Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

arson and murder throughout the coal mining regions of

eastern Pennsylvania during the 1860s and 1870s in order to

intimidate mine supervisors. They became so powerful in

some places that they held official positions within munici-

pal governments and police forces. After infiltration by an

agent of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1875, the move-

ment was effectively destroyed by 1877 with the arrest and

execution of most of the Molly Maguire leaders.

Further Reading

Broehl, Wayne G. The Molly Maguires. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University P

ress, 1966.

Kenny, Kevin. Making Sense of the Molly Maguires. New York: Oxford

U

niv

ersity Press, 1998.

Lens, Sidney. The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sitdowns.

Gar

den City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1973.

Montreal, Quebec

Montreal, the second largest city in Canada and one of the

largest French-speaking cities in the world, had a population

of 3,380,645 in 2001. Strategically situated on the St.

Lawrence River, it was the economic center of Canada from

the 18th century and thus attracted large numbers of immi-

grants. Toronto became more important economically from

the 1940s, but Montreal remained one of the great educa-

tional and cultural centers of Canada and thus continued to

attract immigrants. In 2001, Italians (224,460), Jews

(80,390), Haitians (69,945), Chinese (57,655), Greeks

(55,865), Germans (53,850), Lebanese (43,740), and Por-

tuguese (41,050) were the largest nonfounding groups living

in the city. Between 2000 and 2002, about 31,000 immi-

grants settled in Montreal annually, with almost one-third

coming from Africa and the Middle East and 27 percent

from Asia and the Pacific. China was the largest source

country, with 8,993 immigrants, but was closely followed by

three francophone countries: France with 8,845; Morocco

with 8,032; and Algeria with 7,061. In 2002, Montreal

attracted more immigrants than Vancouver (33,000 to

30,000) for the first time since 1993.

J

ACQUES

C

ARTIER

explored the area of modern Mon-

treal in 1535, but the first French settlement was not estab-

lished until 1642. By the early 18th century, Montreal had

become the commercial center of N

EW

F

RANCE

. The cap-

ture of the city in 1760 by British forces during the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

effectively ended French political control. By

the terms of the Treaty of Paris, Montreal and New France

were formally transferred to Britain in 1763. Many mer-

chants returned to France, enabling British businesses to

gain gradual control as the local economy shifted from the

fur trade to shipbuilding and industry. By 1850, the pop-

ulation reached 50,000, then doubled during the next 20

years. Completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in

1885 further enhanced the industrial capacity of the city,

and by 1914, the population had grown to almost a half

million.

In 1901, Montreal was made up almost totally of

French (60.9 percent) and British stock (33.7 percent), an

unusual lack of diversity for a major North American city.

This changed significantly between 1900 and 1914, with a

large influx of Europeans, most notably Jews, Germans,

Poles, and Ukrainians. By 1911, these newcomers accounted

for almost 10 percent of the population. After 1930, an

increasing number of Italians, Greeks, Chinese, blacks from

the United States and the Caribbean, and Lebanese arrived.

Following the disruptions of World War II (1939–45), there

were significant influxes from Germany, Greece, Portugal,

and Italy. Relaxed immigration rules in the early 1960s led

to development of the first Haitian community. Although

Montreal had become considerably more diverse by the

1960s, it was still largely a European city. After 1970, immi-

gration to Montreal was characterized by the shift in source

countries from Europe to various parts of the developing

world and the favoring of immigrants from former French

colonies, especially Vietnam, Haiti, Morocco, and Algeria. A

significant number of Central Americans and South Ameri-

cans also began to arrive. With the retrocession of Hong

Kong to China in 1997, Chinese immigration to Montreal

was high in the 1990s.

With the majority of the population of French descent,

there was considerable ethnic tension in Montreal during

the 20th century. It was most evident over the question of

conscription during World War I (1914–18) and World War

II. During the 1960s and 1970s, Quebec Province was the

center of a French-Canadian nationalist movement whose

supporters were known as Quebecois; some sought full inde-

pendence for the province of Quebec. By the 1960s, Mon-

treal had become a polyglot city and was losing some of its

distinctive French character, particularly as more French

speakers moved to the suburbs. The debate over the value

of immigration was often heated, especially as it tended to

support a greater use of the English language. In the years

following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there

was a growing reluctance to welcome more immigrant from

Islamic countries. Although Montreal was a relatively low-

crime city, rising crime rates were sometimes attributed to

immigrants, as in the case of Iranian refugees arriving in the

early 1980s who had connections with the Southeast Asian

heroin trade. By the late 1990s, more than 100 had been

convicted of drug trafficking. Nevertheless, a study con-

ducted throughout the 1990s demonstrated that most

immigrants in Montreal blended well within the society and

that their use of French in public life was only slightly lower

than that of native Montrealers.

By summer 2002, Quebec Province was actively seeking

ways to encourage immigrant settlement outside Montreal,

but found the lack of specialized jobs a stumbling block. At

the same time, Canadian immigration minister Denis

194 MONTREAL, QUEBEC

Coderre observed that Canada would face a shortage of up

to 1 million skilled workers within five years, suggesting the

likelihood that the Montreal immigrant community would

continue to grow.

Further Reading

Berdugo-Cohen, Marie, and Yolande Cohen. Juifs marocains à mon-

treal: témoignages d

’une immigration moderne. Montreal: VLB,

1987.

Lam, Lawr

ence. F

rom Being Uprooted to Surviving: Resettlement of Viet-

namese-Chinese “Boat People

” in Montreal, 1980–1990. Toronto:

York Lanes P

ress, 1996.

Lavoie, Nathalie, and Pierre Serre. “From Bloc Voting to Social Vot-

ing: The Case of Citizenship Issues of Immigration to Montreal,

1995–1996.” Peace Research Abstracts 39, no. 6 (2002): 763–957.

Linteau, Paul-André. Histoir

e de la ville de Montréal depuis la Con-

fédér

ation. Montreal: Boreal, 1992.

M

arois, Claude. “Cultural Transformations in Montreal since 1970.”

