Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

major role in the destruction of the Roman Empire. Other

Swedes, commonly known as Vikings, helped create the first

Russian state in the ninth century. As its state structure grew,

Sweden conquered the Finns during the 12th century and

united with Norway and Denmark in the 14th. In 1523,

Sweden broke away from the union and emerged by the

mid-17th century as the greatest power in northern Europe.

The country declined in international prominence after its

defeat by Russia in the Second Northern War, early in the

18th century. Sweden and Norway were again united

between 1814 and 1905 before Norway declared its full

independence. During the 20th century, Sweden has had a

reputation for noninvolvement in international affairs,

remaining neutral in both world wars. It entered the Euro-

pean Union in 1995.

In 1638, Sweden established a settlement along the

Delaware River Valley, christening it New Sweden. The

commercial enterprise never flourished, however, and by

1655, its 400 Swedish and Finnish settlers fell under the

control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland to the

north (see D

ELAWARE COLONY

;N

EW

Y

ORK COLONY

).

Most Swedish immigrants came to the United States in three

waves. Though Swedes were influenced by nationalism and

religious freedom, overpopulation and the resulting lack of

economic opportunity were by far the greatest cause of the

mass immigration. Beginning in 1840, most emigrants were

from the university towns of Uppsala and Lund. Most were

young and from good social backgrounds and often influ-

enced by romantic ideals. Gradually this migration gave way

to that of various persecuted religious groups or associations,

including the Janssonists, Baptists, and Mormons. Neither

of these migrations was large, but both established founda-

tions for later, larger migrations. As railways and steamships

improved in the 1860s, mass emigration became common.

A severe famine in the late 1860s gave impetus to the emi-

gration trend, leading about 100,000 Swedes to go to the

United States between 1868 and 1873. In some Swedish dis-

tricts, virtually every farm was represented in America, pro-

viding a social framework for prospective immigrants.

Between 1870 and 1914, about 1 million Swedes immi-

grated to the United States, and about 100,000 more during

the postwar period up to the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Although Swedish immigration revived somewhat after

World War II (1939–45)—more than 45,000 until 1970—

it declined thereafter and remained small throughout the

remainder of the 20th century. Between 1970 and 2000,

Swedish immigration to the United States averaged about

1,000 per year.

The first significant migration of Swedes to Canada

began after 1890. Heavy promotion by the Canadian gov-

ernment, completion of the transcontinental railway in

1885, and declining availability of homesteads in the United

States led an increasing number of Swedes to look for agri-

cultural opportunities on the Canadian prairies. Figures

prior to World War I (1914–18) are problematic, as Swedes

were often enumerated with Norwegians or Scandinavians

generally, and if they migrated north directly from the

United States, they would have been listed as Americans. A

reasonable estimate for the Swedish immigration between

1893 and 1914 is about 40,000. About 11,000 more came

directly from Sweden during the 1920s, but immigration

virtually halted during the depression and war years. The

earliest Swedish settlements were concentrated in Manitoba,

but by the 1920s, the greatest numbers of Swedes were liv-

ing in Saskatchewan. After World War II, a generally healthy

economy and extensive social services kept many Swedes

from emigrating. In 2001, there were only 6,810 Swedish

immigrants living in Canada, and 36 percent of them had

come before 1961.

Further Reading

Barr, Elinor Berglund. The Swedish E

xperience in Canada: An Anno-

tated Bibliography. Proceedings from the Swedish Emigrant Insti-

tute, no. 4 (1991).

Barton, H. Arnold. A F

olk Divided: Homeland S

w

edes and Swedish

Americans, 1840–1940. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University

Pr

ess, 1994.

284 SWEDISH IMMIGRATION

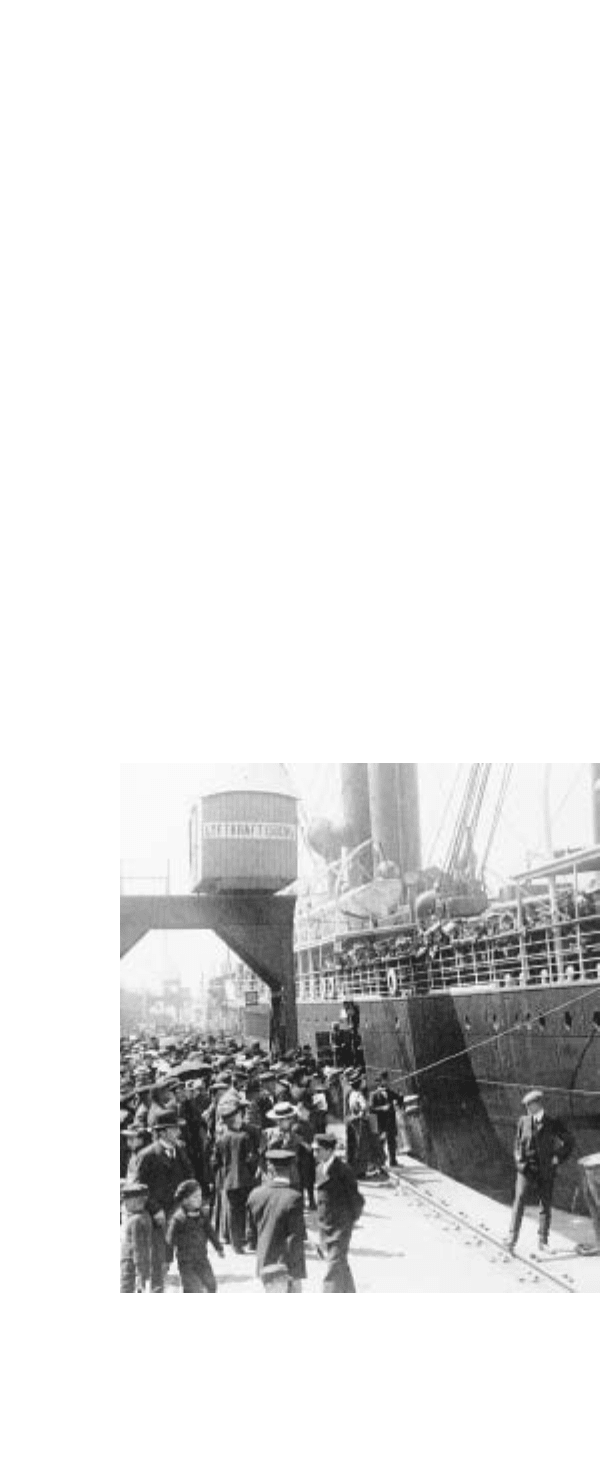

Swedish emigrants bound for England and the United States

board steamer at Göteborg, Sweden, ca. 1905. Most Swedes

initially came to America for land, though it was increasingly

difficult to find after 1900.Within a decade, more than half of

all Swedes were city dwellers, with Chicago becoming second

only to Stockholm in Swedish population.

