Jan Lindhe. Clinical Periodontology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE USE OF ANTIBIOTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 495

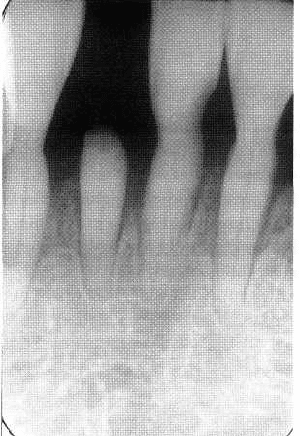

Fig. 23-1. Conventional periodontal therapy and main

tenance imply repeated treatment of sites with

local

ized unresponsive or recurrent disease,

resulting in

sometimes substantial hard tissue

trauma.

are not completely eradicated, persistence or re-

growth of certain microorganisms in treated sites

should be considered the main cause of unsatisfactory

treatment outcomes.

Can antimicrobial agents, delivered

either locally or systemically, enhance the effect of root

instrumentation, limit its side effects, or could they even be

a substitute in some cases?

ht the late 1930s and early 1940s the appearance of

potent chemotherapeutic agents selectively active

against bacteria, revolutionized the treatment of bac-

terial infections. The discovery of such drugs – sul-

fonamides, penicillin and streptomycin – led many to

believe that bacterial infections were about to vanish.

After six decades of experience with these and hun-

dreds of additionally developed chemotherapeutic

drugs, the potential and limitation of antimicrobial

therapy are better understood. Emerging problems,

resulting from the widespread use of antibiotics have

modified the general perception of the capabilities of

antimicrobial agents. Over the years, bacteria have

developed a remarkable ability to withstand or repel

many antibiotic agents and are increasingly resistant

to formerly potent agents. The use of antibiotics may

disturb the delicate ecologic equilibrium of the body,

allowing the proliferation of resistant bacteria or non-

bacterial organisms. Sometimes this may initiate new

infections that are worse than the ones originally

treated. In addition, no antibacterial drug is absolutely

non-toxic and the use of any antimicrobial agent car-

ries with it accompanying risks.

Before any antimicrobial agent can be recom-

mended for periodontal therapy a number of condi-

tions need to be fulfilled. First, the drug must show

in

vitro

activity against the organisms considered most

important in the etiology of the disease. Next it should

be demonstrated that a dose sufficient to kill the target

organisms can be reached within the subgingival en-

vironment. At this dose the drug should not have

major local or systemic adverse effects. It should be

safe to maintain the required concentration over a

long enough period to significantly affect the micro-

biota. Well-controlled longitudinal studies then need

to be carried out in patients with periodontal disease,

demonstrating a favorable clinical outcome of therapy

with the agent. Finally, one would like to see a practi-

cal advantage over conventional treatment alterna-

tives (better outcome, less adverse effects, simpler to

perform, cheaper, faster).

Specific characteristics of the periodontal

infection

In discussing the potential usefulness of chemo-

therapeutic agents to treat periodontal diseases, one

should be clear that antibiotics and antiseptics can kill

living bacteria, but will neither eliminate calculus nor

remove bacterial debris. The recognition of periodon-

titis as an infection caused by living microorganisms

is thus a fundamental issue for any chemotherapeutic

treatment concept. The term infection refers to the

presence and multiplication of microorganisms in or

on body tissues. The uniqueness of plaque-associated

dental diseases as infections relates to the lack of

massive bacterial invasion of tissues. Although there

is evidence for bacterial penetration in severely dis-

eased periodontal tissues, notably in periodontal ab-

scesses and in acute necrotizing ulcerative lesions

(

Listgarten 1965, Saglie et al. 1982a,b, Allenspach-

Petrzilka & Guggenheim 1983, Carranza et al. 1983),

it has not been generally accepted that true bacterial

invasion (including multiplication of bacteria within

tissues) is crucial for periodontal disease progression.

Bacteria in the subgingival plaque obviously interact

with host tissues even without direct tissue penetra-

tion. Thus, for any antimicrobial agent used in peri-

odontal therapy to have an effect there is the require-

ment that the agent is available at a sufficiently high

concentration not only within, but also in the sub-

gingival environment outside the periodontal tissues

496 • CHAPTER 23

(Fig.

23-2).

Periodontal pockets may actually contain

an enormous amount of bacteria. This may cause

problems for antimicrobial agents to work properly

because they may be inhibited, inactivated or de-

graded by non-target microorganisms.

In addition, the subgingival microbiota accumulate

on the root surface to form an adherent layer of plaque.

Accumulation of bacteria on solid surfaces can be

observed on virtually all surfaces immersed in natural

aqueous environments and is called "biofilm" forma-

tion. Extensive bacterial growth, accompanied by ex-

cretion of copious amounts of extracellular polymers,

is

a typical phenomenon in biofilms. Biofilms effec-

tively protect bacteria from antimicrobial agents (An-

war et al.

1990, 1992). Bacteria involved in adhesion-

mediated infections that develop on permanently or

temporarily implanted materials such as intravascu-

lar catheters, vascular prostheses or heart valves are

notoriously resistant to systemic antimicrobial ther-

apy and tend to persist until the device is removed

(

Gristina

1987,

Marshall

1992).

Several mechanisms

leading to this increased resistance of bacteria in

biofilms have been proposed. Due to limited diffu-

sion, antimicrobial agents may simply not reach

deeper parts of a biofilm at sufficiently high levels

during a given time of exposure. Within biofilms an

unequal distribution of electrical charge may develop.

Intrusion may thus be further complicated in certain

areas of the biofilm depending on the charge of the

penetrating molecule. Because of a limited availability

of nutrients within the biofilm, bacteria may also re-

duce their metabolism, rendering them less suscepti-

ble to killing by agents interfering with protein, DNA

or cell wall synthesis. Most interesting are the results

from recent

in vitro

experiments, indicating that the

attachment of bacteria to surfaces may trigger genes

which activate specific resistance mechanisms. Since

these mechanisms are switched on upon contact, they

may occur already in newly forming, very thin

biofilms (Costerton et al.

1995).

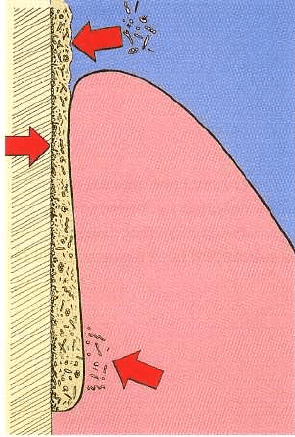

Fig. 23-2. Specific conditions for the use of antimicro

-

bial agents in periodontal therapy. The periodontal

pocket as an open site is subject to recolonization after

therapy (top arrow). The subgingival bacteria are pro

-

tected from antimicrobial agents in a biofilm (middle

arrow). The agent must be available at a sufficiently

high concentration not only within, but also in the sub

-

gingival environment outside, the periodontal tissues

(bottom arrow).

