Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BRADY BUNCHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

339

Jaspersohn, William. Senator: A Profile of Bill Bradley in the U.S.

Senate. San Diego, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1992.

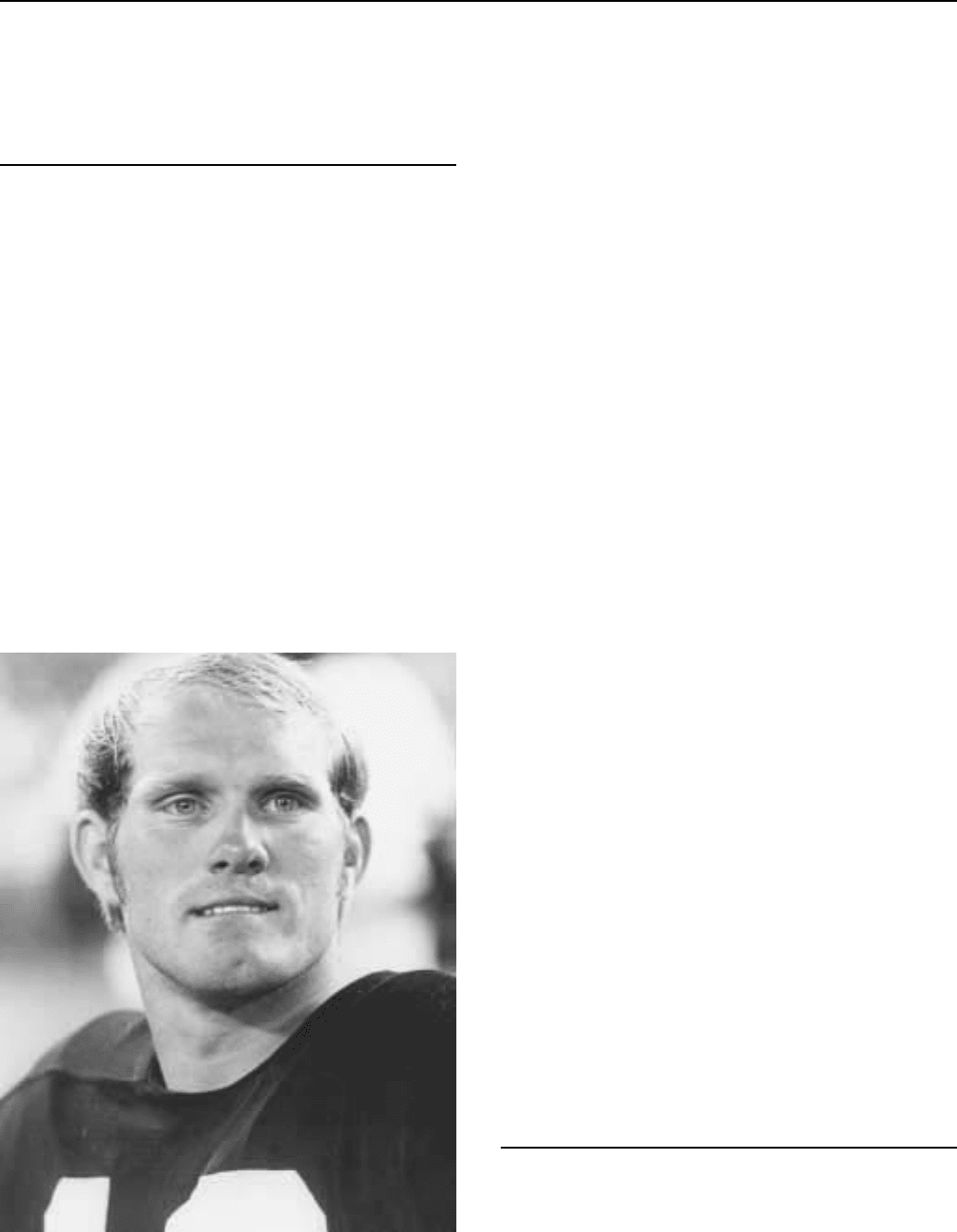

Bradshaw, Terry (1948—)

A country-bred, southern farm boy with a strong passing arm,

Terry Bradshaw used the principles of discipline and hard work that

he learned as a child to become one of the greatest quarterbacks the

game of football has ever seen. His career statistics still stand as a

substantial lifetime achievement for any player: two Super Bowl

MVPs, 27,989 yards gained, 212 touchdowns passed, and 32 touch-

downs rushed in his fourteen-year National Football League career.

Though his football fame ensured him a shot at a career as a sports

commentator, it is Bradshaw’s down-to-earth, unpretentious style

that continues to endear him to his audience.

Bradshaw was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, and raised in a

farming family. ‘‘I was born to work, taught to work, love to work,’’

he said. Even on the football field, he performed his job faultlessly,

developing the pinpoint accurate passing that would become his

trademark. He attended college at Louisiana Technical University,

where he made All-American, an unusual honor since Louisiana Tech

was not a Division I team. In 1970, quarterback Bradshaw was the

first player selected in the professional football draft.

For the next twelve years the Louisiana boy with the perfect

spiral pass led the Pittsburgh Steelers to victory after victory, includ-

ing four Super Bowl championships. The Steelers were the first team

Terry Bradshaw

to win four Super Bowls, and, in 1979 and 1980, Bradshaw was only

the second player ever to win recognition as Most Valuable Player in

two back-to-back Super Bowls. Bradshaw was the unanimous choice

for the MVP honor in Super Bowls XIII and XIV, a phenomenon that

had not occurred since Bart Starr won back-to-back MVP honors in

Super Bowls I and II.

By 1982, Bradshaw’s amazing passing arm was beginning to

show signs of damage. He toughed it out, playing in pain through

much of the 1982 season, but the doctors’ diagnosis was chronic

muscle deterioration, and the prescription was surgery. In March of

1983, Bradshaw underwent the surgery, but he could not withstand

pressure from Steelers coach Chuck Noll to return to the game. He

resumed playing too soon, causing permanent damage to his elbow.

Bradshaw played only a few games in the 1983 season, then was

forced to retire.

Though regretting that his retirement from the playing field had

not been on his own terms, Bradshaw continued to make football his

career. In 1989, he was inducted into the Football Hall of Fame, and

the next year he went to work for CBS as co-anchor of NFL Today. He

worked for CBS for four years, then the FOX network doubled his

salary and hired him as a game-day commentator and host of FOX

NFL. FOX also made surprising use of Bradshaw’s homespun talents

by giving him a daytime talk show. Home Team with Terry Bradshaw

was described by one executive as ‘‘Martha Stewart meets Monday

Night Football.’’ Pundits wondered how the rugged football veteran

would handle the traditionally female forum of daytime talk, but

Bradshaw’s easygoing style seemed to take it all in stride. In fact, it is

Bradshaw’s unapologetic country-boy persona that seems to appeal to

fans. Though critics have called his commentary incompetent and

even buffoonish, Bradshaw’s ‘‘just folks’’ approach continues to

make him popular. His response to critics has been typically disarm-

ing, ‘‘I stutter, I stammer, I scratch, and I do it all on live television . . .

I can’t help it. It’s me. What are you going to do about it? You can’t

change who you are.’’

