Odekon M. Encyclopedia of paleoclimatology and ancient environments

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

moraines and ice-flow features (e.g., drumlins), and it is more

abundantly constrained by radiocarbon dates. From its 30 ka

BP

position, Laurentide ice expanded to its late Wisconsinan maxi-

mum position in the northwest, south, and northeast about

23–24 ka

BP and in the southwest and far north about 20–21 ka BP

(Dyke et al., 2002). Hence, the general limit of glaciation

expanded by 500–1,000 km in 7,000–10,000 years, including

the inception and growth of the Innuitian and Cordilleran Ice

Sheets. Relatively little recession occurred prior to 14 ka

BP except

in deep water on the continental shelf off New England and

Atlantic Canada (Figure L20). Indeed, the southwestern margin

of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet continued to advance through the

Puget Lowland of Washington State until 14.5 ka

BP. Thus, the per-

iod of generally maximum ice cover in North America spanned

from about 22 to 14 ka

BP, which is broader than the interval of

the global sea-level minimum by several millennia on either side.

This fact suggests that North America is more susceptible to

glaciation than are the other large, periodically glaciated regions.

The recession of ice from the LGM is portrayed in

Figure L20 at 1,000-year intervals in radiocarbon years,

assembled from Dyke et al. (2003). The glacial geomorphology

of the continent is the fundamental constraint on any interpreta-

tion of North American deglaciation. Two specific patterns,

those of end moraines and other ice marginal features and those

of ice flow features, are of primary importance. These broad

patterns have been known for decades from large-scale compi-

lations such as the Glacial Map of Canada (Prest et al., 1968 ;

Dyke and Prest, 1987) and the Glacial Map of the United States

east of the Rockies (Flint et al., 1959). The fundamental

assumption in interpreting these patterns, in common with pre-

sent and previous efforts, is that where moraines or other ice

marginal features do not record specific ice margins, the mar-

gins tended to follow normal ice flow directions. This common

assumption accounts for the fundamentally similar patterns

seen in most reconstructions of Laurentide deglaciation over

the decades, namely recession back to the three major centers

of Keewatin, Quebec-Labrador, and Baffin Island.

The second major constraint in interpreting the history of

deglaciation is the set of relevant numerical age determinations.

New “exposure dating” studies have provided important tests of

models of terrain age in the “weathering zones” along the moun-

tainous eastern seaboard (e.g., Steig et al., 1998) and have re-

affirmed the late Wisconsinan age of final coalescence of the

Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets in Alberta (Jackson et al.,

1997). However, only radiocarbon age determinations are suffi-

ciently precise at this time to allow mapping of the deglaciation

sequence at centennial resolution. The radiocarbon database of

Dyke et al. (2003) provides direct and minimum-limiting dates

on ice recession as well as maximum-limiting dateson readvances,

including the advance to the late Wisconsinan glacial limit.

Most direct dates on ice marginal positions are from sites

where moraines or meltwater features have been followed into

shell-bearing marine deposits, such as commonly occur in ice-

contact deltas. Opportunities to date ice marginal features land-

ward of the limit of postglacial marine incursion directly are

exceedingly rare, being limited to those few localities where

ice readvanced across living or recently dead vegetation or

where the varve chronologies of proglacial lakes can be tied

into the radiocarbon time scale. The remaining age control is

entirely in the form of minimum-limiting dates on lake sedi-

ments, peat, wood, plant macrofossils, foraminifera, and mam-

mal bones. Reservoir corrections are applied to radiocarbon

dates on foraminifera as they are to marine mollusks.

In summary, ages of deglaciation are reasonably well estab-

lished in most coastal areas. Varve chronologies and dated

readvances provide control at key inland sites. Elsewhere,

minimum-limiting dates are valuable constraints. Recent

improvements in age control and more detailed mapping of

deglacial patterns have brought the North American deglacia-

tion sequence more evidently into correlation with the major

climatic events recognized in the North Atlantic region and in

the Greenland ice cores. Thus, the acceleration of retreat at

14 ka

BP corresponds to the sudden warming evident in the

Summit, Greenland ice core record. More significantly, the

Younger Dryas cooling now emerges as an important control

of ice marginal behavior of the North American ice sheets,

similar to that shown by the Scandinavian Ice Sheet, a result

commensurate with growing recognition of this event in North

American pollen records. Similarly, the prominent 8.2 cal ka

BP

cold event (7.5

14

CkaBP) is now firmly correlated with the

deglaciation of Hudson Bay and drainage of glacial lakes

Agassiz and Ojibway (Barber et al., 1999).

The world’s largest ice sheet complex lost < 10% of its area

prior to 14 ka

BP. It then retreated nearly linearly until 7 ka BP,

by which time only 10% of the area remained more glaciated

than it is today. This linear reduction of area, as currently

understood, was interrupted by two events: a reduced rate of

recession during the later half of the Younger Dryas, and an

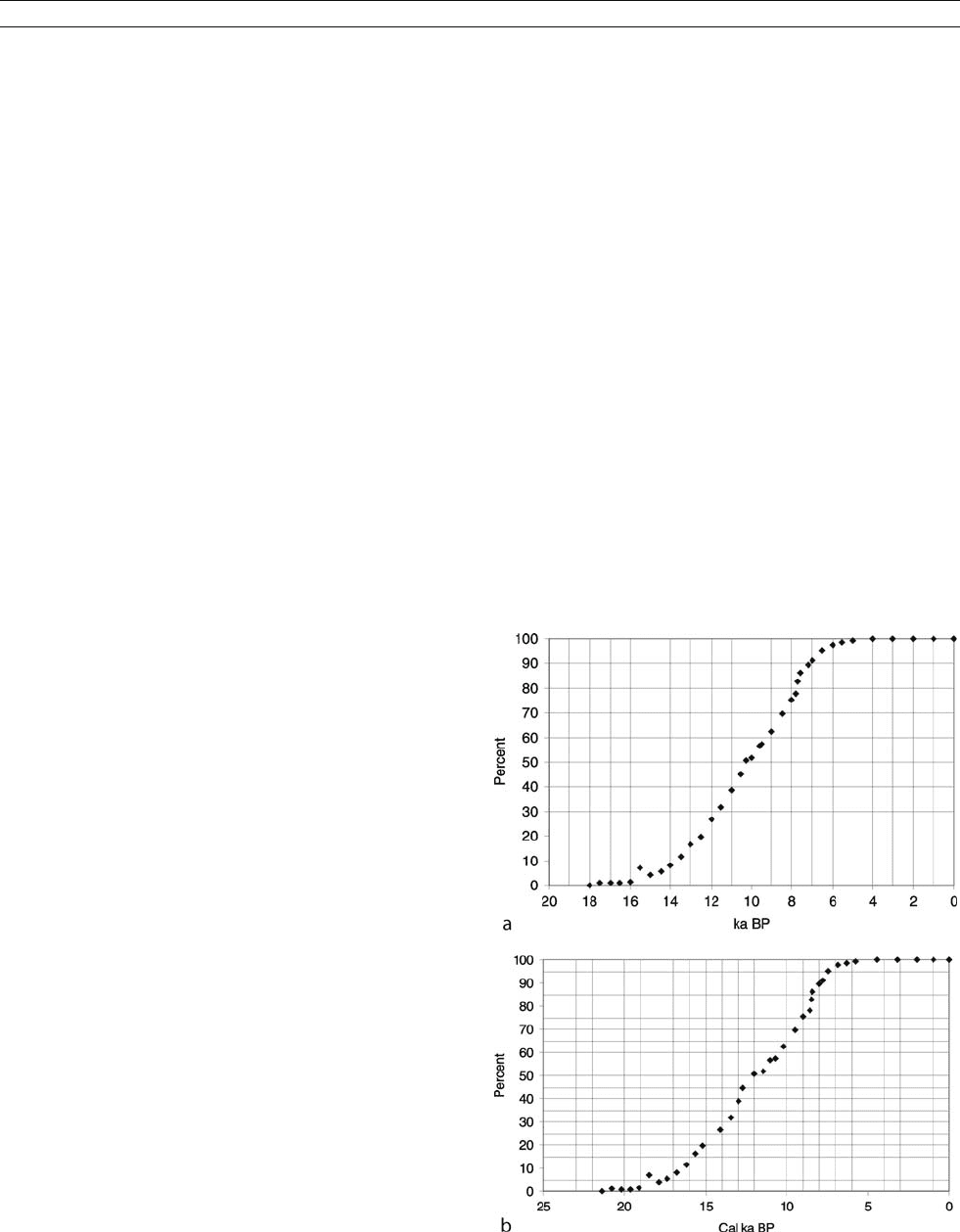

increased rate as ice cleared from Hudson Bay ( Figure L21).

