Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In an ideal sustainable world, new soil would be formed as fast as the old was

lost. In Britain about 0.2 tonnes of new soil is produced naturally per hectare

per year and it has been suggested that a tolerable (although not necessarily

sustainable) rate of soil erosion might be about 2.0 t ha

−1

yr

−1

. However, rates of

erosion have been recorded of up to 48 t ha

−1

yr

−1

!

Almost all (perhaps all) agricultural land will support higher yields if artificial

fertilizers are applied to supplement the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium sup-

plied naturally by the soil. Fertilizers are cheap, easy to handle, of a guaranteed

composition, allow even and accurate application, and higher and more pre-

dictable yields. When there is an overwhelming reliance on them, however,

maintaining the organic matter capital of the soil tends to be neglected and has

declined everywhere.

The degradation of soil by agriculture can be prevented, or at least slowed

down, by: (i) incorporating farmyard manure, crop residues and animal wastes;

(ii) alternating years under cultivation with years of fallow; or (iii) returning the

land to grazed pasture or rangeland. Such practices conserve soil quality in

technologically sophisticated agricultures in temperate regions.

But soil degradation is most serious and least easily prevented in less developed

countries. The problems are greatest in high rainfall areas and on steeply sloping

ground in the tropics where organic matter in the soil also decomposes more

rapidly. The United Nations soil conservation strategy of ‘Agenda 21’ (formulated

in Rio de Janeiro, 1992) recommended measures to prevent soil erosion and

promote erosion control.

The most cost-effective technology used in reducing soil erosion is considered

to be contour-based cultivation (Figure 12.13). In India, contour ditches have

helped to quadruple the survival chances of tree seedlings and quintuple their

early growth in height. Deeply rooted, hedge-forming ‘vetiver’ grass, planted in

contour strips across hill slopes, slows water runoff dramatically, reduces erosion

and increases the moisture available for crop growth. Currently 90% of soil con-

servation efforts in India are based on such biological systems. Simple technologies

involving rock embankments constructed along contour lines for soil and water

conservation have also been successful. Embanked fields in Burkina Faso (west

Africa) yielded an average of 10% more crop production than traditional fields

in a normal year and, in drier years, almost 50% more (United Nations, 1998).

Chapter 12 Sustainability

409

soil maintenance

contour plowing and terracing –

Agenda 21

Figure 12.13

Terracing of hill and

mountainous land.

© D. CAVAGNARO, VISUALS UNLIMITED

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 409

Such terracing provides a very high level of soil conservation but is possible only

where labor is cheap. On lesser slopes, by ploughing and cultivating in strips along

the contours, runoff of soil can be significantly reduced.

Agricultural land is also highly susceptible to degradation in arid and semiarid

regions. Both overgrazing and excessive cultivation expose the soil directly to ero-

sion by the wind and to rare but fierce rainstorms. In the process of ‘desertization’,

land that is arid or semiarid but has supported subsistence or nomadic agricul-

ture gives way to desert. The process has often been slowed down for a time by

irrigating the land. This gives a temporary remission but lowers the water table

and salts accumulate in the topsoil (salinization). Once salts have started to

accumulate, the process of salinization tends to spread and leads to an expansion

of sterile, white salt deserts. This has been a particular hazard in irrigated areas

of Pakistan.

Forests protect soil from erosion because the canopy absorbs the direct impact

of the rain on the soil surface, the perennial root systems bind the soil and leaf

fall continually adds organic matter. But when forests are clear felled and then

replanted, there is an open ‘window of opportunity’ for soil erosion until the

forest canopy closes again. Cultivation and replanting along contours gives some

control over soil erosion during this danger period, but the best precaution is to

avoid clear felling and extract only a proportion of a forest stand at each harvest.

This can often be technically difficult and more expensive.

12.4.2 The sustainability of water as a resource

In the 1960s and 1970s, the main worry about the sustainability of global resources

concerned energy supplies that were recognized to be finite and exhaustible.

While energy resources remain finite, concern has shifted because exploration

has revealed much larger reserves of oil, gas and even coal than had been entered

into earlier environmental balance sheets. Water has now come into sharper focus.

Fresh water, which is used in crop irrigation and for domestic consumption, is of

crucial importance. On a global scale, agriculture is the largest consumer of fresh

