Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the 2000 U.S. census and the 2001 Canadian census,

198,203 Americans and 16,950 Canadians claimed Laotian

descent. In addition, 186,310 Americans were from the Lao-

tian minority Hmong. Unlike earlier post-1960s immigrant

groups that tended to cluster in large cities, Laotian refugees

were often settled in medium-sized cities, especially in Cal-

ifornia, including Fresno, San Diego, Sacramento, and

Stockton. The Hmong were widely spread but most

prominent in California and Minnesota. The largest Lao-

tian concentrations in Canada were in Toronto and Mon-

treal. In 2001, there were fewer than 600 Hmong in

Canada.

Laos is a landlocked country occupying 89,000 square

miles in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and

China on the north, Vietnam on the east, Cambodia on the

south, and Thailand on the west. In 2002, the population

was estimated at 5,635,967. The people are ethnically

divided between Lao Lourn (68 percent), Lao Theung (22

percent), Lao Soung, including Hmong and Yao (9 percent).

About 60 percent are Buddhist, and 40 percent practice ani-

mist or other religions Laos gained its independence from

the Khmer Empire (modern Cambodia) during the 14th

century, peaking in regional influence late in the 17th cen-

tury. Laos became a French protectorate in 1893 but

regained independence as a constitutional monarchy in

1949. Conflicts among neutralist, Communist, and conser-

vative factions created a chaotic political situation. Armed

conflict increased after 1960. Three factions formed a coali-

tion government in June 1962, with neutralist Prince Sou-

vanna Phouma as premier. With aid from North Vietnam,

Communist groups stepped up attacks against the govern-

ment, and Laos was gradually drawn into the

COLD WAR

conflict in Southeast Asia. In 1975, the Lao People’s Demo-

cratic Republic was proclaimed, with thousands of Laotians

fleeing to refugee camps in Thailand.

There is no official record of Laotian immigration to

the United States prior to 1975, though there was a small

number of professionals who had come before that time. In

1975, those who had aided the United States and South

Vietnam during the Vietnam War fled to refugee camps in

Thailand, which housed more than 300,000 by the mid-

1980s. As the condition of Laotian refugees became more

widely known, there was general support in both the United

States and Canada for assisting them. The U.S. government

passed a special measure, the Indochina Migration and

Refugee Assistance Act (1975), that eased entry into the

country. In 1978, the Canadian government designated the

Indochinese one of three admissible refugee classes. Between

1976 and 1981, more than 120,000 Laotian refugees were

admitted to the United States and almost 8,000 to Canada.

Because most were aided in resettlement by private organi-

zations, they tended to be spread widely throughout both

the United States and Canada. Between 1992 and 2002, an

average of about 3,000 immigrants from Laos arrived in the

United States annually, though the numbers declined signif-

icantly after 1997. Fewer than 1,700 of Canada’s 14,000

Laotian immigrants came after 1990.

Further Reading

Adelman, Howard. Canada and the Indochinese Refugees. Regina,

Canada: L. A. W

eigl Educational Associates, 1982.

Chan, S., ed. Hmong Means Free: Life in Laos and America. Philadel-

phia:

T

emple University Press, 1994.

De Voe, Pamela. “Lao.” In Case Studies in Diversity: Refugees in Amer-

ica in the 1990s. Ed. David W. Haines. Westport, Conn.: Praeger,

1997.

D

orais, Louis-Jacques. The Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in

Canada. O

ttawa: Canadian Historical Association, 2000.

Dorais, Louis-J

acques, Kwok B. Chan, and Doreen M. Indra, eds. Te n

Years Later: I

ndochinese Communities in Canada. Montreal: Cana-

dian Asian Studies Association, 1988.

H

aines, David W., ed. Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotians,

and

V

ietnamese in America. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Little-

field, 1989.

H

ein, J

eremy. From Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia: A Refugee Experience

in the United S

tates. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Koltyk, Jo Ann. New Pioneers in the Heartland: Hmong Life in Wis-

consin. N

eedham Heights, Mass.: Allyn and Bacon, 1997.

O’Connor,

Valerie. The Indochina Refugee Dilemma. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State Univ

ersity Press, 1990.

Proudfoot, Robert. Even the Birds Don’t Sound the Same Here: The Lao-

tian R

efugees

’ Search for Heart in American Culture. New York:

Peter Lang, 1990.

R

umbaut, Rubén G. “A Legacy of War: Refugees from Vietnam, Laos

and Cambodia.” In Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race and

E

thnicity in America. Eds. Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut.

Belmont, Calif

.: Wadsworth, 1996.

Van Esterik, Penny. Taking Refuge: Lao Buddhists in N

o

rth America.

Tempe: Arizona State University Press, 1992.

La Raza Unida Party (LRUP)

The La Raza Unida Party (LRUP) was the first attempt to

cr

eate a national political party to represent the rights of

Mexican Americans. South Texas leaders had formed La

Raza Unida in 1970 in order to elect Mexican Americans to

local school boards and councils. The greatest successes

came in Crystal City, Texas, where LRUP gained control of

the city council and school board, enabling it to hire more

Mexican-American employees, institute bilingual educa-

tional programs, and add Mexican-American history to the

curriculum. Organizers spread throughout the Southwest

to establish branches. By 1972, other activist organizations

began to join the effort. At the 1972 El Paso convention of

the Crusade for Justice, Chicano leader C

ORKY

G

ONZALES

called for creation of a national party. Students, journalists,

and activists from many groups, including R

EIES

L

ÓPEZ

T

IJERINA

’s Alianza Federal de Mercedes, attended the con-

vention, which led to the establishment of the national

174 LA RAZA UNIDA PARTY

LRUP. The party received 215,000 votes (almost 7 percent)

in the 1972 state election, but it received little support else-

where.

See also M

EXICAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Corona, Bert. Bert Corona Speaks on La Raza Unida Party and the “Ille-

gal A

lien” Scare. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1972.

Gar

cía, Ignacio M. “Armed with a Ballot: The Rise of La Raza Unida

Party in Texas.” M.A. thesis, University of Arizona, 1990.

Muñoz, Carlos. Youth, Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement. Lon-

don: V

erso, 1989.