Jour

nal of Cultural Geography 8, no

. 2 (1988): 29–38.

McNicoll, Claire. Montréal, une société multiculturelle. Paris: Belin,

1993.

M

onette, Pierre. L’immigrant Montréal. Montreal: Tripty

que, 1994.

P

enisson, Bernard. “L’émigration française au Canada.” In L’émigra-

tion française: études de cas: A

lgérie—Canada—Etats-Unis. Paris:

Université de Paris I, Centre de r

echerches d’histoire nord-améri-

caine, 1985.

Ramirez, Bruno. The Italians of Montreal: From Sojourning to Settle-

ment, 1900–1921. Montreal: Editions du Courant, 1980.

———. “

W

orkers without a Cause: Italian Immigrant Labour in

Montreal, 1880–1930.” In Arrangiarsi: The Italian Immigration

Experience in Canada. Eds. Rober

to Perin and Franc Sturino.

Montreal: Guernica, 1989.

Robinson, Ira, Pierre Anctil, and Mervin Butovsky, eds. An Everyday

M

ir

acle: Yiddish Culture in Montreal. Montreal: Véhicule Press,

1990.

R

obinson, I

ra, and Mervin Butovsky, eds. Renewing Our Days; Mon-

treal J

ews in the Twentieth Century. Montreal: Véhicule Press,

1995.

Moroccan immigration

The Moroccan presence in North America was small until

the 1950s. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 38,923 Americans and 21,355

Canadians claimed Moroccan descent. Most Moroccan

Americans lived in large urban areas, mainly in New York

and New England. Three-quarters of all Canadian Moroc-

cans lived in M

ONTREAL

,Q

UEBEC

.

Morocco covers 177,117 square miles in northwestern

Africa. It is bordered on the east by Algeria and on the south

by Western Sahara (a contested area). Ten miles to the north,

across the Mediterranean Sea, lies Spain. About three-quar-

ters of Morocco’s population of 29,237,000 (2001) is

Berber, but the majority of Berbers speak Arabic and prac-

tice Islam. The country is mainly divided between Arab cul-

ture (65 percent) and Berber culture groups (33 percent),

though 98 percent of the entire population is Muslim. Set-

tled mainly by Berber tribespeople in ancient times,

Morocco was an ally of Rome, forming part of its province

of Mauretania. Morocco was conquered by Arab armies dur-

ing the seventh century, though Berber resistance and

regional independence remained prominent until the 11th

century, when the Almoravid confederation conquered vir-

tually all the country. Almost all Moroccans eventually con-

verted to Islam. During the 14th and 15th centuries,

thousands of Jews fleeing persecution in Spain and Portugal

settled in Morocco. France and Spain both began to

encroach on Moroccan territory during the 1840s and

1850s, and France ruled the region from 1912 to 1956,

when it regained its independence. Morocco’s Jews fared

well under the French, but their position deteriorated when

the French government installed in Vichy cooperated with

Nazi Germany during World War II (1939–45). Between

1945 and 1956, most of Morocco’s 270,000 Jews emigrated,

with the largest number going to Israel. Some, however,

came to the United States and Canada.

There were almost no Moroccans in North America

prior to World War II. With tiny Muslim communities, the

United States and Canada were not attractive cultural mag-

nets for non-Jews, who made up about 98 percent of the

Moroccan population. Also, until the late 1990s, France and

Spain usually welcomed Moroccan workers, who found it

convenient to travel back and forth between work and

home. By the 1990s, however, an increasing number were

turning to North America, favoring French-speaking Mon-

treal as a destination. In 2001, more than 16,000 of

Canada’s 21,000 Moroccans lived in Montreal, with more

than 40 percent arriving between 1991 and 2001. Most

recent Moroccan immigrants to the United States tended to

be somewhat better educated, though it is still early to deter-

mine the relative success of Moroccan integration. In 1990,

there were about 15,000 Moroccan immigrants in the coun-

try, most residing in New York City where there was a strong

activist element among Muslim leaders. The Moroccans

played a large role in building New York’s second mosque,

the Islamic Mission of America for the Propagation of Islam

and Defense of the Faith and the Faithful. Between 1992

and 2002, about 27,000 Moroccans immigrated to the

United States, representing 70 percent of the entire Moroc-

can community in the country.

Further Reading

Abu-Laben, Baha. An Olive Branch on the Family Tree: The Arabs in

Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1980.

Bibas, D

avid. Immigrants and the Formation of Community: A Case

Study of M

oroccan Jewish Immigration to America. New York:

AMS Pr

ess, 1998.

Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab People. Cambridge, Mass.: Har-

v

ar

d University Press, 1993.

MOROCCAN IMMIGRATION 195

Naff, Alixa. Becoming American: The Early Arab Experience. Carbon-

dale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

Pennell, C. R. Morocco since 1830: A History. New York: New York

Univ

ersity P

ress, 2001.

Waugh, Earle H., Sharon McIrvin Abu-Laban, and Regula B.

Quereshi, eds. Muslim Families in North America. Edmonton,

Canada: U

niversity of Alberta Press, 1991.

Morse, Samuel F. B. (1791–1872) inventor, political

activist

Best remembered for developing the Morse code and the

first working telegraph, Morse was also one of the leading

anti-Catholic activists of his day. Because of his public

prominence, his opinion carried considerable public weight,

reinforcing nativist tendencies in the United States.

The son of a Calvinist minister, Morse attended Phillips

Academy in Massachusetts and Yale University in Connecti-

cut. In order to develop his craft as a professional artist,

Morse traveled widely in Europe between 1829 and 1832.

On his return trip to the United States, he began work on

what would become his code and telegraph. Before he

earned a government commission to build a telegraph line

between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in 1843, Morse

was often in financial difficulty. This led him to study the

new photographic techniques of Louis-Jacques-Mandé

Daguerre while in France and to become one of the pioneers

of photography in the United States. He was a founder and

president of the National Academy of Design (1826–45,

1861–62) and was long associated with New York Univer-

sity (1832–71).

