Martel Gordon. A Companion to Europe 1900-1945

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter Seven

The Economy

Peter Wardley

The twentieth century was destined to be the American century and its first fifty years

saw a transfer of power and influence across the Atlantic. Although the nations of

Europe would experience growth after 1900 as indicated by a number of indices,

including population, output, standards of living, military capacity, cultural influence,

and even territorial scope, from then on the relative position of Europe would

diminish in the twentieth century as leadership of the world on all these counts

was achieved by the United States of America.

1

If one event has to stand to mark

this shift in power and influence from the “Old Empires” to the “New World,” it

is perhaps the defeat of Spain by an aggressive and expansionist United States of

America in 1898 which resulted in the Stars and Stripes flying victoriously over

Havana in Cuba and San Juan in Puerto Rico and Manila in the Philippines. The

European powers were rather slow to realize the significance of this transformation

and even more halting in their recognition of its causes. On at least the first of these

two counts, it could be said in their defense that those who determined American

foreign policy were also slow in accepting its implications. Many reasons can be

suggested for the Europeans’ failure to comprehend the shifting balance of world

power but, ironically, the successful economic performance of the European econo-

mies during the two decades before 1914 did little to prompt a reassessment which

would have challenged established views based on inadequate information, traditional

outlooks, outdated analysis, or even “Old World” prejudices. At Versailles in 1919,

when Europeans were compelled to engage in a radical reappraisal of their world at

the end of World War I, lingering nostalgia for a mythic Golden Age, longstanding

national rivalries and bitterness generated by the military conflagration, insufficient

foresightedness, strategy and even empathy guaranteed the emergence of severe

international difficulties within a generation. However, despite its retreat from the

European stage in the interwar years, the American achievement, simultaneously

beacon and gauntlet, provided Europeans a persistent, ever growing, manifestation

of their future. This future arrived in 1945 when, with American troops camped in

most of Europe’s capital cities, as either allies or occupiers, the ascendancy of the

United States was obvious and undeniable.

One factor, and probably the most significant, which explains both the consolida-

tion of European supremacy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the

emergence of the USA as the world’s dominant superpower in the twentieth century,

is economic performance. In this context, in providing an evaluation of one of the

most significant hinges of world history, a valid assessment of European economic

performance in the first half of the twentieth century has to be comparative, adopting

a perspective which is international as well as continental in its scope. The approach

adopted here introduces some of the concepts proposed by economic historians to

account for economic development, reviews evidence indicative of the nature and

extent of European economic growth before 1945, and uses business history to

appraise some of the sources of productivity enhancement which have been proposed

to explain relative corporate success and failure. The contemporaneous histories of

the US economy and American businesses are reviewed within this framework to

provide a comparative perspective.

European Economic Performance 1900–1945

We can begin as an assessment of economic performance within Europe between

1900 and 1945 with two obvious points which apply throughout the period: first,

there was considerable variation in the size of the European economies; and, second,

across the continent, there was considerable variability in the per capita incomes and

the levels of productivity achieved in different countries. However, even at this most

simple level, it is easy to demonstrate the instability of “Old Europe” which added

to economic uncertainty and fragmented markets, thereby curtailing economic

growth. The disintegration of the empires of central Europe added to variability of

size of economies, but although war was the most frequent catalyst here, not all these

changes were caused directly by World War I.

Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and the USSR were

carved from the war-torn and truncated remnants of the Russian, German, and

Austro-Hungarian empires. At almost the same time as the boundaries of these new

states were settled, the Irish Free State, after the Anglo-Irish conflict of 1919–20,

achieved dominion status within the British Empire, adding yet another independent

European economy.