(Library of Congress,

Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-94340])

Blanck, Dag, and Harald Runblom, eds. Swedish Life in American

Cities. Uppsala, Sweden: Center for Multiethnic Research, 1991.

Kastrup

, Allan. The Swedish Heritage in America. St. Paul, Minn.:

Swedish Council of America, 1975.

Lindberg, J

ohn S. The Background of Swedish Emigration to the United

S

tates. M

inneapolis, Minn.: n.p., 1930.

Lindmark, S. Swedish America, 1914–1932: Studies in Ethnicity with

an E

mphasis on Illinois and Minnesota. Chicago: Swedish Pio-

neer Historical S

ociety, 1971.

Ljungmark, Lars. Sw

edish Exodus. 2

d ed. Carbondale: Southern Illi-

nois University Press, 1996.

Nelson, Helge. The Swedes and the Swedish Settlements in North Amer-

ica. 2 vols. Lund, Sweden: Gleerups Forlag, 1943.

O

stergren, Robert C. A Community Transplanted: The Trans-Atlantic

Experience of a S

wedish Immigrant Settlement in the Upper Mid-

dle West, 1835–1915. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,

1988.

R

unblom, H

arald, and Hans Norman, eds. From Sweden to America:

A H

istory of the Migration. Minneapolis and Uppsala, Sweden:

University of M

innesota and University of Uppsala, 1976.

Weslager, C. A. New Sweden on the Delaware, 1638–1655. Walling-

for

d, P

a.: Middle Atlantic Press, 1990.

Swiss immigration

The Swiss were among the earliest non-British or non-

French European settlers in both the United States and

Canada, with a substantial immigration during the 18th

century. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 911,502 Americans and 110,800

Canadians claimed Swiss descent. The Swiss were readily

assimilated in North America and thus are widely dispersed.

Though they do not live in ethnic enclaves, the Swiss in

North America are most concentrated in California, New

York, New Jersey, and Wisconsin in the United States and in

Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver in Canada.

Switzerland occupies 15,300 square miles in the Alps

Mountains in central Europe. It is bordered by France on

the west, Italy on the south, Austria on the east, and Ger-

many on the north. In 2002, the population was estimated

at 7,283,274. About 80 percent of the population is Swiss:

The country has three official languages that are the mother

tongues of a given percentage of all Swiss: German (65 per-

cent), French (18 percent), and Italian (12 percent). The

largest ethnic minorities are Yugoslav (4.7 percent), Italian

(4.6 percent), and Portuguese (1.9 percent), most of whom

came as laborers. The chief religions are Roman Catholic

and Protestant, though much of the population is only

nominally religious. Switzerland, the former Roman

province of Helvetia, traces its modern history to 1291,

when three cantons created a defensive league. Other can-

tons were subsequently admitted to the Swiss Confedera-

tion, which obtained its independence from the Holy

Roman Empire through the Peace of Westphalia (1648). As

a mountainous, resource-poor country, Switzerland

exported its troops as mercenaries as a means of generating

wealth, while at the same time maintaining national neu-

trality in time of war. Switzerland has not been involved in

a foreign war since 1515. The cantons were joined under a

federal constitution in 1848, with each retaining significant

autonomous powers. A world banking and commercial cen-

ter, Switzerland is also the seat of many United Nations and

other international agencies. In an effort to crack down on

criminal transactions, the nation’s strict bank-secrecy rules

have been eased since 1990. Stung by charges that assets

seized by the Nazis of Germany and deposited in Swiss

banks in World War II (1939–45) had not been properly

returned, the government announced on March 5, 1997, a

$4.7 billion fund to compensate victims of the Holocaust

and other catastrophes. Swiss banks agreed on August 12,

1998, to pay $1.25 billion in reparations.

Among the earliest Swiss immigrants to North Amer-

ica were German Mennonites, perhaps as many as several

thousand, who began settling in the P

ENNSYLVANIA

COLONY

during the late 17th century (see M

ENNONITE

IMMIGRATION

). As more Swiss came in succeeding decades

from a variety of religious and linguistic traditions, they

spread widely throughout the colonies, though the greatest

concentrations were in N

EW

Y

ORK COLONY

. Between 1700

and 1776, about 25,000 Swiss immigrants settled in the

United States, most coming for economic reasons, although

the linguistic and cultural differences between the various

cantons were a hindrance to social mobility within their own

country. Swiss immigration continued in a small but steady

stream throughout the 19th century. Even in the 18th cen-

tury, the Swiss blended well with their neighbors, often join-

ing Moravians or other groups of “plain people.” Between

1851 and 1880, average annual immigration was almost

2,500, and families gradually moved into Indiana, Illinois,

Wisconsin, and other Midwest destinations. During the

1880s, the number jumped dramatically to almost 8,200 per

year before slipping back to about 3,000 per year between

1891 and 1930. As with all European countries, immigra-

tion was almost halted during the Great Depression (1930s)

and World War II (1939–45). Between 1971 and 2000,

Swiss immigration was steady, averaging a little less than

1,000 per year.

