Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

increases blood glucose levels. The blood glucose test

involves feeding a standard 50-g lactose dose and

measurement of plasma glucose every 30 min over a

period of 2 h. In the presence of lactose maldigestion,

blood glucose increases less than 25 mg dl

1

above

the fasting level. Unfortunately, this test is mildly

invasive and with a relatively low reliability.

0014 Because of its ease, low cost, and noninvasiveness,

the breath hydrogen test is most widely used to diag-

nose lactose maldigestion. Undigested lactose remains

in the intestine and is fermented by colonic bacteria,

producing hydrogen gas, carbon dioxide, and me-

thane in some individuals. Bacterial fermentation is

the only source of molecular hydrogen in the body. A

portion of the hydrogen produced in the colon dif-

fuses into the blood and is excreted via the lungs. The

breath test measures the excretion of this hydrogen.

Typically, a subject is given an oral dose of lactose

following an overnight (12 h) fast. Breath samples

are collected at regular intervals for a period of 5–8h

and analyzed by gas chromatography. The historical

test used 50 g of lactose as a challenge dose, and an

increase of 20 parts per million (p.p.m.) or greater

above the fasting level as an indicator of lactose mal-

digestion. More recently, it has been shown that using

a sum of hydrogen from hours 5, 6, and 7 and a 15

p.p.m. above-fasting criterion for maldigestion

resulted in 100% sensitivity and specificity for carbo-

hydrate maldigestion.

Pathophysiology of Lactose Maldigestion

0015 A positive breath hydrogen test measures undigested

carbohydrate in the colon and is indicative of lactose

maldigestion. However, the correlation between lac-

tose maldigestion and intolerance symptoms, such as

flatulence, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, is unclear.

The lactose may or may not result in perceptible

symptoms depending on a number of factors, includ-

ing the amount of lactose entering the colon, the

metabolic activity of the colonic flora, the absorptive

capacity of the colonic mucosa for the end products

of lactose fermentation, and the ‘irritability’ of the

colon.

0016 Colonic bacteria metabolize lactose, thereby redu-

cing osmotic pressure in the colon. If the colonic

bacteria did not ferment undigested lactose, the os-

motic activity of even relatively small doses of lactose

could result in diarrhea. However, diarrhea is virtu-

ally never encountered when LNP subjects ingest a

cup of milk (12 g of lactose). Colonic bacteria ferment

lactose to short-chain fatty acids that are readily

absorbed by the colon. However, when massive

quantities of carbohydrate are maldigested, colonic

absorption of fatty acids may not keep up with

production. In this situation the bacteria may actually

enhance the osmotic activity and hence aggravate the

ensuing diarrhea.

0017In the fermentation process of lactose, appreciable

quantities of gas (carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and

sometimes methane) are also produced. The removal

of these gases is accomplished by bacterial utilization,

excretion in flatus, or by absorption through

the colon. With small doses of lactose, gas may be

removed as rapidly as it is produced and there will

be no symptoms. However, with large lactose loads

these removal mechanisms may not keep up with

production, and bloating, distention, and flatulence

result.

0018A final important factor that plays a role in the

development of gastrointestinal symptoms is the re-

sponse of the colon to the presence of gas and organic

acids. Subjects with an ‘irritable’ colon might perceive

symptoms whereas subject with a ‘nonirritable’ colon

might tolerate the same degree of distention without

symptoms. The intensity of symptoms may also vary

with the amount of lactose consumed, the degree of

colonic adaptation, and the physical form of the lac-

tose-containing food.

The Relationship Between Lactose

Maldigestion and Lactose Intolerance

0019The larger the dose of lactose, the greater the risk that

the LNP subject will perceive symptoms of lactose

intolerance. Early unblinded studies in which subjects

were fed milk or lactose and then asked if they had

symptoms suggested that over 45% had symptoms

following a glass of milk or its lactose equivalent

(12 g). The results of such studies have provided the

basis for claims that many subjects require a diet

severely restricted in milk and milk products or the

use of a variety of commercially available lactose-

digestive aids. However, tolerance to milk can be

affected by factors unrelated to its lactose content

and may be due to psychological factors or cultural

attitudes toward milk. There is a psychogenic com-

ponent to abdominal symptomatology, particularly

relating to the minor and nonspecific type of symp-

toms (bloating, distension), that may result from

ingested food. The true symptomatic potential of

milk (or other foods) can only be obtained with

rigidly controlled double-blind studies. Under these

controlled conditions, researchers have found that

lactose intolerance is less prevalent than commonly

believed. For example, in a well-controlled trial, 50 g

of lactose (the quantity in a quart (approx. 1l) of

milk), taken as a single dose caused symptoms in

most of LNP subjects. On the other hand, several

blinded studies indicated that LNP subjects tolerated

2638 FOOD INTOLERANCE/Lactose Intolerance

up to one cup (237 ml) of milk without experiencing

significant symptoms. However, the results of these

studies did not gain general acceptance, in part be-

cause of failure to utilize subjects with ‘severe’ lactose

intolerance. Some LNP individuals believe that small

amounts of lactose, such as the amount used with

coffee or cereal, cause gastrointestinal distress.

0020 In 1995, our group conducted a study in 30 self-

described ‘severely lactose-intolerant individuals.’

