science Foundation’s

Human Dimensions of Global Change Program; and

green

plans

published by the governments of Canada, Norway,

the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Austria. All

of these programs call for an integrated, interdisciplinary

approach to complex problems of human-environmental re-

lationships. The next challenge for human ecology will be

to digest and steer these new efforts and to identify the

perspectives and tools they supply.

[Jeremy Pratt]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Jungen, B. “Integration of Knowledge in Human Ecology.” In Human

Ecology: A Gathering of Perspectives, edited by R. J. Borden, et al., Selected

papers from the First International Conference of the Society for Human

Ecology, 1986.

———. Origins of Human Ecology. Stroudsberg, PA: Hutchinson &

Ross, 1983.

P

ERIODICALS

Young, G. L. “Human Ecology As An Interdisciplinary Concept: A Critical

Inquiry.” Advances in Ecological Research 8 (1974): 1–105.

———. “Conceptual Framework For An Interdisciplinary Human Ecol-

ogy.” Acta Oecologiae Hominis 1 (1989): 1–136.

Humane Society of the United States

The largest animal protection organization in the United

States, Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) works

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Human-powered vehicles

to preserve

wildlife

and

wilderness

, save

endangered spe-

cies

, and promote humane treatment of all animals. Formed

in 1954, HSUS specializes in education, cruelty investiga-

tions and prosecutions, wildlife and

nature

preservation,

environmental protection, federal and state legislative activi-

ties, and other actions designed to protect animal welfare

and the

environment

.

Major projects undertaken by HSUS in recent years

have included campaigns to stop the killing of

whales

,

dolphins

,

elephants

, bears, and

wolves

; to help reduce

the number of animals used in medical research and to

improve the conditions under which they are used; to oppose

the use of fur by the fashion industry; and to address the

problem of pet overpopulation.

The group has worked extensively to ban the use of

tuna caught in a way that kills dolphins, largely eliminating

the sale of such products in the United States and western

Europe. It has tried to stop international airlines from trans-

porting exotic birds into the United States. Other high prior-

ity projects have included banning the international trade in

elephant ivory, especially imports into the United States,

and securing and maintaining a general worldwide morato-

rium on commercial

whaling

.

HSUS companion animals section works on a variety

of issues affecting dogs, cats, birds, horses, and other animals

commonly kept as pets, striving to promote responsible pet

ownership, particularly the spaying and neutering of dogs

and cats to reduce the tremendous overpopulation of these

animals. HSUS works closely with local shelters and humane

societies across the country, providing information, training,

evaluation, and consultation.

Several national and international environmental and

animal protection groups are affiliated and work closely with

HSUS. Humane Society International works abroad to fulfill

HSUS’s mission and to institute reform and educational

programs that will benefit animals. EarthKind, a global envi-

ronmental protection group that emphasizes wildlife protec-

tion and humane treatment of animals, has been active in

Russia, India, Thailand, Sri Lanka, the United Kingdom,

Romania, and elsewhere, working to preserve forests,

wet-

lands

, wild rivers, natural ecosystems, and endangered

wildlife.

The National Association for Humane and

Environ-

mental Education

is the youth education division of HSUS,

developing and producing periodicals and teaching materials

designed to instill humane values in students and young

people, including KIND (Kids in Nature’s Defense) News,a

newspaper for elementary school children, and KIND

TEACHER, an 80-page annual full of worksheets and activi-

ties for use by teachers.

The Center for Respect of Life and the Environment

works with academic institutions, scholars, religious leaders

729

and organizations, arts groups, and others to foster an ethic

of respect and compassion towards all creatures and the

natural environment. Its quarterly publication, Earth Ethics,

examines such issues as earth education, sustainable commu-

nities, ecological economics, and other values affecting our

relationship with the natural world. The Interfaith Council

for the Protection of Animals and Nature promotes

conser-

vation

and education mainly within the religious commu-

nity, attempting to make religious leaders, groups, and indi-

viduals more aware of our moral and spiritual obligations to

preserve the planet and its myriad life forms.

HSUS has been quite active, hard-hitting, and effec-

tive in promoting its animal protection programs, such as

leading the fight against the fur industry. It accomplishes

its goals through education, lobbying, grassroots organizing,

and other traditional, legal means of influencing public opin-

ion and government policies.

With over 3.5 million members or “constituents” and

an annual budget of over $35 million, HSUS is considered

the largest and one of the most influential animal protection

groups in the United States and, perhaps, the world.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

The Humane Society of the United States, 2100 L Street, NW,

Washington, D.C. USA 20037 (202) 452-1100, <http://www.hsus.org>

Humanism

A perspective or doctrine that focuses primarily on the inter-

ests, capacities, and achievements of human beings. This

focus on human concerns has led some to conclude that

human beings have rightful dominion over the earth and

that their interests and well-being are paramount and take

precedence over all other considerations. Religious humanism,

for instance, generally holds that God made human beings

in His own image and put them in charge of His creation.

Secular humanism views human beings as the source of all

value or worth. Some environmentally-minded critics, such

as Lynn White Jr., and David Ehrenfeld claim that much

environmental destruction can be traced to “the arrogance

of humanism.”

