Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BOGARTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

309

Humphrey Bogart in a scene from the film The Maltese Falcon.

together and blow’’ phrase—became a signature of their inter-

personal dynamic off-screen as well. Film critic Molly Haskell

celebrates them as one of ‘‘the best of the classical couples’’ because

they brought to the screen ‘‘the kind of morally and socially beneficial

’pedagogic’ relationship that Lionel Trilling finds in Jane Austen’s

characters, the ’intelligent love’ in which two partners instruct,

inform, educate, and influence each other in the continuous college of

love.’’ Bogart, who was known for his misogyny and violent temper,

had found a woman who knew how to put him in his place with an

economical glance or a spontaneous retort. It was common for his

‘‘rat pack’’ of male friends to populate the house but Bacall was

perceived as a wife who rarely relinquished the upper hand. Their

marriage produced two children, Stephen (after Bogart’s character in

To Have and Have Not) and Leslie (after Leslie Howard).

A noticeable shift occurred in the kinds of characters Bogart

played in the 1940s. The tough guy attempting to be moral in an

immoral world became less socially acceptable as many American

husbands and wives tried to settle into a home life that would help

anesthetize them from the trauma of war. The complicated and

reactive principles associated with the star’s persona suddenly seemed

more troublesome and less containable. His film Treasure of the

Sierra Madre (1948), in which Bogart plays a greedy, conniving

prospector, marks this trend but In a Lonely Place (1948) is a lesser

known and equally remarkable film, partly because his role is that of a

screenwriter disenchanted with Hollywood. It was at this time that he

also formed his Santana production company which granted him

more autonomy in his choice and development of projects.

In the early 1950s, Bogart became one of the key figures to speak

out against the House Un-American Activities Committee which

gave him an opportunity to voice his ideals of democracy and free

speech. He also revived his career with The African Queen (1951), for

which he won an Academy Award. Later, he experimented with more

comedic roles in films such as Billy Wilder’s Sabrina (1954) and

We’re No Angels (1955). In 1956, the long-time smoker underwent

surgery for cancer of the esophagus and he died of emphysema in

early 1957.

Bogart’s status as a cultural icon was renewed in the 1960s when

counter-culture audiences were introduced to his films through film

festivals in Boston and New York which then spread to small college

towns. The Bogart ‘‘cult’’ offered a retreat into macho, rugged

individualism at a time when burgeoning social movements contrib-

uted to increased anxiety over masculine norms. This cult saw a

BOK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

310

resurgence in the 1990s with a spate of biographies about the star and

the issuance of a commemorative postage stamp.

—Christina Lane

F

URTHER READING:

Bacall, Lauren. Lauren Bacall by Myself. New York, Ballantine, 1978.

Bogart, Stephen Humphrey, with Gary Provost. Bogart: In Search of

My Father. New York, Dutton, 1995.

Cohen, Steven. Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies of the

Fifties. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1997.

Haskell, Molly. From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women

in the Movies. New York, Penguin Books, 1974.

Huston, John. An Open Book. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.

Hyams, Joe. Bogart and Bacall: A Love Story. New York, David

McKay Company, 1975.

Meyers, Jeffrey. Bogart: A Life in Hollywood. Boston and New York,

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997.

Sklar, Robert. City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield. Princeton, Princeton

University Press, 1992.

Sperber, A.M., and Eric Lax. Bogart. New York, William Morrow

and Company, 1997.

Bok, Edward (1863-1930)

An immigrant from the Netherlands, journalist and social re-

former Edward Bok emphasized the virtues of hard work and assimi-

lation in his 1920 autobiography, The Americanization of Edward

Bok, which won the Pulitzer Prize for biography and was reprinted in

60 editions over the next two decades. As one of America’s most

prominent magazine editors around the turn of the twentieth century,

Bok originated the concept of the modern mass-circulation women’s

magazine during his 30-year tenure (1889-1919) as editor of the

Ladies’ Home Journal. His editorship coincided with a period of

profound change, as the United States shifted from an agrarian to an

urban society, and his was a prominent voice in defining and

explaining these changes to a newly emergent middle class often

unsure of its role in the new order of things. ‘‘He outdid his readers in

his faith in the myths and hopes of his adopted country,’’ wrote Salme

Harju Steinberg in her 1979 study, Reformer in the Marketplace.

‘‘His sentiments were all the more compelling because they reflected

not so much what his readers did believe as what they thought they

should believe.’’ Under his guidance, the Ladies’ Home Journal was

the first magazine to reach a circulation of one million readers, which

then doubled to two million as it became an advocate of many

progressive causes of its era, such as conservation, public health, birth

control, sanitation, and educational reform. Paradoxically, the maga-

zine remained neutral on the issue of women’s suffrage until Bok

finally expressed opposition to it in a March 1912 editorial, claiming

that women were not yet ready for the vote.

Edward Bok was born to a politically prominent family in Den

Helder, the Netherlands, on October 9, 1863, the younger son of

William John Hidde Bok and Sieke Gertrude van Herwerden Bok.

After suffering financial reverses, the family emigrated to the United

States and settled in Brooklyn, New York, where from the age of ten,

young Edward began working in a variety of jobs, including window

washer, office boy, and stringer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. His

first publishing jobs were as a stenographer with Henry Holt &

Company and Charles Scribner’s Sons. In the 1880s, Bok became

editor of the Brooklyn Magazine, which had evolved from a publica-

tion he edited for Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church. In 1886

he and Frederic L. Colver launched Bok Syndicate Press, the first to

widely employ women as contributors. The following year, Scribner’s

Magazine hired Bok as advertising manager.

In 1889, shortly after his 26th birthday, Bok became editor-in-

chief of the Ladies’ Home Journal, which had been founded six years

earlier by Cyrus H. K. Curtis, whose only daughter, Mary Louise,

became Bok’s wife in 1896. Although Bok made the Ladies’ Home

Journal a vehicle for social change, he avoided taking sides in the

controversial labor vs. capital political issues of the day. With a solid

appeal to the emerging middle classes, Bok’s editorials preached a

Protestant work ethic couched in an Emersonian language of indi-

vidual betterment. By employing contributing writers such as Jane

Addams, Edward Bellamy, and Helen Keller, Bok helped create a

national climate of opinion that dovetailed with the growing progres-

sive movement. While advocacy of ‘‘do-good’’ projects put the

Journal at odds with more radical muckraking periodicals of the

period, Bok can still be credited with raising popular consciousness

about the ills of unbridled industrialism. His ‘‘Beautiful America’’

campaign, for example, raised public ire against the erection of

mammoth billboards on the rim of the Grand Canyon, and against the

further despoiling of Niagara Falls by electric-power plants. Riding

the crest of the ‘‘City Beautiful’’ movement that followed the 1892

Chicago World’s Fair, Bok opened the pages of the Journal to

architects, who offered building plans and specifications for attrac-

tive, low-cost homes, thousands of which were built in the newer

suburban developments. Praising this initiative, President Theodore

Roosevelt said ‘‘Bok is the only man I ever heard of who changed, for

the better, the architecture of an entire nation, and he did it so quickly

and yet so effectively that we didn’t know it was begun before it

was finished.’’