Bradshaw has appeared in many movies, often alongside fellow

ex-football star Burt Reynolds, and has ambitions to have his own

television situation comedy. A Christian who found his religion while

watching Monday Night Football, he has released two successful

gospel albums. However, he has never become part of the entertain-

ment establishment, and he is happiest at home on his Texas cattle

ranch, working hard.

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Benagh, Jim. Terry Bradshaw: Superarm of Pro Football. New York,

Putnam, 1976.

Bradshaw, Terry. Looking Deep. Chicago, Contemporary Books, 1989.

Frankl, Ron. Terry Bradshaw. New York, Chelsea House, 1995.

The Brady Bunch

The Brady Bunch was one of the last domestic situation come-

dies which populated television during the 1950s and 1960s. While it

flew below Nielsen radar in its original run, its popularity in syndica-

tion led to frequent reincarnations through the 1990s. Generation X

viewers treated the series with a combination of irony and reverence.

BRADY BUNCH ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

340

The cast of The Brady Bunch.

In 1966, Gilligan’s Island executive producer Sherwood Schwartz

read a newspaper item stating that 30 percent of American families

were stepfamilies—where one or both parents were bringing into a

second marriage children from a first marriage ended by death or

divorce. Schwartz quickly realized that while TV sitcoms either

featured traditional, two-parent families (Make Room for Daddy,

Leave it to Beaver) or families headed by a widow or widower (The

Ghost and Mrs. Muir, My Three Sons), no comedy had yet focused on

a merging of two families. He spent the next three years developing a

series based on this premise. By the time The Brady Bunch debuted in

the fall of 1969, Hollywood had explored the subject with two box-

office hits, With Six You Get Eggroll and Yours, Mine, and Ours

(Schwartz planned to call his sitcom Yours and Mine).

The simple theme song laid out the storyline: Mike Brady

(played by Robert Reed), a widower architect with three sons—Greg,

Peter, and Bobby—met and wed Carol (Florence Henderson), a single

mother with three blonde daughters—Marcia, Jan, and Cindy. The

series never explained what happened to Carol’s first husband;

Schwartz intended Carol to be TV’s first divorcee with children. The

blended family moved into a giant house designed by Mike in the Los

Angeles suburbs, complete with a practical and seemingly tireless

maid, Alice (Ann B. Davis).

Most of the plots dealt with the six Brady children and the

travails of growing up. Schwartz has said the series ‘‘dealt with real

emotional problems—the difficulty of being the middle girl, a boy

being too short when he wants to be taller, going to the prom with zits

on your face.’’ Frequently the storylines centered around one of the

children developing an inflated ego after receiving a compliment or

award; Greg becoming a baseball maven after being coached by Hall

of Fame pitcher Don Drysdale, or Cindy turning into an arrogant snob

upon being chosen for a TV quiz show. Invariably public or private

humiliation followed and, with the loving support of parents and

siblings, the prodigal child was inevitably welcomed back into the

Brady fold. In contrast to the ‘‘real’’ problems dealt with on the show,

The Brady Bunch explored more fantastic stories on location several

times, including vacations to the Grand Canyon (where the family

was taken prisoner by a demented prospector) and, more famous-

ly, to Hawaii (where the Brady sons were taken prisoner by a

demented archaeologist).

The series never cracked the Top 25 ratings during its initial run,

but was enormously popular with the 17-and-under age group. The

BRADY BUNCHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

341

child actors were prominently featured in teen magazines of the early

1970s, and even formed a pop music group in the style of such TV-

inspired groups as The Monkees and The Partridge Family. Barry

Williams, who played eldest son Greg, received upwards of 6,500 fan

letters a week. There was also a Saturday morning cartoon spun off

from the show, The Brady Kids.

The show was cancelled in 1974, and that fall entered syndica-

tion, generally airing during the late afternoons. In this child-friendly

time period, The Brady Bunch became a runaway syndicated hit. In

1977, the cast (minus Eve Plumb, the original Jan) reunited on ABC

for The Brady Bunch Variety Hour, a bizarre hour-long series

featuring inane skits and production numbers; most of the cast could

not even dance in step. It was cancelled after several months and is

often considered the worst variety show in television history.

The original series’ popularity in reruns spurred more reunions,

however. The Brady Girls Get Married was a 1980 NBC special

where Marcia and Jan find husbands. The special led to another short-

lived sitcom, The Brady Brides, with the two newlywed couples

sharing living quarters (in typical sitcom fashion, one husband was an

uptight academic, while the other was a laid-back toy salesman).

The biggest Brady-related TV event came in December 1988,

with the broadcast of the TV movie A Very Brady Christmas. The six

children (most with spouses, significant others and children in tow)

congregated at the Brady manse to celebrate the holidays. While

working at a construction site, Mike was trapped under debris after an

accident. Carol and the extended family sang Christmas carols as he

was rescued; ironically enough, the location of this Christmas miracle

was on 34th Street. It was the highest rated TV movie of the 1988-

1989 season, and launched yet another Brady series. The Bradys

(CBS, 1990) was an hour-long drama attempting to bring serious

problems to the Brady landscape. In the series debut, Bobby, now a

racecar driver, was paralyzed in a NASCAR accident. Jan and her

husband tried in vain to conceive a child. Mike ran for Los Angeles

City Council, and stood accused of taking bribes. Marcia became an

alcoholic. The series lasted only half a season.

But the original series continues to fascinate. During the early

1990s, theater groups in New York and Chicago staged The Real Life

Brady Bunch, reenacting complete episodes of the series, on occasion

using actual Brady Bunch actors in cameo roles.

The series was something of a touchstone to people born during

the 1960s and 1970s, many of whom grew up in single-family

households or who, like the children in the series, became part of a

stepfamily. ‘‘The Brady Bunch, the way I look at it,’’ Schwartz said in

1993, ‘‘became an extended family to those kids.’’ Brady Bunch fans

developed the singular ability to identify a given episode after only

the first line of that episode’s dialogue. The 1970s dialogue (‘‘Groovy!’’

‘‘Far out!’’) and outrageously colored polyester clothes inspired

laughs from 1980s and 1990s audiences. Many of the curious produc-

tion elements (Why would an accomplished architect such as Mike

Brady build a home for six teenagers with only one bathroom? And

why didn’t that bathroom have a toilet? Why was the backyard lawn

merely carpeting? Why didn’t any of the windows in the house have

panes?) were cause for late-night debate in college dorms and coffee

shops. Letter to the Next Generation, Jim Klein’s 1990 documentary

on apathetic college students, had a montage of disparate cliques of

Kent State University students singing the complete Brady Bunch

theme song.

In the spring of 1992 Barry Williams’s Growing Up Brady was

published, a hilarious bestseller recounting the history of the series

and reflecting on what being a ‘‘Brady’’ meant. Williams shared

inside gossip:

Reed, a classically-trained actor and veteran of the

acclaimed TV drama The Defenders (1961-1965), regu-

larly sent sarcastic notes to Schwartz and the production

staff attacking the simplistic storylines and character

development. Had the series continued for a sixth sea-

son, Schwartz was willing to kill off Mike Brady and

have the series revolve around the six kids fixing up the

newly single Carol.

The 15-year-old Williams went on a chaste date

with the married Henderson. Williams also stated that

he dated ‘‘Marcia,’’ and that ‘‘Peter’’ and ‘‘Jan,’’ and

‘‘Bobby’’ and ‘‘Cindy’’ had similar relationships dur-

ing the show’s run.