These events are clearer when plotted on the calendar time

Figure L21 Percent area deglaciated in North America and Greenland,

plotted on radiocarbon (a) and calendar (b) time scales.

LAURENTIDE ICE SHEET 519

scale, because the radiocarbon time scale abbreviates the dura-

tion of the Younger Dryas (Figure L21b).

The deglacial chronology accords reasonably well with

the record of global sea-level rise (Fairbanks, 1989), which

features two meltwater pulses separated by reduced melting

during the Younger Dryas interval. During meltwater pulse IA

(13–11 ka

BP), the North American ice sheet complex decreased

from about 14.9 10

6

km

2

to 1 1.5 10

6

km

2

.Duringmeltwater

pulse IB (10.5–8.5 ka

BP), ice area decreased from 10.5 10

6

km

2

to 4.2 10

6

km

2

. These area reductions correspond approxi-

mately to volume losses of 10.8 10

6

km

3

(5,400 km

3

a

1

)and

11.7 10

6

km

3

(5,600 km

3

a

1

). These rates account for 40% of

meltwater pulse IA and 60% of meltwater pulse IB. The relatively

early demise of the Eurasian ice sheets accounts for their greater

contribution to meltwater pulse IA.

Arthur S. Dyke

Bibliography

Barber, D.C., Dyke, A.S., Hillaire-Marcel, C., Jennings, A.E., Andrews, J.T.,

Kerwin, M.W., Bilodeau, G., McNeely, R., Southon, J., Morehead, M.D.,

and Gagnon, J.-M., 1999. Forcing of the cold event of 8,200 years ago by

catastrophic drainage of Laurentian lakes. Nature, 400,344–348.

Bryson, R.A., Wendland, W.M., Ives, J.D., and Andrews, J.T., 1969.

Radiocarbon isochrones on the disintegration of the Laurentide Ice

Sheet. Arct. Alp. Res., 1,1–14.

Denton, G.H., and Hughes, T.J., 1981. The Last Great Ice Sheets.

New York: Wiley, 484pp.

Dyke, A.S., and Prest, V.K., 1987. The Late Wisconsinan and Holocene his-

tory of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Géographie physique et Quaternaire,

41,237–263.

Dyke, A.S., Andrews, J.T., Clark, P.U., England, J.H., Miller, G.H.,

Shaw, J., and Veillette, J.J., 2002. The Laurentide and Innuitian ice

sheets during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quaternary Sci. Rev ., 21,9–31.

Dyke, A.S., Moore, A., and Robertson, L., 2003. Deglaciation of North

America. Geological Survey of Canada Open File, 1574: Thirty-two

digital maps at 1:7 000 000 scale with accompanying digital chronolo-

gical database and one poster (two sheets) with full map series.

Fairbanks, R.G., 1989. A 17,000-year glacio-eustatic sea level record:

Influence of glacial melting rates on the Younger Dryas event and deep

ocean circulation. Nature, 342, 637–642.

Flint, R.F., Colton, R.B., Goldthwait, R.P., and Wilman, H.B., 1959. Glacial

Map of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. Geological

Society of America, 1:1,750,000.

Jackson, L.E. Jr., Phillips, F.M., Shimamura, K., and Little, E.C., 1997.

Cosmogenic

36

Cl dating of the Foothills erratics train, Alberta,

Canada. Geology, 25, 195–198.

Prest, V.K., 1969. Retreat of Wisconsin and Recent ice in North America.

Geological Survey of Canada Map, 1257A, scale 1:5 000 000.

Prest, V.K., Grant, D.R., and Rampton, V., 1968. Glacial Map of Canada.

Geological Survey of Canada Map, 1253A, scale 1:5 000 000.

Steig, E.J., Wolfe, A.P., and Miller, G.H., 1998. Wisconsinan refugia and

the glacial history of eastern Baffin Island, Arctic Canada: Coupled

evidence from cosmogenic isotopes and lake sediments. Geology, 26,

835–838.

Cross-references

Cordilleran Ice Sheet

Glacial Geomorphology

Glaciations, Quaternary

Last Glacial Maximum

Moraines

Radiocarbon Dating

Sea Level Change, Quaternary

The 8200-Year BP Event

Tills & Tillites

Wisconsinan (Weichselian, Würm) Glaciation

Younger Dryas

LITTLE ICE AGE

General description

The period known as the “Little Ice Age” spans roughly the

sixteenth through the mid-nineteenth centuries. During this

time, temperatures over much of Europe were frequently unu-

sually cold, Alpine glaciers advanced, and European rivers

froze much more often than during medieval times or during

the past century and a half. Cold climates also prevailed over

several other areas, especially those adjacent to the North

Atlantic. The combination of cold conditions over both Europe

and eastern North America, the two areas with the greatest

amount of western record-keeping, led many to consider the

period as one of global cooling, resulting in the label “Little

Ice Age.”

Modern science has shown, however, that there is consider-

able regional variation in the extent of the cooling, with some

areas even warming during this period. It now appears that the

Northern Hemisphere as a whole cooled only moderately (Briffa

et al., 1998; Jones et al., 1998;Mannetal.,1999;Crowley,

2000), by several tenths of a degree. However, not enough

data exists to establish a reliable estimate for the Southern

Hemisphere as a whole. Furthermore, even in the areas that

cooled, there is a great deal of variability in the timing of the

cooling. This latter fact has led to a proliferation of time-periods

that are called the Little Ice Age, with some extending it to the

fourteenth century (Fagan, 2000).

Despite the inhomogeneous cooling during the Little Ice

Age, it remains important as it is the most reliably documented,

relatively large climate anomaly during the last millennium

(prior to the industrial revolution). Understanding the Little

Ice Age is therefore an important test of our comprehension

of natural climate variability.

Evidence

Based on early thermometer measurements, documentary evi-

dence, and proxies for past temperatures (such as tree rings

and glacier extents), it is believed that annually averaged

European temperatures were roughly 1–1.5

C colder during

the Little Ice Age relative to preceding or subsequent periods

(Pfister, 1995; Shindell et al., 2001). However, many winters

appear to have been much colder (e.g., see Fagan, 2000). Dutch

masterpieces from that time by Brueghel, van der Neer and

others show people skating on canals and rivers that almost

never freeze today. Ice was so prevalent in northern seas that

Inuit fisherman were seen as far south as Scotland. Glaciers

advanced in the Alps, Scandinavia and Iceland, destroying out-

lying farms and threatening to crush whole villages. Snow lay

on the ground in Britain and the Netherlands an average of

20–30 days during the winter between 1680 and 1730, as

opposed to an average of 2–10 days every winter during the

twentieth century (Fagan, 2000). In North America, native

tribes banded together to form the League of the Iroquois in

the face of declining food supplies and other natural hardships

during those cold years. During the American Revolutionary

War, British soldiers were able to drag massive cannons across

a frozen New York Harbor.

It is often claimed that the Viking settlements in Greenland

and the New World were wiped out by the severe drop in

520 LITTLE ICE AGE

temperatures. Local climate conditions likely changed in these

locations, but not necessarily in concert with those elsewhere.

Additionally, it seems that the cutting off of trade routes back

to Europe played a primary role in the settlements ’ demise.

An increase in North Atlantic sea ice due to climatic changes

may therefore have been more important than altered local con-

ditions. Weather in Iceland illustrates the complexity of relating

climate change to habitability. Iceland was locked in by sea ice

for several months during most years of the Little Ice Age, but

seldom after 1880. Barley was grown effectively in Iceland

from the ninth century through the twelfth, after which this

crop failed until the warming of the late 1900s. While con-

ditions were certainly harsher in Iceland during the Little

Ice Age, the cold weather there may have actually begun much

earlier.

