Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BROKAWENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

359

stage, following the success of such hit shows as Hair and The Boys in

the Band. A slew of musicals aimed at the younger generation,

incorporating new sounds of soft rock, followed with Stephen

Schwartz’s Godspell; Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s Jesus

Christ, Superstar; and the Who’s Tommy.

Meanwhile, avant-garde English and European dramatists such

as Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard, and Samuel Beckett brought their

radical new work to Broadway, even as a new kind of musical—the

concept musical, created by Stephen Sondheim in such hits as

Company and Follies—took the American musical theater in a whole

new direction. In this new form of a now time-honored American

tradition, narrative plot was superseded by songs, which furthered

serial plot developments. Other successful musicals of the type were

Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret and Chicago, and Michael Bennett’s

immensely popular A Chorus Line. During the 1970s, two producer-

directors who had begun working in the mid-1950s rose to increasing

prominence—Hal Prince, who was the guiding hand behind most of

Sondheim’s hit musicals; and Joseph Papp, whose Public Theatre be-

came the purveyor of New York’s high brow and experimental theater.

With the election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980 came an

era of conservatism in which Broadway became the virtual domain of

two men—composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and producer Cameron

Macintosh. Les Miserables, Cats, Evita, Phantom of the Opera,

Sunset Boulevard, and Miss Saigon were among the most successful

of the mega-musicals that took over Broadway for more than decade-

long runs. At the same time, however, Broadway was hit by the AIDS

epidemic, which from 1982 on began to decimate its ranks. Called to

activism by the apathy of the Reagan administration, the Broadway

community began to rally behind the gay community. In plays from

this period such as Torch Song Trilogy, Bent, M. Butterfly, and La

Cage aux Folles, homosexuality came out of Broadway’s closet for

good. And during the decade, increasing numbers of African-Ameri-

can actors, playwrights, and plays found a permanent home on the

Great White Way—from the South African-themed plays of Athol

Fugard, to the Pulitzer Prize-winning work of August Wilson, to

musicals about the lives of such musicians as Fats Waller and Jelly

Roll Morton. Broadway also became increasingly enamored with all

things English during the 1980s—from the epic production of Nicho-

las Nickleby, to the increasing presence of top English stars such as

Ian McKellen, to the increasing infatuation with the mega-musicals of

Andrew Lloyd Webber. But homegrown playwrights such as David

Mamet, Neil Simon, John Guare, and August Wilson nonetheless

continued to reap the lion’s share of the critic’s awards, including

Pulitzers, New York Drama Critic’s Circle, and Tonys.

In the late 1980s, a new phenomenon hit Broadway when

Madonna starred in Speed the Plow. In her critically acclaimed

performance, the pop and film star boosted Broadway box office sales

to such a degree that producers soon began clamoring to find

Hollywood stars to headline their plays. Throughout the 1990s, as the

mega-musicals of Andrew Lloyd Webber, and popular revivals such

as Damn Yankees, Guys and Dolls, and Showboat dominated the box

office, Broadway producers sought to make profits by bringing in big

names to bolster sales. Over the course of the decade, Hollywood stars

such as Kathleen Turner, Robert De Niro, Nicole Kidman, and Glenn

Close opened plays and musicals on the Great White Way. But the

district received a multi-billion dollar facelift when Disney came into

the picture, creating a showcase for its hugely successful musical

ventures such as Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King. But despite

what many critics saw as the increasingly commercialization and

suburbanization (playing to the tourists) of Broadway, powerful new

voices continued to emerge in the plays of Wendy Wasserstein (The

Heidi Chronicles), Tony Kushner (Angels in America), and Jonathan

Larson (Rent).

At the millennium, Broadway remains one of America’s singu-

lar contributions to both high and popular culture. Despite the

puissance of the film and television industries, the lure of the

legitimate theater remains a strong one. Broadway is at once a popular

tourist attraction and the purveyor of the tour de force that is the

theater. With its luminous 175-year history sparkling in America’s

memory, Broadway can look forward to a new century filled with

change, innovation, extravaganza, and excess—as the continuing

mecca of the American theater.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Atkinson, Brooks. Broadway. New York, Macmillan, 1970.

Baral, Robert. Revue: A Nostalgic Reprise of the Great Broadway

Period. New York, Fleet, 1962.

Blum, Daniel. A Pictorial History of the American Theatre, 1860-

1970. New York, Crown, 1969.

Brown, Gene. Show Time: A Chronology of Broadway and the

Theatre from Its Beginnings to the Present. New York, Macmil-

lan, 1997.

Churchill, Allen. The Great White Way: A Recreation of Broad-

way’s Golden Era of Theatrical Entertainment. New York, E.P.

Dutton, 1962.

Dunlap, David W. On Broadway: A Journey Uptown over Time. New

York, Rizzoli, 1990.

Ewen, David. The New Complete Book of the American Musical

Theater. New York, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970.

Frommer, Myrna Katz, and Harvey Frommer. It Happened on Broad-

way: An Oral History of the Great White Way. New York,

Harcourt, 1998.

Goldman, William. The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway. 1969.

Reprint, New York, Limelight Editions, 1984.

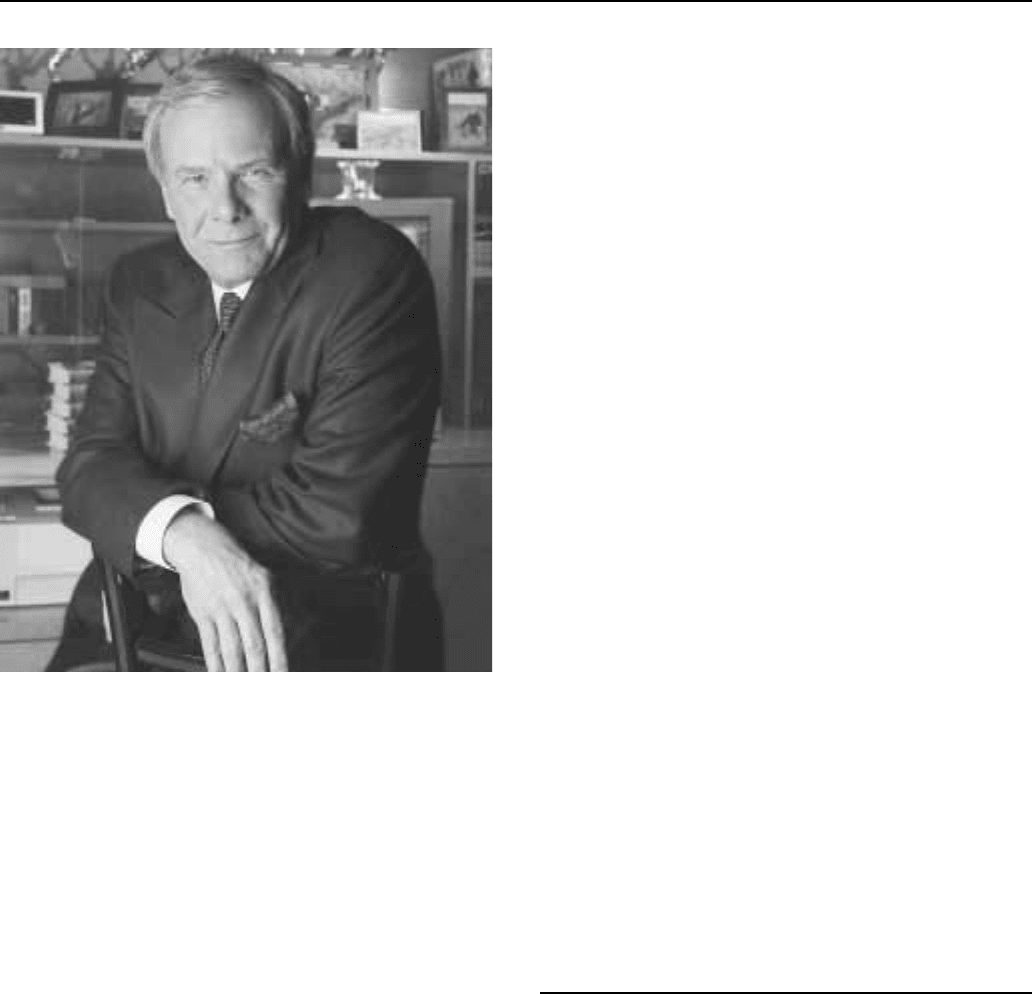

Brokaw, Tom (1940—)

As the anchor on NBC Nightly News, Tom Brokaw has a history

of getting there first in the competitive world of network newscasting.