Human-powered vehicles

Finding easy modes of

transportation

seems to be a basic

human need, but finding easy and clean modes is becoming

imperative. Traffic congestion, overconsumption of

fossil

fuels

and

air pollution

are all direct results of automotive

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Human-powered vehicles

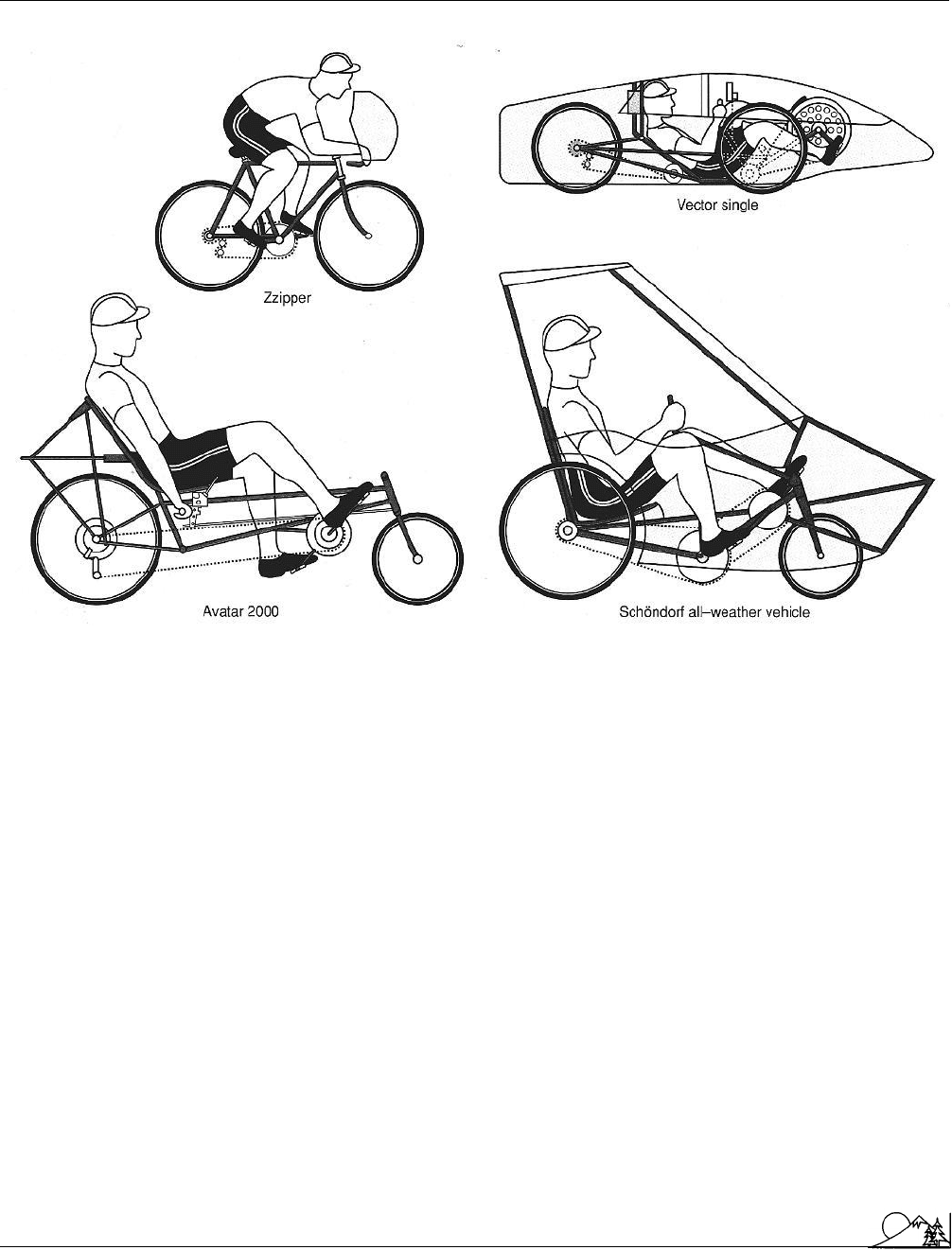

Innovative bicycle designs. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

lifestyles around the world. The logical alternative is human-

powered vehicles (HPVs), perhaps best exemplified in the

bicycle, the most basic HPV. New high-tech developments

in HPVs are not yet ready for mass production, nor are they

able to compete with cars. Pedal-propelled HPVs in the air,

on land, or under the sea are still in the expensive, design-

and-race-for-a-prize category. But the challenge of human-

powered transport has inspired a lot of inventive thinking,

both amateur and professional.

Bicycles and rickshaws comprise the most basic HPVs.

Of these two vehicles, bicycles are clearly the most popular,

and production of these HPVs has surpassed production of

automobiles in recent years. The number of bicycles in use

throughout the world is roughly double that of cars; China

alone contains 270 million bicycles, or one third of the total

bicycles worldwide. Indeed the bicycle has overtaken the

automobile

as the preferred mode of transportation in many

nations. There are many reasons for the popularity of the

bike: it fulfills both recreational and functional needs, it is

an economical alternative to automobiles, and it does not

contribute to the problems facing the

environment

.