Cause s of cooling

I t h a s l o n g b e en s p e cu la t e d th at t h e d r o p i n t em p er at u r e s w a s

due to a dimmer Sun. G al ileo ’ s development of t he teles c ope

for a stronom y in the ea r ly 1 600s al lowed early observers t o

char t t he behav i or of the S un. T hey r eg ularly noticed dark

spots, which c ycled over a period of ab o ut 11 years, a s t hey

do today. After 1645, the sp ots largel y vanished. They reap-

pear ed aro und 17 15, an d t he sunspot cy cl e has bee n present

ever sin ce. The in t erven i ng year s a re now kno wn as the

Maunder M inimum, t he most prolong ed and dramatic of sev-

eral decadal timescal e red uct ions in solar ir radiance during

the l ast mille nnium. This period c oinci des with the c oldest

European temperatures . M odern sat e llite meas urements have

confirmed th e ear l y a ssumption t hat t he number of sun spots

is rel a ted to the total brightn ess o f the Sun, though the exact

rel atio nship is not yet well quan ti fied . The Maunder Mini-

mum period, with almost no sunspots reco rded by European

a s tr o n o m er s , r ep r e s en t s t h e ex t r e m e l o w o f a m u lt i - ce n t u r y

period that ap pears to have b ee n marked by generally lo wer

solar output. E vidence f rom c osmog en i c i sotopes ( ato m i c i so-

topes p roduced only by c osmic rays wh ose abili ty to reach

the E ar th dep e nds on the sun) obtai ned from i ce co res

match es t he general pat tern of sun spot var i ab il ity during past

centuries , incl udin g the Littl e Ice A ge (Stuiver and Braziu nas ,

1989). The reduction i n solar output du ring t he Maunder

Minimu m i s es timated at about one-quarter of one percent

(Lean et al., 1995). Th ough this is a ver y smal l ch an ge, t he

output of the Sun is so large that this ca n stil l have a sizea ble

impact. H owev er, i t i s not enough to plung e t he whole E ar th

into much co lder conditions, a nd ev en to acc ount for the

modern view of the L ittl e Ice Age as a regional ph en om en o n

requires some amplific ation.

The other maj or fact or in the cooling durin g this period

was a n i ncrease i n volca nic e rup ti on f requency a nd size (Free

and R obock , 1999; C r o w l ey, 200 0). Limited historica l infor-

mation i s su pplem en ted by t he signatu re volcanic as h lay e rs

pres erv ed in ice co res. Eruptions injecte d a larger n umber of

aer osol particles in to the at mospher e during the seven teenth

cen t ury t han during t he period immediat ely f ollowing the Lit-

tle Ice A ge or during the Mediev al War m Period, which pre-

ceded it. These par ticl e s r eflect solar r adiat ion, a nd it is

esti mat e d that the additional er uptions of the sev en teen th ce n-

tury would h av e reduced the r ad ia tion reac hing t he Earth by

an amount co mpar able to the r ed uced solar output at that time

( Cr o w l ey, 2000). The global a verage surfac e te mperat ure

res ponse is proporti onal to this en ergy c hange; theref ore,

volcan ism co uld have pla yed a r ole i n th e glob al or hemi-

spheric mean r esponse al t hough t he global effects la sted only

1 – 3 year s. A combination o f solar and volcan ic influ en ces

seem s the most likely ex pla nation f or the hemispheric -sca le

cooling of the Litt le Ice Age.

Regiona l climate change

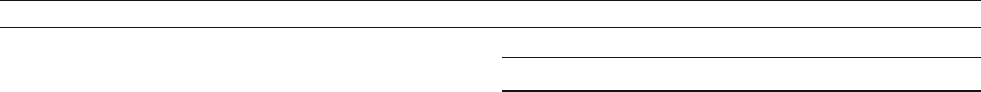

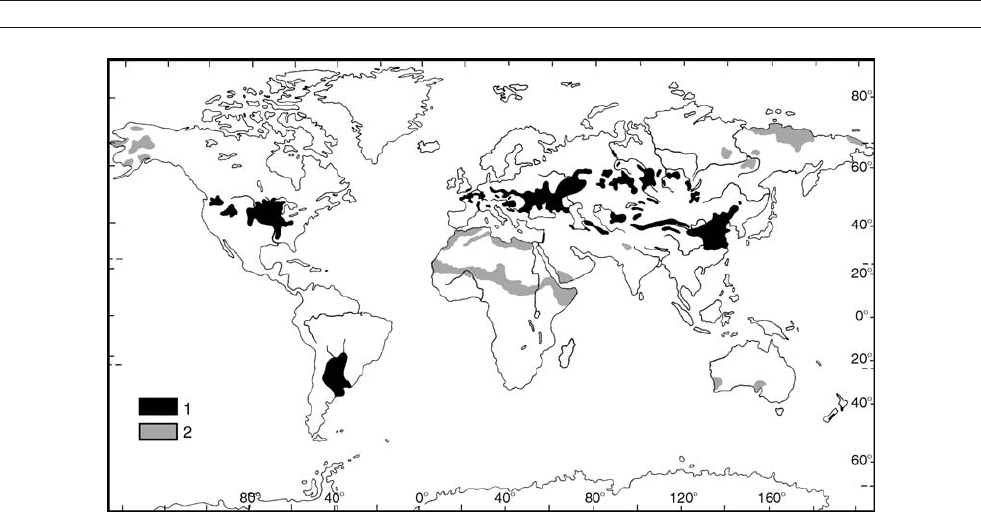

Studies have shown that changes in stratospheric ozone in

response to solar variations amplify the climate impact of those

irradiance variations (Haigh, 1996; Shindell et al., 1999; Shin-

dell et al., 2001). Incorporating those ozone changes, the most

recent climate model simulations have found that the reduced

brightness of the Sun during the Maunder Minimum causes

global annual average surface temperature changes of only a

few tenths of a degree, in line with the small hemispheric aver-

age cooling seen in the proxy data. However, regional winter-

time cooling over Europe and North America is 5–10 times

larger due to a shift in atmospheric winds (Shindell et al.,

2001). Both the climate model and proxy data show that sur-

face temperature changes associated with solar output varia-

tions exhibit alternating warm oceans and cold continents at

mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (Figure L22). These

seem to occur primarily through a slowdown in the speed of

westerly winds at the Earth’s surface associated with the North

Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Greater heating by the Sun in the

tropics relative to high latitudes causes an equator-to-pole

flow of air, which is turned towards the east by the Earth’s rota-

tion. A reduction in the amount of sunlight reaching the planet

leads to a weaker equator-to-pole heating difference, and there-

fore slower winds. Ozone changes in the stratosphere amplify

this effect.

Impacts on surface temperatures are particularly large in

winter. Because the oceans are relatively warm during the win-

ter due to their large heat storage, the diminished flow creates a

cold-land / warm-ocean pattern (as shown in Figure L22 )by

reducing the transport of warm oceanic air to the continents,

and vice versa. Changes in this wind flow have only a small

impact on global temperatures as the warm and cold regions

average out. However, they have a large regional effect and

increase the frequency of extreme events, such that a reduction

in winds would lead to many more extremely cold days over

Europe and eastern North America (which may stand out in

the historical record). The shift in circulation thus appears to

be the solution to the apparent paradox of extreme cold with

only a marginally dimmer sun. Ocean circulation may have

also responded to solar irradiance fluctuations. Volcanic erup-

tions are known to induce a positive bias in the NAO during

the winter following the eruption, but this is opposite to the

pattern seen during the Little Ice Age. Their long-term impact

is likely to be relatively minor, as the particles injected into

the upper atmosphere typically remain there in sufficient num-

bers to affect climate for only a year or two.

Though early records of wind flow are extremely limited,

historical data associates the European seventeenth century

winter cooling with enhanced northeasterly advection of con-

tinental air, consistent with an anomalous negative phase of

the NAO (Slonosky et al., 2001). Reconstructions of the

strength of the NAO from instrumental and proxy data suggest

that there may have been a long-term weakening during the Lit-

tle Ice Age (Luterbacher et al., 1999). Ocean sediments show a

decreased sea surface temperature of 1–2

C in the Sargasso

Sea during the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, and warmer

LITTLE ICE AGE 521

Atlantic temperatures north of 44

N latitude, extending to the

area off Newfoundland (Kiegwin and Pickart, 1999), consistent

with a reduced NAO, but not with uniform basin-wide cooling.

