Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

storage at unsuitable temperatures will allow the or-

ganisms to multiply and produce their toxins. Food

handlers who continue to work with active symptoms

of gastroenteritis are also a hazard because there is an

increased risk of fecal organisms reaching food.

Prevention of Food Poisoning

0019 An analysis of food-poisoning outbreaks which oc-

curred in England and Wales between 1970 and 1982

showed that the most common contributory factors

related to temperature control (Table 4) – either the

temperatures at which the food was held after

cooking or those achieved during preparation and

cooking. A later study published in 1996 drew similar

conclusions in relation to outbreaks occurring be-

tween 1992 and 1994 in the UK. In order to prevent

outbreaks of food poisoning it is important that

everyone involved in food preparation is made

aware that very few basic ingredients are sterile, but

will be contaminated to a greater or lesser extent

depending on their origin and amount of heat pro-

cessing and other manipulation. Poor hygiene during

processing and inadequate temperature control can

lead to proliferation of organisms to infectious dose

levels or the production of toxins in foods. Improve-

ment in agriculture procedures can lead to the reduc-

tion in the presence of some organisms, such as

Salmonella and Campylobacter, in our foods, but

good hygienic food preparation and education of

those involved in food production are the final lines

of defense.

0020Application of the hazard analysis critical control

points (HACCP) program is recommended for all

food production processes, from small catering

procedures to large-scale manufacturing. Once the

sources of contamination (the hazards) and the im-

portant points at which, and means by which, they can

be controlled (critical control points) are identified,

and controls introduced, monitored, and verified,

then the food manufacturer can have greater assur-

ance that he or she is producing a safe product. (See

Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point.)

See also: Contamination of Food; Fish: Spoilage of

Seafood; Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point; Heat

Treatment: Chemical and Microbiological Changes;

Histamine; Meat: Slaughter; Milk: Processing of Liquid

Milk; Parasites: Occurrence and Detection;

Pasteurization: Principles; Shellfish: Contamination and

Spoilage of Molluscs and Crustaceans

Further Reading

Djuretic T, Wall PG, Ryan MJ, Evans HS, Adak GR and

Cowden JM (1996) General outbreaks of infectious

intestinal disease in England and Wales 1992–1994.

Communicable Disease Report 6: R57–R63.

Doyle MP (ed.) (1989) Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens.

New York: Marcel Dekker.

Doyle MP, Beuchat LR and Montville TJ (eds) (1997) Food

Microbiology. Fundamentals and Frontiers. Washing-

ton, DC: ASM Press.

Gilbert RJ and Roberts D (1993) Foodborne bacterial gas-

troenteritis. In: Parker MT and Collier LH (eds) Topley

and Wilson’s Principles of Bacteriology, Virology and

Immunity, 9th edn, vol. 3, pp. 539–620. London:

Edward Arnold.

Hobbs BC and Roberts D (1993) Food Poisoning and Food

Hygiene, 6th edn. London: Edward Arnold.

International Commission on Microbiological Specifica-

tions for Foods (1980) Microbial Ecology of Foods:

1 Factors affecting Life and Death of Microorganisms;

2 Food Commodities. London: Academic Press.

International Commission on Microbiological Specifica-

tions for Foods (1998) Microorganisms in Foods: 6

Microbial Ecology of Food Commodities. London:

Blackie Academic and Professional.

Lancet Review (1991) Foodborne Illness. London: Edward

Arnold.

Morsel DAA, Corny JEL, Struijk CB and Baird RM (1995)

Essentials of the Microbiology of Foods. Chichester:

John Wiley and Sons.

Roberts D (1986) Factors contributing to outbreaks of

foodborne infection and intoxication in England and

Wales 1970–1982. Proceedings of the Second World

Congress of Foodborne Infections and Intoxications,

vol. 1, pp. 157–159. Berlin: Institute of Veterinary

Medicine.

tbl0004 Table 4 The most common factors contributing to outbreaks of

food poisoning in England and Wales in 1970–1982

Contributing factor Percentage of outbreaks

a

in which the factor

was recorded

Preparation too far in advance 57

Storage at ambient temperature 38

Inadequate cooling 32

Inadequate reheating 26

Contaminated processed food 17

Undercooking 15

Contaminated canned food 7

Inadequate thawing 6

Cross-contamination 6

Raw food consumed 6

Improper warm-holding 5

Infected food handlers 4

Use of left-overs 4

Extra-large quantities prepared 3

a

1479 outbreaks studied.