The Ladies’ Home Journal became the first magazine to ban

advertising of patent medicines, and Bok campaigned strenuously

against alcohol-based nostrums, a catalyst for the landmark Food and

Drug Act in 1906. The magazine was also ahead of its time in

advocating sex education, though its editorials were hardly explicit by

late-twentieth-century standards. Even before the United States had

entered World War I, Bok, who was vice president of the Belgian

Relief Fund and an advisor to President Woodrow Wilson, editorial-

ized that American women could contribute to peace and democracy

through preparedness, food conservation, and support of the Red

Cross and other relief efforts.

After his forced retirement in 1919, Bok published his autobiog-

raphy and devoted himself to humanitarian causes. Swimming against

the tide of isolationism after World War I, Bok tried to get Americans

interested in the League of Nations and the World Court. In 1923, he

established the American Peace Award, a prize of $100,000 to be

awarded for plans for international cooperation. He also endowed the

Woodrow Wilson Chair of Government at Williams College, named

for the beleaguered president who failed to convince his fellow

citizens to join the League of Nations. Bok died on January 9, 1930

and was buried at the foot of the Singing Tower, a carillon he built in a

bird preserve in Lake Wales, Florida.

—Edward Moran

BOMBENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

311

FURTHER READING:

Bok, Edward. America, Give Me a Chance. New York, Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1926.

———. The Americanization of Edward Bok. New York, Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

Peterson, Theodore. Magazines in the Twentieth Century. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 1964.

Steinberg, Salme Harju. Reformer in the Marketplace: Edward W.

Bok and The Ladies’ Home Journal. Baton Rouge and London,

Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Bolton, Judy

See Judy Bolton

The Bomb

For many observers, ‘‘Living with the Bomb’’ has become the

evocative phrase to describe life in twentieth-century America. The

cultural fallout from this technological innovation has influenced

economics, politics, and social policy and life long after its first

testing in the New Mexican desert in 1945. Americans have taken fear

of attack so seriously that school policies include provisions for

nuclear attack. Global politics became ‘‘polarized’’ by the two

nations in possession of nuclear technology. In the 1990s, global

relations remained extremely influenced by proliferation and the

threat of hostile nations acquiring nuclear capabilities. Clearly, ‘‘the

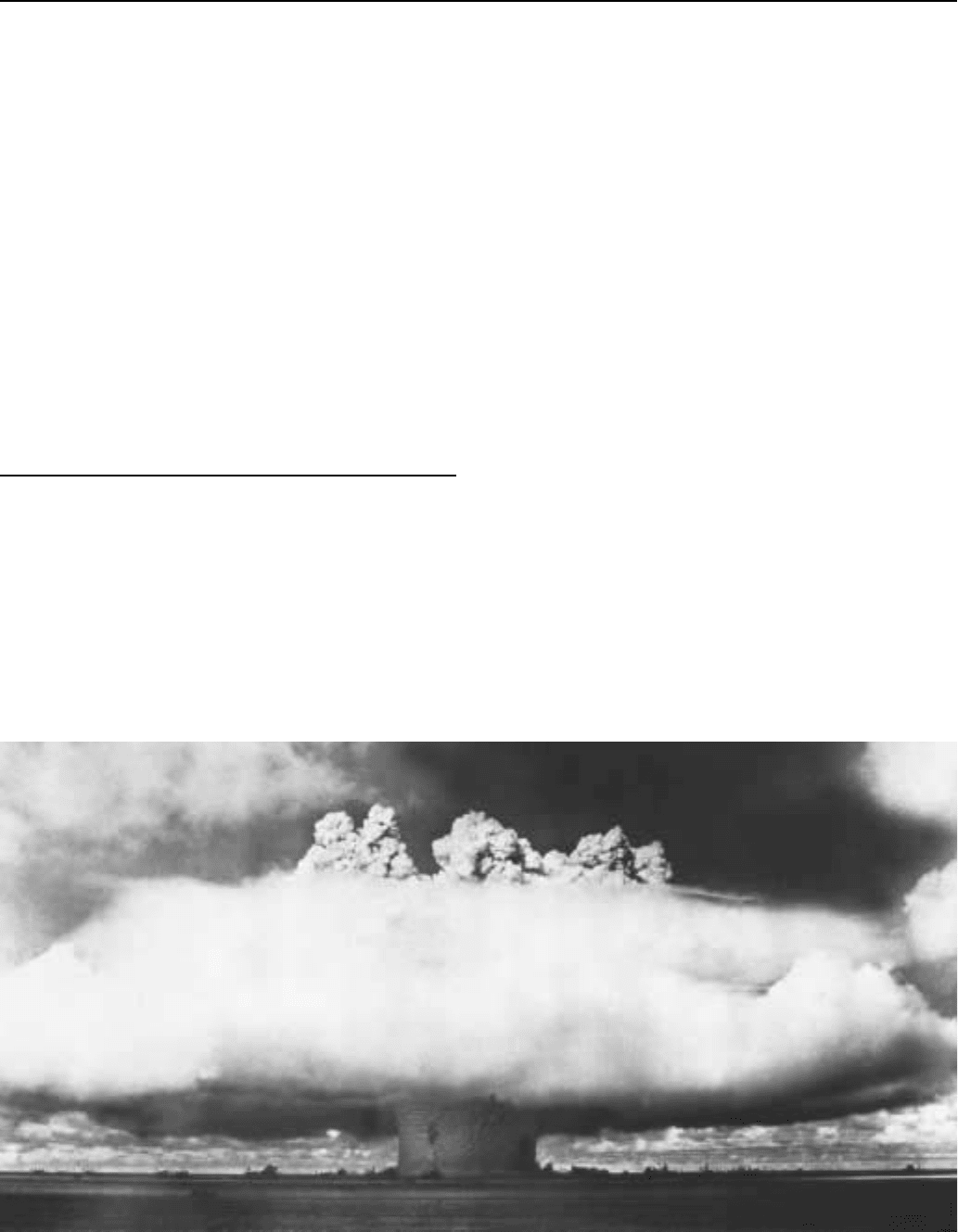

An atomic bomb mushroom cloud.

bomb’’ and all of atomic technology has carved a deep crater

of influence.

The technology to manage atomic reactions did not long remain

the sole domain of the military. The influence of nuclear weapons and

power generation has defined a great deal of domestic politics since

the 1960s. In recent years, such attention has come because of nuclear

technology’s environmental impact. If one considers these broader

implications and the related technologies, twentieth-century life has

been significantly influenced by ‘‘the bomb,’’ even though it has been

used sparingly—nearly not at all. The broader legacy of the bomb can

be seen on the landscape, from Chernobyl to the Bikini Atoll or from

Hiroshima to Hanford, Washington. Hanford’s legacy with the bomb

spans more time than possibly any other site. In fact, it frames

consideration of this issue by serving as site for the creation of the raw

material to construct the first nuclear weapons and consequently as

the ‘‘single most infected’’ site in the United States, now awaiting

Superfund cleanup. The site is a symbol of technological accomplish-

ment but also of ethical lessons learned.

