Wakeman Rosemary. The Heroic City: Paris, 1945-1958

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

116 | chapter three

newspaper and television coverage. The reporting of street demonstrations

on television newscasts is a particularly risky terrain for historians to maneu-

ver. Radiodiffusion télévision française (RTF) was government controlled.

News broadcasts remained exceptionally conformist and followed govern-

ment policy on the legitimacy of spatial access and use of the public domain.

Ostensibly tolerated rituals such as the May Day and July 14 parades and

the student monôme du bac, or rag parade, received privileged coverage by

visual media, while more explicit political demonstrations and strikes rarely

appeared on either film newsreels or television sets. When they did, the nar-

rative and visual sequence tended to portray first the gathering, then the

inevitable breakdown into violence, and finally the successful crackdown by

police forces.

20

Highly popular photoessay magazines such as Paris Match

tended to follow the same logic. Taking into account these significant biases,

the combination of newspaper and visual coverage can nevertheless provide

a fuller picture of political activity on the streets of Paris. They also provide

valuable insight into the ways in which visual media were appropriated by

protesters themselves for their own purposes. The city’s topography was

heightened as a multilayered, fluid political landscape occupied and enriched

by an assortment of political voices.

Through the mid-1950s political demonstrations in Paris were generally

prohibited, so participants in overt protests risked incendiary confrontations

with law enforcement. The communists also walked a fine line between op-

position to the bourgeois Fourth Republic and cooperation in the “battle for

production” and the reconstruction of France. Up to 1947 they held ministerial

positions. Hostility was restrained. As a result, a myriad of cultural practices

served as a proxy for political struggle. Benign neighborhood social events

and time-honored ceremonies and anniversaries were occasions for reasserting

political power in the street. They were strategies of action and representation.

This tactic relied on the reinvention of the memory of place and the political

rituals that had formed the framework of neighborhood life before the ca-

tastrophe of the war. For the Left (especially the communists), the founding

myths of Paris were the 1789 and 1848 Revolutions and the 1871 Paris Com-

mune. This ideal of the people manning the barricades was rediscovered in

the Popular Front and in the Resistance. Indeed, the myth of the Liberation

was that Parisians had emerged from the oppression of the années noires and

would regain the liberty of the prewar years. This historic past provided coher-

ence and legitimacy and wreathed the working classes, the true people, in the

public space and confrontation | 117

city’s revolutionary heritage. In October 1944 the Communist Party invited

Parisians to commemorate the deaths of Paul Vaillant-Couturier, Henri Bar-

busse, and the martyrs of the war and Liberation with a time-honored march

to the Mur des Fédérés at Père Lachaise Cemetery. One of the first political

demonstrations after the Liberation and attended, according to L’Humanité,

by over 250,000 people,

21

it inaugurated a cenotaph to the Left’s martyred

heroes. The ceremony immediately reactualized the symbolic place and glo-

rious memory of working-class struggle and placed the communists in the

forefront of political expression in the streets. The PCF even took charge of

the capital’s Armistice Day celebration at the Arc de Triomphe on November

11, 1944, which went on without de Gaulle or any other official government

representation. The May 1 Labor Day march to the Mur des Fédérés in 1945

celebrated the victory of the communists in the municipal elections, while

the traditional May 27 march in commemoration of the fédérés of the Paris

Commune honored wartime deportees. It drew hundreds of thousands. The

performance quality of these events and the staging of wartime tragedy were

apparent in the spectacle of deportees, who marched in their “odious blue

and gray costumes, head shaved, with grave faces . . . the women wore their

miserable dresses, but their faces showed they had refound Paris, fraternal

emotion and the shared élan of a people.”

22

Huge crowds laid wreaths on the

tombs of “the heroes of the Commune and their descendants, the martyrs of

the Liberation” in a fusion of political imagery. They proclaimed, according

to the Confédération générale du travail (CGT) labor-union newspaper La

Vie ouvrière, “their faith in the France of yesterday and tomorrow by their

willingness to act, to work together for the immediate reconstruction of the

country.”