Although Hitler’s expansion of Germany, through the Anschluss with Austria, the

seizure of the Sudetenland, and the establishment of a protectorate over Bohemia

and Moravia, is the most famous example of territorial ambition before World War

II, such ambitions were not restricted to the major powers. International borders

had been redrawn after the First Balkan War of 1912 when Bulgaria, Greece, Romania,

and Serbia defeated the Ottoman Empire and almost pushed it out of Europe, leaving

only Constantinople and its hinterland as its only remaining European territory. In

1913 a Second Balkan War was fought when the victors quarreled over the territorial

settlement, and the size of Greece – in terms of both population and territory – prac-

tically doubled within two years. Borders were more certain in North America,

though Germany’s attempt to entice Mexico into World War I as its ally with promises

of territorial adjustments in its favor are a reminder that even the boundaries of the

USA were regarded as adjustable by some Europeans. Although changes in interna-

tional borders present difficulties for economic historians, who search for consistent

the economy 99

100 peter wardley

series that will allow investigation of long-run change, this has not been a major

impediment to the constructors of historical national accounts.

Underlying these vital but short-term vicissitudes there remain the dimensions and

trajectories of European “Modern Economic Growth.” This concept was proposed

by Simon Kuznets and it provides a more broadly based interpretation of economic

development than those suggested by explanations which stress an “Industrial

Revolution.” Kuznets constructed historical national income accounts to reveal popu-

lation growth, increased levels of consumption, rising savings and investment ratios

along with major sector shifts in production, with both the manufacturing and ser-

vices sectors expanding relative to the agricultural sector.

2

Adoption of this framework

permits a quantitative appraisal of the characteristics of European economic growth

and a relative assessment of economic performance.

One distinguished economic growth accountant, and arguably the most

prominent in the field, is Angus Maddison and, if we seek a consistent view of

European performance between 1900 and 1945, it is to Maddison’s data that we

turn in order to examine national economic performance.

3

His national income

estimates, which are calculated in constant prices, allow a number of comparative

points to be made.

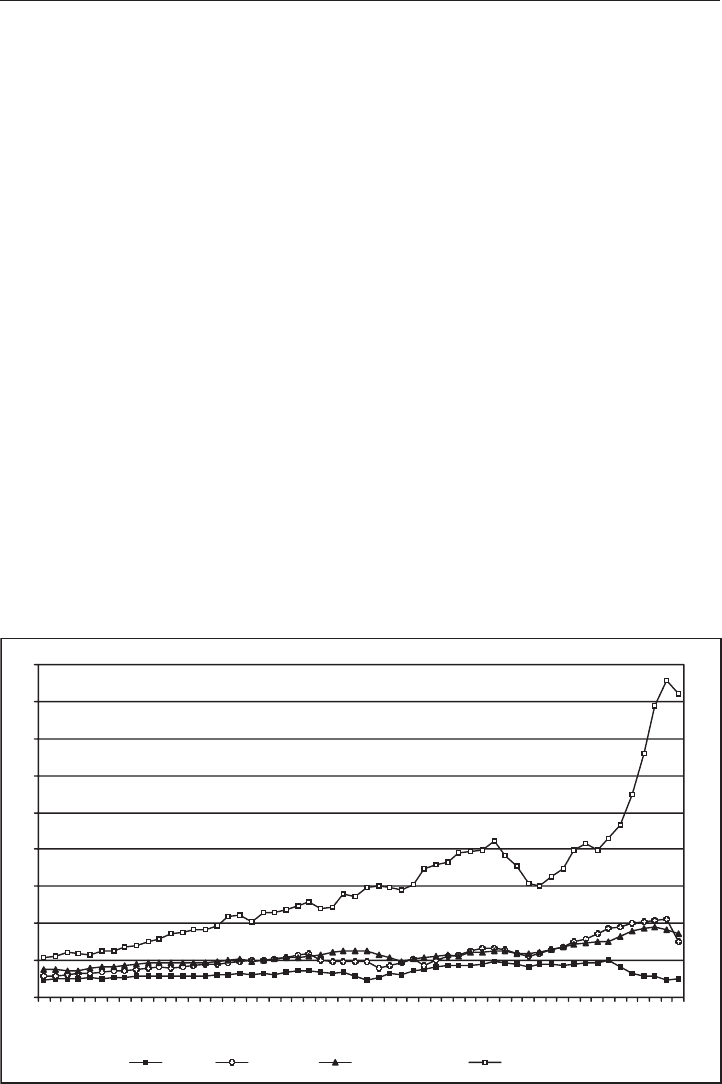

First, the US economy was much larger than that of any single European nation;

this is shown in figure 7.1, which illustrates the growth path of national income in

the largest economies of western Europe (the United Kingdom, Germany, and

France) and the US between 1890 and 1945. The overall pattern is unsurprising:

slow but steady growth was achieved in northwest Europe – although the two world

wars interrupted this progress while the Great Depression caused a pause in growth