In February 1943, the U.S. military through General Leslie

Groves acquired 500,000 acres of land near Hanford. This would be

the third location in the triad that would produce the atomic technolo-

gy. The coordinated activity of these three sites under the auspices of

the U.S. military became a path-breaking illustration of the planning

and strategy that would define many modern corporations. Hanford

used water power to separate plutonium and produce the grade

necessary for weapons use. Oak Ridge in Tennessee coordinated the

production of uranium. These production facilities then fueled the

heart of the undertaking, contained in Los Alamos, New Mexico,

under the direction of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer, a physicist, supervised the team of nuclear theore-

ticians who would devise the formulas making such atomic reactions

possible and manageable. Scientists from a variety of fields were

BOMB ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

312

involved in this highly complex theoretical mission. Once theories

were in place and materials delivered, the project became assembling

and testing the technology in the form of a bomb. All of this needed to

take place on the vast Los Alamos, New Mexico, compound under

complete secrecy. However, the urgency of war revealed that this

well-orchestrated, corporate-like enterprise remained the best bet to

save thousands of American lives.

By 1944, World War II had wrought a terrible price on the world.

The European theater would soon close with Germany’s surrender.

While Germany’s pursuit of atomic weapons technology had fueled

the efforts of American scientists, the surrender did not end the

project. The Pacific front remained active, and Japan did not accept

offers to surrender. ‘‘Project Trinity’’ moved forward, and it would

involve Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as the test laborato-

ries of initial atomic bomb explosions. Enola Gay released a uranium

bomb on the city of Hiroshima on August 6 and Bock’s Car released a

plutonium bomb on Nagasaki on August 9. Death tolls vary between

300-500,000, and most were Japanese civilians. The atomic age, and

life with the bomb, had begun.

Bomb tests in an effort to perfect the technology as well as to

design other types of weapons, including Hydrogen bombs, would

continue throughout the 1950s, particularly following the Soviet

Union’s successful detonation in 1949. Many of these tests became

publicity opportunities. For instance, the 1946 Pacific tests on the

Bikini Atoll were viewed on television and through print media by

millions worldwide. The technology became so awe-inspiring and

ubiquitous that a french designer named his new, two-piece women’s

bathing suit after the test. The bikini, linked with terms such as

‘‘bombshell,’’ became an enduring representation of the significant

impression of this new technology on the world’s psyche.

For Oppenheimer and many of the other scientists, the experi-

ence of working for the military had brought increasing alarm about

what the impact of their theoretical accomplishments would be. Many

watched in horror as the weapons were used on Japanese civilians.

Oppenheimer eventually felt that the public had changed attitudes

toward scientific exploration due to the bomb. ‘‘We have made a

thing,’’ he said in a 1946 speech, ‘‘a most terrible weapon, that has

altered abruptly and profoundly the nature of the world . . . a thing that

by all the standards of the world we grew up in is an evil thing.’’ It

brings up the question of whether or not, he went on, this technology

as well as all of science should be controlled or limited.

Many of the scientists involved believed that atomic technology

required controls unlike any previous innovation. Shortly after the

bombings, a movement began to establish a global board of scientists

who would administer the technology with no political affiliation.

While there were many problems with such a plan in the 1940s, it

proved impossible to wrest this new tool for global influence from the

American military and political leaders. The Atomic Energy Com-

mission (AEC), formed in 1946, would place the U.S. military and

governmental authority in control of the weapons technology and

other uses to which it might be put. With the ‘‘nuclear trump card,’’

the United States catapulted to the top of global leadership.

Such technological supremacy only enhanced Americans’ post

war expansion and optimism. The bomb became an important plank

to re-stoking American confidence in the security of its borders and its

place in the world. In addition to alcoholic drinks and cereal-box

prizes, atomic technology would creep into many facets of American

life. Polls show that few Americans considered moral implications to

the bombs’ use in 1945; instead, 85 percent approved, citing the need

to end the war and save American lives that might have been lost in a

Japanese invasion. Soon, the AEC seized this sensibility and began

plans for ‘‘domesticating the atom.’’ These ideas led to a barrage of

popular articles concerning a future in which roads were created

through the use of atomic bombs and radiation employed to cure cancer.

Atomic dreaming took many additional forms as well, particu-

larly when the AEC began speculating about power generation.

Initially, images of atomic-powered agriculture and automobiles

were sketched and speculated about in many popular periodicals. In

one book published during this wave of technological optimism, the

writer speculates that, ‘‘No baseball game will be called off on

account of rain in the Era of Atomic Energy.’’ After continuing this

litany of activities no longer to be influenced by climate or nature, the

author sums up the argument: ‘‘For the first time in the history of the

world man will have at his disposal energy in amounts sufficient to

cope with the forces of Mother Nature.’’ For many Americans, this

new technology meant control of everyday life. For the Eisenhower

Administration, the technology meant expansion of our economic and

commercial capabilities.

The Eisenhower Administration repeatedly sought ways of

‘‘domesticating’’ the atom. Primarily, this effort grew out of a desire

to educate the public without creating fear of possible attack. Howev-

er, educating the public on actual facts clearly took a subsidiary

position to instilling confidence. Most famously, ‘‘Project Plow-

shares’’ grew out of the Administration’s effort to take the destructive

weapon and make it a domestic power producer. The list was awe-

inspiring: laser-cut highways passing through mountains, nuclear-

powered greenhouses built by federal funds in the Midwest to

routinize crop production, and irradiating soils to simplify weed and

pest management. While domestic power production, with massive

federal subsidies, would be the long-term product of these actions, the

atom could never fully escape its military capabilities.

Americans of the 1950s could not at once stake military domi-

nance on a technology’s horrific power while also accepting it into

their everyday life. The leap was simply too great. This became

particularly difficult in 1949 when the Soviet Union tested its own

atomic weapon. The arms race had officially begun; a technology

that brought comfort following the ‘‘war to end all wars’’ now

forced an entire culture to realize its volatility—to live in fear of

nuclear annihilation.

Eisenhower’s efforts sought to manage the fear of nuclear attack,

and wound up creating a unique atomic culture. Civil defense efforts

constructed bomb shelters in public buildings and enforced school

children to practice ‘‘duck and cover’’ drills, just as students today

have fire drills. Many families purchased plans for personal bomb

shelters to be constructed in their backyards. Some followed through

with construction and outfitting the shelter for months of survival

should the United States experience a nuclear attack. Social controls

also limited the availability of the film On the Beach, which depicted

the effects of a nuclear attack, and David Bradley’s book No Place to

Hide. It was the censorship of Bradley, a scientist and physician

working for the Navy at the Bikini tests, that was the most troubling

oversight. Bradley’s account of his work after the tests presented the

public with its first knowledge of radiation—the realization that there

was more to the bomb than its immediate blast. The culture of control

was orchestrated informally, but Eisenhower also took strong politi-

cal action internationally. ‘‘Atoms for Peace’’ composed an interna-

tional series of policies during the 1950s that sought to have the

Soviets and Americans each offer the United Nations fissionable

material to be applied to peaceful uses. While the Cold War still had

BOMBENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

313

many chapters through which to pass, Eisenhower stimulated dis-

course on the topic of nuclear weapons from the outset.

Eisenhower’s ‘‘Atoms for Peace’’ speech, given at the United

Nations in 1953, clearly instructed the world on the technological

stand-off that confronted it. The ‘‘two atomic colossi,’’ he forecasted,

could continue to ‘‘eye each other indefinitely across a trembling

world.’’ But eventually their failure to find peace would result in war

and ‘‘the probability of civilization destroyed,’’ forcing ‘‘mankind to

begin all over again the age-old struggle upward from savagery

toward decency and right, and justice.’’ To Eisenhower, ‘‘no sane

member of the human race’’ could want this. In his estimation, the

only way out was discourse and understanding. With exactly these

battle lines, a war—referred to as cold, because it never escalates

(heats) to direct conflict—unfolded over the coming decades. With

ideology—communism versus capitalism—as its point of difference,

the conflict was fought through economics, diplomacy, and the

stockpiling of a military arsenal. With each side possessing a weapon

that could annihilate not just the opponent but the entire world, the

bomb defined a new philosophy of warfare.

