Marshall L. Stoller, Maxwell V. Meng-Urinary Stone Disease

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

474 Lam and Gupta

Specialty Stents

Open-ended ureteral catheters have no coils and thus are not suitable for long-term

urinary drainage. However, they can be secured externally to a urethral catheter to

provide temporary drainage. Open-ended stents are useful in helping to direct and

advance the guidewire into the ureteral orifice. They can assist in the collection of upper

urinary tract urine samples and permit retrograde pyelography. Furthermore, open-

ended ureteral stents are commonly placed intraoperatively to identify the ureters in

order to avoid inadvertent injury during abdominal or pelvic surgery.

Grooved stents have grooves spiraling down the exterior of the stent to improve

extraluminal flow and are aimed at postlithotripsy or holmium laser cases, where pas-

sage of stone fragments is needed. The Towers peripheral stent is a grooved stent manu-

factured by Cook Urological. The outer diameter ranges from 6 to 8 Fr, and the length

from 22 to 32 cm. The LithoStent by ACMI features 3 grooves spiraling down the

exterior of the stent-like gutters designed to prevent ureteral strictures and urinomas; the

lumen accommodates standard guidewires.

Tail stents are designed with a thinner, softer distal segment to increase patient com-

fort. They have a standard pigtail and a 6 or 7 Fr shaft at the proximal end, but the distal

end tapers into an elongated 3-Fr closed-tip tail, which rests in the bladder. Drainage is

achieved around the distal portion of tail stents, and consequently these stents are con-

traindicated when trauma to the distal ureter is suspected. Tail stents resist reflux because

the distal third of the tail is occluded, and approx 3–5 cm of the tail’s occluded portion

lies within the intramural tunnel and the distal ureter. Upper tract symptoms in patients

with tail stents could be attributed to either renal pelvic irritation or intermittent obstruc-

tion. Boston Scientific/Microvasive makes a tail stent called the Percuflex Tail Plus.

Injection stents are single-pigtail catheters that convert into an indwelling double-

pigtail ureteral stent, obviating a second cystoscopy. It is ideal for patients undergoing

SWL that need a double-pigtail stent postoperatively, but simultaneously require con-

trast instillation during the procedure for stone localization. Once the procedure is com-

pleted, the injection apparatus is removed leaving a double-pigtail stent.

Urinary diversion stents, made of various materials, have a single coil for the renal

pelvis and a long straight end that is brought out for external drainage. Drainage holes

are in the proximal end of the stent. They are commonly used to provide internal support

to ureteral anastomoses created during various types of urinary diversion. This allows

for accurate monitoring of urine output from each renal unit and facilitates removal of

the stent after an adequate period of healing.

Endoureterotomy/endopyelotomy stents are used for temporary drainage from the

ureteropelvic junction to the bladder following incision of a stricture. These internal

stents have a tapering diameter with no sideports designed to prevent narrowing of the

ureteral lumen while preventing ingrowth of the ureteral wall to the stent. The larger-

caliber portion of the stent acts as a mold for the healing of the incised ureter. Applied

Medical has a 7/10 Fr endopyelotomy stent for use with the Acucise endopyelotomy

balloon catheter device. Cook Urological makes a 6/10 Fr and 7/14 Fr stent and Boston

Scientific/Microvasive makes the RetroMax Plus in 7/14 Fr.

Subcutaneous urinary diversion (nephrovesical) stents are used as an alternative to

percutaneous nephrostomy for urinary diversion in uremic cancer patients and in those

with benign idiopathic ureteral obstruction, in which placement of ureteral stents have

failed. The proximal end of the stent is inserted into the renal pelvis via a percutaneous

nephrostomy puncture. A subcutaneous tunnel is created from the flank to the bladder,

Chapter 25 / Ureteral Stents 475

where the distal end of the stent is passed into the bladder via a suprapubic bladder

puncture.

Fistula stent sets specifically assist in the internal management of ureteral fistulas.