730

Although the bicycle provides a healthy and scenic

form of

recreation

, people also find it useful in basic

transportation. In the Netherlands, bicycle transportation

accounts for 30% of work trips and 60% of school trips.

One-third of commuting to work in Denmark is by bicycle.

In China, the vast majority of all trips there are made

via bicycle.

A surge in bicycle production occurred in 1973, when

in conjunction with rising oil costs, production doubled to

52 million per year. Soaring fuel prices in the 1970s inspired

people to find inexpensive, economical alternatives to cars,

and many turned to bicycles. Besides being efficient trans-

portation, bikes are simply cheaper to purchase and to main-

tain than cars. There is no need to pay for parking or tolls,

no expensive upkeep, and no high fuel costs.

The lack of fuel costs associated with bicycles leads to

another benefit: bicycles do not harm the environment. Cars

consume fossil fuels and in so doing release more than two-

thirds of the United States’ smog-producing

chemicals

.

They are furthermore considered responsible for many other

environmental ailments: depletion of the

ozone

layer

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Human-powered vehicles

through release of

chlorofluorocarbons

from automobile

air conditioning units; cause of

cancer

through toxic emis-

sions; and consumption of the world’s limited fuel resources.

With human energy as their only requirement, bicycles have

none of these liabilities.

Nevertheless, in many cases—such as long trips or

travelling in inclement weather—cars are the preferred form

of transportation. Bicycles are not the optimal choice in many

situations. Thus engineers and designers seek to improve on

the bicycle and make machines suitable for transport under

many different conditions. They are striving to produce new

human-powered vehicles—HPVs that maximize air and sea

currents, that have reasonable interior ergonomics, and that

can be inexpensively produced. Several machines designed

to fit this criteria exist.

As for developments in human-powered aircraft, suc-

cess is judged on distance and speed, which depend on the

strength of the pedaller and the lightness of the craft. The

current world record holder is Greek Olympic cyclist Ka-

nellos Kanellopoulos who flew Daedalus 88. Daedalus 88 was

created by engineer John Langford and a team of MIT

engineers and funded by American corporations. Kanello-

poulos flew Daedalus 88 for 3 hours and 54 minutes across

the Aegean Sea between Crete and Santorini, a distance of

74 mi (119 km), in April 1988. The craft averaged 18.5

mph (29 kph) and flew 15 ft (4.6 m) above the water. Upon

arrival at Santorini, however, the sun began to heat up the

black sands and generate erratic shore winds and Daedalus

88 plunged into the sea. It was a few yards short of its goal,

and the tailboom of the 70-lb (32-kg) vehicle was snapped

by the wind. But to cheering crowds on the beach, Kanello-

poulos rose from the sea with a victory sign and strode to

shore.

In the creation of a human-powered helicopter, stu-

dents at California Polytechnic State University had been

working on perfecting one since 1981. In 1989 they achieved

liftoff with Greg McNeil, a member of the United States

National Cycling Team, pedalling an astounding 1.0 hp.

The graphite epoxy, wood, and Mylar craft, Da Vinci III,

rose 7 in (17.7 cm) for 6.8 seconds. But rules for the $10,000

Sikorsky prize, sponsored by the American Helicopter Soci-

ety, stipulate that the winning craft must rise nearly 10 ft,

or 3 m, and stay aloft one minute.

On land, recumbent vehicles, or recumbents, are

wheeled vehicles in which the driver pedals in a semi-recum-

bent position, contained within a windowed enclosure. The

world record was set in 1989 by American Fred Markham

at the Michigan International Speedway in an HPV named

Goldrush. Markham pedalled more than 44 mph (72 kph).

Unfortunately, the realities of road travel cast a long

shadow over recumbent HPVs. Crews discovered that they

tended to be unstable in crosswinds, distracted other drivers

731

and pedestrians, and lacked the speed to correct course safely

in the face of oncoming cars and trucks.

In the sea, being able to maneuver at your own pace

and be in control of your vehicle—as well as being able to

beat a fast retreat undersea—are the problems faced by HPV

submersible engineers. Human-powered subs are not a new

idea. The Revolutionary War created a need for a bubble

sub that was to plant an explosive in the belly of a British

ship in New York Harbor. (The naval officer, breathing

one-half hour’s worth of air, failed in his night mission, but

survived).

The special design problems of modern two-person

HP-subs involve controlling buoyancy and ballast, pitch and

yaw (nose up/down/sideways), reducing drag, increasing

thrust, and positioning the pedaller and the propulsor in the

flooded cockpit (called “wet") in ways that maximize air

intake from scuba tanks and muscle power from arms and

legs.

Depending on the design, the humans in HP-subs lie

prone, foot to head or side by side, or sit, using their feet

to pedal and their hands to control the rudder through

the underwater currents. Studies by the United States Navy

Experimental Dive Unit indicate that a well-trained athlete

can sustain 0.5 hp for 10 minutes underwater.

