Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

368

ARTHRITIS

CHAPTER 53

Catherine B. Custalow, MD, PhD

1. What are the signs and symptoms of arthritis?

Arthritis is the inflammation of a joint. The process may be monoarticular (involving a single

joint) or polyarticular (multiple joints). Patients typically report pain, swelling, redness, and

limitation of motion about the involved joint. On examination there may be tenderness,

swelling, effusion, erythema, and decreased range of motion. Preverbal children may present

with a limp or avoid using the extremity.

2. What are the common causes of acute arthritis?

Arthritis has many causes, including:

n

Infection (bacterial, fungal, or viral)

n

Trauma (fracture, overuse)

n

Hemorrhage (traumatic hemarthrosis, inherited coagulopathy, or anticoagulant induced)

n

Crystal deposition disease (gout or pseudogout)

n

Neoplasm (metastasis)

n

Inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever, lupus)

n

Degenerative conditions (osteoarthritis)

3. What is the difference between an intra-articular and a periarticular process?

In a true intra-articular process the inflamed synovium typically causes diffuse, generalized joint

pain, effusion, tenderness, warmth, swelling, and an increase in pain with active/passive range

of motion and axial loading. A periarticular processes, such as bursitis, tendinitis, or cellulitis,

tends to have a more localized area of tenderness, and no joint effusion. With a periarticular

process, moving a joint throughout the entire range of its motion may not reproduce the pain in

all directions. Instead the pain may be exacerbated only by stretching the specific muscles or

tendons over the areas that are affected.

4. What are some examples of diseases that are monoarticular, polyarticular, and

periarticular?

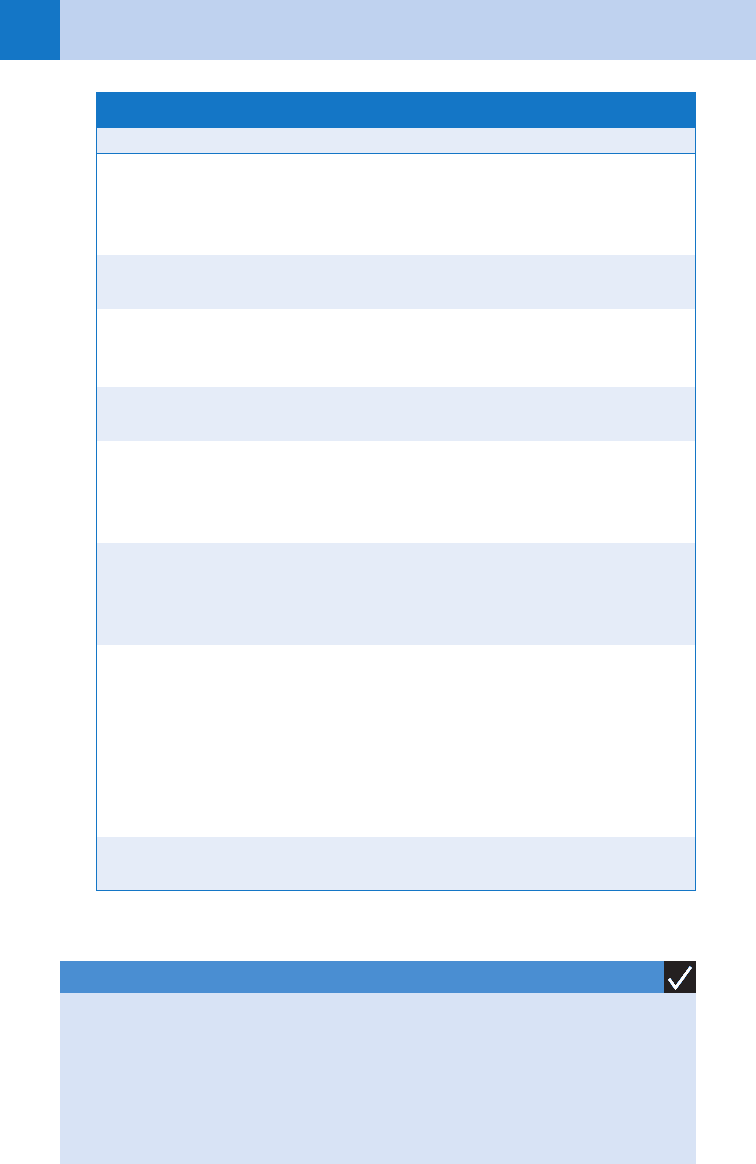

See Table 53-1 for a list of diseases by the number of joints involved.

5. What other physical findings may be helpful in diagnosing a patient with

arthritis?

A careful physical examination may provide additional clues to certain rheumatologic diseases.

