Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

suppression of the Prague Revolt of 1968. Again, figures are

unreliable, both because immigrants from the Austrian

Empire were not differentiated before World War I, but also

because Slovaks emigrating from the United States were not

counted. Of the 10,450 Slovakian immigrants in Canada in

2001, about half came after the democratic revolution in

1989.

See also A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

;C

ZECH

IMMIGRATION

;G

YPSY IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Barton, Josef J. Peasants and Strangers: Italians, Rumanians, and Slovaks

in an American C

ity, 1890–1950. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

Univ

ersity Press, 1975.

Gellner, John, and John Smerek. The Czechs and Slovaks in Canada.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968.

J

acesova, Elena. “Slovak Emigrants in Canada as Reflected in Diplo-

matic Documents.” Slovakia 35 (1991–92): 7–35.

J

erabek, E.

Czechs and Slovaks in North America: A Bibliography. New

Yor

k: Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences in America,

1976.

Kirschbaum, S. J. A Histor

y of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. New

York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Kirschbaum, Joseph M. Slovaks in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Eth-

nic Pr

ess Association of O

ntario, 1967.

Stolarik, M. Mark. Growing Up on the South Side: Three Generations

of S

l

ovaks in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1880–1976. Lewisburg,

Pa.: B

ucknell University Press, 1985.

———. The Slovak Americans. New York: Chelsea House, 1988.

———. Immigration and Urbanization: The Slovak Experience,

1870–1918. New York: AMS Press, 1989.

———. Slovaks in Canada and the United States, 1870–1990: Simi-

larities and Differences. Ottawa: University of O

ttawa Press, 1992.

Slovenian immigration

Throughout most of its history, Slovenia was governed by

the Germanic Austrians or the Serb-dominated state of

Yugoslavia. In 1991, Slovenia won its independence, making

it one of the newest countries in the world. According to the

U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001,

176,691 Americans and 28,910 Canadians claimed Slove-

nian descent. Cleveland, Ohio, became the center for Slove-

nian settlement in the United States, with significant

concentrations throughout the industrial Midwest. More

than two-thirds of Slovenian Canadians live in Ontario.

Slovenia occupies 7,800 square miles in southeast

Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west; Austria and Hun-

gary to the north; and Croatia to the southeast. In 2002, the

population was estimated at 1,930,132. Always the most

ethnically homogenous region of Yugoslavia, 91 percent of

its population is Slovene and about 3 percent Croat. The

chief religion is Roman Catholicism. Originally from the

modern regions of Poland, Ukraine, and Russia, the

Slovenes settled in their current territory between the sixth

and eighth centuries. They began to fall under German

domination as early as the ninth century and for a thou-

sand years were generally under the rule of German princes.

Around 1848, Slovenes scattered among several Austrian

provinces began their struggle for political and national uni-

fication (see A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

;

REVO

-

LUTIONS OF

1848). In 1918, most Slovenes became part of

the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later renamed

Yugoslavia (see Y

UGOSLAV IMMIGRATION

). Slovenia

declared its independence on June 25, 1991, and joined the

United Nations on May 22, 1992. With few Serbs living

there, the Yugoslav army put up minimal resistance to Slove-

nian withdrawal from Yugoslavia, and Slovenia was largely

spared the war and violence that plagued Bosnia and Kosovo

throughout the 1990s. Linked by trade with the European

Union, Slovenia applied for full membership in 1996.

Most Slovenes immigrated to the United States as a part

of the

NEW IMMIGRATION

between 1880 and 1923, with a

smaller group coming after World War II (1939–45)

between 1949 and 1956. Numbers are unreliable, as

Slovenes were often grouped by immigration officials with

Croats or listed as Austrians, Yugoslavs, or Germans. A rea-

sonable total estimate for the two migrations is about

300,000. The earliest organized Slovene immigration to the

United States was composed of Roman Catholic priests who

in 1831 came as missionaries to the American Indian tribes

of Michigan, Minnesota, and the Dakota Territory; dozens

followed. Most arrivals before and just after World War I

(1914–18) were of poor peasant farmers escaping over-

crowded conditions. They usually came in small groups,

often as single men, who then later sent for their families. By

the 1880s, they were established in mining communities of

Michigan and Minnesota. In the 1890s, an increasing num-

ber were settling in Cleveland and Chicago. During the early

20th century, Cleveland became the largest Slovenian city

outside Slovenia, with a population of more than 30,000

Slovenians in 1920. With a relatively stable economy and

political system, there has not been great pressure for Slove-

nians to emigrate. Between 1992 and 2002, average annual

immigration to the United States was only about 70.

Significant Slovene immigration to Canada started in

the 1920s, following the United States’ restrictive E

MER

-

GENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

(1921) and J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924). Groups of young, healthy Slovenes were recruited

by travel agents as contract laborers under the Railway

Agreement of 1925. After working on farms or railroads in

Saskatchewan, Manitoba, or British Columbia, many

migrated to western mining towns. About 2,500 Slovenians

refugees were accepted between 1947 and 1951 and often

spent a year under contract before seeking city jobs. Some

6,000 Slovenians came between 1951 and 1970, mainly

joining family members who had arrived during the previ-

ous periods. Of the 9,250 Slovenian immigrants in Canada

274 SLOVENIAN IMMIGRATION

in 2001, half came before 1961. Only 545 came between

1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Genorio, Rado. Slovenci v Kanadi. Ljubljana, Slovenia: Institut za

geografio Univ

erze, 1989.

Gobetz, G. Edward. Adjustment and Assimilation of Slovenian Refugees.

New York: Arno Press, 1980.

Lenˇcek, R., ed. Papers in Slovene Studies. New York: Society for Slovene

Studies, 1975.

———. Twenty Years of Scholarship. New York: Society for Slovene

Studies, 1995.

Prisland, Marie. From Slovenia to America: Recollections and Collections.

Chicago: Slovenian Women’s Union of America, 1968.

Urbanc, Peter, and Eleanor Tourtel. Slovenians in Canada. Hamilton,

Canada: Slovenian Heritage Festival Committee, 1984.

Van Tassel, D. D., and J. J. Grabowski, eds. The Encyclopedia of Slovene

History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Smith, Al (Alfred Emmanuel Smith)

(1873–1944)

politician

Smith was the first U.S. politician to build a national repu-

tation by appealing to ethnic groups and was the first

Roman Catholic to run for president. Although soundly

defeated in the 1928 election, he helped turn immigrant

voters to the Democratic Party and helped to establish the

new Democratic consensus that was consolidated by Presi-

dent Franklin Roosevelt during the New Deal.

