McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

then returned home, their enhanced human capital might make a substantial con-

tribution to economic development in Mexico.

FULL EMPLOYMENT VERSUS UNEMPLOYMENT

Our model assumes full employment in the sending and receiving countries. Mex-

ican workers presumably leave low-paying jobs to take (more or less immediately)

higher-paying jobs in Canada. However, in many cases the factor that “pushes”

immigrants from their homelands is not low wages but chronic unemployment and

underemployment. Many developing countries are overpopulated and have sur-

plus labour; workers are either unemployed or so grossly underemployed that their

marginal revenue product is zero.

If we allow for this possibility, then Mexico actually gains (not loses) by having

such workers emigrate. The unemployed workers are making no contribution to

Mexico’s domestic output and must be sustained by transfers from the rest of the

labour force. The remaining Mexican labour force will be better off by the amount

of the transfers after the unemployed workers have migrated to Canada. Con-

versely, if the Mexican immigrant workers are unable to find jobs in Canada and are

sustained through transfers from employed Canadian workers, then the after-tax

income of working Canadians will decline. (Key Question 17)

Immigration: Two Views

The traditional perception of immigration is that it consists of young, ambitious

workers seeking opportunity in Canada. They are destined for success because of the

courage and determination they exhibit in leaving their cultural roots to improve

their lives. These energetic workers increase the supply of goods and services with

their labour and simultaneously increase the demand for goods and services with

their incomes and spending. In short, immigration is an engine of economic progress.

The counterview is that immigration is a socioeconomic drag on the receiving

country. Immigrants compete with domestic workers for scarce jobs, pull down the

average level of real wages, and burden the Canadian welfare system.

Both these views are far too simplistic. Immigration can either benefit or harm the

receiving nation, depending on the number of immigrants; their education, skills,

and work ethic; and the rate at which they can be absorbed into the economy with-

out disruption. From a strictly economic perspective, nations seeking to maximize

net benefits from immigration should expand immigration until its marginal bene-

fits equal its marginal costs. The MB = MC conceptual framework explicitly recog-

nizes that there can be too few immigrants, just as there can be too many. Moreover,

the framework recognizes that from a strictly economic standpoint, not all immi-

grants are alike. The immigration of, say, a highly educated scientist has a different

effect on the economy than does the immigration of a long-term welfare recipient.

chapter fifteen • wage determination, discrimination, and immigration 411

● All else equal, immigration reduces wages,

increases domestic output, and increases busi-

ness income in the receiving nation; it has the

opposite effects in the sending nation.

● Assessing the effects of immigration is compli-

cated by such factors as unemployment, back-

flows and remittances, and fiscal impacts.

412 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

There have long been allega-

tions of discrimination against

women in the hiring process in

some occupations, but such dis-

crimination is usually difficult to

demonstrate. Economists Clau-

dia Goldin and Cecilia Rouse

spotted a unique opportunity for

testing such discrimination as it

relates to major symphony or-

chestras. In the past, orchestras

relied on their musical directors

to extend invitations to candi-

dates, audition them, and hand-

pick new members. Concerned

with the potential for hiring bias,

in the 1970s and 1980s orches-

tras altered the process in two

ways. First, orchestra members

were included as judges, and,

second, orchestras began open

competitions using blind audi-

tions with a physical screen

(usually a room divider) to con-

ceal the identity of the candi-

dates. (These blind auditions,

however, did not extend to the

final competition in most or-

chestras.) Did the change in pro-

cedures increase the probability

of women being hired?

To answer this question,

Goldin and Rouse studied the or-

chestral management files of au-

ditions for eight major orches-

tras. These records contained the

names of all candidates and iden-

tified those who had advanced to

the next round, including the ulti-

mate winners of the competition.

The researchers then looked for

women in the sample who had

competed in auditions both be-

fore and after the introduction of

the blind screening.

A strong suspicion existed of

bias against women in hiring

musicians for the nation’s finest

orchestras. These positions are

highly desirous, not only be-

cause they are prestigious but

also because they offer high pay

(often more than $75,000 annu-

ally). In 1970 only 5 percent of

the members of the top five

orchestras were women, and

many music directors publicly

suggested that women players,

in general, have less musical

talent.

