Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

clearance and

the

consequent displacement

of

people.

In 1931

Jamot set up

a

preventive service

in

Wagadugu, which

in

1932

became part of the AMI, was revived as a mobile service in 1934

and became a specialised service in 1939. By then, 143,000 victims

of sleeping-sickness had been tracked down and after 1941 only

the central region

of the

lower Ivory Coast experienced

any

recrudescence

of

the disease.

Educational plans

in

1924 stressed the need

to

form

an

elite

loyal

to the

colonial cause. Public instruction

in

French West

Africa tended increasingly to imitate metropolitan French models.

An international congress

on

education

in

1931 concluded that

the French policy

of

assimilation went

too far, and in

1935

a

British visitor to the William Ponty School, near Dakar, remarked,

'They are French

in

everything but the colour

of

their skins.

>s8

This trend ran counter

to

the educational aims

of

missionaries,

who preferred to make use of vernacular languages, though from

1922 these were officially banned

in all

schools.

59

Government

provision for secular schools expanded rapidly after the war. By

1924 there were 29,000 children

in

the government schools

of

French West Africa: more than twice as many as

in

1910. There

were also

5,700

in

mission schools; these could

now

receive

subsidies if they broadly conformed to patterns of state education,

but throughout the 1920s and 1930s they accounted for

at

most

one-sixth

of

all schoolchildren

in

French West Africa. Besides,

most people remained beyond the reach

of

any school: even

in

Dahomey

it

is unlikely that more than 10 per cent

of

school-age

children went to school in 1939. Throughout French West Africa

in 1938 there were less than 70,000 schoolchildren out

of

some

12 million people;

in

impoverished French Equatorial Africa

there were scarcely 20,000 out

of

five million.

This narrow base largely comprised village

or

district schools

where, owing

to

staff shortages,

the

teacher

was

often

an

unqualified African, perhaps an ex-interpreter or a literate soldier,

who was left to his own resources and was seldom visited by an

inspector.

60

After four years, the most promising pupils might

58

W. B.

Mumford,

in W. B.

Mumford and

G. St J.

Orde Browne, Africans learn

to

be

French

(London, n.d. [1936]), 47.

19

In the Ivory Coast, the catechism was translated into Nzima

in

1911, Ebrie in 1923,

Dida

in

1932 and Atie (Akye)

in

1934.

60

The school at Kandy, in northern Dahomey, was founded in 1910 but not inspected

until 1919.

371

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

gain entry to a senior primary school: in 1935 there were eight

such schools, with 1,000 places, in French West Africa. From

these, pupils might proceed to schools of marine engineering or

midwifery in Dakar, or to a teacher-training college: by the late

1930s there was one near Abidjan and one near Bamako as well

as the William Ponty School, which also prepared Africans for

entry to a medical school in Dakar (founded in 1918) and a

veterinary school in Bamako. Secondary education on the French

pattern was provided, mainly though not exclusively for whites,

by schools at St Louis and Dakar. The first taught up to university

entrance standard from 1920; the second, only from 1940. A

special effort to provide state-supported education was made in

the mandated territories, where the rapid diffusion of the French

language was needed to counter the considerable achievements of

German mission teaching. In Cameroun, by 1926, ten regional

schools with 1,850 pupils led to the high school at Yaounde, which

prepared Africans for posts in government and teaching.

Vocational training was supposed to be available in each capital,

and it was sponsored by the railway administration, but in practice

little was provided, except on the job: the need for staff was so

great that it was enough to be literate to be sure of finding work.

On the eve of the Second World War, education was still the

privilege of a very small minority — small enough to be absorbed

without risk by the colonial system while contributing to the cult

of the diploma, the guarantee of social advancement.

First results

However restricted all these efforts, their first results were soon

apparent. While population statistics for the period are very

unreliable, it is clear that from 1925 and especially in the 1930s

there was a reversal of earlier demographic decline. Dahomey was

thought to number 840,000 people in 1920, 963,000 in 1925, one

million in 1930 and 1.3 million in 1935. Cameroun was thought

to number 1.9mm 1926, 2.2mm 1931 and 2.5mm 1937. In French

Equatorial Africa, an upward trend seems to have begun just after

the depression of the 1930s.

Colonial trade was boosted by French prosperity in the 1920s.

