Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BOWLINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

329

kegeling Germans established New York as the country’s ‘‘bowling

capital.’’ Kegeling, unlike lawn bowling, was enjoyed by German

peasants; this reputation as a common-man’s sport has characterized

bowling throughout its American history. The first indoor alley,

Knickerbocker’s in New York City, was built in 1840; soon after this,

various establishments attracted the lower classes and genteel alike.

By the mid-1800s nine-pins became a widely played sport, and even

reached the midwest.

After the Civil War, more Germans began their own clubs with

bowling lanes, and tried to establish these as clean and family-

oriented places. Their efforts at constructing wholesome reputations

for their alleys were largely in vain, as most remained dark places

located in saloon basements alongside alcohol consumption, gam-

bling, and prostitution. Reformers’ attempts to outlaw nine-pins at the

end of the nineteenth century, it is fabled, caused alley owners to add

an extra pin.

John Brunswick founded the Brunswick Corporation in 1845,

which manufactured billiard tables and fine bar fixtures. In 1884

Brunswick added bowling equipment to his line, becoming the first

manufacturer of his kind in America. In 1914, he introduced the

Mineralite ball made of hard rubber and organized a world tour with

which to promote it; considered so revolutionary, the ball was put on

display at the Century of Progress Exposition in 1934.

At the turn of the century most bowling alleys were small

establishments that provided the working classes with much needed,

if less than wholesome, recreation. The cultural impetus toward

rationalization and organization at the end of the nineteenth century

also influenced bowling. By the 1880s and 1890s people attempted to

standardize the rules and the play, and to improve the reputation of

individual alleys and of the sport as a whole. Bowling associations

were formed in order to attract more female bowlers. In 1887 A.G.

Spalding, who was instrumental in forming baseball’s National

League, wrote Standard Rules for Bowling in the United States.

It was Joe Thum, however, who created what most resembled

twentieth-century lanes, and therefore became known as the ‘‘father

of bowling.’’ In 1886 he opened his first successful alley in the

basement of his Bavarian restaurant in New York City. In 1891 he

built six lanes in Germania Hall, and in 1901 he opened the world’s

most elegant alley, ‘‘The White Elephant,’’ which featured state-of-

the-art lanes, electric lighting, and extravagant interior design in order

to redefine bowling as a genteel sport, and to compete with other

upper-class recreational areas of the time, like theaters and opera houses.

Thum also encouraged other smaller alley owners to adopt

standard rules. By the mid-1890s the United Bowling Clubs (UBC)

was organized and had 120 members. The American Bowling Con-

gress (ABC), bowling’s official governing body, was established in

1895, and held its first tournament in 1901. Women’s bowling

evolved alongside men’s, with the first women’s leagues appearing in

1907, and the Women’s International Bowling Congress (WIBC)

instituted in the 1910s. These bodies continued to push for standard-

ized rules and regulations for the sport, and also maintained the quest

to improve the image of the sport, which was still considered a dirty

and tawdry pastime chiefly for lower-class gamblers and drinkers.

The various bowling organizations were successful in determin-

ing standards for bowling play and the alleys themselves, which have

remained constant throughout the twentieth century. Each lane con-

sists of a pin area, the lane itself, and the approach. Ten pins, each 15

inches high and 5 inches at their widest point and made of wood

covered with hard plastic, are arranged twelve inches apart in an

equilateral triangle at the far end of the lane. Each lane is 41 1/2 inches

wide, 62 5/6 feet long, made of maple and pine, and bordered by two

gutters. The balls themselves, which are rolled at the pins, are of hard

rubber or plastic, at most 27 inches in circumference, and between

eight and sixteen pounds. Each player’s turn consists of a ‘‘frame’’—

two chances to knock down all of the pins. Knocking down all ten pins

on the first try is a strike, while succeeding with two balls is a spare.

Because the scores for strikes and spares are compounded, a perfect

game in bowling is 300 points.

By 1920 there were about 450 ABC-sanctioned alleys, a number

which grew to about 2,000 by 1929. Prohibition led to the trend of

‘‘dry’’ alleys, and once again helped define the sport as one fit for the

entire family. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 caused an almost

immediate push by the breweries for sponsorship. Anxious to get their

company names in newspaper sports pages by subsidizing local

bowling leagues, beer makers such as Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, Stroh’s,

and Budweiser attached their names to teams and individual bowlers,

forever cementing bowling’s reputation as a working-class sport.

Beer-drinking has remained an activity stereotypically associated

with bowling; among some players, the fifth frame has been dubbed

the ‘‘beer frame’’ and requires the lowest scorer in that frame to buy a

round of drinks for the other players.

Also after Prohibition, bowling lanes shifted in style from the

fancy Victorian venues and the seedier saloon locales to more

independent establishments that embraced the modern Art Deco

style. As bowling chronicler Howard Stallings has noted, ‘‘The

imagery and implements of bowling—the glossy, hard ball speeding

down a super-slick blonde, wooden surface, smashing into mathe-

matically arranged, streamlined pins—meshed perfectly with the

era’s ’need for speed,’ the aerodynamic zeitgeist, if you will.’’

Throughout its history, bowling has remained an affordable

sport for the common person. Alleys were located close by, the

special shoes needed could be rented, balls were provided by the

alley, and the fee for the games themselves was very affordable. It is

no surprise, then, that the sport prospered during the Depression and

war years, remaining a viable respite for people taxed by financial and

emotional burdens. At this time larger institutions also noticed the

potential healthful benefits of bowling, causing many alleys to be

built in church basements, lodge halls, student unions, industrial

plants, and even private homes.

The late 1940s through the 1960s proved to be the golden age of

bowling. In 1947 Harry Truman installed lanes in the White House,

helping bowling’s continual legitimating process among the various

classes even more, and defining it as a true national pastime. The same

year also saw the first bowling telecast, which helped popularize the

sport even more—ABC membership for that year was 1,105,000 (a

figure which would grow to 4,575,000 in 1963), and sanctioned

individual lanes numbered 44,500 (up to 159,000 by 1963). By 1949,

there were over 6,000 bowling centers nationwide. Television proved

the perfect medium for bowling because games were easy to shoot

and inexpensive to produce. They also fostered the careers of famous

bowlers like Don Carter, Earl Anthony, and Dick and Pete Weber.

Described as a ‘‘quiz show with muscle,’’ the televised bowling

program was ubiquitous in the 1950s, and included such telecasts as

Celebrity Bowling, Make That Spare, Bowling for Dollars, ABC’s

Pro Bowler’s Tour, and Jackpot Bowling, hosted by Milton Berle. By

1958 bowling had become a $350,000,000 industry.