The stent has drainage ports solely in the pigtails, in order to reduce fluid pressure within

the ureter. It is manufactured in several different diameters and lengths.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS AND OUTCOMES

There are multiple indications for the placement of ureteral stents. They are often

placed as part of therapy to relieve ureteral obstruction or promote healing of the ureter,

or as prophylaxis against possible complications by assisting passage of a guidewire into

a ureteral orifice or by passively dilating the ureter before interval ureteroscopy.

Urolithiasis

This is probably the most common indication for ureteral stenting. Contemporary

management of renal calculi relies on endourologic techniques such as SWL, percuta-

neous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and ureterorenoscopy (URS) (54–57). Stenting can be

performed as a therapeutic or prophylactic procedure. Indications for therapeutic stenting

include: obstructive pyelonephritis secondary to an obstructing stone; renal failure sec-

ondary to bilateral obstructing stones or obstructing stone in a solitary kidney; refractory

renal colic or pain; and relief of high grade and/or long-term obstruction. PCNL can be

performed without need for postoperative ureteral stenting. Specific indications for

postoperative stenting following PCNL include extensive perforation of the collecting

system, need for subsequent SWL for large stone burden, ureteral obstruction secondary

to edema or stone fragments, and persistent urinary leakage following nephrostomy tube

removal.

The indications for ureteral stenting with SWL of renal calculi are less defined.

Prophylactic stenting before SWL has been shown to prevent the development of

‘steinstrasse’ in patients with stones >20 mm (58). However, opponents of stent use

report an increased morbidity associated with stent placement with no differences in

stone-free rates (59,60). Furthermore, patients with ureteral stents placed before SWL

were subjected to higher levels of total power during the procedure with no difference

in stone-free rates among patients treated without a stent (60). Urinary urgency (43 vs

25%), hematuria (40 vs 23%), duration of bladder discomfort (26 vs 13%), and duration

of urinary frequency (31 vs 16%) was also significantly higher in patients with indwell-

ing stents compared to those without (60).

SWL of ureteral stones can be performed either by pushback of stone into the renal

collecting system, bypass of stone with an externalized or internalized stent, or in situ.

Data analyzed by the American Urological Association Ureteral Stones Clinical Guide-

lines panel did not support routine use of ureteral stents to improve efficiency and stone-

free results of SWL, regardless of stone size (61). Ureteral stenting before SWL of middle

ureteral stones, however, may aid in the localization of stones overlying the bony pelvis,

especially in the presence of significant ureteral obstruction, which diminishes the effi-

cacy of intravenous contrast in aiding stone localization (62). Advances in fiberoptics has

allowed for the development of smaller ureteroscopes and advances in intracorporeal

lithotripsy, such as the holmium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser has allowed for

uncomplicated ureteroscopy to be performed without routine stenting with minimal

discomfort and a low incidence of postoperative complications (63,64). However, ure-

476 Lam and Gupta

teral stenting following ureteroscopy is recommended if complications occur, the stone

is impacted, the ureteral orifice is formally dilated to 18 Fr, fragmentation is incomplete,

or associated with a solitary kidney. In addition, stent placement after unsuccessful

ureteroscopic stone extraction may facilitate spontaneous stone passage and dilates the

ureter, making subsequent ureteroscopic procedures more successful (65).

Pregnancy

Urolithiasis during pregnancy is relatively infrequent with the reported overall inci-

dence of approx 0.07%, with 0.02% being symptomatic (66). Although hypercalciuria,

hyperuricosuria, and pregnancy-induced urinary stasis predispose to stone formation,

the incidence of symptomatic urinary stones in this population is no greater than that for

nonpregnant women of childbearing age (66,67). These findings are likely a result of an

increase in urinary lithogenic inhibitors (urinary magnesium, citrate, and glycoproteins)

and urine volume during pregnancy (67). Pain from renal colic is the most common

nonobstetric reason for admission during pregnancy (68). Approximately two-thirds of

symptomatic stones presenting during pregnancy will pass spontaneously; therefore, a

trial of conservative management with intravenous hydration, analgesics, antiemetics,

and prophylactic antibiotics should be advocated initially (69,70).