Smith, an ambitious Irish-American Catholic, was

raised on New York City’s Lower East Side. His parents were

both children of Irish immigrants. Smith began his political

career in the pay of the Tammany Hall political machine,

although the rampant corruption grated on his ethical sen-

sibilities. As a reward, he was picked to run for the New York

State Assembly in 1903, where he sat until he was selected

sheriff of New York City in 1915 and president of the Board

of Aldermen two years later. Having become especially

knowledgeable about industrial affairs, he gradually devel-

oped a progressive reform program that especially appealed

to immigrants. In 1918, he won the governorship of New

York in a surprising victory over the Republican incum-

bent. While in office, he oversaw a number of social reforms,

including enhanced workmen’s compensation provisions,

higher teachers’ salaries, and state care for the mentally ill.

Although defeated in the Republican landslide of 1920, he

came back to regain the governor’s chair in 1922. Smith

was defeated in the Democratic primary for president in

1924 in a divisive intraparty contest between the largely

rural, Protestant, and prohibitionist South and West and the

ethnically diverse and antiprohibitionist Northeast. He nev-

ertheless was reelected as governor of New York for third and

fourth terms in 1924 and 1926. The peak of his political

career came in 1928 when he was nominated as Democratic

presidential candidate on the first ballot. In an age of appar-

ent economic prosperity, Smith had little chance to defeat

Republican Herbert Hoover, but he did attract large num-

bers of foreign-born Americans to the polls, enabling

Democrats to carry most large urban areas for the first time.

Ironically, in later life Smith left the Democratic Party, dis-

daining the New Deal vision of a planned society.

Further Reading

Eldot, Paul. Governor Alfred E. Smith: The Politician as Reformer. New

York: G

arland, 1983.

Handlin, Oscar. Al Smith and His America. 1958. Reprint, Boston:

N

or

theastern University Press, 1987.

Josephson, Matthew, and Hannah Josephson. Al Smith: Hero of the

C

ities. Boston: H

oughton Mifflin, 1960.

Smith, Al. U

p to Now: An Autobiography. New York: Viking Press,

1929.

Smith, John (ca. 1580–1631) military leader, colonist

A veteran of many European military campaigns, Captain

John Smith is best known for his presidency of the govern-

ing council of Jamestown in V

IRGINIA COLONY

. His strong

leadership during the often-desperate early years of En-

gland’s first settlement in the Americas enabled the colony of

Jamestown to survive and ensured an English foothold on

the eastern seaboard of North America.

Smith was born in Lincolnshire, England, around 1580,

to the family of a yeoman farmer. Smith spent most of his

early life in travel and combat, fighting Spanish Catholics in

the Netherlands and Muslims in the Mediterranean and in

Hungary. Captured and enslaved by the Turks during a cam-

paign that began in 1600, he eventually escaped, returning to

England by way of Russia, Poland, the Holy Roman Empire,

Germany, France, Spain, and Morocco. As a soldier of for-

tune, he was naturally attracted to new ventures in the Amer-

icas, though almost nothing is known regarding the exact

circumstances of his initial involvement. In 1606, Smith was

appointed one of seven resident councillors of the newly

formed Jamestown Colony of the Virginia Company. Elected

president of the council in September 1608, at a time when

disease, American Indian attacks, and ill-discipline had deci-

mated the community, Smith set about to ensure that every-

one—including the well born—worked. As an experienced

soldier and traveler, Smith had a wide range of needed skills,

including mapping, exploration, and organization. He nego-

tiated favorable trade with the local native groups, ensuring

a more ready supply of food. His A True Relation of Such

Occurr

ences and A

ccidents of Noate as hath Hapned in Virginia

since the First Planting of that Collony (1608), written as a

long letter and published in E

ngland, is consider

ed America’s

first book. When he returned to England in October 1609 as

a result of a serious gunpowder burn, Virginia once again

fell into near anarchy.

SMITH, JOHN 275

Smith returned to North America once, in 1614, to

explore the coast of New England. He offered to assist in the

settlement of the Pilgrims in 1619 and to lead a military

force against the Indians of Virginia in 1622 but was

rejected. His most important contributions late in life were

historical works that reveal much about colonial life in the

earliest days of English settlement, notably A Description of

N

ew E

ngland: Or, Observations and Discoveries of Captain

John Smith (1616), New Englands Trials (1620), and The

G

ener

all Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer

Isles (1624). Arrogant and ambitious, Smith undoubtedly

exaggerated his r

ole in many ev

ents of which he wrote, but

historians have generally confirmed the accuracy of his

work.

Further Reading

Barbour, Philip L. The Three Worlds of Captain John Smith. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1964.

E

merson, Everett H. Captain J

ohn Smith. New York: Twayne, 1971.

S

mith, John. The Complete Works of Captain John Smith, 1580–1631.

3 vols. Ed. Philip L. Barbour

. Chapel H

ill: Institute of Early

American History and Culture, University of North Carolina

Press, 1986.

Vaughan, Alden T. American Genesis: Captain John S

mith and the

Founding of Virginia. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1997.

South Asian immigration

Most early studies of immigration to the United States and

Canada treated all the peoples of South Asia as a single cat-

egory, including immigrants from more than a dozen eth-

nic groups who inhabited British India prior to 1947.

Nevertheless, most pre–World War II South Asian immi-

grants were Sikhs from the Punjab, who created a relatively

uniform Indian presence in the farming valleys of Califor-

nia. Prior to 1965, there were never more than 7,000 South

Asians legally in the United States, and most of them were

deported or left the country during the late 1920s and

1930s. Because of the preponderance of Sikhs and the small

number of other South Asian immigrants prior to the

1970s, little attention was paid to distinctions, making it

now impossible to determine exactly how many South Asian

immigrants came from each of the modern states that

emerged with the ending of British rule in India in 1947,

including India, Pakistan, Ceylon (later Sri Lanka), and

Bangladesh. The term Hindu, which was the most common

designation until the 1960s, was both inaccurate and con-

fusing, as the majority of S

outh Asian immigrants w

ere not

religious Hindus but rather Sikhs and Muslims. Further

confusing immigrant figures is the considerable transmigra-

tion that occurred as a result of the export of South Asian

labor from British India during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Significant numbers of people who immigrated to the

United States from Uganda, Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania,

Guyana, Trinidad, Fiji, and Mauritius were either born in

India, Pakistan, or Sri Lanka or were the descendants of

South Asian natives. Prior to the 1980 census, South Asian

immigrants were still classified as “white/Caucasians.”