Almost all the earliest Swiss settlers to Canada were

mercenaries, who had first been hired by either the French

or the English to help protect their holdings. A handful

came in this way at various times in the 17th and 18th cen-

turies, though there were no large Swiss settlements estab-

lished. The greatest Swiss contribution to Canadian

settlement came in the person of F

REDERICK

H

ALDIMAND

,

who joined the British army in 1756 and distinguished him-

self during the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63), rising to the

position of lieutenant general. In 1777, Haldimand was

appointed governor of Quebec and given the formidable

task of finding homes there for some 10,000 Loyalists,

SWISS IMMIGRATION 285

mostly farmers from the Pennsylvania and New York back-

country, who had begun to congregate in Montreal and

Quebec after 1775. Haldimand eventually resettled more

than 6,000 Loyalists in the wilderness of western Quebec

(modern Ontario), north of the St. Lawrence and Lake

Ontario. Two Swiss regiments were brought to Canada dur-

ing the War of 1812 (1812–14), and many of the soldiers

stayed on, principally in Ontario. A significant number of

Pennsylvania Mennonites of Swiss descent immigrated to

Upper Canada (later Ontario) as early as the 1780s, forming

the basis of a developing German-speaking community.

Swiss immigration to Canada tended to be small but steady,

with the immigrants easily assimilating with other cultural

groups. In 1871, the census showed just under 3,000 Swiss

in Canada and about 4,500 10 years later. It is estimated

that between 1887 and 1974 about 35,000 Swiss immi-

grated to Canada, though a significant but undetermined

number returned to Europe. As in the case of the United

States, Swiss immigration in the post–World War II era has

been small but consistent. Of 20,020 Swiss immigrants liv-

ing in Canada in 2001, 3,695 came between 1961 and

1970; 3,985, between 1971 and 1980; 3,450, between 1981

and 1990; and 5,025, between 1991 and 2000.

Further Reading

Bovay, Émile-Henri. Le Canada et les Suisses, 1604–1974. Fribourg,

Switzerland: Éditions universitaires, 1976.

F

ertig, G. “Transatlantic Migration from German-Speaking Parts of

Central Europe, 1600–1800: Proportions, Structures, and Expla-

nations.” In Europeans on the M

o

ve. Ed. N. Canny. Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1994.

Gentilli, J. The Settlement of Swiss Ticino Immigr

ants. Nedlands:

D

epartment of Geography, Western Australia University, 1988.

Grueningen, J. P. von. The Swiss in the United States. Madison, Wis.:

S

wiss-American H

istorical Society, 1940.

Magee, Joan. The Swiss in Ontario. Windsor, Canada: Electra Press,

1991.

R

oth, Lorraine. “S

wiss Elements of the Mennonite Mosaic in

Ontario.” Mennonite Historian 15, nos. 1–2 (1989): 1–2.

Schelbert, Leo

. Swiss in North America. Philadelphia: Balch Institute,

1974.

Syrian immigration

Syrian Christians began to emigrate from the Muslim

Ottoman Empire in large numbers after 1880. Of the

250,000 who left in the following quarter century, more

than 60,000 settled in North America, many becoming ped-

dlers, shopkeepers, or small businessowners in large urban

areas. In the 2000 U.S. census and 2001 Canadian census,

142,897 Americans and 22,065 Canadians claimed Syrian

descent. Most Syrian Americans are descendants of this early

immigration. The largest concentrations in the United

States are in New York City; Detroit, Michigan; Chicago,

Illinois; and Dallas, Texas, though they are in general fairly

widespread throughout the country. About half of Syrian

Canadians live in the province of Quebec.

The modern state of Syria occupies 71,000 square miles

in the Middle East, at the eastern end of the Mediterranean

Sea. It is bordered by Lebanon and Israel on the west, Jordan

on the south, Iraq on the east, and Turkey on the north. In

2002, the population was estimated at 16,728,808. The

people are 90 percent Arab. The chief religions are Sunni

Islam (74 percent), other forms of Islam (14 percent), and

Christianity (10 percent). Syria was the site of some of the

most ancient civilizations, forming parts of the Babylonian,

Assyrian, Hittite, and Persian Empires. It was the center of

the Greek Seleucid Empire but later was absorbed by Rome

before being conquered by Arab armies in the seventh cen-

tury. The Ottoman Empire ruled Syria from 1513 through

the end of World War I (1914–18), after which the territo-

ries separated from Turkey by the Treaty of Sèvres (1920)

were divided into the states of Syria and Greater Lebanon,

both administered under a French League of Nations man-

date between 1920 and 1941. With the establishment of the

state of Israel in 1948, Syria refused to accept the new state’s

legitimacy and played a prominent role in ongoing military

attempts to destroy it, particularly in 1948, 1967, 1973, and

1982. During the 1980s, Syria came to play a prominent

role in governing war-torn Lebanon, a role it had not com-

pletely relinquished by 2004. Syria’s role in promoting inter-

national terrorism led to the breaking of diplomatic relations

with Great Britain and to limited sanctions by the European

Community in 1986, though the 1990s saw a moderation

of its policies. Syria condemned the August 1990 Iraqi inva-

sion of Kuwait and sent troops to help Allied forces in the

1991 Persian Gulf War. The same year, Syria accepted U.S.

proposals for the terms of an Arab-Israeli peace conference.

Syria subsequently participated in negotiations with Israel,

but progress toward peace was slow.

It is impossible to completely separate the strands of

early Syrian-Lebanese immigration. Lebanese and Syrian

Christians both came from a common, western region of the

Ottoman Empire without distinct borders (see L

EBANESE

IMMIGRATION

). These borders would again change when

the region was divided from Turkey in 1920. Lebanon,

denoting the southern area of Syria near Mount Lebanon,

was vir

tually unkno

wn in North America, so immigrants

frequently used the term Syrian to designate the larger, mor

e

familiar

geographical region. Immigrants from the Ottoman

Empire were usually classified in the United States as being

from “Turkey in Asia,” whether Arab, Turk, or Armenian

(see A

RAB IMMIGRATION

;A

RMENIAN IMMIGRATION

;

T

URKISH IMMIGRATION

). By 1899, U.S. immigration

records began to make some distinctions, and by 1920, the

category “Syrian” was introduced into the census, though

religious distinctions still were not noticed. Throughout the

20th century, there was little consistency in designation,

principally because overall numbers remained small.

286 SYRIAN IMMIGRATION

Between 1911 and 1955, any immigrant from the region to

Canada was listed as coming from “Ottoman Greater Syria”;

afterward, they might choose either designation. Some

immigrants even changed their own self-designation as

political fortunes, as well as boundaries, changed.