He won the Alfred I. Dupont Award for the first exclusive one-on-one

interview with Mikhail Gorbachev in 1982, and was the only anchor

on the scene the night the Berlin Wall collapsed. He was also first to

report on human rights abuses in Tibet and he conducted an exclusive

interview with the Dalai Lama. From the White House to the Kremlin,

Brokaw has witnessed and reported on many of the twentieth centu-

ry’s biggest events.

BRONSON ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

360

Tom Brokaw

Born in Bristol, South Dakota, in 1940, the son of Anthony (Red)

and Jean Brokaw, he moved often as the family followed his father, a

construction worker, who built army bases and dams during the

1940s. His high school years were spent in Yankton, South Dakota,

where he first faced television cameras, appearing with a team of

students on Two for the Money, a network game show. While a

student he began his broadcasting career as a disc jockey on a

Yankton radio station and experienced one of his most embarrassing

moments. He was asked to interview a fellow student, Meredith Auld,

the new Miss South Dakota, whom he been dating. Tom was so

excited that he forgot to turn off the mike when the interview was

over, and all the Yankton listeners heard his sweet nothings broadcast

over the air.

He spent his freshman year at the University of Iowa, where he

says he ‘‘majored in beer and coeds.’’ He transferred to the University

of South Dakota and in his senior year began working at KTIV-TV in

Sioux City. After graduation, Tom married Meredith and applied for a

job at KMTV in Omaha. They offered him $90 a week, but Tom held

out for $100. Explaining why he needed the extra ten dollars, Tom

said, ‘‘I was the first college graduate in my family, just married, and

with a doctor father-in-law a bit unsure about his new son-in-law’s

future.’’ The station finally agreed to his terms on the condition that

he would never be given a raise. ‘‘And they never did,’’ he added.

In 1976 Tom moved into the big time in the Big Apple, replacing

Barbara Walters as the host of NBC’s Today Show. As he tells it, he

‘‘made a lot of friends’’ on the program, but he always knew that his

‘‘real interest was in doing day-to-day news exclusively.’’ After six

successful years on the morning show, he got his wish. He and Roger

Mudd began co-anchoring the NBC Nightly News after John Chancel-

lor retired in 1981. Within a year Mudd left the show, leaving Brokaw

as the sole anchor, and in 1982 his reputation rose in the wake of his

much publicized interview with Gorbachev.

Television critics have complimented Brokaw’s low key, easy-

going manner, comparing it with Dan Rather’s rapid-fire delivery and

Peter Jenning’s penchant for showmanship. He is particularly noted

for his political reporting, having covered every presidential election

since 1968 and having served as his network’s White House corre-

spondent during the Watergate era. He has also shown versatility in

other network assignments, heading a series of prime-time specials

examining some of the nation’s most crucial problems and acting as

co-anchor on Now with Tom Brokaw and Katie Couric.

Brokaw is also author of The Greatest Generation, a book

published in 1998 about his personal memories of that generation of

Americans who were born in the 1920s, came of age during the Great

Depression, and fought in World War II. He also has written for the

New York Times and the Washington Post, as well as Life Magazine.

He is best known, however, as the anchor who reported news from the

White House lawn, the Great Wall of China, the streets of Kuwait

during Operation Desert Storm, the rooftops of Beirut, the shores of

Somalia as the American troops landed, and, most famous of all, the

Berlin Wall the night it collapsed.

—Benjamin Griffith

F

URTHER READING:

Brokaw, Tom. The Greatest Generation. New York, Random

House, 1998.

Goldberg, Robert, and Gerald Jay Goldberg. Brokaw, Jennings,

Rather, and the Evening News. Secaucus, New Jersey, Carol Pub.

Group, 1990.

Jordan, Larry. ‘‘Tom Brokaw: A Heavyweight in a World of Light-

weights.’’ Midwest Today. February, 1995.

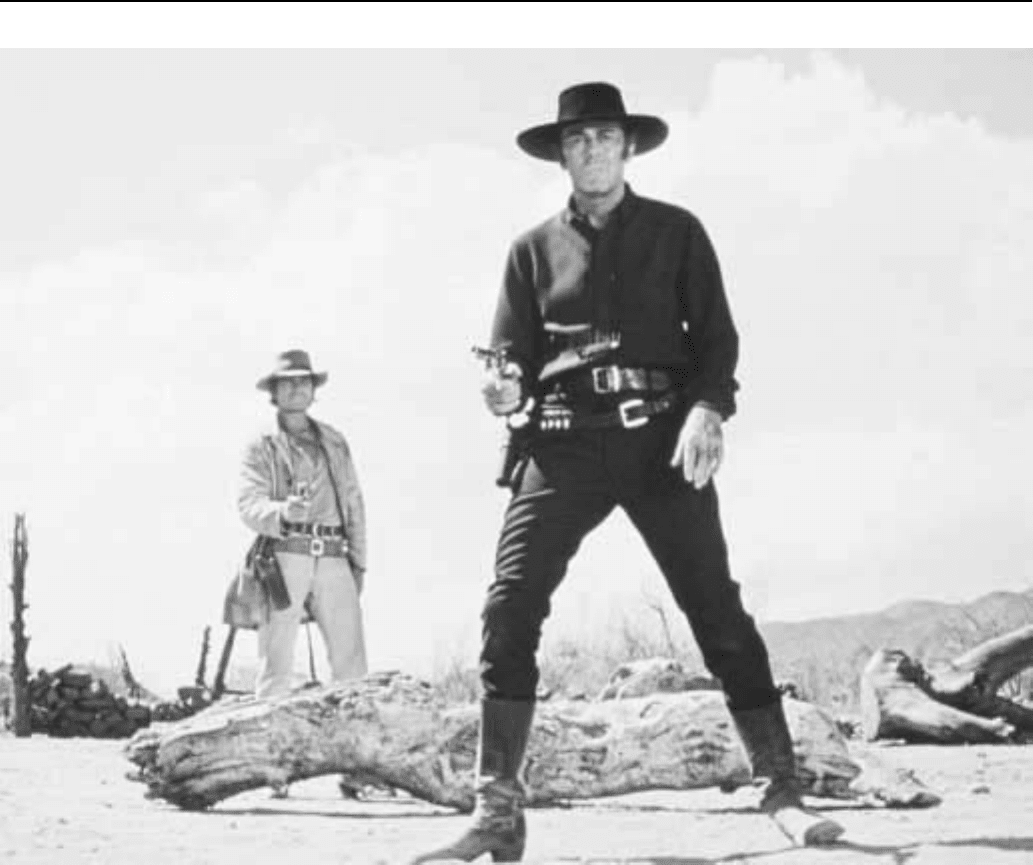

Bronson, Charles (1921—)

Charles Bronson is an American original. He is one of the

earliest and most popular tough guys. His lengthy career and dozens

of film credits make him a critical figure in the development of the

action-adventure film. His steely-eyed stare and his signature mous-

tache are themselves cultural icons. Although Bronson’s career began

on the stage and he once had his own television series, Bronson is

probably best known for his role as Paul Kersey in the Death Wish

series of films.

Born into grinding poverty as Charles Buchinski, the eleventh of

fourteen children, Bronson spent many of his formative years in the

coal mining town of Ehrenfield, Pennsylvania. After working to help

support his family in the mines and after serving his country as a tail

gunner on a B-9 bomber in World War II, Bronson moved to Atlantic

City. It was on the Jersey Shore that Bronson developed a taste for

acting while he roomed with fellow star-to-be Jack Klugman. Dreams

BRONSONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

361

Charles Bronson (left) and Henry Fonda in a scene from the film Once Upon a Time in the West.

of a career on the stage took Bronson to New York, Philadelphia, and

then to Pasadena, where he was spotted in 1950 playing the lead in the

play Command Decision.

