Jung Han. Innovations in Food Packaging

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Modified atmosphere packaging of ready-to-eat foods

203

Foods

(K.

R.

Cadwallader and H. Weenen, eds), pp. 270-291. ACS Symposium

Vol. 836, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

Spencer, K. C. and Rojak, P. A. (1993). Method of preserving foods using noble gases.

Intl Patent Publ. WO

93/19629.

Spencer, K. C. and Steiner,

E.

F.

(1997). Method of disinfecting fresh vegetables by

processing the same with

a liquid containing a mixture of argon:carbon dioxide.

US Patent 5,693,354.

Spencer, K. C., Schvester, P. and Boisrobert, C.

E.

(1995). Method for improving enzyme

activities with noble gases. US Patent 5,462,861.

Spencer,

K. C., Schvester,

F!

and Boisrobert, C. E. (1998). Method for regulating enzyme

activities by noble gases. US Patent 5,707,842.

Stiles, M. E. (1991). Scientific principles of controlled/modified atmosphere packaging.

In:

ModiJied Atmosphere Packaging of Food

(B. Ooraikul and M.

E.

Stiles, eds),

pp. 18-25. Ellis Horwood Ltd, Chichester, UK.

Stone, H. and Sidel,

J.

L.

(1993).

Sensory Evaluation Practices,

2nd edn., pp. 118-147.

Academic Press, New York,

NY.

Preservative packaging

for

fresh

meats,

poultry, and fin

fish

Alexander

0.

Gill and Colin

0.

Gill

Introduction ............................................................. 204

Preservation of meat appearance

.............................................

207

Preservation or development of desirable eating qualities.

..........................

21

1

Delay

of

microbial spoilage.

.................................................

21

3

Microbiological safety.

.....................................................

218

Summary

............................................................... 220

References

...............................................................

220

Introduction

The aim of any packaging system for fresh muscle foods is to prevent or delay unde-

sirable changes to the appearance, flavor, odor, and texture. Deterioration in these

qualities can result

in

economic losses due to consumer rejection of the product.

The appearance of fresh muscle foods greatly affects the purchasing decisions of

consumers (Cornforth,

1994).

Products that appear dull or discolored are generally

considered undesirable, and will be rejected when products that look fresh can be

obtained. Thus, a preservative packaging that accelerates irreversible discoloration of

a

muscle food product is unsuitable for use with that product, irrespective of the other

preservative effects of the packaging.

During the storage of raw muscle foods at chiller temperatures, various enzyrne-

mediated and non-enzymic chemical reactions will affect the flavor, odor, and texture

of the tissues. The changes produced by some of the enzymic reactions are desirable

-

for example, the increased tenderness of aged beef (Jeremiah

et

al.,

1993).

However,

most of the changes caused by enzymic activities are undesirable. Therefore, a pre-

servative packaging should ideally inhibit undesirable enzymic activities, but not

interfere with, or inhibit, activities that are beneficial. The non-enzymic reactions that

affect the organoleptic qualities of raw meats are invariably undesirable, so these

should preferably be slowed or prevented by a preservative packaging.

Innovations in Food Packaging

ISBN:

0-12-31 1632-5

Copyright

O

2005 Elsevier Ltd

All

rights of reproduction

in

any

form reserved

Preservative packaging for fresh meats, poultry, and

fin

fish

205

The rates of chemical reactions, whether or not they are catalyzed by enzymes,

and the rates of bacterial growth increase with increasing temperature. However,

the increase in rate with increasing temperature will differ for different processes,

and may differ for the same process in different products. That being so, a statement

of a storage life for a raw muscle tissue product is only meaningful if both the type

of deterioration that renders the product unacceptable and the storage temperature

are identified. Otherwise, the reported storage life provides no information of gen-

eral value.

As most changes during storage of raw muscle foods are undesirable, and changes are

slowed by decreasing temperature, it follows that the optimum temperature for storing

raw muscle products is the minimum that can be indefinitely maintained without the tis-

sue freezing. That temperature is in practice

-

1.5

+

0.5"C (Gill

et

al.,

1988). For proper

understanding of product storage stability under different circumstances, it is desir-

able that consideration be given to the storage life at the optimum temperature, as well

as at temperatures that might be encountered during storage, distribution, and display.

