Jan Lindhe. Clinical Periodontology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE USE OF ANTISEPTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY •

465

feature of periodontal disease management for almost

a century (for reviews see Fischman 1992, 1997). The

consensus appears to be that the use of preventive

agents should be as adjuncts and not replacements for

the more conventional and accepted effective me-

chanical methods and only then when these appear

partially or totally ineffective alone.

Mechanical tooth cleaning through toothbrushing

with toothpaste is arguably the most common and

potentially effective form of oral hygiene practiced by

peoples in developed countries (for reviews see

Frandsen 1986, Jepsen 1998); although,

per capita in

the

world, wood sticks are probably more commonly

used.

Interdental cleaning is a secondary adjunct and

would

seem particularly important in individuals who,

through the presence of disease, can be

retrospectively assessed as susceptible (for reviews

see Hancock 1996, World Workshop on Periodontics

1996a, Kinane 1998). Unfortunately, it is a fact of life

that a significant proportion of all individuals fail to

practice a high enough standard of plaque removal

such that gingivitis is highly prevalent and from an

early age (Laystedt et al. 1982, Addy et al. 1986). This,

presumably, arises either or both from a failure to

comply with the recommendation to regularly clean

teeth or lack of dexterity with tooth cleaning habits (

Frandsen 1986). Certainly, many individuals remove

only around half of the plaque from their teeth even

when brushing for 2 minutes (de la Rosa 1979). Pre-

sumably this occurs because certain tooth surfaces

receive little or no attention during the brushing cycle

(

Rugg-Gunn & MacGregor 1978, MacGregor & Rugg-

Gunn 1979). The adjunctive use of chemicals would

therefore appear a way of overcoming deficiencies in

mechanical tooth cleaning habits as practiced by

many individuals. This chapter will consider the past

and present status and success of chemical suprag-

ingival plaque control to the prevention of gingivitis

and thereby periodontitis. Since chemical agents are

usually considered as adjuncts, some aspects of me-

chanical plaque control will be considered.

Supragingival plaque control

The formation of plaque on a tooth surface is a dy-

namic and ordered process, commencing with the

attachment of primary plaque forming bacteria. The

attachment of these organisms appears essential for

initiating the sequence of attachment of other organ-

isms such that, with time, the mass and complexity of

the plaque increases (see Chapter 3). Left undisturbed,

supragingival plaque reaches a quantitative and

qualitative level of bacterial complexity that is incom-

patible with gingival health, and gingitivis ensues.

Even though, as yet, the microbiology of gingivitis is

poorly understood, the sequencing of plaque forma-

tion highlights how interventions may prevent the

development of gingivitis. Thus, any method of

plaque

control which prevents plaque achieving the

critical point where gingival health deteriorates, will

stop gingivitis. Unfortunately, the lack of knowledge

of bacterial specificity for gingivitis does not allow

targeting of the control of particular organisms except

for perhaps the primary plaque formers. Plaque inhi-

bition has, therefore, targeted plaque formation at

particular points – bacterial attachment, bacterial pro

-

liferation and plaque maturation – and these will be

discussed in more detail in the later section "Ap-

proaches to chemical supragingival plaque control".

The mainstay of supragingival plaque control has

been regular plaque removal using mechanical meth-

ods which, in developed countries, means the tooth-

brush, manual or electric, and in less well developed

countries the use of wood or chewing sticks (for re-

view see Frandsen 1986, Hancock 1996). These devices

primarily access smooth surface plaque and not inter

-

dental deposits. Interdental cleaning devices include

wood sticks, floss, tape, interdental brushes and, more

recently, electric interdental devices (for review see

Egelberg & Claffey 1998, Kinane 1998). Regular me-

chanical tooth cleaning is directed towards maintain-

ing a level of plaque, quantitatively and/or qualita-

tively, which is compatible with gingival health, and

not rendering the tooth surface bacteria free. Theoreti

-

cally, mechanical cleaning of teeth could prevent car-

ies but workshops have concluded that tooth brush-

ing

per se

and interdental cleaning as performed by the

individual do not prevent caries (for review see Frand-

sen 1986). Clearly, but outside the scope of this chapter,

the toothbrush and other mechanical devices do pro-

vide a vehicle whereby anticaries agents, such as fluo

-

ride, can be delivered to the tooth surface. Under the

conditions of clinical experimentation, tooth cleaning

performed once every two days was shown to prevent

gingivitis (Lang et al. 1973, Kelner et al. 1974, McNabb

et al. 1992). However, the professional recommenda-

tion has been to brush twice per day, for which there

is evidence of a benefit to gingival health over less

frequent cleaning with no additional benefit for more

frequent brushing (for review see Frandsen 1986). The

duration of brushing is somewhat controversial given

that most surveys or studies reveal average brushing

time of 60 s or less (Rugg-Gunn & MacGregor 1978,

MacGregor & Rugg-Gunn 1979). However, it is worth

noting that one study showed less than 50% plaque

removal after 2 minutes brushing (de la Rosa 1979).

This perhaps highlights that many individuals spend

little or no time during the brushing cycle at some

tooth surfaces, notably lingually (Rugg-Gunn &

MacGregor 1978, MacGregor & Rugg-Gunn 1979).