From early on, Bronson was regularly cast in roles that fit his

arduous background. The post war American penchant for war films

and westerns was well suited for an actor with Bronson’s history and

image. Often times he was cast in the role of a gritty gunslinger or

rugged military man. Chief among such roles were his performances

in Machine Gun Kelly, The Dirty Dozen, The Magnificent Seven,

and as Natalie Wood’s punch-happy boyfriend in This Property

is Condemned.

Like many other American cultural phenomena, Bronson’s

career did not hit the big time until he won over European audiences.

Though he had been working steadily stateside, Bronson’s film career

got its biggest boost in the late 1960s, when he began working in

Europe. It was on the continent that his particular brand of American

charisma gained its first massive audience. His triumphs in Europe

rejuvenated Hollywood’s interest in Bronson and movie offers began

rolling in. His return to Hollywood was sealed with his role in the

thriller Rider on the Rain, which helped him win a Golden Globe

award for most popular actor.

Bronson’s film career culminated in 1974 with the release of

Death Wish, a movie about a mild mannered architect out to avenge

the murder of his wife. The movie has been credited with spawning an

entire genre of vigilante action films that draw on the frustrations of

the white middle class over urban crime and violence. Four sequels

would follow, each filmed in the first half of the 1980s when middle

class paranoia about drugs and crime was perhaps at an all-time peak.

Hollywood has often sought to replicate the sort of success Paramount

Pictures had with Death Wish. Dozens of films featuring ordinary-

man-turned-vigilante were churned out in the wake of this film. Key

among the early entrants into this subgenre was the Walking Tall

series of films. Perhaps the last and culminating film among these

angry-white-male films was the Michael Douglas flick, Falling

Down, which caused a great deal of controversy over its racially

charged depiction of whites, blacks, and Asians.

Charles Bronson is one of the few Hollywood actors who can

legitimately claim success in five decades. The evolution of his

BROOKLYN DODGERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

362

characters in the 1970s mark Bronson as one of the few actors to

successfully make the leap from westerns and war movies, into the

modern, urban-oriented action-adventure era. Though he is largely

considered a tough guy, he has played many other roles. Frequently

lost in popular memory was Bronson’s television series Man With A

Camera, which ran for two years in the late 1950s. Bronson has also

starred in several comedies, a musical, and some children’s fare. In

the 1990s Bronson has returned to the small screen and has had co-

starring roles opposite Christopher Reeves, Daniel Baldwin, and

Dana Delany in several made-for-TV productions, including Family

of Cops.

—Steve Graves

F

URTHER READING:

Downing, David. Charles Bronson. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1983.

Vermilye, Jerry. The Films of Charles Bronson. Secaucus, New

Jersey, Citadel Press, 1980.

The Brooklyn Dodgers

As the first team to break baseball’s color barrier with the

signing of Jackie Robinson in 1947, the Brooklyn Dodgers captured

America’s imagination during the 1950s, when they fielded a brilliant

team of men with nicknames like Duke, The Preacher, PeeWee, and

Skoonj. Unable to beat their cross-town rivals, the New York Yan-

kees, in World Series after World Series, the Dodgers became media

darlings—a team of talented, loveable, but unlucky underdogs. Cheered

on by their legendary loyal fans, the Dodgers finally beat the Yankees

in 1955, only to break Brooklyn’s heart by leaving for Los Angeles

two years later.

The borough of Brooklyn first fielded a baseball team in 1849, as

members of the Interstate League and then the American Association.

When Brooklyn joined the National League in 1890, the team was

nicknamed the Bridegrooms. The club won the pennant that year, but

by the end of the decade they had gone through six different managers

and had not won another championship. They had, however, acquired

a new nickname which finally stuck. As Roger Kahn notes in The

Boys of Summer, ‘‘Brooklyn, being flat, extensive and populous, was

an early stronghold of the trolley car. Enter absurdity. To survive in

Brooklyn one had to be a dodger of trolleys.’’ Thus, the team became

the Trolley Dodgers, which was later shortened to the Dodgers.

The Dodgers reclaimed the National League pennant in 1900,

only to see their championship team disperse when many of their

players joined the newly formed American League the following

year. The team’s ownership was also in a state of flux. But a young

employee of the team, Charles Ebbets, managed to purchase a small

amount of stock and gradually work his way up the ladder. Ebbets

eventually took over the team and secretly began buying up land in

Flatbush. In 1912, he built Ebbets Field, a gem of a ballpark, which

would provide baseball with its most intimate setting for over

40 years.

At first it seemed as if the new field would only bring the team

good luck. In 1916, the Dodgers won the pennant and then played in

its first World Series. Managed by the dynamic Wilbert ‘‘Uncle

Robbie’’ Robinson and led by the incredible hitting of Casey Stengel,

the Dodgers nonetheless lost the series to the Boston Red Sox that

year, whose team featured a young pitcher named Babe Ruth.

In 1920, the Dodgers took the pennant again, only to lose the

series to the Cleveland Indians. Then, for the next two decades, the

team fell into a miserable slump, despite being managed by such

baseball legends as Casey Stengel and Leo ‘‘the Lip’’ Durocher. But

the Dodgers never lost their loyal fans, for, as Ken Burns notes in

Baseball: An Illustrated History, ‘‘No fans were more noisily critical

of their own players than Brooklyn’s—and none were more fiercely

loyal once play began.’’ The team’s misfortunes were widely chroni-

cled in the press, who dubbed the team the ‘‘Daffiness Dodgers.’’ But

sportswriters were oddly drawn to the team, despite its losing ways,

and they portrayed the team as an endearingly bad bunch of misfits.

The team soon became known as ‘‘Dem Bums’’ and their dismal

record the subject of jokes in cartoons, newspaper columns, and even

Hollywood movies.

In 1939, Hall of Fame broadcaster Red Barber became the

distinctive voice of the Dodgers. He announced the first baseball

game ever televised in August 1939. Two years later, president Larry

McPhail and coach Leo Durocher had put together a great team,

described by Ken Burns as ‘‘noisy, hard-drinking, beanballing, and

brilliant on the basepaths.’’ They finally won another pennant, and

faced the Yankees in a World Series that would lay the groundwork

for one of baseball’s best rivalries. The Bronx Bombers, led by the bat

of Joltin’ Joe Dimaggio, won in five games. And, as Burns has

written, ‘‘The Brooklyn Eagle ran a headline that would become a

sort of Dodger litany in coming seasons: WAIT TILL NEXT YEAR.’’

Following the loss, the Dodgers brought in Branch Rickey from

St. Louis to be their new general manger. One of baseball’s greatest

minds, Rickey, a devout, teetotalling Methodist, had revolutionized

the game of baseball by developing the farm system. Rickey had long

sympathized with the plight of African Americans, who were barred

from major league baseball and played in their own Negro Leagues.

He believed that ‘‘The greatest untapped reservoir of raw material in

the history of the game is the black race. The Negroes will make us

winners for years to come, and for that I will happily bear being called

a bleeding heart and a do-gooder and all that humanitarian rot.’’ But

Rickey would be called a lot worse when he decided to break

baseball’s color barrier following World War II.

Rickey set out to find a great African American player ‘‘with

guts enough not to fight back’’ against the abuse he would be bound to

endure. He found Jackie Robinson, a brilliant young athlete from

Southern California. In 1947, Robinson became the first African

American to play major league baseball, when he broke in with the

Brooklyn Dodgers. His presence on the field unleashed a torrent of

racial hatred, but both Robinson and Rickey stuck to their guns.

Baseball would never be the same.

In Robinson’s first year in the big leagues, the Dodgers won the

National League pennant and Robinson was voted baseball’s first

Rookie of the Year. On a multi-talented team that featured Duke

Snider, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese and Gil Hodges, Robinson’s

athleticism and competitiveness brought the Dodgers to new heights.

