Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BLAXPLOITATION FILMSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

279

William Foster released a series of all-black comedy films beginning

in 1910. Oscar Micheaux produced, wrote, and directed nearly forty

films between 1919 and 1948. Hundreds of ‘‘black only’’ theaters

existed in the United States from the 1920s to the 1950s, and there

were low-budget African American films of all genres: musicals,

westerns, comedies, horror films, and so forth. The market for these

black films started to disappear in the 1950s, when integration

brought an end to the ‘‘blacks only’’ theaters and Hollywood began

using African American performers more prominently in mainstream

studio productions.

By the end of the 1960s, it was common to see films starring

African American performers. When Sidney Poitier won the Acade-

my Award in 1964 for his role in Lilies of the Field, his victory was

seen as a sign of great progress for African American actors. Howev-

er, a more important role for Poitier was that of police detective Virgil

Tibbs in the film In the Heat of the Night. He played Tibbs in two

more films, They Call Me MISTER Tibbs and The Organization. Both

those movies were released at the beginning of the blaxploitation

cycle and clearly influenced many blaxploitation pictures: the force-

ful, articulate, handsome, and well-educated Virgil Tibbs appears to

have been the model for the protagonists of many blaxploitation

pictures. The success of In the Heat of the Night—it won the Oscar as

best picture of 1967—and the ongoing civil rights movement in

America led to more films that dealt with racial tensions, particularly

in small Southern towns, including If He Hollers, Let Him Go; tick . . .

tick . . . tick . . . ; and The Liberation of L.B. Jones. But all of these

movies were mainstream productions from major Hollywood studios;

none could be considered a blaxploitation picture.

The Red, White and Black, a low-budget, extremely violent

western with a predominantly African American cast can be called the

first blaxploitation film. Directed by John Bud Carlos and released in

1969, the movie was the first black western since the 1930s, address-

ing the discrimination faced by African Americans in post-Civil War

America. The most influential movie of this period, however, was

Sweet Sweetback’s Baaadassss Song, which was written, produced,

and directed by Melvin van Peebles, who also starred. The protago-

nist, Sweetback, is a pimp who kills a police officer to save an

innocent black man and then has to flee the country. The film became

one of the most financially successful independent films in history,

and its explicit sex, extreme violence, criticism of white society, and

powerful antihero protagonist became standards of the genre.

Shaft further solidified the conventions of the blaxploitation

genre. John Shaft is a private detective who is hired to find the

daughter of an African American mobster; the daughter has been

kidnapped by the Mafia. Shaft, portrayed by Richard Roundtree, is

similar to Virgil Tibbs character (both Shaft and Tibbs first appeared

in novels by author Ernest Tidyman) and many suave private detec-

tives from film and television. Shaft was extremely popular with

African American audiences and was widely imitated by other

blaxploitation filmmakers: the cool and aloof hero, white villains, sex

with both black and white women, heavy emphasis on action and

gunplay, and the depiction of the problems of lower income African

Americans all became staples of the blaxploitation movie. Isaac

Hayes’ Academy Award winning ‘‘Theme from Shaft’’ was fre-

quently imitated. Two sequels were made to Shaft: Shaft’s Big Score

and Shaft in Africa. Roundtree also starred in a brief Shaft television

series in 1973.

The peak period for blaxploitation films was 1972-74, during

which seventy-six blaxploitation films were released, an average of

more than two per month. It was in 1972 that Variety and other

publications began using the term blaxploitation to describe these

new action pictures, creating the term by combining ‘‘black’’ with

‘‘exploitation.’’ That same year two former football players, Jim

Brown and Fred Williamson, both began what would be long-running

blaxploitation film careers. Brown starred in Slaughter, about a ghetto

resident who seeks revenge on the Mafia after hoodlums murder his

parents, and in Black Gunn, in which he seeks revenge on the Mafia

after hoodlums murder his brother. Williamson starred in Hammer

(Williamson’s nickname while playing football), in which he por-

trayed a boxer who has conflicts with the Mafia. While former

athletes Brown and Williamson might have dominated the genre,

more accomplished African American actors were also willing to

perform in the lucrative blaxploitation market: Robert Hooks starred

in Trouble Man, William Marshall in Blacula, Hari Rhodes in Detroit

9000, and Calvin Lockhart in Melinda.

The blaxploitation films of this period were extremely popular

with audiences and successful financially as well, but they also were

the subject of much criticism from community leaders and the black

press. These movies were being made by major Hollywood studios

but on lower budgets than most of their other pictures, and many

critics of blaxploitation films felt that the studios were cynically

producing violent junk for the African American audience rather than

making uplifting films with better production values, such as the 1972

release Sounder. Blaxploitation films were also dismissed as simply

black variations on hackneyed material; Jet magazine once called

blaxploitation films ‘‘James Bond in black face.’’ Criticism grew

with a second wave of blaxploitation films whose characters were less

socially acceptable to segments of the public. The 1973 release

Superfly is the best known among these films and was the subject of

the intense protest at the time of its release. The film is about a cocaine

dealer, Priest, who plans to retire after making one last, very large

deal. Priest was never explicitly condemned in the movie, and, as

portrayed by the charismatic Ron O’Neal, actually became something

of a hero to some viewers, who responded by imitating Priest’s

wardrobe and haircut. Other blaxploitation films of the period that

featured criminal protagonists were Black Caesar (Fred Williamson

as a gangster); Willie Dynamite (a pimp); Sweet Jesus, Preacher Man

(a hitman); and The Mack (another pimp).

As the controversy around blaxploitation films grew, producers

moved away from crime films for black audiences and attempted

making black versions of familiar film genres. Particularly popular

were black horror movies, including Blacula and its sequel Scream,

Blacula, Scream; Blackenstein; Alabama’s Ghost; and Abby, which

so resembled The Exorcist that its producers were sued for plagiarism.

Black westerns, such as Adios, Amigo, were also popular, and there

were a few black martial arts films, like Black Belt Jones. Many

producers simply added the word ‘‘black’’ to the title of a previously

existing picture, so that audiences were treated to Black Lolita, Black

Shampoo, and The Black Godfather. Comedian Rudy Ray Moore had

a brief film career with Dolemite and The Human Tornado.

The greatest success of the second wave of blaxploitation

pictures came from American International Pictures and its series of

movies featuring sexy female characters. After appearing in some

prison movies for the studio, Pam Grier starred in Coffy in 1973,

playing a nurse who tries to avenge the death of her sister, a drug

addict. Grier subsequently starred in Foxy Brown, Sheba Baby, and

Friday Foster for American International. AIP also made a few ‘‘sexy

women’’ blaxploitation films with other actresses: Tamara Dobson

starred in Cleopatra Jones and Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of

Gold, and Jeanne Bell played the title role in TNT Jackson.

BLOB ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

280

By the late 1970s, the blaxploitation film had run its course.

From a high of two dozen blaxploitation films released in 1973,

studios moved to four blaxploitation films in 1977 and none at all in

1978. Major studios were now making mainstream black films with

performers like Richard Pryor. With the exception of Fred Williamson,

who moved to Europe where he continued to produce and appear in

low-budget movies, no one was making blaxploitation films by the

end of the 1970s. There have been a few attempts to revive the format.

Brown, Williamson, O’Neal, and martial artist Jim Kelly appeared in

One Down, Three to Go in 1982, and The Return of Superfly was

released in 1990 with a new actor in the lead. Keenen Ivory Wayans

parodied blaxploitation films in I’m Gonna Get You, Sucka.

Like many movie trends, the blaxploitation film genre enjoyed a

rapid success and an almost equally rapid demise, probably hastened

by the highly repetitive content of most of the movies. Blaxploitation

films were undeniably influential and remained so into the 1990s.

