Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Incineration

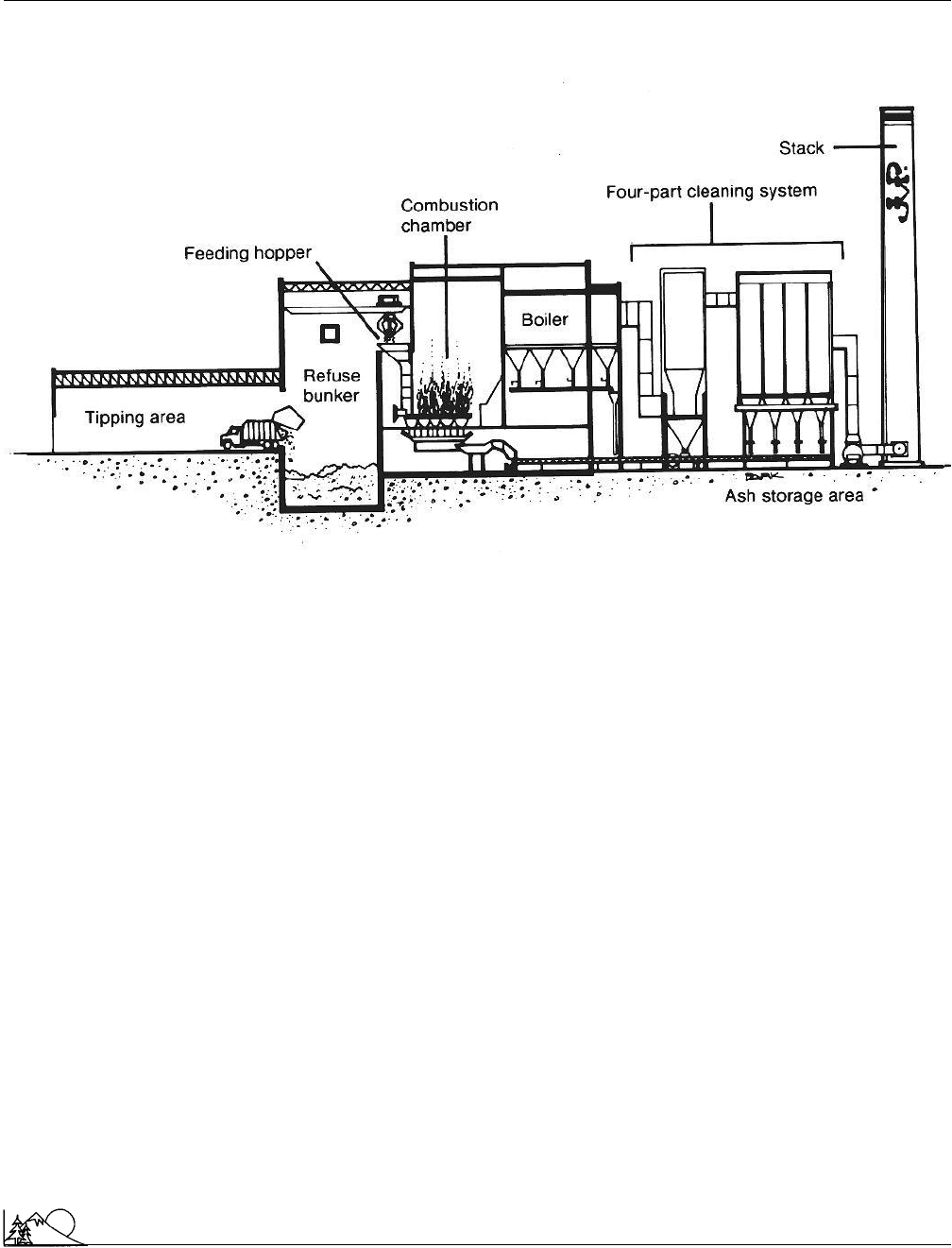

Diagram of a municipal incinerator. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

systems which neutralizes the

acid

gases (

sulfur dioxide

and hydrochloric acid, the latter resulting from burning chlo-

rinated plastic products), followed by gas

scrubbers

and

then solid/gas separation systems such as baghouses before

dischargement to

tall stacks

. The stack system contains a

variety of sensing and control devices to enable the furnace

to operate at maximum efficiency consistent with minimal

particulate

emissions. A continuous log of monitoring sys-

tems is also required for compliance with county and state

environmental quality regulations.

There are several products from a municipal incinerator

system: items which are removed before combustion such as

large metal pieces; grate or bottom ash (which is usually water-

sprayed after removal from the furnace for safe storage); fly

(or top ash) which is removed from the flue system generally

mixed with products from the acid neutralization process; and

finally the flue gases which are expelled to the

environment

.

If the system is operating optimally, the flue gases will meet

emission

requirements, and the

heavy metals

from the

wastes will be concentrated in the

fly ash

. (Typically these

heavy metals, which originate from volatile metallic constit-

uents, are

lead

and arsenic.) The fly ash typically is then stored

747

in a suitable landfill to avoid future problems of

leaching

of

heavy metals. Some municipal systems blend the bottom ash

with the top ash in the plant in order to reduce the level of

heavy metals by dilution. This practice is undesirable from an

ultimate environmental viewpoint.

There are many advantages and disadvantages to mu-

nicipal waste incineration. Some of the advantages are as

follows: 1) The waste volume is reduced to a small fraction

of the original. 2) Reduction is rapid and does not require

semi-infinite residence times in a landfill. 3) For a large

metropolitan area, waste can be incinerated on site, minimiz-

ing

transportation

costs. 4) The ash residue is generally

sterile, although it may require special disposal methods. 5)

By use of gas clean-up equipment, discharges of flue gases

to the environment can meet stringent requirements and be

readily monitored. 6) Incinerators are much more compact

than landfills and can have minimal odor and vermin prob-

lems if properly designed. 7) Some of the costs of operation

can be reduced by heat-recovery techniques such as the sale

of steam to municipalities or electrical energy generation.