water, taking more than 70% of available supplies and more than 90% in parts

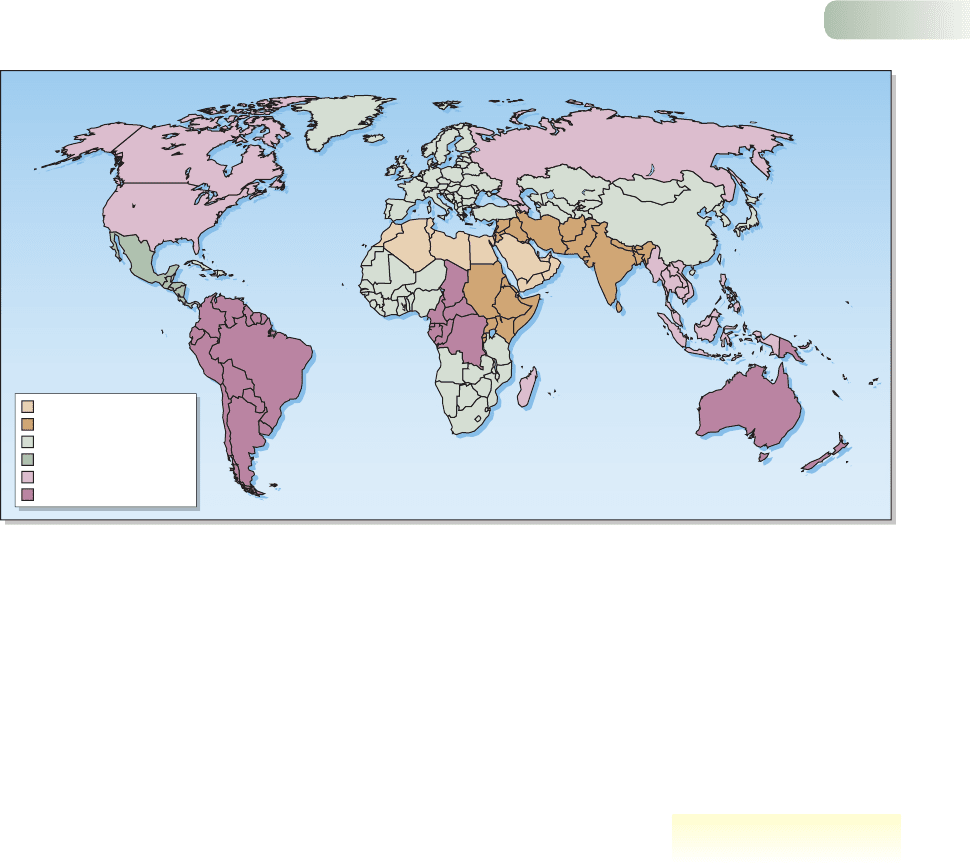

of South America, central Asia and Africa.

There is a fixed stock of water on the globe and it is continually recycled as

it evaporates from vegetation, land and sea and is then condensed and redis-

tributed as precipitation. The human species now uses, directly or indirectly,

more than half of the world’s accessible water supply. The fresh water avail-

able per capita worldwide fell from 17,000 m

3

in 1950 to 7300 m

3

in 1995

and there is very considerable variation in availability from region to region

(Figure 12.14). Many assessments of the problems of water supply suggest that

countries with less than 1000 m

3

per person per year experience chronic scarcity.

Water is widely thought to be the resource that future wars will be fought over.

Even at a national level, the allocation of water resources can cause political

problems, as occur for example in conflicts in California between urban and

agricultural demands for water from the Colorado River. At the international

level, conflict arises between countries that are upstream of their neighbors and

are in a position to dam and divert water supplies. There are bitter cross-border

disputes in South America, Africa and the Middle East between nations that share

river basins.

Part IV Applied Issues in Ecology

410

desertization and salinization

forests protect...but not if

harvested by clear felling

water is a finite global resource

water – the resource that future

wars will be fought over?

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 410

One response to chronic scarcity of water is to pump it from underground

aquifers – but this often happens faster than the aquifers can be recharged. Such

activity is clearly unsustainable. It is also the main cause of the loss of land from

agriculture due to salinization. The demand for accessible supplies of water for

both agriculture and domestic use has led to the plumbing of the Earth’s river

systems on a vast scale. The number of river dams more than 15 m high increased

from about 5000 in 1950 to 38,000 in the 1990s.

In Chapter 13 we discuss the pollution of water by excreta, and by the

pesticides and fertilizers applied in agriculture. Water that is uncontaminated by

disease agents, nitrates or pesticides is an especially valuable commodity, but con-

tamination occurs all too readily and removing contaminants (e.g. nitrates) is very

expensive. Major dams built to control and conserve water in north and west

Africa create large bodies of open water in which contamination spreads easily;

one consequence has been the rapid spread along rivers of schistomosomiasis

(a flatworm disease of humans), with infection rates rising from less than 10% to

more than 98%.

Maintaining water supplies for human use also creates problems for the con-

servation of wildlife (see Chapter 14). The waterflow in many of the world’s larger

rivers is now very heavily controlled – in some cases little water now reaches the

sea and wetlands have been lost or are at risk. Moreover, silt accumulates up-river

instead of spreading into deltas and flood plains. The results may be catastrophic

for wildlife areas and for human communities as well. For example, there is

reason to believe that failure of silt deposition in the Nile delta (together with

rising sea levels) may cause Egypt to lose up to 19% of its habitable land and

displace 16% of its population within 60 years.

Figure 12.14

Water availability per person from region to region of the globe in 2000. The units are in cubic meters per capita per year.

Chapter 12 Sustainability

411

<1000; catastrophically low

1000–2000; very low

>2000–5000; low

>5000–10,000; medium

>10,000–20,000; high

>20,000; very high

FROM UNITED NATIONS, 2002

contamination and conservation

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 411

12.5 Pest control

Pest control is another area in which the sustainability of agricultural practice

may be threatened. A pest species is simply one that humans consider undesirable.

Estimates suggest that there are around 67,000 species of pests that attack agri-

cultural crops worldwide: 8000 weeds that compete with crops, and 9000 insects

and mites and 50,000 plant pathogens that attack them (Pimentel, 1993). Here

we consider the sustainability of insect pest control in agriculture to illustrate

the types of problems that arise in managed monocultures. We could equally well

have chosen the control of weeds or mollusks, or of the pests and diseases of farmed

livestock, poultry or fish.

