Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey

humans and was, along with an erect posture, one of the

chief characteristics used to differentiate humans from non-

humans. Scientists at the time, however, did not consider

East Africa a likely site for finding evidence of early humans;

the discovery of Pithecanthropus in Java in 1894 (the so-

called Java Man, now considered to be an example of Homo

erectus) had led scientists to assume that Asia was the conti-

nent from which human forms had spread.

Shortly after the end of World War I, Leakey was

sent to a public school in Weymouth, England, and later

attended St. John’s College, Cambridge. Suffering from se-

vere headaches resulting from a sports injury, he took a year

off from his studies and joined a fossil-hunting expedition

to Tanganyika (now Tanzania). This experience, combined

with his studies in anthropology at Cambridge (culminating

in a degree in 1926), led Leakey to devote his time to the

search for the origins of humanity, which he believed would

be found in Africa. Anatomist and anthropologist Raymond

A. Dart’s discovery of early human remains in South Africa

was the first concrete evidence that this view was correct.

Leakey’s next expedition was to northwest Kenya, near Lakes

Nakuru and Naivasha, where he uncovered materials from

the Late Stone Age; at Kariandusi he discovered a 200,000-

year-old hand ax.

In 1928 Leakey married Henrietta Wilfrida Avern,

with whom he had two children: Priscilla, born in 1930,

and Colin, born in 1933; the couple was divorced in the

mid-1930s. In 1931 Leakey made his first trip to Olduvai

Gorge—a 350-mi (564-km) ravine in Tanzania—the site

that was to be his richest source of human remains. He had

been discouraged from excavating at Olduvai by Hans Reck,

a German paleontologist who had fruitlessly sought evidence

of prehistoric humans there. Leakey’s first discoveries at

that site consisted of both animal fossils, important in the

attempts to date the particular stratum (or layer of earth) in

which they were found, and, significantly, flint tools. These

tools, dated to approximately one million years ago, were

conclusive evidence of the presence of hominids—a family

of erect primate mammals that use only two feet for locomo-

tion—in Africa at that early date; it was not until 1959,

however, that the first fossilized hominid remains were

found there.

In 1932, near Lake Victoria, Leakey found remains

of Homo sapiens (modern man), the so-called Kanjera skulls

(dated to 100,000 years ago) and Kanam jaw (dated to

500,000 years ago); Leakey’s claims for the antiquity of this

jaw made it a controversial find among other paleontologists,

and Leakey hoped he would find other, independent, evi-

dence for the existence of Homo sapiens from an even earlier

period—the Lower Pleistocene.

In the mid-1930s, a short time after his divorce from

Wilfrida, Leakey married his second wife, Mary Douglas

827

Nicol; she was to make some of the most significant discover-

ies of Leakey’s team’s research. The couple eventually had

three children: Philip, Jonathan, and Richard E. Leakey.

During the 1930s, Leakey also became interested in the

study of the Paleolithic period in Britain, both regarding

human remains and geology, and he and Mary Leakey car-

ried out excavations at Clacton in southeast England.

Until the end of the 1930s, Leakey concentrated on

the discovery of stone tools as evidence of human habitation;

after this period he devoted more time to the unearthing of

human and prehuman fossils. His expeditions to Rusinga

Island, at the mouth of the Kavirondo Gulf in Kenya, during

the 1930s and early 1940s produced a large number of finds,

especially of remains of Miocene apes. One of these apes,

which Leakey named Proconsul africanus, had a jaw lacking

in the so-called simian shelf that normally characterized the

jaws of apes; this was evidence that Proconsul represented a

stage in the progression from ancient apes to humans. In

1948 Mary Leakey found a nearly complete Proconsul skull,

the first fossil ape skull ever unearthed; this was followed

by the unearthing of several more Proconsul remains.

Louis Leakey began his first regular excavations at

Olduvai Gorge in 1952; however, the Mau Mau (an anti-

white secret society) uprising in Kenya in the early 1950s

disrupted his paleontological work and induced him to write

Mau Mau and the Kikuyu, in an effort to explain the rebellion

from the perspective of a European with an insider’s knowl-

edge of the Kikuyu. A second work, Defeating Mau Mau,

followed in 1954.

During the late 1950s, the Leakeys continued their

work at Olduvai. In 1959, while Louis was recuperating

from an illness, Mary Leakey found substantial fragments

of a hominid skull that resembled the robust australopithe-

cines—African hominids possessing small brains and near-

human dentition—found in South Africa earlier in the cen-

tury. Louis Leakey, who quickly reported the find to the

journal Nature, suggested that this represented a new genus,

which he named Zinjanthropus boisei, the genus name mean-

ing “East African man,” and the

species

name commemo-

rating Charles Boise, one of Leakey’s benefactors. This spe-

cies, now called Australopithecus boisei, was later believed by

Leakey to have been an evolutionary dead end, existing

contemporaneously with Homo rather than representing an

earlier developmental stage.

In 1961, at Fort Ternan, Leakey’s team located frag-

ments of a jaw that Leakey believed were from a hitherto

unknown genus and species of ape, one he designated as

Kenyapithecus wickeri, and which he believed was a link be-

tween ancient apes and humans, dating from 14 million

years ago; it therefore represented the earliest hominid. In

1967, however, an older skull, one that had been found two

decades earlier on Rusinga Island and which Leakey had

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey

Louis Leakey. (The Library of Congress.)

originally given the name Ramapithecus africanus, was found

to have hominid-like lower dentition; he renamed it Kenya-

pithecus africanus, and Leakey believed it was an even earlier

hominid than Kenyapithecus wickeri. Leakey’s theories about

the place of these Lower Miocene fossil apes in human

evolution

have been among his most widely disputed.