Azotemia, fever with obstruction, and urosepsis in the setting of urinary stone disease

requires urgent percutaneous nephostomy (PCN) or ureteral stent drainage, and the

gravid state should not alter this approach. Indwelling ureteral stent or PCN drainage is

recommended for interim treatment with definitive management delayed until postpar-

tum for symptomatic urinary stones that do not pass or if obstruction persists for more

than 3 or 4 wk (71,72). Both can be placed with ultrasound guidance to avoid radiation

exposure to the fetus. Encrustation is a concern during pregnancy because of gestational

hyperuricosuria and hypercalciuria (67). The authors recommend that ureteral stents be

changed in gravid patients at 4–6-wk intervals. PCN offers a good alternative to stent

drainage, especially early in pregnancy. The need for repeated stent changes is elimi-

nated, and it can be converted to an indwelling stent for comfort as the patient nears term.

Definitive stone management during pregnancy has been performed with few com-

plications. Both flexible and rigid ureteroscopy with holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy

have allowed for successful and safe endoscopic removal of symptomatic stones during

all stages of pregnancy, although this is not considered standard (73–75). Other forms

of intracorporeal lithotripsy that can be considered for treating stones during pregnancy

are the pulsed-dye laser and pneumatic lithotriptor because these modalities deliver

localized energy. In contrast, electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) and ultrasonic litho-

tripsy may present theoretical risks to the fetus because electrical energy discharged

from EHL could precipitate premature labor and the vibratory energy of ultrasonic

lithotripsy may pose a risk to the developing ears of the fetus (75). PCNL is rarely

indicated during pregnancy; however, it has been safely performed in cases of repeated

infection or obstruction despite percutaneous drainage (72). Other options have included

open stone surgery and early parturition. SWL is contraindicated in pregnancy because

of a theoretical risk to the fetus and/or ovaries (71).

Renal Transplantation

Urinary tract stones after renal transplantation can be a result of unsuspected donor

calculus or caused by persistent hyperparathyroidism, recurrent urinary tract infections,

Chapter 25 / Ureteral Stents 477

foreign body such as suture or staple, obstruction, habitual decreased fluid intake, and

type I renal tubular acidosis (76). Because the renal transplant is denervated, the kidney

transplant patient will not experience typical renal colic, and the diagnosis is suspected

when renal function suddenly deteriorates or transplant pyelonephritis occurs. Upper

tract stones are managed by the same techniques as stones in the normal urinary tract;

however, negotiation of the transplanted ureter may be difficult or impossible because

of tortuousity, thus favoring percutaneous techniques. SWL has been used successfully

with the stone positioned in the shock wave path (77).

Ureteral strictures and fistulas are the most frequent urologic complications in renal

transplantation, occurring in 1–12% of patients (78,79). Prospective studies have con-

cluded that ureteral stenting is beneficial in reducing vesicoureteric leakage rates and

obstruction in renal transplantation (80). Furthermore, presence of a ureteral stent does

not result in an increased incidence of urinary tract infection (81).

Obstructive Urosepsis

Management of an obstructed urinary tract can be performed with ureteral stent or

PCN drainage. The advantage of ureteral stenting is complete internalization of the stent

without the need for an external drainage device; however, the advantage of PCN is a

more definitive and reliable urinary drainage. Disadvantages of an indwelling stent

include pain, encrustation, infection, and bladder irritability. Disadvantages of PCN

include risk of renal and other organ injury during placement, their external nature, and

the potential for dislodgment, erosion, bleeding, or infection. Both ureteral stents and

PCN can be placed under intravenous sedation, although stenting usually occurs in the

operating room with an anesthesiologist present. Both ureteral stenting and PCN have

been demonstrated to effectively relieve obstruction and infection caused by ureteral

stones and neither modality is superior in promoting more rapid recovery following

drainage (82). The decision on which mode of drainage to use should be based on

surgeon preference and skill, presence of skilled interventional radiologists or urologists

trained to perform PCN, operating room availability, and stone characteristics.

