Roberts A.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: from 1905 to 1940

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

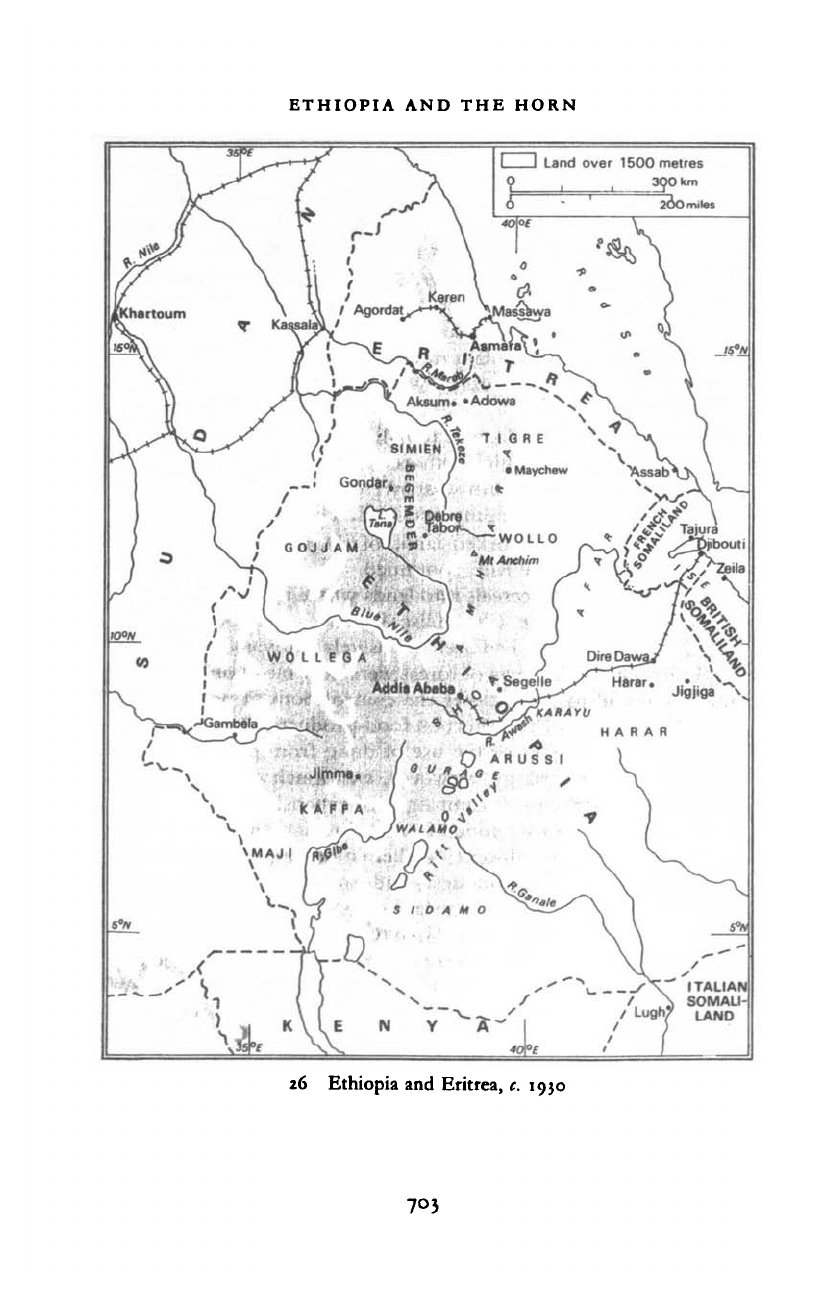

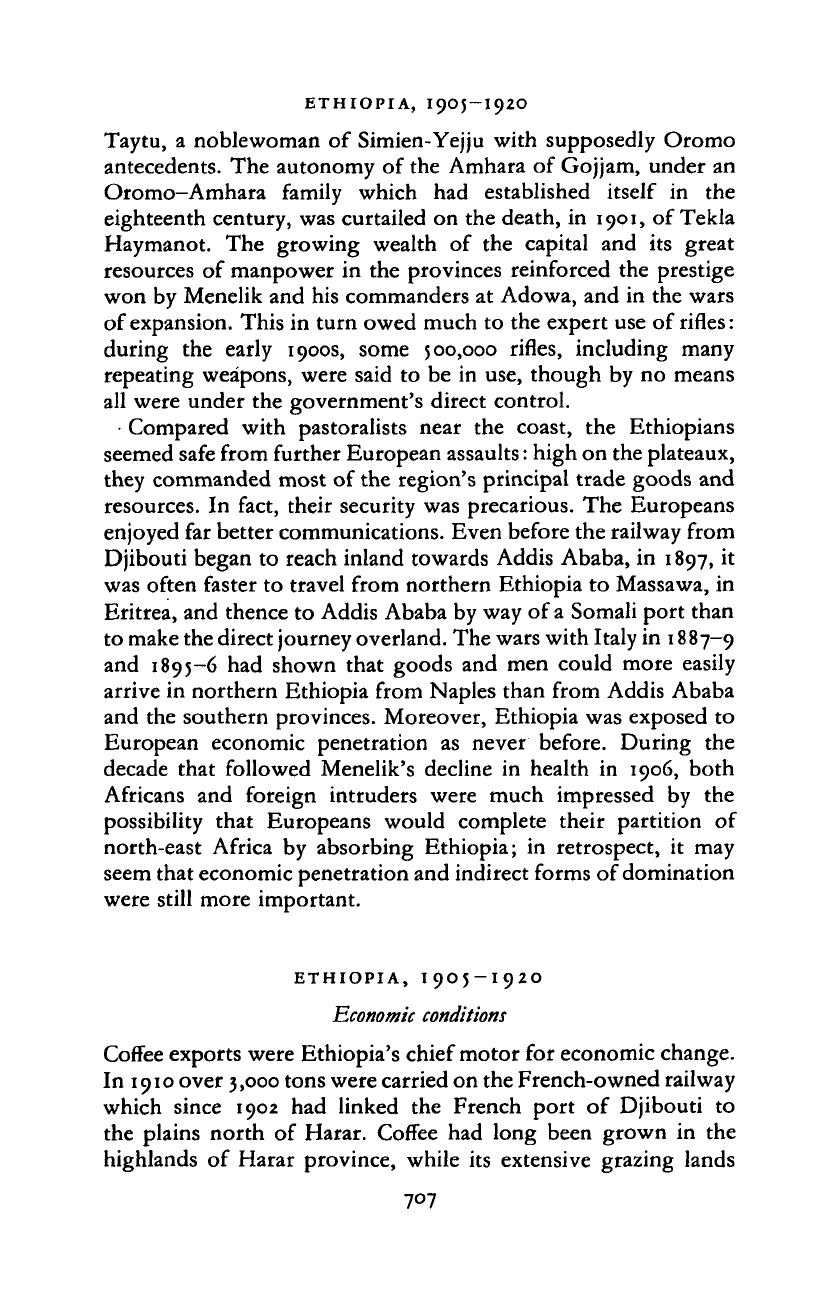

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

I

I

Land over 1500 metres

9

.

.390 km

:

'

200 miles

ITALIAN

SOMAU-

LAND

26 Ethiopia

and

Eritrea,

;. 1930

7O3

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

Cholera raged virulently in 1906 and the influenza pandemic

struck in 1918-19. Cattle plague wiped out herds along the border

with British East Africa in 1908 and in the Rift Valley in 1918.

Animal and human disease remained endemic, though in Ethiopia

the only famine comparable to that which had devastated the

empire in the early 1890s occurred in 1913-14 and was limited

to Tigre in the north. Thus the apparent stagnation of population,

even in the best-endowed parts of north-eastern Africa, must

reflect the high rates of infant mortality and the continued short

life-span, of about forty years, which was noted by European

doctors.

Despite the creation of new international frontiers, considerable

migration continued within north-eastern Africa. Eritrean hunters

were prominent on the south-western frontiers of Ethiopia, where

elephant survived and raiding persisted. The drift of population

out of the more overworked lands of the northern highlands,

principally towards the Rift, continued. These migrants brought

plough-cultivation of cereals into lands where for more than two

thousand years ensete (the 'false banana') and other crops,

including some cereals, had been intensively cultivated by hoe and

digging-stick. Great tracts of forest were now burnt off to permit

cultivation and to make easier the control both of pests and of

the local population. The effect on food-production of cultivation

by the new techniques or the use of dung from plough-oxen is

not known. The ecology, however, was much changed in the

generation after the great campaigns of expansion.

Much of the territory added to the Christian empire from the

later 1870s had been subject to earlier emperors, though Oromo

(Galla)

1

migration and conquests had greatly altered the popul-

ation in large parts of the best agricultural land since the later

sixteenth century. West of the Gibe (Omo) and south-east of the

Awash in Harar province, little of the new territory had previously

been part of the Christian empire. Moreover, Islam and animism

predominated in the regions completely new to the empire;

1

The name 'Galla' is used in all foreign literature and in Amharic, but many Oromo

object to it as a pejorative term adopted by their neighbours and equivalent to ' pagan';

others, especially those of Wallo, regard Oromo as referring only to their pre-Islamic

ancestors, though this is not the view of the Muslim Oromo of

Harar.