Already, trading firms had profited during the war from inflated

prices and the government's bulk purchases of so-called strategic

372

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

supplies (oil-products

and

rubber). After

the

brief slump

of

1921-2,

when the price

of

palm-oil fell from 4,200

to

1,300 francs

per ton, the upward trend was resumed and maintained until 1930,

encouraged

by the

massive inflation

of

the franc

up

to

1926

(the

Poincare franc, introduced

in

1928,

was

worth

not

more than

one-fifth

of

the gold franc

of

1913). With

new

opportunities

for

profit from speculation, there was

a

proliferation of colonial firms,

especially in commerce. On the eve of the depression, black Africa

had

107

companies which were quoted

on

the

Bourse

in

Paris

(compared with

22

founded between 1900

and

1914), including

29

new

commercial ventures,

48

plantation companies,

21 in

forestry,

11 in

mining,

11 in

banking

and

real estate,

and 7

transport companies. Between 1924

and

1930

the

CFAO made

annual profits

of

25

to

30 per cent,

as in

pre-war days.

The

share

capital of SCO A increased almost tenfold from 1920 to 1928 (from

18m

to

157m

francs);

its

value quadrupled

in

real terms.

Diversification

was

undertaken: SCOA

and

CFAO enlarged

on

their traditional bases

of

groundnuts

in

Senegal,

the

Ivory Coast

and Guinea, and moved into Gold Coast cocoa and Nigerian palm

produce and tin. By i93oCFAOhad

191

branches and SCOA 145.

Various factors facilitated diversification: machines were applied

to

the

processing

of

primary products

and

firms were absorbed

or became subsidiaries.

In

the

hinterland,

a

feeder network

of

freight transport

was

developed

by

Levantines

who

had

first

arrived early

in the

century

but

mostly came when Syria

and

Lebanon became French mandates. They readily settled

in the

interior, learned local languages

and

lent money

on

patriarchal

lines,

at

annual rates

of

interest

of

up

to

50

per

cent.

The principal export continued

to be

groundnuts, which

in

1938 still contributed almost half the total value

of

exports from

French West Africa.

61

The

completion

of the

Thies-Kayes

railway

in

1923 caused

an

agricultural revolution

in

Senegal

by

opening

up

Sine-Saloum. Kaolack became

the

chief outlet

for

exports, which doubled between 1914

and

1930.

