Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Life cycle assessment

specifically the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. The charac-

teristic common to all types of leukemia is the uncontrolled

proliferation of leukocytes (white blood cells) in the blood

stream. This results in a lack of normal bone marrow growth,

and bone marrow is replaced by immature and undifferenti-

ated leukocytes or “blast cells.” These immature and undif-

ferentiated cells then migrate to various organs in the body,

resulting in the pathogenesis of normal organ development

and processing.

Leukemia occurs with varying frequencies at different

ages, but it is most frequent among the elderly who experi-

ence 27,000 cases a year in the United States to 2,200 cases

a year for younger people. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia,

most common in children, is responsible for two-thirds of

all cases. Acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia and chronic

lymphocytic leukemia are most common among adults—

they are responsible for 8,000 and 9,600 cases a year respec-

tively. The geographical sites of highest concentration are

the United States, Canada, Sweden, and New Zealand.

While there is clear evidence that some leukemias are linked

to genetic traits, the origins of this disease in most cases

is mysterious. It seems clear, however, that environmental

exposure to radiation, toxic substances, and other risk factors

plays an important role in many leukemias. See also Cancer;

Carcinogen; Radiation exposure; Radiation sickness

Lichens

Lichens are composed of

fungi

and algae. Varying in color

from pale whitish green to brilliant red and orange, lichens

usually grow attached to rocks and tree trunks and appear

as thin, crusty coatings, as networks of small, branched

strands, or as flattened, leaf-like forms. Some common li-

chens are reindeer moss and the red “British soldiers.” There

are approximately 20,000 known lichen

species

. Because

they often grow under cold, dry, inhospitable conditions,

they are usually the first plants to colonize barren rock sur-

faces.

The fungus and the alga form a symbiotic relationship

within the lichen. The fungus forms the body of the lichen,

called the thallus. The thallus attaches itself to the surface

of a rock or tree trunk, and the fungal cells take up water

and nutrients from the

environment

. The algal cells grow

inside the fungal cells and perform

photosynthesis

,asdo

other plant cells, to form carbohydrates.

Lichens are essential in providing food for other organ-

isms, breaking down rocks, and initiating

soil

building. They

are also important indicators and monitors of

air pollution

effects. Since lichens grow attached to rock and tree surfaces,

they are fully exposed to airborne pollutants, and chemical

analysis of lichen tissues can be used to measure the quantity

837

of pollutants in a particular area. For example,

sulfur diox-

ide

, a common

emission

from

power plants

, is a major

air pollutant. Many studies show that as the concentrations

of sulfur dioxide in the air increase, the number of lichen

species decreases. The disappearance of lichens from an area

may be indicative of other, widespread biological impacts.

Sometimes, lichens are the first organisms to transfer

contaminants to the food chain. Lichens are abundant

through vast regions of the arctic

tundra

and form the main

food source for caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in winter. The

caribou are hunted and eaten by northern Alaskan Eskimos

in spring and early summer. When the effects of

radioactive

fallout

from weapons-testing in the arctic tundra were stud-

ied, it was discovered that lichens absorbed virtually all of

the

radionuclides

that were deposited on them. Strontium-

90 and cesium-137 were two of the major radionuclide con-

taminants. As caribou grazed on the lichens, these radionu-

clides were absorbed into the caribous’ tissues. At the end

of the winter, caribou flesh contained three to six times as

much cesium-137 as it did in the fall. When the caribou

flesh was consumed by the Eskimos, the radionuclides were

transferred to them as well. See also Indicator organism;

Symbiosis

[Usha Vedagiri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Connell, D. W., and G. J. Miller. Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Pollution.

New York: Wiley, 1984.

Smith, R. L., and T. M. Smith Ecology and Field Biology. 6th ed. Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002.

Weier, T. E., et al. Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology. New York:

Wiley, 1982.

Life cycle assessment

Life cycle assessment (or LCA) refers to a process in indus-

trial

ecology

by which the products, processes, and facilities

used to manufacture specific products are each examined for

their environmental impacts. A balance sheet is prepared

for each product that considers: the use of materials; the

consumption of energy; the

recycling

, re-use, and/or dis-

posal of non-used materials and energy (in a less-enlightened

context, these are referred to as “wastes"); and the recycling

or re-use of products after their commercial life has passed.

By taking a comprehensive, integrated look at all of these

aspects of the manufacturing and use of products, life cycle

assessment finds ways to increase efficiency, to re-use, re-

duce, and recycle materials, and to lessen the overall environ-

mental impacts of the process.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Limits to Growth

(1972) and

Beyond the Limits

(1992)

Lignite

see

Coal

Limits to Growth

(1972) and

Beyond

the Limits

(1992)

Published at the height of the oil crisis in the 1970s, the

Limits to Growth study is credited with lifting environmental

concerns to an international and global level. Its fundamental

conclusion is that if rapid growth continues unabated in the

five key areas of population, food production, industrializa-

tion,

pollution

, and consumption of nonrenewable

natural

resources

, the planet will reach the limits of growth within

100 years. The most probable result will be a “rather sudden

and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial

capacity.”

The study grew out of an April 1968 meeting of 30

scientists, educators, economists, humanists, industrialists,

and national and international civil servants who had been

brought together by Dr. Aurelio Peccei, an Italian industrial

manager and economist. Peccei and the others met at the

Accademia dei Lincei in Rome to discuss the “present and

future predicament of man,” and from their meeting came

the

Club of Rome

. Early meetings of the club resulted in a

decision to initiate the Project on the Predicament of Man-

kind, intended to examine the array of problems facing all

nations. Those problems ranged from poverty amidst plenty

and

environmental degradation

to the rejection of tradi-

tional values and various economic disturbances.

