McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 371

more than 26,000 ATMs are used

in Canada. We rank number one

in the world in ATM use, logging

53 transactions per Canadian

in 1997, followed by the United

State at 41.4 and Sweden at 37.6.

There are now 709,000 ATMs

worldwide.

ATMs are highly productive:

A single machine can handle

hundreds of transactions daily,

thousands weekly, and millions

over the course of several years.

ATMs can not only handle cash

withdrawals, but they can also

accept deposits and facilitate

switches of funds between vari-

ous accounts. Although ATMs

are expensive for banks to buy

and install, they are available

24 hours a day, and their cost

per transaction is one-fourth the

cost for human tellers. They

rarely get held up, and they do

not quit their jobs (turnover

among human tellers is nearly

50 percent per year). ATMs are

highly convenient; unlike human

tellers, they are located not only

at banks but also at busy street

corners, workplaces, universi-

ties, and shopping malls. The

same bankcard that enables you

to withdraw cash from your local

ATM also enables you to with-

draw pounds from an ATM in

London, yen from an ATM

in Tokyo, and even rubles from

an ATM in Moscow. (All this,

of course, assumes that you

have money in your account.)

In the terminology of this

chapter, the more productive,

lower-priced ATMs have reduced

the demand for a substitute in

production—human tellers. Be-

tween 1990 and 2000, 6000

human teller positions were

eliminated, and half the remain-

ing teller positions may be gone

by 2010. Where will the people

holding these jobs go? Most will

eventually move to other occu-

pations. Although the lives of

individual tellers are disrupted,

society clearly wins. Society

gets cheaper, more convenient

banking services and more of

the other goods that these freed-

up labour resources help to

produce.

Source: Based partly on Ben Craig,

“Where Have All the Tellers Gone?”

Economic Commentary (Federal

Reserve Bank of Cleveland), April.

15, 1997; and statistics provided by

the Canadian Bankers Association.

chapter summary

1. Resource prices act as a determinant of money

incomes, and they simultaneously ration

resources to various industries and firms.

2. The demand for any resource is derived

from the product it helps produce. That

means the demand for a resource will

depend on its productivity and on the market

value (price) of the good it is producing.

3. Marginal revenue product is the extra rev-

enue a firm obtains when it employs one

more unit of a resource. The marginal-

revenue-product curve for any resource is the

demand curve for that resource, because the

firm equates resource price and MRP in deter-

mining its profit-maximizing level of resource

employment. Thus, each point on the MRP

curve indicates how many resource units the

firm will hire at a specific resource price.

4. The firm’s demand curve for a resource

slopes downward, because the marginal

product of additional units declines in accor-

dance with the law of diminishing returns.

When a firm is selling in an imperfectly

competitive market, the resource demand

curve falls for a second reason: Product price

must be reduced for the firm to sell a larger

output. We can derive the market demand

curve for a resource by summing horizon-

tally the demand curves of all the firms hir-

ing that resource.

5. The demand curve for a resource will shift as

the result of (a) a change in the demand for,

and therefore the price of, the product the

resource is producing; (b) changes in the

productivity of the resource; and (c) changes

in the prices of other resources.

terms and concepts

372 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

6. If resources A and B are substitutable for

each other, a decline in the price of A will

decrease the demand for B provided the sub-

stitution effect is greater than the output

effect. But if the output effect exceeds the

substitution effect, a decline in the price of A

will increase the demand for B.

7. If resources C and D are complementary or

jointly demanded, there is only an output

effect; a change in the price of C will change

the demand for D in the opposite direction.

8. The majority of the fastest growing occupa-

tions in Canada relate to computers or health

care.

9. The elasticity of demand for a resource

measures the responsiveness of producers to

a change in the resource’s price. The coeffi-

cient of the elasticity of resource demand is

E

rd

When E

rd

is greater than one, resource de-

mand is elastic; when E

rd

is less than one,

resource demand is inelastic; and when E

rd

equals one, resource demand is unit elastic.