In addition to the preservative effects, the commercial function of the packaging

must be considered. The cost of a packaging is obviously a matter of major commer-

cial concern. A relatively expensive packaging that confers extended storage stability

is unlikely to be adopted when a storage life adequate for a market can be obtained

with a cheaper, less effective packaging. Different forms of packaging may be

required, depending on whether the packaging will be used for retail display of the

product, or only for storage and distribution before further fabrication andor repack-

aging. If the conditions during storage and distribution are known and consistent, a

less robust packaging system is required than when conditions are uncertain. It is then

apparent that the commercially optimal packaging need not be the packaging that

confers the greatest storage stability on a product.

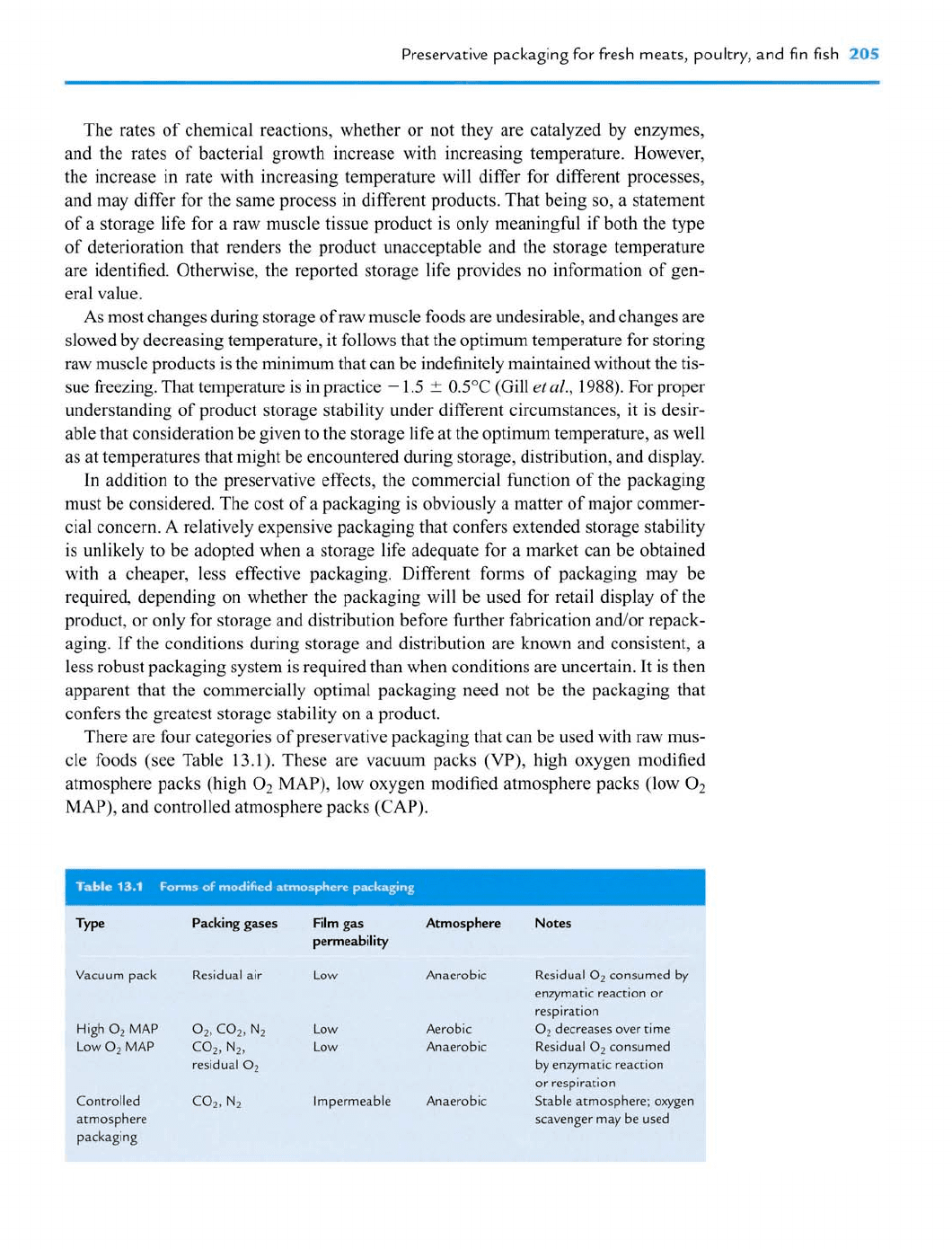

There are four categories of preservative packaging that can be used with raw mus-

cle foods (see Table 13.1). These are vacuum packs

(VP),

high oxygen modified

atmosphere packs (high O2

MAP),

low oxygen modified atmosphere packs (low O2

MAP), and controlled atmosphere packs (CAP).