Figure 7.1 Western European and US national income, 1890–1945 (1990 Geary-Khamis

international dollars, millions). From Maddison, The World Economy.

France Germany United Kingdom United States

the economy 101

from which Germany and Britain slowly recovered. During the interwar years French

national income barely grew and it diminished significantly in the years of German

occupation. In stark contrast stands the American experience of sustained and rela-

tively stable growth until 1929, when a sharp fall marked the Great Depression, after

which there was recovery which, after a brief pause in 1938, became rapid expansion

as the American economy was mobilized for World War II. Maddison’s data also

indicates that it was only during World War II that the national income of the United

States exceeded aggregate European income.

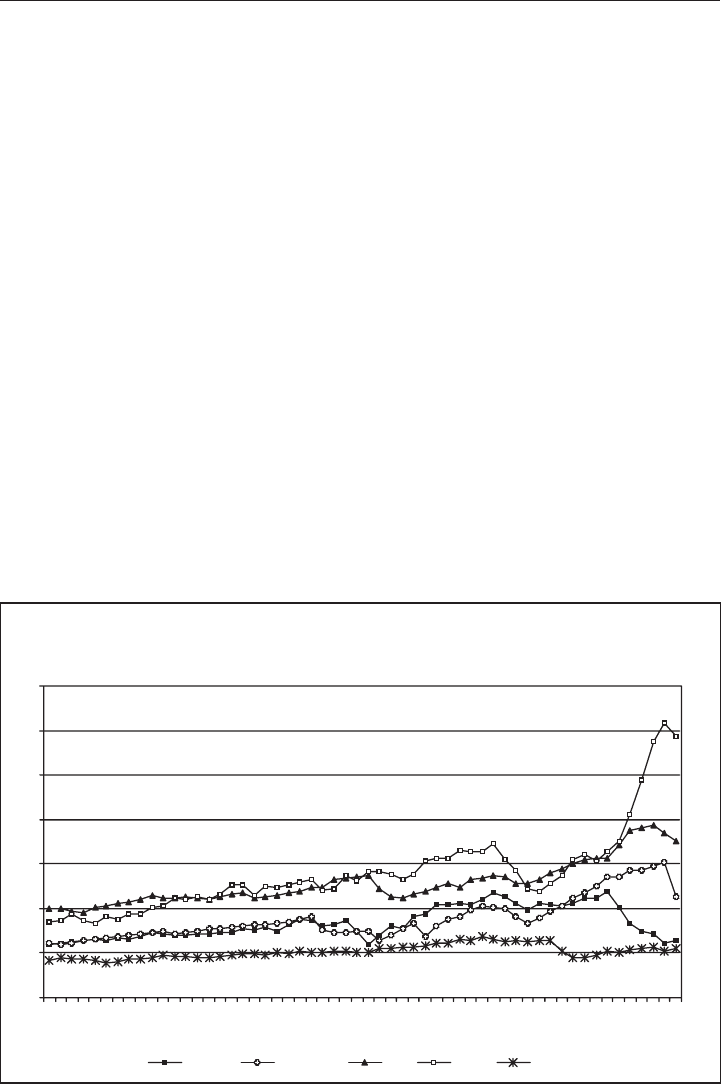

Second, as figure 7.2 shows, per capita incomes in Europe, estimated as national

income, defined as above in constant income terms, divided by total population,

varied considerably. Before World War I British per capita income ran in step with

that of America, with both economies demonstrating a steady increase. American per

capita income level surged ahead in the “Roaring Twenties,” while those in Britain

sagged in the postwar doldrums, recovering slowly before 1931. Thereafter, freed

from the gold standard, British per capita income rose steadily until World War II,

matching the American level through the 1930s. Although this was a diminished

standard, because per capita income in the USA was reduced by the impact of the

Depression, only recovering the 1929 level under the stimulus of World War II, for

