Li S.Z., Jain A.K. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Biometrics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

‘‘track-sure’’: i.e., they continued to follow the specific

person in spite of chan ges in direction, ground sur-

face, and obstacles, in spite of other people having

crossed the path earlier or later. Such dogs could also

identify the person that had laid that track. This setup

is still followed today in the basic training of blood-

hounds all over the world. However, a more formalized

manner of working with dogs identifying human odors

has also evolved, primarily in Europe.

This formalized methodology is called ‘‘ sc ent identi-

fication line-up,’’ or ‘‘ osmology’’, and is applied as a

forensic identification tool in several European countries.

Dogs are trained to match the odor of a sample to its

counterpart in an array of odors. This can be done in

different ways [1, 2]. Generally the dog is given a scent

sample from a crime scene that presumably contains

the odor of the perpetrator. The odor of the suspect

and a number of foils, collected in a standardized

manner, are offered to the dog as the array. The dog

has to match the crime-scene related odor to that of

the suspect in the array, and indicate its choice w ith a

learned response. The methods and materials used to

collect human odor differ between countries; the exact

protocol for working with the dog differs; quality con-

trol measures necessary to validate the correctness of

the outcome differ; and the way in which the results are

evaluated and used during investigation and trial differ

between countries too. In spite of efforts to harmonize

these differences, they still exist since there is little

scientific evidence to select the ‘‘best’’ way: dogs per-

form best when tested in the way they were trained,

and much depends on how the dogs were sele cted and

trained.

From the little scientific work done using dogs

in this field, it became clear that dogs are capable of

matching odors collected from different body parts

[3, 4]. The series of experiments conducted by Schoon

and de Bruin [3], showed that trained police dogs

were capable of matching objects (stainless steel tubes)

held in the pocket or in the crook of the arm to

objects held by hand and vice versa significantly better

than chance, but that their performance was a lot better

on the comparison they trained often (pocket to hand:

58% correct in a 1 out of 6 comparison) than on a

comparison they never trained (crook elbow to hand;

hand to crook elbow: 32% correct in a 1 out of 6

comparison). Settle [4] had people scenting objects

(pieces of gauze) on numerous body parts and also

found dogs could match those that had been handled

by the same person significantly be tter than chance

(60% correct in a 1 out of 6 comparison). However,

the gauzes they used were stored together per person in

a glass jar prior the experiments with the dog, so they

may have all reached an equilibrium in this jar. Hepper

[5] found that dogs use odor cues that are under

genetic control more than those under environmental

control. He let dogs match the odor of T shirts of

fraternal and identical twins with identical or different

diets. When both diet and genes were identical, the

dogs could not differentiate between the twins (1 out

of 2 comparisons). When the genes were identical but

the diets differed, the dogs were able to differentiate

between the twins but they took a long time and their

choices were not very sure (83.5% correct in a 1 out of

2 comparison). When the genes were different but the

diets identical, the dogs performed best and made their

choices quickly and surely (89% correct in a 1 out of

2 comparison).

W ith advancing technology in the second half of

the twentieth century, an effort was made to identify

the source and composition of the body secretions that

made it possible for dogs to actually identify people

based on their odor. The human skin can be divided

into two layers: the outer la yer called the epidermis and

the inner layer called the dermis. The dermis layer con-

tains most of the specialized excretory and secretory

glands. The dermis layer of the skin contains up to

5 million secretory glands including eccrine, apocrine

and sebaceous glands [6]. Bacterial breakdown of apo-

crine secretions result in a huge number of volatile

compounds in armpits [7–9], but for forensic purposes

the breakdown of sebaceous gland sec retions is more

interesting since these products can be found on

crime-related objects such as guns, knives, crowbars,

gloves etc. Further study showed that trained dogs

are capable of matching objects scented by the same

person at different times but that their performance

was lower [10

].

Instrumental Differentiation Body

Scent

The individual body odors of humans are determined

by several factors that are either stable over time (ge-

netic factors) or vary with environmental or internal

conditions. The authors have developed distinguishing

terminology for these factors: the ‘‘primary odor’’ of an

1010

O

Odor Biometrics

individual contains constituents that come from with-

in and are stable over time regardless of diet or envi-

ronmental factors; the ‘‘secondary odor’’ contains

constituents which also come from within and are

present due to diet and environmental factors; and

the ‘‘tertiary odor’’ contains constituents which are

present because they were applied from the outside

(i.e., lotions, soaps, perfumes, etc.) [9]. There is a

limited understanding of how the body produces

the volatile organic compounds present in human

scent. Although the composition of human secre-

tions and fingerprint residues have been evaluated

for their chemical composition [6, 7], comparatively

little work has been done to determine the volatile

organic compounds present in human scent. Know-

ing the contents of human sweat may not accurately

represent the nature of what volatile compounds

are present in the headspace above such samples

which constitute the scent.