Examples include genital ulcerations, purulent urethral discharge, and conjunctivitis in Reiter’s

syndrome; urethral or cervical discharge in gonococcal arthritis; tophi or concomitant renal

stones in gout; malar rash in lupus; swan-neck deformity in rheumatoid arthritis; erythema

chronicum migrans rash in Lyme disease; and high fever/chills in septic arthritis.

6. What does the location and distribution of the joint pain reveal about the

diagnosis?

Some diseases have a predilection for certain joints. Gout most frequently affects the first

metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the

metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. Osteoarthritis often

Chapter 53 ARTHRITIS 369

affects the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and the first metacarpophalangeal joints. In 45% of

cases septic arthritis attacks the knee.

7. Are X-rays helpful in the diagnosis of arthritis?

Often the only radiographic evidence of inflammation is soft-tissue swelling; however, plain

radiographs may reveal foreign bodies, fractures, effusions, osteoporosis, or osteomyelitis.

The radiographic changes of degenerative arthritis include asymmetrical joint space

narrowing, marginal osteophytes, ligamentous calcifications, and subchondral sclerosis. In

advanced gout, there may be punched out subchondral and marginal erosions, joint space

narrowing, and periarticular calcified tophi.

8. Are the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and peripheral white blood

count (WBC) useful for the evaluation of acute arthritis?

No. The ESR represents the body’s acute phase reaction to inflammation and infection.

Unfortunately, the ESR is neither sensitive nor specific enough to confirm or exclude any

particular disease. False-negative ESRs in septic arthritis can be as high as 20% to 30%.

Likewise, the peripheral WBC count does not contribute meaningfully to the diagnosis

of an inflamed joint as evidenced by one recent study in which 52% of patients with

septic arthritis had a peripheral WBC count less than 11,000 cells/mm

3

(normal).

Therefore, when clinical suspicion is high, a joint should be aspirated regardless of the

ESR or WBC count.

9. What is the most important diagnostic test for determining the etiology of

acute arthritis?

Arthrocentesis is the most important diagnostic procedure for evaluation of an acutely

inflamed joint. Synovial fluid analysis provides rapid, critical diagnostic information and

should be performed on all patients with an acute joint effusion who have no contrain-

dications. Other indications include drainage of a tense hemarthrosis and injection of

analgesic and inflammatory medications into the joint. The procedure is simple and safe,

and complications are rare when performed under sterile conditions and with proper

technique. If a prosthetic joint infection is suspected, an orthopedist should perform the

joint aspiration if possible.

10. How is arthrocentesis performed?

The detailed anatomic approach for each joint is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the

general steps are described here. Place the patient in a comfortable position with a cushion

supporting the joint if needed. Palpate the bony landmarks. Cleanse and prep the skin. Provide

anesthesia by local infiltration with an anesthetic solution such as 1% or 2% lidocaine. Using

a 19-gauge needle attached to a syringe, aspirate gently while carefully advancing the needle

Monoarticular Polyarticular Periarticular

Septic arthritis

Gout and pseudogout

Osteoarthritis

Hemarthrosis

Trauma

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatic fever

Osteoarthritis

Reiter’s syndrome

Lyme disease

Serum sickness

Cellulitis

Bursitis

Tendinitis

TABLE 53-1. JOINTS INVOLVED IN DISEASE

Chapter 53 ARTHRITIS370

into the joint. Avoid abrasion or puncture of the articular cartilage. Withdraw as much synovial

fluid as possible. If necessary, inject anesthetic solution into the joint for pain relief. Withdraw

the needle. Send the synovial fluid to the lab for analysis for WBC count, differential, crystals,

Gram stain, and culture.

11. What are some causes of arthritis with fever?

Diseases causing arthritis with fever include septic arthritis, Lyme disease, rheumatic fever,

Reiter’s syndrome, and toxic synovitis.