Britain this represented a significant increase in average income per head over the

interwar period. Per capita incomes in France and Germany also ran neck-and-neck,

and significantly lower than those achieved in Britain, until the Great War, which

depressed incomes. In the 1920s France recovered sooner than did Germany, and

appears to have maintained a small lead until the mid-1930s, when stagnation set in.

France Germany UK USA Spain

Figure 7.2 European and US per capita income, 1890–1945 (1990 Geary-Khamis interna-

tional dollars per head of population). From Maddison, The World Economy.

102 peter wardley

The impact of German occupation on France’s national income is clearly visible in

the fall of per capita income after 1939. Germany, by contrast, after a slow and halting

recovery in the 1920s, appears to have experienced rising per capita income until the

final stages of World War II. After forty years of slow per capita income growth, civil

war in Spain produced a clear fall which was barely restored by 1945, and throughout

this period Spanish per capita incomes were significantly lower than those achieved

during peacetime in the economies of northwestern Europe.

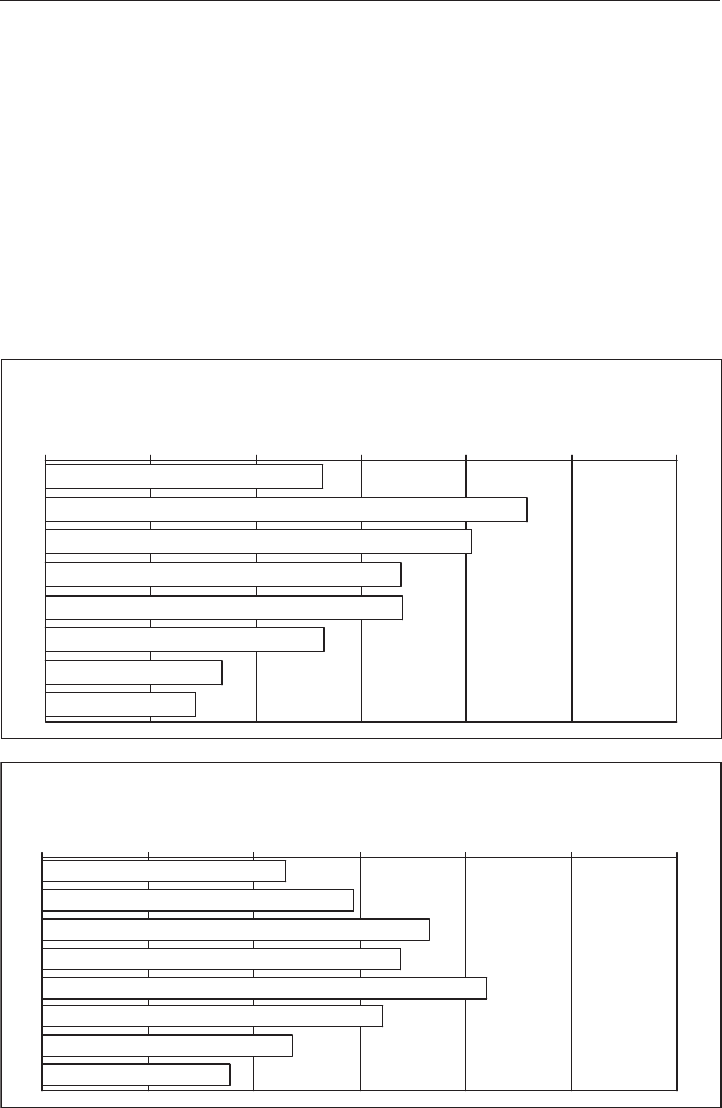

With Maddison’s data we can also compare the per capita income achieved in

different economies to examine the disparities between nations within Europe. Figure