Nonetheless, they lost the Series once again to the Yankees. And

Brooklyn fans were forced once again to ‘‘Wait Till Next Year.’’

During the early 1950s, Walter O’Malley became president of

the organization, Red Barber was joined in the booth by another

future Hall of Famer broadcaster, Vin Scully, and the Dodgers fielded

teams of such talent that they continued to win every season. The

BROOKLYN DODGERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

363

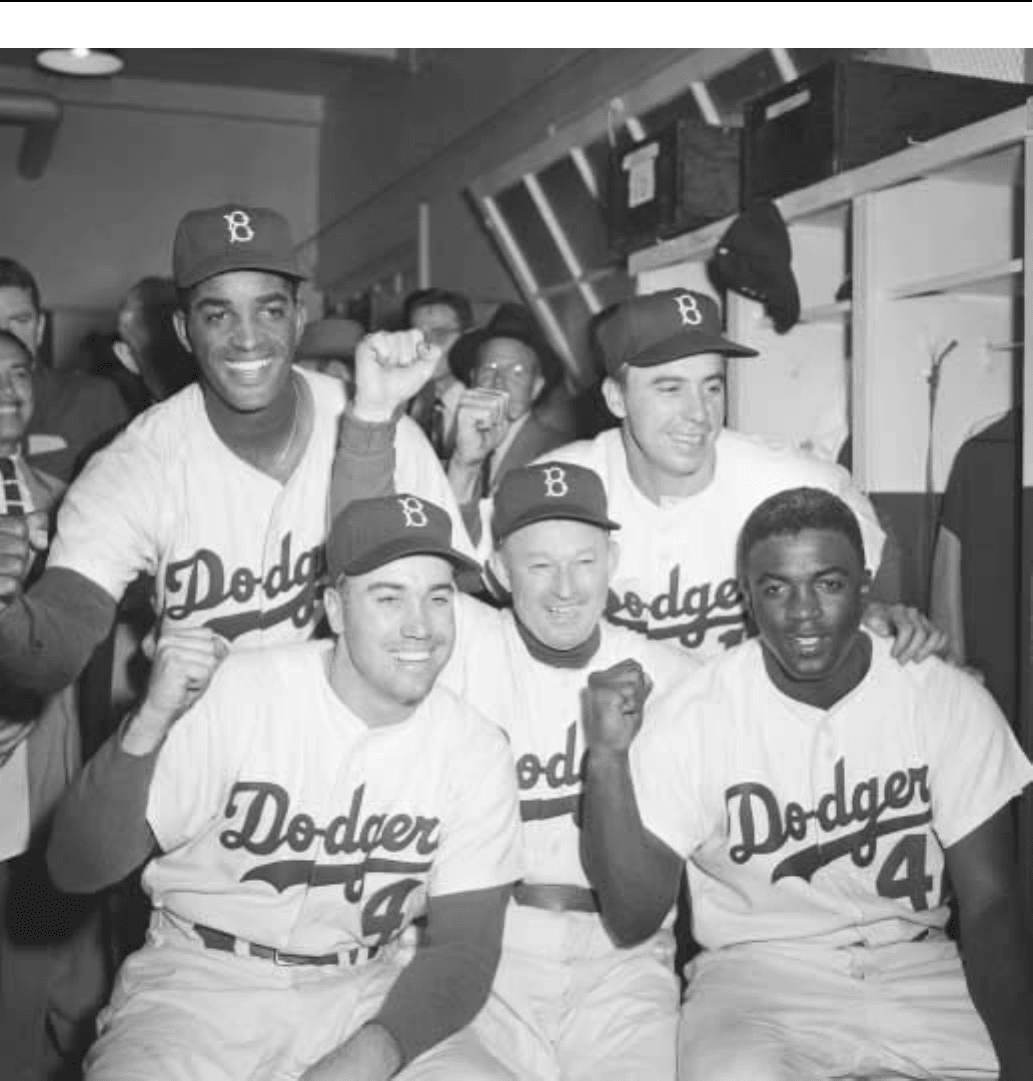

Several members of the Brooklyn Dodgers after winning the first game of the 1952 World Series: (from left) Joe Black, Duke Snider, Chuck Dressen, Pee

Wee Reese, and Jackie Robinson.

1953 team, dubbed the ‘‘Boys of Summer,’’ won a record 105 games.

But they still could not win the World Series. As Roger Kahn has

written, ‘‘You may glory in a team triumphant, but you fall in love

with a team in defeat . . . A whole country was stirred by the high

deeds and thwarted longings of The Duke, Preacher, Pee Wee,

Skoonj, and the rest. The team was awesomely good and yet defeated.

Their skills lifted everyman’s spirit and their defeat joined them with

everyman’s existence, a national team, with a country in thrall,

irresistible and unable to beat the Yankees.’’

Finally, in 1955, the Dodgers did the unthinkable. They beat the

Yankees in the World Series. Two years later, something even more

unthinkable occurred. In what historian and lifelong Brooklyn Dodg-

ers fan Doris Kearns Goodwin calls an ‘‘invidious act of betrayal,’’

team president Walter O’Malley moved the Dodgers to Los Angeles

and an unforgettable era of baseball history came to a close.

—Victoria Price

BROOKS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

364

FURTHER READING:

Burns, Ken, and Geoffrey C. Ward. Baseball: An Illustrated History.

New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Wait Till Next Year: A Memoir. New York,

Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Kahn, Roger. The Boys of Summer. New York, HarperPerennial, 1998.

Prince, Carl E. Brooklyn’s Dodgers: The Bums, The Borough, and the

Best of Baseball 1947-1957. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1996.