There are disadvantages to municipal waste incinera-

tion as well. For example: 1) Generally the capital cost is

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indicator organism

high and is escalating as

emission standards

change. 2)

Permitting requirements are becoming increasingly more

difficult to obtain. 3) Supplemental fuel may be required

to burn municipal wastes, especially if

yard waste

is not

removed prior to collection. 4) Certain items such as mer-

cury-containing batteries can produce emissions of

mercury

which the gas cleanup system may not be designed to remove.

5) Continuous skilled operation and close maintenance of

process control is required, especially since stack monitoring

equipment reports any failure of the equipment which could

result in mandated shut down. 6) Certain materials are not

burnable and must be removed at the source. 7) Traffic to

and from the incinerator can be a problem unless timing

and routing are carefully managed. 8) The incinerator, like

a landfill, also has a limited life, although its lifetime can

be increased by capital expenditures. 9) Incinerators also

require landfills for the ash. The ash usually contains heavy

metals and must be placed in a specially-designed landfill

to avoid leaching.

Hazardous waste incineration

For the incineration of hazardous waste, a greater de-

gree of control, higher temperatures, and a more rigorous

monitoring system are required. An incinerator burning haz-

ardous waste must be designed, constructed, and maintained

to meet

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

(RCRA) standards. An incinerator burning hazardous waste

must achieve a destruction and removal efficiency of at least

99.99 percent for each principal organic hazardous constit-

uent. For certain listed constituents such as polychlorinated

biphenyl (PCB), mass air emissions from an incinerator are

required to be greater than 99.9999%. The Toxic Substances

Control Act requires certain standards for the incineration

of PCBs. For example, the flow of PCB to the incinerator

must stop automatically whenever the combustion tempera-

ture drops below the specified value; there must be continu-

ous monitoring of the stack for a list of emissions; scrubbers

must be used for hydrochloric acid control; among others.

Recently medical wastes have been treated by steam

sterilization, followed by incineration with treatment of the

flue gases with activated

carbon

for maximum

absorption

of organic constituents. The latter system is being installed

at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, as a model

medical disposal system. See also Fugitive emissions; Solid

waste incineration; Solid waste volume reduction; Stack

emissions

[Malcolm T. Hepworth]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Brunner, C. R. Handbook of Incineration Systems. New York: McGraw-

Hill, 1991.

748

Edwards, B. H., et al. Emerging Technologies for the Control of Hazardous

Wastes. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Data Corporation, 1983.

Hickman Jr., H. L., et al. Thermal Conversion Systems for Municipal Solid

Waste. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications, 1984.

Vesilind, R. A., and A. E. Rimer. Unit Operations in Resource Recovery

Engineering. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1981.

Wentz, C. A. Hazardous Waste Management. New York: McGraw-Hill,

1989.

Incineration, solid waste

see

Solid waste incineration

Indicator organism

Indicator organisms, sometimes called bioindicators, are

plant or animal

species

known to be either particularly

tolerant or particularly sensitive to

pollution

. The health of

an organism can often be associated with a specific type or

intensity of pollution, and its presence can then be used to

indicate polluted conditions relative to unimpacted condi-

tions.

Tubificid worms are an example of organisms that

can indicate pollution. Tubificid worms live in the bottom

sediments of streams and lakes, and they are highly tolerant

of sewage. In a river polluted by

wastewater discharge

from a

sewage treatment

plant, it is common to see a

large increase in the numbers of tubificid worms in stream

sediments immediately downstream. Upstream of the dis-

charge, the numbers of tubificid worms are often much lower

or almost absent, reflecting cleaner conditions. The number

of tubificid worms also decreases downstream, as the dis-

charge is diluted.

Pollution-intolerant organisms can also be used to in-

dicate polluted conditions. The larvae of mayflies live in

stream sediments and are known to be particularly sensitive

to pollution. In a river receiving wastewater discharge, may-

flies will show the opposite pattern of tubificid worms. The

mayfly larvae are normally present in large numbers above

the discharge point; they decrease or disappear at the dis-

charge point and reappear further downstream as the effects

of the discharge are diluted.

Similar examples of indicator organisms can be found

among plants, fish, and other biological groups. Giant reed-

grass (Phragmites australis) is a common marsh plant that is

typically indicative of disturbed conditions in

wetlands

.

Among fish, disturbed conditions may be indicated by the

disappearance of sensitive species like trout which require

clear, cold waters to thrive.

The usefulness of indicator organisms is limited.

While their presence or absence provides a reliable general

picture of polluted conditions, they are often little help in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indigenous peoples

identifying the exact sources of pollution. In the sediments

of New York Harbor, for example, pollution-tolerant insect

larvae are overwhelmingly dominant. However, it is impossi-

ble to attribute the large larval populations to just one of

the sources of pollution there, which include ship traffic,

sewage and industrial discharge, and

storm runoff

.

The U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA)

is working diligently to find reliable predictors of aquatic

ecosystem health

using indicator species. Recently, the

EPA has developed standards for the usefulness of species

as ecological indicator organisms. A potential indicator spe-

cies for use in evaluating

watershed

health must successfully

pass four phases of evaluation. First, a potential indicator

organism should provide information that is relevant to soci-

etal concerns about the

environment

, not simply academi-

cally interesting information. Second, use of a potential indi-

cator organism should be feasible. Logistics, sampling costs,

and timeframe for information gathering are legitimate con-

siderations in deciding whether an organism is a potential

indicator species or not. Thirdly, enough must be known

about a potential species before it may be effectively used

as an indicator organism. Sufficient knowledge regardin! g

the natural variations to environmental flux should exist

before incorporating a species as a true watershed indicator

species. Lastly, the EPA has set a fourth criterion for evalua-

tion of indicator species. A useful indicator should provide

information that is easily interpreted by policy makers and

the public, in addition to scientists.

Additionally, in an effort to make indicator species

information more reliable, the creation of indicator species

indices are being investigated. An index is a formula or ratio

of one amount to another that is used to measure relative

change. The major advantage of developing an indicator

organism index that is somewhat universal to all aquatic

environments is that it can be tested using

statistics

. Using

mathematical statistical methods, it may be determined

whether a significant change in an index value has occurred.