The use of' Galla'

among educated Ethiopians is now offensive and is no more appropriate in English

than ' Abyssinia', which Ethiopians formally dropped on joining the League of Nations,

in favour of the Greek name borrowed in ancient times.

704

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

elsewhere in Ethiopia they were minority religions. The provinces

north of the capital, Addis Ababa, had long been Christian, and

there Muslims tended to be landless traders. In the east, Islam

continued to spread, especially among Oromo peasants and

herdsmen in the highlands of Harar and Arussi. In the south and

west, among the Sidamo, Kaffa, Walarrto or Maji, local notables

often adopted Christianity and learned the Semitic language,

Amharic, which for centuries had been the language of the

Christian court. But ordinary peasants in the south and west,

unless converted already to Islam at the incorporation of their

districts into the empire, clung to their traditional religious beliefs

and customs in opposition to the intruders, whom they called

'Amhara' (or, less often,' Sidama'), meaning Christian outsiders,

regardless of their actual origins. The non-Oromo of the south-

west also retained their distinctive culture in opposition to the

Oromo who for two centuries and more had been pressing down

on them.

The ethnic composition of the imperial administration and of

the veterans settling in lands of conquest has been little studied.

Enough, however, is known to make one wary of facile contrasts

between Amhara and subject peoples. It certainly meant a great

deal to have been associated in some way with those who managed

the annexations of the later nineteenth century. Exemption from

all taxes, except the tithe on cultivated land, was granted to

veterans and other soldiers, governors and their agents, and local

Oromo, Walamo and other notables, who had allied with the

emperor Menelik and his generals. Taxes were collected, and

partly retained, by agents both of the emperor and of provincial

governors. Such agents were also military commanders, whether

of imperial troops or their own armed retainers. Southern

tax-payers, called

gebbar,

were tied to particular officials and

soldiers rather than to land. The latter exacted bribes and labour

services (sometimes on tax-free estates); as judges of their own

gebbar,

they also levied court fees. Peasants in the Christian north

had similar obligations, but they were modified by well-established

corporate rights of usufruct; they shared with their lords a

common language, religion and social code; and unlike most

southerners they had acquired firearms.

Menelik's own position as emperor was by no means unques-

tioned. An ancient line of emperors had been overthrown in 1855;