23

A July 31 pilgrimage organized by the Socialist Party to the Mur

des Fédérés and the Panthéon to commemorate the assassination of Jean Jaurès

also drew tens of thousands. What distinguishes these parades, pilgrimages,

political festivals, and commemorations is, first, their quantity, and second,

the tens of thousands, in some cases hundreds of thousands, of people who

took part. The sheer number of events and the exceptional levels of participa-

tion in public ceremonies far exceeded those in the years before the war. This

massively claimed “right to the city” was associated with a people’s arrival

at power and the ceremonial posturing that went with it. Armistice Day, the

commemoration of the May 8 wartime victory and of the historic leaders of the

Left, and the homage to the Resistance and to wartime martyrs and returning

prisoners of war were all conceived as spatial and political spectacle.

118 | chapter three

The annual May Day and July 14 marches and the commemoration of

the February 1934 political crisis (which was interpreted as a defense against

a fascist coup d’état) were the most sustained political theater through the

mid 1950s. The most sanctified route for these parades was between the

place de la Bastille and the place de la Nation. This topography was pierced

with historical meaning and political possibilities that were magnified in the

context of the immediate postwar period. The May Day caravan from the

Bastille to the place de la Nation organized by the PCF privileged the heritage

of revolutionary Paris with the slogan “May 1, 1934—May 1, 1946 at Paris.”

Led by top communist and socialist officials, huge masses of people marched

through the streets on foot and on bicycle, carrying banners, insignias, and

placards celebrating the “fête de l’espoir” and “rénové.” The parade route

was turned into a huge open-air traveling carnival and political rally. These

were expressions of solidarity, national sovereignty, and a people allied in the

great work of reconstruction. Enormous placards heralded the manifestation

populaire. They led a procession of highly stylized banners and floats that

carried on the tradition of constructivist street decor. Folkloric groups and

populist organizations displayed their streamers, flags, insignia, and badges

in a festival of civic right and spatial appropriation.

24

Such was the moral authority of the working classes at the war’s end that

processions veered out of this archetypal working-class territory of eastern

Paris to appropriate official sites of political power in Paris. In the case of the

July 14, 1946, parade (the first after the war), the French state’s official military

pageant shifted from its normal trajectory down the Champs-Élysées to the

place de la Bastille, where it joined ranks with the victorious working classes.

The parade’s destination was the old place de Grève, the time-honored square

in front of the Hôtel de Ville that would be ceremoniously “conquered” by the

city’s people. Les Actualités françaises filmed the historic procession in all its

patriotic regalia. The clip begins with quintessential shots of the city’s great

monuments floodlit at night—a glorious site in itself after years of wartime

darkness. The appropriation of historical imagery is arresting: wax figures

depicting French Revolutionary heroes introduce images of the celebration.

The procession of the “Armée nouvelle” begins at the place de la Bastille, in

honor of “the first cry of freedom by the French people.” The public pageant

is led by a grandiose défilé populaire: men and women, many of them dressed in

traditional costumes, march amid a sea of flags, banners, and elaborate floats.

Soldiers and colonial troops file by in ceremonial ranks and tanks parade in

public space and confrontation | 119

a staging of French military might. And “for the first time,” workers from

the armaments factories join the official procession along with Resistance

cells now triumphantly on display with their leaders. In a similar celebratory

appropriation of official political space, Les Actualités françaises captured the

1947 May Day parade as it wound from the place de la République to the

place de la Concorde.

25

These film images reveal a self-conscious arrival at

power and sovereignty, with all of the posturing and monumental ceremony

that goes with it. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the parade routes

in a reiteration of the Liberation’s retaking of the city. The people of Paris

were the main actors in this public theater of the street that included its own

dramatic conflict. The latter celebration took place just a few days before the

expulsion of the communists from government. According to Combat, the

communist contingents in the parade were cheered wildly, while the Social-

ists were admonished for their lack of political unity.