The change to screens pro-

vided direct evidence of past

discrimination. The screens in-

creased by 50 percent the proba-

bility that a woman would be

advanced from the preliminary

rounds. The screens also greatly

increased the likelihood that a

woman would be selected in the

final round. Without the screens

about 10 percent of all hires

were women, but with the

screens about 35 percent were

women. Today, about 25 percent

of the membership of top sym-

phony orchestras are women.

The screens explain from 25 to

45 percent of the increases in

the proportion of women in the

orchestras studied.

Was the past discrimination

in hiring an example of statisti-

cal discrimination based on, say,

a presumption of greater turn-

over by women or more leaves

for medical (including maternity)

or other reasons? To answer that

question, Goldin and Rouse ex-

amined information on turnover

and leaves of orchestra mem-

bers between 1960 and 1996.

They found that neither differed

by gender, so leaves and turn-

over should not have influenced

hiring decisions.

Instead, the discrimination in

hiring seemed to reflect a taste

for discrimination by musical di-

rectors. Male musical directors

apparently had a positive dis-

crimination coefficient d. At the

fixed (union-determined) wage,

they simply preferred male mu-

sicians, at women’s expense.

Source: Claudia Goldin and Cecilia

Rouse, “Orchestrating Impartiality:

The Impact of ‘Blind’ Auditions on

Female Musicians,” American Eco-

nomic Review, September 2000, pp.

715–741.

ORCHESTRATING IMPARTIALITY

Have “blind” musical auditions, in which screens are

used to hide the identity of candidates, affected the

success of women in obtaining positions in major

symphony orchestras?

chapter summary

chapter fifteen • wage determination, discrimination, and immigration 413

1. The term “labour” encompasses all people

who work for pay. The wage rate is the price

paid per unit of time for labour. Labour earn-

ings comprise total pay and are found by

multiplying the number of hours worked by

the hourly wage rate. The nominal wage rate

is the amount of money received per unit of

time; the real wage rate is the purchasing

power of the nominal wage.

2. The long-run growth of real hourly earnings

—the average real wage—roughly matches

that of productivity, with both increasing

over the long run.

3. Global comparisons suggest that real wages

in Canada are relatively high, but not the

highest, internationally. High real wages in

the advanced industrial countries stem

largely from high labour productivity.

4. Specific wage rates depend on the structure

of the particular labour market. In a compet-

itive labour market, the equilibrium wage

rate and level of employment are deter-

mined at the intersection of the labour sup-

ply curve and labour demand curve. For the

individual firm, the market wage rate estab-

lishes a horizontal labour supply curve,

meaning that the wage rate equals the firm’s

constant marginal resource cost. The firm

hires workers to the point where its MRP

equals this MRC.

5. Under monopsony the marginal resource

cost curve lies above the resource supply

curve because the monopsonist must bid up

the wage rate to hire extra workers and must

pay that higher wage rate to all workers. The

monopsonist hires fewer workers than are

hired under competitive conditions, pays

less-than-competitive wage rates (has lower

labour costs), and thus obtains greater profit.

6. A union may raise competitive wage rates

by (a) increasing the derived demand for

labour, (b) restricting the supply of labour

through exclusive unionism, or (c) directly

enforcing an above-equilibrium wage rate

through inclusive unionism.

7. In many industries the labour market takes

the form of bilateral monopoly, in which a

strong union sells labour to a monopsonistic

employer. The wage-rate outcome of this

labour market model depends on union and

employer bargaining power.

8. On average, unionized workers realize wage

rates 10 to 15 percent higher than compara-

ble nonunion workers.

9. Economists disagree about the desirability

of the minimum wage as an antipoverty

mechanism. While it causes unemployment

for some low-income workers, it raises the

incomes of those who retain their jobs.