Filmmakers such as John Singleton or the Hughes brothers frequently

spoke with admiration of the blaxploitation pictures they enjoyed

growing up, and Spike Lee frequently asserted that without Sweet

Sweetback’s Baaaadassss Song there would be no black cinema

today. Despite their frequent excesses, blaxploitation films were an

important part of American motion pictures in the 1970s.

—Randall Clark

F

URTHER READING:

James, Darius. That’s Blaxploitation. New York, St. Martin’s, 1995.

Martinez, Gerald, Diana Martinez, and Andres Chavez. What It Is . . .

What It Was! New York, Hyperion, 1998.

Parrish, James Robert, and George H. Hill. Black Action Films.

Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 1989.

The Blob

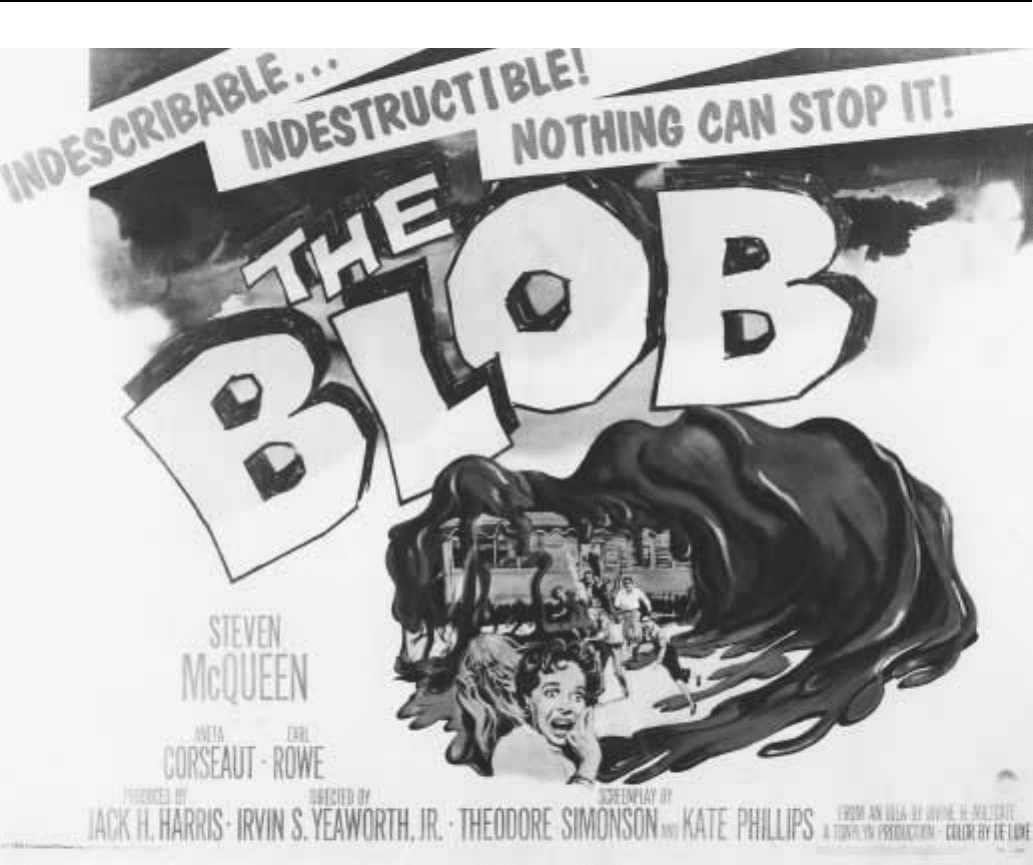

The Blob (1958) is one of a long string of largely forgettable

1950s teenage horror films. The film’s action revolves around a

purple blob from outer space that has the nasty habit of eating people.

At the time, the title was what drew audiences to watch this otherwise

ordinary film. It has since achieved notoriety as both a sublimely bad

film and the film in which Steve McQueen had his first starring role.

—Robert C. Sickels

F

URTHER READING:

Biskind, Peter. Seeing is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us To

Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties. New York, Pantheon, 1983.

Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction

Movies of the Fifties, Volume II. Jefferson, North Carolina,

McFarland, 1986.

Blockbusters

The term blockbuster was originally coined during World War II

to describe an eight-ton American aerial bomb which contained

enough explosive to level an entire city block. After the war, the term

quickly caught the public’s attention and became part of the American

vernacular to describe any occurrence that was considered to be epic

in scale. However, there was no universal agreement as to what events

actually qualified as blockbusters so the post war world was inundat-

ed with colossal art exhibitions, epic athletic events, and even ‘‘larger

than life’’ department store sales all lumped under the heading

of blockbuster.

By the mid-1950s, though, the term began to be increasingly

applied to the motion picture screen as a catch-all term for the wide-

screen cinemascope epics that Hollywood created to fend off the

threat of television, which was taking over the nation’s living rooms.

Such films as Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, a remake

of his earlier silent film, Michael Anderson’s Around the World in 80

Days, and King Vidor’s War and Peace, all released in 1956,

established the standards for the blockbuster motion picture. Every

effort was made to create sheer visual magnitude in wide film (usually

70mm) processes, full stereophonic sound, and lavish stunts and

special effects.

These films were also characterized by higher than average

production budgets (between $6,000,000 and $15,000,000), longer

running times (more than 3 hours), and the need to achieve extremely

high box office grosses to break even, let alone make a profit. Subject

matter was generally drawn from history or the Bible and occasional-

ly from an epic novel which provide a seemingly inexhaustible supply

of colorful characters, broad vistas, and gripping stories.

By this definition, the blockbuster has a history as old as

Hollywood itself. As early as 1898, a version of the passion play was

filmed on the roof of a New York high-rise and a one reel version of

Ben Hur was filmed in 1907. Yet, by 1912, it was Italy that was

establishing the conventions of large scale spectaculars through such

lavish productions as Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo Vadis? (1912) and

Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914). Indeed, it was the latter film—

with its enormous (for the time) production budget of $100,000 and

its world-wide following—that played a major role in taking the

motion picture out of the Nickelodeons into modern theaters and

in establishing the viability of the feature film as a profitable

entertainment medium.

According to some sources, American film pioneer D.W. Grif-

fith was so impressed by Cabiria that he owned his own personal copy

of the film and studied its spectacular sets, its lighting, and its camera

movement as a source of inspiration for his own epics The Birth of a

Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916). Indeed, The Birth of a Nation

was not only the first important product of the American cinema, it set

the standard for the films to follow. Its budget has been placed at

$110,000, which translates into millions of dollars by today’s stan-

dards. Its gross, however, was much higher approaching 100 million

dollars. In fact, a number of historians attest that it may have been

seen by more people than any film in history—a fact that might

be disputed by proponents of Gone with the Wind (1939) and

Titanic (1997).

The Birth of a Nation did, however, change forever the

demographics of the motion picture audience. Prior to its release,

films were considered to be primarily for the working classes, mostly

immigrants who viewed them in small storefront theaters. Griffith’s

film, which treated the U.S. Civil War and related it as an epic human

drama, captured an audience that had previously only attended the

legitimate theater. Through the use of sophisticated camera work,

editing, and storytelling, Griffith created a masterpiece that has been

re-released many times and still maintains the power to shock and

move an audience.

BLOCKBUSTERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

281

The theatrical poster for the film The Blob.

Griffith’s second attempt at a blockbuster one year later exposed

the inherent risks of big-budget filmmaking. Though Intolerance is

generally considered as an artistic milestone and is generally credited

with influencing the fledgling Soviet film industry in the 1920s, it was

a financial disaster for its director. Made on a budget of $500,000

(several million in today’s dollars), it never found its audience. Its

pacifist tone was out of step with a public gearing itself for America’s

entry into World War I. Also, instead of one straight forward

narrative, it shifted back and forth between a modern story, sixteenth-

century France, ancient Babylon, and the life of Christ; the stories

were all linked by the common theme of intolerance. The human

drama was played out against giant sets and spectacular pageantry.