7O5

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

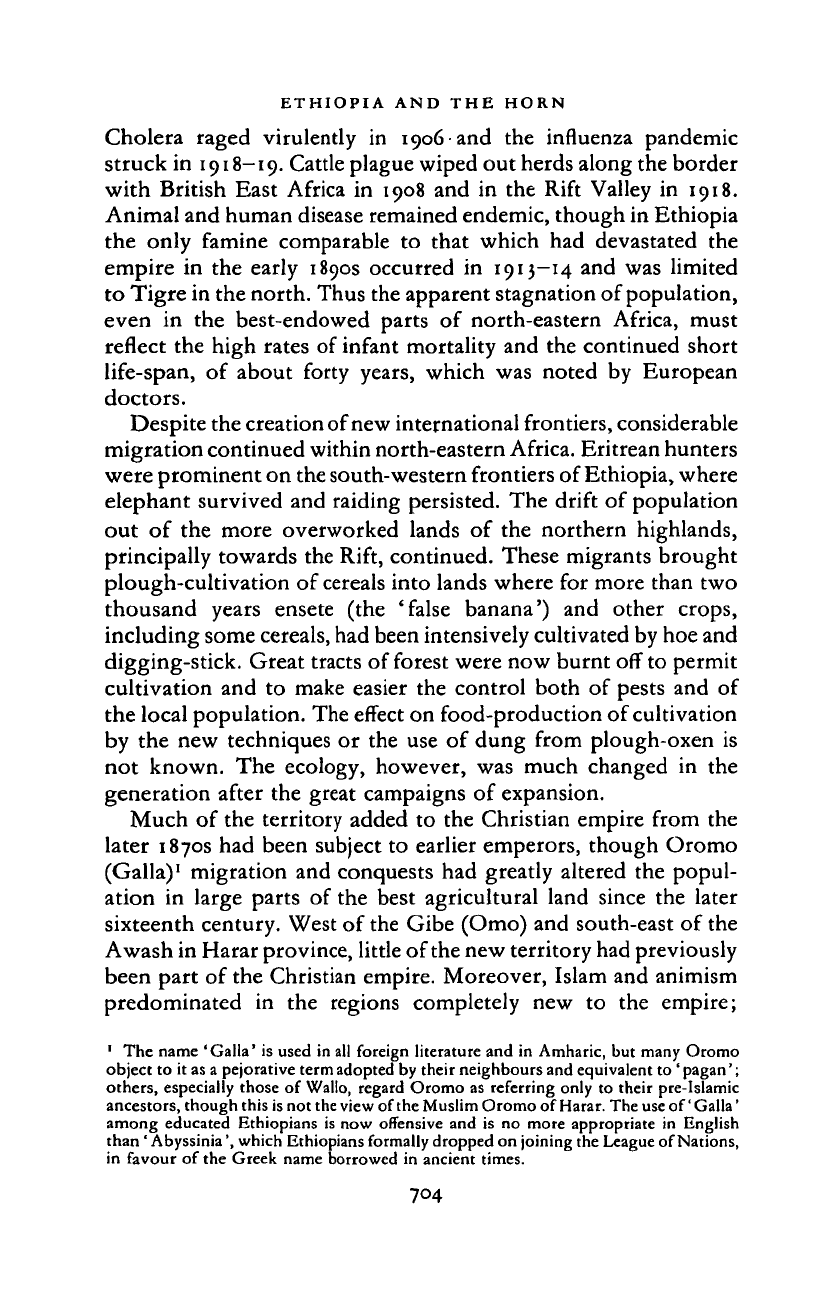

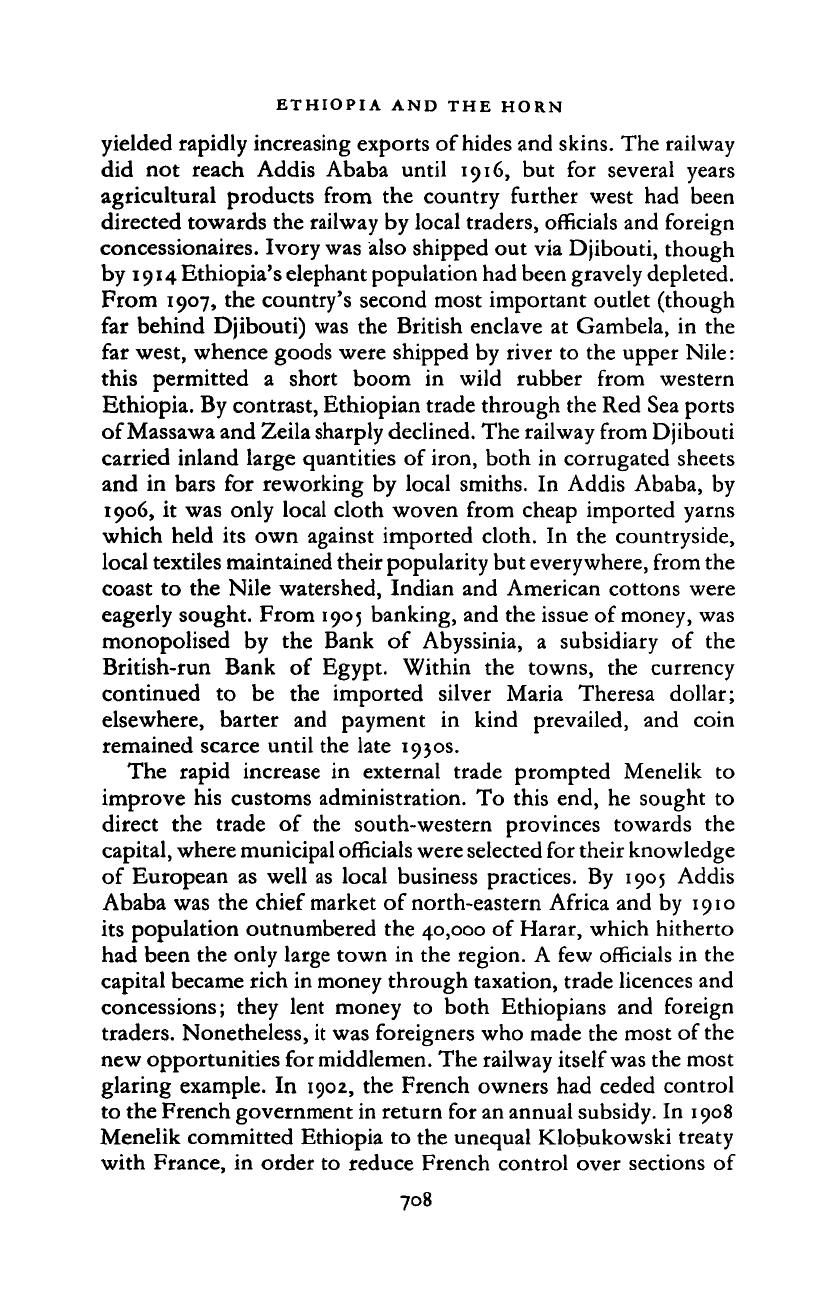

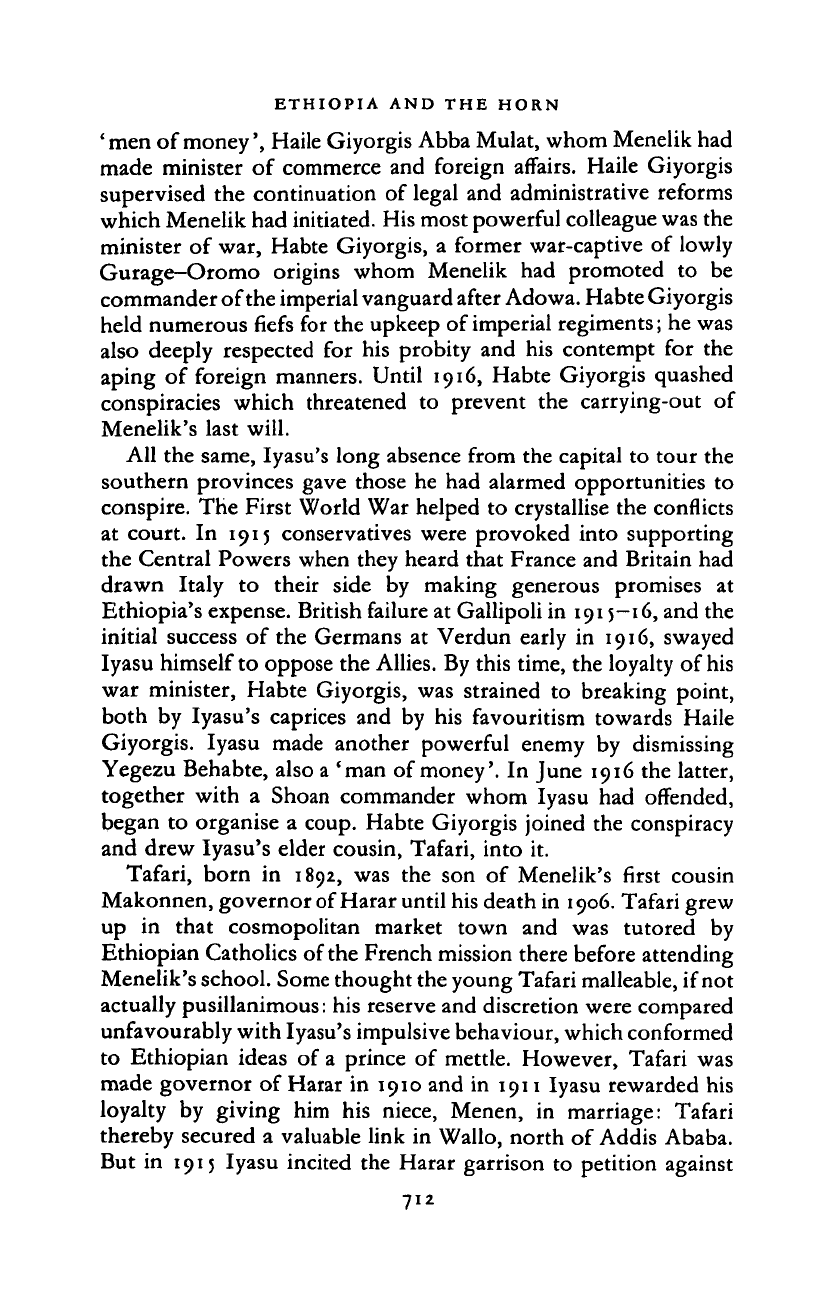

Table 5.

Kings

of

Shoa

and

emperors

of Ethiopia.

pAHaile AMENEL1K

Malakot (1844-

(182J-J5)

Shoa Shoa

ASahla- —

Sellassie

(1795-1847)

Shoa

J

«9«3) I

OZAWDITU

(1876-19J0)

-AIYASU

AMikael _

(d.

1918)

O-

(1896-19)5)

-o-

-OMenen

—|

(d.

1962)

L

o-

• AMakonnen ATafari —

(d.

1908) HAILE

SELLASSIE

(1892-1975)

L

o-

-o-

Mangasha

Haile

Sellassie

Menelik's immediate predecessor, Yohannes IV (d.1889), had

been a warlord in Tigre; while Menelik himself had been king of

Shoa. There was thus no established imperial dynasty, and despite

common resistance to the Italians at Adowa there were important

divisions within Christian Ethiopia. Provincial gentry command-

ed widespread allegiance; many in Tigre had been associated

with Yohannes; and in any case Tigrigna-speakers were disting-

uished not only from Shoans but from Amharic-speakers in

general both by language and by pride in the greater antiquity of

Christian culture in the area of Adowa and Aksum. Nonetheless,

revolts in 1898-9 and 1909 by a son and grandson of Yohannes

were speedily crushed with the ready assistance of rival Tigrean

lords.