During the early 1960s, a member of Leakey’s team

found fragments of the hand, foot, and leg bones of two

individuals, in a site near where Zinjanthropus had been

found, but in a slightly lower and, apparently, slightly older

layer. These bones appeared to be of a creature more like

modern humans than Zinjanthropus, possibly a species of

Homo that lived at approximately the same time, with a

larger brain and the ability to walk fully upright. As a result

of the newly developed potassium-argon dating method, it

was discovered that the bed from which these bones had

come was 1.75 million years old. The bones were, apparently,

the evidence for which Leakey had been searching for years:

skeletal remains of Homo from the Lower Pleistocene. Lea-

key designated the creature whose remains these were as

Homo habilis ("man with ability"), a creature who walked

upright and had dentition resembling that of modern hu-

mans, hands capable of toolmaking, and a large cranial capac-

ity. Leakey saw this hominid as a direct ancestor of Homo

erectus and modern humans. Not unexpectedly, Leakey was

attacked by other scholars, as this identification of the frag-

828

ments moved the origins of the genus Homo back substan-

tially further in time. Some scholars felt that the new remains

were those of australopithecines, if relatively advanced ones,

rather than very early examples of Homo.

Health problems during the 1960s curtailed Leakey’s

field work; it was at this time that his Centre for Prehistory

and Paleontology in Nairobi became the springboard for the

careers of such paleontologists as

Jane Goodall

and Dian

Fossey in the study of nonhuman primates. A request came

in 1964 from the Israeli government for assistance with the

technical as well as the fundraising aspects involved in the

excavation of an early Pleistocene site at Ubeidiya. This

produced evidence of human habitation dating back 700,000

years, the earliest such find outside Africa.

During the 1960s, others, including Mary Leakey and

the Leakeys’ son Richard, made significant finds in East

Africa; Leakey turned his attention to the investigation of

a problem that had intrigued him since his college days:

the determination of when humans had reached the North

American continent. Concentrating his investigation in the

Calico Hills in the Mojave

Desert

, California, he sought

evidence in the form of stone tools of the presence of early

humans, as he had done in East Africa. The discovery of

some pieces of chalcedony (translucent quartz) that resem-

bled manufactured tools in

sediment

dated from 50,000 to

100,000 years old stirred an immediate controversy; at that

time, scientists believed that humans had settled in North

America approximately 20,000 years ago. Many archaeolo-

gists, including Mary Leakey, criticized Leakey’s California

methodology—and his interpretations of the finds—as sci-

entifically unsound, but Leakey, still charismatic and persua-

sive, was successful in obtaining funding from the National

Geographic Society and, later, several other sources. Human

remains were not found in conjunction with the supposed

stone tools, and many scientists have not accepted these

“artifacts” as anything other than rocks.

Shortly before Louis Leakey’s death, Richard Leakey

showed his father a skull he had recently found near Lake

Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in Kenya. This skull, removed

from a deposit dated to 2.9 million years ago, had a cranial

capacity of approximately 800 cubic centimeters, putting it

within the range of Homo and apparently vindicating Lea-

key’s long-held belief in the extreme antiquity of that genus;

it also appeared to substantiate Leakey’s interpretation of

the Kanam jaw. Leakey died of a heart attack in early Octo-

ber, 1972, in London.

Some scientists have questioned Leakey’s interpreta-

tions of his discoveries. Other scholars have pointed out that

two of the most important finds associated with him were

actually made by Mary Leakey, but became widely known

when they were interpreted and publicized by him; Leakey

had even encouraged criticism through his tendency to publi-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey

cize his somewhat sensationalistic theories before they had

been sufficiently tested. Critics have cited both his tendency

toward hyperbole and his penchant for claiming that his

finds were the “oldest,” the “first,” the “most significant"; in

a 1965 National Geographic article, for example, Melvin M.

Payne pointed out that Leakey, at a Washington, D.C.,

press conference, claimed that his discovery of Homo habilis

had made all previous scholarship on early humans obsolete.

Leakey has also been criticized for his eagerness to create

new genera and species for new finds, rather than trying to

fit them into existing categories. Leakey, however, recog-

nized the value of publicity for the fundraising efforts neces-

sary for his expeditions. He was known as an ambitious man,

with a penchant for stubbornly adhering to his interpreta-

tions, and he used the force of his personality to communi-

cate his various finds and the subsequent theories he devised

to scholars and the general public.

Leakey’s response to criticism was that scientists have

trouble divesting themselves of their own theories in the

light of new evidence. “Theories on prehistory and early

man constantly change as new evidence comes to light,”

Leakey remarked, as quoted by Payne in National Geographic.

“A single find such as Homo habilis can upset long-held—

and reluctantly discarded—concepts. A paucity of human

fossil material and the necessity for filling in blank spaces

extending through hundreds of thousands of years all con-

tribute to a divergence of interpretations. But this is all we

have to work with; we must make the best of it within the

limited range of our present knowledge and experience.”

Much of the controversy derives from the lack of consensus

among scientists about what defines “human"; to what extent

are toolmaking, dentition, cranial capacity, and an upright

posture defining characteristics, as Leakey asserted?

Louis Leakey’s significance revolves around the ways

in which he changed views of early human development.

He pushed back the date when the first humans appeared

to a time earlier than had been believed on the basis of

previous research. He showed that human evolution began

in Africa rather than Asia, as had been maintained. In addi-

tion, he created research facilities in Africa and stimulated

explorations in related fields, such as primatology (the study

of primates). His work is notable as well for the sheer number

of finds—not only of the remains of apes and humans, but

also of the plant and animal species that comprised the

ecosystems in which they lived. These finds of Leakey and

his team filled numerous gaps in scientific knowledge of the

evolution of human forms. They provided clues to the links

between prehuman, apelike primates, and early humans, and

demonstrated that human evolution may have followed more

than one parallel path, one of which led to modern humans,

rather than a single line, as earlier scientists had maintained.

[Michael Sims]

829

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Cole, S. Leakey’s Luck: The Life of Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey, 1903–1972.

Harcourt, 1975.

Isaac, G., and E. R. McCown, eds., Human Origins: Louis Leakey and the

East African Evidence. Benjamin-Cummings, 1976.

Johanson, D. C., and M. A. Edey. Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind.

Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Leakey, M. Disclosing the Past. Doubleday, 1984.

Leakey, R. One Life: An Autobiography. Salem House, 1984.

Malatesta, A., and R. Friedland, The White Kikuyu: Louis S. B. Leakey.

McGraw-Hill, 1978.

Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey (1913 –

1996)

English paleontologist and anthropologist

For many years Mary Leakey lived in the shadow of her

husband, Louis Leakey, whose reputation, coupled with the

prejudices of the time, led him to be credited with some of

his wife’s discoveries in the field of early human archaeology.