10. The elasticity of demand for a resource will

be greater (a) the more slowly the marginal

product of the resource declines, (b) the

larger the number of good substitute

resources available, (c) the greater the elas-

ticity of demand for the product, and (d) the

larger the proportion of total production

costs attributable to the resource.

11. Any specific level of output will be produced

with the least costly combination of variable

resources when the marginal product per

dollar’s worth of each input is the same—

that is, when

=

12. A firm is employing the profit-maximizing

combination of resources when each re-

source is used to the point where its mar-

ginal revenue product equals its price. In

terms of labour and capital, that occurs

when the MRP of labour equals the price of

labour and the MRP of capital equals the

price of capital—that is, when

= = 1

13. The marginal productivity theory of income

distribution holds that all resources are paid

what they are economically worth: their mar-

ginal contribution to output. Critics assert

that such an income distribution is too

unequal and the real-world market imperfec-

tions result in pay above and below mar-

ginal contributions to output.

MRP of Capital

ᎏᎏ

Price of Capital

MRP of Labour

ᎏᎏ

Price of Labour

MP of Capital

ᎏᎏ

Price of Capital

MP of Labour

ᎏᎏ

Price of Labour

percentage change in resource quantity

ᎏᎏᎏᎏᎏ

percentage change in resource price

derived demand, p. 353

marginal product (MP), p. 355

marginal revenue product

(MRP), p. 355

marginal resource cost

(MRC), p. 356

MRP = MRC rule, p. 356

substitution effect, p. 361

output effect, p. 361

elasticity of resource demand,

p. 364

least-cost combination of

resources, p. 366

profit-maximizing

combination of resources,

p. 367

marginal productivity theory

of income distribution,

p. 369

study questions

1. What is the significance of resource pricing?

Explain how the factors determining resource

demand differ from those underlying product

demand. Explain the meaning and signifi-

cance of the fact that the demand for a re-

source is a derived demand. Why do resource

demand curves slope downward?

2.

KEY QUESTION Complete the follow-

ing labour demand table for a firm that is hir-

ing labour competitively and selling its prod-

uct in a competitive market.

a. How many workers will the firm hire if

the market wage rate is $27.95? $19.95?

Explain why the firm will not hire a larger

or smaller number of units of labour at

each of these wage rates.

b. Show in schedule form and graphically the

labour demand curve of this firm.

chapter fourteen • the demand for resources 373

c. Now redetermine the firm’s demand curve

for labour, assuming that it is selling in an

imperfectly competitive market and that,

although it can sell 17 units at $2.20 per

unit, it must lower product price by 5 cents

to sell the marginal product of each suc-

cessive labour unit. Compare this demand

curve with that derived in question 2b.

Which curve is more elastic? Explain.

Units Marginal

of Total Marginal Product Total revenue

labour product product price revenue product

00

_____

$2 $_____

$_____

117

_____

2 _____

_____

231

_____

2 _____

_____

343

_____

2 _____

_____

453

_____

2 _____

_____

560

_____

2 _____

_____

6 65 2 _____

3.

KEY QUESTION What factors deter-

mine the elasticity of resource demand? What

effect will each of the following have on the

elasticity or the location of the demand for

resource C, which is being used to produce

commodity X? Where there is any uncertainty

as to the outcome, specify the causes of that

uncertainty.

a. An increase in the demand for product X

b. An increase in the price of substitute re-

source D

c. An increase in the number of resources

substitutable for C in producing X

d. A technological improvement in the capi-

tal equipment with which resource C is

combined

e. A decline in the price of complementary

resource E

f. A decline in the elasticity of demand for

product X due to a decline in the competi-

tiveness of the product market

4.

KEY QUESTION Suppose the produc-

tivity of capital and labour are as shown in

the accompanying table. The output of these

resources sells in a purely competitive market

for $1 per unit. Both capital and labour are

hired under purely competitive conditions at

$3 and $1, respectively.

Units of MP of Units of MP of

capital capital labour labour

0

24

0

11

1

21

1

9

2

18

2

8

3

15

3

7

4

9

4

6

5

6

5

4

6

3

6

1

7

1

7

1

⁄2

88

a. What is the least-cost combination of

labour and capital the firm should employ

in producing 80 units of output? Explain.

b. What is the profit-maximizing combination

of labour and capital the firm should use?