Furthermore, statistical methods allow for a certain level of

confidence that the measured values repres! ent what is actu-

ally happening in

nature

. For example, a study was con-

ducted to evaluate the utility of diatoms (a kind of micro-

scopic aquatic algae) as an index of aquatic system health.

Diatoms meet all four criteria mentioned above, and various

species are found in both fresh and salt water. An index

was created that was calculated using various measurable

characteristics of diatoms that could then be evaluated statis-

tically over time and among varying sites. It was determined

that the diatom index was sensitive enough to reliably reflect

three categories of the health of an aquatic

ecosystem

.

The diatom index showed that values obtained from areas

impacted by human activities had greater variability over

time than diatom indices obtained from less disturbed loca-

749

tions. Many such indices are being developed using different

species, and multiple species in an effort to create reliable

information from indicator organisms. As more is learned

about the physiology and life history of indicator organisms

and their individual responses to different types of pollution,

it may be possible to draw more specific conclusions. See

also Algal bloom; Nitrogen cycle; Water pollution

[Terry Watkins]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Browder, J. A., ed. Aquatic Organisms As Indicators of Environmental Pollu-

tion. Bethesda, MD: American Water Resources Association, 1988.

Connell, D. W., and G. J. Miller. Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Pollution.

New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1984.

Indigenous peoples

Cultural or ethnic groups living in an area where their culture

developed or where their people have existed for many gener-

ations. Most of the world’s indigenous peoples live in remote

forests, mountains, deserts, or arctic

tundra

, where modern

technology, trade, and cultural influence are slow to pene-

trate. Many had much larger territories historically but have

retreated to, or been forced into, small, remote areas by the

advance of more powerful groups. Indigenous groups, also

sometimes known as native or tribal peoples, are usually

recognized in comparison to a country’s dominant cultural

group. In the United States the dominant, non-indigenous

cultural groups speak English, has historic roots in Europe,

and maintain strong economic, technological, and commu-

nication ties with Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world.

Indigenous groups in the United States, on the other hand,

include scores of groups, from the southern Seminole and

Cherokee to the Inuit and Yupik peoples of the Arctic coast.

These groups speak hundreds of different languages or dia-

lects, some of which have been on this continent for thou-

sands of years. Their traditional economies were based

mainly on small-scale subsistence gathering,

hunting

, fish-

ing, and farming. Many indigenous peoples around the world

continue to engage in these ancient economic practices.

It is often difficult to distinguish who is and who is

not indigenous. European-Americans and Asian-Americans

are usually not considered indigenous even if they have been

here for many generations. This is because their cultural

roots connect to other regions. On the other hand, a German

residing in Germany is also not usually spoken of as indige-

nous, even though by any strict definition she or he is indige-

nous. This is because the term is customarily reserved to

denote economic or political minorities—groups that are

relatively powerless within the countries where they live.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indonesian forest fires

Historically, indigenous peoples have suffered great

losses in both population and territory to the spread of larger,

more technologically advanced groups, especially (but not

only) Europeans. Hundreds of indigenous cultures have dis-

appeared entirely just in the past century. In recent decades,

however, indigenous groups have begun to receive greater

international recognition, and they have begun to learn effec-

tive means to defend their lands and interests—including

attracting international media attention and suing their own

governments in court. The main reason for this increased

attention and success may be that scientists and economic

development organizations have recently become interested

in biological diversity and in the loss of world rain forests.

The survival of indigenous peoples, of the world’s forests,

and of the world’s gene pools are now understood to be

deeply interdependent. Indigenous peoples, who know and

depend on some of the world’s most endangered and biologi-

cally diverse ecosystems, are increasingly looked on as a

unique source of information, and their subsistence econo-

mies are beginning to look like admirable alternatives to

large-scale

logging

, mining, and conversion of jungles to

monocrop agriculture.

There are probably between 4,000 and 5,000 different

indigenous groups in the world; they can be found on every

continent (except

Antarctica

) and in nearly every country.

The total population of indigenous peoples amounts to be-

tween 200 million and 600 million (depending upon how

groups are identified and their populations counted) out of

a world population just over 6.2 billion. Some groups number

in the millions; others comprise only a few dozen people.

Despite their world-wide distribution, indigenous groups

are especially concentrated in a number of “cultural diversity

hot spots,” including Indonesia, India, Papua New Guinea,

Australia

, Mexico, Brazil, Zaire, Cameroon, and Nigeria.

Each of these countries has scores, or even hundreds, of

different language groups. Neighboring valleys in Papua

New Guinea often contain distinct cultural groups with un-

related languages and religions. These regions are also recog-

nized for their unusual biological diversity. Both indigenous

cultures and

rare species

survive best in areas where modern

technology does not easily penetrate. Advanced technologi-

cal economies involved in international trade consume tre-

mendous amounts of land, wood, water, and minerals. Indig-

enous groups tend to rely on intact ecosystems and on a

tremendous variety of plant and animal

species

. Because

their numbers are relatively small and their technology sim-

ple, they usually do little long-lasting damage to their

envi-

ronment

despite their dependence on the resources around

them. The remote areas where indigenous peoples and their

natural environment survive, however, are also the richest

remaining reserves of

natural resources

in most countries.

Frequently state governments claim all timber, mineral,

750

water, and land rights in areas traditionally occupied by tribal

groups. In Indonesia, Malaysia, Burma (Myanmar), China,

Brazil, Zaire, Cameroon, and many other important cultural

diversity regions, timber and mining concessions are fre-

quently sold to large or international companies that can

quickly and efficiently destroy an ecological area and its

people. Usually native peoples, because they lack political

and economic clout, have no recourse to losing their homes.

Generally they are relocated, attempts are made to integrate

them into mainstream culture, and they join laboring classes

in the general economy.

Indigenous rights have begun to strengthen in recent

years. As long as international media attention continues to

give them the attention they need—especially in the form

of international economic and political pressure on state

governments—and as long as indigenous leaders are able to

continue developing their own defense strategies and legal

tactics, the survival rate of indigenous peoples and their

environments may improve significantly.

[Mary Ann Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Redford, K. H., and C. Padoch. Conservation of Neotropical Forests: Working

from Traditional Resources Use. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

O

THER

Durning, A. T. “Guardians of the Land: Indigenous Peoples and the Health

of the Earth.” Worldwatch Paper 112. Washington, DC: Worldwatch Insti-

tute, 1992.

