McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

complementary goods in consumption. Similarly, the effect of a change in the price

of resource A on the demand for resource B depends on their substitutability or their

complementarity in production.

SUBSTITUTE RESOURCES

Suppose the technology in a certain production process is such that labour and cap-

ital are substitutable. A firm can produce some specific amount of output using a rel-

atively small amount of labour and a relatively large amount of capital, or vice

versa. Now assume that the price of machinery (capital) falls. The effect on the

demand for labour will be the net result of two opposed effects: the substitution

effect and the output effect.

● Substitution effect The decline in the price of machinery prompts the firm to

substitute machinery for labour. This substitution allows the firm to produce

its output at a lower cost. So, at the fixed wage rate, smaller quantities of

labour are now employed. This substitution effect decreases the demand for

labour. More generally, the substitution effect indicates that a firm will pur-

chase more of an input whose relative price has declined and, conversely, use

less of an output whose relative price has increased.

● Output effect Because the price of machinery has fallen, the costs of produc-

ing various outputs must also decline. With lower costs, the firm finds it prof-

itable to produce and sell a greater output. The greater output increases the

demand for all resources, including labour. So, this output effect increases the

demand for labour. More generally, the output effect means that the firm will

purchase more of one particular input when the price of the other input falls

and less of that particular input when the price of the other input rises.

● Net effect The substitution and output effects are both present when the price

of an input changes, but they work in opposite directions. For a decline in the

price of capital, the substitution effect decreases the demand for labour and the

output effect increases it. The net change in labour demand depends on the rel-

ative sizes of the two effects.

In terms of resource demand, if the substitution effect outweighs the output effect,

a decrease in the price of capital decreases the demand for labour. If the output effect

exceeds the substitution effect, a decrease in the price of capital increases the

demand for labour.

COMPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Recall from Chapter 3 that certain products, such as cameras and film or computers

and software, are complementary goods; they go together and are jointly

demanded. Resources may also be complementary; an increase in the quantity of

one of them used in the production process requires an increase in the amount used

of the other as well, and vice versa. Suppose a small design firm does computer-

assisted design (CAD) with relatively expensive personal computers as its basic

piece of capital equipment. Each computer requires a single design engineer to oper-

ate it; the machine is not automated—it will not run itself—and a second engineer

would have nothing to do.

Now assume that a technological advance in the production of these comput-

ers substantially reduces their price. No substitution effect can occur, because

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 361

substitu-

tion effect

A firm will purchase

more of an output

whose relative price

has declined and

use less of an input

whose relative price

has increased.

output

effect

An

increase in the price

of one input will

increase a firm’s

production costs

and reduce its level

of output, thus re-

ducing the demand

for other outputs

(and vice versa).

labour and capital must be used in fixed proportions, one person for one machine.

Capital cannot be substituted for labour. But there is an output effect. Other

things equal, the reduction in the price of capital goods means lower production

costs. It will, therefore, be profitable to produce a larger output. In doing so, the

firm will use both more capital and more labour. When labour and capital are

complementary, a decline in the price of capital increases the demand for labour through the

output effect.

We have cast our analysis of substitute resources and complementary resources

mainly in terms of a decline in the price of capital. In Table 14-3 we summarize

the effects of an increase in the price of capital on the demand for labour; study it

carefully.

Now that we have discussed the full list of the determinants of labour demand,

let’s again review their effects. Stated in terms of the labour resource, the demand

for labour will increase (the labour demand curve will shift rightward) when

● The demand for (and therefore the price of) the product produced by that

labour increases.

● The productivity (MP) of labour increases.

● The price of a substitute input decreases, provided the output effect exceeds the

substitution effect.

● The price of a substitute input increases, provided the substitution effect

exceeds the output effect.

● The price of a complementary input decreases.

Be sure that you can reverse these effects to explain a decrease in labour demand.

Table 14-4 provides several illustrations of the determinants of labour demand,

listed by the categories of determinants we have discussed; give them a close look.