In the summer of 1970, Phase One of the project took

shape during a series of meetings in Bern, Switzerland and

Cambridge, Massachusetts. At a two-week meeting in Cam-

bridge, Professor Jay Forrester of the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology (MIT) presented a global model for analyzing

the interacting components of world problems. Professor

Dennis Meadows led an international team in examining

the five basic components, mentioned above, that determine

growth on this planet and its ultimate limits. The team’s

research culminated in the 1972 publication of the study,

which touched off intense controversy and further research.

Underlying the study’s dramatic conclusions is the cen-

tral concept of

exponential growth

, which occurs when a

quantity increases by a constant percentage of the whole in

a constant time period. “For instance, a colony of yeast cells

in which each cell divides into two cells every ten minutes

is growing exponentially,” the study explains. The model

used to capture the dynamic quality of exponential growth

is a System Dynamics model, developed over a 30-year pe-

riod at MIT, which recognizes that the structure of any

838

system determines its behavior as much as any individual

parts of the system. The components of a system are de-

scribed as “circular, interlocking, sometimes time-delayed.”

Using this model (called World3), the study ran scenarios—

what-if analyses—to reach its view of how the world will

evolve if present trends persist.

“Dynamic

modeling

theory indicates that any expo-

nentially growing quantity is somehow involved with a posi-

tive feedback loop,” the study points out. “In a positive

feedback loop a chain of cause-and-effect relationships closes

on itself, so that increasing any one element in the loop will

start a sequence of changes that will result in the originally

changed element being increased even more.”

In the case of world

population growth

, the births

per year act as a positive feedback loop. For instance, in

1650, world population was half a billion and was growing

at a rate of 0.3 percent a year. In 1970, world population

was 3.6 billion and was growing at a rate of 2.1 percent a

year. Both the population and the rate of population growth

have been increasing exponentially. But in addition to births

per year, the dynamic system of population growth includes

a negative feedback loop: deaths per year. Positive feedback

loops create runaway growth, while negative feedback loops

regulate growth and hold a system in a stable state. For

instance, a thermostat will regulate temperature when a room

reaches a certain temperature, the thermostat shuts off the

system until the temperature decreases enough to restart the

system. With population growth, both the birth and death

rates were relatively high and irregular before the Industrial

Revolution. But with the spread of medicines and longer

life expectancies, the death rate has slowed while the birth

rate has risen. Given these trends, the study predicted a

worldwide jump in population of seven billion over 30 years.

This same dynamic of positive and negative feedback

loops applies to the other components of the world system.

The growth in world industrial capital, with the positive

input of investment, creates rising industrial output, such as

houses, automobiles, textiles, consumer goods, and other

products. On the negative feedback side, depreciation, or

the capital discarded each year, draws down the level of

industrial capital. This feedback is “exactly analogous to the

death rate loop in the population system,” the study notes.

And, as with world population, the positive feedback loop

is “strongly dominant,” creating steady growth in worldwide

industrial capital and the use of raw materials needed to

create products.

This system in which exponential growth is occurring,

with positive feedback loops outstripping negative ones, will

push the world to the limits of exponential growth. The

study asks what will be needed to sustain world economic

and population growth until and beyond the year 2000 and

concludes that two main categories of ingredients can be

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Limnology

defined. First, there are physical necessities that support all

physiological and industrial activity: food, raw materials,

fossil and nuclear fuels, and the ecological systems of the

planet that absorb waste and recycle important chemical

substances.

Arable land

, fresh water, metals, forests, and

oceans are needed to obtain those necessities. Second, there

are social necessities needed to sustain growth, including

peace, social

stability

, education, employment, and steady

technological progress.

Even assuming that the best possible social conditions

exist for the promotion of growth, the earth is finite and

therefore continued exponential growth will reach the limits

of each physical necessity. For instance, about 1 acre (0.4

ha) of arable land is needed to grow enough food per person.

With that need for arable land, even if all the world’s arable

land were cultivated, current population growth rates will

still create a “desperate land shortage before the year 2000,”

the study concludes. The availability of fresh water is another

crucial limiting factor, the study points out. “There is an

upper limit to the fresh water

runoff

from the land areas

of the earth each year, and there is also an exponentially

increasing demand for that water.”

This same analysis is applied to

nonrenewable re-

sources

, such as metals,

coal

, iron, and other necessities

for industrial growth. World demand is rising steadily and

at some point demand for each nonrenewable resource will

exceed supply, even with

recycling

of these materials. For

instance, the study predicts that even if 100 percent recycling

of chromium from 1970 onward were possible, demand

would exceed supply in 235 years. Similarly, while it is not

known how much pollution the world can take before vital

natural processes are disrupted, the study cautions that the

danger of reaching those limits is especially great because

there is usually a long delay between the time a pollutant

is released and the time it begins to negatively affect the

environment

.

While the study foretells worldwide collapse if expo-

nential growth trends continue, it also argues that the neces-

sary steps to avert disaster are known and are well within

human capabilities. Current knowledge and resources could

guide the world to a sustainable equilibrium society provided

that a realistic, long-term goal and the will to achieve that

goal are pursued.

The sequel to the 1972 study, Beyond the Limits, was

not sponsored by the Club of Rome, but it is written by

three of the original authors. While the basic analytical

framework remains the same in the later work—drawing

upon the concepts of exponential growth and feedback loops

to describe the world system—its conclusions are more se-

vere. No longer does the world only face a potential of

“overshooting” its limits. “Human use of many essential

resources and generation of many kinds of pollutants have

839

already surpassed rates that are physically sustainable,” ac-

cording to the 1992 study. “Without significant reductions

in material and energy flows, there will be in the coming

decades an uncontrolled decline in per capita food output,

energy use, and industrial output.”

However, like its predecessor, the later study sounds

a note of hope, arguing that decline is not inevitable. To

avoid disaster requires comprehensive reforms in policies

and practices that perpetuate growth in material consump-

tion and population. It also requires a rapid, drastic jump

in the efficiency with which we use materials and energy.