With the use of gas chromatography-mass spec-

trometry, an increasing number of volatiles were iden-

tified in the headspace of objects handled by people

[11]. Investigations into the compounds emitted by

humans that attract the Yellow Fever mosquito have

provided insight into the compounds present in

human odor. Samples were collected using glass

beads that were rolled between fingers. The beads

were then loaded into a GC and cryofocused by liquid

nitrogen at the head of the column before analysis

with

▶ GC/MS. The results showed more than 300

observable compounds as components of human

skin emanations, including: acids, alcohols, aldehydes,

and alkan es. The results also showed qualitative

similarities in compounds between the individuals

studied, however, quantitati ve differences were also

noted [11].

Until recently, technological limitations have re-

stricted the ability of researchers to identify the chemi-

cal components that comprise human scent without

altering the sample or to use the information to chem-

ically distinguish between individuals. In addition, it

has been difficult to distinguish between primary, sec-

ondary, and tertiary odor components in a collected

human scent sample.

▶ Solid phase micro-extraction

(SPME) is a simple solvent-free headspace extraction

technique which allows for

▶ volatile organic com-

pounds (VOCs) present in the headspace (gas phase

above an item) to be sampled at room temperature.

SPME in conjunction with GC/MS has been demon-

strated to be a viable route to extract and analyze the

VOCs present in the headspace of collected human

secretions. In a recent study, the hand odor of 60

subjects were studied (30 males and 30 females) and

63 human compounds extracted, there was a high

degree of variability observed with six high frequency

compounds, seven medium frequency compounds,

and 50 low frequency compounds among the popu-

lation. The different types of compounds determined

to be present in a human hand odor profile inclu-

ded acids, alcohols, aldehydes, alkanes, esters, ketones,

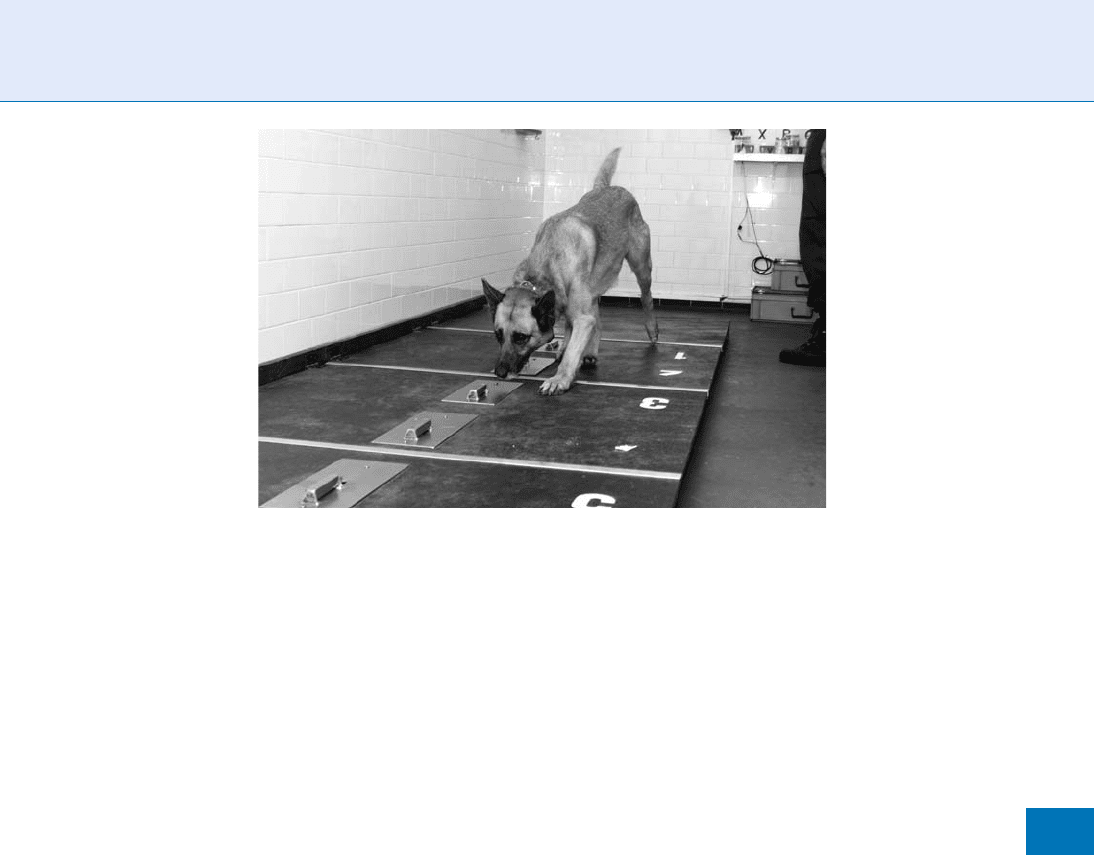

Odor Biometrics. Figure 1 Dog searching for a matching odor in a Dutch scent identification line-up (photo courtesy of

the Netherlands National Police Agency).