Rosales, Francisco A. Chicano!: A History of the Mexican American

C

ivil Rights M

ovement. Houston, Tex.: Arte Público Press, 1996.

Santillán, Richar

d. The Politics of Cultural Nationalism: El Partido de

la Raza U

nida in Southern California, 1969–1978. Ann Arbor,

Mich.: U

niversity Microfilms International, 1983.

Shockley, John. Chicano Revolt in a Texas Town. Notre Dame, Ind.:

U

niv

ersity of Notre Dame Press, 1974.

Vargas, Zaragosa. Major P

roblems in Mexican American History.

Boston: H

oughton Mifflin, 1999.

Vento, Arnoldo Carlos. M

estizo: The History, Culture, and politics of the

Mexican and the Chicano:

The Emerging Mestizo-Americans. Lan-

ham, Md.: U

niversity Press of America, 1997.

Latinos See H

ISPANIC AND RELATED TERMS

; T

EJANOS

.

Latvian immigration

According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian

census of 2001, 87,564 Americans and 22,615 Canadians

claimed Latvian descent. Generally, Latvians did not form

strong ethnic communities and were spread throughout

many larger North American cities, including New York,

Boston, Philadelphia, and Toronto. About two-thirds of

Canadian Latvians live in Ontario.

Latvia is a country of 24,938 square miles situated on

the Baltic Sea. It is bordered by Estonia on the north, Rus-

sia on the east, and Belarus and Lithuania on the south.

The region was settled by Baltic peoples in ancient times but

was ruled at various times by the Vikings, Germans, Poles,

Swedes, and Russians. As a result of Russian occupation in

the 18th century, about 30 percent of the present-day pop-

ulation is Russian, while 58 percent is Latvian, 4 percent

Belarusian, 2.7 percent Ukrainian, and 2.5 percent Polish.

About 40 percent of the population is Christian, almost

equally divided between Protestants and Roman Catholics;

60 percent are largely unreligious.

Latvian immigrants were historically divided and thus

did not form the strong ethnic communities common to

many immigrant groups from eastern Europe. “Old Lat-

vians” settling in the United States prior to World War II

(1939–45) were usually young and single. Most were seek-

ing economic opportunities, though a significant number

were political activists. The latter were divided among

nationalists, seeking the independence of Latvia from Rus-

sia, and socialists, who were more concerned with the con-

dition of workers under the Russian system. Latvian

immigration increased following the abortive Revolution of

1905. There was little immigration between World War I

(1914–18) and World War II. Because Latvian immigrants

were usually included in statistics as Russians, it is difficult

to know exactly how many came during this early phase of

immigration. By 1940, about 35,000 people claimed Lat-

vian descent; it is estimated that some 25,000 Latvians

immigrated to the United States prior to that time. The

“New Latvian” group was created when the conflict between

Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany left almost a quarter mil-

lion Latvians in refugee camps after World War II. About

40,000 of these immigrated to the United States as displaced

persons after 1946. Unlike the Old Latvians, they tended to

see themselves as only temporarily displaced, though most

chose to remain in the United States after the breakup of the

Soviet Union and the establishment of an independent

Latvia in 1991. Between 1992 and 2002, Latvian immigra-

tion to the United States averaged about 600 per year.

Few Latvians settled in Canada before World War II.

Between 1921, when Latvians were first categorized as a

group distinct from Russians, and 1945, only 409 arrived

in Canada. Almost all Latvian Canadians were part of or

are descended from, refugees and displaced persons who

arrived between 1947 and 1957. Whereas the Old Latvians,

who had come prior to the war, lived principally in Alberta,

Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, more than two-thirds of the

New Latvians chose Ontario. In 2001, about two-thirds of

all Latvian Canadians live in Ontario, and about half of

them in Toronto. Though many Latvians immigrated to

Canada with professional training, they often worked in

construction or related trades upon arrival. By the 1970s,

they were moving back into skilled positions, especially

engineering for men and medicine for women. Immigration

from Latvia remained small between 1960 and 1990, gen-

erally fewer than 100 arriving in a year. Following indepen-

dence in 1991, immigration among Latvians increased

somewhat, as they sought economic opportunities within an

increasingly global economic system. Of 7,675 Latvian

immigrants in Canada in 2001, 5,155 (67 percent) arrived

before 1961. About 1,500 came between 1991 and 2001.

See also R

USSIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

OVIET IMMIGRA

-

TION

.

Further Reading

Karklis, Maruta, Liga Streips, and Laimonis Streips. The Latvians in

America, 1640–1973: A Chr

onology and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry,

N.Y.: O

ceana Publications, 1974.

Lieven, Anatoly. The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and

t

h

e Path to Independence. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University

Pr

ess, 1993.

LATVIAN IMMIGRATION 175

Plakans, Andrejs. The Latvians: A Short History. Stanford, Calif.:

Hoover Institution Press, 1995.

Tichouskis, Heronims. Latvies˘u trimdas desmit gadi (Ten Years of Lat-

vians in E

xile)

Toronto, 1954.

V

eidemanis, Juris. Social Change: Major Value Systems of Latvians at

Home, as R

efugees, and as Immigrants. Greeley: Museum of

Anthropology

, University of Northern Colorado, 1982.

Lebanese immigration

The Lebanese, among the earliest Middle Eastern immi-

grants to come to North America in significant numbers,

formed the largest Arab ethnic group in both the United

States and Canada. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 440,279 Americans and

143,635 Canadians claimed Lebanese descent. Lebanese

have settled widely throughout the United States, with sig-

nificant concentrations in New York, Massachusetts, and

Connecticut. About 41 percent of Lebanese Canadians live

in Ontario, though the greatest concentration is in Montreal.

Lebanon occupies 3,900 square miles in the Middle

East, along the eastern littoral of the Mediterranean Sea.

It is bordered by Syria on the north and east and Israel on

the south. In 2002, the population was estimated at

3,627,774. The people were 93 percent Arab—divided

among Lebanese (84 percent) and Palestinians (9 per-

cent)—and 6 percent Armenian. Lebanon is the only Arab

country with a significant Christian population. In 2002,

about 55 percent of Lebanese were Muslims, 37 percent

Christians, and 7 percent Druze. Modern Lebanon corre-

sponds roughly with the ancient seafaring state of Phoeni-

cia, which flourished during the first millennium

B

.