The above described problems suggest that treat-

ment of periodontal diseases by antimicrobial agents

alone will probably not suffice and indicate that me-

chanical instrumentation to disrupt the biofilm and to

remove the bulk of bacterial deposits must precede

antimicrobial therapy.

Infection concepts and treatment goals

Infections may be divided into exogenous and endo-

genous on the basis of the source of the infecting agent.

While

exogenous infections

are caused by organisms

acquired from an external source (primary patho-

gens),

endogenous infections

are caused by organisms

present already in the healthy host (commensal organ

-

isms). Infections caused by endogenous microbes are

called

opportunistic infections

if they occur in the usual

habitat of the organisms. They may be the result of

changing ecologic conditions or may be due to a de-

crease in host resistance. Exogenous infections are

caused by organisms that are not part of the normal

flora. They are transmitted to healthy subjects from

diseased humans or animals, or from carriers that

show no signs of disease. A.

actinomycetemcomitans

and

P.

gingivalis

are regarded as true infectious agents

in

periodontal disease by some researchers. This view

is

based on findings of low prevalence of these micro-

organisms in periodontally healthy individuals in

North America and Europe, evidence for transmis-

sion, such as from parent to child or between spouses,

findings of immune responses towards these bacteria

that markedly exceed those expected for endogenous

infections and on clinical studies showing that A.

actinomycetemcomitans

and

P.

gingivalis

can be elimi-

nated with appropriate mechanical treatment and ad

-

junctive antibiotic therapy (for review see van Winkel-

hoff et al. 1996).

The majority of organisms associated with peri-

odontal disease can, however, also be detected fre-

THE USE OF ANTIBIOTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 497

Table 23-1. Comparison of local and systemic antimicrobial therapy

Issue

Systemic administration

Local administration

Drug distribution Wide distribution

Narrow effective range

Drug concentration

Variable levels in different body compartments

High dose at treated site, low levels elsewhere

Therapeutic potential

May reach widely distributed microorganisms May act better locally on biofilm associated

better

bacteria

Problems

Systemic side effects

Reinfection from non-treated sites

Clinical limitations

Requires good patient compliance

Infection limited to the treated site

Diagnostic problems Identification of pathogens, choice of drug

Distribution pattern of lesions and pathogens,

identification of sites to be treated

quently at low numbers in the absence of periodontal

disease, and the view that A.

actinomyceterncomitans

and

P.

gingivalis

cause true infections has been op-

posed on the basis of cross-sectional studies showing

a

high prevalence of the two organisms in certain

populations, particularly those from developing

countries. If

A.

actinomyceterncomitans

and

P.

gingivalis

are truly exogenous pathogens, the elimination of

these organisms should be a primary objective of ther

-

apy. In the therapy of opportunistic infections, how-

ever, elimination is not a realistic goal. Successfully

suppressed putative pathogens may grow back if fa-

vorable ecologic conditions (e.g. deep pockets) persist.

Continuous control of ecologic factors will be neces-

sary after initial treatment. Thus, therapy will not have

an unambiguously defined endpoint.

The periodontal flora never consists of one single

species. Frequently, several potential pathogens can

be identified at the same time, suggesting that inter-

actions between microorganisms play an important

role in the development of periodontal disease. The

pathogenicity of simultaneously present organisms

could be enhanced in an additive or synergistic way.

Antagonistic relationships between microorganisms

could, however, also occur. Based on the concept that

the presence of beneficial bacterial species may sup-

press the pathogenic impact of pathogens, one can

speculate that it may be advantageous to specifically

eliminate target bacteria only and to allow the growth

of potentially beneficial microorganisms. Such con-

templations have been used as an argument to propa

-

gate narrow spectrum antibiotics for periodontal ther-

apy

Drug delivery routes

Antimicrobial agents may be delivered by direct

placement into the periodontal pocket or via the sys-

temic route. Each method of delivery has specific

advantages and disadvantages (Table 23-1). Local

therapy may allow the application of antimicrobial

agents at levels that cannot be reached by the systemic

route. Local therapy may be particularly successful if

the presence of target organisms is confined to the

clinically visible lesions. On the other hand, systemi-

cally administered antibiotics may reach widely dis-

tributed microorganisms. Studies have shown that

periodontal bacteria may be distributed throughout

the whole mouth in some patients (Mombelli et al.

1991a, 1994), including non-dental sites, such as the

dorsum of the tongue or tonsillary crypts (Zambon et

al. 1981, Van Winkelhoff et al. 1988, Muller et al. 1993,

1995, Pavicic et al. 1994). Disadvantages of systemic

antibiotic therapy relate to the fact that the drug is

dissolved by dispersal over the whole body, and only

a small portion of the total dose actually reaches the

subgingival microflora in the periodontal pocket. Ad-

verse drug reactions are a greater concern and more

likely to occur if drugs are distributed via the systemic

route. Even mild forms of unwanted effects may se-

verely decrease patient compliance (Loesche et al.

1993). Local delivery is independent of patient com-

pliance.

Local drug delivery systems are means of drug

application to confined areas. For the treatment of

periodontal disease, local delivery of antimicrobial

drugs ranges from simple pocket irrigation, over the

placement of drug-containing ointments and gels, to

sophisticated devices for sustained release of antibac

-

terial agents. In order to be effective, the drug should

not only reach the entire area affected by the disease,

including the base of the pocket, but should also be

maintained at a sufficiently high local concentration

for some time. With a mouthrinse or supragingival

irrigation it is not possible to predictably deliver an

agent to the deeper parts of a periodontal defect (

Pitcher et al. 1980, Eakle et al. 1986). Agents brought

into periodontal pockets by subgingival irrigation are

washed out rapidly by the gingival fluid. Based on an

assumed pocket volume of 0.5 ml and a gingival fluid

flow rate of 20 µl/h, Goodson (1989) estimated that

the half-time of a non-binding drug placed into a

pocket is about 1 minute. Even a highly concentrated,

highly potent agent would thus be diluted below a

minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for oral mi-

croorganisms within minutes. If an agent can bind to

surfaces and be released in active form, a prolonged

498 • CHAPTER

23

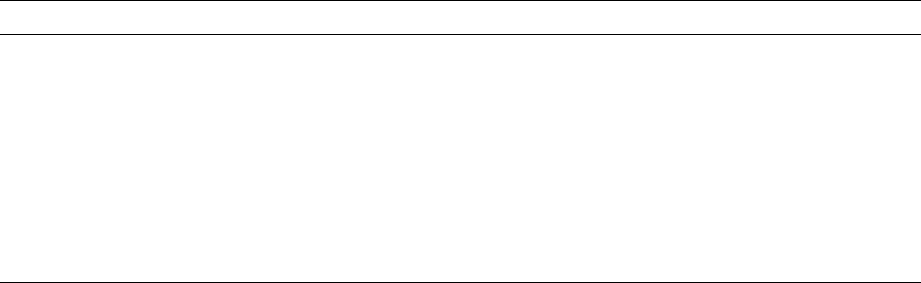

Fig. 23-3. An antimicrobial gel is applied with a syringe inserted into a residual pocket (a). For retention of the