Oral hygiene, oral hygiene instruction and the ef-

fect of supragingival plaque control alone on sub-

gingival plaque and therefore periodontal disease are

the subject of other chapters. Nevertheless, some fur-

ther comments on mechanical tooth cleaning are per-

tinent in this chapter, particularly in respect of com-

parative efficacy of devices. The manual toothbrush

as known today – man-made filaments in a plastic

head –was invented as recently as the 1920s. Evidence

466 • CHAPTER 22

for such devices dates back to China approximately

1000 years ago, re-emerging in the 1800s in Europe,

but too expensive for common usage (for reviews see

Fischman 1992, 1997). Numerous changes in manual

toothbrush design have occurred, particularly re-

cently, and similarly numerous claims have been

made for the efficacy of individual designs. Despite

this, researchers, workshop reports and consensus

views have repeatedly concluded that there is no best

design of manual toothbrush nor an optimal method

of tooth cleaning, the major variable being the person

using the brush (for reviews see Frandsen 1986, Jepsen

1998). Limited evidence is available comparing the

modern toothbrush with chewing sticks but what is

available suggests similar efficacy (Norton & Addy

1989), perhaps not surprisingly if indeed the user is

the important factor. Interdental cleaning is consid-

ered important particularly for those individuals who

are known to be susceptible to or have periodontal

disease (for reviews see Egelberg & Claffey 1998, Ki-

nane 1998,). Here again, there is little evidence sup-

porting one interdental cleaning method over another,

leaving patients and professionals to hold subjectively

related preferences (for review see Kinane 1998). Elec

-

tric toothbrushes of the counter rotation type found

prominence for a short time in the 1960s and 1970s

but

were unreliable and proven of no greater efficacy

over

manual brushes, except for handicapped

individuals

(for reviews see Frandsen 1986). More

recently, ranges

of new electric brushes have appeared

with a variety

of head, tuft and filament actions. For

these, consensus

reports conclude that there is

evidence for greater

efficacy over manual brushes

particularly when pro

fessional advice in their use is

provided (for reviews see Hancock 1996, World

Workshop on Periodontics 1996a, Egelberg & Claffey

1998, van der Weijden et al.

1998). There is, at this

time, no evidence for concern

over potential harmful

effects to hard and soft tissues

because the force

applied to electric brushes tends to

be less than with

manual brushes (for review see van

der Weijden et al.

1998). Finally, there is no evidence

that any one

electric toothbrush design is superior and, again, the

user appears the major variable.

Chemical supragingival plaque control

History of oral hygiene products

The terminology "oral hygiene products" is recent but

there is evidence dating back at least 6000 years that

formulations and recipes existed to benefit oral and

dental health (for reviews see Fischman 1992, 1997).

This includes the written Ebers Papyrus 1500 BC con

-

taining recipes for tooth powders and mouthrinses

dating back to 4000 BC. A considerable number of

formulations can be attributed to the writer and scien

-

tist Hippocrates (circa 480 BC). By today's standards

the early formulations appear strange if not disgust-

ing but they were not always without logic. Thus,

bodies or body parts of animals perceived to have

good or continuously erupting teeth were used in the

belief that they would impart health and strength to

the teeth of the user. Hippocrates, for example, recom

-

mended the head of one hare and three whole mice,

after taking out the intestines of two, mixing the pow-

der derived from burning the animals with greasy

wool, honey, anise seeds, myrrh and white wine. This

early toothpaste was to be rubbed on the teeth fre-

quently.

Mouthrinses similarly contained ingredients which

would have had some salivary flow stimulating effect,

breath odor masking and antimicrobial actions, albeit

not necessarily formulated with all these activities in

mind. Alcohol-based mouthrinses were particularly

popular with the Romans and included white wine

and beer. Urine, as a mouthrinse, appeared to be popu

-

lar with many peoples and over many centuries. There

even appeared differences in opinion, with the Cant-

abri and other peoples of Spain preferring stale urine,

whereas Fauchard (1690-1761) in France recom-

mended fresh urine. The Arab nations were purported

to prefer children's urine and the Romans to prefer

Arab urine. Anecdotal reports suggest the use of urine

as a mouthrinse to this very day with individuals

rinsing with their own urine. There could, indeed, be

benefits to oral health from rinsing with urine by

virtue of the urea content; however this has never been

evaluated, and given today's Guidelines for Good

Clinical Practice, it is unlikely that study protocols

would receive ethical approval.

Throughout the centuries, most tooth powders,

toothpastes and mouthrinses appear to have been

formulated for cosmetic reasons including tooth

cleaning and breath freshening rather than the control

of dental and periodontal diseases. Many formula-

tions contain very abrasive ingredients and/or acidic

substances. However, ingredients with antimicrobial

properties were used, perhaps not intentionally, and

included arsenic and herbal materials. Herbal extracts

are, perhaps, increasingly being used in toothpastes

and mouthrinses, although there are little data to sup

-

port efficacy for gingivitis and none for caries. Many

agents prescribed well into the twentieth century, usu

-

ally as rinses, had the potential to cause local damage

to tissues, if not systemic toxicity, including aromatic

sulfuric acid, mercuric perchloride, carbolic acid and

formaldehyde (Dilling & Hallam 1936).

Perhaps the biggest change to toothpastes came

with the chemo-parasitic theory of tooth decay of W.

D. Miller in 1890. The theory that organic acids were

produced by oral bacteria acting on fermentable car-

bohydrates in contact with enamel led to both the

introduction of agents into toothpaste, which might

influence this process, and the production of alkaline

products. Shortly after, and at the beginning of the

twentieth century, various potassium and sodium

salts were added to toothpaste as a therapy for peri-

odontal disease. The first half of the twentieth century

saw numerous claims for toothpastes for oral health

benefits, including tooth decay and periodontal dis-

THE USE OF ANTISEPTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 467

ease. For example, with the early recognition that

periodontal diseases were associated with microor-

ganisms, emetin hydrochloride was added to tooth-

paste to treat possible amoebic infections. Perhaps

with the exception of the well-known essential oil

mouthrinse marketed at the end of the nineteenth

century, the addition of antimicrobial and/or antisep

-

tic agents to toothpastes and mouthrinses is a rela-

tively recent practice by manufacturers. During the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, toothpastes also

became less abrasive. Interestingly, the importance of

a

level of abrasivity in toothpastes to the prevention

of

extrinsic dental stain became apparent when one

manufacturer marketed a non-abrasive liquid denti-

frice. The unsightly brown tooth staining that devel-

oped in many users resulted in the early removal of

this product from the marketplace. More recently also,

standards organizations, notably the British Stand-

ards Institute and the International Standards Organi

-

zation, have laid down standards for toothpastes (BS

5136: 1981, ISO 11609: 1995) and a standard for

mouthrinses is under development. Such standards

are concerned with safety rather than efficacy.

Throughout the ages, and until relatively recently,

scientific evaluations of agents and formulations for

gum health were not performed and claims for effi-

cacy appear based on anecdotal reports at best. In-

deed, given the nature of many ingredients and the

recipes recommended in the past for oral hygiene

benefits, it is unlikely that efficacy will ever be tested.