Extrinsic Ureteral Obstruction

Ureteral stenting has been widely used in the management of ureteral obstruction

caused by pelvic malignancies or retroperitoneal fibrosis. Nevertheless, obstruction can

still persist even after placement of large-caliber indwelling stents (83). The combina-

tion of extrinsic compression against the stent and aperistaltic ureteral segments may

impair urine drainage around well-placed stents. Stenting with single indwelling stents

has been reported to fail in 50% of prostate cancer patients and 89% of patients with

cervical cancer (84,85). An option for patients failing previous stenting with a single

6-, 7-, or 8-Fr stent is to place two parallel ipsilateral ureteral stents, usually 8 Fr, which

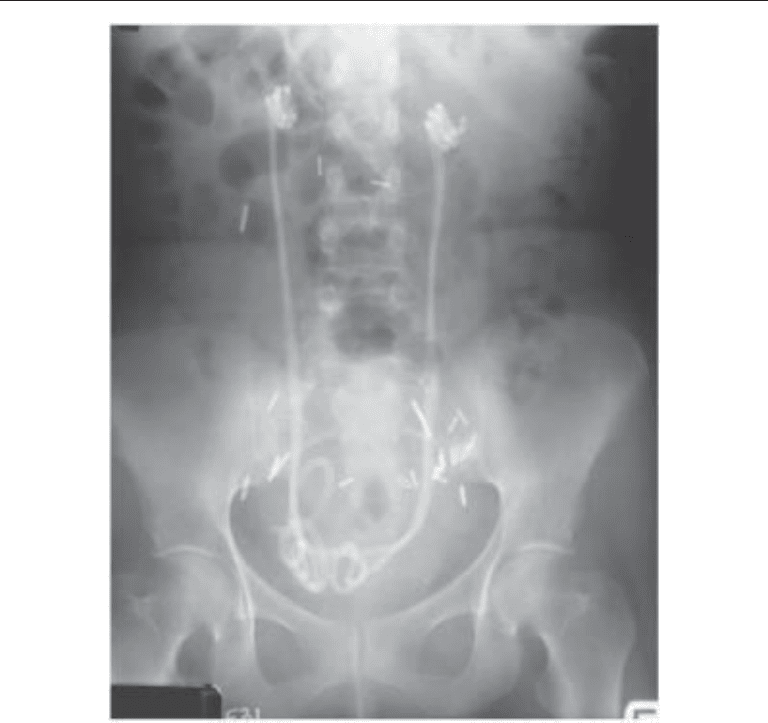

have been successfully used in the relief of obstruction (Fig. 1) (86). Another option is

the use of metal ureteral stents, which are intended for permanent implantation and have

a radial force higher than the pressure exerted by the surrounding tissues. Varying

success rates using these devices have been reported, ranging from 14 to 100% in

patients with strictures of various etiologies and locations (87,88). Multiple overlapping

metal stents can be placed either alone or in combination with conventional indwelling

ureteral stents in patients with long strictures. Not all patients with malignant strictures

are candidates for metal stent implantation, especially those patients with distal ureteral

478 Lam and Gupta

strictures because the stents may project into the bladder, prevent epithelization and

result in early encrustation blockage and patient discomfort. Subcutaneous urinary

diversion with nephrovesical ureteral stenting has also been reported to be successful

in patients with ureteral obstruction secondary to malignancy or medical conditions,

excluding them from more invasive procedures (89,90).

Endoscopic and Open Surgery

Ureteral stenting has become complementary to ureteroscopic procedures to prevent

either post-ureteroscopic ureteral edema or scarring of small mucosal lesions. Success

rates for ureteral stenting following endoscopic balloon dilatation of ureteral strictures

has been reported to be about 60% (91). Primary insertion of ureteral stents has been

shown to prevent or reduce the incidence of anastomotic stenosis and leakage following

open ureteral repair (92). Ureteral stents promote healing by providing a scaffold for

epithelialization and by avoiding early flow urine through the defect. However, other

studies have shown that ureteral healing is the same whether a stent is present or not (93).

