Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

and polychaete worms, living buried in the substrate and feeding by filtering the

water when they are covered by the tides. This environment is completely free

of large seaweeds, whose holdfasts can find no anchorage. Flowering plants are

almost, but not completely, absent from intertidal environments. The exceptions

occur where it is possible for them to be anchored by their roots and this require-

ment limits them to the more stable and muddy areas colonized by ‘sea grasses’

such as Zostera and Posidonia or tussocks of Spartina. In the tropics, mangroves

occupy this kind of habitat, adding a shrubby, woody dimension to the marine

littoral zone.

4.5.5 Estuaries

Estuaries occur at the confluence of a river (fresh water) and a tidal bay (salt

water). They provide an intriguing mix of the conditions normally experienced

in rivers, shallow lakes and tidal communities. Salt water, more dense than fresh

water, tends to enter along the bottom of an estuary as a salt wedge. As it mixes

with the outflowing fresh water, a brackish middle layer is created, then it returns

downstream on the outgoing tide. The shape of the saltwater wedge is largely

determined by the size of the discharge of the river flowing into the estuary;

high discharge tends to create a smaller wedge of salt water and less mixing. The

strong gradients in salinity, in both space and time, are reflected in a specialized

estuarine fauna. Some animals cope through particular physiological mechanisms.

Others avoid the variable salt concentrations by burrowing, closing protective

shells or moving away when conditions do not favor them.

Chapter 4 Conditions, resources and the world’s communities

139

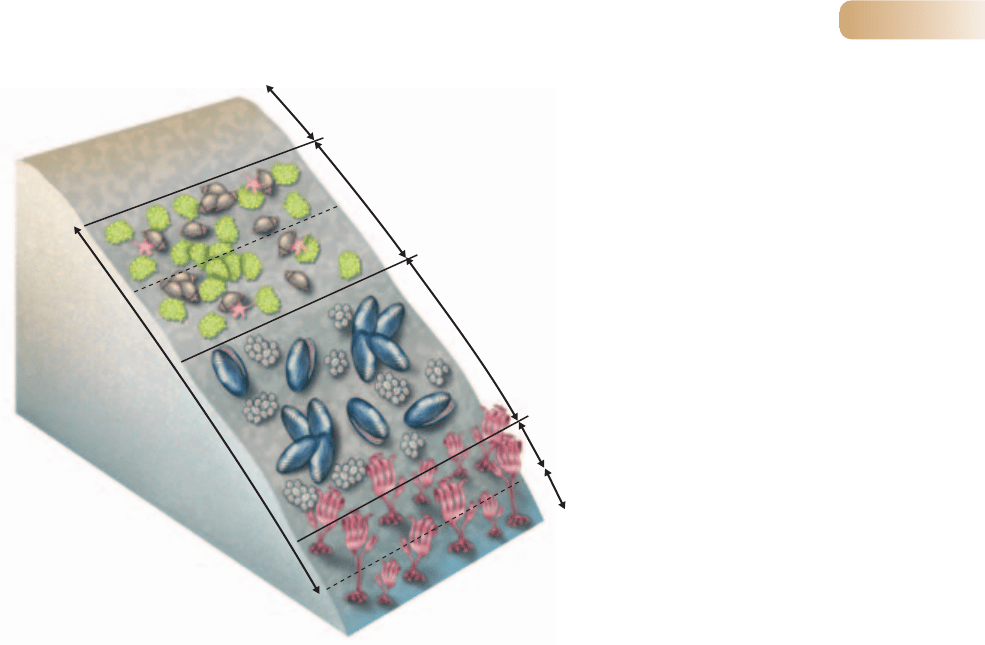

Supralittoral zone

Supralittoral fringe

Midlittoral zone

Infralittoral fringe

Infralittoral zone

Upper limit of periwinkle snails

Upper limit of barnacles

Upper limit of

lamination seaweeds

Land

Sea

Littoral zone

Figure 4.18

A general zonation scheme for the

seashore determined by relative

lengths of exposure to the air and

to the action of waves. At the top of

the shore is the supralittoral zone

(the splash zone above the high tide

level). The littoral zone, between high

and low tide levels, can be divided

into a midlittoral zone together with

a supralittoral fringe above and

an infralittoral fringe below. The

infralittoral zone proper lies below

the low tidal limit. Characteristic

communities of animals and plants

occur in these different zonation

bands.