On the surface of the water, fin-propelled watercraft—

lightweight inflatables that are powered by humans kicking

with fins—are ideal for fishermen whom maneuverability,

not speed, is the goal. Paddling with the legs, which does

not disturb fish, leaves the hands free to cast. In most designs,

the fisherman sits on a platform between tubes, his feet in

the water. Controllability is another matter, however: in

open windy water, the craft is at the mercy of the elements

in its current design state. Top speed is about 50 yd (46 m)

in three minutes.

Finally, over the surface of the water, the first human-

powered hydrofoil, Flying Fish, with national track sprinter

Bobby Livingston, broke a world record in September 1989

when it traveled 100 m over Lake Adrian, Michigan, at 16.1

knots (18.5 mph). A vehicle that pedalled like a bicycle,

resembled a model airplane with a two-blade propeller and

a 6-ft (1.8-m)

carbon

graphite wing, Flying Fish sped across

the surface of the lake on two pontoons.

[Stephanie Ocko and Andrea Gacki]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lowe, M. “Bicycle Production Outpaces Autos.” In Vital Signs 1992: The

Trends That Are Shaping Our Future, edited by L. R. Brown, C, Flavin,

and H. Hane. New York: Norton, 1992.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Humus

P

ERIODICALS

Banks, R. “Sub Story.” National Geographic World (July 1992): 8–11.

Blumenthal, T. “Outer Limits.” Bicycling, December 1989, 36.

Britton, P. “Muscle Subs.” Popular Science, June 1989, 126–129.

———. “Technology Race Beneath the Waves.” Popular Science, June 1991,

48–54.

Horgan, J. “Heli-Hopper: Human-powered Helicopter Gets Off the

Ground.” Scientific American 262 (March 1990): 34.

Kyle, C. R. “Limits of Leg Power.” Bicycling, October 1990, 100–101.

Langley, J. “Those Flying Men and Their Magnificent Machines.” Bicycling,

April 1992, 74–76.

“Man-Powered Helicopter Makes First Flight.” Aviation Week and Space

Technology, December 1989, 115.

Martin, S. “Cycle City 2000.” Bicycling, March 1992, 130–131.

Humus

Humus is essentially decomposed organic matter in

soil

.

Humus can vary in color but is often dark brown. Besides

containing valuable nutrients, there are many other benefits

of humus: it stabilizes soil mineral particles into aggregates,

improves pore space relationships and aids in air and water

movement, aids in water holding capacity, and influences

the

absorption

of

hydrogen

ions as a

pH

regulator.

Hunting and trapping

Wild animals are a potentially renewable natural resource.

This means that they can be harvested in a sustainable fash-

ion, as long as then birth rate is greater than the rate of

exploitation by humans. In the sense meant here, “harvest-

ing” refers to the killing of wild animals as a source of meat,

fur, antlers, or other useful products, or as an outdoor sport.

The harvesting can involve trapping, or hunting using guns,

bows-and-arrows, or other weapons. (Fishing is also a kind

of hunting, but it is not dealt with here). From the ecological

perspective, it is critical that the exploitation is undertaken

in a sustainable fashion; otherwise, serious damages are

caused to the resource and to ecosystems more generally.

Unfortunately, there have been numerous examples in

which wild animals have been harvested at grossly unsustain-

able rates, which caused their populations to decline severely.

In a few cases this caused

species

to become extinct—they

no longer occur anywhere on Earth. For example, commer-

cial hunting in North America resulted in the extinctions

of the great auk (Pinguinnis impennis),

passenger pigeon

(Ectopistes migratorius), and Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis

stelleri). Unsustainable commercial hunting also brought

other species to the brink of

extinction

, including the Es-

kimo curlew (Numenius borealis), northern right whale (Eu-

balaena glacialis), northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus), grey

732

whale (Eschrichtius robustus), and American

bison

or buffalo

(Bison bison).

Fortunately, these and many other examples of over-

exploitation of wild animals by humans are regrettable cases

from the past. Today, the exploitation of wild animals in

North America is undertaken with a view to the longer-

term

conservation

of their stocks, that is, an attempt is

made to manage the harvesting in a sustainable fashion. This

means that trapping and hunting are much more closely

regulated than they used to be.

If harvests of wild animals are to be undertaken in

a sustainable manner, it is critical that harvest levels are

determined using the best available understanding of popula-

tion-level productivity and stock sizes. It is also essential

that harvest quotas are respected by trappers and hunters and

that illegal exploitation (or

poaching

) does not compromise

what might otherwise be a sustainable activity. The challenge

of modern

wildlife management

is to ensure that good

conservation science is sensibly integrated with effective

monitoring and management of the rates of exploitation.

Ethics of trapping and hunting

From the strictly ecological perspective, sustainable

trapping and hunting of wild animals is no more objection-

able than the prudent harvesting of timber or agricultural

crops. However, people have widely divergent attitudes about

the killing of wild (or domestic) animals for meat, sport, or

profit. At one end of the ethical spectrum are people who

see no problem with the killing wild animals as a source of

meat or cash. At the other extreme are individuals with a

profound respect for the rights of all animals, and who

believe that killing any sentient creature is ethically wrong.