Other factors also contributed to bowling’s wide-scale success in

the 1950s. The automatic pinsetter patented by Gottfried Schmidt and

purchased by AMF (American Machine and Foundry) in 1945, was

BOXING ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

330

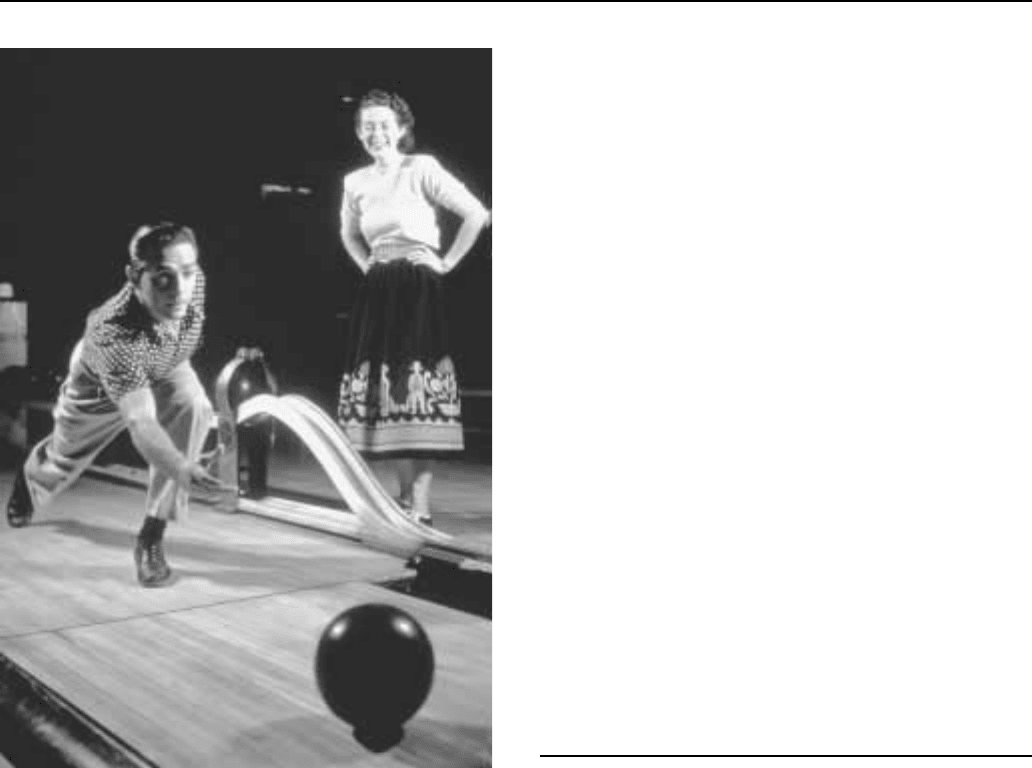

An example of bowling.

first put into use in 1952, when the first fully operational system was

installed. This marked a revolution in alley technology, because

owners and players were no longer reliant on the ‘‘pin boys’’ to reset

the pins manually. These young workers, who had the dangerous job

of standing at the end of the alley dodging balls and careening pins,

were often ill-behaved delinquents and troublemakers. The automatic

pinsetter made pin resetting and ball retrieval safer, faster, and

reliable, making the game itself more fluid. Brunswick produced their

first pinsetter in 1955, and also added air conditioning to their

new alleys.

In the late 1950s the alleys themselves became more luxurious,

incorporating the latest design trends and materials, with tables and

seats made of brightly-colored Formica and looking like something

from outer space. A 1959 issue of Life magazine described the

modern bowling alley as an ‘‘all-purpose pleasure palace.’’ Indeed,

much like drive-in theaters, they tried to be all things for all family

members, offering services like child care and beauty parlors, and

containing carpeted lobbies, restaurants, cocktail lounges, and bil-

liard tables. League play at this time was also at its peak, affording

regular and organized opportunities for various groups to form teams

and bowl in ‘‘friendly competition.’’

As the 1960s came to an end, bowling alleys experienced the end

of their golden age. Bowling, still rooted in working-class ethics and

camaraderie, could not compete with larger and more exciting specta-

tor sports. This era also marked the decline of serious league play as

dedicated bowlers were growing older and younger potential bowlers

were opting for other recreational activities that took them out of

doors, like jogging and tennis. In spite of this decline, about 79

million people went bowling in 1993, and it was still the most popular

participatory sport in the United States, confirming its overwhelming

popularity only a few decades before.

As a sport with an indelible blue-collar image, bowling has

achieved the status of being an ‘‘everyman’s’’ sport, more synony-

mous with the American individual character than baseball. It is a

uniquely non-competitive sport in which people try to better their own

games more than beating others, who are usually friends or family

members. In the 1990s it experienced a resurgence in popularity due

to its ‘‘retro’’ image, and was a key element in the comedy movies

Kingpin and The Big Lebowski.

—Wendy Woloson

F

URTHER READING:

Harrison, Joyce M., and Ron Maxey. Bowling. Glenview, Illinois,

Scott, Foresman and Company, 1987.

Luby, Mort. The History of Bowling. Chicago, Luby Publishing, 1983.

Schunk, Carol. Bowling. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Company, 1976.

Stallings, Howard. The Big Book of Bowling. Salt Lake City, Gibbs

Smith, 1995.

Steele, H. Thomas. Bowl-O-Rama. New York, Abbeville Press, 1986.

Boxing

From John L. Sullivan, the last of the bare-knuckle champions

and the first of the gloved, to ‘‘Iron Mike’’ Tyson, the world’s

youngest heavyweight champion, the sport of boxing has been

consistently dominated by American fighters since the beginning of

the twentieth century. No other sport arouses the degree of fascination

and distaste as the ‘‘Noble Art,’’ nor has any sport been so consistent-

ly vilified. The ‘‘Sweet Science’’ is a world unto itself, rich in

tradition, ritual, and argot. Boxing generated a genre of Hollywood

film all its own and its implicit drama has been assayed in loving

detail by some of America’s greatest writers. While nowhere near as

popular now as they were before World War II, championship fights

still draw celebrities in droves to Las Vegas and Atlantic City for

often disappointing matches. Although a prize fight can still muster

some of the frisson of boxing’s heyday, by late in the century the sport

was in a period of decline, its status angrily contested.

Boxing traces its roots back to ancient Egypt, where hieroglyph-

ics dating to 4000 B.C. show Egyptian soldiers engaging in a

primitive form of the sport, their hands protected by leather straps.

From the Nile Delta, boxing spread along the trade routes, south to

Ethiopia and along the Aegean coast up to Cyprus, Crete, and the

Greek mainland. The Greeks took readily to boxing, including it in

their olympic contests, refining the leather coverings for the fist, the

cestus, and later, adding a spiked metal attachment to it—the murmex, or

limb piercer—that could inflict terrible, often fatal damage. Indeed,

bouts went on until one opponent died or was no longer able to stand.

