McKinney M. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

244

Baru

set in 1965–66. I chose that date because I think that it is at that moment that

the iron and steel industry broke up and sank. Quéquette blues is the story

of the last days of the working class. The protagonists rattle around and

bang up against the strict limits of their cultural universe, that of the factory,

which is a compartmentalized one and which lays on the shoulders of those

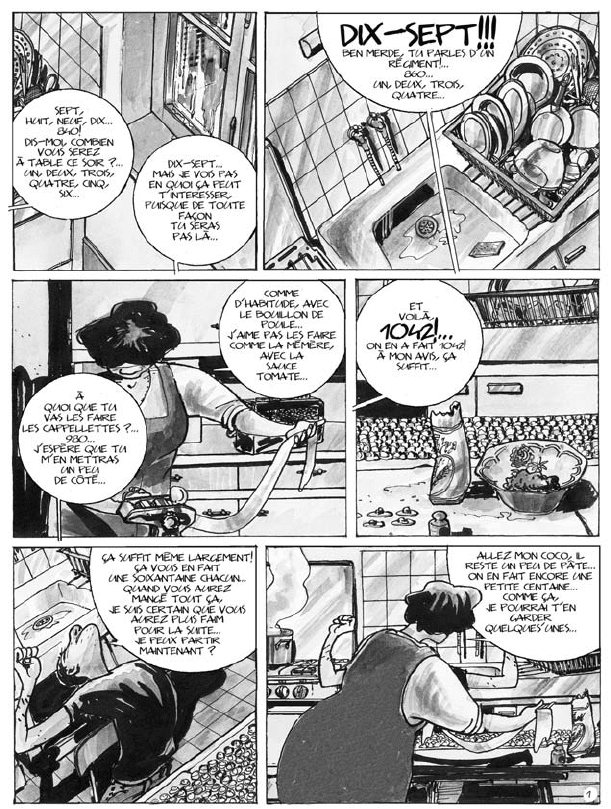

Fig. 1. A working-class manifesto in a bande dessinée: hervé and his mother talk while making

capelletti in the family kitchen. From Baru, Quéquette blues, plate 1; © Baru.

245

The Working Class and Comics

who maintain it the enormous weight of the determinisms that are necessary

to its prosperity. These young men will not escape from it. The last page of

the story tells this kind of inevitability of their destiny (figure 2): after having

worked itself into a frenzy, the group runs aground and goes to sleep next

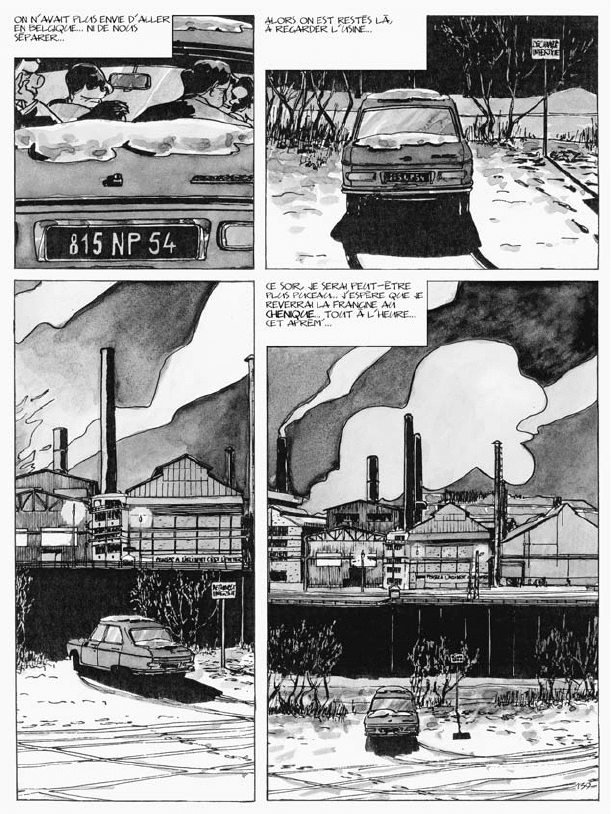

Fig. 2. the factory as the inevitable destiny of working-class young men celebrating new Year’s

eve by getting drunk and trying to get laid, in and around villerupt, lorraine. From Baru, Quéquette

blues, plate 139; © Baru.