Yet, audiences appeared to balk at the four storylines and stayed away

from the theater, making it arguably the first big budget disaster in the

history of film.

Although film budgets grew considerably during the next two

decades, leading to some notable blockbusters as Ben-Hur (1926) and

San Francisco (1936), it was not until 1939 with the release of Gone

with the Wind that the form reasserted itself as a major force on the

level of contemporary ‘‘event pictures.’’ The film, which was based

on a nation-wide best-selling novel by Margaret Mitchell, was

produced by David O. Selznick and returned to the theme of the U.S.

Civil War covered by Griffith. Although box office star Clark Gable

was the popular choice for the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick was able

to milk maximum publicity value by conducting a high profile public

search for an actress to play the role of Scarlett O’Hara. Fan

magazines polled their readers for suggestions but the producer

ultimately selected British actress Vivian Leigh, a virtual unknown in

the United States. Another publicity stunt was the ‘‘burning of

Atlanta’’ on a Culver City backlot consisting of old sets and other

debris as the official first scene to be filmed. By the time that the film

had its official premiere in Atlanta in 1939, the entire world was ready

to experience the ‘‘big screen,’’ Technicolor experience that was

Gone with the Wind.

The film was a monumental success during its initial run and

continued to pack audiences in during subsequent reissues in 1947,

1954, 1961, 1967, and 1998. In the 1967 run, the film was blown up to

70mm to effectively compete with the large screen blockbusters of the

BLOCKBUSTERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

282

1960s such as Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and The Sound of Music

(1965). Thus removed from its natural aspect ratio, it did not fare

particularly well against its modern competition. A decade later,

when restored to its normal screen size, it made its debut on NBC and

drew the largest audience in television history. In terms of sheer hype,

marketing, and production values, Gone with the Wind constituted the

prototype for what the blockbuster would come to be. From the time

of its release until 1980, it became, in terms of un-inflated dollar

value, the most profitable film ever made.

The blockbuster phenomenon died down until the mid-1950s

when the emergence of new wide-screen technologies and the on-

slaught of television prompted Hollywood to give its viewers a

spectacle that could not be duplicated on the much smaller screen in

the living room. Although first dismissed as novelties, these films

built on the precedents established by Gone with the Wind and built

their success on lavish production budgets, biblical and literary

source material, and sheer big screen spectacle. The first major

success was King Vidor’s War and Peace in 1956. With a running

time of nearly three and one half hours, it was a true visual epic. It was

quickly followed by Cecil B. DeMille’s remake of his silent epic The

Ten Commandments, and Michael Anderson’s Around the World in

80 Days.

Yet, within the very success of these blockbusters were the

ingredients that would bring them to a halt in the 1960s. In order to

create the large screen spectacles that were the trademark of the wide-

screen 1950s films, the producers had to allocate larger production

budgets than were the average for their standard releases. This meant

that the studio had to drastically decrease the number of films that it

made during a given year. Also, the longer running time of the

blockbusters reduced the number of showings that a film would

receive in the neighborhood theater.

To get around this situation, distributors created the road show

exhibition scheme. A large budget film such as West Side Story

(1961) would open only at large theaters in major metropolitan areas

for, in some cases, as long as a year. The film would become an event

much like a Broadway play and could command top dollar at the box-

office. Both sound and projection systems would feature the latest

technology to captivate the audience and make the evening a true

theatrical experience. Once this market began to diminish, the film

would be released to neighborhood theaters with considerably inferi-

or exhibition facilities. Still, the public flocked to these motion

pictures to see what all of the shouting was about.

This production and distribution strategy was based on the film

being a hit. Unfortunately, most of the films that followed the

widescreen extravaganzas of the mid-1950s failed to make their

money back. The most notable example was Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s

1963 Cleopatra, which cost Twentieth Century-Fox more than 40

million dollars to produce over a four year period. Although it had a

number of theoretically ‘‘sure fire’’ ingredients—the pairing of

Elizabeth Taylor and her then-lover Richard Burton (who were at the

center of a highly publicized Hollywood divorce case) and every

element of big screen spectacle that its producers could muster—it

bombed at the box-office and never made its money back. This

debacle almost brought Fox to its knees and illustrated the damage

that an ill conceived blockbuster could do to a studio.

Thus although several films, such as The Sound of Music, which

cost only $8 million to make and which returned $72 million in the

domestic market alone, continued to show the profit potential of the

blockbuster concept, the practice temporarily died out simply because

studios could not afford to put all of their financial eggs in one

cinematic basket.

During the 1970s, production costs for all films began to rise

substantially, causing the studios to produce fewer and fewer films

and to place a significantly larger share of the budget into advertising

and promotion in an attempt to pre-sell their films. This idea was

enhanced through a variety of market and audience research to

determine the viability of specific subjects, stories, and actors. Such

practices led to the production of films carefully tailored to fit the

audience’s built-in expectations and reduced the number of edgy,

experimental projects that studios would be willing to invest in.

The financial success of several conventionally-themed big-

budget films at the beginning of the decade, including Love Story

(1970), Airport (1970), and The Godfather (1972), proved that the

theory indeed worked and proved that the right amount of research,

glitz, and hype would pay huge dividends at the box-office. By the

end of the decade two other films—Star Wars (1977) and Jaws

(1975)—demonstrated that the equation could even be stretched to

generate grosses in the hundreds of millions of dollars if the formula

was on target. The latter two films demonstrated that the success of

even one blockbuster could effect the financial position of a studio. In

1997, for example, the six top grossing films in the U.S. market

accounted for more than one-third of the total revenues of distributors.

Despite the failure of the $40 million Heaven’s Gate in 1980 and

the increasingly high stakes faced by studios in order to compete, the

trend toward blockbusters continued unabated into the 1980s. A

major factor in this development, however, was the fact that most of

the major studios were being acquired by large conglomerates with

financial interests in a variety of media types. These companies

viewed the motion picture as simply the first stage in the marketing of

a product that would have blockbuster potential in a variety of

interlocking media including books, toys, games, clothing, and per-

sonal products. In the case of a successful film, Star Wars or Batman,

for example, the earnings for these items would far exceed the box

office revenues and at the same time create an appetite for a sequel.

This situation often affected the subject matter dealt with by the

film. The question thus became ‘‘How well can the film stimulate the

after-markets.’’ Established products such as sequels and remakes of

popular films were deemed to be the most commercial vehicles for

developing related lines of merchandise. Original screenplays—

unless they were based on successful ‘‘crossover’’ products from

best-selling novels, comic books, or stage plays with built-in audi-

ences—were deemed to be the least commercial subjects.

At the same time, studios were re-thinking their distribution

strategy. Whereas the road show method had worked during the

1960s the merchandising needs of linked media conglomerates re-

quired a new concept of saturation booking. According to this

strategy, a film would be released simultaneously in more than 2000

theaters all over the United States to create the largest opening

weekend possible and generate enough strong ‘‘word of mouth’’

recommendations to create a chain reaction that would open up all of

the additional markets world wide and trigger additional markets

in video sales, pay TV, and network TV as well as toys and

other merchandise.

The primary criteria for creating films that lend themselves to

multi-media marketing was to choose subjects which were appealing

to the prime 14- to 25-year-old age group but which also had

attractions for a family audience. Thus, event films were usually

pegged to the two heaviest theater going periods of the year, summer

and Christmas. This insures that if the film is targeted at a younger

BLONDIEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

283

audience, it will still attract the parents of children or teenagers who

might accompany them to the theater.

Additionally, the video and television markets also assisted in

creating the reception for theatrical projects. The highly successful

Rambo series of the 1980s began with a moderately successful

medium-budget theatrical film, First Blood (1982), which might

never have generated a sequel had it not been a runaway video hit. The

success of the video created a built-in audience for the much higher

budgeted Rambo: First Blood, Part Two (1985), which in turn

generated toys, action figures, video games, and an animated TV series.