When the United States reopened South Asian immi-

gration in 1946, there were only about 1,500 South Asians

in the country. The turning point came with the I

MMIGRA

-

TION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, which led to a mas-

sive influx of South Asians. Meanwhile, in Canada, the

government had much earlier (January 1, 1951) imple-

mented a new quota system for South Asian immigrants,

effectively laying the foundation for a diverse and complex

South Asian population in the Americas. Under separate

quotas for India, Pakistan, and Ceylon, most early immi-

grants were Sikh relatives. By the late 1950s, however, an

increasing number were pioneer immigrants from a variety

of ethnic groups, gradually eroding the near-Sikh monopoly.

See also B

ANGLADESHI IMMIGRATION

;I

NDIAN IMMI

-

GRATION

;P

AKISTANI IMMIGRATION

;S

RI

L

ANKAN IMMI

-

GRATION

.

Further Reading

Buchignani, Norman, and Doreen M. Indra, with Ram S

rivastava.

Continuous Journey: A Social History of South Asians in Canada.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

La Brack, Bruce. “S

outh Asians.” I

n A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook

on America

’s Multicultural Heritage. Ed. Elliott Robert Barken.

Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Leonard, Karen I

saksen. The South A

sian Americans. Westport, Conn.:

Gr

eenwood Press, 1997.

South Carolina colony See C

AROLINA COLONIES

.

South Korea See K

OREAN IMMIGRATION

.

Soviet immigration

Emigration from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

(USSR; Soviet Union) was, for most of its history

(1917–91), forbidden. Those who did emigrate were often

dissidents and came from many, mostly non-Russian ethnic

groups, including Jews, Armenians, Estonians, Latvians,

Lithuanians, and Ukrainians. There was little or no sense of

Soviet identity; the history, social organization, and areas of

settlement varied from group to group. As a result of the dis-

solution of the Soviet Union in 1991, it is usually within the

context of the specific ethnic groups that immigration is

most meaningfully discussed.

The USSR was the largest state the modern world had

seen, occupying 8,649,500 square miles, or about 30 per-

cent more territory than modern Russia. It stretched from

eastern Europe across northern Asia to the Pacific Ocean. It

276 SOUTH ASIAN IMMIGRATION

was bordered on the west by Finland, Norway, Poland,

Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania and on the south

by Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, China, Mongolia, and North

Korea. At the time of its collapse, there were 15 major eth-

nic groups in the Soviet Union, forming the basis for the 15

states that emerged. There were many other smaller ethnic

groups, as well.

During the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, the trans-

formation of Russian state boundaries significantly affected

the character of R

USSIAN IMMIGRATION

. Ivan the Terrible

(r. 1533–84), the first czar, began the expansion of the state

to include significant numbers of non-Russian peoples.

Between 1667 and 1795, Russia expanded westward, con-

quering lands mainly from the kingdoms of Poland and

Sweden that included the peoples of modern Latvia, Lithua-

nia, Estonia, eastern Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. Russia

acquired most of the remainder of Poland and Moldova

(Bessarabia) in 1815, following the Napoleonic Wars.

Throughout the 19th century, Russia continued to expand,

especially into the Caucasus Mountain region and central

Asia, occupying regions that would later become the mod-

ern countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan,

Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Dur-

ing the great age of immigration from eastern Europe

between 1880 and 1920, therefore, more than a dozen

major ethnic groups might be classified by immigration

agents as “Russian,” though they were in fact part of these

older nations.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, which ushered in

the world’s first communist government, soon spread to

most of the surrounding territories acquired by Russia, lead-

ing to the establishment of the USSR in 1922. The USSR

consisted roughly of the old Russian Empire, except for the

loss of Finland, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland,

which became independent countries after World War I

(1914–18). During World War II (1939–45), the Soviet

Union reoccupied parts of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithua-

nia, Poland, and Moldova and afterward exercised extensive

control over the foreign and immigration policies of the

nominally independent countries of Poland, Czechoslo-

vakia, Hungary, East Germany, and Romania. Finally, in

1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. In its place were 15 sepa-

rate states, each having its own annual immigration quota to

the United States and Canada.

The Soviet government tightly controlled emigration.

Most who did emigrate were wartime refugees, who were

not allowed to return, or were Jews, who were sporadically

allowed to leave legally from 1970. Whereas an average of

about 125,000 immigrants came to the United States annu-

ally from the old Russian Empire between 1901 and 1920,

the figure dropped to only about 6,100 during the 1920s,

with most of these being anticommunist, White Russians

who fled in the immediate wake of the Russian Civil War,

prior to the formal establishment of the USSR (1922). The

Soviet government then banned virtually all emigration, and

those who did come to the United States and Canada were

often viewed with suspicion, in part because of their radical

ideas and labor union involvement: Between 1931 and

1970, only about 5,000 Soviets immigrated, many of them

dissidents and not all Russians. The United States accepted

about 20,000 Soviet refugees under provisions of the D

IS

-

PLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

of 1948 and related executive mea-

sures after World War II. About 40 percent of Canada’s

125,000 refugee immigrants between 1947 and 1953 were

Ukrainians (16 percent), Jews (10 percent), Lithuanians (6

percent), Latvians (6 percent), and Russians (3 percent),

most of whom came from Soviet lands.

As

COLD WAR

tensions eased during the 1970s, the

Soviet government gradually relaxed emigration restrictions,

which led to an annual average immigration to the United

States of about 4,800 between 1970 and 1990, mostly Jews

and Armenians. It is estimated that between 1970 and 1985,

about a quarter million Jews were allowed to emigrate, often

as a part of Western diplomatic efforts to secure better treat-

ment for them. Most went to Israel, but perhaps 100,000

settled in the United States. With the final collapse of the

Soviet Union in 1991, a massive exodus from the economi-

cally debilitated country ensued. Almost a half million Sovi-

ets or former Soviets immigrated to the United States during

the 1990s, probably about 15 percent of them ethnic Rus-

sians. The substantial immigration continued into the fol-

lowing decade, with about 55,000 coming in both 2001 and

2002. Of Canada’s 142,000 immigrants from the former

Soviet Union (2001), 53 percent came between 1991 and

2001.

See also A

RMENIAN IMMIGRATION

; E

STONIAN IMMI

-

GRATION

; J

EWISH IMMIGRATION

; L

ATVIAN IMMIGRATION

;

L

ITHUANIAN IMMIGRATION

; U

KRAINIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Gold, Stephen J. From the Workers’ State to the Golden State: Jews from

the For

mer Soviet Union in California. Boston: Allyn and Bacon,

1995.

G

oldman, M

inton. “United States Policy and Soviet Jewish Emigra-

tion from Nixon to Bush.” In Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and

the Soviet Union. Ed. Yaacov Ro’i. Portland, Ore: Frank Cass,

1995.

