Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

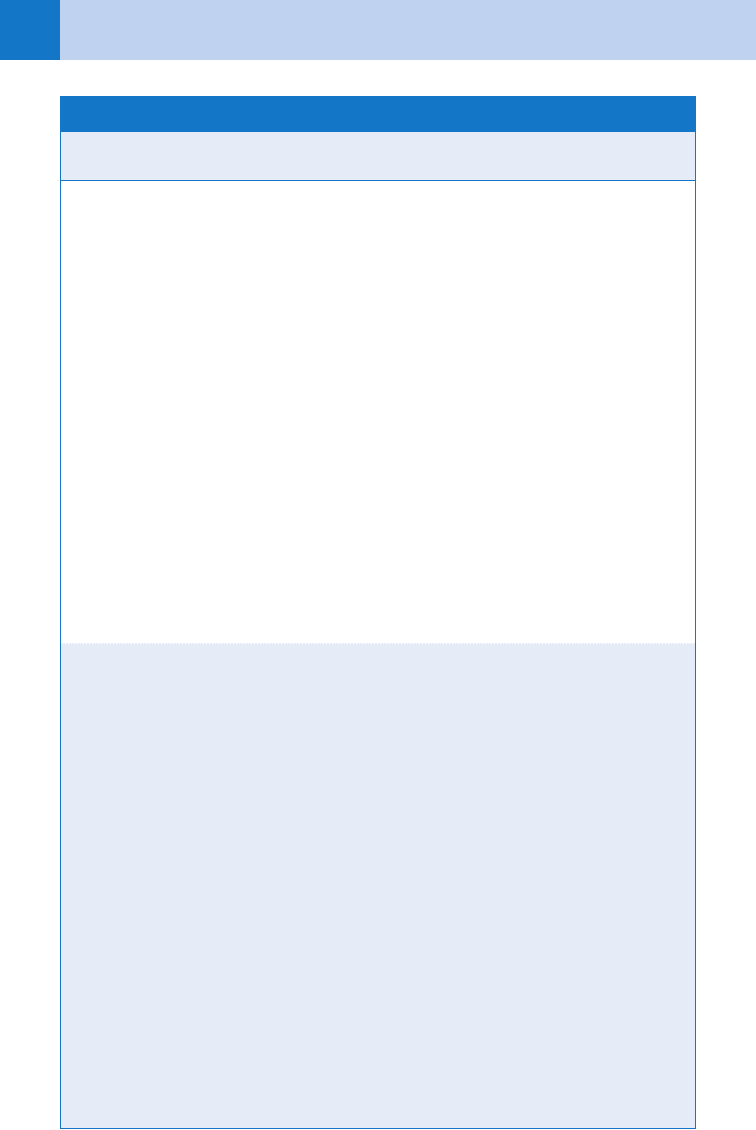

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES378

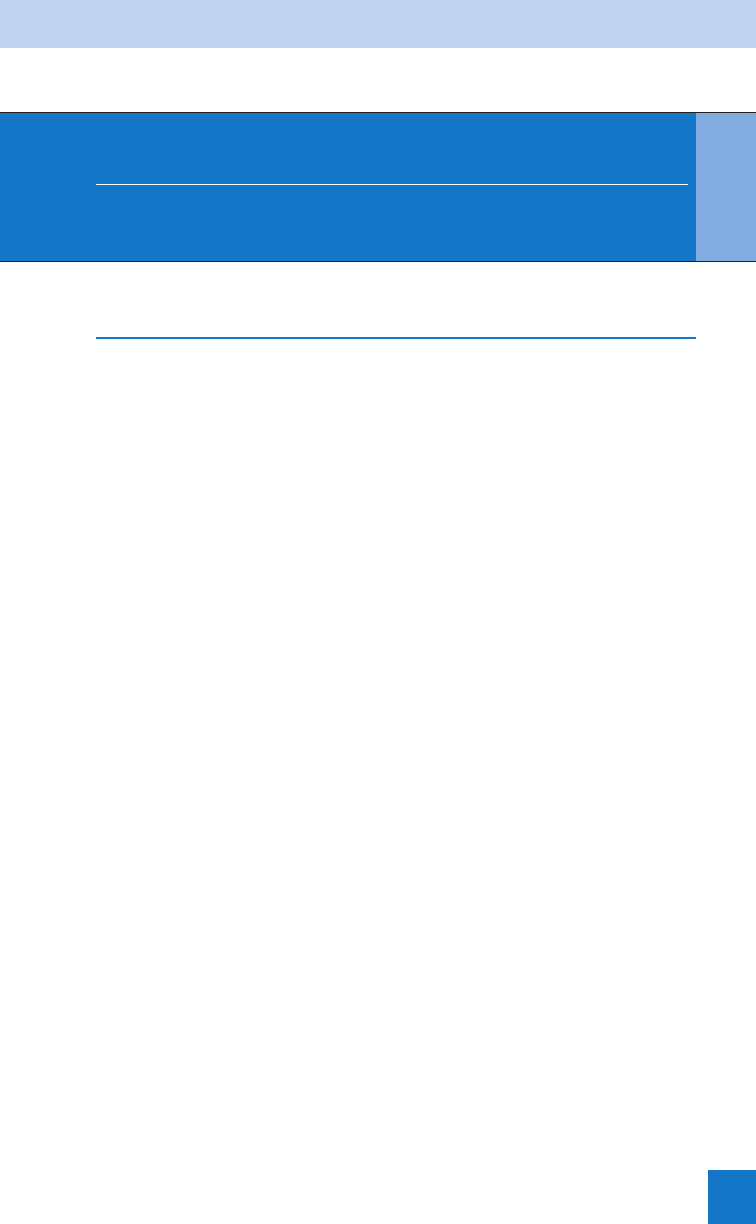

Causes

Clinical Signs/

Symptoms

Mortality

Rate Treatment

SJS Drugs

(70%–90%):