The Cold War, lasting from 1949-1990, then may best be viewed

as an ongoing chess game, involving diplomats and physicists, while

the entire world prayed that neither player made the incorrect move.

Redefining ideas of attack and confrontation, the Cold War’s nuclear

arsenal required that each side live on the brink of war—referred to as

brinksmanship by American policy makers. Each ‘‘super power,’’ or

nuclear weapons nation, sought to remain militarily on the brink

while diplomatically dueling over economic and political influence

throughout the globe. Each nation sought to increase its ‘‘sphere of

influence’’ (or nations signed-on as like minded) and to limit the

others. Diplomats began to view the entire globe in such terms,

leading to wars in Korea and Vietnam over the ‘‘domino’’ assumption

that there were certain key nations that, if allowed to ally with a

superpower, could take an entire region with them. These two

conflicts defined the term ‘‘limited’’ warfare, which meant that

nuclear weapons were not used. However, in each conflict the use of

such weapons was hotly debated.

Finally, as the potential impact of the use of the bomb became

more clearly understood, the technological side of the Cold War

escalated into an ‘‘arms race’’ meant to stockpile resources more

quickly and in greater numbers than the other superpower. Historians

will remember this effort as possibly the most ridiculous outlet of

Cold War anxiety, because by 1990 the Soviets and Americans each

possessed the capability to destroy the earth hundreds of times. The

arms race grew out of one of the most disturbing aspects of the Cold

War, which was described by policy-makers as ‘‘MAD: mutually

assured destruction.’’ By 1960, each nation had adopted the philoso-

phy that any launch of a nuclear warhead would initiate massive

retaliation of its entire arsenal. Even a mistaken launch, of course,

could result in retaliatory action to destroy all life.

On an individual basis, humans had lived before in a tenuous

balance with survival as they struggled for food supplies with little

technology; however, never before had such a tenuous balance

derived only from man’s own technological innovation. Everyday

human life changed significantly with the realization that extinction

could arrive at any moment. Some Americans applied the lesson by

striving to live within limits of technology and resource use. Anti-

nuclear activists composed some of the earliest portions of the 1960s

counter culture and the modern environmental movement, including

Sea Shepherds and Greenpeace which grew out of protesting nuclear

testing. Other Americans were moved to live with fewer constraints

than every before: for instance, some historians have traced the

culture of excessive consumption to the realization that an attack was

imminent. Regardless of the exact reaction, American everyday life

had been significantly altered.

If Americans had managed to remain naive to the atomic

possibilities, the crisis of 1962 made the reality perfectly obvious.

U.S. intelligence sources located Soviet missiles in Cuba, 90 miles

from the American coast. Many options were entertained, including

bombing the missile sights; President John F. Kennedy, though,

elected to push ‘‘brinksmanship’’ further than it had ever before gone.

He stated that the missiles pressed the nuclear balance to the Soviet’s

advantage and that they must be removed. Kennedy squared off

against Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev in a direct confrontation with

the use of nuclear weapons as the only subsequent possibility for

escalation. Thirteen Days later, the Soviet Premier backed down and

removed the missiles. The world breathed a sigh of relief, realizing it

had come closer to destruction than ever before. For many observers,

there was also an unstated vow that the Cuban Missile Crisis must be

the last such threat.

The period of crisis created a new level of anxiety, however, that

revealed itself in a number of arenas. The well-known ‘‘atomic

clock,’’ calculated by a group of physicists, alerted the public to how

great the danger of nuclear war had become. The anxiety caused by

such potentialities, however, played out in a fascinating array of

popular films. An entire genre of science fiction films focused around

the unknown effects of radiation on subjects ranging from a beautiful

woman, to grasshoppers, to plants. Most impressively, the Godzilla

films dealt with Japanese feelings toward the effects of nuclear

technology. All of these films found a terrific following in the United

States. Over-sized lizards aside, another genre of film dealt with the

possibilities of nuclear war. On the Beach blazed the trail for many

films, including the well-known The Day After television mini-series.

Finally, the cult-classic of this genre, Dr. Strangelove starred Peter

Sellers in multiple performances as it posed the possibility of a

deranged individual initiating a worldwide nuclear holocaust. The

appeal of such films reveals the construction of what historian Paul

Boyer dubs an American ‘‘nuclear consciousness.’’

Such faith in nationalism, technological supremacy, and authori-

ty helped make Americans comfortable to watch above-ground

testing in the American West through the late 1950s. Since the danger

of radiation was not discussed, Americans often sat in cars or on lawn

chairs to witness the mushroom clouds from a ‘‘safe’’ distance.

Documentary films such as Atomic Cafe chronicle the effort to delude

or at least not fully inform the American public about dangers. Since

the testing, ‘‘down-winders’’ in Utah and elsewhere have reported

significant rises in leukemia rates as well as that of other types of

cancer. Maps of air patterns show that actually much of the nation

experienced some fall-out from these tests. The Cold War forced the

U.S. military to operate as if it were a period of war and certain types

of risks were necessary on the ‘‘home front.’’ At the time, a

population of Americans who were familiar with World War II

proved to be willing to make whatever sacrifices were necessary; later

generations would be less accepting.

Ironically, the first emphasis of this shift in public opinion would

not be nuclear arms, but its relative, nuclear power. While groups

argued for a freeze in the construction of nuclear arms and forced the

government to discontinue atomic weapons tests, Americans grew

increasingly comfortable with nuclear reactors in their neighbor-

hoods. The ‘‘Atoms for Peace’’ program of the 1950s aided in the

development of domestic energy production based on the nuclear

BOMBECK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

314

reaction. The exuberance for such power production became the

complete lack of immediate waste. There were other potential prob-

lems, but those were not yet clearly known to the American public. In

1979, a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania, which is

located within a working-class neighborhood outside of a major

population center, nearly experienced a nuclear melt down. As

pregnant women and children were evacuated from Pennsylvania’s

nearby capital, Harrisburg, the American public learned through the

media about the dangers of this technology. Most important, they

learned the vast amount that was not clearly understood about this

power source. As much of the nation waited for the cooling tower to

erupt in the mushroom cloud of an atomic blast, a clear connection

was finally made between the power source and the weapon. While

the danger passed quickly from Three Mile Island, nuclear power

would never recover from this momentary connection to potential

destruction; films such as China Syndrome (1979) and others

made certain.

When Ronald Reagan took office in 1980, he clearly perceived

the Cold War as an ongoing military confrontation with the bomb and

its production as its main battlefield. While presidents since Richard

Nixon had begun to negotiate with the Soviets for arms control

agreements, Reagan escalated production of weapons in an effort to

‘‘win’’ the Cold War without a shot ever being fired. While it resulted

in mammoth debt, Reagan’s strategy pressed the Soviets to keep pace,

which ultimately exacerbated weaknesses within the Soviet econo-

my. By 1990, the leaders of the two super powers agreed that the Cold

War was finished. While the Soviet Union crumbled, the nuclear

arsenal became a concern of a new type. Negotiations immediately

began to initiate dismantling much of the arsenal. However, the

control provided by bipolarity was shattered, and the disintegration of

the Soviet Union allowed for their nuclear weapons and knowledge to

become available to other countries for a cost. Nuclear proliferation

had become a reality.