Odor Biometrics

O

1011

O

and nitrogen containing compounds. It has been

demonstrated that nonparametric methods of correla-

tion can be employed to differentiate between VOC

patterns from different individuals. In the 60 subject

study, it was shown that Spearman Rank Correlation

coefficient comparisons of human odor compounds

among individuals is a viable me thod of data handling

for the instrumental evaluation of the volatile organic

compounds present in collected human scent samples,

and that a high degree of distinction is possible among

the population studied [12]. Using a match/no-match

threshold of 0.9 produces a distinguished ability of

99.7% across the population. Other work also sho-

wed that multiple samples taken from the same per-

son showed that these could not be distinguished

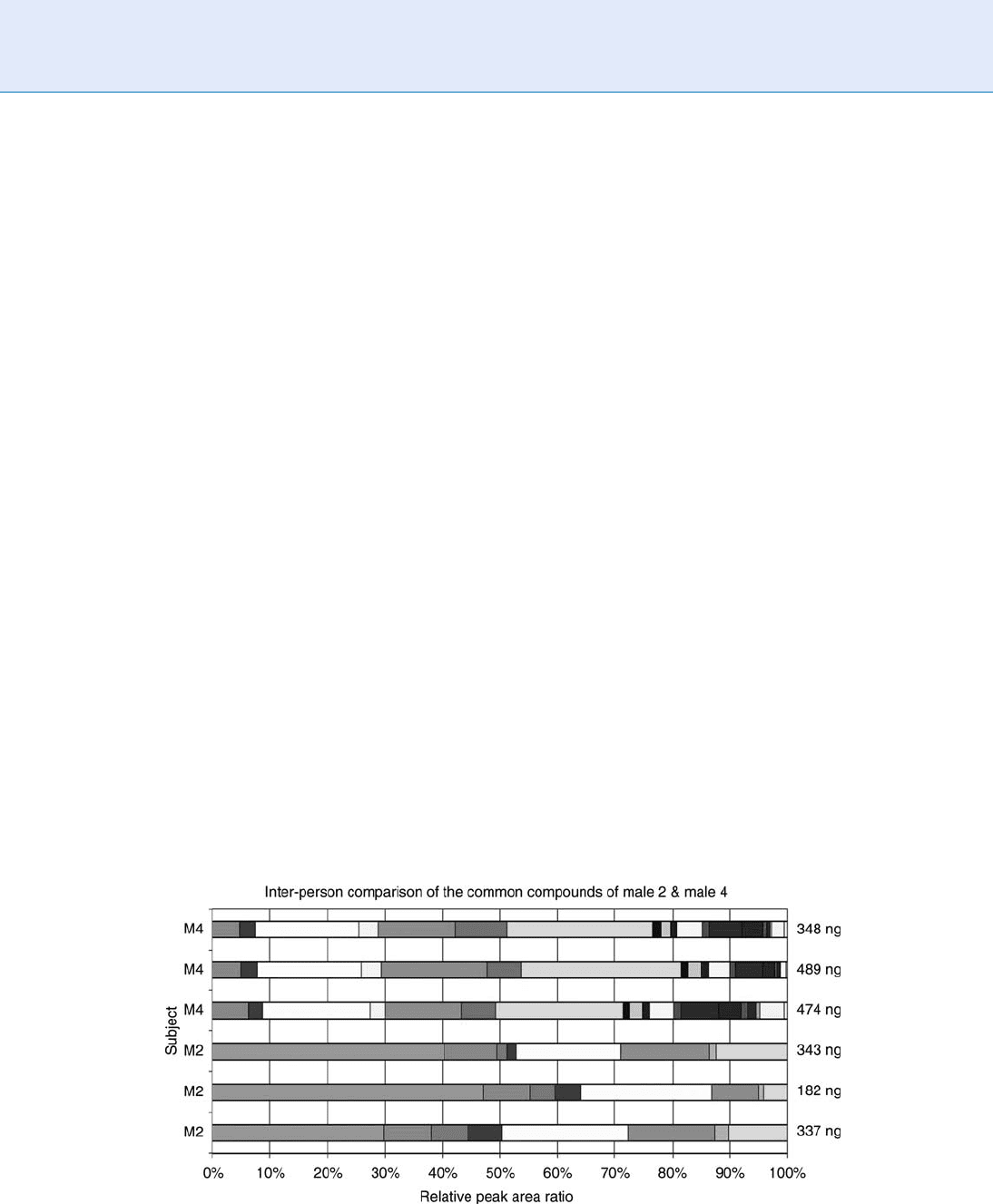

at the sam e level. Fig ure 2 illustrate s the variation

of the VOC patterns in multiple samples from two

different males.

The genetic source of these specific human volatiles

has also been investigated. Experimental work with

dogs had already indicated a link to the genes of a

person, and work with rats and mice had located the

genes of the Major Histocompatibility Complex

(MHC) as the source of variation. The genetic basis

for individualizing body odors has been studied exten-

sively in genetically engineered mice which differ in

respect to the genes present in the MHC [13]. MHC

exhibits a remarkable genetic diversity with resulting

from a variety of characteristics including a level of

heterozygosity approaching 100% in natural popula-

tions of mice. This high level of heterozygosity seems

to be maintained by behavioral factors including mat-

ing success and associated with olfactory cues, and

chemosensory imprinting. In humans, the MHC is

referred to as the HLA, which is a short for human

leucocyte antigen. Experiments utilizing trained rats

have shown that urine odors of defined HLA-homozy-

gous groups of humans can be distinguished [13].