Initial breath hydrogen test measurements indicated

that approximately 30% (9 of 30) of the subjects

claiming severe lactose intolerance were digesters,

and thus, had no physiological basis for intolerance

symptoms. Among the true lactose maldigesters

there were no significant differences in symptoms

of bloating, flatulence, or number of flatus passages

during the period when conventional milk (lactose-

containing) versus lactose-hydrolyzed milk was

ingested. During both treatment periods, symptoms

were extremely mild. The triviality of these

symptoms with conventional (or lactose-hydrolyzed)

milk was particularly impressive given the subjects’

prestudy perception that symptoms would be so bad

that they would be compelled to withdraw from

the study. These findings further demonstrate how

strongly behavioral and psychological factors influ-

ence symptom reporting. Additional research is ne-

cessary to evaluate the psychological component of

symptom reporting in lactose maldigesters.

Lactose Digestion and Calcium

0021 Lactose maldigestion could potentially increase risk

of osteoporosis either by decreased milk, and there-

fore calcium, intake or by decreased calcium absorp-

tion. Lactose maldigestion has been associated with

lower calcium intakes and consequently a higher

prevalence of osteoporosis. A sizable fraction of

lactose maldigesters may unnecessarily restrict

their intake of lactose-containing, calcium-rich dairy

foods. Milk and milk products contribute 73% of the

calcium to the US food. A second potential relation-

ship between lactose maldigestion and osteoporosis is

that maldigestion of lactose decreases absorption of

calcium. Human and animal studies suggest that

lactose stimulates the intestinal absorption of

calcium. However, there is considerable disagreement

regarding the influence of lactose and lactose maldi-

gestion on calcium absorption in adults. Differences

in study methodology (milk versus water, dose of

lactose, and the choice of method for determining

calcium absorption) may explain contrasting results.

Physiologic doses of lactose (up to two cups (474 ml)

of milk) do not appear to have a significant impact on

calcium absorption. Therefore, increased prevalence

of osteoporosis in lactose maldigesters is most likely

related to avoidance of dairy foods and subsequently

inadequate calcium intake rather than impaired intes-

tinal calcium absorption.

Dietary Management for Lactose

Maldigestion

0022There are several dietary strategies that effectively

reduce or eliminate intolerance symptoms without

compromising nutritional status (Table 5).

Dose–Response to Lactose

0023There is a strong positive correlation between the

dose of lactose consumed and the symptomatic re-

sponse. In general, increasing the amount of lactose

consumed increases the number and severity of symp-

toms. In lactose maldigesters, 2 g of lactose is almost

completely absorbed, whereas 6 g of lactose results in

a minimal degree of maldigestion as measured by

breath hydrogen. On average, maldigesters absorbed

about half of a 12.5-g lactose load, whereas the other

half passes to the terminal ileum. Interestingly,

unblinded studies have frequently reported intoler-

ance symptoms after consuming only 12 g lactose. In

1995 a double-blind protocol demonstrated that

feeding 12 g of lactose (approximately one cup of

milk) with a meal resulted in minimal to no symptoms

in maldigesters who believed themselves to be

extremely intolerant to lactose. Further evidence

indicated that lactose-intolerant individuals could

consume two cups (474 ml) of milk daily with

divided doses at breakfast and dinner, without experi-

encing appreciable symptoms. Overall, a dose con-

taining 18–25 g of lactose has the potential to

produce symptoms (mostly flatulence) in approxi-

mately half of a population. However, the frequency

of symptoms varies from less than 40% to greater

than 90% of a subgroup. Thus, a first important

dietary strategy is to limit milk consumption to one

eight-ounce glass (12.5 g lactose) per meal. Doing so

will dramatically reduce the likelihood of intolerance

symptoms.

Factors Affecting Gastrointestinal Transit of

Lactose

0024A key explanation of the large variability in dose–

response studies is whether or not the lactose is fed

with a meal. Consuming milk with other foods slows

the intestinal transit of lactose. Slowing the intestinal

transit permits longer contact between residual

lactase in the small intestine and lactose, thus improv-

ing digestion and reducing the potential for symp-

toms. It is also possible that additional food in the

intestine may slow the rate at which lactose is delivery

FOOD INTOLERANCE/Lactose Intolerance 2639

in the colon. A slower entry of lactose into the colon

might also improve the fermentation and reduce the

potential for symptoms.

0025 Individual foods also affect lactose digestion and

tolerance. Whole milk, due to its greater fat

and energy content, may slightly decrease breath

hydrogen relative to skim milk. Whether this effect

is large enough to improve tolerance is unclear. Like-

wise, the addition of chocolate to milk may improve

lactose digestion and symptoms, possibly due to its

higher osmolality or energy content and/or the effect

of cocoa on intestinal transit. Thus, a second key

dietary recommendation is to consume milk and

other lactose-containing dairy foods with meals.

This strategy will also insure that adequate calcium

intake can be achieved without symptoms of intoler-

ance.

Yogurts

0026 Lactose that is found in yogurt with live active cul-

tures (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and

Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus)is

digested better than lactose in milk. As a result,

yogurt is well tolerated by lactose-intolerant individ-

uals. During the manufacture of yogurts, milk solids

are typically added to fluid milk to enhance the prod-

uct. During yogurt production, the bacteria reduce

the lactose level from around 6% to approximately

4%. Lactic acid bacteria in yogurt exhibit a very high

activity of b-galactosidase. This activity functions

during the manufacturing process, and most import-

antly also during gastrointestinal digestion of lactose

in vivo in the stomach and/or small intestine. Clinical

studies have showed that consumption of up to 18 g

lactose as yogurt (two cups of yogurt) is well toler-

ated, and results in few symptoms of intolerance.