10. Wage differentials are largely explainable in

terms of (a) marginal revenue productivity of

various groups of workers; (b) noncompet-

ing groups arising from differences in the

capacities and education of different groups

of workers; (c) compensating wage differ-

ences, that is, wage differences that must be

paid to offset nonmonetary differences in

jobs; and (d) market imperfections in the

form of lack of job information, geographical

immobility, union and government restraints,

and discrimination.

11. The principal–agent problem arises when

workers provide less-than-expected effort.

Firms may combat this by monitoring work-

ers, by creating incentive pay schemes that

link worker compensation to effort, or by

paying efficiency wages.

12. Discrimination relating to the labour market

occurs when women or minorities having

the same abilities, education, training, and

experience as men or white workers receive

inferior treatment with respect to hiring,

occupational choice, education and training,

promotion, and wage rates. Forms of dis-

crimination include wage discrimination,

employment discrimination, occupational

discrimination, and human capital discrimi-

nation. Discrimination redistributes national

income and, by creating inefficiencies,

diminishes its size.

13. In the taste-for-discrimination model, some

white employers have a preference for dis-

crimination, measured by a discrimination

coefficient d. Prejudiced white employers

will hire visible-minority workers only if their

wages are at least d dollars below those of

whites. The model indicates that declines

in the discrimination coefficients of white

employers will increase the demand for

visible-minority workers, raising the visible-

minority wage rate and the ratio of visible-

minority wages to white wages. It also

terms and concepts

414 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

suggests that competition may eliminate dis-

crimination in the long run.

14. Statistical discrimination occurs when em-

ployers base employment decisions about

individuals on the average characteristics of

groups of workers. That practice can lead to

discrimination against individuals even in

the absence of prejudice.

15. The crowding model of occupational seg-

regation indicates how white males gain

higher earnings at the expense of women

and minorities who are confined to a limited

number of occupations. The model shows

that discrimination also causes a net loss of

domestic output.

16. Government antidiscrimination legislation

and policies involve direct governmental

intervention, including the requirement that

these firms enact employment equity pro-

grams to benefit women and certain minor-

ity groups.

17. Those who support employment equity

say it is needed to help compensate women

and minorities for decades of discrimi-

nation. Opponents say employment equity

causes economic inefficiency and reverse

discrimination.

18. Supply and demand analysis suggests that

the movement of migrants from a poor

country to a rich country (a) increases domes-

tic output in the rich country, (b) reduces the

average wage in the rich country, and (c) in-

creases business income in the rich country.

The opposite effects occur in the poor coun-

try, but the world as a whole realizes a larger

total output.

19. The outcomes of immigration predicted by

simple supply and demand analysis become

more complicated on consideration of (a) the

costs of moving, (b) the possibility of remit-

tances and backflows, (c) the level of unem-

ployment in each country, and (d) the fiscal

impact on the taxpayers of each country.

nominal wage, p. 376

real wage, p. 376

purely competitive labour

market, p. 379

monopsony, p. 382

exclusive unionism, p. 387

occupational licensing, p. 388

inclusive unionism, p. 388

bilateral monopoly, p. 390

minimum wage, p. 391

wage differentials, p. 393

marginal revenue

productivity, p. 393

noncompeting groups, p. 394

investment in human capital,

p. 395

compensating differences,

p. 395

incentive pay plan, p. 397

wage discrimination, p. 399

employment discrimination,

p. 400

occupational discrimination,

p. 400

human capital discrimination,

p. 400

taste-for-discrimination

model, p. 400

discrimination coefficient,

p. 401

statistical discrimination,

p. 403

occupational segregation,

p. 404

employment equity, p. 407

reverse discrimination, p. 408

legal immigrants, p. 408

illegal immigrants, p. 408

study questions

1. Explain why the general level of wages is high

in Canada and other industrially advanced

countries. What is the single most important

factor underlying the long-run increase in

average real-wage rates in Canada?

2. Why is a firm in a purely competitive labour

market a wage-taker? What would happen if

that firm decided to pay less than the going

market wage rate?

3.