Both the earlier and the later study were received with

great controversy. For instance, economists and industrialists

charged that the earlier study ignored the fact that technolog-

ical innovation could stretch the limits to growth through

greater efficiency and diminishing pollution levels. When the

sequel was published, some critics charged that the World3

model could have been refined to include more realistic

distinctions between nations and regions, rather than looking

at all trends on a world scale. For instance, different conti-

nents, rich and poor nations, North, South, and East, various

regions—all are different, but those differences are ignored

in the model, thereby making it unrealistic even though

modeling techniques have evolved significantly since World3

was first developed. See also Sustainable development

[David Clarke]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Meadows, D., et al. The Limits to Growth: A Report for The Club of Rome’s

Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972.

Meadows, D., D. L. Meadows, and J. Randers. Beyond the Limits: Confront-

ing Global Collapse, Envisioning a Sustainable Future. Post Mills, VT: Chel-

sea Green, 1992.

Limnology

Derived from the Greek word limne, meaning marsh or

pond, the term limnology was first used in reference to lakes

by F. A. Forel (1841–1912) in 1892 in a paper titled “Le

Le

´

man: Monographie Limnology,” a study of what we now

call Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Limnology, also known

as aquatic

ecology

, refers to the study of fresh water commu-

nities within continental boundaries. It can be subdivided

into the study of lentic (standing water habitats such as lakes,

ponds, bogs, swamps, and marshes) and lotic (running water

habitats such as rivers, streams, and brooks) environments.

Collectively, limnologists study the morphological, physical,

chemical, and biological aspects of these habitats.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Raymond L. Lindeman

Raymond L. Lindeman (1915 – 1942)

American ecologist

Few scholars or scientists, even those much published and

long-lived, leave singular, indelible imprints on their disci-

plines,. Yet, Raymond Lindeman, in 26 short years, who

published just six articles, was described shortly after his

death by G. E. Hutchinson as “one of the most creative and

generous minds yet to devote itself to ecological science,”

and the last of those six papers, “The Trophic-Dynamic

Aspect of Ecology,"—published posthumously in 1942—

continues to be considered one of the foundational papers

in

ecology

, an article “path-breaking in its general analysis

of ecological

succession

in terms of

energy flow

through

the ecosystem,” an article based on an idea that Edward

Kormondy has called “the most significant formulation in

the development of modern ecology.”

Immediately after completing his doctorate at the Uni-

versity of Minnesota, Lindeman accepted a one-year Sterling

fellowship at Yale University to work with G. Evelyn Hutch-

inson, the Dean of American limnologists. He had published

chapters of his thesis one by one and at Yale worked to

revise the final chapter, refining it with ideas drawn from

Hutchinson’s lecture notes and from their discussions about

the ecology of lakes. Lindeman submitted the manuscript

to Ecology with Hutchinson’s blessings, but it was rejected

based on reviewers’ claims that it was speculation far beyond

the data presented from research on three lakes, including

Lindeman’s own doctoral research on Cedar Bog Lake. After

input from several well-known ecologists, further revisions,

and with further urging from Hutchinson, the editor finally

overrode the reviewers’ comments and accepted the manu-

script; it was published in the October, 1942 issue of Ecology,

a few months after Lindeman died in June of that year.

The important advances made by Lindeman’s seminal

article included his use of the

ecosystem

concept, which

he was convinced was “of fundamental importance in inter-

preting the data of dynamic ecology,” and his explication

of the idea that “all function, and indeed all life” within

ecosystems depends on the movement of energy through

such systems by way of trophic relationships. His use of

ecosystem went beyond the little attention paid to it by

Hutchinson and beyond Tansley’s labeling of the unit seven

years earlier to open up “new directions for the analysis of

the functioning of ecosystems.” More than half a century

after Lindeman’s article, and despite recent revelations on

the uncertainty and unpredictability of natural systems, a

majority of ecologists probably still accept ecosystem as the

basic unit in ecology and, in those systems, energy exchange

as the basic process.

Lindeman was able to effectively demonstrate a way

to bring together or synthesize two quite separate traditions

840

in ecology,

autecology

, dependent on physiological studies

of individual organisms and

species

, and synecology focused

on studies of communities, aggregates of individuals. He

believed, and demonstrated, that ecological research would

benefit from a synthesis of these organism-based approaches

and focus on the energy relationships that tied organism and

environment

into one unit—the ecosystem—suggesting as

a result that biotic and abiotic could not realistically be

disengaged, especially in ecology.

Half a decade or so of work on cedar bog lakes, and

half a dozen articles would seem a thin stem on which to

base a legacy. But it really boils down to Lindeman’s synthesis

of that work in that one singular, seminal paper, in which

he created one of the significant stepping stones from a

mostly descriptive discipline toward a more sophisticated

and modern theoretical ecology.

[Gerald J. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Cook, Robert E. “Raymond Lindeman and the Trophic-Dynamic Concept

in Ecology.” Science 198, no. 4312 (October 1977): 22–26.

Lindsey, Alton A. “The Ecological Way.” Naturalist-Journal of the Natural

History Society of Minnesota 31 (Spring 1980): 1–6.

Reif, Charles B. “Memories of Raymond Laurel Lindeman.” The Bulletin

of the Ecological Society of America 67, no. 1 (March 1986): 20–25.