0027Pasteurization of yogurt increases the shelf-life but

decreases the number of active cultures that are partly

responsible for improved lactose digestion. However,

pasteurized yogurt is moderately well tolerated, pro-

ducing minimal symptoms. It is believed that the

physical form of the yogurt and the caloric density

are additional factors that improve tolerance to lac-

tose found in yogurt. Thus, a third dietary strategy is

to include yogurts as a part of a calcium-rich and

well-tolerated diet.

Lactase Supplements and Lactose-Reduced Milks

0028Pills, capsules, and drops that contain lactase deriv-

ed from yeast (Kluyveromyces lactis) or fungal

(Aspergillus niger, A. oryzae) sources have proved

effective for lactose digestion. Since 1984, these

over-the-counter preparations have been given the

status of generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by

the US Food and Drug Administration. Additionally,

milk that has been treated with lactase, resulting in a

70–100% reduction in lactose, is commercially avail-

able. Lactose-hydrolyzed milk typically has increased

tbl0005 Table 5 Dietary strategies for lactose intolerance

Factorsaffecting

lactosedigestion

Dietarystrategy References

Dose of lactose Consume a cup (237 ml) of milk or less at a time,

containing up to 12 g lactose

Suarez et al. 1995

Hertzler et al. 1996

Suarez and Savaiano 1997

Intestinal transit Consume milk with other foods, rather than

alone, to slow the intestinal transit of lactose

Solomons et al. 1985

Martini and Savaiano 1988

Dehkordi et al. 1995

Yogurts Consume yogurts containing active bacteria

cultures. A serving, or even more, should

be well tolerated. Lactose in yogurts

is better digested than the lactose in milks

Kolars et al. 1984

Gilliland and Kim 1984

Savaiano et al. 1984

Shermak et al. 1995

Pasteurized yogurts do not improve lactose

digestion. However, these products, when

consumed, produce little to no symptoms

Savaiano et al. 1984

Kolars et al. 1984

Gilliland and Kim 1984

Digestive aids Over-the-counter lactase supplement pills,

capsules, and drops may be used when

large doses of lactose (> 12 g) are

consumed at once

Moskovitz et al. 1987

Lin et al. 1993

Ramirez et al. 1994

Lactose-hydrolyzed milks are also well tolerated Nielsen et al. 1984

Biller et al. 1987

Rosado et al. 1988

Brand et al. 1991

Colon adaptation Consume lactose-containing foods daily

to increase the colon bacteria’s ability

to metabolize undigested lactose

Perman et al. 1981

Florent et al. 1985

Hertzler et al. 1996

2640 FOOD INTOLERANCE/Lactose Intolerance

sweetness, due to the presence of free glucose. Lactose

hydrolysis can be carried out by the consumer at

home, or products can be purchased already in low-

lactose form. A number of studies have evaluated the

effectiveness of these products. Doses of 3000–6000

FCC (Food Chemical Codex) units of lactase adminis-

tered just prior to milk consumption decrease both

breath hydrogen and symptom responses to lactose

loads ranging from 17 to 20 g. Thus, a fourth strategy

is to include lactose-reduced products and/or utilize

enzyme preparations if symptoms of intolerance are

present, despite adherence to simpler and more cost-

effective approaches.

Unfermented Acidophilus Milk

0029 Various strains of Lactobacillus acidophilus exist;

however strain NCFM (North Carolina Food Micro-

biology) has been most extensively studied and used

in commercial products. Unfermented acidophilus

milk tastes identical to unaltered milk since the

NCFM strain does not multiply in the product, pro-

vided that the storage temperature is below 40

F

(5

C). L. acidophilus strain NCFM is derived from

human fecal samples and contains b-galactosidase

(lactase). However unfermented acidophilus milk

does not enhance lactose digestion or reduce intoler-

ance symptoms in doses present in commercially

available products. It appears that the ingested bac-

teria are not disrupted by the bile acids, thus micro-

bial lactase is not released. However, when

acidophilus milk is sonicated, which destroys the

bacteria membrane, lactose digestion improves.

Colonic Fermentation and Bacterial Adaptation of

Lactose

0030 The colonic bacteria ferment undigested lactose and

produce short-chain fatty acids and gases. Historic-

ally, this fermentation process was viewed as a cause

of lactose-intolerance symptoms. However, it is now

recognized that the fermentation of lactose, as well as

other nonabsorbed carbohydrates plays an important

role in the health of the colon, and impacts the nutri-

tional status of the individual. The most compelling

evidence for colonic bacterial adaptation to lactose

comes from studies where the amount of lactose

is carefully controlled and gradually increased over

time. Increasing the daily lactose dose from 0.3 g kg

1

body weight up to 1.0 g kg

1

body weight over

a period of several days to 3 weeks results in a

several-fold increase in fecal b-galactosidase activity.