Yet she has established a substantial reputation in her own

right and has come to be recognized as one of the most

important paleoanthropologists of the twentieth century. It

was Mary Leakey who was responsible for some of the

most important discoveries made by Louis Leakey’s team.

Although her close association with Louis Leakey’s work

on Paleolithic sites at Olduvai Gorge—a 350-mi (564-km)

ravine in Tanzania—has led to her being considered a spe-

cialist in that particular area and period, she has in fact

worked on excavations dating from as early as the Miocene

Age (an era dating to approximately 18 million years ago)

to those as recent as the Iron Age of a few thousand years ago.

Mary Leakey was born Mary Douglas Nicol on Febru-

ary 6, 1913, in London. Her mother was Cecilia Frere,

the great-granddaughter of John Frere, who had discovered

prehistoric stone tools at Hoxne, Suffolk, England, in 1797.

Her father was Erskine Nicol, a painter who himself was

the son of an artist, and who had a deep interest in Egyptian

archaeology. When Mary was a child, her family made fre-

quent trips to southwestern France, where her father took

her to see the Upper Paleolithic cave paintings. She and her

father became friends with Elie Peyrony, the curator of the

local museum, and there she was exposed to the vast collec-

tion of flint tools dating from that period of human prehis-

tory. She was also allowed to accompany Peyrony on his

excavations, though the archaeological work was not con-

ducted in what would now be considered a scientific way—

artifacts were removed from the site without careful study of

the place in the earth where each had been found, obscuring

valuable data that could be used in dating the artifact and

analyzing its context. On a later trip, in 1925, she was taken

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey

to Paleolithic caves by the Abbe Lemozi of France, parish

priest of Cabrerets, who had written papers on cave art.

After her father’s death in 1926, Mary Nicol was taken to

Stonehenge and Avebury in England, where she began to

learn about the archaeological activity in that country and,

after meeting the archaeologist Dorothy Liddell, to realize

the possibility of archaeology as a career for a woman.

By 1930 Mary Nicol had undertaken coursework in

geology and archaeology at the University of London and

had participated in a few excavations in order to obtain field

experience. One of her lecturers, R. E. M. Wheeler, offered

her the opportunity to join his party excavating St. Albans,

England, the ancient Roman site of Verulamium; although

she only remained at that site for a few days, finding the

work there poorly organized, she began her career in earnest

shortly thereafter, excavating Neolithic (early Stone Age)

sites in Henbury, Devon, where she worked between 1930

and 1934. Her main area of expertise was stone tools, and

she was exceptionally skilled at making drawings of them.

During the 1930s Mary met Louis Leakey, who was to

become her husband. Leakey was by this time well known

because of his finds of early human remains in East Africa;

it was at Mary and Louis’s first meeting that he asked her

to help him with the illustrations for his 1934 book, Adam’s

Ancestors: An Up-to-Date Outline of What Is Known about

the Origin of Man.

In 1934 Mary Nicol and Louis Leakey worked at

an excavation in Clacton, England, where the skull of a

hominid—a family of erect primate mammals that use only

two feet for locomotion—had recently been found and where

Louis was investigating Paleolithic geology as well as

fauna

and human remains. The excavation led to Mary Leakey’s

first publication, a 1937 report in the Proceedings of the Prehis-

toric Society.

By this time, Louis Leakey had decided that Mary

should join him on his next expedition to Olduvai Gorge

in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), which he believed to be the

most promising site for discovering early Paleolithic human

remains. On the journey to Olduvai, Mary stopped briefly

in South Africa, where she spent a few weeks with an archae-

ological team and learned more about the scientific approach

to excavation, studying each find in situ—paying close atten-

tion to the details of the geological and faunal material

surrounding each artifact. This knowledge was to assist her

in her later work at Olduvai and elsewhere.

At Olduvai, among her earliest discoveries were frag-

ments of a human skull; these were some of the first such

remains found at the site, and it would be twenty years

before any others would be found there. Mary Nicol and

Louis Leakey returned to England. Leakey’s divorce from

his first wife was made final in the mid-1930s, and he and

Mary Nicol were then married; the couple returned to Kenya

830

in January of 1937. Over the next few years, the Leakeys

excavated Neolithic and Iron Age sites at Hyrax Hill, Njoro

River Cave, and the Naivasha Railway Rock Shelter, which

yielded a large number of human remains and artifacts.

During World War II, the Leakeys began to excavate

at Olorgasailie, southwest of Nairobi, but because of the

complicated geology of that site, the dating of material found

there was difficult. It did prove to be a rich source of material,

however; in 1942 Mary Leakey uncovered hundreds, possibly

thousands, of hand axes there. Her first major discovery in

the field of prehuman fossils was that of most of the skull

of a Proconsul africanus on Rusinga Island, in Lake Victoria,

Kenya, in 1948. Proconsul was believed by some paleontolo-

gists to be a common ancestor of apes and humans, an

animal whose descendants developed into two branches on

the evolutionary tree: the Pongidae (great apes) and the Hom-

inidae (who eventually evolved into true humans). Proconsul

lived during the Miocene Age, approximately 18 million

years ago. This was the first time a fossil ape skull had ever

been found—only a small number have been found since—

and the Leakeys hoped that this would be the ancestral

hominid that paleontologists had sought for decades. The

absence of a “simian shelf,” a reinforcement of the jaw found

in modern apes, is one of the features of Proconsul that led

the Leakeys to infer that this was a direct ancestor of modern

humans. Proconsul is now generally believed to be a

species

of Dryopithecus, closer to apes than to humans.

Many of the finds at Olduvai were primitive stone

hand axes, evidence of human habitation; it was not known,

however, who had made them. Mary’s concentration had

been on the discovery of such tools, while Louis’s goal had

been to learn who had made them, in the hope that the date

for the appearance of toolmaking hominids could be moved

back to an earlier point. In 1959 Mary unearthed part of

the jaw of an early hominid she designated Zinjanthropus

(meaning “East African Man") and whom she referred to

as “Dear Boy"; the early hominid is now considered to be

a species of Australopithecus—apparently related to the two

kinds of australopithecine found in South Africa, Australopi-

thecus africanus and Australopithecus robustus— and given the

species designation boisei in honor of Louis Leakey’s sponsor

Charles Boise. By means of potassium-argon dating, recently

developed, it was determined that the fragment was 1.75

million years old, and this realization pushed back the date

for the appearance of hominids in Africa. Despite the impor-

tance of this find, however, Louis Leakey was slightly disap-

pointed, as he had hoped that the excavations would unearth

not another australopithecine, but an example of Homo living

at that early date. He was seeking evidence for his theory

that more than one hominid form lived at Olduvai at the

same time; these forms were the australopithecines, who

eventually died out, and some early form of Homo, which

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Richard Erskine Frere Leakey

survived—owing to toolmaking ability and larger cranial

capacity—to evolve into Homo erectus and, eventually, the

modern human. Leakey hoped that Mary Leakey’s find

would prove that Homo existed at that early level of Olduvai.