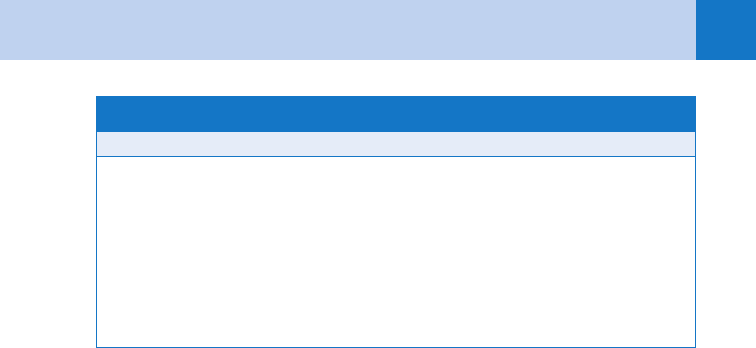

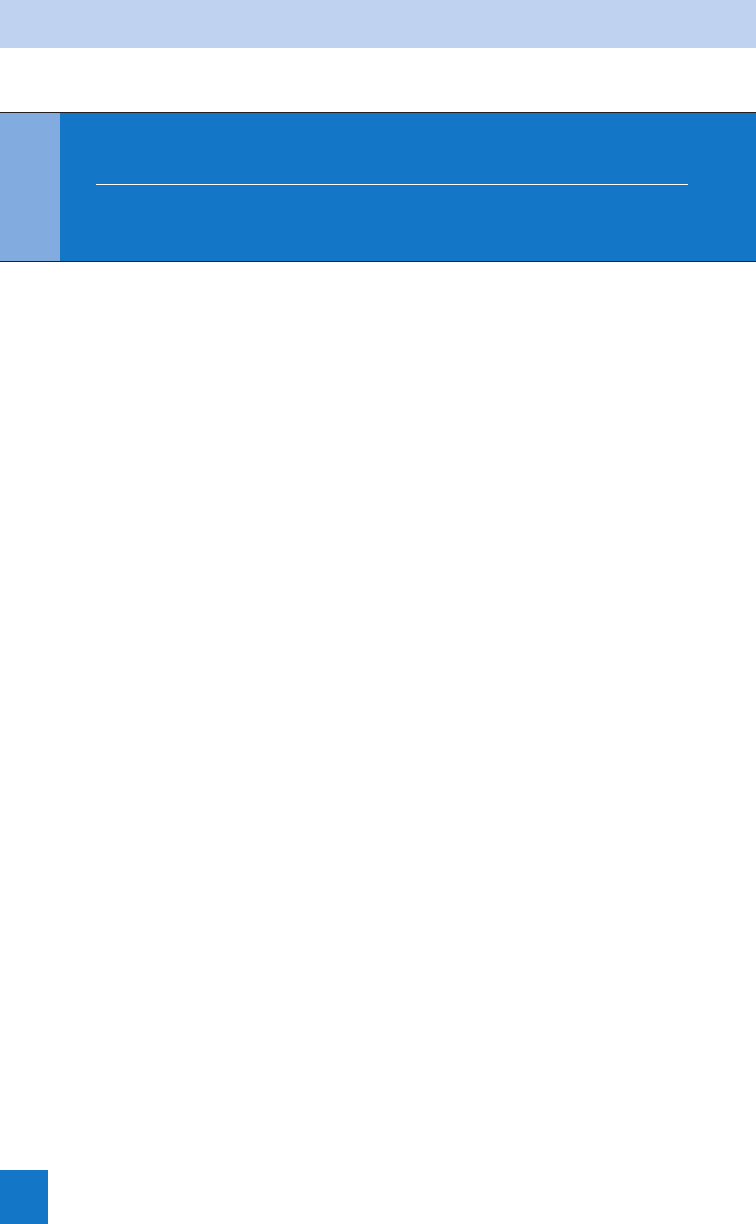

12. How do I interpret the results of the arthrocentesis?

See Table 53-2 for interpretation of synovial fluid analysis.

13. Does a synovial fluid white blood cell count of less than 50,000 cells/mm

3

completely rule out the diagnosis of a septic joint?

No. Typical synovial fluid counts in septic arthritis are greater than 50,000 WBC/mm

3

, with

predominantly polymorphonuclear neutrophilic (PMN) white blood cells, and a Gram stain

positive for bacteria. But a recent study showed that 36% of patients with septic arthritis had

synovial fluid counts less than 50,000 cells/mm

3

(168 cells in one patient). For this reason a

high index of suspicion should be maintained when a septic joint is in the differential and the

threshold for starting antibiotics must be low if the clinical examination suggests bacterial

arthritis.

14. What is the most serious cause of arthritis?

Bacterial arthritis is by far the most serious cause of acute monoarticular arthritis because

it can cause rapid cartilage destruction and significant in-hospital mortality. The most

important risk factor for septic arthritis is pre-existing joint disease, with almost half of

septic arthritis patients having previous joint problems. Permanent joint damage may

occur in as little as 7 days if untreated, and this can result in chronic disability and pain. In

children, septic arthritis can cause epiphyseal damage, resulting in growth impairment and

limb length discrepancy.

15. What organisms cause bacterial arthritis?

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of septic arthritis overall. Methicillin-

resistant S. aureus (MRSA) causes 25% to 50% of septic arthritis cases with risk factors

including advanced age, comorbid medical conditions, and significant exposure to the

health care system (80% of patients hospitalized in the preceding 6 months). Other

causative organisms include Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus),

Streptococcus pneumonia, Neisseria gonorrhea, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, Kingella kingae, and Haemophilus influenzae. In children the incidence of

septic arthritis due to H. influenza has decreased by 95% since widespread vaccination

against this organism.

