Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the Tibetan United States Resettlement Project (TUSRP)

was established, with the first group of 1,000 arriving in

1992. By 2002, about 8,650 Tibetans had settled in the

United States, with about 40 percent living in the Northeast

and 20 percent in the Midwest. Between 2,000 and 3,000

Tibetans live in New York City, and there are significant

population centers in Minneapolis, Minnesota; northern

California; and Boston, Massachusetts.

There were virtually no Tibetans in Canada before 1970.

During the early 1970s, the Canadian government estab-

lished the Tibetan Refugee Program (TRP), assisting 228

Tibetan refugees then living in India to resettle in Canada.

Tibetan communities grew slowly, to a total of more than

500 by 1985. A second influx of Tibetan immigrants came

between 1998 and 2001 with the arrival of about 1,000 from

the New York City area who were granted refugee asylum sta-

tus in Canada. By 2001, the Tibetan Canadian population

had risen to more than 1,800, according to estimates. Almost

80 percent of Tibetan Canadians live in Toronto.

Further Reading

Avedon, John. In Exile from the Lands of Snows. New York: Alfred A.

Knopf, 1986.

B

arnett, Robbie, and Shirin Akiner, eds. Resistance and Reform in

T

ibet. B

loomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Conserv

ancy for Tibetan Art and Culture. “North American Tibetan

Community Cultural Needs Assessment Project Report.” Avail-

able online. URL: http://tibetanculture.org/about/work/sur-

vey.htm. Accessed July 3, 2004.

Goldstein, Melvyn. A Histor

y of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The

Demise of the Lamaist State. Berkeley: University of California

P

ress, 1989.

N

assar

, Roberta. “Social Justice Advocacy by and for Tibetan Immi-

grants: A Case Example of International and Domestic Empow-

erment.” Journal of Immigrant and R

efugee Services (2002): 21–32.

Nowak, M. Tibetan Refugees: Youth and the New Generation of Mean-

ing. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1984.

S

mith, W

arren. Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and

Sino-Tibetan Relations. Boulder, Colo.: W

estvie

w Press, 1997.

Tashi, Tsering. The Struggle for Modern Tibet. Armonk, N.Y.: M. E.

Sharpe, 1997.

U.S. Department of S

tate. “China: Country Reports on Human

Rights Practices, 2002.” Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights,

and Labor. March 31, 2003. Available online. URL:

http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2002/18239.htm. Accessed

December 31, 2003.

Tijerina, Reies López (King Tiger) (1926– )

social activist

Born in Falls City, Texas, to a family of migrant workers who

claimed to be heirs to an old land grant, Tijerina became one

of the earliest C

HICANO

activists in the United States. After

a brief career as a minister with the Assemblies of God

(1946–50), in the early 1950s he founded the utopian com-

munity of Valle de la Paz on 160 acres of land in Pinal

County, Arizona. After a hostile community burned the set-

tlement, in 1957, Tijerina jumped bail while awaiting trial

for charges stemming from the jailbreak of his brother.

While a fugitive in California, he claimed to have a mes-

sianic vision that impelled him to take up the cause of land

grant restoration. In the late 1950s, he began to research

the question of land grants that had been made by kings of

Spain and guaranteed to Mexican landholders following the

U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

. He was most interested in the

594,500-acre Tierra Amarilla land grant in northern New

Mexico. In 1963, he founded the Alianza Federal de Mer-

cedes (Federal Alliance of Land Grants, later known as the

Federal Alliance of Free City States). After years of local

campaigning and speaking to politicians with little effect, on

October 1966, Tijerina led an armed takeover of a campsite

in the Kit Carson National Forest. After the filing of federal

charges, tensions escalated with numerous cases of arson and

vandalism against Anglo ranches and federal lands. On June

5, 1967, Tijerina led the Alianza in an armed raid on Tierra

Amarilla and occupied the Rio Arriba County courthouse.

In 1974, Tijerina was sentenced to two years in prison. With

Tijerina’s imprisonment, the Alianza Federal de Mercedes

dissolved. Tijerina was paroled in December 1974 and

received an executive pardon in 1978. Thereafter he led a

secluded life, occasionally speaking out on behalf of social

causes but largely avoiding the public stage. In the early

1990s, he moved to Mexico, where he continued to work on

behalf of early land-grant claimants. In 2001, he donated his

archive of papers, photographs, diaries, and other materials

to the University of New Mexico.

Further Reading

Busto, Rudy Val. “Like a Mighty Rushing Wind: The Religious

Impulse in the Life and

Writing of Reies López Tijerina.” Ph.D.

diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1991.

Gardner, Richard. Grito! Reies Tijerina and the New Mexico Land

G

rant War of 1967. Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill, 1970.

Gutiérr

ez, José Angel. “Tracking King Tiger: The Political Surveillance

of Reies López Tijerina by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

Chicago: National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies,

1996.

Klein, Kevin. “

¡

Viva la Alianza! Thirty Years after the Tierra Amarilla

Courthouse Raid.” Weekly Alibi, June 13, 1997. Available online.

URL: http://w

eeklywir

e.com/ww106-13-97/alibi_featl.html.

Nabakov, Peter. Tijerina and the Courthouse Raid. Albuquerque: Uni-

v

ersity of N

ew Mexico Press, 1969.

Tijerina, Reies, and José Angel Gutiérrez. They Called Me “King Tiger”:

M

y S

truggle for the Land and Our Rights. Houston, Tex.: Arte

Público Pr

ess, 2000.

Tongan immigration See P

ACIFIC

I

SLANDER

IMMIGRATION

.

294 TIJERINA, REIES LÓPEZ

Toronto, Ontario

Toronto, with a municipal population of 2,481,494 and a

census metropolitan population of 4,647,960 (2001) is

Canada’s largest and most diverse city. Within a single gen-

eration during the mid-20th century, the city was dramati-

cally transformed from one of the most homogenous urban

areas in the world to one of the most ethnically diverse.

Urban affairs reporter John Barber recalls growing up in “a

tidy, prosperous, narrow-minded town where Catholicism

was considered exotic” but in 1998 found his children

“growing up in the most cosmopolitan city on Earth. The

same place.” According to Citizenship and Immigration

Canada, Toronto is “by far Canada’s premier urban center

for recent immigrants [those arriving after 1981].” In 1996,

878,000 recent immigrants were living there, more than 40

percent of Canada’s total; if undocumented immigrants are

added, almost half the city’s population is immigrant. Of

the country’s 706,921 immigrants received in Canada

between 2000 and 2002, 49 percent (346,763) came to

Toronto, further enhancing the city’s diversity. The largest

nonfounding ethnic groups living in Toronto according to

the 2001 census were Chinese (435,685), Italian (429,380),

East Indian (Asian Indian) (345,855), and German

(220,135).