Explain. What is the resulting level of out-

put? What is the economic profit? Is this

the least costly way of producing the

profit-maximizing output?

5.

KEY QUESTION In each of the follow-

ing four cases, MRP

L

and MRP

C

refer to the

marginal revenue products of labour and capi-

tal, respectively, and P

L

and P

C

refer to their

prices. Indicate in each case whether the condi-

tions are consistent with maximum profits for

the firm. If not, state which resource(s) should

be used in larger amounts and which re-

source(s) should be used in smaller amounts.

a. MRP

L

= $8; P

L

= $4; MRP

C

= $8; P

C

= $4

b. MRP

L

= $10; P

L

= $12; MRP

C

= $14; P

C

= $9

c. MRP

L

= $6; P

L

= $6; MRP

C

= $12; P

C

= $12

d. MRP

L

= $22; P

L

= $26; MRP

C

= $16; P

C

= $19

6. Florida citrus growers say that the recent

crackdown on illegal immigration is increasing

the market wage rates necessary to get their

oranges picked. Some are turning to $100,000

to $300,000 mechanical harvesters known

as “trunk, shake, and catch” pickers, which

vigourously shake oranges from the trees. If

widely adopted, what will be the effect on the

demand for human orange pickers? What does

that imply about the relative strengths of the

substitution and output effects?

7. (The Last Word) Explain the economics of the

substitution of ATMs for human tellers. Some

banks are beginning to assess transaction

fees when customers use human tellers rather

than ATMs. What are these banks trying to

accomplish?

374 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

internet application questions

1. Go to Human Resource and Development

Canada at <www11.hrdc-drhc.gc.ca/jf-ea/

jf.prospects_by_current1?p_rating=1> to de-

termine the specific employment outlooks for

several occupations. For which job are

prospects good now but only fair in 2004?

2. Increases in employment reflect increases in

labour demand, accompanied by increases in

labour supply. Go the Bureau of Labour Sta-

tistics at <stat.bls.gov/top20.html> and select

International Labour Statistics (at the bottom).

Find the percentage increases in employment

for the United States, Japan, Germany, France,

Great Britain, Italy, and Canada for the most

recent 10-year period. Which three countries

have had the fastest growth of labour demand,

as measured by the employment outcome?

which three the slowest?

IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER

Y

Y

OU WILL LEARN:

OU WILL LEARN:

That wages are determined

by demand and supply forces.

•

About the effects of

monopoly power on the

demand and supply of labour.

•

The pros and cons of

a minimum wage.

•

The effects of labour

market discrimination.

•

The effects of immigration on

domestic labour markets.

Wage

Determination,

Discrimination,

and

Immigration

N

early 15 million of us go to work each

day in Canada. We work at an amazing

variety of jobs for thousands of differ-

ent firms for considerable differences in pay.

What determines our hourly wage or annual

salary? Why is the salary for, say, a top major

league baseball player $18 million a year,

whereas the pay for a first-rate schoolteacher

is $60,000? Why are starting salaries for uni-

versity graduates who major in engineering

and accounting so much higher than for grad-

uates majoring in journalism and sociology?

FIFTEEN

Having explored the major factors that underlie labour demand, we now bring

labour supply into our analysis to help answer these questions. Generally, labour sup-

ply and labour demand interact to determine the hourly wage rate or annual salary

in each occupation. Collectively, those wages and salaries make up about 70 percent

of the national income.

Economists use the term “labour” broadly to apply to (1) blue-collar and white-col-

lar workers of all varieties; (2) professional people such as lawyers, physicians, den-

tists, and teachers; and (3) owners of small businesses, including barbers, plumbers,

television repairers, and a host of retailers who provide labour as they carry on their

own businesses.

