Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

M

Robert Helmer MacArthur (1930 –

1972)

Canadian biologist and ecologist

Few scientists have combined the skills of mathematics and

biology to open new fields of knowledge the way Robert

H. MacArthur did in his pioneering work in evolutionary

ecology

. Guided by a wide-ranging curiosity for all things

natural, MacArthur had a special interest in birds and much

of his work dealt primarily with bird populations. His con-

clusions, however, were not specific to ornithology but trans-

formed both

population biology

and

biogeography

in

general.

Robert Helmer MacArthur was born in Toronto, On-

tario, Canada, on April 7, 1930, the youngest son of John

Wood and Olive (Turner) MacArthur. While Robert spent

his first seventeen years attending public schools in Toronto,

his father shuttled between the University of Toronto and

Marlboro College in Marlboro, Vermont, as a professor of

genetics. Robert MacArthur graduated from high school in

1947 and immediately immigrated to the United States to

attend Marlboro College. He received his undergraduate

degree from Marlboro in 1951 and a master’s degree in

mathematics from Brown University in 1953. Upon receiv-

ing his doctorate in 1957 from Yale University under the

direction of G. Evelyn Hutchinson, MacArthur headed for

England to spend the following year studying ornithology

with David Lack at Oxford University. When he returned

to the United States in 1958, he was appointed Assistant

Professor of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania.

As a doctoral student at Yale, MacArthur had already

proposed an ecological theory that encompassed both his

background as a mathematician and his growing knowledge

as a naturalist. While at Pennsylvania, MacArthur developed

a new approach to the frequency distribution of

species

.

One of the problems confronting ecologists is measuring

the numbers of a specific species within a geographic area—

one cannot just assume that three crows in a 10-acre corn

field means that in a 1000-acre field there will be 300 crows.

857

Much depends on the number of species occupying a

habi-

tat

, species

competition

within the habitat, food supply, and

other factors. MacArthur developed several ideas relating to

the measurement of species within a known habitat, showing

how large masses of empirical data relating to numbers of

species could be processed in a single model by employing

the principles of information theory. By taking the sum of

the product of the frequencies of occurrences of a species

and the logarithms of the frequencies, complex data could

be addressed more easily.

The most well-known theory of frequency distribution

MacArthur proposed in the late 1950s is the so-called broken

stick model. This model had been suggested by MacArthur

as one of three competing models of frequency distribution.

He proposed that competing species divide up available habi-

tat in a random fashion and without overlap, like the seg-

ments of a broken stick. In the 1960s, MacArthur noted that

the theory was obsolete. The procedure of using competing

explanations and theories simultaneously and comparing re-

sults, rather than relying on a single hypothesis, was also

characteristic of MacArthur’s later work.

In 1958, MacArthur initiated a detailed study of war-

blers in which he analyzed their

niche

division, or the way

in which the different species will to be best suited for a

narrow ecological role in their common habitat. His work

in this field earned him the Mercer Award of the

Ecological

Society of America

. In the 1960s, he studied the so-called

“species-packing problem.” Different kinds of habitat sup-

port widely different numbers of species. A

tropical rain

forest

habitat, for instance, supports a great many species,

while arctic

tundra

supports relatively few. MacArthur pro-

posed that the number of species crowding a given habitat

correlates to niche breadth. The book The Theory of Island

Biogeography, written with

biodiversity

expert Edward O.

Wilson and published in 1967, applied these and other ideas

to isolated habitats such as islands. The authors explained

the species-packing problem in an evolutionary light, as an

equilibrium between the rates at which new species arrive

or develop and the

extinction

rates of species already present.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mad cow disease

These rates vary with the size of the habitat and its distance

from other habitats.

In 1965 MacArthur left the University of Pennsylvania

to accept a position at Princeton University. Three years

later, he was named

Henry Fairfield Osborn

Professor of

Biology, a chair he held until his death. In 1971, MacArthur

discovered that he suffered from a fatal disease and had only

a few years to live. He decided to concentrate his efforts on

encapsulating his many ideas in a single work. The result,

Geographic Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Species, was

published shortly before his death the following year. Besides

a summation of work already done, Geographic Ecology was

a prospectus of work still to be carried out in the field.

MacArthur was a Fellow of the American Academy

of Arts and Science. He was also an Associate of the Smith-

sonian Tropical Research Institute, and a member of both

the Ecological Society and the National Academy of Science.

He married Elizabeth Bayles Whittemore in 1952; they had

four children: Duncan, Alan, Donald, and Elizabeth. Robert

MacArthur died of renal

cancer

in Princeton, New Jersey,

on November 1, 1972, at the age of 42.

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Carey, C. W. “MacArthur, Robert Helmer.” Vol. 14, American National

Biography edited by J. A. Garraty and M. C. Carnes. NY: Oxford University

Press, 1999.

Gillispie, Charles Coulson, ed. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 17–

18: Scribner, 1990.

MacArthur, Robert. Geographic Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Spe-

cies. Harper, 1972.

———. The Biology of Populations. Wiley, 1966.

———. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University Press, 1967.

Notable Scientists: From 1900 to the Present. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale

Group, 2002.

Mad cow disease

Mad cow disease, a relatively newly discovered malady, was

first identified in Britain in 1986, when farmers noticed that

their cows’ behavior had changed. The cows began to shake

and fall, became unable to walk or even stand, and eventually

died or had to be killed. It was later determined that a

variation of this fatal neurological disease, formally known

as Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), could be

passed on to humans.