Individual body scents of mice can be altered by mod-

ification of genes within the MHC. Alterations to the

individual body scents of mice result in changes in the

concentrations of the volatile components found in

the urine [14]. Using two-dimensional GC/MS Willse

et al. were able to detect differences in the several dozen

MHC compounds (including 2,5-dimethylpyrazine

and 2-sec-butyl-4,5-dihydrothiazole) found in ether-

extracted urine from two inbred groups of mice that

differed only in MHC genes.

Legal Perspectives on Human Odor for

Forensic Purposes

In Europe, scent identification lineups have been used

routinely by police forces, for example in Poland and

The Netherlands, and the results have been the subject

of discussion and different interpretations in court. In

Poland Wo

´

jcikiewicz [15] summarized a number of

court cases where dog evidence was critically reviewed.

Generally, the evidence was accepted by Polish courts

as ‘‘additional evidence,’’ thus allowing the results to be

used only if convergent with other evidence; a point

Odor Biometrics. Figure 2 Illustration of the variety in volatile organic compounds as collected by SPME and determined

by GC-MS from three samples of two human subjects. Each color is a different VOC.

1012

O

Odor Biometrics

of view of Wo

´

jcikiewicz, given the limited scientific

background knowledge at that time. In the Nether-

lands, scent lineup evidence has been the subject of

much debate over the years. A recent case confirmed

that results from carefully conducted scent identifica-

tion lineups can be used as an addition to other evi-

dence [16]. In the absence of the other evidence, a

positive result of such a lineup is regarded as insuffi-

cient evidence for conviction.

The twenty-first century has brought with it two

important case decisions in the United States Court

System pertaining to the use of human scent canines in

criminal prosecutions. In 2002, the U.S. Court System

decided human scent canine associations could be

utilized through the introduction of expert witness

testimony at trial if the canine teams were shown to

be reliable [17]. In 2005, a Kelley hearing in the state of

California [18] set a new precedent in the U.S. which

allowed human scent identi fication by canine to be

admitted as forensic evidence in court as opposed

to being presented as expert witness testimony. The

California court ruled that human scent discrimina-

tion by canine can be admitted into court as evidence

if the person utilizing the technique used the correct

scientific procedures, the training and expertise of the

dog-handler team is proven to be proficient, and

the methods used by the dog handler are reliable.

Summary

The scientific studies to date support the theory that

there is sufficient variability in human odor between

persons and reproducibility of primary odor com-

pounds from individuals that human odor is a viable

biometric that can be use d to identify persons. The

bulk of the available literature is based on the ability of

training dogs to identify objects held by a specific

person but advancing technology has recently made it

possible to differentiate humans based on headspace

analysis of objects they have handled supporting the

results seen with dogs. With additional research and

development on training and testing protocols w ith

the dogs, and instrumental methods, the future of

human odor as an expanded biometric is quite

promising. In addition, unlike many other biometrics,

human scent can be detected from traces, such as skin

rafts, left by a person and can be collected in a nonin-

vasive fashion.

Related Entries

▶ Human Scent and Tracking

▶ Individuality

References

1. Schoon, A., Haak, R.: K-9 suspect discrimination: Training and

practicing scent identification line-ups. Detselig, Calgery, AB,

Canada (2002)

2. Schoon, G.A.A.: Scent identification line-up by dogs (Canis

Familiaris): Experimental design and forensic application.

Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 49, 257–267 (1996)

3. Schoon, G.A.A., De Bruin, J.C.: The Ability of dogs to recognize

and cross-match human odours. Forensic Sci. Int. 69, 111–118

(1994)

4. Settle R.H., Sommerville, B.A., McCormick, J., Broom, D.M.:

Human scent matching using specially trained dogs. Anim.

Behav. 48(6), 1443–1448 (1994)

5. Hepper, P.G.: The discrimination of human body odour by the

dog. Perception 17(4), 549–554 (1998)

6. Ramotowski, R.S.: Comparison of latent print residue.

In: Lee, H.C., Gaensslen, R.E. (eds.) Advances in Fingerprint

Technology, 2nd edn. pp. 63–104. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

(2001)

7. Shelley, W.B., Hurley, H.J. Jr., Nichols, A.C.: Axillary odor:

Experimental study of the role of bacteria, apocrine sweat

and deodorants. AMA Arch. Derm. Syphilol. 68(4), 430–446

(1953)

8. Sommerville, B.A., Settle, R.H., Darling, F.M., Broom, D.M.: The

use of trained dogs to discriminate human scent. Anim. Behav.

