Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

communes. The ministry emphasised the liberal character of the

reform, in that it ended the dichotomy between ' territories under

direct administration' and 'protectorates'. The elite of the

originates, however, objected to the moderating role to be

exercised by twenty chiefs chosen by their peers and deemed to

represent their followers, as distinct from the twenty members to

be elected henceforward by all citizens of the colony (and not just

inhabitants of the communes). These councillor-chiefs could

scarcely act

as

a check on the governor and provincial

commandants

on whom their careers depended. The council became essentially

a ratifying body which confined itself at its annual session to airing

views on matters placed before it by the lieutenant-governor and

to suggesting supplementary expenditures for budgets already

approved by the Council of Government (whose members were

either appointed

exofficio

or nominated by the governor-general).

41

The process was taken further by the erosion of municipal

prerogatives: in 1924 the territory of Dakar and dependencies (to

which Goree was reattached in 1929) was invested with budgetary

autonomy but placed under a representative of the governor-

general; in 1937 this official replaced the mayor when Rufisque

was reattached.

As for the territories seized from Germany, the French

government, like the British, favoured outright annexation. They

were opposed by President Wilson, who was supported in France

by the Socialists and by advocates of a League of Nations,

including the ' League of Intellectual Solidarity for the Triumph

of

the

International Cause' which was launched in 1918 by Andre

Gide, Anatole France, Jules Romains and others. In February

1919 the former German colonies were designated 'mandates of

the League of Nations'; these were to be entrusted to those Allied

powers 'which by reason of their resources, experience and

geographical position are best qualified to assume this respons-

ibility [over] peoples not yet capable of governing themselves

[but whose] welfare and development are a sacred mission for

civilisation \

42

Each mandatory power was required to submit an annual report

on its stewardship to the

League.

Meanwhile, France had consulted

41

Journal officitl de

la

Kcpublique frattfaise, December 1920, 20245

et

se

1->

a

"d

L'Ouest

africain franfais,

IJ

February 1929,

3.

42

First Covenant

of

the League

of

Nations,

13

February 1919.

361

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

chiefs

and

notables in Togo and Cameroun; all but one were said

to wish

her to

remain, though some also took

the

opportunity

to make demands

of

their own, whether

for a

university

or for

the protection

of the

privileges

of

Duala chiefs.

43

In May 1919

France received mandates over much

of

Togo (where Britain

handed over Lome and

the

railways)

and

Cameroun; that part

of

Cameroun which had been ceded to the Germans in 1911 was now

restored

to

France

and

re-annexed

to

French Equatorial Africa.

The rapid replacement of German personnel, both in the public

service (partly

by

citizens

of the

four communes)

and in the

private sector (especially missionary groups) gave rise

to con-

fusion.

In

northern Cameroun

a

sort

of

indirect rule continued

to prevail, based

on the

traditional authority

and

militia

of the

great sultans

of

Ngaoundere, Rey Bouba and Maroua.

In

Douala

and

the

rest

of the

coastal zone,

the

upheavals among minor

officials exposed people

to

extortion by anyone who had got hold

of something like

a

uniform.

And it was

only

in 1919

that

the

French allowed

the

return

of the

20,000 Africans

who had

followed

the

Germans

in

their retreat

to

Spanish Guinea

and

Fernando Po. These people

had

mostly been

to

mission schools

and

had

been

the

mainstay

of the

German regime; they were

mainly Beti from

the

Yaounde region. Among them was Charles

Atangana,

who had

been educated

in

Hamburg

and

appointed

'supreme chief

of

the Beti

in

1914; after some months

in

prison

he regained

his

post

in

1920

and

held

it

until

his

death

in 1943.

The French occupation

of

Cameroun

did not go

unopposed.

In

the north, they

had to

deal with mountain peoples

who had

scarcely been brought under colonial rule

and had

always been

hostile

to

the Fulani sultans. And in 1919-20 the Bape of the Bafia

region, rich

in

oil-palms, were brutally repressed: villages were

razed, the inhabitants dispersed and a military post set up to watch

over

the

country.

By and

large, however, Cameroun remained

calm. The small-scale communities

in

the south did not yet realise

that they

had a

common master. True,

the

people

of

Douala

resented the reorganisation of local justice, since the Germans had

left this

to

local notables,

but in

fact

the

French used much

the

same

people.

Once civilian rule had been re-established, Cameroun

was provided,

in

1920,

with a consultative Council of Administra-

43

Memorandum

of

the Duala chiefs,

1

December 1918. Archives nationales, Paris:

Section Outre-Mer,

AP II,

C.28D1.

