Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

measures providing for the economic and social welfare of

immigrants. In California, where one-third of all foreign-

born Americans lived, voters ignored previous U.S. Supreme

Court decisions protecting immigrants’ rights as a group to

pass P

ROPOSITION

187, denying education, welfare benefits,

and nonemergency health care to illegal immigrants. Federal

judges killed enactment of its provisions, but there continued

to be a strong national movement to impose tighter restric-

tions on immigration and to enforce immigration laws more

vigorously. In 1993, President Bill Clinton surprised sup-

porters by continuing outgoing president George H.W.

Bush’s policy of forcibly returning Haitian refugees inter-

cepted on the high seas, approved expedited hearings for

asylum seekers, and sought an additional $172.5 million for

the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) to

fight illegal immigration. This led to a series of decisions

speeding the deportation process, reducing automatic admis-

sion of certain immigrant groups, and limiting the importa-

tion of foreign workers. In 1996, a presidential election year,

a bill was enacted providing $12 million for construction of

a 14-mile fence south of San Diego, California, a substantial

increase in the number of Border Patrol and INS agents, and

a mandatory three-year prison sentence for smuggling illegal

aliens. The W

ELFARE

R

EFORM

A

CT

(1996) also stopped wel-

fare benefits to hundreds of thousands of legal immigrants.

One of the few exceptions to the trend toward tighter restric-

tions was a decision by the INS in 1995 to grant asylum to

women fleeing their homelands in fear of rape or beatings,

prompted by state-sponsored terror against Bosnian women

by Serb troops. While the challenges afforded by 13 million

new immigrants between 1990 and 2002 led some to ques-

tion the wisdom of continuing to accept new residents at

such a rate, the debate was largely a reprise of the issues raised

in the 1850s and the 1910s in the midst of two other great

waves of immigration.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the presidency of

George W. Bush saw two major initiatives with large impli-

cations for immigration policy. The first of these, designed to

gain greater control over the immigration process, was the

result of the terrorist attacks on New York City and Wash-

ington, D.C., on S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001. Almost immediately

the administration proposed a series of sweeping measures

designed to combat terrorism, including strengthened border

controls. The Uniting and Strengthening America by Pro-

viding Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct

Terrorism Act (better known as the USA PATRIOT A

CT

)

was quickly passed and signed into law by Bush on October

26, 2001. The act provided for greater surveillance of aliens

and increasing the power of the attorney general to identify,

arrest, and deport suspected terrorists. The resulting evalua-

tion of the nation’s security measures led to an extensive over-

haul of the immigration service. The Homeland Security

Act on November 25, 2002, abolished the INS, transferring

its functions to various agencies within the newly created

Department of Homeland Security. Immigration services

formerly provided by the INS were transferred to U.S. C

ITI

-

ZENSHIP AND

I

MMIGRATION

S

ERVICES

; enforcement over-

sight, to the Border Transportation Security Directorate;

border control, to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection;

and interior enforcement, to the U.S. Immigration and Cus-

toms Enforcement.

The second of these initiatives was Bush’s determination

to work in conjunction with Mexican president Vicente Fox

to regularize the participation of Mexican laborers in the U.S.

economy. Though negotiations were temporarily delayed in

the wake of September 11, on January 7, 2004, Bush pro-

posed the Temporary Worker Program, which would “match

willing foreign workers with willing American employers,

when no Americans can be found to fill the jobs.” More con-

troversially, it would provide temporary workers with legal sta-

tus, even if they were undocumented. Critics voiced concerns

that it did not provide a path to citizenship for those work-

ers. With regard to the desirability of widespread immigra-

tion, the first decade of the 21st century proved to be as

contentious as the last decade of the previous century.

Further Reading

Bailyn, Bernard. Voyages to the West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986.

Baseler

, Marilyn C. “Asylum for Mankind”: America, 1607–1800.

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Borjas, G

eorge. F

riends or Strangers: The Impact of Immigrants on the

U.S. Economy

. Reprint. New York: Basic Books, 1991.

Briggs,

Vernon M., Jr. Immigration Policy and the American Labor

For

ce. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

Daniels, R

oger. Coming to America. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

———. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and

I

mmigr

ants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Debouzy, M

arianne. In the Shadow of the Statue of Liberty: Immigrants,

W

orkers, and Citizens in the American Republic, 1880–1920.

Urbana: University of I

llinois P

ress, 1992.

Dimmitt, Marius A. The Enactment of the McCarran-Walter Act of

1952. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1971.

D

innerstein, Leonar

d, and David M. Reimers. Ethnic Americans: A

Histor

y of Immigration. 4th ed. New York: Columbia University

Pr

ess, 1999.

Dinnerstein, Leonard, Roger L. Nichols, and David M. Reimers.

Natives and Strangers: A Multicultural History of Americans. New

Y

or

k: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Divine, Robert. American Immigration Policy, 1924–1952. New

H

av

en, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1957.

Fischer, David. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New

Y

or

k: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Gimpel, James G., and James R. Edwards, Jr. The Congressional Poli-

tics of I

mmigr

ation Reform. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1999.

Grabbe, H

ans-Jurgen. “European Immigration to the United States in

the Early National Period, 1798–1820.” Proceedings of the Amer-

ican P

hilosophical Society 133, no

. 2 (1989): 190–214.

Hansen, M

arcus Lee. The Mingling of the Canadian and American Peo-

ples. Vol. 1, Historical. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press;

304 UNITED STATES—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

Toronto: Ryerson Press; London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford

University Press, 1940.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism,

1860–1925. Ne

w Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press,

1988.