In the 6000 years history of oral hygiene products,

scientific evaluation must be seen as an extremely

recent event – an observation which can, of course, be

applied to almost all aspects of chemo-prevention and

chemo-therapy of human diseases. Indeed, perhaps

the first ever, double-blind, randomized cross-over

design clinical trial in dentistry was just over 40 years

ago (Cooke & Armitage 1960).

Rationale for chemical supragingival plaque

control

The epidemiological data and clinical research (Ash et

al. 1964, Loe et al. 1965) directly associating plaque

with gingivitis perhaps, unfortunately, led to a rather

simplistic view that regular tooth cleaning would pre-

vent gingivitis and thereby periodontal disease. Theo-

retically correct, this concept did not appear to con-

sider the multiplicity of factors which influence the

ability of individuals to clean their teeth sufficiently

well to prevent disease, not the least of which are those

factors which affect individual compliance with ad-

vice and dexterity in performing such tasks. The need

for research into those psychosocial factors which

might influence attitude to and performance in oral

hygiene, was stated in a workshop report on plaque

control and oral hygiene practices (Frandsen 1986) but

appears not to have been heeded to this day. Moreover,

and as described in other chapters, epidemiological

data suggest that not all individuals are particularly

susceptible to periodontal disease. The most severe

disease is accounted for by a relatively small propor-

tion of any population and then by only a proportion

of sites in their dentition (Baelum et al. 1986). Even

accepting that a considerable proportion of middle-

aged adults will have one or more sites in the dentition

with moderate periodontal disease, this will be of the

chronic adult type and a minimal threat to the longev

-

ity of their dentition (Papapanou 1994). This requires

that prevention, through improved oral hygiene prac-

tices, will be grossly overprescribed.

Given our knowledge concerning the microbiologi-

cal specificity of periodontal disease and, more par-

ticularly host susceptibility to the disease, it is at

present difficult, if not impossible, to predict probable

future disease in the, as yet unaffected, host. At pre-

sent, host susceptibility is described retrospectively in

the already diseased individual but, even here, an

explanation for their susceptibility, except for a few

risk factors, cannot be made. These risk factors include

smoking, diabetes and polymorph defects and possi-

ble stress (for review see Johnson 1994, Porter & Scully

1994). Genetic markers for periodontal disease have

been identified but, at present, appear to be applied

retrospectively rather than prospectively (Kornman et

al. 1997) and the value to early onset disease has been

questioned (Hodge et al. 2001).

One definition of periodontal disease is chronic

gingivitis with loss of attachment. This is a particu-

larly useful definition since not only does it describe

the pathogenic processes occurring but also alludes to

the approach to prevent, treat or prevent re-occur-

rence of the disease. Therefore prevention through

supragingival plaque control still remains the main-

stay of controlling gingivitis and therefore the occur-

rence or re-occurrence of periodontitis (for review see

Addy & Adriaens 1998). As alluded to, the importance

of oral hygiene to outcome and long-term success of

therapy for periodontal disease is hampered by the

often ineffectiveness of mechanical cleaning to spe-

cific sites using a toothbrush and the limited or lack of

use of interdental cleaning by many individuals (for

reviews see Axelsson 1994). Despite the encouraging

improvements in oral hygiene, gingivitis and, to some

extent, periodontitis in developed countries, gingival

inflammation is still highly prevalent (for reviews see

Baehni & Bourgeois 1998). Taken with the microbial

etiology of both gingivitis and periodontitis, this sup-

ports the concept of employing agents to control

plaque which require minimal compliance and skill in

their use. This is the concept that underlies chemical

supragingival plaque control, but as with oral hygiene

instruction in mechanical methods, it will have to be

vastly overprescribed if periodontal disease preven-

tion is to be achieved in susceptible individuals.

Chemical supragingival plaque control has thus been

the subject of extensive research using scientific meth

-

odologies for approximately 40 years. The question to

be addressed here is whether a chemical or chemicals

468 • CHAPTER 22

have been discovered and proven efficacious in,

firstly, the prevention of gingivitis and, secondly, pe-

riodontitis.

Conclusions

•

Gingivitis and periodontitis are highly prevalent

diseases and prevention of occurrence or re-occur

-

rence is dependent on supragingival plaque control.

•

Tooth cleaning is largely influenced by the compli-

ance and dexterity of the individual and little by

design features of oral hygiene appliances and aids.

•

The concept of chemical plaque control may be

justified as a means of overcoming inadequacies of

mechanical cleaning.

•

Gingivitis is highly prevalent and from a young age

in all populations, but the proportion of individuals

susceptible to tooth loss through periodontal dis-

ease is small.

•

Prediction of susceptibility to periodontal disease

from an early age is at present impossible.

•

Mechanical and/or chemical supragingival plaque

control measures for prevention of periodontitis

will have to be greatly overprescribed.

Approaches to chemical supragingival

plaque control

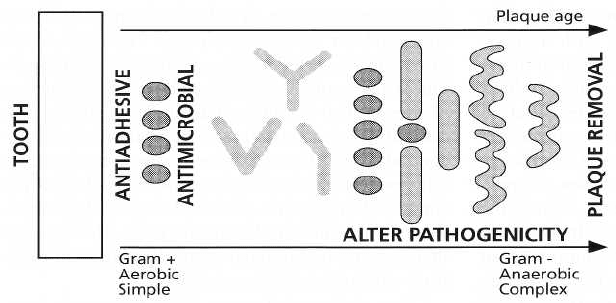

The well-ordered and dynamic process of plaque for-

mation as described previously and in other chapters,

can be summarized in Fig. 22-1. It is apparent that this

process can be interrupted, interfered with, reversed

or modified at several points and before the plaque

mass and/or complexity reaches a level whereby gin-

gival health deteriorates. Mechanical cleaning aims to

regularly remove sufficient microorganisms to leave a

"

healthy plaque" present, which cannot induce gingi-

val inflammation. Chemical agents, on the other hand,

could influence plaque quantitatively and qualita-

tively via a number of processes and these are sum-

marized in Fig. 22-1. The action of the chemicals could

fit into four categories:

1.

Antiadhesive

2.