26

The start of the cold war and the expulsion of the PCF from government

in 1947 radically intensified this political drama playing out on the streets

of the capital. Communist ministers were summarily dismissed from Paul

Ramadier’s government on May 4. The PCF was driven out of a number of

mayoral seats throughout its base in the city’s working-class districts. The

mayors of the 11th and 20th arrondissements were dismissed. Mayors in

the 3rd, 13th, 18th, and 19th arrondissements were later sacked, along with

twenty-five communist mayoral adjuncts.

27

Political protests were subject

to more and more restrictions. In the midst of the November 1947 strike

waves, they were banned altogether for the first time since the Liberation.

Commemoration parades became the only political activity negotiable with

police authorities, and even political speeches at these events were officially

barred. The parades became a form of subversive art and political masquer-

ade. In 1948 alone the party organized nine commemorative corteges that

rallied from 100,000 to a million participants.

28

Especially along the hallowed

ground from the Bastille to the place de la Nation, the parades were among

the few authorized opportunities for the Communist Party and labor unions

to flex their political muscle in public space without recourse to dangerous

civil disobedience. As political theater the marches were “messy” paradoxi-

cal political events, both conservative and radical in content. They acted as a

mechanism of political protest, yet did not ostensibly threaten to undermine

the country’s fragile stability. The throngs on parade through the working-

class stronghold were popular fêtes. They were political festivals that trig-

120 | chapter three

gered social remembrance and association with free action and subversion.

They were a form of mockery, derision, and subterfuge. The “play-acting”

of revolution and the performance of social roles could be genuine or spuri-

ous, valid or phony. One could make the argument that this visual narrative

created a mythology, a hyperreal spectacle that was an illusion of reality

and actually hid social relations. But as a type of militant pedestrianism, it

acted ostensibly as a claim to accessibility in the public sphere. This practical

theater of protest was saturated with complexity and contradiction. Led by

Communist Party and labor leaders, workers proudly carried their union and

factory banners along with posters proclaiming the political slogans of the

moment. There was a free intermingling of festival and protest, of the playful

and the serious. The parade became a political prank. Ice cream vendors and

street merchants selling souvenirs worked the crowds along the parade route

in what increasingly took on the atmosphere of a carnival or fête foraine. In

newspaper metaphors used to describe the processions, the crowds surge,

stream, and flow. There is a sense of fluidity in space, of sensuousness and

provocation that the historian David Glassberg links to a thinly veiled sexual

imagery.

29

The crowds seethe with political passion and righteousness. The

festivities end with fiery speeches by left-wing luminaries at the place de la

Nation. The 1948 and 1949 marches commemorating February 1934 both

drew some 25,000 spectators. In 1951 the event still attracted a crowd of

20,000, according to the police count. The multiplicity of corteges, marches,

and symbolic demonstrations of power in the streets of the city infinitely

appropriated and reappropriated the spaces of the city. They wound along

hallowed routes and acted out the reemergence of the peuple as a political

and civic force, forming a topographic bond imbued with a sense of political

rebelliousness and social power.

One reason to interpret this political spectacle as more than pretense is

that it was not unaccompanied. The multiplicity of industrial actions, walk-

outs, and demonstrations kept the streets of Paris in an habitual state of agi-

tation. Protests against persistent penury and unfair food rationing, against

low wages and salary disparities between Paris and the suburbs, against rising

prices and shyster opportunists, fueled the battle for spatial and political le-

gitimacy. For example, in both 1949 and 1950, wounded war veterans staged

protest marches at the capital’s official sites of political power, moving down

the Champs-Élysées from the place de la Concorde and the Opéra. Giving

voice to their demands for more public aid, they rolled makeshift wheelchairs

public space and confrontation | 121

and handicap pushcarts in front of television cameras for full effect as crowds

watched. In November 1946 a crowd estimated at 100,000 converged on the

slaughterhouse at La Villette to protest rising prices and demand the immedi-

ate arrest of the “meat gangsters and muggers of La Villette.” Danielle Tarta-

kowsky points to the ritualistic forms of these protests, which harked back to

the atmosphere of a fête champêtre or even “carnivelesque forms inherited from

the Popular Front.”