Hutchinson, E. R. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: U

niv

ersity of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

Jasso, Guillermina, and Mark R. Rosenzwieg. The New Chosen People:

Immigr

ants in the U

nited States. New York: Russell Sage, 1990.

LeM

ay, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

Immigr

ation Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Loescher, G

il, and John A. Scanlan. Calculated Kindness: Refugees and

America

’s Half-Open Door, 1945–the Present. New York: Free

Pr

ess, 1986.

Portes, Alejandro, and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Immigrant America: A

P

or

trait. 2d ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Reimers, D

avid M. Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to

America. 2d ed. N

ew York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

———. Unw

elcome Strangers: American Identity and the Turn against

I

mmigration. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Saly

er, Lucy E. Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shap-

ing of Modern I

mmigration Law. Chapel Hill: Univ

ersity of North

Carolina Press, 1995.

Upper Canada See C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION

SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

.

USA PATRIOT Act (Uniting and

Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate

Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct

Terrorism Act) (United States) (2002)

I

n the wake of the S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the

administration of President George W. Bush proposed a

series of sweeping measures designed to combat terrorism,

including strengthened border controls. The USA

PATRIOT Act was quickly passed and signed into law by

the president on October 26, 2001.

The Patriot Act, as it became commonly known, pro-

vided for greater surveillance of aliens and for increasing the

power of the attorney general to identify, arrest, and deport

aliens. It also designated “domestic terrorism” to include “acts

dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal

laws of the United States or of any State that appear to be

intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; to

influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coer-

cion; or to affect the conduct of a government by mass

destruction, assassination, or kidnapping.” Also, monitoring

of some aliens entering on nonimmigrant visas was insti-

tuted, passport photographs were digitalized, more extensive

background checks of all applications and petitions to the

I

MMIGRATION

and N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) were

authorized, the SEVIS (Student and Exchange Visitor Infor-

mation System) database was created to track the location of

aliens in the country on student visas, and the U.S. office of

the Attorney General was given the right to immediately

expel anyone suspected of terrorist links. Also, the State

Department introduced a 20-day waiting period for visa

applications from men aged 16 to 45 from Afghanistan,

Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Indonesia, Iran,

Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Morocco,

Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria,

Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Any application

considered to be suspicious was forwarded to the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI), creating a further delay.

Though widely supported by the American public, the

Patriot Act remained a focal point of the evolving debate

about the nature of terrorism, the means necessary to com-

bat it, and the wisdom of sacrificing civil liberties for secu-

rity. Although the act specifically affirmed the “vital role” in

American life played by “Arab Americans, Muslim Ameri-

cans, and Americans from South Asia” and condemned any

stereotyping and all acts of violence against them, some

groups believed that the Patriot Act would enable the federal

government to target their activities and to suppress a vari-

ety of activist groups that disagreed with the government

on a wide array of issues. In January 2003, the Department

of Justice produced a draft bill, the Domestic Security

Enhancement Act, commonly dubbed Patriot II, which if

passed would further enhance the department’s powers to

deny information on possible terrorist detainees and create a

national terrorist database. The proposal of such further

measures alarmed groups including the American Civil Lib-

erties Union, heightening the debate in the United States

over the methods necessary for combating terrorism.

Further Reading

Ball, Howard. The USA PATRIOT Act: A Reference Handbook. New

Yor

k: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Chang, Nancy. Silencing Political Dissent: How Post–September 11

Anti-Terrorism M

easur

es Threaten Our Civil Liberties. New York:

S

even Stories Press, 2002.

Malkin, Michelle. Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists,

Criminals and Other F

or

eign Menaces to Our Shores. New York:

R

egnery, 2002.

Reams, Bernard D., Jr., and Christopher Anglim. USA PATRIOT

Act: A Legislative H

istor

y of the Uniting and Strengthening of

America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and

Obstruct Terrorism Act, Public Law no. 107-56. New York: Fred B.

Rothman, 2002.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

(USCIS)

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is the

agency within the D

EPARTMENT OF

H

OMELAND

S

ECURITY

(DHS) responsible for providing services to immigrants and

U.S. CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION SERVICES 305

nonimmigrant visitors, including immigration admission,

asylum and refugee processing, naturalization proceeding,

administration of special humanitarian programs, and

issuance of all immigration documents. The director of the

USCIS reports directly to the deputy secretary for homeland

security. The agency is served by about 15,000 employees

and contractors. With increased emphasis throughout the

U.S. government on security issues, early initiatives of the

USCIS included greater reliance on electronic biometrics,

with new technology systems enabling extensive storage of

fingerprints, photographs, and signature information. The

agency also introduced a business model of operation in

order to eliminate the backlog of approximately 3.7 million

cases pending at the end of fiscal year 2003.

On November 25, 2002, the Homeland Security Act

was signed by President George W. Bush, transferring func-

tions of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) to the newly created DHS. The functions of the INS

were then divided between the USCIS, focusing on immi-

gration services, and the Border and Transportation Security

Directorate, focusing on immigration enforcement. On

March 1, 2003, the INS was formally dissolved, and the

USCIS became operational.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Pol-

icy and Immigr

ants Since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Haynes,

Wendy. “Seeing Around Corners: Crafting the New Depart-

ment of Homeland Security.” Review of Policy Research 21, no. 3

(2004): 369–395.

U.S. I

mmigration and Citiz

enship Services Web site. Available online.