Wages are the price that employers pay for labour. Wages may take the form of

salaries, bonuses, royalties, or commissions. We will use the term “wages” to mean

the wage rate per hour, per day, and so forth. That usage will remind us that a wage

rate is a price paid per unit of labour services. It will also let us distinguish between

the wage rate and labour earnings, the latter being determined by multiplying the

number of hours worked per week, per month, or per year by the hourly wage or

wage rate.

We must also distinguish between nominal wages and real wages. A nominal

wage is the amount of money received per hour, per day, and so on. A real wage is

the quantity of goods and services a worker can obtain with nominal wages; real

wages reveal the purchasing power of nominal wages.

Your real wage depends on your nominal wage and the prices of the goods and

services you purchase. Suppose you receive an 8 percent increase in your nominal

wage during a certain year, but in that same year the price level increases by 5 per-

cent. Then your real wage has increased by 3 percent (= 8 percent minus 5 percent).

Unless otherwise indicated, we will assume that the overall level of prices remains

constant. In other words, we will discuss only real wages.

Wages differ among nations, regions, occupations, and individuals. Wage rates are

much higher in Canada than in China or India. Wages are slightly higher in the

south and west of Canada than in the north. Plumbers are paid less than NHL

hockey players, and lawyer Adam may earn twice as much as lawyer Bharti for the

same number of hours of work. Wage rates also differ by gender, race, and ethnic

background.

The general, or average, level of wages, like the general level of prices, includes

a wide range of different wage rates. It includes the wages of bakers, barbers, brick

masons, and brain surgeons. By averaging such wages, we can more easily compare

wages among regions and among nations.

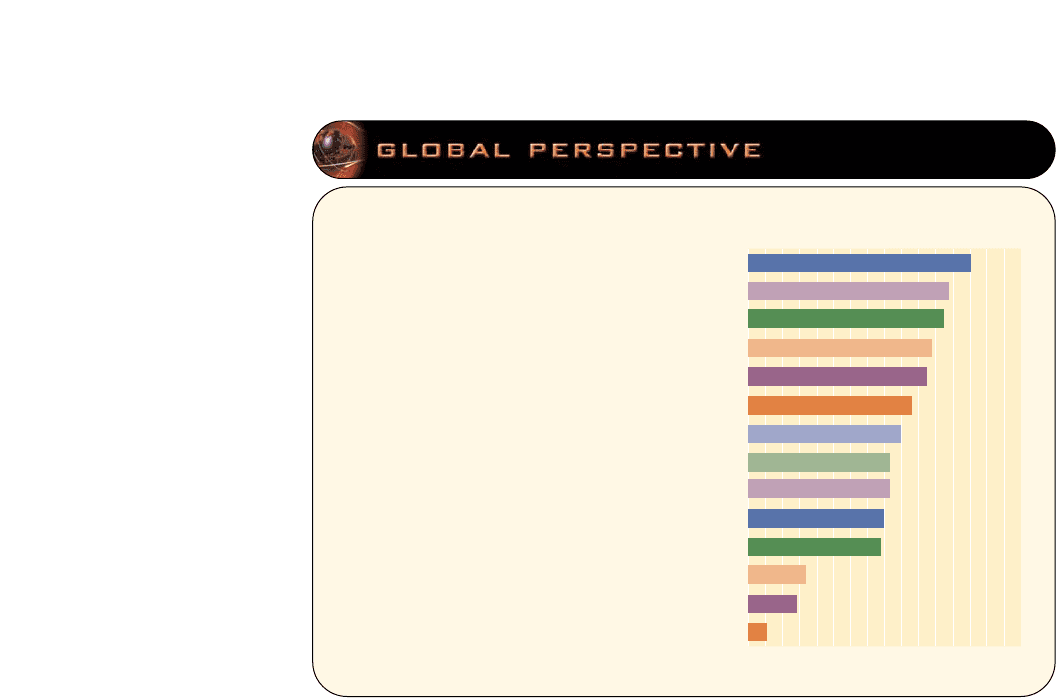

As Global Perspective 15.1 suggests, the general level of real wages in Canada is

relatively high—although not the highest in the world.