antibacterial

sulfon-

amides,

anticonvul-

sants,

NSAIDs,

allopurinol

Mycoplasma

pneumoniae

infection

Prodrome 1–14 days

before the onset of

mucosal involvement is

common (e.g., fever,

malaise, headache,

sore throat, rhinorrhea

and cough)

Acute eruption with red

to dusky, tender papules

at times targetoid with

potential for blistering/

sloughing (usually ,10%

of the BSA involved)

Extensive, hemorrhagic

necrosis of two or more

mucous membranes

(mouth and eye most

common)

5% Prompt withdrawal

of drug

Supportive care

(wound care in an ICU

or bum unit setting if

sloughing of skin

prominent, enteral nu-

trition, fluid/electrolyte

replacement, pain

management, moni-

toring for infection)

Steroid use is contro-

versial; some evidence

that steroid use re-

sults in worse progno-

sis; if part of treat-

ment should be

started very early in

the course

TEN Drugs

(95%):

antibacterial

sulfon-

amides,

anticonvul-

sants

NSAIDs,

allopurinol

Onset with fever and

tender skin several days

before blistering/slough-

ing begins

Painful, dusky red

macules appear, become

dusky, then confluent

with islands of sparing,

then blisters/sloughing of

the skin begins (usually

.30% BSA involved)

Mucous membrane

involvement in 90%

of cases

Poor prognostic factors

include increasing age,

delay in withdrawal of

offending agent, and

greater extent of epider-

mal attachment

30%–35% Prompt withdrawal of

drug*

Supportive care in an

intensive care burn

unit setting (see SJS

section)

The following are used

in treatment of TEN,

but efficacy is contro-

versial: intravenous

immunoglobulin,

systemic steroids

(see SJS section)

TABLE 54-2. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF THE MOST SERIOUS DRUG ERUPTIONS

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES 379

BSA, body surface area; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; ICU, intensive care

unit; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal

necrolysis.

*Garcia-Doval I, LeCleach L, Bocquet H, et al: Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome:

does early withdrawal of causative drugs decrease the risk of death? Arch Dermatol 136: 323–327, 2000.

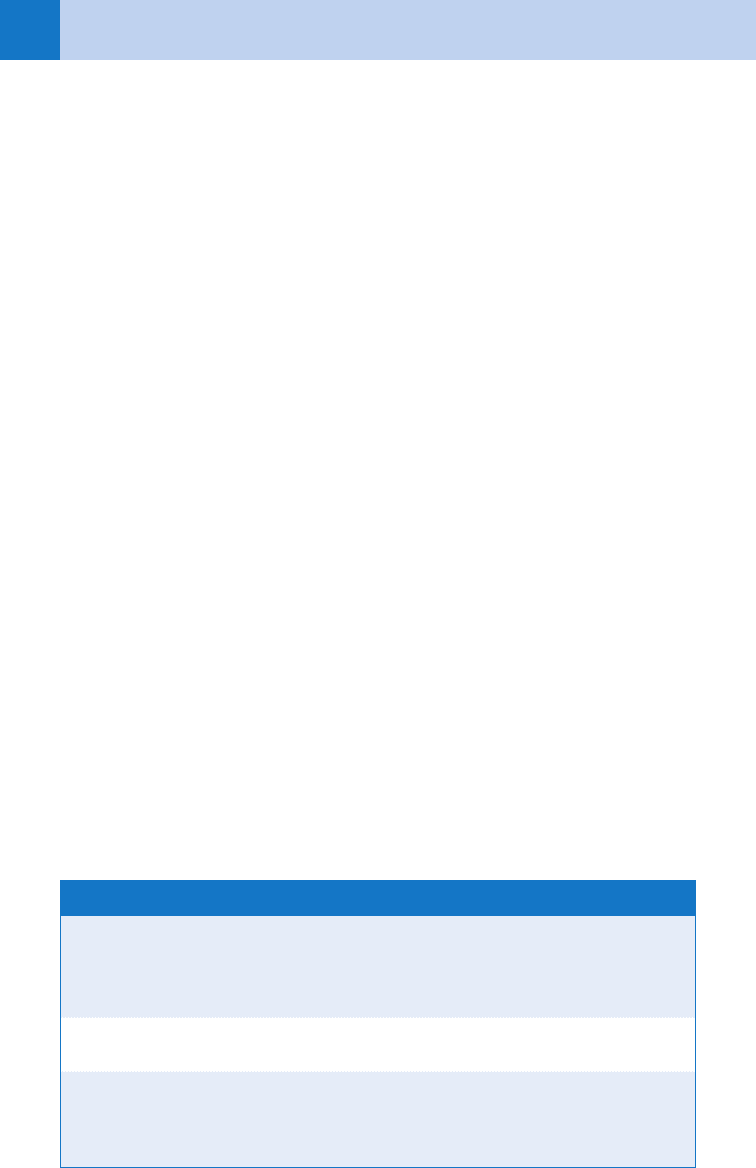

Causes

Clinical Signs/

Symptoms

Mortality

Rate Treatment

DRESS Drugs:

anticonvul-

sants, sul-

fonamides,

allopurinol,

minocycline,

dapsone,

gold salts

Fever and a morbilliform

skin eruption are the

most common presenting

features. The eruption

then becomes edematous

with follicular

accentuation.