Although missions, camps, and forts had been estab-

lished near the present site of Toronto, the first permanent

settlement was made in 1793 by J

OHN

G

RAVES

S

IMCOE

, the

first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada (1792–96), who

chose the site for the establishment of a new capital, named

York, for the province (now Ontario). Simcoe encouraged

settlement in the area, hoping to build a model British

colony attractive to Americans dissatisfied with their newly

formed republic. He developed a plan to establish a strong

British military presence on the frontier with the United

States. In addition to building roads and settlements, Sim-

coe offered land grants of 200–1,000 acres. Several thousand

settlers took advantage of the land grants to build the new

settlement around York. Few came from Britain, with the

majority migrating from New York (see N

EW

Y

ORK

COLONY

) and Pennsylvania (see P

ENNSYLVANIA COLONY

),

and including significant numbers of Quakers (see Q

UAKER

IMMIGRATION

), Mennonites (see M

ENNONITE IMMIGRA

-

TION

), and Dunkers. York was renamed Toronto in 1834, at

which time it had a population of about 10,000.

During the 19th century, Toronto increasingly chal-

lenged Montreal as the chief financial center of the country.

As the fur trade declined in importance, Toronto’s manu-

facturing base brought more money and workers into the

city. Also, with the expansion of rail travel and the opening

of the prairies, Toronto became a major transportation, mar-

keting, and banking center for the West. The industrial

requirements of the two world wars brought rapid popula-

tion growth, as well as hundreds of thousands of European

immigrants. In 1931, Toronto was still remarkably homoge-

nous, however, with 81 percent of the population of British

ancestry. The largest ethnic group was Jews, who seemed

remote from the city’s public persona. By World War II

(1939–45), Toronto had clearly become the commercial

center of Canada. The rapid influx of workers to the region

created numerous problems involving housing, transporta-

tion, and city services. As a result, the Ontario legislature

created the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, joining

the governments of Toronto and 12 surrounding suburbs

(1953–54). The city continued to grow rapidly in the 1950s

but mainly with European immigrants—in 1961, they still

accounted for 90 percent of immigrants coming to Toronto.

By the 1970s, Toronto was being hailed as “the city that

works,” making it one of the most desirable immigrant des-

tinations in the world. The population of the central city

peaked at just over 700,000 in 1970, then declined signifi-

cantly as immigrants poured in and longtime residents

flocked to the suburbs.

Canada’s new

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

of 1967

had a profound effect on Toronto. Although designed to

address the almost unregulated movement of sponsored

immigrants into the country, it introduced for the first time

the principal of nondiscrimination on the basis of race or

national origin, virtually ending the “white Canada” policy

that had prevailed throughout the 20th century. Toronto’s

massive manufacturing and financial base provided the best

economic opportunities for immigrants, who began to come

from all parts of the world, transforming narrow Toronto

into a city whose majority population is either first- or sec-

ond-generation immigrant. Between 2000 and 2002, the

largest immigrant groups were from China (57,604), India

(51,756), and Pakistan (32,691), with large migrations also

from the Philippines, Iran, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emi-

rates, Korea, Ukraine, Jamaica, and Russia. This massive

influx of diverse peoples led to a new round of housing,

transportation, and service problems in the 1990s that tar-

nished Toronto’s golden reputation. In November 2002,

the city council approved a new city plan preparing for the

growth of the metropolitan area by 1 million over the fol-

lowing 30 years.

Further Reading

Barber, John. “Different Colours, Changing City.” Globe & Mail,

February 20, 1998. Available online. URL: http://www.lib.

unb.ca/Texts/CJRS/Spring97/20.1_2/isin.pdf

. A

ccessed June 27,

2004.

Croucher, Sheila. “Constructing the Image of Ethnic Harmony in

Toronto, Canada.” Urban Affairs Review 32, no. 3 (J

anuary

1997): 319–347.

G

iles, Wenona. Portuguese Women in Toronto: Gender, Immigration,

and Nationalism. Toronto: U

niversity of Toronto Press, 2002.

Harney, Robert. “Ethnicities and Neighbourhoods.” In Cities and

Urbanization: C

anadian Historical Perspectives. Ed. Gilbert Stel-

ter. Tor

onto: Copp Clark Pitman, 1990.

TORONTO, ONTARIO 295

———, ed. Gathering Places: Peoples and Neighbourhoods of Toronto,

1934–1945. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario,

1985.

Harris, Richar

d. Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto’s American Tragedy,

1900–1950. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Henr

y, Frances. The Caribbean Diaspora in Toronto: Learning to Live

with Racism. B

uffalo, N.Y.: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Lemon, J

ames. Toronto since 1918: An Illustrated History. Toronto:

James Lorimer

, 1985.

Petroff, L. Sojour

ners and Settlers: The Macedonian Community in

T

oronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994.

Siemiaty

cki, Myer. “Immigration & Urban Politics in Toronto.” Paper

presented at the Third International Metropolis Conference,

Israel. Available online. URL: http://www.international.

metropolis.net/events/Israel/papers/Siemiatycki.html. Accessed

March 1, 2004.

Turner, Tana. The Composition and Implications of Metropolitan

T

or

onto’s Ethnic, Racial and Linguistic Populations 1991. Toronto:

Access and E

quity Centre, Municipality of Metropolitan

Toronto, 1995.

Vasiliadis, Peter. Whose Are You? Identity and Ethnicity among the

T

or

onto Macedonians. New York: AMS Press, 1989.

Zucchi, John E. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity.

M

ontreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1988.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo See U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

.

Trinidadian and Tobagonian immigration

Two simultaneous ethnic migrations—one black and one

Asian Indian—occurred from Trinidad and Tobago beginning

in the mid-1960s. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 164,778 Americans and 49,590

Canadians claimed either Trinidadian or Tobagonian ancestry.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) estimated

that in 2000 there were 34,000 unauthorized residents as well,

though the actual number is likely much higher. Some schol-

ars place the Canadian figure much higher, perhaps more than

150,000. In the United States, the largest concentrations are

in the New York metropolitan area and in Florida; in Canada,

more than 60 percent live in Toronto.