In

Guinea

the

banana plantations

of

Europeans began

to

mature, yielding 6,000

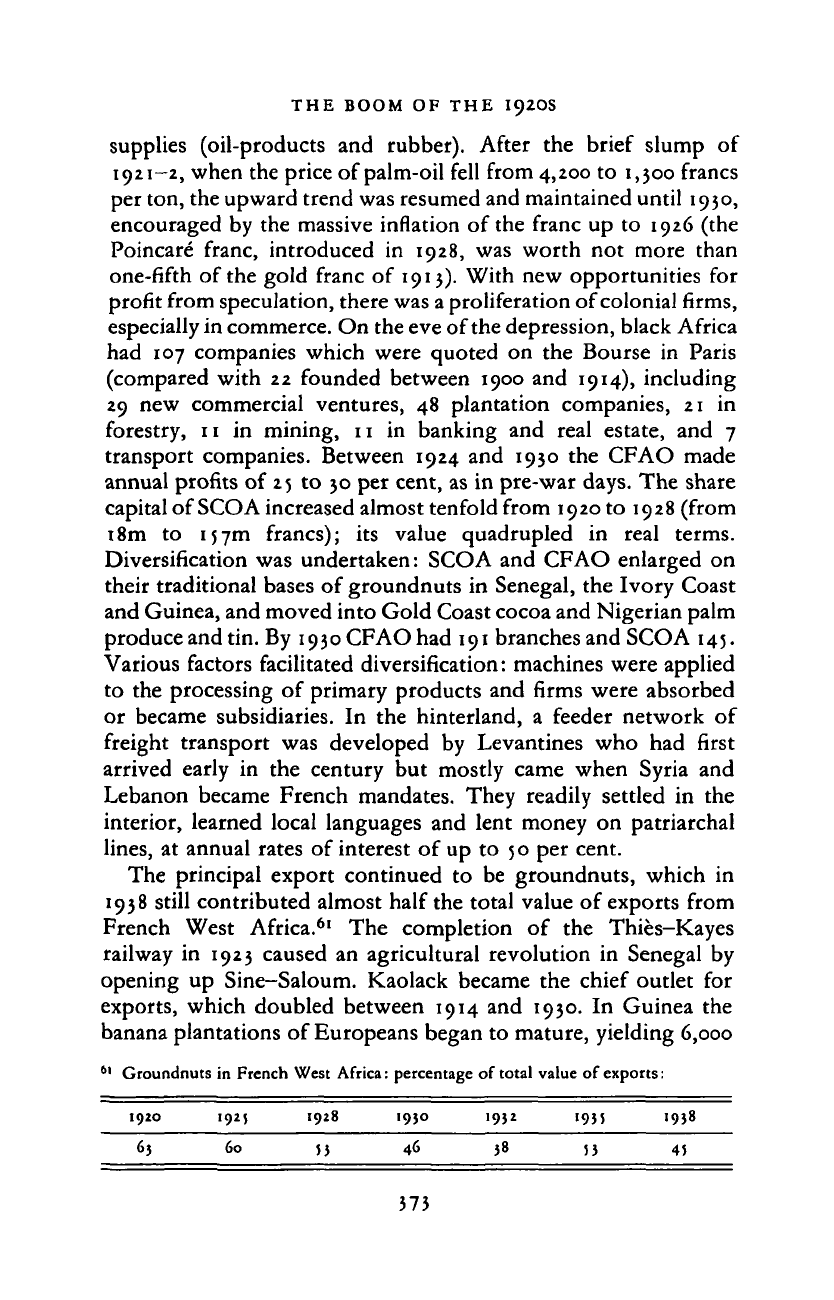

61

Groundnuts

1920

63

in French

1925

60

West Africa:

1928

5)