Packing gases Film gas Atmosphere

pemeability

'acuum pack Residual air Low Anaerobic

iigh

0,

MAP

02,

C02, N2

Low Aerobic

ow

O2

MAP

C02, N2,

Low Anaerobic

residual

O2

:ontrolled

(32,

N2

Impermeable Anaerobic

tmosphere

backaging

Notes

Residual

O2

consumed by

enzymatic reaction or

respiration

O2

decreases over time

Residual

O2

consumed

by enzymatic reaction

or respiration

Stable atmosphere; oxyger

scavenger may be used

nnovations in

Food

Packaging

Vacuum packs comprise evacuated pouches and vacuum skin packs, in which a film

of low gas permeability is closely applied to the surface of the product. Preservative

effects are achieved by the development of an anaerobic environment within the pack.

Residual oxygen in any remaining atmosphere or dissolved in the product

is removed by enzymic reactions of the muscle tissue, or other chemical reactions

with tissue components. As the capacity of the muscle tissue for removing oxygen is

limited, the amount of oxygen remaining in the pack at the time of closure must be

very small if the product is to be effectively preserved. This will not be the case if the

shape of the product units gives rise to bridging of the film, or otherwise allows

vacuities to be formed within the pack. Items themselves that encompass spaces, such

as whole carcasses, cannot be reliably preserved in

VF?

Bone-in items also present dif-

ficulties for

VP,

as bone ends can puncture packaging films. Though puncture-resistant

materials to cover bone ends may be used, they complicate the packaging process,

may not be consistently effective, and will certainly increase packaging costs.

High O2 MAPS contain atmospheres of oxygen and carbon dioxide and, often,

nitrogen. Only oxygen and carbon dioxide have preservative effects. However, carbon

dioxide is highly soluble in both muscle and fat tissues (Gill, 1988), while oxygen

may be respired by tissues and bacteria an4 at high initial concentrations, will tend to

be lost through the packaging film. Consequently, nitrogen is often included in high

O2 MAP atmospheres as an inert filler, to guard against pack collapse. Because of the

interactions between the preservative gases and the product, a large gas-volume to

product-weight ratio is required if an atmosphere adequate for preservation is to be

maintained.

An

atmosphere of

3

llkg of product is probably necessary for extended

storage (Holland, 1980). Even so, it is usually found that, after the initial dissolution

of carbon dioxide in the product, the carbon dioxide contents of high O2 MAP atmos-

pheres change little while the oxygen concentration progressively decreases (Nortje

and Shaw, 1989).

Low O2 MAPS contain atmospheres of carbon dioxide and nitrogen usually with

some residual atmospheric oxygen remaining in the pack at the time of closure. As

nitrogen has no preservative function in low O2 MAP atmospheres, the initial volume

of the pack atmosphere need only be sufficient to allow for dissolution of carbon diox-

ide in the product without pack collapse and crushing of the product. Low O2 MAP

atmospheres may be supplemented with carbon monoxide at concentrations less than

0.5% for the purpose of imparting a cherry-red color to the meat (Smheim

et al.,

1999).

CAPS contain atmospheres that do not change during storage of the product. To

achieve this, the films used for such packaging must have very low, preferably

immeasurable, gas permeability (Kelly, 1989). CAP atmospheres may contain carbon

dioxide and/or nitrogen. If carbon dioxide is used, the initial gas volume must be suf-

ficient to allow for dissolution of carbon dioxide in the product. As an anoxic atmos-

phere is required for product preservation, but complete removal of oxygen is not

practicable, oxygen scavengers may be used to accelerate the removal of residual oxy-

gen from the pack atmosphere (Doherty and Allen, 1998). Otherwise, the residual

oxygen is removed by reactions with product components.