Drew T. Shindell

Bibliography

Briffa, K.R., Jones, P.D., Schweingruber, F.H., and Osborn, T.J., 1998.

Influence of volcanic eruptions on Northern Hemisphere summer tem-

perature over the past 600 years. Nature, 393, 350–354.

Crowley, T.J., 2000. Causes of climate change over the past 1000 years.

Science, 289, 270–277.

Fagan, B., 2000. The Little Ice Age, New York: Basic Books, 272 pp.

Free, M., and Robock, A., 1999. Global warming in the context of the Lit-

tle Ice Age. J. Geophys. Res., 104, 19057–19070.

Haigh, J.D., 1996. The impact of solar variability on climate. Science, 272,

981–984.

Jones, P., et al., 1998. High-resolution palaeoclimatic records for the last

millennium: interpretation, integration and comparison with General

Circulation Model control-run temperatures. Holocene, 8, 455–471.

Kiegwin, L.D., and Pickart, R.S., 1999. Slope water current over the Laur-

entian Fan on Interannual to Millennial Time Scales. Science, 286,

520–523.

Lean, J., Beer, J., and Bradley, R., 1995. Reconstruction of solar irradiance

since 1610: Implications for climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett., 22,

3195–3198.

Luterbacher, J., Schmutz, C., Gyalistras, D., Xoplaki, E. and Wanner, H.,

1999. Reconstruction of monthly NAO and EU indices back to AD

1675. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 2745–2748.

Mann, M.E., Bradley, R.S., and Hughes, M.K., 1999. Northern hemisphere

temperatures during the past millennium: Inferences, uncertainties, and

limitations. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 759–762.

Pfister, C., 1995. Monthly temperature and precipitation in central Europe

1525–1979: Quantifying documentary evidence on weather and its

effects. In Bradley,R.S., and Jones, P.D. (eds.), Climate Since A.D.

1500. London: Routledge, pp. 118–142.

Shindell, D.T., Rind, D., Balachandran, N.K., Lean, J., and Lonergan, P.,

1999. Solar cycle variability, ozone, and climate. Science, 284, 305–308.

Shindell, D.T., Schmidt, G.A., Mann, M.E., Rind, D., and Waple, A., 2001.

Solar forcing of regional climate change during the Maunder Minimum.

Science

, 294, 2149–2152.

Slonosky, V.C., Jones, P.D., and Davies, T.D., 2001.Instrumental pressure

observations and atmospheric circulation from the 17th and 18th centu-

ries: London and Paris. Int. J. Climatol., 21, 285–298.

Stuiver, M., and Braziunas, T.F., 1989. Atmospheric C-14 and century-

scale solar oscillations. Nature, 338, 405–408.

Cross-references

Climate Variability and Change, last 1,000 years

Cosmogenic Radionuclides

Maunder Minimum

Medieval Warm Period

North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) Records

Sun-Climate Connections

Volcanic Eruptions and Climate Change

LOESS DEPOSITS

Definition

Loess can be defined simply as a terrestrial clastic sediment,

composed predominantly of silt-sized particles, which is

formed essentially by the accumulation of wind-blown dust.

Initially, von Leonhard (1823–1824) used the word “Loeb”

for friable silty deposits near Heidelberg, based on the word

“Loesch” for loose soil, which was the term used by the local

people of the Rhine Valley. Lyell (1834–1845) brought the

Figure L22 Annual average surface temperature change (C) due to solar irradiance change between the Maunder Minimum (late seventeenth

century) and a century later, when solar output had returned to relatively large values, in the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies climate

model (top) and in the historical temperature reconstructions (bottom).

522 LOESS DEPOSITS

term into widespread usage and was responsible for stimulating

interest in similar deposits. However, the eolian origin of loess

did not become widely accepted until the publications of

von Richthofen (1870–1885). Several genetic and descriptive

definitions of loess have been discussed since that time.

Although the sub-aerial wind-fall origin, as well as silt-sized

quartz particles domination, are the leading criteria of loess sedi-

ments, other additional definitive features (e.g., loose, unstrati-

fied, porous, calcareous, pale yellow, occurring in mantle form,

etc.) are advocated by many scientists. In a historical perspective,

the definition’s use was controlled by its application.

Composition and features

Loess is relatively well-sorted clastic sediment that is homoge-

neous, porous and slightly altered. Typical loess (so called “pri-

mary loess”) usually has a yellow or pale yellow color. Coarse

silt particles (10–50 mm in diameter) make 40–70% of typical

loess by weight. This size fraction of particles is characteristic

of eolian dust deposits and commonly is called the “basic,”

“loess” or “loessic” fraction. The percentage of clay and sand

content in loess is subordinate in importance (5–20%). Beside

the prevailing quartz grains (40–80%), it may contain feldspar,

calcite and dolomite. Quartz in loess occurs as irregular, suban-

gular and angular grains with characteristic surfaces resulting

from mechanical fragmentation. Among clay minerals, either

illite or montmorillonite dominates are present, although kaoli-

nite, vermiculite and chlorite may also be present in smaller

amounts. Carbonate content is variable (ranging from 1 to

20%), depending on environmental conditions. Mineral grains

are slightly cemented and partly aggregated mostly by carbonate.

Primary carbonates usually are dolomite particles but secondary

carbonates consist of calcite coatings on silt grains, fillings in

interstices and vertical tubes left from the decay of grass roots.

The void ratio is usually extremely high (45–55%) in loess,

and the average diameter of aggregates is 10–15 mm. Loess is

permeable to water and easily collapses when saturated with

water. The compression strength of loess is about 1.5 kg dm

2

.

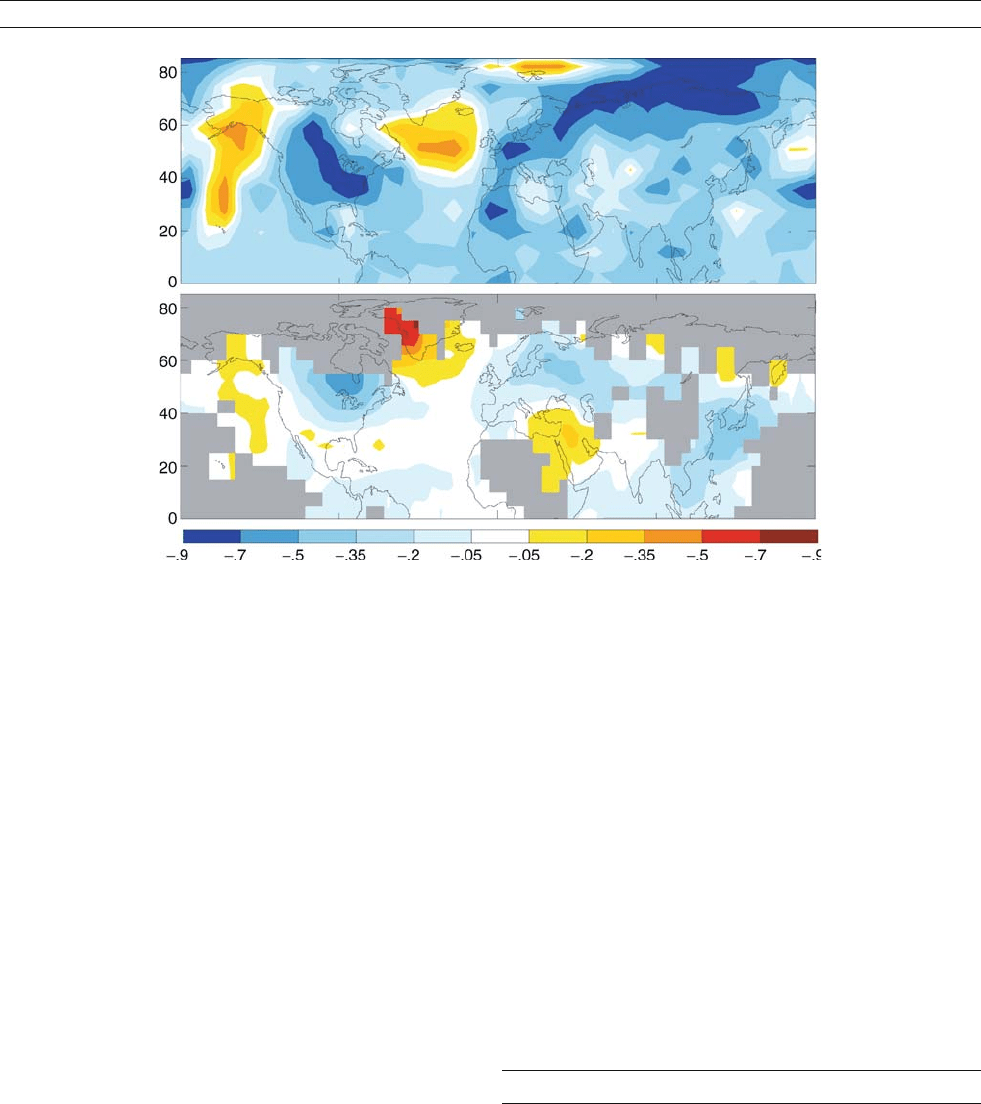

The collapsibility leads to eventual problems for engineering

activities in loess areas. Moreover, loess is easily eroded by sur-

face water and liable to underground piping, though under

dry conditions even steep loess walls are stable (Figure L23).