Williams admitted that he filmed part of one 1972

episode (‘‘Law and Disorder’’) while under the influ-

ence of marijuana.

Shortly after Williams’s book was published, Robert Reed died

of colon cancer at age 59. It was subsequently announced that Reed’s

cancer was caused due to the AIDS virus. The revelation that Reed,

the head of TV’s most self-consciously wholesome family, had a

hidden homosexual life was as stunning to Generation X viewers as

news of Rock Hudson’s homosexuality had been to many of

their parents.

In the tradition of Star Trek and The Beverly Hillbillies, The

Brady Bunch became fodder for a full-length motion picture. To the

surprise of many, The Brady Bunch Movie (1995) was a critical and

box-office smash. The film wisely took a tongue-in-cheek approach

to the material, planting the defiantly-1970s Brady family smack dab

in the middle of 1990s urban Los Angeles. ‘‘Hey there, groovy

chicks!’’ the fringe-wearing Greg courted grunge classmates. There

were numerous references to Brady Bunch episodes, and cameos

from Williams, Henderson, and Ann B. Davis. A Very Brady Sequel

(1996) continued the approach to equal acclaim.

Schwartz came to comedy writing after receiving an master’s

degree in biochemistry, and began as a writer for Bob Hope prior to

World War II. He won an Emmy as a writer for The Red Skelton Show

in 1961. The knack for creating popular entertainment clearly runs in

the family—brother Elroy wrote for The Addams Family and My

Three Sons, son Lloyd co-produced The Brady Bunch, and two of his

nephews created the international hit TV series Baywatch.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Bellafante, Ginia. ‘‘The Inventor of Bad TV,’’ Time, March 13,

1995, 111.

Hillard, Gloria, ‘‘Brady Bunch Still Draws Crowds,’’ segment on

CNN’s ‘‘Showbiz Today’’ series, April 20, 1993.

Moran, Elizabeth. Bradymania! Everything You Always Wanted to

Know—And a Few Things You Probably Didn’t (25th Anniversa-

ry Edition). New York, Adams, 1994.

Owen, Rob. Gen X TV: The Brady Bunch to Melrose Place. Syracuse,

Syracuse University Press, 1997.

Williams, Barry. Growing Up Brady: I Was A Teenage Greg. New

York, Harper Perennial. 1992.

BRAND ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

342

Branch Davidians, The

See Koresh, David, and the Branch Davidians

Brand, Max (1892-1944)

Pulp novelist Max Brand earned millions of dollars from his

writing. Like many pulp writers, however, he did not feel that his

work was worth very much. Brand wrote over 300 novels in genres

such as detective fiction, spy stories, medicine, and fantasy. But he is

primarily known for westerns such as The Bells of San Carlos, The

Bells of San Filipo, Bull Hunter, and Donnegan. Clearly able to

diversify his talents, Brand also achieved great fame and fortune

through his Hollywood film writing. His Destry Rides Again inspired

numerous imitators, including television’s Maverick.

Brand, born Frederick Faust, was orphaned at an early age and

raised in poverty, but grew up with high literary ambitions. Despite

being known as a great western writer, Brand preferred to live in an

Italian villa. He spent his time there writing pulp fiction in the

morning and serious poetry in the afternoon. He was well read in the

classics and often used themes from them in his western tales, for

example he used the Iliad in Hired Gun. Without question the King of

the Pulps, Brand averaged about one million words a year. Outside of

his westerns, Dr. Kildare was his most famous creation. His readers

were intensely loyal and reached into the millions. Although he

preferred that his personal life remain mysterious, he did occasionally

offer fans glimpses of himself in autobiographical short stories. In A

Special Occasion, for example, one of the main characters shares

many similarities with Brand—his marriage is on the rocks, he has a

mistress who is a clinging vine, he longs for a better profession, and

sometimes drinks to excess.

—Frank A. Salamone, Ph.D.

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘The Ghost Wagon and Other Great Western Adventures.’’ Publish-

ers Weekly. February 12, 1996, 60.

Lukowsky, Wes. ‘‘The Collected Stories of Max Brand.’’ Booklist.

August 1994, 2020-2021.

Nolan, William F., editor. Western Giant: The Life and Times of

Frederick Schiller Faust. 1985.

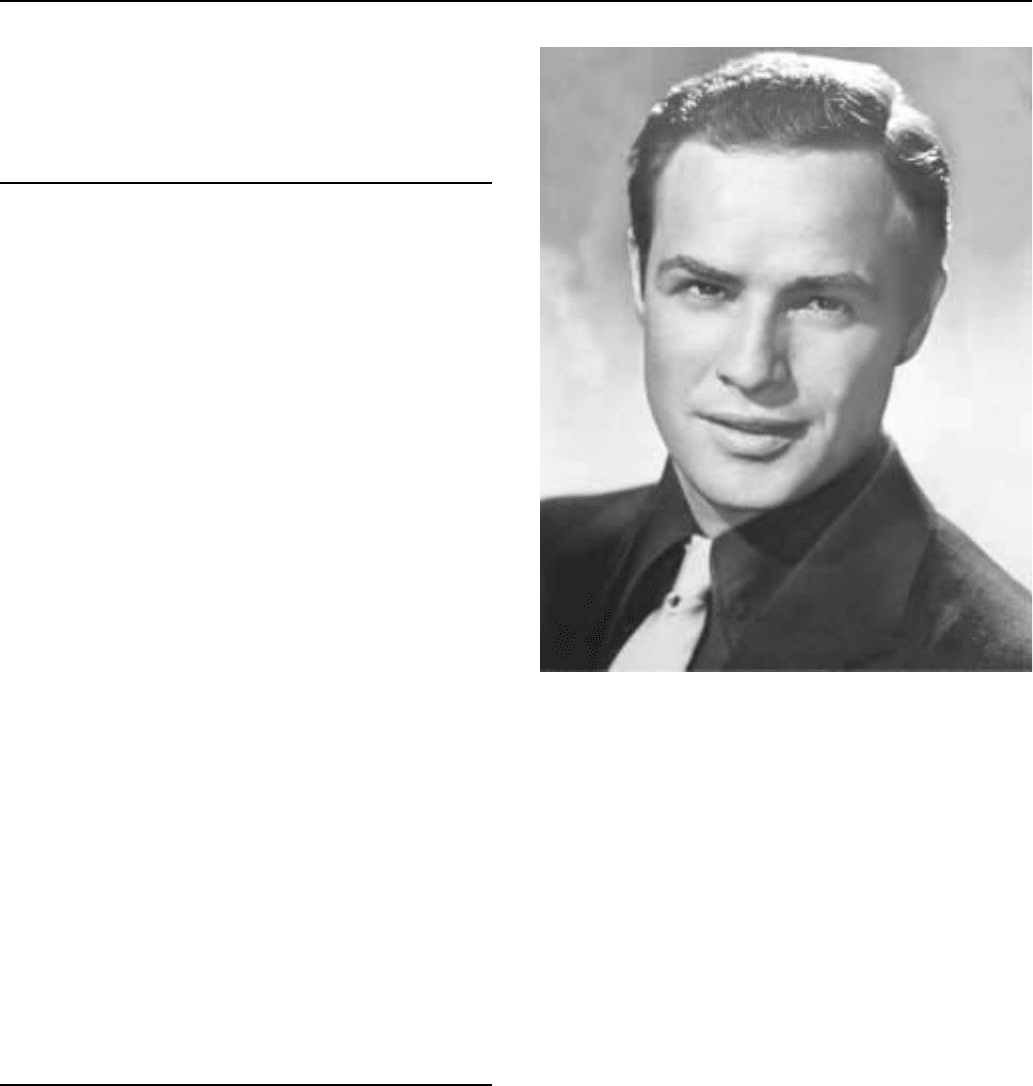

Brando, Marlon (1924—)

Marlon Brando remains unchallenged as the most important

actor in modern American Cinema, if not the greatest of all time.