H

a

rdwick, Susan Wiley. Russian Refuge: Religion, Migration, and Set-

tlement on the No

rth American Pacific Rim. Chicago: University of

Chicago Pr

ess, 1993.

Jeletzky, F., ed. Russian Canadians: Their Past and Present. Ottawa:

Bor

ealis P

ress, 1983.

Kipel, Vitaut. Belarusy u ZshA. Minsk, 1993.

———. “B

elor

ussians in the United States.” Ethnic Forum 9, nos. 1–2

(1989): 75–90.

K

ur

opas, Myron B. The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations,

1884–1954. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Lupul, Manoly R. A Heritage in Transition: Essays in the History of

Ukr

ainians in Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

SOVIET IMMIGRATION 277

Magocsi, Paul R. The Carpatho-Rusyn Americans. New York: Chelsea

House, 1989.

———. Our People: Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Descendants in North

America. 3d r

ev. ed. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of

Ontario, 1994.

———. The Russian Americans. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Orleck, Annelise. The So

viet Jewish Americans. Westport, Conn.:

G

reenwood Press, 1999.

Ro’i, Yaacov. The Struggle for Soviet Jewish Emigration, 1948–1967.

Cambridge: Cambridge U

niv

ersity Press, 1991.

Simon, Rita J. New Lives: The Adjustment of Soviet Jewish Immigrants

in the United S

tates and Israel. Lexington, Ky.: Lexington Books,

1985.

Spanish immigration

Significant elements of Spanish culture represent one of the

major strands of the American social fabric. Although Span-

ish immigration has been modest since the foundation of

the United States, the descendants of the settlers of Spain’s

New World empire—including Mexicans, Puerto Ricans,

Cubans, Dominicans, Costa Ricans, Guatemalans, Hon-

durans, Nicaraguans, Panamanians, Salvadorans, Argen-

tineans, Bolivians, Chileans, Colombians, Ecuadoreans,

Paraguayans, Peruvians, Uruguayans, and Venezuelans, with

their own mestizo cultures that incorporate indigenous,

African, and Spanish cultural traits and customs—com-

posed 12.5 percent of the population of the United States in

2000, making it the largest single minority group in the

country. Latin Americans account for less than 1 percent of

Canada’s population. According to the U.S. census of 2000

and the Canadian census of 2001, 861,911 Americans and

213,105 Canadians claimed Spanish descent. Spanish

Americans are spread widely throughout the United States,

with the greatest concentrations being in New York City and

Tampa, as well as Florida generally, and the former Spanish

Empire lands in the American Southwest. Spanish Canadi-

ans were heavily concentrated in both Quebec and Ontario.

Spain occupies 192,600 square miles of the Iberian

Peninsula in southwest Europe. Also on the peninsula, Por-

tugal lies to the west and France to the north on the conti-

nental mainland. In 2002, the population was estimated at

40,037,995. The people are a mixture of Mediterranean and

Nordic types, and the chief religion is Roman Catholicism.

Spain was among the first European states to create a strong

national monarchy, late in the 15th century. As a result of

the voyages of C

HRISTOPHER

C

OLUMBUS

and other explor-

ers, from 1492 through the 16th century, Spain claimed the

entire Caribbean Basin, most of Central and South Amer-

ica (excluding Brazil), and the southwestern portion of the

modern United States, including all or parts of California,

Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. The first

permanent Spanish settlement in the United States was at St.

Augustine, Florida, in 1565, whereas the British, French,

and Dutch had begun to establish themselves in unsettled

territories in North America early in the 16th century. In the

New World, Spain created an efficient and highly bureau-

cractic colonial government, headed in Madrid. This

stemmed in part from Spanish feudal traditions and also

from the desire to control the wealthy gold and silver trade

coming out of Mexico and Peru. During 300 years, Spain

effectively imposed its culture on the indigenous societies

through force—war, death, disease, and forced labor—and

intermarriage. By the 18th century, the mestizo population

was larger than either the Spanish or Indian population,

though the percentages varied widely throughout the

empire. By the 19th century, almost all subjects of the Span-

ish Crown had been Christianized, though colonial Catholi-

cisms embraced numerous elements from native religions.

Although Spanish immigration to the New World was sub-

stantial, estimated at almost a half million between 1500

and 1700, most settled in Mexico, Cuba, and South Amer-

ica. Settlement in the northern borderlands that would later

become part of the United States was small. Between 1809

and 1825, Mexico and most of Central and South America

gained their independence from Spain. Texas won its inde-

pendence from Mexico in 1836 and joined the Union in

1845. Three years later, an estimated 75,000 Mexican citi-

zens of modern California, Arizona, and New Mexico

became U.S. citizens when the region was transferred to the

United States following the U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

, 1846–48.

In Texas, Anglo-American settlers composed the majority

population even before Texas gained its independence from

Mexico. In California, within two years of the discovery of

gold (1848), settlers completely overwhelmed the 13,000

Spanish Californians.

Spanish immigration to the New World between 1846

and 1932 ranked fifth behind Great Britain, Italy, Austria-

Hungary, and Germany, but most of Spain’s almost 5 mil-

lion immigrants went to the remaining colonies of Cuba and

Puerto Rico. Immigration to North America remained small

during the 19th century, averaging less than 500 per year

between 1821 and 1900. As a result of the U.S. victory in

the Spanish-American War of 1898, however, substantial

numbers of Cubans and Puerto Ricans, a large percentage of

whom were of direct Spanish descent, immigrated to the

United States over the years. The United States annexed

Puerto Rico in 1898, and its people eventually gained free

access to the United States as citizens. The U.S. government

also became heavily involved in Cuban politics, particularly

during the post–World War II

COLD WAR

period, and thus

for decades granted Cubans special immigrant status. Direct

Spanish immigration jumped dramatically between 1900

and passage of the restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924,

more than 100,000 immigrants coming during that period,

but the number was small compared to that of many other

European countries. Spanish immigration revived somewhat

during the 1960s, with a little more than 100,000 coming

278 SPANISH IMMIGRATION

between 1961 and 1990. Since then, the numbers have

declined. Between 1991 and 2002, Spanish immigration to

the United States averaged less than 1,900 per year.

Spanish Basques were among the first immigrants to

arrive in Canada in the 16th century, plying the waters off

Newfoundland for fish and whales (see B

ASQUE IMMIGRA

-

TION

). In the late 18th century, Spain established a fort on

Vancouver Island, but no permanent settlement was then

made. With opportunities for New World immigration in

many Spanish-speaking lands, few Spaniards chose Canada.