Antimicrobial

Fig. 22-1. Bacterial succession

plaque formation. There is increas

-

ing mass and bacterial complexity

as plaque bacteria attach and pro

-

liferate. Ideal sites of action for

chemicals which might influence

plaque accumulation are shown.

Acknowledgement to Dr William

Wade for permission to publish

this diagram.

3.

Plaque removal

4.

Antipathogenic

Antiadhesive agents

Antiadhesive agents would act at the pellicle surface

to prevent the initial attachment of the primary plaque

forming bacteria. Such antiadhesive agents would

probably have to be totally preventive in their effects,

acting most effectively on an initially clean tooth sur-

face. Antiadhesive agents do exist and are used in

industry, domestically and in the environment. Such

chemicals prevent the attachment and development

of a variety of biofilms and are usually described as

antifouling agents. Unfortunately the chemicals

found in such applications are either too toxic for oral

use or ineffective against dental bacteria plaques.

Nevertheless, the concept of antiadhesives continues

to attract research interest (Moran et al. 1995, for re-

view see Wade & Slayne 1997). To date, effective for-

mulations or products with antiadhesive properties

are not available to the general public, although the

amine alcohol, delmopinol, which appears to interfere

with bacterial matrix formation and therefore fits

somewhere between the concepts of antiadhesion and

plaque removal, has been shown effective against

plaque and gingivitis (Collaert et al. 1992, Claydon et

al. 1996). Were antiadhesive agents to be discovered,

a

secondary benefit to extrinsic stain prevention of

teeth may be expected (Addy et al. 1995a).

Antimicrobial agents

The bacterial nature of dental plaque, not surprisingly,

attracted interest in prevention of plaque formation

through the use of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrobial

agents could inhibit plaque formation through one of

two mechanisms alone or combined. The first would

be the inhibition of bacterial proliferation and would

be directed, as with antiadhesive agents, at the pri-

mary plaque forming bacteria. Antimicrobial agents

therefore could exert their effects either at the pellicle

coated tooth surface before the primary plaque form-

ers attach or after attachment but before division of

these bacteria. This plaque inhibitory effect would be

bacteriostatic in type, with the result that the lack of

bacterial proliferation would not allow attachment of

THE USE OF ANTISEPTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 4

6

9

subsequent bacterial types on to the primary plaque

forming bacteria. The second effect could be bacte-

riocidal whereby the antimicrobial agent destroys all

of the microorganisms either attaching or already at-

tached to the tooth surface. Many antimicrobial agents

exist which could produce this effect; however, as will

be discussed, to be effective in inhibiting plaque, the

bacteriocidal effect would have to be absolute or per-

sistent. If not, other bacteria within the oral environ-

ment would colonize the tooth surface immediately

following the loss of the bacteriocidal effect and the

biofilm would be re-established. For the most part

biofilms in themselves are fairly resistant to total bac-

teriocidal effects of antimicrobial agents and, thus far,

there does not appear to have been any agent discov-

ered which effectively would sterilize the tooth sur-

face after each application. If such an agent were

found it could, of course, have potentially dangerous

implications for the oral cavity since it would almost

certainly destroy most of the commensal bacteria

which normal colonize the oral cavity. This would

open up the potential for exogenous microorganisms,

with dangerous pathogenic potential, colonizing the

oral cavity. In the event, it is probable that antimicro-

bial agents exert both a bacteriocidal effect followed

by a bacteriostatic action of variable duration. The

bactertiocidal effect will occur when the antimicrobial

agent is at high concentration within the oral cavity

and usually this will represent the time when the

formulation is actually within the oral cavity. The

bacteriocidal effect would be expected to be lost very

soon after expectoration.

As will be discussed in respect of chlorhexidine, it

is almost certainly the persistence of the bacteriostatic

action of antimicrobial agents which accounts for their

plaque inhibitory activity. Calculations by Stralfors

(

1961) indicated that plaque inhibition through a bac

-

teriocidal effect would require the immediate killing

of

99.9% of the oral bacteria to effect a plaque inhibi-

tory action of significant duration. Antimicrobial

agents for plaque inhibition, to date, are the only

agents that have found common usage in oral hygiene

products. The efficacy of these agents and products

varies at the extremes (for reviews see Addy 1986,

Kornman 1986, Mandel 1988, Addy et al. 1994, Addy

& Renton-Harper 1996a, Rolla et al. 1997).

Plaque removal agents

The idea of employing a chemical agent which would

act in an identical manner to a toothbrush and remove

bacteria from the tooth surface, is an attractive propo

-

sition. Such an agent, contained in a mouthrinse,

would be expected to reach all tooth surfaces and

thereby be totally effective. For this reason, the idea of

chemical plaque removal agents has attracted the ter

-

minology of "the chemical toothbrush". As with an-

tiadhesives, there are potentially agents, such as the

hypochlorites, which might be expected to remove

bacterial deposits and are commonly employed within

the domestic environment. Again, such chemi-

cals would be potentially toxic were they to be applied

within the oral cavity. Perhaps the nearest success was

with enzymes directed at both the pellicle, e.g. pro-

teases, or the bacterial matrices, e.g. dextranase and

mutanase (for review see Kornman 1986). Again, as

will be discussed, these enzymes, albeit potentially

effective, lacked substantivity within the oral cavity.

Antipathogenic

agents

It is theoretically possible that an agent could have an

effect on plaque microorganisms, which might inhibit

the expression of their pathogenicity without neces-

sarily destroying the microorganisms. In some re-

spects antimicrobial agents, which exert a bacte-

riostatic effect, achieve such results. At present the

understanding of the pathogenesis of gingivitis is so

poor that this approach has received no attention.

Were our knowledge on the microbial etiology of gin-

givitis to improve, clearly there exists the possibility

of an alternative, but related, approach: the introduc-

tion into the oral cavity of organisms which have been

modified to remove their pathogenic potential to the

gingival tissues. This is not a new concept and was an

approach experimented with to replace pathogenic

staphylococci within the nasal cavities of surgeons

with the idea of reducing the potential for wound

infection caused by the operator. At present such an

approach within the oral cavity for either gingivitis or

caries is perhaps within the realms of science fiction.