Facial edema is a

hallmark of DRESS.

Lymphadenopathy,

eosinophilia, and atypical

lymphocytosis are

common features.

Visceral inflammation

(hepatitis most common)

10% Prompt withdrawal

of the drug

Systemic steroids

(severe cases with

visceral inflammation,

although efficacy

unproven in controlled

clinical trials)

Topical steroids

(milder cases for cuta-

neous manifestations)

TABLE 54-2. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF THE MOST SERIOUS DRUG ERUPTIONS—cont’d

14. How do I recognize a melanoma?

Melanoma requires urgent diagnosis and treatment. Recognition of the potential and referral

for surgical removal of melanoma before it has metastasized can be life-saving. Findings

suggestive of melanoma are irregular pigment; irregular borders; and presence of red, white,

or blue-black color. An underemphasized finding that can be extremely helpful is a difference

in appearance between the lesion in question and the patient’s other moles. A brown macule

on a fair-skinned person should be viewed with suspicion if the person does not have other

similarly pigmented lesions, even if the brown macule is regularly pigmented, small, and

perfectly round. A history of change in a mole is a risk factor, as is personal or family history

of melanoma.

KEY POINTS: USUAL TIME TO ONSET FOR CUTANEOUS

DRUG ERUPTIONS

1. DRESS syndrome begins 2 to 6 weeks after the responsible drug is started.

2. One to 3 weeks are required for the development of SJS and TEN.

3. Four to 14 days are required for exanthematous drug eruptions.

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES380

15. Describe common benign skin conditions that mimic melanoma.

n

Seborrheic keratoses are extremely common benign lesions that usually first appear in

middle age. They are benign growths of keratinocytes and can look alarmingly dark or

irregularly pigmented. The scaling produced by the seborrheic keratosis may be so

compact that it is difficult to discern, but detection of this rough scaling helps considerably

in distinguishing this lesion from melanoma.

n

Venous lakes are vascular growths that often appear on the helix of the ears and on the

lips of older persons with sun damage. The purple color may mimic that of a melanoma.

Pressing firmly on the lesion drains much of the blood from the lesion and reveals it as a

vascular growth.

16. Which spider bites can cause a necrotic reaction?

Only a few species of spiders in North America produce bites that may lead to skin necrosis.

Of these, bites of the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa) and the hobo spider (Tegenaria

agrestis) are important because they may be fatal. The range of the brown recluse is centered

in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri. Outside endemic areas, brown recluse bites are

uncommon, although they may occur because the spider may be transported on clothing or in

boxes. The range of the hobo spider is the northwest United States and western Canada. Other

Loxosceles species may cause necrotic reactions, and many of these spiders live in the

deserts of the southwest United States. If one is outside an endemic area, the diagnosis of

necrotic reaction to spider bite should be made with caution.

17. What skin lesions may be confused with a necrotic reaction to a spider bite?

Necrotizing fasciitis, ecthyma, pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, and clotting disorders.

Erythematous reactions to stings or bites, such as bee stings or tick bites, occasionally may

be confused with early reactions to spider bites. Most recently, methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin infection is often confused with spider bites.

18. What are the cutaneous findings of skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTI) with

MRSA?

SSTIs are the most common clinical manifestation of community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA).

This presents most frequently as a skin abscess or furunculosis. Often the patient will give a

history of an “infected spider bite.” There is no evidence to conclude that MRSA SSTIs are

clinically distinguishable from infection with susceptible strains of S. aureus, but several risk

factors are more common with MRSA such as a history of a spider bite, antibiotics in the past

month, history of previous MRSA, close living quarters, and activities with skin-to-skin

contact (athletes). Primary treatment is incision and drainage of abscesses. Adjunctive therapy

of purulent skin infections with antibiotics has not been proven to be necessary in several

studies in healthy, immunocompetent patients. Antibiotics are indicated if there is fever or

KEY POINTS: CUTANEOUS FEATURES CONCERNING

FOR MELANOMA

1. Different from patient’s other pigmented lesions

2. Recent changes in size, shape, and color

3. Markedly irregular borders

4. Markedly irregular pigmentation with colors of red, white, or blue

5. Areas of pigment regression

6. Any one of these may be an indicator of melanoma without the other features being present.

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES 381

surrounding cellulitis. For further recommendations for the treatment of CA-MRSA infections,

see: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/ar/CAMRSA_ExpMtgStrategies.pdf

19. Describe common benign skin conditions that mimic purpura resulting from

systemic disease.

n

Solar purpura is common on the forearms and backs of hands of people who have chronic

sun damage. Large areas of purpura may be evident and may have occurred with minimal,

sometimes unnoticeable trauma. Solar purpura is restricted to chronically sun-damaged

skin and is particularly common in patients on long-term systemic steroid therapy.

n

Schamberg’s purpura is a benign condition characterized by petechiae primarily on the

lower legs. The lesions tend to be pinpoint, nonpalpable, and extremely numerous. By

contrast, purpuric lesions of leukocytoclastic (hypersensitivity) vasculitis tend to be slightly

larger in diameter (often 2–4 mm), and frequently some of the lesions are palpable.