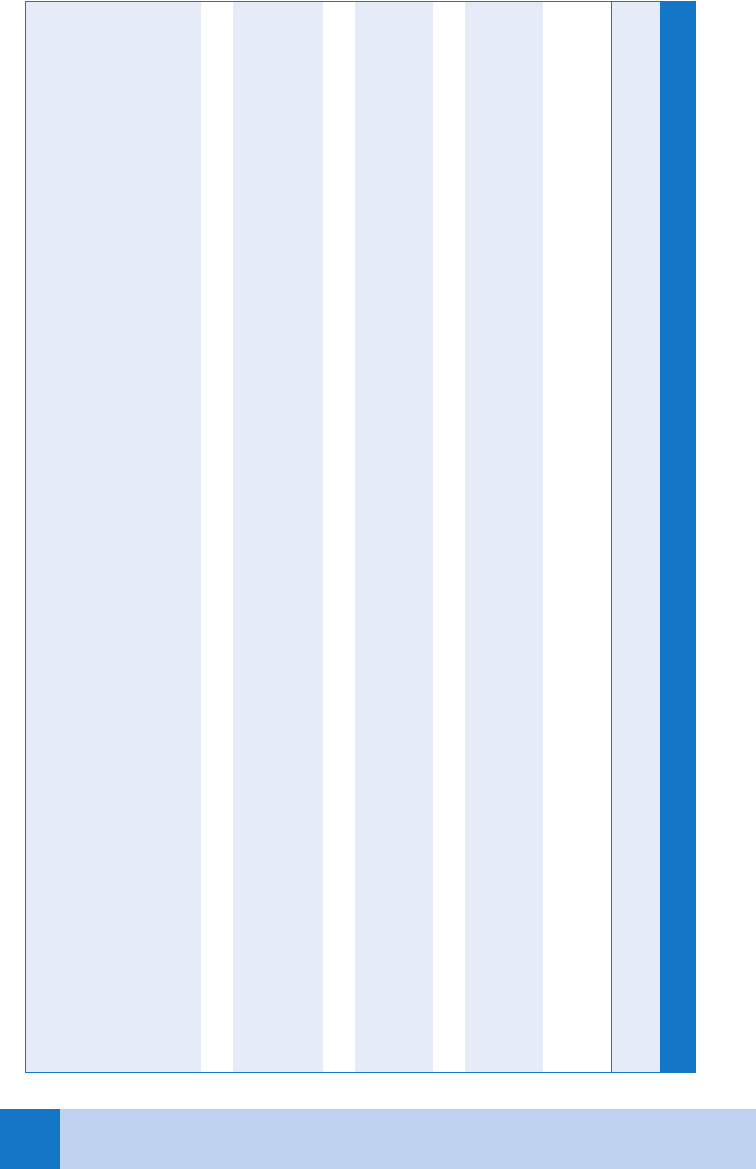

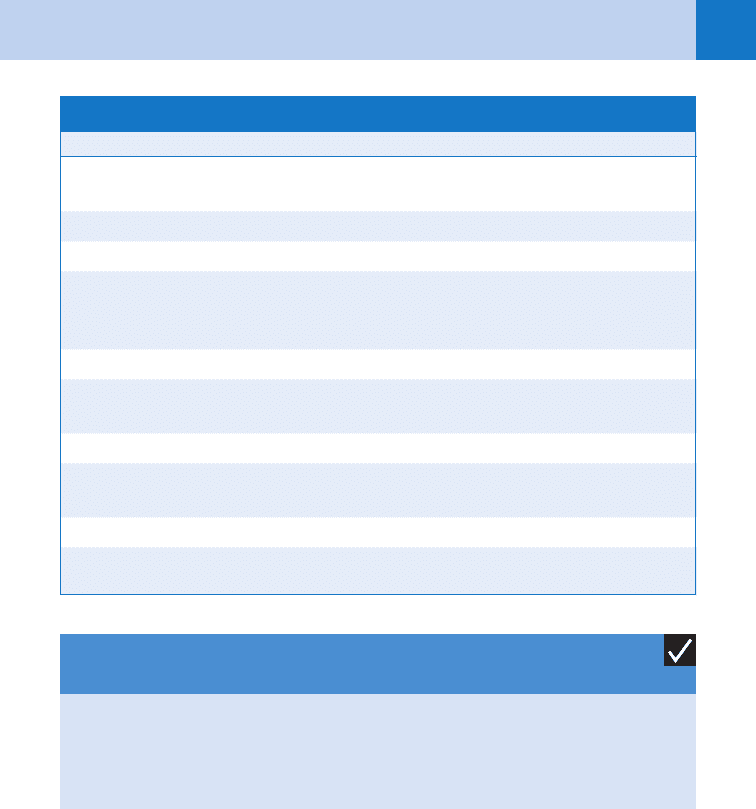

16. How is bacterial arthritis treated?

The patient should be admitted to the hospital and immediate orthopedic consultation

obtained for arthroscopic joint drainage, open joint drainage, or daily joint aspirations.