362

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

tion on the pattern of other colonies and was gradually integrated,

more or less, into French Equatorial Africa; French Togoland

likewise became part of French West Africa. Up to 1934, these

mandates were subject to a ban on the establishment of military

bases and the recruiting of African troops, but there was frequent

interchange of colonial officials between mandates and colonies.

The practice of indirect rule persisted in French Africa wherever

local powers were both able and willing to implement colonial

demands. Such was the case in Futa Jalon and western Senegal,

the home of the Murids. While Ahmadu Bamba lived on as a

religious sage until 1927, his kindred busied themselves in giving

his teaching an economic content; in Wolof country, the spread

of Islam was linked to control over land and markets. Sanctified

by their religious association, the local patriarchs placed at the

service of the groundnut economy the unremitting labour of

100,000 followers, who were thereby assured both of survival in

a hard world and of salvation in the life hereafter. This economic

collaboration between Murid chiefs and French officials was but

one example of

a

growing French preference for allying with those

Muslim groups which controlled so much internal trade and

production. This was in line both with France's new desire to

increase the value of French Africa and with her renewed

ambition to become a great Muslim power: in 1923 the govern-

ment launched a subscription fund for building a mosque in Paris.

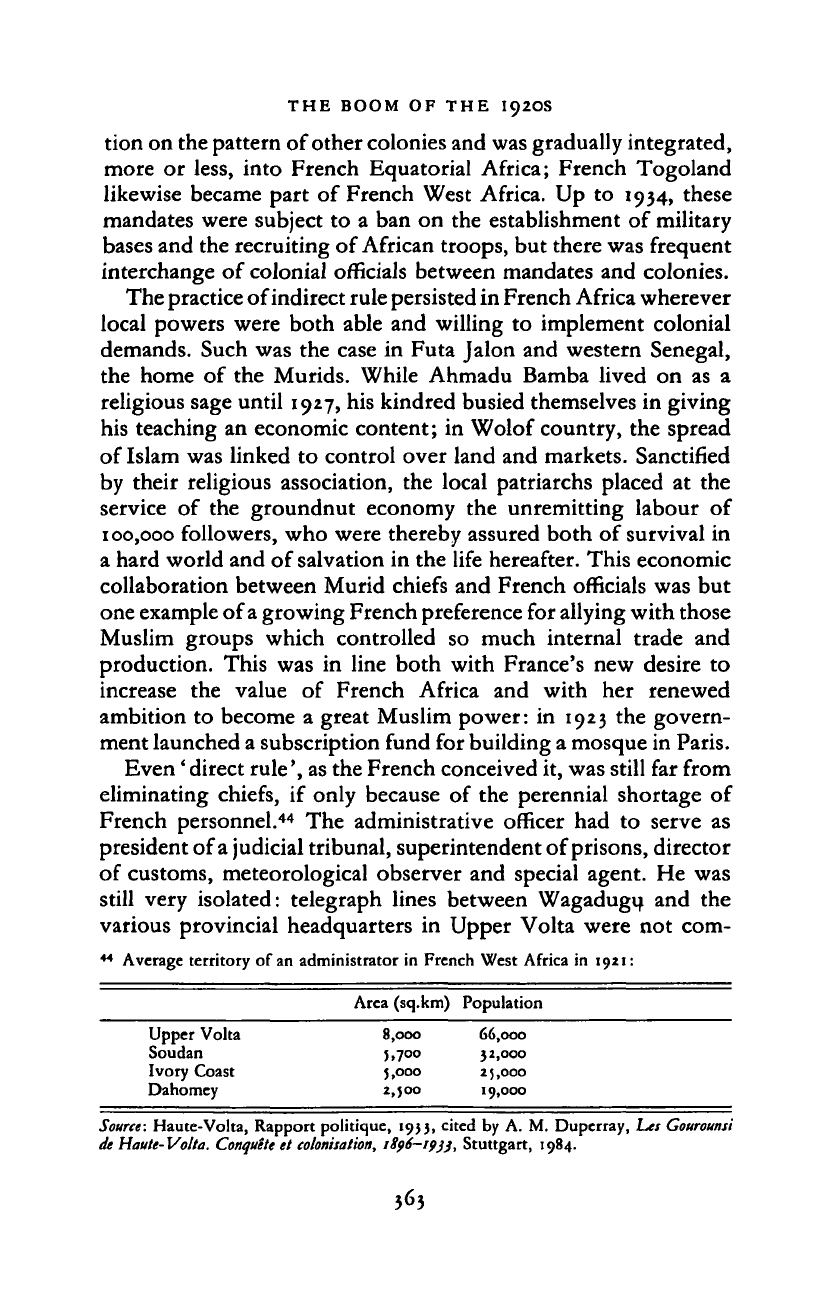

Even' direct rule', as the French conceived it, was still far from

eliminating chiefs, if only because of the perennial shortage of

French personnel.