percentage

1930

46

of total

1932

value

of

exports

«935

53

1938

45

375

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

200,000

150,000

100,000

50,000

10,000

-

Imports

Exports

i,

•,, i,

r

1

11111111111

\

•4

1111

/

i

•

111

/

/

1905 1910 1915 1920 1925 1930 1935 1939

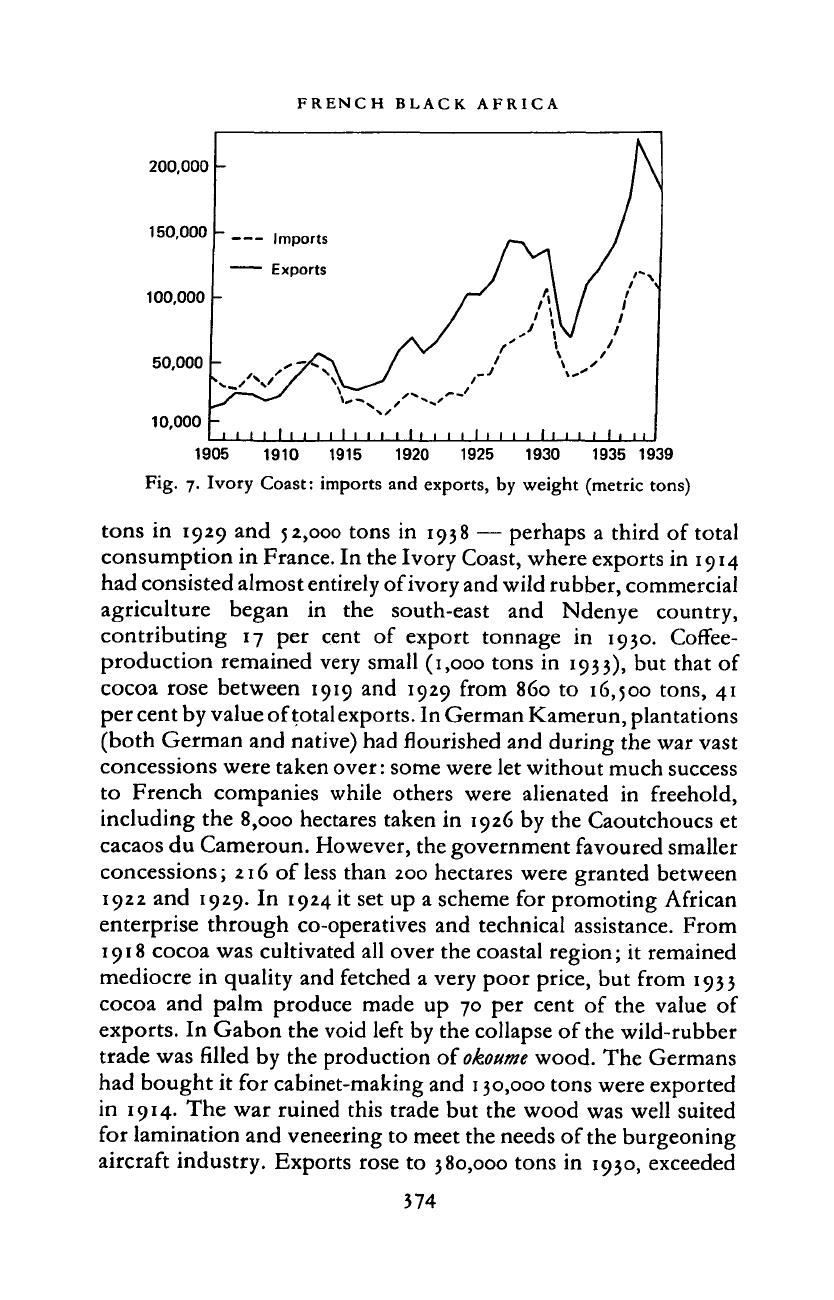

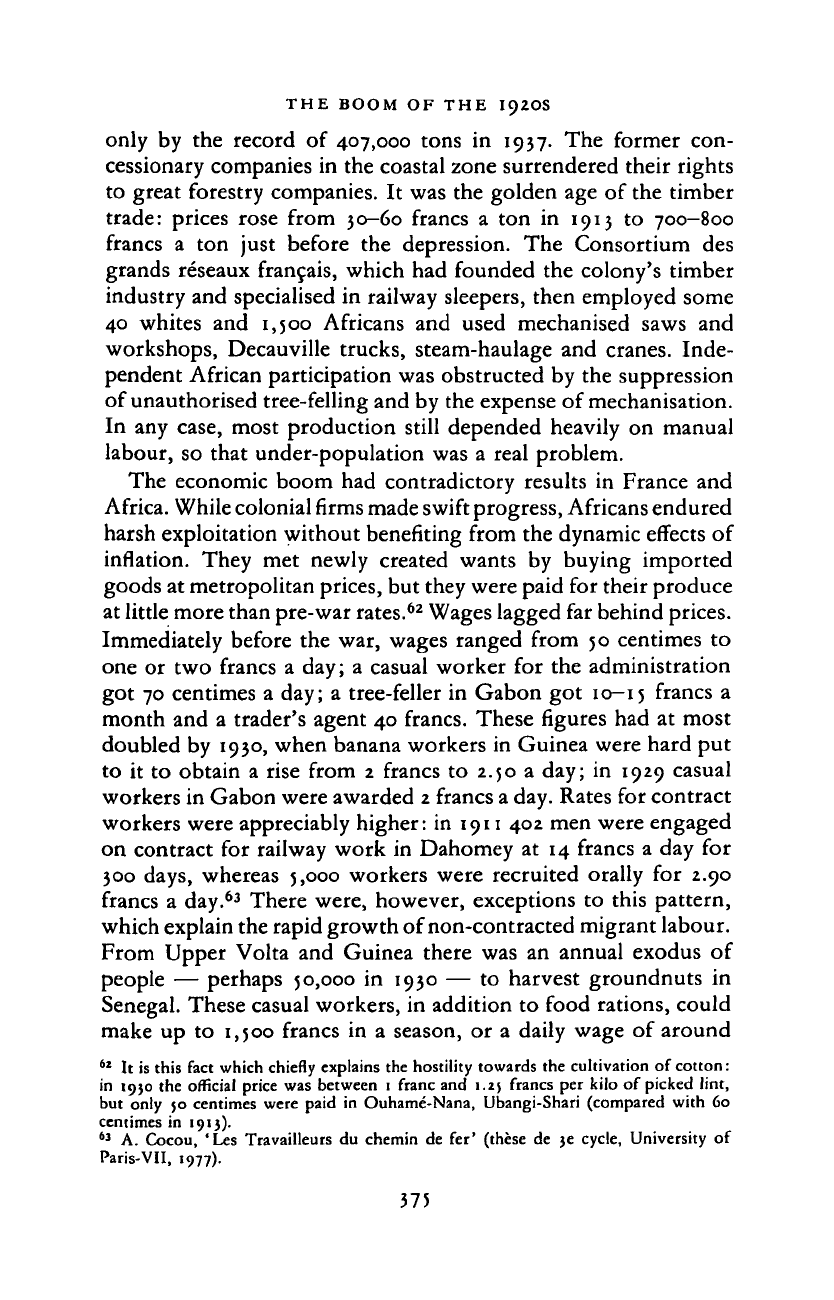

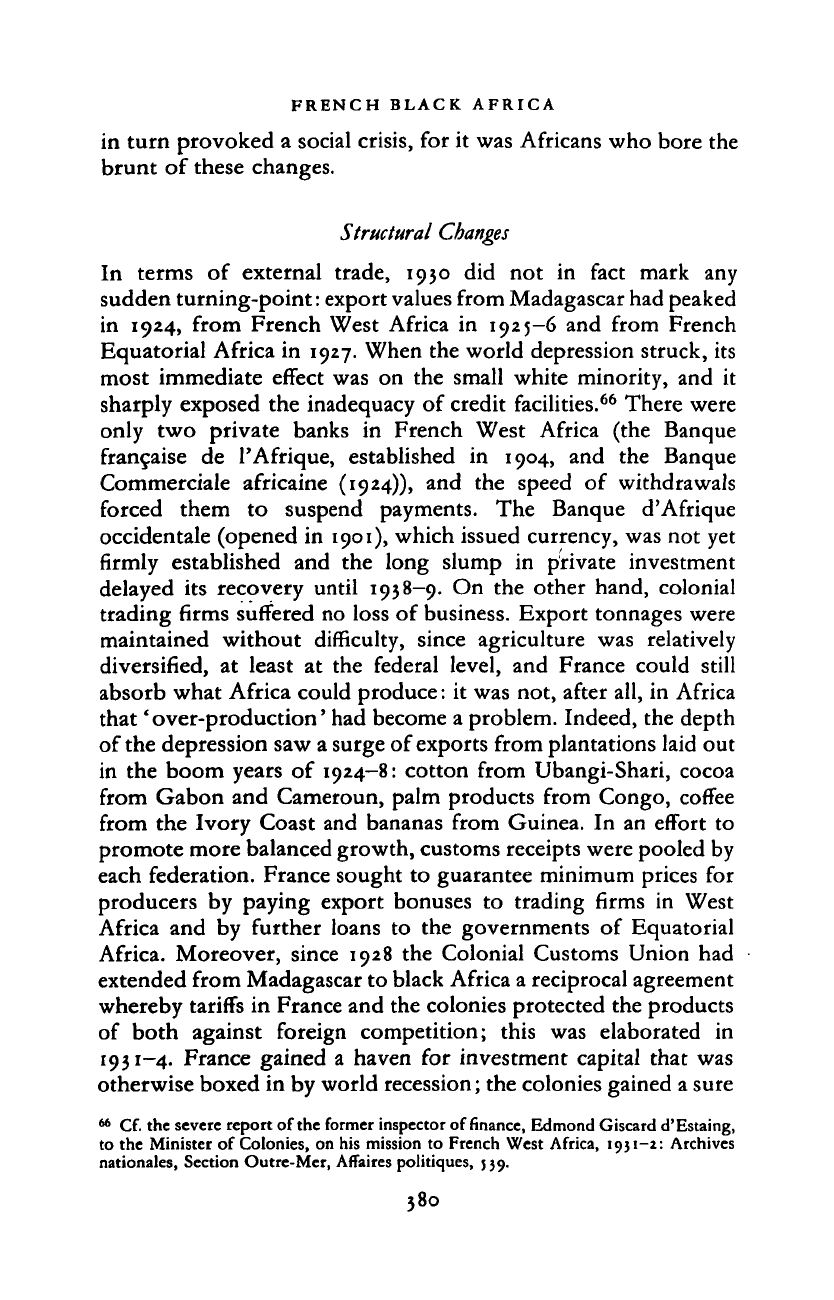

Fig. 7. Ivory Coast: imports and exports, by weight (metric tons)

tons

in

1929

and

52,000 tons

in

1938

—

perhaps

a

third

of

total

consumption

in

France.

In

the Ivory Coast, where exports

in

1914

had consisted almost entirely of ivory and wild rubber, commercial

agriculture began

in the

south-east

and

Ndenye country,

contributing

17 per

cent

of

export tonnage

in 1930.

CorTee-

production remained very small (1,000 tons

in

1933),

but

that

of

cocoa rose between 1919

and

1929 from

860 to

16,500 tons,

41

per cent by value of total exports. In German Kamerun, plantations

(both German and native) had flourished and during the war vast

concessions were taken over: some were let without much success

to French companies while others were alienated

in

freehold,

including

the

8,000

hectares taken

in

1926

by

the Caoutchoucs

et

cacaos

du

Cameroun. However, the government favoured smaller

concessions; 216

of

less than 200 hectares were granted between

1922

and

1929.

In

1924

it set up a

scheme

for

promoting African

enterprise through co-operatives

and

technical assistance. From

1918 cocoa was cultivated all over the coastal region;

it

remained

mediocre

in

quality and fetched

a

very poor price,

but

from 1933

cocoa

and

palm produce made

up 70 per

cent

of the

value

of

exports.

In

Gabon the void left by the collapse

of

the wild-rubber

trade was filled

by

the production

of

okoume

wood. The Germans

had bought

it for

cabinet-making and 130,000 tons were exported

in 1914.