During the first half of the 20th century, only a few thou-

sand arrived. The first organized Spanish immigration began

in 1957, when Spain and Canada signed an agreement facil-

itating the immigration of Spanish farmers and domestic

workers. Between 1957 and 1960, about 400 Spaniards

were brought into the country to provide these badly needed

services. After 1960, there was a steady but small number of

Spanish immigration, averaging less than 600 per year

between 1961 and 1989. Of 10,275 Spanish immigrants in

Canada in 2001, only 1,250 arrived between 1991 and

2001.

Further Reading

Bannon, John Francis. Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1513–1821.

Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Bolton, H

erber

t E. The Spanish Borderlands: A Chronicle of Old Florida

and the Southwest. 1921. R

eprint, Albuquerque: University of

Ne

w Mexico Press, 1996.

Douglass, William A., and Jon Bilbao. Amerikanauk: The Basques in

the N

ew

World. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1975.

Douglass,

William A., Carmelo Urza, and Linda White, eds. The

Basque Diaspor

a. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2000.

Gómez, R. A. “S

panish Immigration to the United States.” The Amer-

icas 19 (1962): 59–77.

H

udson, Charles. Knights of S

pain, Warriors of the Sun. Atlanta: Uni-

versity of Georgia Press, 1997.

M

ata, Fernando. “Immigrants from the Hispanic World in Canada:

Demographic Profile and Social Adaptation.” Unpublished, York

University, 1988.

Robinson, David J., ed. Migration in Colonial Spanish America. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge U

niv

ersity Press, 1991.

Schubert, Adrian. The Land and People of Spain. New York: Harper-

Collins, 1992.

sports and immigration

Sports have long been an arena for the display of national

pride, particularly in association with the modern Olympics,

held every four years since 1896. Since World War II

(1939–45), however, sports have become increasingly inter-

nationalized, leading many of the world’s best hockey, bas-

ketball, baseball, and track athletes to North America.

Modern transportation has made it easier for players to

move from country to country, while modern communica-

tions—particularly television and satellite—have dramati-

cally enhanced sporting revenues and broadcast games fea-

turing the highest quality of individual and team perfor-

mance.

Baseball and boxing were America’s two great sports

prior to World War II. From the mid-19th century, both

were particularly associated with immigrants. As urban

sports that developed at a time when immigrants flooded

into U.S. cities in order to work in mills and factories, they

were accessible to newcomers. They relied heavily on physi-

cal prowess and required little in the way of equipment, thus

allowing anyone with real talent the potential to become

successful. In this, they were tailor made to the American

meritocratic ideal.

Although most early U.S. baseball players were Anglo-

Americans, by the late 19th century, an increasingly large

percentage were Irish and German. As the

NEW IMMIGRA

-

TION

flooded the country with immigrants from southern

and eastern Europe beginning in the 1890s, baseball stars

came from a widening circle of ethnic groups. Between 1900

and 1940, dozens of foreign-born men played in the major

leagues, including players from Germany, Ireland, Canada,

Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Eng-

land, Cuba, and Hawaii. Dozens more were second-genera-

tion immigrants still closely tied to their ethnic

communities. Some of the greatest players in the game were

proudly followed by their ethnic communities; nevertheless,

their objective successes on the field and as part of multi-

ethnic teams helped to reinforce the idea that anyone could

become an American icon. Joe DiMaggio, born to Italian

immigrants; Hank Greenberg, born to Romanian-Jewish

immigrants; and Jackie Robinson, the first African Ameri-

can allowed to play in the major leagues, all demonstrated

that ability counted more than background.

After World War II (1939–45), African Americans and

Caribbean players of mixed or African descent played an

increasingly large role in the development of baseball. Play-

ers such as Roberto Clemente, Luis Tiant, and the Alou

brothers served as visible models to young Puerto Ricans,

Cubans, and Dominicans who had developed a love of the

sport in their own countries. By 1990, 13 percent of major

leaguers were Hispanic, and by 1997, the figure had jumped

to 24 percent. In 2002, 230 of 827 players on opening day

major league rosters were born outside the 50 states: 79 from

the Dominican Republic; 38 from Puerto Rico; 37 from

Venezuela; 17 from Mexico; 11 from Japan; 10 from both

Canada and Cuba; seven from Panama; six from South

Korea; three from both Australia and Colombia; two each

from Aruba, the Netherlands Antilles, and Nicaragua; and

one each from England, Germany, and Vietnam. According

to a February 4, 2002, commissioner’s report, 42 percent of

all professional baseball players came from outside the

United States; more than three-fourths of those were from

the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. Of the 3,066 for-

eign-born professional players, 1,630 (53 percent) were

SPORTS AND IMMIGRATION 279

from the Dominican Republic and 744 (24 percent) were

from Venezuela; 165 (5 percent) from Puerto Rico; 114 (4

percent) from Mexico; 26 were from Cuba, with half on

major league rosters.

Boxing was another sport well suited to the rough,

urban life of industrial, immigrant America. The first box-

ing champion of the United States, Yankee Sullivan, was

born in Ireland. Even more popular was John L. Sullivan, a

second-generation Irishman, whose name became a house-

hold word as the sport expanded and developed. His defeat

of another Irish American, Paddy Ryan, in 1882 is some-

times viewed as the first true title fight in American history.

If the Irish dominated early boxing, Jewish fighters were

especially prominent between 1910 and 1940, when they

won 26 world titles. Two of America’s greatest fighters were

Jack Dempsey, born to Irish immigrant stock, and Rocky

Marciano (Rocco Marchegiano), whose father emigrated

from Italy during World War I.

Immigrant and ethnic players were long associated with

basketball but did not become prominent in the American

consciousness until the sport itself became more popular in

the 1960s and 1970s. Basketball was particularly associated

with the inner cities, as it did not require the large field asso-

ciated with baseball or football. Prior to World War II, the

early professional clubs were dominated by Irish, Jewish, and

Italian players. As they increasingly moved to the suburbs,

however, African Americans began to predominate and by

1995 made up 82 percent of the National Basketball Asso-

ciation. As a result of the game’s success outside the United

States and Canada, more Europeans, Africans, Australians,

Asians, and Latin Americans began to play, and the 1990s

saw the rise of many international stars, including Hakeem

Olajuwon (Nigeria), Patrick Ewing (Jamaica), Toni Kukoˇc

(Croatia), Vlade Divac (Serbia), Tim Duncan (St. Croix),

and Dirk Nowitzki (Germany) and a host of potential future

stars in Yao Ming (China), Peja Stojakovi´c (Serbia), and

Pau Gasol (Spain). By 2002, the percentage of African

Americans was down to 78 percent, and the 2003 draft sug-

gested that foreign players would take a greater number of

slots in the future. Of the 58 draft picks, 21 were from for-

eign countries, and eight of these were taken in the first

round. Many commentators speculated that the game

itself—not just the players—was being fundamentally

changed.