agent in the site, the viscosity of the carrier should change immediately. A large portion of the product may

other

-wise be expelled from the pocket quickly (b).

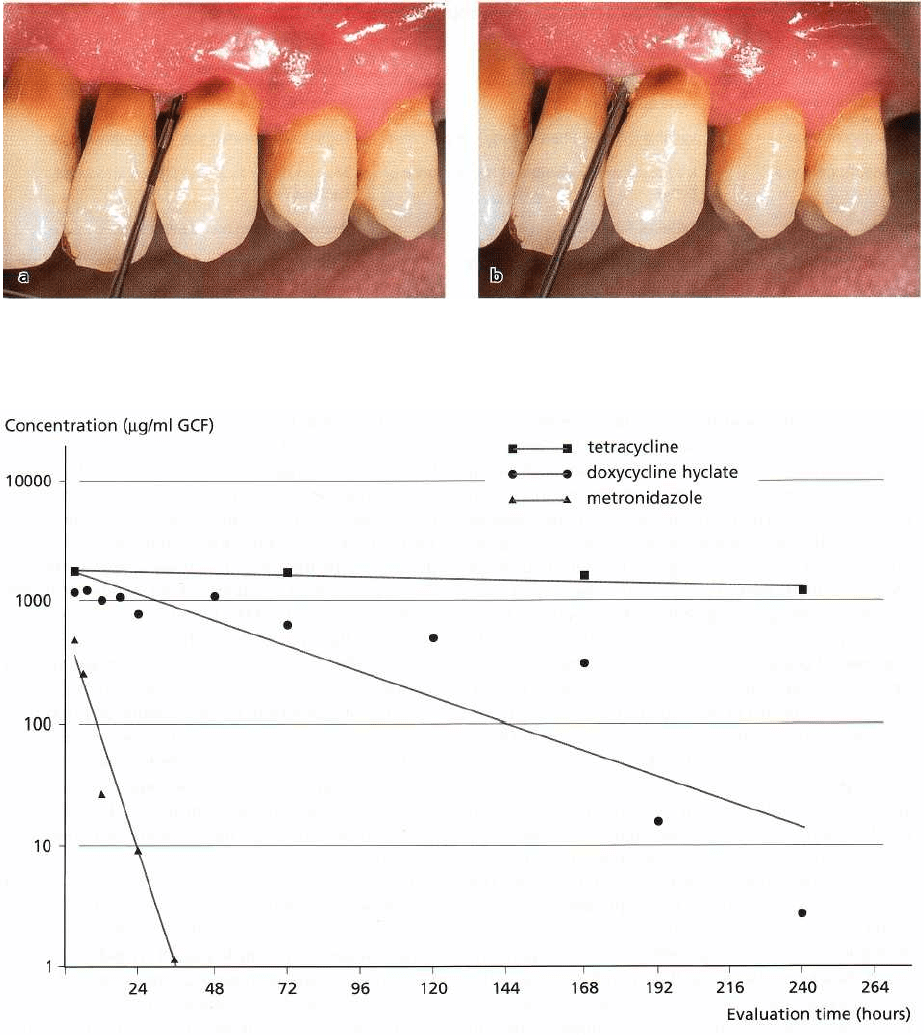

Fig. 23-4. Mean concentration of tetracycline in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) during tetracycline fiber treatment

(Tonetti et al. 1990), of doxycycline hyclate after application in a biodegradable polymer (Stoller et al. 1998), and of

metronidazole after application of 25% metronidazole dental gel (Stoltze 1992).

time of antibacterial activity could be expected. Such

an effect has in fact been noted for salivary concentra-

tions of chlorhexidine after use of chlorhexidine

mouthrinse (Bonesvoll & Gjermo 1978). Although

there

are indications that this may also occur to a

certain

extent within the periodontal pocket, for in-

stance after

prolonged subgingival irrigation with tet

racycline (

Tonetti et al. 1990), the potential to create a

drug

reservoir of significant size on the small surface area

available in a periodontal pocket is limited. To

maintain a high concentration over a prolonged pe

riod

of time, the flushing action of the crevicular fluid

flow has to be counteracted by a steady release of the

drug from a larger reservoir. Considering the small

volume of a periodontal pocket and the pressure ex-

erted by the tonus of the periodontal tissues on any-

thing inserted, it appears unlikely that this task can be

completed by a carrier that does not maintain its

physical stability for some time and that cannot be

secured against premature loss. Gels, for instance,

rapidly disappear after instillation into periodontal

pockets (Fig. 23-3a,b), unless they change their viscos-

ity immediately after placement (Oostervaal et al.