In the 1990s, the stakes rose even higher, with higher budgeted

films requiring correspondingly higher grosses. Such large budgeted

films as Batman and Robin (1997) and Waterworld (1995) were

deemed ‘‘failures’’ because their fairly respectable grosses still did

not allow the film to break even due to the scale of their production

costs. The ultimate plateau may have been reached with James

Cameron’s Titanic, with a production budget so large—over $200

million—that it took two studios (Twentieth Century-Fox and Para-

mount) to pay for it.

Titanic became the biggest moneymaking film in the history of

motion pictures, with a gross approaching $1 billion worldwide. Such

success is largely due to the fact that writer/director James Cameron

created a film that appealed to every major audience demographic

possible. For the young girls, there was its star Leonardo Di Caprio,

the 1990s heartthrob, and a love story; for young men there was the

action of the sinking ship; for the adults, there was the historical epic

and the love story.

As for the future, the success of Titanic will undoubtedly tempt

producers to create even larger budgeted films crammed with ever

more expensive special effects. Some of these productions will be so

large that they will have to be funded by increasingly intricate

financial partnerships between two or more production entities sim-

ply to get the film off the ground. The stakes will, of course, be

enormous, with the fate of an entire studio or production company

riding on the outcome of a single feature. Yet, despite the high risk

factor, the blockbuster trend will continue to exert a siren-like allure

for those at the controls of Hollywood’s destiny. Unlike the days of

Griffith and Selznick, it is no longer enough to simply tell a good story

in a cinematic way. If a film cannot sell toys and software, it may not

even get made.

—Steve Hanson and Sandra Garcia-Myers

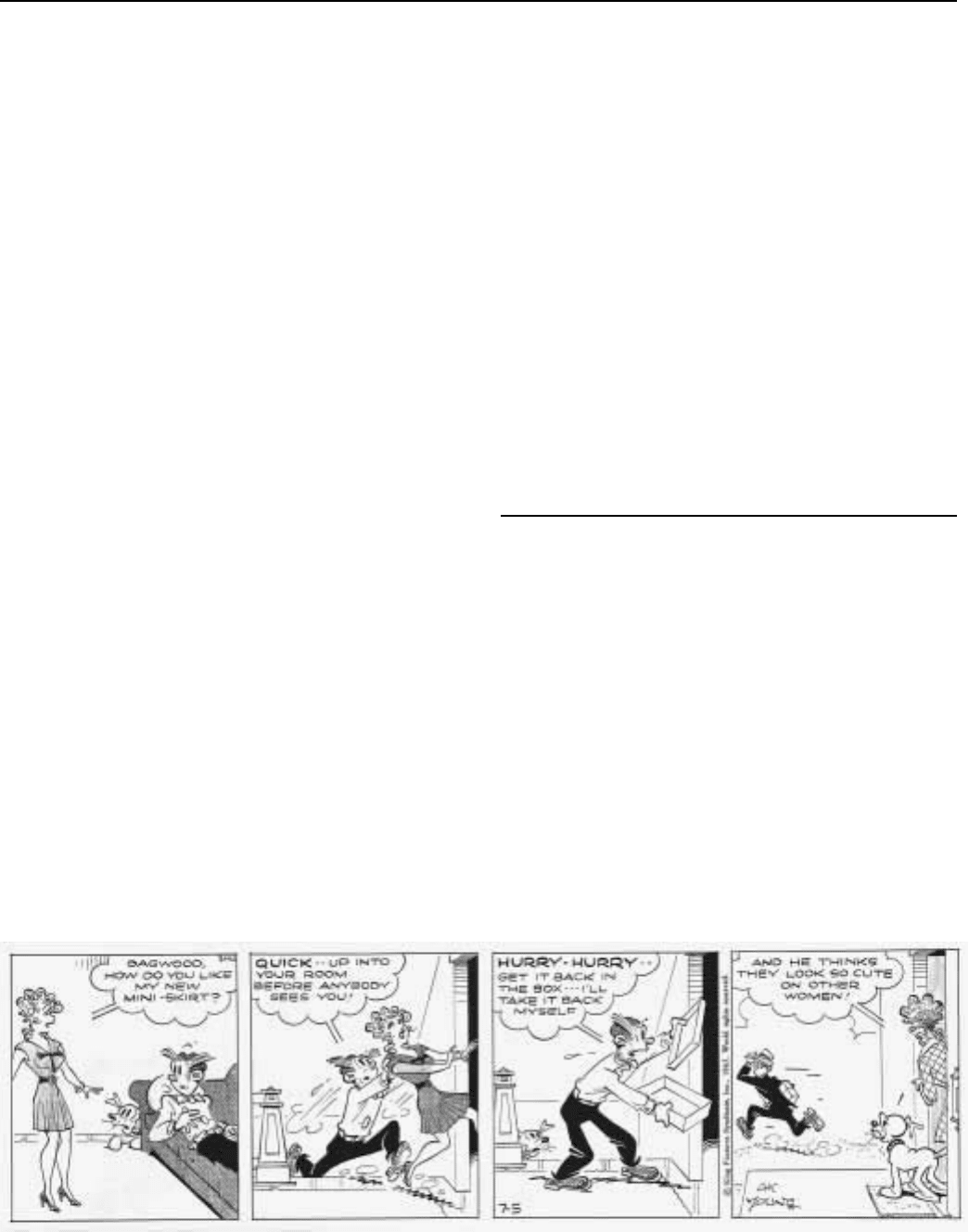

A four-frame strip from the comic Blondie.

FURTHER READING:

Aufderheide, Pat. ‘‘Blockbuster.’’ In Seeing Through Movies, edited

by Mark Crispin Miller. New York, Pantheon, 1990.

Cook, David. A History of Narrative Film. 3rd ed. New York, W.W.

Norton & Company, 1996.

Edgerton, Gary R. American Film Exhibition and an Analysis of the

Motion Picture Industry’s Market Structure, 1963-1980. New

York, Garland, 1983.

Gomery, Douglas. Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presenta-

tion in the United States. Madison, University of Wisconsin

Press, 1992.

Maltby, Richard, and Ian Craven. Hollywood Cinema: An Introduc-

tion. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995

Parkinson, David. The Young Oxford Book of the Movies. New York,

Oxford University Press, 1995.

Wyatt, Justin. High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood.

Austin, University of Texas Press, 1994.

Blondie (comic strip)

One of the longest-running marriages in the funnies is that of

Blondie Boopadoop and Dagwood Bumstead. The couple first met in

1930, when Blondie was a flighty flapper and Dagwood was a

somewhat dense rich boy, and they were married in 1933. They’re

still living a happy, though joke-ridden life, in close to 2000 newspa-

pers around the world. The Blondie strip was created by Murat

‘‘Chic’’ Young, who’d begun drawing comics about pretty young

women in 1921.

After several false starts—including such strips as Beautiful Bab

and Dumb Dora—Young came up with Blondie and King Features

began syndicating it in September of 1930. Initially Blondie read like

Young’s other strips. But after the couple married and the disinherited

Dagwood took a sort of generic office job with Mr. Dithers, the

feature changed and became domesticated. Blondie turned out to be

far from flighty and proved to be a model housewife, gently manipu-

lating her sometimes befuddled husband. The gags, and the short

continuities, centered increasingly around the home and the office,

frequently concentrating on basics like sleeping, eating, and working.