KEY QUESTION Describe wage deter-

mination in a labour market in which work-

ers are unorganized and many firms actively

compete for the services of labour. Show

this situation graphically, using W

1

to indi-

cate the equilibrium wage rate and Q

1

to

show the number of workers hired by the

firms as a group. Show the labour supply

curve of the individual firm and compare it

with that of the total market. Why are there

differences? In the diagram representing the

firm, identify total revenue, total wage cost,

and revenue available for the payment of

nonlabour resources.

chapter fifteen • wage determination, discrimination, and immigration 415

4. KEY QUESTION Complete the fol-

lowing labour supply table for a firm hiring

labour competitively:

Total Marginal

Units of Wage labour cost resource

labour rate (wage bill) (labour) cost

0 $14 $______

1 14 ______

$______

2 14 ______

______

3 14 ______

______

4 14 ______

______

5 14 ______

______

6 14 ______

______

a. Show graphically the labour supply and

marginal resource (labour) cost curves

for this firm. Explain the relationship of

these curves to one another.

b. Plot the labour demand data of question

2 in Chapter 14 on the graph used in a.

What are the equilibrium wage rate and

level of employment? Explain.

5. Suppose the formerly competing firms in

question 3 form an employers’ association

that hires labour as a monopsonist would.

Describe verbally the effect on wage rates

and employment. Adjust the graph you drew

for question 3, showing the monopsonistic

wage rate and employment level as W

2

and Q

2

, respectively. Using this monopsony

model, explain why hospital administrators

sometimes complain about a shortage of

nurses. How might such a shortage be

corrected?

6.

KEY QUESTION Assume a firm is a

monopsonist that can hire its first worker for

$6 but must increase the wage rate by $3 to

attract each successive worker. Draw the

firm’s labour supply and marginal labour

cost curves and explain their relationships to

one another. On the same graph, plot the

labour demand data of question 2 in Chapter

14. What are the equilibrium wage rate and

level of employment? Why do these differ

from your answer to question 4?

7.

KEY QUESTION Assume a monop-

sonistic employer is paying a wage rate of

W

m

and hiring Q

m

workers, as indicated in

Figure 15-8. Now suppose an industrial

union is formed that forces the employer to

accept a wage rate of W

c

. Explain verbally

and graphically why in this instance the

higher wage rate will be accompanied by an

increase in the number of workers hired.

8.

Have you ever worked for the minimum wage?

If so, for how long? Would you favour increas-

ing the minimum wage by a dollar? by two dol-

lars? by five dollars? Explain your reasoning.

9. “Many of the lowest-paid people in society—

for example, short-order cooks—also have

relatively poor working conditions. Hence,

the notion of compensating wage differen-

tials is disproved.” Do you agree? Explain.

10. What is meant by investment in human cap-

ital? Use this concept to explain (a) wage dif-

ferentials, and (b) the long-run rise of real

wage rates in Canada.

11. What is the principal–agent problem? Have

you ever worked in a setting where this

problem arose? If so, do you think increased

monitoring would have eliminated the prob-

lem? Why don’t firms simply hire more

supervisors to eliminate shirking?

12.

KEY QUESTION The labour demand

and supply data in the table below relate to

a single occupation. Use them to answer the

questions that follow. Base your answers on

the taste-for-discrimination model.

Quantity Quantity of visible

of labour Visible minority labour

demanded, minority supplied

thousands wage rate (thousands)

24 $16 52

30 14 44

35 12 35

42 10 28

48 8 20

a. Plot the labour demand and supply

curves for visible minority workers in this

occupation.

b. What are the equilibrium visible minority

wage rate and quantity of visible minority

employment?

c. Suppose the white wage rate in this occu-

pation is $16. What is the visible minority-

to-white wage ratio?

d. Suppose a particular employer has a dis-

crimination coefficient d of $5 per hour.

416 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

Will that employer hire visible-minority

or white workers at the visible minority–

white wage ratio indicated in part (c)?

Explain.

e. Suppose employers as a group become

less prejudiced against visible minorities

and demand 14 more units of visible-

minority labour at each visible-minority

wage rate in the table. What are the new

equilibrium visible-minority wage rate

and level of visible-minority employment?