Fig. 1. KUB radiograph of bilateral parallel double-pigtail stents for malignant ureteral obstruc-

tion.

Chapter 25 / Ureteral Stents 479

Endopyelotomy and endoureterotomy have become treatments of choice for uretero-

pelvic junction obstruction and ureteral stricture, respectively, owing to a short conva-

lescence period and absence of incision-related morbidity related to these procedures.

Stenting is an integral part of the ureteral endoincision that prevents leakage of urine into

the retroperitoneum and provides a mold for the ureteral epithelium to grow over. There

remains debate over the size of the stent and optimal duration of postoperative stenting.

A 6-wk duration of postoperative stenting is considered the gold standard based on

experimental work by Davis, who showed that after a full-thickness incision through the

narrowed segment of ureter, regeneration of the muscular layer was 90% complete by

6 wk (94). However, others have demonstrated shorter duration of postoperative stenting

in the successful outcome of endopyelotomy (95). The size of ureteral stent to use

following ureteral stricture incision remains just as controversial. A specialized

endopyelotomy stent, one that measures 14 Fr at the ureteropelvic junction and tapers

to 7 Fr, can be used (96). These can be placed antegrade or retrograde, and can drain

externally or internally. Placement of smaller 7 or 8 Fr internal ureteral stents have been

reported to produce comparable results with that achieved by the standard 14/7 Fr

endopyelotomy stent (97). Smaller caliber stents, ranging in size from 4 to 10 Fr, have

yielded satisfactory outcomes in 78–95% of patients (97).

Preoperative ureteral stenting has been used to prevent ureteral injuries caused by

gynecologic procedures, as well as general surgical procedures. However, some inves-

tigators have reported that preoperative catheterization is not effective in preventing

trauma and could even provoke it (98,99). Transilluminating ureteral stents have been

used for preventing ureteral injuries during gynecologic procedures (100).

Trauma

Ureteral injuries can be secondary to external trauma, either blunt or penetrating, or

more commonly are iatrogenic. In most cases, injury to the ureter diagnosed during the

initial evaluation of the trauma is generally treated by open surgical repair. External

ureteral trauma is almost exclusively associated with other injuries (101). Principles of

open surgical repair of ureteral injury include debridement and spatulation of the ureter,

followed by a tension-free closure with absorbable suture over an indwelling ureteral

stent. Delayed diagnosis of a missed or iatrogenic injury may be treated by percutaneous

drainage of urinoma and retrograde or antegrade placement of a ureteral stent if the ureter

is partially intact (102). Following tangential injury to a portion of the ureteral wall by

penetrating trauma or clamp or suture injury during surgery, passage of an indwelling

ureteral stent may allow for complete healing with reasonable long-term results (103).

Ureteral stents may also be used safely and effectively to treat persistent or recurrent

urinary extravasation resulting from major blunt renal trauma in appropriately selected

patients (104).

Fistulas

Ureteral fistulas can be classified based on location: ureterovaginal, ureterocutaneous,

ureteroenteric, lymphaticoureteral, and ureteroretroperitoneal (urinoma) (105). One of

the earliest uses of ureteral stents was for treatment of ureterovaginal fistula in which

polyethylene tubing was employed to affect closure (5). The use of percutaneous ureteral

stents to successfully treat urinary fistulas was first reported by Goldin (106). Andriole

and colleagues reported a 50% closure rate with use of an indwelling double-J stent in

480 Lam and Gupta

the management of upper urinary tract fistulas (84) and Chang and co-workers reported

successful resolution in 10 of 12 ureteral fistulas treated with percutaneous antegrade

ureteral stenting (107).

STENT REMOVAL

There are no controlled studies or consensus on the ideal length of time to leave

indwelling ureteral stents in place. In uncomplicated cases, stents can be removed in 2–

3 d after ureteroscopy. In cases of ureteral perforation or concern regarding ureteral

obstruction after instrumentation, an indwelling ureteral stent should remain in place for

at least 1–2 wk. The majority of indwelling ureteral stents can be removed in the office

with topical anesthesia using a flexible cystoscope and grasper. If the patient is unable

to tolerate an office procedure, stent removal can be performed under anesthesia in the

cystoscopy suite. In patients that are hospitalized, externalized ureteral stents can be

used, and before stent removal, a ureterogram can be performed to document ureteral

anatomy, passage or removal of stones, and lack of extravasation or obstruction.