In the 1990s, the domestic story of the bomb took dramatic turns

as the blind faith of patriotism broke and Americans began to confront

the nation’s atomic legacy. Vast sections of infected lands were

identified and lawsuits were brought by many ‘‘down-winders.’’

Under the administration of President Bill Clinton, the Department of

Energy released classified information that documented the govern-

ment’s knowledge of radiation and its effects on humans. Some of this

information had been gathered through tests conducted on military

and civilian personnel. Leading the list of fall-out from the age of the

bomb, Hanford, Washington, has been identified as one of the

nation’s most infected sites. Buried waste products have left the

area uninhabitable.

The panacea of nuclear safety has, ultimately, been completely

abandoned. Massive vaults, such as that in Yucca Mountain, Nevada,

have been constructed for the storage of spent fuel from nuclear

power plants and nuclear warheads. The Cold War lasted thirty to

forty years; the toxicity of much of the radioactive material will last

for nearly 50,000 years. The massive over-production of such materi-

al has created an enormous management burden for contemporary

Americans. This has become the next chapter in the story of the bomb

and its influence on American life.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Boyer, Paul. By The Bomb’s Early Light. Chapel Hill, University of

North Carolina Press, 1994.

Chafe, William H. The Unfinished Journey. New York, Oxford

University Press, 1995.

Hughes, Thomas P. American Genesis. New York, Penguin

Books, 1989.

May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound. New York, Basic Books, 1988.

May, Ernest R. American Cold War Strategy. Boston, Bedford

Books, 1993.

Bombeck, Erma (1927-1996)

Erma Bombeck, writer, humorist, and television personality,

was primarily identified as a housewife and mother. Because she

knew it so well, she was able to offer the housewife’s-eye-view of the

world in her writing. And it is because she took those roles so

seriously that she was able to show the humorous side of the life of

homemaker and mother so effectively.

She was born Erma Louise Fiste in Dayton, Ohio. Bombeck’s

mother, who worked in a factory, was only sixteen when Bombeck

was born, and her father was a crane operator who died when she was

nine years old. When little Erma showed talent for dancing and

singing, her mother hoped to make her into a child star—the next

Shirley Temple. But her daughter had other ideas. Drawn to writing

very early, Bombeck wrote her first humor column for her school

newspaper at age 13. By high school, she had started another paper at

school, and begun to work at the Dayton Herald as a copy girl

and reporter.

It was while working for the Herald that she met Bill Bombeck

and set her cap for him. They married in 1949. Bombeck continued to

write for the newspaper until 1953, when she and Bill adopted a child.

She stopped working to stay home with the baby and gave birth to two

more children over the next five years. Until 1965, Bombeck lived the

life of the suburban housewife, using humor to get her through the

everyday stress.

When her youngest child entered school, Bombeck wrote a

column and offered it to the Dayton newspaper, which bought it for

three dollars. Within a year ‘‘At Wit’s End’’ had been syndicated

across the country, and it would eventually be published by 600

papers. Bombeck also published collections of her columns, in books

with names like The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank

(1976) and Family: The Ties that Bind . . . and Gag (1987). Out of

twelve collections, eleven were bestsellers, and from 1975 to 1981,

she gained popularity on television with a regular spot on Good

Morning America.

Beginning in the 1960s when most media tried hard to glorify the

role of the homemaker with the likes of June Cleaver, Bombeck

approached the daily dilemmas of real life at home with the kids with

irreverence and affection. Because she was one of them, housewives

loved her gentle skewering of housework, kids, and husbands. Even

in the 1970s, with the rise of women’s liberation, Bombeck’s columns

retained their popularity. Because she treated her subject with re-

spect—she never made fun of housewives themselves, but of the

many obstacles they face—feminists could appreciate her humor.

Both mothers with careers and stay-at-home moms could find them-

selves in Bombeck’s columns—and laugh at the little absurdities of

life she was so skilled at pointing out.

Though Bombeck never called herself a feminist, she supported

women’s rights and actively worked in the 1970s for passage of the

BON JOVIENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

315

Equal Rights Amendment. She also worked for various humanitarian

causes, such as cancer research. One of her books, I Want to Grow

Hair, I Want to Grow Up, I Want to Go to Boise, describes her

interactions with children with cancer, something Bombeck herself

faced in 1992 when she was diagnosed with breast cancer and had a

mastectomy. She managed to find humor to share in writing about

even that experience. Shortly after her mastectomy, her kidneys

failed, due to a hereditary disease. Refusing to use her celebrity to

facilitate a transplant, she underwent daily dialysis for four years

before a kidney was available. She died at age 69 from complications

from the transplant.

In spite of her fame and success, Bombeck remained unpreten-

tious. She was able to write about American life from the point of

view of one of its most invisible participants, the housewife. From

that perspective, she discussed many social issues and united diverse

women by pointing out commonalities and finding humor in the

problems in their lives. Her tone was never condescending, but was

always lighthearted and conspiratorial. Fellow columnist Art Buchwald

said of Bombeck’s writing, ‘‘That stuff wouldn’t work if it was jokes.

What it was, was the truth.’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Bombeck, Erma. Erma Bombeck: Giant Economy Size. Garden City,

New York, Doubleday, 1983.

Colwell, Lynn Hutner. Erma Bombeck: Writer and Humorist. Hill-

side, New Jersey, Enslow Publishers, 1992.

Edwards, Susan. Erma Bombeck: A Life in Humor. New York, Avon

Books, 1998.

Bon Jovi

Slippery When Wet, Bon Jovi’s 1986 break-out album, brought

‘‘metal’’ inspired pop music to the forefront of American popular

culture. The album was Bon Jovi’s third effort for Mercury Records,

which had gone through a bidding war to get the group in 1984.

Slippery When Wet was different from Bon Jovi’s earlier albums, the

self-titled Bon Jovi and 7800 Fahrenheit, because the group hired a

professional songwriter to work on the project. Mercury Records also

invested an unprecedented amount of marketing research into the

album. The group recorded about 30 songs, which were played for

focus groups of teenagers, and the resulting album spawned two

number one singles, sold more than 10 million copies, and established

Bon Jovi as the premier ‘‘hair metal’’ band of the 1980s.