Does the visible minority–white wage

ratio rise or fall? Explain.

f. Suppose visible minorities as a group

increase their labour services in that

occupation, collectively offering 14 more

units of labour at each visible-minority

wage rate. Disregarding the changes

indicated in part (e), what are the new

equilibrium visible-minority wage rate

and level of visible-minority employ-

ment? Does the visible minority–white

wage ratio rise, or does it fall?

13. Males under the age of 25 must pay far

higher auto insurance premiums than fe-

males in this age group. How does this fact

relate to statistical discrimination? Statistical

discrimination implies that discrimination

can persist indefinitely, while the taste-for-

discrimination model suggests that competi-

tion might reduce discrimination in the long

run. Explain the difference.

14.

KEY QUESTION Use a demand and

supply model to explain the effect of occupa-

tional segregation or crowding on the relative

wage rates and earnings of men and women.

Who gains and who loses from the elimina-

tion of occupational segregation? Is there a

net gain or a net loss to society? Explain.

15. “Current employment equity programs are

based on the belief that to overcome dis-

crimination, we must practise discrimina-

tion. That perverse logic has created a sys-

tem that undermines the fundamental values

it was intended to protect.” Do you agree?

Why or why not?

16. Suppose Ann and Becky are applicants to

your university and that they have identi-

cal admission qualifications. Ann who is a

member of a visible minority, grew up in a

public housing development; Becky, who is

white, grew up in a wealthy suburb. You can

admit only one of the two. Which would you

admit and why? Now suppose that Ann is

white and Becky is a member of a visible

minority, all else being equal. Does that

change your selection? Why or why not?

17.

KEY QUESTION Use graphical analy-

sis to show the gains and losses resulting

from the migration of workers from a low-

income country to a high-income country.

Explain how your conclusions are affected

by (a) unemployment, (b) remittances to the

home country, (c) backflows of migrants to

their home country, and (d) the personal

characteristics of the migrants. If the mi-

grants are highly skilled workers, is there

any justification for the sending country to

levy a brain drain tax on emigrants?

18. Evaluate: “If Canada deported, say, 100,000

illegal immigrants, the number of unem-

ployed workers in Canada would decline by

100,000.”

19. If a person favours the free movement of

labour within Canada, is it then inconsis-

tent to also favour restrictions on the inter-

national movement of labour? Why or why

not?

20. (The Last Word) What two types of discrimi-

nation are represented by the discrimination

evidenced in this chapter’s The Last Word?

internet application question

1. Go to <espn.go.com/golfonline> and select

Tours, Rankings, and Money leaders. What

are the annual earnings to date of the top

10 male golfers on the PGA tour? What are

the earnings of the top 10 female golfers on

the LPGA tour? What are the general differ-

ences in earnings between the male and

female golfers? Can you explain them?

IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER

Y

Y

OU WILL LEARN:

OU WILL LEARN:

How the price of land

is determined.

•

How the interest rate

is determined.

•

What economic profit is, and

how profits, along with losses,

allocates resources among

alternative uses in an economy.

•

What the share of income

going to each of the factors

of production is in Canada.

Rent,

Interest,

and Profit

H

ow are land prices and rents estab-

lished and why do they differ? For

example, a hectare of land in the mid-

dle of Toronto or Vancouver can sell for more

than $50 million, while a hectare in Northern

Manitoba may fetch no more than $500.

What factors determine interest rates and

cause them to change? For example, why

were interest rates on Guaranteed Invest-

ment Certificate (GIC) 5.08 percent in Canada

in March 2000, but only 3.18 percent in

March 2001?

SIXTEEN

What are the sources of profits and losses? Why do profits change over time? For

example, why did Nortel Networks’ revenue jump by 26.5 percent in 1999, whereas

Corel Corporation’s revenue decreased and it lost money during that year?

In Chapter 15 we focused on wages and salaries, which account for 75 percent of

national income in Canada. In this chapter we examine the other resource pay-

ments—rent, interest, and profit—that comprise the remaining 25 percent of

national income. We begin by looking at rent.