(Although leukocytoclastic vasculitis sometimes is referred to as palpable purpura, it is

common to find that most lesions are flat and only a few are palpable.)

20. Describe common skin conditions that mimic cellulitis.

n

A kerion caused by fungal infection in the scalp (tinea capitis) may be so intensely inflamed

that it is mistaken for cellulitis. Because a kerion may produce permanent, scarring

alopecia, it is important to recognize and institute therapy early. Kerions occur almost

exclusively in children.

n

Stasis dermatitis sometimes may be confused with cellulitis. Stasis dermatitis is usually

bilateral, whereas leg cellulitis is more often unilateral. Stasis dermatitis is characterized by

scaling and mild-to-moderate erythema. If the erythema is fiery red, the redness is rapidly

progressive, the patient is systemically ill, or there is a leukocytosis, cellulitis may be the

presumptive diagnosis.

n

Allergic contact dermatitis, such as poison ivy dermatitis, may result in lesions that are

intensely inflamed. The distribution of the lesions often suggests an exogenous cause. In

plant dermatitis, linear erythema, often with blisters, is an indicator of where the plant has

brushed against the skin. Antibiotic creams containing neomycin are another relatively

common cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Because antibiotic creams often are used on

wounds, allergic contact dermatitis caused by the cream may be mistaken for a resistant or

on-going wound infection.

21. In which disease associated with leg ulceration is débridement generally

contraindicated?

Pyoderma gangrenosum.

22. When should patients with dermatitis (eczema) be treated with systemic

steroids?

Systemic steroids generally should not be given to patients with chronic dermatitis. Topical

steroids should be used to avoid systemic side effects. Topical ointments and creams target

one of the primary problems in chronic atopic dermatitis, which is a skin barrier defect.

Patients taking systemic steroids also may exhibit a rebound of disease when the steroids are

tapered. Patients with acute dermatitis, such as severe poison ivy dermatitis, that is expected

to be self-limited may be given systemic steroids if the severity of disease merits and there

are no contraindications.

23. Should steroids be used for psoriasis?

Systemic steroids are generally considered to be contraindicated for the treatment of psoriasis

because severe rebound with generalized pustular psoriasis may occur following withdrawal of

the steroid.

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES382

24. What are the divisions of the classes of topical corticosteroids? On which

areas of the skin are they appropriately applied?

n

Low-potency topical corticosteroids (class 6 or 7 topical steroids, such as 1% and 2.5%

hydrocortisone, 0.05% desonide) are appropriate to use on the face, axillae, groin, breasts,

and genitalia, where the skin is thinner and more prone to cutaneous side effects.

n

Moderate-potency topical corticosteroids (class 4 or 5 topical steroids, such as 0.025%

fluocinolone, 0.1% triamcinolone, 0.2% hydrocortisone valerate) are useful on the neck and

body, avoiding the more sensitive areas mentioned previously. This class is given most

appropriately as first-line therapy for skin conditions diagnosed in the ED.

n

High-potency topical corticosteroids (class 2 or 3 topical steroids, such as 0.05%

fluocinonide, 0.1% halcinonide, 0.25% desoximetasone) should not be applied to the face,

breasts, genitalia, axillae, or groin. Topicals in this class are more likely to produce

cutaneous side effects if used diffusely or for long periods (.2 weeks). This class should

be prescribed only if moderate-potency topical corticosteroids have not been effective or if

the condition is limited to the particularly thick skin of the palms and soles.

n

Superpotent topical corticosteroids (class 1 topical steroids, such as 0.05% clobetasol,

0.05% betamethasone dipropionate in optimized vehicle, 0.05% halobetasol, 0.05%

diflorasone) are usually reserved for chronic, recalcitrant conditions, often of the palms and

soles. The risk of cutaneous side effects is greatest with this class, and this class of steroid

should be dispensed in a continuity-of-care rather than an ED setting.

25. Does the vehicle of the topical corticosteroid affect potency?

Yes. The same corticosteroid may be significantly more or less potent, depending on the

vehicle. In general, ointments are most potent, followed by gels, emollients, creams, lotions,

solutions, and sprays.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Dyer JA: Childhood Viral Exanthems. Pediatr Ann 36(1):21–29, 2007.

2. French LE, Prins C: Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In

Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors: Dermatology ed 2, London, 2008, Mosby, pp 287–300.

3. Frigas E, Park MA: Acute urticaria and angioedema: diagnostic and treatment considerations. Am J Clin

Dermatol 10(4):239–250, 2009.

4. Ghislain PD, Roujeau JC: Treatment of severe drug reactions: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal

necrolysis and hypersensitivity syndrome. Dermatol Online J 8(1):5, 2002.

5. May TJ, Safranek S: Clinical inquiries. When should you suspect community-acquired MRSA? How should you

treat it? J Fam Pract 58(5):276, 278, 2009.

6. Patel M: Community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, recognition, and

management. Drugs 69(6):693–716, 2009.

7. Revuz J, Valeyrie-Allanore L: Drug reactions. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors: Dermatology ed 2,

London, 2008, Mosby, pp 301–320.

8. Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al: Medication use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic

epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med 333:1600–1607, 1995.