246

Baru

to the factory that has dominated it throughout the entire length of the 140

pages of the story (141–42). In fact, the main character of Quéquette blues is

the factory, because it shuts away those who feed her and whom it nourishes.

This closing up is geographical, but also, especially, cultural.

I would now like to draw your attention to another frame of Quéquette

blues (22.1), because it was to determine the second fundamental axis of my

work (figure 3). It presents the brochette of those protagonists of the story

explicitly designated by their surnames. Half of them are Italians and French-

born Italians (the given names of the latter are French); the other half is com-

posed of children of the other wave of immigration, that of Arabs and Berbers

of North Africa, especially Algerians. I need to open a parenthesis here, re-

garding French immigration policy. The war of 1914–18 had left the country

bloodless and incapable of locally recruiting the working hands necessary for

the development of its heavy industry. So France intensively recruited foreign

workers with, for three decades, an almost exclusive reliance on European im-

migrant workers: Ukrainians, Spaniards, Portuguese, and especially Italians

and Poles. When this immigration began to dry up, the massive immigration

of Maghrebians

6

took over, especially after World War II. The problem with

all countries of immigration is the assimilation of foreign populations. You

may well know that the French often flatter themselves on having a French

model of integration. This model is based on the “droit du sol.”

7

It is inscribed

in the law that makes French any person who is born on French soil. It has a

corollary: ethnic nondiscrimination. In France, we have no Italo-French, for

example, such as you can say “Afro-Americans” in the United States. There are

only French people, because integration in France is a dissolving. To integrate

Fig. 3. Working-class protagonists from a variety of italian and Algerian ethnic backgrounds. From

Baru, Quéquette blues, plate 20, frame 1; © Baru.

247

The Working Class and Comics

oneself is to become transparent. Personally, I am the fruit of this model of

integration. My father did what I call the “dirty work.” He killed the Italian

in himself. I am telling you this because in France today, the integration of

Italians is the paradigm for the model of integration—except that it is a false-

hood. I have done some research on the subject, and I have found much ha-

tred and violence. There are Italians who were killed in France simply because

they were Italian. I have read official documents and newspaper articles full

of garbage and disdain for the “Macaronis.”

So I drew a parallel with the situation of the Maghrebians today. Why

did what happened with the Italians, the Poles, and the Spaniards not happen

with them? I think that the answer is very simple: work. The integration of the

first wave of immigrants in France took place simply because everyone had a

job, and work gave ipso facto a social reason-for-being. Maghrebian immigra-

tion was massive after World War II; it was not even affected by the Algerian

War. Having arrived last, the Maghrebians were confined to the most menial

tasks. And these were the positions that disappeared when the conservative

revolution of free-market economics unfurled at the end of the 1970s. Just

as massively as they had arrived, the Maghrebian immigrants were excluded

from prosperity and marginalized within French society. This non-assimilation

is a human disaster and a social disaster. It undermines French society, it en-

genders the tensions and fears that have caused the fascistic Far Right of Le

Pen to emerge and then grow fat.

8

This advent precipitated the solidification of something that had only

begun in my work and which, from then on, I was to build along two axes:

proclaiming the dignity of mine and proclaiming the dignity of those who

had replaced them, and whom French society refused to consider as theirs.

The realization that there was a natural ressemblance between the two waves

of immigration coincided with my book Vive la classe!, where I established

the fact that there was a rupture between the children of the “European” im-

migration and those of the North African immigration. The anecdote of this

book is a civic ritual that has now fallen into disuse, which still existed during

the 1960s: the army medical board [Conseil de révision]. It involved a quick

medical examination that declared whether the young men of eighteen were

fit for military service. This formality was followed by three or four days of

ritualized debauchery, which also functioned as a symbolic rite of passage to

adulthood. But for all the young men of immigrant heritage, this barbarous

ceremony held another meaning: from “Français de papier” [paper French-

men]

9

they were transformed into real Frenchmen, because henceforth they

were ready to “spill their blood for the Fatherland.” This is what encouraged

248

Baru

the tenacious survival of the tradition—which can be traced back to the

French Revolution—in regions where immigrants settled, whereas in the rest

of the country, especially in large cities, it did not survive World War II. It so

happens that the Maghrebians were excluded from this ritual when they had

not been born in France, which was still largely the case at the beginning of

the 1960s.