Though a number of mainstream critics were initially put off by his

slouching, brooding ‘‘method’’ style, he was nominated for an

Academy Award in only his second film, A Streetcar Named Desire

(1951), and went on to repeat the accomplishment with each of his

next three performances: Viva Zapata (1952), Julius Caesar (1953),

and On The Waterfront (1954), with the latter performance finally

resulting in the Oscar for best actor.

Handsome enough to be a leading man and gifted enough to lose

himself in his characters, Brando brought an animalistic sensuality

and rebelliousness to his portrayals unseen in Hollywood before. Not

Marlon Brando

content with simply learning his lines and playing the character as

written or directed, the actor became the author of his portrayals. He

maintained the view throughout his life that actors cannot achieve

greatness without holding a point of view about society, politics, and

personal ethics. This has been reflected both in the characters that he

has chosen to play (rebels on the fringes of society) and in the

shadings that he has brought to them (ethical conflicts about living

within or outside the law).

This philosophy was initially ingrained in Brando through his

stint at New York’s Actor’s Studio where he studied with Elia Kazan

and Stella Adler, who taught him ‘‘The Stanislavsky Method,’’ a style

of acting in which the performer internalizes the character he is

playing to literally become one with his subject. This was considered

a major revision of classic acting styles during the 1950s. Before The

Actor’s Studio, performers externalized their characters, merely

adopting the physical features and gestures conducive to portraying

them. Up-and-coming actors including Brando, Paul Newman, and

James Dean shocked traditional actors and theater critics with the new

style, but there was no argument that it was effective, as Brando was

selected Broadway’s most promising actor for his role in Truckline

Café (1946).

As early as his first motion picture acting stint in Fred Zinneman’s

war film The Men (1950), Brando prepared for his part as a wheel

chair-bound veteran by spending a month in a hospital viewing first

hand the treatment and experiences of paraplegics. Based on his

observations, he played his character as an embittered social reject

straining against the restraints of his daily existence. From this point

on, his performances came to symbolize the frustrations of a post war

BRANDOENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

343

generation of Americans trying to come to terms with a society that

had forgotten them.

His subsequent characters, including Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar

and Terry Molloy in On the Waterfront, to cite two, were literally

drawn from the ash heap of society. Brando’s interpretation of the two

men’s speech patterns—though decried by critics as mumbling—

actually conveyed a hint of innate if not animalistic intelligence as

well as a suppressed power which threatened to erupt in violence. The

force of this power is best seen in The Wild One, in which Brando

plays Johnny, the rebellious leader of an outlaw motorcycle gang that

takes over a small town in Northern California. Based on an actual

1947 incident in which a gang vandalized the town of Hollister,

California, over the Fourth of July weekend, the story was the perfect

vehicle for Brando to display his menacing, barely-controlled rage.

When Brando is asked what he is rebelling against, he responds with

the now famous, ‘‘What have you got?’’

His rage seems more compelling when played against the overt

violence of the other bikers because he appears to be so angry that he

can’t find the words. The audience dreads what will happen when he

finally lets go. The interesting thing about the characterization is the

fine line that Brando is walking. He is at once the protagonist of the

film and, at the same time, potentially the villain, reminiscent of

Humphrey Bogart’s ambivalent Duke Mantee in The Petrified Forest

(1936). As long as the violence bubbles beneath the surface, it is

possible for the Brando character to be both sympathetic and menac-

ing at the same time, as was Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar and the

young Nazi officer in The Young Lions (1958).

Brando’s interpretation marked a turning point in American

films and effectively launched the era of the ‘‘rebel.’’ Following the

film’s 1954 release, a succession of young outlaws appeared on the

screen: James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955); Elvis Presley in

Jailhouse Rock (1957) and a string of low budget biker films. Even

Peter Fonda’s hippie rebel character in 1969’s Easy Rider and Charlie

Sheen’s rebel pitcher in 1989’s Major League can trace their roots

back to Brando’s performance.

In his more finely modulated performances, the violence is

translated into a brooding passion that is inner directed and reflects

his characters’ disillusionment with having whatever idealism and

ideological purity they began with tempered by a reality that they are

powerless to control. This is the Brando of Viva Zapata, The Godfa-

ther (1972), Last Tango in Paris (1972), and Quemada! (1969). In the

first three, he is a man living outside the system who is battling in his

own way to preserve his manhood and to keep from being ground

beneath mainstream society’s rules. In the final film, he is a man who

has lost whatever idealism and freedom he once maintained and has

learned that in order to survive he must not only play by but enforce

the rules even though he is unhappy doing so.

In Zapata, Brando confronts the dilemma of an individual torn

between spontaneous rebellion against injustice versus a full scale

revolution to promulgate an abstract ideal. His Zapata is a contradic-

tory character; on one hand full of zeal to right the wrongs that the

government has done to the people and fighting for agrarian land

reform; on the other, ill at ease with the larger issues of social reform

and the institution of a new system of government. The character’s

inner naiveté is revealed in one particularly sensitive scene preceding

Zapata’s meeting with President Madero in which he confides to his

new bride that he is ill at ease because he does not know how to read.

The two sit on the edge of the bed and she begins to teach him in one of

the most emotional moments in the film. This scene is reminiscent of

Johnny’s attempt at making love to Kathie in The Wild One in which

he displays a conflicted vulnerability and allows the woman to

take charge.

This fundamental contradiction in Brando’s characters is evi-

dent in his depiction of Don Corleone in The Godfather, in which he

presents a Mafia chieftain who is comfortable killing men who

oppose him and yet can express the deepest tenderness toward the

downtrodden and those that he loves. Corleone is no less of a rebel

than Zapata. Living on the outskirts of a system that he routinely

circumvents for profit and, in a strange way, to achieve justice for the

lower echelons of society, he is still, at heart, a rebel. Brando carries

this portrayal a step farther in Last Tango in Paris when his depiction

of Paul not only reveals a man’s internal conflicts but actually

questions the idea of animal masculinity that typified his characters in

the 1950s.

Yet, between his dominant performances in the 1950s and what

many consider to be his re-emergence in 1972, his career was

sidetracked, in the opinion of many critics, by some dubious roles

during the 1960’s. Such films as One Eyed Jacks (1961), Mutiny on

the Bounty (1962), The Ugly American (1962), The Chase (1966),

Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), and A Countess from Hong Kong

(1967), however, still indicate his concern for social injustice and

display his characteristic shaping of his characters to reveal the basic

conflicts inside all men.