C

.

Never organized as an empire, it fell under the domina-

tion of successive large states, including Assyria, Babylon,

Persia, Greece, the Arab dynasties, and eventually the

Ottoman Empire, which ruled the region from the 16th

century to the end of World War I (1918). As France

gained increasing influence over the weakening Ottoman

Empire in the late 19th century, Lebanon was organized

as an autonomous region within the empire to provide

protection for persecuted Christians. Lebanon became a

mandated territory under French control following World

War I and gained full independence by 1946. With the

introduction of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian

refugees from Israel during the 1970s, the Christian gov-

ernment of Lebanon quickly lost power. The Palestine Lib-

eration Organization, with support from Syria, moved its

war effort against Israel to Lebanon. The ensuing civil war

from 1975 had not yet been fully resolved as of 2004.

It is difficult to provide a precise number of Lebanese

immigrants, for they were rarely designated as such.

Immigrants from the Ottoman Empire were usually clas-

sified in the category “Turkey in Asia,” whether Arab,

Turk, or Armenian. By 1899, U.S. immigration records

began to make some distinctions, and by 1920, the cate-

gory “Syrian” was introduced into the census. Most Syri-

ans were in fact Lebanese Christians, though religious

distinctions still were not noticed. The majority of Arabs

in North America are the largely assimilated descendants

of Christians who emigrated from the Syrian and

Lebanese areas of the Ottoman Empire between 1875 and

1920. Lebanese Christians were divided into several

branches, including Maronites, Eastern Orthodox, and

Melkites. As Christians living in an Islamic empire, they

were subject to persecution, though in good times they

were afforded considerable autonomy. During periods of

drought or economic decline, however, they frequently

chose to emigrate. Between 1900 and 1914, about 6,000

immigrated to the United States annually. Often within

one or two generations, these Lebanese immigrants had

moved into the middle class and largely assimilated them-

selves to American life. With passage of the restrictive

J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924, immigration dropped to a

few hundred per year. The next major migration of

Lebanese to North America came with the advent of civil

war in the 1970s. Most of these immigrants were, how-

ever, Shiite Muslims, inclined to maintain their culture

rather than assimilate and usually at odds with Lebanese

Christians already in the United States. Between 1988 and

2002, Lebanese immigration averaged just under 5,000

per year.

Significant Lebanese immigration to Canada began in

the 1880s. The immigrants were almost all Christians who

feared persecution, particularly in the wake of the mas-

sacres of 1860. Immigration began shortly thereafter,

though it was restricted to mostly poor, single young men.

By the 1880s, more families were emigrating, laying the

foundation for the Lebanese community in Canada, cen-

tered in Montreal. Lebanese emigration from the Ottoman

Empire peaked between 1900 and 1914 with an average

of 15,000 per year, before World War I virtually halted

immigration. Though most went to the United States,

Brazil, or Argentina, significant numbers came to Canada

as well. When Lebanon came under the protection of the

French as a result of the Treaty of Versailles, many

Lebanese immigrants returned to their homeland during

the 1920s and 1930s.

As in the United States, most Lebanese immigrants

arrived before 1920 or after 1975. Of Canada’s 67,000

Lebanese immigrants, almost 60,000 came in the wake of

the political disruptions of the 1970s. In 1976, the Cana-

dian government created a special category for Lebanese

immigrants affected by the war and continued to apply

relaxed standards to Lebanese requests. After the 1989 peak

of 6,100 refugee arrivals, Lebanese immigration leveled off.

About 7,600 immigrants living in Canada in 2001 arrived

between 1996 and 2001.

See also A

RAB IMMIGRATION

.

176 LEBANESE IMMIGRATION

Further Reading

Jabbra, Nancy, and Joseph Jabbra. Voyageurs to a Rocky Shore: The

Lebanese and S

yrians of Nova Scotia. Halifax, Canada: Institute

of P

ublic Affairs, Dalhousie University, 1984.

Kayal, P. M., and J. M. Kayal. The Syrian Lebanese in America: A Study

in R

eligion and A

ssimilation. Boston: Twayne, 1975.

Naff

, Alixa. Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience.

Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press,

1985.

O

r

falea, Gregory. Before the Flames: A Quest for the History of Arab

Americans. A

ustin: University of Texas Press, 1988.

Shehadi, N

adim, and Albert H. Hourani, eds. The Lebanese in the

Wor

ld: A Century of Emigration. London and New York: I. B.

Tauris, 1993.

W

akin, Edward. The Syrians and the Lebanese in America. Chicago:

Clar

etian P

ublishers, 1974.

Walbridge, Linda S. Without Forgetting the Imam: Lebanese Shi’ism in

an A

merican Community

. Detroit: Wayne State University Press,

1996.

Liberian immigration

Liberia traditionally was not an important source country

for immigration to North America; however, political tur-

moil during the 1990s and into the 21st century and the

region’s special relationship to the United States led to a sig-

nificant increase in immigration. According to the U.S. cen-

sus of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 25,575

Americans and 640 Canadians claimed Liberian descent.

Some Liberian American groups estimate the numbers in

the United States to be much higher, mainly because of the

provisional status of large numbers of temporary admissions.

New York City and Washington, D.C., have the largest

Liberian populations.