Remnants of terrestrial materials, mostly of cryophile fauna

and flora, are typical in the loess horizons. Individual loess

horizons are usually unstratified, but loess sequences often contain

intercalated loam or sand beds (Liu et al., 1985; Pécsi, 1990).

Although the above features are characteristic of typical

loess, non-typical loess or “loess-like sediments” of similar

properties and genesis is widespread. In many loess sequences

there is a continuum of modified loess, which ranges from

weakly developed leached layers to intensely weathered paleo-

sols and pedocomplexes. When altered by active soil forma-

tion, loess becomes more clay-like, hardens and can be either

leached of primary carbonates or enriched by secondary carbo-

nates. When redeposited by rainwater runoff, snowmelt and

other processes, loess becomes slightly stratified. The terms

“secondary loess,”“altered loess,”“degraded loess,”“redepos-

ited loess,”“loess derivates” and “reworked loess” have been

used to describe such varieties of loess.

Origin

The origin of loess has a long history of controversy. Since von

Richthofen suggested the “subaerial” theory of loess formation

in 1870, the eolian origin of loess has been the most popular

and best-documented. Succeeding investigations refined the

process of eolian dust sedimentation and loess feature forma-

tion. The contributions of Tutkovskii, Obruchev and Kriger

(Russia), von Richthofen and Grahmann (Germany), Liu

(China), Fink (Austria), Kukla (Czechoslovakia) and Pécsi

(Hungary), as well as Pye and Péwé (USA), are well known

(Smalley, 1975; Liu et al., 1985; Pécsi, 1990; Pye, 1995).

Three conditions are required for loess deposition: (a) a

large supply of suitable dust-sized particles that is sustained,

at least episodically, over a period of tens to hundreds of thou-

sands of years; (b) adequate wind energy to transport the dust,

and (c) the existence of suitable dust traps downwind of the

dust source area.

Although in situ weathering products may be directly

deflated, in most instances at least one intermediate stage

of alluvial or glaciofluvial transport and deposition is involved

before it is picked up by wind and deposited as loess. Extensive

loess deposits appear to be a Quaternary phenomenon and show

a clear spatial relationship with areas of Pleistocene continental

glaciation. Such deposits have been referred to as “glacial” or

“periglacial” loess. The constituent silt particles were formed

largely by sub-glacial grinding and subsequently deflated from

glaciofluvial outwash deposits. Loess cover is particularly thick

(almost up to 30 m) near valleys that served as meltwater draina-

geways, but thins and becomes finer away from valleys. Depos-

its of loess also occur on the semi-arid margins of some deserts

(“peridesert loess”). In this case, significant amounts of quartz

silt are probably produced by eolian abrasion and weathering

processes in deserts or in adjacent mountain ranges before being

deflated and deposited as loess. As opposed to the “cold

loesses” of periglacial zones, the peridesert loesses are called

“warm loesses” (Smalley, 1975, Liu, 1985, Pye, 1995).

The magnitude of the dust flux and pattern of dispersion from a

potential source are strongly influenced by the nature of the pre-

vailing regional winds. Local wind systems, such as valley winds,

can be important in forming proximal dust deposits, but longer-

range transport and formation of distal deposits requires the invol-

vement of regional-scale wind systems. Dry deposition is

enhanced wherever there is a reduction in wind speed or an

increase in surface roughness. However, if dust passesover a water

body, moist ground or a vegetated surface, the particles may be

trapped. Subsequently, on impact of rainwater runoff, snowmelt

or other processes on the slope, grains may be moved further away

Figure L23 Peoria and Roxana loess horizons of the Wisconsinian time

at Crowley’s Ridge, Arkansas.

LOESS DEPOSITS 523

until they are stabilized by vegetation. Soil and related weathering

processes are a syn- or post-depositional alteration of the primary

deposit, and to some geologists are early stage diagenesis.

An alternative hypothesis (“soil-eluvial,”“in situ” or “back-

swamp-loessification”) of loess formation was suggested by

Berg in Russia in 1916, and then advocated by Russel and Fisk

in the USA in 1944 (Smalley, 1975; Follmer, 1996). This

hypothesis excludes the eolian factor and assumes most of

loess sediments have a fluvial origin. According to this idea,

any fine-grained deposits may be converted into typical loess

as a result of weathering and soil forming processes. The in situ

theory has not been well-documented or widely accepted since

that time. The fundamental defect of the theory is that it creates

a cascade of increasingly complex relationships that require

unrealistic explanations, such as great tectonic uplift, excessive

amounts of alluviation, and greater depths of valley cutting dur-

ing erosion cycles. Also the characteristic angular grains of

quartz are not explained by this theory.