The band had humble beginnings. New Jersey rocker Jon

Bongiovi had recorded a single called ‘‘Runaway’’ with a group of

local notables, and when the single received good radio play he

decided to get a more permanent group together for local perform-

ances. Along with Bongiovi, who changed his last name to Bon Jovi,

guitarist Richie Sambora, bassist Alec John Such, keyboardist David

Rashbaum (changed to Bryan), and drummer Tico Torres were the

members of a the new group Bon Jovi. Alec John Such eventually left

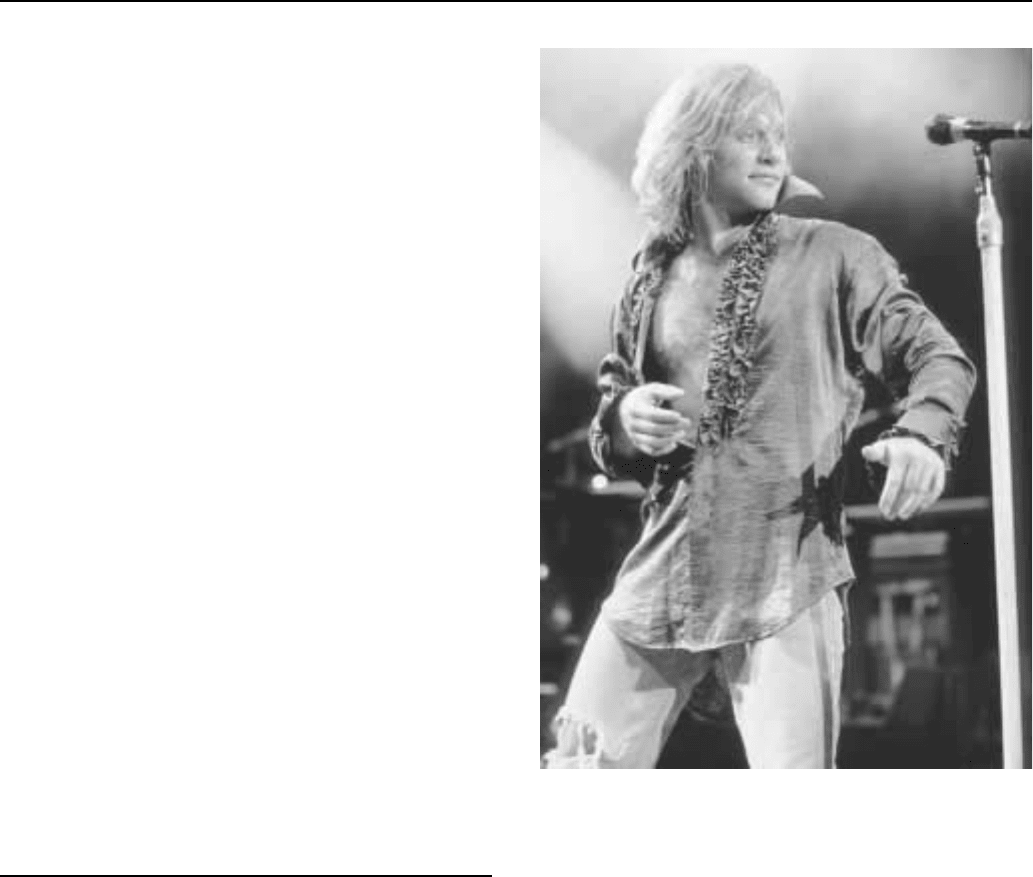

Jon Bon Jovi

the group in the early 1990s, and after that time no other members

have officially been added to Bon Jovi.

After the success of Slippery When Wet, the group came back

with New Jersey in 1988. The album was a big commercial success,

selling 8 million copies, but after the New Jersey tour the group took

some time apart for solo projects. Jon Bon Jovi found success

working on the soundtrack to Young Guns II in 1990, and guitarist

Sambora released Stranger in this Town in 1991.

Bon Jovi reunited to release Keep the Faith in the midst of the

Seattle-based grunge rock movement. Its sales were lower than

previous Bon Jovi efforts, but their tenth anniversary hits collection,

Crossroads, went multi-platinum. The release of These Days in 1994

was a departure from their rock-pop roots and had a more contempo-

rary sound. In the late 1990s, Jon Bon Jovi worked on solo projects

and an acting career. His first solo album, Destination Anywhere, was

released in 1997. It was accompanied by a mini-movie that got

exposure on MTV.

—Margaret E. Burns

F

URTHER READING:

Jeffries, Neil. Bon Jovi: A Biography. Philadelphia, Trans-Atlantic

Publications, Inc., 1997.

BONANZA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

316

Bonanza

The television series Bonanza was more than just another

western in an age that had an abundance of them; it was also a clever

marketing idea. First aired in 1959, it was especially developed to be

filmed for color viewing, in order to compel Americans to buy color

televisions. The series’ appeal derived from Bonanza’s gentle, family

orientation, which, of course, differed from Gunsmoke and most other

westerns. In most westerns, writes literary scholar Jane Tompkins, the

west ‘‘functions as a symbol of freedom, and of the . . . escape from

conditions of life in modern industrial society.’’ Bonanza met this

basic criteria, but it also contained more fistfights than gunfights and

centered around the occurrences of the Cartwrights, a loving, loyal

family. Many episodes dealt with important issues like prejudice at a

time when such themes were not common on television. In sum,

Bonanza used the touchstones of the western genre to package a

family drama that ran for fourteen years, until 1973.

Typical of westerns, Bonanza sought to detail the male world of

ranching. Untypical of the genre, Bonanza had a softer side to most of

its plots that combined with attractive actors to allow the show trans-

gender appeal. The Cartwrights, of course, began with Ben, played by

Canadian Lorne Greene. Generally serious and reasonable, Ben kept

the ranch running. Thrice widowed, he raised three boys on his own

with a little help from the cook, Hop Sing. There were no women on

the Ponderosa. Bonanza, like My Three Sons and Family Affair,

created a stable family without the traditional gender roles so palpable

in 1950s and 1960s America. Part of the popularity of such series

derives from the family’s success despite its lack of conformity.

Each Cartwright brother served a different constituency of

viewers. Adam, the eldest son, was played by Pernell Roberts. More

intense than his brothers, Adam had attended college and was less

likely to be involved in wild antics or love affairs. Dan Blocker played

Hoss Cartwright, gullible and not terribly bright yet as sweet and

gentle as he was huge. When not providing the might to defeat a

situation or individual, Hoss faced a series of hilarious situations,

often created by his younger brother, Little Joe. Michael Landon, who

played Little Joe, proved to be the most enduring of these 1960s-style

‘‘hunks.’’ The youngest member of the family, he was fun loving,

lighthearted, and often in love. The care-free son, Little Joe brought

levity to the family and the program. He was looked on by his father

and older brothers with affection, and was usually at the center of the

most humorous episodes. Landon came to Bonanza having starred in

feature films, including I Was A Teenage Werewolf, and he wrote and

directed many of the later episodes of Bonanza (though the series was

primarily directed by Lewis Allen and Robert Altman).

The West, of course, would always be more than backdrop to the

program. The general activities of the Cartwrights dealt with main-

taining control and influence over the Ponderosa, their vast ranch.

‘‘Conquest,’’ writes historian Patricia Nelson Limerick, ‘‘was a

literal, territorial form of economic growth. Westward expansion was

the most concrete, down-to-earth demonstration of the economic

habit on which the entire nation became dependent.’’ The West, and

at least partly the genre of westerns, become a fascinating representa-

tion for assessing America’s faith in this vision of progress. The

success of the Cartwrights was never in doubt; yet the exotic frontier

life consistently made viewers uncertain. The greatest appeal of

Bonanza was also what attracted many settlers westward: the

Cartwrights controlled their own fate. However, though plots in-

volved them in maintaining or controlling problems on the Ponderosa,

the family’s existence was not in the balance. The series succeeded by

taking necessary elements from the western and the family drama in

order to make Bonanza different from other programs in each genre.

This balance allowed Bonanza to appeal across gender lines and

age groups.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Brauer, Ralph, with Donna Brauer. The Horse, the Gun, and the Piece

of Property: Changing Images of the TV Western. Bowling Green,

Ohio, Popular Press, 1975.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken

Past of the American West. New York, W.W. Norton, 1988.