The war

ruined this trade

but the

wood was well suited

for lamination and veneering

to

meet the needs of the burgeoning

aircraft industry. Exports rose

to

380,000 tons

in

1930, exceeded

374

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

only by the record of 407,000 tons

in

1937. The former con-

cessionary companies in the coastal zone surrendered their rights

to great forestry companies. It was the golden age of the timber

trade: prices rose from 30-60 francs

a

ton in 1913 to 700-800

francs

a

ton just before the depression. The Consortium des

grands reseaux francais, which had founded the colony's timber

industry and specialised in railway sleepers, then employed some

40 whites and 1,500 Africans and used mechanised saws and

workshops, Decauville trucks, steam-haulage and cranes. Inde-

pendent African participation was obstructed by the suppression

of unauthorised tree-felling and by the expense of mechanisation.

In any case, most production still depended heavily on manual

labour, so that under-population was a real problem.

The economic boom had contradictory results in France and

Africa. While colonial

firms

made swift

progress,

Africans endured

harsh exploitation without benefiting from the dynamic effects of

inflation. They met newly created wants by buying imported

goods at metropolitan prices, but they were paid for their produce

at little more than pre-war rates.

62

Wages lagged far behind prices.

Immediately before the war, wages ranged from 50 centimes to

one or two francs a day; a casual worker for the administration

got 70 centimes a day; a tree-feller in Gabon got 10—15 francs a

month and a trader's agent 40 francs. These figures had at most

doubled by 1930, when banana workers in Guinea were hard put

to it to obtain a rise from 2 francs to 2.50 a day; in 1929 casual

workers in Gabon were awarded

2

francs a day. Rates for contract

workers were appreciably higher: in 1911 402 men were engaged

on contract for railway work in Dahomey at 14 francs a day for

300 days, whereas

5,000

workers were recruited orally for 2.90

francs a day.

63

There were, however, exceptions to this pattern,

which explain the rapid growth of non-contracted migrant labour.

From Upper Volta and Guinea there was an annual exodus of

people — perhaps 50,000 in 1930 — to harvest groundnuts in

Senegal. These casual workers, in addition to food rations, could

make up to 1,500 francs in a season, or a daily wage of around

62

It

is this fact which chiefly explains the hostility towards the cultivation of cotton:

in 1930 the official price was between

i

franc and 1.2$ francs per kilo of picked lint,

but only $0 centimes were paid

in

Ouhame-Nana, Ubangi-Shari (compared with

60

centimes

in

1913).

63

A.

Cocou,

'Les Travailleurs du chemin

de

fer' (these

de 3e

cycle,

University

of

Paris-VH,

1977).

375

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

12 francs.

64

Tax-levels,

by

contrast, showed no such variations:

everywhere they kept pace with inflation. From 1914 to 1929, the

taxes paid by Africans rose from 26.6m francs to 175m in French

West Africa, from 22m

to

127m

in

Madagascar and from 4.4m

to

30.5

m in French Equatorial Africa. Even if allowance is made

for more efficient collection, the annual burden

of

tax rose from

1-5 francs before

the war to 15-25

francs

in

1929-30

and

sometimes even 50-75 francs

in

the most prosperous zones, such

as Gabon, southern Dahomey and Senegal.

It is usually held that

it

was the need

to

pay tax in cash which

obliged Africans

to

work

on the

land.

The

reality

is

more

complex. Initially compulsion undoubtedly played

a

part,

especially

in

French Equatorial Africa, where wages

on

conces-

sions were

so

low

as to

offer no incentive

to

take part willingly

in the cash economy. On the other hand, statistics

for

the most

commercialised activity

of the

period, groundnut production,

show that between

1921

and 1929 only

10

per cent of a cultivator's

working time was needed for paying fiscal dues.

65

The extension

of groundnut cultivation was,

by and

large, achieved without

resort

to

force. One possible stimulus might seem

to

have been

a change in consumer habits, to judge from the net ratio between

the volume

of

exports and that

of

imports

of

consumer goods,

but this chiefly related

to

town-dwellers.

In

the bush, rice from

Indo-China remained a luxury, and the farmer in the Sahel could,

if pressed, meet his own clothing needs with strips of locally-made

cotton cloth. Over much

of

French West Africa

the

most

widespread stimulus

to

cash-crop cultivation was indebtedness,

aggravated

by

inflation. Recurrent food shortages

in

Senegal

impelled groundnut cultivators either to consume supplies of seed

and replace them just when prices were highest or else

to

obtain

food by mortgaging part of the next harvest.

In

1905-6 there was

a great famine

in

Sine-Saloum and the government lent farmers

seed and foodstuffs, repayable

in

kind

at

5 per cent interest. The

success

of

this scheme prompted the institution

in

French West

Africa of provident societies to build up food reserves, sink wells,

and popularise investment

in

commercial agriculture. Several

64

L.