44

The administrative officer had to serve as

president of a judicial tribunal, superintendent of prisons, director

of customs, meteorological observer and special agent. He was

still very isolated: telegraph lines between Wagadugu and the

various provincial headquarters in Upper Volta were not com-

44

Average territory of an administrator in French West Africa in 19*1:

Area (sq.km) Population

Upper Volta

Soudan

Ivory Coast

Dahomey

8,000

5,700

5,000

2,500

66,000

) 2,000

25,000

19,000

Source: Haute-Volta, Rapport politique, 1933, cited by A. M. Duperray, Let

Gourounsi

de Haute-Volta. Conquite et

colonisation,

1896-if)), Stuttgart, 1984.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

pleted until 1928. The only way to gather information was still

to go on tour, and this was often impossible during the rains. The

support of chiefs thus remained central to colonial policy. True,

their prerogatives were formally delegated from France, following

the Van Vollenhoven circular of

1917,

but the chiefs remained the

only line of communication between the administrator and his

people. At the same time, the canton tended to become merely

an administrative division, while the canton chief himself was

gradually integrated into the public service. He was generally

chosen from among families qualified to rule by custom, but in

1927 the school for the sons of chiefs was reorganised: hence-

forward, it was recruited by competitive examination from among

primary school-leavers related to prominent people. In 1930 a

circular emphasised 'the need, in certain situations, to make a

clean sweep of the traditional apparatus...in order to replace it by

suitably qualified personnel'.

45

The canton chief was always

nominated by the governor, but after 1937 this was done on the

advice of the council of notables for each province: in this way,

a caste of chiefs came into being that was far removed from

pre-colonial traditions. The remuneration which had been advo-

cated in 1917 and approved in 1922 did not become general until

1934.

In 1935 a quasi-retirement pension, with an honorarium,

was introduced; the prerogatives of chiefs were regulated and

their judicial functions curbed to conform to modern notions of

justice. The ambiguous position of the

chief,

as both agent of the

colonial government and spokesman for his people, was exempli-

fied in an experiment with 'district commissions'. These were

intended to be equivalent to the councils which had once advised

African rulers, but while their composition might be fixed by

custom or regulated by the

commandant,

their role was confined

to ratifying official decisions. The logical outcome, by the 1950s,

was for chiefs as a class to be replaced by petty officials who were,

less likely to use archaic privileges to exploit the public.

One of the chiefs main tasks was to supply the growing

demand for labour. Taxation, by now, was generally, if reluctantly,

accepted as a fact of life: but the extraction of cheap labour was

still more vital to the colonial system. In 1920 an agronomist

bluntly remarked: 'For 10,000 francs you can have a house built

45

Cited by F. Zucarclli,' De la chefferie traditionelle au canton: evolution du canton

colonial au Senegal 185 5-1960', Cabiers ditudts afritaines, 1973, 13, no. 50, 213—}8.

364

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

which

is

worth 100,000; you can have dozens

of

kilometres

of

roads made for

a

few hundred francs, and hundreds and thousands

of hectares put under cultivation without paying a sou. The man

who pays the bill says nothing: he is the

native.

'

46

Forced labour,

in the sense of compulsory labour, was forbidden by French law,

but

in

Africa labour which was to

all

intents and purposes ' forced'

was exacted both for public works and for private enterprise. The

most obvious example

was the

prestation,

the

obligation

to

contribute unpaid labour for public services, especially roadworks.

In 1912 the practice was legalised in French West Africa

in

the

form

of

a

'

work-tax' which varied from eight

to

twelve days

a

year;

in

Senegal,

it

was made redeemable

in

cash

in

1921

and

reduced

to

four days

in

1922.

In

French Equatorial Africa,

prestations

were introduced in 1918,

at

first for seven days

a

year

and then, from 1925, for

a

maximum

of

15 days. Food supplies

were provided only for those working more than

a

day's march

(30 km) from their villages: in French West Africa this distance

was reduced

in

1925

to

5 km. Despite their limited duration,

prestations

were most unpopular.

Much labour was needed in areas far removed from the main

clusters of population, especially in French Equatorial Africa. The

answer was

to

recruit men on more or less extended contracts.