The imperial government also commanded the loyalty of

the northern Amhara, whom Menelik cultivated through his wife

706

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA, 1905 —I92O

Taytu, a noblewoman of Simien-Yejju with supposedly Oromo

antecedents. The autonomy of the Amhara of Gojjam, under an

Oromo-Amhara family which had established itself in the

eighteenth century, was curtailed on the death, in 1901, of Tekla

Haymanot. The growing wealth of the capital and its great

resources of manpower in the provinces reinforced the prestige

won by Menelik and his commanders at Adowa, and in the wars

of expansion. This in turn owed much to the expert use of rifles:

during the early 1900s, some 500,000 rifles, including many

repeating weapons, were said to be in use, though by no means

all were under the government's direct control.

Compared with pastoralists near the coast, the Ethiopians

seemed safe from further European assaults: high on the plateaux,

they commanded most of the region's principal trade goods and

resources. In fact, their security was precarious. The Europeans

enjoyed far better communications. Even before the railway from

Djibouti began to reach inland towards Addis Ababa, in 1897, it

was often faster to travel from northern Ethiopia to Massawa, in

Eritrea, and thence to Addis Ababa by way of

a

Somali port than

to make the direct journey overland. The wars with Italy in 1887-9

and 1895-6 had shown that goods and men could more easily

arrive in northern Ethiopia from Naples than from Addis Ababa

and the southern provinces. Moreover, Ethiopia was exposed to

European economic penetration as never before. During the

decade that followed Menelik's decline in health in 1906, both

Africans and foreign intruders were much impressed by the

possibility that Europeans would complete their partition of

north-east Africa by absorbing Ethiopia; in retrospect, it may

seem that economic penetration and indirect forms of domination

were still more important.

ETHIOPIA, 1905-1920

Economic conditions

Coffee exports were Ethiopia's chief motor for economic change.

In 1910 over 3,000 tons were carried on the French-owned railway

which since 1902 had linked the French port of Djibouti to

the plains north of Harar. Coffee had long been grown in the

highlands of Harar province, while its extensive grazing lands

7°7

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

yielded rapidly increasing exports of hides and skins. The railway

did

not

reach Addis Ababa until 1916,

but for

several years

agricultural products from the country further west had been

directed towards the railway by local traders, officials and foreign

concessionaires. Ivory was also shipped out via Djibouti, though

by

1914

Ethiopia's elephant population had been gravely depleted.

From 1907, the country's second most important outlet (though

far behind Djibouti) was the British enclave

at

Gambela, in the

far west, whence goods were shipped by river to the upper Nile:

this permitted

a

short boom

in

wild rubber from western

Ethiopia. By contrast, Ethiopian trade through the Red Sea ports

of Massawa and Zeila sharply declined. The railway from Djibouti

carried inland large quantities of iron, both in corrugated sheets

and

in

bars for reworking by local smiths.

In

Addis Ababa, by

1906,

it

was only local cloth woven from cheap imported yarns

which held its own against imported cloth. In the countryside,

local textiles maintained their popularity but everywhere, from the

coast to the Nile watershed, Indian and American cottons were

eagerly sought. From 1905 banking, and the issue of money, was

monopolised

by the

Bank

of

Abyssinia,

a

subsidiary

of the

British-run Bank

of

Egypt. Within

the

towns,

the

currency

continued

to be the

imported silver Maria Theresa dollar;

elsewhere, barter

and

payment

in

kind prevailed,

and

coin

remained scarce until the late 1930s.

The rapid increase

in

external trade prompted Menelik

to

improve his customs administration. To this end, he sought

to

direct

the

trade

of

the south-western provinces towards

the

capital, where municipal officials were selected for their knowledge

of European as well as local business practices. By 1905 Addis

Ababa was the chief market of north-eastern Africa and by 1910

its population outnumbered the 40,000 of Harar, which hitherto

had been the only large town in the region. A few officials in the

capital became rich in money through taxation, trade licences and

concessions; they lent money

to

both Ethiopians and foreign

traders. Nonetheless, it was foreigners who made the most of the

new opportunities for middlemen. The railway itself was the most

glaring example.

In

1902, the French owners had ceded control

to the French government in return for an annual subsidy. In 1908

Menelik committed Ethiopia to the unequal Klobukowski treaty

with France, in order to reduce French control over sections of

708

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA, 1905 —1920

the railway within Ethiopia and to break a financial deadlock

which had halted construction since 1902. The treaty limited

Ethiopian taxes on French goods to

10

per cent; moreover, it gave

Frenchmen and their numerous French proteges the right to trial

in Ethiopia by their own consul while French law would apply

in mixed cases with French defendants. Most-favoured-nation

clauses automatically extended the limitation on customs duties

to imports from other European countries and the United States.