Boxers figure heavily in Greek mythology. Theseus, who killed the

Minotaur, was a boxing champion as was Odysseus, hero of the

BOXINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

331

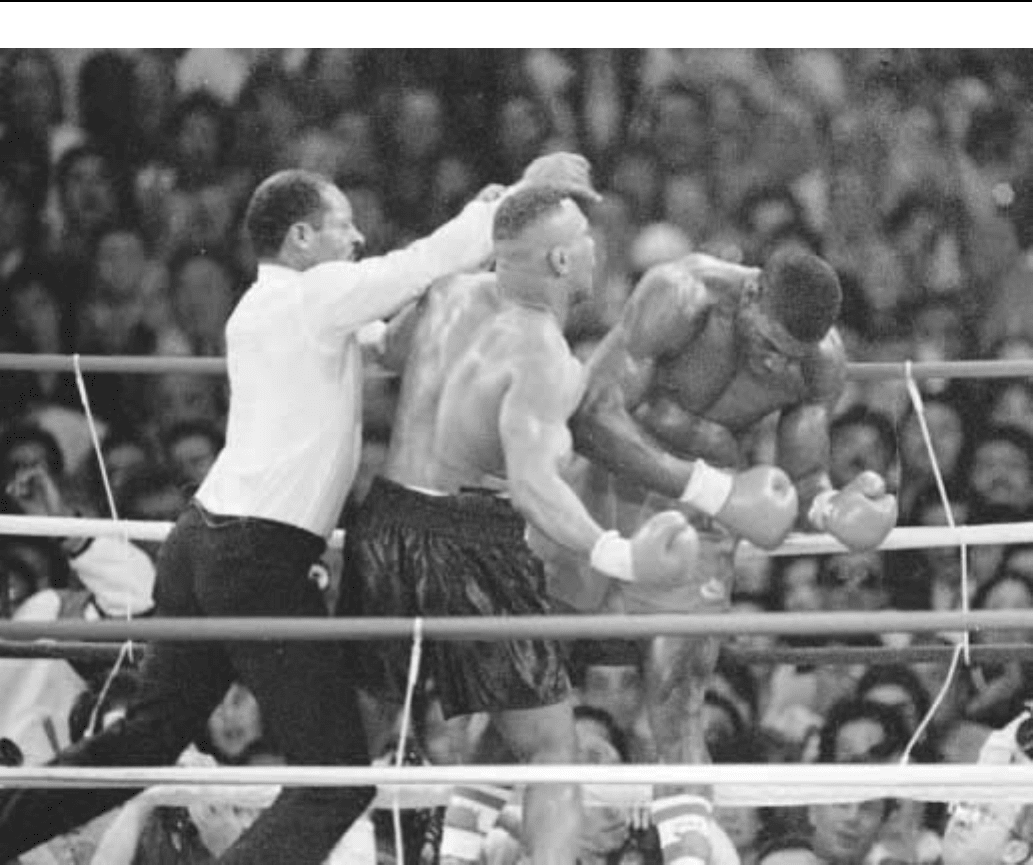

A heavyweight fight between champion Mike Tyson (center) and challenger Frank Bruno (right), 1989.

Trojan Wars and Homer’s Odyssey, and said to be undefeated in

the ring.

The Greek, Aeneas, brought the sport to Rome where it grew in

popularity and brutality until with the decline of the Roman Empire,

the decadent sport waned in popularity, and then disappeared for a

little over a millennium, resurfacing finally in seventeenth century

England. Its resurrection has been attributed to the England’s republi-

can form of government as well as the English people’s affection for

the backsword contest. For whatever reason, even before 1650 the

blind poet Milton, author of Paradise Lost, was advocating the

practice of boxing as indispensable to the education of the young

gentleman in his Treatise on Education. It was the eighteenth century

champion, Jack Broughton, who refined boxing into roughly the form

of the modern fight. In 1742, Broughton erected an amphitheater for

the promotion of bare-knuckle contests and to instruct contenders.

The following year he published a rule-book which explicated the

proper conduct of fighters and their seconds. Broughton also invented

the boxing glove, which he patterned after the Roman cestus, filling a

leather glove with soft batting. The glove was only used in training;

bouts were still fought with bare knuckles, and would continue to be

until the end of the nineteenth century.

Boxing first came to America by way of the aristocratic Old

South, as a result of that cultural fealty wealthy families paid to

England. According to John V. Grombach, author of Saga of Sock,

‘‘No family who took itself seriously, and these all did, considered its

children had acquired the proper polish unless they were educated in

England.... These youngsters went to prizefights and were taught

boxing in the fast and fashionable company of which they were

part.... Naturally, when these young dandies returned home they had

to show off all they had learned abroad, so they boxed against each

other. However, since distances between plantations were great . . .

they turned to their personal young slaves.’’ In fact, many of the early

professional boxers in America were slaves freed by their masters

after the latter had made a considerable fortune off their chattel. In the

early nineteenth century, for instance, Tom Molyneux, the son and

grandson of boxing slaves, was defeated by the British champion

Tom Cribb. Molyneux can be thought of as an anomaly of boxing

history, however, for it would be nearly a century before a black

BOXING ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

332

fighter, the heavyweight Jack Johnson, was allowed a shot at a

title fight.

Although Grombach assigns the beginning of modern boxing to

1700 A.D., the American era begins with John L. Sullivan, the last of

the bare-knuckle fighters. His reign as champion, from 1881 to 1892,

saw the introduction of the Marquis of Queensbury rules, which

called for gloves, weight classes, and three-minute rounds with one

minute intervals of rest in between. His losing bout to ‘‘Gentleman

Jim’’ Corbett was held under these new provisions. A flamboyant

personality, Sullivan was the first boxer to promote himself as such,

touring in theatrical productions between matches. Consequently, his

fights drew tremendous crowds; seemingly no one was immune from

the desire to witness a loudmouth’s disgrace. Typical of his time, he

was violently racist and refused to fight a black man, thus depriving

the worthy Peter Jackson, the Australian heavyweight champion, of a

chance at the title.

It would take Jack Johnson’s 1908 capture of the heavyweight

title from Tommy Burns to overcome the color barrier. After his 1910

defeat of James J. Jeffries, a white heavyweight champion who came

out of retirement to vanquish the Negro upstart, the novelist Jack

London publicly sought ‘‘a great white hope’’ to challenge Johnson.

Johnson’s victory was greeted with public outrage, inflamed by the

new champion’s profligate lifestyle. The moral character of a fighter

has always been a part of his draw. Johnson drank, caroused, and lived

openly with a white women, inflaming public sentiment already

predisposed against him. He was finally indicted on a morals charge,

and fled the country to avoid prosecution.

‘‘To see race as a predominant factor in American boxing is

inevitable,’’ writes Joyce Carol Oates in her thoughtful book On

Boxing, ‘‘but the moral issues, as always in this paradoxical sport, are

ambiguous. Is there a moral distinction between the spectacle of black

slaves in the Old South being forced by their white owners to fight to

the death, for purposes of gambling, and the spectacle of contempo-

rary blacks fighting for multi-million-dollar paydays, for TV cover-

age from Las Vegas and Atlantic City?’’ Over time, the parameters of

the racial subtext have shifted, but in 1937 when Joe Louis, a former

garage mechanic, won the heavyweight title from James J. Braddock,

his managers, leery perhaps of the furor Jack Johnson had caused,

carefully vetted their fighter’s public persona, making sure Louis was

always sober, polite, and far away from any white women when in the

public eye. The colorful ‘‘Sugar Ray’’ Robinson was a showman in

the Johnson tradition, but he, too, was careful not to overstep the

invisible line of decency.

Black boxers up to the present have been made to play symbolic

roles in and outside of the ring. Floyd Patterson, the integrationist

civil-rights Negro (who was, incidentally, forced to move from his

new house in New Jersey by the hostility of his white neighbors)

played the ‘‘great white hope’’ role against Sonny Liston, an unrepen-

tant ex-con street-fighter controlled by the mob. Muhammad Ali, who

refused to play the good Negro/bad Negro game, was vilified in the

press throughout the 1960s, unpopular among reporters as much for

his cocky behavior as for his religious and political militancy. Perhaps

race was never quite as crucial an issue in boxing following his reign,

but as recently as Mike Tyson’s bouts with Evander Holyfield in the

1990s, racial constructs were still very much a part of the attraction,

with Holyfield’s prominently displayed Christianity facing off in

a symbolic battle against the converted Muslim and convicted

rapist Tyson.

Class is as much a construct in modern boxing as race. Since

before the turn of the century, boxing has offered a way out of poverty

for young toughs. For 30 years after Jack Johnson’s reign, boxing

champions were uniformly white and were often immigrants or sons

of immigrants, Irish, Italian, or Eastern European. Boxing’s audience

was similarly comprised. The wealthy might flock to a championship

match at Madison Square Garden, but the garden variety bouts were

held in small, smoky fight clubs and appealed to either aficionados,

gamblers, or the working class. This provided up-and-coming fighters

with the chance to practice their skills on a regular basis, and more

importantly, made it possible for fighters, trainers, and managers to

make a marginal living off the fight game. As entertainment whose

appeal marginally crossed class lines, boxing’s status was always

contested, and the repeal of prohibition would only exacerbate

matters. Organized crime, looking for new sources of income to

replace their profits from bootleg liquor, took to fixing fights or

controlling the fighters outright (Sonny Liston’s mob affiliations

were out in the open, adding to his suspect moral rectitude). In the

1940s and 1950s, Jake LaMotta, for example, a contender from the

Bronx, was denied a chance at a championship bout until he knuckled

under to the demands of the local Mafia patriarch.