AFTER RAFFAELLI & HAWKINS, 1996

9781405156585_4_004.qxd 11/5/07 14:47 Page 139

Part II Conditions and Resources

140

Geographic patterns at large and small scales

The variety of influences on climatic conditions over

the surface of the globe causes a mosaic of climates.

This, in turn, is responsible for the large-scale pattern

of distribution of terrestrial biomes. However, biomes

are not homogeneous within their hypothetical bound-

aries; every biome has gradients of physicochemical

conditions related to local topographic, geological and

soil features. The communities of plants and animals

that occur in these different locations may be quite

distinct.

In most aquatic environments it is difficult to recog-

nize anything comparable to terrestrial biomes; the

communities of streams, rivers, lakes, estuaries and

open oceans reflect local conditions and resources

rather than global patterns in climate. The composi-

tion of local communities can change over time scales

ranging from hours, through decades, to millennia.

Terrestrial biomes

A map of biomes is not usually a map of the distribu-

tion of species. Instead, it shows where we find areas

of land dominated by plants with characteristic life

forms.

Tropical rain forest represents the global peak of

evolved biological diversity. Its exceptional productiv-

ity results from the coincidence of high solar radiation

received throughout the year and regular and reliable

rainfall.

Savanna consists of grassland with scattered

small trees. Seasonal rainfall places the most severe

restrictions on the diversity of plants and animals in

savanna; grazing herbivores and fire also influence

the vegetation, favoring grasses and hindering the

regeneration of trees.

Temperate grassland occurs in the steppes,

prairies and pampas. Typically, it experiences sea-

sonal drought, but the role of climate in determining

vegetation is usually overridden by the effects of graz-

ing animals. Humans have transformed temperate

grassland more than any other biome.

Many desert plants have an opportunistic lifestyle,

stimulated into germination by the unpredictable

rains; others, such as cacti, are long-lived and have

sluggish physiological processes. Animal diversity is

low in deserts, reflecting the low productivity of the

vegetation and the indigestibility of much of it.

Temperate forests at lower latitudes experience

mild winters, and the vegetation consists of broad-

leaved, evergreen trees. Nearer the poles, the seasons

are strongly marked, and vegetation is dominated

by deciduous trees. Soils are usually rich in organic

matter.

Northern coniferous forests have few tree species

and contrast strongly with the biodiversity of tropical

rain forests, reflecting a slow recovery from the catas-

trophes of the ice ages, and the overriding local con-

straint of frozen soil. Nearer the poles, the vegetation

changes to tundra, and the two often form a mosaic

in the Low Arctic. The mammal populations of the

northern biomes often pass through remarkable cycles

of expansion and collapse.

Aquatic environments

Streams and rivers are characterized by their linear

form, unidirectional flow, fluctuating discharge and

unstable beds. The terrestrial vegetation surrounding

a stream has strong influences on the resources avail-

able to its inhabitants; the conversion of forest to

agriculture can have far-reaching effects.

Lake ecology is defined by the relatively station-

ary nature of its water. Some lakes stratify vertically

in response to temperature, with consequences for

the availability of oxygen and plant nutrients. Lakes

higher in a landscape may receive more of their

water from rainfall; those at lower altitude receive

more from ground water. Saline lakes in arid regions

lack a stream outflow and lose water only by

evaporation.

The oceans cover the major part of the Earth’s

surface and receive most of the solar radiation. How-

ever, many areas have very low biological activity

SUMMARY

Summary

9781405156585_4_004.qxd 11/5/07 14:47 Page 140

Chapter 4 Conditions, resources and the world’s communities

141

because of a shortage of mineral nutrients. Below

the surface zone is increasing darkness, but at the

ocean floor there may be an abyssal environment

that supports a diverse community with very slow

biological activity.