URL: http://uscis.gov/graphics/index.htm. Accessed July 5, 2004

U.S.-Mexican War (Mexican-American War)

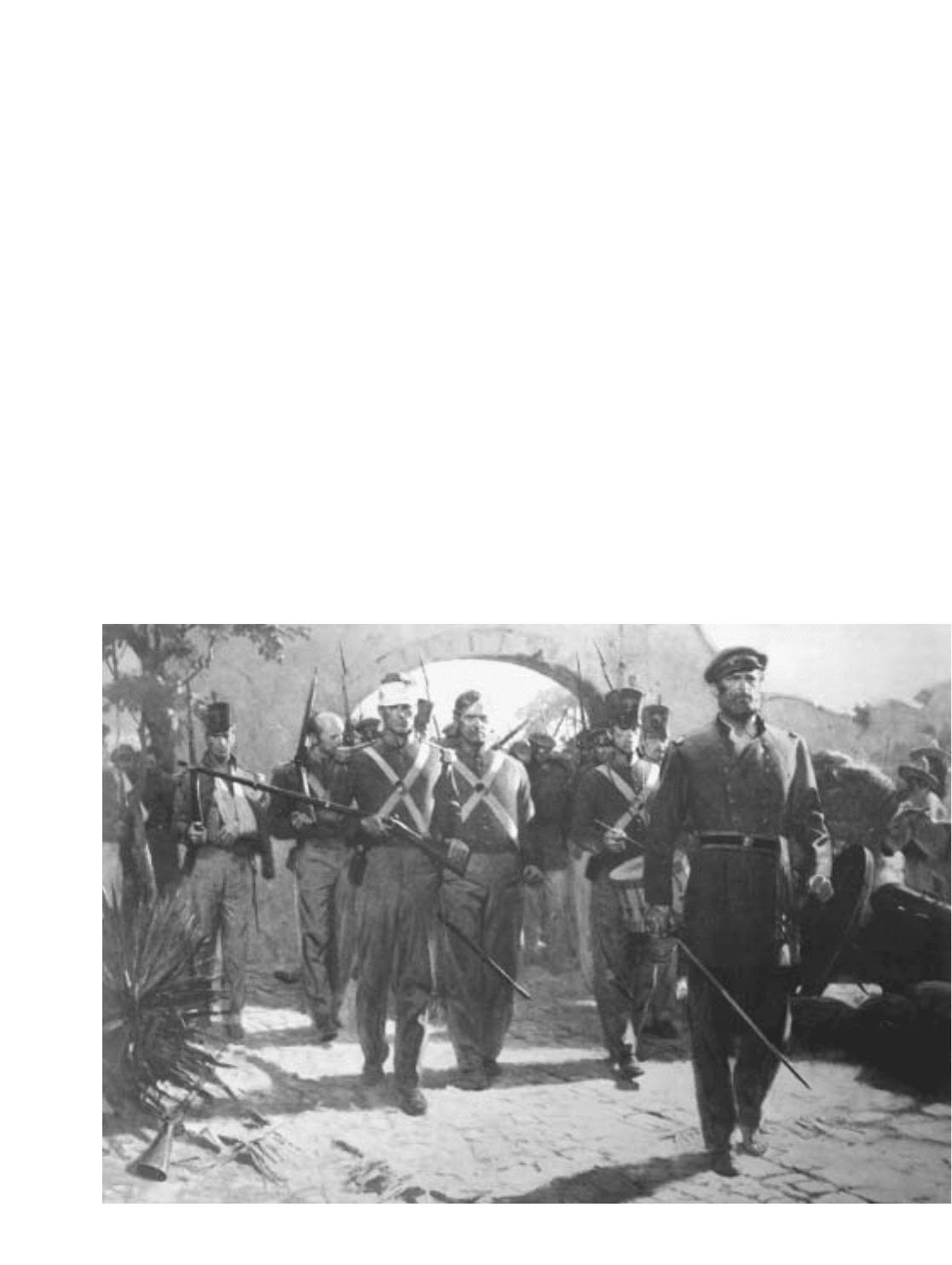

By defeating Mexico in the U.S.-Mexican War (1846–48),

the United S

tates added virtually all of the present American

Southwest to the Union, together with some 100,000 Mex-

ican citizens. This annexation assured a permanent and sub-

stantial non-European population in the expanding republic

and further added to the cultural diversity that marked the

development of the country.

306 U.S.-MEXICAN WAR

General Quitman (depicted at right) enters Mexico City with a battalion of marines, September 1847. (National Archives/DOD,War

& Conflict, #106)

The war began as a dispute over Texas (see T

EXAS

,

R

EPUBLIC OF

). In 1823, after Mexico had gained its inde-

pendence from Spain, it encouraged Americans to settle its

sparsely populated northern province of Texas, allowing

them to become Mexican citizens on condition of learning

Spanish and converting to Catholicism. Many came—

30,000 by the mid-1830s—but few took the conditions

seriously. In 1836, the Anglo-Mexicans successfully rebelled

and established the independent Republic of Texas. In 1845,

the U.S. government agreed to annex the young republic

but inherited a dispute over the Texas-Mexican border dat-

ing back to 1836. President James K. Polk attempted to pur-

chase northern Mexican lands to the Pacific Ocean,

including Texas but was rebuffed by Mexican authorities.

Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy territory as

far south as the Rio Grande, the southernmost extent of

Texan claims, which precipitated a Mexican attack in May

1846. The better-armed and more professional American

troops routed the Mexican army in northern Mexico, secur-

ing the region by February 1847. Polk also ordered a force

under General Stephen Kearney to move against the lightly

populated northwestern regions of New Mexico and Cali-

fornia, which were secured with little loss of life. In 1847,

General Winfield Scott landed an army at the Mexican port

Veracruz and won a decisive victory against General Anto-

nio López de Santa Anna at Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.