1990,

Stoltze 1995). Viscous and/or biodegradable de-

THE USE OF ANTIBIOTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY •

499

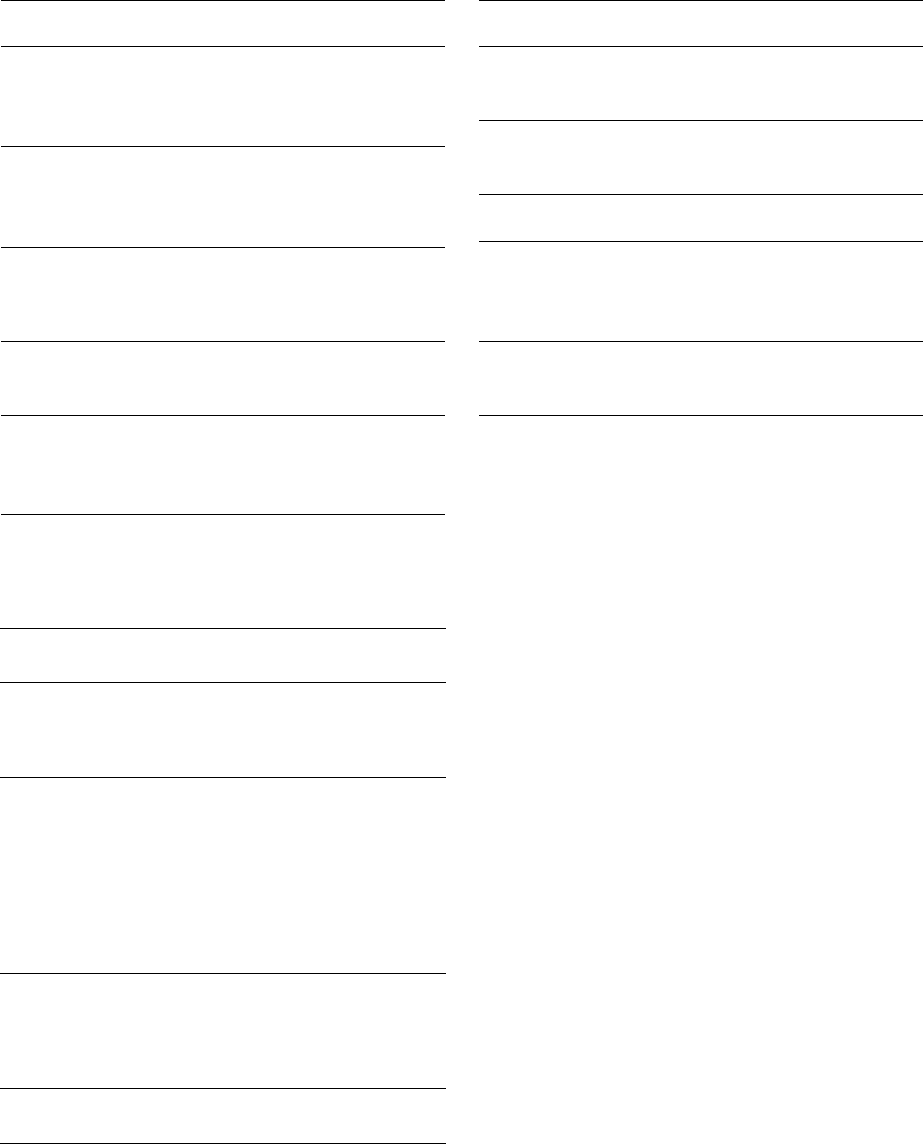

Table 23-2. Characteristics of antimicrobial agents used in the treatment of periodontal disease

(adapted from Lorian 1986, Slots & Rams 1990)

Antimicrobial agent

Dose

c Serum (pg/ml)c Crevicular fluid

tmax Serum (h)

Half-life (h)

(mg) (pg/ml)

Penicillin

500

3

ND

1

0.5

Amoxicillin

500 8

3-4

1.5-2 0.8-2

Doxycycline

200

2-3 2-8

2

12-22

Tetracycline

500

3-4

5-12

2-3 2-3

Clindamycin

150

2-3 1-2

1

2-4

Metronidazole

500

6-12 8-10

1-2

6-12

Ciprofloxacin

500

1.9-2.9

ND

1-2 3-6

c

concentration.

vices show an exponential decrease of their concentra

-

tion in gingival fluid. Depending on the physical and

chemical nature of the carrier, the drug reservoir in the

periodontal pocket will be depleted within hours to

days after placement. Controlled delivery of an an-

timicrobial agent over several days has been shown

for tetracycline released from non-degradable mono-

lithic ethylene vinyl acetate fibers (Fig. 23-4).

EVALUATION OF

ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS FOR

PERIODONTAL THERAPY

In the large range of antimicrobial agents, a limited

number have been tested thoroughly for use in peri-

odontal therapy. The drugs more extensively investi-

gated for systemic use include tetracycline, minocy-

cline and doxycycline, erythromycin, clindamycin,

ampicillin, amoxicillin, and the nitro-imidazole com-

pounds metronidazole and ornidazole. The drugs in-

vestigated for local application include tetracycline,

minocycline, doxycycline, metronidazole and chlor-

hexidine.

The first antibiotics used in periodontal therapy

were mainly systemically administered penicillins.

The choice was initially based on empirical evidence

exclusively. Penicillins and cephalosporins act by in-

hibition of cell wall synthesis. They are narrow-spec-

trum and bactericidal. Among the penicillins,

amoxicillin has been favored for treatment of peri-

odontal disease because of its considerable activity

against several periodontal pathogens at levels avail-

able in gingival fluid. The molecular structure of peni-

cillins includes a f3-lactam ring that may be cleaved by

bacterial enzymes. Some bacterial f3-lactamases have

a high affinity for clavulanic acid, a 13-lactam molecule

without antimicrobial activity. To inhibit bacterial [3-

lactamase activity, clavulanic acid has been added

successfully to amoxicillin. This combination (Aug-

mentin

®

) has been tested for periodontal therapy in

clinical studies. Tetracycline-HC1 became popular in

the 1970s due to its broad spectrum antimicrobial

activity and low toxicity. The tetracyclines, clindamy-

cin and erythromycin are inhibitors of protein synthe

-

sis. They have a broad-spectrum of activity and are

bacteriostatic. In addition to their antimicrobial effect,

tetracyclines are capable of inhibiting collagenase

(

Golub et al. 1985). This inhibition may interfere with

tissue breakdown in periodontal disease. Further-

more they bind to tooth surfaces, from where they may

be released slowly over time (Stabholz et al. 1993). The

nitro-imidazoles (metronidazole and ornidazole) and

the quinolone antibiotics (e.g. ciprofloxacin) act by

inhibiting DNA synthesis. Metronidazole is known to

convert into several short-lived intermediates after

diffusion into an anaerobic organism. These products

react with the DNA and other bacterial macromole-

cules, resulting in cell death. The process involves

reductive pathways characteristic of strictly anaerobic

bacteria and protozoa, but not aerobic or microaero-

philic organisms. Thus, metronidazole affects specifi-

cally the obligately anaerobic part of the oral flora,

including P.

gingivalis

and other black-pigmenting

Gram-negative organisms, but not A.

actinomycetem-

comitans,

a facultative anaerobe.

