Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1905-1914

Sahel, from 1908, and by Ahmadu Bamba on his return in 1912

to Djourbel, in Senegal, from exile in Mauritania: it marked the

beginning of

a

period of co-operation with the government which

in 1918 earned him the Legion of Honour in recognition of the

success of his recruiting operations.

In Mauritania, the opposition of marabouts (holy men), begin-

ning in 1905-6, gave cohesion to a resistance movement which

swept the whole country as far as the Upper Niger. It was led by

Shaykh Ma' al-'Aynayn, who rallied most of the Moorish tribes

and, after proclaiming himself sultan, declared a holy war in 1909.

The tribes' supplies of

arms,

which were apparently considerable,

had been obtained by trade with German merchants. Moroccan

support until 1911 and the rise of Mauritanian national feeling

made retaliation difficult. From 1910 onwards the French were

obliged to reverse their policy of alliances; instead of founding

it on the great shaykhs of the Trarza, they made use of the internal

dissension between warriors and marabouts. Henceforward the

French entrusted police duties in the Sahara to the submissive

warrior tribes, and distributed a wide range of presents, favours

and authority to their own auxiliaries, a move which, incidentally,

contributed to the distortion of traditional social values. Despite

heavy losses due to harassment by opposing guerrilla forces, the

strategy succeeded. The death of the shaykh in October 1910 left

the movement without a leader. In 1912 resistance was reduced

to isolated acts of ' social banditry' which were finally subdued

by the drought of 1913.