Coastal communities are enriched by nutrients

from the land, but they are also affected by waves

and tides. Within a single stretch of coast, there is a

zonation in the flora and fauna that differs between

areas with heavy or light wave action.

Estuaries occur at the confluence of a river (fresh

water) and a tidal bay (salt water). Strong gradients

in salinity, in both space and time, are reflected in a

specialized estuarine fauna.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

Review questions

Asterisks indicate challenge questions

1 Describe the various changes in climate that

occur with changing latitude, including an

explanation of why deserts are more likely

to be found at around 30° latitude than at other

latitudes.

2 How would you expect the climate to change

as you crossed from west to east over the

Rocky Mountains?

3* Biomes are differentiated by gross differences

in the nature of their communities, not by the

species that happen to be present. Explain

why this is so.

4 The tropical rain forest is a diverse community

supported by a nutrient-poor soil. Account for

this.

5* Which of the Earth’s biomes do you think

have been most strongly influenced by people?

How and why have some biomes been more

strongly affected by human activity than others?

6 What is meant by the ‘stratification’ of water in

lakes? How does it occur? And what are the

reasons for variations in stratification from time

to time and from lake to lake?

7 Describe how the logging of a forest may

influence the community of organisms

inhabiting a stream running through the

affected area.

8 Why is much of the open ocean, in effect, a

‘marine desert’?

9 Discuss some reasons why community

composition changes as one moves (i) up a

mountain, and (ii) down the continental shelf

into the abyssal depths of the ocean.

10* Why are broad geographic classifications

of aquatic communities less feasible than

broad geographic classifications of terrestrial

communities? What characteristics of

aquatic ecosystems buffer the effects of

climate?

9781405156585_4_004.qxd 11/5/07 14:47 Page 141

9781405156585_4_004.qxd 11/5/07 14:47 Page 142

PART THREE

Individuals, Populations,

Communities and Ecosystems

5 | Birth, death and movement 145

6 | Interspecific competition 182

7 | Predation, grazing and disease 217

8 | Evolutionary ecology 251

9 | From populations to communities 281

10 | Patterns in species richness 323

11 | The flux of energy and matter through ecosystems 357

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 143

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 144

145

Chapter 5

Birth, death and movement

CHAPTER CONTENTS

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Life cycles

5.3 Monitoring birth and death: life tables and fecundity schedules

5.4 Dispersal and migration

5.5 The impact of intraspecific competition on populations

5.6 Life history patterns

Chapter contents

KEY CONCEPTS

In this chapter you will:

l

appreciate the difficulties of counting individuals, but the necessity

of doing so for understanding the distribution and abundance of

organisms and populations

l

appreciate the range of life cycles and patterns of birth and death

exhibited by different organisms

l

understand the nature and the importance of life tables and

fecundity schedules

l

understand the role and the importance of dispersal and migration in

the dynamics of populations

l

understand the impact of intraspecific competition on birth, death and

movement, and hence on populations

l

appreciate that life history patterns linking types of organism to types

of habitat can be constructed but also recognize the limitations of

those patterns

Key concepts

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 145

5.1 Introduction

As ecologists, we try to describe and understand the distribution and abundance

of organisms. We may do so because we wish to control a pest or conserve an

endangered species, or simply because we are fascinated by the world around us

and the forces that govern it. A major part of our task, therefore, involves study-

ing changes in the size of populations. We use the term population to describe

a group of individuals of one species. What actually constitutes a population,

though, varies from species to species and from study to study. In some cases,

the boundaries of a population are obvious: the sticklebacks occupying a small

lake are ‘the stickleback population of the lake’. In other cases, boundaries are

determined more by an investigator’s purpose or convenience. Thus, we may

study the population of lime aphids inhabiting one leaf, one tree, one stand of

trees or a whole woodland. What is common to all uses of population is that it is

defined by the number of individuals that compose it: populations grow or

decline by changes in those numbers.