MacDonald, J. Fred. Who Shot the Sheriff?: The Rise and Fall of the

Television Western. New York, Praeger, 1987.

Tompkins, Jane. West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns. New

York, Oxford University Press, 1992.

West, Richard. Television Westerns: Major and Minor Series, 1946-

1978. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Co., 1987.

Yoggy, Gary A. Riding the Video Range: The Rise and Fall of the

Western on Television. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland &

Co., 1995.

Bonnie and Clyde

Despite their lowly deaths at the hands of Texas Rangers in

1934, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow have enjoyed second lives

within America’s popular imagination. Gunned down by Texas

authorities after a murderous bank-robbing spree, Parker and Barrow

occupied a dusty backroom of the national memory until 1967, when

a Warner Brothers feature film brought their tale of love, crime, and

violence back to the nation’s attention. Written by David Newman

and Robert Benton and directed by Arthur Penn, Bonnie and Clyde

tells a historically based yet heavily stylized story of romance and

escalating violence that announced the arrival of a ‘‘New American

Cinema’’ obsessed with picaresque crime stories and realistic vio-

lence. A major box-office hit, the film and its sympathetic depiction

of its outlaw protagonists struck a nerve on both sides of the

‘‘generation gap’’ of the late 1960s, moving some with its portrayal of

strong, independent cultural rebels while infuriating others by roman-

ticizing uncommonly vicious criminals.

Inspired by the success of John Toland’s book The Dillinger

Days (1963), writers Newman and Benton distilled their screenplay

from real-life events. In 1930, Bonnie Parker, a twenty-year-old

unemployed waitress whose first husband had been jailed, fell in love

with Clyde Barrow, a twenty-one-year-old, down-on-his-heels petty

thief. In 1934, following Barrow’s parole from the Texas state

penitentiary, Barrow and Parker and a growing number of accom-

plices set off on a peripatetic crime spree. Travelling around the

countryside in a Ford V-8, the Barrow gang held up filling stations,

dry-cleaners, grocery stores, and even banks in ten states in the

BONNIE AND CLYDEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

317

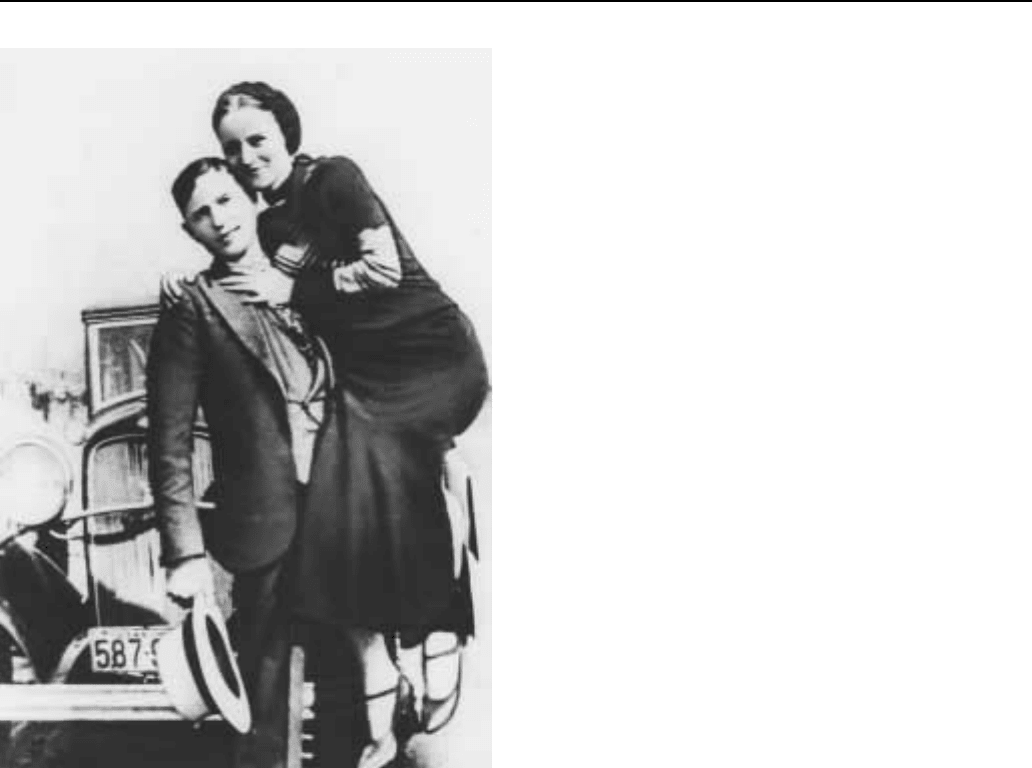

Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker.

Southwest and Midwest. In the process, they murdered—in a particu-

larly wanton manner—between twelve and fifteen innocent people.

Bonnie and Clyde’s bankrobbing binge came to a violent end in May

1934, when a former Texas Ranger named Frank Hamer, along with

three deputies, tricked the outlaws into a fatal ambush along a

highway outside Arcadia, Louisiana.

The Warner Brothers’ cinematic retelling of these events creates

the appearance of historical accuracy but makes a few revealing

additions and embellishments. The film opens when Bonnie Parker

(Faye Dunaway), first seen through the bars of her cage-like bed,

restlessly peers out of her window, catching Clyde Barrow (Warren

Beatty) attempting to steal her mother’s car. Young and bored,

Bonnie falls for the excitement that Clyde seems to represent. She

taunts the insecure Clyde, whose gun and suggestive toothpick hint at

a deep insecurity, into robbing the store across the street. Bonnie’s

quest for adventure and Clyde’s masculine overcompensation drive

the film, leading the two into an initially fun-filled and adventurous

life of petty larceny. Having exchanged poverty and ennui for the

excitement of the highway, the criminal couple soon attract accom-

plices: Clyde’s brother Buck (Gene Hackman), his sister-in-law

Blanche (Estelle Parsons), and C.W. (Michael J. Pollard), a mechani-

cally adept small-time thief. In a scene modelled after John Dillin-

ger’s life, the film makes Bonnie and Clyde into modern-day Robin

Hoods. While hiding out in an abandoned farmhouse, Bonnie and

Clyde meet its former owner, a farmer who lost it to a bank. They

show sympathy for him and even claim to rob banks, as if some kind

of social agenda motivated their crimes.

Careening around country roads to lively banjo tunes (performed

by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs), the gang’s encounters with the

authorities soon escalate, abruptly turning their light-hearted romp

into a growing nightmare. Playful scenes of mad-capped fun segue

into brutal, bloody shootouts. One police raid ends with Buck’s death,

Blanche’s capture, and a hair-raising getaway by Bonnie, Clyde, and

C.W. At this point, apparently tiring of their rootless escapades,

Bonnie and Clyde pine for a more traditional family life, but,

tragically, find themselves trapped in a cycle of violent confronta-

tions. Their escape comes when C.W’s father agrees to lure Bonnie

and Clyde into a trap in return for immunity for his son. To the tune of

joyful bluegrass, the colorful outlaws drive blithely into the ambush,

innocently unaware of the gory slow-motion deaths that await them.