Liberia comprises 37,743 square miles situated on the

West African Atlantic coast between Sierra Leone and

Guinea to the north and Côte d’Ivoire to the east. Estab-

lished as a refuge for freed American slaves in 1821, Liberia

displayed an unusual amount of political stability in an oth-

erwise unstable region. As a result, only a few thousand

Liberians immigrated to the United States during the first

eight decades of the 20th century. From 1980, however,

divisions between ethnic and culture groups became more

pronounced and political instability more common. The

most numerous ethnic groups included the Kpelle (19.4

percent), Bassa (13.9 percent), Grebo (9 percent), Gio (7.8

percent), Kru (7.3 percent), and Mano (7.1 percent). About

LIBERIAN IMMIGRATION 177

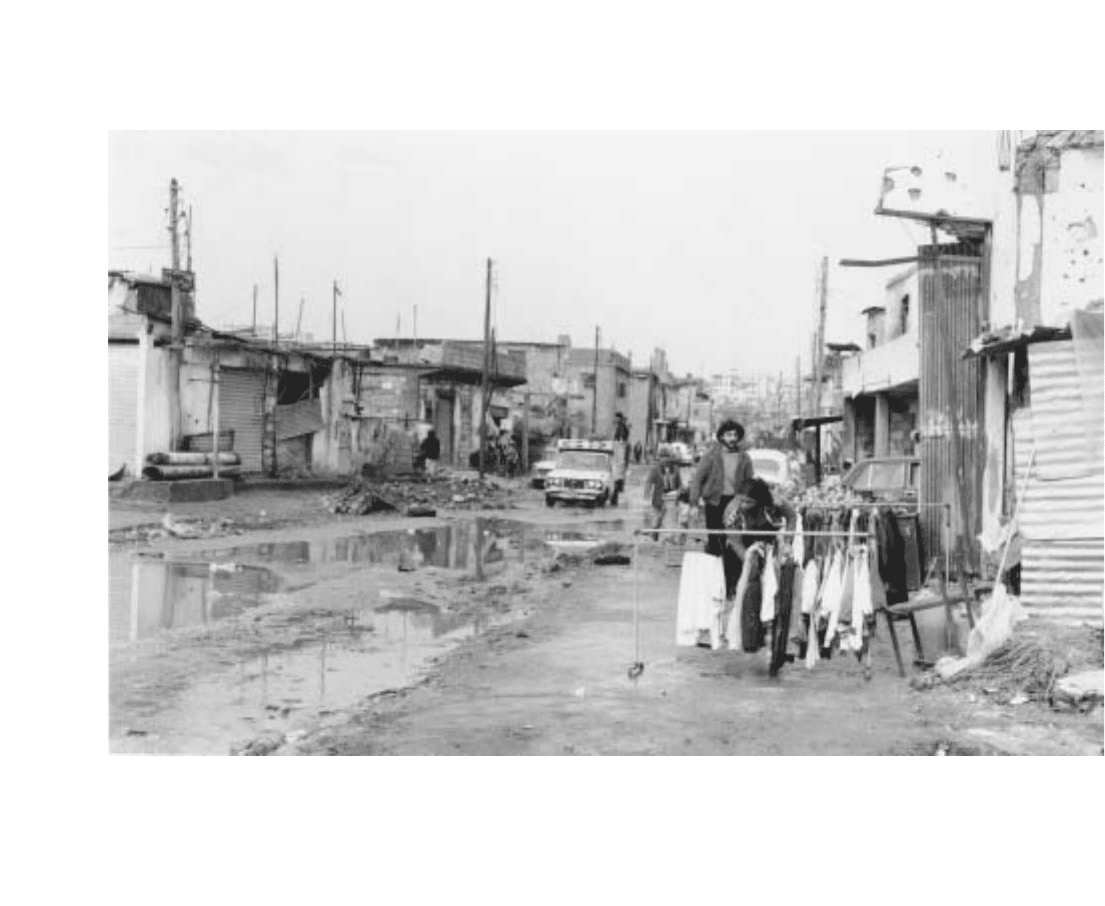

A street scene at the Sabra or Shatila refugee camp in southern Lebanon, 1983.The invasion of Lebanon by Israel in 1982 further

divided Christian and Muslim Lebanese communities in the United States and led to an increase in Lebanese refugees admitted to

both the United States and Canada.

(Photograph by Hariri-Rifai Makhless/Library of Congress [LC-USZ62-94063])

63 percent of Liberia’s 3.2 million people (2001) practice

native religions; 21 percent are Christians, and 16 percent,

Muslims. From its independence in 1847 until 1980,

Liberia was governed by the descendants of the original

African-American settlers. The last of these leaders, Presi-

dent William R. Tolbert, was assassinated during a 1980

coup that ushered in the violent dictatorship of Sergeant

Samuel Doe. The National Patriotic Front of Liberia

(NPFL) launched an invasion from the Côte d’Ivoire in

December 1989, leading to a vicious civil war that saw

250,000 killed and two-thirds of the country’s citizens dis-

placed. When fighting intensified in the capital of Monrovia

in April 1996, 20,000 people took refuge in the U.S.

embassy compound. In July 1997, NPFL leader Charles

Taylor was elected president with 72 percent of the vote.

Unique in its relationship to the United States, Liberia

received more emigrants from the United States than it sent

there from its founding in 1821 until the 1960s. As some

Liberians began to immigrate to the United States during

the 20th century, their numbers remained extremely small

through World War II (1939–45)—27 between 1925 and

1929; 30 between 1930 and 1939; 28 between 1940 and

1949. Though immigration grew in the 1950s and 1960s,

it still totaled only 800 for that 20-year period. The signifi-

cant period of Liberian immigration came only as a result

of the civil war waged between 1989 and 1997, when almost

17,000 Liberians entered the United States, many evacuated

in the last days of the war. Some were admitted as refugees,

but about 10,000 were granted Temporary Protected Status

(TPS), which ended in 1999. When TPS expired in Septem-

ber of that year, President Bill Clinton protected them from

removal under the Deferred Enforced Departure (DED)

program, which did not qualify immigrants for permanent

residency but allowed them temporary residency and per-

mission to work until dangerous and unstable conditions at

home allow a return. The DED status was then extended

annually, ensured at least through October 2004. From

1999, a number of members of Congress supported mea-

sures to regularize the status of Liberians under DED. In

2004, the Liberian Immigration Bill (S656) (H.R. 919) and

the Liberian Refugee Immigration Protection Act of 2003

were still in committee. Between 1998 and 2001, more than

10,000 Liberian refugees were admitted to the United

States, as well as 7,000 regular immigrants.

Further Reading

Alao, Abiodun, John MacKinlay, and Funmi Olonisakin. Peacekeepers,

Politicians, and

Warlords: The Liberian Peace Process. New York:

United N

ations University Press, 2000.

Huband, Mark, and Stephen Smith. The Liberian Civil War. Port-

land, O

r

e.: Frank Cass, 1998.