9. Sams HH, Dunnick CA, Smith ML, et al: Necrotic arachnidism. J Am Acad Dermatol 44:561–573, 2001.

WEBSITE

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/ar/CAMRSA_ExpMtgStrategies.pdf

383

LIGHTNING AND ELECTRICAL INJURIES

CHAPTER 55

Gabrielle A. Jacquet, MD, and Timothy R. Hurtado, DO, FACEP

XII. ENVIRONMENTAL EMERGENCIES

LIGHTNING INJURIES

1. What causes lightning?

The etiology of lightning is a highly complex science involving physics and meteorology. First

of all, a large charge separation must occur within a cloud, turning it into a giant battery or

capacitor. This occurs from hailstones and raindrops settling at various rates in a convectively

active cloud. Charged particles get stripped off, and the cloud separates into a dipole or tripole

(two or three, respectively, equal and opposite electric charges or magnetic poles separated by

a small distance). Most often, the cloud base becomes negatively charged. In response, an

induced shadow of positive charge forms on the ground. The potential between the ground

and the cloud can be as great as 7,500 volts per inch. Lightning is initiated by the formation of

a stepped leader, a zigzag, short, stepped, downward series of branching ionized plasma

channels. At the same time, a positively charged pilot stroke arises from the ground, usually

from the tops of tall objects. When the two meet at about 50 to 100 m above the ground, the

return stroke is initiated. This is what we think of as the lightning bolt. It is a high-voltage,

high-current, high-velocity discharge that travels up the plasma channel. There is an average

of four to five return strokes. Lightning only sees objects that are in a radius of 30 to 50 m

from the tip. Thus, tall objects (such as a tall tree on a ridge) that are greater than 50 m from

the stepped leader may not offer protection from a strike.

2. How about thunder?

Thunder is an acoustic wave caused by the sudden heating of the air from lightning. It is the

result of explosive shock waves from instantaneous superheated ionized air. This can cause a

pressure rise up to 10 atm. The sound of thunder is rarely heard over 10 miles away and has

a lower pitch at greater distances. In addition, atmospheric turbulence may decrease the

distance the sound travels.

3. What are the mechanisms of lightning injury?

Lightning causes injuries in three basic ways:

a. Its electrical effects

b. The heat it produces

c. The concussive forces it creates.

Another way to consider lightning mechanisms is as follows:

n

Direct strike or contact injury: This occurs when the victim is in direct contact with the

lightning or an object or structure that is struck by lightning. It usually results in the

highest mortality and morbidity.

n

Splash or side flash: Lightning arcs from an object to a nearby person. Current seeks a

path of least resistance and can “jump” from its primary target to others.

n

Step or stride voltage: The lightning current strikes the ground, then spreads out. Current

moving underground can cause an induced current, up one leg and down another. This is a

reason for multiple victims of a single strike. Humans offer less resistance than the ground

thus lightning frequently spreads into their bodies after the nearby ground is struck.

Chapter 55 LIGHTNING AND ELECTRICAL INJURIES384

n

Rising upward streamer: This newly described mechanism happens with an injury from

the rising positively charged streamer, which does not connect with a pilot stroke to create

the plasma channel that allows return strokes, what we think of as a lightning bolt.

n

Blunt trauma and blast trauma: Blast trauma may occur from the thunderclap. Common

findings from this blast include pulmonary contusions, tympanic membrane rupture, and

conductive hearing loss. A victim may also be “thrown” by diffuse muscle contractions.

n

Secondary trauma and burns from fires: Trauma from falls or falling objects and thermal

burns from ignited clothing, heated metal, and burning surroundings can also complicate

lightning injuries.

4. True or false: During a thunderstorm, get into a car because the rubber tires

will insulate it?

False. You are safer inside a car than out during a thunderstorm but not because of the tires.

Think about it: The lightning bolt just passed several kilometers through the air to get to the

ground. It won’t be intimidated by 6 inches of rubber (or the rubber soles of your tennis

shoes, for that matter). The real reason that the car is safer is the metal skin of the body. It

acts as a Faraday cage (Table 55-1) allowing electromagnetic flow over the outer surface,

isolating the occupants. Now, of course, that may not protect the occupants from the flash,

thunderclap, splash current, or induced electromagnetic currents through the interior.

5. True or false: People are safe from lightning if they are indoors?

False. Maybe safer, but a significant number of lightning injuries occur to people who are

inside buildings. One mechanism for this is a side flash through plumbing, telephone wires,

and electrical appliances connected to the outside of the building by metal conductors.

6. True or false: Lightning never strikes twice in the same place?

False. The Empire State Building in New York is struck about 23 times a year; once, it was

struck eight times in 24 minutes.

7. Is a lightning bolt an alternating current (AC) or a direct current (DC)?

It is neither. It is a unidirectional current impulse (technically neither AC nor DC, although the

closest model would be a large DC discharge). It is very high voltage (100 million to 2 billion

volts), very large current (20,000–300,000 peak amps), and very high energy (1 billion joules

or 280 kilowatt hours). The bolt is also very hot: 8000°C to 25,000°C (the surface of the sun

is only 6000°C). The good news is that it’s a very short duration phenomenon (0.1–1 msec).