Conclusions

•

At present most antiplaque agents are

antimicrobial

and prevent the bacterial

proliferation phase of

plaque development.

•

Plaque formation could be controlled by antiadhe-

sive or plaque removal agents, but these are not, as

yet, available or safe for oral use.

•

Alteration of bacterial plaque pathogenicity through

chemical agents or bacterial modification would

require a greater understanding of the bacterial eti-

ology of gingivitis.

Vehicles for the delivery of chemical agents

The carriage of chemical agents into the mouth for

supragingival plaque control has involved a small but

varied range of vehicles (for reviews see Addy 1994,

Cummins 1997).

Toothpaste

By virtue of common usage the ideal vehicle for the

carriage of plaque control agents is toothpaste. Anum

-

ber of ingredients go to make up toothpaste and each

has a role in either influencing the consistency and

stability of the product or its function (for reviews see

Davis 1980, Forward et al. 1997).

The major ingredients may be classified under the

following headings:

470 • CHAPTER 22

1. Abrasives,

such as silica, alumina, dicalcium phos-

phate and calcium carbonate either alone, or more

usually today, in combination. Abrasives affect the

consistency of the toothpaste and assist in the con

-

trol of extrinsic dental staining.

2. Detergents:

the most common detergent used in

toothpaste is sodium lauryl sulfate, which imparts

the foaming and "feel" properties to the product.

Additionally, detergents may help dissolve active

ingredients and the anionic detergent sodium lau-

ryl sulfate has both antimicrobial and plaque in-

hibitory properties (Moran et al. 1988, Jenkins et al.

1991a,b). Certain toothpaste products cannot em-

ploy anionic detergents as they interact with cat-

ionic substances that may be added to the product

such as chlorhexidine or polyvalent metal salts

such as strontium used in the treatment of dentine

hypersensitivity.

3. Thickeners,

such as silica and gums.

4. Sweeteners,

including saccharine.

5. Huniectants,

notably glycerine and sorbitol to pre-

vent drying out of the paste once the tube has been

opened.

6. Flavors,

of which there are many but mint or pep-

permint are popular in the western world although

rarely found in toothpaste in the Indian subconti-

nent where herbal flavors are more popular.

7. Actives,

notably fluorides for caries prevention, but

for plaque control triclosan and stannous fluoride

have been the most common examples.

As stated, the addition of cationic antiseptics to tooth

-

pastes is difficult but chlorhexidine has been formu-

lated into toothpastes and shown to be effective

(

Gjermo & Rolla 1970, 1971, Yates et al. 1993, Sanz et

al. 1994).

Mouthrinses

Despite the ideal nature of the toothpaste vehicle,

most chemical plaque control agents have been evalu

-

ated and later formulated in the mouthrinse vehicle.

Mouthrinses vary in their constituents but are usually

considerably less complex than toothpastes. They can

be simple aqueous solutions, but the need for prod-

ucts, purchased by the general public, to be stable and

acceptable in taste usually requires the addition of

flavoring, coloring and preservatives such as sodium

benzoate. Anionic detergents are included in some

products but, again, cannot be formulated with cat-

ionic antiseptics such as cetylpyridinium chloride or

chlorhexidine (Barkvoll et al. 1989). Ethyl alcohol is

commonly used both to stabilize certain active ingre-

dients and to improve the shelf-life of the product.

Concerns over the possible association of alcohol in-

take and pharyngeal cancer have been extended to

include alcohol-containing mouthrinses. Whether

these concerns are scientifically valid has not been

established. Also, since at present there seems little

support for the long-term chronic use of mouthrinses

for gingival health benefits, when correctly prescribed

the risk from contained alcohol is probably minuscule.

This, however, does not obviate the possible risk from

self-prescription, the chronic use of mouthrinses, or

the ingestion of alcoholic mouthrinses by children.

The proportion of alcohol is usually less than 10% but

some rinses have in excess of 20% alcohol. Some

manufacturers are now producing alcohol-free

mouthrinses.

Spray

Spray delivery of chemical plaque control agents has

attracted both research interest and the development

of products by some manufacturers in some countries.

Sprays have the advantage of focusing delivery on the

required site. The dose is clearly reduced and for

antiseptics such as chlorhexidine this has taste advan

-

tages. When correctly applied chlorhexidine sprays

were as effective as mouthrinses for plaque inhibition

although there was no reduction in staining (Francis

et al. 1987a, Kalaga et al. 1989a). Chlorhexidine sprays

were found particularly useful for plaque control in

physically and mentally handicapped groups (Francis

et al. 1987a,b, Kalaga et al. 1989b).

Irrigators

Irrigators were designed to spray water, under pres-

sure, around the teeth. As such they only removed

debris, with little effect on plaque deposits (for review

see Frandsen 1986). Antiseptics and other chemical

plaque control agents, such as chlorhexidine, have

been added to the reservoir of such devices. A variety

of dilutions of chlorhexidine have been employed to

good effect (Lang & Raber 1981).

Chewing gum

Over a relatively short period there has been interest

in employing chewing gum to deliver a variety of

agents for oral health benefits. Also, there appear to be

significant benefits to dental health through the use of

sugar-free chewing gum. Unfortunately, chewing

gums alone appear to have little in the way of plaque

control benefits particularly at sites prone to gingivitis

(

Addy et al. 1982a). Nonetheless, the vehicle has been

used to deliver chemical agents such as chlorhexidine

and, when used as an adjunct to normal toothbrush-

ing, reduced plaque and gingivitis levels have been

shown (Ainamo & Etemadzadeh 1987, Ainamo et al.

1990, Smith et al. 1996).

Varnishes

Varnishes have been employed to deliver antiseptics

including chlorhexidine, but the purpose has been to

prevent root caries rather than as a reservoir for plaque

control throughout the mouth.

Conclusions

•

Many vehicles may be used to deliver antiplaque

agents but most information relates to mouthrinses

and toothpaste.

•

Toothpaste appears the most practical and cost ef-

THE USE OF ANTISEPTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 47

1

fective method for chemical plaque control for most

individuals.

•

In formulating antiplaque agents into toothpaste,

potential inactivation by other ingredients must be

considered.