Aujas,

'La

Region

du

Sine-Saloum', Bulletin

du

Comite historiqut

et

scientifique de

FAOF', 1929, 1/2,

94-1

jz, cited by M. Mbodj, 'Un exemple d'economie coloniale, Le

Sine-Saloum' (these de 3e cycle, University

of

Paris-VII, 1978).

'*

Ibid.

376

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE BOOM OF THE 1920S

were formed in parts of Senegal and Guinea, but in general they

attracted limited support,

and in

1915 membership was made

compulsory within any province where

a

society existed. So

far

from being a tool for local self-help, the provident society tended

to become another arm of government: from

1923

each

commandant

had full powers over the local society's budget. Furthermore, the

societies lent

at

high interest rates:

30 per

cent soon became

normal. And

if

crop failure,

or

the fear of it, sucked the farmer

into

a

cycle

of

debt, inflation could make

it a

vicious spiral:

as

the purchasing power of his franc declined, he needed more and

more money to meet not only his own material wants but social

obligations once discharged by gifts

in

kind — whether slaves,

animals, gold-dust

or

cloth. All too often the farmer could only

settle his debts by allowing an agent, often Lebanese, to dispose

of his harvest.

New centres

of

resistance

In 1923 there were major disturbances at Porto-Novo, Dahomey.

Popular discontents briefly combined with those

of

the young

educated

elite.

Among the latter, the foremost critic of government

was Louis Hunkarin. The son of ex-King Toffa's blacksmith, he

had left high school in Dakar in 1906 and after a spell of teaching

became a journalist, working at first alongside Blaise Diagne. As

an anti-colonial radical, Hunkarin spent as much time in Paris as

in Dakar or Porto-Novo and was in and out of

gaol.

In

1917 the

first African newspaper appeared

in

Dahomey, clandestine and

hand-written: the

Recadere de

Behantyn.

Then came the slump

of

1921-2;

the government tried

to

make

up for

loss

of

customs

revenue

by

increasing

the

poll-tax and trading-licence

fee

and

imposing

a tax on

European-style houses.

In

February

1923

protest was instigated by

evolue's'm

the Franco-Muslim Committee,

supported by the local section of the League for the Rights of Man

and by King Toffa's dynastic opponents. People

in

Porto-Novo

refused to pay the increased taxes, demonstrated in the streets and

shouted down

a

delegation

of

canton chiefs. Workers

in the

private sector and

at

the port

of

Cotonou went

on

strike. The

government responded fiercely:

it

declared

a

state

of

siege,

imposed a collective fine of 360,000 francs and exiled the activists

(Hunkarin spent the next ten years in Mauritania).

377

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

In 1925 there were strikes on the Dakar—St Louis railway and

among Bambara building the Thies—Kayes line; the latter at least

forced the government to listen to their demands, for fellow

Bambara soldiers refused to march against them. But for most of

the decade, blacks from French West Africa voiced their protest

chiefly in France. In 1924 a Dahomeyan lawyer, Kodjo Tovalou-

Houenou, founded in Paris the' Universal League for the Defence

of the Black Race': its journal,

Continents,

was attacked by Blaise

Diagne, who since 1914 had been a deputy for Senegal. From the

early 1920s the French Communist Party sought to reach African

ex-soldiers and workers in France through the Intercolonial

Union; one of its most active members was Lamine Senghor, an

ex-soldier who had returned to France in 1922. It so happened

that the best students from the William Ponty School were now

sent to Aix-en-Provence to prepare for their diploma examina-

tions.

Thus in 1926 Senghor was able to enlist the help of young

African communist students in founding the Committee (from

1928 the League) for the Defence of the Negro Race. The

problems of these students were sympathetically described in the

Senegalese press by Lamine Gueye, a lawyer who served as mayor

of St Louis in 1925-7. Otherwise, their movement had little

impact in Senegal, but it was in touch with nearly all the militant

Africans who passed through Paris.