The country of Trinidad and Tobago occupies two

islands in the Caribbean Sea off the east coast of Venezuela,

totaling 2,000 square miles of land. In 2002, the population

was estimated at 1,169,682, with about 95 percent of the

population living on Trinidad. The people are ethnically

diverse, including blacks (40 percent), Asian Indians (14 per-

cent), and racially mixed populations (32 percent). Roman

Catholicism, Protestantism, and Hinduism are widely prac-

ticed on the islands. The islands of Trinidad and Tobago were

inhabited by Arawak and Carib Indians, respectively, when

Columbus sighted Trinidad in 1498. The native peoples were

soon killed by disease and forced plantation labor, leading to

the widespread importation of African slaves during the 17th

and 18th centuries. Great Britain, which acquired the islands

during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

(1792–1815), ended slavery in the 1830s, introducing labor-

ers from India to work the plantations. Between 1845 and

1917, about 144,000 indentured Asian Indians were brought

to Trinidad. Trinidad and Tobago were formally joined in

1889 and granted limited self-government in 1925. Between

1958 and 1961, the islands were part of an abortive West

Indian Federation that collapsed when Jamaica withdrew in

1961. Trinidad and Tobago gained their independence in

1962. The nation was one of the most prosperous in the

Caribbean, refining Middle Eastern oil and providing its own

through offshore fields. In 1990, 120 Muslim extremists cap-

tured the parliament building and TV station and took about

50 hostages including the prime minister, surrendering after

six days. Basdeo Panday, the country’s first prime minister of

Asian Indian ancestry, was elected in 1995.

Exact immigration figures are difficult to determine.

Prior to the 1960s, both the United States and Canada

treated immigrants from Caribbean Basin dependencies

and countries as a single immigrant unit known as “West

Indians.” Due to the shifting political status of territories

within the region during the period of decolonization

(1958–83) and special international circumstances in some

areas, the concept of what it meant to be West Indian

shifted across time, thus making it impossible to say with

certainty how many immigrants came from each island or

region, or when they came. Some Trinidadians and Tobag-

onians came between 1899 and 1924, when perhaps

100,000 English-speaking West Indians entered the coun-

try as industrial workers or laborers. With the opening of

a U.S. naval base on Trinidad in 1940, a number of local

inhabitants joined or provided services to the American

military. Some served during World War II (1939–45) in

Europe, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Florida. Between

1960 and 1965, 2,598 settled in the United States. Most

Trinidadians and Tobagonians in the United States immi-

grated after the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of

1965 ended racial quotas. Immigration numbers have

remained steady since that time. Between 1966 and 1985,

about 100,000 settled in the United States. After a brief

downturn in the mid-1980s, the numbers rebounded.

Between 1989 and 2002, an average of about 6,300 immi-

grated each year.

Trinidadians and Tobagonians first immigrated to

Canada in significant numbers in the 1920s, when several

hundred came to work in the mines of Nova Scotia, the ship-

yards of Collingwood, Ontario, and Halifax, Nova Scotia,

and as personal servants in the East. Some served in the Cana-

dian army during World War II and were therefore allowed

to stay as landed immigrants. Prior to the revised

IMMIGRA

-

TION REGULATIONS

of 1967, however, their numbers

remained small, with only about 100 domestic servants

296 TREATY OF GUADALUPE HIDALGO

admitted to the country each year between 1955 and 1965.

Between 1905 and 1965, the entire number admitted was

fewer than 3,000. Freed from racial quotas after 1967,

Trinidadians and Tobagonians immigrated in record num-

bers, with more than 100,000 admitted by 1990. Of Canada’s

64,145 immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago in 2001,

around 40,000 were officially listed as having arrived prior to

1991. Part of this may be explained by return migration, but

accurate figures are in any case difficult to obtain because of

possible census inaccuracies and illegal immigration.

Further Reading

Anderson W. Caribbean Immigrants: A Socio-Demographic Profile.

Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1990.

G

osine, M. C

aribbean East Indians in America: Assimilation, Adapta-

tion, and Gr

oup Experience. New York: Windsor Press, 1990.

Henr

y, Francis. The Caribbean Diaspora in Toronto. Toronto: Univer-

sity of T

oronto Press, 1994.

Kasinitz, Philip. Caribbean New York. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univer-

sity P

r

ess, 1992.

MacDonald, Scott B. Trinidad and Tobago: Democracy and Develop-

ment in the C

aribbean. N

ew York: Praeger Publishers, 1986.

Palmer

, Ransford W. Pilgrims from the Sun: West Indian Migration to

America. N

ew York: Twayne Publishers, 1995.

Reid, I

ra De Augustine. The Negro Immigrant, His Background, Char-

acteristics, and Social Adjustment, 1899–1937. N

ew York:

Columbia Univ

ersity Press, 1939.

Yelvington, Kevin A., ed. Trinidad Ethnicity. Knoxville: University of

T

ennessee P

ress, 1993.

Turkish immigration

Turkish immigration to North America, apart from large

numbers of students, has remained relatively small. It has

been supplemented, however, by a growing number of resi-

dent refugees or asylum seekers. Surrounded by instability

and war in Cyprus, Armenia, Macedonia, Syria, Iraq, Iran,

and the region of Kurdistan, Turkey has been the first stop

for thousands of refugees hoping to immigrate to North

America. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 117,575 Americans and 24,910

Canadians claimed Turkish descent. The actual number of

Turks in both countries is considerably larger, as ethnic

Turks have immigrated via Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Macedo-

nia. The largest concentration of Turkish Americans are in

New York City, and Rochester, New York; Washington,

D.C.; and Detroit, Michigan. About 58 percent of Turkish

Canadians live in Ontario, most in Toronto, and there is a

sizable Turkish community in Montreal.

Turkey occupies 297,200 square miles in Asia Minor,

stretching into continental Europe. It is bordered on the south

and east by the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas and on the

north by the Black Sea. Bulgaria and Greece border Turkey on

the west; Georgia and Armenia, on the north; Iran, on the

east; and Iraq and Syria, on the south. In 2001, the popula-

tion was estimated at 66,229,000. Turkey’s population is

diverse, including 65 percent Turks, 19 percent Kurds, 7 per-

cent Tatars, and 2 percent Arabs. More than 97 percent are

Muslims, about two-thirds of these Sunni Muslims. The his-

toric region of Asia Minor—roughly coterminus with modern

Turkey—was the center of the ancient Hittite Empire

(2000–1200

B

.