7.3 shows income per capita represented as two transverse views of Europe to dem-

onstrate variations from west to east and from north to south in 1912 (American per

capita income provides a useful comparator and it is presented as the base index of

100). This figure shows a relatively small gap of about 10 percent between American

Relative GDP per capita in 1912 – transverse West to East

0 20 40 60 80

100

120

Ireland

Great Britain

Belgium

France

Germany

Austria-Hungary

Romania

Russia

Relative GDP per capita in 1912 – transverse North to South

0 20

40

60 80

100

120

Norway

Sweden

Denmark

Germany

Switzerland

NW ltaly

N & C ltaly

S ltaly

Figure 7.3 European relative per capita income in 1912 (US = 100). From Maddison, The

World Economy; Zamagni, Economic History of Italy.

the economy 103

per capita income and that achieved in Great Britain which, in turn, held a similar

lead over Switzerland and Belgium. Germany and France, despite their different

economic structures, had per capita incomes which were almost identical. In 1912

Ireland, Norway, Austria-Hungary, and north and central Italy all achieved similar

per capita income levels, which were approximately half of that estimated for the

United States. By contrast, as shown by the Russian, Romanian, and Italian econo-

mies, the eastern and southern margins of Europe experienced lower per capita

incomes than northwest Europe, with per capita income equivalent to about 30

percent of that of the United States.

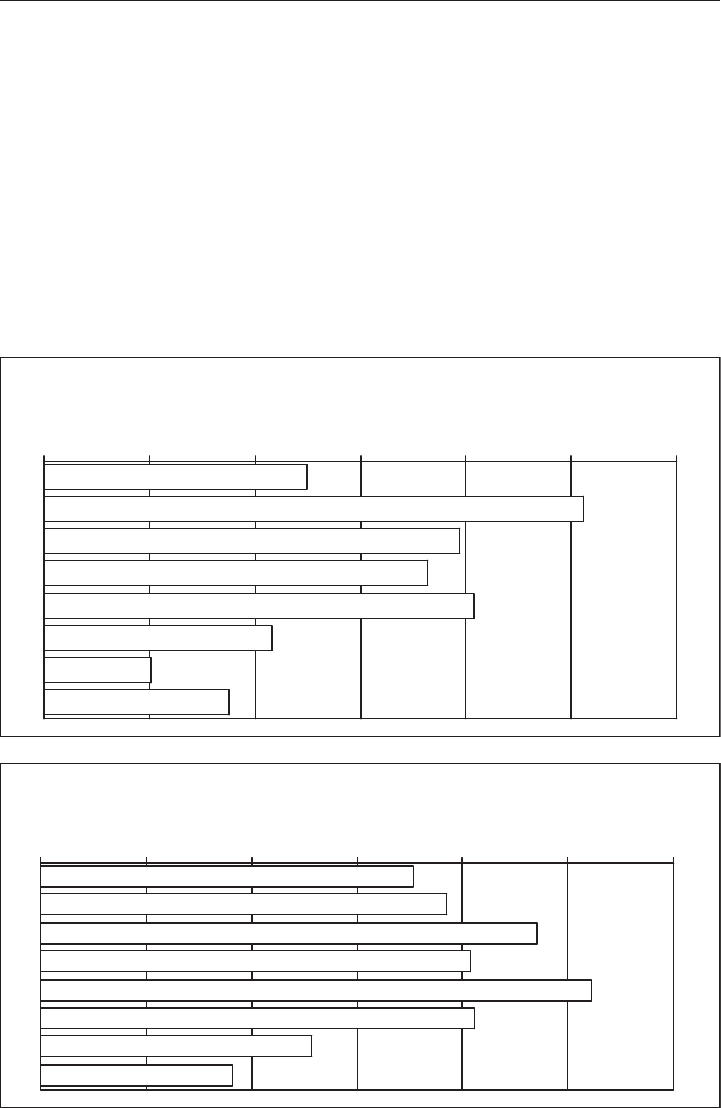

How did the European geographical pattern of per capita income change between

1912 and 1938? Figure 7.4 allows us to adopt the same metric and consider the same

geographical traverses across Europe to answer this question. Here the most striking

feature is the improved relative performance of both Great Britain and Switzerland,