The discovery he awaited did not come until the early 1960s,

with the identification of a skull found by their son Jonathan

Leakey that Louis designated as Homohabilis ("man with

ability"). He believed this to be the true early human respon-

sible for making the tools found at the site.

In her autobiography, Disclosing the Past, released in

1984, Mary Leakey reveals that her professional and personal

relationship with Louis Leakey had begun to deteriorate by

1968. As she increasingly began to lead the Olduvai research

on her own, and as she developed a reputation in her own

right through her numerous publications of research results,

she believes that her husband began to feel threatened. Louis

Leakey had been spending a vast amount of his time in

fundraising and administrative matters, while Mary was able

to concentrate on field work. As Louis began to seek recogni-

tion in new areas, most notably in excavations seeking evi-

dence of early humans in California, Mary stepped up her

work at Olduvai, and the breach between them widened.

She became critical of his interpretations of his California

finds, viewing them as evidence of a decline in his scientific

rigor. During these years at Olduvai, Mary made numerous

new discoveries, including the first Homo erectus pelvis to be

found. Mary Leakey continued her work after Louis Leakey’s

death in 1972. From 1975 she concentrated on Laetoli,

Tanzania, which was a site earlier than the oldest beds at

Olduvai. She knew that the lava above the Laetoli beds was

dated to 2.4 million years ago, and the beds themselves were

therefore even older; in contrast, the oldest beds at Olduvai

were two million years old. Potassium-argon dating has since

shown the upper beds at Laetoli to be approximately 3.5

million years old. In 1978 members of her team found two

trails of hominid footprints in volcanic ash dated to approxi-

mately 3.5 million years ago; the form of the footprints gave

evidence that these hominids walked upright, thus moving

the date for the development of an upright posture back

significantly earlier than previously believed. Mary Leakey

considers these footprints to be among the most significant

finds with which she has been associated.

In the late 1960s Mary Leakey received an honorary

doctorate from the University of the Witwatersrand in South

Africa, an honor she accepted only after university officials

had spoken out against apartheid. Among her other honorary

degrees are a D.S.Sc. from Yale University and a D.Sc. from

the University of Chicago. She received an honorary D.Litt.

from Oxford University in 1981. She has also received the

Gold Medal of the Society of Women Geographers.

Louis Leakey was sometimes faulted for being too

quick to interpret the finds of his team and for his propensity

831

for developing sensationalistic, publicity-attracting theories.

In recent years Mary Leakey had been critical of the conclu-

sions reached by her husband—as well as by some others—

but she did not add her own interpretations to the mix.

Instead, she has always been more concerned with the act

of discovery itself; she wrote that it is more important for

her to continue the task of uncovering early human remains

to provide the pieces of the puzzle than it is to speculate

and develop her own interpretations. Her legacy lies in the

vast amount of material she and her team have unearthed;

she leaves it to future scholars to deduce its meaning.

[Michael Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Isaac, G., and E. R. McCown, eds. Human Origins: Louis Leakey and the

East African Evidence. Benjamin-Cummings, 1976.

Reader, J. Missing Links. Little, Brown, 1981.

Moore, R. E., Man, Time, and Fossils: The Story of Evolution. Knopf, 1961.

Malatesta, A., and R. Friedland, The White Kikuyu: Louis S. B. Leakey.

McGraw-Hill, 1978.

Leakey, R. One Life: An Autobiography. Salem House, 1984.

Johanson, D. C., and M. A. Edey, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind.

Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Cole, S. Leakey’s Luck: The Life of Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey, 1903–1972.

Harcourt, 1975.

Leakey, L. By the Evidence: Memoirs, 1932–1951. Harcourt, 1974.

Richard Erskine Frere Leakey (1944 – )

African-born English paleontologist and anthropologist

Richard Erskine Frere Leakey was born on December 19,

1944, in Nairobi, Kenya. Continuing the work of his parents,

Leakey has pushed the date for the appearance of the first

true humans back even further than they had, to nearly three

million years ago. This represents nearly a doubling of the

previous estimates. Leakey also has found more evidence to

support his father’s still controversial theory that there were

at least two parallel branches of human

evolution

, of which

only one was successful. The abundance of human fossils

uncovered by Richard Leakey’s team has provided an enor-

mous number of clues as to how the various fossil remains

fit into the puzzle of human evolution. The team’s finds

have also helped to answer, if only speculatively, some basic

questions: When did modern human’s ancestors split off

from the ancient apes? On what continent did this take

place? At what point did they develop the characteristics

now considered as defining human attributes? What is the

relationship among and the chronology of the various genera

and

species

of the fossil remains that have been found?

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Richard Erskine Frere Leakey

While accompanying his parents on an excavation at

Kanjera near Lake Victoria at the age of six, Richard Leakey

made his first discovery of fossilized animal remains, part

of an extinct variety of giant pig. Richard Leakey, however,

was determined not to “ride upon his parents’ shoulders,”

as Mary Leakey wrote in her autobiography, Disclosing the

Past. Several years later, as a young teenager in the early

1960s, Richard demonstrated a talent for

trapping wildlife

,

which prompted him to drop out of high school to lead

photographic safaris in Kenya. His paleontological career

began in 1963, when he led a team of paleontologists to a

fossil-bearing area near Lake Natron in Tanganyika (now

Tanzania), a site that was later dated to approximately 1.4

million years ago. A member of the team discovered the jaw

of an early hominid—a member of the family of erect primate

mammals that use only two feet for locomotion—called an

Australopithecus boisei (then named Zinjanthropus).) This was

the first discovery of a complete Australopithecus lower jaw

and the only Australopithecus skull fragment found since

Mary Leakey’s landmark discovery in 1959. Jaws provide

essential clues about the nature of a hominid, both in terms

of its structural similarity to other species and, if teeth are

present, its diet. Richard Leakey spent the next few years

occupied with more excavations, the most important result of

which was the discovery of a nearly complete fossil elephant.