The specific attributes of different raw meat tissues determine which of these vari-

ous packaging systems is best suited for preservation.

Preservative packaging for fresh meats,

poultry,

and fin fish

207

Preservation of meat appearance

Red

meats

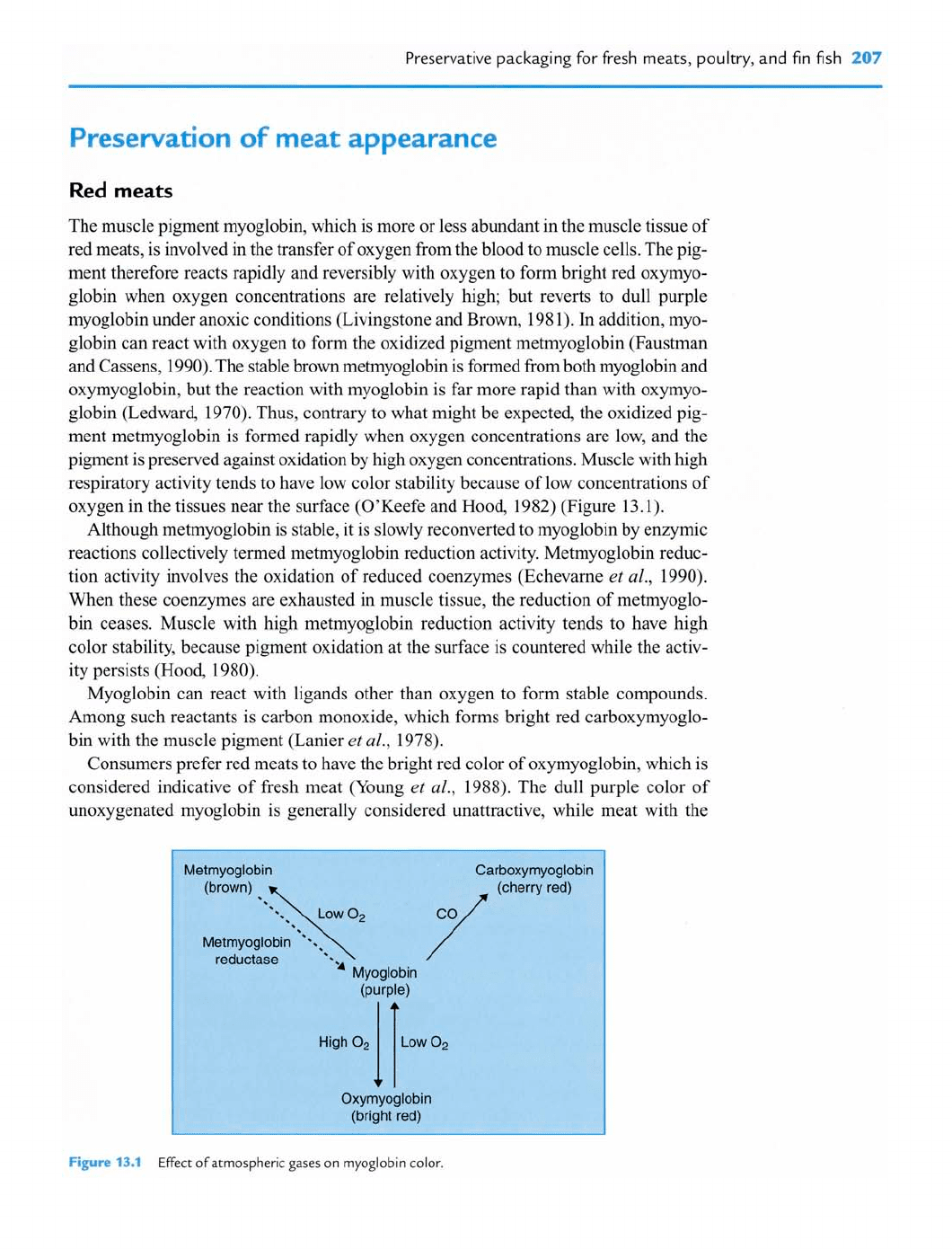

The muscle pigment myoglobin, which is more or less abundant in the muscle tissue of

red meats, is involved in the transfer of oxygen from the blood to muscle cells. The pig-

ment therefore reacts rapidly and reversibly with oxygen to form bright red oxymyo-