The processes that change the size of populations are birth, death and move-

ment into and out of that population. Trying to understand the causes of changes

in population size is important because the science of ecology is not just about

understanding nature but often also about predicting or controlling it. We might,

for example, wish to reduce the size of a population of rabbits that can do serious

harm to crops. We might do this by increasing the death rate by introducing the

myxomatosis virus to the population, or by decreasing the birth rate by offering

them food that contains a contraceptive. We might encourage their emigration by

bringing in dogs, or prevent their immigration by fencing.

Similarly, a nature conservationist may wish to increase the population of

a rare endangered species. In the 1970s, the numbers of bald eagles, ospreys

and other birds of prey in the United States began a rapid decline. This might

have been because their birth rate had fallen, or their death rate had risen,

or because the populations were normally maintained by immigration and

this had fallen, or because individuals had emigrated and settled elsewhere.

Eventually the decline was traced to reduced birth rates. The insecticide DDT

(dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was widely used at the time (it is now banned

in the United States) and had been absorbed by many species on which the birds

preyed. As a result, it accumulated in the bodies of the birds themselves and

affected their physiological processes so that the shells of their eggs became so thin

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

146

what is a population?

All questions in ecology – however scientifically fundamental, however crucial

to immediate human needs and aspirations – can be reduced to attempts to

understand the distributions and abundances of organisms, and the processes

– birth, death and movement – that determine distribution and abundance.

In this chapter, these processes, the methods of monitoring them and

their consequences are introduced.

birth, death and movement

change the size of populations

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 146

that the chicks often died in the egg. Conservationists charged with restoring the

bald eagle population had to find a way to increase the birds’ birth rate. The

banning of DDT achieved this end.

5.1.1 What is an individual?

A population is characterized by the number of individuals it contains, but for

some kinds of organism it is not always clear what we mean by an individual.

Often there is no problem, especially for unitary organisms. Birds, insects, reptiles

and mammals are all unitary organisms. The whole form of such organisms, and

their program of development from the moment when a sperm fuses with an egg,

is predictable and determinate. An individual spider has eight legs. A spider that

lived a long life would not grow more legs.

But none of this is so simple for modular organisms such as trees, shrubs and

herbs, corals, sponges and very many other marine invertebrates. These grow by

the repeated production of modules (leaves, coral polyps, etc.) and almost always

form a branching structure. Such organisms have an architecture: most are rooted

or fixed, not motile (Figure 5.1). Both their structure and their precise program

of development are not predictable but indeterminate. We could count the

individual trees in a forest, but would this signify the ‘size’ of the tree population?

Not unless we also noted whether the trees were young saplings (few leaves and

branches each), or old individuals, each with many more such modules. Indeed,

it may make more sense not to count the individual trees themselves but the total

number of modules instead.

In modular organisms, then, we need to distinguish between the genet – the

genetic individual – and the module. The genet is the individual that starts life

as a single-celled zygote and is considered dead only when all its component

modules have died. A module starts life as a multicellular outgrowth from another

module and proceeds through a life cycle to maturity and death even though

the form and development of the whole genet are indeterminate. We usually

think of unitary organisms when we write or talk about populations, perhaps

because we ourselves are unitary, and there are certainly many more species of

unitary than of modular organisms. But modular organisms are not rare excep-

tions and oddities. Most of the living matter (biomass) on Earth and a large part

of that in the sea is of modular organisms: the forests, grasslands, coral reefs and

peat-forming mosses.

5.1.2 Counting individuals, births and deaths

Even with unitary organisms, we face enormous technical problems when we try

to count what is happening to populations in nature. A great many ecological

questions remain unanswered because of these problems. For example, resources

can only be focused on controlling a pest effectively if it is known when its birth

rate is highest. But this can only be known by monitoring accurately either births

themselves or rising total numbers – neither of which is ever easy.