It is still not known to what extent the population of

Britain and perhaps other countries is at risk from consump-

tion of contaminated meat and animal by-products. The

significance of the BSE problem lies in its as yet unquantifi-

able potential to not only damage Britain’s $7.5 billion beef

858

industry, but also to endanger millions of people with the

threat of a fatal brain disease.

A factor that stood out in the autopsies of infected

animals was the presence of holes and lesions in the brains,

which were described as resembling a sponge or Swiss cheese.

This was the first clue that BSE was a subtype of untreatable,

fatal brain diseases called transmissible spongiform encepha-

lopathies (TSEs). These include a very rare human malady

known as Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD), which normally

strikes just one person in a million, usually elderly or middle-

aged. In contrast to previous cases of CJD, the new bovine-

related CJD in humans is reported to affect younger people,

and manifests with unusual psychiatric and sensory abnor-

malities that differentiate it from the endemic CJD. The

BSE-related CJD has a delayed onset that includes shaky

limb movements, sudden muscle spasms, and dementia.

As the epidemic of BSE progressed, the number of

British cows diagnosed began doubling almost yearly, grow-

ing from some 7,000 cases in 1989, to 14,000 in 1990, to

over 25,000 in 1991. The incidence of CJD in Britain was

simultaneously increasing, almost doubling between 1990

and 1994 and reaching 55 cases by 1994. In response to the

problem and growing public concern, the government’s main

strategy was to issue reassurances. However, it did undertake

two significant measures to try to safeguard public health.

In July 1988, it ostensibly banned meat and bone meal from

cow feed, but failed to strictly enforce the action. In Novem-

ber 1989, a law that intended to remove those bovine body

parts considered to be the most highly infective (brain, spinal

cord, spleen, tonsils, intestines, and thymus) from the public

food supply was passed. A 1995 government report revealed

that half of the time, the law was not being adhered to by

slaughterhouses. Thus, livestock—and the public—contin-

ued to be potentially exposed to BSE.

As the disease continued to spread, so did public fears

that it might be transmissible to humans, and could represent

a serious threat to human health. But the British govern-

ment, particularly the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and

Food (MAFF), anxious to protect the multibillion dollar

cattle industry, insisted that there was no danger to humans.

However, on March 20, 1996, in an embarrassing reversal,

the government officially admitted that there could be a link

between BSE and the unusual incidence of CJD among

young people. At the time, 15 people had been newly diag-

nosed with CJD. Shocking the nation and making headlines

around the world, the Minister of Health Stephen Dorrell

announced to the House of Commons that consumption of

contaminated beef was “the most likely explanation” for the

outbreak of a new variant CJD in 10 people under the

age of 42, including several teenagers. Four dairy farmers,

including some with infected herds, had also contracted

CJD, as had a Frenchman who died in January 1996.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mad cow disease

British authorities estimated that some 163,000 British

cows had contracted BSE. But other researchers, using the

same database, put the figure at over 900,000, with 729,000

of them having been consumed by humans. In addition, an

unknown number had been exported to Europe, traditionally

a large market for British cattle and beef. Many non-meat

products may also have been contaminated. Gelatin, made

from ligaments, bones, skin, and hooves, is found in ice

cream, lipstick, candy, and mayonnaise; keratin, made from

hooves, horns, nails, and hair, is contained in shampoo; fat

and tallow are used in candles, cosmetics, deodorants, soap,

margarine, detergent, lubricants, and pesticides; and protein

meal is made into medical and pharmaceutical products,

fertilizer

, and

food additives

. Bone meal from dead cows

is used as fertilizer on roses and other plants, and is handled

and often inhaled by gardeners.

In reaction to the government announcement, sales of

beef dropped by 70%, cattle markets were deserted, and

even hamburger chains stopped serving British beef. Prime

Minister Major called the temporary reaction “hysteria” and

blamed the press and opposition politicians for fanning it.

On March 25, 1996, the

European Union

banned

the import of British beef, which had since 1990 been ex-

cluded from the United States and 14 other countries.

Shortly afterwards, in an attempt to have the European ban

lifted, Britain announced that it would slaughter all of its

1.2 million cows over the age of 30 months (an age before

which cows do not show symptoms of BSE), and began the

arduous task of killing and incinerating 22,000 cows a week.

The government later agreed to slaughter an additional

l00,000 cows considered most at risk from BSE.

A prime suspect in causing BSE is a by-product de-

rived from the rendering process, in which the unusable

parts of slaughtered animals are boiled down or “cooked” at

high temperatures to make animal feed and other products.

One such product, called meat and bone meal (MBM), is

made from the ground-up, cooked remains of slaughtered

livestock—cows, sheep, chicken, and hogs—and made into

nuggets of animal feed. Some of the cows and sheep used in

this process were infected with fatal brain disease. (Although

MBM was ostensibly banned as cattle feed in 1988, spinal

cords continued to be used.)

It is theorized that sheep could have played a major

role in initially infecting cows with BSE. For over 200 years,

British sheep have been contracting scrapie, another TSE

that results in progressive degeneration of the brain. Scrapie

causes the sheep to tremble and itch, and to “scrape” or rub

up against fences, walls, and trees to relieve the sensation.

The disease, first diagnosed in British sheep in 1732, may

have recently jumped the

species

barrier when cows ate

animal feed that contained brain and spinal cord tissue from

diseased sheep. In 1999 the World Health Organization

859

(WHO) implored high-risk countries to assess outbreaks of

BSE-like manifestations in sheep and goat stocks. In August

2002, sheep farms in the United Kingdom demonstrated to

the WHO that no increase in illnesses potentially linked to

BSE occurred in non-cattle livestock. However, that same

year, the European Union Scientific Steering Committee

(SSC) on the risk of BSE identified the United Kingdom

and Portugal as hotspots for BSE infection of domestic cattle

relative to other European nations.