C

.) and the core of the Christian Byzantine

Empire (476–1453) and Muslim Ottoman Empire

(1453–1918). Various Turkish tribes migrating from central

Asia between the 11th and 15th centuries were converted to

Islam and progressively conquered Byzantine territories. By

1453, the last Christian stronghold, Constantinople, was con-

quered. During the 16th century, the new Ottoman Empire

expanded rapidly, conquering the Balkan Peninsula and Hun-

gary. As late as 1689, the empire was still threatening Vienna

and central Europe. The Ottoman Empire gradually declined

during the 18th and 19th centuries as European countries

rapidly embraced new technologies and industrialization. The

combined force of nationalistic movements and European

imperialism during the 19th century led to the empire’s loss of

Greece, North Africa, Serbia, Egypt, Romania, Bosnia, and

Bessarabia prior to World War I (1914–18), which the Turks

entered on the side of the losing Central Powers. At the war’s

end, Turkey lost its Arab lands (see A

RAB IMMIGRATION

;

L

EBANESE IMMIGRATION

;S

YRIAN IMMIGRATION

), but an

abortive attempt by the Allied Powers to partition Asia Minor

was beaten back by Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk,

who helped establish a republic in 1923. By the mid-1930s

Ataturk had instituted a parliamentary governmental system,

secularized the courts and education, implemented a Latin

alphabetical system, officially renamed the capital Istanbul,

promoted women’s rights, and outlawed polygyny. Since

World War II (1939–45), Turkey has been a strong Western

ally, particularly during the

COLD WAR

. It also supported the

1991 Persian Gulf War and the 2003 Iraq War. During the

later 20th century, Turkey was frequently at odds with Greece

over the governance of Cyprus and with its Arab neighbors

over the importation of Western secularism into the region.

Turks began to emigrate from the Ottoman Empire to

North America in significant numbers around 1900, with

numbers peaking between then and 1923. Most immigrants

were from the Balkans and the eastern provinces, where the

Armenian revolt was occurring. About 22,000 immigrated

during this period, more than 93 percent of these immi-

grants being men, though many returned when the Repub-

lic of Turkey was established in 1923. It has been estimated

that 86 percent of Turkish immigrants to the United States

between 1899 and 1924 returned. During the 1920s, Turks

speaking many languages, including Turkish, Kurdish, Alba-

nian, and Arabic, settled in mostly industrial enclaves

throughout the northern United States, with the largest set-

tlement in Detroit. With the Kurdish revolt against the new

secular state in the 1920s and 1930s, Turks and Kurds grad-

ually evolved separate ethnic affiliations. From World War II

TURKISH IMMIGRATION 297

until passage of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, Turkish immigration was small, mostly confined to

students. A significant portion of these were sponsored by

the Turkish military in order to promote advanced techni-

cal training for their officers. Immigration to the United

States steadily increased after 1965, averaging about 1,300

annually during the 1970s, 2,300 in the 1980s, and 3,800

in the 1990s, though many coming in the 1990s were

refugees from other countries who had first come to Turkey.

Nonrefugee immigration between 2000 and 2002 averaged

about 3,000 per year.

The limited Turkish immigration to Canada prior to the

early 1960s consisted primarily of students and professionals,

especially doctors and engineers. As in the case of the United

States, many of the students were sponsored by the Turkish

government in order to gain greater technical skills within

the military. Significant Turkish immigration to Canada

began only after 1960, though this, too, remained relatively

small. During the 1960s and early 1970s, most Turks came

for educational and economic opportunities, but with a vari-

ety of conflicts in the 1970s and 1980s erupting in Cyprus,

eastern Turkey, and Bulgaria, many left for political reasons.

Many of these immigrants were unskilled and displaced

workers, and others were refugees from the Turkish-Kurdish

conflict. Of the 16,405 Turkish immigrants in Canada in

2001, fewer than 700 came before 1961; 3,400 between

1981 and 1990; and 7,840 between 1991 and 2001. An

undetermined number of more than 4,000 Cypriots who

came between 1961 and 2001 were Turkish.

Further Reading

Ahmed, Frank. Turks in America: The Ottoman Turk’s Immigrant Expe-

rience. G

reenwich, Conn.: Columbia International, 1986.

Aijian, M. M. “Mohemmedans in the United S

tates.” The Muslim

Wor

ld 10 (1920): 30–35.

Bilge, B. “

Voluntary Associations in the Old Turkish Community of

Metropolitan Detroit.” In Muslim Communities of North Amer-

ica. Eds. Y

. Yazbeck Haddad and J. Idleman Smith. Albany: State

U

niversity of New York Press, 1994.

Davison, Roderic H. Turkey: A Short Story. 3d ed. London: Eothen

P

r

ess, 1998.

Palmer, Alan. Decline and F

all of the O

ttoman Empire. New York: M.

Evans, 1994.

Wheatcroft, Andrew. The Ottomans. London: Viking, 1994.

Yilmazkaya, E. “Resear

ch R

eport for the Multicultural History Society

on the Toronto Turkish Community.” Polyphony: The Bulletin of

the Multicultural History Society of Ontario 6, no. 1 (1984):

181–184.

Tydings-McDuffie Act (United States) (1934)

The Tydings-McDuffie Act grew out of widespread opposi-

tion, particularly in California, to the rapid influx of Fil-

ipino agricultural laborers after annexation of the islands

following the Spanish-American War in 1898 (see F

ILIPINO

IMMIGRATION

). The measure of 1934 granted the Philip-

pines commonwealth status and promised independence

within 10 years. As a result, Filipinos were reclassified as

aliens and thus no longer enjoyed unrestricted access to the

United States.

In 1910, there had been only 406 Filipinos in the main-

land United States; by 1930, the number had risen to

45,208. More than 30,000 lived in California, but they

numbered in the thousands in Washington, Oregon, Illi-

nois, and New York. Most Filipinos took jobs not easily

filled by whites, with 60 percent working in agriculture and

25 percent as janitors, valets, dishwashers, and other areas of

personal service. During the 1920s, there was already

uneasiness about the growing number of Filipinos, reviving

earlier nativist fears (see

NATIVISM

) regarding Chinese and

Japanese laborers. With the rise in unemployment during

the depression and the development of Filipino labor

activism in the early 1930s (see C

ARLOS

B

ULOSAN

), a new

reason for excluding Filipinos was added. Granting com-

monwealth status to the Philippines was largely a legal cover

for racially excluding Filipinos, who were hit especially hard

by the economic downturn of the depression. The Tydings-

McDuffie Act limited their immigration to only 50 per year.

But for the tens of thousands already in the country, it

meant that, because they were not “white” and therefore

could not become naturalized citizens, they were cut off

from New Deal work programs. In some respects, Filipinos

were in a worse position than the previously excluded Chi-

nese and Japanese, for at least Chinese merchants were

allowed to bring wives, and Japanese wives and family mem-

bers had been exempted from the restrictions of the G

EN

-

TLEMEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

. Exemptions to the act did,

however, allow Hawaiian employers to import Filipino farm

labor when needed (though remigration to the mainland

was not permitted) and enabled the United States to recruit

more than 22,000 Filipinos into the navy (between 1944

and 1973), most of whom were assigned to work in mess

halls or as personal servants.

Further Reading

Bogardus, Emory S. “Filipino Repatriation.” Sociology and Social

Research 21 (September–October 1936): 67–71.