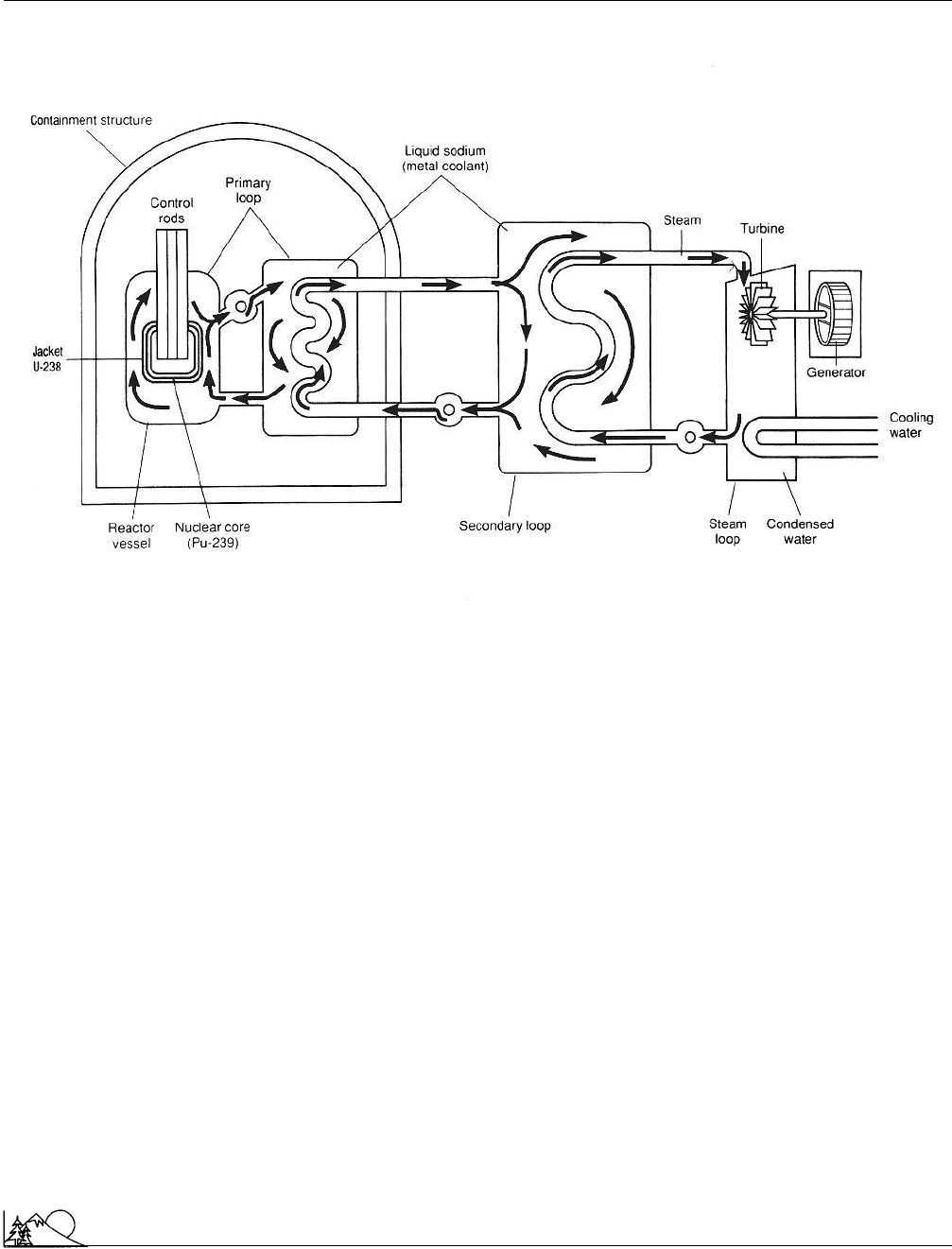

Liquid metal fast breeder reactor

The liquid metal fast breeder reactor (LMFBR) is a nuclear

reactor that has been modified to increase the efficiency at

which non-fissionable uranium-238 is converted to fission-

able plutonium-239, which can be used as fuel in the produc-

tion of

nuclear power

. The reactor uses “fast” rather than

“slow” neutrons to strike a uranium-238 nucleus, resulting in

the formation of plutonium-239. In a second modification, it

uses a liquid metal, usually sodium, rather than neutron-

absorbing water as a more efficient coolant. Since the reactor

produces new fuel as it operates, it is called a breeder reactor.

The main appeal of breeder reactors is that they pro-

vide an alternative way of obtaining fissionable materials.

The supply of natural

uranium

in the earth’s crust is fairly

large, but it will not last forever. Plutonium-239 from breeder

reactors might become the major fuel used in reactors built

a few hundred or thousand years from now.

However, the potential of LMFBRs has not as yet

been realized. One serious problem involves the use of liquid

sodium as coolant. Sodium is a highly corrosive metal and

in an LMFBR it is converted into a radioactive form, so-

dium-24. Accidental release of the coolant from such a plant

could, therefore, constitute a serious environmental hazard.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Liquified natural gas

Liquid metal fast breeder reactor. (McGraw-Hill Inc. Reproduced by permission.)

In addition,

plutonium

itself is difficult to work with. It is

one of the most toxic substances known to humans, and its

half-life

of 24,000 years means that its release presents long-

term environmental problems.

Small-scale pilot LMFBR reactors have been tested

in the United States, Saudi Arabia, Great Britain, and Ger-

many since 1966, and all have turned out to be far more

expensive than had been anticipated. The major United

States research program based at Clinch, Tennessee, began

in 1970. By 1983, the U. S. Congress refused to continue

funding the project due to its slow and unsatisfactory pro-

gress. See also Nuclear fission; Nuclear Regulatory Commis-

sion; Radioactivity; Radioactive waste management

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Cochran, Thomas B. The Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactor: An Environ-

mental and Economic Critique. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1974.

Mitchell III, W., and S. E. Turner. Breeder Reactors. Washington, DC:

U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1971.

841

O

THER

International Nuclear Information System. Links to Fast Reactor Related

Sites. June 7, 2002 [June 21, 2002]. <http://www.iaea.or.at/inis/ws/fnss/

fr.html>.

Liquified natural gas

Natural gas

is a highly desirable fuel in many respects. It

burns with the release of a large amount of energy, producing

almost entirely

carbon dioxide

and water as waste products.

Except for possible greenhouse effects of

carbon

dioxide,

these compounds produce virtually no environmental hazard.