362 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

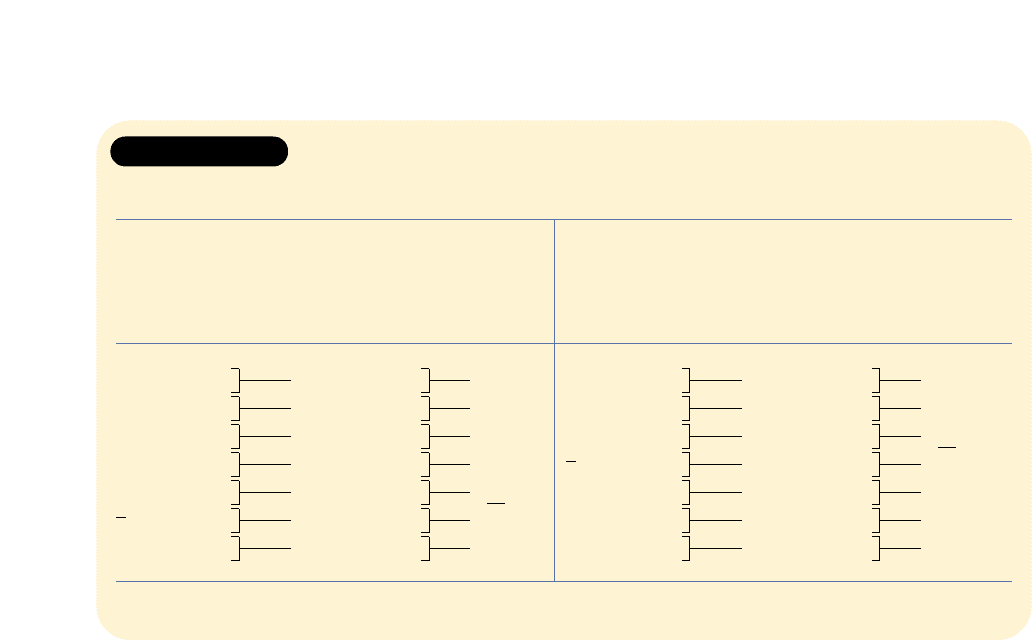

TABLE 14-3 THE EFFECT OF AN INCREASE IN THE PRICE OF

CAPITAL ON THE DEMAND FOR LABOUR, D

L

(1) (2)

Relationship Increase in the price of capital

of inputs

(a) (b) (c)

Substitution Output effect Combined effect

effect

Substitutes in Labour substituted Production costs up, D

L

increases if the

production for capital output down, and less substitution effect exceeds

of both capital and the output effect; D

L

labour used decreases if the output

effect exceeds the

substitution effect

Complements No substitution Production costs up, D

L

decreases

in production of labour for capital output down, and less

of both capital and

labour used

Occupational Employment Trends

Changes in labour demand have considerable significance, since they affect wage

rates and employment in specific occupations. Increases in labour demand for certain

occupational groups result in increases in their employment, and decreases in labour

demand result in decreases in their employment. For illustration, let’s look at occu-

pations that are growing in demand. (Wage rates are the subject of the next chapter).

THE FASTEST GROWING OCCUPATIONS

The occupations that are growing quickly in the Canadian economy tend to be service

occupations. In general, the demand for service workers is rapidly outpacing the

demand for manufacturing, construction, and mining workers. The top five fastest

growing jobs are directly computer-related. The increase in the demand for computer

engineers, computer support specialists, systems analysts, database managers, and

desktop publishing specialists relates to the rapid rise in the demand for computers,

computer services, and the Internet. It also relates to the rising productivity of these par-

ticular workers, given the vastly improved quality of the computer and communica-

tions equipment they work with. Price declines on such equipment have had a stronger

output effect than substitution effect, increasing the demand for these types of labour.

Three of the other fastest growing occupations relate to health care: personal care

and home health care aides, medical assistants, and physician assistants. The grow-

ing demands for these types of labour are derived from the growing demand for

health services, caused by several factors. The aging of the Canadian population has

brought with it more medical problems, and the rising standard of income has led

to greater expenditures on health care.