This elevated enzyme activity returns to baseline

levels with in a few days after the lactose-feeding

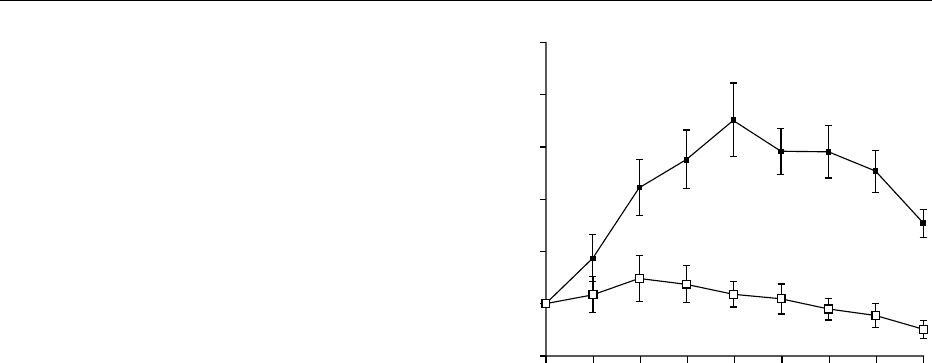

period. Furthermore, lactose feeding dramatically

decreases the breath hydrogen response to a lactose

challenge dose (Figure 1). In fact, after lactose

adaptation, the subjects may no longer appear to be

lactose maldigesters according to the breath hydrogen

test. The large doses of lactose fed during these adap-

tation periods (up to 70 g day

1

) result in only minor

symptoms. Additionally, the severity and frequency

of flatus symptoms in response to the lactose chal-

lenge dose are significantly reduced.

0031Thus it appears that colonic bacterial adaptation to

lactose does occur. Although the mechanisms that

cause colonic adaptation need further investigation,

it is clear that many lactose-intolerant individuals will

develop a tolerance to milk if they consume it regu-

larly. This may represent a simpler and less expensive

solution than the use of lactose digestive aids. Thus, a

final dietary recommendation to lactose-intolerant

individuals is not to avoid dairy foods, but rather to

include them in the diet on a daily basis. Daily con-

sumption of milk and dairy foods will enhance colon

bacterial adaptation and reduce the likelihood for

symptoms of intolerance.

Conclusion

0032Milk and milk products are important sources of

many nutrients, including calcium. The avoidance of

dairy products to prevent intolerance symptoms jeop-

ardizes bone density, thus increasing the risk for

osteoporosis. The inescapable conclusion to be

drawn from blinded studies is that virtually all

LNP subjects, including even those with severe

self-perceived intolerance, can drink milk or milk

−20

0

20

40

60

80

100

∆ Breath hydrogen (p.p.m.)

01234

Time (h)

567 8

fig0001Figure 1 Breath hydrogen response to a lactose challenge

after lactose (open squares) or dextrose (filled squares) feeding

periods. Data are the means + SEM, n ¼20. Reproduced from

Hertzler SR and Savaiano DA. Colonic adaptation to daily lactose

feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 64: 232–236, with permission.

FOOD INTOLERANCE/Lactose Intolerance 2641

products with minimal symptoms if taken in single

serving doses with meals. Thus, the role of the health

care provider is to convince the patient with self-

diagnosed or, less commonly, physician-diagnosed

lactose intolerance that various dietary strategies

effectively manage lactose intolerance by reducing

or eliminating gastrointestinal symptoms. However,

beliefs concerning lactose intolerance are not easily

reversed, and it may be very difficult to convince

patients that their abdominal symptoms are not

appreciably aggravated by ingestion of moderate

doses of lactose.

See also: Food Intolerance: Milk Allergy; Inborn Errors

of Metabolism: Overview; Lactic Acid Bacteria;

Lactose; Yogurt: The Product and its Manufacture;

Yogurt-based Products; Dietary Importance

Further Readings

Biller JA, King S, Rosenthal A and Grand RJ (1987) Effi-

cacy of lactase-treated milk for lactose-intolerant pedi-

atric patients. Journal of Pediatrics 111: 91–94.

Dehkordi N, Rao DR, Warren AP and Chawan CB (1995)

Lactose malabsorption as influenced by chocolate milk,

skim milk, sucrose, whole milk, and lactic cultures.

Journal of the American Dietary Association 95: 484–

486.

Florent C, Flourie B, Leblond A, Rautureau M, Bernier JJ

and Rambaud JC (1985) Influence of chronic lactulose

ingestion on the colonic metabolism of lactulose in man

(an in vivo study). Journal of Clinical Investment 75:

608–613.

Gilliland SE and Kim HS (1984) Effect of viable starter

culture bacteria in yogurt on lactose utilization in

humans. Journal of Dairy Science 67: 1–6.

Hertzler SR and Savaiano DA (1996) Colonic adaptation to

daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lac-

tose intolerance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

64: 232–236.

Kolars JC, Levitt MD, Aouji M and Savaiano DA (1984)

Yogurt – an autodigesting source of lactose. New Eng-

land Journal of Medicine 310: 1–3.

Lin M, Dipalma JA, Martini MC, Gross J, Harlander SK

and Savaiano DA (1993) Comparative effects of exogen-

ous lactase (B-galactosidase) preparations on in vivo

lactose digestion. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 38:

2022–2027.

Martini MC and Savaiano DA (1988) Reduced intolerance

symptoms from lactose consumed during a meal. Ameri-

can Journal of Clinical Nutrition 47: 57–60.

Moskovitz M, Curtis C and Gavaler J (1987) Does oral

enzyme replacement therapy reverse intestinal lactose

malabsorption? American Journal of Gastroenterology

82: 632–635.

Nielsen OH, Schiotz PO, Rasmussen SN and Krasilnikoff

PA (1984) Calcium absorption and acceptance of

low-lactose milk among children with primary lactase

deficiency. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and

Nutrition 3: 219–223.