46, 189–190 (1993)

9. Curran, A.M., Rabin, S.I., Prada, P.A., Furton, K.G.: Comparison

of the volatile organic compounds present in human odor using

SPME-GC/MS. J. Chem. Ecol. 31(7), 1607–1619 (2005)

10. Schoon, G.A.A.: The effect of the ageing of crime scene objects

on the results of scent identification line-ups using trained dogs.

Forensic Sci. Int. 147, 43–47 (2005)

11. Bernier, U.R., Booth, M.M., Yost, R.A.: Analysis of human skin

emanations by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. 1. Ther-

mal desorption of attractants for the yellow fever mosquito

(Aedes aegypti ) from handled glass beads, Anal. Chem. 71(1),

1–7 (1999)

12. Curran, A.M., Ramirez, C.R., Schoon, A.A., Furton, K.G.: The

frequency of occurrence and discriminatory power of com-

pounds found in human scent across a population determined

by SPME-GC/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 846, 86–97 (2007)

13. Eggert, F., Luszyk, D., Haberkorn, K., Wobst, B., Vostrowsky, O.,

Eckhard Westphal, E., Bestmann, H.J., Mu

¨

ller-Ruchholtz, W.,

Ferstl, R.: The major histocompatibility complex and the che-

mosensory signalling of individuality in humans. Genetica 104,

265–273 (1999)

14. Willse, A., Belcher, A.M., Preti, G., Wahl, J.H., Thresher, M.,

Yang, P., Yamazaki, K., Beauchamp, G.K.: Identification of

major histocompatibility complex-regulated body odorants by

Odor Biometrics

O

1013

O

statistical analysis of a comparative gas chromatography/mass

spectrometry experiment. Anal. Chem. 77, 2348–2361 (2005)

15. Wo

´

jcikiewicz, J.: Dog scent lineup as scientific Evidence. Pro-

blems of Forensic Sciences 41, 141–149 (2000)

16. LJN: AW0980, 11th April 2006, Helderse Taximoord

17. California v. Ryan Willis, MA020235, June (2002)

18. California v. Salcido, Cal. App. 2nd, GA052057 (2005)

Off-Angle or Nonorthogonal

Segmentation

▶ Segmentation of Off-Axis Iris Images

On-Card Matching

CHEN TAI PANG

1

,YAU WEI YUN

1

,XUDONG JIAN G

2

1

Institute for Infocomm Research, A*STAR, 21 Heng

Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore

2

Nanyang Technological University, 50 Nanyang

Avenue, Block S2-B1c-105, Singapore

Synonyms

Biometric Match-on-Card, MOC ; Work-Sharing

On-card Matching

Definition

On-card matching is the process of performing com-

parison and decision making on an integrated circuit

(IC) card or smartcard where the biometric reference

data is retained on-card to enhance securit y and

privacy. To perform enrolment, the biometric interface

device captures the biometric presentation of the user

to create the biometric

▶ template. Then, the biomet-

ric template and user’s information are uploaded to the

card’s secure storage. To perform on-card matching,

the biometric interface device captures the biometric

presentation and creates a biome tric template. The

created biometric t emplate is then uploaded to the

card for verification. The verification process shall

be executed on-card instead of sending the enrolled

template out of the card for verification.

Introduction

The need for enhanced security persists more than ever

in a more electronically dependent and interconnected

world. The traditional authen tication method, such as

PIN, is neither secure enough nor convenient for auto-

matic identification system such as border control.

Our economic and social activities in today’s electronic

age are getting more reliant to electronic transactions

that transcend geological and physical boundaries.

These activ ities are suppor ted by implicitly trusting

the claimed identity – with we trusting that the part y

we are transacting with is genuine and vice versa.