The majority of Syrians in the United States are the

largely assimilated descendants of Christians who emigrated

from the Syrian and Lebanese areas of the Ottoman Empire

between 1875 and 1920. As Christians living in an Islamic

empire, they were subject to persecution, though in good

times they were afforded considerable autonomy. During

periods of drought or economic decline, however, they fre-

quently chose to emigrate. Most were Maronite, Melkite,

or Greek Orthodox Christians. A second wave of immigra-

tion after World War II (1939–45) was more diverse, with

immigrants about equally divided between Christian and

Muslim. Whereas the first immigrants were usually poor and

often illiterate, the postwar settlers were frequently well-edu-

cated professionals. Between 1989 and 2002, average immi-

gration was more than 2,600 per year.

The same patterns of immigration apply to Canada.

Most early Syrian immigrants came between 1885 and

1908, at first hoping to return to their homeland. The

immigration of both Christian and Muslim Syrians after

World War II, however, substantially changed the character

of the Syrian community in Canada. The political instabil-

ity of the 1970s and 1980s led to a significant migration,

particularly in relation to the relatively small number of

early Syrian immigrants. In 2001, immigrants accounted for

more than 70 percent of Syrian Canadians. Of the 15,680

Syrian immigrants, 11,630 (74 percent) came after 1980.

Further Reading

Abu-Laban, Baha. An Olive Branch on the Family Tree: The Arabs in

Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

Dayal, P

. M., and J. M. Kayal. The Syrian Lebanese in America: A Study

in Religion and A

ssimilation. Boston: Twayne, 1975.

Hitti, P

. K. Syrians in America. New York: George Doran, 1924.

Hooglund, E., ed. C

rossing the Waters: Arabic-Speaking Immigrants to

the United S

tates before 1940. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian

Institution, 1987.

J

abbra, N

ancy, and Joseph Jabbra. Voyageurs to a Rocky Shore: The

Lebanese and Syrians of N

ova Scotia. Halifax, Canada: Institute

of Public Affairs, D

alhousie University, 1984.

Naff, Alixa. Becoming American: The Early Arab American Experience.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985.

Orfalea, G

regory. Before the Flames: A Quest for the History of Arab

A

mericans. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988.

Sawaie, M., ed. A

rabic-Speaking Immigrants in the United States and

Canada. Lexington, Ky

.: M

azda Press, 1985.

SYRIAN IMMIGRATION 287

Taiwanese immigration

Taiwan did not become an independent country until 1949.

As one of the West’s staunchest allies in the

COLD WAR

after

1945, Taiwan has enjoyed a special relationship with the

United States, including both diplomatic and military assis-

tance in its conflict with the Communist People’s Republic

of China. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 144,795 Americans and 18,080

Canadians claimed Taiwanese descent. This figure signifi-

cantly underrepresents the actual number of Taiwanese in

North America. The highest concentrations of Taiwanese

Americans are in Los Angeles County and New York City,

while 61 percent of Taiwanese Canadians live in Vancouver,

British Columbia.

Taiwan is a 12,400-square-mile island about 100 miles

off the southeast coast of China between the East and South

China Seas. In 2002, the population was estimated at

23,370,461. The people are ethnically divided between Tai-

wanese (84 percent) and mainland Chinese (14 percent).

The chief religions are Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian (93

percent) and Christian (3 percent). Large-scale Chinese

immigration to Taiwan began from Fujian and Guangdong

Provinces in the 17th century, when the native Malayo-Poly-

nesian tribes were driven to the mountains and their culture

virtually destroyed. After a brief period of Dutch rule

(1620–62), the island came under direct control of the

mainland and was held by the Manchu government until it

was defeated in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). Taiwan

was then ruled by Japan until 1945. After the Nationalist

(Kuomintang) government of Chiang Kai-shek was defeated

by the Communists in a savage civil war (1945–49) on the

Chinese mainland, 2 million Kuomintang supporters fled to

Taiwan, establishing a base from which they intended to

reconquer China. The United States had been a strong sup-

porter of the Republic of China (on Taiwan) but on Decem-

ber 15, 1978, finally joined most of the rest of the world in

formally recognizing the Communist People’s Republic of

China (PRC). Though severing official ties with the United

States, Taiwan maintained contact via quasi-official agencies,

and the United States continued to publicly oppose any

attempt by the PRC to forcibly reacquire Taiwan. In 1987,

martial law was lifted after 38 years, and in 1991, the 43-

year period of emergency rule imposed by Chiang ended.

Taiwan held its first direct presidential election March 23,

1996. Both the Taipei, Taiwan, and the Beijing, China, gov-

ernments considered Taiwan an integral part of China,

though Taiwan resisted Beijing’s efforts in the 1990s to

expand ties to the Communist-controlled mainland. Taiwan

has had one of the world’s strongest economies throughout

its history, even during the economic recession after 1998

and was among the 10 leading capital exporters.

For a number of reasons, it is impossible to determine

how many Taiwanese there are in North America. First, the

term itself is ill defined. The aboriginal Taiwanese were not

Chinese and today are few in number. Second, the term can

be used to designate any of several ethnic groups that origi-

nally came from mainland China in the 17th and 18th cen-

turies. Finally, it is sometimes used to refer to all the peoples

4

288

T

from the Republic of China located on Taiwan, including

aboriginal tribespeople, the Minnan and Hakka peoples res-

ident there for several hundred years, and the descendants of

mainland Chinese (themselves from a variety of subgroups)

who fled to Taiwan in 1949. When self-identification is

required, as in the U.S. and Canadian censuses, many immi-

grants from Taiwan or their descendants choose “Chinese,”

as it indicates their larger identification with the modern

state of China that the Nationalists ruled prior to 1949.

Most Taiwanese immigrants to North America came for

education and business opportunities. Because the economy

has been so consistently strong, there has not been a strong

economic push factor. Between 1988 and 2002, almost

170,000 citizens of Taiwan immigrated to the United States.

Immigration to Canada has been strong but less consistent.