Nourished by the many boxing clubs in the New York area—the

undisputed capitol of boxing (to fighters and managers, out-of-town

meant anywhere not within the five boroughs of New York)—

controlled by the mob, the city was the center of a vital boxing culture.

Legendary gyms like Stillman’s Gym on Eighth Avenue were home

to a colorful array of boxers and managers. Fighters like Sugar Ray

Robinson, Jake ‘‘The Bronx Bull’’ LaMotta, and ‘‘Jersey Joe’’

Walcott were the heroes of the sport. Trainer Cus D’Amato, the

Aristotle of boxing, became a legend for discovering new talent

among the city’s underclass and resisting all incursions from the mob.

D’Amato specialized in saving up-and-coming delinquents from the

vagaries of the streets. He would discover heavyweight champion

Floyd Patterson and, towards the end of his life, Michael Tyson.

Legend has it he slept at his gym with a gun under his pillow. New

Yorker scribe A. J. Liebling covered the fights and the fighters,

leaving an especially vivid portrait of the boxing culture from this

time. In his portrait of Manhattan’s boxing milieu, he chronicled not

only the fights but the bars, the gyms, and the personalities that made

boxing such a colorful sport. Stillman’s (dubbed by Liebling the

University of Eighth Avenue), The Neutral Corner, and Robinson’s

Harlem Club, Sugar Ray’s, its walls festooned with collaged photos

of the flamboyant middleweight, all appear in Liebling’s many

boxing pieces. With his characteristic savoir-faire, he chronicled the

last great era of live boxing, or as some would say, the beginning of its

decline. Television had killed the small boxing clubs. Fighters who

showed promise were pushed up through the ranks too quickly, and

without the clubs, their inexperience was sadly apparent on the small

screen. Championship bouts still drew large crowds, but for the small

time managers, let alone boxers, television could not sustain the

vibrant culture so characteristic of boxing up to World War II.

Perhaps to fill this void, a string of boxing pictures started to

issue from Hollywood starting in the 1940s. Because of boxing’s

physicality, moral and psychological truths can be presented in stark

contrast. The drama is enacted on the boxer’s body, the repository of

truth and deception, and the fighter’s failure/success is inscribed upon

it. Aside from the standard boxing biopic (Golden Boy, 1939; Body

and Soul, 1947; Champion, 1949; Somebody Up There Likes Me,

1956; Raging Bull, 1980), two myths predominate: the triumph of the

underdog through perseverance, and the set-up, in which the boxer

(the innocent) is undone by the system. The Rocky films are perhaps

the best known of the former category, recasting the myth in an

BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

333

unabashedly sentimental light. Among the latter, Elia Kazan’s On The

Waterfront (1954), while not technically about boxing, manages to

depict the frustrating position of the boxer, dependent on the vagaries

of luck and the cooperation of organized crime for a successful career.

(Marlon Brando’s ‘‘I shoulda been a contender’’ speech immediately

entered the popular lexicon, as has his portrait of the paradox of the

gentle boxer, murderous in the ring, good-natured outside it). Other

films in the latter category include Requiem for a Heavyweight

(1962), The Harder They Fall (1956; based on the preposterous career

of Italian circus strong-man, the giant Primo Carnera), and The Set-

Up (1949), as is Martin Scorcese’s triumphant Raging Bull, perhaps

the most psychologically penetrating of any boxing film.

Boxing has also inspired some great writing. From the chronicler

of the English Prize Ring, Pierce Egan, author of Boxiana (frequently

quoted by Liebling) to Norman Mailer’s celebrated book of essays on

Muhammad Ali, boxing, being a wordless sport, invites others to

define it, to complete it. Hemingway, Ring Lardner, Budd Schulberg,

Nelson Algren, Jack London, and many others have written stories on

boxing, and some of the best American journalists, not necessarily

sports writers, have devoted considerable cogitation to the sport. The

locus of modern boxing writing is Muhammad Ali, who was as much

a cultural phenomenon as a sports figure, but this does not begin to

describe the reason why an anthology of essays was published

chronicling his career, nor that writers of the stature of a Tom Wolfe

or Hunter S. Thompson have felt it incumbent to weigh in on

the subject.

Perhaps it is because boxing is such a personal endeavor, so

lacking in artifice, that one cannot hide, neither from one’s opponent

or from oneself. ‘‘Each boxing match is a story—a unique and highly

condensed drama without words,’’ writes Joyce Carol Oates. ‘‘In the

boxing ring there are two principal players, overseen by a shadowy

third. The ceremonial ringing of the bell is a summoning to full

wakefulness.... It sets in motion, too, the authority of Time.’’ This

then, is boxing’s allure: In the unadorned ring under the harsh, blazing

lights, as if in an unconscious distillation of the blinding light of

tragedy, the boxer is stripped down to his essence. In other words,

boxing ‘‘celebrates the physicality of men even as it dramatizes the

limitations,’’ in the words of Oates, ‘‘sometimes tragic, more often

poignant, of the physical.’’

There can be no secrets in the ring, and sometimes painful truths

the boxer is unaware of are revealed before the assembled audience

and spectral television viewer. In the three bouts that destroyed Floyd

Patterson’s career—two against Sonny Liston, and one against Mu-

hammad Ali—Patterson was so demoralized, his faults and emotional

weaknesses set in such high relief, that it is a wonder he didn’t retire

immediately following the 1965 Ali bout (he was already known for

packing a fake beard in his luggage, the better to flee the arena). More

vividly, Mike Tyson’s frustrated mastication of champion Evander

Holyfield’s ear during their 1997 rematch revealed not only Tyson’s

physical vulnerability but confirmed an emotional instability first

hinted at after his 1993 rape conviction.

Boxing, it would seem, is a sport that runs through periodic

cycles. Recently, it has been taken up by women—who have begun to

fight professionally—and affluent professionals who have taken up

the sport not so much to compete as to train, a boxer’s regimen being

perhaps the most arduous of any sport. New gyms have sprung up to

accommodate this new-found popularity, but they are more often

franchises than owner-run establishments. Already a new generation,

nourished on Rocky pictures, seems to have taken to the arenas to

enjoy the live spectacle of two men—or women—slugging it out. But

in essential ways, boxing has changed. There are now four different

federations—the WBC, the IBF, the WBA, and the WBO—and 68

World Champions, as compared to eight in ‘‘the old days.’’ The cynic

would attribute this fragmentation to economics: the more champion-

ship bouts, the more pay-per-view cable TV profits (the money from

box-office revenues comprises only a small fraction of the net profit).

Consequently, championship bouts have lost much of their inherent

drama inherent in a unified championship match, and the quality of

the matches have also decreased, since fighters have so few chances

to practice their craft.

Regardless of the devitalizing effects of cable television and

multiple boxing federations, boxing still retains a powerful attraction.

No sport is so fraught with metaphorical implications, nor has any

sport endured for quite so long. Boxing, as Oates points out, aside

from going through periods of ‘‘crisis’’ is a sport of crisis. Its very

nature speaks to someplace deep in our collective psyche that

recognizes the paradoxical nature of violence. Managers and promot-

ers may cheat and steal, matches may be fixed, but when that rare bout

occurs where the fighters demonstrate their courage, skill, and intelli-

gence, the sport is redeemed. Boxing is a cyclical sport, rooted

ultimately in the vagaries of chance. When will a new crop of talented

contenders emerge? That is something no one can predict. The public

awaits the rising of new champion worthy of the name, and the

promoters await him just as eagerly.