In some outbreaks several factors contributed.

From Roberts D (1986) Factors contributing to outbreaks of Foodborne

infection and intoxication in England and Wales 1970–1982. Proceedings of

the Second World Congress of Foodborne Infection and Intoxications,vol.1,

pp. 157–159. Berlin: Institute of Veterinary Medicine.

2658 FOOD POISONING/Classification

Tracing Origins and Testing

A C Baird-Parker, Northampton, Hardingstone, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Foodborne disease (food poisoning) has been defined

by the World Health Organization (WHO) as: ‘a

disease of infectious or toxic nature, caused by, or

thought to be caused by, the consumption of food

and water.’ It involves a large (> 40) and diverse

range of agents, the number of which continues to

increase yearly as new agents are identified. Table 1

lists those agents currently considered to be involved

in disease transmitted by foods.

0002 The main sources of many of these organisms are

domestic and wild animals (including fish and birds).

Enteroviruses, Salmonella typhi, and Vibrio cholerae

are of human origin and Clostridium botulinum,

Bacillus spp., and mycotoxigenic molds are general

environmental contaminants. (Refer to individual

microorganisms.)

0003 Food poisoning is usually thought of as acute

gastroenteritis (fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea,

often with vomiting) of the type caused by infectious

disease-causing bacteria such as S. enterica and toxin-

forming bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus.

However, a number of the newly identified (often

called ‘emerging’) food-poisoning microorganisms

cause a wide range of nonintestinal symptoms. For

example, Listeria monocytogenes causes illness

ranging from a mild flu-like illness to meningitis and

life-threatening infections of the central nervous

system. In addition, it has been recognized within

the last 20 years that a number of classical gastro-

enteritis-causing bacteria, such as salmonellas and

Yersinia enterocolitica, may cause extraintestinal in-

fections as sequelae to intestinal disease; these include

reactive arthritis, Reiter’s syndrome, ankylosing

spondylitis, and pericarditis. The wide range of symp-

toms caused by foodborne disease-causing agents,

many of which mimic illness of a nonfood-poisoning

nature, may cause some difficulty in identifying a

food cause and establishing the extent of a foodborne

disease incident.

0004This article considers the epidemiology of food-

borne diseases, the procedures used for testing foods

for the causative agents, tracing the source and

cause of a food-poisoning incident, and the recall of

contaminated food.

Epidemiology

0005When considering the sources of foodborne disease-

causing microorganisms it is important to recognize

that virtually all raw agricultural products will from

time to time be contaminated with low concentra-

tions of such organisms and, as a result of cross-

contamination and recontamination, they will also

contaminate cooked and other processed food prod-

ucts. Although salmonella are regarded to be zoono-

tic, and thus of animal origin, they are frequently

found in soils and water, and human carriers may

be the source. (See Epidemiology; Zoonoses.) Organ-

isms of human origin, such as the previously men-

tioned enteroviruses and Salmonella typhi, may also

contaminate various parts of the food chain, e.g., via

human carriers contaminating food during prepar-

ation for consumption, or from human sewage con-

tamination of foods during their growing, e.g., the

contamination of vegetables with night soil or mol-

luscan shellfish harvested from waters contaminated

with raw human sewage.

0006Thus the original source of an agent causing food-

borne disease may be difficult or impossible to estab-

lish with any degree of certainty and it may only be

possible, and in many cases only appropriate, to iden-

tify the circumstances and actual foodstuff that caused

a particular food-poisoning incident. In many cases

this will be the result of poor food handling (including

tbl0001 Table 1 Foodborne disease-causing agents

Bacteria

Aeromonas hydrophila and veronii subsp. sobria

Bacillus cereus, B. licheniformis, and B. subtilis

Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis

Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis

Clostridium botulinum and C. perfringens

Escherichiacoli(EIEC,ETEC,VTEC,EAggEC)