If we want to know how many fish there are in a pond we might obtain an

accurate count by putting in poison and counting the dead bodies. But apart from

the questionable morality of doing this, we usually want to continue studying a

population after we have counted it. Occasionally it may be possible to trap alive

Chapter 5 Birth, death and movement

147

unitary and modular organisms

modular organisms are

themselves populations

of modules

the difficulties of counting

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 147

all the individuals in a population, count them and then release them. With birds,

for example, it may be possible to mark nestlings with leg rings and ultimately

recognize every individual (except immigrants) in the population of a small wood-

land. It is not too difficult to count the numbers of large mammals such as deer

on an isolated island. But it is very much more difficult to count the numbers of

lemmings in a patch of tundra because they spend a large part of the year (and

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

148

(a)

(b)

(b)

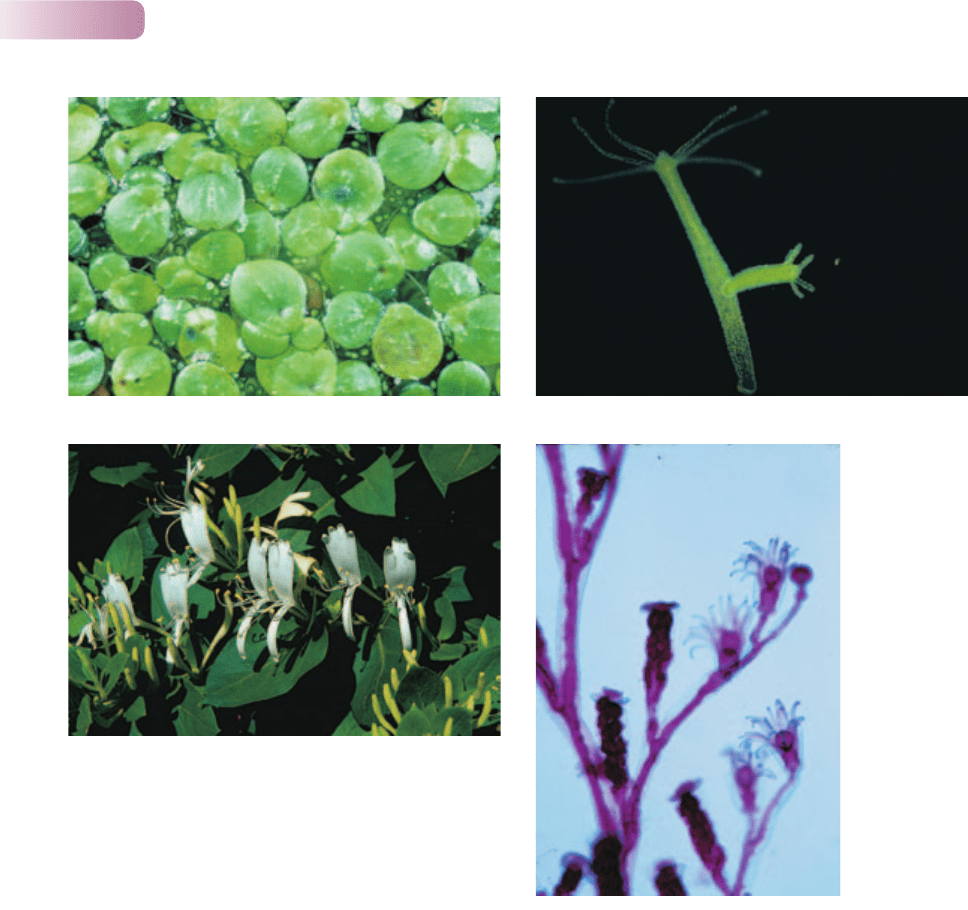

Figure 5.1

Modular plants (on the left) and animals (on the right), showing the underlying parallels in the various ways they may be constructed. (a) Modular

organisms that fall to pieces as they grow: duckweed (Lemna sp.) (© John D. Cunningham) and Hydra sp. (© Larry Stepanowicz). (b) Freely

branching organisms in which the modules are displayed as individuals on ‘stalks’: a vegetative shoot of a higher plant (Lonicera japonica) with

leaves (feeding modules) and a flowering shoot (© Visuals Unlimited), and a hydroid colony (Obelia) bearing both feeding and reproductive

modules (© Larry Stepanowicz).

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF VISUALS UNLIMITED

9781405156585_4_005.qxd 11/5/07 14:49 Page 148