—Michael Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Brenner, Teddy, as told to Barney Nagler. Only the Ring Was Square.

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1981.

Delcourt, Christian. Boxing. New York, Universe, 1996.

Grombach, John V. The Saga of Sock: A Complete Story of Boxing.

New York, A.S. Barnes and Company, 1949.

Isenberg, Michael T. John L. Sullivan and His America. Urbana,

University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Liebling, A. J. A Neutral Corner. San Francisco, North Point

Press, 1990.

———. The Sweet Science. New York, Penguin Books, 1982.

Lloyd, Alan. The Great Prize Fight. New York, Coward, McCann &

Geoghegan, 1977.

Oates, Joyce Carol. On Boxing. Hopewell, The Ecco Press, 1994.

Schulberg, Budd. Sparring with Hemingway: And Other Legends of

the Fight Game. Chicago, I.R. Dee, 1995.

Weston, Stanley, editor. The Best of ‘‘The Ring: The Bible of

Boxing.’’ Revised edition. Chicago, Bonus Books, 1996.

Boy Scouts of America

The young people, dressed in uniform, seem part of a tradition

from a bygone era. Some cheer as the small, homemade go-carts spin

down the track; others struggle to make the perfect knot or pitch in to

help clean up the local park. They serve as a emblem of the

conformity of the 1950s and the desire to connect our children with

BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

334

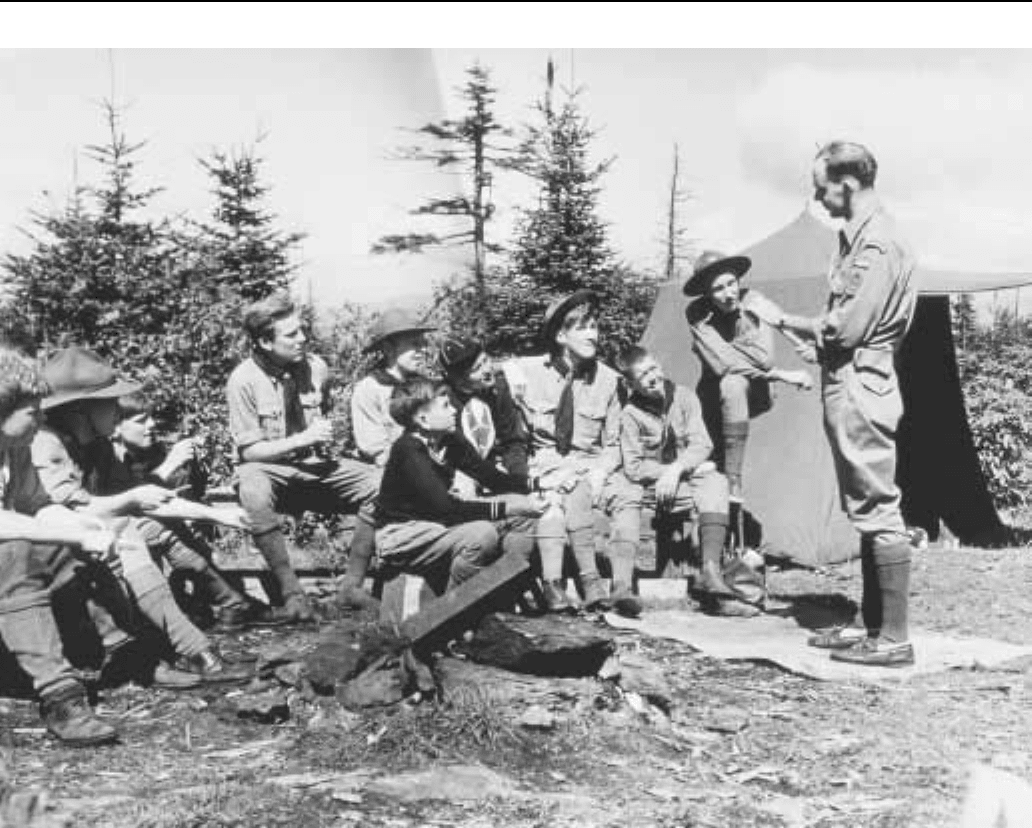

A group of Boy Scouts with their Scout Master.

‘‘rustic’’ ways of life. In the final judgment, though, these contempo-

rary kids are simply having fun while learning valuable lessons. In an

era when scouting has needed to redefine its mission, many of its

basic initiatives still possess great worth to society.

Even though contemporary organizations have appealed to boys

and girls, scouting began as a gendered organization. At the dawn of

the twentieth century, an American boy’s life was often either idyllic

or full of drudgery, depending on his family’s circumstances. During

the decade before the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) were founded in

1910, the families of a handful of industrialists lived sumptuously

while the vast majority of the population lived much more simply.

The Gilded Age of the nineteenth century had brought wealthy

Americans a genuine interest in rustic living and the outdoors. Many

wealthy urbanites began sending children to summer camps that

could provide their children with a connection to the culture of

outdoors. Theodore Roosevelt and others began organizations such as

the Boone and Crockett Club or the Izaak Walton League. Each group

had an offspring for younger male members, with Sons of Daniel

Boone proving the most popular. Neither, however, truly sought to

reach young men of all economic classes. Ernest Thompson Seton,

artist and wildlife expert, founded the Woodcraft Indians in 1902.

Interestingly, he chose to unveil the group through articles in the

Ladies Home Journal. Shortly afterwards, Seton became the first

Chief Scout of BSA when it was established by Robert Stephenson

Smyth Baden-Powell.

Early scouting undoubtedly fostered male aggression; however,

such feelings were meant to be channeled and applied to ‘‘wilder-

ness’’ activities. Many scholars see such an impulse as a reaction to

the 1893 speech by historian Frederick Jackson Turner when he

pronounced the frontier ‘‘closed.’’ Turner and many Americans

wondered how the nation could continue to foster the aggressive,

expansionist perspective that had contributed so much to its identity

and success. The first BSA handbook explained that a century prior,

all boys lived ‘‘close to nature.’’ But since then country had under-

gone an ‘‘unfortunate change’’ marked by industrialization and the

‘‘growth of immense cities.’’ The resulting ‘‘degeneracy’’ could be

altered by BSA leading boys back to nature.

Roosevelt’s personality guided many Americans to seek adven-

ture in the outdoors and the military. BSA sought to acculturate young

men into this culture with an unabashed connection to the military.

Weapons and their careful use, as well as survival skills, constructed

the basis for a great deal of the activities and exercises conducted by

BRAENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

335

Baden-Powell, a major-general in the British Army. The original Boy

Scout guidebook was partly based on the Army manual that Baden-

Powell had written for young recruits. World War I would only

intensify youth involvement in scouting. The perpetuation of scouting

during the post-1950 Cold War era, however, is more attributable to a

national interest in conformity and not in militancy. It was only during

the early years that such associations with the military were

openly fostered.

Seton visited Baden-Powell in London in 1906, where he

learned about the Boy Scouts organization. Upon returning to the

United States, Seton began gathering support for an organization that

would ‘‘offer instruction in the many valuable qualities which go to

make a good Citizen equally with a good Scout.’’ The first Boy Scout

manual, Scouting for Boys, contained chapters titled Scoutcraft,

Campaigning, Camp Life, Tracking, Woodcraft, Endurance for Scouts,

Chivalry, Saving Lives, and Our Duties as Citizens. In 30 years the

handbook sold an alleged seven million copies in the United States,

second only to the Bible.