Trawally, Sidiki. “Prayers Answered: Liberians Granted TPS.” Liberian

Mandingo Association of New York. Available online. URL:

http://www.limany.org/straw.html. Accessed February 27, 2004.

Literacy Act See I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(United States)

(1917).

Lithuanian immigration

Lithuanian immigration to North America, spurred by eco-

nomic opportunity and political oppression, has been the

largest among the Baltic states. According to the 2000 U.S.

census and the 2001 Canadian census, 659,992 Americans

and 36,485 Canadians claimed Lithuanian descent. The

largest concentrations of Lithuanians were in Chicago, with

other significant settlements in Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit,

Michigan; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; New York City; and

Boston. Almost a third of Lithuanian Canadians live in

Toronto.

Lithuania occupies 25,212 square miles in the Baltic

region of northeastern Europe. In 2001, its population was

about 3.7 million people, with about 82 percent being eth-

nic Lithuanians; 8 percent, Russians; and 7 percent, Poles.

More than 72 percent of Lithuanians are Roman Catholic,

3 percent are Orthodox, and most of the rest are unreligious.

The region of modern Lithuania was settled by Baltic

peoples in ancient times. As Germans expanded eastward,

however, Lithuania developed a strong state and began to

expand to the east and south into Belarus and Kievan territo-

ries. Joining with Poland in 1386, the two powers combined

to form one of the largest states in Europe and gradually

halted the eastward advance of the Germans. Lithuanian

noblemen largely adopted Polish culture and developed a

political system that hampered development of a strong

monarchy. As a result, the Polish-Lithuanian state was parti-

tioned by 1795, and Russian domination of the region fol-

lowed until a declaration of independence in 1918. During

World War II (1939–45), Lithuania was invaded first by the

Soviet Union in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and

again by the Soviet Union in 1944. Thousands of Lithuanian

refugees fled from the Soviets, becoming displaced persons.

Many of them eventually sought refuge in the United States.

Because Lithuanian immigrants were usually included as

Russians in statistics prior to World War I (1914–18), it is

difficult to know exactly how many came prior to that time.

A significant number of Lithuanians first immigrated to the

United States after the Civil War (1861–65), in part because

the abolition of serfdom in the Russian Empire (1861) gave

the peasantry greater personal freedom, but also because of

an aggressive policy of russification after the failed uprising of

1863. A much larger wave of migration came between 1880

and 1914, with some estimates placing the number of immi-

grants as high as 300,000. Although emigration was illegal,

many political dissidents risked capture, and Jews were some-

times forced to emigrate. Between the 1860s and 1914,

almost 400,000 Lithuanians emigrated, about 20 percent of

the population and one of the highest rates of emigration in

Europe. The restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

ACT

of 1924 vir-

178 LITERACY ACT

tually halted Lithuanian immigration until after World War

II, when 30,000 refugees were admitted, many under the

D

ISPLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

(1948). Whereas earlier Lithua-

nian immigrants had been mainly laborers, the refugees fre-

quently came from middle- and upper-class backgrounds.

Although Lithuanians continued to immigrate to the United

States in small numbers—averaging a little more than 1,000

per year between 1992 and 2002—those claiming Lithua-

nian descent are fewer as assimilation and outmarriage occur.

In 1990, 811,865 Americans claimed Lithuanian descent, 23

percent higher than the 2000 figure.

Lithuanian immigration to Canada is usually divided

between the “Old Lithuanians,” who came up through the

1920s, and the “New Lithuanians,” mostly displaced per-

sons, who arrived after World War II. About 150 Lithuanian

soldiers fought for the British army in the War of 1812

(1812–15), and many were given land grants as a result.

There was no significant chain migration, however, so their

numbers remained small. In the 1880s and 1890s, few

Lithuanians came to settle, though many migrated between

the United States and Canada doing seasonal work. The first

separate listing of Lithuanians in the Canadian census was in

1921, when there were still fewer than 2,000 in Canada.

Twenty years later the official number was almost 8,000,

though the actual number was probably closer to 10,000.

Among these, a large percentage eventually migrated to the

United States, where jobs and pay were generally better.

The New Lithuanians of the post–World War II era were

considerably different. Whereas many of the Old Lithuani-

ans had been miners and sojourners, the 20,000 displaced

persons accepted by Canada—one-third of the Lithuanian

total—were largely educated officials and professionals who

feared the return of the Soviet army. Because Canada was

seeking miners, laborers, servants, and farmhands, many

Lithuanians hid their true professions, did manual labor for

their contracted year of work, then moved to Montreal,

Toronto, Vancouver, or other Canadian cities. Many even-

tually migrated to the United States. With the return of

Lithuanian independence in 1990, immigration to Canada

revived, though it remained small. Of 6,830 Lithuanian

immigrants in Canada in 2001, 4,915 came before 1961,

and only 900 between 1991 and 2001.

See also R

USSIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

OVIET IMMIGRA

-

TION

.

Further Reading

Alilunas, Leo J. Lithuanians in the United States: Selected Studies. San

Francisco: R. and E. Research Associates, 1978.

Budreckis, Algirdas. The Lithuanians in America, 1651–1975: A

Chr

onology and Factbook. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publica-

tions, 1975.

Danys, Milda. DP: Lithuanian Immigration to Canada after the Second

W

orld War. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario,

1986.

Fainhauz, D

avid. Lithuanians in the U.S.A.: Aspects of E

thnic Identity.

Chicago: Lithuanian Library Press, 1991.

Gaida, P

ranas. Lithuanians in Canada. Toronto: Lights Printing and

Publishing, 1967.

G

r

een, Victor. For God and Country: The Rise of Polish and Lithua-

nian Ethnic Consciousness in A

merica. Madison: State Historical

Society of W

isconsin, 1975.

Kucas, Antanas. Lithuanians in America. San Francisco: R. and E.

R

esear

ch Associates, 1975.

Wolkovich-Valkavicus, William. Lithuanian R

eligious L

ife in America:

A Compendium of 150 Roman Catholic Parishes and Institutions.

West Bridgewater, Mass.: Lithuanian Religious Life in America,

Corporate F

ulfillment S

ystems, 1991.

Van Reenan, A. Lithuanian Diaspora. Lanham, Md.: University Press

of America, 1990.

Lloydminster See B

ARR COLONY

.