In what a number of film scholars consider to be Brando’s real

renaissance, 1969’s Quemada! (Burn), directed by Italy’s revolution-

ary filmmaker Gilo Pontecorvo, he gave what may arguably be his

finest performance as a conflicted anti-revolutionary. In his previous

film, Battle of Algiers (1965), Pontecorvo established a film tanta-

mount to a textbook both for initiating and defeating terrorism. But in

Burn, through the character of British Governor Sir William, Pontecorvo

establishes the premise and the practice for effecting a revolution and

at the same time shows why it could never succeed. Brando’s

performance as a man who, as a youth, shared the idealism and

concepts of social freedom promulgated by the revolutionaries, but

who now knows why such movements must necessarily fail, is a tour

de force. He comes across as a man who is still a rebel but who is also

aware of the path of military history. Emotionally he is storming the

barricades but intellectually he knows what the inevitable outcome

will be. On the latter level, his manner reflects the attitude of his

earlier character, Major Penderton (in Reflections), but on the former

level he is the emotional voice crying out to the deaf ears of

imperialists as in 1963’s The Ugly American.

Brando’s social sympathies can be seen in his own life as well.

For example he had an American Indian woman pick up his second

Oscar for the Godfather and make some remarks about the treatment

of native Americans in the United States. He lives outside of the

Hollywood milieu, sometimes in the South Pacific working on

environmental concerns, other times in the San Fernando Valley. He

works only infrequently and expresses a disdain for the type of

material currently being produced in Hollywood, although he does

emerge every so often for outrageous sums of money if a role that

interests him presents itself. He usually imbues these characters with

qualities and social concerns that were not in the original scripts and

tends to play them a bit ‘‘over the top’’ (see Superman [1978] and

Apocalypse Now [1979]). Yet, he is also not above poking fun at

himself as he did in 1990’s The Freshman, in which he reprised his

Don Corleone role, albeit in a satirical manner.

Marlon Brando is one of the few actors of his generation whose

entire body of work—both good performances and those of lesser

BRAT PACK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

344

impact—reflect his social concerns, his celebration of the downtrod-

den, and his examination of the nature of man and the exercise of

power. In this respect, he is a true auteur in every sense of the word,

shading all of his portrayals with the contradictions inherent in the

individual and in society itself. As Mark Kram stated in a November,

1989, Esquire article: ‘‘there are people who, when they cease to

shock us, cease to interest us. Brando no longer shocks, yet, he

continues to be of perennial interest, some of it because of what he did

on film, some of it because he resists definition, and maybe mostly

because he rejects, by his style of living and his attitudes, much of

what we are about as a nation and people. He seems to have glided

into the realm of folk mystery, the kind that fires attempts at solution.’’

—Steve Hanson

F

URTHER READING:

Braithwaite, Bruce. The Films of Marlon Brando. St. Paul, Minneso-

ta, Greenhaven Press, 1978.

Brando, Anna Kashfi. Brando for Breakfast. New York, Crown, 1979.

Brando, Marlon. Songs My Mother Taught Me. New York, Random

House, 1994.

Carey, Gary. Marlon Brando: The Only Contender. New York, St.

Martin’s Press, 1986.

Frank, Alan G. Marlon Brando. New York, Exeter Books, 1982.

Grobel, Lawrence. Conversations with Brando. New York,

Hyperion, 1991.

Higham, Charles. Brando: The Unauthorized Biography. New York,

New American Library, 1987.

Kram, Mark. ‘‘American Originals: Brando.’’ Esquire. November

1989, 157-160.

McCann, Graham. Rebel Males: Clift, Brando, and Dean. New

Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 1993.

Schickel, Richard. Brando: A Life in Our Times. New York,

Atheneum, 1991.

Schirmer, Lothar. Marlon Brando: Portraits and Stills 1946-1995

with an Essay by Truman Capote. New York, Stewart, Tabori and

Chang, 1996.

Shipman, David. Brando. London, Macmillan, 1974.

Webster, Andy. ‘‘Marlon Brando.’’ Premiere. October 1994, 140.

Brat Pack

A term that describes a bunch of young upstarts in any industry,

the Brat Pack was first used in the 1980s to refer to a group of actors

that included Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, Andrew

McCarthy, Emilio Estevez, Anthony Michael Hall, and Rob Lowe.

Honorary Brat Pack members were Demi Moore, Kiefer Sutherland,

Mare Winningham, Charlie Sheen, John Cryer, Christian Slater,

Robert Downey, Jr., James Spader, John Cusack, Eric Stoltz, Matt

Dillon, C. Thomas Howell, and Matthew Broderick. The name is a

play on the Rat Pack, a term used for the 1960s Vegas clique of Frank

Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peter Lawford, and

Joey Bishop.

The den mother of the Brat Pack was writer/director John

Hughes, who changed the teen film genre forever. Not content to

leave the celluloid teenage experience at lookin’-to-get-laid come-

dies, Hughes explored the premise that high school life could be

serious and harrowing, and that teenagers were not just a bundle of

walking hormones. It was no accident that this became his oeuvre in

the 1980s, a decade classified by obsession with money and status.

Parents in Hughes’ films were often portrayed as well-off but absent,

too busy working to notice what was really going on with their kids,

who had to learn the important lessons on their own. In Hughes’s

films, as in Steven Spielberg’s, adults were almost always the bad

guys. White, middle-class teenage angst, set mostly in the suburbs

surrounding Chicago, became the vehicle through which Hughes

chastised the confusing values of this superficial decade. And he used

a company of young actors, most notably the crimson-tressed Ringwald,

to explore this angst.

Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Pretty in Pink was

Hughes’ Ringwald trilogy. In Sixteen Candles (1984), Samantha

(Ringwald) is pursued by a geek (Hall), lusts after a hunk (Dillon),

and worst of all, her whole family forgets her sixteenth birthday. The

slightly heavier Pretty in Pink is about Andie (Ringwald), a girl from

the wrong side of the tracks who falls for ‘‘richie’’ Blane (McCarthy).

Blane’s snotty friend Stef (Spader) tells him to stay away from Andie,

whom he calls a mutant. The rich and the poor are mutually preju-

diced against each other, and the poor are portrayed as the better

people. Andie’s oddball friend Duckie (Cryer), doesn’t want Andie

with Blane either, but that’s mostly because he’s in love with her.

Blane finally takes the risk and goes for Andie, after listening to his

snobby friends and their values for too long. The original script called

for Andie to end up with Duckie, but Hughes thought that such an

ending would send the message that the rich and the poor really don’t

belong together.

The Breakfast Club (1985) was the definitive Brat Pack movie; it

focused on the interactions of five high-school students who are stuck

in all-day Saturday detention. Each of the students represents a

different high school clique. The popular, stuck-up Claire (Ringwald),

the princess, and Andy (Estevez), the athlete, might hang out together,

but normally they wouldn’t associate with smart, nerdy Brian (Hall),

the brain, compulsive liar and weirdo Allison (Sheedy), the basket

case, and violent, sarcastic Bender (Nelson), the criminal. As the

movie unfolds, the students fight and they bond, leaving their

stereotypes behind and growing closer together. Face-value judg-

ments are rejected for truer understanding because the students take

the time to know each other, something they wouldn’t do in the high

school hallways. Hughes uses their interactions to explore the univer-

sal teen anthem ‘‘I’m not gonna be anything like my parents when I

grow up!’’ and to reject the superficial classifications that adults put

on teens.