Many of these latter people are animal-rights activists, and

some of them are involved in organizations that undertake

high-profile protests and other forms of advocacy to prevent

or restrict trapping and hunting. In essence, these people

object to the lethal exploitation of wild animals, even under

closely regulated conditions that would not deplete their

populations. Most people, of course, have attitudes that are

intermediate to those just described.

Trapping

The fur trade was one a very important commercial

activity during the initial phase of the colonization of North

America by Europeans. During those times, as now, furs

were a valuable commodity that could be obtained from

nature

and could be sold at a great profit in urban markets.

In fact, the quest for furs was the most important reason

for much of the early exploration of the interior of North

America, as fur traders penetrated all of the continent’s great

rivers seeking new sources of pelts and profit. Most fur-

bearing animals are harvested by a form of hunting known

as trapping.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hunting and trapping

Until recently, most trapping involved leg-hold traps,

a relatively crude method that results in many animals endur-

ing cruel and lingering deaths. Fortunately, other, more

humane alternatives now exist in which most trapped animals

are killed quickly and do not suffer unnecessarily. In large

part, the movement towards more merciful trapping methods

has occurred in response to effective, high-profile lobbying

by organizations that oppose trapping, and the trapping

industry has responded by developing and using more hu-

mane methods of killing wild furbearers.

Various species of furbearers are trapped in North

America, particularly in relatively remote, wild areas, such as

the northern and montane forests of the continental United

States, Alaska, and Canada. Among the most valuable fur-

bearing species are beaver (Castor canadensis), muskrat (On-

datra zibethicus), mink (Mustela vison), river otter (Enhydra

lutris), bobcat (Lynx rufus), lynx (Lynx canadensis), red fox

(Vulpes vulpes), wolf (Canis lupus), and

coyote

(Canis la-

trans). The hides of other species are also valuable, such as

black bear (Ursus americanus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus

virginianus), and moose (Alces alces), but these species are

not hunted primarily for their pelage.

Some species of

seals

are hunted for their fur, al-

though this is largely done by shooting, clubbing, or netting,

rather than by trapping. The best examples of this are the

harp seal (Phoca groenlandica) of the northwestern Atlantic

Ocean and the northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) of the

Bering Sea. Many seal pups are killed by commercial hunters

in the spring when their coats are still white and soft. This

harvest has been highly controversial and is the subject of

intense opposition from

animal rights

groups.

Game Mammals

Hunting is a popular sport in North America, enjoyed

by about 16 million people each year, most of them men.

In 1991, hunting contributed more than $12 billion to the

United States economy, about half of which was spent by

big-game hunters.

Various species of terrestrial animals are hunted in

large numbers. This is mostly done by stalking the animals

and shooting them with rifles, although shotguns and bow-

and-arrow are sometimes used. Some hunting is done for

subsistence purposes, that is, the meat of the animals is used

to feed the family or friends of the hunters. Subsistence

hunting is especially important in remote areas and for ab-

original hunters. Commercial or market hunts also used to

be common, but these are no longer legal in North America

(except under exceptional circumstances) because they have

generally proven to be unsustainable. However, illegal, semi-

commercial hunting (or poaching) still takes place in many

remote areas where game animals are relatively abundant

and where there are local markets for wild meat.

733

In addition, many people hunt as a sport, that is, for

the excitement and accomplishment of tracking and killing

wild animals. In such cases, using the meat of the hunted

animals may be only a secondary consideration, and in fact

the hunter may only seek to retain the head, antlers, or horns

of the prey as a trophy (although the meat may be kept by

the hunter’s guide). Big-game hunting is an economically

important activity in North America, with large amounts of

money being spent on the equipment, guides, and

transpor-

tation

necessary to undertake this sport.

The most commonly hunted big-game mammal in

North America is the white-tailed deer. Other frequently

hunted ungulates include the mule deer (Odocoileus hemio-

nus), moose, elk or wapiti (Cervus canadensis), caribou (Ran-

gifer tarandus), and pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra ameri-

cana). Black bear and

grizzly bear

(Ursus arctos) are also

hunted, as are bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) and mountain

goat (Oreamnos americanus). Commonly hunted small-game

species include various species of rabbits and hares, such as

the cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus), snowshoe hare

(Lepus americanus), and jackrabbit (Lepus californicus), as well

as the grey or black squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and wood-

chuck (Marmota monax). Wild boar (Sus scrofa) are also

hunted in some regions—these are feral animals descended

from escaped domestic pigs.

Game birds

Various larger species of birds are hunted in North

America for their meat and for sport. So-called upland game

birds are hunted in terrestrial habitats and include ruffed

grouse (Bonasa umbellus), willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lago-

pus), bobwhite quail (Colinus virginianus), wild turkey (Mel-

eagris gallopava), mourning dove (Zanaidura macroura), and

woodcock (Philohela minor). Several

introduced species

of

upland gamebirds are also commonly hunted, particularly

ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) and Hungarian

or grey partridge (Perdix perdix).