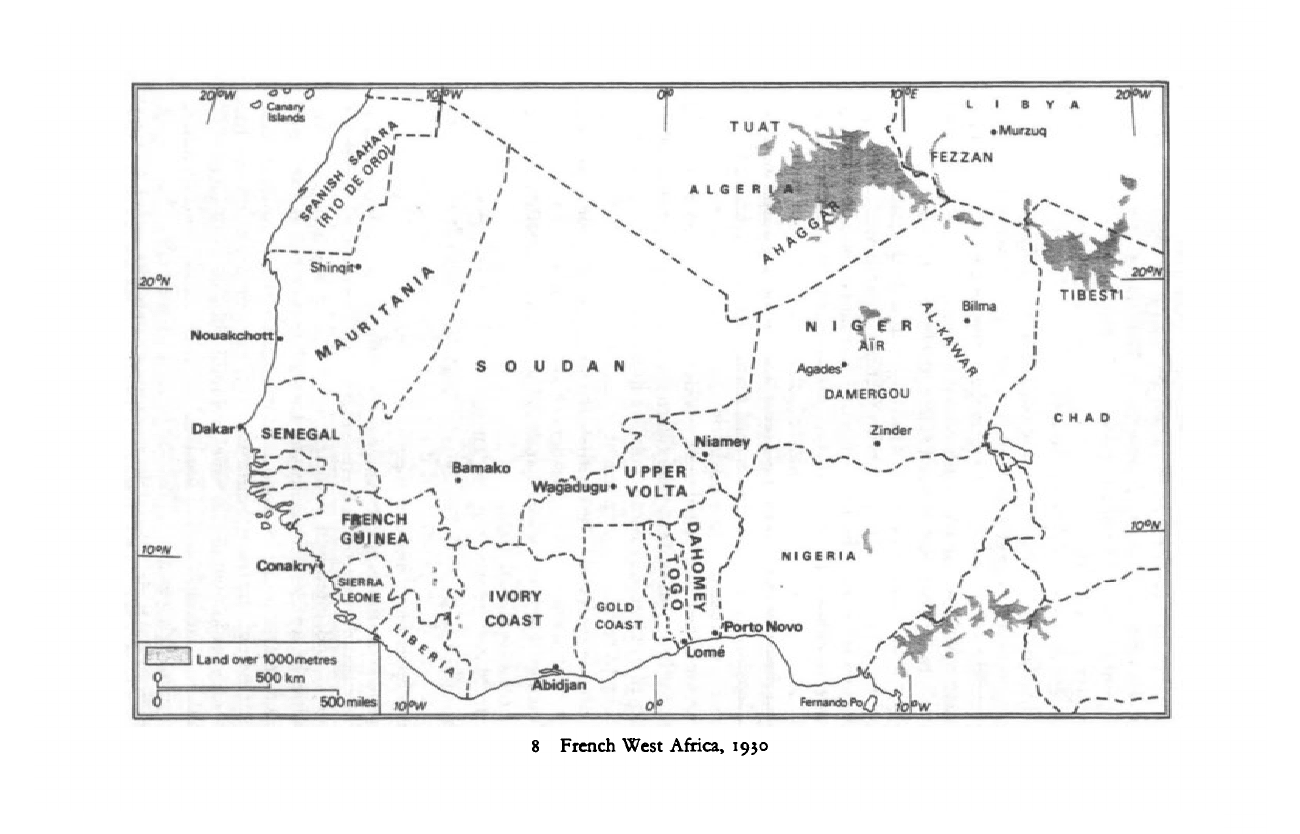

In Niger the rising of the Tuareg of Air in 1916-17 was a late

example of 'primary resistance' by peoples who had hitherto

remained independent, and it involved a typical combination of

ethnic, religious and socio-economic factors. The arrival of the

French constituted an attack on both cultural and technical fronts.

They had destroyed the trans-Saharan traffic, commandeered the

camels and interfered with the unwritten laws which gave the

Sultan of Agades his livelihood. Instead, they imposed a series of

interpreter-intermediaries on whom the local people concentrated

their hatred. In the drought of 1913-14, which was one of the

worst ever known in the Sahel, claiming thousands of victims in

middle Niger and killing livestock, French requisitions of millet

were bitterly resented. The war in Europe weakened the French

position and their isolated desert outposts were evacuated. In 1915

33*

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

20j<>W

O Canary

blinds

20°N

20»N

10°N

- —^ v Bilma

",

N

i <%e

R

^

AIR

\

1Q0N

1

Land over KXX)metres

500 km

500miles

lOpw

8 French West Africa, 1950

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1905-1914

the tribes revolted, at the instigation of the marabouts. In spite

of a setback, when black reserve forces made common cause with

French troops, the end of 1916 brought together the Tuareg who

were loyal to the Qadiriyya brotherhood and the Sanusi force of

the Targui of Damergou, who united in the three-month siege

of the fort at Agades. The repression which followed was

merciless and all the marabouts of Agades were beheaded.

Nevertheless, raids and counter-raids continued until 1931 among

the ruined oases of the north-eastern desert.

Elsewhere, however, there was in the end small reason for

French apprehension. The great religious leaders knew that their

liberty depended on their docility, which could also bring

considerable material benefits. Among the Mande peoples, the

marabouts, so recently warriors, now appeared anxious to exert

a peaceful influence over the animist peoples. They proved

effective and Islam made enormous progress. In middle Casa-

mance, for example, the Diola of Fooni underwent a mass

conversion, instigated by some powerful marabouts, many of

whom, like Chelif Yunus of Wadai, were of foreign origin.

Further up-river, in the Fulaadu country, the rise of the Sarakole

marabout Suleyman Bayaga, who in 1908 undertook to build a

mosque, aroused considerable opposition from the administra-

tion; he fled to the Gambia and was eventually pursued and killed.

But this was an exception.

In 1908 the Mossi of the upper Volta region mounted their last

major resistance. It was led by the marabout Alassane Moumani

of Ramongo, who called on people both to be converted and to

refuse to pay taxes. In the name of Islam, he succeeded in acting

as a catalyst for malcontents of

all

classes, especially those leaders

who,

at the heart of this kingdom with its remarkable hierarchic

structure, resented the erosion of their authority by the French.