What kind of adults will these angst-ridden teenagers grow into?

The answer could be found in a film that wasn’t from Hughes (the

director was Joel Schumacher), but could have been, St. Elmo’s Fire,

the story of an ensemble of overprivileged recent Georgetown Uni-

versity grads trying to adjust to life and disillusionment in the real

world. St. Elmo’s Fire featured Nelson, Sheedy, and Estevez (prob-

ably relieved to be playing closer to their ages) as well as McCarthy,

Moore, and Lowe.

For a while, Hollywood was on the lookout for any film

featuring an ensemble cast of pretty young men and women. Thus

moviegoers were treated to Three Musketeers, with Sutherland and

Sheen, and Young Guns, a western with Sutherland, Sheen, and

Estevez, among others. But real Brat Pack movies had to include that

honorary Brat Pack member, angst. When these actors approached the

BRAUTIGANENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

345

The Brat Pack as they appeared in the film St. Elmo’s Fire: (from left) Ally Sheedy, Judd Nelson, Emilio Estevez, Demi Moore, Rob Lowe, Mare

Winningham, and Andrew McCarthy.

age of thirty (in the early 1990s), the Brat Pack wore thin. None of the

principal Brats have been able to score as well separately as they did

as a youthful, angst-ridden ensemble.

—Karen Lurie

F

URTHER READING:

Brode, Douglas. The Films of the Eighties. New York, Carol Publish-

ing Group, 1990.

O’Toole, Lawrence. ‘‘Laugh Lines after School: The Breakfast

Club.’’ Maclean’s. February 18, 1985, 58.

Palmer, William. The Films of the Eighties: A Social History.

Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1993.

Brautigan, Richard (1935-1984)

Author of the widely popular novel Trout Fishing in America,

Richard Brautigan was a countercultural hero in the United States in

the 1960s. Although he never aligned himself with any group,

Brautigan, with his long hair, broad-brimmed hat, wire-rim glasses,

and hobnail boots, became a hippie icon comparable during his

generation to Jack Kerouac and John Lennon.

Brautigan was born on January 30, 1935, in Tacoma, Washing-

ton. He moved to San Francisco in the mid-1950s where he met Allen

Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti and became loosely associated

with the Beat poetry movement. In the 1960s, he wrote and published

his first three novels, which would be his most popular: A Confed-

erate General from Big Sur, Trout Fishingin America, and In

Watermelon Sugar.

Trout Fishing in America was by far the most enduring and

important of these. Published in 1967, it went through four printings

before being reissued as mass paperback by Dell and selling two

million copies. It was a favorite with college students, and Brautigan

developed a cult following. Written in short, self-contained chapters,

the book had almost nothing to do with trout fishing and was

deceptively easy to read. It was structured such that the reader could

open to any page and still enjoy and understand the diary-like

ruminations. Some said that Brautigan was to literature what the

Grateful Dead was to music—enjoyable while on dope.

Because of the youth of his fans and his status among the

counterculture, some critics suggested that Brautigan was a passing

fad. Like Kurt Vonnegut and Tom Robbins (who alludes to Trout

BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

346

Fishing in his first novel, Another Roadside Attraction), Brautigan

was a writer of his time, sometimes even a writer of his ‘‘instant.’’ He

was the quintessential 1960s writer, sometimes dismissed as dated

and insubstantial. To one reviewer, he was ‘‘the last gasp of the Beat

Generation,’’ but others believed him to be an authentic American

literary voice.

Between the 1960s and the early 1980s Brautigan produced ten

novels, eleven books of poetry, a book of short stories, and Please

Plant This Book, a set of poems sold with seed packets. Many of his

books played with and parodied mainstream genres, with jokey titles

including The Abortion: An Historical Romance, The Hawkline

Monster: A Gothic Western, and Dreaming of Babylon: A Private Eye

Novel. In his prose, his humor and childlike philosophies often

masked deeper themes of solitude and despair, and his poetry was

characterized by offbeat metaphors—comparisons of snow to wash-

ing machines, or sex to fried potatoes.

Brautigan was poet-in-residence at California Institute of Tech-

nology from 1966-67, but in the early 1970s, he left California for

Montana. There he led a hermit-like existence, refusing to give

interviews and generally avoiding the public for a decade. His later

novels were financial and critical failures, and he had a history of

drinking problems and depressions. In 1982, his last book, So the

Wind Won’t Blow It All Away, was published. Two years later, at the

age of forty-nine, Brautigan apparently committed suicide—he was

found in October of 1984 with a gunshot wound to the head.

His casual, innovative style was widely influential, prompting

one critic to say that in the future, authors would write ‘‘Brautigans’’

the way they currently wrote novels. Critics waited for the Brautigan

cult to fade, but it was still present at the end of the twentieth century.

A folk-rock band called Trout Fishing in America formed in 1979 and

was still active after twenty years, and a Brautigan-esque literary

journal, Kumquat Meringue, was founded in 1990 in Illinois and

dedicated to his memory.

—Jessy Randall

F

URTHER READING:

Boyer, Jay. Richard Brautigan. Boise, Idaho, Boise State Universi-

ty, 1987.

Chénetier, Marc. Richard Brautigan. New York, Methuen, 1983.

Foster, Edward Halsey. Richard Brautigan. Boston, Twayne Publish-

ers, 1983.