During a stay in Rome, Morse became intensely anti-

Catholic. His native suspicion of papal authoritarianism was

reenforced when a common soldier, seeing that Morse’s head

remained covered during a Catholic procession, used his

bayonet to knock Morse’s hat from his head. He carried this

animosity back to the United States, making it part of his

political creed. Shortly before making an unsuccessful run

for mayor of New York City, he wrote letters to the New

Y

or

k Observer that were collected and published as A Foreign

Conspiracy against the L

iberties of the United States (1834).

The letters wer

e aimed at the Leopold Association of

Vienna, a Catholic missionary organization whose purpose

was the proselytization of the United States. In the following

year, Morse published Imminent Dangers to the Free Institu-

tions of the U

nited S

tates through Foreign Immigration and

Present State of the Naturalization Laws. Morse’s particular

brand of

NATIVISM

was aimed predominantly at Catholics

and especially the Irish. In Imminent Dangers he railed

against what he termed a “naturaliz

ed foreigner” who pro-

fessed to “become an American” but “

talks (for example) of

Ireland as ‘his home,’ as ‘his beloved country,’ resents any-

thing said against the Irish as said against him, glories in

being Irish, forms and cherishes an Irish interest, brings

hither Irish local feuds, and forgets, in short, all his new obli-

gations as an American, and retains both a name and a feel-

ing and a practice in regard to his adopted country at war

with propriety, with decency, with gratitude, and with true

patriotism.” During the Civil War (1861–65), Morse

increasingly viewed immigrants as a prop to the stability of

the Union, rather than a potential source of destruction.

Further Reading

Kloss, William. Samuel F. B. Morse. New York: Harry N. Abrams,

1988.

M

abee, Carleton. The American Leonardo: A Life of Samuel F. B. Morse.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1943.

M

orse, Edward Lind, ed. Samuel F. B. Morse: His Letters and Journals.

2 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914.

S

taiti, P

aul J. Samuel F. B. Morse. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Pr

ess, 1989.

196 MORSE, SAMUEL F. B.

National Origins Quota Act (United States)

(1924) See J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

.

nativism

Nativism is a strong dislike for ethnic, religious, or politi-

cal minorities within one’s culture. In North America it

was founded principally upon the fear that immigrant atti-

tudes will erode the distinctive features of the majority cul-

ture. Unlike ethnocentrism, a generalized, largely passive

perception of the superiority of one’s own culture, nativism

leads to pronounced activism and sometimes hostile mea-

sures taken in order to avert a perceived danger. Nativism

is common in most cultures during times of economic or

political turmoil, and there have been periodic waves of

nativism in both the United States and Canada throughout

their histories.

In the United States, there had been from the earliest

colonial days a mistrust among settlers from different

countries and of different religions. These general

antipathies first rose to form a nativist movement in the

1790s, when Federalists hoped to keep out what they saw

as the corroding influence of radical immigrants by passing

the A

LIEN AND

S

EDITION

A

CTS

. With the majority of set-

tlers in British territories being Protestant Anglicans and

Puritans, Quakers and Roman Catholics were seen as

potential threats to the traditional English order. While

these attitudes persisted in the early republic, there was no

full-blown nativist frenzy until the 1830s: The influx of

more than a quarter million Irish, most of them Catholic,

between 1820 and 1840 led to the second great wave of

nativism in the United States. As most Americans were

members of Protestant denominations that fostered the

ethic of American individualism, it was easy to convince

people in hard times that “papal schemes” to control Amer-

ican society were afoot. S

AMUEL

F. B. M

ORSE

’s Foreign

Conspiracy against the Liberties of the United States (1834)

and Rev

erend Lyman Beecher’s A Plea for the West (1835)

sought to alert Americans to clandestine plots being mas-

terminded in R

ome for the cultural takeo

ver of the coun-

try. Sensational exposés of Catholic practices were

common in the press. Maria Monk’s Awful Disclosures of

the Hotel Dieu Nunner

y of M

ontreal (1836), purporting to

tell the firsthand account of the author’s imprisonment in

a Catholic monaster

y

, was a best-seller and remained so

long after she was discredited. In addition to vague fears

of conspiracy, many Americans feared the potential power

of the Roman Catholic Church to overturn the Protestant

foundation of the emerging public system of education.

This sometimes led to violence, as in the Philadelphia riots

of 1844, when a number of Irish Catholics were killed and

several churches burned. This anti-Catholic nativism led

during the 1850s to the rise of the Secret Order of the Star-

Spangled Banner, more commonly known as the Know-

Nothing or American Party. The Know-Nothings were

particularly strong in the Northeast and border regions. In

the wake of their strong showing in 1854 and 1855, in

which they gained control of several state governments and

197

N

4

sent more than 100 congressmen to Washington, they

attempted to restrict immigration, delay naturalization,

and investigate perceived Catholic abuses. Finding little

evidence to support Catholic crimes or conspiracies and

with the country embroiled in the states’ rights and slav-

ery issues, Know-Nothing political influence and anti-

Catholic nativism waned. Many non-Catholic Americans

remained suspicious of Catholics, and occasionally anti-

Catholic nativism reemerged, as in the formation of the

A

MERICAN

P

ROTECTIVE

A

SSOCIATION

(1887). Generally

speaking, however, religion became less and less a primary

motivation for open hostility toward immigrants.