This ultrashort duration of exposure is the most important factor that separates lightning

injuries from other high voltage electrical injuries. The energy released in a lightning bolt is

more electrical energy than is produced by all of the electrical generators in the United States

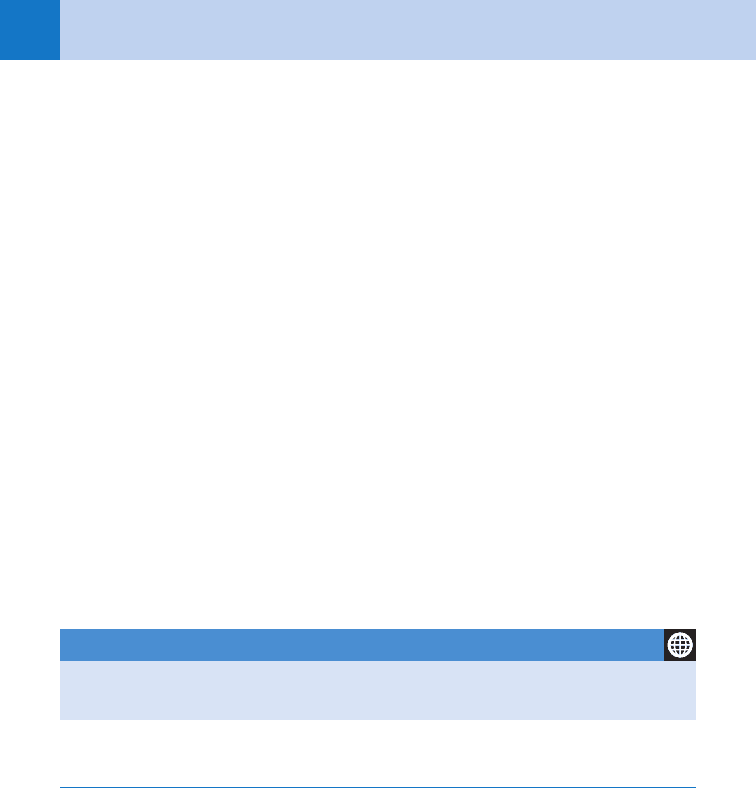

Fulgurite The word is from Latin, meaning lightning stone. When lightning strikes the

ground, it can spread out underground for up to 60 ft in radial horizontal arc-

ing. Depending on soil’s characteristics, there can be enough heat generated to

fuse silica into branching configurations. These stones are the fulgurites.

Faraday cage An enclosure formed by conducting material or by a mesh of such material;

blocks out external static electrical fields.

Flashover

phenomenon

Given the short duration of a lightning bolt, current is often conducted over the

skin without penetration. When this happens, it significantly lowers the mortal-

ity of a direct strike victim from 85% with signs of penetration to 40% without.

TABLE 55-1. LIGHTNING GLOSSARY

Chapter 55 LIGHTNING AND ELECTRICAL INJURIES 385

at that instant. However, because it is such short duration, it is only enough energy to light a

single light bulb for about a month. The energy is dissipated as light, heat, sound, and radio

waves.

8. Does lightning ever hit airplanes? What happens?

Yes, and usually not much. There are at least 160 lightning strikes on aircraft annually.

Typically, these strikes happen at 10,000 ft to 15,000 ft, in rain and light turbulence, within a

cloud and near the freezing level. Because the aircraft skin is metal, the lightning almost

always flashes over, leaving only minor damage. However, the blast effect of the thunderclap

can interrupt jet engines; the bright flash can temporarily blind pilots, and the induced

electromagnetic field can disrupt avionics and communication equipment—just what you

don’t want at 10,000 ft to 15,000 ft, in rain and light turbulence, within a cloud and near the

freezing level. There have been a few aircraft lost to fuel vapor explosions within the fuel tanks

induced by lightning.

9. How common is lightning?

There are up to 8 million lightning flashes worldwide each day. Across the globe, there are

2,000 active thunderstorms right now. Those storms produce 100 cloud-to-ground strikes per

second. In the United States, there are 50 to 300 lightning fatalities every year. This number is

hard to pin down exactly due to the majority of data being gathered from newspaper and news

accounts. “Storm Data” reports an average of 58 fatalities per year for the past 30 years, but it

suggests that there are probably closer to 70 deaths per year.

10. In what types of locations do lightning injuries occur?

In 40% the location goes unreported. Of those that are reported, 27% happen in open fields

and recreation areas; 14% happen under trees; 8% are water-related (e.g., boating, fishing, or

swimming); 5% happen on golf courses; 3% are related to the use of heavy equipment and

machinery; 2.4% are telephone related, and 0.7% are related to radio transmitter and

antennae. Central Florida is thunderstorm alley with the greatest number of thunderstorm days

in the United States.

States that are consistently in the top 10 for both total casualties and the highest casualty

rate are Florida, Colorado, and North Carolina. See Table 55-2.

11. Am I more likely to get struck as a woman or a man?

Remarkably, 84% of victims are male, likely reflecting a higher number of men engaging in

outdoor recreational and occupational activities.