Catapusan, Benicio

T

. “Filipino Immigrants and Public Relief in the

United States.” Sociology and Social Research 23 (July–1939):

546–554.

G

oethe, C. M. “F

ilipino Immigration Viewed as a Peril.” Current

History (January 1934), p. 354.

Moncado, Hilario. “Philippine Independence before Filipino Exclu-

sion.” Filipino Nation (May 1931), p. 9.

Saniel, Josepha M., ed. The Filipino Exclusion Mo

vement, 1927–1935.

Quezon City: University of the Philippines, 1967.

Takaki, R

onald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian

Americans. New Yor

k: Penguin, 1989.

298 TYDINGS-McDUFFIE ACT

Ukrainian immigration

Ukrainian immigration to Canada represented the largest

of any ethnic group from eastern Europe, and the Ukraini-

ans in Canada are one of the few ethnic groups with a larger

absolute population than their counterparts in the United

States. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the Cana-

dian census of 2001, 892,922 Americans and 1,071,060

Canadians claim Ukrainian descent. The greatest concen-

trations of Ukrainians in the United States are in Pennsyl-

vania, New York, New Jersey, California, and Michigan.

Ontario, British Columbia, and Manitoba have the largest

number of Ukrainian Canadians. More than 15 percent of

Winnipeg’s population is Ukrainian.

Ukraine occupies 232,800 square miles in Eastern

Europe. It is bordered by Belarus to the north; Russia to

the east and northeast; Moldova and Romania to the

southwest; and Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland to the west.

In 2002, the population was estimated at 48,760,474,

comprising mainly Ukrainians (73 percent) and Russians

(22 percent). The principal religions are Ukrainian Ortho-

dox and Ukrainian Catholic, although a large portion of

the population is not religious. The Ukraine has through-

out its history been a crossroads and a battleground. In

the first millennium

B

.

C

., the area was occupied by Cim-

merians, Scythians, and Sarmations, and in the first mil-

lennium

A

.

D

., by Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Avars, Khazars,

Magyars, and Slavs, the latter becoming the predominant

ethnocultural group in the region. The first great Slavic

state, Kievan Rus, was founded in the ninth century, in

part by Scandinavian Varangians (Vikings). It was

destroyed by the Mongols in the 13th century. From the

14th century until 1991, the Ukraine was ruled succes-

sively by Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, except for a brief

period following the Cossack uprising of 1648. Austria

ruled the Ukrainian region of Galicia from 1772 to 1918.

Ukrainians frequently tried to gain independence from

Russia, without success. After resistance to Soviet policies

of agricultural collectivization and Russification, Soviet

leader Joseph Stalin allowed 5 million Ukrainians to die in

the famine of 1932–33. During World War II (1939–45),

many Ukrainians at first welcomed the Nazi invasion of

1941, though they were treated as badly by the Germans as

they had been by the Soviets. In the wake of a Ukrainian

nationalist movement in the 1980s and the breakup of the

Soviet Union, Ukraine gained its independence in 1991. It

had a difficult time, however, making the transition to a

market economy, leading to widespread dissatisfaction

among the people.

The first significant Ukrainian immigration to the

United States came in the 1870s. Generally poor and uned-

ucated peasants from Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian

Empire (see A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

), they

usually took jobs in mines and factories in Pennsylvania,

New York, and New Jersey. Between the 1870s and 1914,

about 500,000 Ukrainians came to the United States. With

the restrictive E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

of 1921 and

J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924, quotas severely limited the

immigration of Ukrainians, and only about 15,000 came

4

299

U

prior to World War II (1939–45). During the late 1940s

and early 1950s, however, some 85,000 Ukrainians settled

in the United States, admitted under provisions of the D

IS

-

PLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

(1948) and other special legislation.

Many of these were well educated and made a relatively

smooth transition to American culture. Immediately follow-

ing the fall of the Soviet state, Ukrainians began a substan-

tial immigration to the United States, averaging almost

17,000 per year between 1992 and 2002.

Ukrainians coming to Canada first settled in Winnipeg,

Manitoba, and at Beaver Creek, Yukon Territory, in 1891,

though their numbers remained relatively small until the

later 1890s. Encouraged by the Canadian government, Dr.

Josef Oleskow traveled from L’vov (Lemberg) to explore the

western prairies in 1895 for possible Ukrainian settlement

sites. Oleskow’s subsequent publication of pamphlets

encouraged emigration, especially from the Galicia and

Bukovina regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Ukrainian immigration peaked in 1913, when more than

22,000 emigrants entered Canada. Records are imprecise, as

Ukrainians were characterized variously as Russians, Austri-

ans, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, Galicians, Bukovinians,

and Ruthenians, but it is estimated that between 1891 and

1914, about 170,000 Ukrainians immigrated to Canada.

Most of these early settlers were peasant farmers, encouraged

by the promise of inexpensive lands, who settled a frontier

area from southeastern Manitoba through Saskatchewan

and into northern Alberta. They played a major role in

transforming largely uninhabited western prairies into pro-

ductive farmland.

Some of the more than 60,000 Ukrainians who immi-

grated between the world wars were better educated, having

been involved in the abortive Ukrainian independence

movement just after World War I (1914–18; see W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

), but the largest number came

again as agriculturalists. As a nonpreferred group, they could

only come as part of family reunification, as experienced

farmers, or as farm laborers or domestics with sponsors.

After World War II (see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRA

-

TION

), about 34,000 Ukrainians came to Canada as

displaced persons. They were often well-educated profes-

sionals, and most were intensely anticommunist. They

tended to settle in industrial areas, particularly in Ontario.

By 1961, Ukrainians constituted approximately 2.6 percent

of the Canadian population (473,377), ranking behind only

the French (30.4 percent, or 18,238,247), English (23 per-

cent, or 4,195,175), Scottish (10.4 percent, or 1,902,302),

Irish (9.6 percent, or 1,753,351), and Germans (5.8 per-

cent, or 1,049,599). Of the more than 51,000 Ukrainian

immigrants in Canada in 2001, more than 21,000 came

before 1961 and about 23,000 following the dissolution of

the Soviet Union.

See also A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

OVIET

IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Gerus, O. W., and J. E. Rea. T

he Ukrainians in Canada. Ottawa:

Canadian Historical Association, 1985.

Isajiw, Wsevolod W., ed. Ukrainians in American and Canadian Soci-

ety

. J

ersey City, N.J.: M. P. Kots, 1976.

K

ubijovyc, Volodymyr, and Danylo Struk, eds. Encyclopedia of

Ukr

aine. 5 vols. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984–93.

Kuropas, M. B.

The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations,

1884–1954. T

oronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Lehr, J

ohn C. “Peopling the Prairies with Ukrainians.” In Immigration

in Canada: H

istorical Perspectives. Ed. Gerald Tulchinsky.