This opened the path to Mexico City, which was subdued

on September 13 with the storming of Chapultepec Castle

by U.S. troops under the command of Brigadier General

John Quitman.

By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 2,

1848), territory making up the modern states of California,

Nevada, and Utah, and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Col-

orado, and Wyoming was ceded to the United States in

return for $15 million. The Rio Grande was established as

the southern border between the two countries. The treaty

also provided that all Mexican citizens living in transferred

territory could continue residence and maintain full rights

of property. Within one year, they could elect to maintain

Mexican citizenship; otherwise, they would automatically

become U.S. citizens. Most of the inhabitants remained in

the region as American citizens. Although Mexican property

rights were nominally protected, a vast influx of settlers fol-

lowing the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH

undermined their

political power, while taxes and court costs led to the pro-

gressive selling off of land by Mexican Americans. By the

1880s, most of the large Mexican estates in the American

Southwest had fallen into the hands of American landown-

ers, and the economically diverse Mexican society that had

existed there was reduced to one of largely unskilled and

semi-skilled labor. New Mexico, with its majority Mexican

population until the 1940s, was a partial exception to this

trend. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853 completed reconcili-

ation of the border between the two countries.

Further Reading

Bauer, Karl Jack. The Mexican War, 1846–1848. New York: Macmil-

lan, 1974.

E

isenho

wer, John S. D. So Far from God: The U.S. War with Mexico

1846–1848. New York: Random House, 1989.

Griswold del Castillo, Richard. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A

Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Pr

ess, 1990.

U.S.-MEXICAN WAR 307

Vancouver Riot

The rising demand by industrialists for Asian labor during

the first decade of the 20th century led to a dramatic

increase in Japanese and Chinese immigration to British

Columbia and a growing fear by residents of what was

called a “yellow peril.” With immigration to the province

having risen from 500 in 1904 to more than 12,000 in

1908, racial tensions rapidly escalated. During 1907, with

the recession and resulting unemployment, Vancouver res-

idents were shocked to read of the decision of the Cana-

dian Nippon Supply Company to bring over Japanese

laborers for the building of the Grand Trunk Pacific Rail-

way. Erroneous reports suggested that as many as 50,000

might become part of the latest “invasion.” During a pub-

lic rally organized in September 1907 by the Asiatic Exclu-

sion League, angry and impassioned mobs marched

through the city, destroying Japanese and Chinese prop-

erty. This resulted in an immediate government investiga-

tion led by Deputy Minister of Labour W

ILLIAM

M

ACKENZIE

L

YON

K

ING

, who determined that the

Japanese government was not responsible for the circum-

stances leading to the riot, but rather Canadian immigra-

tion companies that sought laborers principally from

Hawaii, rather than from Japan itself. King awarded

Japanese and Chinese riot victims $9,000 and $26,000,

respectively, and made several recommendations, including

prohibition of contract labor and the banning of immi-

gration by way of Hawaii. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier

also sent Minister of Labour Rodolphe Lemieux to Japan

to negotiate an agreement regarding the limitation of

Japanese aliens. Despite provisions of the Anglo-Japanese

Treaty of Commerce and Navigation (1894), which pro-

vided for unfettered immigration, an agreement was

reached by which the Japanese government voluntarily

restricted the number of passports issued to its citizens

traveling directly to Canada to 400 per year. By 1908 and

1909, the number of Japanese entering the country

dropped from 7,601 to 495, remaining at the latter level

for the following 20 years.

Further Reading

Roy, Patricia E. A White M

an’s Province: British Columbia Politicians

and Japanese Immigrants, 1858–1914. Vancouver, Canada: Uni-

versity of B

ritish Columbia Press, 1989.

Sugimoto, H. H. “The Vancouver Riots of 1907: A Canadian

Episode.” In East across the Pacific. Eds. F. Hilary Conroy and T.

Scott Miyakawa. Santa Barbara, Calif.: CLIO, 1972.

Ward, W. Peter. White Canada Forever. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s

Univ

ersity P

ress, 1978.

Vietnamese immigration

There were virtually no Vietnamese in North America prior

to the Vietnam War (1964–75). Decades of war and crises

drove hundreds of thousands of them into exile, however,

creating one of the largest refugee communities in North

America. In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian cen-

sus of 2001, 1,223,736 Americans and 151,410 Canadians

4

308

V

claimed Vietnamese descent. Vietnamese refugees were

resettled widely throughout the United States; nevertheless,

there are large ethnic concentrations, particularly in the

greater Los Angeles area and in San Francisco, in Califor-

nia, and in Houston, Texas. In Canada, Toronto, Montreal,

and Vancouver all have large Vietnamese populations.

Vietnam occupies 125,500 square miles in Southeast

Asia on the east coast of the peninsula of Indochina. It is

bordered on the north by China and on the west by Laos

and Cambodia. In 2002, the population was estimated at

79,939,014. Ethnic Vietnamese compose 85–90 percent

of the population and Chinese about 3 percent, though

the latter figure was much higher prior to the Vietnam

War. There are also small numbers of Hmong, Tai, Meo,

Khmer, Man, and Cham peoples. The main religions are

Buddhism, Taoism, and Roman Catholicism. Nam Viet,

the first highly organized kingdom in Vietnam, emerged

around 200

B

.

C

. in the north. It was conquered by China

in the first century

B

.