Indonesian forest fires

For several months in 1997 and 1998, a thick pall of

smoke

covered much of Southeast Asia. Thousands of forest fires

burning simultaneously on the Indonesian islands of Kali-

mantan (Borneo) and Sumatra, are thought to have de-

stroyed about 8,000 mi

2

(20,000 km

2

) of primary forest, or

an area about the size of New Jersey. The smoke generated

by these fires spread over eight countries and 75 million

people, covering an area larger than Europe. Hazy skies and

the smell of burning forests could be detected in Hong

Kong, nearly 2,000 mi (3,200 km) away. The

air quality

in Singapore and the city of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, just

across the Strait of Malacca from Indonesia, was worse than

any industrial region in the world. In towns such as Palem-

bang, Sumatra, and Banjarmasin, Kalimantan, in the heart

of the fires, the

air pollution index

frequently passed 800,

twice the level classified in the United States as an air quality

emergency, hazardous to human health. Automobiles had

to drive with their headlights on, even at noon. People

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indonesian forest fires

groped along smoke-darkened streets unable to see or

breathe normally.

At least 20 million people in Indonesia and Malaysia

were treated for illnesses such as

bronchitis

, eye irritation,

asthma

,

emphysema

, and cardiovascular diseases. It’s

thought that three times that many who couldn’t afford

medical care went uncounted. The number of extra deaths

from this months-long episode is unknown, but it seems

likely to have been hundreds of thousands, mostly elderly

or very young children. Unable to see through the thick

haze

, several boats collided in the busy Straits of Malacca,

and a plane crashed on Sumatra, killing 234 passengers.

Cancelled airline flights, aborted tourist plans, lost workdays,

medical bills, and ruined crops are estimated to have cost

countries in the afflicted area several billion dollars.

Wildlife

suffered as well. In addition to the loss of

habitat

destroyed

by fires, breathing the noxious smoke was as hard on wild

species

as it was on people. At the Pangkalanbuun Conser-

vation Reserve, weak and disoriented orangutans were found

suffering from

respiratory diseases

much like those of

humans.

Geographical isolation on the 16,000 islands of the

Indonesian archipelago has allowed

evolution

of the world’s

richest collection of

biodiversity

. Indonesia has the second

largest expanse of tropical forest and the highest number

of

endemic species

anywhere. This makes destruction of

Indonesian plants, animals, and their habitat of special con-

cern. The dry season in tropical Southeast Asia has probably

always been a time of burning vegetation and smoky skies.

Farmers practicing traditional

slash and burn agriculture

start fires each year to prepare for the next growing season.

Because they generally burn only a hectare or two at a time,

however, these shifting cultivators often help preserve plant

and animal species by opening up space for early successional

forest stages. Globalization and the advent of large, commer-

cial plantations, however, have changed agricultural dynam-

ics. There is now economic incentive for clearing huge tracts

of forestland to plant oil palms, export foods such as pineap-

ples and sugar cane, and fast-growing eucalyptus trees. Fire

is viewed as the only practical way remove

biomass

and

convert wild forest to into domesticated land. While it can

cost the equivalent of $200 to clear a hectare of forest with

chainsaws and bulldozers, dropping a lighted match into dry

underbrush is essentially free.

In 1997 to 1998, the Indonesian forest was unusually

dry. A powerful El Nin

˜

o/Southern Oscillation weather pat-

tern caused the most severe droughts in 50 years. Forests

that ordinarily stay green and moist even during the rainless

season became tinder dry. Lightning strikes are thought to

have started many forest fires, but many people took advan-

tage of the

drought

for their own purposes. Although the

government blamed traditional farmers for setting most of

751

the fires, environmental groups claimed that the biggest fires

were caused by large agribusiness conglomerates with close

ties to the government and military. Some of these fires

were set to cover up evidence of illegal

logging

operations.

Others were started to make way for huge oil-palm planta-

tions and fast-growing pulpwood trees,

Neil Byron of the Center for International Forestry

Research was quoted as saying that “fire crews would go

into an area and put out the fire, then come back four days

later and find it burning again, and a guy standing there

with a petrol can.” According to the World Wide Fund for

Nature, 37 plantations in Sumatra and Kalimantan were

responsible for a vast majority of the forest burned on those

islands. The plantation owners were politically connected to

the ruling elite, however, and none of them was ever pun-

ished for violation of

national forest

protection laws. Indo-

nesia has some of the strongest land-use management laws

of any country in the world, but these laws are rarely en-

forced. In theory, more than 80% of its land is in some form

of protected status, either set aside as national parks or

classified as selective logging reserves where only a few trees

per hectare can be cut. The government claims to have

an ambitious reforestation program that replants nearly 1.6

million acres (1 million hectares) of harvested forest annually,

but when four times that amount is burned in a single year,

there’s not much to be done but turn it over to plantation

owners for use as agricultural land.

Aquatic life, also, is damaged by these forest fires.

Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines have the richest

coral reef

complexes in the world. More than 150 species

of coral live in this area, compared with only about 30 species

in the Caribbean. The clear water and fantastic biodiversity

of Indonesia’s reefs have made it an ultimate destination for

scuba divers and snorkelers from around the world. Unfortu-

nately,

soil

eroded from burned forests clouds coastal waters

and smothers reefs.

Perhaps one of the worst effects of large tropical forest

fires is that they may tend to be self-reinforcing. Moist

tropical forests store huge amounts of

carbon

in their stand-

ing biomass. When this carbon is converted into CO

2

by

fire and released to the

atmosphere

, it acts as a greenhouse

gas to trap heat and cause global warming. All the effects

of human-caused global

climate

change are still unknown,

but we stronger climatic events such as severe droughts may

make further fires even more likely. Alarmed by the magni-

tude of the Southeast Asia fires and the potential they repre-

sent for biodiversity losses and global climate change, world

leaders have proposed plans for international intervention

to prevent A recurrence. Fears about imposing on national

sovereignty, however, have made it difficult to come up with

a plan for how to cope with this growing threat.