In 1964 Richard married Margaret Cropper, who had

been a member of his father’s team at Olduvai the year

before. It was at this time that he became associated with

his father’s Centre for Prehistory and Paleontology in Nai-

robi. In 1968, at the age of 23, he became administrative

director of the National Museum of Kenya.

While his parents had mined with great success the

fossil-rich Olduvai Gorge, Richard Leakey concentrated his

efforts in northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia. In 1967

he served as the leader of an expedition to the Omo Delta

area of southern Ethiopia, a trip financed by the National

Geographic Society. In a site dated to approximately 150,000

years ago, members of his team located portions of two

fossilized human skulls believed to be from examples of

Homo sapiens, or modern humans. While the prevailing view

at the time was that Homo sapiens emerged around 60,000

years ago, these skulls were dated at 130,000 years old.

While on an airplane trip, Richard Leakey flew over

the eastern portion of Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) on

the Ethiopia-Kenya border, and he noticed from the air

what appeared to be ancient lake sediments, a kind of terrain

that he felt looked promising as an excavation site. He used

his next National Geographic Society grant to explore this

area. The region was Koobi Fora, a site that was to become

Richard Leakey’s most important area for excavation. At

Koobi Fora his team uncovered more than four hundred

hominid fossils and an abundance of stone tools, such tools

832

being a primary indication of the presence of early humans.

Subsequent excavations near the Omo River in Kenya, from

1968, unearthed more examples of early humans, the first

found being another Australopithecus lower jaw fragment. At

the area of Koobi Fora known as the KBS tuff (tuff being

volcanic ash; KBS standing for the Kay Behrensmeyer Site,

after a member of the team) stone tools were found. Prelimi-

nary dating of the site placed the area at 2.6 million years ago;

subsequent tests over the following few years determined the

now generally accepted age of 1.89 million years.

In July of 1969, Richard Leakey came across a virtually

complete Australopithecus boisei skull—lacking only the teeth

and lower jaw—lying in a river bed. A few days later a

member of the team located another hominid skull nearby,

comprising the back and base of the cranium. The following

year brought the discovery of many more fossil hominid

remains, at the rate of nearly two per week. Among the

most important finds was the first hominid femur to be

found in Kenya, which was soon followed by several more.

It was at about this time that Leakey obtained a divorce

from his first wife, and in October of 1970, he married

Meave Gillian Epps, who had been on the 1969 expedition.

In 1972, Richard Leakey’s team uncovered a skull that

appeared to be similar to the one identified by his father

and called Homo habilis ("man with ability"). This was the

early human that Louis Leakey maintained had achieved

the toolmaking skills that precipitated the development of

a larger brain capacity and led to the development of the

modern human—Homo sapiens. This skull was more com-

plete and apparently somewhat older than the one Louis

Leakey had found and was thus the earliest example of the

species Homo yet discovered. They labeled the new skull,

which was found below the KBS tuff, “Skull 1470,” and

this proved to among Richard Leakey’s most significant

discoveries. The fragments consisted of small pieces of all

sides of the cranium, and, unusually, the facial bones, enough

to permit a reasonably complete reconstruction. Larger than

the skulls found in 1969 and 1970, this example had approxi-

mately twice the cranial capacity of Australopithecus and more

than half that of a modern human—nearly 800 cubic centi-

meters. At the time, Leakey believed the fragments to be

2.9 million years old (although a more recent dating of the

site would place them at less than 2 million years old). Basing

his theory in part on these data, Leakey developed the view

that these early hominids may have lived as early as 2.5 or

even 3.5 million years ago and gave evidence to the theory

that Homo habilis was not a descendant of the australopithe-

cines, but a contemporary.

By the late 1960s, relations between Richard Leakey

and his father had become strained, partly because of real

or imagined competition within the administrative structure

of the Centre for Prehistory, and partly because of some

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Leaking underground storage tank

divergences in methodology and interpretation. Shortly be-

fore Louis Leakey’s death, however, the discovery of Skull

1470 by Richard Leakey’s team allowed Richard to present

his father with apparent corroboration of one of his central

theories.

Richard Leakey did not make his theories of human

evolution public until 1974. At this time, scientists were still

grappling with Louis Leakey’s interpretation of his findings

that there had been at least two parallel lines of human

evolution, only one of which led to modern humans. After

Louis Leakey’s death, Richard Leakey reported that, based

on new finds, he believed that hominids diversified between

3 and 3.5 million years ago. Various lines of australopithe-

cines and Homo coexisted, with only one line, Homo, surviv-

ing. The australopithecines and Homo shared a common

ancestor; Australopithecus was not ancestral to Homo. As did

his father, Leakey believes that Homo developed in Africa,

and it was Homo erectus who, approximately 1.5 million years

ago, developed the technological capacity to begin the spread

of humans beyond their African origins. In Richard Leakey’s

scheme, Homo habilis developed into Homo erectus, who in

turn developed into Homo sapiens, the present-day human.

As new finds are made, new questions arise. Are newly

discovered variants proof of a plurality of species, or do they

give evidence of greater variety within the species that have

already been identified? To what extent is sexual dimorphism

responsible for the apparent differences in the fossils? In

some scientific circles, the discovery of fossil remains at

Hadar in Ethiopia by archaeologist Donald Carl Johanson

and others, along with the more recent revised dating of

Skull 1470, cast some doubt on Leakey’s theory in general

and on his interpretation of Homo habilis in particular. Johan-

son believed that the fossils he found at Hadar and the fossils

Mary Leakey found at Laetoli in Tanzania, and which she

classified as Homo habilis, were actually all australopithecines;

he termed them Australopithecus afarensis and claimed that

this species is the common ancestor of both the later australo-

pithecines and Homo. Richard Leakey has rejected this argu-

ment, contending that the australopithecines were not ances-

tral to Homo and that an earlier common ancestor would be

found, possibly among the fossils found by Mary Leakey at

Laetoli.