•

Minority groups, such as the handicapped, may

benefit from other delivery systems.

CHEMICAL PLAQUE CONTROL

AGENTS

Over a period of more than three decades there has

been quite intense interest in the use of chemical

agents to control supragingival plaque and thereby

gingivitis. The number and variation of chemical

agents evaluated are quite large but most have anti-

septic or antimicrobial actions and success has been

variable at the extreme. It is important to emphasize

that formulations based on antimicrobial agents pro-

vide a considerably greater preventive than therapeu-

tic action. The most effective agents inhibit the devel-

opment of plaque and gingivitis but are limited or

slow to affect established plaque and gingivitis. Were

they available, antiadhesive agents would similarly

be

expected to provide preventive rather than thera-

peutic effects, although plaque removal agents would

almost certainly provide both preventive and thera-

peutic actions. Chemical plaque control agents have

been the subject of many detailed reviews since 1980

(Hull 1980, Addy 1986, Kornman 1986, Mandel 1988,

Gjermo 1989, Addy et al. 1994, Heasman & Seymour

1994, Jackson 1997). Based on knowledge derived

from chlorhexidine, the most effective plaque inhibi-

tory agents in the antiseptic or antimicrobial group are

those showing persistence of action in the mouth

measured in hours. Such persistence of action, some

-

times termed substantivity (Kornman 1986), appears

dependent on several factors:

1.

Adsorption and prolonged retention on oral sur-

faces including, importantly, pellicle coated teeth.

2.

Maintenance of antimicrobial activity once ad-

sorbed primarily through a bacteriostatic action

against the primary plaque forming bacteria.

3.

Minimal or slow neutralization of antimicrobial

activity within the oral environment or slow

desorption from surfaces.

The latter concepts will be discussed later under chlor

-

hexidine.

Antimicrobial activity in

vitro

of antiseptics

per se is

not a reliable predictor of plaque inhibitory activity

in

vivo

(Gjermo et al. 1970, 1973). Early studies on a

number of antiseptics revealed similar antimicrobial

profiles but a large variation in clinical effects. For

example, compared to chlorhexidine, the cationic qua

-

ternary ammonium compound, cetylpyridinium

chloride, has a similar antimicrobial profile

in vitro

(Gjermo et al. 1970, 1973, Roberts & Addy, 1981) and

is initially adsorbed in the mouth to a considerably

greater extent (Bonesvoll & Gjermo 1978). However,

the persistence of action of cetylpyridinium chloride

is

much shorter than chlorhexidine (Schiott et al. 1970,

Roberts & Addy, 1981), and plaque inhibition consid-

erably less (for review see Mandel 1988). Several rea-

sons may explain these apparent anomalies, including

poor retention of cetylpyridinium chloride within the

oral cavity (Bonesvoll & Gjermo 1978), reduced activ-

ity once adsorbed, and neutralization in the oral envi-

ronment (Moran & Addy 1984), or a combination of

these factors. Attempts to improve efficacy of ce-

tylpyridinium chloride can, of course, include increas

-

ing the frequency of use, but this is likely to incur

compliance problems and side effects (Bonesvoll &

Gjermo 1978). Alternatively, substantivity could be

improved by combining antimicrobials or using

agents to increase the retention of antimicrobials (for

review see Cummins 1992, Gaffar et al. 1992). Individ

-

ual groups of compounds, together with the specific

agents within the group, are listed in Table 22-1 and

discussed under the following headings.

Antibiotics (for reviews see Addy 1986, Kornman 1986)

Despite evidence for efficacy in preventing caries and

gingivitis or resolving gingivitis, the opinion today is

that antibiotics should not be used either topically or

systemically as preventive agents against these dis-

eases. The risk-to-benefit ratio is high and even anti-

biotic use in the treatment of adult periodontitis is

open to debate (for reviews see Genco 1981, Slots &

Rams 1990, Addy & Renton-Harper 1996b and Chap

-

ter 23). Thus, antibiotics have their own specific side

effects not all of which can be avoided by topical

application. Perhaps of greatest importance is the de-

velopment of bacterial resistance within human popu

-

lations, for example the methycillin-resistant

Staphy-

lococcus

aureas

(MRSA), which causes serious and life-

threatening wound infections, particularly within

hospitalized patients.

Enzymes

(for reviews see Addy 1986)

Enzymes fall into two groups. Those in the first group

are not truly antimicrobial agents but more plaque

removal agents in that they have the potential to

disrupt the early plaque matrix, thereby dislodging

bacteria from the tooth surface. In the late 1960s/early

1970s enzymes such as dextranase, mutanase and

various proteases were thought to be a major break-

through in dental plaque control that might prevent

the development of both caries and gingivitis. Such

agents, unfortunately, had poor substantivity and

were not without unpleasant local side effects, notably

mucosal erosion. The second group of enzymes em-

ployed glucose oxidase and amyloglucosidase to en-

hance the host defense mechanism. The aim was to

catalyse the conversion of endogenous and exogenous

thiocyanate to hypothiocyanite via the salivary lac-

toperoxydase system. The hypothiocycanite produces

472 • CHAPTER 22

Table 22-1. Groups of agents used in the control of dental plaque and/or gingivitis

Group

Examples of agents

Action

Used now/product

Antibiotics

Penicillin

Vancomycin

Kanamycin

Niddamycin

Spiromycin

Antimicrobial

No

Enzymes

Protease

Lipase

Nuclease

Dextranase

Mutanase

*Glucose oxidase

*Amyloglucosidase

Plaque removal

Antimicrobial

No

*Yes

Toothpaste

Bisbiguanide antiseptics

*Chlorhexidine

Alexidine

Octenidine

Antimicrobial

*Yes

Mouthrinse

Spray

Gel

Toothpaste

Chewing gum

Varnish

Quaternary ammonium

compounds

*Cetylpyridinium chloride

*Benzalconium chloride

Antimicrobial

*Yes

Mouthrinse

Phenols & essential oils

*Thymol

*Hexylresorcinol

*Ecalyptol

*Triclosan+

*Antimicrobial

+Anti-inflammatory

*Yes

Mouthrinse

Toothpaste

Natural products *Sanguinarine

Antimicrobial

*Yes

Mouthrinse

Toothpaste

Fluorides

(*)Sodium Fluoride

(*)Sodium monofluoro-

phosphate

*Stannous fluoride+

+Amine fluoride

*Antimicrobial

( )minimal

+?