However, conventional password and Personal Identi-

fication Number (PIN) commonly used are insecure,

requiring the user to change the password or PIN

regularly. Biometric technology uses a person’s unique

and permanent physical or behavioral characteristics

to authenticate the identity of a person. Higher level of

security can be provided for identity authentication

than merely the commonly used PIN, password or

token. Some of the popular biometric technologies

include fingerprint, face, voice, and iris. All biometric

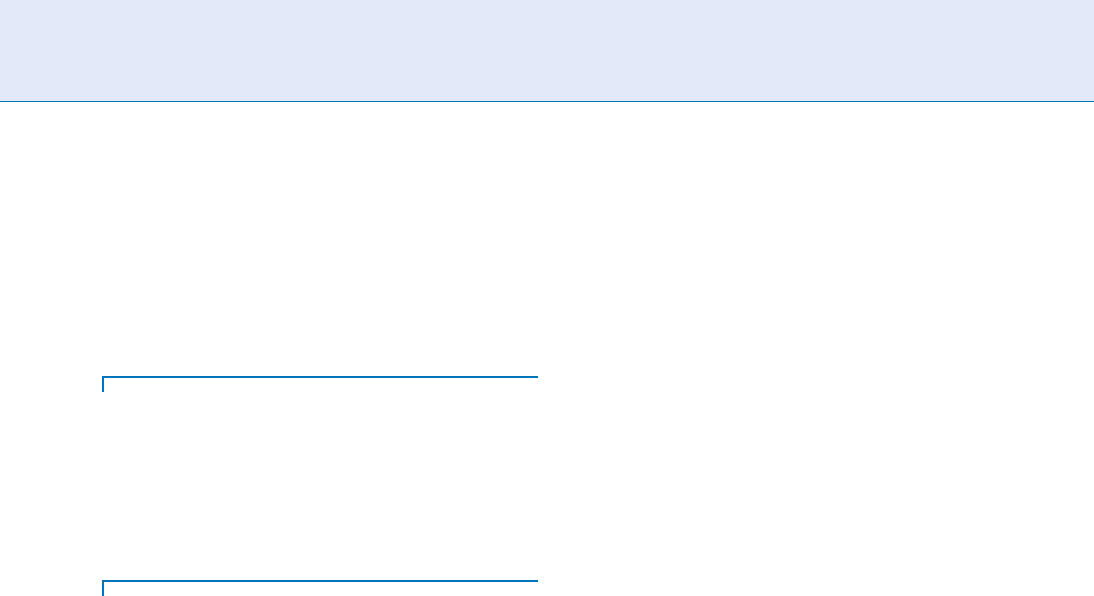

technologies share a common process flow as shown in

(Fig. 1) below.

Fig. 1 shows the basic architecture of biometric

authentication with a central database. In order to

use the biometric system to identify a person, he or

she will have to enroll in the system’s database. The

system has to create and maintain the biometric data-

base in a central PC or server. Even for a biometric

door access system (no matter for home use or office

use), a small biometric database is stored in the

embedded unit. Usually this is not a problem for

home use because only the owner or trusted person

can have access to the database. But what about the

other service providers? If hackers can access some of

the confidential database information of big corpora-

tions such as Bank of America, LexisNexis, T-Mobile

[1] and the security breach affecting more than 200,000

credit card holders [2] who then can the user trust?

Since biometric data is permanent and each person has

limited amount of choice (a person only has a face and

10 fing ers), having the biometric database information

stolen is a serious implication to the actual owner. One

of the alternatives is to store the biometric template

into a smartcard. Smartcard is a plastic card with

microprocessor inside to handle the data storage and

has processing capability with security features. Hence,

1014

O

Off-Angle or Nonorthogonal Segmentation

the combination of biometrics and smartcard offers

enhanced security for identity authentication.

Biometrics and Smartcard

Instead of relying on a centralized databas e system and

allowing individual service provider to create its own

biometric database, the biometric information can be

kept in the hand of the respective owner of the biomet-

ric data. This can be done by putting the biometric

data into a secure storage such as a smartcard. Smart-

card is a plastic card with an embedded microproces-

sor, memory and, security features. The user can

conveniently carry the smartcard, and thus it also

offers mobility to biometric data. The combination of

biometric and smartcard offers the advantages of mo-

bility, security and strong identity authentication

capability and, at the same time offers the user, a

high degree of control over who have access to that

biometric data. Hence, biometrics on the smartcard

can minimize the privacy concern. There are four

distinct approaches to combine the smartcard and

biometric technologies as follows:

1. Template-On-Card (TOC): This type of matching is

also known as off-card matching. The entire pro-

cess of biometric data acquisition, feature extrac-

tion, and matching is done at the terminal or reader

side. However, during the enrolment stage, the

original templa te which is constructed at the reader

is stored inside the smartcard. During matching ,

the reader will request for the original template

to be released from the smartcard which is then

matched with the query template. The decision of

further accessing information from the smartcard

is made on the reader side. The smartcard itself act

as a storage device. Cryptography should be used to

mutually authenticate the card and the biometric

interface device. To protect the communication

between the biometric interface device and the

card; a secure channel should be established prior

to the transfer of any template or data. As the

biometric template and other data objects such as

passport/visa or financial account information are

stored as a separate file in the smartcard, separate

secure channels can be used for transmitting differ-

ent data object. Fig. 2 shows the basic architecture

of TOC.

2. Match-On-Card (MOC): MOC means the biomet-

ric verification is performed in the card. The pro-

cess of biometric data acquisition and feature

extraction is done at the biometric terminal. Dur-

ing the initial enrolment stage, the original tem-

plate constructed at the reader is stored inside the

smartcard. During matching, the reader will con-

struct the query template which is then sent to the

smartcard for matching. The final matching deci-

sion is computed inside the smartcard and thus the

entire original template is never released from the

smartcard. Fig. 3 shows the authentication process

of a MOC system for a simple case of border con-

trol transaction. The dotte d line in the figure is the

applet firewall which restricts the access to the

matching applet to enquire the status of fingerprint

authentication. Therefore, the matching result will

be sent from the Matcher to the on-card applica-

tion by secured sharable method via smartcard

operating system. Neither the original template

nor the matching result is revealed to the outside

world. In order to protect the communication bet-

ween the biometric interface device and the card,

a secure and trusted channel is required.

3. Work-Sharing On-Card Matching:

▶ Work-sharing

on-card matching is similar to on-card matching

except for extra matching procedures are involved

On-Card Matching. Figure 1 Process flow involved in a common biometric system.