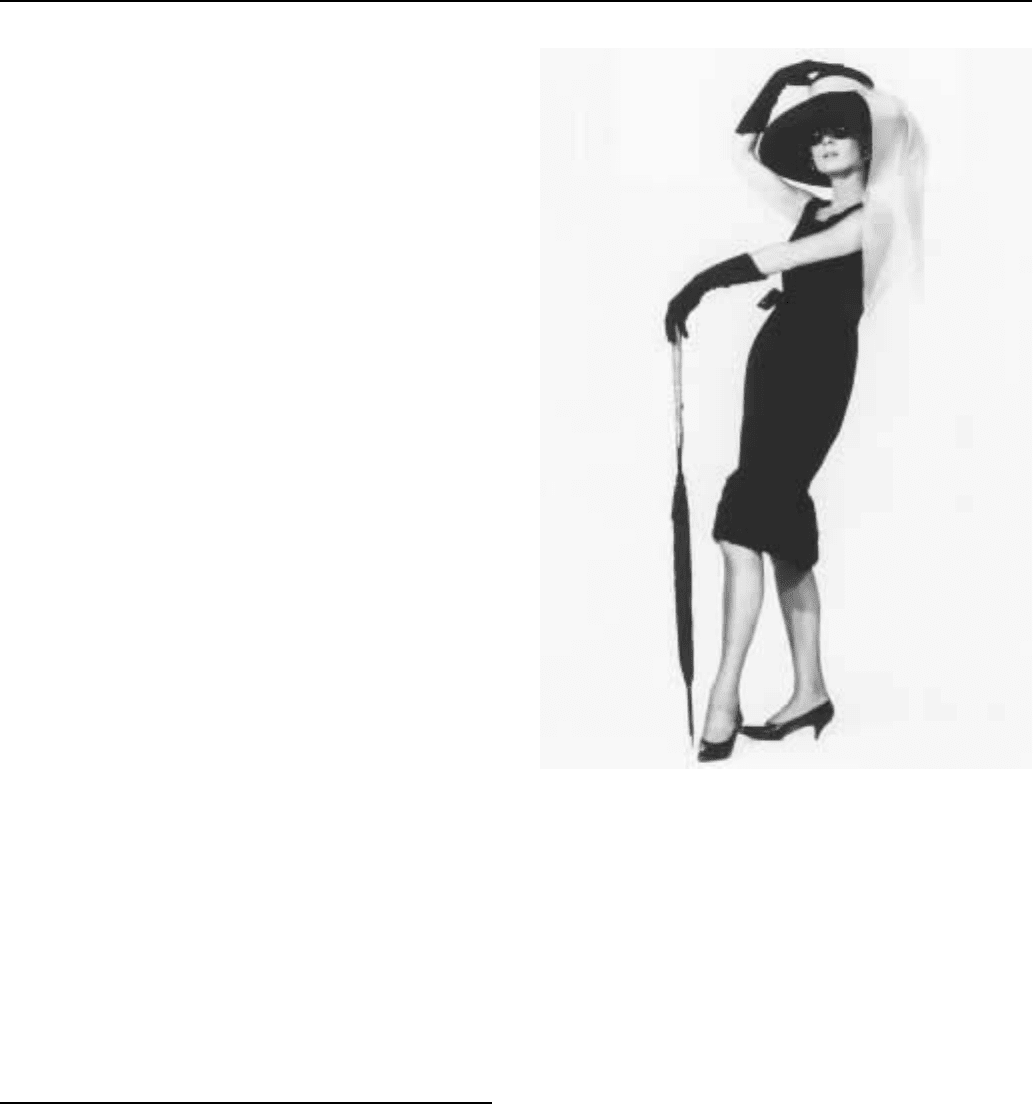

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Paramount Pictures’ release of Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961

solidified the cosmopolitan image of Audrey Hepburn and solidified

one of the most enduring fashion trends: the little black dress. The

movie was based closely on Truman Capote’s 1959 short novel by the

same name, which most critics called Capote’s best work.

The story adeptly portrays the glamorous romantic illusions of

Holly Golightly, a young woman travelling in search of a perfect

home. She is so driven by her quest that she refuses to name her cat

until she finds a home. But her inability to resolve the lingering issues

of her past keeps her from finding peace. Only while looking through

the window of Tiffany’s jewelry store does Holly feel a sense of calm.

Audrey Hepburn as she appeared in the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Most films about young women, in the early 1960s, portrayed

them as living under parental influences until they were married.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s broke that mold and showed Holly as a young

woman living on her own the best way she could, as an escort to men

she referred to as ‘‘rats.’’ While Capote imagined Marilyn Monroe as

the perfect actress for the part of Holly because her troubled past

closely reflected the turmoil in the life of his character, Paramount

Pictures instead cast Audrey Hepburn for the part and downplayed the

dark past of the character. In doing so, the film heightened the

dramatic importance of Holly’s past and allowed Hepburn to bring a

sense of mystery to her seemingly flighty character.

Audrey Hepburn’s acting was not alone in effecting the romantic

qualities of this film. Dressing Holly Golightly in sleeveless black

shifts, big black hats, and large black sunglasses, fashion designer

Givenchy made the little black dress—a standard cocktail dress since

the 1920s—an essential component of stylish women’s wardrobes.

And Audrey Hepburn inspired Henry Mancini to write the score to

‘‘Moon River,’’ the movie’s sentimental theme song. Johnny Mercer

wrote the lyrics, and the song won two Academy Awards. By the

1990s, Breakfast at Tiffany’s had long since been considered a classic

film and remained the film most associated with Audrey Hepburn’s

portrayal of a cosmopolitan and youthful romantic sensibility.

—Lisa Bergeron Duncan

BREAST IMPLANTSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

347

FURTHER READING:

Capote, Truman. Breakfast at Tiffany’s. New York, Vintage

Books 1986 ed.

Garson, Helen S. Truman Capote. New York, Fredrick Ungar Pub-

lishing, 1980.

The Breakfast Club

The Breakfast Club, director/script writer John Hughes’ 1985

film about five teenagers coping with the difficulty of crossing

boundaries and connecting in high school, set the tone for coming of

age films in the 1980s, and catapulted Hughes into the major

filmmaker chronicling the problems of a young America in the

Reagan years. While lacking in racial and sexual diversity, The

Breakfast Club tackled issues of self-image, drug use, sex, and social

acceptance, as well as the stratification between rich and poor. The

Breakfast Club also launched the 1980’s ‘‘brat pack’’ of marketable

actors, Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, Molly Ringwald, Judd Nelson,

and Anthony Michael Hall.

—Andrew Spieldenner

Breast Implants

Between one and two million women have breast implants.

Before 1992—when the controversy over possible side effects made

world headlines—about 150,000 women received implants annually,

and since 1994 about 70,000 women a year undergo implanta-

tion. About one-fifth of all implant operations are performed for

reconstructive purposes following mastectomies, with the remaining

80 percent for cosmetic purposes. The two most common types of

implants are silicone and saline, silicone being associated with the

greater number of health risks. Few objects are more emblematic of

the male obsession with the female breast and the sacrifices women

are willing to make in order to live up to the male ideal, with

thousands of women now suffering ill effects from having undergone

the operation. Some blame the mass media—and even the Barbie doll,

which if life-size would measure 40-18-32—for giving women a false

self-image. The popularity of implants has alternatively been reviled

for and praised for such phenomena as ‘‘Penthouse’’ magazine, the

Hooters restaurant chain, and the television show Baywatch, and has

spawned such backlash products as ‘‘Perfect 10’’ magazine (adver-

tised as bringing you ‘‘The world’s most naturally beautiful women,

NO IMPLANTS!’’) and the ‘‘Playboy’’ version, ‘‘Natural Beauties’’

(advertised as ‘‘a silicone-free zone!’’).

Derived from sand and quartz, silicone was developed in the

early 1940s, and its applications ranged from sealant and lubricant to

infant pacifiers and Silly Putty. Immediately after World War II,

Japanese cosmetologists began experimenting with ways to enlarge

the breasts of Japanese women, mainly prostitutes, because it was

known that the U.S. soldiers who were occupying the country

preferred women with breasts larger than those of most Japanese

women. The practice of injecting breasts with silicone was soon

exported to the United States and, by 1965, more than 75 plastic

surgeons in Los Angeles alone were injecting silicone. Topless

dancer Carol Doda placed the procedure in the national psyche when

she went from an average 36-inch-bust go-go dancer to a 44-inch-bust

superstar. But many of the 50,000 American women receiving these

injections were soon experiencing health problems, including at least

four deaths. In the mid-1960s, the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) defined silicone as a ‘‘drug,’’ so they could begin regulating

its use. But at the time, medical devices were not regulated by the

FDA, and Drs. Frank Gerow and Thomas Cronin came up with the

idea of encasing saline inside a silicone shell, with a Dow Corning

public relations representative convincing them that filling the bag

with silicone gel would more closely duplicate the feel of the female

breast. The doctors designed their first breast implant in 1961, they

surgically implanted it in 1962, and in 1963 Cronin introduced the

implant to the International Society of Plastic and Reconstructive

Surgeons (ISPRS), claiming that silicone was a totally inert sub-

stance. Cronin patented the device and assigned the rights to Dow

Corning, which launched its breast implant business that same year,

offering eight sizes, ranging from mini to large extra-fill. Over time,

improvements in breast implants evolved, along with psychological

justifications for their use; study after study claimed that breast

enhancement improved everything from self-esteem to marital bliss.