Relative GDP per capita in 1938 – transverse North to South

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Relative GDP per capita in 1938 – transverse West to East

0 20

40

60 80

100

120

Ireland

Belgium

France

Germany

Hungary

Romania

USSR

Great Britain

Norway

Sweden

Denmark

Germany

Switzerland

NW ltaly

N & C ltaly

S ltaly

Figure 7.4 European relative per capita income in 1938 (US = 100). From Maddison, The

World Economy; Zamagni, Economic History of Italy.

104 peter wardley

as both had at least achieved parity with US per capita income. However, with the

American economy still recovering from the Great Depression, and controversy over

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal unabated, the diminished status of the

American standard has to be recognized. Great Britain still led its closer neighbors,

Belgium, France and Germany, and its relative lead had altered by little over the

quarter century, during which all had experienced economic growth and higher per

capita incomes. In the 1930s the Scandinavian economies, closely associated with

Great Britain and members of the sterling area, and benefiting from the recovery of

the now protectionist British economy, recovered quickly from relatively mild reces-

sion. In Sweden this was assisted by a counter-cyclical fiscal policy introduced by the

Social Democrats in response to unemployment that anticipated Keynesian prescrip-

tions. Taken as a group these northwestern European economies resemble a “con-

vergence club” as their growing per capita incomes rose together. This was not the

case for Ireland or for Hungary; economic independence and the opportunity to

introduce economic policies demanded by nationalists had yielded little in the way

of economic benefits to either economy. By this measure of relative economic per-

formance little change is indicated for southern or northern and central Italy as a

consequence of policies introduced by Mussolini’s fascist regime, though the north-

west of Italy saw expansion of the industrial sector and an enhanced level of per capita

income. Finally, by this measure, the USSR had made some small progress relative

to its tsarist past, though as a broadly based indicator of economic activity, per capita

income does not reflect the enormous expansion of industry which had taken place

in the 1930s.

Taking a long-run view of European economic growth, the important issues for

economists (who are more surprised that history is important than historians) relate

to economic growth, convergence, and divergence. Where historians assume that

historical differences will be caused by different conditions arising from the past and

then explain, at least in part, developments in the ensuing period, economists worry

about why these differences exist and persist. In the economist’s world, as envisioned

in the neoclassical model defined by mobile factors of production, free and full trans-

fers of information, especially technology, and open economies, differences in income

should be removed as economic convergence occurs.

As a consequence, a crucial question for economists, looking at the period

before World War I, especially as economic conditions in this period of history most

closely reflected the assumptions employed in the economists’ model, is the extent to

which convergence occurred – or did not. Although not optimal, the pre-1914 inter-

national economy was remarkably unfettered. There were frictions. For example, the

US experienced extensive industrialization while its markets for manufactured goods

derived benefits from high tariffs and import duties, which were probably unnecessary

and even unjustifiable, even in terms of protection for “infant industries,” but these

were far from burdensome. Generally, tariffs were low, trade was unhindered, capital

moved freely, and postal, telegram, and telephone communications fostered relatively

inexpensive rapid exchanges of information. These factors encouraged mobility and

millions of people, especially from Italy, the UK, and Germany, left Europe to migrate

to the “New Worlds,” with the US the major beneficiary of this flow of workers and

consumers. This was the world which died in the summer of 1914 – thereby bringing

to an end the international economy’s first experience of globalization.

4

the economy 105

By contrast, the interwar period is seen by economists in a most unpromising

light. It began with the creation of national states that reflected neither markets, nor

established trading patterns, nor areas of product specialization and interrelatedness.

To this depleted recipe for economic prosperity was added the collapse of Middle

Europe’s transport systems as mistrust even prevented trains from crossing new

international borders – lest they never return. Although the restoration of peace saw

the reestablishment of economic activity, production, investment, trade, and inter-

national capital flows looked all too often like pale impressions of those which had

been achieved before the war.