Private agencies, such as the Societe du Haut-Ogooue, claimed

a

monopoly within their own territories and recruited many more

workers than they needed themselves. Chiefs

had to

supply

workers

to the

recruiters,

and

they were paid according

to

quantity. In this way, between 1918 and 1925, Governor Lamblin

extended the road network in Ubangi-Shari from 340 km to 4,000

km. Between 1921 and 1932, 127,250 men were recruited to work

far from home

on the

Congo-Ocean railway.

For

this,

the

recruiting campaigns were like police operations

and

created

panic,

for

such recruitment,

at

least until 1928, amounted

to a

death-sentence:

it

was usually the weakest who were seized arid

they then suffered from the failures of regional food supplies and

inadequate health supervision.

47

Labour was also recruited for the

46

H. Cosniet, L'Outst Africainfratifais, ses resources

agricoles,

son organisation iconomique

(Paris, 1921), 142.

47

The official figures were at least 10,200 dead between 1921 and 1928, more than 1,300

in 1929 and 2,600 between 1930 and 1932; probably, ifvictims outside the work-centres

are included, at least 20,000 died.

G.

Sautter, 'Notes sur la construction du chemin

de

fer Congo-Ocean (1921-1934)', Cabiers <T

etudes

africa'mes,

1967,

7,

no. 26, 247-8.

365

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

railways

of

French West Africa, especially the Thies-Kayes line

(for which the three central regions of Upper Volta provided more

than 22,000 men between

1919

and

1927)

48

and the line northwards

through Dahomey, where chiefs in nearby villages arranged rotas

of men

to

work by the hour

or

the task. Furthermore, porterage

was still regularly levied

in the

mid-1920s wherever there was

neither railway

nor

motor-road. Meanwhile conscription

was

applied

to

productive work. The system, called ' labour service

for works

in

the public interest' (SMOTIG) was introduced

in

French West Africa in the early 1920s.

In

Senegal,

in

1928, three

units (just over 2,000 men) were called

up in

this way, two

for

the Thies-Niger railway. The government also handed over some

of these men to the private sector: to the Compagnie des cultures

tropicales

en

Afrique and

the

Societe des plantations

de

Haute

Casamance. By 1940, the daily wage of such conscripts was

at

least

higher than that

of

most workers.

49

The government tried

to

restrain the demands

of

the private

sector.

In

sparsely-populated Gabon, Governor-General Anton-

etti told forestry developers

in

1926 that the existing enterprises

already called

for

more workers than the colony could provide

and ' any new contractor commencing operations will do so at his

own risk and peril'.

50

In French West Africa

a

circular

of

1925

reasserted government prerogatives

in

distributing

the

labour

force,

but in

1930 agricultural

and

industrial enterprises were

authorised

to

apply

to the

local administration

for

help

in

recruiting labour.

51

The regulation of labour contracts in general

began

in

French Equatorial Africa

in

1922 and

in

French West

Africa in 1925. Its impact was limited, however, both by the vast

number

of

casual workers who,

in the

name

of

'freedom

of

employment' were

not

protected

by any

control,

and

because

labour contracts (varying from

six

months

to

two years) were

riddled with irregularities;

a

specialised labour inspectorate was

not established until the 1930s.

A further method

of

boosting production

was

compulsory

<

8

The current workforce was about 7,000 labourers

at a

time, 4,000

of

them being

'volunteers' from Upper Volta (Duperray,

LAS

Gourounsi).

49

0.75 francs plus daily bonus

of

0.50 francs, compared with wages

of

the order

of

1

franc a day. Archives nationales du Senegal, 28/K 105, no. 39. See B. Fall,' Le Travail

force

au

Senegal, 1900-1946' (Memoire de Maitrise, University

of

Dakar, 1977).

s0

Note

in

the journal

officielde

PAEF, 1 June 1926, repeated 1 December 1927.

sl

Journal officiel de

FAOF, 21 August 1930.

Cf.

Archives nationales du Senegal, 19/K

60.

366

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

cultivation. During the First World War, Africans who refused

to cultivate were liable

to be

regarded

in the

same light

as

tax-defaulters and

in

1917 officials

in

French West Africa were

urged to consider all means of expanding cultivation.

52

After the

war there were continued efforts

in

this direction, based

on

officially created village-centres, as part of a systematic policy of

'regrouping', especially in French Equatorial Africa.