BLONDIE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

284

The birth of their first child, Baby Dumpling, in the spring of

1934 provided a new source of gags and helped win the strip an even

larger audience. Young perfected running gags built around such

props and situations as Dagwood’s naps on the sofa, his monumental

sandwiches, his conflicts with door-to-door salesmen, Blondie’s new

hats, and his wild rushes to catch the bus to work. Other regular

characters were neighbors Herb and Tootsie Woodley, Daisy the

Bumstead dog and, eventually, her pups, and Mr. Beasley the

postman, with whom Dagwood frequently collided in his headlong

rushes to the bus stop. The Bumstead’s second child, daughter

Cookie, was born in 1941.

King effectively merchandised the strip in a variety of mediums.

There were reprints in comic books and Big Little Books and, because

of Dagwood’s affinity for food, there were also occasional cook-

books. More importantly, Young’s characters were brought to the

screen by Columbia Pictures in 1938. Arthur Lake, who looked born

for the part, played Dagwood and Penny Singleton, her hair freshly

bleached, was Blondie. Immediately successful, the series of ‘‘B’’

movies lasted until 1950 and ran to over two dozen titles. The radio

version of Blondie took to the air on CBS in the summer of 1939, also

starring Singleton and Lake. Like the movies, it was more specific

about Dagwood’s office job and had him working for the J.C. Dithers

Construction Company. The final broadcast was in 1950 and by that

time Ann Rutherford was Blondie. For the first television version on

NBC in 1957 Lake was once again Dagwood, but Pamela Briton

portrayed Blondie. The show survived for only eight months and a

1968 attempt on CBS with Will Hutchins and Patricia Harty lasted for

just four. Despite occasional rumors about a musical, the Bumsteads

have thus far failed to trod the boards on Broadway.

A journeyman cartoonist at best, Young early on hired assistants

to help him with the drawing of Blondie. Among them were Alex

Raymond (in the days before he graduated to Flash Gordon), Ray

McGill and Jim Raymond, Alex’ brother. It was the latter Raymond

who eventually did most of the drawing Young signed his name to.

When Young died in 1973, Jim Raymond was given a credit. Dean

Young, Chic’s son, managed the strip and got a credit, too. After

Raymond’s death, Stan Drake became the artist. Currently Denis

Lebrun draws the still popular strip.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Blackbeard, Bill and Dale Crain. The Comic Strip Century.

Northampton, Kitchen Sink Press, 1995.

Waugh, Coulton. The Comics. New York, The Macmillan Compa-

ny, 1947.

Blondie (rock band)

The 1970s were a transitional period in popular music. Emerging

from the new wave and punk rock scene, the band Blondie, featuring

Deborah Harry, achieved both critical and commercial success.

Blondie transcended mere popularity by moving away from blues-

based rock and capitalizing on the personality and musical ingenuity

of its lead singer. Blondie successfully incorporated elements from a

number of different musical forms into its music, including rap,

reggae, disco, pop, punk, and rock.

After a number of early failures, Deborah Harry and Chris Stein

formed Blondie in 1973. The name for the band came from the cat

calls truck drivers used to taunt Deborah Harry, ‘‘Come on Blondie,

give us a screw!’’ Harry parodied the dumb blonde stereotype into

platinum. She appeared on stage in torn swimsuit and high heels,

vacantly staring into space. In 1977 the act and the talent paid off in

the band’s hit ‘‘Denis,’’ and was soon followed by ‘‘Heart of Glass.’’

The strength of Blondie, Deborah Harry, also proved its weak-

ness. Jealousy led to the dissolution of the group in 1984. Harry went

on her own, achieving some success—her tours continually sold-out

whether she was alone or with the Jazz Passengers. But her solo

success has never reached that of the group Blondie.

By 1997, Blondie had reunited for a tour, completed an album in

1998, and had begun touring once again. The band members claimed

not to remember why they split and seemed eager to reunite. Their

fans also eagerly anticipated a more permanent reunion. Blondie has

greatly influenced the bands that have come after it, and Deborah

Harry has continued to explore new genres with success.

—Frank A. Salamone, Ph.D.

Bloom County

A popular daily comic strip of the 1980s, Bloom County was

written and drawn by Berkeley Breathed. During its run, the comic

strip reveled in political, cultural, and social satire. Capturing popular

attention with witty comment, the strip also offered a new perspective

in the comics.

Bloom County began in 1980 with the setting of the Bloom

Boarding House in the mythical Bloom County. Both boarding house

and county appeared to be named for a local family, originally

represented in the comic strip by the eccentric Major Bloom, retired,

and his grandson Milo. Other original residents included Mike

Binkley, a neurotic friend of Milo; Binkley’s father; Bobbi Harlow, a

progressive feminist school teacher; Steve Dallas, a macho despica-

ble lawyer; and Cutter John, a paralyzed Vietnam vet. Over the years,

the boarding house residents changed; the Major and Bobbi Harlow

vanished and the human inhabitants were joined by a host of animals

including Portnoy, a hedgehog, and Hodge Podge, a rabbit. But two

other animals became the most famous characters of the strip. One, a

parody of Garfield, was Bill the Cat, a disgusting feline that usually

just said ‘‘aack.’’ The other was the big-nosed penguin named Opus,

who first appeared with a much more diminutive honker as Binkley’s

pet, a sorry substitute for a dog. Opus eventually became the star of

the strip and when Breathed ended the comic, he was the last character

to appear.

Breathed used his comic menagerie to ridicule American socie-

ty, culture, and politics. Reading through the strip is like reading

through a who’s who of 1980s references: Caspar Weinberger, Oliver

North, Sean Penn and Madonna, Gary Hart. Breathed made fun of

them all. In the later years of the strip, Donald Trump and his

outrageous wealth became a chief focus of Breathed’s satire. In the

world of Bloom County, Donald Trump’s brain was put in the body of

Bill the Cat. The strip supposedly ended because Trump the Cat

bought the comic and fired all of the ‘‘actors.’’

Breathed didn’t restrain himself to ridiculing individuals. He

also attacked American fads, institutions, and corporations. Opus had

a nose job and constantly bought stupid gadgets advertised on TV.

BLOUNTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

285

Milo and Opus both worked for the Bloom Picayune, the local

newspaper, and Breathed used them to launch many attacks on the

media. He lampooned the American military through the creation of

Rosebud, a basselope (part basset hound, part antelope) that the

military wanted to use to smuggle bombs into Russia. Corporations

such as McDonalds and Crayola felt the barb of Breathed’s wit,

though not as much as Mary Kay Cosmetics. Breathed had Opus’s

mother being held in a Mary Kay testing lab. Breathed used this to

point out the cruelties of animal testing as well as the extremism of the

animal rights terrorists. The terrorists faced off against the Mary Kay

Commandos, complete with pink uzis.

Breathed was adept at political satire as well. Whenever the

country faced a presidential election, The Meadow Party would

emerge with its candidates: Bill the Cat for President and an often

reluctant Opus for V.P. Breathed used the two to ridicule not only

politicians but the election process and the American public’s willing-

ness to believe the media campaigns. Breathed had a definite political

slant to his comic, but he made fun of the follies of both conservatives

and liberals.

Bloom County was a unique creation not only because of its

humor, but because of the unusual perspectives Breathed used. Unlike

other comics, Bloom County’s animal and human characters interacted

as equals and spoke to each other. Breathed also made the strip self-

reflexive, often breaking from the comic to give comments from the

‘‘management’’ or from the characters themselves. One sequence

featured Opus confused because he hadn’t read the script. Setting the

comic up as a job for the characters to act in, Breathed was able to

acknowledge the existence of other strips, making jokes about them

and featuring guest appearances by characters from other comic

strips. As Bloom County came to an end, Breathed had the characters

go off in search of jobs in the other comics strips, such as Family

Circle and Marmaduke. While some other comics have used this

technique as well, notably Doonesbury, it remains rare in comics, and

Bloom County was most often compared to Doonesbury for content

and attitude. Also like Doonesbury, in 1987 Bloom County won the

Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning.