Transporting natural gas through transcontinental pipelines

is inexpensive and efficient where

topography

allows the

laying of pipes. Oceanic shipping is difficult, however, be-

cause of the flammability of the gas and the high volumes

involved. The most common way of dealing with these prob-

lems is to condense the gas first and then transport it in the

form of liquified natural gas (LNG). But LNG must be

maintained at temperatures of about -260°F (-160°C) and

protected from leaks and flames during

loading

and un-

loading. See also Fossil fuels

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Lithology

Lithology

Lithology is the study of rocks, emphasizing their macro-

scopic physical characteristics, including grain size, mineral

composition, and color. Lithology and its related field, pe-

trography (the description and systematic classification of

rocks), are subdisciplines of petrology, which also considers

microscopic and chemical properties of minerals and rocks

as well as their origin and decay.

Littoral zone

In marine systems, littoral zone is synonymous with inter-

tidal zone and refers to the area on marine shores that is

periodically exposed to air during low tide. The freshwater

littoral zone is that area near the shore characterized by

submerged, floating, or emergent vegetation. The width of

a particular littoral zone may vary from several miles to a

few feet. These areas typically support an abundance of

organisms and are important feeding and nursery areas for

fishes, crustaceans, and birds. The distribution and abun-

dance of individual

species

in the littoral zone is dependent

on predation and

competition

as well as tolerance of physical

factors. See also Neritic zone; Pelagic zone

Loading

The term loading has a wide variety of specialized meanings

in various fields of science. In general, all refer to the addition

of something to a system, just as loading a truck means

filling it with objects. In the science of acoustics, for example,

loading refers to the process of adding materials to a speaker

in order to improve its acoustical qualities. In

environmen-

tal science

, loading is used to describe the contribution

made to any system by some component. One might analyze,

for example, how an increase in chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)

loading in the

stratosphere

might affect the concentration

of

ozone

there.

Logging

Logging is the systematic process of cutting down trees for

lumber and wood products. The method of logging called

clearcutting, in which entire areas of forests are cleared,

is the most prevalent practice used by lumber companies.

Clearcutting is the cheapest and most efficient way to harvest

a forest’s available resources. This practice drastically alters

the forest

ecosystem

, and many plants and animals are

displaced or destroyed by it. After clearcutting is performed

on forests, forestry management techniques may be intro-

842

duced in order to manage the growth of new trees on the

cleared land. Selective logging is an alternative to clear-

cutting. In selective logging, only certain trees in a forest

are chosen to be logged, usually on the basis of their size or

species

. By taking a smaller percentage of trees, the forest

is protected from destruction and fragile plants and animals

in the forest ecosystem are more likely to survive. New,

innovative techniques offer alternatives for preserving the

forest. For example, the Shelterwood Silvicultural System

harvests mature trees in phases. First, part of the original

stand is removed to promote growth of the remaining trees.

After this occurs, regeneration naturally follows using seeds

provided by the remaining trees. Once regeneration has oc-

curred, the remaining mature trees are harvested.

Early logging equipment included long, two-man

straight saws and teams of animals to drag trees away. After

World War II, technological advances made logging easier.

The bulldozer and the helicopter allowed loggers to enter

into new and previously untouched areas. The chainsaw

allowed loggers to cut down many more trees each day.

Today, enormous machines known as feller-bunchers take

the place of human loggers. These machines use a hydraulic

clamp that grasps the individual tree and huge shears that

cut through it in one swift motion.

High demands for lumber and forest products have

caused prolific and widespread commercial logging. Certain

methods of timber harvesting allow for subsequent regenera-

tion, while others cause

deforestation

, or the irreversible

creation of a non-forest condition. Deforestation signifi-

cantly changed the landscape of the United States. Some

observers remarked as early as the mid-1700s upon the rapid

changes made to the forests from the East Coast to the

Ohio River Valley. Often, the lumber in forests was burned

away so that the early settlers could build farms upon the

rich

soil

that had been created by the forest ecosystem.

The immediate results of deforestation are major changes

to Earth’s landscapes and diminishing

wildlife

habitats.

Longer-range results of deforestation, including unre-

strained commercial logging, may include damage to Earth’s

atmosphere

and the unbalancing of living ecosystems. For-

ests help to remove

carbon dioxide

from the air. Through

the process of

photosynthesis

, forests release oxygen into

the air. A single acre of temperate forest releases more than

six tons of oxygen into the atmosphere every year. In the

last 150 years, deforestation, together with the burning of

fossil fuels

, has raised the amount of

carbon

dioxide in

the atmosphere by more than 25%. It has been theorized

that this has contributed to global warming, which is the

accumulation of gasses leading to a gradual increase in

Earth’s surface temperature. Human beings are still learning

how to measure their need for wood against their need for

a viable

environment

for themselves and other life forms.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Logging

Although human activity, especially logging, has deci-

mated many of the world’s forests and the life within them,

some untouched forests still remain. These forests are known

as old-growth or ancient-growth forests. Old-growth forests

are at the center of a heated debate between environmental-

ists, who wish to preserve them, and the logging industry,

which continually seeks new and profitable sources of lumber

and other forest products.

Very little of the original uncut North American forest

still remains. It has been estimated that the United States has

lost over 96% of its old-growth forests. This loss continues as

logging companies become more attracted to ancient-growth

forests, which contain larger, more profitable trees. A major-

ity of old-growth forests in the United States are in Alaska

and Pacific Northwest. On the global level, barely 20% of

the old-growth forests still remain, and the South American

rainforests account for a significant portion of these. About

1% of the Amazon rainforest is deforested each year. At the

present rate of logging around the world, old-growth forests

could be gone within the first few decades of the twenty-

first century unless effective

conservation

programs are in-

stituted.