In

Ubangi-

Shari, the administrator Felix Eboue followed Belgian practice

and from 1925 gave four companies sole rights to buy cotton in

vast areas

of

compulsory production, which naturally became

extremely unpopular. In French West Africa — in Upper Volta,

Soudan and Niger — average annual exports of cotton rose from

189 tons

in

1910—14

to

3,500 tons

in

1925—9. The compulsion

which achieved these modest results was, along with taxation, the

main reason why between 80,000 and 100,000 Mossi fled

in

the

course of

a

decade to the Ivory Coast and the Gold Coast;

it

also

drove Yoruba

in

Dahomey

to

flee

to

Nigeria (which created

friction between Britain and France). Chiefs, of

course,

had much

less reason than their subjects

to

fear compulsory cultivation;

indeed, once prestatory workers had discharged their obligations

to government, they were liable to be put to work on their chiefs'

fields.

This was specially common in Cameroun, where the richest

chiefs also employed women

to

expand areas

of

commercial

cultivation. When Zogo Fouda Ngono, chief of the Beti, died in

1939,

he left behind him 583 widows, only some

of

whom had

performed other than agricultural functions.

Social investments

In 1923 Albert Sarraut, the minister of colonies, articulated ideas

which had been circulating since the war, and voiced the qualms

of conscience felt

in

metropolitan France

at the

prospect

of a

general collapse

in

Africa following

the

alarming decline

in

population. ' Our native policy,' he said, ' must be to preserve the

African

people.

'

53

Thence arose the need, along with

a

far-reaching

programme of metropolitan investment, for health and education

services to improve African welfare and thus productivity, while

also generating a local elite of

technicians.

But though ideas were

52

Circular cited

in

Fall, 'Travail force'.

51

A.

Sarraut,

La

Mist en

valeur

det colonies franfaises (Paris, 1923), 675.

367

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

beginning to advance, their realisation had to wait upon

reconstruction in France

itself.

The 'Sarraut Plan' remained a

dead letter for want of

money.