The year 1975 brought another significant find by

Leakey’s team at Koobi Fora: the team found what was

apparently the skull of a Homo erectus, according to Louis

Leakey’s theory a descendent of Homo habilis and probably

dating to 1.5 million years ago. This skull, labeled “3733,”

represents the earliest known evidence for Homo erectus in

Africa.

Richard Leakey began to suffer from health problems

during the 1970s, and in 1979 he was diagnosed with a

serious kidney malfunction. Later that year he underwent a

833

kidney transplant operation, his younger brother Philip being

the donor. During his recuperation Richard completed his

autobiography, One Life, which was released in 1984, and

following his recovery, he renewed his search for the origins

of the human species. The summer of 1984 brought another

major discovery: the so-called Turkana boy, a nearly com-

plete skeleton of a Homo erectus, missing little but the hands

and feet, and offering, for the first time, the opportunity to

view many bones of this species. It was shortly after the

unearthing of Turkana boy—whose skeletal remains indicate

that he was a twelve-year-old youngster who stood approxi-

mately five-and-a-half feet tall—that the puzzle of human

evolution became even more complicated. The discovery of

a new skull, called the Black Skull, with an Australopithecus

boisei face but a cranium that was quite apelike, introduced

yet another complication, possibly a fourth branch in the

evolutionary tree. Leakey became the Director of the Wild-

life

Conservation

and Management Department for Kenya

(Kenya Wildlife Service) in 1989 and in 1999 became head

of the Kenyan civil service.

[Michael Sims]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Leakey, M. Disclosing the Past: An Autobiography. Doubleday, 1984.

Leakey, R., and R. Lewin. Origins Reconsidered: In Search of What Makes

Us Human. Doubleday, 1992.

Reader, J. Missing Links. Little, Brown, 1981.

Leaking underground storage tank

Leaking underground storage tanks (LUST) that hold toxic

substances have come under new regulatory scrutiny in the

United States because of the health and environmental haz-

ards posed by the materials that can leak from them. These

storage tanks typically hold

petroleum

products and other

toxic

chemicals

beneath gas stations and other petroleum

facilities. An estimated 63,000 of the nation’s underground

storage tanks have been shown to leak contaminants into

the

environment

or are considered to have the potential to

leak at any time. One reason for the instability of under-

ground storage tanks is their construction. Only five percent

of underground storage tanks are made of corrosion-pro-

tected steel, while 84 percent are made of bare steel, which

corrodes easily. Another 11 percent of underground storage

tanks are made of fiberglass.

Hazardous materials seeping from some of the nation’s

six million LUSTs can contaminate aquifers, the water-

bearing rock units that supply much of the earth’s drinking

water. An

aquifer

, once contaminated, can be ruined as a

source of fresh water. In particular,

benzene

has been found

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Aldo Leopold

to be a contaminant of

groundwater

as a result of leaks

from underground

gasoline

storage tanks. Benzene and

other volatile organic compounds have been detected in bot-

tled water despite manufacturers’ claims of purity.

According to the

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA), more than 30 states reported groundwater contami-

nation from petroleum products leaking from underground

storage tanks. States also reported water contamination from

radioactive waste leaching

from storage containment

facilities. Other reported

pollution

problems include leaking

hazardous substances that are corrosive, explosive, readily

flammable, or chemically reactive. While

water pollution

may be the most visible consequence of leaks from under-

ground storage tanks, fires and explosions are dangerous and

sometimes real possibilities in some areas.

The EPA is charged with exploring, developing, and

disseminating technologies and funding mechanisms for

cleanup. The primary job itself, however, is left to state and

local governments. Actual cleanup is sometimes funded by

the Leaking Underground Storage Tank trust fund estab-

lished by Congress in 1986. Under the Superfund Amend-

ment and Reauthorization Act, owners and operators of

underground storage tanks are required to take corrective

action to prevent leakage. See also Comprehensive Environ-

mental Response, Compensation and Liability Act; Ground-

water monitoring; Groundwater pollution; Storage and

transport of hazardous materials; Toxic Substances Con-

trol Act

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Epstein, L., and K. Stein. Leaking Underground Storage Tanks—Citizen

Action: An Ounce of Prevention. New York: Environmental Information

Exchange (Environmental Defense Fund), 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Breen, B. “A Mountain and a Mission.” Garbage 4 (May-June 1992): 52–57.

Hoffman, R. D. R. “Stopping the Peril of Leaking Tanks.” Popular Science

238 (March 1991): 77–80.

O

THER

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Underground Storage Tanks

(OUST). June 13, 2002 [June 21, 2002]. <http://www.epa.gov/swerust1>.

Aldo Leopold (1886 – 1978)

American conservationist, ecologist, and writer

Leopold was a noted forester, game manager, conservation-

ist, college professor, and ecologist. Yet he is known world-

wide for A Sand County Almanac, a little book considered

an important, influential work to

conservation

movement

834

of the twentieth century. In it, Leopold established the

land

ethic

, guidelines for respecting the land and preserving its

integrity. Leopold grew up in Iowa, in a house overlooking

the Mississippi River, where he learned

hunting

from his

father and an appreciation of

nature

from his mother. He

received a master’s degree in forestry from Yale and spent his

formative professional years working for the United States

Forest Service

in the American Southwest.

In the Southwest, Leopold began slowly to consider

preservation as a supplement to Gifford Pinchot’s “conserva-

tion as wise use—greatest good for the greatest number”

land management philosophy that he learned at Yale and

in the Forest Service. He began to formulate arguments

for the preservation of

wilderness

and the

sustainable

development

of wild game. Formerly a hunter who encour-

aged the elimination of predators to save the “good” animals

for hunters, Leopold became a conservationist who remem-

bered with sadness the “dying fire” in the eyes of a wolf he

had killed. In the Journal of Forestry, he began to speculate

that perhaps Pinchot’s principle of highest use itself de-

manded “that representative portions of some forests be

preserved as wilderness.”

Leopold must be recognized as one of a handful of

originators of the wilderness idea in American conservation

history. He was instrumental in the founding of the

Wilder-

ness Society

in 1935, which he described in the first issue

of Living Wilderness as “one of the focal points of a new

attitude—an intelligent humility toward man’s place in na-

ture.” In a 1941 issue of that same journal, he asserted that

wilderness also has critical practical uses “as a base-datum

of normality, a picture of how healthy land maintains itself,”

and that wilderness was needed as a living “land laboratory.”