30

They were, in other words, doubly coded festivals in

which play erupts into political threat. The most important followed a specific

pattern of populist spectacle that accentuated their incendiary and arousal

qualities: an angry, emotionally incited crowd moving toward riot, the party

or labor unions channeling passions into disciplined protest, the breakdown

into violence, the bloodshed or, even worse, deaths, with the aftermath of

more protests and funeral marches. In September 1948 ten thousand workers

in the SNECMA plants walked out on strike. Masses of picketers fought with

police in front of company headquarters on the boulevard Haussmann. Feb-

ruary and March 1950 saw strikes at the Renault factory, by public transport

workers, then by the city’s gas and electricity employees. Bomb explosions

rocked the Paris branches of the North European Commercial Bank and the

Bank of Worms. The success during August 1953 of the massive public-sector

strike waves over retirement and promotion benefits surprised even union of-

ficials. The spontaneous groundswell of protests during the traditional month

of vacation paralyzed Paris as well as the rest of France and demonstrated

the people’s apprehension about bread-and-butter issues. Enormous crowds

of striking workers blocked entrances to the city’s railroad stations and held

outdoor meetings. They took over post offices and public buildings. Thou-

sands jammed the Bourse de Travail on the rue du Château d’Eau near the

place de la République. The army was brought in to maintain public order

and carry out essential public services. For weeks the spaces of Paris looked

as though they were under siege.

31

The most politically charged and violent postwar demonstrations were

the massive strike movements of 1947, the Ridgway riots of 1952, the bru-

tal battles of July 14, 1953, and the anticommunist protests of 1956. The

1947 strike waves were instigated by a cabal of social and political ten-

sions. The working-class standard of living had risen at the Liberation to

around 60 percent of its prewar level, and then to 80 percent in late 1945.

By May 1947 it had fallen back to half the prewar level.

32

People were put-

ting in longer hours with little possibility of achieving any real gains. The

122 | chapter three

refusal by the socialist prime minister, Paul Ramadier, to respond to this

emergency and instead to freeze wages infuriated workers and aggravated

social hostilities. Protest marches organized by labor unions converged on

the Champs-de-Mars in a demonstration of their power and discipline and

to defend “their right to life, the Republic, and democracy.” Wildcat work

stoppages demanding pay increases broke out in a variety of industries. In

April workers in the Say Sugar Refinery in the 13th arrondissement went

out on strike. Then it was the turn of the workers at the Grands Moulins

flour mills, and next the city’s laundry workers. The strike at Renault in

April was the largest. Then, on May 4, Maurice Thorez and the communist

ministers were expelled from Ramadier’s government. The PCF reacted to

its marginalization by calling the rank and file out of the factories and into

the streets. Workers in the aeronautic and automobile plants joined the

Renault strike. Yet despite the inflammatory rhetoric and tense standoffs,

the strike waves that hit in November 1947 still retained their customary

tone and practice. Led again by workers in the Renault factory, nearly all

of the metallurgical industry went out on strike to demand 25 percent pay

increases. By November 22 front-page headlines in L’Humanité reported

70,000 workers on strike, with 30,000 young compagnons on the march to

a massive rally at Vél’ d’Hiv’. They filled the streets around the stadium,

appropriating a space already filled with police by breaking into traditional

songs of insurrection amid clashes. One worker and former résistante was

killed and hundreds wounded in a pitched battle with anticommunists

around the Salle Wagram, near the place de l’Étoile. Military reservists and

riot squads were called out to protect the National Assembly and patrol the

streets. Appropriating revolutionary imagery, young workers from the Cit-

roën plant were described as arriving “still covered in blood from the blows

they received in the magnificent afternoon battle against the police, against

the mobile guards launched by the enemy of the people.” They battled “for

a young, happy and strong France.” Workers occupying the Citroën factory

held off police while singing the “Marseillaise.”