Loans which were then advanced

had actually been authorised before the war, most notably the

171m francs for the Congo—Ocean railway (supplemented by

credits of 300m francs in 1924). Even so, French Equatorial Africa

was unable throughout our period to pay interest on its public

debt; between 1914 and 1929 its budget received from France an

average annual subsidy of 3 m francs (as much in real terms as

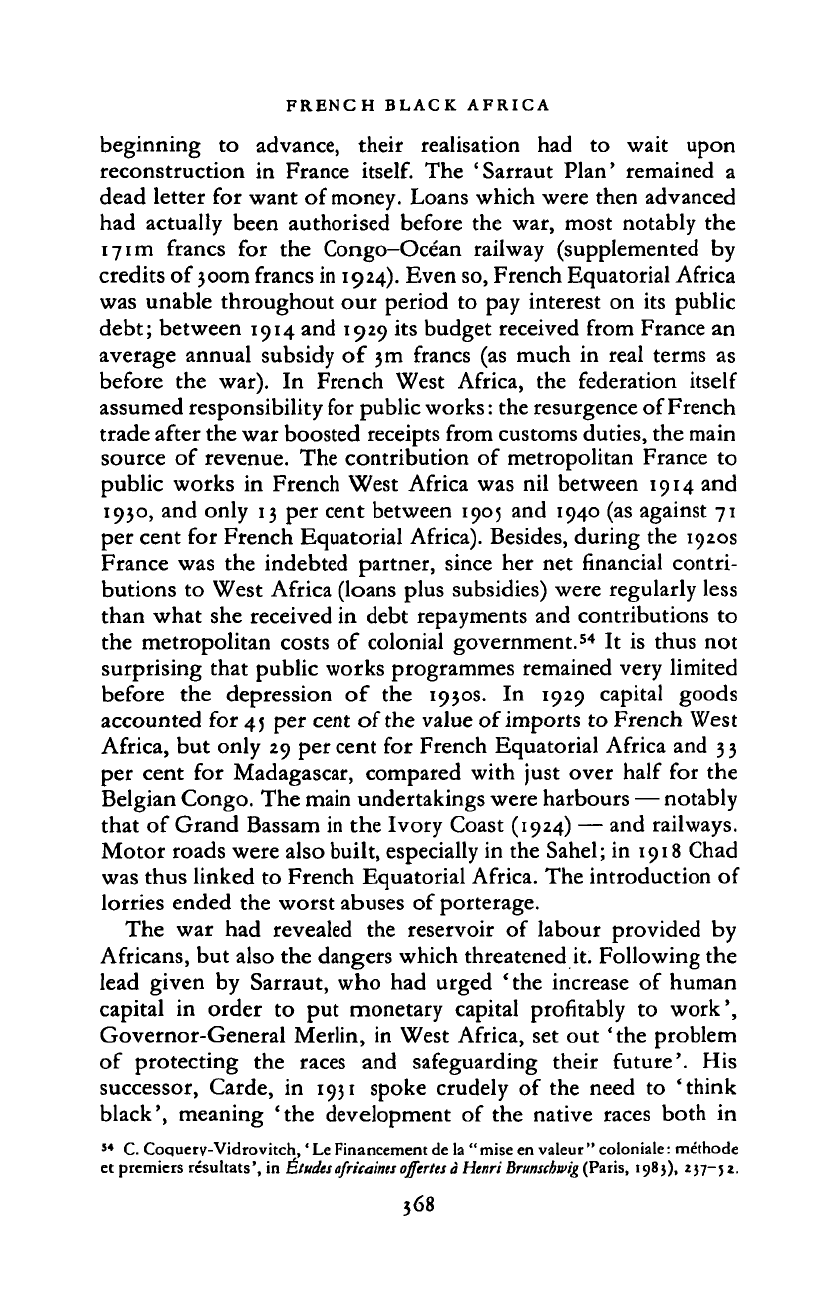

before the war). In French West Africa, the federation itself

assumed responsibility for public works: the resurgence of French

trade after the war boosted receipts from customs duties, the main

source of revenue. The contribution of metropolitan France to

public works in French West Africa was nil between 1914 and

1930,

and only 13 per cent between 1905 and 1940 (as against 71

per cent for French Equatorial Africa). Besides, during the 1920s

France was the indebted partner, since her net financial contri-

butions to West Africa (loans plus subsidies) were regularly less

than what she received in debt repayments and contributions to

the metropolitan costs of colonial government.

54

It is thus not

surprising that public works programmes remained very limited

before the depression of the 1930s. In 1929 capital goods

accounted for 45 per cent of the value of imports to French West

Africa, but only 29 per cent for French Equatorial Africa and

3 3

per cent for Madagascar, compared with just over half for the

Belgian Congo. The main undertakings were harbours — notably

that of Grand Bassam in the Ivory Coast (1924) — and railways.

Motor roads were also built, especially in the Sahel; in 1918 Chad

was thus linked to French Equatorial Africa. The introduction of

lorries ended the worst abuses of porterage.

The war had revealed the reservoir of labour provided by

Africans, but also the dangers which threatened it. Following the

lead given by Sarraut, who had urged 'the increase of human

capital in order to put monetary capital profitably to work',

Governor-General Merlin, in West Africa, set out 'the problem

of protecting the races and safeguarding their future'. His

successor, Carde, in 1931 spoke crudely of the need to 'think

black', meaning 'the development of the native races both in

54

C. Coquetv-Vidrovitch,' Le Financement de la "mise en valeur

"

coloniale: methode

et premiers resultats', in Etudesafricaintsoffertesa Henri

Brunschwig

(Paris, 1983), 257-52.