Los Angeles, California

With a population of 16,373,645 at the turn of the 21st

century, the Los Angeles metropolitan area was second only

to the New York metropolitan area in size. It was the pri-

mary destination in the United States for the increasingly

large immigration of Latin Americans and Asians that devel-

oped under provisions of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATION

-

ALITY

A

CT

of 1965. Of metropolitan areas with populations

over 5 million in 2000, it had the highest percentage of for-

eign-born inhabitants at 29.6 percent.

By the time the United States acquired California fol-

lowing the U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

(1846–48), Nuestra

Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciuncula had been a

Mexican city for almost 30 years and a Spanish town for

almost a half-century before that. Apart from the native

Mexican population that stayed on, Los Angeles histori-

cally contained relatively few foreign-born citizens.

Between 1850 and 1920, the percentage of Mexican Amer-

icans living in Los Angeles declined dramatically, from a

vast majority to less than 20 percent. As the city’s general

population boomed between 1920 and 1970 (576,673 to

2.8 million), the foreign-born population remained rela-

tively constant, around 20 percent. Unlike most eastern

urban areas, population growth in Los Angeles was princi-

pally the result of internal migration, rather than foreign

immigration. Most migrants were midwestern Protestant

Anglos, who eventually dominated Los Angeles politics

and economic development, and most identified them-

selves by previous state of residence rather than ethnic

background. Depression-era Anglo refugees from the dust

bowl (principally the lower Great Plains) were prepared to

fill menial jobs, thus limiting the need for immigrant

labor. By 1970, the foreign-born population dipped to 15

percent. That downward trend was rapidly reversed after

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 179

implementation of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality

Act, which abolished national quotas and favored family

unification in selecting immigrants.

As a result of the new legislation, Los Angeles became

the center of migration for many Latino (see H

ISPANIC AND

RELATED TERMS

) and Asian immigrant groups. As Los

Angeles–area industry and agriculture grew, employers lob-

bied for increased immigration, particularly from Mexico.

Wartime demands for labor during World War I (1914–18)

led Congress to exempt Mexicans as temporary workers

from otherwise restrictive immigrant legislation. As a result,

almost 80,000 were admitted between creation of a “tem-

porary” farmworker program in 1917 and its termination

in 1922. Fewer than half of the workers returned to Mex-

ico, and many of them stayed in southern California. Link-

ing with networks that organized and transported Mexican

laborers, workers continued to enter the United States

throughout the 1920s, with 459,000 officially recorded.

Although there were no official limits on immigration from

the Western Hemisphere, many Mexicans chose to bypass

the official process that, since 1917, had included a literacy

test, making the actual number of Mexican immigrants

much higher. Most worked in agriculture in either Texas or

California. The B

RACERO

P

ROGRAM

brought an additional

5 million Mexican laborers between 1942 and 1964. During

the 1960s and 1970s, Mexican Americans made significant

gains in both political representation and economic condi-

tions; meanwhile, Los Angeles became more segregated as

non-Hispanic whites fled to the suburbs. The foreign-born

Los Angeles population from Mexico rose sixfold between

1970 and 1990 (283,900 to 1.7 million). By 2000, more

than 5 million Mexican Americans lived in Los Angeles,

making them the largest immigrant group by far. Migration

from El Salvador (see S

ALVADORAN IMMIGRATION

) and

Guatemala (see G

UATEMALAN IMMIGRATION

) rose at even

more dramatic rates: The Salvadoran population rose from

4,800 in 1970 to 231,605 in 2000, and the Guatemalan,

from 3,500 to 133,136. By 2000, Latinos composed more

than 40 percent of the population of the Los Angeles

metropolitan area.

Asians were among the first immigrants to Los Ange-

les. By 1890, there were more than 4,000 Chinese living

there (see C

HINESE IMMIGRATION

). After the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882), the largely bachelor population

declined, but the Chinese population grew rapidly after

1970. In 1970, there were about 56,000 Chinese in Los

Angeles; in 2000, they numbered 472,637. Throughout

most of the period between 1900 and 1970, the Japanese

were the largest Asian group in Los Angeles (see J

APANESE

IMMIGRATION

). With their own economy very strong after

1970, however, they did not come in large numbers during

the late 20th century. As a result, the Japanese population

grew more slowly, from about 120,000 in 1970 to 203,170

in 2000, when they were the fifth-largest Asian group,

behind the Chinese, Filipinos (438,013), Koreans

(273,191), and Vietnamese (252,278). The Asians have

been called the “model minorities” because of their high

levels of education, work ethic, and general social and eco-

nomic success. While the Chinese, Filipinos (see F

ILIPINO

IMMIGRATION

), and Japanese tended to be highly assimi-

lated and spread throughout the city in most areas of work,

Koreans are especially known for starting small businesses,

with whole families often working together (see K

OREAN

IMMIGRATION

). The Vietnamese were somewhat less suc-

cessful, mainly because they were more recent arrivals,

almost all coming after 1975, and, as refugees, were able to

survive in less skilled areas of work with significant support

from the government (see V

IETNAMESE IMMIGRATION

). In

2000, more than 10 percent of the Los Angeles metropoli-

tan population was Asian.

Given its diverse ethnic background, it is not surpris-

ing that Los Angeles suffered a number of prominent eth-

nic clashes, including the Chinese Massacre of 1871, which

saw 20 Chinese murdered by a white mob; the Zoot Suit

riots of 1943, in which young Chicanos were attacked by

Anglo mobs; and the Los Angeles riot of 1992 in which

Korean businesses, among others, were targeted following

the controversial acquittal of four white police officers in the

beating of Rodney King, an African American. Growing

concern about the cost of providing assistance to illegal

immigrants and fear of an increased flow from Mexico as a

result of the economic crisis led Californians to approve (59

percent to 41 percent) Proposition 187, which denied edu-

cation, welfare benefits, and nonemergency health care to

illegal immigrants. Decisions by federal judges in both 1995

and 1998, however, upheld previous decisions regarding

the unconstitutionality of the proposition’s provisions. The

anti-immigrant mood in Los Angeles remained strong, how-

ever, into the first decade of the 21st century. This was

reflected in the massive campaign to recall California gover-

nor Gray Davis in 2003. Based in part on opposition to

Davis’s support for providing illegal aliens with driver’s

licences, Los Angeles immigrant and Hollywood movie star

Arnold Schwarzenegger won a convincing victory in the

recall election in October.