T

oronto: Copp Clark Longman, 1994.

Luciuk, Lubomyr Y., and Stella Hrniuk, eds. Canada’s Ukrainians:

N

egotiating an I

dentity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press and

Ukrainian Canadian Centennial Committee, 1991.

Magocsi, P

aul Robert. A Histor

y of Ukraine. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 1996.

Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period,

1891–1924. Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Stud-

ies, 1991.

M

arunchak, Michael H. The Ukrainian Canadians: A History. Rev. ed.

Winnipeg and O

ttawa: Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences,

1982.

Subtelny, O. Ukrainians in North America: An Illustrated History.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

S

wyripa, F

rances. Wedded to the Cause: Ukrainian-Canadian Women

and Ethnic I

dentity, 1891–1991. Toronto: University of Toronto

Pr

ess, 1993.

Young, Charles H. The Ukrainian Canadians: A Study in Assimilation.

Toronto: T. Nelson and Sons, 1931.

Yuzyk, Paul. Ukrainian Canadians: Their Place and Role in Canadian

Life. Toronto: Ukrainian Canadian B

usiness and P

rofessional

Federation, 1967.

Ulster

Ulster, situated in the northeastern portion of the island of

Ireland, was one of the major Irish kingdoms of the medieval

period. It was annexed by England in 1461, and the Irish

nobility was forced to swear allegiance to the English Crown.

Ongoing Irish hostility resulted in the Nine Years’ War

(1594–1603), in which an allied Spanish fleet sacked Kin-

sale, port city on the southern coast of Ireland, before England

ultimately suppressed the rebellion. The leader of the rebel-

lion, Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone, was pardoned and agreed

to work for the English Crown. In 1607, he and other lead-

ers of the rebellion fled into exile, abandoning their large

estates. The English government parceled their land to care-

takers willing to undertake the settlement of the lands, lead-

ing to the creation of widespread English and Scottish

settlements throughout the counties of Armagh, Cavan,

Donegal, Derry, Fermanagh, and Tyrone, known collectively

as the Ulster Plantation. There was naturally great hostility on

the part of native freeholders and tenants, whose rights and

traditions were frequently violated. When the systematic set-

300 ULSTER

tlement foundered, independent and individual migrations

from England and Scotland created a more fragmented settle-

ment, mixing English, Irish, and Scottish agriculturalists.

Between 1605 and 1697, it is estimated that up to 200,000

Scots and 10,000 English resettled in Ireland. Most settlers

in the early stages were poverty-stricken Lowland Scots. Start-

ing in the 1640s, however, an increasing number of High-

landers joined the migration. About 10,000 Highlanders had

been sent to suppress a rebellion in 1641, and many stayed

on, eventually bringing their families. The descendants of

these Lowland and Highland, mostly Presbyterian Scots, are

known as Scots-Irish.

More than 100,000 Scots-Irish from Ulster immigrated

to America between 1717 and 1775, mainly because of high

rents or famine and most coming from families who had

been in Ireland for several generations. In the colonial

period, these Scots-Irish were usually referred to simply as

Irish and represented the largest movement of any group

from the British Isles to British North America in the 18th

century. Together with a large emigration from Scotland

itself, this movement laid the foundation for a strong Scot-

tish ethnic component in the cultural development of both

the United States and Canada (see S

COTTISH IMMIGRA

-

TION

). In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian census

of 2001, more than 9.2 million Americans and 4.1 million

Canadians claimed either Scottish or Scots-Irish ancestry.

With the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the island of Ire-

land was divided, creating a state within the United King-

dom called Northern Ireland, which comprised six of the

nine counties of historical Ulster: Antrim, Armagh, Down,

Fermanagh, Derry, and Tyrone. The remainder of the island

became the Irish Free State, a dominion under the British

Crown. Though not exactly coterminus with either the old

medieval kingdom or the Ulster Plantation, Northern Ire-

land is sometimes referred to simply as Ulster.

Further Reading

Dunaway, Wayland. The Scotch Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania. Balti-

more: G

enealogical Publishing Company, 1997.

Fischer, David Hackett. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in Amer-

ica. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Griffin, Patrick. The People with No Name: Ireland

’

s Ulster Scots, Amer-

ica’s Scots Irish, and the Creation of the British Atlantic World,

1689–1764. Princeton, N.J.: P

rinceton U

niversity Press, 2001.

Leyburn, James. Scotch-Irish: A Social History. Reprint. Chapel Hill:

University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

R

obinson, P

hilip S. Plantation of Ulster: British Settlement in an Irish

Landscape, 1600–70. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1985.

United States—immigration survey and

policy overview

From the establishment of the first permanent English set-

tlement at Jamestown, Virginia (see V

IRGINIA COLONY

), in

1607, the area now known as the United States has attracted

more immigrants than any other country in the world. In

the colonial period, Europe had few obvious sources of

wealth, but the Spanish Empire in the New World trans-

formed Europe’s economy in the 16th century with its pro-

duction of gold and silver, and the sugar plantations of the

West Indies led to unprecedented accumulations of capital.

Even the fur trade of Canada was lucrative enough to lead

three countries to the brink of war in the Pacific Northwest.

Although the English colonies had none of these commodi-

ties in abundance, they did have good land and an equable

climate, and land was still the prime commodity for most

potential immigrants during the 17th and 18th centuries.

With the dramatic expansion of the new republic between

1783 and 1848, the United States added not only vast

expanses of land but abundant iron and coal reserves to

power the coming Industrial Revolution and precious met-

als not found east of the Appalachians. Europeans fled their

overcrowded and tradition-bound lands, flocking to the

prairies and factories of America in the greatest wave of

migration the world had ever seen. Between 1815 and 1930,

more than 50 million people left Europe for the New World,

with almost two of every three settling in the United States.

Many came to escape religious or political oppression; most

came to escape poverty, almost all to improve their eco-

nomic condition. The same opportunities that attracted

immigrants in the 19th century continued to motivate them

in the 21st century. In 2002, the United States admitted

almost 1.1 million immigrants from every part of the world,

including more than 340,000 from Asia; 362,000 from

Mexico and Central and South America; 69,000 from the

Caribbean; and 60,000 from Africa—the greatest admit-

tance rate by far of any country in the world.

Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in

the Western Hemisphere (1607), formed the core of what

would later become the royal colony of Virginia (1624).