To most people, “rent” means the money they must pay for the use of an apartment

or a room. To the business executive, “rent” is a payment made for the use of a fac-

tory building, machine, or warehouse facility. Such definitions of rent can be con-

fusing and ambiguous, however. Dormitory room rent, for example, may include

other payments as well: interest on money the university borrowed to finance the

dormitory, wages for custodial services, utility payments, and so on.

Economists use rent in a much narrower sense. Economic rent is the price paid

for the use of land and other natural resources that are completely fixed in total sup-

ply. As you will see, this fixed overall supply distinguishes rental payments from

wage, interest, and profit payments.

Let’s examine this idea and some of its implications through supply and demand

analysis. We first assume that all land is of the same grade or quality, meaning that

each arable (tillable) hectare of land is as productive as every other hectare. We

assume, too, that all land has a single use, for example, producing wheat. And we

suppose that land is rented or leased in a competitive market in which many pro-

ducers are demanding land and many landowners are offering land in the market.

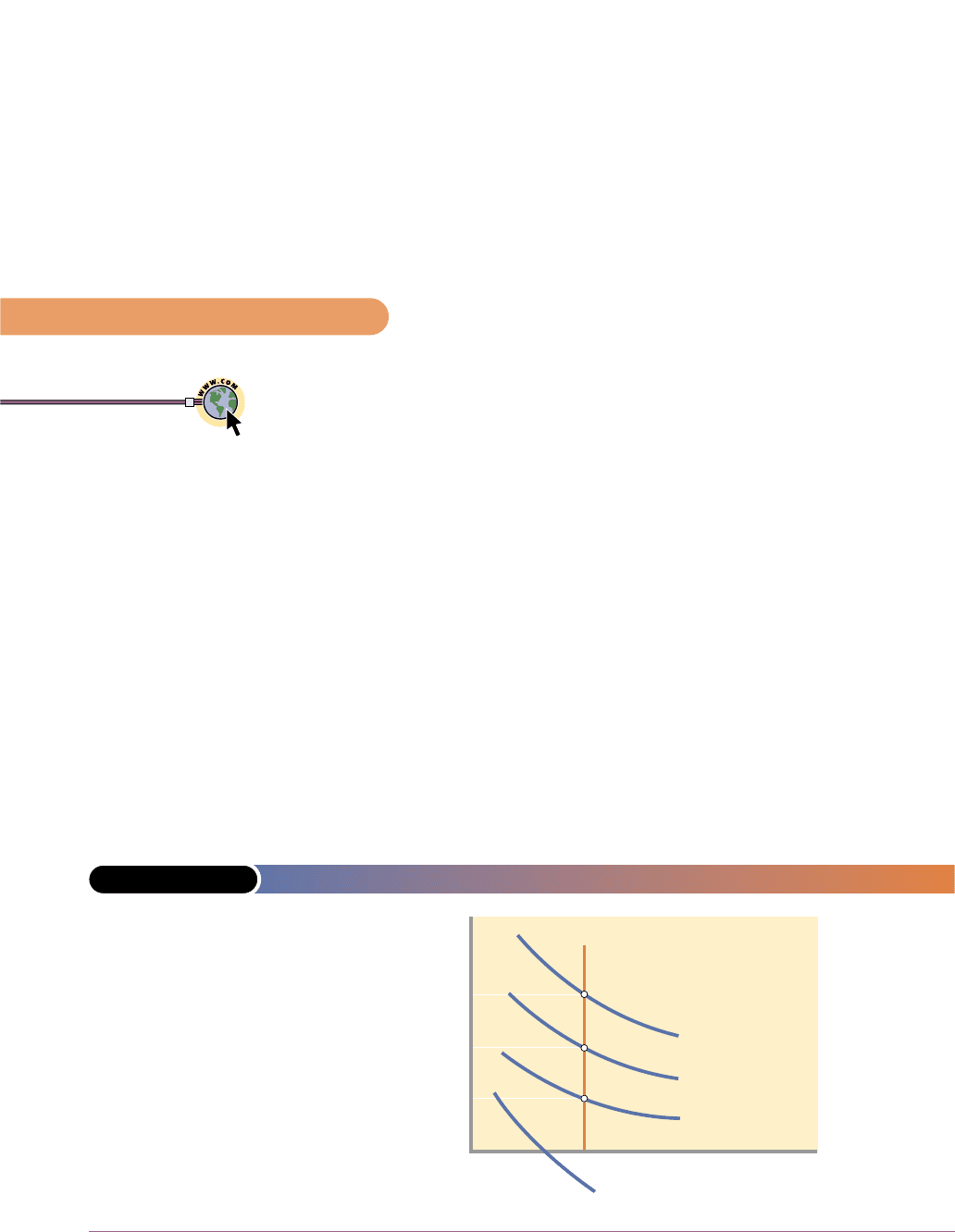

In Figure 16-1, curve S represents the supply of arable land available in the econ-

omy as a whole, and curve D

2

represents the demand of producers for use of that

land. As with all economic resources, this demand is derived from the demand for

the product being produced. The demand curve for land is downward sloping

because of diminishing returns and because, for producers as a group, product price

must be reduced to sell additional units of output.

418 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

Economic Rent

<www.theshortrun.com/

classroom/glossary/

micro/rent.html>

Economic rent

economic

rent

The price

paid for the use of

land and other

natural resources,

the supply of which

is fixed (perfectly

inelastic).

FIGURE 16-1 THE DETERMINATION OF LAND RENT

L

0

R

1

R

2

R

3

0

Hectares of land

Land rent (dollars)

ab

S

D

1

D

2

D

3

D

4

Because the supply S of land

(and other natural resources) is

perfectly inelastic, demand is

the sole active determinant of

land rent. An increase in

demand from D

2

to D

1

or a

decrease in demand from D

2

to

D

3

will cause a considerable

change in rent: from R

2

to R

1

in

the first instance and from R

2

to R

3

in the second. But the

amount of land supplied will

remain at L

0

. If demand is very

weak (D

4

) relative to supply,