To deal with this rupture I took on the theme of the Algerian War

10

in

Vive la classe!, for the first time, but in a peripheral way (figure 4). This the-

matic has never left me, and it was to be present in all my future stories. I

either dealt with it head-on, as in Le chemin de l’Amérique [Road to America]

(Albin Michel, 1990; then Casterman, 1998),

11

or as a constitutive element of

the sociopolitical scenery in “Les années Spoutnik” [The Sputnik Years] (Cas-

terman, 1998–2003), but always with the same function: to situate the fracture

zone between the integrated population and the population excluded from

full citizenship.

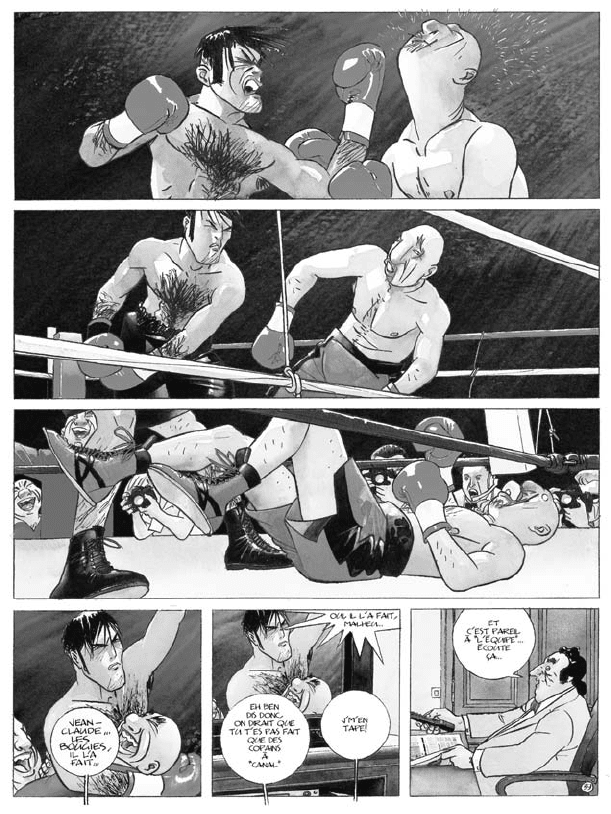

How did this evolution in my work come about, in concrete terms? I had

conceived of Quéquette blues as a manifesto-reference point, to clearly lay out

the viewpoint that was to be mine (i.e., the perspective of the immigrant, Ital-

ian working class). Therefore, I needed another book to establish the second

point of view in parallel with the first (i.e., the fracture between the European

and North African waves of immigration). This was Le chemin de l’Amérique.

Despite its anecdote (boxing), the story really deals with the Algerian War.

But I did not engage it directly, in the historical reality of its facts. I treated

it by staging the singular trajectory of a young Algerian boxer, who hopes to

escape from History as it unfolds but who will eventually be overtaken and

pulverized by it. I created this story at the end of the 1980s. At that time, even

though the Algerian War was well-studied by historians, it remained totally

absent—in reality, it was repressed—from the public spaces of French soci-

ety: the media, literature, cinema, and politics. For this reason, I chose to end

my story by evoking an event that was even more repressed, almost taboo, in

any case largely ignored or unknown: the bloody repression of a demonstra-

tion by Algerians in Paris on October 17, 1961 (please see chapter 7, above

[figures 7.6–7]). They were protesting against the discriminatory curfew that

had been put in place against them (Casterman, 40–45).

From that book on, I therefore developed my work according to this

symmetry: on the one hand, working-class culture—that is to say, the result

of fifty years of dissolving—and, on the other hand, the life of those who no

longer think of themselves as workers [ouvriers]—that is, the immigrants

of decolonization and their children. By emphasizing less what should dif-

249

The Working Class and Comics

ferentiate them (religion, cultural mores) and more what should unify them:

the fact that they belong, historically for one group (the working-class Euro-

pean immigrant community), or right now for the other one (the working-

class North African immigrant community), to the most dominated fringe

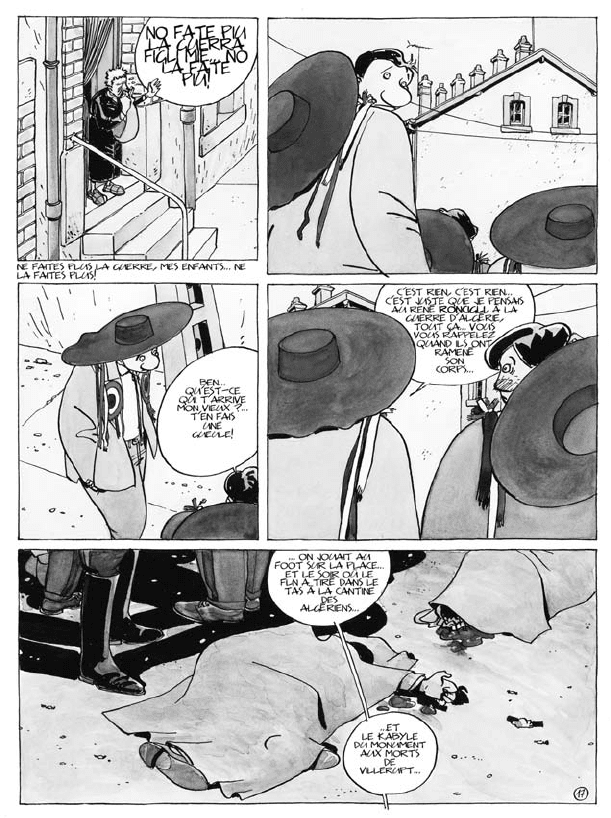

Fig. 4. A still grieving italian immigrant mother brings back sobering memories of victims of the Alge-

rian War, including her dead son rené and Algerian immigrants. From Baru, Vive la classe!, © Baru.

250

Baru

of French society. Immigrants are beings who are uprooted and therefore

destabilized and fragile. They are confined to spaces that are marginal, pe-

ripheral, in cultural and geographic terms. Due to this fact, they are at the

heart of the tumults that stir up society: delinquency, economic violence, rac-

ism, and xenophobia. My characters are always tightrope walkers who dance

along the line of social rupture that separates them from a settled France that

is all the more haunted by the fear of the other, of the foreigner, that it is close

to them, sociologically. They confront the most visible and the most tragic

consequence of the failure to assimilate Maghrebians: the growing power of

a racist and xenophobic Far Right organized around Jean-Marie Le Pen (he

has received 10 to 16 percent of the votes cast in presidential elections over

the last twenty years).

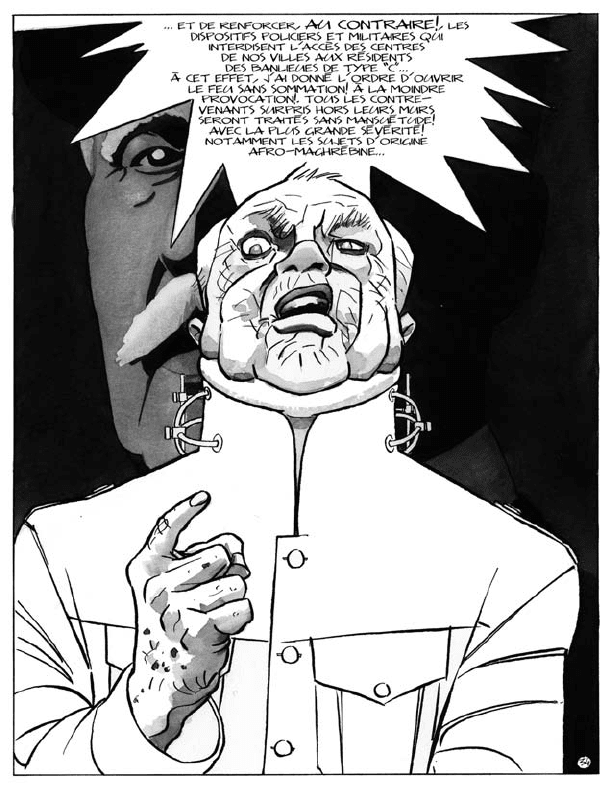

This civic catastrophe has become, in my work, a recurrent theme and

has furnished me with the bulk of my material for two books: L’autoroute

du soleil [The Highway of the Sun] (Casterman, 1995; figure 5) and Bonne

année [Happy New Year] (Casterman, 1998). I built Bonne année in a mirror

relationship to Quéquette blues—same anecdote: an outing by a group of

adolescents during the New Year’s holiday, except that in Bonne année the

party is lugubrious because they are walled into their neighborhood. Bonne

année is a futuristic, anticipative story, for which I imagined a world in which

Le Pen has acceded to power in France (figure 6). He has shut up the banlieues

[working-class neighborhoods]

12

inside walls similar to those of Berlin dur-

ing the cold war, to expell into them all the slag that the French heartland pro-

duces: economic rejects, drug addicts, and homosexuals. In Quéquette blues,

the subject was also shutting away, and there the youths of the factory bang

against the walls of the social determinisms that paralyze them.