Rampersand, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

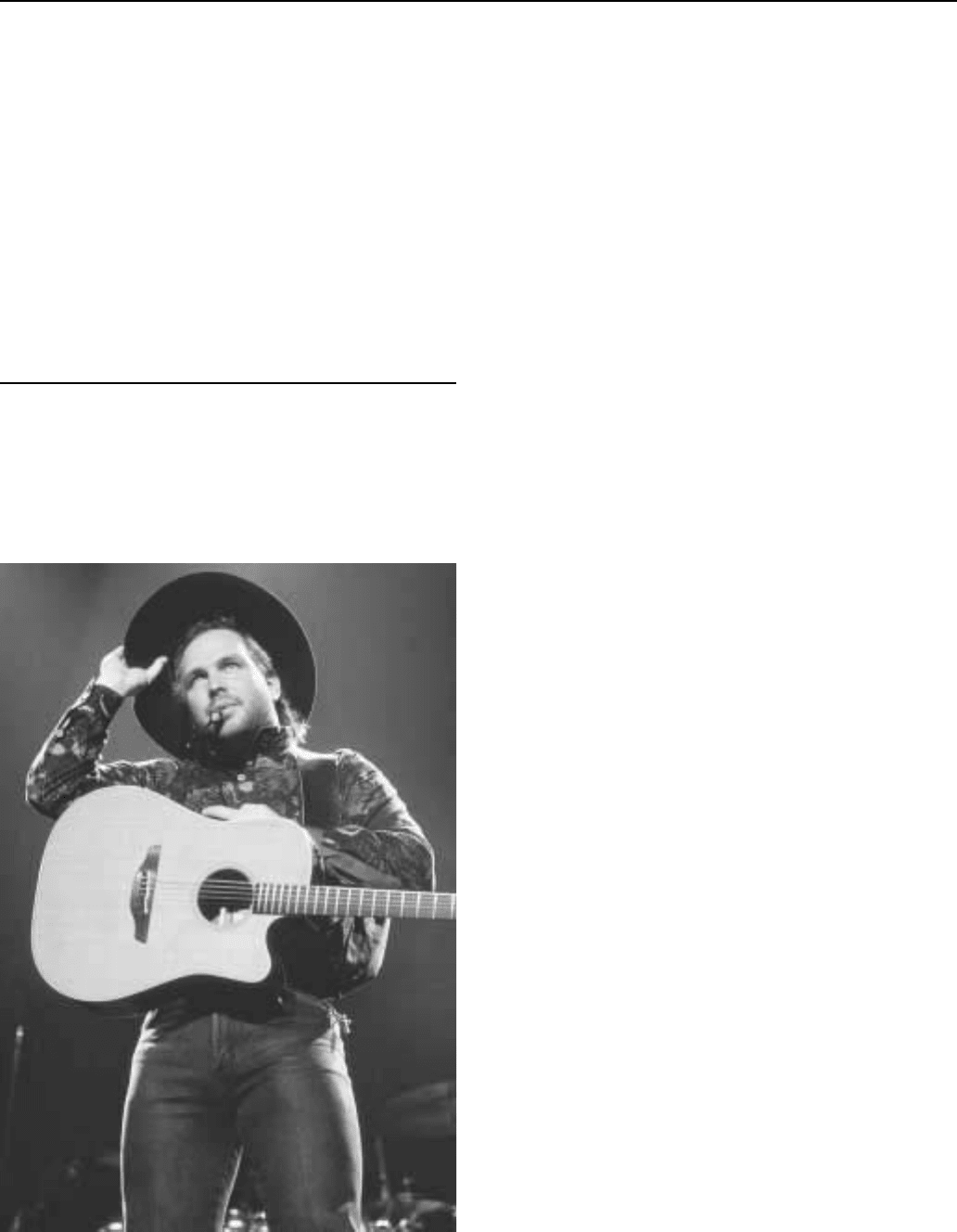

Brooks, Garth (1962—)

Garth Brooks, the best-selling recording artist of all time,

symbolizes the evolution of ‘‘new wave’’ country music in the late

twentieth century. Brooks was popular in the late 1980s and through-

out the 1990s with a blend of country, honky-tonk, and rock that

signaled country’s move into the mainstream of popular music. From

his first self-titled album in 1989, the Oklahoma singer achieved fame

Garth Brooks

beyond the traditional country listener base to achieve acceptance by

a mass audience. Between 1989 and 1996 he sold more than sixty

million albums. Prior to Brooks’s third album, Ropin’ the Wind, it was

nearly impossible for a country artist to sell a million copies, and no

country recording had ever premiered at the top of the pop charts. His

stage performances, which were filled with many special effects such

as fantastic lighting displays, explosions, and even a harness that

allowed him to sing while swinging over his enthusiastic crowds,

resembled the stadium rock extravaganzas of the 1970s. Brooks

combined his onstage identity as the modern country superstar with

an offstage persona emphasizing country music’s traditional values of

family, patriotism, and devotion to one’s fans.

Troyal Garth Brooks, born on February 7, 1962, in Tulsa,

Oklahoma, had a strong interest in country music from childhood. His

mother, Colleen Carroll Brooks, had been a minor country singer in

the 1950s who had recorded several unsuccessful albums for Capitol.

After earning an athletic scholarship to Oklahoma State University

for his ability with the javelin, Brooks began singing in Stillwater

clubs where he had worked as a bouncer. In 1986, he married Sandy

Mahl, a woman he had once thrown out of a bar after a restroom

altercation. The couple moved to Nashville in 1985 after Brooks’s

graduation with an advertising degree. The young singer’s initial

attempt to find fame in the world of country music was a complete

failure, and the pair returned to Oklahoma after a mere twenty-three

hours in Nashville. Two years later, a more mature Brooks returned to

the country music capital and began his career by singing on new

songwriter’s demo tapes. By 1988, he had been signed by Capitol

Records and his first single ‘‘Much Too Young (To Feel This

Damn Old)’’ earned much popular acclaim. His subsequent singles—

‘‘If Tomorrow Never Comes,’’ ‘‘Not Counting You,’’ and ‘‘The

Dance’’—each became number-one hits and marked Brooks’s rising

crossover appeal.

By 1992, Garth Brooks was a true popular culture phenomenon.

He had a string of hit songs and a critically praised network television

special (This Is Garth Brooks), and he had sold millions of dollars

worth of licensed merchandise. Forbes magazine listed him as the

thirteenth-highest-paid entertainer in the United States, the only

country music performer to have made the ranking. Unlike previous

country stars, such as Johnny Cash, Kenny Rogers, and Dolly Parton,

Brooks made country music fashionable to those beyond its core

constituency, a circumstance he credits to the diversity of his early

musical influences. Among those whom Brooks cites as having

affected his style are such diverse artists as James Taylor, Cat

Stevens, John Denver, the Bee Gees, and even some heavy-metal

bands. His expanded appeal also stems from his choice not to limit his

songs to the traditional country music themes. Brooks’s ‘‘We Shall

Be Free’’ is an anthem for the oppressed for its advocacy of

environmental protection, interracial harmony, and the acceptance of

same-sex relationships. His most controversial work of the period,

‘‘The Thunder Rolls,’’ dealt with the issues of adultery, wife beating,

and revenge. Brooks’s desire to expand country presentation and

subject matter attracted a sizable audience unknown to earlier country

performers. Brooks is considered the leader of a new wave of country

vocalists including Travis Tritt, Clint Black, and Alan Jackson.

While Brooks expanded country’s scope, he carefully worked to

maintain his image as a humble country performer, endorsing various

charities and repeatedly professing his overwhelming devotion to his

family. In 1991, he considered forsaking his career to become a full-

time father. Brooks’s most popular offstage act, however, was his

BROOKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

365

devotion to his fans: he signed hundreds of autographs after each

show and, most importantly, demanded that his ticket prices remain

affordable to the average person.

Few performers in any genre can claim the crossover success

exhibited by Garth Brooks in the 1990s. His domination of the

country and pop charts proved that ‘‘country’’ was no longer a niche

format but one acceptable to mainstream audiences. His achieve-

ments were recognized in March, 1992, when he was featured on the

cover of Time, which credited him for creating ‘‘Country’s Big

Boom.’’ His ability to meld traditional country music sounds and

sensibilities with pop themes allowed country to advance to new

heights of popularity.

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Morris, Edward. Garth Brooks: Platinum Cowboy. New York, St.

Martin’s Press, 1993.

O’Meila, Matt. Garth Brooks. Norman, University of Oklahoma

Press, 1997.

Brooks, Gwendolyn (1917—)

Poet Gwendolyn Brooks’s writings explore the discrepancies

between appearance and morality, between good and evil. Her images

are often ironic and coy; her work is distinctly African American. She

won the Pulitzer Prize in 1950, the first time an African American

writer received the award. Born in Topeka, Kansas, Gwendolyn

Brooks published her first poem at age 13. By 1941 she had moved to

Chicago and began studying at the South Side Community Art

Center. In the 1960s she turned to teaching until 1971. More recently,

she became Illinois Poet Laureate and an honorary consultant in

American literature to the Library of Congress. Her publications

include Street in Bronzeville (1945), Annie Allen (1950), Maud

Martha (1953), In the Mecca (1968), and Report from Part One (1971).

—Beatriz Badikian

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Report from Part Two. Chicago, Third World

Press, 1990.

Kent, George E. A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks. Lexington, Kentucky,

University Press of Kentucky, 1990.

Brooks, James L. (1940—)

Emmy Award-winning television writer-producer, James L.

Brooks made an extraordinary feature film debut in 1983 with Terms

of Endearment, winning five Academy Awards, including Best

Screenplay, Director, and Picture. Three further films (including the

Oscar-nominated Broadcast News, 1987) followed at wide intervals,

while Brooks confined himself to wielding his considerable influence

on popular movie and television culture behind the scenes. As a

producer of such hits as Big (1988), The War of the Roses (1989), and

Jerry Maguire (1996), he confirmed his acute instinct for material

with strongly defined characters and popular appeal. Born in New

Jersey and educated at New York University, the former television

newswriter made his major breakthrough with the creation of The

Mary Tyler Moore Show before producing such high-rating series as

Taxi, Cheers, Lou Grant, and Rhoda. In 1997, he returned to

filmmaking, writing, producing, and directing the Oscar-nominated

As Good as it Gets.

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Willsmer, Trevor. ‘‘James L. Brooks.’’ Who’s Who in Hollywood,

edited by Robyn Karney. New York, Continuum, 1993.