Two thousand armed men approached Wagadugu, but they were

rapidly subdued; the marabout was killed and the subsidy of the

Mossi ruler, the

mogho

naba,

was reduced by a quarter. In 1914,

a few months after war had broken out in Europe, the French

believed they had uncovered a vast Muslim conspiracy. Most

Muslim leaders in the upper Volta region were arrested and in

1915 heavy penalties were proclaimed for 'any anti-French

propaganda or call to a Holy War'. Since nothing further was

proved, there was a fairly rapid return to the policy of

collaboration.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

In Ubangi-Shari and Chad, the French regarded Islam primarily

as a political instrument of power over subjugated animist

peoples, and a policy of collaboration proved still more effective.

In the upper Ubangi area the administration economised by

relying on local sultans, who had previously wielded considerable

military power and were now commercial agents of the conces-

sionary companies. Further north, the Sanusiyya gave the French

rather more trouble. In a region which had been ravaged by

slave-running brigands, the brotherhood controlling the great

pilgrim highway had brought peace of a sort by promoting

religious conversion and centralising political control. Direct

confrontation came about in 1910 with the deportation of the

sultan of Dar el-Kuti. Similarly in 1908 the French set out to

conquer Wadai, which since the middle of the nineteenth century

had been the most firmly unified state in this part of Africa. In

1909 they seized its capital, Abeshr (Abeche), and replaced the

sultan by a prince turned bureaucrat who in turn was deposed in

1912.

Thereafter the marabouts formed a centre of ideological

resistance linked to the royal family, in a situation rendered

unstable by the great famine of 1913-14 and by the First World

War. In 1917 — the year of all-out recruitment for the war —

the military authority reacted fiercely to the distribution of an

Arabic propaganda leaflet. The four principal marabouts were

arrested in November, but the 'Senegalese' troops, left to their

own devices, massacred almost the entire upper class. The city of

Abeshr was emptied of many of its people, including its

intellectuals, who took refuge in the Sudan. However, the

struggle against the Sanusiyya was not over until 1931, when the

Italians destroyed all their communities in Libya.

In non-Muslim areas the colonising power was obstructed by

a variety of political units bent on preserving their own identity.

This was most clearly demonstrated in the Ivory Coast. During

the phase known — somewhat misleadingly — as 'peaceful

conquest' (1903-7), colonial authority was extended very grad-

ually by negotiation. But Governor Angoulvant (1908—18)

initiated a deliberate programme of conquest, characterised by

military operations on

a

grand scale. He implemented a decree of

1904 which provided for the deportation of

leaders,

the payment

of collective war indemnity and the surrender of all firearms still

retained by the people: between 1909 and 1915 more than 110,000

334

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1905-1914

firearms were seized. When in 1910 Angoulvant's methods

aroused violent controversy in France, he defended himself with

a reference to Gallieni and the association between moral and

military conquest. However this may be, the myth of 'peaceful

conquest' must be demolished. Angoulvant was hardly an

innovator in colonial warfare, apart from his readiness to extol

the advantages of the 'short war'. By the eve of the First World

War, the Ivory Coast had been almost wholly subjugated.

Elsewhere military intervention, if less spectacular, was equally

persistent. Detailed local studies have shown that at the start of

the twentieth century penetration was only just beginning. In the

forests of lower Casamance, tax-collection began in the early

1900s, but there were still police operations in 1908 and not till

the 1920s was it possible to move about freely in relative safety.

However, these Diola resistance movements reflected local social

structure and were never the expression of

a

people united in arms.

The trouble-centres, numerous but sporadic, reacted spasmod-

ically to all aggression of a political, economic or cultural kind.

In south-eastern Dahomey, from 1905, the Hollidje, a cluster of

16 forest villages not far from Pobe, which was soon to be a

railway terminus, repeatedly refused to pay taxes and resisted

forced labour. Insurrection broke out in January 1914 and its

suppression continued until June. The disarmament of the

inhabitants, the doubling of the tax and the arrest of the leaders

left the population as refractory as ever until the early 1920s.