C

., beginning a pattern of Chinese

influence in Vietnam, particularly during times of inter-

national strength. In the 10th century, Annam (northern

Vietnam) regained its independence, though not without

future invasions and interference from China. In 1471,

Annam conquered Champa to the south, a kingdom with

both Buddhist and Hindu influences. From the 11th

through the 17th centuries, there was a continual struggle

between the various peoples of modern Vietnam, Laos,

Cambodia, Burma, and Thailand for preeminence and the

definition of borders, punctuated by Chinese incursions

from the north. From the 17th century on, European

involvement grew. France captured Saigon in 1859 and

gradually gained control of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambo-

dia. A strong independence movement developed during

the 1920s. When Vietnam was returned to French con-

trol in 1945 following World War II (1939–45), guerrilla

warfare erupted, leading to French defeat and withdrawal

in 1954. At the Geneva Convention of that year, the

region was divided into three countries—Vietnam, Laos,

and Cambodia—with Vietnam temporarily divided until

elections could be held. Instead, South Vietnam declared

its independence, and the Communist Democratic

Republic of Vietnam was established in the north. The

activities of Communist infiltrators in the south—the Viet

Cong—led to U.S. intervention on behalf of an ineffective

South Vietnamese government in the early 1960s as part

of a

COLD WAR

policy to contain the spread of commu-

nism. By 1968, a half million American troops were

bogged down in a war of attrition, commanding the bat-

tlefields but unable to root out the guerrillas. After pro-

longed negotiations, a peace accord was reached in 1973,

and the United States withdrew in 1975, leading to a mas-

sive exodus on the part of those who had since the 1950s

aided the French or the Americans or who feared the

imposition of a communist government. Vietnam had

ongoing diplomatic and border conflicts with Cambodia

and China following the Vietnam War. By the 1990s, the

country’s government became more liberal, allowing

resumption of international travel and a gradual reintegra-

tion into the world economy. In 1995, Vietnam and the

United States reestablished formal diplomatic ties.

There were virtually no Vietnamese in North America

prior to the 1950s, though a few came escaping the turmoil

of the French departure and civil war. The first significant

migration came with the U.S. withdrawal in 1975, when

about 125,000 Vietnamese were brought to the United

States. These included most of the government and high-

ranking military figures, and their families. It is estimated

that among heads of household in this group, more than 30

percent were trained in professional or management areas,

though few were prepared for the sudden transition. Six

camps were established across the United States to help pro-

cess and resettle the refugees. After medical examinations and

interviews, each was assigned to one of nine voluntary agen-

cies (VOLAGs) that assumed responsibility for locating

sponsors who would support families for up to two years. Ini-

tially, Vietnamese families were placed throughout the

United States in an attempt to distribute the financial burden

across the states. The most successful resettlements, how-

ever, proved to be in southern California, where an estab-

lished Asian culture base already existed, including some

Southeast Asians. Gradually, the refugees migrated toward

the west, creating large Vietnamese enclaves in Orange

VIETNAMESE IMMIGRATION 309

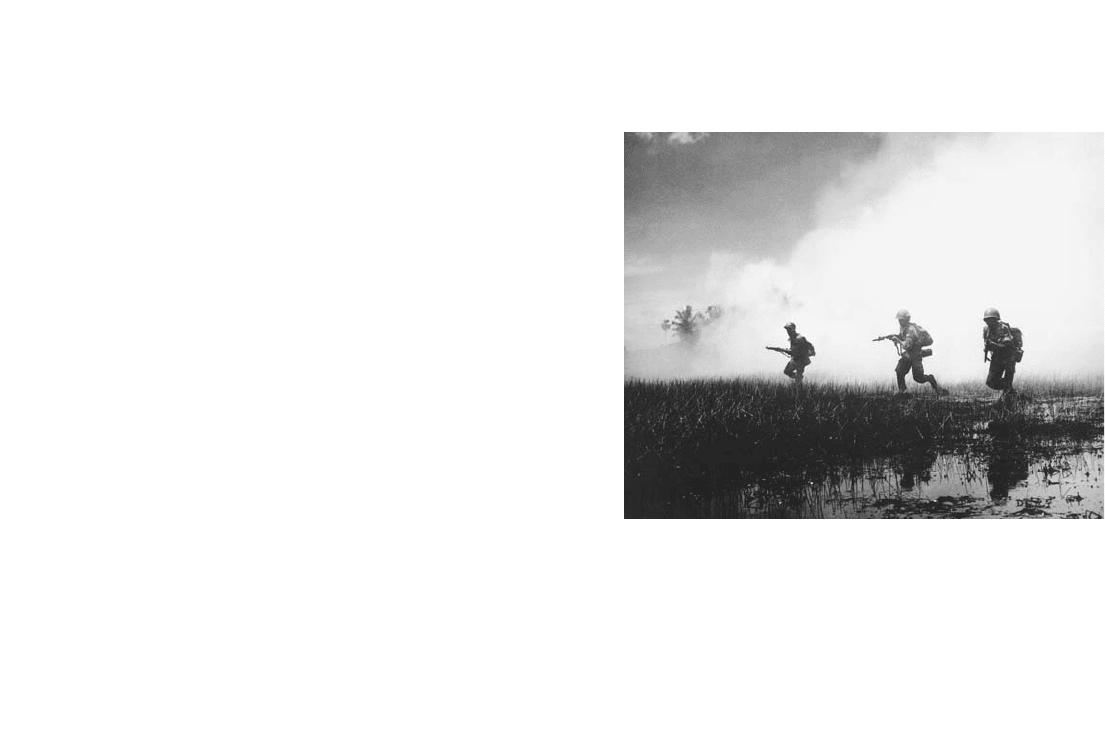

Vietnamese troops in action, 1961: The protracted conflict

and eventual U.S. withdrawal in 1975 left hundreds of

thousands of South Vietnamese collaborators at the mercy of

the new Communist government. Between 1975 and 1977,

approximately 175,000 Vietnamese refugees settled in the

United States.