The employment changes we have just discussed result from shifts in the locations

of resource demand curves. Such changes in demand must be distinguished from

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 363

TABLE 14-4 DETERMINANTS OF LABOUR DEMAND: FACTORS

THAT SHIFT THE LABOUR DEMAND CURVE

Determinant Examples

Changes in Gambling increases in popularity, increasing the demand for workers at casinos.

product Consumers decrease their demand for leather coats, decreasing the demand for tanners.

demand The federal government reduces spending on the military, reducing the demand for

military personnel.

Changes in An increase in the skill levels and output of glassblowers increases the demand for

productivity their services.

Computer-assisted graphic design increases the productivity of, and demand for,

graphic artists.

Changes in An increase in the price of electricity increases the cost of producing aluminum and

the price reduces the demand for aluminum workers.

of another The price of security equipment used by businesses to protect against illegal entry

resource falls, decreasing the demand for night guards.

The price of telephone switching equipment decreases, greatly reducing the cost of

telephone service, which in turn increases the demand for telemarketers.

Elasticity of Resource Demand

<www.adin.org/lmi/

fastest.htm>

Fastest growing and

declining occupations,

Ontario, 1995–2005

changes in the quantity of a resource demanded caused by a change in the price

of the specific resource under consideration. Such a change is not caused by a shift

of the demand curve but rather by a movement from one point to another on a fixed

resource demand curve. For example, in Figure 14-1 we note that an increase in the

wage rate from $5 to $7 will reduce the quantity of labour demanded from five to

four units. This is a change in the quantity of labour demanded as distinct from a change

in demand.

The sensitivity of producers to changes in resource prices is measured by the

elasticity of resource demand. In coefficient form,

E

rd

=

When E

rd

is greater than one, resource demand is elastic; when E

rd

is less than one,

resource demand is inelastic; and when E

rd

equals one, resource demand is unit-

elastic. (Recall from Chapter 6 that demand elasticity has a negative sign, but we use

the absolute value.) What determines the elasticity of resource demand? Several fac-

tors are at work.

RATE OF MP DECLINE

A purely technical consideration is the rate at which the marginal product of the

particular resource declines. If the marginal product of one resource declines slowly

as it is added to a fixed amount of other resources, the demand (MRP) curve for that

resource declines slowly and tends to be highly elastic. A small decline in the price

of such a resource will yield a relatively large increase in the amount demanded.

Conversely, if the marginal product of the resource declines sharply as more of it is

added, the resource demand curve also declines rapidly. This means that a relatively

large decline in the wage rate will be accompanied by a modest increase in the

amount of labour hired; labour demand is inelastic.

EASE OF RESOURCE SUBSTITUTABILITY

The degree to which resources are substitutable is also a determinant of elasticity. The

larger the number of satisfactory substitute resources available, the greater the elasticity of

demand for a particular resource. If a furniture manufacturer finds that five or six dif-

ferent types of wood are equally satisfactory in making coffee tables, a rise in the

price of any one type of wood may cause a sharp drop in the amount demanded as

the producer substitutes one of other woods. At the other extreme, no reasonable

substitutes may exist; bauxite is absolutely essential in the production of aluminum

ingots. Thus, the demand for bauxite by aluminum producers is inelastic.

Time can play a role in the input substitution process. For example, a firm’s truck

drivers may obtain a substantial wage increase with little or no immediate decline

in employment. But over time, as the firm’s trucks wear out and are replaced, that

wage increase may motivate the company to purchase larger trucks and in that

way deliver the same total output with fewer drivers. Another example is the new

commercial aircraft that require only two cockpit personnel rather than the former

three, again indicating some substitutability between labour and capital if there is

enough time.

ELASTICITY OF PRODUCT DEMAND

The elasticity of demand for any resource depends on the elasticity of demand for

the product it helps produce. The greater the elasticity of product demand, the greater

percentage change in resource quantity

ᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in resource price

364 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

elasticity

of resource

demand

The

percentage change

in resource quantity

divided by the per-

centage change in

resource price.

the elasticity of resource demand. The derived nature of resource demand leads us

to expect this relationship. A small rise in the price of a product with great elas-

ticity of demand will sharply reduce output, bringing about relatively large de-

clines in the amounts of various resources demanded; the demand for the resource

is elastic.