globin when oxygen concentrations are relatively high; but reverts to dull purple

myoglobin under anoxic conditions (Livingstone and Brown, 1981). In addition, myo-

globin can react with oxygen to form the oxidized pigment metmyoglobin (Faustman

and Cassens, 1990). The stable brown metmyoglobin is formed from both myoglobin and

oxymyoglobin, but the reaction with myoglobin is far more rapid than with oxymyo-

globin (Ledward, 1970). Thus, contrary to what might be expected, the oxidized pig-

ment metmyoglobin is formed rapidly when oxygen concentrations are low, and the

pigment is preserved against oxidation by high oxygen concentrations. Muscle with high

respiratory activity tends to have low color stability because of low concentrations of

oxygen in the tissues near the surface (O'Keefe and Hood, 1982) (Figure 13.1).

Although metmyoglobin is stable, it is slowly reconverted to myoglobin by enzymic

reactions collectively termed metmyoglobin reduction activity. Metmyoglobin reduc-

tion activity involves the oxidation of reduced coenzymes (Echevarne

et

al., 1990).

When these coenzymes are exhausted in muscle tissue, the reduction of metmyoglo-

bin ceases. Muscle with high metmyoglobin reduction activity tends to have high

color stability, because pigment oxidation at the surface is countered while the activ-

ity persists (Hood, 1980).

Myoglobin can react with ligands other than oxygen to form stable compounds.

Among such reactants is carbon monoxide, which forms bright red carboxymyoglo-

bin with the muscle pigment (Lanier

et

al., 1978).

Consumers prefer red meats to have the bright red color of oxymyoglobin, which is

considered indicative of fresh meat (Young

et

al., 1988). The dull purple color of

unoxygenated myoglobin is generally considered unattractive, while meat with the

Qxymyoglobin

(bright

red)

Fipa

13.1

Effect of atmospheric gases on myoglobin color.

208

Innovations in Food Packaging

brown color of metmyoglobin is often considered unacceptable (Renerre, 1990).

Ideally, packaging for red meats should preserve a desirable red color for the muscle

tissue. If this is not possible, the packaging must prevent the product from being

grossly discolored by the formation of metmyoglobin during storage, so that the prod-

uct will retain the ability to bloom to a bright red color when it is displayed.

Vacuum packaging is widely used with primal cuts and ground red meats. During

the relatively short times for storage and national or continental distribution of

VP

meat (Gill

et

al., 2002), the muscle tissue will not usually discolor and the meat will

retain the ability to bloom when VPs are opened. Color, and the ability to bloom, is

often retained as well during the longer times required for surface freighting of meat

to overseas markets (Gill, 1989). However, materials used for

VP

are usually not

wholly gas impermeable, so oxygen that diffuses into the pack will react with pack

contents. When pockets of exudate form in packs, as is usual during prolonged stor-

age, the incoming oxygen can oxidize myoglobin in the exudate, which may then pre-

cipitate onto and discolor meat surfaces (Jeremiah

et

al., 1992).

After storage for two or three weeks, respiration and metmyoglobin reduction activ-

ity have usually been lost by muscle tissue (O'Keefe and Hood, 1980-81). Therefore,

after that time the color stability of different muscles is similarly low and comparable

with the color stability of ground meat, in which metmyoglobin reduction activity is

destroyed by the grinding process (Madhavi and Carpenter, 1993). Thus meat that has

been stored in

VP

for two weeks or more is likely to discolor more rapidly when dis-

played than is meat of a lesser age.

Exposed spongy bone of bone-in cuts that have been stored in

VP

is also likely to

darken and even blacken rapidly after the meat is exposed to air because of the oxida-

tion of haemoglobin from the bone marrow (Gill, 1990). Haemoglobin is released

from red cells that disintegrate as storage is extended. The accumulation of the oxi-

dized pigment at cut bone surfaces gives rise to much darker colors than those that

develop at spongy bone surfaces of fresh cut meat.

The use of VP with consumer cuts offered for retail sale has generally been unsuc-

cessful because of the unattractive color of anoxic muscle tissue, although

VP

primal

cuts are apparently saleable at retail. Attempts to remedy this situation by packing

meat in vacuum-skin packs, from which the gas-barrier film can be stripped to expose

a gas-permeable film before the meat is displayed, have also met with little commer-

cial success. The lack of success might be due to the high costs of such packaging, but

it might also be due to consumer uncertainty about packaging unlike that traditionally

used with fresh meats.