Working in cooperation with YMCA (Young Men’s Christian

Association), the BSA was popular from its outset in 1908. This

coordination was particularly orchestrated by William D. Boyce, who

guided the official formation of BSA in 1910. The BSA network

spread throughout the nation, and in 1912 included Boys’ Life, which

would grow into the nation’s largest youth magazine. Most educators

and parents welcomed scouting as a wholesome influence on youth.

Scores of articles proclaimed such status in periodicals such as

Harper’s Weekly, Outlook, Good Housekeeping, and Century.

Within the attributes derived from scouting were embedded

stereotypes that contributed to gender roles throughout the twentieth

century. Girl scout activities followed scouting for males, yet pos-

sessed a dramatically different agenda. Instruction in domestic skills

made up the core activities of early scouting for females. Maintaining

a connection with nature or providing an outlet for aggressions did not

cohere with the ideals associated with the female gender in the early

twentieth century. Such shifts would only begin after 1950; however,

even today, scouting for girls is most associated with bake sales and

the famous girl scout cookies. Still, scouting for both genders has

become similar, particularly emphasizing outdoor experiences

Contemporary scouting has changed somewhat, but it also

maintains the basic initiatives of early scouting. Most attractive to

many parents, scouting involves young people in community out-

reach activities. In an era when many families find themselves in

suburban developments away from community centers or frequently

moving, scouting offers basic values including service to others in the

community. The proverbial scout aiding an older woman across a

street may be a thing of the past, but scouts still work in a variety of

community service tasks. These values also continue to include

patriotism under the rubric ‘‘service to God and country.’’ The

inclusion of God, however, has not held as firmly in contemporary

scouting. Some parents have refused to let their children participate in

any of the quasi-religious portions of scouting, which has led to a few

scouts being released. Over BSA’s century of life, though, the basic

values of scouting have remained strong, while activities have been

somewhat modified. Though well known activities such as the

‘‘pinewood derby’’ and ‘‘jamborees’’ continue, the culture of scout-

ing has begun to reflect a changing generation. While its popularity

does not near that of the earlier era, the culture of scouting continues

to help young Americans grow and mature into solid citizens.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven,

Yale University Press, 1982.

Peterson, Robert W. Boy Scouts: An American Adventure. New York,

American Heritage, 1985.

75 Years of Girl Scouting. New York, Girl Scouts of the U.S.A., 1986.

Bra

The brassiere, more commonly referred to as ‘‘the bra,’’ was one

of the most influential pieces of women’s apparel in the twentieth

century. As an item of underwear that was never intended to be seen in

public, it shaped women’s breasts and presented them to the public in

ways that responded to and reflected ideas about women’s bodies and

their roles in American culture. That the bra went through so many

radical changes in design shows how important breasts themselves

were in a culture that eroticized, idolized, and objectified them.

Until the first decade of the twentieth century, women relied on

the corset as their main undergarment. Rigid, tightly laced to form a

‘‘wasp waist,’’ and covering the area from the crotch to the shoulders,

the corset was an oppressive article that made it difficult for women to

breathe, bend over, or even sit down. In the first decade of the

twentieth century, however, breasts were liberated from the corset

through the invention of a separate garment which would provide

them shape and support. The brassiere, first sold in France in 1907,

allowed women to be more comfortable but also meant that society

began considering breasts more as objects—almost as separate enti-

ties from women’s bodies themselves. The ‘‘ideal’’ breast shape

changed with developing technologies, fashions, and perceived roles

of women.

New York debutante Mary Phelps Jacobs patented the first bra in

the United States in 1914, a device which supported the breasts from

shoulder straps above rather than pressure from below, as the corset

had done. Jacobs eventually sold the rights to her ‘‘Backless Bras-

siere’’ to the Warner Brothers Corset Company. In 1926, Ida Rosenthal

and Enid Bissett, partners in a New York dress firm who did not like

the 1920s flapper look that preferred flat chests and boyish figures,

sewed more shapely forms right into the dresses they made, and

eventually patented a separate bra ‘‘to support the bust in a natural

position’’; they went on to found the successful Maiden Form

Brassiere Company.

By the 1930s the separate bra and underpants had become the

staples of women’s undergarments. In this same decade the Warner

Company popularized Lastex, a stretchable fabric that allowed wom-

en even more freedom from their formerly constrictive underclothing.

In 1935 Warner’s introduced the cup sizing system (A through D),

which was very quickly adopted by all companies, and assumed that

women’s bodies could easily fit into distinct and standard catego-

ries of size.

Rationing during World War II meant that women had to forego

fancy bras of the latest materials, but after the war they reaped the

benefits of wartime technology. Bras appeared in nylon, rayon, and

parachute silk. In addition, they incorporated ‘‘whirlpool’’ stitching

BRA ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

336

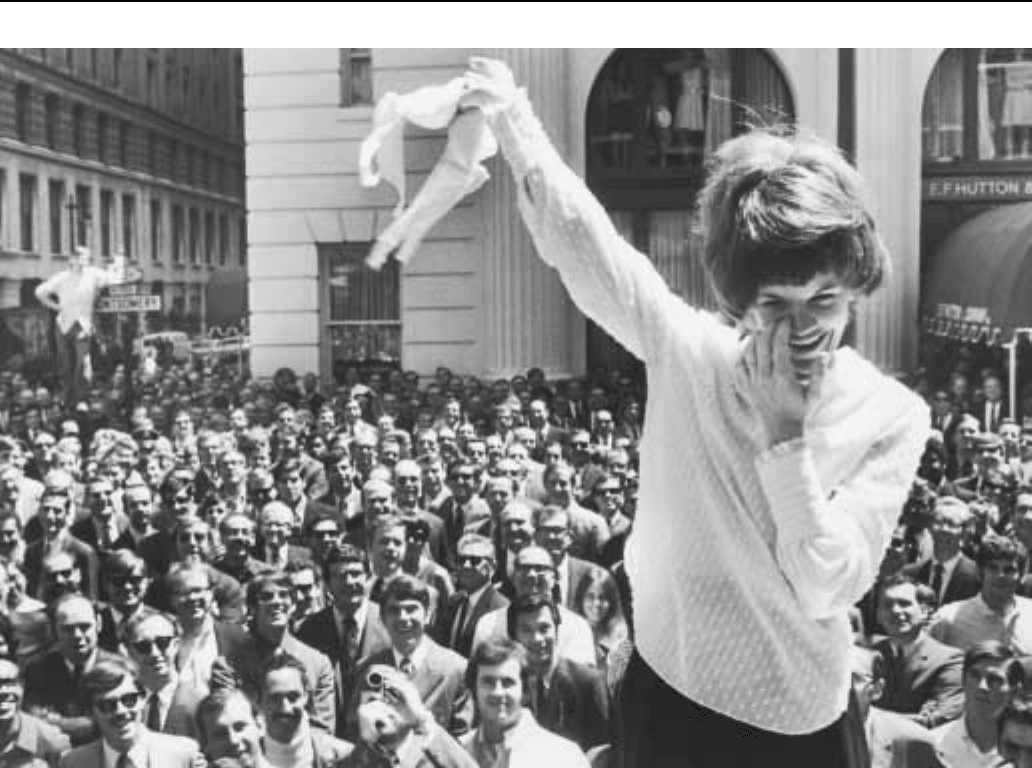

A woman displays her divested bra during Anti-Bra Day in San Francisco, 1969.

which formed the individual cups into aggressive cones. Maiden

Form’s 1949 Chansonette, more popularly known as the ‘‘bullet

bra,’’ became its most popular model, and was a clear example of how

women’s bodies were shaped by the aesthetics and mindset of the

time. After the war, jutting breasts recalled the designs of weaponry

like rockets used in the conflict, and also symbolized society’s desire

for women to forego their wartime jobs and retreat back into the

homes to become capable wives and mothers. As if to circumscribe

their roles even more, in 1949 Maiden Form also inaugurated its long-

lasting ‘‘Dream’’ advertising series, which showed women in numer-

ous situations ‘‘dreaming’’ of various accomplishments, clad only in

their Maidenform bras. In the 1950s Playtex began the first bra and

girdle advertising on television, but the bras were modeled on plastic

bust forms. It was not until the 1990s that television allowed bras to be

shown on live models.