198 NATIVISM

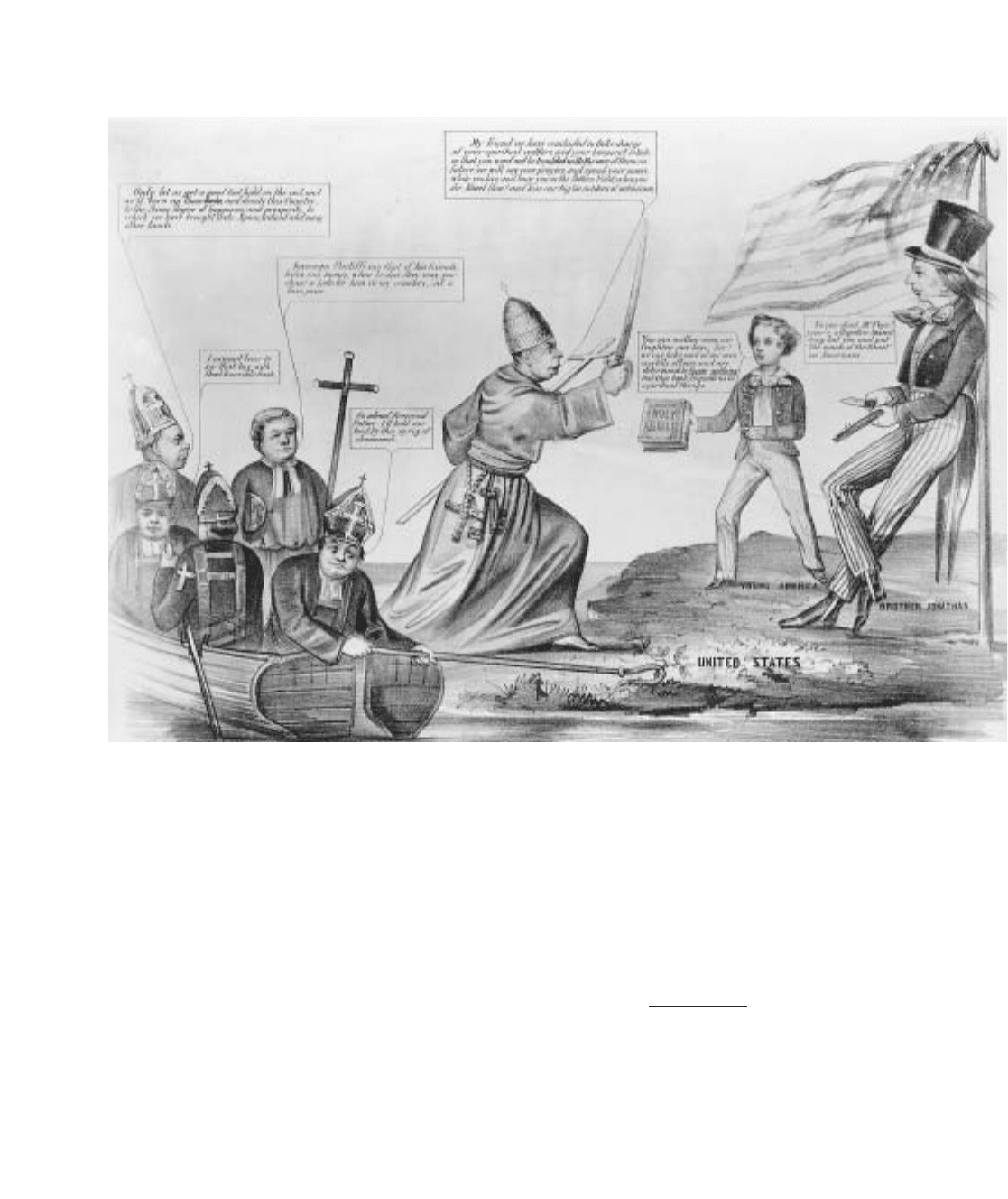

This anti-Catholic cartoon from 1855, reflects the nativist perception of the threat posed by the Roman Catholic Church’s

influence in the United States through Irish immigration and Catholic education.The headline read: “The Propagation Society.

More Free Than Welcome.” The “Propagation Society” is probably the Catholic proselytizing organization the Society for the

Propagation of the Faith. At right, on a shore marked “United States,” Brother Jonathan, whittling, leans against a flagpole flying the

stars and stripes.“Young America,” a boy in a short coat and striped trousers, stands at left, holding out a Bible toward Pope Pius

IX, who steps ashore from a boat at left.The latter holds aloft a sword in one hand and a cross in the other. Still in the boat are

five bishops. One holds the boat to the shore with a crozier hooked around a shamrock plant.The pope says,“My friend we have

concluded to take charge of your spiritual welfare, and your temporal estate, so that you need not be troubled with the care of

them in future; we will say your prayer and spend your money, while you live, and bury you in the Potters Field, when you die.

Kneel then! And kiss our big toe in token of submission.” Brother Jonathan responds,“No you don’t, Mr. Pope! You’re altogether

too willing; but you can’t put ‘the mark of the Beast’ on Americans.” Young America says, “You can neither coax, nor frighten our

boys, Sir! We can take care of our own worldly affairs, and are determined to Kno

w nothing but this book, to guide us in spiritual

things.” (“Know nothing” is a double entendre, alluding also to the nativist political party of the same name.) The first bishop

reacts, “I cannot bear to see that boy, with that horrible book.” Then the second bishop adds,“Only let us get a good foothold

on the soil, and we’ll burn up those Books and elevate this Country to the Same degree of happiness and prosperity, to which we

have brought Italy, Spain, Ireland and many other lands.” The third bishop notes,“Sovereign Pontiff! Say that if his friends, have any

money, when he dies; they may purchase a hole for him in my cemetery, at a fair price.” The fourth bishop says, “Go ahead

Reverend Father; I’ll hold our boat by this sprig of shamrock.”

(Peter Smith [i.e. Nathaniel Currier]/Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-30815])

For almost two decades following the Civil War

(1861–65), immigration proceeded without strong nativist

opposition. The presence of large numbers of Chinese in the

West during the economic slump of the late 1870s and the

rapid rise of immigration from southern and eastern Europe

after 1882 laid the foundation for a renewed tide of nativism

that exercised varying degrees of influence between 1885

and 1895. Rather than religion, however, most nativists of

this era were fearful of either racial or political incursions.

Perceiving an unacceptable level of Chinese influence, the

U.S. Congress framed the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

in

1882, although it was considered by most American politi-

cians to be exceptional legislation and not aimed at limiting

immigration generally. The Haymarket bombing in Chicago

in 1886, for which several German anarchists were con-

victed and hanged, confirmed for many Americans the

inferred link between aliens and radical politics, going back

to the M

OLLY

M

AGUIRE

riots and the violent railroad strikes

of the 1870s. Although the I

MMIGRATION

R

ESTRICTION

L

EAGUE

, founded in 1894, was at first unsuccessful, it grad-

ually chipped away at the open door for immigration, lead-

ing to rising immigrant head taxes, greater restrictions on

Asian immigration, and finally, after four presidential vetoes,

implementation of a literacy test in the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1917.