Between 1994 and 1998, almost 50,000 immigrated to

Canada, and Taiwan was frequently in the top five source

countries for Canadian immigration. The number declined

significantly thereafter. Of 67,095 Taiwanese immigrants in

Canada in 2001, 53,750 (80 percent) came between 1991

and 2001. Between 2000 and 2002, Taiwan was the sev-

enth leading source country for students studying in

Canada.

Further Reading

Chen, H.-S. Chinatown No More: Taiwan Immigrants in Contempor

ary

New York. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University P

ress, 1992.

Fawcett, James T., and Benjamin V. Carino, eds. Pacific Bridges: The

New Immigration from Asia and the Pacific Islands. N

ew York:

Center for Migration Studies, 1987.

F

ong, T

. P. The First Suburban Chinatown: The Remaking of Monterey

Park, California. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994.

Hing, Bill Ong. Making and Remaking A

sian America through Immi-

gration Policy, 1850–1990. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University

Pr

ess, 1993.

Liu, Po-Chi. A History of the Chinese in the United States of America,

1848–1911. Taipei, Taiwan: Commission of Overseas Chinese,

1976.

Tan, Jin, and P

atricia E. R

oy. The Chinese in Canada. Ottawa: Cana-

dian Historical Association, 1985.

T

sai, Shih-shan Henry. The Chinese Experience in America. Blooming-

ton: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Tung, W

illiam

L. The Chinese in America, 1820–1973: A Chronolog

y

and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana P

ublications, 1974.

Talon, Jean (1626–1694) government official

As intendant of the colonial territory of N

EW

F

RANCE

, Jean

Talon vigorously implemented France’s new policy of colo-

nial mercantilism. The structure of his government, a kind

of benevolent autocracy, lasted nearly 100 years until the

British takeover.

After a career in the service of Louis XIV (r.

1643–1715), in 1663, Talon was appointed intendant of

New France by J

EAN

-B

APTISTE

C

OLBERT

, thus becoming

responsible for finances and civil administration of the

region. Talon diversified the economy and promoted trade

with the French West Indies. He also pursued westward

expansion, and his government-sponsored fur-trading expe-

ditions established a pattern for private fur traders. In 1672,

he dispatched Louis Jolliet to explore the course of the Mis-

sissippi River, thus establishing French claims to the Missis-

sippi basin. After clashes with local authorities, Talon was

recalled to France in 1672. His agreement with the Com-

pany of the West Indies to bring settlers to New France was

at first successful, as more than 4,000 arrived between 1666

and 1675. The immigration could not be sustained, how-

ever, as most of those coming were indentured servants, con-

victs, soldiers released from the military, or women from

orphanages or homes of charity. An efficient administrator,

Talon also amassed a fortune during his nine-year tenure as

intendant.

Further Reading

Choquette, Leslie P. “Recruitment of French Emigrants to Canada,

1600–1760.” In “T

o Make America”: European Emigration in the

E

arly Modern Period. Eds. Ida Altman and James Horn. Berkeley:

Univ

ersity of California Press, 1991.

Eccles, William J. Canada under Louis XIV

, 1663–1701. Toronto:

M

cClelland and Stewart, 1964.

Moogk, Peter. “Reluctant Exiles: Emigrants from France in Canada

before 1760.” William and Mary Quarterly 46 (July 1989):

463–505.

Tejanos

Tejanos most often refers to Mexican-origin residents of

Texas, both native and foreign born, and the unique culture

they created. In most cases, it is interchangeable with Texas

M

exicans or M

exican Americans living in Texas. Strictly

speaking, how

ever, Mexican Americans would only apply

after 1845 when the Republic of Texas (see T

EXAS

, R

EPUB

-

LIC OF

) joined the United States, making all Mexicans there

citizens of the United States.

Tejano culture is rooted in its Spanish and Mexican his-

tory prior to 1836 and constantly fed by new immigrants

from Mexico. Between 1900 and 1929, 65 percent of all

Mexican immigrants crossed the border at Texas.

See also H

ISPANIC AND RELATED TERMS

.

terrorism and immigration

Modern terrorism is the use of violent, brutal force against

civilians and the deliberate targeting of noncombatants for

political or religious reasons. It is a tactic widely abhorred

in the legal traditions of the English and French who settled

North America. It is most often resorted to by groups that

are otherwise too weak to bring about change through legal

TERRORISM AND IMMIGRATION 289

or traditional military means. In the 19th and early 20th

centuries, terrorism was most often associated with central

and east European anarchists, socialists, and communists

who used bombings and assassinations to influence labor

policy or change the political structure. After World War II

(1939–45), it became increasingly associated with funda-

mentalist Islamic organizations who opposed pro-Israeli

policies and feared the growing secular influence of West-

ern culture. Bombings, hostage taking, and hijackings were

among the most common methods utilized by terrorists

until the 1990s, when suicide bombings became the most

common form of terrorist activity. At exactly what point

the use of subversive activity moves from legitimate means

to terrorism is closely connected with one’s cultural values.

As a result, when immigrants to North America were

involved in violence, their activities were frequently cast in

terms of terrorism. The tensions surrounding the legitimacy

of terrorism were dramatically heightened as a result of

attacks carried out by Islamic fundamentalists on S

EPTEM

-

BER

11, 2001, on U.S. soil, launching an extended public

debate over the place of terror within the Islamic commu-

nity and the ability of Muslims to be true to the more

extreme interpretations of their faith while remaining good

citizens of constitutional states.

Terrorism can be home grown. The Ku Klux Klan of

the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Weathermen of

the 1970s, and a variety of violent militia organizations of

the 1980s and 1990s all used violence as a means of address-

ing what were perceived as inequities within the legal and

constitutional framework of the country. Until September

11, the most deadly act of terrorism in North America was

the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

in Oklahoma City by two members—both born and raised

in the United States—of an antigovernment militia. Immi-

grants and outsiders have, however, been more frequently

branded as terrorists. In part, this tendency toward

NATIVISM

relates to general social and cultural differences

that are necessarily present when different ethnic groups

come into contact with one another. English colonists in

North America, for example, were quick to condemn the

British Crown’s use of “barbaric” Hessian mercenaries from

a region in Germany as a deliberate infliction of foreign vio-

lence during the American Revolution (1775–83). A par-

ticularly explosive aspect of these cultural differences was

more often evident in politics. Prior to World War I

(1914–18; see W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

), the

United States and Canada shared many assumptions and

experiences regarding immigrants. In both countries, indi-

vidual actions based on constitutional processes and repre-

sentative forms of government were upheld as the only

legitimate means of political change. Both countries barred

the entry of paupers, the mentally ill, and those considered

mentally defective. Also, immigrants routinely crossed the

border between the two countries looking for work.