While the shape and relative status given to women’s breasts in

the 1950s reflected women’s domestication, their liberation in the

1960s equally expressed women’s newly perceived freedom. More

and more women saw their breasts as items packaged to suit men’s

tastes. Acting against this, many went braless and preferred the

androgynous appearance of their flapper grandmothers celebrated in

the waif-like look of models like Twiggy. Brassiere companies made

consolations to accommodate this new sensibility as well. Their

designs became relaxed, giving breasts a more ‘‘natural’’ shape than

their pointed precursors. Rudi Gernreich, most famously known for

his topless bathing suit, designed the ‘‘no-bra bra’’ in 1965, which

was meant to support the breasts but to be invisible. In 1969 Warner’s

finally caught up with this trend, designing and producing their own

Invisible Bra.

By the late 1960s the bra itself became an important political

symbol. The first ‘‘bra burning’’ demonstration happened at the 1968

Miss America Pageant, when poet Robin Morgan and members of the

Women’s Liberation Party picketed the event and threw their bras in a

trash can as a gesture against women’s objectification. That they

actually burned their bras at this demonstration was a myth started by

a reporter who likened the event to flag-burning and other incendiary

activities of popular protest. After that, bra burning became an overt

statement of feminism and women’s liberation, and ‘‘bra burners’’ a

derisive label for activist women involved in the struggle for equal rights.

By the 1980s and 1990s, America saw a return to more delicate

lingerie, hastened by the opening and rapid franchising of Victoria’s

Secret lingerie stores beginning in 1982. As in the 1950s, breasts were

seen as something to display—status symbols for the women who

possessed them and the men who possessed the women. In 1988 the

push-up bra returned as a less-than-permanent alternative to breast

enhancement surgery, which was just becoming popular. The value of

BRADBURYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

337

large breasts during the late 1980s and through the 1990s was seen

alternatively as a positive embodiment of women’s new power and

assertiveness in the business world and a backlash against feminism

that continued to objectify women and their body parts.

Madonna encapsulated these tensions in her 1991 Truth or Dare

film, a documentary showing a behind-the-scenes glimpse of her

performances. In it, she sported a pin-striped business suit whose slits

opened to reveal the cups of a large, cone-shaped pink bra designed by

Jean-Paul Gaultier. The juxtaposition of the oversized bra cups,

dangling garter belts, and business suit presented a parody of tradi-

tional gender roles. Her use of these symbols best expressed the

power of clothing—layers which could be seen and those which could

not, equally—and the power of women to present their bodies in ways

that either acquiesced to or subverted the current power dynamics

between the genders.

—Wendy Woloson

F

URTHER READING:

Ewing, Elizabeth. Dress and Undress, A History of Women’s Under-

wear. New York, Drama Book Specialists, 1978.

Fontanel, Beatrice. Support and Seduction: The History of Corsets

and Bras. New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1997.

Yalom, Marilyn. A History of the Breast. New York, Alfred A.

Knopf, 1997.

Bradbury, Ray (1920—)

Although well-known to and beloved by many as a leading

writer of science fiction, Ray Bradbury is a far more complicated

subject than most may realize. In the world of science fiction, he is an

object of admiration and dismay, while outside the genre, he is an

enigmatic figure who blends a lyricism, nostalgia, and scientific

possibility in ways that surprise and delight.

Ray Bradbury was born on August 22, 1920 in Waukegan,

Illinois, the third son of Spaulding Bradbury and Esther Marie

Moberg Bradbury. By age eight, Bradbury had discovered pulps like

Amazing Stories, which he began to read voraciously. His father

suffered the trials of most Depression-era Americans, moving his

family from and back to Waukegan three times, before finally settling

in Los Angeles in 1934. That year, Bradbury began to write in earnest,

publishing in an amateur fan magazine in 1938 his first story,

‘‘Hollerbochen’s Dilemma.’’ In 1939 Bradbury started publishing his

own fan magazine, Futuria Fantasia; in 1941 he began attending a

weekly writing class taught by science fiction master Robert Heinlein.

In 1941, Bradbury, with coauthor Henry Hasse, published his

first paid short story, ‘‘Pendulum,’’ in Super Science Stories. Up until

this time, Bradbury had been selling papers, a job he gave up in 1942

in order to write full-time. That year he wrote ‘‘The Lake,’’ the first

story written in the true ‘‘Bradbury style.’’ Three years later, he began

to publish in the better magazines, at which point various short stories

started to receive national recognition: ‘‘The Big Black and White

Game’’ was selected for the Best American Short Stories 1945;

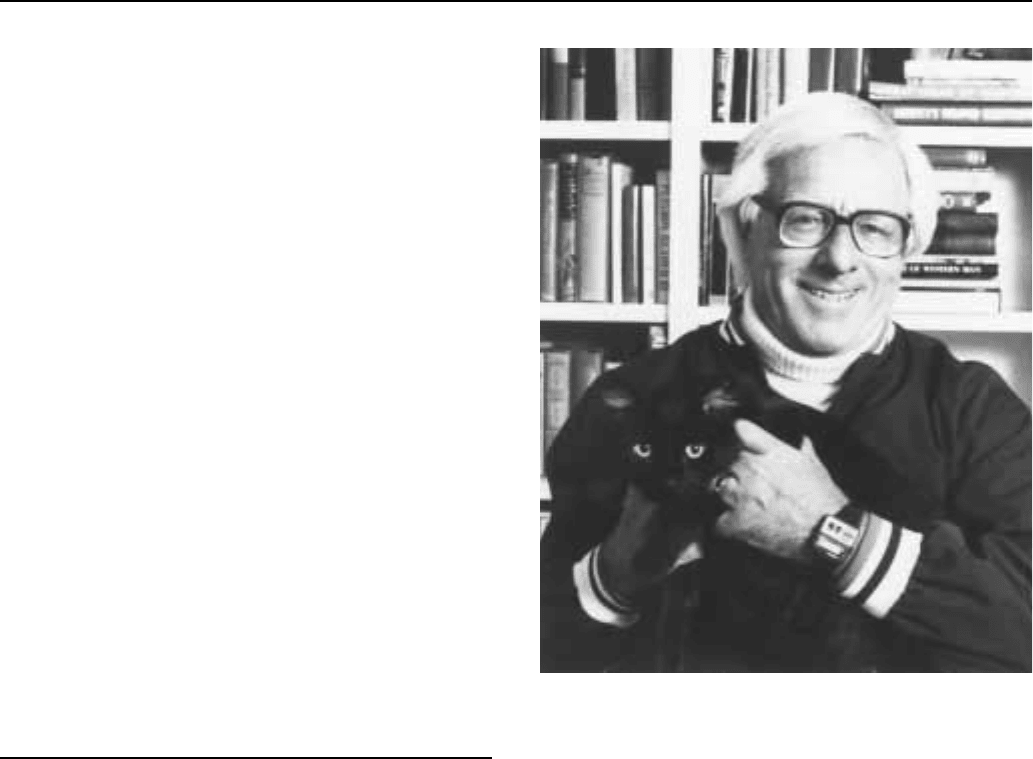

Ray Bradbury

‘‘Homecoming’’ for the O. Henry Awards Prize Stories of 1947;

‘‘Powerhouse’’ for an O. Henry Award in 1948; and ‘‘I See You

Never’’ for Best American Short Stories 1948. In 1949, Bradbury was

selected by the National Fantasy Fan Federation as best author in

1949. Meanwhile, as he collected more accolades, his personal life

also took a fateful swing. In 1947 he married Marguerite McClure, by

whom he had four daughters.