Perman JA, Modler S and Olson AC (1981) Role of pH in

production of hydrogen from carbohydrates by colonic

bacterial flora. Studies in vivo and in vitro. Journal of

Clinical Investment 67: 643–650.

Ramirez FC, Lee K and Graham DY (1994) All lactase

preparations are not the same: results of a prospective,

randomized, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal

of Gastroenterology 89: 566–570.

Rosado JL, Morales M, Pasquetti A, Nobara R and

Hernandez L (1988) Nutritional evaluation of a lac-

tose-hydrolyzed milk-based enteral formula diet. I. A

comparative study of carbohydrate digestion and clin-

ical tolerance. Rev Invest Clin 40: 141–147.

Savaiano DA, AbouElAnouar A, Smith DE and Levitt MD

(1984) Lactose malabsorption from yogurt, pasteurized

yogurt, sweet acidophilus milk, and cultured milk in

lactase-deficient individuals. American Journal of Clin-

ical Nutrition 40: 1219–1223.

Shermak MA, Saavedra JM, Jackson TL, Huang SS, Bayless

TM and Perman JA (1995) Effect of yogurt on symp-

toms and kinetics of hydrogen production in lactose-

malabsorbing children. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition 62: 1003–1006.

Solomons NW, Guerrero AM and Torun B (1985) Dietary

manipulation of postprandial colonic lactose fermenta-

tion: I. Effect of solid foods in a meal. American Journal

of Clinical Nutrition 41: 199–208.

Suarez FL and Savaiano DA (1994) Lactose digestion and

tolerance in adult and elderly Asian-Americans. Ameri-

can Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59: 1021–1024.

Elimination Diets

C M Carter, Great Ormond Street Hospital for

Children, London, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Definitions and Aims

0001An elimination diet is one which excludes one or

more foods or food additives. The aim of an elimin-

ation diet is to diagnose and/or treat food-allergic

disease. Food-allergic disease is an intolerance to

food(s) resulting from an abnormal immunological

response. The title ‘food allergy and intolerance’ is

often used because an immunological basis cannot

always be demonstrated. This article discusses the

indications for the use of an elimination diet and the

dietary manipulations involved.

Indications and Contraindications

0002The symptoms of food allergy or intolerance may

come on quickly or slowly (Table 1). Symptoms may

2642 FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets

appear immediately after a very small amount of food

has been consumed and are usually associated with

immunoglobulins of the immunoglobulin E (IgE)

class. The gut, skin, and/or respiratory tract may be

involved and symptoms are listed in Table 1. Skin

symptoms include urticaria (also known as nettle

rash or hives, an itchy reaction characterized by the

appearance of raised red patches or wheals) and

angiedema (localized swelling of parts of the face,

mainly lips, eyes, and throat) The most serious reac-

tion is known as anaphylaxis, which is a state of

shock induced by antigen–antibody (mainly IgE) re-

action. It can be life-threatening unless epinephrine

(adrenaline) is administered rapidly. People who have

these very severe reactions to foods tend to be asth-

matic. First signs may be tingling of the lips, tongue,

and throat, sneezing, pallor, and feeling unwell and

light-headed. Skin rashes, angiedema, and urticaria

may or may not occur. First signs are quickly followed

by upper or lower airway obstruction, low blood

pressure, and cardiac arrhythmia.

0003 On the other hand, symptoms may come on

slowly after hours or days and only when a con-

siderable amount of the food has been consumed.

Gut, skin, and respiratory reactions are well docu-

mented and are likely to be T-cell-mediated without

IgE being involved (Table 1). However there is

some evidence for a ‘late-phase’ IgE response. Less

well-documented reactions to food include migraine,

epilepsy with migraine, attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD), and rheumatoid arthritis. There is

much difference of opinion as to the role of

diet, although the small amount of research carried

out indicates that the idea that food is

involved should be taken seriously, but etiology is

not known.

Immediate IgE-mediated Food Allergy

0004The presence of specific IgE antibodies can be dem-

onstrated quantatively with skinprick tests (SPT) or in

the serum with radioallergosorbent tests (RAST).

Although the negative predictive accuracy of SPTs is

95%, the positive predictive accuracy is only about

50%. This means that a negative result virtually pre-

cludes the possibility of an IgE-mediated allergic

reaction, while a positive result indicates an allergic

person, but an elimination diet cannot be based on

the results of these tests. RAST tests are no more

accurate.

0005However, people (or parents of children) who have

immediate reactions to foods usually have no doubt

as to the problem food and will need to avoid it.

Those who have severe or anaphylactic reactions to

food will need to avoid even the smallest trace and

this is difficult to do in practice. Any food may be a

trigger but the most common provoking foods are

peanut, tree nut, milk, egg, wheat, soya, fish, and

shellfish. Such elimination diets are hard to achieve

for the following reasons:

tbl0001 Table 1 Symptoms of food allergy and intolerance

Part of body involved Usually IgE-mediated Probably non-IgE-mediated

Immediate onset Delayed onset

Within 2 h Within a few hours to 3 days

After small amount of food After larger amount of food

Gut Swelling of lips, mouth Reflux vomiting

Oral allergy syndrome Abdominal pain, bloating

Vomiting Small-bowel enteropathy

Colic Failure to thrive

Allergic colitis, rectal bleeding

Diarrhea

Constipation

Skin Urticaria Eczema

Angiedema Urticaria (rarely)

Skin rashes

Lung Cough/wheeze/sneeze Asthma

Laryngeal edema

Bronchospasm

Systemic Cardiac arrhythmia

Hypotension

Anaphylaxis

Controversial Migraine

Migraine with epilepsy

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Rheumatoid arthrititis

IgE, immunoglobulin E.

FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets 2643

1.0006 Problems with manufactured food labeling. In

Europe and other parts of the world (except the

USA and Canada) there is a ‘25% rule’ which

means that if a product has a compound ingredient

which forms less than 25% of the finished prod-

uct, its ingredients do not have to be declared. For

example, the ingredients of salami on a pizza

would not have to be declared. Many food manu-

facturers are disregarding this rule for peanuts and

tree nuts and it is to be hoped that this will happen

for milk and wheat also. Another aspect of food

labeling involves the use of many terms for one

food item. Table 2 shows the many different terms

which denote the presence of milk.

2.

0007 Factory contamination. Many manufactured

foods are not produced on designated lines so

there is the possibility of food being contaminated

from a previous run or other factory contamin-

ation. For this reason most chocolate in the UK

and many other manufactured foods carry a ‘may

contain nuts’ label. This precludes a large array

of manufactured food for peanut- and tree nut-

allergic people.

3.

0008 Eating out. Although attempts are being made to

educate the catering industry, there are reports of

people eating in restaurants or purchasing take-

aways being told food was free of the requested

items when it was not. There is the possibility of

contamination when eating out (or at home)

when, for example, a sandwich for a nut-allergic

person may be made with an unwashed knife

which was previously used for a peanut-butter

sandwich. Alternatively a serving spoon could be

contaminated with food dished up previously.

Cross-contact may also occur through shared

grilling surfaces, food containers, and frying oil.

0009Children often grow out of allergies to milk, egg,

soya, and wheat but this is much less likely for aller-

gies to peanuts, tree nuts, and fish. Although SPTs

may give an indication, the only way to know if an

allergy has been outgrown is to perform a food chal-

lenge. For people who are at risk of severe reactions

challenges are performed in hospital where graded

doses of food are given over several hours and resusci-

tation equipment is available.

Delayed-onset Food Allergy or Intolerance

0010In the case of delayed reactions to foods, it is much

less likely that people know which foods are upsetting

them. Indeed, problems with foods which are eaten at

nearly every meal such as wheat and milk tend to

go completely unnoticed. SPTs and RAST tests are

not helpful. Claims of alternative diagnostic tests

have not been validated. Although the small-bowel

biopsy can be a useful tool in the diagnosis of gastro-

intestinal disease, it does not indicate which foods are

the problem.

0011The elimination diet is therefore the only available

‘diagnostic’ tool for suspected delayed-onset food al-

lergy or intolerance. The severity of symptoms should

be taken into account before deciding whether or not

to embark on an elimination diet. For example, it is

inappropriate to use such a diet for eczema unless the

child has failed to respond to the optimum skin treat-

ment and the eczema is severe enough to warrant diet

intervention. Diets can be socially disruptive and

nutritionally inadequate unless supervised properly

and may cause more problems than the disease it is

intended to treat. However, if symptoms are severe

and foods are suspected as being implicated (although

this is not a prerequisite), a ‘diagnostic’ elimination

diet is indicated. In the case of severe symptoms, it is

important that other more serious disease has been

ruled out before embarking on the diet approach.

Elimination Diet Strategy

0012Diagnosis of food allergy/intolerance by elimination

diet involves several phases. The first is an appro-

priate elimination diet which, if successful, results

in relief of some or all the symptoms. The second

phase involves sequential reintroduction of foods to

identify those foods that cause problems, and a third

phase is the final maintenance diet excluding all foods

that were demonstrated to have caused problems on

open introduction.

0013Phase 1: elimination diet This may be a diet exclud-

ing only one or two foods, a diet omitting a large

tbl0002 Table 2 Words denoting milk used in ingredient lists on

manufactured food labels

Nonfat milk solids

Skimmed milk powder

Casein

Whey

Cheese

Cream

Yogurt

Butter

Ghee

Butterfat

Buttermilk

Caseinates

Dry milk solids

Lactose

Hydrolyzed milk protein

Rennet casein

Sour cream

Whey protein concentrate

2644 FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets

number of foods, or even a diet consisting of a

hypoallergenic formula only.

0014 The empirical exclusion diet An empirical diet is

used where food allergy/intolerance is suspected,

causative agents are not known, and one or several

of the most commonly provoking foods are avoided.

Studies with children who have delayed reactions to

food indicate anecdotally that the most common pro-

voking foods are similar to those listed for immediate

reactions to foods, except that intolerance to some

food additives and chocolate appears more common

and intolerance to fish and nuts less common.

0015 In under 1-year-olds the most frequent offender is

cows’ milk-based infant formula, so a cows’ milk-free

diet is often used. Diet avoiding egg and milk together

with any known problem foods is sometimes used for

eczema. It is not unusual for pediatric gastroenterol-

gists to use a diet free of milk, egg, wheat, rye, and

possibly soya for children with gastrointestinal symp-

toms. Several adult centers use a diet free of all grains

(someinclude rice),egg, milk, chocolate, and additives.

This is sometimes known as a ‘hunter gatherer’ diet.

0016 The empirical diet may be followed for up to 6

weeks before a decision is made as to whether it has

helped or not. Unhelpful diets must be abandoned.