In contrast, high O2

MAP

is now widely used with consumer cuts of red meats. Gas

mixtures containing 50-70% oxygen are used to fill not only lidded trays containing

consumer cuts but also master packs, which each contain several packs of consumer

cuts in conventionally over-wrapped trays (Gill and Jones, 1994a). In lidded trays the

input gas is likely to be diluted with

<

5%

residual

air.

However, master packs are usually

formed by withdrawing air from filled pouches, through snorkels inserted into each

pouch, for a set time before filling the pouch with a gas mixture, also for a set time.

The withdrawing of air must cease before the pouch collapses around and crushes the

retail trays, but the extent to which the pouches are filled with product and air varies.

Preservative packaging for fresh meats, poultry, and

fin

fish

209

Thus more or less large volumes of air are inevitably present in master packs when the

preservative gas is added, and so the initial concentrations of both oxygen and carbon

dioxide in master pack atmospheres are often well below the concentrations in the

input gas. Thus, in practice, master pack atmospheres may do little to preserve red

meat color, but will protect overwrapped trays from mechanical damage during their

distribution to retail outlets from central cutting facilities.

Provided that pack atmospheres contain concentrations of oxygen well above that

present in air, the fraction of myoglobin in the form of oxymyoglobin and the depth of

the oxygenated layer will both be greater than in air (Taylor, 1985). The desirable red

color of the meat will thus be intensified.

In

commercial practice, the initial enhance-

ment of meat color, rather than extension of storage life, may be the principal benefit

sought from packaging in lidded trays with high oxygen atmospheres.

If the oxygen concentration in the pack atmosphere is maintained, the formation of

metmyoglobin at the meat surface can be retarded sufficiently to prolong the acceptable

appearance for two to three times longer than in air (Renerre, 1989). Discoloration of

the product is the factor that usually limits the storage life of red meats in high

O2

MAP,

since bacterial spoilage is delayed by the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (Gill

and Jones, 1994b).

Because metmyoglobin forms rapidly at the surfaces of red meats exposed to low

concentrations of oxygen, low

O2

MAP

is generally not used with red meats. How-

ever, an acceptable color for red meats in low

O2 MAP

can be preserved if a small

fraction of carbon monoxide, usually

<

0.5%, is present in the input gas (Smheim

et

al., 1999). Carbon monoxide binds rapidly and essentially irreversibly with myo-

globin to confer a permanent red color to the product. As carbon monoxide has a

strong affinity for, and prevents the proper functioning of the oxygen transporting pig-

ments of both blood and muscle, the gas is highly toxic. Consequently, most regula-

tory authorities concerned with food safety do not allow carbon monoxide to be used

with meat. However, it has been shown that the risks to consumer health from the

small amounts of carbon monoxide associated with meat are likely trivial (Sarrheim

et

al., 1977). The use of carbon monoxide with red meats is permitted in Norway;

where lidded trays of retail-ready red meats are commonly filled with a gas mixture

containing 60% carbon dioxide, 40% nitrogen, and about 0.4% carbon monoxide

(Sarrheim

et

al., 1999).

The deterioration of red meat color during storage can be wholly prevented if oxygen

is completely excluded from the pack atmosphere. This can be achieved by packaging

meat in a gas-impermeable film, such as a laminate composed of two layers of metal-

lized material, and filling the pack with carbon dioxide or nitrogen to obtain a CAP.

A major problem that arises in the use of CAP with red meats is the removal of

residual air, as any remaining oxygen will react rapidly with the unoxygenated myo-

globin to grossly discolor the product. In practice, very low concentrations of oxygen

in the pack atmosphere at the time of pack closure can be achieved by evacuating a pouch

through snorkels with the pack beneath a hood which is simultaneously evacuated

(Gill, 1990). Partial breaking of the vacuum within the hood before the pouch is filled

with gas allows the pack volume to be minimized before gassing, without crushing the

contained product or retaining pockets of air between items that are pressed together.