Remember that the resource demand curve of Figure 14-1 is more elastic than the

resource demand curve shown in Figure 14-2. The difference arises because in Fig-

ure 14-1, we assume a perfectly elastic product demand curve, while Figure 14-2 is

based on a downsloping or less than perfectly elastic product demand curve.

RATIO OF RESOURCE COST TO TOTAL COST

The larger the proportion of total production costs accounted for by a resource, the greater

the elasticity of demand for that resource. In the extreme, if labour cost is the only pro-

duction cost, then a 20 percent increase in wage rates will shift all the firm’s cost

curves upward by 20 percent. If product demand is elastic, this substantial increase

in costs will cause a relatively large decline in sales and a sharp decline in the

amount of labour demanded. So labour demand is highly elastic. But if labour cost

is only 50 percent of production cost, then a 20 percent increase in wage rates

will increase costs by only 10 percent. With the same elasticity of product demand,

this will cause a relatively small decline in sales and, therefore, in the amount

of labour demanded. In this case the demand for labour is much less elastic. (Key

Question 3)

So far our main focus has been on one variable input, labour. But in the long run,

firms can vary the amounts of all the resources they use. That’s why we need to con-

sider what combination of resources a firm will choose when all its inputs are vari-

able. While our analysis is based on two resources, it can be extended to any

number of inputs.

We will consider two interrelated questions:

1. What combination of resources will minimize costs at a specific level of output?

2. What combination of resources will maximize profit?

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 365

Optimal Combination of Resources

● A resource demand curve will shift because of

changes in product demand, changes in the

productivity of the resource, and changes in

the prices of other inputs.

● If resources A and B are substitutable, a decline

in the price of A will decrease the demand for

B provided the substitution effect exceeds the

output effect. If the output effect exceeds the

substitution effect, the demand for B will

increase.

● If resources C and D are complements, a decline

in the price of C will increase the demand for D.

● Elasticity of resource demand measures the

extent to which producers change the quantity

of a resource they hire when its price changes.

● The elasticity of resource demand will be less

the more rapid the decline in marginal product,

the smaller the number of substitutes, the

smaller the elasticity of product demand, and

the smaller the proportion of total cost ac-

counted for by the resource.

Choosing

a Little More

or Less

The Least-Cost Rule

A firm is producing a specific output with the least-cost combination of resources

when the last dollar spent on each resource yields the same marginal product. That is, the

cost of any output is minimized when the ratios of marginal product to price of the

last units of resources used are the same for each resource. In competitive resource

markets marginal resource cost is the market resource price; the firm can hire as

many or as few units of the resources as it wants at that price. Then, with just two

resources, labour and capital, a competitive firm minimizes its total cost of a specific

output when

= (1)

Throughout, we will refer to the marginal products of labour and capital as MP

L

and

MP

C

, respectively, and symbolize the price of labour by P

L

and the price of capital

by P

C

.

A concrete example shows why fulfilling the condition in equation (1) leads to

least-cost production. Assume that the price of both capital and labour is $1 per unit,

but that they are currently employed in such amounts that the marginal product of

labour is 10 and the marginal product of capital is 5. Our equation immediately tells

us that this is not the least costly combination of resources:

>

Suppose the firm spends $1 less on capital and shifts that dollar to labour. It loses

five units of output produced by the last dollar’s worth of capital, but it gains 10

units of output from the extra dollar’s worth of labour. Net output increases by 5

(= 10 – 5) units for the same total cost. More such shifting of dollars from capital to

labour will push the firm down along its MP curve for labour and up along its MP

curve for capital, increasing output and moving the firm toward a position of equi-

librium where equation (1) is fulfilled. At that equilibrium position, the MP per dol-

lar for the last unit of both labour and capital might be, for example, seven. The firm

will be producing a greater output for the same (original) cost.

Whenever the same total resource cost can result in a greater total output, the cost

per unit—and therefore the total cost of any specific level of output—can be

reduced. Being able to produce a larger output with a specific total cost is the same

as being able to produce a specific output with a smaller total cost. If the firm in our

example buys $1 less of capital, its output will fall by five units. If it spends only $.50

of that dollar on labour, the firm will increase its output by a compensating five

units (=

1

⁄2 of the MP per dollar). Then the firm will realize the same total output at

a $.50 lower total cost.