Scrapie and perhaps these other spongiform brain dis-

eases are believed to be caused not by a

virus

(as originally

thought) but rather by a form of infectious protein-like

particles called prions, which are extremely tenacious, surviv-

ing long periods of high intensity cooking and heating. They

are, in effect, a new form of contagion. The first real insights

into the origins of these diseases were gathered in the 1950s

by Dr. D. Carleton Gajdusek, who was awarded the 1976

Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work. His research on the

fatal degenerative disease “kuru” among the cannibals of

Papua, New Guinea, which resulted in the now-familiar

brain lesions and cavities, revealed that the malady was

caused by consuming or handling the brains of relatives who

had just died.

In the United States, Department of Agriculture offi-

cials say that the risk of BSE and other related diseases is

believed to be small, but cannot be ruled out. No BSE has

been detected in the United States, and no cattle or processed

beef is known to have been imported from Britain since

1989. However, several hundred mink in Idaho and Wiscon-

sin have died from an ailment similar to BSE, and many of

them ate meat from diseased “downer” cows, those that fall

and cannot get up. Some experts believe that BSE can occur

spontaneously, without apparent exposure to the disease, in

one or two cows out of a million every year. This would

amount to an estimated 150–250 cases annually among the

United States cow population of some 150 million. More-

over, American feed processors render the carcasses of some

100,000 downer cows every year, thus utilizing for animal

feed cows that are possibly seriously and neurologically dis-

eased.

In June 1997, the

Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) announced a partial ban on using in cattle feed re-

mains from dead sheep, cattle, and other animals that chew

their cud. But the ruling exempts from the ban some animal

protein, as well as feed for poultry, pigs, and pets. In March

of that year, a coalition of consumer groups, veterinarians,

and federal meat inspectors had urged the FDA to include

pork in the animal feed ban, citing evidence that pigs can

develop a form of TSE, and that some may already have

done so. The coalition had recommended that the United

States adopt a ban similar to Britain’s, where protein from

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mad cow disease

French farmers protest against an allowance

they must pay to bring dead animals to the

knackery—a service that was free of charge

prior to mad cow disease.

all mammals is excluded from animal feed, and some criti-

cized the FDA’s action as “totally inadequate in protecting

consumers and public health.”

860

The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

has reclassified CJD that is associated with the interspecies

transmission of BSE disease-causing factor. The current

categorization of CJD is termed new variant CJD (nvCJD)

to distinguish it from the extremely rare form of CJD that

is not associated with BSE contagion. According to the

CDC, there have been 79 nvCJD deaths reported worldwide.

By April 2002, the global incidence of nvCJD increased to

125 documented reports. Of these, most (117) were from

the United Kingdom. Other countries reporting nvCJD in-

cluded France, Ireland, and Italy. The CDC stresses that

nvCJD should not be confused with the endemic form of

CJD. In the United States, CJD seldom occurs in adults

under 30 years old, having a median age of death of 68

years. In contrast, nvCJD, associated with BSE, tends to

affect a much younger segment of society. In the United

Kingdom, the median age of death from nvCJD is 28 years.

As of April 2002, no cases of nvCJD have been reported in

the United States, and all known worldwide cases of nvCJD

have been associated with countries where BSE is known

to exist. The first possible infection of a U.S. resident was

documented and reported by the CDC in 2002. A 22-year-

old citizen of the United Kingdom living in Florida was

preliminarily diagnosed with nvCJD during a visit abroad.

Unfortunately, the only way to verify a diagnosis with nvCJD

is via brain biopsy or autopsy. If confirmed, the CDC and

Florida Department of Health claim that this case would

be the first reported in the United States.

The outlook for BSE is uncertain. Since tens of mil-

lions of people in Britain may have been exposed to the

infectious agent that causes BSE, plus an unknown number

in other countries, some observers fear that a latent epidemic

of serious proportions could be in the offing. (There is also

concern that some of the four million Americans alone now

diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease may actually be suffering

from CJD.) There are others who feel that a general removal

of most infected cows and animal brain tissue from the food

supply has prevented a human health disaster. But since the

incubation period for CJD is thought to be 7–40 years, it

will be some time before it is known how many people are

already infected and the extent of the problem becomes

apparent.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Rhodes, R. Deadly Feasts. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

P

ERIODICALS

Blakeslee, S. “Fear of Disease Prompts New Look at Rendering.” The New

York Times, March 11, 1997.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Malaria

Lanchester, J. “A New Kind of Contagion.” The New Yorker, December

2, 1996.

Madagascar

Described as a crown jewel among earth’s ecosystems, this

1,000-mi long (1,610-km) island-continent is a microcosm

of

Third World

ecological problems. It abounds with unique

species

which are being threatened by the exploding human

population. Many scientists consider Madagascar the world’s

foremost

conservation

priority. Since 1984 united efforts

have sought to slow the island’s deterioration, hopefully

providing a model for treating other problem areas.

Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island, with

a

rain forest climate

in the east,

deciduous forest

in the

west, and thorn scrub in the south. Its Malagasy people

are descended from African and Indonesian seafarers who

arrived about 1,500 years ago. Most farm the land using

ecologically devastating

slash and burn agriculture

which

has turned Madagascar into the most severely eroded land

on earth. It has been described as an island with the shape,

color, and fertility of a brick; second growth forest does not

do well.