[William P. Cunningham Ph.D.]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indoor air quality

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Glover, David, and Timothy Jessup, eds. Indonesia’s Fires and Haze: The

Cost of Catastrophe. Singapore: International Development Research Cen-

tre, 2002.

P

ERIODICALS

Aditama, Tjandra Yoga. “Impact of Haze from Forest Fire to Respiratory

Health: Indonesian Experience.” Respirology (2000): 169–174.

Chan, C. Y., et al. “Effects of 1997 Indonesian forest fires on tropospheric

ozone enhancement, radiative forcing, and temperature change over the

Hong Kong region” Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 106

(2001):14875-14885.

Davies, S. J. and L. Unam. “Smoke-haze from the 1997 Indonesian forest

fires: effects on pollution levels, local climate, atmospheric CO2 concentra-

tions, and tree photosynthesis.” Forest Ecology & Management

124(1999):137-144.

Murty, T. S., D. Scott, and W. Baird. “The 1997 El Nin

˜

o, Indonesian

Forest Fires and the Malaysian Smoke Problem: A Deadly Combination

of Natural and Man-Made Hazard” Natural Hazards 21 (2000): 131–144.

Tay, Simon. “Southeast Asian Fires: The Challenge Over Sustainable Envi-

ronmental Law and Sustainable Development.” Peace Research Abstracts 38

(2001): 603–751.

Indoor air quality

An assessment of

air quality

in buildings and homes based

on physical and chemical monitoring of contaminants, physi-

ological measurements, and/or psychosocial perceptions.

Factors contributing to the quality of indoor air include

lighting, ergonomics, thermal comfort,

tobacco smoke

,

noise, ventilation, and psychosocial or work-organizational

factors such as employee stress and satisfaction. “Sick build-

ing syndrome” (SBS) and “building-related illness” (BRI)

are responses to indoor

air pollution

commonly described

by office workers. Most symptoms are nonspecific; they

progressively worsen during the week, occur more frequently

in the afternoon, and disappear on the weekend.

Poor indoor air quality (IAQ) in industrial settings

such as factories,

coal

mines, and foundries has long been

recognized as a health risk to workers and has been regulated

by the U.S.

Occupational Safety and Health Administra-

tion

(OSHA). The contaminant levels in industrial settings

can be hundreds or thousands of times higher than the levels

found in homes and offices. Nonetheless, indoor air quality

in homes and offices has become an environmental priority

in many countries, and federal IAQ legislation has been

introduced in the U.S. Congress for the past several years.

However, none has yet passed, and currently the U.S.

Envi-

ronmental Protection Agency

(EPA) has no enforcement

authority in this area.

Importance of IAQ

The prominence of IAQ issues has risen in part due

to well-publicized incidents involving outbreaks of Legion-

naires’ disease, Pontiac fever,

sick building syndrome

,

mul-

752

tiple chemical sensitivity

, and

asbestos

mitigation in pub-

lic buildings such as schools. Legionnaire’s disease, for

example, caused twenty-nine deaths in 1976 in a Philadel-

phia hotel due to infestation of the building’s air conditioning

system by a bacterium called Legionella pneumophila. This

microbe affects the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and central

nervous system. It also causes the non-fatal Pontiac fever.

IAQ is important to the general public for several

reasons. First, individuals typically spend the vast majority

of their time—80–90%—indoors. Second, an emphasis on

energy conservation

measures, such as reducing air ex-

change rates in ventilation systems and using more energy

efficient but synthetic materials, has increased levels of air

contaminants in offices and homes. New “tight” buildings

have few cracks and openings so minimal fresh air enters such

buildings. Low ventilation and exchange rates can increase

indoor levels of

carbon monoxide

,

nitrogen oxides

,

ozone

, volatile organic compounds,

bioaerosols

, and pesti-

cides and maintain high levels of second-hand tobacco

smoke generated inside the building. Thus, many contami-

nants are found indoors at levels that greatly exceed outdoor

levels. Third, an increasing number of synthetic chemicals—

found in building materials, furnishing, cleaning and hygiene

products—are used indoors. Fourth, studies show that expo-

sure to indoor contaminants such as

radon

, asbestos, and

tobacco smoke pose significant health risks. Fifth, poor IAQ

is thought to adversely affect children’s development and

lower productivity in the adult population. Demands for

indoor air quality investigations of “sick” and problem build-

ings have increased rapidly in recent years, and a large frac-

tion of buildings are known or suspected to have IAQ

problems.