The cost of producing any specific output can be reduced as long as equation (1)

does not hold. But when dollars have been shifted between capital and labour to the

point where equation (1) holds, no additional changes in the use of capital and

labour will reduce costs further. The firm is now producing that output using the

least-cost combination of capital and labour.

All the long-run cost curves developed in Chapter 8 and used thereafter assume that the

least-cost combination of inputs has been realized at each level of output. Any firm that com-

bines resources in violation of the least-cost rule would have a higher-than-necessary

average total cost at each level of output; that is, it would incur X-inefficiency, as dis-

cussed in Figure 10-7.

MP

C

× 5

ᎏ

P

C

× $1

MP

L

× 10

ᎏᎏ

P

L

× $1

Marginal Product of Capital (MP

c

)

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

Price of Capital (P

c

)

Marginal Product of Labour (MP

L

)

ᎏᎏᎏᎏ

Price of Labour (P

L

)

366 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

least-

cost combi-

nation of

resources

The quantity of

each resource a

firm must employ to

produce a particular

output at the lowest

total cost.

The producer’s least-cost rule is analogous to the consumer’s utility-maximizing

rule described in Chapter 7. In achieving the utility-maximizing combination of

goods, consumers consider both their preferences, as reflected in diminishing-

marginal-utility data, and the prices of the various products. Similarly, in achieving

the cost-minimizing combination of resources, producers consider both the mar-

ginal product data and the price (costs) of the various resources.

The Profit-Maximizing Rule

Minimizing cost is not sufficient for maximizing profit. A firm can produce any level

of output in the least costly way by applying equation (1), but only one unique

level of output can maximize profit. Our earlier analysis of product markets showed

that this profit-maximizing output occurs where marginal revenue equals marginal

cost (MR = MC). Near the beginning of this chapter, we determined that we could

write this profit-maximizing condition as MRP = MRC as it relates to resource

inputs.

In a purely competitive resource market, the marginal resource cost (MRC) is

exactly equal to the resource price, P. Thus, for any competitive resource market, we

have as our profit-maximizing equation

MRP (resource) = P (resource)

This condition must hold for every variable resource and in the long run all

resources are variable. In competitive markets, a firm will, therefore, achieve its

profit-maximizing combination of resources when each resource is employed to

the point at which its marginal revenue product equals its price. For two resources,

labour and capital, we need both P

L

= MRP

L

and P

C

= MRP

C

We can combine these conditions by dividing both sides of each equation by their

respective prices and equating the results, to get

= = 1 (2)

Note in equation (2) that it is not sufficient that the MRPs of the two resources be

proportionate to their prices; the MRPs must be equal to their prices and the ratios,

therefore, equal to one. For example, if MRP

L

= $15, P

L

= $5, MRP

C

= $9, and P

C

= $3,

the firm is underemploying both capital and labour even though the ratios of MRP

to resource price are identical for both resources. The firm can expand its profit by

hiring additional amounts of both capital and labour until it moves down their

downsloping MRP curves to the points at which MRP

L

= $5 and MRP

C

= $3. The

ratios will then be 5/5 and 3/3 and equal to one.

The profit-maximizing position in equation (2) includes the cost-minimizing con-

dition of equation (1). That is, if a firm is minimizing profit according to equation

(2), then it must be using the least-cost combination of inputs to do so. However, the

converse is not true: a firm operating at least cost according to equation (1) may not

be operating at the output that maximizes its profit.

Numerical Illustration

A numerical illustration will help you understand the least-cost and profit-

maximizing rules. In columns 2, 3, 2⬘, and 3⬘ in Table 14-5, we show the total prod-

ucts and marginal products for various amounts of labour and capital that are

assumed to be the only inputs needed in producing some product, say, key chains.

Both inputs are subject to diminishing returns.

MRP

C

ᎏ

P

C

MRP

L

ᎏ

P

L

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 367

profit-

maximizing

combina-

tion of

resources

The quantity of

each resource a

firm must employ

to maximize its

profits or minimize

its losses.

We also assume that labour and capital are supplied in competitive resource mar-

kets at $8 and $12, respectively, and that key chains sell competitively at $2 per unit.