Brooks, Louise (1906-1985)

Louise Brooks, American silent film actress and author, achieved

only moderate fame in her film career, but emerged as the focus of a

still-growing cult of admirers in the 1970s, sparked by the renewed

critical interest in her performance as the doomed hedonist Lulu in G.

W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929). The publication of critic Kenneth

Tynan’s New Yorker article ‘‘The Girl in the Black Helmet’’ captured

the imagination of readers who appreciated her caustic wit and her

tales of Hollywood, and also romanticized her hermit-like retreat in

Rochester, New York, after a life of alcoholism and excess. Her sleek

dancer’s body and trademark black bob remain an icon of high style

and eroticism. She inspired two comic strips as well as numerous film

and literary tributes. Brooks became a bestselling author in the 1980s

with her memoir Lulu in Hollywood.

—Mary Hess

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Louise. Lulu in Hollywood. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

Paris, Barry. Louise Brooks. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

Tynan, Kenneth. ‘‘The Girl in the Black Helmet.’’ New Yorker.

June 11, 1979.

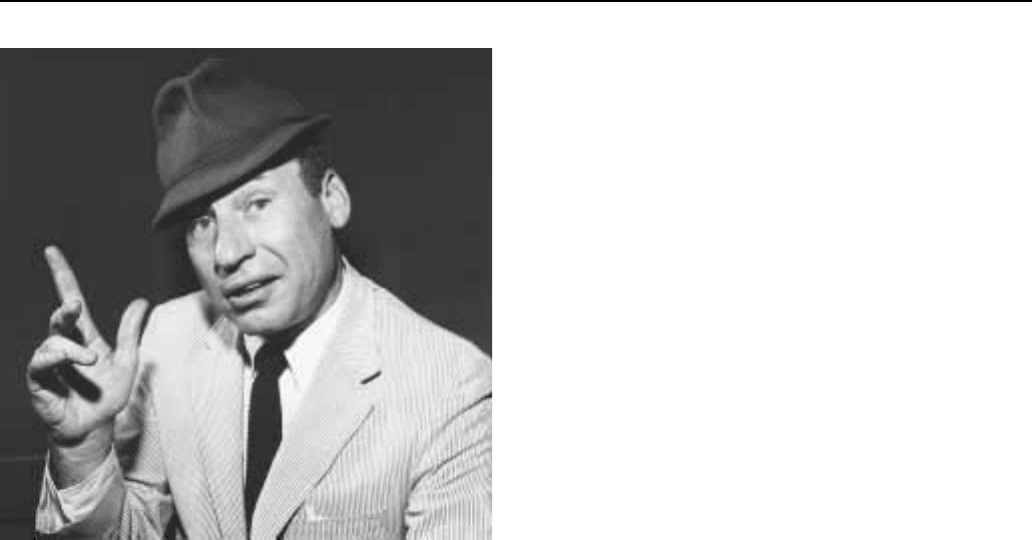

Brooks, Mel (1926—)

A woman once accosted filmmaker Mel Brooks and angrily told

him that his 1968 comedy The Producers was ‘‘vulgar.’’ ‘‘Madame,’’

he said with an air of pride, ‘‘it rises below vulgarity.’’ Mel Brooks

spent a career as a comedy writer, director, and actor offending vast

segments of his audience, while simultaneously making them laugh

uproariously. His series of genre spoofs meticulously recreated the

feel and look of westerns, horror films, and sci-fi classics, only to

upend cliches with an assortment of double-entendres, anachronisms,

musical production numbers, Jewish American references, and jokes

BROOKS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

366

Mel Brooks

about bodily functions. The creators of such 1990s phenomena as

South Park and There’s Something About Mary are direct descendants

of Brooks’ comic sensibility.

Brooks was born Melvin Kaminsky on June 28, 1926 in Brook-

lyn, New York. A boyhood friend was drumming legend Buddy Rich,

who taught Brooks how to play. Brooks performed at parties and,

during the summers, at largely Jewish resorts in the Catskills in

upstate New York. After World War II, Brooks started performing

comedy while social director of Grossinger’s, the most prestigious

Catskills resort, where he became friends with comedian Sid Caesar.

In 1950 Brooks joined the writing staff of NBC television’s

variety series Your Show of Shows, starring Caesar and Imogene

Coca. The anarchy of these writing sessions was immortalized in Carl

Reiner’s 1960s sitcom The Dick Van Dyke Show and Neil Simon’s

1994 play Laughter on the 23rd Floor. Nobody, Caesar’s colleagues

agreed, was more anarchic than Brooks. When Your Show of Shows

lost an Emmy for best writing, Brooks stood up from his seat in the

auditorium and yelled, ‘‘Nietschke was right—there is no God!’’

Reiner and Brooks would often improvise comedic characters

during the manic writer’s meetings. One morning, Reiner introduced

Brooks as the only living witness to Christ’s Crucifixion. The persona

of the ‘‘2000 Year Old Man’’ was born. What began as a private joke

eventually became the subject of five comedy albums over a 35 year

span. Brooks’ character had seen it all and done it all over two

millenia, yet his needs and demands were small. ‘‘I have over 42,000

children,’’ he once proclaimed, ‘‘and not one comes to visit.’’ The

Stone Age survivor claimed that the world’s first national anthem

began, ‘‘Let ’em all go to hell, except Cave Seventy Six!’’

With Buck Henry, Brooks created the television sitcom Get

Smart!, a savage sendup of the James Bond films, in 1965. Maxwell

Smart (Don Adams) was a thorough incompetent who could not

master his collection of Bond-like gadgets, such as a shoe-phone. The

bad guys were usually caught with the aid of Smart’s truly smart

assistant, Agent 99. The series lasted five seasons.

During the 1950s and 1960s Brooks worked on several unsuc-

cessful Broadway shows, and he began wondering what would

happen if two guys deliberately decided to produce the worst musical

ever. The result was the 1968 classic The Producers, Brooks’s

directoral debut. Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder played the title

characters who decide to stage ‘‘Springtime for Hitler,’’ a lightheart-

ed toe-tapper about the Nazi leader (complete with dancing SS

troopers). Mostel and Wilder collect 100 times more capital than

needed. To their dismay, ‘‘Springtime for Hitler’’ becomes a smash

hit and the pair, unable to pay their many backers, wind up in jail. The

film became a cult hit, and Brooks won an Oscar for Best Screenplay.

Blazing Saddles (1973) inverted virtually every Western movie

cliche. Black chain gang workers are ordered to sing a work song—

and quickly harmonize on Cole Porter’s ‘‘I Get a Kick Out of You.’’

Cowboys eating endless amounts of beans by the campfire begin

loudly breaking wind. The plot had black sheriff (Cleavon Little)

unite with an alcoholic sharpshooter (Wilder) to clean up a corrupt

Old West town. Brooks himself appeared in two roles, a Yiddish

Indian chief and a corrupt governor. The film offended many (some

thought the village idiot, played by Alex Karras, insulted the mentally

retarded) but became the highest grossing movie comedy of all time.

Brooks followed with what most consider his masterpiece,

Young Frankenstein (1974). Gene Wilder starred as the grandson of

the famous doctor, who himself attempts to bring a dead man (Peter

Boyle) to life. Once resurrected, Boyle ravishes Wilder’s virginal

fiancee (Madeline Kahn), to her ultimate pleasure. Wilder devises a

brain transplant with Boyle; Wilder gives Boyle some of his intellect,

while Boyle gives Wilder some of his raging libido. The film was

beautifully shot and acted, and the image of Peter Boyle as the

Frankenstein monster in top hat and tails singing ‘‘Putting on the

Ritz’’ to an audience of scientists ranks as one of the most inspired in

cinematic history.