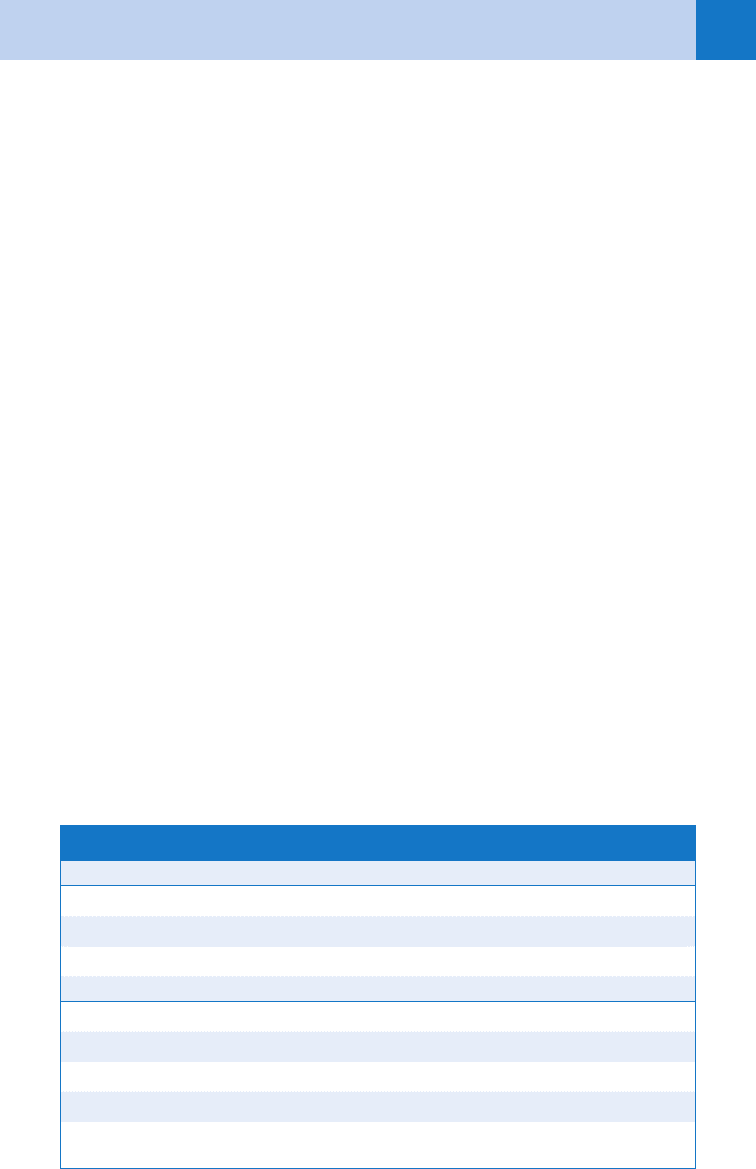

Top Three States for Lightning Incidence Bottom Three States for Lightning Incidence

Florida Alaska

Texas Hawaii

Colorado North Dakota

Top Five States for Lightning Injuries Top Five States for Lightning Deaths

Florida Florida

Michigan Michigan

Pennsylvania Texas

North Carolina New York

New York Tennessee

TABLE 55-2. Top States for Lightning Incidence and Injury

Chapter 55 LIGHTNING AND ELECTRICAL INJURIES386

12. What time of year am I more likely to get struck?

Summer seems to be the most dangerous time: the monthly incidence is June 21%; July 30%;

August 22%.

13. What factors predispose somebody or something to be hit by lightning?

n

Height of the object

n

Isolation

n

Pointiness of the object (this does not apply to humans)

14. I’m treating a farmer who was found unconscious in his field after a

thunderstorm. He has no recollection of what happened. How can I tell if

he was struck by lightning?

The easiest way to tell is to look at his skin and look in his ears. His memory of the

events won’t help; in fact, it is said that 100% of direct-strike victims have amnesia.

Victims of nondirect strikes may be able to recall being hit by lightning, but they often