Distribution

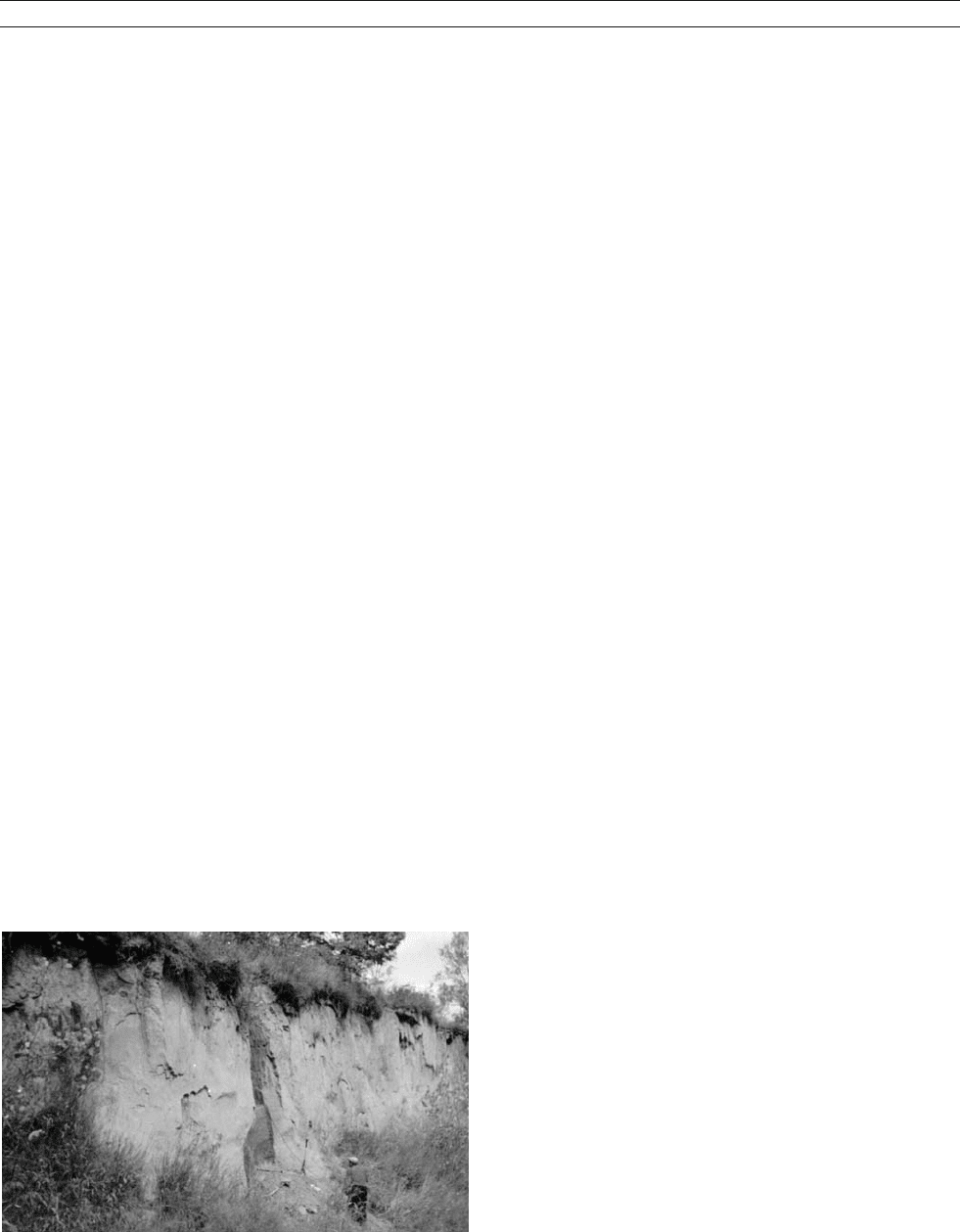

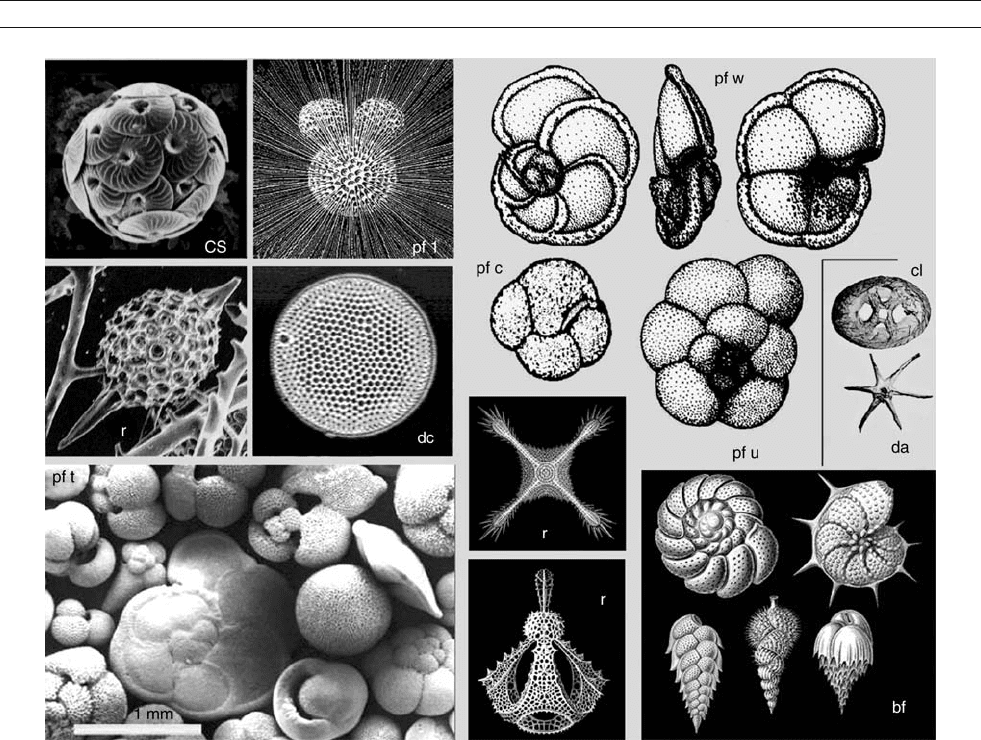

Loess is one of the widest-spread formations of the ice age, but

it also forms on semi-arid desert margins and on foothills of

mountain ranges. Loess sediments cover almost 10% of the

world’s land surfaces. Extensive loess and loess-like sediments

occur on plains, plateaus, pediments and major river basins

(Figure L24). Loess reaches its maximum thickness ( > 100 m)

on the Loess Plateau of China, but usually loess series are not more

than 30 m thick. In Eurasia, typical loess is also common in south-

ern Siberia, central Asia, on the Russian Plain, in central Europe,

and in isolated areas in Western Europe. Loess is widespread on

the Columbia Plateau and Mississippi basin in North America

and on La Plata basin in South America.

Outside the present-day temperate belt, non-typical loess vari-

eties have developed. They vary in clay and sand content, mineral

composition and color. Some loess, such as that in New Zealand

and Argentina has a high content of volcanic glass and feldspars,

while loess in parts of Central Asia, the Rhine Valley and the Mis-

sissippi Valley has a high content of carbonate minerals (up to

30%). Some deposits, such as those of Nebraska, contain up to

40% sand (sandy loess). At the other end of the spectrum, fine-

grained loesses on the southeastern and eastern marginsof the Chi-

nese Loess Plateau and Tadjikistan have more than 20% clay

(clayey loess). Brownish-pink loess varieties are common in the

Mediterranean climatic zone (Kashmir, Pakistan, Iran, Israel,

North Africa and New Zealand) and non-calcareous loesses were

formed under relatively humid environmental conditions in some

regions. A special loess variety, the “yedoma” loess-ice complex,

occurs in large patches in northeastern Siberia, in the permafrost

tundra zone. Along Yukon River in Alaska and on the Loess

Plateau of China, high rates of loess deposition continue today.

Konstantin G. Dlussky

Bibliography

Follmer, L.R., 1996. Loess studies in central United States: Evolution of

concepts. Engin. Geol., 45, 287–304.

Liu, T., et al., 1985. Loess and the environment, Beijing, China: China

Ocean Press, 251pp.

Pécsi, M., 1990. Loess is not just the accumulation of dust. Quat. Int., 7/8,

1–21.

Pye, K., 1995. The nature, origin and accumulation of loess. Quat. Sci.

Rev., 14, 653–667.

Smalley, I.J. (ed.), 1975. Loess: lithology and Genesis. Benchmark Papers in

Geology, vol. 26. Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, 429pp.

Cross-references

Dust Transport, Quaternary

Eolian Sediments and Processes

Glaciations, Quaternary

Mineral Indicators of Past Climates

Paleosols – Quaternary

Sedimentary Indicators of Climate Change

Wisconsinan (Weichselian, Würm) Glaciation

Figure L24 Distribution of loess and loess-like sediments. 1: Loess and loess-like sediments; 2: Loess derivates and loess-like sediments (after

Pe

´

csi, 1990).

524 LOESS DEPOSITS

M

MARINE BIOGENIC SEDIMENTS

General features

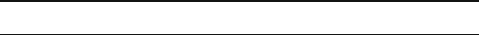

Biogenic (or biogenous) sediments are ubiquitous in marine

environments; the main divisions are readily classified with

reference to the amount of carbonate present and the depth of

water at which they are found (shallow or deep). The dominant

types are (in the order of abundance): deep-sea carbonates (cal-

careous ooze, foraminifer ooze, nannofossil ooze); deep-sea

siliceous deposits (siliceous ooze, diatom ooze, radiolarian

ooze); hemipelagic silica-rich deposits (at continental margins

below upwelling regions); shelf carbonate deposits (reef and

platform carbonates, dominated by coral and algal debris or

by foraminifer and mollusk materials, depending on circum-

stances; reefal debris, lagoonal carbonate muds, etc.); and var-

ious types of anaerobic deposits (rich in organic matter and

with or without opal or carbonate). Because deep sea covers

most of the surface of the planet, the dominant biogenic depos-

its are deep-sea sediments, and their dominant ingredient is

pelagic plankton, reflecting the fact that production is tied to

sunlight (Figure M1).