This thinking led to the first large area designated as

wilderness in the United States. In 1924, some 574,000 acres

(232,000 ha) of the Gila

National Forest

in New Mexico

was officially named a wilderness area. Four years before,

the much smaller Trappers Lake valley in Colorado was the

first area designated “to be kept roadless and undeveloped.”

Aldo Leopold is also widely acknowledged as the

founder of

wildlife management

in the United States. His

classic text on the subject, Game Management (1933), is still

in print and widely read. Leopold tried to write a general

management framework, drawing upon and synthesizing

species

monographs and local manuals. “Details apply to

game alone, but the principles are of general import to all

fields of conservation,” he wrote. He wanted to coordinate

“science and use” in his book and felt strongly that land

managers could either try to apply such principles, or be

reduced to “hunting rabbits.” Here can be found early uses

of concepts still central to conservation and management,

such as limiting factor,

niche

, saturation point, and

carrying

capacity

. Leopold later became the first professor of game

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Aldo Leopold

management in the United States at the University of Wis-

consin.

Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949,

a year after his death, is often described as “the bible of the

environmental movement” of the second half of the twenti-

eth century. The Almanac is a beautifully written source

of solid ecological concepts such as trophic linkages and

biological community

. The book extends basic ecological

concepts, forming radical ideas to reformulate human think-

ing and behavior. It exhibits an ecological conscience, a

conservation aesthetic, and a land ethic. He advocated his

concept of ecological conscience to fill in a perceived gap

in conservation education: “Obligations have no meaning

without conscience, and the problem we face is the extension

of the social conscience from people to land.” Lesser known

is his attention to the aesthetics of land: according to the

Almanac, an acceptable land aesthetic emerges only from

learned and sensitive perception of the connections and

needs of natural communities. The last words in the Almanac

are that a true conservation aesthetic is developed “not of

building roads into lovely country, but of building receptivity

into the still unlovely human mind.”

Leopold derived his now famous land ethic from an

ecological conception of community. All ethics, he main-

tained, “rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a

member of a community of interdependent parts.” He argued

that “the land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the

community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals,

or collectively: the land.” Perhaps the most widely quoted

statement from the book argues that “a thing is right when

it tends to preserve the integrity,

stability

, and beauty of

the

biotic community

. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Leopold’s land ethic was first proposed in the Journal

of Forestry article in 1933 and later expanded in the Almanac.

It is a plea to care for land and its biological complex, instead

of considering it a commodity. As Wallace Tegner noted,

Leopold’s ideas were heretical in 1949, and to some people

still are. “They smack of socialism and the public good,” he

wrote. “They impose limits and restraints. They are anti-

Progress. They dampen American initiative. They fly in the

face of the faith that land is a commodity, the very foundation

stone of American opportunity.” As a result, Stegner and

others do not think Leopold’s ethic had much influence

on public thought, though the book has been widely read.