Silent Movie (1976) was the first Hollywood silent movie in four

decades. Brooks, Marty Feldman, and Dom Deluise played film

producers trying to sign film stars (including Paul Newman, Burt

Reynolds, Liza Minelli, and, Brooks’ real-life wife, Anne Bancroft)

to appear in their silent comedy. High Anxiety (1978) satirized

Hitchcock films, starring Brooks as a paranoid psychiatrist. History of

the World, Part One (1981) sent up historical epics; the most

memorable scene was a musical comedy number set during the

Inquisition, ending in Busby Berkeley style with nuns rising from

Torquemada’s torture tank atop a giant menorah. Brooks continued

his series of movie satires during the 1980s and 1990s. Spaceballs

(1987) sent up Star Wars, while his other films included Robin Hood:

Men in Tights and Dracula: Dead and Loving It.

Upon being introduced to his future second wife (since 1964),

the glamorous stage and film actress Anne Bancroft, he told her, ‘‘I

would KILL for you!’’ He occasionally did cameo roles in film and

television, winning an Emmy as Paul Reiser’s uncle on the situation

comedy Mad About You. In inimitable fashion, Brooks once defined

comedy and tragedy: ‘‘Tragedy is when I cut my finger on a can

opener, and it bleeds. Comedy is when you walk into an open sewer

and die.’’

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Adler, Bill. Mel Brooks: The Irreverent Funnyman. Chicago, Playboy

Press, 1976.

BROWNENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

367

Manchel, Frank. The Box-office Clowns: Bob Hope, Jerry Lewis, Mel

Brooks, Woody Allen. New York, F. Watts, 1979.

Tynan, Kenneth. Show People. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Yacowar, Maurice. Method in Madness: The Art of Mel Brooks. New

York, St. Martin’s, 1981.

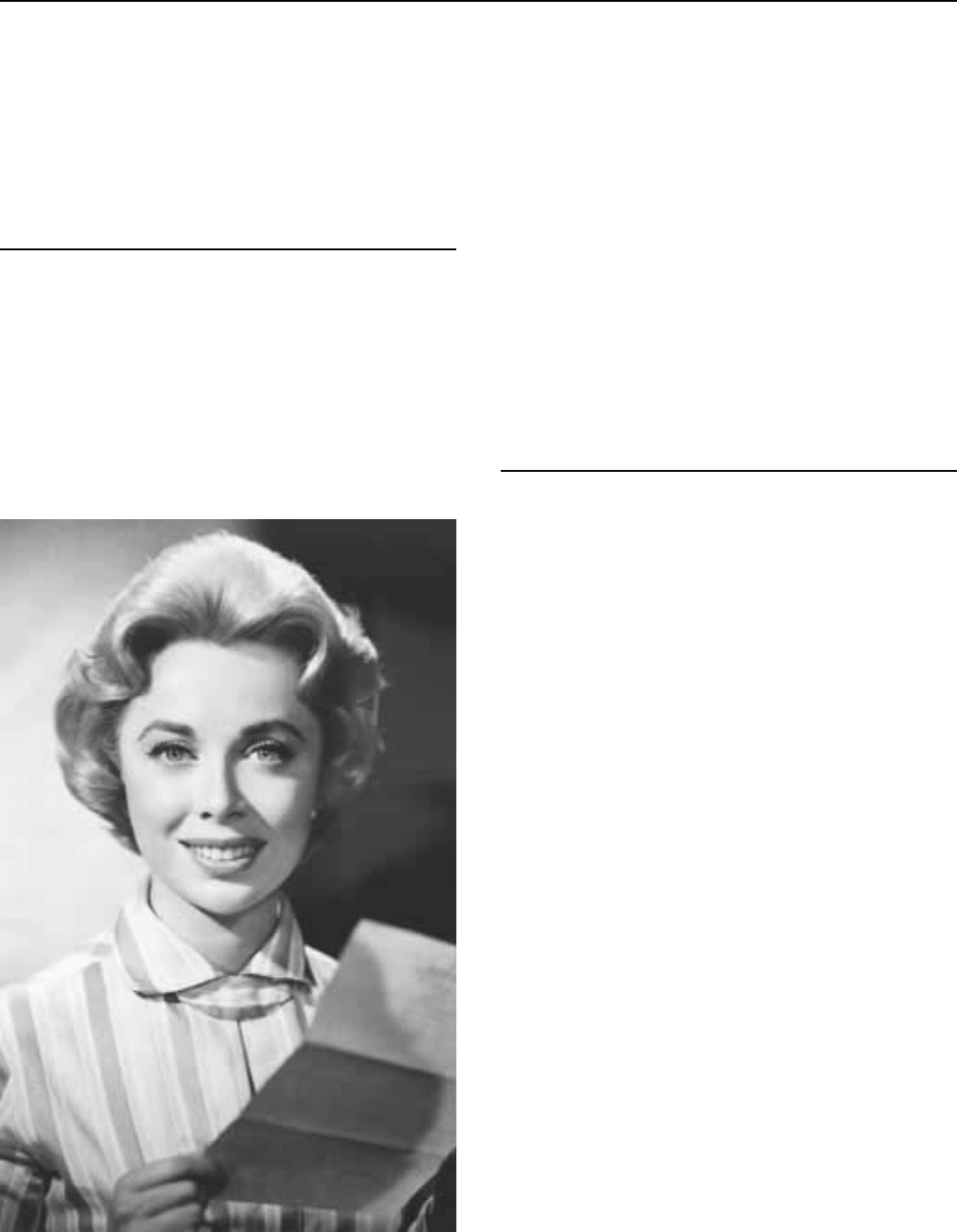

Brothers, Dr. Joyce (1928—)

Dr. Joyce Brothers, a psychologist who earned her Ph.D. from

Columbia University in 1957, has been a media personality since the

late 1950s. She was among the first television celebrities to combine

academic credentials with broadcasting savvy and, in many ways, Dr.

Brothers pioneered the expert culture on which television talk shows

and news magazines now rely for commentary and analysis. In

December 1955, Dr. Brothers became the second contestant to win a

grand prize on the $64,000 Question, the television game show that

would later be mired in scandal. The publicity that followed led her to

choose a career in broadcasting. In addition to her television and radio

Dr. Joyce Brothers

appearances, Dr. Joyce Brothers has authored several books and

writes a syndicated newspaper column.

—Michele S. Shauf

F

URTHER READING:

Brothers, Dr. Joyce. Dr. Brothers’ Guide to Your Emotions. Paramus,

New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1997.

———. How to Get Whatever You Want Out of Life. New York,

Ballantine Books, 1987.

Brown, Helen Gurley

See Cosmopolitan; Sex and the Single Girl

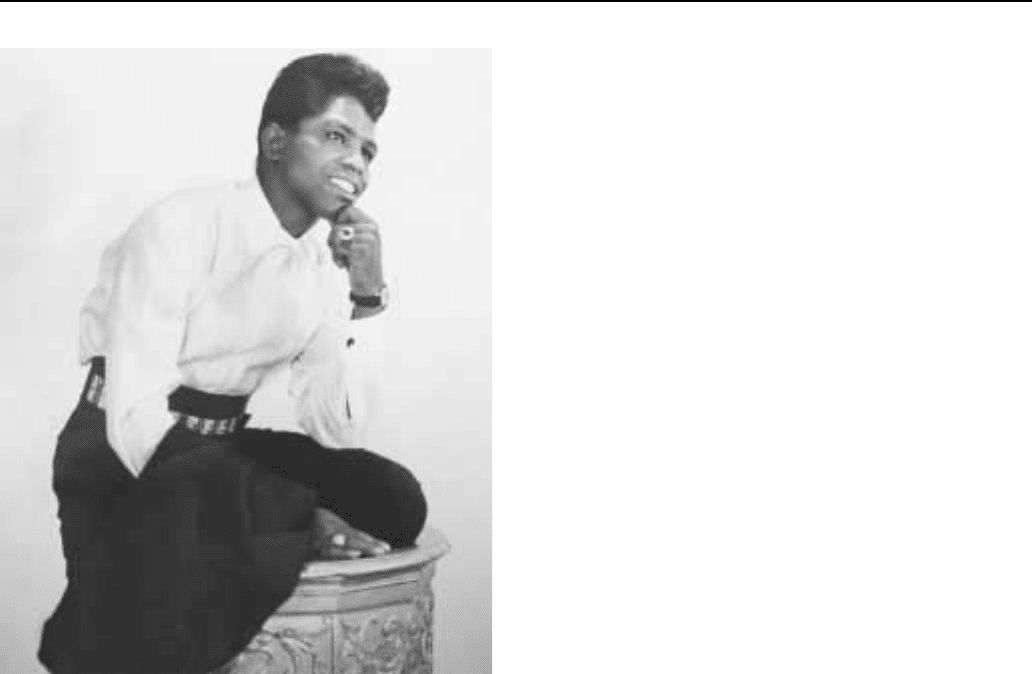

Brown, James (1933—)