Intravenous (IV) antibiotics should be administered based on the Gram stain and culture of

the synovial aspirate if available and are generally continued for about 3 weeks. See Table 53-3

for a list of antibiotic recommendations for each organism. If the Gram stain is negative, then

empiric antibiotics can be administered according to the patient’s epidemiology. MRSA

coverage should be administered if the patient has risk factors such as being elderly, a recent

hospitalization, comorbid medical conditions, IV drug use, or living in a location with a high

prevalence of community-acquired MRSA.

17. What are some causes of arthritis with rash?

See Key Points.

Chapter 53 ARTHRITIS 371

Diagnosis Appearance

Total WBC

Count (per mm

3

) PMN (%)

Mucin Clot

Test

Fluid/Blood Glucose

(diff.) (mm/dL)

Miscellaneous

(Crystals/Organisms)

Normal Clear, pale 0–200 (200) ,10 Good NS —

Group I (noninflammatory; degenerative joint disease, traumatic arthritis)

Clear to

slightly

turbid

50–4,000 (600) ,30 Good NS —

Group II (noninfectious, mildly inflammatory; SLE scleroderma)

Clear to

slightly

turbid

0–9,000 (3,000) ,20 Good

(occasionally

fair)

NS Occasionally LE cell,

decreased complement

Group III (noninfectious, severely inflammatory)

Gout Turbid 100–160,000 (21,000) 70 Poor 10 Uric acid crystals

Pseudogout Turbid 50–75,000 70 (14,000) Fair-poor Insufficient data Calcium pyrophosphate

Rheumatoid arthritis Turbid 250–80,000 70 Poor 30 Decreased

Group IV (infectious, inflammatory)

Acute bacterial Very turbid 150–250,000 (80,000) 90 Poor 90 Positive culture for bacteria

Tuberculosis Turbid 2,500–100,000 (20,000) 60 Poor 70 Positive culture for

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

TABLE 53-2. SYNOVIAL FLUID ANALYSIS

LE, lupus erythematosus; NS, not significant; PMN, polymorphonuclear cells; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

(From Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH, editors: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 18, Philadelphia, 1988, W. B. Saunders, p 1994, with permission.)

Chapter 53 ARTHRITIS372

g, gram; h, hour; IV, intravenously; mU, million units; q, every.

Organism Gram Stain Antibiotics Dosage

Methicillin-sensitive

Staphylococcus

aureus

Gram-positive

cocci clusters

cefazolin or nafcillin

or oxacillin

cefazolin 2 g

IV q 8

nafcillin 2 g IV q 4

oxacillin 2 g IV q 4

Methicillin-resistant

S. aureus

Gram-positive

cocci clusters

vancomycin vancomycin

15 mg/kg IV q 12

Streptococcus

pneumonia

Gram-positive

cocci chains

penicillin G or

ampicillin

penicillin G 12–18

mU IV q day

divided

Penicillin sensitive Ampicillin

2 g IV q 4 h;

S. pneumonia

Penicillin resistant

Gram-positive

cocci chains

ceftriaxone or

cefepime

ceftriaxone

1 g IV q 24 h

cefepime

2 g IV q 8 h

Neisseria gonorrhea Gram-negative

cocci

ceftriaxone or

cefepime

ceftriaxone

1 g IV q 24 h

cefepime

2 g IV q 8 h

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

Gram-negative

rods

ceftazidime or ce-

fepime plus gentami-

cin or tobramycin

ceftazidime 2 g IV

q 8cefepime

2 g IV q 8 h

gentamicin 5 mg/

kg IV q 24

tobramycin 5 mg/

kg IV q 24

TABLE 53-3 ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT FOR SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

KEY POINTS: CAUSES OF ARTHRITIS WITH A RASH

1. Lyme disease: Erythema chronicum migrans

2. Reiter syndrome: Keratoderma blennorrhagicum

3. Disseminated gonococcal infection: Pustular rash

4. Psoriatic arthritis: Psoriatic lesions

5. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Malar rash

Chapter 53 ARTHRITIS 373

18. What is the difference between gout and pseudogout?

Gout develops when sodium urate crystals precipitate in a joint and pseudogout develops

when calcium pyrophosphate crystals precipitate in the joint. Both are released from the cells

lining the synovium and initiate an inflammatory reaction. Under polarized light microscopy,

gout crystals are needle shaped and negatively birefringent, whereas pseudogout crystals are

rhomboid in shape and positively birefringent.

19. What are the risk factors for gout and which joints are most commonly affected?

Risk factors for gout include obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dietary excess, alcohol

consumption, proximal loop diuretics, increased uric acid levels, and stress (illness or

surgery). Middle-aged men and postmenopausal women are at an increased risk for gout. The

MTP joint of the great toe is the most frequently affected joint (up to 75%). In this joint gout

is known as podagra. Other commonly involved joints are the tarsal joints, the ankle, and the

knee. Gout is polyarticular in as many as 40% of patients.