Having been separated from Africa for 160 million

years, this unique land was sufficiently isolated during the

last 40 million years to become a laboratory of

evolution

.

There are 160,000 unique species, mostly in the rapidly

disappearing eastern rain forests. These include 65 percent

of its plants, half of its birds, and all of its reptiles and

mammals. Sixty percent of the earth’s chameleons live here.

Lemurs, displaced elsewhere by monkeys, have evolved into

26 species. Whereas Africa has only one species of baobab

tree, Madagascar has six, and one is termite resistant. The

thorn scrub abounds with potentially useful poisons evolved

for plant defense. One species of periwinkle provides a sub-

stance effective in the treatment of childhood (lymphocytic)

leukemia

.

Humans have been responsible for the loss of 93 per-

cent of tropical forest and two-thirds of rain forest. Four-

fifths of the land is now barren as the result of

habitat

destruction set in motion by the exploding human population

(3.2 percent growth per year). Although

nature

reserves

date from 1927, few Malagasy have ever experienced their

island’s biological wonders; urbanites disdain the bush, and

peasants are driven by hunger. If they can see Madagascar’s

rich ecosystems first hand, it may engender respect which,

in turn, may encourage understanding and protection.

The people are awakening to their loss and the impact

this may have on all Madagascar’s inhabitants. Pride in their

island’s unique

biodiversity

is growing. The

World Bank

has provided $90 million to develop and implement a 15-

year Environmental Action Plan. One private preserve in

861

the south is doing well and many other possibilities exist

for the development of

ecotourism

.If

population growth

can be controlled, and high yield farming replaces

slash

and

burn agriculture, there is yet hope for preserving the diversity

and uniqueness of Madagascar. See also Deforestation; Ero-

sion; Tropical rain forest

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Attenborough, D. Bridge to the Past: Animals and People of Madagascar.

New York: Harper, 1962.

Harcourt, C., and J. Thornback. Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros:

The IUCN Red Data Book. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 1990.

Jenkins, M. D. Madagascar: An Environmental Profile. Gland, Switzerland:

IUCN, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

Jolly, A. “Madagascar: A World Apart.” National Geographic 171 (February

1987): 148–83.

Magnetic separation

An on-going problem of environmental significance is

solid

waste

disposal. As the land needed to simply throw out

solid wastes becomes less available,

recycling

becomes a

greater priority in

waste management

programs. One step

in recycling is the magnetic separation of ferrous (iron-

containing) materials. In a typical recycling process, wastes

are first shredded into small pieces and then separated into

organic and inorganic fractions. The inorganic fraction is

then passed through a magnetic separator where ferrous

materials are extracted. These materials can then be purified

and reused as scrap iron. See also Iron minerals; Resource

recovery

Malaria

Malaria is a disease that affects hundreds of millions of

people worldwide. In the developing world malaria contri-

butes to a high infant

mortality

rate and a heavy loss of

work time. Malaria is caused by the single-celled protozoan

parasite, Plasmodium. The disease follows two main courses:

tertian (three day) malaria and quartan (four day) malaria.

Plasmodium vivax causes benign tertian malaria with a low

mortality (5%), while Plasmodium falciparum causes malig-

nant tertian malaria with a high mortality (25%) due to

interference with the blood supply to the brain (cerebral

malaria). Quartan malaria is rarely fatal.

Plasmodium is transmitted from one human host to

another by female mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles. Thou-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Male contraceptives

sands of

parasites

in the salivary glands of the mosquito

are injected into the human host when the mosquito takes

blood. The parasites (in the sporozoite stage) are carried to

the host’s liver where they undergo massive multiplication

into the next stage (cryptozoites). The parasites are then

released into the blood stream, where they invade red blood

cells and undergo additional division. This division ruptures

the red blood cells and releases the next stage (the merozo-

ites), which invade and destroy other red blood cells. This

red blood cell destruction phase is intense but short-lived.

The merozoites finally develop into the next stage (gameto-

cytes) which are ingested by the biting mosquito.

The pattern of chills and fever characteristic of malaria

is caused by the massive destruction of the red blood cells

by the merozoites and the accompanying release of parasitic

waste products. The attacks subside as the immune response

of the human host slows the further development of the

parasites in the blood. People who are repeatedly infected

gradually develop a limited immunity. Relapses of malaria

long after the original infection can occur from parasites

that have remained in the liver, since treatment with drugs

kills only the parasites in the blood cells and not in the liver.

Malaria can be prevented or cured by a wide variety of drugs

(quinine, chloroquine, paludrine, proguanil, or pyrimeth-

amine). However, resistant strains of the common

species

of

Plasmodium mean that some prophylactic drugs (chloroquine

and pyrimethamine) are no longer totally effective.

Malaria is controlled either by preventing contact be-

tween humans and mosquitoes or by eliminating the mos-

quito vector. Outdoors, individuals may protect themselves

from mosquito bites by wearing protective clothing, applying

mosquito repellents to the skin, or by burning mosquito

coils that produce

smoke

containing insecticidal pyrethrins.

Inside houses, mosquito-proof screens and nets keep the

vectors out, while insecticides (DDT) applied inside the

house kill those that enter. The aquatic stages of the mos-

quito can be destroyed by eliminating temporary breeding

pools, by spraying ponds with synthetic insecticides, or by

applying a layer of oil to the surface waters. Biological control

includes introducing fish (Gambusia) that feed on mosquito

larvae into small ponds. Organized campaigns to eradicate

malaria are usually successful, but the disease is sure to return

unless the measures are vigilantly maintained. See also Epide-

miology; Pesticide

[Neil Cumberlidge Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Bullock, W. L. People, Parasites, and Pestilence: An Introduction to the Natural

History of Infectious Disease. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company,

1982.