0017 Problems occur with empirical diets when excluded

foods are inadvertently replaced by others which are

equally capable of causing adverse reactions. For

example, a child on a milk-free diet may drink soya

milk or orange juice instead and it is possible to be

equally intolerant to these foods. Failure to respond

to an empirical diet does not rule out the possibility of

food intolerance. More restricted diets therefore have

a role to play.

0018Few-foods diet There are considerable difficulties in

teaching people how to avoid a large number of

foods. For very restricted diets it is easier to decide

on which foods the child can eat and teach the diet in

terms of which foods are allowed rather than concen-

trating on those that are forbidden. This is the basis

for the few-foods diet and 3–4 weeks is the longest

time one should consider using a very restricted diet,

although improvement may occur in a shorter time.

0019The few-foods diet may consist of no more than 5–

10 foods, all of which are least likely to cause prob-

lems. Different people working in this field have

achieved this in several ways. The simplest few-

foods diet consists of lamb, pears, and spring water

only. Although an adult may manage this, a child

would have great difficulty. Diets using one meat,

one carbohydrate source, one fruit, and one vegetable

have been used. If no improvement occurs, a second

diet containing a different set of foods can be used.

This is an ideal diet in theory but, because of compli-

ance problems, especially in children, it is not uncom-

mon to double up and allow two meats, two

carbohydrate sources, etc. (Table 3). The diet should

be individualized to some extent in that it cannot

tbl0003 Table 3 Few-foods diet and modifications

Few-foods diet Possible variationsand/oradditions

Meats Turkey, lamb Pork, chicken, rabbit

Starches Rice, potato Sweet potato, corn/maize

Vegetables Two from:1. Brassica

2. Carrot, parsnip

3. Cucumber, marrow, courgette

4. Onion, leek, asparagus

5. Swede, turnip

All vegetables except tomato

Include pulses

Fruit Two from:1. Peaches and apricots

2. Pears

3. Pineapple

4. Melon

5. Grapes

Allow all fruits listed on the left

Drinks Tap/bottled water Hypoallergenic formula for under 2s

Juice from allowed fruits

Miscellaneous Sunflower or olive oil Spices

Whey-free margarine

Small amount of sugar

Jam from allowed fruits

Salt, herbs

Vitamin/mineral supplements Not essential in short term

May be needed in the long term

Rice can be given as Thai rice noodles, puffed rice cakes, homemade rice cookies, rice ‘drink,’ boiled and fried rice, and risotto. Potatoes can be

prepared in many ways, including plain crisps/chips.

FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets 2645

include known problem foods, disliked foods, or

foods which are craved and usually eaten in large

amounts. Table 3 gives ideas for variations or slightly

enlarging the diet to make it more practical. Allergy/

intolerance can occur with any food and the few-

foods diet is really a ‘guesswork’ diet using those

foods least likely to be implicated.

0020 The few-foods diet can be difficult to follow and

should only be adopted if symptoms are frequent and

severe. The diet should be carefully taught and the

patient given ideas for menus and packed lunches and

provided with recipes for cooking with the foods

allowed. Close professional support is essential.

0021 Hypoallergenic formula only For such a diet, the

only food allowed is a nutritionally complete formula

which has no intact protein, the protein source being

supplied by either peptides derived from hydrolyzed

protein or synthetic amino acids. Such formulas are

available for infants and children and adults.

0022 This may be the first choice of diet for the infant

but it is very much a last resort for children and adults

and it probably means tube feeding (these products

do not have a good taste).

0023 Phase 2: reintroduction of foods If the elimination

diet has resulted in a worthwhile improvement, foods

are reintroduced sequentially in an effort to identify

provoking foods. If the effect of the diet is unclear or

if there is no improvement it should be abandoned or

another type of elimination diet tried. New foods

should be given in normal amounts for a week before

they are incorporated into the diet. During the period

of reintroduction, which may take months, the nutri-

tional adequacy of the diet must be monitored. Vita-

min and/or mineral supplements may be required. If

staple foods must be avoided, e.g., milk and wheat,

alternatives should be found.

0024 If there is a risk of a severe immediate reaction to a

food, it should either be avoided or reintroduced in

hospital as described. Some children with multiple

symptoms and multiple food intolerances have imme-

diate reactions to some foods and delayed reactions to

others.

0025 Some people’s symptoms are triggered by inhaled

substances, e.g., house dust mite, or by contact with

substances, e.g., grass as well as food. It can some-

times be difficult during the reintroduction phase to

know whether an adverse reaction is due to a food or

other allergens in the environment.

0026 Phase 3: maintenance diet Once all foods (and addi-

tives) have been introduced and those foods causing

problems avoided, the patient has arrived at a main-

tenance diet which will need to be adhered to.

0027Children have a tendency to grow out of their

problems so the possibility of reintroducing avoided

foods should be discussed every 6 months to a year.

This may happen in an unsupervised way as a result

of an accidental or a deliberate break in the diet.

0028If the maintenance diet excludes many foods it may

be necessary to compromise. During the introduction

phase some foods have an adverse effect after normal

amounts are consumed regularly over several days. It

may be possible to allow these foods from time to

time with no adverse effect.

Outcome Assessment

0029It is extremely helpful for patients (or parents) to keep

a daily symptom score diary beginning at least 1 week

before the diet starts and continuing during the open

reintroduction of foods. It can report on severity of

symptoms, dietary indiscretions, and other factors

that may be relevant. Diet manipulation is a very

crude form of diagnosis and a diary may make it

more objective.