368

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

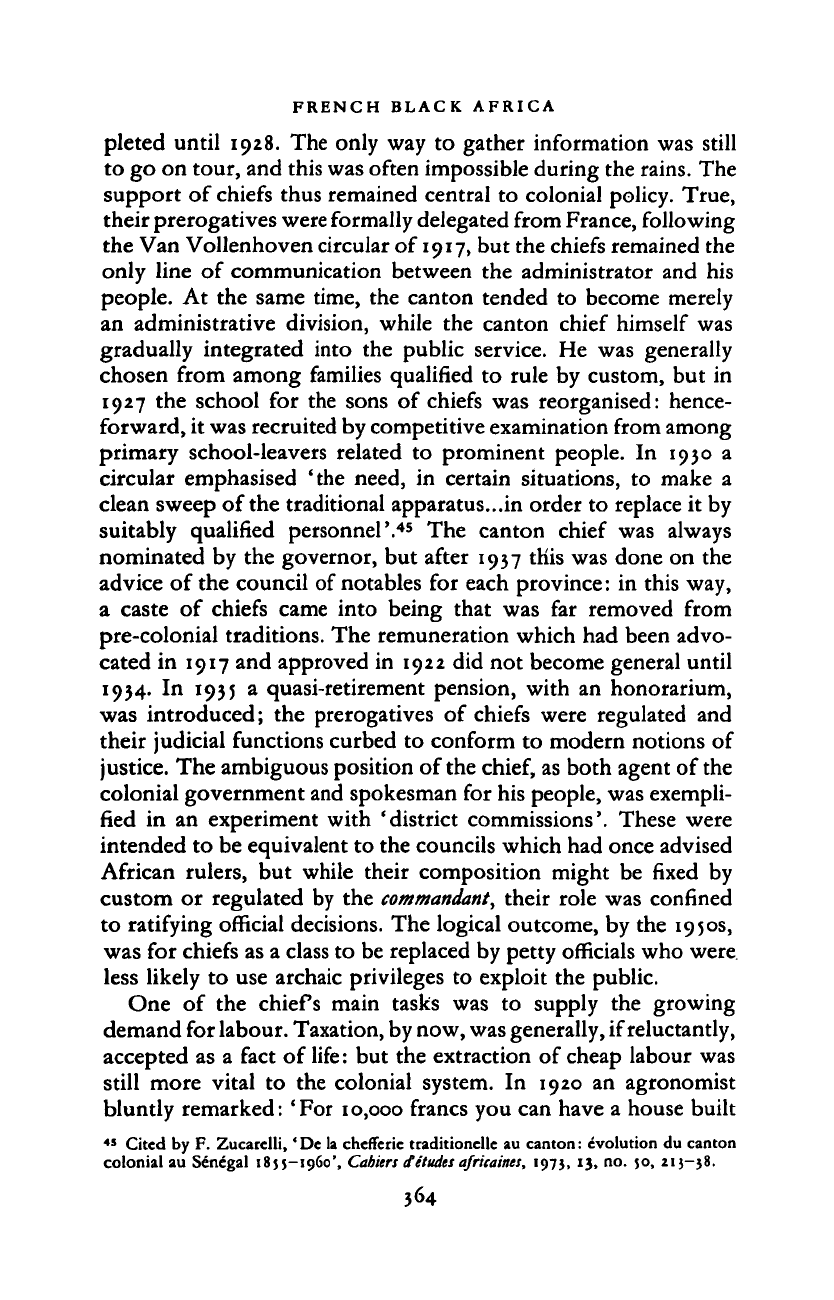

10%

-

THE BOOM OF THE I92OS

50%

-

40%

-

30%

20%

-

10%

-

1900 05 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

French West Africa

1900 05 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

French Equatorial Africa

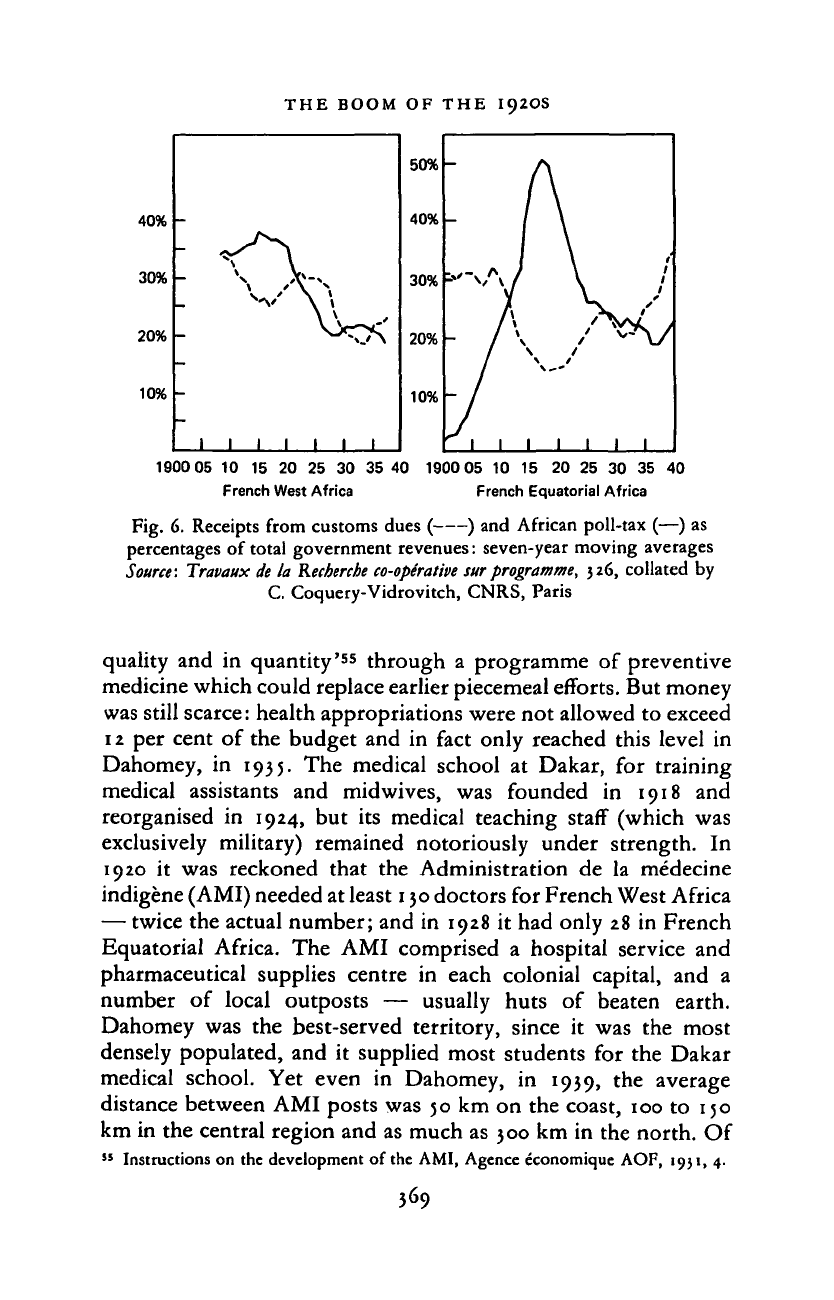

Fig. 6. Receipts from customs dues ( ) and African poll-tax (—) as

percentages of total government revenues: seven-year moving averages

Source: Travaux de la

Recherche co-operative

sur programme, 326, collated by

C. Coquery-Vidrovitch, CNRS, Paris

quality and in quantity'

55

through a programme of preventive

medicine which could replace earlier piecemeal efforts. But money

was still scarce: health appropriations were not allowed to exceed

12 per cent of the budget and in fact only reached this level in

Dahomey, in 1935. The medical school at Dakar, for training

medical assistants and midwives, was founded in 1918 and

reorganised in 1924, but its medical teaching staff (which was

exclusively military) remained notoriously under strength. In

1920 it was reckoned that the Administration de la medecine

indigene (AMI) needed at least

130

doctors for French West Africa

— twice the actual number; and in 1928 it had only 28 in French

Equatorial Africa. The AMI comprised a hospital service and

pharmaceutical supplies centre in each colonial capital, and a

number of local outposts — usually huts of beaten earth.

Dahomey was the best-served territory, since it was the most

densely populated, and it supplied most students for the Dakar

medical school. Yet even in Dahomey, in 1939, the average

distance between AMI posts was 50 km on the coast, 100 to 150

km in the central region and as much as 300 km in the north. Of

55

Instructions on the development of the AMI, Agence economique AOF, 1951, 4.

369

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

the 51 mid wives

in

the colony, ten had

to

serve 45 per cent

of

its population and over 80 per cent of its area.

Against the most serious epidemics there was still very little

defence. Typhus was brought by caravans from Mossi country to

the middle Niger, where

it

raged endemically between 1921 and

1929.

The major endemic diseases were frequently opposed