The incongruous brutality of this dark ending left audiences

speechless and set off a national debate on film, violence, and

individual responsibility. Magazines such as Newsweek featured

Bonnie and Clyde on their covers. Many of the film’s themes, it

appeared—economic inequality, a younger generation’s search for

meaning, changing women’s roles, celebrity-making, escalation and

confrontation, violence—resonated with American audiences strug-

gling to make sense of JFK’s assassination, the Vietnam War, the

counterculture, student protests, and a mid-1960s explosion of violent

crime. Precisely because of Bonnie and Clyde’s contemporary rele-

vance, critics such as Bosley Crowther of the New York Times decried

its claims to historical authenticity. Clearly they had a point: by

transforming homely and heartless desperadoes into glamorous folk

heroes and by degrading and demonizing the authorities, especially

former Texas Ranger Hamer, whom many considered the real hero of

the story, the film did distort the historical record.

But glamorizing rebellion and violence, other critics such as

Pauline Kael contended, was not the point of the film, which instead

aimed to explore how ordinary people come to embrace reckless

attitudes toward violence. The film, they point out, punishes Bonnie

and Clyde—and by extension the audience—for their insouciant

acceptance of lawbreaking. Interestingly, the popular and critical

reception of Bonnie and Clyde appeared to recreate many of the

divides it sought to discuss.

—Thomas Robertson

F

URTHER READING:

Cott, Nancy F. ‘‘Bonnie and Clyde.’’ Past Imperfect: History Ac-

cording to the Movies. Edited by Mark Carnes. New York, Henry

Holt and Company, 1995.

Toplin, Robert Brent. ‘‘Bonnie and Clyde.’’ History by Hollywood:

The Use and Abuse of the American Past. Chicago, University of

Illinois Press, 1996.

Trehern, John. The Strange History of Bonnie and Clyde. Jonathan

Cape, 1984.

Bono, Sonny

See Sonny and Cher

BOOKER T. AND THE MG’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

318

Booker T. and the MG’s

The longtime Stax Records house band achieved fame not only

due to their musical abilities, but as an integrated band (two blacks

and two whites) working at a time of significant racial tension in the

United States. Though their most significant contribution was as a

backup band for Stax artists including Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding,

and Albert King, they also produced a number of their own Top 40

instrumentals, including ‘‘Green Onions,’’ which reached number

three in 1962. Through 1969, they produced five more Top 40 singles.

Though the group officially disbanded in 1971, they were

working on a reunion album in 1975 when drummer Al Jackson, Jr.

was killed tragically. Since then, the remaining members have contin-

ued to record both together and separately. Steve Cropper and Donald

‘‘Duck’’ Dunn, the group’s guitarist and bass player respectively,

also joined the Blues Brothers Band and appeared in both of their

major motion pictures.

—Marc R. Sykes

F

URTHER READING:

Bowman, Rob, and Robert M.J. Bowman. Soulsville, U.S.A.: The

Story of Stax Records. New York, Macmillan, 1997.

Book-of-the-Month Club

When advertising copywriter Harry Scherman founded the

Book-of-the-Month Club in 1926, he could hardly have predicted the

lasting impact his company would have on the literary and cultural

tastes of future generations. The Book-of-the-Month Club (BOMC)

developed over time into a cultural artifact of the twentieth century,

considered by many to be a formative element of ‘‘middlebrow’’

culture. With the monthly arrival of a book endorsed by a panel of

experts, aspirants to middle-class learnedness could be kept abreast of

literary trends through the convenience of mail order. The success of

this unique approach to book marketing is evidenced by the fact that

membership had grown to over one million by the end of the

twentieth century.

Born in Montreal, Canada, in 1887, Harry Scherman was a

highly resourceful marketer and a devout reader. He believed that the

love of reading and of owning books could be effectively marketed to

the ‘‘general reader,’’ an audience often neglected in the book

publishing industry of that period. Scherman’s first book marketing

scheme involved a partnership with Whitman Candy, in which a box

of candy and a small leatherbound book were wedded into one

package. These classic works, which he called the Little Leather

Library, eventually sold over thirty million copies.

Scherman’s ultimate goal was to create an effective means of

large-scale book distribution through mail order. The success of

direct-mail marketing had already been proven in other industries by

the 1920s, but no one had figured out how to successfully market

books in this fashion. The difficulty was in applying a blanket

marketing approach to a group of unique titles with different topics

and different audiences. Scherman’s solution was to promote the idea

of the ‘‘new book’’ as a commodity that was worthy of ownership

solely because of its newness. His approach focused attention on

consumers owning and benefiting from these new objects, rather than

on the unique qualities of the objects themselves. In 1926, Scherman’s

idea came to fruition, and with an initial investment of forty thousand

dollars by Scherman and his two partners, the Book-of-the-Month

Club was born.

Two elements in his design of the early Book-of-the-Month

Club were key to its lasting success. First, an editorial panel would

carefully select each new book that would be presented to the club’s

members. Scherman selected five editors to serve on the first panel:

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Harry Canby (editor of The Saturday

Review), William Allen White, Heywood Broun, and Christopher

Morley. Each was known and respected as a writer or journalist,

which helped reinforce the recognition of BOMC as a brand name.

These literary authorities would save the reader time by recommend-

ing which new book to buy. Readers were assured that their selections

were ‘‘the best new books published each month’’ and that they

would stand the test of time and eventually become classics.

The second vital element to the success of BOMC was the

institution of the subscription model, by which subscribers would

commit to purchasing a number of books over a period of time. Each

month, subscribers to the club would receive BOMC’s newest selec-

tion in the mail. Later, BOMC modified this approach so that

subscribers could exercise their ‘‘negative option’’ and decline the

selection of the month in favor of a title from a list of alternates. The

automatic approach to purchasing new books allowed BOMC to rely

on future book sales before the titles themselves were even an-

nounced. Scherman targeted the desire of the club’s middle-class

subscribers to stay current and was able to successfully convince the

public that owning the newest and best objects of cultural production

was the most expedient way to accomplish this goal.

BOMC posed an immediate challenge to the insularity of

bourgeois culture by presenting a shortcut method for achieving

literary knowledge. Janice Radway remarked that the club’s critics

‘‘traditionally suggested that it either inspired consumers to purchase

the mere signs of taste or prompted them to buy a specious imitation

of true culture.’’ Skeptics were wary of the transformation of books

into a commodity that would be purchased for the sake of its novelty.

They were not wrongly suspicious; as Radway explained, BOMC

‘‘promised not simply to treat cultural objects as commodities, but

even more significantly, it promised to foster a more widespread

ability among the population to treat culture itself as a recognizable,

highly liquid currency.’’ The market forces that drive the publishing

world were laid bare in the direct mail model, and it posed a clear

threat to the idea that literature should be published because it is good,

not because it appeals to the tastes of the ‘‘general public.’’

Behind that very real concern, however, was a discomfort with

the populist approach taken by BOMC. The company’s mission was

to popularize and sell the book, an object which had previously been

considered the domain of society’s elite. Middlebrow culture, as it

came to be known, developed in opposition to the exclusive academic

realm of literary criticism, and it threatened the dominant cultural

position of that group. At the other end of the spectrum, middlebrow

taste also excluded anything avant-garde or experimental. This cen-

trist orientation continued to make producers of culture uneasy

throughout the twentieth century, because it reinforced the exclu-

sion of alternative movements from the mainstream. This main-

stream readership, however timid and predictable its taste might be,

was a formidable economic group with great influence in the

book marketplace.