The concentrations following systemic administra-

tion of the most common antimicrobial agents used in

the treatment of periodontal disease are listed in Table

23-2. The

in vitro

susceptibility of A.

actinomycetem-

comitans

to selected antimicrobial agents is given in

Table 23-3 and the susceptibility of P.

gingivalis

is listed

in Table 23-4. The data given in these tables may serve

as a base for the choice of an appropriate agent. How-

ever, it is important to remember that

in vitro

tests do

not reflect the true conditions found in periodontal

pockets. In particular, they do not account for the

biofilm effect. One should add that MIC values de-

500 • CHAPTER

23

Table 23-3. Susceptibility of A.

actinomycetemcomi-

tans

to selected antimicrobial agents. MIC90: mini-

mal inhibitory concentration for 90% of the strains

(

adapted from Mombelli & van Winkelhoff 1997)

Antimicrobial

MIC90

Reference

agent

pg/ml

Penicillin

4.0

Pajukanta et al. (1993b)

1.0

Walker et al. (1985)

6.25

Hoffler et al. (1980)

Amoxicillin

1.0

Pajukanta et al. (1993b)

2.0

Walker et al. (1985)

1.6

Hoffler et al. (1980)

Tetracycline

0.5

Pajukanta et al. (1993b)

8.0

Walker et al. (1985), Walker

(1992)

Doxycycline

1.0

Pajukanta et al. (1993b)

3.1

Hoffler et al. (1980)

Metronidazole

32

Pajukanta et al. (1993b)

32

Jousimies-Somer et al. (1988)

12.5

HOffler et al. (1980)

Table 23-5. Adverse effects of antibiotics used in the

treatment of periodontal diseases

Antimicrobial

agent

Frequent effects

Infrequent effects

Penicillin

hypersensitivity

(mainly rashes),

nausea, diarrhea

hematological toxicity,

encephalopathy,

pseudomembranous

colitis (ampicillin)

Tetracycline

gastrointestinal

intolerance,

Candidiasis, dental

staining and

hypoplasia in

childhood, nausea,

diarrhea, interaction

with oral

contraceptives

photosensitivity,

nephrotoxicity,

intracranial

hypertension

Metronidazole

gastrointestinal

intolerance, nausea,

antabus effect,

diarrhea, unpleasant

metallic taste

peripheral neuropathy,

furred tongue

Clindamycin

rashes, nausea,

diarrhea

pseudomembranous

colitis, hepatitis

pend on technical details that may vary between labo

-

ratories. As a consequence, demonstration of

in vitro

susceptibility is no proof that an agent will work in

treatment of periodontal disease.

Since the subgingival microbiota in periodontitis

often harbors several putative periodontopathic spe-

Table 23-4. Susceptibility of

P.

gingivalis

to selected

antimicrobial agents (adapted from Mombelli & van

Winkelhoff 1997)

Antimicrobial

MIC90

Reference

agent

pg/ml

Penicillin

0.016

Pajukanta et al. (1993a)

0.29

Baker et al. (1983)

Amoxicillin

0.023

Pajukanta et al. (1993a)

< 1.0

Walker (1992)

Doxycycline

0.047

Pajukanta et al. (1993a)

Metronidazole

0.023

Pajukanta et al. (1993a)

2.1

Baker et al. (1983)

2.0

Walker (1992)

Clindamycin

0.016

Pajukanta et al. (1993a)

< 1.0

Walker (1992)

cies with different antimicrobial susceptibility, combi-

nation drug therapy may be useful. A combination of

antimicrobial drugs may have a wider spectrum of

activity than a single agent. Overlaps of the antimicro

-

bial spectrum may reduce the possible development

of bacterial resistance. For some combinations of

drugs there may be synergy in action against target

organisms, allowing a lower dose of the single agents.

A synergistic effect against A.

actinomyceternconhitans

has been noted

in vitro

between metronidazole and its

hydroxy metabolite (Jousimies-Sourer et al. 1988,

Pavicic et al. 1991) and between these two compounds

and amoxicillin (Pavicic et at. 1992). With some drug

combinations there may, however, also be antagonistic

drug interaction. For instance, bacteriostatic agents

such as tetracyclines, which suppress cell division,

decrease the antimicrobial effect of bactericidal antibi

-

otics such as (3-lactam drugs or metronidazole, which

act during bacterial cell division. Combination drug

therapy may also lead to increased adverse reactions.

Table 23-5 lists common adverse reactions to sys-

temic antibiotic therapy (for a detailed overview the

reader is referred to Walker 1996). The penicillins are

among the least toxic antibiotics. Hypersensitivity re-

actions are by far the most important and most com-

mon adverse effects of these drugs. Most reactions are

mild and limited to a rash or skin lesion in the head or

neck region. More severe reactions may induce swel-

ling and tenderness of joints. In highly sensitized

patients a life-threatening anaphylactic reaction may

develop. The systemic use of tetracyclines may lead to

epigastric pain, vomiting or diarrhea. Tetracyclines

can induce changes in the intestinal flora, and super-

infections with non-bacterial microorganisms (i.e.

Candida albicans)

may emerge. Tetracyclines are depos

-

ited in calcifying areas of teeth and bones where they

THE USE OF ANTIBIOTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 501

cause yellow discoloration. Systemic administration

of clindamycin may be accompanied by gastrointesti

-

nal disturbances, leading to diarrhea or cramps and

may cause mild skin rashes. The suppression of the

normal intestinal flora increases the risk for coloniza

-

tion of

Clostridium difficile,

which may cause a severe

colon infection. Although not related to C.

difficile,

gastrointestinal problems are also the most frequent

adverse event of systemic metronidazole therapy.

Nausea, headache, anorexia, vomiting may be experi

-

enced. Symptoms may be more pronounced with al-

cohol consumption, because imidazoles affect the ac

-

tivity of liver enzymes. Because some cases have de-

veloped permanent peripheral neuropathies (numb-

ness or paresthesia), patients should be advised to

immediately stop therapy if such symptoms occur.

Systemic antimicrobial therapy in clinical

trials

As mentioned before, the ultimate evidence for the

efficacy of systemic antibiotics must be obtained from

treatment studies in humans with periodontitis. Be-

cause compromises are often necessary to conduct an

investigation under given clinical, technical or finan-

cial circumstances, a large number of studies reported

in the literature can be criticized using the basic study

quality criteria for evidence-based medicine. Studies

may be difficult to interpret and compare due to an

unclear status of patients at baseline (treatment his-

tory, disease activity, composition of subgingival mi-

crobiota), insufficient or non-standardized mainte-

nance after therapy, short observation periods, or lack

of randomization and controls. Studies not only vary

with regard to the treatment provided, but also in the

selection of subjects, sample size, range of study pa-

rameters, outcome variables, the duration of the study,

and the controls to which the test procedure is com-

pared. In most studies, systemic antibiotics have been

used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing. Typi-

cally, the effect of mechanical therapy plus the antimi

crobial agent has been compared to mechanical treat

-

ment alone. In studies evaluating the effect of antimi

-

crobial therapy in patients with refractory periodon-

titis or with recurrent abscess formation, placebo con

-

trol is often lacking for ethical reasons.