Bradbury’s major breakthrough came in 1950 with The Martian

Chronicles, his story cycle of Earth’s colonization and eventual

destruction of its Martian neighbor. Although the quality of work

could easily have stood on its own merits, the strong praise it received

from Christopher Isherwood, Orville Prescott, Angus Wilson, and

Gilbert Highet established Bradbury as a writer of national merit.

Bradbury capitalized on the confidence expressed in his capacity to

imagine and write boldly with such seminal works as The Illustrated

Man (1951), Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Dandelion Wine (1957), Some-

thing Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and his many excellent short-

story collections.

Despite his apparent dominance of the science fiction field, a

number of science fiction writers thought the prominence given him

by literati unfamiliar with the genre was both unfair and uninformed.

Mutterings against Bradbury’s qualifications as a writer of ‘‘true’’

science fiction surfaced in 1951 with Edward Wood’s ‘‘The Case

Against Ray Bradbury,’’ in the Journal of Science Fiction. This was

followed by more substantive criticisms in James Blish’s The Issue at

Hand (1964) and Damon Knight’s In Search of Wonder (1967). In

general Blish and Knight, as well as Thomas M. Disch, Anthony

Boucher, and L. Sprague de Camp, would argue that Bradbury’s

BRADLEY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

338

lyrical approach to his topic emanated from a boyish nostalgia that

was, at heart, anti-scientific. Yet despite this vigorous criticism,

Bradbury fans have remained legion, while more than enough critics

have pointed out in return that such criticisms of Bradbury’s brand of

science fiction offer counter definitions of the genre so narrow they

denied it the very richness Bradbury’s own fictional style imparted to it.

Whatever the case may be, there is no sidestepping Bradbury’s

achievement as a writer. What he brings to science fiction is a vision

that transformed the steady-state prose of science—applied with so

much rigor to fiction by such writers as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C.

Clarke—into the lyricism of poetry. Kingsley Amis latches on to this

very quality in Bradbury’s prose when he writes in The Maps of Hell,

‘‘Another much more unlikely reason for Bradbury’s fame is that,

despite his tendency to dime-a-dozen sensitivity, he is a good writer,

wider in range than any of his colleagues, capable of seeing life on

another planet as something extraordinary instead of just challenging

or horrific.’’ By way of example consider the lyricality of the first

sentence in Bradbury’s description of the colonization of Mars in The

Martian Chronicles: ‘‘Mars was a distant shore, and the men spread

upon it in waves.’’ The artfulness of this one sentence, in which

‘‘shore’’ functions as a metaphor that resonates with ‘‘waves,’’ is a

small illustration of the poetic sensibility so often absent from the

common-sense anti-lyricism of postwar science fiction prose. In

short, Bradbury’s achievement was not to write science fiction in a

prose that was anti-scientific in spirit, but to create a subgenre of

science fiction that no longer treated poetry as a form of anti-science.

In short, Bradbury restored wonder to a genre that, without him, might

have proven dull, indeed.

Despite Bradbury’s association in the public mind with science

fiction, he has shown himself far too ambitious to be limited to a

single genre. Bradbury has successfully published in other genres. A

closer reading of much of his fiction will reveal tales that, despite their

lyrical and overimaginative tone, are, for all intents and purpose,

exemplars of light realist fiction, from his autobiographical novel

Dandelion Wine to the amusing ‘‘Have I Got a Candy Bar for You!’’

Bradbury also has taken stabs at writing drama, poetry, screenplays,

detective fiction, and even musical compositions. Although he has

never achieved the fame in these genres that he has in his science

fiction, there is little doubt the extension of his horizons as a writer

into these genres is the direct result of his continuing interest in

challenging his limits as a writer, just as he once challenged the limits

of science fiction itself.

—Bennett Lovett-Graff

F

URTHER READING:

Greenberg, Martin, and Joseph D. Olander, editors. Ray Bradbury.

New York, Taplinger, 1980.

Johnson, Wayne L. Ray Bradbury. New York, Frederick Ungar, 1980.

Mogen, David. Ray Bradbury. Boston, G. K. Hall, 1986.

Slusser, George Edgar. The Bradbury Chronicles. San Bernardino,

California, Borgo Press, 1977.

Toupence, William F. Ray Bradbury and the Poetics of Reverie:

Fantasy, Science Fiction, and the Reader. Ann Arbor, Michigan,

UMI Research Press, 1984.

Bradley, Bill (1943—)

A man of many talents, former New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley

perhaps best embodies the modern idea of a Renaissance man.

Bradley was an All-American basketball player at Princeton Univer-

sity, then went on to star with the New York Knicks after a stint in

Oxford, England as a Rhodes Scholar. Public service beckoned

Bradley and he won his first political office in 1978. Despite his

wealthy upbringing, Bradley has had to work hard for every success

in his life.

Born July 28, 1943, William Warren Bradley led a very organ-

ized and orderly childhood. He used to set aside four hours per day for

basketball practice. At the time of his high school graduation in 1961,

Bradley had scored 3,066 points and had been named to Scholastic

magazine’s All-American team twice. This success on the court

earned the attention of many prominent college coaches. Despite

offers from better known basketball powerhouses, Bradley chose to

attend Princeton University for its prestigious academic environment.

While starring at Princeton, Bradley made All-American three

times and was named National Association of Basketball Coaches

Player of the Year in 1965. One of Bradley’s highlights as an amateur

athlete was being a member of the gold medal winning American

Olympic team in 1964. After his career, several professional basket-

ball teams courted him for his services. Undeterred, Bradley chose

instead to pursue further study at Oxford University as a Rhodes

Scholar. While overseas, Bradley picked up the game again and saw

that he missed the athletic competition. After playing some for

an Italian professional team, he decided to join the New York

Knicks in 1967.

Professional basketball in the 1970s was not the kind of place

one would expect to find the intellectual Bradley. Teammates once

cool toward Bradley warmed to this Ivy League golden boy after they

realized his tremendous heart and work ethic. The Knicks went on to

win two NBA championships with Bradley playing integral roles in

both. He retired from the game in 1977 and was named to the

Basketball Hall of Fame in 1982.

With one career complete, Bradley turned down several business

offers and decided to pursue public service. The popular ex-Knick

won his first office in 1978, as he defeated Republican nominee

Jeffrey K. Bell for the New Jersey senatorial race, a seat he would

hold for three terms. Senator Bradley would champion issues like the

environment, education, and natural resources. He is perhaps best

known for the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which followed many of the

ideas on tax reform he laid out in his book, The Fair Tax. He was

briefly mentioned as a candidate for the presidency in 1988, then

again in 1992. A moderate Democrat, Bradley became respected and

revered throughout the senate and the nation. After his retirement

from the Senate, Bradley wrote Values of the Game in 1998, about the

life lessons he learned from basketball. Its publication again brought

Bradley to the media forefront and sparked rumors about his candida-

cy for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2000.

—Jay Parrent

F

URTHER READING:

Bradley, Bill. Time Present, Time Past—A Memoir. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

———. Values of the Game. New York, Artisan Press, 1998.