862

Knell, A. J., ed. Malaria: A Publication of the Tropical Programme of the

Wellcome Trust. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Markell, E. K., M. Voge, and D. T. John. Medical Parasitology. 7th ed.

Philadelphia: Saunders, 1992.

Phillips, R. S. Malaria. Institute of Biology’s Studies in Biology, No. 152.

London: E. Arnold, 1983.

Male contraceptives

Current research into male contraceptives will potentially

increase the equitability of

family planning

between males

and females. This shift will also have the potential to address

issues of

population growth

and its related detrimental

effects on the

environment

.

While prophylactic condoms provide good barrier pro-

tection from unwanted pregnancies, they are not as effective

as oral contraceptives for women. Likewise, vasectomies are

very effective, but few men are willing to undergo the surgery.

There are three general categories of male contraceptives that

are being explored. The first category functionally mimics a

vasectomy by physically blocking the vas deferens, the chan-

nel that carries sperm from the seminiferous tubules to the

ejaculatory duct. The second uses heat to induce temporary

sterility. The third involves medications to halt sperm pro-

duction. In essence, this third category concerns the develop-

ment of “The Pill” for men.

Despite its near 100% effectiveness, there are two ma-

jor disadvantages to vasectomy that make it unattractive to

many men as an option for contraception. The first is the

psychological component relating to surgery. Although va-

sectomies are relatively non-invasive, when compared to tak-

ing a pill the procedure seems drastic. Second, although

vasectomies are reversible, the rate of return to normal fertil-

ity is only about 40%. Therefore, newer “vas occlusive” meth-

ods offer alternatives to vasectomy with completely reversible

effects. Vas occlusive devices block the flow of or render

dysfunctional the sperm in the vas deferens. The most recent

form of vas occlusive male contraception, called Reversible

Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance (RISUG), involves

the use of a

styrene

that is combined with the chemical

DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). The complex is injected into

the vas deferens. The complex then partially occludes passage

of sperm and also causes disruption of sperm cell membranes.

As sperm cells contact the RISUG complex, they rupture.

It is believed that a single injection of RISUG may provide

contraception for up to 10 years. Large safety and efficacy

trials examining RISUG are being conducted in India.

Two additional vas occlusive methods of male contra-

ception involve the injection of polymers into the vas defer-

ens. Both methods involve injection of a liquid form of

polymer, microcellular polyurethane (MPU) or medical-

grade silicon

rubber

(MSR), into the vas deferens where it

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Man and the Biosphere Program

hardens within 20 minutes. The resulting plug provides a

barrier to sperm. The technique was developed in China,

and since 1983 some 300,000 men have reportedly under-

gone this method of contraception. Reversal of MPU and

MSR plugs requires surgical removal of the polymers. An-

other method involving silicon plugs (called the Shug for

short) offers an alternative to injectable plugs. This double-

plug design offers a back-up plug should sperm make their

way past the first.

Human sperm is optimally produced at a temperature

that is a few degrees below body temperature. Infertility is

induced if the temperature of the testes is elevated. For this

reason, men trying to conceive are often encouraged to avoid

wearing snugly-fitting undergarments. The thermal suspen-

sory method of male contraception utilizes specially designed

suspensory briefs to use natural body heat or externally ap-

plied heat to suppress spermatogenesis. Such briefs hold the

testes close to the body during the day, ideally near the

inguinal canal where local body heat is greatest. Sometimes

this method is also called artificial cryptorchidism since is

simulates the infertility seen in men with undescended testi-

cles. When worn all day, suspensory briefs lead to a gradual

decline in sperm production. The safety of briefs that contain

heating elements to warm the testes is being evaluated. Ex-

ternally applied heat in such briefs would provide results in

a fraction of the time required using body heat. Other forms

of thermal suppression of sperm production utilize simple

hot water heated to about 116°F(46.7°C). Immersion of the

testicles in the warm water for 45 minutes daily for three

weeks is said to result in six months of sterility followed by

a return to normal fertility. A newer, but essentially identical,

method of thermal male contraception uses ultrasound. This

simple, painless, and convenient method using ultrasonic

waves to heat water results in six-month, reversible sterility

within only 10 minutes.

Drug therapy is also being evaluated as a potential form

of male contraception. Many drugs have been investigated in

male contraception. An intriguing possibility is the observa-

tion that a particular class of blood pressure medications,

called calcium channel blockers, induces reversible sterility

in many men. One such drug, nifedipine, is thought to

induce sterility by blocking calcium channels of sperm cell

membranes. This reportedly results in cholesterol deposition

and membrane instability of the sperm, rendering them inca-

pable of fertilization. Herbal preparations have also been

used as male contraceptives. Gossypol, a constituent of cot-

tonseed oil, was found to be an effective and reliable male

contraceptive in very large-scale experiments conducted in

China. Unfortunately, an unacceptable number of men expe-

rienced persistent sterility when gossypol therapy was discon-

tinued. Additionally, up to 10% of men treated with gossypol

experienced kidney problems in the studies conducted in

863

China. Because of the potential toxicity of gossypol, the

World Health Organization concluded that research on this

form of male contraception should be abandoned. Most

recently, a form of sugar that sperm interact with in the

fertilization process has been isolated from the outer coating

of human eggs. An

enzyme

in sperm, called N-acetyl-beta-

D-hexosaminidase (HEX-B) cuts through the protective

outer sugar layer of the egg during fertilization. A decoy

sugar molecule that mimics the natural egg coating is being

investigated. The synthetic sugar would bind specifically

to sperm HEX-B enzyme, curtailing the sperm’s ability to

penetrate the egg’s outer coating. Related experiments in

male rats have shown effective and reversible contraceptive

properties.