Chronic and

aggressive

periodontitis in

the adult

patient

Several case reports claimed clinical success with

tet-

racycline

therapy; however, in placebo controlled tri-

als, only slight differences were noted in the change of

mean probing depths and attachment levels between

patients receiving tetracycline or placebo as an ad-

junct to mechanical therapy (Listgarten et al. 1978,

Hellden et al. 1979, Slots et al. 1979, Scopp et al. 1980,

Lindhe et al. 1983).

Systemic

metronidazole

in conjunction with scaling

and root planing yielded slightly better results than

scaling alone (Clark et al. 1983, Lekovic et al. 1983,

Lindhe et al. 1983, Joyston-Bechal et al. 1984, 1986,

Loesche et al. 1984, Soder et al. 1990). No improvement

in clinical effects of therapy was found in patients

receiving metronidazole in conjunction with peri-

odontal surgery over surgery alone (Sterry et al. 1985,

Mahmood & Dolby 1987). In rapidly progressive pe-

riodontitis, metronidazole seemed to improve clinical

conditions for up to 6 months compared to periodon-

tal scaling alone (Soder et al. 1989, 1990).

A limited number of patients with advanced adult

periodontitis were treated with

clindamycin

without

concurrent mechanical therapy, except oral hygiene

instructions. Despite this limited treatment regimen,

clinical and microbiologic parameters improved over

the following 6 months.

P.

gingivalis

appeared to be

particularly susceptible to clindamycin therapy; this

species was no longer detected at 6 months. Other

organisms, however, were resistant to clindamycin

and were found at slightly higher levels after 6 months

(Ohta et al. 1986).

Haffajee et al. (1995) examined the effects of sys-

temic amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, tetracycline

HC1, or placebo therapy, given for 30 days in conjunc

-

tion with subgingival debridement and modified

Widman flap surgery, in adults with progressive peri-

odontitis. Significantly greater mean gains in clinical

periodontal attachment and decreased probing

depths

were measured at 10 months post-treatment in

subjects receiving adjunctive systemic amoxicillin

plus clavulanic acid or tetracycline therapy as com-

pared to the placebo regimen. Although decreases in

numbers of subgingival putative periodontal patho-

gens paralleled the marked clinical improvements, no

pathogen was eliminated from the subgingival micro-

biota.

Metronidazole plus amoxicillin, Augmentin or

ciprofloxacin have been used successfully in the treat

-

ment of advanced A.

actinomycetemcomitans

associated

periodontitis (Christersson et al. 1989, Kornman et al.

1989, van Winkelhoff et al. 1989, 1992, Goene et al.

1990, Pavicic et al. 1992, 1994, Rams et al. 1992). These

combinations markedly suppressed or even elimi-

nated A.

actinomycetemcomitans

and other subgingival

organisms from periodontitis lesions and other oral

sites.

Serial drug regimens studied to date in periodon-

tics include systemic

doxycycline

administered in-

itially and followed by either

amoxicillin

plus clavu-

lanic acid or

metronidazole

(Aitken et al. 1992, Matisko

& Bissada 1992). The sequential use of drugs over-

comes the potential risk of antagonism between bac-

teriostatic and bactericidal antibiotics. The value of

serial antibiotic therapy in the management of ad-

vanced periodontitis merits further investigation.

Conclusion

In general, adult periodontitis can and should be

treated without systemic antibiotics. The adjunctive

use of antibiotics in adult periodontitis should be

502 • CHAPTER 23

limited to cases with advanced or progressive disease.

A. actinornycetemcomitans

associated periodontitis

may

be treated with adjunctive metronidazole plus

amoxicillin.

"Refractory" periodontitis

A beneficial effect of

tetracycline

therapy was reported

in several studies in adult patients with "refractory"

periodontitis. Double blind studies showed signifi-

cant reductions in probing pocket depth with systemic

tetracycline (Rams & Keyes 1983, McCulloch et al.

1989, 1990).

McCulloch et al. (1990) selected patients on the

basis of periodontal disease activity; active disease

was defined as loss of clinical attachment or abscess

formation. In this study,

doxycycline,

administered for

3 weeks, reduced probing pocket depths significantly

more than placebo and resulted in more gain of clinical

attachment, however, only at sites with evidence of

recent disease activity. The doxycycline regimen re-

duced the relative risk for subsequent periodontal

breakdown over a 7-month period by 43%. Even

though adjunctive doxycycline therapy was effective

in some active periodontitis patients, it failed to pre-

vent periodontal breakdown in 13 of 29 individuals.

Recurrent disease activity after systemic tetracycline

therapy was also reported by other authors (van

Winkelhoff et al. 1989, Goene et al. 1990, Aitken et al.

1992, Walker et al. 1993). Disease progression may

have been caused by subgingival organisms not suffi-

ciently suppressed by the doxycycline therapy. A.

act-

inomycetemcomitans

and E.

corroders

were not mark-

edly suppressed in the doxycycline treated patients

(

McCulloch et al. 1990) and the difference in the com-

position of the subgingival microbiota between the

placebo and doxycycline patients was not significant

after 7 months (McCulloch et al. 1990, Kulkarni et al.

1991). Other studies have also pointed to a possible

failure of systemic tetracycline in the suppression of

subgingival A.

actinornycetemcomitans

(Muller et al.

1989, 1993, van Winkelhoff et al. 1989). In some in-

stances an increase of this organism was even noted

(

Muller et al. 1990). Furthermore, systemic tetracy-

cline therapy may lead to colonization of superinfect-

ing and opportunistic pathogens (Bragd et al. 1985,

Haffajee et al. 1988, Hull et al. 1989). It may thus be

speculated that non-antimicrobial effects, such as col

-

lagenase inhibition, may have been more important

for the observed outcome than the antibiotic action

(

Golub et al. 1983, 1985).

Systemic

clindamycin

and scaling yielded a signifi-

cant improvement in patients treated for active peri-

odontal disease despite previous conventional peri-

odontal treatment and systemic tetracycline therapy

(

Gordon et al. 1985). The clinical effects were associ-

ated with significant reductions of spirochetes, motile

rods and Gram-negative anaerobic rods, including P.

gingivalis

and

P. intermedia,

and an increase of Gram-

positive rods and cocci over 1-2 years (Walker & Gor-

don 1990). However, clindamycin did not perma

nently suppress subgingival

P. gingivalis,

which may

explain the recurrence of disease activity in some pa-

tients. It should also be mentioned that one study

patient developed pseudomembraneous colitis, a gas

-

trointestinal superinfection by

Clostridium difficile

which may be life-threatening.