The theory of racial eugenics and international politics

combined during World War I (1914–18) to produce an

especially virulent strain of nativism. Widely read pseudo-

scientific works such as Madison Grant’s Passing of the Gr

eat

R

ace (1916) and Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color

(1920) argued that Anglo-Saxon vitality and success were

threatened with mongrelization if immigration continued

unabated. Accor

ding to G

rant, interracial unions led to

reversions to a “more ancient, generalized and lower” race.

Blaming the Central Powers for World War I and Russians

and Jews for the Bolshevik Revolution, which led to the

establishment of the world’s first communist state in 1917,

Americans widely accepted the distinction between “old,”

pre-1880 immigration from western and northern Europe,

and “new,” post-1880 immigration from southern and east-

ern Europe. Throughout much of the 1920s, fear of Ger-

man, Russian, and Jewish subversives was commonplace and

led to a revival of the Ku Klux Klan as an antiforeign orga-

nization and to a wholesale adoption of restrictive immi-

grant legislation with the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924) and

the O

RIENTAL

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1924), the former practi-

cally eliminating immigration from eastern and southern

Europe and the latter prohibiting virtually all Asian immi-

gration.

Although nativism declined somewhat in the late

1920s, U.S. immigration policy remained consistently

restrictionist until World War II (1939–45). Father Charles

Coughlin, head of the Christian Front against communism,

spoke out against the “problem” of the American Jew,

another manifestation of nativism, to an estimated 30 mil-

lion listeners during the mid-1930s. Nativism undoubtedly

contributed to President Franklin Roosevelt’s unwillingness

to support the Wagner-Rogers Bill (1939), which would

have allowed annual admission beyond quotas, for two

years, of 20,000 German refugees under the age of 14. Also

during the depression years of the 1930s, more than

500,000 Mexican Americans were repatriated to Mexico.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, restrictions

on immigration were increased. Fear of undercover agents

led to a drastic reduction of admissions from Nazi-occupied

countries, the Alien Registration Act was passed in 1940, the

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) was

moved from the Department of Labor to the Department of

Justice, and a network of law enforcement agencies was

authorized to compile a list of aliens for possible intern-

ment should the United States enter the war. This eventually

led to the internment of some 3,500 Italians, 6,000 Ger-

mans, and, under the provisions of Executive Order 9066,

113,000 Japanese, more than 60 percent of whom were

American citizens (see J

APANESE INTERNMENT

,W

ORLD

W

AR

II). Nativism began to ebb after World War II. The

M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZA

-

TION

A

CT

(1952) maintained quotas but eliminated race as

a barrier. U.S.

COLD WAR

commitments led to the admis-

sion of a variety of refugees (see

REFUGEE RELIEF ACT

) on an

exceptional basis. Finally, the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATION

-

ALITY

A

CT

of 1965 abolished the national origins system

and favored reunification of families, regardless of home-

land.

The massive influx of Mexicans, especially illegal aliens,

fueled a new round of nativism in the United States during

the 1980s. In 1983, the Official English movement was

launched in response to the growth of bilingualism, which

had become common in the public schools in the 1970s to

accommodate the increasing number of Spanish-speaking

children. By the late 1980s, it became clear that Official

English was closely linked to various restrictionist move-

ments, including the controversial Pioneer Fund that sup-

ported eugenics research. Restrictionists redoubled their

efforts when the I

MMIGRATION

R

EFORM AND

C

ONTROL

A

CT

(IRCA) legalized the status of nearly 3 million undoc-

umented aliens. Although restrictionists enjoyed little suc-

cess nationally, they did help organize the drive for

P

ROPOSITION

187 in California, which denied many gov-

ernment services to illegal aliens, including public educa-

tion. Although the measure was declared unconstitutional,

it clearly reflected the views of almost 60 percent of Califor-

nians who were concerned about the growing cost of pro-

viding services and the potential difficulty in assimilating

such a large Mexican population. Californians spoke again

in 1998 when they passed Proposition 227, giving immi-

grant children only one year to learn English before entering

mainstream classes. With nativist movements in the 1980s

NATIVISM 199

and 1990s largely localized, a general equilibrium regard-

ing immigration appeared to take hold. But the terrorist

attacks of S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001, fueled fears regarding

Arab and Muslim immigrants, leading to an extensive

national debate on the compatibility of Islam and Ameri-

can political values.

Further Reading

Asher, Robert, and Charles Stephenson. L

abor Divided: Race and Eth-

nicity in the United States Labor Struggles, 1835–1960. Albany:

State U

niversity of New York Press, 1990.

Bennett, David. The P

arty of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New

Right in A

merican History. 2d ed. New York: Vintage Books,

1995.

B

illington, Ray Allen. The P

rotestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of

the Origins of A

merican Nativism. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Bosniak, Linda. “‘Nativism’ the Concept: Some Reflections.” In Immi-

gr

ants O

ut! The New Nativism and the Anti-Immigrant Impulse in

the United States. Ed. Juan Perea. New York: New York University

P

r

ess, 1997.

Grant, Madison. The Passing of the Great Race. 4th ed. New York:

Charles Scribner

’

s Sons, 1922.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism,

1860–1925. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press,

1988.

Knobel, D

ale T. “America for the Americans”: The Nativist Movement in

the United S

tates. New York: Twayne, 1996.

Kraut, Alan. Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Men-

ace.

” N

ew York: Basic Books, 1994.

Malkin, Michelle. Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists,

Criminals and O

ther Foreign Menaces to Our Shores. New York:

Regnery, 2002.

P

almer

, Howard. Patterns of Prejudice: A History of Nativism in Alberta.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

Reimers, David. Unwelcome Strangers: A

merican Identity and the Turn

against Immigration. New York: Columbia University Press,

1998.