Much larger numbers of waterfowl are hunted in

North America, including millions of ducks and geese. The

most commonly harvested species of waterfowl are mallard

(Anas platyrhynchos), wood duck (Aix sponsa), Canada goose

(Branta canadensis), and snow and blue goose (Chen hyper-

borea), but another 35 or so species in the duck family are

also hunted. Other hunted waterfowl include coots (Fulica

americana) and moorhens (Gallinula chloropus).

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Halls, L. K., ed. White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management. Harrisburg:

Stackpole Books, 1984.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hurricane

Novak, M., et al. Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North

America. North Bay: Ontario Trappers Association, 1987.

Phillips, P. C. The Fur Trade (2 vols.). Norman: University of Okla-

homa, 1961.

Robinson, W. L., and E. G. Bolen. Wildlife Ecology and Management. 3rd

ed. New York: Macmillan, 1996.

P

ERIODICALS

Freedman, B. Environmental Ecology. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic

Press, 1995.

Hurricane

Hurricanes, called typhoons or tropical cyclones in the Far

East, are intense cyclonic storms which form over warm

tropical waters, and generally remain active and strong only

while over the oceans. Their intensity is marked by a distinct

spiraling pattern of clouds, very low atmospheric pressure

at the center, and extremely strong winds blowing at speeds

greater than 74 mph (120 kph) within the inner rings of

clouds. Typically when hurricanes strike land and move in-

land, they immediately start to disintegrate, though before

they do they bring widespread destruction of property and

loss of life. The radius of such a storm can be 100 mi (160

km) or greater. Thunderstorms, hail, and tornados frequently

are imbedded in hurricanes.

Hurricanes occur in every tropical ocean except the

South Atlantic, and with greater frequency from August

through October than any other time of year. The center

of a hurricane is called the eye. It is an area of relative

calm, few clouds and higher temperatures, and represents

the center of the low pressure pattern. Hurricanes usually

move from east to west near the tropics, but when they

migrate poleward to the mid-latitudes they can get caught

up in the general west to east flow pattern found in that

region of the earth. See also Tornado and cyclone

George Evelyn Hutchinson (1903 –

1991)

American ecologist

Born January 30, 1903, in Cambridge, England, Hutchinson

was the son of Arthur Hutchinson, a professor of mineralogy

at Cambridge University, and Evaline Demeny Shipley

Hutchinson, an ardent feminist. He demonstrated an early

interest in

flora

and

fauna

and a basic understanding of

the scientific method. In 1918, at the age of 15, he wrote

a letter to the Entomological Record and Journal of Variation

about a grasshopper he had seen swimming in a pond. He

described an experiment he performed on the insect and

included it for taxonomic identification.

734

In 1924, Hutchinson earned his bachelor’s degree in

zoology from Emmanuel College at Cambridge University,

where he was a founding member of the Biological Tea

Club. He then served as an international education fellow

at the Stazione Zoologica in Naples from 1925 until 1926,

when he was hired as a senior lecturer at the University

of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. He was

apparently fired from this position two years later by admin-

istrators who never imagined that in 1977 the university

would honor the ecologist by establishing a research labora-

tory in his name.

Hutchinson earned his master’s degree from Emman-

uel College in absentia in 1928 and applied to Yale University

for a fellowship so he could pursue a doctoral degree. He

was instead appointed to the faculty as a zoology instructor.

He was promoted to assistant professor in 1931 and became

an associate professor in 1941, the year he obtained his

United States citizenship. He was made a full professor of

zoology in 1945, and between 1947 and 1965 he served as

director of graduate studies in zoology. Hutchinson never did

receive his doctoral degree, though he amassed an impressive

collection of honorary degrees during his lifetime.

Hutchinson was best known for his interest in

limnol-

ogy

, the science of freshwater lakes and ponds. He spent

most of his life writing the four-volume Treatise on Limnol-

ogy, which he completed just months before his death. The

research that led to the first volume—covering geography,

physics, and chemistry—earned him a Guggenheim Fellow-

ship in 1957. The second volume, published in 1967, covered

biology and

plankton

. The third volume, on water plants,

was published in 1975, and the fourth volume, about inverte-

brates, appeared posthumously in 1993.

The Treatise on Limnology was among the nine books,

nearly 150 research papers, and many opinion columns which

Hutchinson penned. He was an influential writer whose

scientific papers inspired many students to specialize in

ecol-

ogy

. Hutchinson’s greatest contribution to the science of

ecology was his broad approach, which became known as

the “Hutchinson school.” His work encompassed disciplines

as varied as biochemistry, geology, zoology, and botany. He

pioneered the concept of

biogeochemistry

, which examines

the exchange of

chemicals

between organisms and the

envi-

ronment

. His studies in biogeochemistry focused on how

phosphates

and

nitrates

move from the earth to plants,

then animals, and then back to the earth in a continuous

cycle. His

holistic approach

influenced later environmen-

talists when they began to consider the global scope of envi-

ronmental problems.