On-Card Matching

O

1015

O

to speed up the process. This type of matching is

designed for those cards which do not have suffi-

cient processing power and resources to execute

the biometric matching. In this case, certain parts

which are compu tation intensive such as template

alignment, are sent to the biometric terminal via

communication channel to perform computation.

The computed intermediate result is sent back to

the smar tcard to continue with the matching pro-

cess. The final calculation of the matching score

shall be calculate d inside the smartcard. Establish-

ing a secure channel is required to protect the

communication between the biometric terminal

and the smartcard. Fig. 4 shows the basic architec-

ture of work-sharing on-card matching.

4. System-On-Card (SOC):

▶ System-on-card match-

ing means the whole biometric verification process,

including the acquisition, is performed on the

smartcard. The smartcard incorporates the entire

biometric sensor, with processor and algorithm.

Therefore, the entire process of biometric data ac-

quisition, feature extraction, and matching is

done inside the smartcard itself. Both the original

template and the query template are computed

On-Card Matching. Figure 2 Template-on-card authentication.

On-Card Matching. Figure 3 Match-on-card authentication.

1016

O

On-Card Matching

in the smartcard and do not leave the card. Fig. 5

shows the general authentication process of a

SOC system.

Advantages of Match-on-Card

The level of security of a biometric system is judged by

examining where the feature extraction and matching

takes place. From the point of view of security, system-

on-card (SOC) offers the strongest security while

template-on-card (TOC) offers the weakest secure for

token based authentication [3]. It is obvious that the

SOC offers the highest security since the biometric

authentication process, including acquisition of bio-

metrics, is executed inside the smartcard itself and no

biometric data is transferred out of the smartcard. How-

ever, the cost of such smartcard will be high since the

card contains a biometric sensor and requires a powerful

processor (usually 32-bit) to meet the computational

demand of the biometric processing. Therefore, SOC is

still not practical for mass issuing and is usually suitable

for vertical market only. This means that the match-on-

card (MOC) technology which offers a higher security

than the TOC technology at reasonable price and is

a more practical solution. There are a lot of commercial

implementations for fingerprint, face, and iris. Finger-

print MOC is the most popular in market due to good

On-Card Matching. Figure 4 Work-sharing On-card matching.

On-Card Matching. Figure 5 System-on-card authentication.

On-Card Matching

O

1017

O

accuracy, ease of use, affordability, and an overall com-

pact solution.

The reasons why the match-on-card (MOC) tech-

nology provides better security in comparison to

template-on-card (TOC) technology are:

1. Better Security and Privacy Protection: TOC needs

to send the enrolment template from the card to

the biometric terminal for verification. The security

is compromised due to information exposure. Even

though the template is usually encrypted, the

on-card crypto engine is usually not very strong

due to constrained hardware specification of the

smartcard’s CPU. For the MOC case, the reader

will send the query template to the smartcard for

identity verification. Therefore, the MOC technol-

ogy does not reveal the entire original biometric

template stored in the smartcard. During the

matching process, the stored original template is

always trusted since the smartcard is considered a

secure storage device. Moreover, better privacy pro-

tection can be provided by match -on-card as no

one can download the user’s enrolment fingerprint

template from the card.

2. Two Factor Authentication: MOC technology will

establish a true two-factor authentication process

for the identity authentication needs. No matter

MOC or TOC, to start communication between

smartcard and reader securely, a secure channel

shall be established with mutual authentication

before any transaction takes place. This stage is to

allow the reader and the smartcard to verify the

cryptogram from each side to ensure both reader

and smartcard are valid and genuine. However,

this stage relies on exchanging challenge code be-

tween card and reader. Once the challenge code

is stolen by Trojan, hacker may be able to access

the smartcard and continue to do further hacking

procedures. For TOC, if the first stage is cracked,

the hacker will be able to access secured informa-

tion in the card. For MOC, if the first stage is

cracked, the hacker will still need to hack the sec-

ond stage of biometric MOC stage in order to

continue to access secured information. Hence,

MOC offers true two-factor authentication which

can provide stronger security to protect against

hacking.

3. On-Card Decision Making, Stronger Software Secu-

rity: In figure 3, the on-card matcher sends the

decision to other on-card application internally

via a software firewall that is controlled by the

smartcard Operating System (OS). Such internal

decision passing via firewall is a strong security

feature and very difficult to be hacked. Note that

the installation of on-card application is usually

done in the factory (ROM masking), in OS provider

of the smartcard or in authorized agency with

security code for installation. After installing all

necessary applications, it is possible to lock the

card forever to prevent installing other application

in the future. Each application has restriction

to access resources from other applications and

usually controlled by the smartcard OS. Among

the trusted applications, they can send and receive

information among them via the firewall with se-

curity code. Hence, it is very difficult for hacker to

upload Trojan to the card to hack the internal

invocation between applications, stealing internal

information from the card and sending fake deci-

sion from the MOC to fool other on-card applica-

tions to leak crucial information.