In one study, refractory adult periodontitis patients,

who in the past had been subjected to periodontal

surgery, systemic tetracycline administration and sup

portive periodontal therapy, were retreated with

scal

ing and root planing in conjunction with either

clin

damycin or amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid (

Magnus

-

son et al. 1994). The two systemic

antimicrobial therapies were prescribed on the basis

of the susceptibility

of the whole subgingival

microbiota (Walker et al.

1983). Over a 2-year

evaluation period, the difference

in the proportions of

sites losing attachment following

either clindamycin

or amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid

therapy was not

significant.

Statistically significant improvements in clinical

parameters have also been observed after mechanical

debridement combined with systemic metronidazole

and ornidazole in patients with recurrent periodontal

disease (Gusberti et al. 1988, Mombelli et al. 1989).

Conclusion

Various antibiotic regimens have been tested for the

treatment of patients not responding to conventional

periodontal therapy. Favorable short term effects have

been reported; however, a great variability in treat-

ment response among patients has been noted. Re-

emergence of putative pathogens has been observed

and has been considered the reason for recurrence of

disease.

Aggressive

localized periodontitis

Reduced gingival inflammation, gain of clinical at-

tachment and alveolar bone were reported following

tetracycline therapy in juvenile patients with aggres-

sive localized periodontitis (Slots et al. 1979, Genco et

al. 1981, Lindhe 1982, Slots & Rosling 1983). However,

as many as 25% of juvenile periodontitis patients

treated with tetracycline may experience a reactiva-

tion of disease, even if their dentition is professionally

cleaned every 3 months after therapy (Lindhe 1982).

Further destruction of periodontal attachment was

noted in sites with high post-treatment levels of A.

actinomyceternconzitans

(Slots & Rosling 1983, Korn-

man & Robertson 1985, Mandell & Socransky 1988,

Asikainen et al. 1990, Saxen & Asikainen 1993). Sup

-

pression of A.

actinornycetemcomitans

does not seem

possible in all aggressive localized periodontitis le-

sions with scaling and root planing and adjunctive

systemic tetracycline.

Suppression of A.

actinornycetemcomitans

has been

reported for up to 18 months in juvenile patients with

aggressive localized periodontitis after mechanical

debridement plus metronidazole (200 mg TID, 10

days). In comparison, systemic tetracycline therapy or

mechanical treatment alone eliminated A.

actinomy-

THE USE OF ANTIBIOTICS IN PERIODONTAL THERAPY • 503

cetemcomitans

in only 44% and 67% of the juvenile

periodontitis patients, respectively (Saxen & Asi-

kainen 1993). Considering the limited effect of

metronidazole on facultative organisms, documented

in

in vitro

susceptibility tests (Walker et al. 1985), these

results are quite surprising. The hydroxy metabolite

of metronidazole may be responsible for the suppres-

sion of subgingival

A. actinomycetemcomitans

(Jousim-

ies-Somer et al. 1988, Pavicic et al. 1992). The success

ful use of metronidazole plus amoxicillin in the

treat

ment of various cases with advanced A.

actinomy-

cetemcomitans

associated periodontitis suggests the

adjunctive use of this combination may also be a good

choice for aggressive localized periodontitis in juve-

nile patients (Christersson et al. 1989, Kornman et al.

1989, van Winkelhoff et al. 1989, 1992, Goene et al.

1990, Pavicic et al. 1994).

Conclusion

Several regimens including the adjunctive admini-

stration of tetracyclines or metronidazole have been

tested for the treatment of localized juvenile periodon

-

titis. Again, re-emergence of putative pathogens, in

this case of A.

actinonnycetenrcomitans,

has been ob-

served and has been considered the reason for recur

-

rence of disease. Metronidazole in combination with

amoxicillin may suppress A.

actinoniycetemcomitans

more efficiently than single antibiotic regimens.

Implications for clinical

practice

Overall, it can be stated that systemic antibiotic ther

-

apy may improve the microbiologic and clinical con-

ditions of periodontal patients under certain circum-

stances. Monotherapy with systemic antibiotics as an

adjunct to mechanical periodontal treatment can sup

-

press the total subgingival bacterial load and may

induce a significant change in the composition of the

subgingival microbiota. However, antibiotic therapy

with single antimicrobial agents cannot predictably

eliminate periodontal organisms such as A.

actinomy-

cetemcomitans.

To

reach this goal, combination therapy,

i.e. metronidazole plus amoxicillin, seems to be more

appropriate. There is evidence to support the use of

systemic antibiotic therapy in cases of

P.

gingivalis

and/or A.

actinann/cetemcomitans

associated early on-

set forms of periodontitis. Systemic antibiotic therapy

is also indicated in generalized refractory periodonti-

tis patients with evidence of ongoing disease despite

optimal mechanical therapy.

It is biologically sound and good medical practice

to base systemic antimicrobial therapy on appropriate

microbiologic data. In addition, antibiotics should not

be administered systemically before completion of

thorough mechanical debridement (patients with

acute signs of disease such as periodontal abscesses,

or acute necrotizing gingivitis, with fever and malaise,

may be the exception). Therefore, in most cases, the

initial mechanical therapy should be carried out and

evaluated before microbiological testing. The original

treatment plan, may be modified six to twelve weeks

after initial therapy, taking into account how the peri

-

odontal tissues reacted to the non-specific reduction

of the bacterial mass by root instrumentation and oral

hygiene. Microbial samples from the deepest pocket

in each quadrant can give a good picture of the pres-

ence and relative importance of putative pathogens in

the oral flora (Mombelli et al. 1991b, 1994). Microbial

testing should be comprehensive and sensitive

enough to determine the presence and relative pro-

portion of the most important periodontal organisms.

Since the antimicrobial profiles of most putative peri-

odontal pathogens are quite predictable, susceptibil-

ity testing is not routinely performed. One should

keep in mind, however, that some important microor

-

ganisms may demonstrate resistance to tetracyclines,

(3-lactam drugs or metronidazole. It is recommended

to start drug administration immediately following a

mechanical re-instrumentation. In practical terms this

often means that the patient commences antibiotic

therapy in the evening after the last surgical proce-

dure. Even if no further mechanical therapy is indi-

cated from a clinical point of view, the pockets should

be re-instrumented to reduce the subgingival bacterial

deposits as much as possible and to disrupt the sub-

gingival biofilm.