R

obin, M

arin. Shades of Right: Nativist and Fascist Politics in Canada,

1920–1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Sanchez, George. “Face the Nation: Race, Immigration, and the Rise

of Nativism in Late-Twentieth-Century America.” International

Migration R

eview 31 (1997): 1,009–1,031.

Simcox, David. “Major Predictors of Immigration Restrictionism:

Operationalizing ‘Nativism.’” Population and Environment 19

(1997): 129–143.

Tenth Anniversary Oral History Project of the Federation for American

I

m

migration Reform. Washington, D.C.: Federation for American

Immigration Reform, 1989.

Naturalization Act (United States) (1802)

When Thomas Jefferson became president, there was a relax-

ation of the hostility toward immigrants that had prevailed

during the administration of John Adams (1797–1801). The

A

LIEN AND

S

EDITION

A

CTS

were repealed or allowed to

expire, and Jefferson campaigned for a more lenient natural-

ization law, observing that, under the “ordinary chances of

human life, a denial of citizenship, under a residence of four-

teen years, is a denial to a great proportion of those who ask

it.” On April 14, 1802, a new naturalization measure was

enacted, reducing the period of residence required for natu-

ralization from 14 to five years. In addition, the new law

required that prospective citizens give three years’ notice of

intent to renounce previous citizenship, swear or affirm sup-

port of the Constitution, renounce all titles of nobility, and

demonstrate themselves to be of “good moral character.” The

Naturalization Act was supplemented on March 26, 1804, by

exempting aliens who had entered the United States between

1798 and 1802 from the declaration of intention. The three-

year notice was reduced to two years on May 26, 1824.

Further Reading

Bromwell, William J. History of Immigration to the United States,

1819–1855. 1855. Reprint, New York: Augustus M. Kelley,

1969.

H

utchinson, E. P

. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

M

orrison, Michael A., and James Brewer Stewart, eds. Race and the

Early Republic: Racial Consciousness and Nation B

uilding in the

Early Republic. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Scott, K

enneth. E

arly New York Naturalizations Abstracts of Natural-

izations Records. Baltimore: Clearfied Company

, 1999.

Naturalization Acts (United States) (1790, 1795)

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was the first piece of U.S.

federal legislation regarding immigration. It was designed

to provide a national rule for the process of naturalization.

As a result of varying policies among the states for nat-

uralizing citizens during the 1780s, the U.S. government

passed “an act to establish an uniform rule of naturaliza-

tion” on March 26, 1790. Under provisions of Article I,

Section 8, of the Constitution, the measure granted citi-

zenship to “all free white persons” after two years’ residence

and provided that the children of citizens born outside the

borders of the United States would be “considered as natu-

ral born citizens.”

A new Naturalization Act was passed on January 29,

1795, repealing the first act, raising the residency require-

ment to five years, and requiring three years’ notice of intent

to seek naturalization. This greater stringency regarding the

naturalization of immigrants was continued in the A

LIEN

AND

S

EDITION

A

CTS

(1798).

Further Reading

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

200 NATURALIZATION ACT

Morrison, Michael A., and James Brewer Stewart, eds. Race and the

Early Republic: Racial Consciousness and Nation Building in the

Early Republic. Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Scott, K

enneth. Early New York Naturalizations Abstracts of Natural-

izations Records. Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 1999.

navigation acts

The navigation acts were a number of related legislative

measures passed between 1651 and 1696 and designed to

enhance Britain’s international economic position. They

reflected the mercantilistic concern for economic control of

colonies and a favorable balance of trade and collectively

provided a blueprint for management of Britain’s first

empire.

The Navigation Act of 1651, leading to the First Dutch

War, required that all goods from Africa, Asia, and the

Americas be imported to England in English ships and that

all European goods shipped to England be carried in English

ships or the ships of the country producing the goods. The

First Navigation Act (1660) reinforced the previous provi-

sions, adding that crews had to be at least 75 percent English

and establishing a list of enumerated colonial goods, not

produced in England, that could be supplied only to En-

gland or other British colonies. The original articles included

sugar, cotton, indigo, dyewoods, ginger, and tobacco; rice,

furs, molasses, resins, tars, and turpentine were later added. It

also provided that only English or colonial ships could carry

trade to and from the British colonies. The Staple Act of

1663 required that most foreign goods be transshipped to the

American colonies through British ports. When enumerated

articles passed through British ports, heavy duties were levied

on them. The British government did seek to protect some

American products, however, levying high tariffs on Swedish

iron and Spanish tobacco and prohibiting the raising of

tobacco in England. The last major piece of mercantile legis-

lation was passed in 1696, expanding the limited British cus-

toms service and establishing vice-admiralty courts to quickly

settle disputes occurring at sea. Closely related to the naviga-

tion acts were laws passed throughout the colonial period

limiting the sale of American grain in England and inhibit-

ing the development of American industries, including tex-

tiles, timber, and iron.

The navigation acts were aimed principally at the

Dutch, who had controlled much of the world’s middle-

man trade in the first half of the 17th century, and at emerg-

ing American industries poised to compete with the mother

country. Among agriculturalists, small tobacco planters were

especially hard hit, but on the whole the northern colonies

suffered more as a result of the regulations. New England

merchants routinely carried on commerce in violation of the

acts throughout the 17th century. By the beginning of the

18th century, most smuggling from Europe had been

stopped, and Americans had grown accustomed to purchas-

ing English goods, which they preferred to local manufac-

tures. After passage of the Molasses Act (1733), however,

which raised prohibitive duties on molasses and sugar from

the French West Indies and threatened American trade,

smuggling again increased. Following the Seven Years’ War

(1756–63), new legislation utilized the navigation acts as a

means of raising revenue for the British treasury and as a

result raised the ire of American colonists.

Further Reading

Andrews, C. M. The Colonial Period of American History, Vol. 4. New

Haven, Conn.:

Yale University Press, (1938).

Beer, George L. The Commercial Policy of England toward the American

Colonies. New York: P. Smith, 1948.