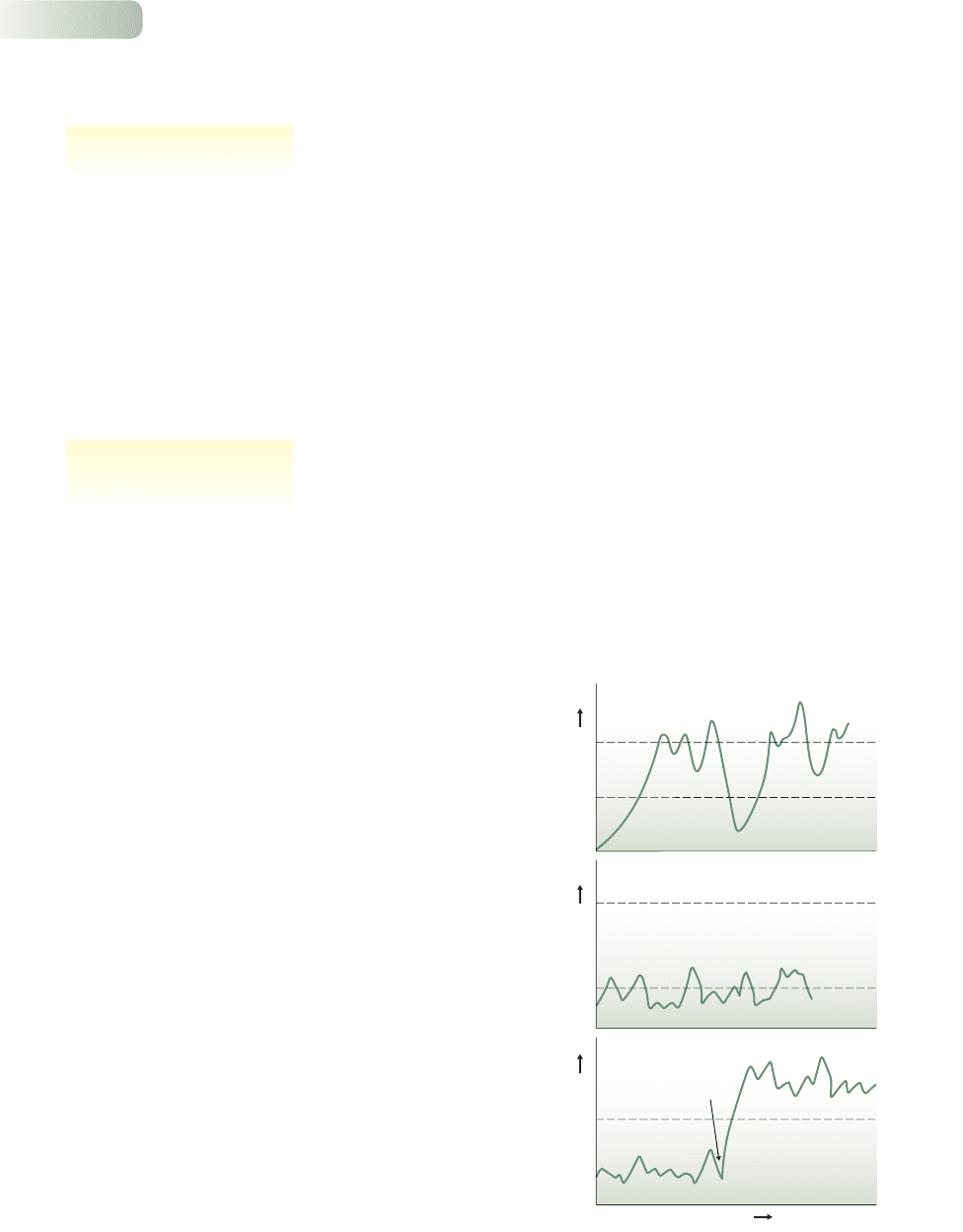

12.5.1 Aims of pest control: economic injury levels and

action thresholds

Economics and sustainability are intimately tied together. Market forces ensure

that uneconomic practices are not sustainable. One might imagine that the aim of

pest control is total eradication of the pest, but this is not the general rule. Rather,

the aim is to reduce the pest population to a level at which it does not pay to

achieve yet more control (the economic injury level or EIL). The EIL for a hypo-

thetical pest is illustrated in Figure 12.15a. It is greater than zero (eradication is

not profitable) but it is also below the typical, average abundance of the species.

If the species was naturally self-limited to a density below the EIL, then it would

never make economic sense to apply ‘control’ measures, and the species could

Part IV Applied Issues in Ecology

412

what is a pest?

Population sizePopulation sizePopulation size

(a)

(b)

(c)

Natural

enemies

removed

Economic

injury level

Economic

injury level

Economic

injury level

‘Equilibrium

abundance’

‘Equilibrium

abundance’

Time

EILs for pests, non-pests and

potential pests

Figure 12.15

(a) The population fluctuations of

a hypothetical pest. Abundance

fluctuates around an ‘equilibrium

abundance’ set by the pest’s

interactions with its food, predators,

etc. It makes economic sense to

control the pest when its abundance

exceeds the economic injury level

(EIL). Being a pest, its abundance

exceeds the EIL most of the time

(assuming it is not being controlled).

(b) By contrast, a species that

cannot be a pest always fluctuates

below its EIL. (c) ‘Potential’ pests

fluctuate normally below their EIL

but rise above it in the absence of

one or more of their natural enemies.