In many parts of the world, however, where individual

rights were not protected and political pariticipation was not

permitted, people often embraced collective, extragovern-

mental, and even violent tactics to help bring about political

change. As a result, political movements associated with

socialism and anarchism were particularly associated with

immigrants. When an 1886 labor demonstration at the

Haymarket Square in Chicago led to a bombing in which

eight policemen were killed, hundreds of socialists and anar-

chists were arrested. Eight anarchists, seven of them German

immigrants, were convicted of conspiracy, and four were

hanged. Although three of the convicted men were eventu-

ally pardoned, the fear of immigrant radicalism lingered,

paving the way for the widespread fear of foreign political

activities in the 20th century.

Fears were heightened by a number of isolated but dra-

matic cases, including the assassination of President William

McKinley by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz in 1901. As

immigration from eastern and southern Europe peaked in

the first decade of the 20th century, labor unrest and vio-

lence increased and became most visibly represented in the

militant activities of the transnational I

NDUSTRIAL

W

ORK

-

ERS OF THE

W

ORLD

. Nativist fears were heightened by

entry into World War I, which provided a further reason

for suspecting the loyalty of Germans, Bulgarians, and Aus-

tro-Hungarians. Militant labor activity in Canada led to the

detention of 8,000–9,000 enemy aliens. When the Bolshe-

vik Revolution (1917) toppled the Russian Empire, a great

Red Scare gripped both Americans and Canadians. Forma-

tion of the One Big Union (OBU) in Canada (1919) and

the violence of the W

INNIPEG GENERAL STRIKE

(1919)

heightened ethnic tensions. In the United States, European

war and revolution led to increasingly restrictive immigrant

legislation, culminating in the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of

1924 and in a revival of a newly invigorated Ku Klux Klan

that was as much antiforeign as antiblack. In Canada, orga-

nizations that professed to “bring about any governmental,

political, social, industrial or economic change . . . by the use

of force, violence or physical injury” were declared illegal,

and entry of immigrants from former enemy states was pro-

hibited by amendments to the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

in 1919.

The period required for naturalization in Canada was also

extended by the Naturalization Act of 1920.

Although the use of violence for political purposes in

the United States and Canada declined from the 1930s,

there remained a silent mistrust of many, but not all, immi-

grant groups. The relationship between immigration and

terrorism was highlighted by two high-profile cases as the

new millennium began. In the September 11, 2001, attacks,

most of the hijackers had entered the United States legally

and engaged in pilot training while in the country. It was

later discovered that a number of them were in violation of

the terms of their entry but that the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

S

ERVICE

(INS) had not taken timely

290 TERRORISM AND IMMIGRATION

action against them. In October 2002, the Beltway Snipers

shot 13 people in the Washington, D.C., area, killing 10 of

them. The two men convicted in the attacks were John Allen

Muhammad, American-born, who was loosely associated

with the Nation of Islam, and his associate Lee Boyd Malvo,

an undocumented alien from Jamaica who was scheduled

for a deportation hearing at the time of the killings.

As a result of the September 11 attacks, the U.S. and

Canadian governments were forced to confront terrorism as

a domestic, rather than international, issue, which led to a

series of immigration and travel reforms. In the United

States the USA PATRIOT A

CT

was quickly passed, provid-

ing for greater surveillance of aliens and increasing the

power of the Office of the Attorney General to identify,

arrest, and deport aliens. The act also defined domestic ter-

r

orism to include “

acts dangerous to human life that are a

violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any

S

tate that appear to be intended to intimidate or coerce a

civilian population; to influence the policy of a government

by intimidation or coercion; or to affect the conduct of a

government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnap-

ping.” Also, monitoring of some aliens entering on nonim-

migrant visas was instituted, passport photographs were

digitalized, more extensive background checks of all appli-

cations and petitions to the D

EPARTMENT OF

H

OMELAND

S

ECURITY

were authorized, the SEVIS database was created

to track the location of aliens in the country on student

visas, and the U.S. Attorney General’s Office was given the

right to immediately expel anyone suspected of terrorist

links. Also, the State Department introduced a 20-day wait-

ing period for visa applications from men 16 to 45 years of

age from Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt,

Eritrea, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon,

Libya, Malaysia, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi

Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emi-

rates, and Yemen. Any application considered to be suspi-

cious was forwarded to the Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI), creating a further delay.

Further Reading

Avery, Donald. “Dangerous Foreigners”: European Immigrant Workers

and Labour Radicalism in Canada, 1896–1932. Toronto:

M

cClelland and Stewart, 1979.

Chang, Nancy. Silencing Political Dissent: How Post–September 11

Anti-T

err

orism Measures Threaten Our Civil Liberties. New York:

Sev

en Stories Press, 2002.

Malkin, Michelle. Invasion: How America Still Welcomes T

err

orists,

Criminals & Other Foreign Menaces to Our Shores. New York:

Regnery, 2002.

Texas, Republic of

The Republic of Texas (1836–45) was a unique experiment

in creating a multiethnic state in the New World. In the end,

the cultural pull and political push of the United States

proved irresistible to most Texans, who sought annexation to

their larger neighbor almost from the time they became

independent of Mexico.

In 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from

Spain, expansionistic pressure from the United States was an

urgent problem. The Mexican government decided on a pol-

icy of defensive immigration, encouraging Americans to set-

tle its sparsely populated northern province of Texas. It had

become clear to Mexican liberals that the Catholic Church

was already too strong and should not be given the power of

populating the north. Also, Mexico simply did not have a

sufficient population to effectively control Texas. Its entire

population, from Central America to Texas, New Mexico,

and California in the north, was only 6 million. In January

1821, Moses Austin was contracted to bring 300 Catholic

families to Texas in return for a large personal grant of land.