———. The Old Colonial System, 1660–1754. New York: P. Smith,

1933.

D

ickerson, O. M. The N

avigation Acts and the American Revolution.

New York: Octagon Books, 1974.

Harper, L. A. The English Navigation Laws: A Seventeenth-century

Experiment in Social E

ngineering. New York: Octagon Books,

1939.

New Brunswick

Europeans first settled the New Brunswick region of Canada

in 1604, when Frenchmen S

AMUEL DE

C

HAMPLAIN

and

Pierre du Gua, sieur de Monts, established a fur-trading set-

tlement on St. Croix Island. The region surrounding the Bay

of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, known as A

CADIA

,

became a sparsely populated part of the larger French colo-

nial territory of N

EW

F

RANCE

. Acadia was officially trans-

ferred to Britain in 1713, though the French Acadians

remained in New Brunswick until the British drove them

out following the capture of the region during the French

and Indian War (1754–63). Between 1763 and 1784, New

Brunswick was a part the province of N

OVA

S

COTIA

.

The population of New Brunswick changed dramati-

cally during its first two decades in British hands. Traders

from New England began arriving in the principal city of St.

John in 1762 and in the following year established

Maugerville, near present-day Fredericton. Many Acadians

were allowed to return and were given land grants in the

northern and eastern parts of the region. Most important,

New Brunswick became one of the principal areas of reset-

tlement for the United Empire Loyalists, 1775–83, who had

refused to take up arms against the British Crown during the

American Revolution (see A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION AND

IMMIGRATION

). Close to 14,000 landed at St. John in 1783

and were given land in the sparsely settled St. John River val-

ley, where they founded Fredericton. In 1784, New

Brunswick was made a separate province.

After 1815, hard times in Britain drove thousands of

English, Scotch, and Irish settlers to New Brunswick. With

increasing population came heightened tensions over the

NEW BRUNSWICK 201

undefined border between New Brunswick and Maine and

greater desire for self-government. In 1837, Britain turned

over crown lands to New Brunswick and in 1842 negotiated

a delimitation of the New Brunswick–Maine boundary. The

province gained self-government in 1848. In 1867, New

Brunswick joined Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec as an

original member of the Dominion of Canada.

Further Reading

Brown, Wallace. The King’s Friends: The Composition and Motives of the

American Loyalist Claimants. Providence, R.I.: Brown University

P

ress, 1965.

Careless, J. M. S., ed. Colonists and Canadiens, 1760–1867. Toronto:

M

acmillan of Canada, 1971.

Co

wan, Helen I. British Emigration to British North America: The

F

irst H

undred Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961.

Ells, M

argaret. “Settling the Loyalists in Nova Scotia.” Canadian His-

torical Association R

eport for 1934. Ottawa: Canadian Historical

Association, 1934.

J

ohnson, S

tanley. A History of Emigration from the United Kingdom to

Nor

th America, 1763–1912. London: George Routledge and

Sons, 1913.

M

acNutt, W. S. The Atlantic Provinces: The Emergence of Colonial Soci-

ety

, 1712–1857. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1965.

———. New Brunswick: A History, 1784–1867. Agincourt, Canada:

G

age, 1984.

M

oore, Christopher. The Loyalists: Revolution, Exile, Settlement.

Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1984.

W

ilson, Bruce. Colonial Identities: Canada from 1760–1815. Ottawa:

National Archives of Canada, 1988.

Wynn, Graeme. Timber Colony: A Historical Geography of Ear

ly Nine-

teenth Century New Brunswick. Toronto: University of Toronto

Press, 1981.

Newfoundland

Newfoundland comprises the island of Newfoundland and

the nearby coast of the mainland region of Labrador. The

rocky terrain and cold and stormy weather inhibited tradi-

tional settlement, but the rich fisheries of the North Atlantic

provided a livelihood for hardy fishermen from the earliest

European contact. Vikings established settlements along

the northern coast of Newfoundland around the year 1000

but left the region soon after. English fishermen may have

reached the island in the 1480s, and John Cabot brought

news of the fisheries back after his voyage of 1497. From

that time forward, English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish

fishermen plied the rich waters but established no perma-

nent settlements. Although Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed

the land for England in 1583, the reality was that each coun-

try operated from temporary working camps and that the

master of the first ship to arrive during a fishing season in

each harbor was designated the fishing admiral and assumed

ultimate authority along the local coasts. Attempts by

English proprietors to establish colonial settlements failed at

Cupids on Conception Bay (1610) and Ferryland (1621,

1637–51).

France established the first heavily fortified colony at

Placentia in 1662 and developed a string of trapping posts

along the coast of Labrador during the first half of the 18th

century. Newfoundland became a battleground during the

War of the League of Augsburg (1689–98), the War of the

Spanish Succession (1702–14), and the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63). By provision of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713),

Britain gained the entire island of Newfoundland, though

France retained use of the northern and western shore

(French Shore) for drying fish. By the Treaty of Paris (1763),

France gave up all claims to mainland North America but

was given the small islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

off the southern coast of Newfoundland and retained its

fishing privileges on the French Shore, which were not relin-

quished until 1904.

Britain never regarded Newfoundland as a settlement

colony, favoring the rights of fishing interests. This policy is

reflected in the appointment of naval officers as royal gover-

nors. Although most of the frontier regions of the island

were settled by the 1840s, explorers of the Hudson’s Bay

Company were at that time just beginning to regularly

probe the interior of Labrador. The majority of immigrants

were from Ireland and the west of England. Largely barren,

Labrador was administered by Newfoundland (1763–74,

1809–25) and Q

UEBEC

(1774–1809) before it was divided

between the two provinces in 1825. The present boundary

between Quebec and Labrador was finally established in

1927. Despite a population of only some 20,000, in 1832,

the British government acceded to demands for a strong

local government, allowing a representative general assem-

bly. In 1855, Newfoundland was granted responsible gov-

ernment, with the cabinet answerable to the assembly rather

than to the governor. Newfoundland became the 10th

province of the Dominion of Canada in 1949. The discov-

ery of copper in the 1850s and iron in the 1890s led to the

development of a significant mining industry in Labrador,

though fishing remained Newfoundland’s principal eco-

nomic resource.