The key ingredients of biogenic sediments are therefore cal-

cium carbonate, opaline silica, and organic matter; the first two

of these ingredients are largely in the shape of microfossils on

the deep-sea floor (Funnell and Riedel, 1971; H. C. Jenkyns, in

Reading, 1986). Opaline fossils and organic matter tend to

occur together (but not invariably so) and are generally found

in high productivity regions. While carbonate is precipitated

in such regions, it tends to be dissolved because a high supply

of organic matter will increase carbon dioxide levels at the

water-sediment interface, which produces carbonic acid. This

circumstance was well understood by John Murray of the Chal-

lenger Expedition in the nineteenth century. Murray also pro-

vided the main subdivisions of deep-sea sediments and noted

that deep-sea carbonates tend to occur in the shallower half

of the deep-sea floor. The boundary is referred to as the “carbo-

nate compensation depth” or CCD. It is the largest of the bio-

genic sedimentary features on Earth and reflects a balance

between rate of supply (almost all from calcareous plankton)

and rates of dissolution (which increase with depth). The level

of the CCD responds to the carbon chemistry of deep waters,

and is quite different in the North Atlantic (deepest, below

5 km) and North Pacific (shallowest, above 4 km north of the

equator). Roughly, this level runs parallel to the “apparent oxy-

gen utilization”; that is, the amount of oxygen in deep water

that has been converted to carbon dioxide. Because of this rela-

tionship, fluctuations of the CCD through time are useful in the

reconstruction of the marine carbon cycle, and provide (some)

clues to changes in the sharing of carbon dioxide between

ocean and atmosphere. Quite generally, the deposition of bio-

genic sediments and the record contained therein are crucial

ingredients in defining the machinery of global biogeochemical

processes (e.g., Butcher et al., 1992).

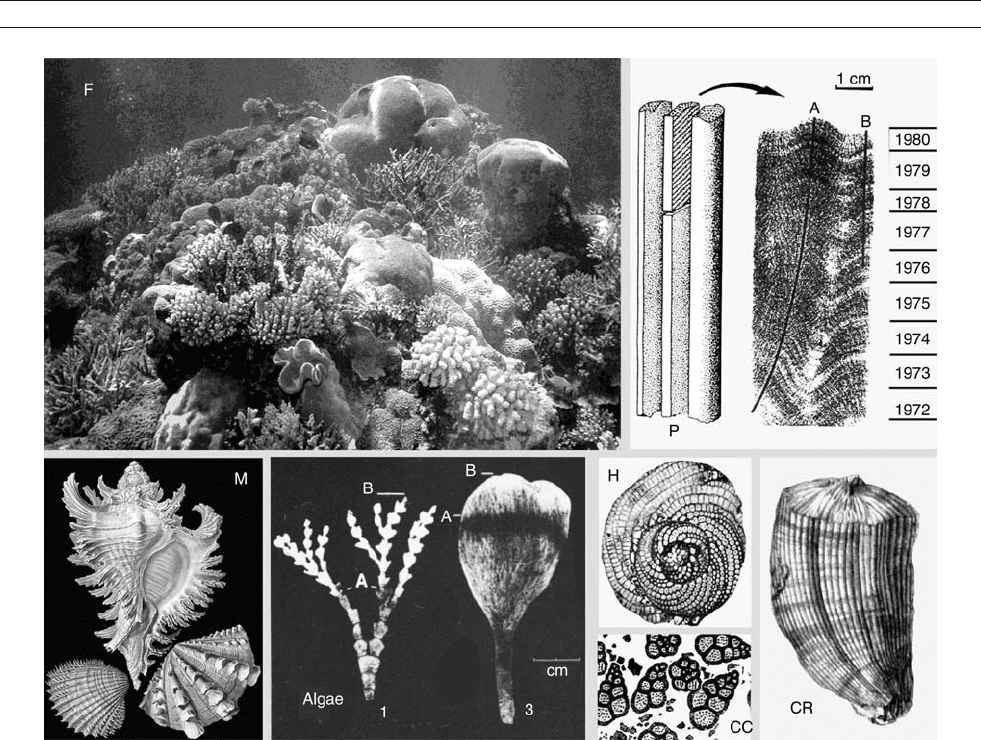

Shallow-water carbonate deposits

Biogenic sediments in the sea consist of fossils or fragments of

fossils. Initially, it was the study of fossils (paleontology) that

dealt with their origin and applied this knowledge in biostrati-

graphy (the dating of sedimentary sequences and the tracing

of evolution) and the reconstruction of environments of the past

(paleoecology, paleoclimatology, paleoceanography). Geolo-

gists interested in these subjects studied modern shallow-water

environments, beginning in the nineteenth century, with empha-

sis on corals, mollusks, foraminifers and other organisms pro-

ducing hard parts of carbonate. Reefs provided an early focus

and attractor because fossil diversity tends to be high in reefs

(“bioherms”) preserved in the geologic record (for an overview,

see B. W. Sellwood, in Reading, 1986). From the 1950s, devel-

opments in scuba diving opened entirely new avenues for direct

observation and for experiments (Figure M2). Sampling sub-

merged coral now routinely provides information about past

conditions of growth, based on the measurement of growth

bands, supplemented by chemical analysis. The study of mod-

ern environments and of the record preserved in skeletal struc-

tures has provided tools to study ancient environments as well,

using fossils from the appropriate time. The information sought

includes depth of water, temperature, productivity, dynamic

interactions between organisms and environment and between

the organisms themselves, the role of disturbance, and seasonal

variation. Above all, fossils – whether large or small (macro- or

micro- or nanno-fossils) – record their environment of growth.

If they do not like the extant conditions, they may shut down

and record nothing (“biased reporting”). To gather information

about past climate conditions, therefore, one has to employ sev-

eral lines of evidence, using paleontology, sedimentology, geo-

chemistry, and physical principles in a best-guess approach to

reconstruction.

The largest biogenic structure on the planet is the Great

Barrier Reef (GBR) off the northeastern coast of Australia.

Drilling (by the drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution, in the

context of the international Ocean Drilling Program (ODP,

1985–2003)) has demonstrated that the bulk of the structure

is geologically young, less than one million years old. Presum-

ably, the origin of the great reef is tied to the large sea level

fluctuations that occurred after 800,000 years ago. Reefs are

rubble factories, and sea level fluctuations stimulate rubble

production. In particular, the periods of rapid rise during

the melting of large ice sheets would have favored survival

and expansion of rapidly growing species, such as those

belonging to the genus Acropora. In addition, sometime after

the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Shift (see below), the Western

Equatorial Warm Pool expanded southward to the region of the

GBR, presumably aided by the clogging of the warm-water exit

into the Indian Ocean and by the reef rubble produced around

Indonesian islands. The GBR is a highly irregular structure

(Figure M3). Its features and those of other reefs in the South

Pacific erode during low stands of sea level (especially chemical

erosion; Purdy, 1974), and build up during high stands favoring

shallow ground. Without sea level fluctuation and attendant ero-

sion, the product of reef growth is a carbonate platform.

Deep-sea carbonate deposits

Calcareous ooze rich in foraminifers was first discovered as a

widespread deposit on the deep-sea floor in the middle of the

nineteenth century. It was not clear, initially, whether the bio-

genic remains evident within the ooze originated on the sea

floor or in the water. John Murray showed, by comparing

plankton samples with sediment samples, that the bulk of the

sand-sized material consists of planktonic foraminifers (“Globi-

gerina ooze” ). He also realized that the preservation of these

fossils deteriorates with depth in the water, such that all carbo-

nate would be dissolved below some depth (now known as the

Figure M1 Key ingredients of the dominant biogenic sediments on Earth; that is, deep-sea calcareous and siliceous ooze. cs: Coccolithophorid

(ca. 20 mm; B. Donner, Bremen); pf l: living planktonic foraminifer within its halo of spines (E. Haeckel); r: (leftmost) radiolarian (C. Samtleben, Kiel);

dc: centric diatom (O. Romero, Bremen); pf t: tropical assemblage of planktonic foraminifers (M. Yasuda, SIO); pf w: warm-water planktonic

foraminifer (F. L. Parker, 1962); pf c: cold-water species; pf u: upwelling species; cl: coccolith; da: discoaster (both D. Bukry and M. N. Bramlette,

1969); r: radiolarians (E. Haeckel); bf: benthic foraminifers (E. Haeckel).

526 MARINE BIOGENIC SEDIMENTS

CCD), leaving only “Red Clay.” The CCD describes the nar-

row depth-dependent zone where carbonate-rich sediments give

way to red clay and other carbonate-poor deposits bathed by

undersaturated waters. A more subtle assessment of conditions

on the sea floor at the time of deposition is possible by noting

the state of preservation of calcareous fossils (Figure M4). A

narrow zone separating well-preserved from poorly preserved

fossils within the calcareous ooze defines the level of the “lyso-

cline.” The lysocline fluctuates through time as a result of

changes in deep circulation, which affects oxygen and carbon

dioxide content of deep waters. Quite generally, patterns of pre-

servation (taphonomy) hold a large amount of information

regarding the environmental conditions during deposition of

biogenic sediments.