Indoor contaminants

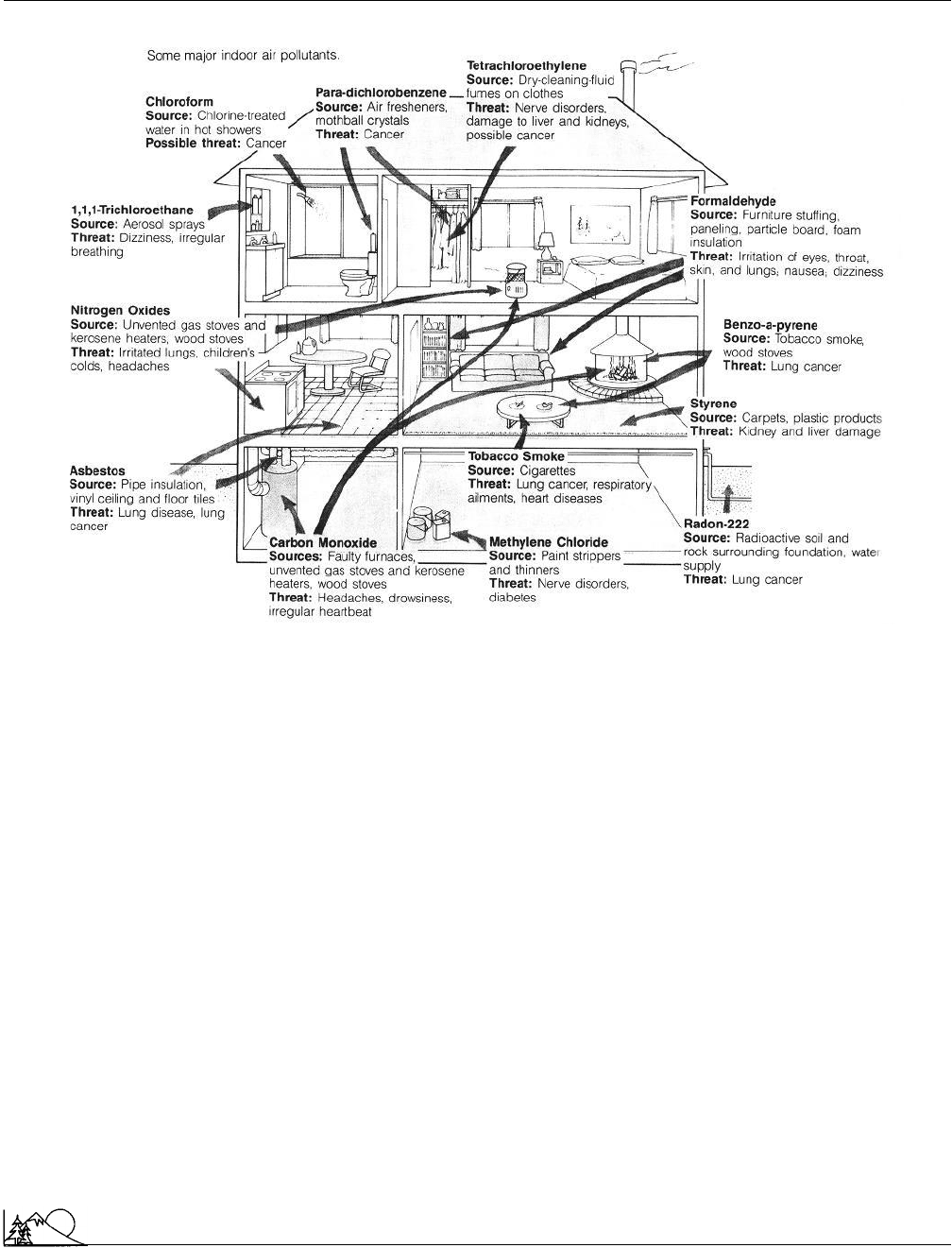

Indoor air contains many contaminants at varying but

generally low concentration levels. Common contaminants

include radon and radon progeny from the entry of

soil

gas

and

groundwater

and from concrete and other mineral-

based building materials; tobacco smoke from cigarette and

pipe smoking; formaldehyde from polyurethane foam insula-

tion and building materials; volatile organic compounds

(VOCs) emitted from binders and resins in carpets, furni-

ture, or building materials, as well as VOCs used in

dry

cleaning

processes and as

propellants

and constituents of

personal use and cleaning products, like hair sprays and

polishes; pesticides and insecticides;

carbon

monoxide,

ni-

trogen

oxides, and other

combustion

productions from gas

stoves, appliances, and vehicles; asbestos from high tempera-

ture insulation; and biological contaminants including vi-

ruses, bacteria, molds, pollen, dust mites, and indoor and

outdoor biota. Many or most of these contaminants are

present at low levels in all indoor environments.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Indoor air quality

Some major indoor air pollutants. (Wadsworth Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

The quality of indoor air can change rapidly in time

and from room to room. There are many diverse sources

that emit various physical and chemical forms of contami-

nants. Some releases are slow and continuous, such as out-

gassing associated with building and furniture materials,

while others are nearly instantaneous, like the use of cleaners

and aerosols. Many building surfaces demonstrate significant

interactions with contaminants in the form of sorption-

desorption processes. Building-specific variation in air ex-

change rates, mixing,

filtration

, building and furniture sur-

faces, and other factors alter dispersion mechanisms and

contaminant lifetimes. Most buildings employ

filters

that

can remove particles and aerosols. Filtration systems do not

effectively remove very small particles and have no effect on

gases, vapors, and odors. Ventilation and air exchange units

designed into the heating and cooling systems of buildings

are designed to diminish levels of these contaminants by

dilution. In most buildings, however, ventilation systems are

turned off at night after working hours, leading to an increase

in contaminants through the night. Though operation and

maintenance issues are estimated to cause the bulk of indoor

air quality problems, deficiencies in the design of the heating,

753

ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) system can cause

problems as well. For example, locating a building’s fresh

air intake near a truck loading dock will bring diesel fumes

and other noxious contaminants into the building.

Health impacts

Exposures to indoor contaminants can cause a variety

of health problems. Depending on the pollutant and expo-

sure, health problems related to indoor air quality may in-

clude non-malignant respiratory effects, including mucous

membrane irritation, allergic reactions, and

asthma

; cardio-

vascular effects; infectious diseases such as Legionnaires’

disease; immunologic diseases such as hypersensitivity pneu-

monitis; skin irritations; malignancies; neuropsychiatric ef-

fects; and other non-specific

systemic

effects such as leth-

argy, headache, and nausea. In addition indoor air

contaminants such as radon, formaldehyde, asbestos, and

other

chemicals

are suspected or known carcinogens. There

is also growing concern over the possible effects of low level

exposures on suppressing reproductive and growth capabili-

ties and impacting the immune, endocrine, and nervous

systems.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Industrial waste treatment

Solving IAQ problems

Acute indoor air quality problems can be greatly elimi-

nated by identifying, evaluating, and controlling the sources

of contaminants. IAQ control strategies include the use of

higher ventilation and air exchange rates, the use of lower

emission

and more benign constituents in building and

consumer products (including product use restriction regula-

tions), air cleaning and filtering, and improved building prac-

tices in new construction. Radon may be reduced by inexpen-

sive subslab ventilation systems. New buildings could

implement a day of “bake-out,” which heats the building to

temperatures over 90°F (32°C) to drive out volatile organic

compounds. Filters to remove ozone, organic compounds,

and sulfur gases may be used to condition incoming and

recirculated air. Copy machines and other emission sources

should have special ventilation systems. Building designers,

operators, contractors, maintenance personnel, and occu-

pants are recognizing that healthy buildings result from com-

bined and continued efforts to control emission sources,

provide adequate ventilation and air cleaning, and good

maintenance of building systems. Efforts toward this direc-

tion will greatly enhance indoor air quality.