Known as the ‘‘Godfather of Soul,’’ this influential African-

American singer was, in the 1950s and 1960s, one of the seminal

figures in the transformation of gospel music and blues to soul. Also

known as ‘‘Soul Brother Number 1’’ and ‘‘The Hardest Working

Man in Show Business,’’ Brown amassed a record-setting total of 98

entries on Billboard’s top-40 R&B singles chart while influencing

scores of performers such as Sly and the Family Stone, Kool and the

Gang, and Prince, as well as contemporary rap and hip-hop perform-

ers. Brown is also a charter member of the Rock and Roll Hall of

Fame and has won numerous awards for his recordings. Despite these

professional successes, Brown is notorious for his ‘‘bad-boy’’ reputa-

tion stemming from several run-ins with the law over the years; he

served prison time as a youth for theft and later for resisting arrest and

traffic violations. He also experienced serious personal and business

troubles in the 1970s, complicated by a longstanding dispute with the

IRS over millions of dollars in back taxes that were resolved in part by

his hiring of the radical attorney William Kunstler.

Born James Joe Brown, Jr. on May 3, 1933 in Barnwell, South

Carolina, Brown early on became accustomed to grinding poverty

and the struggle for survival. The family lived in a shack in the woods

without plumbing or electricity. His father, Joe Garner Brown, made a

living by selling tree tar to a turpentine company. Brown’s parents

separated when he was four and he continued to live with his father.

The family moved to Augusta, Georgia, where his father left him

under the guardianship of an aunt who ran a whorehouse. Brown

earned money for rent and clothing by buck dancing for soldiers and

by shining shoes.

Young James Brown’s musical talent emerged at an early age.

His father gave him a harmonica that he taught himself to play, and

Brown sang gospel with friends, emulating the Golden Gate Quartet.

Other members of the Augusta community guided his musical

development: the famous Tampa Red taught him some guitar, and

Leon Austin and a Mr. Dink taught him piano and drums respectively.

Brown listened to gospel, popular music, blues, and jazz. His expo-

sure to Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five’s short film Caldonia

convinced him that he should be an entertainer. At the age of 11,

Brown won an amateur-night contest at the Lenox Theater for singing

BROWN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

368

James Brown

‘‘So Long’’ and started a trio called Cremona in which he played

piano, drums, and sang.

Mired in poverty, Brown began resorting to petty theft for his

personal wardrobe, then began stealing automobile parts, for which

he was arrested and sentenced to 8-to-18 years in the penitentiary, and

later transferred to the Georgia Juvenile Training Institute. While in

prison, he formed a gospel quartet, earning the name ‘‘Music Box’’

from his fellow inmates and insisting that gospel music helped him

keep his sanity. While incarcerated, he met Bobby Byrd, a musician

with whom he would later have a long-lasting professional relation-

ship. After securing an early release based good behavior and a

promise to his parole board to develop his creative talents, Brown

settled in Toccoa, Georgia, where he lived with Bobby Byrd’s family

and worked at a car dealership while immersing himself in gospel

music after hours. Brown formed a group called the Gospel Starlighters,

which eventually evolved into the Famous Flames, an R&B group

that consisted of Bobby Byrd, Sylvester Keels, Doyle Oglesby, Fred

Pullman, Nash Knox, Baby Roy Scott, and Brown. Later, Nafloyd

Scott would join the group as a guitarist.

In 1955, a studio recording of ‘‘Please, Please, Please’’ became

the group’s first hit, which became a regional favorite. Ralph Bass, a

talent scout signed the group for the King/Federal record label. In

1958, the group recorded ‘‘Try Me,’’ which rose to the number one

spot on the R&B chart. Based on this recording, the group solidified

and began to fill major auditoriums with its strong black following.

Several hits ensued, but it was the 1963 release of the album Live at

the Apollo that catapulted Brown into national recognition when it

rose to the number two spot on Billboard’s album chart. Radio

stations played the album as if it were a single and attendance at

Brown’s concerts increased dramatically.

Throughout most of his career Brown has been sensitive to

political and social issues. Though he never graduated from high

school, his 1966 recording ‘‘Don’t Be a Drop Out’’ posted at number

four on the R&B chart, and he approached Vice President Hubert

Humphrey with the idea of using the song as the theme for a stay-in-

school campaign aimed at inner-city youth. His prominence in this

effort encouraged activist H. Rap Brown to urge the singer to be more

vocal in the black-power movement, which James Brown often found

too extreme for his tastes. Still, during the civil-rights activism of the

1960s, he purchased radio stations in Knoxville, Baltimore, and

Atlanta as a way of giving greater clout to blacks in the media, and his

recording ‘‘Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud’’ became one of

the unofficial theme songs of the new black consciousness. During

those years, Brown wielded political clout and garnered respect and

attention in the black community, though he endured criticism in

some circles for his association with Humphrey and his later friend-

ship with President Richard Nixon—the singer endorsed Humphrey

for President in 1968 and Nixon in 1972, and performed at Duke

Ellington’s inaugural gala for Nixon in January of 1969. Earlier, in the

wake of the urban unrest following the April 1968 assassination of Dr.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Brown interrupted his stations’ programming

with live broadcasts in which he urged nonviolence. In Boston the

following day, he acceded to a request by Mayor Kevin White to

appear on a live television program advocating a similar response.

While Brown and the Famous Flames secured a number of top

ten hits on the R&B charts, ‘‘Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag’’ earned

Brown his first top ten single on the pop side. Hit after hit followed on

both the top ten R&B and pop charts, including ‘‘I Got You (I Feel

Good)’’ in 1965, ‘‘It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World’’ in 1966, ‘‘Cold

Sweat (Part I)’’ in 1967, and ‘‘I Got the Feelin’’’ in 1968. Having

made his political statement in ‘‘Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m

Proud,’’ Brown dropped the Flames and began refining his group,

with drummer Clyde Stubblefield providing increasing rhythmic

complexity. ‘‘Mother Popcorn’ in 1969, and ‘‘Get Up (I Feel Like

Being a) Sex Machine’’ in 1970 signaled changes in his style.

In 1971, Brown formed a new group, the JBs, and signed with

Polydor Records, which soon released two hits, ‘‘Hot Pants,’’ and

‘‘Make It Funky.’’ In 1973, he suffered three serious setbacks: the

tragic death of his son, Teddy, in an automobile accident, the

withdrawal from his group of his old friend, keyboardist Bobby Byrd,

and an IRS demand for payment of $4.5 million in back taxes. He later

blamed Polydor for some of his troubles, writing in his 1990 autobi-

ography James Brown: The Godfather of Soul: ‘‘The government hurt

my business a lot, a whole lot. But they didn’t destroy me. Polydor did

that. It was basically a German company, and they didn’t understand

the American market. They weren’t flexible; they couldn’t respond to

what was happening the way King [Records] could. They had no

respect for the artist .... ’’ Troubles continued to mount for Brown

during the 1970s: The popularity of disco diminished interest in his

kind of music; he was implicated in a payola scandal; his second wife,

Deirdre Jenkins, left him; and he was arrested during a 1978 perform-

ance at New York’s Apollo Theater because he had left the country in

defiance of a court order restricting his travel while the financial

affairs of his radio stations were under investigation.

The evolution of Brown’s musical style can be divided into three

stylistic periods. The first period, in the mid-1950s, consists of ballads

(‘‘Please, Please, Please,’’ ‘‘Try Me,’’ and ‘‘Bewildered’’) based on