Moses died in June, and his contract was assumed by his

son, Stephen F. Austin. With the fall of the short-lived impe-

rial government of Agustín de Iturbide in Mexico in 1823, a

new National Colonization Law (1824) was passed, leaving

immigration policy in the hands of individual states. The for-

mer provinces of Coahuila and Texas were combined into

one state, and the land between the Nueces and Sabine

Rivers, designated the Department of Texas. Under the state’s

Colonization Law (1825), Mexicans were given priority in

land acquisition and were temporarily exempted from paying

certain taxes. Nevertheless, by the mid-1820s, there were

more Anglos than T

EJANOS

in Texas. Immigrants were

allowed to become Mexican citizens on condition that they

abide by the federal and state constitutions and practice the

Christian religion. Individuals were allowed to purchase land,

but most immigrants came with empresarios like Austin, who

worked for the state governments, and w

er

e in turn entitled

to about 23,000 acres of land for each 100 families they set-

tled. Eventually 41 empresario contracts were signed, most by

Anglo-Americans, though fe

w of the terms w

ere actually

completed. By the late 1820s, there were perhaps 10,000

immigrants and their slaves, but few took the conditions of

settlement seriously. Following a conservative coup in 1829

and the recommendation of Manuel de Mier y Terán, who

observed that the Anglo-Texans were unlikely to be assimi-

lated, the Mexican government passed the Law of April 6,

1830, in order to bring the flood of Anglo settlement under

control. The measure voided all agreements except with those

empresarios who had brought in at least 100 families already.

The measure also stipulated that Americans could not colo-

niz

e territor

y bordering on the United States. Finally, it pro-

hibited the importation of slaves. When the Mexican general

and political opportunist Antonio López de Santa Anna and

the Centralists returned to power in 1834, they not only

sought to enforce the 1830 treaty but also to curtail state lib-

erties that had been earlier guaranteed. Clashes between

Mexican Centralist forces and Texans began in October

TEXAS, REPUBLIC OF 291

1835. In November, a “Consultation” of 58 delegates from a

dozen communities met to affirm the liberal Constitution of

1824. When Texas delegates met again in March 1836, they

voted unanimously to declare independence (March 2) on

the basis of Santa Anna’s imposition of a tyranny in place of

a constitutional government. Among the 59 delegates were

three Mexicans: Lorenzo de Zavala, José Antonio Navarro,

and José Francisco Ruíz. Despite defeats at San Antonio de

Bexar (at the Alamo) and Goliad, 900 Texans under General

Sam Houston routed Santa Anna’s force of 1,500 at San Jac-

into (April 21), forcing him to sue for peace in the Treaties

of Velasco. By their terms, Santa Anna acknowledged Texas’s

independence, removed his troops to Mexico, and accepted

the Rio Grande as the southern boundary of the new Repub-

lic of Texas. Although the Mexican congress refused to ratify

the agreement, Mexico no longer had the means of recon-

quering the land.

Immediately, Texas voters indicated their wish for

annexation by the United States, favoring the establishment

of economic, social, religious, and political institutions

largely as they existed in the land from which most had

come. Sam Houston, the republic’s first president, was a

political veteran, having served as a U.S. congressman

(1823–27) and as governor of Tennessee (1827–29).

Despite economic woes and the potential danger of recon-

quest, the population of the new country grew dramatically,

from about 30,000 at independence to more than 150,000

in 1845. Much of the growth came from reestablishment of

the empresario system to encourage settlement. As a result

of this policy, I

rish, F

rench, English, Scottish, Czech, Polish,

Scandinavian, Canadian, and Swiss colonies were estab-

lished. The most important of these were the 2,100 French

speakers settled at Castroville near the Medina River west of

San Antonio and the German settlement of New Braunfels.

By 1844, sentiment in the United States was turning in

favor of annexation, with a strong national sense of manifest

destiny. When James K. Polk was elected president on an

expansionist platform in November, outgoing president

John Tyler proposed annexation of Texas through a joint res-

olution of Congress, which he signed on March 3, 1845.

The U.S. government inherited the dispute over the Texas-

Mexican border, which had not been settled in 1836, and

this eventually led to the U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

(1846–48).

See also M

EXICAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

De León, Arnoldo. The Tejano Community, 1836–1900. Albuquerque:

Univ

ersity of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Hardin, Stephen L. Texan Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revo-

lution. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

Lack, P

aul D. The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Social and Politi-

cal Histor

y. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1992.

Montejano, D

avid. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas. Austin:

Univ

ersity of Texas Press, 1987.

Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation:

Texas, Oregon, and

the Mexican War. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1973.

Tijerina, André.

Tejanos and Texas under the Mexican Flag, 1821–1836.

College S

tation: Texas A&M University Press, 1994.

W

eber, David J. The Mexican Frontier, 1821–1846: The American

Southwest under M

exico. Albuquerque: University of New Mex-

ico Pr

ess, 1982.

Thai immigration

Most Thai Americans are the product of the revised regula-

tions under the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of

1965 and the U.S. presence in Vietnam. Unlike other

Southeast Asians, however, they came to the United States

not as refugees but as professionals and spouses of members

of the U.S. military. According to the U.S. census of 2000,

150,283 Americans claimed Thai descent. Only 6,965

Canadians reported Thai ancestry in the census of 2001.

The greatest concentration of Thais in the United States is

in California, particularly in southern California, but they

are spread widely throughout the country wherever there are

large military bases associated with the former American

involvement in Southeast Asia. The majority of the small

Thai community in Canada lives in Toronto and Vancouver.

Thailand occupies 197,400 square miles on the

Indochina and Malay Peninsulas in Southeast Asia. In 2002,

the population was estimated at 61,797,751. The major eth-

nic groups in the country are Thais (75 percent) and Chi-

nese (14 percent). Around 95 percent of the people are

Buddhist and about 4 percent Muslim. Thais began migrat-

ing from southern China during the 11th century, conquer-

ing the native inhabitants and establishing a number of Thai

kingdoms. In 1350, these were united in the Kingdom of

Ayutthaya. Throughout much of its history, the Thai king-

dom waged war with the kings of Burma and Cambodia for

supremacy in the region. After 1851, Thailand became offi-

cially known as Siam, and its kings developed good relations

with the British and French. Though Siam lost some terri-

tory to both European powers, it proved to be the only

Southeast Asian country capable of resisting colonization.