210

Innovations in Food Packaging

When such packaging procedures are used, the oxygen content of the initial pack

atmosphere can be kept to a few hundred parts per million. However, if the volume of

the atmosphere is relatively large compared to the product volume, which it must be

if a high carbon dioxide atmosphere is used, then the amount of residual oxygen may be

sufficient to cause extensive discoloration (Gill and McGinnis, 1995a). Discoloration

may be mitigated or prevented by the inclusion of oxygen scavengers in a pack, but

for these to be effective they must rapidly strip oxygen from the atmosphere as the

muscle tissue itself is a very effective oxygen scavenger (Gill and McGinnis, 1995b).

Although discoloration of the meat immediately after pack closure may be unavoid-

able, that need not present a problem if the meat is fresh and it is stored for longer

than

two or three days. In those circumstances, the metmyoglobin formed as oxygen was

stripped from the atmosphere is reconverted to myoglobin by the metmyoglobin reduc-

tion activity of the muscle tissue. Provided the amount of metmyoglobin formed does

not exceed the metmyoglobin reducing capacity of the muscle, no metmyoglobin will be

present in the muscle tissue after storage for a few days (Gill and Jones, 1996). Then,

when the meat is exposed to air it will bloom to the bright red color of freshly cut meat.

CAP is used for red meat products that must be preserved for periods beyond those

attainable with

MAP

but for which

VP

is ineffective or inappropriate. Examples of such

products are whole lamb carcasses surface-freighted to overseas markets, or retail packs

of sheep meats widely distributed in the USA from a few central cutting facilities.

Poultry

The concentrations of myoglobin in poultry muscle are generally low, while rates of

oxygen consumption are high (Millar

et

al., 1994). As a result, poultry muscle

exposed to air does not exhibit the bright red color of oxymyoglobin; instead it has the

duller tones imparted by metmyoglobin and the unoxygenated pigment. Of course,

consumers find that usual color of the meat wholly acceptable. There is therefore no

benefit in packing poultry in high O2

MAP,

and that type of packaging is not used with

poultry in commercial practice.

Because the appearance of poultry is unaffected by anaerobic conditions, or low

concentrations of oxygen in pack atmosphere, all other forms of preservative pack-

aging are usable with poultry for storage or display.

Fish

There are two distinctly colored forms of muscle in fin fish; white muscle and dark

muscle (Love, 1988). White muscle, which usually forms the greater part of the mus-

cle present in a fish, contains low concentrations of myoglobin. Dark muscle, which is

used for continuous movement, is rich in haem pigments, predominantly myoglobin. In

most species of commercially exploited fin fish, the dark muscle is localized in a band

running under the skin along the

flank

of the fish. The proportion and distribution of

dark muscle varies between species, and is related to the type of swimming activity of

each (Love

et

al., 1977).

Preservative packaging for fresh meats, poultry, and fin fish

211

Though changes in the form of myoglobin will occur in fish muscle packaged in VP

or low O2 MAP, this has little effect on the appearance and acceptability to consumers

of fish in which there is little dark muscle (Silva and White, 1994; Hong

et

al., 1996).

The exception is fish with high dark muscle content, such as active predators like tuna.

In those fish the distinct red color of dark muscle is considered attractive, so preser-

vation of the red color is desirable. The dark muscle in fillets of such fish discolors, as

does other red muscle tissue, and discoloration can be retarded or prevented by pack-

aging in VP, CAP, or high O2 MAP (Oka, 1989). It should be noted that, due to the

localization of dark muscle, it may not be visible to the consumer in whole fish and

certain fillet cuts. The effects of packaging on the appearance of dark muscle may then

have little effect on the acceptability of some forms of fish, even when dark muscle is

present.

With fish such as salmon, in which the intense color of the muscle tissue is due

to carotenoid pigments assimilated from the fishes' food, any colors imparted by

the muscle pigment are immaterial. Carotenoid colors are unaffected by VP; but

colors may become lighter during prolonged storage in atmospheres with high carbon

dioxide concentrations (Randell

et

al., 1999).

Consumer acceptance of whole fish is dependent on the appearance of tissues

other than muscle. The appearance of such features as belly flaps, gills, and cornea

of the eye has been reported to be adversely affected by high C02 atmospheres

(Chen

et

al., 1984; Haard, 1992). However, no deterioration in the appearance of

whole salmon was observed with 100% C02 by Sivertsvik

et

al. (1999). Low concen-

trations of carbon monoxide can be used to preserve gill color in anoxic atmospheres,

but the same regulatory difficulties that limit its use in red meats exist (Rosnes

et

al., 1998).