' It

is

easy to forget,' noted an observer in 190

5,'

that the Congo

has never been conquered, that there has been no effective

take-over of the vast territories of our colony.'

1

Thus there were

persistent local and regional reactions, so that it is quite erroneous

to talk of'peaceful colonisation'.

2

Besides, there is a disturbing

coincidence between the most unstable regions — Nyanga, upper

Ngounia, Ibenga and Lobaye — and those where the conces-

sionary companies or the administration committed acts of serious

violence. Systematic campaigns of repression, which began in

1908,

continued until 1911 and even until 1918. Subsequently,

such

'

primary resistance' was not to occur very often, except in

1

'Union Congolaisc Franchise' to the Minister of Colonies, 28 March 1905, Archives

rationales, Section Outre-Mer, Concessions 25 D (1).

2

H. Ziegle, Afrique iquatoriale

fran^aise

(Paris, 1952),

ioo;cf.

Cambridge

history of Africa,

vi (1985), 3ii-"4-

335

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

isolated areas not yet penetrated by the colonial administration,

such as eastern Gabon in 1928-9. A local

chief,

Wongo, had been

paying tax since 1923, but revolt was triggered off

by

the creation

of obligatory markets in the region, which were charged with

supplying the government outposts and which at the same time

afforded a pretext for raising taxes and forced levies. In a zone

characterised by a very diffuse power-structure, both the cohesion

of the resistance movement and its duration was extraordinary:

it required two years and several campaigns to bring it to a close.

With this belated exception, the regular collection of taxes,

regarded as the criterion of true subjection, was virtually estab-

lished in all areas by the start of the First World War.

The French administration

In French West Africa the basis for federal organisation was

established in 1904 by the creation of a general budget financed

by the revenue from all indirect taxes, particularly customs duties,

and intended specifically to pay for public works. The governor-

general had his seat at Dakar and was assisted by annual sessions

of

a

consultative government council, composed of the secretary-

general, the commander-in-chief of the forces, the attorney-

general, the departmental heads of the civil service, the governors

of the different colonies and several prominent personalities, both

European and African, as nominated members. It was the

governor-general who actually held all the power, though the

resident Europeans, especially traders, who attended council

meetings undoubtedly exerted influence on colonial policy. The

governor-general was responsible solely to the minister of

colonies, who appointed him and to whom he alone had access;

he was beyond the control of the elected deputies and senators

in the French parliament. In each colony the lieutenant-governor

(later, governor) was likewise appointed by the minister. In

Senegal, he was advised by an executive council consisting largely

of officials; such councils were later introduced in other colonies.

In French Equatorial Africa the commissioner-general (upgraded

in 1908 to governor-general) was invested with supreme authority,

both political and administrative, for all four territories; his

consultative council was composed entirely of nominated mem-

336

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

r

1905-1914

bers.

Locally, power was exercised by

commandants

of provinces.

3

Nearly all, by now, had come from the Ecole Coloniale which,

since 1890, had been a symbol of imperial unity. Originally, in

her eagerness to civilise and assimilate, France had intended to

create a single government training-school, designed to produce

officials who would be interchangeable and of universal suitability,

capable of exercising the most varied functions throughout all the

territories. Since, however, the school could not supply enough

candidates for all the subordinate posts, the 'employees and

assistants for native affairs' (later to be called 'civil affairs')

continued for several years to be of miscellaneous and mainly local

origin.

The personal characteristics of these colonial administrators are

hard to define. Some of the officials who followed the first

generation of explorers were distinguished successors to them.