[Stuart Batterman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Godish, T. Indoor Air Pollution Control. Chelsea, MI: Lewis, 1989.

Kay, J. G., et al. Indoor Air Pollution: Radon, Bioaerosols and VOCs. Chelsea,

MI: Lewis, 1991.

Samet, J. M., and J. D. Spengler. Indoor Air Pollution: A Health Perspective.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

P

ERIODICALS

Kreiss, K. “The Epidemiology of Building-Related Complaints and Ill-

nesses.” Occupational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews 4 (1989): 575–92.

Industrial waste treatment

Many different types of solid, liquid, and gaseous wastes are

discharged by industries. Most industrial waste is recycled,

treated and discharged, or placed in a

landfill

. There is no

one means of managing industrial wastes because the nature

of the wastes varies widely from one industry to another.

One company might generate a waste that can be treated

readily and discharged to the

environment

(direct

dis-

charge

) or to a sewer in which case final treatment might be

accomplished at a publicly owned treatment works (POTW).

Treatment at the company before discharge to a sewer is

referred to as pretreatment. Another company might gener-

ate a waste which is regarded as hazardous and therefore

requires special management procedures related to storage,

transportation

and final disposal.

754

The pertinent legislation governing to what extent

wastewaters need to be treated before discharge is the 1972

Clean Water Act

(CWA). Major amendments to the CWA

were passed in 1977 and 1987. The

Environmental Protec-

tion Agency

(EPA) was also charged with the responsibility

of regulating the priority pollutants under the CWA. The

CWA specifies that toxic and nonconventional pollutants

are to be treated with the Best Available Technology (BAT).

Gaseous pollutants are regulated under the

Clean Air Act

(CAA), promulgated in 1970 and amended in 1977 and

1990. An important part of the CAA consists of measures

to attain and maintain National Ambient Air Quality Stan-

dards (NAAQS). Hazardous air pollutant (HAP) emissions

are to be controlled through Maximum Achievable Control

Technology (MACT) which can include process changes,

material substitutions and/or

air pollution control

equip-

ment. The “cradle to grave” management of hazardous

wastes is to be performed in accordance with the

Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act

(RCRA) of 1976 and

the Hazardous and

Solid Waste

Amendments (HSWA)

of 1984.

In 1990, the United States, through the

Pollution

Prevention Act

, adopted a program designed to reduce the

volume and toxicity of waste discharges.

Pollution

preven-

tion (P2) strategies might involve changing process equip-

ment or chemistry, developing new processes, eliminating

products, minimizing wastes,

recycling

water or

chemicals

,

trading wastes with another company, etc. In 1991, the EPA

instituted the 33/50 program which was to result in an overall

33% reduction of 17 high priority pollutants by 1992 and a

50% reduction of the pollutants by 1995. Both goals were

surpassed. Not only has this program been successful, but

it sets an important precedence because the participating

companies volunteered. Additionally, P2 efforts have led

industries to rigorously think through product life cycles. A

Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) starts with consideration for

acquiring raw materials, moves through the stages related

to processing, assembly, service and

reuse

, and ends with

retirement/disposal. The LCA therefore reveals to industry

the costs and problems versus the benefits for every stage in

the life of a product.

In designing a

waste management

program for an

industry, one must think first in terms of P2 opportunities,

identify and characterize the various solid, liquid and gaseous

waste streams, consider relevant legislation, and then design

an appropriate waste management system. Treatment sys-

tems that rely on physical (e.g., settling, floatation, screening,

sorption

, membrane technologies, air stripping) and chemi-

cal (e.g., coagulation, precipitation, chemical oxidation and

reduction,

pH

adjustment) operations are referred to as phys-

icochemical, whereas systems in which

microbes

are cul-

tured to metabolize waste constituents are known as biologi-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

INFORM

cal processes (e.g.,

activated sludge

, trickling

filters

,

biotowers, aerated lagoons,

anaerobic digestion

,

aerobic

digestion,

composting

). Oftentimes, both physicochemical

and biological systems are used to treat solid and liquid waste

streams. Biological systems might be used to treat certain

gas streams, but most waste gas streams are treated physico-

chemically (e.g., cyclones, electrostatic precipitators,

scrubbers

, bag filters, thermal methods). Solids and the

sludges or residuals that result from treating the liquid and

gaseous waste streams are also treated by means of physical,

chemical, and biological methods.

In many cases, the systems used to treat wastes from

domestic sources are also used to treat industrial wastes.

For example, municipal wastewaters often consist of both

domestic and industrial waste. The local POTW therefore

may be treating both types of wastes. To avoid potential

problems caused by the input of industrial wastes, municipal-

ities commonly have pretreatment programs which require

that industrial wastes discharged to the sewer meet certain

standards. The standards generally include limits for various

toxic agents such as metals, organic matter measured in

terms of

biochemical oxygen demand

(bod) or

chemical

oxygen demand

, nutrients such as

nitrogen

and

phos-

phorus

, pH and other contaminants that are recognized as

having the potential to impact on the performance of the

POTW. At the other end of the spectrum, there are wastes

that need to be segregated and managed separately in special

systems. For example, an industry might generate a

hazard-

ous waste

that needs to be placed in barrels and transported

to an EPA approved treatment, storage or disposal facility

(TSDF).

Thus, it is not possible to simply use one train of

treatment operations for all industrial waste streams, but an

effective, generic strategy has been developed in recent years

for considering the waste management options available to

an industry. The basis for the strategy is to look for P2

opportunities and to consider the life cycle of a product. An

awareness of

waste stream

characteristics and the potential

benefits of stream segregation is then melded with the

knowledge of regulatory compliance issues and treatment

system capabilities/performance to minimize environmental

risks and costs.

[Gregory D. Boardman]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Freeman, H. M. Industrial Pollution Prevention Handbook. New York:

McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1995.

Haas, C.N., and R.J. Vamos. Hazardous and Industrial Waste Treatment.

Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1995.

LaGrega, M. D., P. L. Buckingham, and J. C. Evans. Hazardous Waste

Management. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994.