For both labour and capital, we can determine the total revenue associated with

each input level by multiplying total product by the $2 product price. These data are

shown in columns 4 and 4⬘. They enable us to calculate the marginal revenue prod-

uct of each successive input of labour and capital as shown in columns 5 and 5⬘,

respectively.

PRODUCING AT LEAST COST

What it the least-cost combination of labour and capital to use in producing, say, 50

units of output? The answer, which we can obtain by trial and error, is three units

of labour and two units of capital. Columns 2 and 2⬘ indicate that this combination

of labour and capital does, indeed, result in the required 50 (= 28 + 22) units of out-

put. Now, note from columns 3 and 3⬘ that hiring three units of labour gives us

MP

L

/P

L

=

6

⁄8 =

3

⁄4, and hiring two units of capital gives us MP

C

/P

C

=

9

⁄12 =

3

⁄4. So, equa-

tion (1) is fulfilled. How can we verify that costs are actually minimized? First, we

see that the total cost of employing three units of labour and two of capital is $48

[= (3 × $8) + (2 × $12)].

Other combinations of labour and capital will also yield 50 units of output but at

a higher cost than $48. For example, five units of labour and one unit of capital will

produce 50 (= 37 + 13) units, but total cost is higher at $52 [= (5 × $8) + (1 × $12)].

This result comes as no surprise, because five units of labour and one unit of capi-

tal violate the least-cost rule—MP

L

/P

L

=

4

⁄8, MP

C

/P

C

=

13

⁄12. Only the combination

(three units of labour and two units of capital) that minimizes total cost will satisfy

equation (1). All other combinations capable of producing 50 units of output violate

the cost-minimizing rule, and, therefore, cost more than $48.

TABLE 14-5 DATA FOR FINDING THE LEAST-COST AND

PROFIT-MAXIMIZING COMBINATION OF

LABOUR AND CAPITAL*

LABOUR (PRICE = $8) CAPITAL (PRICE = $12)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)

Quantity Total Marginal Total Marginal Quantity Total Marginal Total Marginal

product product revenue revenue product product revenue revenue

(output) product (output) product

00

12

$0

$24

00

13

$0

$26

112

10

24

20

113

9

26

18

222

6

44

12

222

6

44

12

328

5

56

10

3 28

4

56

8

433

4

66

8

432

3

64

6

5 37

3

74

6

535

2

70

4

640

2

80

4

637

1

74

2

7 42 84 7 38 76

*To simplify, it is assumed in this table that the productivity of each resource is independent of the quantity of the other. For

example, the total and marginal product of labour is assumed not to vary with the quantity of capital employed.

368 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

MAXIMIZING PROFIT

Will 50 units of output maximize the firm’s profit? No, because the profit-maximizing

terms of equation (2) are not satisfied when the firm employs three units of labour

and two of capital. To maximize profit, each input should be employed until its price

equals its marginal revenue product. But for three units of labour, labour’s MRP in

column 5 is $12 while its price is only $8; the firm could increase its profit by hiring

more labour. Similarly, for two units of capital, we see in column 5⬘ that capital’s

MRP is $18 and its price is only $12. This result indicates that more capital should

also be employed. By producing only 50 units of output (even though they are pro-

duced at least cost), labour and capital are being used in less-than-profit-maximizing

amounts. The firm needs to expand its employment of labour and capital, thereby

increasing its output.

Table 14-5 shows that the MRPs of labour and capital are equal to their prices, so

that equation (2) is fulfilled when the firm is employing five units of labour and three

units of capital. This is the profit-maximizing combination of inputs.

2

The firm’s total

cost will be $76, made up of $40 (= 5 × $8) of labour and $36 (= 3 × $12) of capital. Total

revenue will be $130, found either by multiplying the total output of 65 (= 37 + 28)

by the $2 product price or by summing the total revenues attributable to labour ($74)

and to capital ($56). The difference between total revenue and total cost in this

instance is $54 (= $130 – $76). Experiment with other combinations of labour and cap-

ital to demonstrate that they yield an economic profit of less than $54.

Note that the profit-maximizing combination of five units of labour and three

units of capital is also a least-cost combination for this particular level of output.