Extra-territorial privileges were soon claimed by all foreigners,

including the many hundreds of British-protected Somali, Indians

and Arabs from Aden who, after 1900, with Greeks and French-

protected Armenians and Levantines, controlled the bulk of

foreign trade and were also settled in the larger market towns as

craftsmen.

Menelik's love of new things did not often bring about actual

change even at the height of his personal prestige after Adowa.

In permitting the railway to be built and foreign diplomats to

reside in the capital, and in much else, he had to override the

conservative prudence of his whole court. The decline of his

health in 1906 and the external threat which then revived also

explain the incompleteness of his reforms. Some of Menelik's

targets were simply not practicable. Imported cartridges remained

cheaper than those made locally from imported materials by the

foreigners who received concessions from 1907. Sometimes

Menelik failed to practise what he preached. Although he had

chartered the Bank of Abyssinia he did not himself use it and

continued to hoard silver dollars as other men of means did.

Admittedly, he circumvented clerical opposition to the European

curriculum in the palace school he had founded in 1905, by

bringing Copts from Egypt in 1906 to teach the new subjects (in

French); and in 1908 he expanded his school into Ethiopia's first

secular institution of higher learning. Yet he provided no means

at all for carrying out edicts of 1907-8 which exhorted parents

to send children of both sexes to be taught to read and write at

their parish churches. Rinderpest had caused terrible losses to

herds and plough-oxen; yet throughout Menelik's reign no one

was sent abroad to become

a

veterinarian or to learn about modern

agriculture. He was fascinated by machinery, which his courtiers

disdained, but once imported much of it was stored away or fell

idle.

When the first automobile arrived in 1907, Menelik sent two

709

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

Ethiopians to Germany to learn to drive, but the only motor road

was a short one built in 1902 for hauling timber for his buildings.

For all these limitations, there were two technical advances

which had lasting effects.

In

1904 Menelik was visited

by an

Eritrean printer with

ten

years' experience

on the

Swedish

mission's presses. He offered

to

put

to

work equipment then

stored in the palace and to bring from Europe whatever else was

needed to begin government printing in Ethiopic type. Menelik

promptly commissioned him.

And

since 1898 Menelik

had

contrived

to

link the capital

to

the provinces by telephone and

telegraph through exploiting the wish of the French and Italians

to link their legations

to

their Red

Sea

colonies. With

the

expansion of this network after the turn of the century, provincial

officials found themselves tied to the court as never before.

The succession struggle

The principal work of Menelik's last years of active government

was

to

keep European imperialism

at

bay while the problem of

the succession was solved. In order to secure recognised bound-

aries,

Menelik had been obliged

in

1897

to

abandon

to

French

Somaliland the salines which supplied all southern Ethiopia with

edible salt, and to agree in 1902 not to interfere with the waters

of the Blue Nile without consulting the British. In 1900 Menelik

had formally surrendered highland territories which Italy had

annexed to Eritrea in defiance of earlier treaties; in 1908 he ceded

to Italy more of the Red Sea littoral and also Lugh, in the south-

east. These frontiers survived both world wars. Meanwhile,

in

May 1906, Menelik had

his

first stroke. Although

he

quickly

recovered, the representatives of France, Britain and Italy came to

him in a group and told him that their governments had agreed to

ensure the empire's integrity, if that could be done. They had also

agreed that, should it fall apart on his death, they would co-operate

in dividing Ethiopia into three spheres

of

influence. Menelik

remonstrated, but he had no means of curbing their impertinence,

though Germany, Austria, Belgium

and the

USA

had

been

encouraged to open legations and consulates in Addis Ababa. The

colonial powers who controlled Ethiopia's outlets rarely acted

together in the thirty years following the signing of the Tripartite

Treaty in December 1906. Nevertheless, their claim to be able to

710

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA, 1905-1920

settle Ethiopian questions by common accord was a warning that

Ethiopia had gained no more than a respite by its frontier treaties.

The question of the imperial succession was certainly

a

major

problem:

it

was not fixed by any accepted rule, and

in

any case

Menelik's most direct heir was his grandson Iyasu, born in 1898.

Iyasu's mother was

a

daughter

of

Menelik; his father was Ras

Mikael, the great provincial lord of the Oromo of

Wallo,

who in

1878

had

been forced

to

give

up

Islam

for

Christianity

by

Menelik's predecessor Yohannes IV. To prepare for

a

minority,

Menelik gave his household officials ministerial titles

in

1907-8

and instructed them to act in unison.