Canada’s preeminent sport, hockey, has also seen an

influx of international players in the 1990s. Hockey was first

played in Canada in the early 19th century. It gradually

spread to the United States, beginning in the 1890s, and

then to Europe just after the turn of the 20th century. Until

World War II, it remained largely a North American sport,

but the seeds that were planted in the first Olympic compe-

tition in 1920 eventually grew into a European fascination

for the sport. In 1956, the Soviet Union won a gold medal

in the first Olympic ice hockey competition it entered and

dominated international competition for a quarter century.

Ulf Sterner became the first Swedish player in the National

Hockey League (NHL) in 1965, and the better European

players gradually were brought to play in the world’s top

hockey league. By the 1990s, they were considered essential

in reviving a sport that lagged behind football, basketball,

and baseball in terms of public support. At the beginning of

the 2002–03 season, the international character of the NHL

was never more evident. Of the 383 players on opening-day

rosters, only 53.6 percent were Canadian; represented sig-

nificantly were the United States (13 percent), the Czech

Republic (8.2 percent), Russia (6.9 percent), Sweden (6.2

percent), Finland (5 percent), and Slovakia (2.9 percent).

Some observers feared that North American sports, as

they became internationalized, were losing part of their

essential national character. There were also fears that sport

was becoming too closely tied to international politics and

finance. Some African Americans, for instance, feared that

white European players were being courted because of

greater television marketability. And there was no question

that New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner’s pursuit

of Hideki Matsui in the 2002–03 offseason was as much

about tapping into the Japanese market as gaining the ser-

vices of a good ballplayer. With the decline of communism

around the world from the late 1980s, top athletes from for-

mer communist countries were free to market themselves

internationally in a way they could not have before. The

communist countries that did remain found athletes more

likely than ever to defect. In 1991, René Arocha became

the first Cuban player from the island country’s famed

national team to defect, while on a stopover in Miami. Over

the following decade, more than 50 players followed. Liván

Hernández defected to Mexico in 1995 and two years later

led the Florida Marlins to a world championship. This

became an important post–

COLD WAR

victory, as Hernán-

dez’s achievements overshadowed the reburial on Cuban soil

of the bones of revolutionary hero Ernesto “Che” Guevera,

an act heavily promoted by Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Further Reading

Bodner, Allen. When Boxing Was a J

ewish Sport. Westport, Conn.:

Praeger, 1997.

Coleman, Jim. Hockey Is Our Game: Canada in the World of Interna-

tional Hockey. Toronto: K

ey Porter Books, 1987.

Fainaru, Steve, and Ray Sánchez. The Duke of Havana: Baseball, Cuba,

and the Sear

ch for the American Dream. New York: Villard, 2001.

Gorn, Elliot J. The Manly Ar

t: B

are-Knuckle Prize Fighting in Amer-

ica. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1986.

Klein, Alan M. Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream.

Ne

w Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991.

Krich, John. El Beisbol: The Pleasures and Passions of the Latin Ameri-

can Game. N

ew York: Ivan R. Dee, 2002.

Levine, Peter. Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jew-

ish E

xperience. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

280 SPORTS AND IMMIGRATION

McGraw, Dan. “The Foreign Invasion of the American Game.” Vil-

lage Voice, May 28–June 3, 2003. Available online. URL: http://

ww

w.villagevoice.com/print/issues/0322/mcgraw.php. Accessed

December 29, 2003.

Mrozek, Donald J. Sport and American Mentality. Knoxville: Univer-

sity of

Tennessee Press, 1983.

Price, S. L. Pitching ar

ound Fidel: A Journey into the Heart of Cuban

S

ports. New York: Ecco, 2002.

Riess, Stev

en A. City Games: The Evolution of American Urban Society

and the Rise of Spor

ts. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

S

tark, Jayson. “Age Issues Brought on by Sept. 11.” ESPN Sports.

April 17, 2002. Available online. URL: http://espn.go.com/

mlb/columns/stark_jayson/1339359.html. Accessed March 23,

2003.

Westerbeek, Hans, and Aaron Smith. Sport Business in the Global Mar-

ketplace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Wheeler

, Lonnie. “O

ur Game? Influx of Foreign Players Changing

Basketball.” Cincinnati Post, July 1, 2003. Available online.

U

R

L: http://www.journalnow.com/servlet/Satellite?pagename=

WSJ%2FMGArticle%2FWSJ_BasicArticle&c=MGArticle&cid

=1031769914028&path=!sports&s=1037645509200. Accessed

December 29, 2003.

Sri Lankan immigration

Most Sri Lankans in the United States and Canada are pro-

fessionals or come from professional backgrounds and thus

have done relatively well economically. According to the U.S.

census of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 24,587

Americans and 61,315 Canadian claimed Sri Lankan ances-

try. The majority of Sri Lankan Americans live in California

and New York City, with significant communities in

Chicago, Texas, and Florida. The majority of Canada’s Sri

Lankans live in Ontario. Montreal was an important early

area of settlement, but large numbers began to move west-

ward, especially to Alberta and British Columbia.

Sri Lanka is a 25,000-square-mile island in the Indian

Ocean, at some points less than 20 miles off the southeast

coast of India. In 2002, the population was estimated at

19,408,635. The people are ethnically divided between two

main groups, the Sinhalese (74 percent) and the Tamil (18

percent). Roughly corresponding to the ethnic distinctions

is the religious division of the population, with 69 percent

being Buddhist and 15 percent Hindu, as well as eight per-

cent Christian and eight percent Muslim. During the fifth

century

B

.

C

., Sinhalese arrived from the mainland, estab-

lishing a kingdom and converting to Buddhism during the

third century

B

.

C

. Invading Tamils from the Madras area of

India conquered much of the Sinhalese territory starting in

the 11th century. The island was divided between the two

groups when the Portuguese arrived early in the 16th cen-

tury. The Dutch conquered the island in the 17th century,

and the English captured it in 1795, thus initiating a long

period of British rule, under which the island was known as

Ceylon.

Sri Lankan immigration began during the period of

British colonial ascendancy, particularly after 1867, when

large numbers of agricultural laborers were recruited

throughout British India. From the late 18th century until

1947, British India included all the territory from modern

Pakistan to Burma. The exact number of Sri Lankan immi-

grants is difficult to determine, as the term Indian was

applied to mor

e than a doz

en ethnic groups, including the

Sinhalese and Tamils of Ceylon (see I

NDIAN IMMIGRATION

).