Leopold recognized this. “The case for a land ethic would

appear hopeless but for the minority which is in obvious

revolt against these ’modern’ trends,” he commented. Never-

theless, the land ethic is alive and still flourishing, in an

ever-growing minority. Even Stegner argued that “Leopold’s

land ethic is not a fact but [an on-going] task.” Leopold did

not shrink from that task, being actively involved in many

835

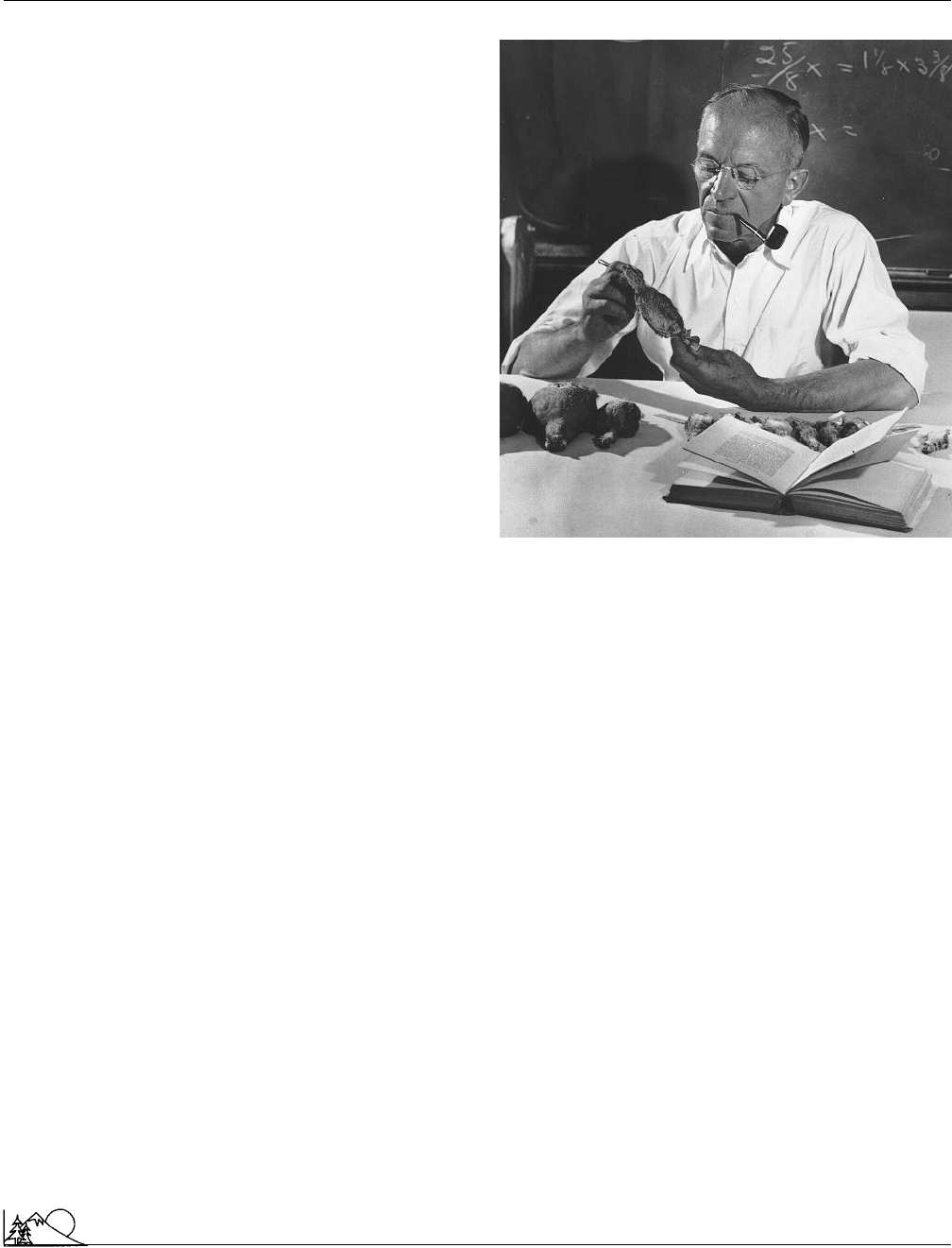

Aldo Leopold examining a gray partridge. (Pho-

tograph by Robert Oetking. University of Wisconsin-Madi-

son Archives. Reproduced by permission.)

conservation associations, teaching management principles

and the land ethic to his classes, bringing up all five of his

children to become conservationists, and applying his beliefs

directly to his own land, a parcel of “logged, fire-swept,

overgrazed, barren” land in Sauk County, Wisconsin. As his

work has become more recognized and more influential,

many labels have been applied to Leopold by contemporary

writers. He is a “prophet” and “intellectual touchstone” to

Roderick Nash a “founding genius” to J. Baird Callicott

“an American Isaiah” to Stegner the “Moses of the new

conservation impulse” to Donald Fleming. In a sense, he

may have been all of these, but more than anything else,

Leopold was an applied ecologist who tried to put into

practice the principles he learned from the land.

[Gerald R. Young Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Callicott, J. B., ed. Companion to A Sand County Almanac: Interpretive and

Critical Essays. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

Flader, S. L., and J. B. Callicott, eds. The River of the Mother of God and

Other Essays by Aldo Leopold. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Less developed countries

Fritzell, P. A. “A Sand County Almanac and The Conflicts of Ecological

Conscience.” In Nature Writing and America: Essays Upon a Cultural Type.

Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1990.

Leopold, A. Game Management. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933.

———. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press, 1949.

Meine, C. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Madison: University of Wiscon-

sin Press, 1988.

Oelschlaeger, M. “Aldo Leopold and the Age of Ecology.” In The Idea of

Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press, 1991.

Strong, D. H. “Aldo Leopold.” In Dreamers and Defenders: American Conser-

vationists. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

Less developed countries

Less developed countries (LDCs) have lower levels of eco-

nomic prosperity, health care, and education than most other

countries. Development or improvement in economic and

social conditions encompasses various aspects of general wel-

fare, including infant survival, expected life span, nutrition,

literacy rates, employment, and access to material goods.

Less developed countries (LDCs) are identified by their

relatively poor ratings in these categories. In addition, most

LDCs are marked by high

population growth

, rapidly

expanding cities, low levels of technological development,

and weak economies dominated by agriculture and the export

of

natural resources

. Because of their limited economic

and technological development, LDCs tend to have rela-

tively little international political power compared to more

developed countries (MDC) such as Japan, the United

States, and Germany.

A variety of standard measures, or development indi-

ces, are used to assess development stages. These indices are

generalized statistical measures of quality of life for individu-

als in a society. Multiple indices are usually considered more

accurate than a single number such as Gross National Prod-

uct, because such figures tend to give imprecise and simplistic

impressions of conditions in a country. One of the most

important of the multiple indices is the infant

mortality

rate.

Because children under five years old are highly susceptible to

common diseases, especially when they are malnourished,

infant mortality is a key to assessing both nutrition and

access to health care. Expected life span, the average age

adults are able to reach, is used as a measure of adult health.

Daily calorie and protein intake per person are collective

measures that reflect the ability of individuals to grow and

function effectively. Literacy rates, especially among women,

who are normally the last to receive an education, indicate

access to schools and preparation for technologically ad-

vanced employment.

Fertility rates are a measure of the number of children

produced per family or per woman in a population and are

regarded as an important measure of the confidence parents

836

have in their childrens’ survival. High birth rates are associ-

ated with unstable social conditions because a country with

a rapidly growing population often cannot provide its citizens

with food, water,

sanitation

, housing space, jobs, and other

basic needs. Rapidly growing populations also tend to un-

dergo rapid urbanization. People move to cities in search of

jobs and educational opportunities, but in poor countries

the cost of providing basic infrastructure in an expanding

city can be debilitating. As most countries develop, they pass

from a stage of high birth rates to one of low birth rates, as

child survival becomes more certain and a family’s investment

in educating and providing for each child increases.

Most LDCs were colonies under foreign control dur-

ing the past 200 years. Colonial powers tended to undermine

social organization, local economies, and natural resource

bases, and many recently independent states are still recov-

ering from this legacy. Thus, much of Africa, which provided

a wealth of natural resources to Europe between the seven-

teenth and twentieth centuries, now lacks the effective and

equitable social organization necessary for continuing devel-

opment. Similarly, much of Central America (colonized by

Spain in the fifteenth century) and portions of South and

Southeast Asia (colonized by England, France, the Nether-

lands, and others) remain less developed despite their wealth

of natural resources. The development processes necessary

to improve standards of living in LDCs may involve more

natural resource extraction, but usually the most important

steps involve carefully choosing the goods to be produced,

decreasing corruption among government and business lead-

ers, and easing the social unrest and conflicts that prevent

development from proceeding. All of these are extraordi-

narily difficult to do, but they are essential for countries

trying to escape from poverty. See also Child survival revolu-

tion; Debt for nature swap; Economic growth and the envi-

ronment; Indigenous peoples; Shanty towns; South; Sustain-

able development; Third World; Third World pollution;

Tropical rain forest; World Bank

[Muthena Naseri]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Gill, S., and D. Law. The Global Political Economy. Baltimore: Johns Hop-

kins University Press, 1991.

World Bank. World Development Report: Development and the Environment.

Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1992.

World Bank. World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty. Ox-

ford, England: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Leukemia

Leukemia is a disease of the blood-forming organs. Primary

tumors are found in the bone marrow and lymphoid tissues,