The fact that rates of carbonate accumulation change consid-

erably in a given region of the deep-sea floor was discovered

during the Swedish Deep-Sea Expedition (1947–1948). It was

especially obvious in the eastern equatorial Pacific, where sedi-

ments show regular cycles of light and dark colors, associated

with high and low carbonate content. Both fluctuations in car-

bonate production and fluctuations in the intensity of carbonate

dissolution can produce such cycles. The sediment cycles were

linked to productivity fluctuations that were in turn ascribed to

changing trade wind intensities and equatorial upwelling, with

ice ages having the stronger winds and increased upwelling

(Arrhenius, 1952). In general, these concepts were supported

by later studies, although the light-dark cycles are largely a

result of variations in the intensity of carbonate dissolution.

Overall, calcareous nannofossils are the dominant compo-

nent of calcareous ooze, especially in the large regions of low

productivity below the central gyres. Thus, the typical biogenic

deposit on the planet is coccolith ooze. Study of the minute

coccoliths (platelets shed from coccolithophorids, Figure M1,

upper left) requires the use of powerful microscopes. The

invention and spread of scanning electron microscopes greatly

aided in producing inventories and detailed descriptions of

these fossils (Winter and Siesser, 1994). The pioneer work

was done using petrologic microscopes, and these instruments

still are the preferred tools for routine shipboard analysis, i.e.,

for the biostratigraphic dating of sediments during drilling

expeditions. The presence of easily recognized nannofossils

known as “discoasters” (Figure M1, far right) indicates an

age greater than Quaternary, for example. Discoasters died

out at the end of the Pliocene.

Figure M2 Shallow-water calcareous biogenic sediments originate from carbonate-secreting organisms such as corals, mollusks, algae, and

foraminifers. F: Tropical coral reef at Fanning Island (SIO photo); P: core sample from a specimen of Porites from the western tropical Pacific

(J. Pa

¨

tzold, Bremen); M: armored mollusks (E. Haeckel); Algae, in situ staining of calcareous algae in Bermuda (Halimeda, Penicillus) to determine

rate of growth (G. Wefer); H: Heterostegina, a large benthic foraminifer bearing photosynthesizing symbionts (A. Loeblich and H. Tappan); CC:

foraminifers in Cretaceous chalk (M. Neumayr); CR: Cretaceous mollusk, reef-forming in places (rudist pelecypod, M. Neumayr).

MARINE BIOGENIC SEDIMENTS 527

In places, especially on relatively shallow regions of the

Atlantic, calcareous ooze contains the shells of pelagic gastro-

pods, in varying proportions. Such shells are made of arago-

nite, a polymorph of calcium carbonate that is much more

soluble than calcite. The shells are typically 1 cm long; where

dominant (made so by bottom currents washing the sediment)

they constitute “pteropod ooze.”

The process of seafloor spreading slowly moves calcareous

sediments to greater depth, on a million-year time scale. Thus,

as a general rule, deep-sea sediments overlying basaltic base-

ment (generated at the spreading center) should be rich in car-

bonate, while sediments overlying these older deposits should

have less carbonate. That is, by the principles of “plate strati-

graphy,” sediments at the bottom of the stack were originally

deposited at shallower depths above the CCD near the spreading

center. As the plates moved apart and the ocean floor subsided,

older sediments fell below the CCD. Reality is more compli-

cated because of large fluctuations of the CCD through geo-

logic time. The largest such excursion was the enormous drop

of the CCD to deeper levels around 40 million years ago

(Figure M5). This drop (toward the end of the Eocene) repre-

sents a large shift in carbonate accumulation patterns, from shelf

to deep sea. It heralds the beginning of the great cooling that

dominated the Cenozoic and illustrates the importance of moun-

tain building (uplift on land removes shelf seas) in the course of

this cooling. The marked drop of the CCD in the Atlantic since

about 10 Ma marks the turning on of deepwater production there;

that is, a filling of the basin with more saturated waters (said to be

“young”). At the same time, opaline fossils on the sea floor dis-

solved more easily from that time onwards (young water bears

less silicate than old) and there was an overall shift of silica

deposition from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

The Auversian Facies Shift at 40 million years ago, when

carbonate deposits become widespread on the deep-sea floor,

is well expressed in the acoustic stratigraphy of deep-sea depo-

sits. The shift is recognized in the western tropical Pacific as a

marked change from highly reflective layers (interbedded lime-

stones and chert) to more or less transparent (echo-lacking)

chalk sequences. The fundamental reason for this development

is twofold: the switch of carbonate deposition from shelves to

the deep-sea floor, and the removal of opal into upwelling

regions by diatom deposition, including in the belt around

Antarctica. Upwelling is a function of winds, and winds are dri-

ven by temperature gradients, hence zonal winds that drive

year-round upwelling increase with polar cooling.

Ocean and climate history

The study of biogenic sediments, especially those recovered

from the deep-sea floor, provides the basis for reconstruction

of ocean and climate history for the last 100 million years or

so (paleoceanography). Information for periods before this time

is difficult to obtain because seafloor subduction removes the

evidence. The main tool in reconstruction is a detailed biostra-

tigraphy (Berggren et al., 1985; Bolli and Saunders, 1985),

greatly aided by coordination with the history of magnetic

reversals. The main clues for reconstruction are derived from

a combination of biogeography and stable isotopes, notable

oxygen and carbon isotopes (Vincent and Berger, 1981;

Kennett, 1985; Wefer and Berger, 1991), complemented by a

large number of additional proxies for environmental condi-

tions (Hay, 1988; Fischer and Wefer, 1999). The most detailed

reconstructions have centered on the last glacial maximum

(following the CLIMAP studies, 1976) and on the sequence

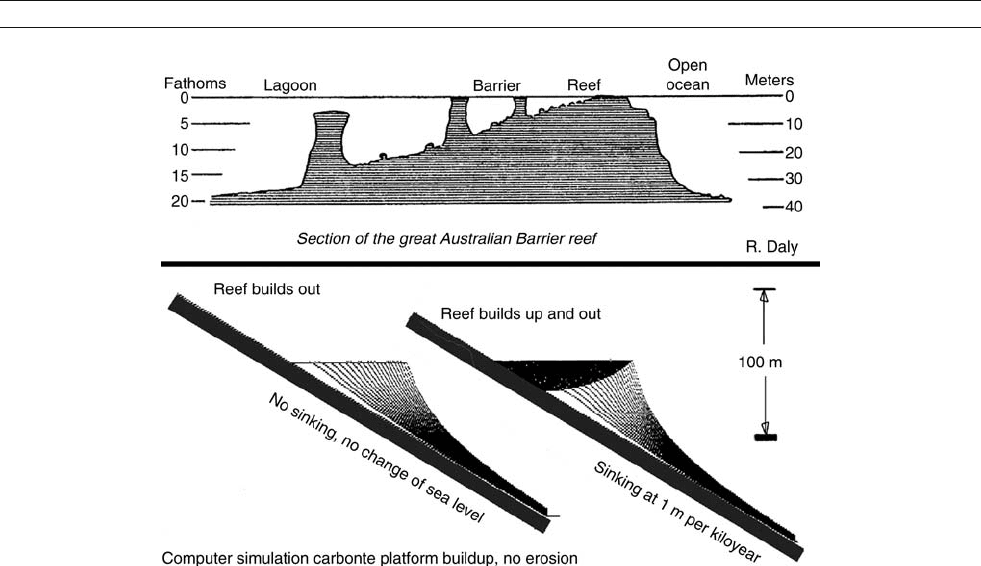

Figure M3 Nature of the Great Barrier Reef, as a product of differential buildup (during high sealevel stand) and erosion (during low stands). Upper:

Profile through Great Barrier Reef, drawn by R. Daly (1934). Lower: basic structure of a carbonate platform as expected for constant sea level

and slow sinking of the foundation (W.H.B., unpublished).

528 MARINE BIOGENIC SEDIMENTS