As technological advancements of the twentieth cen-

tury dramatically increased the efficiency of logging, there

was also a growth in understanding about the contribution

of the forest to the overall health of the environment, includ-

ing the effect of logging upon that health. Ecologists, who

are scientists that study the complex relationships within

natural systems, have determined that logging can affect the

health of air, soil, water, plant life, and animals. For instance,

clearcutting was at one time considered a healthy forestry

practice, as proponents claimed that clearing a forest enabled

the growth of new plant life, sped the process of regeneration,

and prevented fires. The American Forest Institute, an in-

dustry group, ran an ad in the 1970s that stated, “I’m clear-

cutting to save the forest.” Ecologists have come to under-

stand that clearcutting old-growth forests has a devastating

effect on plant and animal life, and affects the health of the

forest ecosystem from its rivers to its soil. Old-growth trees,

for example, provide an ecologically diverse

habitat

includ-

ing woody debris and

fungi

that contribute to nutrient-rich

soil. Furthermore, many species of plants and wildlife, some

still undiscovered, are dependent upon old-growth forests

for survival. The huge canopies created by old-growth trees

protect the ground from water

erosion

when it rains, and

their roots help to hold the soil together. This in turn main-

tains the health of rivers and streams, upon which fish and

other aquatic life depend. In the Pacific Northwest, for

example, ecologists have connected the health of the

salmon

population with the health of the forests and the logging

practices therein. Ecologists now understand that clear-

cutting and the planting of new trees, no matter how scientif-

843

ically managed, cannot replace the wealth of

biodiversity

maintained by old-growth forests.

The pace of logging is dictated by the consumer de-

mand for lumber and wood products. In the United States,

for instance, the average size of new homes doubled between

1970 and 2000, and the forests ultimately bear the burden

of the increasing consumption of lumber. In the face of

widespread logging, environmentalists have become more

desperate to protect ancient forests. There is a history of

controversy between the timber industry and environmental-

ists regarding the relationship between logging and the care

of forests. On the one hand, the logging industry has seen

forests as a source of wealth, economic growth, and jobs.

On the other hand, environmentalists have viewed these

same forests as a source of

recreation

, spiritual renewal, and

as living systems that maintain the overall

environmental

health

. In the 1980s, a controversy raged between environ-

mentalists and the logging industry over the protection of

the

northern spotted owl

, a threatened species of bird

whose habitat is the

old-growth forest

of the Pacific North-

west. Environmentalists appealed to the

Endangered Spe-

cies Act

of 1973 to protect some of these old-growth forests.

In other logging controversies, some environmentalists

chained themselves to old-growth trees to prevent their de-

struction, and one activist, Julia Butterfly Hill, lived in an

old-growth California redwood tree for two years in the

1990s to prevent it from being cut down. The clash between

environmentalists and the logging industry may become

more intense as the demand for wood increases and supplies

decrease. However, in recent years these opposing views have

been tempered by discussion of concepts such as responsible

forest management

to create sustainable growth, in combi-

nation with preservation of protected areas.

Most of the logging in the United States occurs in

the national forests. From the point of view of the U.S.

Forest Service

, logging provides jobs, helps manage the

forest in some respects, prevents logging in other parts of

the world, and helps eliminate the danger of forest fires. To

meet the demands of the logging industry, the national

forests have been developed with a labyrinth of logging

roads and contain vast areas that have been devastated by

clearcutting. In the United States there are enough logging

roads in the National Forests to circle the earth 15 times,

roads that speed up soil erosion that then washes away fertile

topsoil

and pollutes streams and rivers.

The Roadless Initiative was established in 2001 to

protect 60 million acres (24 million ha) of national forests.

The initiative was designed by the Clinton administration

to discourage logging and taxpayer-supported road building

on public lands. The goal was to establish total and perma-

nent protection for designated roadless areas. Advocates of

the initiative contended that roadless areas encompassed

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Logistic growth

some of the best wildlife habitats in the nation, while forest

service officials argued that banning road building would

significantly reduce logging in these areas. Under the initia-

tive, more than half of the 192 million acres (78 million ha)

of

national forest

would still remain available for logging

and other activities. This initiative was considered one of

the most important environmental protection measures of

the Clinton administration.

Illegal logging has become a problem with the growing

worldwide demand for lumber. For example, the

World

Bank

predicted that if Indonesia does not halt all current

logging, it would lose its entire forest within the next 10 to

15 years. Estimates indicate that up to 70% of the wood

harvested in Indonesia comes from illegal logging practices.

Much of the timber being taken is sent to the United States.

Indigenous peoples

of Indonesia are being displaced from

their traditional territories. Wildlife, including endangered

tigers

,

elephants

, rhinos, and orangutans are also being

displaced and may be threatened with

extinction

. In 2002

Indonesia placed a temporary moratorium on logging in an

effort to stop illegal logging.

Other countries around the world were addressing

logging issues in the early twenty-first century. In China,

160 million acres (65 million ha) out of 618 million acres

(250 million ha) were put under state protection. Loggers

turned in their tools to become forest rangers, working for

the government in order to safeguard trees from illegal log-

ging. China has set aside millions of acres of forests for

protection, particularly those forests that are crucial sources

of fresh water. China also announced that it was planning

to further reduce its timber output in order to restore and

enhance the life-sustaining abilities of its forests.

[Douglas Dupler]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dietrich, William.The Final Forest: The Battle for the Last Great Trees of

the Pacific Northwest. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Durbin, Kathie.Tree Huggers: Victory, Defeat and Renewal in the Northwest

Ancient Forest Campaign. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers, 1996.

Hill, Julia Butterfly. The Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman,

and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods. San Francisco: Harper, 2000.

Luoma, Jon R. The Hidden Forest. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1999.

Nelson, Sharlene P., and Ted Nelson. Bull Whackers to Whistle Punks:

Logging in the Old West. New York: Watts, 1996.

P

ERIODICALS

Alcock, James. “Amazon Forest Could Disappear, Soon.” Science News,

July 14, 2001.

De Jong, Mike. “Optimism Over Lumber.” Maclean’s, November 29,

2001, 16.

Kerasote, Ted. “The Future of our Forests.” Audubon, January/February

2001, 44.