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 412

not, by definition, be considered a ‘pest’ (Figure 12.15b). There are other species,

though, which have a carrying capacity (see Chapter 5) in excess of their EIL,

but have a typical abundance that is kept below the EIL by natural enemies

(Figure 12.15c). These are potential pests. They can become actual pests if their

enemies are removed.

When a pest population has reached a density at which it is causing economic

injury, however, it is generally too late to start controlling it. More important,

then, is the economic threshold (ET): the density of the pest at which action should

be taken to prevent it reaching the EIL. ETs are predictions based on detailed

studies of past outbreaks or sometimes on correlations with climatic records.

They may take into account the numbers not only of the pest itself but also of its

natural enemies. As an example, in order to control the spotted alfalfa aphid

(Therioaphis trifolii) on hay alfalfa in California, control measures have to be

taken at specific times under certain circumstances:

1 In spring when the aphid population reaches 40 aphids per stem.

2 In summer and fall when the population reaches 20 aphids per stem, but the

first three cuttings of hay are not treated if the ratio of ladybirds (beetle

predators of the aphids) to aphids is one adult per 5–10 aphids, or three

larvae per 40 aphids on standing hay, or one larva per 50 aphids on stubble.

3 During winter when there are 50–70 aphids per stem (Flint & van den

Bosch, 1981).

12.5.2 Problems with chemical pesticides, and

their virtues

A pesticide gets a bad name if, as is usually the case, it kills more species than

just the one at which it is aimed. It may then become a pollutant (see Chapter 13).

However, in the context of the sustainability of agriculture, the bad name is espe-

cially justified if it kills the pest’s natural enemies and so contributes to undoing

what it was employed to do. Thus, the numbers of a pest sometimes increase

rapidly some time after the application of a pesticide. This is known as target

pest resurgence and occurs when treatment kills both large numbers of the pest

and large numbers of their natural enemies. Pest individuals that survive the

pesticide or that migrate into the area later find themselves with a plentiful food

resource but few, if any, natural enemies. The abundance of the pest population

may then explode.

The after effects of applying a pesticide may involve even more subtle reactions.

When a pesticide is applied, it may not be only the target pest that resurges.

Alongside the target are likely to be a number of potential pest species that had

been kept in check by their natural enemies (Figure 12.15c). If the pesticide

destroys these, the potential pests become real ones – and are called secondary

pests. A dramatic example concerns the insect pests of cotton in Central America.

In 1950, when mass dissemination of organic insecticides began, there were

two primary pests: the Alabama leafworm and the boll weevil (Smith, 1998).

Organochlorine and organophosphate insecticides were applied fewer than five

times a year and initially had apparently miraculous results – crop yields soared.

By 1955, however, three secondary pests had emerged: the cotton bollworm,

the cotton aphid and the false pink bollworm. The pesticide applications rose

Chapter 12 Sustainability

413

target pest resurgence and

secondary pest outbreaks

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 413

to 8–10 per year. This reduced the problem of the aphid and the false pink

bollworm, but led to the emergence of five further secondary pests. By the 1960s,

the original two pest species had become eight and there were, on average,

28 applications of insecticide per year. Clearly, such a rate of pesticide applica-

tion is not sustainable.

Chemical pesticides lose their role in sustainable agriculture if the pests evolve

resistance. The evolution of pesticide resistance is simply natural selection in

action (see Chapter 2). It is almost certain to occur when vast numbers of a genetic-

ally variable population are killed. One or a few individuals may be unusually

resistant (perhaps because they possess an enzyme that can detoxify the pesticide).

If the pesticide is applied repeatedly, each successive generation of the pest

will contain a larger proportion of resistant individuals. Pests typically have a

high intrinsic rate of reproduction, and so a few individuals in one generation

may give rise to hundreds or thousands in the next, and resistance spreads very

rapidly in a population.