Significant Sri Lankan immigration did not begin until inde-

pendence in 1948, when many educated Tamils and Sin-

halese began to leave as the country moved toward socialism.

The immigration of doctors and engineers often exceeded

the numbers being trained each year in those fields. At first,

most migrated to Great Britain; during the 1970s, the

United States and Australia became popular destinations.

In 1951, Canada initiated a quota system for South

Asian immigrants, including a provision for 50 Sri Lankans

annually. In the early 1960s, the Sri Lankan government rec-

ognized the significant drain of skilled workers from the

country and launched a series of measures to severely restrict

emigration. Beginning in 1977, it reversed policy, especially

encouraging unskilled and semi-skilled workers to seek labor

opportunities outside the country. This both alleviated prob-

lems associated with domestic poverty and led to the remit-

tance of foreign currencies. Although Sri Lanka abolished

legal discrimination against the Tamils in 1978, riots and dis-

turbances became more common, further pushing those with

skills and education to seek opportunities in the West. By the

mid-1980s, there were still only about 5,000 Sri Lankans of

various ethnic groups in Canada. As the civil conflict

between the Sinhalese and rebel Tamils evolved into full-scale

civil war in 1983, the economy was destroyed, and the island

appeared to become permanently divided, thus giving impe-

tus to significant migration. Of Canada’s 87,310 Sri Lankan

immigrants in 2001, almost 96 percent came between 1981

and 2001. In 2001 and 2002, Sri Lanka was second only to

Afghanistan in the number of refugees admitted. The civil

war continued off and on in 2003 and early 2004.

Significant Sri Lankan immigration to the United States

did not begin until the 1950s and even then remained small.

In 1980, the Sri Lankan–American population was less than

200. As the civil war developed, however, almost 16,000 Sri

Lankans immigrated to the United States by 2000. In 2001

and 2002, about 1,500 Sri Lankans immigrated each year.

Tamils and Sinhalese account for about equal percentages

of immigrants.

See also B

ANGLADESHI IMMIGRATION

;P

AKISTANI

IMMIGRATION

; S

OUTH

A

SIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Buchignani, Norman, and Doreen M. Indra, with Ram Sriv

astava.

Continuous Journey: A Social History of South Asians in Canada.

Tor

onto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

SRI LANKAN IMMIGRATION 281

De Silva, K. M. Managing Ethnic Tensions in Multi-Ethnic Societies: Sri

Lanka, 1880–1985. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America,

1986.

Leonar

d, Kar

en Isaksen. The South Asian Americans. Westport, Conn.:

G

reenwood Press, 1997.

Manogaron, Chelvadurai, and Bryan Pfaffenberger, eds. Sri Lankan

Tamils: E

thnicity and I

dentity. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press,

1994.

P

innawala, Sisira. “From Brain Drain to Guest Workers and Refugees:

The Politicies and Politics of Outmigration from Sri Lanka.” In

The Silent Debate: Asian Immigration and Racism in Canada. Eds.

E

leanor Laquian, A

prodicio Laquian, and Terry McGee. Van-

couver, Canada: Institute of Asian Research, University of British

Columbia. 1998.

Ruhanage, L. K. “Sri Lankan Labor Migration: Trends and Threats.”

Economic Review 21, no. 10 (1996): 3–7.

S

amarasinghe, S.

W. R. De A., and Vidyamali Samarasinghe, eds. His-

torical Dictionary of Sri Lanka. Lanham, M

d.: Scarecrow Press,

1997.

Sri Lanka: A Country S

tudy

. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing

Office, 1990.

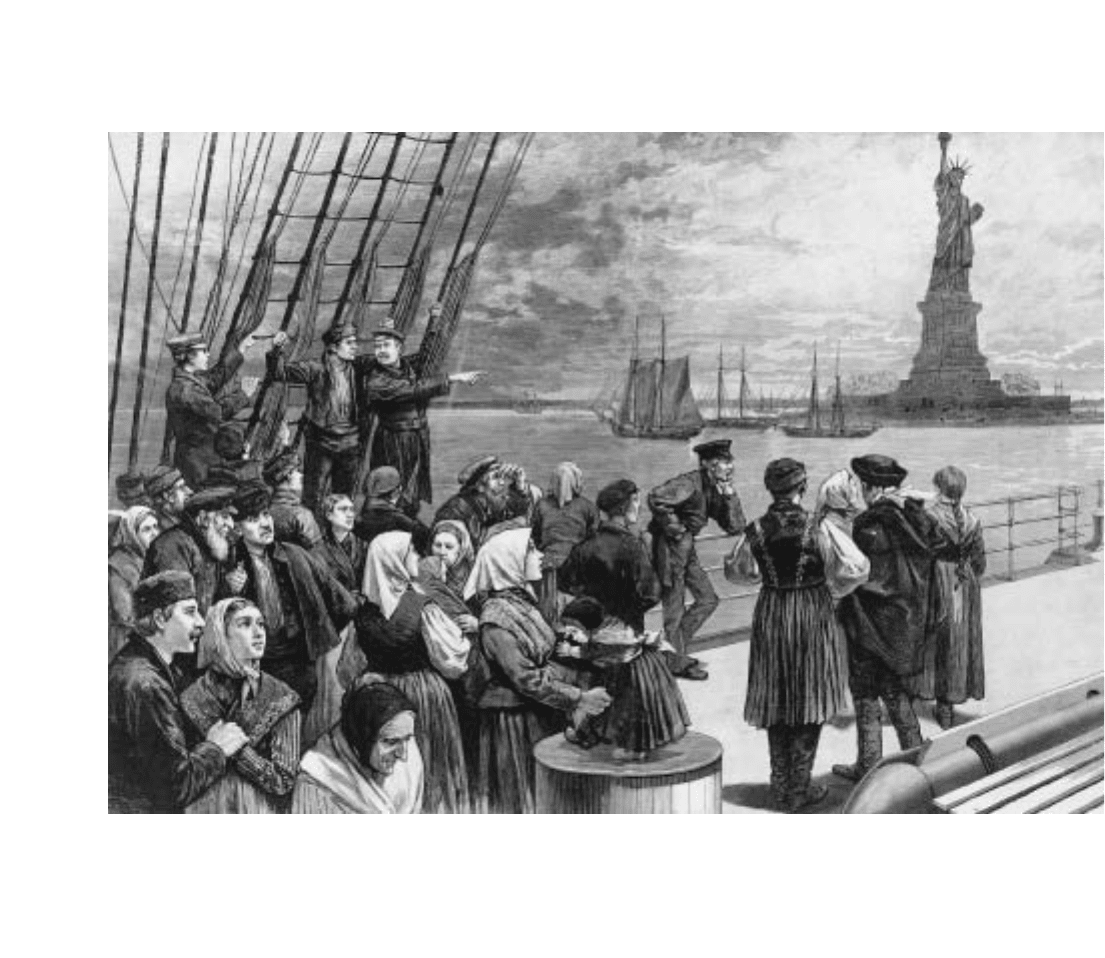

Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty is the most visible symbol of the per-

sonal freedoms that attracted immigrants to American

shores from the 17th century to the present day. Given to

the people of the United States by France in 1884 as an

expression of friendship, the statue commemorated French

aid in the dark days of the A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION

(1775–83). Since then, it has greeted every immigrant enter-

ing New York Harbor, promising freedom and opportunity.