In 1957, Hutchinson published an article entitled

“Concluding Remarks,” considered his most inspiring and

intriguing work, as part of the Cold Spring Harbor Symposia

on Quantitative Biology. Here, he introduced and described

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

George Evelyn Hutchinson

the ecological

niche

, a concept which has been the source

of much research and debate ever since. The article was one

of only three in the field of ecology chosen for the 1991

collection Classics in Theoretical Biology.

Hutchinson won numerous major awards for his work

in ecology. In 1950, he was elected to the National Academy

of Science. Five years later, he earned the Leidy Medal

from the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. He

was awarded the Naumann Medal from the International

Association of Theoretical and Applied Limnology in 1959.

This is a global award, granted only once every three years,

which Hutchinson earned for his contributions to the study

of lakes in the first volume of his treatise. In 1962, the

Ecological Society of America

chose him for its Eminent

Ecologist Award.

Hutchinson’s research often took him out of the coun-

try. In 1932, he joined a Yale expedition to Tibet, where

he amassed a vast collection of organisms from high-altitude

lakes. He wrote many scientific articles about his work in

North India, and the trip also inspired his 1936 travel book,

The Clear Mirror. Other research projects drew Hutchinson

to Italy, where, in the

sediment

of Lago di Monterosi, a

lake north of Rome, he found evidence of the first case of

artificial eutrophication, dating from around 180

B.C.

Hutchinson was devoted to the arts and humanities,

and he counted several musicians, artists, and writers among

his friends. The most prominent of his artistic friends was

English author Rebecca West. He served as her literary

executor, compiling a bibliography of her work which was

published in 1957. He was also the curator of a collection of

her papers at Yale’s Beinecke Library. Hutchinson’s writing

reflected his diverse interests. Along with his scientific works

and his travel book, he also wrote an autobiography and

three books of essays, The Itinerant Ivory Tower (1953),

The Enchanted Voyage and Other Studies (1962), and The

Ecological Theatre and the Evolutionary Play (1965). For 12

years, beginning in 1943, Hutchinson wrote a regular column

titled “Marginalia” for the American Scientist. His thoughtful

columns examined the impact on society of scientific issues

of the day.

Hutchinson’s skill at writing, as well as his literary

interests, was recognized by Yale’s literary society, the Eliza-

bethan Club, which twice elected him president. He was

also a member of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and

Sciences and served as its president in 1946.

While Hutchinson built his reputation on his research

and writing, he also was considered an excellent teacher.

His teaching career began with a wide range of courses

including beginning biology, entomology, and vertebrate

embryology. He later added limnology and other graduate

courses to his areas of expertise. He was personable as well

as innovative, giving his students illustrated note sheets, for

735

example, so they could concentrate on his lectures without

worrying about taking their own notes. Leading oceanogra-

pher Linsley Pond was among the students whose careers

were changed by Hutchinson’s teaching. Pond enrolled in

Yale’s doctoral program with the intention of becoming an

experimental embryologist. But after one week in Hutchin-

son’s limnology class, he had decided to do his dissertation

research on a pond.

Hutchinson loved Yale. He particularly cherished his

fellowship in the residential Saybrook College. He was also

very active in several professional associations, including the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American

Philosophical Society, and the

National Academy of Sci-

ences

. He served as president of the American Society of

Limnology and Oceanography in 1947, the American Soci-

ety of Naturalists in 1958, and the International Association

for Theoretical and Applied Limnology from 1962 until

1968.

Hutchinson retired from Yale as professor emeritus in

1971, but continued his writing and research for 20 more

years, until just months before his death. He produced several

books during this time, including the third volume of his

treatise, as well as a textbook titled An Introduction to Popula-

tion Ecology (1978), and memoirs of his early years, The

Kindly Fruits of the Earth (1979).

He also occasionally returned to his musings on science

and society, writing about several topical issues in 1983 for

the American Scientist. Here, he examined the question of

nuclear disarmament, speculating that “it may well be that

total nuclear disarmament would remove a significant deter-

rent to all war.” In the same article, he also philosophized

on differences in behavior between the sexes: “On the whole,

it would seem that, in our present state of

evolution

, the

less aggressive, more feminine traits are likely to be of greater

value to us, though always endangered by more aggressive,

less useful tendencies. Any such sexual difference, small as

it may be, is something on which perhaps we can build.”

Several of Hutchinson’s most prestigious honors, in-

cluding the Tyler Award, came during his retirement.

Hutchinson earned the $50,000 award, often called the No-

bel Prize for

conservation

, in 1974. That same year, the

National Academy of Sciences gave him the Frederick Gar-

ner Cottrell Award for Environmental Quality. He was

awarded the Franklin Medal from the Franklin Institute in

1979, the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National

Academy of Sciences in 1984, and the Kyoto Prize in Basic

Science from Japan in 1986. Having once rejected a National

Medal of Science because it would have been bestowed on

him by President Richard Nixon, he was awarded the medal

posthumously by President George Bush in 1991.