Further Reading

Davies, K. G., ed. Northern Quebec and Labrador Journals and Corre-

spondence, 1819–35. V

ol. 24. London: Hudson’s Bay Record

Society

, 1963.

Handcock, W. Gordon. “Soe long as there comes noe women”

:

Origins of

English Settlement in Newfoundland. St. John, Canada: Breakwa-

ter Pr

ess, 1989.

New France

New France was the name of the French colonial empire in

North America. The coastal regions, claimed in the 1530s

by J

ACQUES

C

ARTIER

, were gradually augmented by French

202 NEWFOUNDLAND

explorers and fur traders. In a series of wars for control of

North America (1689–1763), virtually all of New France

was lost to the British, the final blow coming with the

S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63). During the entire period

of French control, only about 12,000 permanent settlers

immigrated to New France, with concentrations in three

regions: the fur-trading region along the St. Lawrence Sea-

way, known as Canada (see C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SUR

-

VEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

); the Atlantic settlements,

known as A

CADIA

; and the interior watershed, known as

L

OUISIANA

. Despite limited settlement, French occupation

led to a permanent French culture pattern in modern Q

UE

-

BEC

and a distinctive French influence in modern Louisiana.

During the 16th century, there was little interest in set-

tling any part of New France. Cartier had observed of the

rocky coast of Labrador, that this must have been “the land

God gave to Cain.” In 1541, he and the seigneur de Rober-

val (Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval) attempted to

establish the colony of Charlesbourg-Royal, near present-

day Quebec City, but it was abandoned in the following

year. Fishermen continued to ply the rich waters off New-

foundland, and merchants gradually developed a lucrative

trade in furs with the Native Americans along the Atlantic

and St. Lawrence coastal areas. The French government

encouraged development by granting trade monopolies, but

early settlements on the Magdalen Islands, Sable Island,

Tadoussac, and St. Croix Island all failed.

S

AMUEL DE

C

HAMPLAIN

founded the first permanent

French settlement at Quebec in 1608, a fur-trading post that

linked France with the vast interior regions of North Amer-

ica and formed the core of the Canada settlement. Along

with the commercial impulse came missionaries. In 1642,

the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion

des Sauvages de la Nouvelle France founded Ville Marie,

later known as Montreal. Administrative mismanagement,

failure to secure settlers, and the constant threat from local

native groups brought a complete reorganization of the gov-

ernment, which was brought under royal control in 1663.

During the intendancy of J

EAN

T

ALON

(1663–72), new

energy was brought to the governance of the region. A

benevolent autocracy was established in which trade was

diversified, western expansion was encouraged, and planned

immigration was pursued. Through an agreement with the

French West Indies Company, between 1663 and 1673, sev-

eral thousand settlers arrived, most from Brittany and Île-de-

France, though some were recruited from Holland, Portugal,

and various German states. Among this wave of immigrants,

however, were few families. Most were trappers, soldiers,

churchmen, prisoners, and young indentured servants (see

INDENTURED SERVITUDE

); by 1672, all plans for systematic

immigration were stopped. After 1706, merchants from a

number of European countries and their local agents were

granted permission to do business in Canada, leading to a

thriving trade in Quebec and Montreal. Indentured servants

occasionally came, and soldiers who were stationed in the

colony as a result of the ongoing conflict with Britain some-

times stayed on. The number of slaves was always small, per-

haps 4,000 Native American and African slaves for the entire

duration of New France. More than a thousand convicts

were forcibly transported. Remarkably, from this miscella-

neous and meager collection of 9,000 immigrants, the pop-

ulation of Canada swelled to 70,000 at the time of the Seven

Years’ War.

In the 1630s, the French government had great hopes

for establishing an outpost in Acadia to combat the rapidly

growing population of the British colonies in New England.

When a settlement plan for Nova Scotia foundered, the gov-

ernment offered little additional support. As a result, the

small Acadian population was forced to become self-reliant,

and many enjoyed closer commercial contacts with New

England than with Canada. When Nova Scotia was ceded to

Britain (1713) at the end of the War of the Spanish Succes-

sion, France focused Acadian development on the almost

uninhabited but strategically located Île Royale (later Cape

Breton), where it founded Louisbourg. During the next 45

years, Louisbourg developed into an important commercial

city and fishing port and boasted one of the strongest forti-

fied posts in North America. Although numbering several

thousand inhabitants by the mid-18th century, Louisbourg

fell victim to the international rivalry between Britain and

France. It was captured by Britain in 1745 during the War

of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) but returned at war’s

end. It was seized again in 1758, during the Seven Years’

War. With formal capitulation to Britain in 1760, most of

the French inhabitants either returned to Europe or

migrated to Louisiana leaving only about a thousand settlers

throughout Acadia.

French expansion into the Great Lakes and the interior

waterways was spurred by the intrepid coureurs de bois (for-

est runners). Their restless search for new sources of furs and

their native lifestyle, often taking Indian wives, greatly

extended French commercial influence. Behind them came

the explorers and churchmen. In 1673, Louis Jolliet and Jesuit

Jacques Marquette explored the upper reaches of the Missis-

sippi River, and in 1682, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle

followed the entire course of the river to the Gulf of Mexico,

claiming for France all the lands drained by its tributaries and

naming the region Louisiana, in honor of Louis XIV (r.

1648–1715). Only slowly did the French government follow.

Louisiana was officially established as a colony in 1699. In

order to meet the growing threat from Spain in the south and

Britain on the Atlantic seaboard, France then built a string of

forts from the Great Lakes along the interior waterways,

including Natchitoches on the Red River (1714), the first per-

manent settlement, and N

EW

O

RLEANS

(1718) at the mouth

of the Mississippi. Between 1712 and 1731, Louisiana was a

proprietary colony, with exclusive trading rights and failed set-

tlement schemes passing from one hand to another. It then

NEW FRANCE 203