Nonendourological techniques have been described for stent removal. Some stents

are manufactured with a nylon suture attached to the distal end, which can be left at the

urethral meatus allowing for removal after short-term drainage without the need for

repeat cystoscopy. However, patients must be cautioned not to place tension on the string

because this could potentially lead to unintentional dislodgment of the stent. The dan-

gling suture may also be associated with a slight degree of incontinence. A wire intro-

ducer with a snail head coil at its distal end has also been described with some success

for blindly grasping a stent within the bladder of women only (108). Stent retrieval has

been reported with indwelling stents incorporating a distal magnetic tip that can be

retrieved by using a magnet (109), and in stents with a stainless steel bead attached to its

distal end, which can be removed by a urethral catheter that has a rare earth magnet

attached to its proximal end (110). The development of biodegradable stents will elimi-

nate the need for invasive removal procedures (42–44). All patients with indwelling

ureteral stents should be told of the importance of appropriate follow-up and eventual

stent removal. Extracting forgotten ureteral stents can be technically challenging and

may require multiple cystoscopic and/or percutaneous procedures owing to potential

stent friability and breakage.

COMPLICATIONS

Despite recent innovations and improvements in stent materials and designs, prob-

lems relating to indwelling ureteral stent use still occur, such as migration, occlusion,

encrustation, breakage, and stone formation (111).

Symptoms and Quality of Life

Patient discomfort associated with irritative voiding symptoms, flank and abdominal

discomfort, and hematuria in the absence of urinary tract infection is the most common

complication involving patients with indwelling ureteral stents (112–114). It is pre-

sumed that the etiology for lower urinary tract symptoms is the distal portion of the stent

traversing the intramural ureter and impinging on the bladder floor (115,116). The cause

of upper tract symptoms, which may occur in as many as 50% of patients, is thought to

be secondary to vesicoureteral reflux. Many earlier studies comparing ureteral stents

failed to report any significant differences between stents of different compositions and

Chapter 25 / Ureteral Stents 481

diameter (113,114). However, more durable clinical studies have shown that “softer”

stents composed of biomaterials with smaller durometer, likely result in a lower inci-

dence of symptoms (114). In another randomized, blinded study, smaller diameter stents

were associated with less pain and improved patient tolerance (117).

Migration

Migration of ureteral stents is a well-known complication (118). Proximal or distal

migration may occur despite the J shape of the stent and can be problematic. Stents with

a full coil rarely migrate compared to those with the J configuration. Materials with good

memory, such as polyurethane, have the least tendency for migration, whereas stents

composed of softer materials, such as silicone, have the highest incidence of migration.

Stent migration may occur if the stent is too short, resulting in proximal migration, or

placed in massively dilated systems. One trick that can help prevent migration of the

proximal coil into the ureter in a patient with a widely patent UPJ is to place the coil into

a calyx with a relatively narrow infundibulum. Direct ureteroscopic removal and occa-

sional use of percutaneous techniques may be needed to extract proximally migrated

stents (119). These stents can be tricky to retrieve ureteroscopically because they can be

slippery and difficult to grasp, the distal coil displaces and distorts ureteral anatomy, and

the tip to the stent can dig into the ureteral wall. One trick the authors have found useful

in retrieving stents that have migrated into the distal ureter is the use of a stone basket

to “catch” the distal tip instead of using a grasper. Another trick is to use rat tooth or

3-prong graspers and to place one of the prongs into a side-hole of the stent to prevent

slippage when withdrawing.