The simplest explanation for the high real wages in Canada and other industri-

ally advanced economies (referred to hereafter as advanced economies) is that

the demand for labour in these nations is relatively large compared to the supply

of labour.

376 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

Labour, Wages, and Earnings

nominal

wage

The

amount of money

received by a

worker per unit

of time (hour,

day, etc.).

real wage

The amount of

goods and services

a worker can pur-

chase with a nomi-

nal wage.

General Level of Wages

<www.internationalecon.

com/v1.0/ch40/

40c200.html>

The real wage

effects of free trade

The Role of Productivity

We know from the previous chapter that the demand for labour, or for any other

resource, depends on its productivity. Generally, the greater the productivity of

labour, the greater the demand for it. If the total supply of labour is fixed, then the

stronger the demand for labour, the higher the average level of real wages. The

demand for labour in Canada and the other major advanced economies is large

because labour in these countries is highly productive. There are several reasons for

that high productivity:

● Plentiful capital Workers in the advanced economies have access to large

amounts of physical capital equipment (machinery and buildings). The total

physical capital per worker in Canada is one of the highest in the world.

● Access to abundant natural resources In advanced economies, natural re-

sources tend to be abundant in relation to the size of the labour force. Some of

those resources are available domestically and others are imported from

abroad. Canada, for example, is richly endowed with arable land, mineral

resources, and sources of energy for industry.

● Advanced technology The level of technological progress is generally high in

advanced economies. Not only do workers in these economies have more cap-

ital equipment to work with but that equipment is also technologically supe-

rior to the equipment available to the vast majority of workers worldwide.

Work methods in the advanced economies are steadily being improved

through scientific study and research.

Hourly wages of

production workers,

selected nations

Wage differences are pro-

nounced worldwide. The

data shown here indicate

that hourly compensation in

Canada is not as high as in

some European nations. It is

important to note, however,

that the prices of goods and

services vary greatly among

nations, and the process of

converting foreign wages into

dollars may not accurately

reflect such variations.

15.1

048121620242832

Germany

Denmark

United Kingdom

Canada

Taiwan

Mexico

Hourly Pay in U.S. Dollars, 1999

Korea

Switzerland

Sweden

France

Italy

United States

Japan

Australia

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, <stat.bls.gov>, 2000.

chapter fifteen • wage determination, discrimination, and immigration 377

● Labour quality The health, vigour, education, and training of workers in

advanced economies are generally superior to those in developing nations,

which means that, even with the same quantity and quality of natural and cap-

ital resources, workers in advanced economies tend to be more efficient than

many of their foreign counterparts.

● Intangible factors Less tangible factors also may underlie the high produc-

tivity in some of the advanced economies. In Canada, for example, such fac-

tors include (1) the efficiency and flexibility of management; (2) business,

social, and political environments that emphasize production and productiv-

ity; and (3) the vast size of the domestic market, which enables firms to engage

in mass production.