Liberty E

nlightening the World, the official name of the

sculpture, is more than 150 feet high, not including the

pedestal or tor

ch. The bronze statue displays liberty per-

sonified, proud and graceful, holding forth the torchlight of

freedom. The seven spikes of her crown stand for the light

of liberty shining on the seven seas and seven continents. A

tablet bearing the date of the Declaration of Independence

is cradled in her left hand, and the broken chain of tyranny

lies at her feet. The statue was first proposed in 1865 by

French politician Edouard-René Lefebvre de Laboulaye,

who greatly admired the United States. During the 1870s,

the design was entrusted to sculptor Frédéric-Auguste

Bartholdi, who had visited New York City in 1871 and

chosen Bedloe’s Island in upper New York Bay as a fitting

site. While the French-American Union raised $400,000

for its construction, the American Committee, with the

help of New York publisher Joseph Pulitzer, raised

$300,000 to complete the pedestal. Designed to be the

largest statue in modern times, the daunting task of engi-

neering was given to Frenchman Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel,

who later designed Paris’s Eiffel Tower. Bartholdi had orig-

inally hoped to present the statue on the centenary of

America’s independence but settled for sending the right

hand clasping the torch, which was displayed at the Cen-

tennial Exposition in Philadelphia and later in New York

City. Liberty Enlightening the World was finally christened

on O

ctober 28, 1886, with P

resident Grover Cleveland in

attendance.

The symbolism of the statue evolved across time.

Between 1886 and 1920, the Statue of Liberty, as it was

popularly called, came to represent not just friendship

between two nations but their shared commitment to free-

dom. Immigrants eagerly lined the decks of ships as they

entered New York Harbor to catch a glimpse of the towering

bronze figure. Many cried with joy. In 1935, on his arrival

from Poland, Nobel Prize–winning writer Isaac Bashevis

Singer remembered hearing about the statue as a small boy

in Warsaw. “They all wrote about it,” he recalled, “how they

came to America, how they saw the Statue Liberty.” In

1903, a plaque inscribed with the final lines of “The New

Colossus” was placed on the pedestal. Written by Jewish

American poet Emma Lazarus, the poem embodies the ide-

als that drew immigrants to U.S. shores, as the “Mother of

Exiles” eschews the “storied pomp” of ancient glories:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

During World War I (1914–18), the statue became a

national symbol, used on recruiting posters and for selling

Liberty Bonds. For many immigrants, American freedom

meant economic freedom. One young Polish Jew remem-

bered the thrill and emotion of seeing the statue in 1920: “It

was more, not freedom from oppression, I think, but more

freedom from want. That was the biggest thrill, to see that

statue there.” For hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving

after World War II (1939–45), however, the Statue of Lib-

erty became synonymous with the “Mother of Exiles.”

In 1924, the Statue of Liberty was declared a national

monument, and in 1933 its care was handed over to the

National Park Service. In 1965, E

LLIS

I

SLAND

and Liberty

Island were joined as the Statue of Liberty National Monu-

ment.

Some 2 million people visited the Statue of Liberty each

year until the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led

to its closing, officials citing security and safety issues as the

reason. Liberty Island was reopened three months later, but

visitors were not allowed to take the famous 354-step hike to

the crown. The museum in the pedestal was reopened in

summer 2004. The symbolism of the Statue of Liberty

remains strong. According to New York City mayor Michael

Bloomberg, as long as it remains closed “in some sense the

terrorists have won.” Without dramatic improvements in

security, however, officials still considered the statue “woe-

282 STATUE OF LIBERTY

fully unprotected” and the terrorist threat to the symbol of

liberty real.

Further Reading

Hampson, Rick. “Lady Liberty’s Stairwel

ls May Never Be Full Again.”

USA Today.com. February 3, 2004. Available online. URL:

http://aolsvc.news.aol.com/news/article.adp?id=200402032307

09990037. A

ccessed February 4, 2004.

Moreno, Barry. The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. New York: Simon

and Schuster, 2000.

Spiering, Frank. Bearer of a Million Dreams: The Complete Stor

y of the

S

tatue of Liberty. Ottawa, Ill.: Jameson Books, 1986.

stereotypes See

ENTERTAINMENT AND IMMIGRA

-

TION

;

RACISM

.

Swedish immigration

Though Swedes settled in North America as early as 1638,

the great period of Swedish migration was between 1870

and 1914. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 3,998,310 Americans and

282,760 Canadians claimed Swedish descent. Although the

absolute numbers are small compared to other European

countries, Sweden ranked third, only behind Ireland and

Norway, in percentage of population to emigrate during

the 19th century. Although Chicago quickly grew to have

the second largest Swedish population in the world during

the 19th century, the 20th century led to rapid assimilation

and considerable dispersion. The greatest concentrations of

Swedes are in the American Midwest and the Canadian

provinces of British Columbia and Alberta.

Sweden occupies 158,700 square miles on the Scandi-

navian Peninsula in northern Europe. It is bordered by Nor-

way to the west, Denmark to the south (across the Kattegat),

and Finland to the east. In 2002, the population was esti-

mated at 8,875,053. Most people are ethnic Swedes (89 per-

cent), with a small Finnish minority (2 percent), and a

significant number of guest workers from many countries.

The chief religion is Evangelical Lutheran. The Swedes have

lived in the region for at least 5,000 years, about as long as

any European people. Gothic tribes from Sweden played a

SWEDISH IMMIGRATION 283

An ocean steamer passes the Statue of Liberty, as some steerage passengers enter New York Harbor. The hope in the eyes of the

variously clad immigrants is evident. In practice, many immigrants missed the sight, nervously preparing their belongings for

landing.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-9442])