5

The protracted establishment of international exchange

parities between 1924 and 1928 effectively resulted in competitive devaluations,

while long-term monetary stability was also compromised by large stocks of poten-

tially volatile funds and the contentious question of reparation payments.

6

Furthermore,

as a result of a shift in the balance of world financial power, effective international

economic leadership in a crisis had also become problematic. Britain, previously

regarded as the world’s undisputed banker, faced potentially serious liquidity prob-

lems as a consequence of wartime expenditure and inter-Allied lending, whereas the

contender for the role of financial world leader was a reluctant, and perhaps naive,

United States, which had emerged from the war as the world’s major international

creditor.

7

Further difficulties accumulated as the prices of primary goods, agricultural prod-

ucts, and industrial raw materials fell significantly and, as Kindleberger graphically

demonstrates, between 1929 and 1933 world trade collapsed into a black hole.

8

If

the economic problems which prompted recession were international and structural,

these difficulties were significantly exacerbated by the introduction of deflationary

government policies. Although the blame for the depression is often laid at the

door of the New York Stock Exchange, which suffered a stock market price fall in

1929, a partial recovery in 1930, but then the long slide to collapse in 1931, it was

the sharp downturn in economic activity caused by government induced deflation

rather than excessive speculation which generated the unique conditions of the early

1930s. In the United States the introduction of the Hawley-Smoot tariff in 1930

provoked retaliation and further contraction of world trade, and the failure of the

US Federal Reserve Board to confront the collapse of the American banking system

with an increase in the money supply resulted in external and internal shockwaves

that reverberated around the world economy. The international monetary system

failed to provide effective cooperation in 1931 as a banking crisis unfolded across

central Europe, sweeping away the Austrian Creditanstalt and then the German Danat

Bank before threatening London.

The protracted but ultimately futile struggle engaged in by British monetary

authorities in the autumn of 1931, as they attempted to keep the pound sterling on

the gold standard, was symbolic of the disruption of economic progress which was

seen nostalgically by many to have characterized the world before 1914. By contrast,

the 1930s saw the United States withdraw from the world economy as it increased

tariffs, reduced trade, devalued the dollar, raised interest rates, and reduced interna-

tional private investment. European governments responded with national economic

programs designed to achieve fiscal “retrenchment” that reduced income, introduced

“beggar-thy-neighbor” tariffs that distorted trade patterns, and created protectionist

trading blocs. As the threat of war grew, autarchic systems were crafted by statesmen

106 peter wardley

that prioritized strategic and military objectives rather than expansion of the inter-

national economy.

9

If one extreme case was provided by the Soviet economy, with

its centralized planning system directed according to priorities of the Soviet

Communist Party, another was Nazi Germany, where the will of the Fuhrer was

implemented by state agencies that had been transformed into adjuncts of the

National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), but which developed into unco-

ordinated fiefdoms dominated by high ranking Nazis. Even the British retreated from

the international economy to some extent after the British Commonwealth of Nations

agreed a system of preferential tariffs at the 1932 Ottawa Imperial Conference. The

World Economic Conference held in London the following year failed to provide

any impetus towards a reduction in protectionist attitudes. In this environment,

international economic prospects were less than propitious. And, when they met at

the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, it was this state of affairs that the policy

makers of the United Nations countries were so desperate to avoid as they deliberated

upon the establishment of the postwar international economic order.

10

Between 1900 and 1945 Europe was twice stricken by previously unimagined

international conflict. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that significant economic prog-

ress was achieved during this period. To some contemporaries it appeared that, with

appropriate national and international policies, the possibility of growth and prosper-

ity was not far fetched. A number of material and social indicators suggested that

World War II could be followed by better times and the plans made for the return

of peace explicitly considered how these might be achieved. This prospect inspired

those who were given the task, by their respective governments, of drawing up pro-

grams for the new postwar economic order. However, the destructive impact of the

two world wars, the bitter experience of the Great Depression, the poisonous legacy

which haunted all the many countries which had suffered civil war or invasion, and

the ubiquitous dread of unemployment all color our view of the period to the extent

that much that was positive is easily lost from view.