Real Wages and Productivity

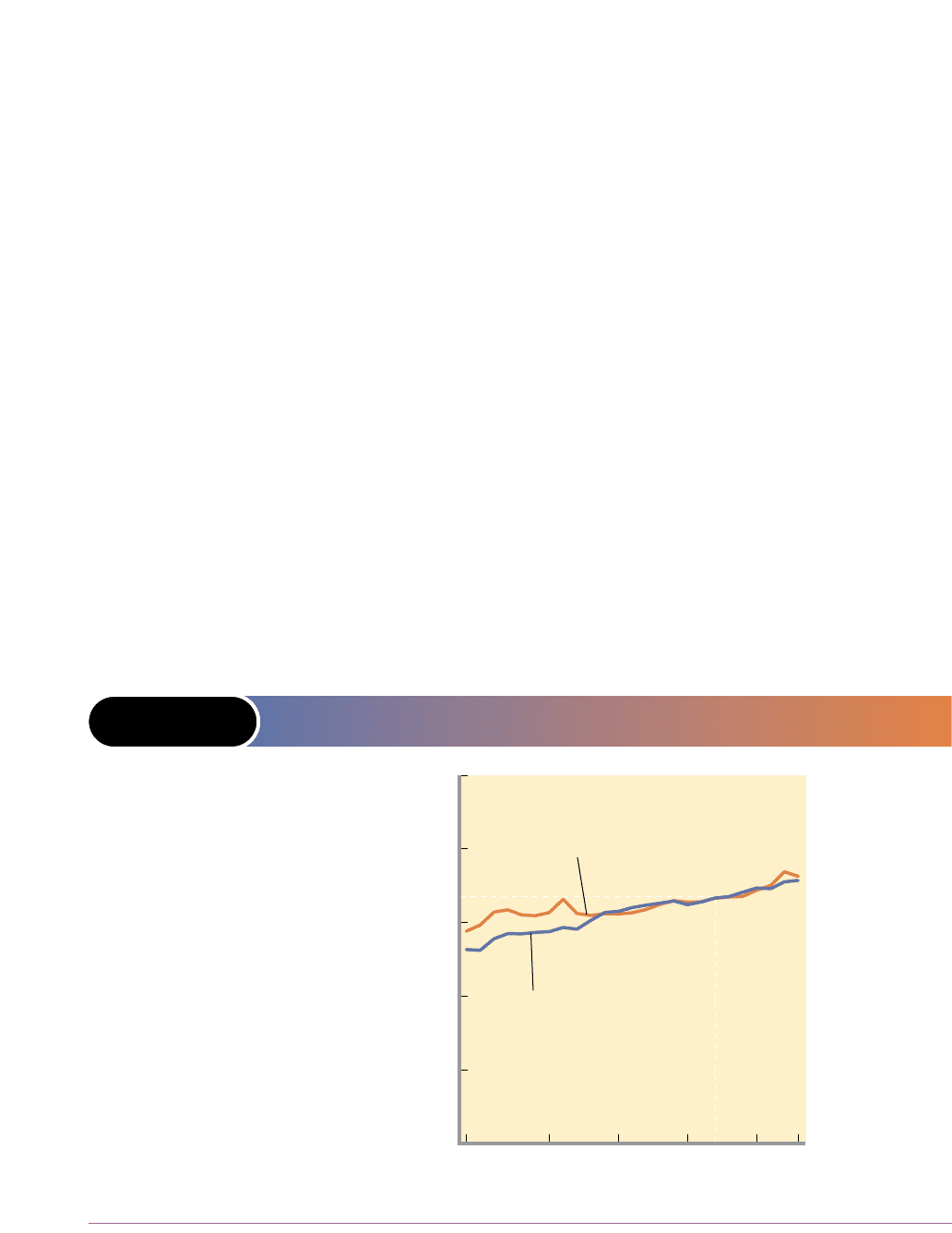

Figure 15-1 shows the close long-run relationship between output per hour of work

and real hourly earnings in Canada. Because real income and real output are two

ways of viewing the same thing, real income (earnings) per worker can increase

only at about the same rate as output per worker. When workers produce more

real output per hour, more real income is available to distribute to them for each

hour worked.

In the real world, however, suppliers of land, capital, and entrepreneurial talent

also share in the income from production. Real wages, therefore, do not always rise

in lockstep with gains in productivity over short spans of time. But over long peri-

ods, productivity and real wages tend to rise together.

378 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

FIGURE 15-1 OUTPUT PER HOUR AND REAL HOURLY EARNINGS

IN CANADA

Index (1992 = 100)

Output per person-hour

Real compensation

per person-hour

0

30

60

90

100

120

150

199819951990198519801974

Over the years a

close relationship

exists between

output per hour of

work and real hourly

earnings.

Source: Statistics Canada.

Secular Growth of Real Wages

Basic supply and demand analysis helps explain the long-term trend of real-wage

growth in Canada. The nation’s labour force has grown significantly over the

decades, but, as a result of the productivity-increasing factors we have mentioned,

labour demand has increased more rapidly than labour supply. Figure 15-2 shows

several such increases in labour supply and labour demand. The result has been a

long-run, or secular, increase in wage rates and employment.