In 2004 I published the first part of L’enragé [The Enraged] with Dupuis

(figure 7). The second volume was released in 2006. For this book, I built

a narrative structure around a couple of characters who still represent this

double composition of the dominated fringes of French society. The couple is

made up of Anton Witkowski, son of a European immigrant, and Mohamed

Meddadi, son of a Maghrebian immigrant. Anton and Mohamed are young

men of today and are, because of this, confined to the exclusionary space of

a suburban housing project [une cité de banlieue]. But this time I inverted

the roles. Both will try to escape from the social determinisms that imprison

them, but Mohamed will do it thanks to his studies, whereas Anton will do it

with the sole skill that he possesses: his capacity to endure the violence of the

milieu. He is the enraged one.

251

The Working Class and Comics

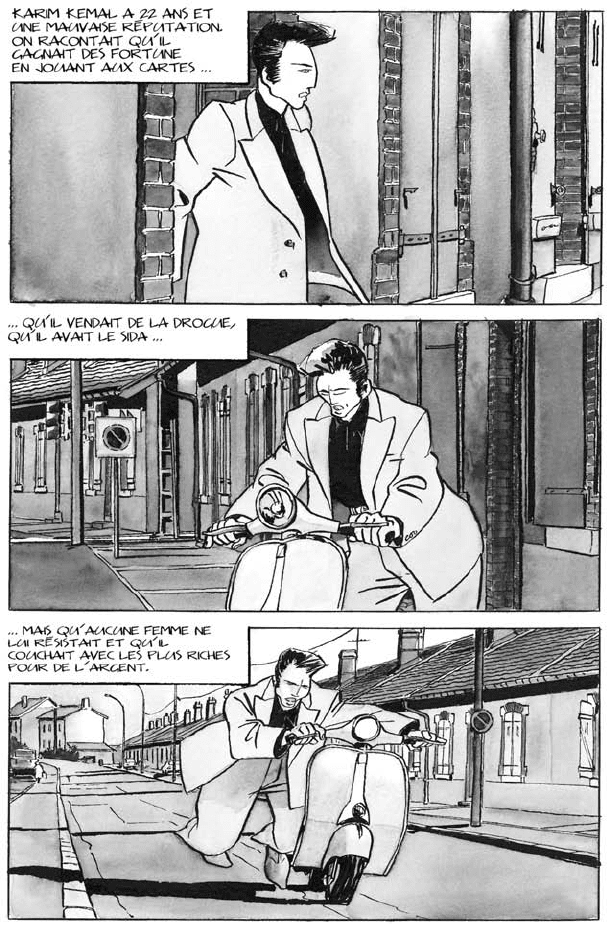

Fig. 5. A seductive Maghrebian-French protagonist with a bad reputation. From Baru, L’autoroute du

soleil, page 6; © Baru.

252

Baru

Fig. 6. the specter of fascism: a portrait of Maréchal Pétain looms behind Jean-Marie le Pen, a mon-

strous president of France in a dystopian future, as he confirms the relegation of north Africans and

others to the banlieues-as-ghettos. From Baru, Bonne année, plate 34; © Baru.

In 1998, I had successively made L’autoroute du soleil, Bonne année, and

Sur la route encore [On the Road Again] (Casterman, 1997), a book a bit apart

in my work, because it is much less sociologically marked. I will not dally

much over it, because it no doubt met a much more navel-gazing need for

253

The Working Class and Comics

Fig. 7. in a rage, Anton Witkowski, son of a european immigrant, demolishes his adversary as he

climbs the ladder to riches and boxing stardom. From Baru, L’enragé, vol. 1, plate 39; © Baru.

me: about to turn fifty, I was looking back over my itinerary and trying to

see what remained of some of the enthusiasms of my generation. The book

focuses predominantly on mores, rather than on social violence, even if the

latter comes out here and there. We cannot remake ourselves . . .