At one point, ISPRS proclaimed small breasts to be deformities that

are really a disease—‘micromastia’—‘‘which in most patients result

in feelings of inadequacy, lack of self-confidence, distortion of body

image and a total lack of well-being due to a lack of self-perceived

femininity.’’ By proclaiming small breasts to be a disease, there was

always the outside chance that insurers would start covering

the operation.

In the late 1970s, the medical literature started reporting serious

health complications from leaking and ruptured implants. In 1988, the

FDA reclassified implants as medical devices requiring the strictest

scrutiny, giving implant manufacturers 30 months to provide safety

data. Document discovery in a 1991 jury trial, Hopkins v. Dow

Corning Corp., produced reams of internal documents—including

some ‘‘smoking guns’’ implying that the manufacturers knew of and

concealed the health risks associated with their product. When the

private watchdog organization Public Citizen won a suit against Dow

Corning and the FDA for these and other documents, they became

available to plaintiffs’ attorneys across the country, and the litigious

floodgates opened, with thousands of suits being filed, including

several class action suits. In January 1992, FDA Chairman David

Kessler declared a moratorium on silicone-gel breast implants. By the

end of 1993, more than 12,000 women had filed suit, and by mid-

1998, about 136,000 claims had been filed in the United States against

Dow Corning alone. As the 1990s ended, breast implants remained

symbolic of male fantasies and distorted female self-image, but also

had come to symbolize the bias of supposedly objective scientific

results, with several manufacturer-financed scientific studies con-

cluding that silicone breast implants have no harmful effects.

—Bob Sullivan

F

URTHER READING:

Byrne, John A. Informed Consent. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Hopkins v. Dow Corning Corp., ND IL, No. 90-3240.

BRENDA STARR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

348

Sullivan, Bob. ‘‘FDA Advisory Panel Recommends Limited Access

to Implants.’’ Breast Implant Litigation Reporter. Vol. 1, No. 1,

March 1992.

Vasey, Frank B., and Josh Feldstein. The Silicone Breast Implant

Controversy. Freedom, California, The Crossing Press, 1993.

Zimmermann, Susan M. Silicone Survivors. Philadelphia, Temple

University Press, 1998.

Brenda Starr

Sixty years a journalist, red-haired Brenda Starr began her career

as a funny paper version of the pretty girl daredevil reporter who was a

staple of movies and radio over a half century ago. Created by a

woman named Dale Messick, Brenda Starr, Reporter made its first

appearance in 1940. It was a combination of newspaper melodrama

and frilly romance. There had been female reporters in the comic

sections before her, notably Jane Arden, but Brenda seemed to

epitomize the type and she managed to outlast all the competition.

The strip owes its existence in part to the Chicago Tribune’s

uneasiness about the phenomenal success of comic books. The advent

of Superman, Batman and then a host of other costumed heroes had

caused hundreds of adventure-based comic books to hit the news-

stands and, in many cases, to thrive. To offer its younger readers

something similar that would hopefully boost sales, the Trib created a

Chicago Tribune Comic Book that was tucked in with the Sunday

funnies as of the spring of 1940. On June 30, 1940 Messick’s strip was

added to the uncertain mix of reprints and new material. The only

feature to become a palpable success, it was eventually transferred to

the regular Trib lineup. Captain Joseph Medill Patterson, who headed

up the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate and was the

publisher of the News, disliked women cartoonists in general and

Brenda Starr in particular and the strip never ran in his paper until

after his death. He was not opposed, however, to his syndicate selling

to as many other newspapers as possible.

Feisty and pretty, Brenda covered all sorts of stories for her

paper and that put her in frequent danger from crooks, killers, and

conmen. But her job also introduced her to a succession of handsome,

attractive, though not always suitable, men. Most notable among

them was the mysterious Basil St. John, who wore an eye patch, raised

black orchids, and appeared frequently over the years until he and

Brenda finally were wed.

Brenda’s managing editor was a fellow named Livewright and

her closest friend on the paper was a somewhat masculine lady

reporter named Hank O’Hair. For her feminine readers Messick

included frequent paper dolls in the Sunday page. Messick apparently

also drew all the fashionable clothes her characters wore, but for the

action stuff and such props as guns, fast cars, and shadowy locales she

relied on assistants. John J. Olson worked with her for several decades.

Brenda had a limited merchandising life. The strip was reprinted

in Big Little Books as well as comic books, but there was little other

activity. She was first seen on the screen by the Saturday matinee

crowd. Columbia Pictures released a 13-chapter serial in 1945,

starring B-movie veteran Joan Woodbury as the daring reporter.

Roughly four decades later a movie was made with Brook Shields as

Brenda. The film, which Leonard Maltin has dubbed ‘‘a fiasco,’’ was

kept on the shelf for three years before being released. When Messick

was retired from the strip, Ramona Fraddon, who’d drawn such comic

book heroes as Aquaman, took over as artist. More recently June

Brigman assumed the drawing.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Goulart, Ron, editor. Encyclopedia of American Comics. New York,

Facts on File, 1990.

Brice, Fanny (1891-1951)

One of the funniest women of her (or any other) day, singer and

comedienne Fanny Brice starred in the Ziegfeld Follies for thirteen

years becoming, in the process, one of America’s most famous

women. Combining innate comic talent with a great singing voice,

Fanny was a vaudeville star when still a teenager. After signing with

Florenz Ziegfeld at nineteen, Brice performed in all but two of the

Ziegfeld Follies from 1910 to 1923. With her signature song, My Man,

Brice went on to star on Broadway; she also appeared in eight films.

But she was best known around the world as radio’s Baby Snooks.

Married to gambler Nick Arnstein and producer Billy Rose, Brice’s

life became the subject of the Broadway musical and 1968 film,

Funny Girl, and its 1975 sequel, Funny Lady, starring Barbra Streisand.

Her comic legacy—always a lady, Brice nonetheless shocked her

audiences with her raunchy humor—is carried on by such contempo-

rary comediennes as Joan Rivers and Bette Midler.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Grossman, Barbara W. Funny Woman: The Life and Times of Fanny

Brice. Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 1992.

Katkov, Norman. The Fabulous Fanny: The Story of Fanny Brice.

New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1953.

Brideshead Revisited

The lavish adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead

Revisited was fashioned by Granada Television and first aired on the

British channel, ITV, in 1981. Comprising 11 episodes of some 50

minutes each, it chronicles the relationship of a young man with the

aristocratic, English Marchmain family between the World Wars. The

adaptation proved popular on both sides of the Atlantic; it appeared in

the United States under the auspices of PBS in 1982 to great acclaim.

Praised for its production values and aura of quality, the series is

credited with ushering in a number of heritage England screen

representations that appeared during the 1980s. These heritage repre-

sentations include The Jewel in the Crown and A Room with a View.

Like Brideshead, they are distinguished by a nostalgic tone, elegant

costumes, and stately locations depicted via lush photography.

Brideshead and other heritage representations were challenged by

cultural critics in the 1990s as being conservative and retrograde.

—Neal Baker