(National Archives/DOD,War & Conflict, #403)

County and Los Angeles County, California. By 1976, more

than 20 percent of the refugees lived in California.

The second major wave of immigration came between

1975 and the early 1980s, when those who had not been

evacuated with the help of the U.S. government took to the

seas in every conceivable kind of craft, many profoundly

unseaworthy. They became the “boat people.” Two-thirds

were attacked at sea, usually more than once, and the refugees

robbed and often raped, before finally landing in Thailand,

Indonesia, or Malaysia. At first, the number of fleeing

refugees was small but picked up dramatically in 1979 when

Vietnam went to war with both Cambodia and China. The

Chinese ethnic minorities of Vietnam, about 7 percent of the

population, were especially vulnerable. Of almost 250,000

boat people who arrived in the United States, about 40 per-

cent were ethnic Chinese. Vietnamese immigration peaked

in 1980 (95,200) and 1981 (86,100). Unlike the first wave,

which contained many of Vietnam’s best-educated people,

the boat people were among the poorest and least educated of

any peoples to arrive in the United States after World War II

(1939–45). They were assigned to VOLAGs, but in advance

of their arrival, rather than afterward. The process of con-

centration, clearly established by 1976, continued. By 1984,

more than 40 percent of Vietnamese refugees lived in Cali-

fornia, and by 1990, about half lived there. About 11 percent

lived in Texas.

In 1979, the United Nations helped establish the

Orderly Departure Program (ODP), which enabled many

future Vietnamese immigrants to leave Vietnam legally. The

program required potential immigrants to get approval from

both the Vietnamese and U.S. governments and was

designed particularly to aid former South Vietnamese sol-

diers and the Amerasian children, about 8,000, produced as

a result of the long interaction of American troops with the

native population. Eventually, about 50,000 Vietnamese

came under the ODP before the program was discontinued

in 1987. By the mid-1980s, the Vietnamese population in

the United States was more than 650,000. Though the

economy gradually improved in Vietnam, immigration to

the United States remained strong, averaging about 40,000

per year between 1988 and 2002.

Roman Catholic religious students were the first Viet-

namese to come to Canada. Beginning in 1950, a handful of

students were given grants to study at Canadian universities.

Given Vietnam’s French colonial background, most pre-

ferred to attend universities in French-speaking Quebec.

When France cut diplomatic ties with the government in

Saigon in 1965, there was a new surge of interest in Cana-

dian universities, leading to the development of small Viet-

namese enclaves in Montreal, Quebec City, Sherbrooke,

Ottawa, Moncton, and Toronto. Many stayed on as profes-

sionals after their training.

By 1974, there were about 1,500 Vietnamese in

Canada, most living in Quebec. Canada played a major role

in the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees, admitting more

than 141,000 between 1975 and 1991. During the first

Vietnamese migration after the U.S. withdrawal in 1975,

Canada resettled about 5,600 refugees (1975–76). Between

1978 and 1981, about 50,000 boat people were admitted,

and about 80,000 more in a continuous migration between

1982 and 1991. Almost two-thirds of the first wave, who

tended to be well educated and often spoke French, settled

in Quebec. After 1978, however, the refugees were more

evenly distributed, with 40 percent going to Ontario, and

17 percent to Quebec. After 1991, the numbers declined

somewhat. Of the 148,405 Vietnamese immigrants living in

Canada in 2001, only 855 arrived before 1971 and about

41,000 between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Adleman, Howard. Canada and the Indochinese Refugees. Regina,

Canada: L. A. W

eigl Educational Associates, 1982.

Dorais, Louis-Jacques. The Cambodians, Laotians and Vietnamese in

C

anada. T

rans. Eileen Reardon. Ottawa: Canadian Historical

Association, 2000.

D

orais, Louis-J

acques, Lise Pilon Le, and Nguyên Huy. Exile in a Cold

Land: A Vietnamese Community in Canada. N

ew Haven, Conn.:

Y

ale Center for International and Area Studies, 1987.

Freeman, James A. Hearts of Sorrow: Vietnamese-American Lives. Stan-

for

d, Calif

.: Stanford University Press, 1989.

Haines, David W., ed. Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotions,

and Vietnamese in A

merica. Totowa, N.J.: Ro

wman and Little-

field, 1989.

Heine, Jeremy. From Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia: A Refugee Expe-

rience in the United States. New Yor

k: Simon and Schuster,

1995.

H

ung, Nguyên Manh, and David W. Haines. “Vietnamese.” In Case

S

tudies in Div

ersity: Refugees in America in the 1990s. Eds. David

W. H

aines. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1997.

Kelly, Gail Paradise. From Vietnam to America: A Chronicle of the Viet-

namese I

mmigr

ation to the United States. Boulder, Colo.: West-

view

, 1977.

Liu, William T., Maryanne Lamanna, and Alice Murata. Transition to

N

o

where: Vietnamese Refugees in America. Nashville, Tenn.: Char-

ter House, 1979.

Nguyên, D.

T

., and J. S. Bandare. “Emigration Pressure and Structural

Change: Vietnam.” Bangkok, Thailand: UNDP Technical Sup-

port Services Report, 1996.

O’Connor, Valerie. The Indochina Refugee Dilemma. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana S

tate U

niversity Press, 1990.

Rumbaut, Rubén G. “A Legacy of War: Refugees from Vietnam, Laos

and Cambodia.” In Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race and

E

thnicity in A

merica. Eds. Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut.

Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1996.

R

utledge, P

aul James. The Vietnamese Experience in America. Bloom-

ington: Indiana U

niversity Press, 1992.