Further Reading

Acuña, Rodolfo F. Anything but M

exican: Chicanos in Contemporary

Los Angeles. London: Verso, 1996.

Bergesen, Alber

t, and Max Herman. “Immigration, Race and Riot:

The 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.” American Sociological Review

63 (1998): 39–54.

Bonacich, E

dna, and Richard R. Appelbaum. Behind the Label:

Inequality in the Los Angeles A

pparel Industry. Berkeley: University

of California P

ress, 2000.

Bonacich, Edna, and Ivan Hubert Light. Immigrant Entrepreneurs:

Kor

eans in Los A

ngeles, 1965–1982. Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia P

ress, 1988.

180 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

Bozorgmehr, Mehdi, George Sabagh, and Ivan Light. “Los Angeles:

Explosive Diversity.” In Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race,

and Ethnicity in A

merica. Eds. Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rum-

baut. Belmont, Calif

.: Wadsworth, 1996.

Davis, Mike. Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disas-

ter

. N

ew York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Delgado, Hector

. New Immigrants, Old Unions: Organizing Undocu-

mented

Workers in Los Angeles. Philadelphia: Temple University

Pr

ess, 1994.

Fogelson, Robert. The F

ragmented Metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850–1930.

Cambridge, M

ass.: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Griswold del Castillo, Richar

d. The Los Angeles Barrio, 1850–1890: A

Social Histor

y. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Kelley

, Ron, Jonathan Frielander, and Anita Colby, eds. Irangeles.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

M

ilkman, R

uth, and Kent Wong. Voices from the Front Lines: Orga-

nizing Immigr

ant Workers in Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Center for

Labor Resear

ch and Education, University of California–Los

Angeles, 2000.

Min, Pyong Gap. Caught in the M

iddle: K

orean Communities in New York

and Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Modell, J

ohn. The Economics and Politics of Racial Accommodation: The

Japanese of Los Angeles, 1900–1942. Urbana: University of Illinois

P

ress, 1977.

Moore, Joan W. Going Down to the B

arrio: H

omeboys and Homegirls

in Change. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Ong, Paul, Edna Bonacich, Lucie Cheng, eds. The New Asian Immi-

gration in Los Angeles and G

lobal R

estructuring. Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1994.

Romo, Ricardo. East Los Angeles: History of a Barrio

. Austin: University

of Texas Press, 1983.

Sanchez, George J. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture,

and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945. New York:

Oxfor

d University Press, 1993.

Waldinger, Roger, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr, eds. Ethnic Los Angeles.

New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1996.

Louisiana

The watershed and mouth of the Missouri-Mississippi River

system became known as Louisiana and was from the earli-

est days of discovery considered strategically important by

many European nations. As a result, it had an unusually

wide array of ethnic influences during the 17th and 18th

centuries. The acquisition of Louisiana by the United States

in 1803 ensured control of the continental interior and pro-

vided ample land for migrant and immigrant farmers of the

new republic.

The first European to explore the region was the Span-

ish explorer Hernando de Soto (1541–42). Finding no min-

eral wealth, the Spanish paid little attention to the region. In

1682, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle claimed the Missis-

sippi River Valley for France, naming it Louisiana in honor

of King Louis XIV. Attempts by Scottish investor John Law

to colonize the region failed between 1717 and 1720, with

the exception of N

EW

O

RLEANS

, founded in 1718. Disap-

pointed with the little income generated from the region,

France ceded Louisiana to Spain from 1762 to 1800, though

it was done secretly and Spain did not gain firm control until

1769. During the 1790s, the sugar industry was established,

and the colony began to flourish. In addition to Spanish set-

tlers, an increasing number of Europeans from other countries

began to settle in the region. About 4,000 French colonists

from A

CADIA

migrated to Louisiana following the capitula-

tion of Montreal in 1760; the descendants of these migrants

became known as Cajuns. During the American Revolution

(1775–83), a significant number of Americans also came to

New Orleans, which had been granted to the Continental

Congress as a base of operations during the conflict.

In 1800, Napoleon coerced Spain into ceding Louisiana

back to France, though a full transfer of control was never

effected. In December 1803, in a transaction known as the

Louisiana Purchase, France sold the entire Mississippi val-

ley to the United States for about $15 million. The huge

region was subdivided during the 19th century, with the

present-day state of Louisiana being admitted to the Union

in 1812. With the advent of the steamboat, a great period of

commercial expansion began after 1812, and thousands of

settlers arrived between the end of the War of 1812 (1815)

and the beginning of the Civil War (1860). The northern

territories of Louisiana eventually became all or part of the

states of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, North

Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma,

Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana

and home to thousands of European immigrants seeking

land following the Civil War, which ended in 1865.

Further Reading

Brasseaux, Carl A. Acadian to Cajun:

Transformation of a People,

1803–1877. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992.

———. The “Foreign French”: Nineteenth-Century French Immigration

into Louisiana. 3 vols. Lafayette: University of Southwestern

Louisiana, 1990–93.

———. The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life

in Louisiana, 1765–1803. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univer-

sity Press, 1987.

———, ed. A Refuge for All Ages: Immigration in Louisiana History.

Lafayette: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1996.

Brasseaux, Carl A., and Glenn R. Conrad, eds. The Road to Louisiana:

The Saint D

omingue Refugees, 1792–1809. Lafayette: University

of Southw

estern Louisiana, 1992.

Kukla, John. A Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase. New

York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

Stolarik, M. Mark, ed. Forgotten Doors: The Other Ports of Entry to the

United S

tates. Philadelphia: Balch Institute Press, 1988.

Lower Canada See C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION

SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

;Q

UEBEC

.

LOWER CANADA 181

Macdonald, Sir John Alexander (1815–1891)

politician

John Alexander Macdonald was one of Canada’s dominant

political figures during the 19th century. Throughout the

long period of his leadership, he presided over a relatively

open immigration policy that targeted agriculturalists from

Britain, the United States, and northern Europe (see

C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

).