After resolution of the periodontal infection, the

patient should be placed on an individually tailored

maintenance care program. Optimal plaque control by

the patient is of paramount importance for a favorable

clinical and microbiologic response to systemic an-

timicrobial therapy (Kornman et al. 1994).

Local antimicrobial therapy in clinical trials

A variety of methods to deliver antimicrobial agents

into periodontal pockets have been devised and sub-

jected to numerous kinds of experiments. The phar-

macokinetic shortcomings of rinsing, irrigating and

similar forms of drug placement, and the lack of sig-

nificant clinical effects have already been discussed.

This section will deal with clinically tested drug de-

livery systems that fulfill at least the basic pharmacok

inetic requirements of sustained drug release. Much

of what has been stated about difficulties in the inter

-

pretation of studies dealing with the systemic use of

antibiotics applies to the studies conducted with local

delivery devices. Again, comparison of various forms

of therapy is complicated because studies vary with

regard to sample size, selection of subjects, range of

parameters, controls, duration of the study, and the

inclusion of only one form of local drug delivery. Most

of the evidence for a therapeutic effect of local delivery

devices comes from trials involving patients with pre-

viously untreated adult periodontitis. Some protocols

compare local drug delivery to a negative control,

such as the application of only the carrier without the

drug. These studies may be able to show a net effect

of the drug, but they are not able to demonstrate a

benefit over the most obvious alternative – scaling and

504

• CHAPTER 23

root planing — and the question remains as to how

much value the procedure has

in addition

to mechani-

cal treatment. If a study is unable to demonstrate a

significant difference between local drug delivery and

scaling and root planing, this is not automatically a

proof of equivalence of the two treatments. Equiva-

lence testing requires statistical testing of the power of

the data, taking into account the size of the study

sample. Only very few studies have addressed the use

of local drug delivery in recurrent or persistent peri-

odontal lesions — the potentially most valuable area

for their application. The following paragraphs dis-

cuss the predominant products available today for

local antimicrobial therapy. Further developments

currently under

way

will undoubtedly lead to the

commercial availability of additional products in the

future.

Minocycline ointment and microspheres

A 2%

minocycline

ointment (Dentomycin; Cyanamid,

Lederle Division, Wayne, NJ, US) has been distributed

commercially in some countries for several years. The

efficacy of this product has been assessed in a series of

clinical trials mainly conducted in adult patients in

Japan. In a randomized, double-blind study of 103

adults with moderate to severe periodontitis, the

safety and efficacy of subgingivally applied 2% mino-

cycline ointment was tested at four Belgian universi-

ties (van Steenberghe et al. 1993). All patients were

treated by conventional scaling and root planing at

baseline. In addition, the patients received either the

test or a control ointment in four consecutive sessions

at an interval of two weeks (baseline and 2, 4, 6).

Assessment of clinical response was made at weeks 4

and 12. A significantly greater reduction of probing

depth was observed in the test group. An additional

multicenter study evaluated the long-term safety and

efficacy of subgingivally administered minocycline

ointment when used intermittently as an adjunct to

subgingival debridement in chronic periodontitis.

The

repeated subgingival administration of minocycline

ointment yielded an adjunctive improvement

after

subgingival instrumentation in both clinical and

microbiologic variables over a 15-month period (van

Steenberghe et al. 1999). One study assessed the effect

of a weekly repeated local application of minocycline

ointment for 8 weeks after placement of expanded

polytetrafluoroethylene membranes to guide regen-

eration of periodontal tissue. Although bacterial colo-

nization of treated sites could not be prevented, the

mean clinical attachment gain of the test group was

significantly greater than that of the control group

(

Yoshinari et al. 2001).

The subgingival delivery of minocycline in differ

ent

forms, for example in bioabsorbable 10% minocy-

cline-loaded microcapsules, has also been investi-

gated. Proof of principle studies involving relatively

small numbers of patients with chronic periodontitis

indicated that such local subgingival delivery systems

may reduce bleeding on probing better than scaling

and root planing alone and may induce a microbial

response more favorable for periodontal health than

scaling and root planing (Yeom et al. 1997). The effi-

cacy and safety of locally administered microencapsu

-

lated minocycline was assessed in a multicenter trial

including 748 patients with moderate to advanced

periodontitis. Minocycline microspheres plus scaling

and root planing provided substantially more probing

depth reduction than either scaling and root planing

alone or SRP plus vehicle. The difference reached

statistical significance after the first month and was

maintained throughout the 9 months of the trial (Wil

-

liams et al. 2001).

Doxycycline hyclate

in a

biodegradable polymer

A two syringe mixing system for the controlled release

of doxycycline

(Atridox; Block Drug, Jersey City, NJ,

US) has been evaluated in a number of investigations,

and has become available commercially in several

countries. Syringe A contains the delivery vehicle,

which is a bioabsorbable, flowable polymeric formu-

lation composed of poly(DL-lactide) dissolved in N-

methyl-2-pyrrolidone, and syringe B contains 50 mg

of doxycycline hyclate. The constituted product con-

tains 10% w/w doxycycline hyclate. The clinical effi-

cacy and safety of Atridox was compared to placebo

control, oral hygiene, and scaling and root planing in

two multicenter studies. Each study entered 411 pa-

tients who demonstrated moderate to severe adult

periodontitis. Comparisons showed the treatment to

be statistically superior to placebo control and oral

hygiene and equally effective as scaling and root plan

-

ing in reducing the clinical signs of adult periodontitis

over a 9-month period (Garrett et al. 1999). Clinical

changes resulting from local delivery of doxycycline

hyclate or traditional scaling and root planing were

evaluated in a group of patients undergoing suppor-

tive periodontal therapy. Attachment level gains and

probing depth reductions were similar at 9 months

after therapy (Garrett et al. 2000).

The effect of Atridox, applied after no more than 45

minutes of debridement without analgesia in subjects

with moderately advanced chronic periodontitis, was

compared to 4 hours of thorough deep scaling and

root planing in a study involving 105 patients at three

centers. Interestingly clinical parameters indicated a

better result for the pharmaco-mechanical treatment

approach after 3 months, although considerably less

time had been invested than for conventional me-

chanical therapy (Wennstrom et al. 2001).

Metronidazole gel

Dialysis tubing, acrylic strips, and poly-OH-butyric

acid strips have been tested as solid devices for deliv

-

ery of

metronidazole.

The most extensively used device

for metronidazole application is a gel consisting of a

semi-solid suspension of 25% metronidazole benzoate

in a mixture of glyceryl mono-oleate and sesame oil

(

Elyzol Dental Gel; Dumex, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Applied with a syringe inserted into the pocket, the