by

such traditional measures as declaring 'prohibited zones' (as

in

northern Dahomey when invaded by sleeping-sickness), abandon-

ing contaminated villages, isolating the sick and cremating the

corpses

of

lepers. However,

by

1930 about

a

quarter

of the

population

of

French West Africa had been vaccinated against

smallpox, and

in

1936 a regular mobile vaccination service was

introduced. In 1934 yellow fever vaccination was introduced but

by 1940

it

had reached only

1

per cent of the population, almost

all

in

towns. Medical control over wage-earners was improved,

especially on railways, and instruction

in

hygiene was imparted

to schoolchildren, though unfortunately few were girls. The first

textbooks expressed themselves with frightening candour:' If you

die,

who will climb

the

palm-tree, who will make oil? The

government needs tax.

If

your children don't survive, who will

pay it? That is why the government spends money on bringing

doctors and hiring the heifers needed to provide vaccine. '

s6

The most impressive efforts were those initiated by Jamot

to

combat sleeping-sickness. Jamot first encountered the disease as

a military doctor during the Cameroun campaign; he then became

director of the Pasteur Institute in Brazzaville

57

and made his first

prophylactic experiments

in

1917 while examining 100,000 cases

in Ubangi.

In

1921 he was transferred to Cameroun and in 1926

set up

a

permanent mission there. His method was based on the

systematic investigation and recording of cases by mobile clinics

and

on

treatment

by

compulsory mass injections

of

atoxyl.

In

French Equatorial Africa the struggle was redirected along similar

lines between 1928 and 1935, and the disease began to recede in

1938.

Such methods were not imported into French West Africa

until

the

1930s, just when

the

spread

of

endemic disease was

accelerated, especially

in

the Ivory Coast,

by

extensive forest-

56

Docteur Spire, Pour vivre vieux en AJrique (Porto-Novo, Dahomey, 1921).

57

Founded

in

1909 following

the

medical mission

of

Drs Martin, Leboeuf and

Roubaud

in

1906—8;

cf.

Rapport de

la

mission

a"etudes

de la maladie du sommeil au Congo

franfais, if

06—1908

(Paris, 1909), 721.

37°

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008