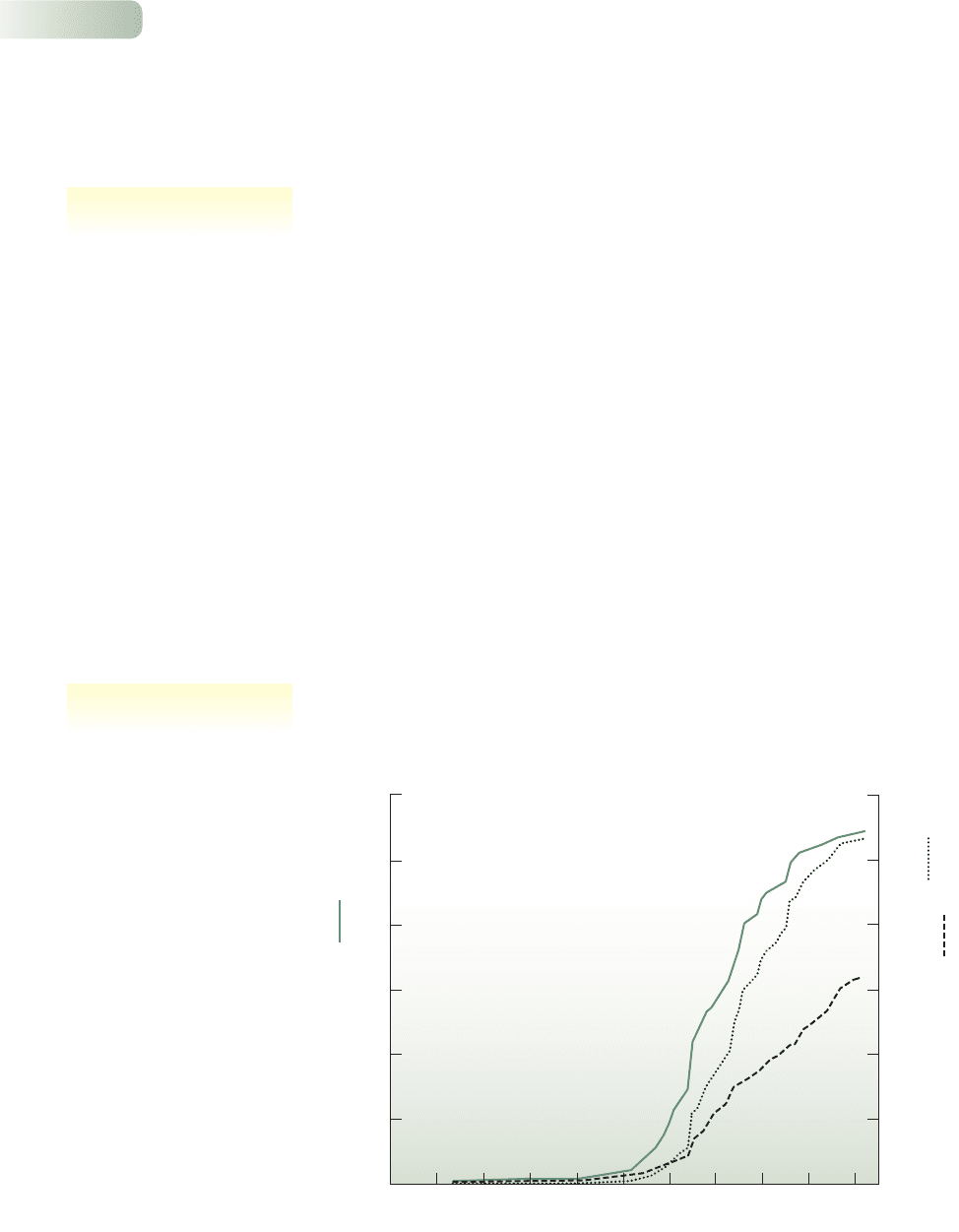

This problem was often ignored in the past, even though the first case of

DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) resistance was reported as early as

1946 (houseflies in Sweden). The current scale of the problem is illustrated in

Figure 12.16, which shows the exponential increase in the numbers of inverteb-

rates that have evolved resistance and in the number of pesticides against which

resistance has evolved. Resistance has been recorded in every family of arthropod

pest (including dipterans such as mosquitoes and houseflies, as well as beetles, moths,

wasps, fleas, lice, moths and mites) as well as in weeds and plant pathogens. Take

the Alabama leafworm (see above), a moth pest of cotton, as an example. It has

developed resistance in one or more regions of the world to aldrin, DDT, dieldrin,

endrin, lindane and toxaphene.

If chemical pesticides brought nothing but problems, however – if their use was

intrinsically and acutely unsustainable – then they would already have fallen

out of widespread use. This has not happened. Instead, their rate of production

Part IV Applied Issues in Ecology

414

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

0

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Cumulative number of cases of resistance

(species × pesticides) ( )

Year

Cumulative number of arthropod species ( )

and compounds ( )

Figure 12.16

Global increases in the number of

arthropod pest species reported to

have evolved pesticide resistance

and in the number of pesticide

compounds against which resistance

has developed. Each pest, on

average, has evolved resistance

to more than one pesticide,

so there are now more than

2500 cases of evolution of

resistance (pests × compounds).

FROM MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY’S DATABASE

OF ARTHROPODS RESISTANT TO PESTICIDES,

WWW.PESTICIDERESISTANCE.ORG/DB/; © PATRICK

BILLS, DAVID MOTA-SANCHEZ & MARK WHALON

evolved resistance...

. . . but pesticides work

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 414

has increased rapidly. The ratio of cost to benefit for the individual producer has

remained in favor of pesticide use: they do what is asked of them. In the USA,

insecticides have been estimated to benefit the agricultural producer to the tune

of around $5 for every $1 spent (Pimentel et al., 1978).

Moreover, in many poorer countries, the prospect of imminent mass starva-

tion, or of an epidemic disease, are so frightening that the social and health

costs of using pesticides have to be ignored. In general the use of pesticides is

justified by objective measures such as ‘lives saved’, ‘economic efficiency of food

production’ and ‘total food produced’. In these very fundamental senses, their

use may be described as sustainable. In practice, sustainability depends on con-

tinually developing new pesticides that keep at least one step ahead of the pests

– pesticides that are less persistent, biodegradable and more accurately targeted

at the pests.

12.5.3 Biological control

Outbreaks of pests occur repeatedly and so does the need to apply pesticides.

But biologists can sometimes replace chemicals by other tools that do the same

job and cost a great deal less. Biological control involves the manipulation of

the natural enemies of the pests. There are three main types of biological control:

importation, conservation and inoculation biological control.

The first is the importation of a natural enemy from another geographic area

– often the area where the pest originated. The objective is for the control agent

to persist and thus maintain the pest below its economic threshold for the fore-

seeable future. This is a case of a desirable invasion of an exotic species and is

often called classical biological control.