33

The strident calls for an end to social injustices that reverberated across

Paris were rolled into anti-American and cold war hyperbole. Communist

demonstrations against the Marshall Plan ended in violent clashes, while

parades against “coca-colonisation” spilled into the streets. The PCF inten-

sified efforts to block what they derided as American militarism not only

because of the wars in Indochina and Korea, but also to prevent the rearm-

public space and confrontation | 123

ing of the German Federal Republic. Fear of German military rearmament

was widespread on the Left and was equated with the rise of Nazi Germany.

In 1950 violence broke out along the Champs-Élysées during a communist

protest against Le Figaro’s serial publication of a memoir by the former SS

officer Otto Skorzeny. Camera crews climbed onto automobile rooftops to

film the police charges into the crowds and the ensuing fracas as protesters

tore apart the bistro chairs and tables to use as projectiles.

34

The January

1951 visit to Paris by Dwight D. Eisenhower, dubbed the “General of Ger-

man Rearmament” by the Left, was welcomed with a call for patriotic strikes

and protests by the Paris section of the PCF while thousands marched for

peace down the Champs-Élysées. The arrival in Paris of German Chancellor

Konrad Adenauer (accompanied by General Hans Speidel) in late November

1951 brought more street protests and violent clashes. Although the march

was banned, tens of thousands paraded along the triangle between the place

de la République, the place de l’Opéra, and the gare Saint-Lazare. More

than seven thousand police were massed along the Champs-Élysées. Street

fighting and smaller public protests took place in the northern and eastern

districts, interrupting traffic, with cars horns blaring in support or in annoy-

ance. Thousands were rounded up and arrested.

Although politically marginalized, the PCF continued to wear the mantle

of patriotism by launching a powerful version of the peace movement in the

capital’s streets. It was a single-issue campaign meant to mobilize the French

nation and distinguish it as independent from U.S. imperialism and acting

in the best interests of the future. Because the socialists were aligned with

Atlanticism, the communists essentially monopolized what proved to be an

immensely popular movement against atomic weapons and the cold war. The

years 1948 and 1949 saw some seven peace demonstrations organized by the

communists and the Union de la jeunesse républicaine française (Union of

Young French Republicans, or UJRF) on the interior boulevards. The cen-

trality of the location marked them as essentially national in context. They

were meant to sway French public opinion against the cold war, as was the

PCF’s 1949 World Peace Congress in Paris. The Stockholm Appeal launched

by Frédéric Joliot-Curie and the communist-sponsored World Congress of

Partisans of Peace in March 1950 sped up the momentum. The campaign

collected millions of signatures demanding the banning of all atomic weap-

ons as a crime against humanity. The peace movement was played out at

the PCF’s populist base. Peace rallies were held regularly in various public

124 | chapter three

venues such as the Stade de Buffalo and the Salle Wagram, in suburban

factories and communist-held municipalities. In 1951 local peace confer-

ences were organized in twenty-nine locations in the communist-dominated

arrondissements and suburban towns. L’Humanité called them “dozens of

popular little assemblies in the street, laboratories, apartment buildings and

places of work.”

35

At the Veteran’s Day celebrations in the 15th arrondisse-

ment on November 11, 1953, the communists called for the neighborhood’s

women, “all the mothers worried over the threat of war,” to rally against the

rearming of Germany, the Bonn Accords, and the Treaty of Paris.

36

Initially

none of these activities seriously challenged police-regulated access to public

space, nor did they risk violent engagement or a destabilization of the streets.