Using these resource amounts satisfies the least-cost requirement of equation (1) in

that MP

L

/P

L

=

4

⁄8 =

1

⁄2 and MP

C

/P

C

=

6

⁄12 =

1

⁄2. (Key Questions 4 and 5)

Our discussion of resource pricing is the cornerstone of the controversial view that

fairness and economic justice are two of the outcomes of a competitive capitalist

economy. Table 14-5 tells us, in effect, that workers receive income payments (wages)

equal to the marginal contributions they make to their employers’ outputs and rev-

enues. In other words, workers are paid according to the value of the labour services

that they contribute to production. Similarly, owners of the other resources receive

income based on the value of the resources they supply in the production process.

In this marginal productivity theory of income distribution, income is distrib-

uted according to the contribution to society’s output. So, if you are willing to accept

the ethical proposition “To each according to what he or she creates,” income pay-

ments based on marginal revenue product seem to provide a fair and equitable dis-

tribution of society’s income.

This idea sounds fair enough, but there are serious criticisms of this theory of

income distribution;

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 369

2

Because we are dealing with discrete (nonfractional) units of the two outputs here, the use of

four units of labour and two units of capital is equally profitable. The fifth unit of labour’s MRP

and its price (cost) are equal at $8, so that the fifth labour unit neither adds to nor subtracts from

the firm’s profit; similarly, the third unit of capital has no effect on profit.

marginal

productiv-

ity theory

of income

distribution

The contention that

the distribution of

income is fair when

each unit of each

resource receives a

money payment

equal to its mar-

ginal contribution

to the firm’s rev-

enue (its marginal

revenue product).

Marginal Productivity Theory

of Income Distribution

● Inequality Critics argue that the distribution of income resulting from pay-

ment according to marginal productivity may be highly unequal because pro-

ductive resources are very unequally distributed in the first place. Aside from

their differences in mental and physical attributes, individuals encounter sub-

stantially different opportunities to enhance their productivity through edu-

cation and training. Some people may not be able to participate in production

at all because of mental or physical disabilities, and they would obtain no

income under a system of distribution based solely on marginal productivity.

Ownership of property resources is also highly unequal. Many landlords and

capitalists obtain their property by inheritance rather than through their own

productive effort. Hence, income from inherited property resources conflicts

with the “To each according to what he or she creates” idea. This reasoning

calls for government policies that modify the income distributions made

strictly according to marginal productivity.

● Market Imperfections The marginal productivity theory rests on the assump-

tions of competitive markets. Yet labour markets, for example, are riddled with

imperfections, as you will see in Chapter 15. Some employers exert pricing

power in hiring workers. And some workers, through labour unions, profes-

sional associations, and occupational licensing laws, wield monopoly power

in selling their services. Even the process of collective bargaining over wages

suggests a power struggle over the division of income. In this struggle, mar-

ket forces—and income shares based on marginal productivity—may get

pushed into the background. In addition, discrimination in the labour market

can distort earnings patterns. In short, because of real-world market imper-

fections, wage rates and other resource prices frequently are not based solely

on contributions to output.

370 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

As you have learned from this

chapter, a firm achieves its least-

cost combination of inputs when

the last dollar it spends on each

input makes the same contribu-

tion to total output. This raises an

interesting real-world question:

What happens when technologi-

cal advance makes available a

new, highly productive capital

good for which MP/P is greater

than it is for other inputs, say a

particular type of labour? The an-

swer is that the least-cost mix of

resources abruptly changes and

the firm responds accordingly. If

the new capital is a substitute

for labour (rather than a comple-

ment), the firm replaces the par-

ticular type of labour with the

new capital. That is exactly what

is happening in the banking in-

dustry, in which ATMs are replac-

ing human bank tellers.

ATMs made their debut about

30 years age when Diebold, a

U.S. firm, introduced the prod-

uct. Today, Diebold and NCR

(also a U.S. firm) dominate

global sales, with the Japanese

firm Fujitsu a distant third. The

number of ATMs and their usage

have exploded, and currently

INPUT SUBSTITUTION:

THE CASE OF ATMS

Banks are using more automatic teller machines (ATMs)

and employing fewer human tellers.