Perhaps one of the most researched methods of male

contraception using drugs involves the use of hormones. Like

female contraceptive pills, Male Hormone Contraceptives

(MHCs) seek to stop the production of sperm by stopping

the production of hormones that direct the development of

sperm. Many hormones in the human body work by feedback

mechanisms. When levels of one hormone are low, another

hormone is released that results in an increase in the first.

The goal of MHCs is to artificially raise the levels of hor-

mone that would result in suppression of hormone release

required for sperm production. The best MHC produced

only provides about 90% sperm suppression, which is not

enough to reliably prevent conception. Also, for poorly un-

derstood reasons, some men do not respond to the MHC

preparations under investigation. Despite initial promise,

more research is needed to make MHCs competitive with

female contraception. Response failure rates for current

MHC drugs range from 5–20%.

[Terry Watkins]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Contraceptive Research and Development Program (CONRAD), Eastern

Virginia Medical School, 1611 North Kent Street, Suite 806, Arlington,

VA USA 22209 (703) 524-4744, Fax: (703) 524-4770, Email:

info@conrad.org, <http://www.conrad.org>

Malignant tumors

see

Cancer

Man and the Biosphere Program

The Man and the

Biosphere

(MAB) program is a global

system of biosphere reserves begun in 1986 and organized

by the United Nations Educational, Social, and Cultural

Organization (

UNESCO

). MAB reserves are designed to

conserve natural ecosystems and

biodiversity

and to incor-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Manatees

porate the sustainable use of natural ecosystems by humans

in their operation. The intention is that local human needs

will be met in ways compatible with resource

conservation

.

Furthermore, if local people benefit from tourism and the

harvesting of surplus

wildlife

, they will be more supportive

of programs to preserve

wilderness

and protect wildlife.

MAB reserves differ from traditional reserves in a

number of ways. Instead of a single boundary separating

nature

inside from people outside, MAB reserves are zoned

into concentric rings consisting of a core area, a

buffer

zone,

and a transition zone. The core area is strictly managed for

wildlife and all human activities are prohibited, except for

restricted scientific activity such as

ecosystem

monitoring.

Surrounding the core area is the buffer zone, where non-

destructive forms of research, education, and tourism are

permitted, as well as some human settlements. Sustainable

light resource extraction such as

rubber

tapping, collection

of nuts, or selective

logging

is permitted in this area. Pre-

existing settlements of

indigenous peoples

are also allowed.

The transition zone is the outermost area, and here increased

human settlements, traditional

land use

by native peoples,

experimental research involving ecosystem manipulations,

major restoration efforts, and tourism are allowed.

The MAB reserves have been chosen to represent the

world’s major types of regional ecosystems. Ecologists have

identified some 14 types of biomes and 193 types of ecosys-

tems around the world and about two-thirds of these ecosys-

tem types are represented so far in the 276 biosphere reserves

now established in 72 countries. MAB reserves are not neces-

sarily pristine wilderness. Many include ecosystems that have

been modified or exploited by humans, such as

rangelands

,

subsistence farmlands, or areas used for

hunting

and fishing.

The concept of biosphere reserves has also been extended

to include coastal and marine ecosystems, although in this

case the use of core, buffer, and transition areas is inappro-

priate.

The establishment of a global network of biosphere

reserves still faces a number of problems. Many of the MAB

reserves are located in debt-burdened developing nations,

because many of these countries lie in the biologically rich

tropical regions. Such countries often cannot afford to set

aside large tracts of land, and they desperately need the

short-term cash promised by the immediate exploitation of

their lands. One response to this problem is the debt for

nature swaps in which a conservation organization buys the

debt of a nation at a discount rate from banks in exchange

for that nation’s commitment to establish and protect a

nature reserve.

Many reserves are effectively small, isolated islands of

natural ecosystems surrounded entirely by developed land.

The protected organisms in such islands are liable to suffer

genetic

erosion

, and many have argued that a single large

864

reserve would suffer less genetic erosion than several smaller

reserves which cumulatively protect the same amount of

land. It has also been suggested that reserves sited as close

to each other as possible, and corridors that allow movement

between them, would increase the

habitat

and

gene pool

available to most

species

.

[Neil Cumberlidge Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gregg, W. P., and S. L. Krugman, eds. Proceedings of the Symposium on

Biosphere Reserves. Atlanta, GA: U.S. National Park Service, 1989.

Office of Technology Assessment. Technologies to Maintain Biological Diver-

sity. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1988.

P

ERIODICALS

Batisse, M. “Developing and Focusing the Biosphere Reserve Concept.

Nature and Resources 22 (1986): 1–10.

Manatees

A relative of the elephant, manatees are totally aquatic, her-

bivorous mammals of the family Trichechidae. This group

arose 15–20 million years ago during the Miocene period,

a time which also favored the development of a tremendous

diversity of aquatic plants along the coast of South America.