Hutchinson’s first marriage, to Grace Evelyn Pickford,

ended with a divorce in 1933. During the six weeks residence

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Hybrid vehicles

the state of Nevada then required to grant divorces, he

studied the lakes near Reno and wrote a major paper on

freshwater ecology in

arid

climates. Later that year, Hutch-

inson married Margaret Seal, who died in 1983 from Alzhei-

mer’s disease. Hutchinson cared for her at home during her

illness. In 1985, he married Anne Twitty Goldsby, whose

care enabled him to travel extensively and continue working

in spite of his failing health. When she died unexpectedly

in December 1990, the ailing widower returned to his British

homeland. He died in London on May 17, 1991, and was

buried in Cambridge.

[Cynthia Washam]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Hutchinson, George A. A Preliminary List of the Writings of Rebecca West.

Yale University Library, 1957.

———. A Treatise on Limnology. Wiley, Vol. 1, 1957; Vol. 2, 1967; Vol.

3, 1979; Vol. 4, 1993.

———. An Introduction to Population Ecology. Yale University Press, 1978.

———. The Clear Mirror. Cambridge University Press, 1937.

———. The Ecological Theater and the Evolutionary Play. Yale University

Press, 1965.

———. The Enchanted Voyage and Other Studies. Yale University Press,

1962.

———. The Itinerant Ivory Tower. Yale University Press, 1952.

———. The Kindly Fruits of the Earth. Yale University Press, 1979.

P

ERIODICALS

———. “Marginalia.” American Scientist (November–December 1983):

639–644.

Edmondson, Y. H., ed. “G. Evelyn Hutchinson Celebratory Issue.” Limnol-

ogy and Oceanography 16 (1971): 167–477.

Edmondson, W. T. “Resolution of Respect.” Bulletin of the Ecological Society

of America 72 (1991): 212–216.

Hutchinson, George E. “A Swimming Grasshopper.” Entomological Record

and Journal of Variation 30 (1918): 138.

———. “Marginalia.” American Scientist 31 (1943): 270.

———. “Concluding Remarks.” Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 53 (1991):

193–213.

———. “Lanula: An Account of the History and Development of the

Lago di Monterosi, Latlum, Italy.” Transactions of the American Philosophical

Society 64 (1970): part 4.

Hybrid vehicles

The roughly 200 million automobiles and light trucks cur-

rently in use in the United States travel approximately 2.4

trillion miles every year, and consume almost two-thirds of

the U.S. oil supply. They also produce about two-thirds of

the

carbon monoxide

, one-third of the

lead

and

nitrogen

oxides

, and a quarter of all volatile organic compounds

(VOCs). More efficient

transportation

energy use could

have dramatic effects on environmental quality as well as

736

saving billions of dollars every year in our payments to foreign

governments. In response to high

gasoline

prices in the

1970s and early 1980s,

automobile

gas-mileage averages in

the United States more than doubled from 13 mpg in 1975

to 28.8 mpg in 1988.

Unfortunately, cheap fuel prices and the popularity of

sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and light trucks in the 1990s

caused fuel efficiency to slide back below where it was 25

years earlier. By 2002, the average mileage for U.S. cars and

trucks was only 27.6 mpg. Amory B. Lovins of the

Rocky

Mountain Institute

in Colorado estimated that raising the

average fuel efficiency of the United States car and light

truck fleet by one mile per gallon would cut oil consumption

about 295,000 barrels per day. In one year, this would equal

the total amount the Interior Department hopes to extract

from the

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

(ANWR) in

Alaska.

It isn’t inevitable that we consume and pollute so

much. A number of alternative transportation options al-

ready are available. Of course the lowest possible fossil fuel

consumption option is to walk, skate, ride a bicycle, or other

forms of human-powered movement. Many people, how-

ever, want or need the comfort and speed of a motor vehicle.

Several models of battery-powered electric automobiles have

been built, but the batteries are heavy, expensive, and require

more frequent recharging than most customers will accept.

Even though 90% of all daily commutes are less than 50 mi

(80 km), most people want the capability to take a long road

trip of several hundred miles without needing to stop for

fuel or recharging.

An alternative that appears to have much more cus-

tomer appeal is the hybrid gas-electric vehicle. The first

hybrid to be marketed in the United States was the two-

seat Honda Insight. A 3-cylinder, 1.0 liter gas engine is the

main power source for this sleek, lightweight vehicle. A 7-

hp (horsepower) electric motor helps during acceleration and

hill climbing. When the small battery pack begins to run

down, it is recharged by the gas engine, so that the vehicle

never needs to be plugged in. More electricity is captured

during “regenerative” braking further increasing efficiency.

With a streamlined lightweight plastic and

aluminum

body,

the Insight gets about 75 mpg (33.7 km/l) in highway driving

and has low-enough emissions to qualify as a “super low

emission

vehicle.” It meets the most strict

air quality

stan-

dards anywhere in the United States. Quick acceleration and

nimble handling make the Insight fun to drive. Current cost

is about $20,000.

Perhaps the biggest drawback to the Insight is its

limited passenger and cargo capacity. Although the vast

majority of all motor vehicle trips made in the United States

involve only a single driver, most people want the ability to

have more than one passenger or several suitcases at least