English entrepreneurs had become interested in the Chesa-

peake region in the 1570s but found little support from

Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603). The disastrous attempt

to settle Roanoke Island (1584–87; see R

OANOKE COLONY

)

forestalled English efforts. By the early 17th century, hatred

of Spain and development of the joint-stock company pro-

vided both the diplomatic motive and the financial means

for launching a concerted colonial challenge. Unlike the sit-

uation in Spanish lands, English settlements were haphazard

and largely uncoordinated. Plymouth and M

ASSACHUSETTS

,

M

ARYLAND

, R

HODE

I

SLAND

, and P

ENNSYLVANIA

, were set-

tled first as religious havens; C

ONNECTICUT

was the result

of internal expansion; D

ELAWARE

, N

EW

J

ERSEY

, N

EW

H

AMPSHIRE

, and the C

AROLINAS

, along with Virginia, were

settled as commercial ventures; N

EW

Y

ORK

was conquered

from the Dutch; and G

EORGIA

was, somewhat incongru-

ously, both a humanitarian venture and an exercise in inter-

national diplomacy. But for a thorough mixture of all these

UNITED STATES—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW 301

reasons, the English colonies along the Atlantic seaboard

grew in population owing to immigration in a way that nei-

ther Canada nor Mexico ever would. By 1700, the popula-

tion of Virginia was 65,000, of Massachusetts 56,000, and

of Maryland 34,000. Pennsylvania, after less than two

decades, had attracted 19,000 settlers.

Throughout much of the 18th century, American set-

tlers were largely left to handle their own affairs. Govern-

ment interference—beyond the too-frequent colonial

conflicts with France that inevitably created economic dis-

ruptions—was limited, and taxes were light. With a

rapidly modernizing economy in Great Britain, recurring

famines in Ireland, and overcrowding and political insta-

bility in Germany, there was an abundance of interest in

America. And even for those without means,

INDENTURED

SERVITUDE

provided an opportunity to make a new start

in life. By 1720, the population was nearly 400,000 and

continued to grow at an unprecedented rate, swelled by the

forced migration of 250,000 African slaves, a high natural

increase, and the highest rates of immigration in the colo-

nial world. In addition to several hundred thousand

English immigrants in the colonial period, there were

250,000 Scots-Irish and 135,000 Germans, as well as

smaller numbers of Swiss, Scots, Swedes, and Jews. By the

time of the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63) with France,

the American population was about 1.5 million (as

opposed to N

EW

F

RANCE

’s European population of only

about 75,000). At the time of the American Revolution

(1775–83; see A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION AND IMMIGRA

-

TION

), it was nearing 2.5 million. Even with the loss of

40,000–50,000 Loyalists who left the new republic for

N

OVA

S

COTIA

, N

EW

B

RUNSWICK

, and Q

UEBEC

, the

American population was young, aggressive, and ample

enough to substantially develop the resources at hand.

The early period of the republic saw a slackening of

immigration. Great Britain, by far the largest source of

immigrants to America, was now sending its immigrants to

the Caribbean, South Africa, or elsewhere, and the two

countries were frequently at odds until the 1820s. The

ample agricultural lands of the transappalachian region,

however, were inviting to the starving and dispossessed,

especially as diplomatic relations gradually improved. As a

result, between 1820 and 1860 immigration increased dra-

matically each decade: 128,000 in the 1820s, 538,000 in the

1830s, 1.4 million in the 1840s, and 2.8 million in the

1850s. The Irish, driven by starvation even before the Great

Famine of the 1840s, sent almost 2 million during this

period; Germany, more than 1.5 million; and England,

Scotland, and Wales more than 800,000. With the Civil

War (1861–65) halting most immigration, the United States

consolidated itself. There were the old stock—mainly

English and Scots-Irish—and the new immigrants—the

Irish and Germans, who were by the 1870s carving

respectable niches for themselves in U.S. society, despite the

NATIVISM

of many Americans. After the Civil War, German,

British, and Irish immigration continued to predominate,

but a wave of Scandinavians brought new settlers for the

American Midwest and prairies. Between the Civil War and

World War I (1914–18) about 1.6 million Norwegians,

Swedes, and Danes came to the United States, leaving a last-

ing mark on American culture.

Accompanying the continuing growth in immigration

between 1865 and 1880 was a

NEW IMMIGRATION

, a shift

in the most common source countries. The term has most

often been used to identify the shift in immigrant trends

that occurred during the 1880s: Germany, Britain, Ireland,

Scandinavia, and other regions of western and northern

Europe were no longer the primary source countries;

instead, during the 1880s, the percentage of immigrants

from eastern and southern Europe increased dramatically.

The new immigrants came mainly from Italy, Austria-Hun-

gary, and Russia. Between 1881 and 1920, almost 24 mil-

lion immigrants were admitted, with almost 1.3 million

coming in the peak year of 1907 alone. Of these, 4.1 million

came from Italy, 4 million from Austria-Hungary, and 3.3

million from Russia and Poland. Most of these immigrants

either stayed in eastern ports or moved on to industrial

northern cities like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Cleveland,

Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; or Chicago, Illinois. Between

1900 and 1914, perhaps 3 million immigrants landed in

New York City (see N

EW

Y

ORK

,N

EW

Y

ORK

), and by 1910

the foreign-born population of that city rose to more than

40 percent. About 700,000 mostly poor Italians composed

15 percent of New York’s population.

Established Americans had always feared immigrants

and their potential influence. The first great wave of xeno-

phobia in the 1850s—born of the massive Irish and German

immigration of the previous decade—led to the formation

of the Know-Nothing Party. Pleas for restricting immigra-

tion were ignored until the panic of 1871 threw thousands

out of work, leading to 1875 legislation banning convicts

and prostitutes (see P

AGE

A

CT

), and eventually, in 1882, the

prohibition of an entire ethnic group in the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

. Prior to this time the United States had an

open immigration policy and was willing to take almost any-

one who would contribute to the development of the coun-

try. The massive wave of new immigrants from southern and

eastern Europe were valuable workers, but they also seemed

very foreign to most Americans, usually speaking no

English, with few skills, and most often either Roman

Catholic or Orthodox in faith. As a result, with the outbreak

of World War I, the growing trend toward exclusion culmi-

nated in a major revision of immigration policy.

The war had slowed immigration to a trickle (see

W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

). With growing bitter-

ness toward the principal opponents—Germany and Aus-

tria-Hungary—and a rising fear of radical politics and labor

movements with the success of the Bolshevik Revolution

302 UNITED STATES—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW

in Russia (1917), anti-immigration sentiment finally cul-

minated in a series of exclusionary measures—the I

MMI

-

GRATION

A

CT

of 1917, the E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

of

1921, and the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924—that estab-

lished literacy tests and quotas based on the 1890s popula-

tion in the United States, prior to the largest period of

immigration from eastern Europe. During the Great

Depression of the 1930s, only 500,000 immigrants were

admitted but an even greater number returned to their

homelands. World War II (1939–45; see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

) led to the easing of immigration

restrictions for allies such as China and the Philippines,

the initiation of the B

RACERO

P

ROGRAM

with Mexico, and

several special measures, including the W

AR

B

RIDES

A

CT

(1945) and D

ISPLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

s (1948, 1950), that

enabled more than 400,000 immigrants to be admitted

outside the quota system.