land will be a free good,

commanding no rent.

Perfectly Inelastic Supply

The unique feature of our analysis is on the supply side. For all practical purposes

the supply of land is perfectly inelastic (in both the short run and long run), as

reflected in supply curve S. Land has no production cost; it is a “free and nonre-

producible gift of nature.” The economy has only so much land, and that’s that. Of

course, within limits any parcel of land can be made more usable by clearing,

drainage, and irrigation, but these are capital improvements and not changes in the

amount of land itself. Increases in the usability of land affect only a small fraction

of the total amount of land and do not change the basic fact that land and other nat-

ural resources are fixed in supply.

Changes in Demand

Because the supply of land is fixed, demand is the only active determinant of land

rent; supply is passive. And what determines the demand for land? The factors we

discussed in Chapter 14 do: the price of the product produced on the land, the pro-

ductivity of land (which depends in part on the quantity and quality of the

resources with which land is combined), and the prices of the other resources that

are combined with land.

If the demand for land in Figure 16-1 increased from D

2

to D

1

, land rent would rise

from R

2

to R

1

. If the demand for land declined from D

2

to D

3

, land rent would fall

from R

2

to R

3

. In either case, the amount of land supplied would remain the same at

quantity L

0

. Changes in economic rent have no effect on the amount of land available

since the supply of land cannot be augmented. If the demand for land were only D

4

,

land rent would be zero. Land would be a free good—a good for which demand is so

weak relative to supply that there is an excess supply of it even if the market price is

zero. In Figure 16-1, we show this excess supply as distance b – a at rent of zero. This

essentially was the situation in the free-land era of Canadian history.

The ideas underlying Figure 16-1 help answer one of our chapter-opening ques-

tions. Land prices and rents are so high along the Las Vegas strip, for example,

because the demand for that land is tremendous; it is capable of producing excep-

tionally high revenue from gambling, lodging, and entertainment. In contrast, the

demand for isolated land in the middle of the desert is highly limited because very

little revenue can be generated from its use. (It is an entirely different matter, of

course, if gold can be mined from the land, as is true of some isolated lands in

Nevada in the United States!)