Infection and Encrustation

Stent-related infection and encrustation are common complications, causing signifi-

cant morbidity, and are the major limiting factors in long-term use of biomaterials within

the urinary tract. The mechanism of encrustation in infected urine is identical to the

formation of infected urinary stones, involving alkalization of urine owing to hydrolysis

of urea by urease-producing organisms (120). Magnesium and calcium precipitate in the

alkaline environment produced by urea hydrolysis, forming magnesium ammonium

phosphate (NH

4

MgPO

4

2H

2

O) and calcium hydroxyapatite (Ca

10

[PO

4

]6H

2

O). It begins

with the development of an organic biofilm, often consisting of albumin, Tamm-Horsfall

protein, and alpha

1

-microglobulin, covering the plastic surface, and can enhance crystal

precipitation and aggregation events on the surface (121). This biofilm also allows

bacteria to be trapped and potentially be protected from antibiotics (122). Stent encrus-

tation in sterile urine is not completely understood, but it appears to be dependent on both

the urinary constituents and properties of the biomaterial. Sterile encrustations are often

composed of calcium oxalate (123). Metabolic disorders, such as hypercalciuria, certain

physiological states such as pregnancy, and even the intestinal microbial flora may

contribute to accelerated encrustation of stents within a sterile urinary environment

(123–125). Presently, there are no biomaterials used in the urinary tract that are able to

completely withstand the effects of the urinary environment.

Once established, stent-related encrustations and infections are often severe compli-

cations, necessitating stent removal if clinical cure is to be achieved. Stent colonization

is frequent with rates ranging from 28 to 90% (126). Use of urinary cultures to predict

stent colonization has been reported to have a sensitivity of 31% and incidence of stent

482 Lam and Gupta

colonization does not correlate with indwelling time (127). In addition, administration of

prophylactic antibiotic treatment does not prevent bacterial adherence to ureteral stents

(127). Sterile pyuria is not infrequent and reflects foreign body reaction to the stent. In

the absence of infection proven by culture, pyuria is generally inconsequential (30).

Encrustations may develop on ureteral stents intraluminally and extraluminally, reduc-

ing ureteral flow and causing obstruction of the renal unit, leading to impaired renal

function. Encrustations may be multifactorial and risk factors include poor compliance,

long indwelling times, sepsis, pyelonephritis, chronic renal failure, recurrent or residual

stones, lithogenic history, metabolic abnormalities, congenital renal anomalies, and

malignant ureteral obstruction (128). Interactions involved in the deposition of encrus-

tation on stents also appear to be influenced by the chemical composition of the polymer,

physical properties of its surface, presence of graft polymer coating conferring a hydro-

philic/hydrophobic nature on the biomaterial, contact time with urine, solute content of

urine, and intestinal microbial composition (123–125). The exact interval for changing

or removing an indwelling ureteral stent to avoid significant encrustation is difficult to

determine owing to multiple and unclear etiologies of stent encrustation. However, stent

encrustation rates increase with the duration that the stent remains indwelling. At less

than 6 wk, a 9.2% encrustation rate has been reported, which increases to 47.5% at 6–

12 wk and 76.3% at more than 12 wk (128). The optimal indwelling period based on

different series is 2–4 mo (111,128), however, it should be shorter in those patients with

risk factors that predispose them for developing encrustations. Some recent develop-

ments in stent design, including the incorporation of antibiotic coatings covalently bound

to the outer stent surface, are being used to decrease biofilm production and stent colo-

nization, but are not yet proven to be clinically effective.

Retained/Fractured Stents

Retained stents, especially those encrusted, occur infrequently but can be a difficult

and challenging problem that can lead to severe morbidity and sepsis if not managed

carefully. Successful management of a retained ureteral stent requires careful planning

and may require a combination of endourologic approaches that can be safely performed

to remove the retained stent and any associated stone burden during a single anesthestic