As the immediate postwar conflicts with the Soviet

Union evolved into the

COLD WAR

, the U.S. government

needed a new strategy for dealing with both the threat of

communism and the worldwide movement of peoples dis-

placed by more than a decade of war and oppression. The

expansion of Soviet political power and the Communist vic-

tory in China led many Americans to fear the effects of

loosely regulated immigration. This led to passage of the

McCarran Internal Security Act (September 1950), autho-

rizing the president in time of national emergency to detain

or deport anyone suspected of threatening U.S. security.

New York senator Patrick McCarran, a Democrat, went on

to argue against a more liberal immigration policy, fearing

an augmentation of the “hard-core, indigestible blocs” of

immigrants who had “not become integrated into the Amer-

ican way of life.” Together with Representative Francis Wal-

ter of Pennsylvania, also a Democrat, they drafted the

M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZA

-

TION

A

CT

(1952), which preserved the national origins

quotas then in place as the best means of preserving the “cul-

tural balance” in the nation’s population. The main provi-

sions included establishment of a new set of immigration

preferences under the national quotas, focusing on family

reunification, immigrants from the Western Hemisphere,

and skilled workers; elimination of racial restrictions on nat-

uralization; and provision for the U.S. attorney general to

temporarily “parole” persons into the United States without

a visa in times of emergency. Allotment of visas under the

McCarran-Walter Act still heavily favored northern and

western European countries, which received 85 percent of

the quota allotment.

The next major shift in American immigration policy

came with passage of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965. The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s led

to a rethinking of the quota system, and the new measure

replaced nationality quotas with hemispheric ceilings—

170,000 annually from the Eastern Hemisphere and

120,000 annually from the Western Hemisphere—with

preference for relatives of U.S. citizens and permanent resi-

dent aliens. Immediate family members of citizens could

enter without being counted against the quota. As the num-

ber of immigrants from Europe began to shrink, however,

Asian and Latin American immigration increased. In 1978,

Congress replaced the hemispheric arrangement with a sin-

gle annual quota of 290,000. By the 1980s, almost 50 per-

cent of immigrants came from Mexico, Central America,

South America, and the Caribbean, while 37 percent arrived

from Asia. Immigration from Europe and Canada declined

to only 13 percent of the total.

Two factors in the 1990s led to a growing anti-immi-

grant attitude in the United States. In 1992, 1.1 million

immigrants entered the country, the largest number since

1907, when immigration was virtually unrestricted. As a

result, by 1997 nearly 10 percent of the American population

was foreign born, almost double the percentage from 1970.

Also, an economic downturn in the mid-1990s caused an

increasing number of Americans both to fear for their jobs

and to become active in opposing expensive government

UNITED STATES—IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY OVERVIEW 303

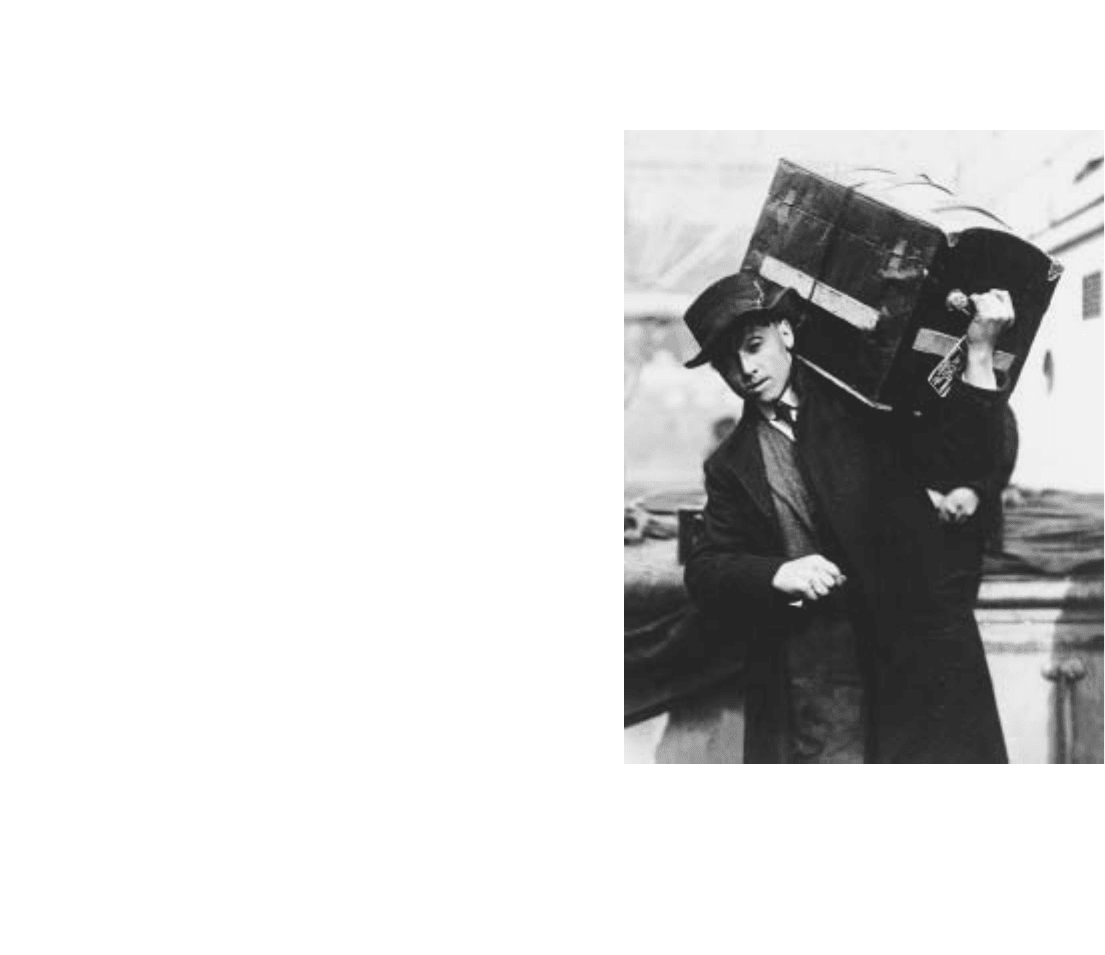

A Polish emigrant embarks for America. Acute poverty and

cultural repression drove Poles to seek opportunity in the

United States. More than 1 million immigrated to America

between 1880 and 1914.

(Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-23711])