The most classic example of ‘classical’ biological control concerns the cottony

cushion scale insect (Icerya purchasi), discovered as a pest of Californian citrus

orchards in 1868. By 1886 it had brought the citrus industry to its knees. Species

that colonize a new area may become pests because they have escaped the con-

trol of their natural enemies. Importation of some of these natural enemies is

then, in essence, restoration of the status quo. A search for natural enemies led

to the importation to California of two candidate species. The first was a para-

sitoid, a two-winged fly (Cryptochaetum sp.) that laid its eggs on the scale

insect, giving rise to a larva that consumed the pest. The other was a predatory

ladybird beetle (Rodolia cardinalis). Initially, the parasitoids seemed to have dis-

appeared, but the predatory beetles underwent such a population explosion

that, amazingly, all scale insect infestations in California were controlled by

the end of 1890. Although the beetles have usually taken the credit, the long-

term outcome has been that the beetles keep the scale insects in check inland,

but Cryptochaetum is the main control near the coast (Flint & van den Bosch,

1981). The economic return on investment in biological control was very high

in California and the ladybird beetles have subsequently been transferred to

50 other countries.

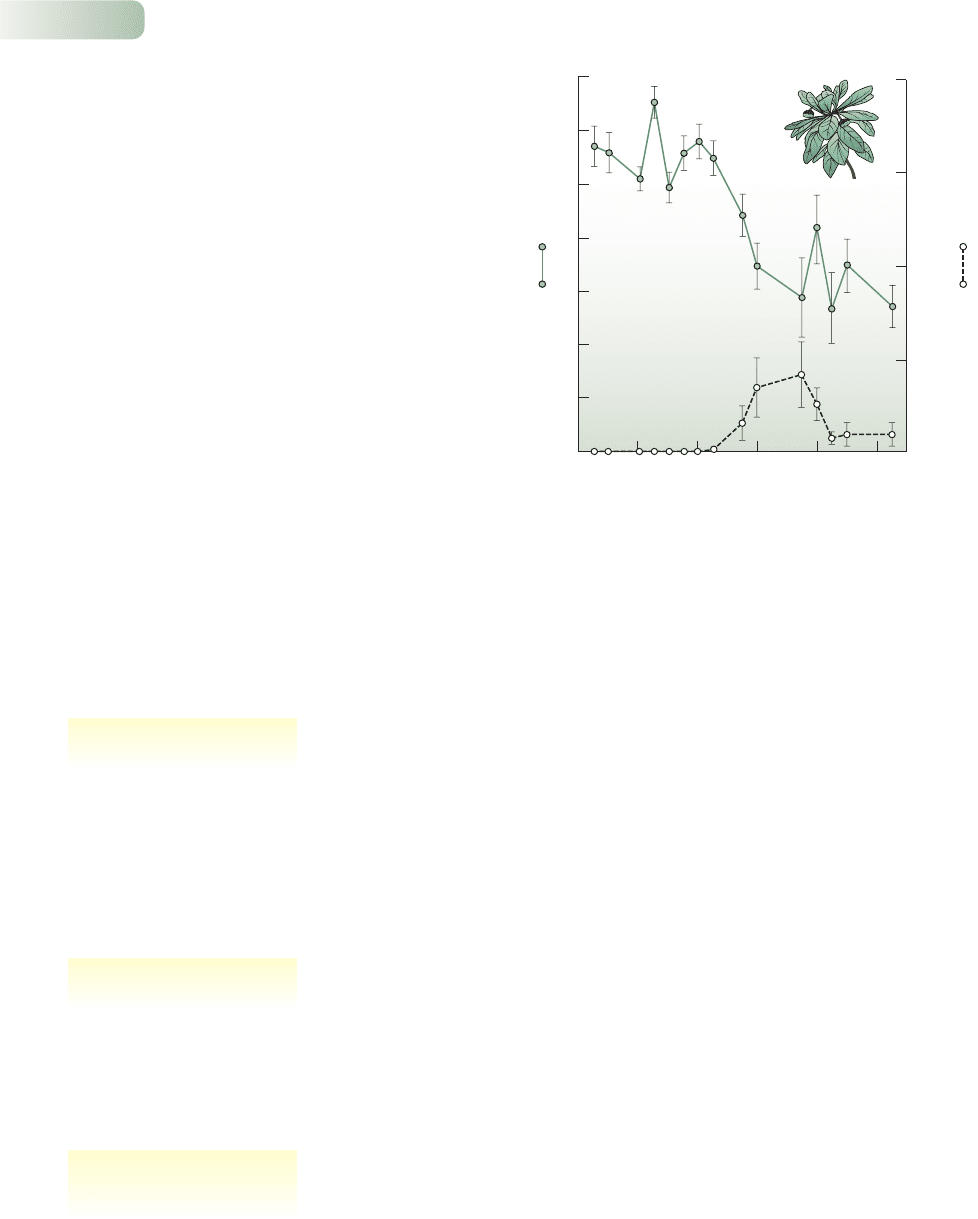

Another invasive scale insect was driving to extinction the national tree of the

small South Atlantic island of St. Helena (the last home of another famous invader

– Napoleon Bonaparte). Only 2500 St. Helena gumwoods (Commidendrum

robustum) remained in 1991 as a result of attack by the South American scale

insect Orthezia insignis. Fowler (2004) estimated that all remaining individuals of

Chapter 12 Sustainability

415

three types of biological control

importation biological control

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 415

this rare tree would have been dead by 1995. Another ladybird beetle saved the

day. Hyperaspis pantherina was cultured and released on St. Helena in 1993 and

as its numbers increased there was a corresponding 30-fold decrease in scale insect

numbers (Figure 12.17). No scale outbreaks have been reported since 1995 and

release of the ladybirds has been discontinued because the ladybird population

is maintaining itself at low density in the wild, as good importation biocontrol

agents should.