Especially eminent were Georges Bruel and Maurice Delafosse;

the latter's work (for long unequalled) on Upper Senegal-Niger

and on translations of Arabic texts was reckoned among the most

valuable contributions to the growth of African studies. Such

researches, however, depended entirely on the personal qualities

of the administrator, at a time when ' the African' was generally

regarded as a big child, lazy and troublesome, whom it was

necessary above all to subdue and discipline. Although straight-

forward adventurers and financially embarrassed younger sons

became increasingly rare, most officials continued to be prompted

by related psychological factors, such as a taste for authority,

responsibility and danger, a need for independence and an

appetite for discovery. Their common ideological aim was to raise

Africans to the level of' civilisation' by inculcating French social

and cultural values, but with a view to efficiency and results.

'From non-commissioned officer to Governor-General, colonial

society is European in its devotion to progress, or to what it calls

progress, and in its pride in controlling the means to it, be it the

rifle or the railway, the lottery or the Order in Council. '

4

Within his province, the administrator exercised total authority

over several thousand people: he was at the same time head of

government, judge, tax-collector and commissioner of police, and

3

This term is used here to refer to the major territorial subdivisions, variously called

cercles

or

circonscriptions;

these were often further divided into districts.

4

R. Delavignette, Les Vrais Chefs de /'empire (Paris, 19J9), 55.

357

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

poor communications meant that he was largely independent of

his superiors. His principal task, at least until the war, was to levy

taxes.

For several reasons the administration placed exceptional

stress on this thankless task. Taxation regularly collected was the

outward

and

visible sign

of

the 'pacification'

of

the territory.

Besides, although

the

colonies were poor,

it

was necessary

for

them, according to the opinion of the day, to be self-supporting,

and taxation was, along with customs duties, the only source of

revenue. In Madagascar Gallieni extolled the' educational function

of taxation'

;

s

in

black Africa too the French saw

it

as the only

method of compelling people to earn money, to produce for the

market and enter the modern economy. Taxation was accordingly

introduced

in all

territories between

1900 and

1910. When

administrators were required

to

find money

in

areas which had

scarcely begun to use it, they found it. by forcible means: auxiliary

troops sacked

and

terrorised villages, beat

up or

murdered

recalcitrants and seized hostages; such excesses were especially rife

in Equatorial Africa. Thus, even if the assessment of personal head

tax did not

in

itself seem excessive, being between two and five

francs

a

year before 1914 on

a

wage —

if

any —

of

about 20

to

50

francs a month, the imposition was remembered with particular

revulsion. People became terrified of the

commandant;

they

fled

and

they rebelled.

In these conditions it was difficult for the administrator to win

people over by practising

a

consistent' native policy'; ill-equipped

and seldom kept

in one

post

for

more than

two

years,

he

improvised measures which his successor was likely to overturn.

He was, however, the only one

in a

position

to do

anything

at

all.

One of the few instruments put into his hands was the judicial

function, which was gradually institutionalised. 'Native justice',

strictly speaking, was based on customary practices, so far as they

had been reconstructed and so far as they were compatible with

French law. In the civil and commercial sphere, two jurisdictions

existed side

by

side. From 1912, Africans could obtain French

citizenship, but the high qualifications required put

it

beyond the

reach of

all

but a few; besides, it imposed monogamy and military

service.

6

All other native Africans were French ' subjects', bound

5

Title

of

a circular

of

30 November 1904,

Journal officiel

di

Madagascar,

1904, 12045.

6

For details, see Lord Hailey,

An

African

survey.

A

study

of

problems arising

in Africa

south

of

the

Sahara (London, 1958), 199;

for the

special case

of

Senegal,

see

below,

pp.

350-1, 360-1.

338

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

1905-1914

by African law and custom as administered by recognised courts.

In the court of first instance, two African assessors assisted the

administrator who served as president. For the court of second

instance, at provincial level, the structure was identical, but

Africans were included only in a consultative capacity. With each

advance to a higher court, the European presence increased its

impact. In the capital of the colony was the criminal or assize

court, to which two European assessors were also attached, and

in the court of appeal the president was assisted by two European

administrators and two prominent Africans. Finally, at the federal

level, the Supreme Native Court of Appeal included only two

Africans.