To avoid the pack collapse and possible bleaching of muscle which may occur with

high concentrations of carbon dioxide, high O2 MAP is often used with lean fish

(Gibson and Davies, 1995). Even so, the effects ofVP and low O2 MAP on the appear-

ance of fish can be small, and the appearance of most fish is not greatly enhanced by

the inclusion of O2 in pack atmosphere (Dhananjaya and Stroud, 1994). There appears

to be no use of CAP with fresh fish, perhaps because of the supposed adverse effects

of high concentration of carbon dioxide. However, fatty fish are packaged in low O2

MAP, with input gases containing up to 80% COz, apparently without adverse effects

on the appearance of product (Sivertsvik

et

al., 2002).

Preservation or development

of

desirable

eating qualities

Red

meats

Both the texture and the flavor of meat may alter during storage. Consumer percep-

tions of the eating qualities of red meats are largely determined

by

the tenderness of

the muscle tissue (Jeremiah

et

al.,

1993).

Various intrinsic and extrinsic factors affect

---

.

nnovations in Food Packaging

the tenderness of muscle tissue (Dransfield, 1994). Among these is the increase of

tenderness with aging. The tenderizing of beef with time in storage does not appar-

ently continue indefinitely, but after peaking starts to decline exponentially with time.

Maximum tenderization is attained after two or three weeks (Dransfield, 1994).

Preservative packaging appears to have little effect on the rate or extent of tenderizing

with age.

Although tenderness in beef may not increase after the first few weeks of storage,

lamb stored for prolonged periods in

VP

may lose texture and develop an undesirable,

meal-like consistency. Moreover, in both lamb and beef the breakdown of proteins

with the release of peptides and free amino acids continues during extended storage

in

VP

(Rhodes and Lea, 1961). The accumulation of proteolysis products imparts bit-

ter and liver-like flavors to the meat, which many consumers find undesirable. The

deterioration of texture and flavor during prolonged storage of lamb does not occur

when the meat is in

CAP

with a carbon dioxide atmosphere (Gill, 1989). The storage

life of red meats in high O2 MAP is too short for any deleterious effects of proteoly-

sis to become evident.

The flavor of meat can also be adversely affected by lipid oxidation, which gives

rise to rancid and stale odors and flavors. The susceptibility of lipids to oxidation

depends upon the degree of unsaturation of the fatty acid residues in the lipid mole-

cules (Lillard, 1987). Oxidation is accelerated by pro-oxidants such as ferric ions, and

is inhibited by antioxidants such as vitamin E (Lillard, 1987). Generally, red meats

contain less polyunsaturated fatty acids than poultry or fish, and so develop oxidative

rancidity relatively slowly (Allen and Foegeding, 198 1).

As lipids are not oxidized in the absence of oxygen, rancidity generally does not

develop in red meats in VP or

CAP.

The increased concentration of oxygen in high O2

MAP might be expected to accelerate lipid oxidation in red meats, but rates of lipid

oxidation were found to be similar in pork stored under oxygen-rich atmospheres or

air (Ordonez and Ledward, 1977). However, grinding of red meat can greatly acceler-

ate lipid oxidation, and ground red meats may develop rancid odors and flavors more

rapidly in high O2 MAP than in air (Sinchez-Escalante

et

al.,

2001).

Poultry

The pre-slaughter handling of birds and the method of carcass processing substan-

tially affect the tenderness of poultry meat (Jones and Grey, 1989). Tenderizing pro-

ceeds rapidly after the development of rigor, with 80% of the maximum tenderness

being attained within a day (Dransfield, 1994). Thus, tenderizing during storage is not

a factor of much importance for the eating quality of poultry meats.

The oxidative rancidity is accelerated in the meat of birds fed on diets high in

polyunsaturated fatty acids, and is more rapid in dark leg meat than in white breast

meat from the same carcass (Lin

et

al.,

1989). However, the development of rancidity

in poultry meats will be inhibited by the low levels or lack of oxygen in preservative

packaging for poultry. In such packaging, the storage life of poultry meats is usually

determined by microbial spoilage.