In contrast to importation biological control, conservation biological control

involves manipulations to increase the equilibrium density of natural enemies that

are already native to the region where the pest occurs. In the case of the aphid

pests of wheat (e.g. Sitobion avenae), predators that specialize on aphids include

ladybirds and other beetles, heteropteran bugs, lacewings (Chrysopidae), fly

larvae (Syrphidae) and spiders. Many of these natural enemies spend the winter

in grassy boundaries at the edge of wheat fields, from where they disperse to

reduce aphid populations around field edges. Farmers can protect grass habitat

around their fields and even plant grassy strips in the interior to enhance these

natural populations and the scale of their impact on the pests.

A third class of biological control, inoculation biological control is widely prac-

ticed in the biological control of pests in glasshouses, where crops are removed,

along with the pests and their natural enemies, at the end of the growing season.

Two particularly important natural enemies used for inoculation are Phytoseiulus

persimilis, a mite that preys on the spider mite Tetranychus urticae, a pest of

roses, cucumbers and other vegetables, and Encarsia formosa, a chalcid parasitoid

wasp of the whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum, a pest in particular of tomatoes

and cucumbers.

Insects have been the main agents of biological control against both insect

pests and weeds. Table 12.1 summarizes the extent to which they have been used

and the proportion of cases where the establishment of an agent has greatly

reduced or eliminated the need for other control measures.

Part IV Applied Issues in Ecology

416

( )

( )

2.8

2.4

2.0

1.6

1.2

0.8

0.4

0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Sampling date

May

1993

Sept

1993

Jan

1994

May

1994

Sept

1994

Jan

1995

Numbers of H. pantherina (log n+1)

Numbers of O. insignis (log n+1)

Figure 12.17

Mean numbers (± SE, log scale), on continuously monitored 20

cm branchlets of 30 randomly selected gumwood trees, of the

pest scale insect Orthezia insignis and its biological control agent,

the ladybird Hyperaspis pantherina. Mean scale insect numbers

dropped from more than 400 adults and nymphs (in September

1993) to fewer than 15 (in February 1995) when sampling ceased.

Mean ladybird numbers increased from January to August 1994,

coinciding with an obvious decline in scale insects, before ladybird

numbers declined again. The highest recorded numbers of

ladybirds were 1.3 adults and 3.4 larvae per 20 cm branchlet.

AFTER FOWLER 2004

conservation biological control

control by inoculation

biological control: excellent

when it works...

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 416

Biological control may appear to be a particularly environmentally friendly

approach to pest control, but examples have come to light where even carefully

chosen, and apparently successful, introductions of biological control agents have

impacted on non-target species (Pearson & Callaway, 2003). Cactoblastis moths,

which were introduced to Australia and were dramatically successful at con-

trolling exotic cactuses, were accidentally introduced to Florida where they

have been attacking several native cacti (Cory & Myers, 2000). Similarly, a seed-

feeding weevil (Rhinocyllus conicus), introduced to North America to control

exotic Carduus thistles, attacks several native thistles and has adverse impacts

on populations of a native picture-winged fly (Paracantha culta) that feeds on

the thistle seeds (Louda et al., 1997). Such ecological effects need to be better

evaluated in future assessments of potential biocontrol agents.

12.6 Integrated farming systems

The desire for sustainable agriculture has increasingly led to more ecological

approaches to food production, which are often given the label ‘integrated farm-

ing systems’. Part of this, and something that preceded it historically, is a similar

approach to pest control: integrated pest management (IPM).

IPM is a practical philosophy of pest management. It combines physical control

(for example, simply keeping pests away from crops), cultural control (for example,

rotating the crops planted in a field so pests cannot build up their numbers over

several years), biological and chemical control and the use of resistant crop

varieties. It has come of age as part of the reaction against the unthinking use of

chemical pesticides in the 1940s and 1950s.

IPM is ecologically based but uses all methods of control – including chemicals,

where appropriate. It relies heavily on natural mortality factors, such as natural

enemies and weather, and seeks to disrupt them as little as possible. It aims to

control pests below an economically damaging level (the EIL), and it depends on

monitoring the abundance of pests and their natural enemies and using various

control methods as complementary parts of an overall program. IPM therefore

calls for specialist pest managers or advisers. Broad-spectrum pesticides in par-

ticular, although not excluded, are used only very sparingly, and if chemicals are

used at all it is in ways that minimize the costs and quantities used. The essence

of the IPM approach is to make the control measures fit the pest problem, and

no two pest problems are the same – even in adjacent fields.

Chapter 12 Sustainability

417

. . . but sometimes non-target

organisms are affected

Table 12.1

The record of insects as biological control agents against insect pests and weeds.