During the 1930s, the Thais developed a constitutional

monarchy, leading the government to rename the country

Thailand. After occupation by Japan during World War II

(1939–45), Thailand fell largely into the hands of military

leaders, who closely allied themselves to the United States

in its

COLD WAR

conflict in Vietnam, allowing U.S. bases

to be established there. Thailand also became home to hun-

dreds of thousands of Cambodians fleeing the Pol Pot

regime after 1979. A steep downturn in the economy forced

Thailand to seek more than $15 billion in emergency inter-

national loans in August 1997, and a new constitution won

legislative approval on September 27.

There was virtually no Thai immigration to the United

States prior to the 1960s. With America’s growing presence

there during the Vietnam War (1964–75), however, Thai

292 THAI IMMIGRATION

doctors, nurses, and other professionals learned that the new

Immigration and Nationality Act gave preference to skilled

professionals, and a significant number chose to immigrate.

Many U.S. servicemen married Thai women while stationed

in Vietnam and brought them back to the United States

after the war ended. By the late 1970s, some 5,000 Thais

were in the United States, about three-quarters of them

women. Many of the others were professionals or students.

Thai immigration remained steady at an average of about

6,500 per year during the 1980s and early 1990s, but

declined to less than 3,000 per year between 1997 and

2002, in part because a large percentage of Thai families had

already been reunited. Except for students, spouses, and a

small number of professionals, there has been almost no

Thai immigration to Canada. Thailand has been politically

stable for many years, and Thais do not have a long tradition

of migration. Of 8,130 Thai immigrants in Canada in 2001,

only 50 came before 1971, and 2,930 between 1991 and

2001.

Further Reading

Kangvalert, W. “Thai Physicians in the United States: Causes and

Consequences of the Brain D

rain.” Ph.D. diss., State University

of New York at Buffalo, 1986.

Kitano, Harry H. L., and Roger Daniels. Asian Americans: Emerging

M

inorities. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1995.

Larson, W. Confessions of a M

ail Order Bride: American Life through

Thai Ey

es. Far Hills, N.J.: New Horizon Press, 1989.

Wyatt, David K. Thailand: A Short History. Reprint. New Haven,

Conn.: Y

ale U

niversity Press, 1986.

Tibetan immigration

Tibetans form one of the smallest immigrant communities

in both the United States and Canada; nevertheless, the

Dalai Lama, head of Tibet’s government in exile in Dharam-

sala, India, has focused world attention on the human rights

abuses against Buddhists in the Tibetan Autonomous

Region (TAR) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and

gained the support of most governments for enforcement

of human rights and resettlement of Tibetan refugees. Offi-

cial U.S. government policy recognizes Tibet to be a part of

the PRC and so keeps no separate immigration figures.

According to the Canadian census of 2001, 1,425 Canadi-

ans claimed Tibetan ancestry.

Tibet is a sparsely populated region occupying 471,700

square miles of high plateaus, massive mountains, and rocky

wastelands. Its 2000 population was estimated at about 2.6

million, with all but about 300,000 being Tibetans. The reli-

gion of almost all Tibetans is a branch of Buddhism called

Lamaism, which recognizes two Grand Lamas as reincar-

nated Buddhas. The Himalayas run along Tibet’s southern

border with India, Nepal, and Bhutan and the Kunlun and

Tanggula Mountains her northern border with China. Dur-

ing the seventh century, Tibet developed a powerful empire,

still remote from the main centers of Chinese culture. Tibet

borrowed heavily from Indian culture. After occupation by

the Mongols in the 13th century, the Dalai Lama became

the head of the Tibetan state until the early 19th century,

when it was conquered by China. After the Revolution of

1911 and its overthrow of the Qing dynasty in China, Tibet

became nominally independent until China reasserted con-

trol in 1951, while promising Tibetan autonomy and reli-

gious freedom. A Communist government was installed in

1953, revising the theocratic Lamaist rule, abolishing serf-

dom, and collectivizing the land. A Tibetan uprising in

China in 1956 spread to Tibet in 1959. The rebellion was

brutally crushed, and Buddhism was almost totally sup-

pressed. The Dalai Lama and 100,000 Tibetans fled as

refugees to India. Beginning in the 1960s, the Dalai Lama

became an impassioned spokesman on behalf of human

rights both in Tibet and around the world. From his capital

in exile, he has maintained informal diplomatic contact with

world leaders and proposed a self-governing Tibet “in associ-

ation with the People’s Republic of China.” Largely on the

basis of his practical attempt to solve this humanitarian crisis,

in 1989, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Chinese government was routinely condemned by

human rights organizations and most world governments,

including those of the United States and Canada, for sys-

tematic human rights abuses against Tibetans, including

arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture, secret trials, and

religious suppression. During summer and autumn 2001,

the leading center for Buddhist scholarship and practice on

the Tibetan plateau was dismantled, Chinese authorities

citing concerns over sanitation and hygiene. The Serthar

Institute (also known as the Larung Gar Monastic Encamp-

ment) had more than 8,000 monks, nuns, and lay students,

including 1,000 practitioners, before Chinese work teams

forcibly expelled the students, destroyed more than 1,000

homes, and drove thousands of nuns and monks from the

grounds. Finally, there was growing concern among Tibetans

that the Chinese government was deliberately resettling large

numbers of ethnic Chinese in Tibet for the purpose of

undermining Tibetan autonomy.

From the mid-1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA) began to train Tibetan guerrillas, as the United States

sought to undermine the expansion of Chinese Communist

influence. In 1960, the Rockefeller Foundation established

eight centers for Tibetan studies in the United States, and

the following year, the first graduate program in Buddhist

studies was opened at the University of Wisconsin. This

growing awareness of Tibet’s international plight led to the

slow migration of several hundred Tibetans, mostly religious

leaders and teachers. In the late 1960s, several dozen Tibetan

workers also immigrated to the United States. By 1985,

about 500 Tibetans lived in the United States. In 1988, with

support from private agencies and the U.S. government,

TIBETAN IMMIGRATION 293