20. What medications can be used to treat gout emergently?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the primary agents used to treat gout.

Indomethacin is commonly used at a dose of 75 to 200 mg/day for several days and tapering

off as inflammation decreases. Colchicine inhibits microtubule formation, which results in a

decreased inflammatory response and is also effective in treating acute attacks. It may be

administered orally at a dosage of 0.5 to 0.6 mg every hour until symptoms improve, until

diarrhea or vomiting develops, or until the maximum dose of 6 mg has been reached. A single

IV dose of 1 to 2 mg of colchicine administered over 10 minutes may also be quite effective.

Once bacterial infection has been ruled out, oral corticosteroids may also be administered,

such as prednisone at a dose of 40 mg/day for 3 days and then tapering off. Drugs that alter

serum uric acid levels such as allopurinol and probenecid should not be administered acutely

because changing serum uric acid levels can exacerbate the condition.

21. Which tick-borne infection causes arthritis?

See Chapter 52.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Burton JH: Acute disorders of the joints and bursa. In Tintinalli JE, GD Kelen, JS Strapczynski, et al editors:

Tintinalli’s emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide, ed 5, New York, 2000, McGraw-Hill, pp 1891–1899.

2. Custalow CB: Arthrocentesis. In CB Custalow, editor: Color atlas of emergency department procedures,

Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier, 2005, pp 1–11.

3. Frazee BW, Fee C, Lambert L: How common is MRSA in adult septic arthritis? Ann Emerg Medi 54(5):

695–700, 2009.

4. Heffner AC: Monoarticular arthritis. In Wolfson AB, Hendey GW, Hendry PL, et al, editors: The clinical practice

of emergency medicine, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp 563–568.

5. Li SF, Henderson J, Dickman E, et al: Laboratory tests in adults with monoarticular arthritis: can they rule out

a septic joint? Acad Emerg Med 11:276, 2004.

6. Lowery DW: Arthritis. In Marx JA, RS Hockberger, RM Walls, et al, editors: Rosen’s emergency medicine:

concepts and clinical practice, ed 5, St. Louis, 2002, Mosby, pp 1925–1943.

7. Nuermberger E: Septic arthritis, community-acquired. In Bartlett JG, Auwaerter PG, Pham P, editors:

http://prod.hopkins-abxguide.org.

8. Ross JJ, Davidson L: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis: an emerging clinical

syndrome. Rheumatology 44:1197, 2005.

9. Schwartz DT, Reisdorff EJ: Fundamentals of skeletal radiology. In Schwartz DT, Reisdorff EJ, editors:

Emergency radiology, New York, 2000, McGraw-Hill, pp 22–24.

10. Thomas HA Jr, Hartoch RS: Polyarticular arthritis. In Wolfson AB, Hendey GW, Hendry PL, et al, editors: The

clinical practice of emergency medicine, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp 568–572.

374

SKIN DISEASES

CHAPTER 54

Lela A. Lee, MD, and Joanna M. Burch, MD

1. How are skin lesions best described?

It is helpful to remember dermatologic terms (Table 54-1). Describing in plain English how the

lesions appear is acceptable, however. Communication with other care providers may be

improved by the use of plain but accurately descriptive terms.

Characteristics helpful in establishing a diagnosis include the following: location and

distribution, color, size, presence or absence of scale, contour (e.g., raised, depressed, or

pitted), tactile characteristics (e.g., firm, spongy, fluctuant, blanchable, or nonblanchable), and

apparent depth (e.g., superficial, dermal, or subcutaneous).

2. What categories of skin conditions are life-threatening or associated with

life-threatening disease?

n

Diseases resulting in extensive compromise to the cutaneous barrier

n

Skin signs of systemic infection (e.g., meningococcemia)

n

Cancers (e.g., melanoma)

n

Urticaria or angioedema with airway compromise or anaphylaxis

n

Skin signs of vascular compromise (including hemorrhage, emboli, thrombi, and

vasculitis)

n

Skin findings of an introduced toxin (e.g., venomous snake bite)

n

Skin signs of physical abuse

3. List some cutaneous red flags (i.e., skin signs indicating an increased

likelihood of disease requiring emergency attention).

n

Extensive blisters or denuded areas of skin

n

Acute total-body erythema, particularly in the elderly or frail

n

Extensive erythematous eruption in a person who is febrile and systemically ill

n

Petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses

n

Necrosis

n

Urticaria

n

Isolated, abnormal-appearing mole

4. What types of skin diseases result in potentially life-threatening compromise

to the skin barrier?