AFTER WAAGE & GREATHEAD, 1988

INSECT PESTS WEEDS

Control agent species 563 126

Pest species 292 70

Countries 168 55

Cases where agent has become established 1063 367

Substantial successes 421 113

Successes as a percentage of establishments 40 31

integrated pest management

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 417

The caterpillar of the potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella) commonly

damages crops in New Zealand. An invader from a warm temperate subtropical

country, it is most devastating when conditions are warm and dry (i.e. when the

environment coincides closely with its optimal niche requirements). There can be

as many as 6–8 generations per year and different generations mine leaves, stems

and tubers. The caterpillars are protected both from natural enemies (parasitoids)

and insecticides when in the tuber, so control must be applied to leaf-mining

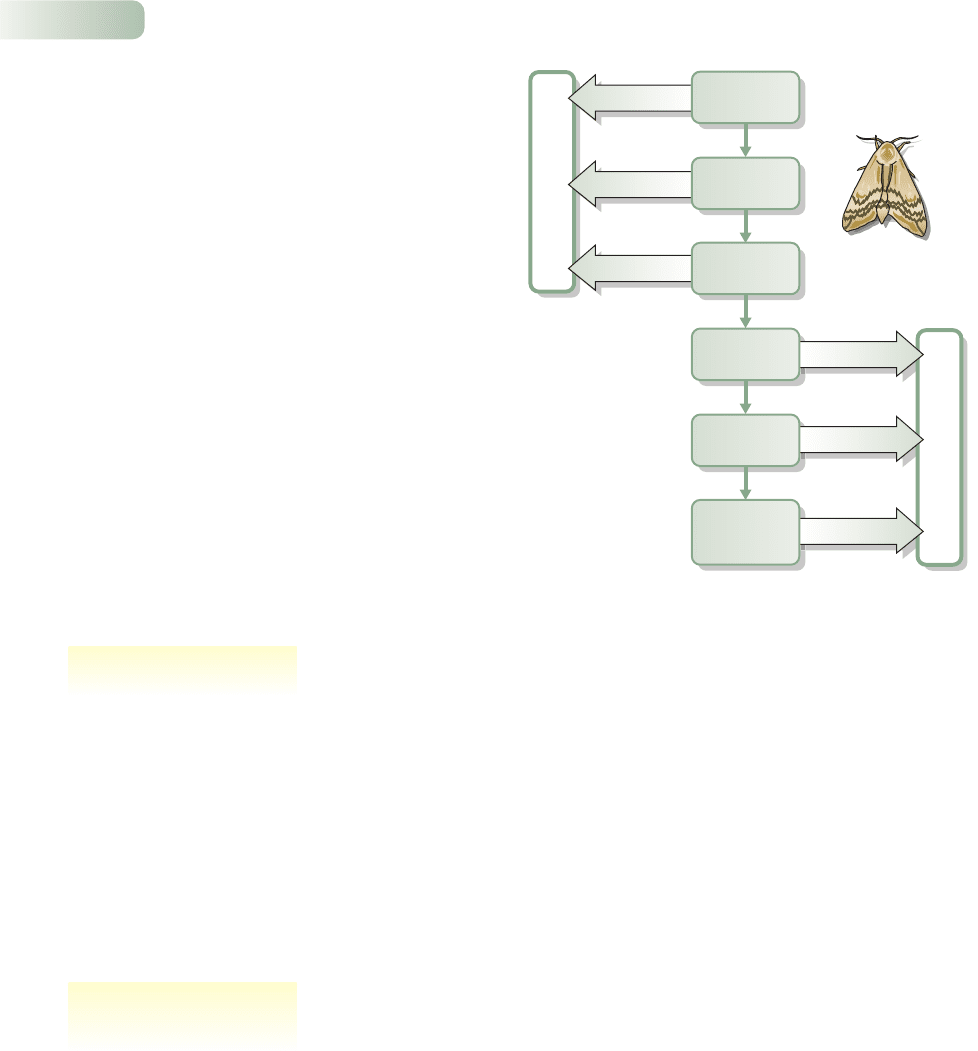

generations. The IPM strategy for the potato tuber moth (Herman, 2000) involves

monitoring (female pheromone traps, set weekly from midsummer, are used to

attract males, which are counted), cultural methods (the soil is cultivated to pre-

vent soil cracking, soil ridges are molded up more than once and soil moisture is

maintained), and the use of insecticides, but only when absolutely necessary (most

commonly the organophosphate, methamidophos). Farmers follow the decision

tree shown in Figure 12.18.

It has increasingly become apparent, in an agricultural context at least, that

implicit in the philosophy of IPM is the idea that pest control cannot be isolated

from other aspects of food production and is especially bound up with the means

by which soil fertility is maintained and improved. Thus, a number of programs

have been initiated to develop and put into practice sustainable food produc-

tion methods that incorporate IPM, including not only IFS (integrated farming

systems) but also LISA (low input sustainable agriculture) in the USA and LIFE

(lower input farming and environment) in Europe (International Organisation

for Biological Control, 1989; National Research Council, 1990). All share a com-

mitment to the development of sustainable agricultural systems.

Part IV Applied Issues in Ecology

418

S

P

R

A

Y

Possible to

use cultural

controls?

If not possible

Molds? Breaking open

PTM

population?

Increasing

Prevailing

weather?

Cool/wet

Time of

year?

Pre February

Growth stage

of crop?

Pre tuber

D

O

N

O

T

S

P

R

A

Y

Figure 12.18

Decision flow chart for the integrated pest management of potato

tuber moths (PTM) in New Zealand. Boxed phrases are questions

(e.g. ‘Growth stage of crop?’), words in arrows are the farmer’s

answers to the questions (e.g. ‘Pre tuber’) and the recommended

action is shown in the vertical boxes (e.g. ‘Do not spray’). Note that

February is late summer in New Zealand.

AFTER HERMAN, 2000

IPM for the potato tuber moth

integrated farming systems:

LISA, IFS and LIFE

9781405156585_4_012.qxd 11/5/07 15:01 Page 418