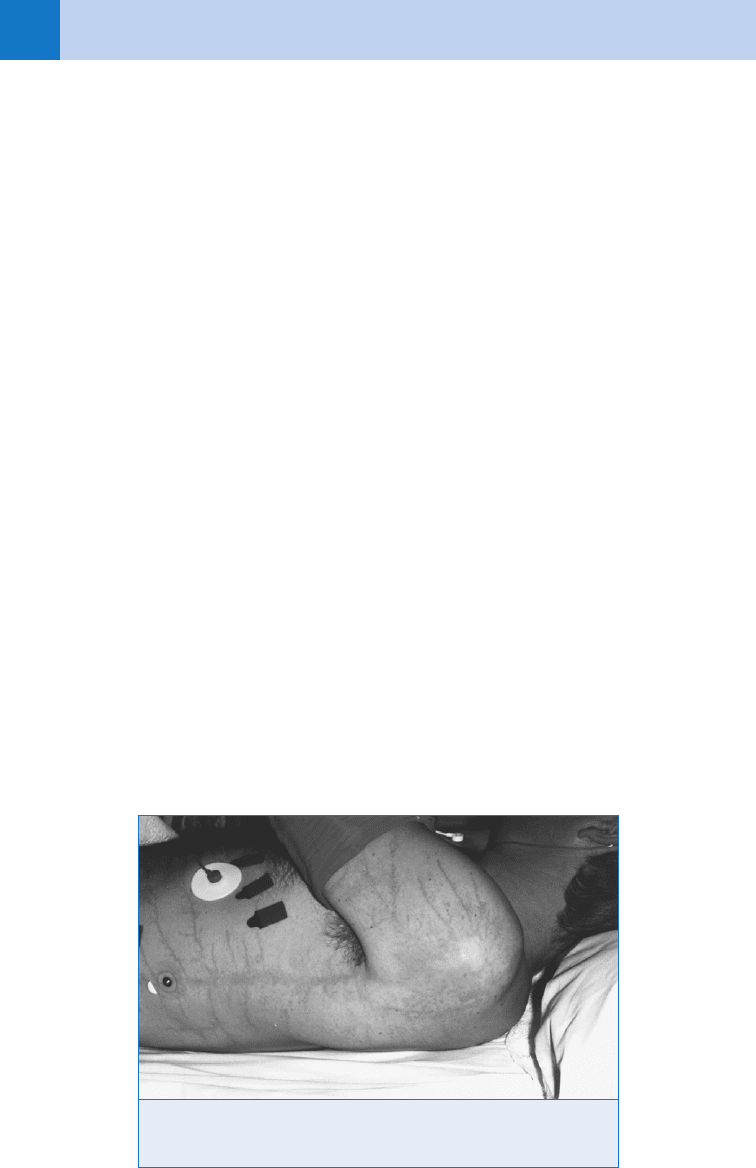

develop anterograde amnesia. However, arborescent superficial erythema (known as

Lichtenberg’s flowers, ferning, arboration, or fractals) is pathognomonic for lightning.

See Figure 55-1.

Unfortunately, it is seen in only seen in 20% of confirmed cases and fades away over

hours. It is not a true burn but the effect of a strong electromagnetic field on wet skin. It has

been postulated to be secondary to red blood cell extravasation into the superficial layers of

the skin from capillaries from the electrical injury. In addition, there may be partial-thickness

linear or punctate burns in moist areas. Tympanic membrane rupture (one or both) occurs in

50% of victims. Tinnitus is also common and usually resolves in hours to days. Seven

percent to 12% of victims experience temporary hearing loss, and a few have permanent

hearing loss.

15. The farmer is also tachycardic and hypertensive, with cool, pale skin, and

diminished peripheral pulses. Although awake, he seems unable to move his

extremities. Why?

He is likely suffering from lightning paraplegia (keraunoparalysis or Charcot’s paralysis). It

is probably primarily due to intense adrenergic stimulation, vasospasm, and hypoperfusion,

not direct nerve injury. If that is the case, it typically resolves over the next several hours.

However, you should be wary of occult injuries and diligent in your work-up for traumatic

injuries.

Figure 55-1. Ferning developed after the victim received a side flash lightning

strike. (From Auerbach PS: Wilderness medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2007,

Mosby. Courtesy Sheryl Olson, RN.)

Chapter 55 LIGHTNING AND ELECTRICAL INJURIES 387

16. My practice at multiple casualty incidents (MCIs) is to allocate resources to

victims who are not breathing and not moving only after I have taken care of

those with signs of life. Is that rule applicable in a lightning strike MCI?

No. Lightning strike is the one exception to the usual MCI triage rule. The first priority should

go to those who are not breathing and not moving. The reasons are that only those who

present in cardiac arrest are at high risk of dying. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(CPR) doubles survival from about 24% without CPR to 50% with CPR. Those who have not

arrested have little chance of dying, and so in this case the first priority goes to “the dead.” Of

note, victims’ cardiac automaticity often returns before spontaneous respirations; as such,

they may need prolonged rescue breathing during CPR.

17. I have heard that prolonged CPR is beneficial in lightning injuries. Is this

true?

No. There is no evidence that prolonged CPR improves recovery. It is reasonable to stop CPR

after 20 to 30 minutes as long as other reversible causes of cardiopulmonary arrest have been

addressed.

18. I am caring for a patient who has been struck by lightning and he has fixed

and dilated pupils. Can I stop CPR based on this finding?

No. One should not use dilated/fixed pupils as an indicator of brain death or to gauge the

prognosis in lightning victims until all other anatomical and functional etiologies have been

evaluated.

19. True or false: Lightning strike victims typically suffer extensive burns?

False. The crispy critter phenomenon is largely untrue. Victims do not burst into flame and

become reduced to a pile of ashes. Of the lightning strike victims who have burns, only 5%

have deep or significant burns. Lightning most often flashes over a victim with few, if any,

burns. Victims who experience burns typically demonstrate linear burns, punctuate burns,

feather burns (Lichtenberg’s Flowers), or thermal burns.

20. Which organ systems can be damaged by lightning?

See Table 55-3.

21. True or false: A lightning strike is always fatal?

False. Lightning is a surprisingly inefficient killer. The mortality may be as low as 10% to 30%.

However, lightning is the third most frequent cause of death caused by natural phenomena

(after floods and extremes of temperature).

22. True or false: If a victim of lightning is not killed outright, he or she will likely

be fine?

False. The majority of victims suffer some sequelae. These complications can include

neurologic, psychiatric, cardiac, pulmonary, otic, ophthalmologic, and musculoskeletal

disorders (see Question 20).

23. What are the best ways to reduce lightning risk?

n

Avoiding the following: thunderstorms, being the tallest target, holding a lightning rod,

touching conductors.

n

Seeking shelter indoors or in a car.

n

Staying away from groups (especially people who know CPR; they are your potential

rescuers).

n

Holding feet together and crouching down to reduce your stride potential.

24. What’s the 30-30 rule?

It is a lightning safety recommendation. If you see lightning and cannot count to 30 before

hearing thunder, you are in danger and should seek shelter. This is based on the flash-to-

bang method of determining your distance from a lightning strike: the time between the