Land Rent: A Surplus Payment

The perfectly inelastic supply of land must be contrasted with the relatively elastic

supply of capital, such as apartment buildings, machinery, and warehouses. In the

long run, capital is not fixed in total supply. A higher price gives entrepreneurs the

incentive to construct and offer larger quantities of property resources. Conversely,

a decline in price induces suppliers to allow existing facilities to depreciate and not

be replaced. The supply curves of these nonland resources are upward sloping,

meaning that the prices paid to such resources have an incentive function. A high

price provides an incentive to offer more of the resource, whereas a low price

prompts resource suppliers to offer less.

Not so with land. Rent serves no incentive function, because the total supply of

land is fixed. Whether rent is $10,000, $500, $1, or $0 per hectare, the same amount

of land is available to society for use in production, which is why economists

chapter sixteen • rent, interest, and profit 419

incentive

function

of price

The

inducement that an

increase in the price

of a commodity

gives to sellers to

make more of it

available (and

conversely for a

decrease in price).

consider rent a surplus payment not necessary to ensure that land is available to the

economy as a whole.

Application: A Single Tax on Land

If land is a gift of nature, costs nothing to produce, and would be available even

without rental payments, why should rent be paid to those who by historical acci-

dent, by inheritance, or by crook happen to be landowners? Socialists have long

argued that all land rents are unearned incomes. They argue that land should be

nationalized (owned by the state) so that any payments for its use can be used by

the government to further the well-being of the entire population rather than be

used by a landowning minority.

HENRY GEORGE’S PROPOSAL

In the United States, criticism of rental payments has taken the form of a single-tax

movement, which gained significant support in the late nineteenth century. Spear-

headed by Henry George’s provocative book Progress and Poverty (1879), support-

ers of this reform movement held that economic rent could be heavily taxed, or even

taxed away, without diminishing the available supply of land or, therefore, the pro-

ductive potential of the economy as a whole.

George observed that as the population grew and the geographic frontier closed,

landowners enjoyed larger and larger rents from their land holdings. That increase

in rents was the result of a growing demand for a resource whose supply was per-

fectly inelastic. Some landlords were receiving fabulously high incomes, not

through any productive effort, but solely through their owning advantageously

located land. George insisted that these increases in land rent belonged to the econ-

omy; he held that land rents should be heavily taxed and the revenue spent for pub-

lic uses. In seeking popular support for his ideas on land taxation, George proposed

that taxes on rental income be the only tax levied by government.

George’s case for taxing land was based not only on equity or fairness but also

on efficiency. That is, a tax on land is efficient because, unlike virtually every other

tax, it does not alter the use of the resource being taxed. A tax on wages reduces

after-tax wages and may weaken the incentive to work; an individual who decides

to work for a $10 before-tax wage may decide to retire when an income tax reduces

the wage to an after-tax $8. Similarly, a property tax on buildings lowers returns to

investors in such property and might cause some to look for other investments, but

no such reallocations of resources occur when land is taxed. The most profitable use

of land before it is taxed remains the most profitable use after it is taxed. Of course,

a landlord could withdraw land from production when a tax is imposed, but that

would mean no rental income at all. And, some rental income, no matter how small,

is better than none.

CRITICISMS

Very few advocates of a single tax on land remain. Critics of the idea have pointed

out the following:

● Current levels of government spending are such that a land tax alone would

not bring in enough revenue; it is unrealistic to consider it as a single tax.

● Most income payments consist of a mixture of such elements as interest, rent,

wages, and profits. Land is typically improved in some way, and economic

rent cannot be readily disentangled from payments for such improvements.

420 Part Three • Microeconomics of Resource Markets

single-tax

movement

A

movement spear-

headed by Henry

George in the late

nineteenth century

to make taxes on

rental income the

only tax levied by

government; few

advocates remain.