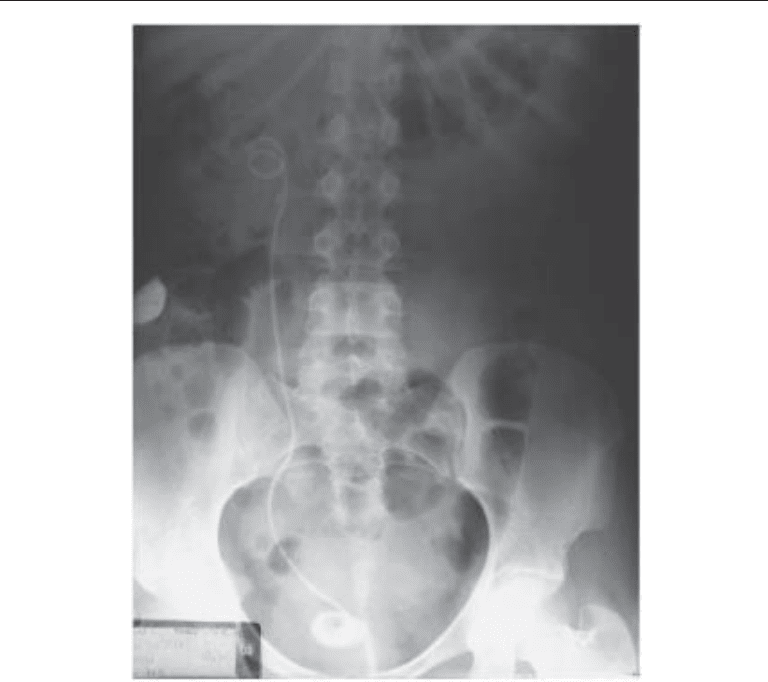

session (111). The authors feel the most important preliminary step is to obtain an

excellent kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB) radiograph with tomographic views paying care-

ful attention to the proximal coil and ureteral portions of the stent in order to determine

whether it appears slightly “thicker” than it should (Fig. 2). These are subtle signs often

missed by radiologists who are not familiar with the clinical situation. If no encrusta-

tions are present, cystoscopy is performed and gentle traction of the retained stent is

attempted. If the patient complains of pain or the stent does not move easily, the authors

do not proceed any further to avoid the risk of damaging the ureter. Occasionally, it is

possible to remove enough of the stent beyond the urethral meatus and attempt to pass

a guidewire through the stent to determine if the lumen of the stent is occluded and to

possibly uncoil the proximal portion of the stent.

If encrustations are visualized on KUB radiograph or fluoroscopy, the authors do not

advise attempted removal of the stent. Instead, ureteral access should be maintained with

a wire placed adjacent to the encrusted stent. In some cases, this may be sufficient for

facilitating removal of the retained stent. The authors recommend treatment of any

bladder component of encrustation first. If bladder component encrustations are minor,

a flexible or rigid alligator forceps or biopsy forceps can be used to separate the coils after

Chapter 25 / Ureteral Stents 483

breaking off pieces of encrustation. A cystoscopic view of a large bladder stone encom-

passing the distal coil of the retained stent is shown (Fig. 3A). Otherwise, EHL can be

used to break apart bladder encrustations and remove any stone-burden within the blad-

der (Fig. 3B). The least invasive and most efficacious way of managing encrustations on

the proximal or ureteral portions of the retained stent is SWL, and subsequently gently

tugging on the stent until it releases. If a lithotriptor is present in the room, this can be

performed immediately and simultaneously. Otherwise, a small (4.7 Fr) ureteral stent

can be placed adjacent to the existing stent. This will provide drainage if the renal unit

is obstructed and passively dilate the ureter. The patient is then brought back for SWL

at a later session. In no case should significant force be used to attempt stent extraction

because this may result in severe ureteral injury, or the stent may break off, especially

if it is brittle, making a terrible situation even worse. If a stent breaks off, ureteroscopy

can be performed to retrieve the broken stent fragments within the ureter.

If the above fails, or if a ureteral component of encrustation is visible, retrograde

ureteroscopy may be attempted after placing a safety wire. A small caliber (6 Fr) semi-

rigid ureteroscope can be passed under direct vision along side the existing stent and

encrustations can be fragmented using a holmium:YAG laser under low power (5 W).

Fig. 2. KUB radiograph showing a retained ureteral stent with a calcified bladder stone encom-

passing the distal coil of the retained ureteral stent and a “thickened” proximal coil.