844

Murphy, Dan. “The Rise of Robber Barons Speeds Forest Decline.” Chris-

tian Science Monitor, August 14, 2001, 8.

O

THER

American Lands Home Page. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.americanlan-

ds.org>.

Global Forest Watch Home Page. [cited July 2002]. <http://www.globalforest-

watch.org>.

SmartWood Program of the Rainforest Alliance. [cited July 2002]. <http://

www.smartwood.org>.

Logistic growth

Assuming the rate of immigration is the same as emigration,

population size increases when births exceed deaths. As pop-

ulation size increases, population density increases, and the

supply of limited available resources per organism decreases.

There is thus less food and less space available for each

individual. As food, water, and space decline, fewer births

or more deaths may occur, and this imbalance continues

until the number of births are equal to the number of deaths

at a population size that can be sustained by the available

resources. This equilibrium level is called the

carrying ca-

pacity

for that

environment

.

A temporary and rapid increase in population may be

due to a period of optimum growth conditions including

physical and biological factors. Such an increase may push

a population beyond the environmental carrying capacity.

This sudden burst will be followed by a decline, and the

population will maintain a steady fluctuation around the

carrying capacity. Other population controls, such as preda-

tors and weather extremes (

drought

, frost, and floods), keep

populations below the carrying capacity. Some environmen-

talists believe that the human population has exceeded the

earth’s carrying capacity.

Logistic growth, then, refers to growth rates that are

regulated by internal and external factors that establish an

equilibrium with

environmental resources

. The sigmoid

(idealized S-shaped) curve illustrates this logistic growth

where environmental factors limit

population growth

.In

this model, a low-density population begins to grow slowly,

then goes through an exponential or geometric phase, and

then levels off at the environmental carrying capacity. See also

Exponential growth; Growth limiting factors; Sustainable

development; Zero population growth

[Muthena Naseri]

Dr. Bjørn Lomborg (1965 – )

Danish political scientist

In 2001, Cambridge University Press published The Skeptical

Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World by

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Bjørn Lomborg

the Danish statistician Bjørn Lomborg. The book triggered

a firestorm of criticism, with many well-known scientists

denouncing it as an effort to “confuse legislators and regula-

tors, and poison the well of public environmental informa-

tion.” In January 2002, Scientific American published a series

of articles by five distinguished environmental scientists con-

testing Lomborg’s claims. To some observers, the ferocity

of the attack was surprising. Why so much furor over a book

that claims to have good news about our environmental

condition?

Lomborg portrays himself as an “left-wing, vegetarian,

Greenpeace

member,” but says he worries about the unre-

lenting “doom and gloom” of mainstream

environmen-

talism

. He describes what he regards as an all-pervasive

ideology that says, among other things, “Our resources are

running out. The population is ever growing, leaving less

and less to eat. The air and water are becoming ever more

polluted. The planet’s

species

are becoming extinct in vast

numbers. The forests are disappearing, fish stocks are col-

lapsing, and coral reefs are dying.” This ideology has per-

vaded the environmental debate so long, Lomborg says, “that

blatantly false claims can be made again and again, without

any references, and yet still be believed.”

In fact, Lomborg tells us, these allegations of the col-

lapse of ecosystems are “simply not in keeping with reality.

We are not running out of energy or

natural resources

.

There will be more and more food per head of the world’s

population. Fewer and fewer people are starving. In 1900

we lived for an average of 30 years; today we live 67. Ac-

cording to the UN we have reduced poverty more in the

last 50 years than in the preceding 500, and it has been

reduced in practically every country.” He goes on to challenge

conventional scientific assessment of global warming, forest

losses, fresh water

scarcity

, energy shortages, and a host of

other environmental problems. Is Lomborg being deliber-

ately (and some would say, hypocritically) optimistic, or are

others being unreasonably pessimistic? Is this simply a case

of regarding the glass as half full versus half empty?

The inspiration to look at environmental

statistics

,

Lomborg says, was a 1997 interview with the controversial

economist Dr. Julian L. Simon in Wired magazine. Simon,

who died in 1998, spent a good share of his career arguing

that the “litany” of the Green movement—human overpopu-

lation leading to starvation and resource shortages—was pre-

meditated hyperbole and fear mongering. The truth, Simon,

claimed is that the quality of human life is improving, not

declining.

Lomborg felt sure that Simon’s allegations were “sim-

ple American right-wing propaganda.” It should be a simple

matter, he thought, to gather evidence to show how wrong

Simon was. Back at his university in Denmark, Lomborg

set out with 10 of his sharpest students to study Simon’s

845

claims. To their surprise, the group found that while not

everything Simon said was correct, his basic conclusions

seemed sound. When Lomborg began to publish these find-

ings in a series of newspaper articles in the London Guardian

in 1998, he stirred up a hornet’s nest. Some of his colleagues

at the University of Aarhus set up a website to denounce

the work. When the whole book came out, their fury only

escalated. Altogether, between 1998 and 2002, more than

400 articles appeared in newspapers and popular magazines

either attacking or defending Lomborg and his conclusions.

In general, the debate divides between mostly conser-

vative supporters on one side and progressive, environmental

activists and scientists on the other. The Wall Street Journal

described the Skeptical Environmentalist as “superbly docu-

mented and readable.” The Economist called it “a triumph.”

A review in the Daily Telegraph (London) declared it “the

most important book on the

environment

ever written.” A

review in the Washington Post said it is a “richly informative,

lucid book, a magnificent achievement.” And, The Economist,

which started the debate by publishing his first articles,

announced that, “this is one of the most valuable books on

public policy—not merely on environmental policy—to have

been written in the past ten years.”

Among most environmentalists and scientists, on the

other hand, Lomborg has become an anathema. A widely

circulated list of “Ten things you should know about the

Skeptical Environmentalist” charged that the book is full of

pseudo-scholarship, statistical fallacies, distorted quotations,

inaccurate or misleading citations, misuse of data, interpreta-

tions that contradict well-established scientific work, and

many other serious errors. This list accuses Lomborg of

having no professional credentials or training—and having

done no professional research—in

ecology

,

climate

science,

resource economic,

environmental policy

, or other fields

covered by his book. In essence, they complain, “Who is

this guy, and how dare he say all this terrible stuff?”