7

Beneath this theoretical framework of jurisdiction, the ordinary

African was subject in the first place to the penal system for

'natives'

(indigenaf).

From 1907 in French West Africa and 1909

in French Equatorial Africa, administrators had secured the

unfettered right to inflict on 'natives' penalties not exceeding a

fine of 100 francs and fifteen days' imprisonment for such offences

against colonial authority as ' disorderly acts', ' seditious talk' or

refusal to pay taxes, forced contributions or requisitions. After the

war, certain categories, such as ex-soldiers, the more important

chiefs and selected

evolues

(Africans literate in French) were

exempted from this jurisdiction. Nevertheless, until 1946 it

rendered the administrator in office an almost absolute ruler,

whose province was

a

personal

fief

inhabited by' his' natives,' his'

guards,'

his'

land-agent. Africans were left in no doubt: the true

heir to the armed chief of the past was now the

commandant,

the

white

chief.

Despite the personal courage and the undeniable

goodwill of

a

great many administrators, the system inevitably led

to the growth of abuses, so long as shortage of personnel

prevented the official in authority from being effectively supported

by technical experts in agriculture or public health, as was

generally the case until 1920.

The early

stages

of

economic

growth

Colonial expansion was from the beginning sponsored in France

only by a committed minority. Public opinion was generally

7

It also included a presiding magistrate, two counsellors and two administrators.

339

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

apprehensive of the risks of conquest; businessmen hesitated to

risk their capital in a field which offered so little security; and in

parliament there were annual attempts to reduce the colonial

budget. Nevertheless, from about 1910, in spite of some violent

indictments of colonial atrocities in Africa,

8

no one any longer

urged that colonies there should be abandoned. The exaltation of

the national idea at the beginning of the century created an

atmosphere in which everyone was disposed to see in the

'

African

epic'

the opportunity for France to assert herself as a great power

alongside Britain. At the same time, all agreed that the colonies

should not cost the mother-country anything. From 1905 to 1914

the colonies accounted for between 5.7 and 7.8 per cent of

France's total public expenditure, the maximum being in 1913.

These percentages included military expenditure, which in black

Africa represented

80

to 89 per cent of the total.

9

Besides, the main

burden was Algeria.

The main lines of economic strategy had been shaped by the

'colonial party', a parliamentary cross-section of diverse elements.

It caused French Equatorial Africa to be given over to concession

companies, but in French West Africa it promoted freedom of

competition for private enterprise. This seeming paradox arose

from the expectations of colonial pressure groups in relation to

widely differing local interests and contexts.

After the scandals of

1905

in French Equatorial Africa,

10

it was

realised that the ' solution by means of concessions', based on

commercial monopoly and coercion, was doomed. Yet for lack

of legal means of intervention, the system remained intact until

the First World War, and the only successful companies were

precisely those which plundered most systematically. Over twelve

years the Compagnie des Sultanats du Haut-Oubangui, with 14

million hectares, contributed as much to the state as all the others

put together. Its output was modest (some 38 tons of rubber and

35 tons of ivory a year), but its profits reached 100 per cent and

more. Such results were the fruit of a robber-economy operated

by commercial companies which had made no investment and had

8

E.g. the pamphlet by Vigne d'Octon, La Gloire du sabre (Paris, 1900); Leon Bloy,

Le Sang des pauvres, on the depravity of colonial customs; and criticisms by the socialist

group around Pierre Mille, in Let Cabkrs de la

quin^aine

(1905-1908).

9

F. Bobrie,' Finances publiques et conquete coloniale: le cout budgetaire de l'expansion

franchise entre 1850 et 1913', Arma/es, 1976, 31, 6, 1225-44.

10

See Cambridge history of Africa, vi (1985), j 14-15.

340

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008