In 1929 a section of the League was formed in Cameroun by

Victor Ganty, originally from Guyana. Ganty had tried to found

a spiritualist church in Cameroun, but he now contrived to

associate modernist protests with the traditional anti-colonial

sentiments of the Douala notables. He succeeded Richard Manga

Bell as head of the France-Cameroun Association and in 1931

presented to the League of Nations a petition for the ' defence of

black citizens of Cameroun'. African dissidents in Paris may also

have exerted some influence on Andre Matswa, a veteran of the

Rif war in 1925, though the 'Friends of the Original Inhabitants

of French Equatorial Africa', which he founded in Paris in 1926,

aspired only to the 'mirage of citizenship' as in Senegal. Matswa

returned to Brazzaville, where his movement had remarkable

success among the Kongo; it then spread to Libreville and

Bangui. By 1929 it had 13,000 members in Bangui and the scale

of demonstrations by workers there alarmed the government,

which swiftly suppressed it. In 1930 Matswa was convicted on a

378

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE DEPRESSION OF THE 1930S

pretext of currency offences and deported

to

Chad; he escaped,

but died

in

detention

in

1942. His followers moved away from

political action

to

messianism: Matswa himself became, like

Simon Kimbangu, a mythical and semi-divine hero. All the same,

he had briefly revealed

a

growing consciousness

of

the colonial

condition.

The one great rural revolt

of

the period also took place

in

French Equatorial Africa.

On the

borders

of

Moyen-Congo,

Ubangi-Shari and Cameroun, the Baya people had been driven

beyond endurance by nearly thirty years of terror: by recruitment

for

the

railway

and for the

Compagnie Forestiere's rubber-

tapping. In about 1924 a local prophet, Karnou, began preaching

non-violent resistance. Administrators were so thin on the ground

that they did not .hear of this until 1927, and by then Karnou's

many adherents, convinced by magic batons

of

their invulnera-

bility, had taken up arms. More than 350,000 people, including

60,000 warriors, took part in an astonishing display of solidarity

in

an

area previously notorious

for its

fragmented political

structure. Karnou was killed in December 1928, but the insurrec-

tion spread and persisted until

1931,

when the last phase of repres-

sion, the

'

war of the caves', was particularly savage. In its scale,

comparable to that of the Rif war of 1925-6 or the Tonkin revolt

in 1930, in its duration and its impact in France, the revolt was a

dramatic revelation of the failure of colonial policy. The govern-

ment took the measure of Karnou's movement: though it had had

to depend on ancestral values for support in small-scale societies,

the refusal

to

collaborate with

the

occupying power and

the

appeal

for

inter-tribal unity gave

it a

pivotal significance. The

country, impoverished and half-deserted, was numbed

by the

severity of repression: recovery seemed impossible.

THE DEPRESSION

OF THE

1930S

The depression in world trade which began in 1930 had seemingly

contradictory effects in French black Africa. In strictly economic

terms,

its impact was comparatively slight, for by then protection

in trade meant that the French economy acted to some extent as

a

shock-absorber. But the depression transformed French imperial

policy: it stimulated a new emphasis on production for export and

on governmental responsibility for economic infrastructures. This

379

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FRENCH BLACK AFRICA

in turn provoked a social crisis, for it was Africans who bore the

brunt of these changes.

Structural

Changes

In terms of external trade, 1930 did not in fact mark any

sudden turning-point: export values from Madagascar had peaked

in 1924, from French West Africa in 1925-6 and from French

Equatorial Africa in 1927. When the world depression struck, its

most immediate effect was on the small white minority, and it

sharply exposed the inadequacy of credit facilities.

66

There were

only two private banks in French West Africa (the Banque

francaise de l'Afrique, established in 1904, and the Banque

Commerciale africaine (1924)), and the speed of withdrawals

forced them to suspend payments. The Banque d'Afrique

occidentale (opened in 1901), which issued currency, was not yet

firmly established and the long slump in private investment

delayed its recovery until 1938—9. On the other hand, colonial

trading firms suffered no loss of business. Export tonnages were

maintained without difficulty, since agriculture was relatively

diversified, at least at the federal level, and France could still

absorb what Africa could produce: it was not, after all, in Africa

that 'over-production' had become a problem. Indeed, the depth

of the depression saw a surge of exports from plantations laid out

in the boom years of 1924-8: cotton from Ubangi-Shari, cocoa

from Gabon and Cameroun, palm products from Congo, coffee

from the Ivory Coast and bananas from Guinea. In an effort to

promote more balanced growth, customs receipts were pooled by

each federation. France sought to guarantee minimum prices for

producers by paying export bonuses to trading firms in West

Africa and by further loans to the governments of Equatorial

Africa. Moreover, since 1928 the Colonial Customs Union had

extended from Madagascar to black Africa a reciprocal agreement

whereby tariffs in France and the colonies protected the products

of both against foreign competition; this was elaborated in

1931-4. France gained a haven for investment capital that was

otherwise boxed in by world recession; the colonies gained a sure

66

Cf. the severe report of the former inspector of finance, Edmond Giscard d'Estaing,

to the Minister of Colonies, on his mission to French West Africa, 1931-2: Archives

nationales, Section Outre-Mcr, Affaires politiques,

5

59.

380

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008