755

Metcalf and Eddy, Inc. Wastewater Engineering Treatment, Disposal and

Reuse. Revised by G. Tchobanoglous and F. Burton. New York: McGraw-

Hill, Inc., 1991.

Nemerow, N. L., and Dasgupta, A. Industrial and Hazardous Waste Treat-

ment. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991.

Peavy, H. S., D. R. Rowe, and G. Tchobanoglous. Environmental Engi-

neering. New York: McGraw-Hill Book, 1995.

Tchobanoglous, G., et al. Integrated Solid Waste Management Engineering

Principles and Management Issues. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1993.

P

ERIODICALS

Romanow, S., and T. E. Higgins. “Treatment of Contaminated Ground-

water from Hazardous Waste Sites—Three Case Studies.” Presented at the

60th Water Pollution Control Federation Conference, Philadelphia (October 5-

8, 1987).

Inertia

see

Resistance (inertia)

Infiltration

In

hydrology

, infiltration refers to the maximum rate at

which a

soil

can absorb precipitation. This is based on the

initial moisture content of the soil or on the portion of

precipitation that enters the soil. In soil science, the term

refers to the process by which water enters the soil, generally

by downward flow through all or part of the soil surface.

The rate of entry relative to the amount of water being

supplied by precipitation or other sources determines how

much water enters the root zone and how much runs off

the surface. See also Groundwater; Soil profile; Water table

INFORM

INFORM was founded in 1973 by environmental research

specialist Joanna Underwood and two colleagues. Seriously

concerned about

air pollution

, the three scientists decided

to establish an organization that would identify practical

ways to protect the

environment

and public health. Since

then, their concerns have widened to include

hazardous

waste

, solid

waste management

,

water pollution

, and

land, energy, and

water conservation

. The group’s primary

purpose is “to examine business practices which harm our

air, water, and land resources” and pinpoint “specific ways

in which practices can be improved.”

INFORM’s research is recognized throughout the

United States as instrumental in shaping environmental poli-

cies and programs. Legislators,

conservation

groups and

business leaders use INFORM’s authority as an acknowl-

edged basis for research and conferences. Source reduction

has become one of INFORM’s most important projects. A

decrease in the amount and/or toxicity of waste entering the

waste stream

, source reduction includes any activity by an

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

INFOTERRA (U.N. Environment Program)

individual, business, or government that lessens the amount

of solid waste—or garbage—that would otherwise have to

be recycled or incinerated. Source reduction does not include

recycling

,

municipal solid waste composting

, household

hazardous waste collection, or beverage container deposit

and return systems.

The first priority in source reduction strategies is elimi-

nation; the second,

reuse

. Public education is a crucial part

of INFORM’s program. To this end INFORM has pub-

lished Making Less Garbage: A Planning Guide for Communi-

ties. This book details ways to achieve source reduction in-

cluding buying reusable, as opposed to disposable, items;

buying in bulk; and maintaining and repairing products to

extend their lives.

INFORM’s outreach program goes well beyond its

source reduction project. The staff of over 25 full-time scien-

tists and researchers and 12 volunteers and interns makes

presentations at national and international conferences and

local workshops. INFORM representatives have also given

briefings and testimony at Congressional hearings and pro-

duced television and radio advertisements to increase public

awareness on environmental issues. The organization also

publishes a quarterly newsletter, INFORM Reports.

[Cathy M. Falk]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

INFORM, Inc., 120 Wall Street, New York, NY USA 10005 (212)

361-2400, Fax: (212) 361-2412, Email: brown@informinc.org, <http://

www.informinc.org>

INFOTERRA (U.N. Environment

Program)

INFOTERRA has its international headquarters in Kenya

and is a global information network operated by the

Earth-

watch

program of the United Nations Environment Pro-

gram (UNEP).

Under INFOTERRA, participating nations designate

institutions to be national focal points, such as the

Environ-

mental Protection Agency

(EPA) in the United States.

Each national institution chosen as a focal point, prepares

a list of its national environmental experts and selects what

it considers the best sources for inclusion in INFOTERRA’s

international directory of experts.

INFOTERRA initially used its directory only to refer

questioners to the nearest appropriate experts, but the orga-

nization has evolved into a central information agency. It

consults sources, answers public queries for information, and

756

analyzes the replies. INFOTERRA is used by governments,

industries, and researchers in 177 countries.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

UNEP-Infoterra/USA, MC 3404 Ariel Rios Building, 1200 Pennsylvania

Avenue, Washington, D.C. USA 20460 Fax: (202) 260-3923, Email:

library-infoterra@epa.gov

Injection well

Injection

wells

are used to dispose waste into the subsurface

zone. These wastes can include brine from oil and gas wells,

liquid hazardous wastes, agricultural and

urban runoff

, mu-

nicipal sewage, and return water from air-conditioning. Re-

charge wells can also be used for injecting fluids to enhance

oil recovery, injecting treated water for artificial

aquifer

recharge, or enhancing a pump-and-treat system. If the wells

are poorly designed or constructed, or if the local geology

is not sufficiently studied, injected liquids can enter an aqui-

fer and cause

groundwater

contamination. Injection wells

are regulated under the Underground Injection Control Pro-

gram of the

Safe Drinking Water Act

. See also Aquifer

restoration; Deep-well injection; Drinking-water supply;

Groundwater monitoring; Groundwater pollution; Water

table

Inoculate

To inoculate involves the introduction of

microorganisms

into a new

environment

. Originally the term referred to

the insertion of a bud or shoot of one plant into the stem

or trunk of another to develop new strains or hybrids. These

hybrid plants would be resistant to botanic disease or they

would allow greater harvests or range of climates. With the

advent of vaccines to prevent human and animal disease,

the term inoculate has come to represent injection of a serum

to prevent, cure, or make immune from disease.

Inoculation is of prime importance in that the intro-

duction of specific microorganism

species

into specific mac-

roorganisms may establish a symbiotic relationships where

each organism benefits. For example, the introduction of

mycorrhiza

fungus to plants improves the plants’ ability to

absorb nutrients from the

soil

. See also Symbiosis

Insecticide

see

Pesticide