However, the atmosphere changed when the PCF began to launch a more

aggressive policy of confrontation. In this, they could rely on the myth that

“the Parisian proletariat are ready and quick, prepared to descend into the

street at a moment’s notice from the Party.”

37

General Matthew Ridgway was targeted when he was named to replace

Eisenhower as the head of NATO. He was branded a war criminal by the

communist press and accused of ordering the use of bacteriological weapons

in the Korean War. When Antoine Pinay’s government banned a peace demon-

stration in Paris on May 28, 1952, the PCF decided to counter with a massive

protest. The narrative description of the worst day of protest and rioting from

L’Humanité exudes the sense of fluidity and sensuousness, the fierce struggle

for command of the streets that was the heritage of the Revolution:

The streets of Paris around 6 in the evening, under a drizzle that began to

fall at the end of the afternoon; a huge snarl-up at the crossroads empty

of traffic cops, who had been called to the rescue by a police already

on the defensive. The place de la République, black with helmets and

under the helmets, pale, very pale faces. At that moment, at the factory

gates, the mouths of the subways, at the bus stops, groups began to form,

and then suddenly signs appear, signs saying “Ridgway Get Out!,” “Go

Home!,” “Americans Go Back to America,” “We Want Peace!” Signs held

up on solid poles, long thick poles. The police aren’t reading the signs.

They just look at them. Nothing can stop this clamor that swells out to

engulf passersby, and other groups, waiting for this moment, [to] join

in the demonstration. People applaud at the windows. This is how it is

everywhere in Paris, to the north, south, east, and west. In a hundred

public space and confrontation | 125

different places, irresistible columns have taken charge. The police are

beaten. The street belongs to the people of Paris.

38

The tactic of the communists and their followers was to use the Métro to

spread out and attack police units from a variety of places rather than con-

fronting them head-on in battle. The Métro was a Parisian icon, an extension

of working-class maneuverability and swiftness. Demonstrators emerged at

the boulevard Magenta, the rue du Temple, the rue du Faubourg du Tem-

ple, the avenue de la République, the gare de l’Est, the gare Saint-Lazare,

the place des Victoires, and the place de l’Odéon.

39

The image invented by

the communists was of a people with quick reflexes, intelligent and fast,

against whom a plodding police force had little hope: “Baylot only knew

how to respond with the mad rage of his units, who took their revenge on

the loners, on prisoners. They unleashed themselves on the North Africans

with ignoble racist sadism.”

40

A contingent of two thousand descended from

Aubervilliers by Métro and fought police in the gare du Nord in a scene of

complete confusion. As the clashes tore apart the main hall, windows were

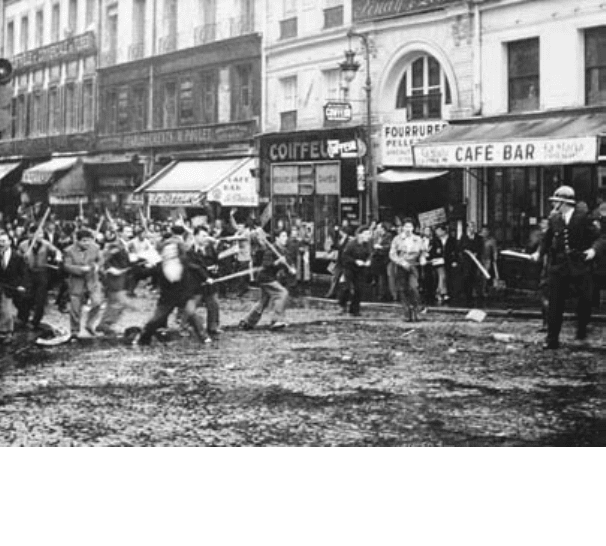

figure 10. Demonstrators and police on the streets of Paris during the Ridgway Riots, May

30, 1952. © bettmann/corbis.