Most of these are blistering diseases. When the blister breaks, the barrier is removed,

and the individual is at risk for infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and difficulties

with heat regulation. Skin conditions that can be associated with an extensively

compromised barrier include toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), Stevens-Johnson

syndrome (SJS), pemphigus and pemphigus-like chronic blistering diseases, and burns.

Patients with erythroderma (total or near-total body erythema) also may have problems

with infection, fluid and electrolyte balance, and heat regulation, particularly patients

who have significant chronic health problems, such as congestive heart failure. Lesions

of the oral cavity may compromise life if they are severe enough to prevent food or fluid

intake.

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES 375

5. Describe the skin findings in meningococcemia, Rocky Mountain spotted

fever, toxic shock syndrome, and necrotizing fasciitis.

n

In meningococcemia, lesions may be irregularly shaped petechiae or purpura with dusky

centers, located most commonly on the trunk and extremities. The lesions may involve the

palms and soles.

n

In Rocky Mountain spotted fever, skin lesions appear on about day 4 of the acute febrile

illness. Lesions begin on the distal extremities, may involve the palms and soles, and

spread centripetally. After a few days, the lesions become petechial or purpuric. In practice,

this eruption may be difficult to distinguish from that of meningococcemia.

n

Patients with toxic shock syndrome may have a scarlatiniform eruption, edema of the face

and extremities, conjunctival erythema, and erythema of the oral or genital mucosa. There

is desquamation of the hands and feet 1 to 2 weeks later.

n

Necrotizing fasciitis is characterized by a rapidly progressive painful erythema with

development of duskiness and frank necrosis. There may be blisters. The overlying skin

change is often mild compared with the necrosis occurring underneath.

KEY POINTS: PHYSICAL FINDINGS OF LIFE-THREATENING

DISEASES WITH COMPROMISE TO SKIN BARRIER

1. Extensive blistering

2. Erythroderma

3. Extensive oral erosions preventing food or fluid intake

Skin Lesion Description Example

Macule Flat, circumscribed color change (nonpalpable)

,1 cm

Café-au-lait spot

Patch Flat color change .1 cm Vitiligo

Papule Raised lesion ,1 cm Molluscum contagiosum

Plaque Elevated, flat-topped lesion .1 cm. Lesions with

epidermal changes (e.g., scale) would be

considered plaques.

Psoriasis

Nodule Raised lesion with a deeper palpable portion Erythema nodosum

Vesicle Raised, usually dome-shaped lesion filled with

fluid and ,1 cm

Varicella

Bulla Fluid-filled lesion .1 cm Bullous pemphigoid

Pustule Raised lesion filled with exudative fluid, giving it a

yellow appearance

Folliculitis

Cyst Nodule filled with semisolid-to-solid material Epidermoid cyst

Wheal Flat-topped, firm, raised, edematous lesion; a hive Urticaria

TABLE 54-1. BASIC DERMATOLOGIC TERMS

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES376

6. Describe the skin findings of common or distinctive childhood exanthems.

n

Scarlet fever occurs in children between the ages of 2 and 10 years. Red macules and

papules start on the neck and usually spread to the trunk and extremities. The skin may

have a rough sandpaper feel on palpation and sometimes can be petechial. Erythema is

usually most intense in the axillae, groin, and abdomen. Patients may exhibit Pastia’s lines,

which are petechiae in a linear pattern along the major skin folds. Palms and soles

characteristically are spared. The face appears flushed with circumoral pallor.

Desquamation usually occurs as the eruption resolves in 1-3 weeks.

n

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome begins as faint erythema on the face, neck, axilla,

and groin in a child younger than 5 years, usually following upper respiratory symptoms.

The skin is tender, and crusting typically occurs around the mouth, eyes, and skin folds.

The skin separates through the epidermis with even slight rubbing, leaving a red, moist

surface underneath (Nikolsky’s sign). Mucous membranes are not involved. In neonates,

the entire body is involved, whereas in infants and children the upper body is affected

preferentially.

n

Varicella (chickenpox) presents with abrupt onset of crops of faint macules that progress

through several stages. The macules become edematous papules, then vesicles over 24 to

48 hours. Often there is a small vesicle on a larger erythematous macule, described as a

“dew drop on a rose petal.” The vesicles develop moist crusts and leave shallow erosions.

Lesions tend to begin centrally and spread to the extremities. The palms, soles, and

mucous membranes frequently are involved. Characteristically, lesions in multiple stages of

development (i.e., macules, papules, vesicles, crusts, erosions) are present in the same

patient. The number of lesions ranges from 10 to 1,500 (average 300). The lesions are

usually pruritic. In general, lesions heal without scarring, although scarring may occur in

some instances.

n

Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) is a parvovirus B19 infection that results in intense

erythema on the bilateral cheeks (slapped cheeks). In some patients, after the facial

erythema, a diffuse pink-to-red macular eruption develops with a reticular or lacy

appearance. The macular eruption tends to reappear with stimulation of cutaneous

vasodilation, such as warm baths, exercise, or sun exposure. This can last for 4 months.