+*Yes

Toothpaste

Mouthrinse

+Gel

Metal salts

*Tin+

*Zinc

Copper

Antimicrobial

*Yes

Toothpaste

Mouthrinse

+Gel

__

Oxygenating agents

Li

*Hydrogen peroxide

*Sodium peroxyborate

*Sodium peroxycarbonate

Antimicrobial

?Plaque removal

*Yes

Mouthrinse

Detergents

*Sodium lauryl sulfate

Antimicrobial

?plaque removal

*Yes

Toothpaste

Mouthrinse

Amine alcohols

Octapinol

Delmopinol

Plaque matrix

Inhibition

No

inhibitory effects upon oral bacteria, particularly paste products containing the enzymes and thiocy-

streptococci, to interfere with their metabolism. This

anate were produced but equivocal results for benefits

approach is a theoretical possibility and the chemical

to gingivitis were obtained and there are no convinc-

processes can be produced in the laboratory. Tooth- ing long-term studies of efficacy.

THE USE OF ANTISEPTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 473

Bisbiguanide

antiseptics (for review see Addy et al.

1986, 1994, Kornman 1986, Gjermo 1989, Jones 1997)

Chlorhexidine is thus far the most studied and effec-

tive antiseptic for plaque inhibition and the preven-

tion of gingivitis. Consequent upon the original pub-

lication (Loe & Schiott 1970), chlorhexidine, arguably

perhaps, represents the nearest that research has come

to identifying a chemical agent that could be used as

a replacement for, rather than an adjunct to, mechani

-

cal oral hygiene practices. Other bisbiguanides such

as alexidine and octenidine have less or similar activ-

ity, respectively, to chlorhexidine but bring with them

no improvement in local side effects and have less

toxicity data available. Chlorhexidine has thus re-

mained the only bisbiguanide used in a number of

vehicles and available in commercial products. In

view of the importance of this antiseptic within pre-

ventive dentistry, a separate section later in the chap-

ter will be devoted to considering its activity and

usage in the mouth.

Quaternary ammonium compounds

(for review see

Mandel 1988)

Benzylconium chloride and, more particularly, ce-

tylpyridinium chloride are the most studied of this

family of antiseptics. Cetylpyridinium chloride is

used

in a wide variety of antiseptic mouthrinse products

usually at a concentration of 0.05%. At oral pH

these

antiseptics are monocationic and adsorb readily

and

quantitatively, to a greater extent, than chlor

hexidine

to oral surfaces (Bonesvoll & Gjermo 1978).

However,

the substantivity of cetylpyridinium chlo

ride appears

to be only 3-5 hours (Roberts & Addy 1981) due

either to loss of activity once adsorbed or

rapid

desorption. Cetylpyridinium chloride in

mouthrinses

has some chemical plaque inhibitory ac-

tion but

evidence for gingivitis benefits is equivocal,

particularly when formulations are used alongside

toothbrushing with toothpaste. Long-term home use

studies, given the large number of rinse products

containing this antiseptic, are surprisingly few. Those

that are available, with one exception, failed to dem-

onstrate any adjunctive benefits to toothbrushing

with toothpaste, of cetylpyridinium chloride mouth-

rinses. The one exception (Allen et al. 1998) was pecu

-

liar in that there was a lack of the expected Hawthorne

effect in the control group (see section "Evaluation of

chemical agents and products" later in this chapter)

and the plaque reduction in the active group, 28%, was

as great as seen in chemical plaque inhibition studies.

As will be discussed, it is not unusual to find chemi-

cals that provide modest, even moderate, plaque inhi-

bition in no brushing studies but fail to show effects

in adjunctive home use studies. This occurs because

the range over which to show a benefit of the chemical

is limited by the mechanical oral hygiene practices of

the study subjects. The efficacy of cetylpyridinium

chloride can be increased by doubling the frequency

of rinsing to four times per day (Bonsvoll & Gjermo

1978), but this increases local side effects, including

tooth staining, and would affect compliance.

Mouthrinses combining cetylpyridinium chloride with

chlorhexidine are available and compare well

with

established chlorhexidine products (Quirynen et

al.

2001). Whether the cetylpyridinium chloride actu

ally

contributed to the activity of the chlorhexidine

cannot

be assessed. There is limited information on

quaternary ammonium compounds in toothpastes

and very few products are available.

Phenols and essential oils

(for review see Mandel

1988)

Phenols and essential oils have been used in mouth-

rinses and lozenges for many years. One mouthrinse

formulation dates back more than 100 years and al-

though not as efficacious as chlorhexidine, has anti-

plaque activity supported by a number of short and

long-term home use studies. Combining essential oils

with cetylpyridinium chloride has been attempted

and with promising results from initial studies

(

Hunter et al. 1994).

The non-ionic antimicrobial triclosan is usually

considered to belong to the phenol group and has been

widely used over many years in a number of medi-

cated products including antiperspirants and soaps.

More recently, it has been formulated into toothpaste

and mouthrinses and, for the former, has accumulated

an impressive amount of literature, some of which is

conflicting. In simple solutions, at relatively high con-

centrations (0.2%) and dose (20 mg twice per day),

triclosan has moderate plaque inhibitory action and

antimicrobial substantivity of around 5 hours (Jenkins

et al. 1991a,b). The dose response against plaque of

triclosan alone is relatively flat (Jenkins et al. 1993)

although significantly greater benefits are obtained at

20 mg doses twice daily compared to 10 mg doses. In

terms of plaque inhibition, a 0.1% triclosan concentra

-

tion (10 mg dose twice per day) was considerably less

effective than a 0.01% chlorhexidine mouthrinse (1 mg

twice per day) (Jenkins et al. 1994).