Zhou, Min, and Carl Bankston. Growing Up American: The Adapta-

tion of Vietnamese Children to American Society

. N

ew York: Rus-

sell S

age Foundation, 1998.

310 VIETNAMESE IMMIGRATION

Virginia colony

Jamestown was the first permanent English settlement in the

Western Hemisphere (1607) and the core of what would

later become the royal colony of Virginia (1624). English

entrepreneurs had become interested in the Chesapeake

region in the 1570s but received little support from Queen

Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603). The failed attempts to estab-

lished R

OANOKE COLONY

(1584–87) forestalled English

efforts in the New World. By the early 17th century, an

intense rivalry with Spain and development of the joint-

stock company provided both the diplomatic motive and

the financial means for launching a successful enterprise. On

April 10, 1606, James I (r. 1603–25) granted the first Vir-

ginia charter, authorizing the London Company (soon

renamed the Virginia Company) to establish settlements in

the region of Chesapeake Bay. In December, the Susan Con-

stant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery landed 104 men and

bo

ys whose first concern was to locate a position that could

be secur

ed from attack. Although early reports observed

“faire meaddowes and goodly tall trees,” Jamestown had

many weaknesses as a site. Located on a marshy peninsula

more than 30 miles from the mouth of the James River, it

was disease-ridden, deficient in pure water, and located in

territory controlled by the powerful Powhatan confederacy.

Furthermore, the group consisted of many immigrants of

noble birth who were searching for easy wealth: In the first

year, disease, laziness, and greed nearly destroyed the colony,

with only about 40 men surviving into the new year. The

colony was saved only by an influx of immigrants and the

discipline imposed by Captain J

OHN

S

MITH

, who gained

control of the council in 1609.

A new royal charter in 1609 gave more power to the

Virginia Company, which again sought colonists and

investors, but military rule prevailed and conditions

remained desperate until John Rolfe successfully developed

a mild tobacco that appealed to Europeans. Between 1617

and 1622, settlers abandoned all other work in order to

profit from the new cash crop. Sir Edwin Sandys led stock-

holders in a series of reforms designed to make the colony

more attractive to speculators, including establishing Amer-

ica’s first representative assembly, the House of Burgesses

(1618) and the “headright” colonizing system for distribut-

ing land, which provided 50-acre plots for those paying their

own way to the New World and additional headrights if

they also paid for the passage of servants.

The lure of land and tobacco worked. Between 1619

and 1622, more than 3,000 people immigrated to Virginia.

Most were young, indentured Englishmen (see

INDEN

-

TURED SERVITUDE

), though there were significant numbers

of Scots-Irish and Irish and a few Germans who had been

recruited by the Virginia Company. Except for a few years of

prosperity linked to high tobacco prices, however,

Jamestown was a failure. By 1622, disease, contaminated

water, attacks by Native Americans, and emigration had

reduced the population to some 1,200, of whom only 270

were women or children, less than 8 percent of the total

number of 15,000 immigrants since 1607.

In 1624, James I transformed Virginia into a royal

colony, and life there gradually improved. By 1635, the pop-

ulation grew to 5,000. Although the Crown appointed a

governor and council, settlers insisted on maintaining the

House of Burgesses, which was officially recognized by

Charles I (r. 1625–49) in 1639. Life in Virginia remained

precarious, however, until the 1680s, with a population in

flux as a result of frequent deaths, immigration, acquired

freedom, and the gradual importation of slaves. Indentured

servants who had gained their freedom were usually forced

to the frontier and excluded from governance, grievances

that led to their support of Nathaniel Bacon’s rebellion in

1676. Concern over the growing number of Scots-Irish ser-

vants around 1698 led to restrictions, with only 20 allowed

at any river settlement.

SLAVERY

grew slowly in Virginia. The first Africans were

purchased in 1619, probably as indentured servants, but by

1650, there were only 300 Africans in a population of

15,000. While slavery was practiced, it was still possible for

slaves to gain freedom through manumission or conversion

to Christianity. As a result, a small group of free blacks

emerged in Virginia. Gradually, however, stipulations

regarding lifetime service became more common in sales and

court decisions. The system of perpetual slavery was

strengthened with the passage of slave codes, which legalized

the institution. The first codes were passed by the Virginia

General Assembly in March 1661, enacted to avoid confu-

sion over the status of children born of mixed-race relation-

ships. Turning traditional English law on its head, the

Assembly declared that the status of children should be

determined by “the condition of the mother,” thus ensuring

that almost all biracial children would remain slaves. In

1667, the assembly determined that “the conferring of bap-

tisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his

bondage or freedome.” A 1691 law made slaveholders

responsible for the costs of transporting manumitted slaves

out of the colony, thus reducing the tendency to manumit.

In 1705, the dozens of enactments regarding the rights and

protections of slaves were combined and strengthened into a

comprehensive slave code, forbidding Africans to bear arms,

own property, bear witness against whites, or travel without

permission. Punishment for specific crimes by maiming,

whipping, branding, and execution was sanctioned. The few

provisions that protected slaves were usually ignored, while

those protecting planters were rigidly enforced.

Virginia was by far the most populous colony at the

beginning of the 18th century. Tobacco cultivation dictated

the pattern of Virginian settlement. A handful of English

planters dominated politics and society from their widely

dispersed plantations, with slavery as the dominant labor

system. Of 80,000 Virginians in 1708, 12,000 were slaves.