Manatees are adapted to both marine and freshwater habitats

and are divided into three distinct

species

: the Amazonian

manatee (Trichechus inunguis), restricted to the freshwaters

of the Amazon River; the West African manatee (Trichechus

senegalensis), found in the coastal waters from Senegal to

Angola; and the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus),

ranging from the northern South American coast through

the Caribbean to the southeastern coastal waters of the

United States. Two other species, the dugong (Dugong du-

gon) and Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), along with

the manatees, make up the order Sirenia. Steller’s sea cow

is now extinct, having been exterminated by man in the

mid-1700s for food.

These animals can weigh 1,000–1,500 lb (454–680

kg) and grow to be more than 12 ft (3.7 m) long. Manatees

are unique among aquatic mammals because of their herbivo-

rous diet. They are non-ruminants, therefore, unlike cows

and sheep, they do not have a chambered stomach. They

do have, however, extremely long intestines (up to 150 ft/46

m) that contain a paired blind sac where bacterial digestion of

cellulose takes place. Other unique traits of the manatee

include horizontal replacement of molar teeth and the pres-

ence of only six cervical, or neck, vertebrae, instead of seven

as in all other mammals. The intestinal sac and tooth replace-

ment are adaptations designed to counteract the defenses

evolved by the plants that the manatees eat. Several plant

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Manatees

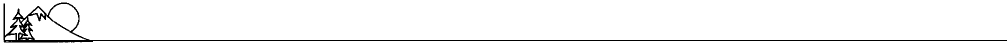

Manatee with a researcher, Homosassa Springs, Florida. (Photograph by Faulkner. Photo Researchers Inc. Reproduced by

permission.)

species contain tannins, oxalates, and

nitrates

, which are

toxic, but which may be detoxified in the manatee’s intestine.

Other plant species contain silica spicules, which, due to

their abrasiveness, wear down the manatee’s teeth, necessi-

tating the need for tooth replacement. The life span of

manatees is long, greater than 30 years, but their reproductive

rate is low, with gestation being 13 months and females

giving birth to one calf every two years. Because of this the

potential for increasing the population is low, thus leaving

the population vulnerable to environmental problems.

Competition

for food is not a problem. In contrast to

terrestrial herbivores, which have a complex division of food

resources and competition for the high-energy level land

plants, manatees have limited competition from

sea turtles

.

This is minimized by different feeding strategies employed

within the two groups. Sea turtles eat blades of seagrasses

at greater depths than manatees feed, and manatees tend to

eat not only the blades, but also the rhizomes of these plants,

which contain more energy for the warm-blooded mammals.

Because manatees are docile creatures and a source

of food, they have been exploited by man to the point of

865

extinction

. There are currently between 1,500 and 3,000 in

the U.S. Also because manatees are slow moving, a more

recent threat is taking its toll on these shallow-swimming

animals. Power boat propellers have struck hundreds of man-

atees in recent years, causing 90% of the man-related mana-

tee deaths. This has also resulted in permanent injury or

scarring to others.

Conservation

efforts, such as the

Marine

Mammals Protection Act

of 1972 and the

Endangered

Species Act

of 1973, have helped reduce some of these

problems but much more will have to be done to prevent

the extirpation of the manatees.

[Eugene C. Beckham]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Ridgway, S. H., and R. Harrison, eds. Handbook of Marine Mammals. Vol.

3, The Sirenians and Baleen Whales. London: Academic Press, 1985.

O

THER

Manatees of Florida. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.xtalwind.net/~cfa>.

Save the Manatees Club. [cited May 2002]. <http://www.savethemana-

tee.org>.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mangrove swamp

Mangrove swamp

Mangrove swamps or forests are the tropical equivalent of

temperate salt marshes. They grow in protected coastal em-

bayments in tropical and subtropical areas around the world,

and some scientists estimate that 60-75 percent of all tropical

shores are populated by mangroves.

The term “mangrove” refers to individual trees or shrubs

that are angiosperms (flowering plants) and belong to more

than 80

species

within 12 genera and five families. Though

unrelated taxonomically, they share some common character-

istics. Mangroves only grow in areas with minimal wave ac-

tion, high

salinity

, and low

soil

oxygen. All of the trees have

shallow roots, form pure stands, and have adapted to the harsh

environment

in which they grow. The mangrove swamp or

forest community as a whole is called a mangal.

Mangroves typically grow in a sequence of zones from

seaward to landward. This zonation is most highly pro-

nounced in the Indo-Pacific regions, where 30-40 species

of mangroves grow. Starting from the shore-line and moving

inland, the sequence of genera there is Avicennia followed by

Rhizophora, Bruguiera, and finally Ceriops. In the Caribbean,

including Florida, only three species of trees normally grow:

red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) represent the pioneer

species growing on the water’s edge, black mangroves (Avi-

cennia germinans) are next, and white mangroves (Laguncula-

ria racemosa) grow mostly inland. In addition, buttonwood

(Conocarpus erectus) often grows between the white man-

groves and the terrestrial vegetation.

Mangrove trees have made special adaptations to live in

this environment. Red mangroves form stilt-like prop roots

that allow them to grow at the shoreline in water up to several

feet deep. Like cacti, they have thick succulent leaves which

store water and help prevent loss of moisture. They also pro-

duce seeds which germinate directly on the tree, then drop

into the water, growing into a long, thin seedling known as a

“sea pencil.” These seedlings are denser at one end and thus

float with the heavier hydrophilic (water-loving) end down.

When the seedlings reach shore, they take root and grow. One

acre of red mangroves can produce three tons of seeds per year,

and the seeds can survive floating on the ocean for more than

12 months. Black mangroves produce straw-like roots called

pneumatophores which protrude out of the

sediment

, thus

enabling them to take oxygen out of the air instead of the

anaerobic

sediments. Both white and black mangroves have

salt glands at the base of their leaves which help in the regula-

tion of osmotic pressure.