We now turn from the average level of wages to specific wage rates. What deter-

mines the wage rate paid for some specific type of labour? Demand and supply

analysis is again revealing. Let’s begin by examining labour demand and labour

supply in a purely competitive labour market. In this type of market

● Many firms compete with one another in hiring a specific type of labour.

● Each of numerous qualified workers with identical skills supplies that type of

labour.

● Individual firms and individual workers are wage-takers, since neither can

exert any control over the market wage rate.

Market Demand for Labour

Suppose 200 firms demand a particular type of labour, say carpenters. These firms

need not be in the same industry; industries are defined according to the products

they produce and not the resources they employ. Thus, firms producing wood-

framed furniture, wood windows and doors, houses and apartment buildings, and

wood cabinets will demand carpenters. To find the total, or market, labour demand

curve for a particular labour service, we sum horizontally the labour demand curves

(the marginal revenue product curves) of the individual firms, as indicated in Figure

15-3 (Key Graph). The horizontal summing of the 200 labour demand curves like d

in Figure 15-3(b) yields the market labour demand curve D in Figure 15-3(a).

chapter fifteen • wage determination, discrimination, and immigration 379

FIGURE 15-2 THE LONG-RUN TREND OF REAL WAGES IN CANADA

S

1900

S

1950

S

2000

S

2020

D

1900

D

1950

D

2000

D

2020

Real wage rate (dollars)

0

Q

Quantity of labour

The productivity of

Canadian labour has

increased substan-

tially over the long

run, causing the

demand for labour,

D, to shift rightward

(that is, to increase)

more rapidly than

increases in the

supply of labour, S.

The result has been

increases in real

wages.

purely

competitive

labour

market

A

resource market in

which a large num-

ber of (noncollud-

ing) firms demand

a particular type of

labour supplied by

a large number of

nonunion workers.

A Purely Competitive Labour Market

Choosing

a Little More

or Less

380 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

a

b

($10)

W

c

0

Q

c

Q

(5)

Wage rate (dollars)

(b) Individual firm

Quantity of labour

e

c

s

= MRC

d

= mrp

($10)

W

c

Wage rate (dollars)

0

Q

c

Q

(1000)

Quantity of labour

(a) Labour market

S

D

= MRP

(Σ mrp’s)