Formulas for Infants with Cows’ Milk

Allergy

0030The infant who is not breast-fed and who is allergic to

the usual infant formulas which are based on cows’

milk protein will require an alternative.

0031Formulas based on whole soya protein isolate have

been available for many years. Infants with immedi-

ate IgE-mediated allergies often do well on these for-

mulas, although about 15% will be allergic to soya

also. Infants with gastoenteropathic symptoms are

much more likely to be intolerant of soya and these

formulas should not be used.

0032As previously mentioned, there are several infant

formulas available where the protein has been exten-

sively hydrolyzed to form small peptides. These for-

mulas are usually tolerated by cows’ milk-allergic

infants but a few highly allergic ones cannot manage

these either. A formula where the protein consists of

pure synthetic amino acids is most useful in these

circumstances.

Proof by Blind Food Challenge

0033Since diet treatment may have a powerful placebo

effect, the only way to prove that there is a physical

rather than purely psychological basis for the im-

provement on diet is to administer the foods ‘blind’,

i.e., when the subject is unaware that he or she is

consuming it. This is achieved by offering the chal-

lenge food hidden in other food known to be toler-

ated. On a second occasion, in random order with the

2646 FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets

first, material is given which looks and tastes like the

challenge but does not contain challenge material.

When the observer is also blind to the order of ad-

ministration the procedure is known as a double-

blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC).

This is regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for proof of

food allergy or intolerance.

0034 The DBPCFC has been used in many research stud-

ies. Over the last 25 years or so, American workers

have used the DBPCFC as an integral part of investi-

gations into immediate allergic reactions to food.

Researchers used incremental doses of food over 2–

5 h so that placebo and challenge could be completed

in one day. They have been recommended as a diag-

nostic tool outside the research area but are very little

used in the UK.

0035 The DBPCFC has also been used to investigate

more controversial slow-onset reactions to foods

such as ADHD. However, open reintroductions of

foods into an apparently successful elimination diet

tend to reveal that many people relapse after several

days of eating normal amounts of food. This makes a

DBPCFC much more difficult to design. One would

need to provide challenge and placebo material for a

week each with a 2-week washout period in between.

This has to be organized on an individual basis and

the following crititeria must be fulfilled:

1.

0036 Enough of the provoking food must be given for a

sufficient length of time. The amount will have

been established during open reintroduction.

2.

0037 The challenge food must be disguised in food

known to be tolerated in the amount to be given.

3.

0038 The two must be indistinguishable from one

another.

4.

0039 For children in particular, the material must be

acceptable in taste and quantity.

5.

0040 The challenge food should be provided in the same

form as that which caused symptoms on open

reintroduction. For example, dried powdered

milk may not have the same effect on a subject as

fresh pasteurized milk.

Although DBPCFCs may be an essential part of re-

search, they are rarely performed in clinical practice.

For the more controversial areas of food allergy or

intolerance they are time-consuming and difficult to

design. They are perhaps best reserved for those cases

in which there are serious doubts about the diagnosis.

Elimination Diets for Prevention of Food

Allergy

0041 There is much interest in the possibility of preventing

the onset of allergies in babies born into allergic fam-

ilies (sibling or parent with allergic disease). Results

of research studies are not clear-cut but some tenta-

tive guidelines may be drawn.

Diet During Pregnancy

0042Although research is ongoing in this field there is not

enough evidence to suggest that women who are

expecting ‘at-risk’ infants should alter their diets

during pregnancy.

Diet of the Mother During Lactation

0043There is little evidence to suggest that the diet of the

mother during lactation has any effect in the long

term on her child. However, there is some evidence

that in the short term this may be helpful. Indeed,

some highly allergic breast-fed children develop aller-

gic symptoms which can be controlled if their mother

avoids certain foods. For mothers who wish to do so,

a milk- and egg-free diet could be followed, provided

the mother has professional support and will need at

least a calcium supplement.

Careful Weaning of the Potentially Allergic Child

0044Breast-feeding should be encouraged for all children.

The ‘at-risk’ infant should have nothing but breast

milk for at least the first 4–6 months. If breast milk is

not available the best alternative is probably an infant

formula where the protein has been highly hydro-

lyzed. It is not known whether soya formula has a

protective effect. It would seem prudent to begin the

weaning process with pure baby rice, vegetables,

fruits, and meats, and wait until nearer 1 year old to

introduce milk, egg, and wheat. There are no specific

guidelines on this. Introduction of nuts should be

delayed until at least 3 years.

Conclusion

0045Elimination diets can be expensive, are socially dis-

ruptive, and run the risk of being nutritionally inad-

equate. They should be reserved for individuals with

troublesome symptoms who have not responded to

symptomatic treatment. The ideal place for this type

of treatment is in specialized clinics with interested

doctors and dietitians who have the necessary expert-

ise. Immediate reactions to foods can occasionally be

very severe or even life-threatening so very careful

advice must be given. Despite all these problems,

elimination diets can be of great benefit to many

people.

See also: Allergens; Food Additives: Safety; Food

Intolerance: Types; Food Allergies; Milk Allergy; Lactose

Intolerance; Infant Foods: Milk Formulas; Migraine and

Diet

FOOD INTOLERANCE/Elimination Diets 2647