Mangrove swamps are important to humans for several

reasons. They provide water-resistant wood used in con-

struction, charcoal, medicines, and dyes. The mass of prop

roots at the shoreline also provides an important

habitat

for a rich assortment of organisms, such as snails, barnacles,

866

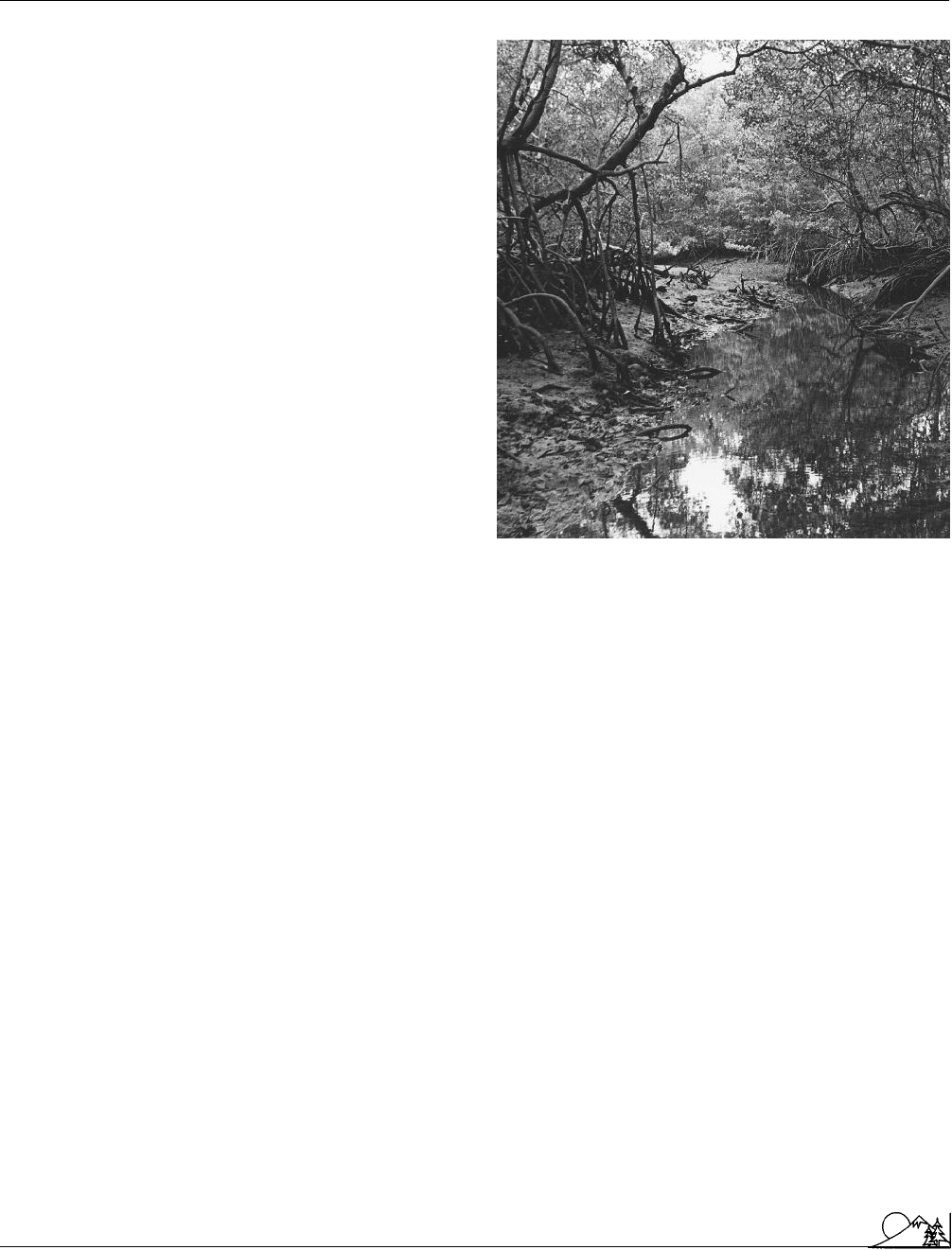

Mangrove creek in the Everglades National

Park. (Photograph by Max & Bea Hunn. Visuals Unlim-

ited. Reproduced by permission.)

oysters, crabs, periwinkles, jellyfish, tunicates, and many spe-

cies of fish. One group of these fish, called mud skippers

(Periophthalmus), have large bulging eyes, seem to skip over

the mud, and crawl up on the prop roots to catch insects

and crabs. Birds such as egrets and herons feed in these

productive waters and nest in the tree branches. Prop roots

tend to trap sediment and can thus form new land with

young mangroves. Scientists reported a growth rate of 656

feet (200 m) per year in one area near Java. These coastal

forests can be helpful

buffer

zones to strong storms.

Despite their importance, mangrove swamps are fragile

ecosystems whose ecological importance is commonly unrec-

ognized. They are being adversely affected worldwide by in-

creased

pollution

, use of herbicides, filling,

dredging

, chan-

nelizing, and

logging

. See also Marine pollution; Wetlands

[John Korstad]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Castro, P., and M. E. Huber. Marine Biology. St. Louis: Mosby, 1992.

Nybakken, J. W. Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach. 2d ed. New York:

Harper & Row, 1988.

Tomlinson, P. B. The Botany of Mangroves. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press, 1986.