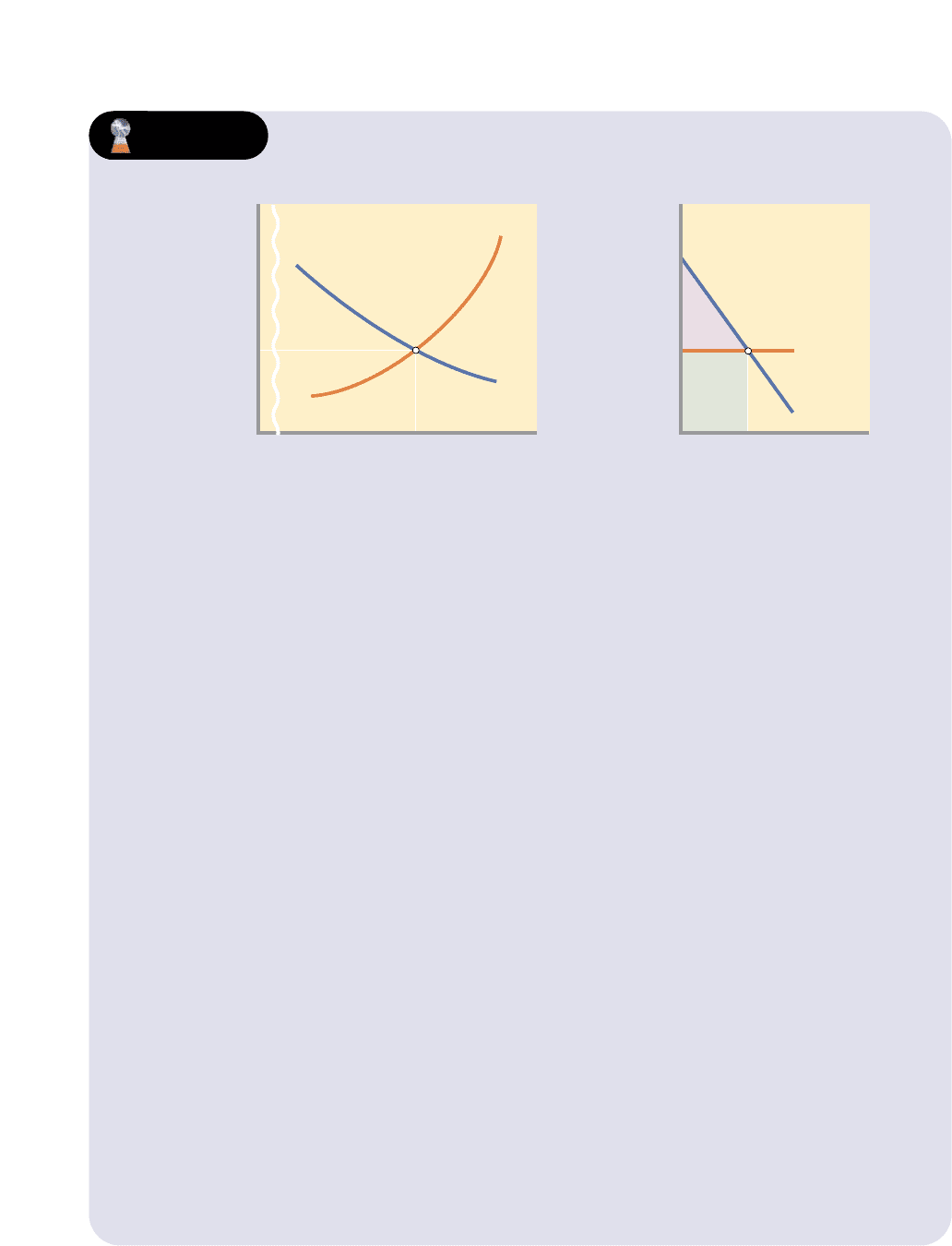

In a purely competitive labour market (panel a), the equilibrium wage rate, W

c

, and the number of workers, Q

c

, are deter-

mined by labour supply S and labour demand D. Because this market wage rate is given to the individual firm (panel b)

hiring in this market, its labour supply curve s = MRC is perfectly elastic. Its labour demand curve is its MRP curve (here

labelled mrp). The firm maximizes its profit by hiring workers up to where MRP = MRC. Area 0abc represents both the

firm’s total revenue and its total cost. The green area is its total wage cost; the lavender area is its nonlabour costs,

including a normal profit—that is, the firm’s payments to the suppliers of land, capital, and entrepreneurship.

FIGURE 15-3 LABOUR SUPPLY AND LABOUR DEMAND

IN (PANEL A) A PURELY COMPETITIVE LABOUR

MARKET AND (PANEL B) A SINGLE COMPETITIVE FIRM

Key Graph

Quick Quiz

1. The supply of labour curve S slopes upward in graph (a) because

a. the law of diminishing marginal utility applies.

b. the law of diminishing returns applies.

c. workers can afford to buy more leisure when their wage rates rise.

d. higher wages are needed to attract workers away from other labour markets,

household activities, and leisure.

2. This firm’s labour demand curve d in graph (b) slopes downward because

a. the law of diminishing marginal utility applies.

b. the law of diminishing returns applies.

c. the firm must lower its price to sell additional units of its product.

d. the firm is a competitive employer, not a monopsonist.

3. In employing five workers, the firm represented in graph (b)

a. has a total wage cost of $6000.

b. is adhering to the general principle of undertaking all actions for which the

marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost.

c. uses less labour than would be ideal from society’s perspective.

d. experiences increasing marginal returns.

4. A rightward shift of the labour supply curve in graph (a) would shift curve

a. d = mrp leftward in graph (b).

b. d = mrp rightward in graph (b).

c. s = MRC upward in graph (b).

d. s = MRC downward in graph (b).

Answers

1. d; 2. b; 3. b; 4. d