Implementations of Fingerprint

Match-On-Card

In recent years, there are quite a number of attempts to

design algorithm to perform fingerprint match-on-

card application. Mohamed [4] proposed a memory

efficient scheme of using line extraction of fingerprint

that could speed up the matching process. However,

this approach still needs a 32-bit DSP to process and

the computation is still relatively intensive for com-

mercial a smartcard. Vuk Krivec et al. [5] proposed a

hybrid fingerprint matcher, which combines minutiae

matcher and homogeneity structure matcher, to per-

form authentication with smartcard the system. Their

method is to perf orm minutiae match-on-card first.

Upon successful minutiae matching, the card delivers

rotational and translational paramet ers to the sys-

tem to perform second stage homogeneity structure

fingerprint matcher on the host side. However, this

hybrid approach cannot increase the accuracy signifi-

cantly compared to minutiae matcher alone but using

extra time to perform extra host side matching. Andy

Surya Rikin et al [6] proposed using minutia ridge

shape for fingerprint matching. The ridge shape infor-

mation is used during the minutiae matching to

1018

O

On-Card Matching

improve the matching accuracy. In their experiment,

only 64 bytes per template was used. They showed that

the accuracy was comparable with the conventional

matching but having a faster matc hing speed. The

matching time on a 16-bit smartcard was around 1.2

seconds with 18 minutiae. Mimura M. et al. [7] de-

scribed a method of designing fingerprint verification

on smartcard with encryption functions to enable ap-

plication using on-card biometrics to perform transac-

tion via Internet. Stefano Bistarelli et al. [8] proposed a

matching method using local relative information

between nearest minutiae. This method could achieve

matching time from 1 to 8 seconds with 10% ERR

on average using FVC2002 database. All the above

attempts were to implement fingerprint matching on

native smartcard or Java card in the research commu-

nity. Generally speaking, it is not easy to achieve good

accuracy with low computation requirement for on-

card fingerprint matching. Besides good matc hing

algorithms, software optimization is also an important

criterion to develop MOC system to achieve fast on-

card matching speed.

Of course, there are several commercial implemen-

tations for fingerprint MOC. Most of them are using

minutiae data for verification of identity. Those com-

panies usually provide the accuracy information of False

Acceptance Rate = 0.01% and False Rejection Rate =

0.1%. No further information regarding the database,

method of calculation, and other details have been

disclosed. Hence, it is not possible to tell the actual

accuracy of those commercial implementations using

their provided specification. Currently, the only reli-

able benchmarking is using common database such as

Fingerprint Verification Competition (FVC) fingerprint

database or National Institute for Standardization and

Technologies (NIST) fingerprint database to compare

the other system by using common performance indica-

tors such as False Match Rate (FMR), False Non-Match

Rate (FNMR), Equal Error Rate (ERR) and Receiver

Operation Curve (ROC) to compare the relative per-

formance among MOC implementations.

Performance of Fingerprint

Match-on-card

In 2007, NIST conducted an evaluation for the per-

formance of fingerprint match-on-card algorithms -

MINEX II Trial. The aim of MINEX II trial was to

evaluate the accuracy and speed of the match-on-card

verification algorithms on ISO/IEC 7816 smartcards.

The ISO/IEC 19794-2 compact card fingerprint minu-

tiae format was used in the test. The test was conducted

in 2 phases. Phase I was a preliminary small scale test

with release of repor t only to the provider. Phase II was

a large scale test for performance and interoperability.

Initially, 4 teams participated in the Phase I. In the

final Phase II test, three teams were participated in

the test. The Phase II report was published on 29th

February 2008 [9]. Some highlights of the result are

stated below:

The most accurate match-on-card implementation

executes 50% of genuine ISO/IEC 7816 VERIFY

commands in 0.54 seconds (median) and 99%

within 0.86 seconds.

The False Non-Match Rate (FNMR), at the indus-

trial preferred False Match Rate (FMR) = 0.01%, is

2 to 4 times higher than FMR at 1%.

Using OR-rule fusion at a fixed operating thresh-

old, the effect of using a second finger only after a

rejection of the first, is to reduce false rejection

while increasing false acceptance.

The most accuracy implementation satisfies only

the minimum requirements of the United States’

Government’s Personal Identity Verification (PIV)

program.

Some cards are capable of accepting more than

60 minutiae for matching. Some cards need minu-

tiae removal for either or both of the reference and

verification templates prior to transmission to the

card. It was discovered that the use of minutiae

quality values for removal is superior to using the

radial distance alone.

In this evaluation, only 1 team can achieve the mini-

mum requirement of PIV program. Hence, compared

to off-card matching, it is necessary to further improve

the accuracy for those applications that require

PIV specification such as immigration. As the compact

card format is the quantized version of the normal

size finger minutiae format, the performance is still

unknown of using the normal format in MOC. Num-

ber of existing commercial implementations are using

fingerprint minutiae proprietary format for MOC im-

plementation. MINEX II continues the Phase III in

2008 to gauge improvements over existing implemen-

tations and to ev aluate others.

On-Card Matching

O

1019

O