The strip was not without its flaws, the chief one being a lack of

strong female characters, a lack Breathed was well aware of (and

commented on in the strip). While the male characters stayed strong,

the female characters dropped out. When the strip ended, the only

female characters were Ronald-Ann, a poverty stricken African

American girl and Rosebud the Basselope who earlier in the comic’s

run turned out to be female. Besides a lack of women characters,

many readers felt that the comic was offensive and not funny and

often lodged complaints with Breathed.

Breathed ended the strip in 1989 when he felt he had reached the

end of what he could do with these characters. He followed Bloom

County with a Sunday-only strip called Outland. The strip at first

featured Opus and Ronald-Ann though most of Bloom County’s cast

eventually showed up. It never gained the popularity of its predeces-

sor, and Breathed stopped writing comics and turned to the writing of

children’s books.

—P. Andrew Miller

F

URTHER READING:

Astor, David. ‘‘Breathed Giving Up Newspaper Comics.’’ Editor and

Publisher. January 21, 1995.

Breathed, Berkeley. Bloom County Babylon. Boston, Little

Brown, 1986.

———. Classics of Western Literature: Bloom County 1986-1989.

Boston, Little Brown, 1990.

Buchalter, Gail. ‘‘Cartoonist Berke Breathed Feathers His Nest by

Populating Bloom County with Rare Birds.’’ People Weekly.

August 6, 1984.

Blount, Roy, Jr. (1941—)

An heir to the Southern humor writing tradition of Mark Twain

and Pogo, Roy Blount, Jr. has covered a wide array of subjects—from

a season with an NFL team to the Jimmy Carter presidency—with

equal parts incisiveness and whimsy.

Roy Blount, Jr. was born in Indianapolis on October 5, 1941. As

an infant, he moved with his parents to their native Georgia, where his

father became a civic leader in Decatur, and his family lived a

comfortably middle-class life during the 1950s. He attended Vanderbilt

University in Nashville on a Grantland Rice scholarship, and much of

his early journalism work was, like Rice’s, in sportswriting. In 1968,

Blount began writing for Sports Illustrated, where he quickly became

known for his offbeat subjects.

In 1973 Blount decided to follow a professional football team

around for one year—from the offseason through a bruising NFL

campaign—in order to get a more nuanced look at players and the

game. He chose the Pittsburgh Steelers, a historically inept franchise

on the verge of four Super Bowl victories. His 1973-1974 season with

the Steelers became About Three Bricks Shy of a Load. Blount studied

each element of the team, from its working-class fans to its front

office to its coaches and players, with lively digressions on the city of

Pittsburgh, country-western music (Blount once penned a country

ballad entitled, ‘‘I’m Just a Bug on the Windshield of Life’’), and

sports nicknames.

With the success of About Three Bricks Shy of a Load, Blount

became a full-time free-lance humor writer, with contributions in

dozens of magazines including Playboy, Organic Gardening, The

New Yorker, and Rolling Stone. In the late 1980s he even contributed a

regular ‘‘un-British cryptic crossword puzzle’’ to Spy Magazine.

The administration of fellow Southerner Jimmy Carter led to

Blount’s 1980 book Crackers, which featured fictional Carter cousins

(‘‘Dr. J.E.M. McMethane Carter, 45, Rolla, Missouri, interdisciplina-

ry professor at the Hugh B. Ferguson University of Plain Sense and

Mysterophysics’’; ‘‘Martha Carter Kelvinator, 48, Bullard Dam,

Georgia, who is married to a top-loading automatic washer’’) and

angst-ridden verses about the 39th President:

I’ve got the redneck White House blues.

The man just makes me more and more confused.

He’s in all the right churches,

and all the wrong pews,

I’ve got the redneck White House blues.

Blount’s most significant chapter focused on Billy Carter, who

frequently embarrassed his brother’s White House with impolitic

comments and behavior. Blount came to like the younger Carter, and

found that his fallibility made the Carters more likable: ‘‘I don’t want

people to be right all the time.’’

Throughout the 1980s Blount continued free-lancing articles

and publishing books, with such offbeat titles as What Men Don’t Tell

BLUE VELVET ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

286

Women, One Fell Soup, and Not Exactly What I Had in Mind.

Blount’s subject matter included orgasms, waffles (he wrote a poem

to them), baseball batting practice, and the federal budget deficit

(Blount suggested that every American buy and throw away $1,000

worth of stamps each, to fill the Treasury’s coffers). He eulogized

Elvis Presley (titled ‘‘He Took the Guilt out of the Blues’’) and

profiled ‘‘Saturday Night Live’’ cast members Bill Murray and Gilda

Radner. And the former sportswriter delivered essays on Joe DiMaggio

and Roberto Clemente to baseball anthologies, while also attending a

Chicago Cubs fantasy camp under the direction of Hall of Fame

manager Leo Durocher.

Blount’s first novel was the best-selling First Hubby, a comic

account of the bemused husband of America’s first woman president.

His writing attracted the attention of film critic and producer Pauline

Kael, who encouraged him to develop screenplays. His first produced

effort was the 1996 major motion picture comedy Larger than Life,

starring Bill Murray, Janeane Garafolo, and a giant elephant.

Blount became one of the most visible humorists in America as a

frequent guest on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and he often

appeared on the long-running A Prairie Home Companion radio

series, hosted by close friend Garrison Keillor. Despite possessing

what he acknowledged as a weak singing voice, Blount triumphantly

joined the chorus of the Rock Bottom Remainders, a 1990s novelty

rock band composed of such best-selling authors as Dave Barry,

Stephen King, and Amy Tan.

Divorced twice, Blount has two children. In 1998 he wrote a

best-selling memoir, Be Sweet, where he acknowledged his ambiva-

lent feelings towards his parents (at one point actually writing, ‘‘I

hated my mother.’’). Later that year he also contributed text to a

picture book on one of his favorite subjects, dogs, with a truly Blount-

esque title: If Only You Knew How Much I Smell You.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Blount, Roy, Jr. Be Sweet. New York, Knopf, 1998.

———. Crackers. New York, Knopf, 1980.

Gale, Stephen H., editor. Encyclopedia of American Humorists. New

York, Garland Press, 1988.

Blue Jeans

See Jeans; Levi’s; Wrangler Jeans

Blue Velvet

Among the most critically acclaimed movies of 1986, Blue

Velvet was director David Lynch’s commentary on small-town America,

showing the sordid backside of the sunny facade. That said, the film is

not strictly a condemnation of the American small-town so much as it

is a kind of coming-of-age story. Lynch described the film as ‘‘a story

of love and mystery.’’ This statement may ostensibly refer to the

relationship between the film’s protagonist Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle

MacLachlan) and the police detective’s daughter Sandy Williams

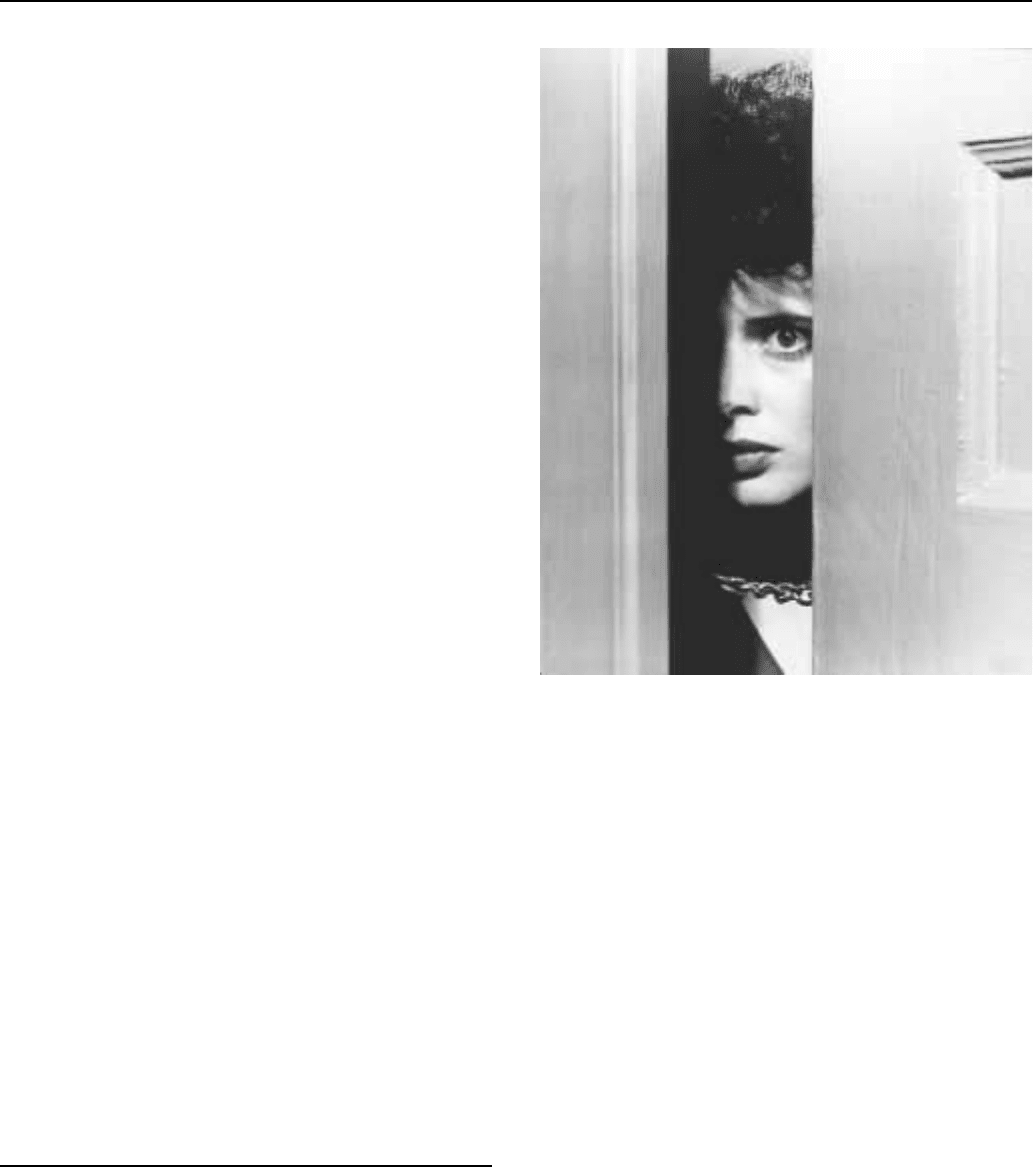

Isabella Rossellini in a scene from the film Blue Velvet.

(Laura Dern) and the mystery they attempt to solve in plucky Nancy

Drew style, but it might also be seen as a statement about the mingling

of affection and fear that arises in the movie’s examination of the

fictional but truthful setting, Lumbertown. One can see Blue Velvet as

a coming-of-age story, not only for Jeffrey, but for the idea of the

idyllic American small town. The loss of innocence may be regretta-

ble, but is ultimately necessary.

The opening scene summarily characterizes Blue Velvet in

theme and plot. Following the lush, fifties-style opening credits, the

screen shows a blue sky, flowers, the local firefighters riding through

town waving, and Jeffrey’s father watering the lawn, all in brilliant,

almost surreal color. Then the scene, which might have come from a

generation earlier, is interrupted by a massive stroke that drops Mr.

Beaumont to his back. The camera pans deeply into the well groomed

lawn and uncovers combating insects. Likewise, the camera plunges

unflinchingly into the unseen, discomforting side of Lumbertown.

The story really begins when Jeffrey, walking back from visiting

his father in the hospital, discovers a severed ear in the grass by a lake.

After turning the ear over to the police, Jeffrey decides to find out the

story for himself, and with the help of Sandy, gets enough information

to start his own investigation. The trail leads to Dorothy Vallens

(Isabella Rossellini) a nightclub singer whose husband and son have

been kidnapped. Thus, the story begins as a rather traditional mystery,

but the tradition drops away as Jeffrey comes face to face with the

most disturbing of people, particularly the demonic kidnapper, Frank

Booth (Dennis Hopper). Frank is a killer and drug dealer of almost

inhuman proportions and perversions. He alternately calls himself

‘‘daddy’’ and ‘‘baby’’ as he beats and rapes Dorothy.

BLUEGRASSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

287

That the story has a reasonably happy ending, with villains

vanquished and Jeffrey united with Sandy, is not altogether comfort-

ing. The film may return to the bright colors and idyllic lifestyle

presented in the opening scene, but the audience now knows that

something else goes on below the surface. Jeffrey and Sandy tell each

other that it’s a strange world, but they say it whimsically, the facade

restored for the characters, if not for the audience. Perhaps the most

significant scene of the film is when, in his own sexual encounter with

Dorothy, Jeffrey strikes her on her command. With the blow Jeffrey

crosses over from an innocent trapped in a situation beyond his

control to a part of the things that go on behind the closed doors

of Lumbertown.

The film was a risky one. David Lynch, though recognized for

work on films like The Elephant Man and Eraserhead, was coming

off the financial failure of Dune. Moreover, this was the first film that

was entirely his. He had written the script and insisted on full artistic

freedom on what was to clearly be a rather disturbing film, with a

violent sexual content unlike any that had previously been seen on

screen. He was granted such freedom after agreeing to a minute

budget of five million dollars, and half salary for himself. The other

half would be paid if the film was a success. It was. The film garnered

Lynch an Academy Award nomination for his direction. Despite such

accolades, the film was not embraced whole-heartedly by all. The

Venice Film Festival, for instance, rejected it as pornography.

The stunning direction of the film combines bald faced direct-

ness in presenting repelling scenes of sex and violence with subtle

examinations of the mundane. By slowing the film, for instance, the

pleasantness of Lumbertown in the open air seems dreamlike and

unreal. While shots like these establish an expressionistic, symbolic

screen world, others realistically place us in a situation where we see

what the characters see, hear what they hear, and these perceptions

form an incomplete picture of the action. Similar techniques crop up

in earlier Lynch films, but it is here, in what many consider the

director’s masterpiece, that they come to full fruition. The direction of

Blue Velvet paved the road for the similar world of Twin Peaks,

Lynch’s foray into television, which itself widened the possibilities of

TV drama.

Stylistically, Lynch’s body of work, and particularly Blue Velvet

has greatly influenced filmmakers, especially those working indepen-

dently from the major Hollywood studios, and even television.

Moreover, Blue Velvet strongly affected many of its viewers. The

large cult following of the movie suggests that it perhaps opened

many eyes to the different facets of life, not only in small towns, but in

all of idealized America. Or more likely, the film articulated what

many already saw. Frank may rage like a demon on screen, like a

creature from our darkest nightmares, but the discomfort with the

pleasant simplicity of Americana, the knowledge that things are

rarely what they seem, is quite real. Blue Velvet reminds us of that,

even as it looks back longingly, if now soberly, at the false but

comforting memory of a romance with the American ideal.

—Marc Oxoby

F

URTHER READING:

Chion, Michel. David Lynch. London, British Film Institute, 1995.

Kaleta, Kenneth C. David Lynch. New York, Twayne, 1993.

Nochimson, Martha P. The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in

Hollywood. Austin, University of Texas Press, 1997.

Blueboy

From its first issue in 1975, Blueboy was a pioneer in gay

monthly magazines. Its focus was on an upscale, urban gay market.