Some patients develop a petechial eruption of the distal hands and feet with parvovirus B19

infection. This is the purpuric gloves and socks syndrome.

n

Roseola (exanthem subitum) is a disease of infants and toddlers caused by infection with

human herpesvirus 6. After 2 to 3 days of sustained fever, abrupt defervescence is followed

by a pink maculopapular eruption. Periorbital edema is sometimes seen.

n

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease caused by Coxsackieviruses exhibits an abrupt onset of a

few scattered papules that progress to oval or linear vesicles with an erythematous rim. As

the name suggests, most lesions occur on the oral mucosa, palms, and soles. The oral

lesions appear as small, discrete, whitish-gray erosions.

n

Kawasaki disease is typified by an irritable child with conjunctival injection and slightly

swollen, distinctly red lips. The hands may be edematous or desquamating. The skin

findings are nonspecific and variable, ranging from macules to maculopapules to vesicles.

The child must meet the clinical criteria of fever for 5 or more days plus four of five of the

following:

a. Nonpurulent conjunctivitis

b. Mucosal changes

c. Edema or desquamation of the distal extremities

d. Exanthema

e. Cervical lymphadenopathy

7. What is erythema multiforme (EM)?

EM is usually an eruption of acute onset that is characterized by multiple, fixed red papules.

Because the keratinocyte is the target of inflammatory insult, there is keratinocyte necrosis

or apoptosis, manifest clinically as a central dusky center. The characteristic lesion is the

Chapter 54 SKIN DISEASES 377

target lesion: a papule with a central dusky zone and an outer zone of erythema. The

majority of EM lesions are erythematous, whereas typically only a few lesions are truly

target-like. Some lesions may develop vesicular changes in the center, due to intense

necrosis.

EM frequently follows herpes simplex (HSV) infection. Mucous membranes are usually

spared or affected mildly. Lesions are found on the dorsal hands and extensor extremities, and

palms and soles frequently are involved. Patients with HSV-associated EM are not generally

ill-appearing, and although the eruption can be quite impressive, it can be managed on an

outpatient basis. The eruption lasts 10 to 14 days and may recur after subsequent episodes of

HSV. Antiviral therapy is useful only as suppressive therapy to prevent HSV recurrences.

Treatment is usually reassurance or oral antihistamines to treat any associated burning and

itching. Topical or oral steroids are not indicated.

8. Which disease is most often mistaken for EM?

Acute urticaria. Urticarial lesions may be annular with concentric color changes and may

occur on the palms and soles. Usually, urticarial lesions have a pale edematous center with an

erythematous border, whereas EM lesions tend to have dusky centers. Lesions in urticaria are

transient (,24 hours), whereas the target-like lesions of EM are fixed and can be present for

one week or more. Urticarial lesions clear with subcutaneous epinephrine, whereas EM lesions

do not.

9. What is the most common clinical presentation of a cutaneous adverse drug

reaction?

Exanthematous (morbilliform, maculopapular, or urticarial) eruptions are the most

common presentation of a cutaneous adverse drug reaction. The eruption is characterized

by erythematous macules and papules that are usually widespread and symmetrically

distributed. Lesions can sometimes show central clearing, often leading to the incorrect

diagnosis of EM. The eruptions usually begin 7 to 14 days after the onset of the new

medication, but in the cases of rechallenge, time to onset can be shorter. Treatment

includes stopping the offending drug and prescribing antihistamines for symptomatic relief

of pruritus.

10. What drugs are most often implicated in exanthematous drug eruptions?

Aminopenicillins, sulfonamides, cephalosporins, and anticonvulsants.

11. What is the main diagnosis in the differential of exanthematous drug

eruptions?

Viral exanthems are often clinically and histologically indistinguishable from morbilliform

drug eruptions. History of recent drug administration or symptoms of viral illness will help

distinguish. Peripheral blood eosinophilia favors drug eruption. In children, 10% to 20% of

exanthematous eruptions are drug induced, whereas 50% to 70% are drug induced in adults.

Skin biopsy will not distinguish viral from drug exanthematous eruptions and is not helpful to

distinguish which drug is the cause.

12. What clinical signs should prompt consideration of a more serious adverse

drug reaction?

Facial edema; marked peripheral blood eosinophilia; hepatosplenomegaly; hemorrhagic and

tender mucous membrane lesions; painful, dusky papules or plaques; or blistering and

sloughing of the skin should prompt consideration of the serious drug reactions.

13. Describe the signs and symptoms of the most serious drug eruptions.

Three severe adverse drug reactions that can result in death are SJS, TEN, and drug reaction

with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) (See Table 54-2). Urticaria and angioedema

can also be life-threatening if the airway is compromised.