In

mid-1908, Menelik was

partly paralysed. Two further strokes

in

1909 left him wholly

incapacitated, and in October Iyasu was publicly proclaimed heir

under the regency of a prominent Shoan.

These plans for

a

peaceful transfer

of

power did not succeed.

The regent died

in

1911, more than two years before Menelik

himself.

To

free themselves from supervision,

the

ministers

humoured the thirteen-year-old Iyasu's demand to act on his own.

He disdained

to

learn about administration,

and he

flouted

convention by appearing in public in Muslim dress, by eating with

Muslims and by visiting mosques on Muslim holidays. ' You are

fat,

old and

useless,'

he

told

his

grandfather's officials, while

boasting of how he would despoil them all.

2

During a long tour

in 1912, Iyasu enslaved and butchered animists west of Kaffa and

along

the

Sudan border.

In

1913

and

1915—16, however,

he

behaved with equal cruelty towards Muslims

—

the

c

Afar,

f

Ise

Somali and Karayu Oromo — on his return from tours east of

the capital. This behaviour hardly bears out those who accused

Iyasu

of

showing undue favour

to

Muslims suffering

discrimination.

3

Nor does

it

justify later claims that Iyasu was

a

pioneer

of

secular nationalism: he sought popularity by persec-

uting the converts of European missions, but he gave generously

to Ethiopian churches. Iyasu left routine affairs

in

Addis Ababa

in the capable

if

avaricious hands

of

the most successful

of

the

2

Gebre Egziabeher Elyas, 'Ye-Tarik Mastawesha, 1901-1922 [1908-9

to

1929-30

Gregorian]',

Amharic MS. no. 25, fol. 28, National Library, Addis Ababa: quoted

in

Aby Demissie, 'Lij Iyasu.

A

perspective study

of

his short reign', unpublished senior

essay, Department

of

Social and Political Science, Addis Ababa University (1964), 25,

which also quotes

a

similar boast from an informant.

3

Mahteme Sellassie, Zeqre neger (2nd

ed.

Addis Ababa, 1969-70), note

'A',

719-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ETHIOPIA AND THE HORN

'men of money', Haile Giyorgis Abba Mulat, whom Menelik had

made minister

of

commerce

and

foreign affairs. Haile Giyorgis

supervised

the

continuation

of

legal

and

administrative reforms

which Menelik had initiated. His most powerful colleague was the

minister

of

war, Habte Giyorgis,

a

former war-captive

of

lowly

Gurage—Oromo origins whom Menelik

had

promoted

to be

commander of the imperial vanguard after Adowa. Habte Giyorgis

held numerous fiefs

for

the upkeep

of

imperial regiments; he was

also deeply respected

for his

probity

and his

contempt

for the

aping

of

foreign manners. Until 1916, Habte Giyorgis quashed

conspiracies which threatened

to

prevent

the

carrying-out

of

Menelik's last will.

All the same, Iyasu's long absence from the capital

to

tour the

southern provinces gave those

he had

alarmed opportunities

to

conspire. The First World War helped

to

crystallise the conflicts

at court.

In 1915

conservatives were provoked into supporting

the Central Powers when they heard that France and Britain had

drawn Italy

to

their side

by

making generous promises

at

Ethiopia's expense. British failure at Gallipoli in 1915-16, and the

initial success

of

the Germans

at

Verdun early

in

1916, swayed

Iyasu himself to oppose the Allies. By this time, the loyalty

of

his

war minister, Habte Giyorgis,

was

strained

to

breaking point,

both

by

Iyasu's caprices

and by his

favouritism towards Haile

Giyorgis. Iyasu made another powerful enemy

by

dismissing

Yegezu Behabte, also a 'man

of

money'.

In

June 1916 the latter,

together with

a

Shoan commander whom Iyasu

had

offended,

began

to

organise

a

coup. Habte Giyorgis joined

the

conspiracy

and drew Iyasu's elder cousin, Tafari, into

it.

Tafari, born

in

1892,

was the son of

Menelik's first cousin

Makonnen, governor of Harar until his death in 1906. Tafari grew

up

in

that cosmopolitan market town

and was

tutored

by

Ethiopian Catholics of the French mission there before attending

Menelik's school. Some thought the young Tafari malleable, if not

actually pusillanimous: his reserve and discretion were compared

unfavourably with Iyasu's impulsive behaviour, which conformed

to Ethiopian ideas

of

a prince

of

mettle. However, Tafari

was

made governor

of

Harar

in

1910 and

in

1911 Iyasu rewarded

his

loyalty

by

giving

him his

niece, Menen,

in

marriage: Tafari

thereby secured

a

valuable link

in

Wallo, north

of

Addis Ababa.

But

in

1915 Iyasu incited

the

Harar garrison

to

petition against

712

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008