VIRGINIA COLONY 311

According to one leading planter in 1705, Virginia still did

not have any place that might “reasonably bear the Name of

a Town.” Colonial governors were staunchly Anglican,

requiring presentation of credentials and expelling a number

of Puritan ministers. In the western backcountry, a small

number of Pennsylvania Germans settled alongside Scots-

Irish and English freedmen. From the 1680s, lower mortal-

ity rates began to produce a stable American-born ruling

class, and from this emerged the permanent patterns of

18th-century Virginian life. The College of William and

Mary was established in 1693, and six years later, the capi-

tal was transferred from Jamestown to Middle Plantation,

renamed Williamsburg.

Further Reading

Bailyn, Bernard. Voyages to the West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986.

Baseler

, Marilyn C. “Asylum for Mankind”: America, 1607–1800.

Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998.

B

illings,

Warren M., John E. Selby, and Thad W. Tate. Colonial Vir-

ginia: A Histor

y. White Plains, N.Y.: Kraus International, 1986.

Br

een, T. H. Puritans and Adventurers. New York: Oxford University

Pr

ess, 1980.

———. Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters

on the E

v

e of Revolution. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Pr

ess, 1985.

Carr, Lois, et al., eds. Colonial Chesapeake Society. Williamsburg, Va.:

N

or

th Carolina University Press, 1988.

Fischer, David. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New

Y

or

k: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, A

merican F

reedom: The Ordeal

of Colonial Virginia. New York: Norton, 1975.

Rutman, Darrett B., and Anita H. Rutman. A P

lace in Time: Middle-

sex County, Virginia, 1650–1750. New Yor

k: Norton, 1984.

T

ate, Thad W., and David L. Ammerman, eds. The Chesapeake in the

Seventeenth C

entury: Essays on Anglo-American Society. Chapel

Hill: U

niversity of North Carolina Press, 1979.

Voting Rights Act (United States) (1965)

The Voting Rights Act, passed b

y the U.S. Congress and

signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on August

6, 1965, suspended literacy tests and nationally prohibited

abridgment of the right to vote based on race or color. It also

authorized the Office of the Attorney General to examine

voting practices in areas where discrimination was suspected.

Plans to demonstrate compliance required preclearance from

the Justice Department. The act also found that poll taxes

were preventing African Americans from voting, leading to a

Supreme Court finding in 1966 that they were illegal.

Though the measure was aimed at reversing southern dis-

crimination against African Americans, it applied equally to

all immigrants who had become naturalized citizens. As

Nathan Glazer observed in Clamor at the Gates, the Civil

Rights A

ct of 1964 and the

Voting Rights Act of the follow-

ing year went hand in hand with the nonracial I

MMIGRA

-

TION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965 to represent a broadly

national consensus—at least outside the South—that equal-

ity should not have a racial component (see

RACISM

).

Prior to World War II (1941–45), there was practically

no registration of minority voters in the South. In 1940,

only 3 percent of otherwise eligible black voters were regis-

tered. The federal government had been ineffectual in its

haphazard attempts to undermine the disenfranchisement of

blacks that was routinely being practiced in the South

through the use of intimidation and various economic and

literacy tests, mainly because previous Supreme Court deci-

sions had limited congressional authority in enforcing

amendments passed during the Civil War (1861–65) but

also because of the strength of the southern voting bloc in

the Senate. By 1957, a modest civil rights measure was

passed, enabling the attorney general to seek injunctions

against violation of the Fifteenth Amendment guarantee

that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall

not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any

State on account of race, color, or previous condition of

servitude.” Beginning in the early 1960s, acts of violence,

including the murder of voting-rights activists in Philadel-

phia, Mississippi, gained national attention. The attack by

state troopers on peaceful protesters in Selma, Alabama, on

March 7, 1965, convinced President Johnson that special

legislation was necessary to overcome southern resistance to

the implementation of equal voting rights, despite the pro-

tections already offered in the Fifteenth Amendment.

According to Minnesota senator Walter Mondale, a Demo-

crat, the “outrage” in Selma made “passage of legislation to

guarantee southern Negroes the right to vote an absolute

imperative for Congress.”

Between 1965 and 1969, on several occasions the

Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the pre-

clearance requirement in Section 5, arguing that “case-by-

case litigation was inadequate to combat wide-spread and

persistent discrimination in voting, because of the inordi-

nate amount of time and energy required to overcome the

obstructionist tactics invariably encountered in these law-

suits.”

The Voting Rights Act was amended in 1970, 1975,

and 1982, further strengthening protection of voting rights.

By the end of the 1960s, registration of black voters in the

Deep South had increased to more than 60 percent, and an

increasing number of African Americans were being elected,

mainly at local and county levels.

Further Reading

Ball, Howard. “Voting Rights Act of 1965.” In The Oxford Compan-

ion to the Supr

eme Court of the United States. Ed. Kermit L. Hall.

New York: Oxford U

niversity Press, 1992.

Ball, Howard, Dale Krane, and Thomas P. Lauth. Compromised Com-

pliance: I

mplementation of the 1965

Voting Rights Act. Westport,

Conn.: Gr

eenwood Press, 1982.

312 VOTING RIGHTS ACT

Garrow, David J. Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Vot-

ing Rights Act of 1965. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press,

1978.

Kousser

,

J. Morgan. Colorblind Injustice: Minority Voting Rights and the

U

ndoing of the Second Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: University of

Nor

th Carolina Press, 1999.

Lawson, Stephen. Black B

allots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944–1969.

N

ew York: Columbia University Press, 1976.

U.S. Depar

tment of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Voting Section.

“Introduction to U.S. Voting Rights Laws.” Available online.

URL: http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/voting/intro/intro.htm. accessed

December 30, 2003.

VOTING RIGHTS ACT 313