Macdonald, born in Glasgow, Scotland, believed that

the immigrant Scot was, “as a rule, of the very best class.”

His merchant family immigrated to the Kingston area of

Canada in 1820, and by 1830, Macdonald had been

apprenticed to a well-connected lawyer. He first took pub-

lic office in 1844 as the Conservative member for Kingston

in the Assembly of the Province of Canada. Extremely able,

he rose quickly in the Canada West wing of the party and by

1851 was its effective leader. As the dominant Conservative

leader during the next 40 years, Macdonald championed

confederation under a British model and always remained

wary of U.S. influence and threats. He became the first

prime minister of the Dominion of Canada, a position he

held almost continuously until his death (1867–73,

1878–91), interrupted only by his resignation over the

Pacific Scandal involving improper campaign contributions

from a railway syndicate.

Owing to the British North America Act (Constitution

Act, 1867), which provided for concurrent federal and

provincial powers regarding immigration, a national policy

emerged only gradually; the minister of agriculture assumed

full control of immigration in 1874. Although the Mac-

donald government in the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1869

adopted a laissez-faire approach that did not discriminate in

the selection of immigrants, Macdonald supported a num-

ber of measures that eventually prohibited members of the

“vicious classes” (criminal) (1872) and the “destitute”

(1879) and severely restricted entry of the Chinese (1885).

After 1878, Macdonald’s chief priorities were western set-

tlement and the building of a transcontinental railroad. As

a result, he took the position of minister of the interior as

well as of prime minister. Treaties with the western Indian

tribes during the 1870s ended their land claims, while the

D

OMINION

L

ANDS

A

CT

(1872) introduced an extensive

survey of western lands and provision of virtually free

homesteads on the prairies. In 1880, he negotiated an

agreement with a railway syndicate that led to the building

of the Canadian Pacific Railway, completed in 1885. The

railway laid a foundation for future growth, opening the

western prairies to settlement and linking British Columbia

to the East. Actual settlement during the Macdonald years

was not rapid, however, as international depression, stiff

competition from the U.S. West, and land speculation kept

immigrant numbers low. More than 1 million Canadians,

many of them immigrants, resettled in the United States

during Macdonald’s final ministries, and at his death in

1891, the entire population of the prairies stood at about

250,000.

182

M

4

Further Reading

Creighton, Donald. John A. Macdonald. 2 vols. Toronto: Macmillan

1952–56.

M

acdonald, J

ohn A. Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald. Ed. Joseph

Pope. Tor

onto: Oxford University Press, 1920.

———. Memoirs of the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdon-

ald. Ed. J

oseph Pope. Ottawa: J. Purie, 1894.

Swainson, Donald. Macdonald of Kingston: First Prime Minister.

Toronto: T. Nelson and Sons, 1979.

———. Sir J

ohn A. Macdonald: The Man and the Politician. Kingston,

Canada: Quarry Press, 1989.

Macedonian immigration

According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian

census of 2001, 38,051 Americans and 31,265 Canadians

claimed Macedonian descent. Detroit has the largest Mace-

donian community in the United States, with significant

concentrations in the Chicago area and throughout Ohio.

Canadian Macedonians have always been highly concen-

trated in the Toronto metropolitan area. About 95 percent

live in Ontario.

Macedonia occupies 25,100 square miles in east

Europe, on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It is bor-

dered by Bulgaria on the east, Greece on the south, Albania

on the west, and Serbia on the north. In 2002, the popula-

tion was estimated at 2,046,109. The people are principally

ethnic Macedonians (66 percent) and Albanians (23 per-

cent); about 67 percent are Eastern Orthodox, and 30 per-

cent, Muslim, roughly corresponding to ethnic divisions.

Macedonia enjoyed its greatest political success as the core of

a great empire under Alexander the Great during the fourth

century

B

.

C

. but thereafter was usually ruled as part of larger,

multiethnic political units. It was successively ruled by

Rome, Bulgaria, the Byzantine Empire, and the Ottoman

Empire. Following the unsuccessful Ilinden uprising of

1903, about 6,000 Macedonians made their way to Canada

and about 50,000 to the United States. Most were single

men from peasant backgrounds, working as laborers or in

transient jobs. Numbers are difficult to ascertain, as Mace-

donians were usually classified variously as Bulgarians,

Turks, Serbs, Albanians, or Greeks. Most of these Macedo-

nians were probably from the Bulgarian minority in the

region.

After more than 500 years under Muslim Ottoman rule

(1389–1912), Macedonia was wrested from Turkey but was

then divided among Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbs in the

Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. Serbia received the largest

part of the territory, with the rest going to Greece and Bul-

garia. In 1913, Macedonia was incorporated into Serbia,

which in 1918 became part of the Kingdom of the Serbs,

Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia). The restrictive

J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924 all but halted immigration

to the United States from Yugoslavia, and tens of thousands

returned to Europe. The Macedonian population in North

America continued to grow, however, as there was a strong

community in Toronto, and many Macedonians entered the

United States by way of Canada in order to avoid the quo-

tas. During the depression years of the 1930s, Macedonian

business organizations were formed in Toronto that led to

the establishment of bakeries, restaurants, dairies, hotels,

and other business enterprises.

Following World War II (1939–45), the Yugoslav Fed-

eration was reconstituted as a communist state but one

which recognized a certain degree of Macedonian auton-

omy. Thousands of Macedonians were displaced by the war,

with about 6,000 immigrating to Canada in the late 1940s.

There was little movement after the 1940s, however, as

Yugoslavia strictly controlled emigration; only about 2,000

Macedonians went to the United States between 1945 and

1960. Others came through Greece, where Macedonians

formed a small minority. The Yugoslav government liberal-

ized immigration policies in the 1960s, leading as many as

40,000 Macedonians to emigrate, many to Canada and the

MACEDONIAN IMMIGRATION 183

John A. Macdonald, first Canadian prime minister, 1867–73.

Macdonald generally adopted a laissez-faire attitude toward

immigration, though he found Scottish immigrants to be of

“the very best class” and the Chinese to be valuable for their

labor, “the same as a threshing machine or any other

agricultural implement which we may borrow from the United

States or hire and return to its owner.”

(Library of Congress,

Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-122757])