The activity of triclosan appears to be enhanced by

the addition of zinc citrate or the co-polymer, poly-

vinylmethyl ether maleic acid (for reviews see Cum-

mins 1992, Gaffar et al. 1992). The co-polymer appears

to enhance the retention of triclosan whereas the zinc

is thought to increase the antimicrobial activity. Only

triclosan toothpastes with the co-polymer or zinc cit-

rate have shown antiplaque activity in long-term

home use studies (Svatun et al. 1989, Garcia-Gadoy et

al. 1990, Stephen et al. 1990, for review see Jackson

1997). Some home use studies showed little or no

effect for one or other of the products on plaque alone,

gingivitis alone or both (Palomo et al. 1994, Kancha-

nakamol et al. 1995, Renvert & Birkhed 1995, Binney

et al. 1996, Owens et al. 1997). Triclosan toothpastes

appear to provide greater gingivitis benefits in some

studies than plaque reductions and this could be ex-

plained by a possible anti-inflammatory action for this

agent (Barkvoll & Rolla 1994).

More recently, long-term studies have suggested

474 • CHAPTER 22

that triclosan-containing toothpaste can reduce the

progress of periodontitis, although the effects were so

small as to be of questionable clinical relevance (

Rosling et al. 1997, Ellwood et al. 1998). Mouthrinses

containing triclosan and the co-polymer are available,

with some evidence of adjunctive benefits to oral hy-

giene and gingival health when used alongside nor-

mal tooth cleaning (Worthington et al. 1993). This

latter study was again interesting with, unusually, no

clear Hawthorne effect in the control group. Other

studies on the plaque inhibitory properties of a tri-

closan/co-polymer mouthrinse showed effects sig-

nificantly less than an essential oil mouthrinse prod-

uct (Moran et al. 1997).

Natural

products (for review see Mandel 1988)

Herb and plant extracts have been used in oral hy-

giene products for many years if not centuries. Unfor-

tunately, there are few data available and such tooth-

paste products provide no greater benefits to oral

hygiene and gingival health than conventional fluo-

ride toothpaste does (Moran et al. 1991). The plant

extract sanguinarine has been used in a number of

formulations. Zinc salts are also incorporated, which

makes it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of sangui-

narine alone. However, even when it is combined with

zinc, data are equivocal for benefits (Moran et al.

1988a, 1992a, Quirynen et al. 1990). Some positive

findings were reported for the combined use of san-

guinarine/zinc toothpaste and mouthrinses (Kopczyk

et al. 1991), but the benefit-to-cost ratio must be

low.

Importantly and very recently, sanguinarine-con-

taining mouthrinses have been shown to increase the

likelihood of oral precancerous lesions almost ten-fold

even after cessation of mouthrinse use. The manufac-

turer of the most well-known product has replaced

sanguinarine in the mouthrinses with an alternative

agent.

Fluorides

The caries preventive benefits for a number of fluoride

salts are well established but the fluoride ion has no

effect against the development of plaque and gingivi-

tis. Amine fluoride and stannous fluoride provide

some plaque inhibitory activity, particularly when

combined; however, the effects appear to be derived

from the non-fluoride portion of the molecules. A

mouthrinse product containing amine fluoride and

stannous fluoride is available and there is some evi-

dence from home use studies of efficacy against

plaque and gingivitis (Brecx et al. 1990, 1992), but less

so than chlorhexidine.

Metal salts

(for reviews see Addy et al. 1994, Jackson

1997)

Antimicrobial actions including plaque inhibition by

metal salts have been appreciated for many years,

with most research interest centered on copper, tin and

zinc. Results have been somewhat contradictory but

appear dependent on the metal salt used, its concen-

tration and use. Essentially, polyvalent metal salts

alone are effective plaque inhibitors at relatively high

concentration when taste and toxicity problems may

arise. Stannous fluoride is an exception but is difficult

to formulate into oral hygiene products because of

stability problems, with hydrolysis occurring in the

presence of water (Miller et al. 1969). Stable anhydrous

gel and toothpaste products are available with evi-

dence of efficacy against plaque and gingivitis

(

Beiswanger et al. 1995, Perlich et al. 1995). Stannous

pyrophosphate at 1% has been added to some stan-

nous fluoride toothpaste to good effect (Svatun et al.

1978). Indeed, it appears that the concentration of

available stannous ions is the most significant factor

in determining efficacy (Addy et al. 1997). Dental

staining, however, occurs with stannous formulations

and appears to occur by the same mechanism as for

chlorhexidine and other cationic antiseptics, involv-

ing interaction with dietary chromogens (for reviews

see Addy & Moran 1995, Watts & Addy 2001). Com-

bining metal salts with other antiseptics produces

added plaque and gingivitis inhibitory effects, for

example zinc and hexetidine (Saxer & Muhlemann

1983) and, as already described, zinc and triclosan.

Copper also causes dental staining but is not available

in oral hygiene products. Zinc, at low concentration,

has no side effects and is used in a number of tooth-

pastes and mouthrinses; however, alone it has little

effect on plaque (Addy et al. 1980) except at higher

concentrations.

Oxygenating

agents (for review see Addy et al. 1994)

Oxygenating agents have been used as disinfectants

in various disciplines of dentistry, including endodon

-

tics and periodontics. Hydrogen peroxide has been

employed for supragingival plaque control and more

recently has become important as a bleach in tooth

whitening. Similarly, peroxyborate may be used in the

treatment of acute ulcerative gingivitis (Wade et al.

1966). Products containing peroxyborate and peroxy

-

carbonate are available in Britain and Europe with

evidence of antimicrobial and plaque inhibitory activ-

ity (Moran et al. 1995). There are little data from long

-

term home use studies and such evaluations would

seem warranted before conclusions about true anti-

plaque activity can be drawn.

Detergents

Detergents, such as sodium lauryl sulfate, are com-

mon ingredients in toothpaste and mouthrinse prod-

ucts. Besides other qualities and, for that matter, side

effects, detergents such as sodium lauryl sulfate have

antimicrobial activity (Moran et al. 1988b) and prob-

ably provide most of the modest plaque inhibitory

action of toothpaste (Addy et al. 1983). Alone, sodium

lauryl sulfate was shown to have moderate substan-

tivity measured at between 5 and

7

hours and plaque

inhibitory action similar to triclosan (Jenkins et al.

1991a,b). Detergent only formulations are not avail-