Harvard University Professor

E. O. Wilson

, one of the

world’s most distinguished biologists, deplores what he calls

“the Lomborg scam,” and says that he and his kind “are the

parasite load on scholars who earn success through the slow

process of peer review and approval.” It often seems that

more scorn and hatred is focused on those, like Lomborg,

who are viewed as a turncoats and heretics, than for those

who are actually out despoiling the environment and squan-

dering resources.

Perhaps the most withering criticism of Lomborg

comes from his reporting of statistics and research results.

Stephen Schneider, a distinguished climate scientist from

Stanford University, for instance, writes in Scientific American

“most of [Lomborg’s] nearly 3,000 citations are to secondary

literature and media articles. Moreover, even when cited,

the peer-reviewed articles come elliptically from those studies

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Dr. Bjørn Lomborg

that support his rosy view that only the low end of the

uncertainty ranges [of climate change] will be plausible.

IPCC authors, in contrast, were subjected to three rounds

of review by hundreds of outside experts. They didn’t have

the luxury of reporting primarily from the part of the com-

munity that agrees with their individual views.”

Lomborg also criticizes

extinction

rate estimates as

much too large, citing evidence from places like Brazil’s

Atlantic Forest, where about 90% of the forest has been

cleared without large numbers of recorded extinctions.

Thomas Lovejoy, chief

biodiversity

adviser to the

World

Bank

, responds, “First, this is a region with very few field

biologists to record either species or their extinction. Second,

there is abundant evidence that if the Atlantic forest remains

as reduced and fragmented as it is, will lose a sizable fraction

of the species that at the moment are able to hang on.”

Part of the problem is that Lomborg is unabashedly

anthropocentric. He dismisses the value of biodiversity, for

example. As long as there are plants and animals to supply

human needs, what does it matter if a few non-essential

species go extinct? In Lomborg’s opinion, poverty, hunger,

and human health problems are much more important prob-

lems than

endangered species

or possible climate change.

He isn’t opposed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, for

instance, but argues that rather than spend billions of dollars

per year to try to meet Kyoto standards, we could provide

a healthy diet, clean water, and basic medical services to

everyone in the world, thereby saving far more lives than we

might do by reducing global climate change. Furthermore,

Lomborg believes,

solar energy

will probably replace

fossil

fuels

within 50 years anyway, making worries about increas-

ing CO

2

concentrations moot.

Lomborg infuriates many environmentalists by being

intentionally optimistic, cheerfully predicting that progress

in population control, use of

renewable energy

, and un-

limited water supplies from desalination technology will

spread to the whole world, thus avoiding crises in resource

supplies and human impacts on our environment. Others,

particularly Lester Brown of the

Worldwatch Institute

and

Professor Paul Ehrlich of Stanford University, according to

Lomborg, seem to deliberately adopt worst-case scenarios.

Protagonists on both sides of this debate use statistics

selectively and engage in deliberate exaggeration to make

their points. As Stephen Schneider, one of the most promi-

nent anti-Lomborgians, said in an interview in Discover in

1989, “[We] are not just scientists but human beings as well.

And like most people we’d like to see the world a better

place. To do that we need to get some broad-based support,

to capture the public’s imagination. That, of course, entails

getting loads of media coverage. So we have to offer up scary

scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements, and make

little mention of any doubts we might have. Each of us has

846

to decide what the right balance is between being effective

and being honest.”

As is often the case in complex social issues, there are

both truth and error on both sides in this debate. It takes

good critical thinking skills to make sense out of the flurry

of charges and counter charges. In the end, what you believe

depends on your perspective and your values. Future events

will show us whether Bjørn Lomborg or his critics are correct

in their interpretations and predictions. In the meantime,

it’s probably healthy to have the vigorous debate engendered

by strongly held beliefs and articulate partisans from many

different perspectives.

In November 2001, Lomborg was selected Global

Leader for Tomorrow by the World Economic Forum, and

in February 2002, he was named director of Denmark’s

national Environmental Assessment Institute. In addition to

the use of statistics in environmental issues, his professional

interests are simulation of strategies in collective action di-

lemmas, simulation of party behavior in proportional voting

systems, and use of surveys in public administration.

[William Cunningham Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Lomborg, Bjorn. The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State

of the World. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

Bell, Richard C. “Media Sheep: How did The Skeptical Environmentalist

Pull the Wool over the Eyes of so Many Editors?” Worldwatch 15, no. 2

(2002): 11–13.

Dutton, Denis. “Greener than you think.” Washington Post, October 21,

2001.

Schneider, Stephen. “Global Warming: Neglecting the Complexities.” Sci-

entific American 286 (2002): 62–65.

Wade, Nicholas. “Bjørn Lomborg: A Chipper Environmentalist.” The New

York Times, August 7, 2001.

O

THER

Anti-Lomborgian Web Site. December 2001 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://

www.anti-lomborg.com>.

Bjørn Lomborg Home Page. 2002 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.lomb-

org.com>.

Regis, Ed. “The Doomslayer: The environment is going to hell, and human

life is doomed to only get worse, right? Wrong. Conventional wisdom,

meet Julian Simon, the Doomslayer.” February 1997. Wired. [cited July 9,

2002]. <http://www.wired.com>.

Wilson, E. O. “Vanishing Point: On Bjørn Lomborg and Extinction.” Grist

December 12, 2001 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.gristmagazine.com/

books/wilson121201.asp>.

World Resources Institute and World Wildlife Fund. Ten Things Environ-

mental Educators Should Know About The Skeptical Environmentalist. January

2002 [cited July 9, 2002]. <http://www.wri.org/press/

mk_lomborg_10_things.html>.