Enterprises and Economic Performance

The story so far has looked more closely at one side of economic activity: an investi-

gation of the growth of national income and of per capita income in the European

countries between 1914 and 1945 not only explores economic performance at a

highly aggregated level – that of the nation-state – but also focuses on income rather

than production. While the close relationship between income and production ensures

that in most cases the aggregate picture will be very similar, if not identical, the

attainment and organization of production is, in itself, important. To present a bal-

anced picture, we must augment an investigation of national income with an exami-

nation of the productive enterprise. Here we look to business history.

Business history investigates the activities of firms or enterprises. Enterprises orga-

nize the activities which result in the production of goods and services. Enterprises

come in all sizes: they range from the independent cobbler or lawyer, who works

alone as an owner-manager, to the giant multinational which employs hundreds of

managers and overseers (foremen) who, respectively, plan and supervise the daily toil

of thousands of workers employed in a number of different countries. It is within

the enterprise that production is organized. And it is the effectiveness, or efficiency,

the economy 107

with which the owners and managers of enterprises combine the factors of production

– land, labor, and capital – that determines productivity and, ultimately, incomes and

living standards.

In the context of this essay, this begs two questions: first, how did Europeans

organize production at the beginning of the twentieth century? And, secondly, how

effective were the people who took the decisions about what to produce and how to

produce goods and services? These are very important questions because they allow

us to test many of the judgments which have been offered by historians about the

nature and effectiveness of national economic performance in this period. Here

perhaps the most obvious example is the not uncommon insistence in the literature

that the British economy “failed.” Within the field of business history the assertion

has been made that this was because there was a “failure of British entrepreneurship.”

However, similar gloomy stories have been told about French businessmen, who are

alleged to have been too traditional in their approach to business and innovation,

and Russian capitalists, who are charged with timidity and deference because of their

failure to challenge the traditional anti-capitalist mentalities of the Russian governing

class. And as the German bourgeoisie is often accused of accepting an inferior role

in the Kaiserreich, and Italian businessmen are suspected of being adverse to competi-

tion, if not incompetent, the emerging pattern would suggest either that enterprises

across Europe were run, for the most part, by a rather unenterprising bunch or,

perhaps, that some historians have rushed to offer convenient but overdrawn conclu-

sions. The obvious comparator here is the performance of American enterprise;

however, as the standard offered to arrive at this verdict is not uncommonly unspoken,

this gauge is not always explicit. Nonetheless, this comparative perspective permits

an assessment of European enterprise.

In terms of employment, the majority of enterprises, on both sides of the Atlantic,

were small ones, and these provided income for the majority of the occupied labor

force. The most frequently occurring enterprise in Europe was the family farm. In

this, Europe was not unusual, as this was true of most of the world’s richer economies

in 1900. In the United States, for example, the “typical” or “representative” enter-

prise, the most commonly occurring firm, was the family-owned farm which employed

permanently few, if any, additional workers; and this remained the case until well

into the twentieth century. At the turn of the century only in Britain, Europe’s most

advanced economy, had the primary sector, consisting of farming, fishing, and for-

estry, become the smallest of the three major economic sectors, though even here

agriculture was to remain a significant employer of labor until after World War II. In

1939 the primary sector was still the predominant one in the Balkans, Iberia, Italy,

and eastern Europe and nearly three-quarters of Europe’s agrarian workforce were

employed in these areas – where labor productivity was relatively low. By contrast,

in the high income per capita economies (see figure 7.3) the industrial and services

sectors employed three-quarters of the labor force and produced an even larger share

of national income.

Europe consisted of a large number of agricultural regions and a great variety of

agrarian practices; history collaborated with geography to determine regional and

local specializations so that there was considerable variation in the nature of agricul-

ture practices. Reluctance to leave the land was also an almost universal sentiment,

which was most often broken by economic necessity, persecution, or ambition. Not