While containing slick, full frontal male nude photography, the

publication also strove to include contemporary gay authors. Writings

by Patricia Nell Warren, Christopher Isherwood, Truman Capote,

John Rechy, Randy Shilts, and many others graced the pages. Led by

former TV Guide ad manager Donald Embinder, the magazine

quickly went from a bimonthly to monthly publication in a year and a

half. By the late 1970s Blueboy was cited in the press as a publishing

empire, producing the monthly magazine and a small paperback press

collection, and trading on Wall Street. Blueboy’s style was soon

mimicked by other publications. Due to changes in style, content, and

format Blueboy lost its appeal during the 1980s and 1990s. At the

same time, an ever increasing range of competing glossy male

magazines, modeled upon Blueboy principles, diminished its readership.

—Michael A. Lutes

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘A Gay Businessman: Out of the Closet . . . And onto Wall Street.’’

Esquire. March 13, 1979, 11.

Kleinfield, N.R. ‘‘Homosexual Periodicals Are Proliferating.’’ New

York Times. August 1, 1978, Sec IV, 4-5.

Bluegrass

Since its development in the mid-1940s, bluegrass music has

become one of the most distinctive American musical forms, attract-

ing an intense audience of supporters who collectively form one of

popular music’s most vibrant subcultures. A close cousin of country

music, bluegrass music is an acoustic musical style that features at its

core banjo, mandolin, guitar, double bass, and fiddle along with close

vocal harmonies, especially high-tenor harmony singing called the

‘‘high lonesome sound.’’ Because of its largely acoustic nature,

bluegrass is a term often used to describe all kinds of acoustic, non-

commercial, ‘‘old-timey’’ music popular among rural people in the

United States in the decades prior to World War II. That characteriza-

tion, however, is incorrect. Bluegrass was developed, and has contin-

ued ever since, as a commercial musical form by professional

recording and touring musicians. Often seen as being a throwback to

this pre-World War II era, bluegrass is instead a constantly evolving

musical style that maintains its connections to the past while reaching

out to incorporate influences from other musical styles such as jazz

and rock music. As such, it remains a vibrant musical form in touch

with the past and constantly looking toward the future.

Although bluegrass has connections to old-timey rural music

from the American south, as a complete and distinct musical form,

bluegrass is largely the creation of one man—Bill Monroe. Born near

Rosine, Kentucky on September 13, 1911, Monroe grew up in a

musical family. His mother was a talented amateur musician who

imparted a strong love of music in all of her eight children, several of

whom became musicians. As a child, Bill Monroe learned to play

guitar with a local black musician, Arnold Schultz (often accompany-

ing Schultz at local dances), and received additional training from his

BLUEGRASS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

288

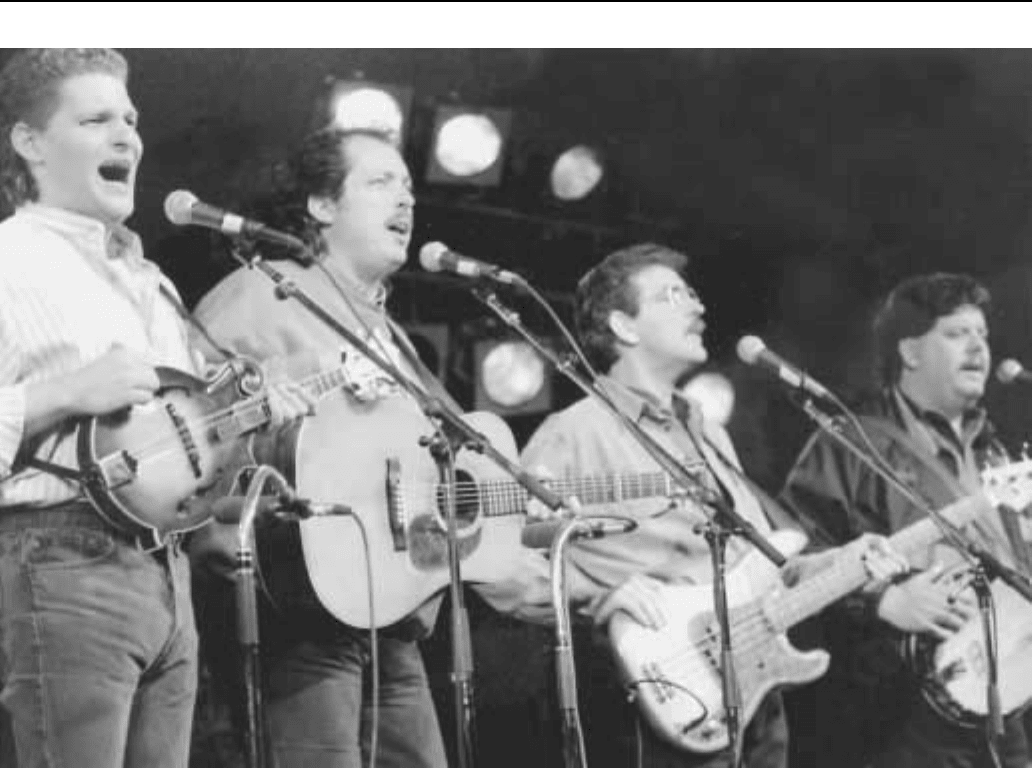

IIIrd Tyme Out vocal group, on stage at the IBMA Bluegrass Fan Fest in Kentucky.

uncle, Pendelton Vandiver, a fiddle player who bequeathed to Mon-

roe a vast storehouse of old tunes in addition to lessons about such

important musical concepts as timing. Although his early training was

on the guitar, Monroe switched to the mandolin in the late 1920s in

order to play along with his older brothers Birch and Charlie, who

already played fiddle and guitar, respectively. In 1934, Charlie and

Bill formed a professional duet team, the Monroe Brothers, and set

out on a career in music. They became very popular, particularly in

the Carolinas, and recorded a number of records, including My Long

Journey Home and What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul.

Their partnership was a brief one, however, as their personal differ-

ences, often expressed in physical and verbal fighting, sent them in

separate directions in 1938.

On his own, and out from under his older brother’s shadow, Bill

Monroe began to develop his own style of playing that would evolve

into bluegrass. He organized a short-lived band called the Kentuckians in

1938. Moving to Atlanta that same year, he formed a new band which

he named the Blue Grass Boys in honor of his native Kentucky. The

group, consisting of Monroe on mandolin, Cleo Davis on guitar, and

Art Wooten on fiddle, proved popular with audiences, and in October

1939 Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys earned a spot on Nashville

radio station WSM’s popular Grand Ole Opry program. The group’s

appearances on the Opry brought Monroe national recognition.

Throughout the war years, Monroe began to put together the major

musical elements of bluegrass, including his trademark high-tenor

singing, the distinctive rhythm provided by his ‘‘chopping’’ mando-

lin chords, and a repertoire of old-timey and original tunes.

But it was not until Monroe formed a new version of the Blue

Grass Boys at the end of World War II that the classic bluegrass sound

finally emerged. In 1945, he added guitarist Lester Flatt, fiddler

Chubby Wise, bass player Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts), and

banjoist Earl Scruggs. Of these, the most important was Scruggs, who

at the age of 20 had already developed one of the most distinctive

banjo styles ever created, the Scruggs ‘‘three-finger’’ style. This

playing style, accomplished by using the thumb, forefinger, and index

fingers to pick the strings, allowed Scruggs to play in a ‘‘rolling’’

style that permitted a torrent of notes to fly out of his banjo at

amazingly fast speeds. This style has since become the standard banjo

playing style, and despite many imitators, Scruggs’s playing has

never quite been equaled. Scruggs, more than anyone else, was

responsible for making the banjo the signature instrument in blue-

grass, and it is the Scruggs banjo sound that most people think of

when bluegrass is mentioned. According to country music historian

Bill Malone, with this new band Monroe’s bluegrass style fully

matured and became ‘‘an ensemble style of music, much like jazz in

the improvised solo work of the individual instruments.’’