Listeria monocytogenes

Mycobacterium bovis

Salmonella enterica

Shigella dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei

Streptococcus zooepidemicus

Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, V. fluvialis, and V.

vulnificus

Staphylococcus aureus

Yersinia enterocolitica

Mycotoxigenic molds

Protozoa

Cryptosporidium

Cyclospora

Giardia

Tox o p l a sm a

Prions

vCJD

Viruses

Hepatitis A and E

Small round structured viruses (SRSV)

Dinoflagellates

Shellfish poisoning (PSP, DSP, NSP, ASP)

FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing 2659

preparation in advance for consumption) allowing

survival or growth of the pathogen. (See Food

Poisoning: Statistics.) For example, whereas the

main source of the contamination of foods with sal-

monellas and campylobacters is poultry, provided the

poultry is properly cooked, these bacteria will

be killed and if the cooked poultry is then protected

from recontamination they will not cause illness.

Thus, while the source of salmonella contamination

of cooked poultry is most likely to be the raw poultry,

the cause of any salmonellosis arising from its

consumption is most likely to be the result of poor

hygienic practice during preparation. In this example,

identification of the source of the original contamin-

ation is much less important than identifying the

circumstances that led to the contamination of the

cooked poultry. However, where contamination of a

raw ready-to-eat food occurs, it is important to

identify the source of the contamination to prevent

its recurrence. (See Poultry: Chicken; Ducks and

Geese; Turkey.)

0007 Further, when considering the cause of a foodborne

disease incident it is important to recognize that such

illness is dose-related (the larger the concentration of

the organism or the amount of toxin present in a food

at the time of consumption, generally the greater the

severity and extent of illness within a group of per-

sons consuming the contaminated food). It is seldom

that all persons exposed to an infective or intoxicat-

ing dose of a pathogen will show disease symptoms

and symptoms will often vary widely in those who are

ill. The minimum concentration of an agent necessary

to cause illness is frequently referred to as the min-

imum infective dose or MID. The MID of many food-

poisoning bacteria is unknown but it is generally

accepted that the infective dose of classical causative

agents of enteric disease, such as campylobacters,

Salmonella typhi, and Shigella,is10–100 cells,

whereas the MID of others such as the food-

poisoning salmonella (now all classified as Salmon-

ella enterica) is generally regarded to be of the order

of 100 000–1 million cells for a healthy adult. How-

ever, the infective dose and hence the risk of illness

arising from a contaminated food is affected by many

factors. Factors that may reduce the infective dose

include: high virulence of a particular strain; age,

status of health of individual exposed to the agent –

in particular immune status, nutritional deficiencies

in diet, and underlying disease. There is much evi-

dence that there are in some foods substances that

protect infective agents from destruction by stomach

acids. Thus fats in high-fat foods such as full-fat

cheeses, chocolates, and salamis may significantly

reduce the infective dose of an agent; for instance,

the infective dose of salmonellas may be only a few

cells (< 10) in these foods. Therefore, when consider-

ing the significance of a particular concentration of an

agent in a food, in relation to it having caused illness,

it is important to take these facts into consideration

and also to remember that in any food collected after

a food-poisoning incident, numbers of microorgan-

isms may have increased or decreased depending on

how that food has been stored subsequent to the

incident. With respect to microbial toxins these are

often more persistent in foods than their producing

organisms but may increase in amount as the result of

the presence of the producing organism, or decrease

as a result of biological, chemical, or physically

induced breakdown.

Case Histories

Hepatitis A and Frozen Raspberries

0008Twenty-one persons who consumed a mousse made

from frozen raspberries developed jaundice found to

be caused by the hepatitis A virus. Investigation of the

incident suggested that contamination had occurred

during harvesting or packaging of the raspberries.

Cases of hepatitis had been reported in the area

where the raspberries had been picked and the sani-

tary conditions in the places where the pickers were

housed were found to be poor. Sanitary conditions

were improved and basic food hygiene instruction

was given to the pickers. There were no more

reported incidents from this source.

Salmonella and Chocolate

0009The uncommon salmonella serotype Salmonella

napoli caused 245 cases of salmonellosis amongst

children. These were traced to the consumption of

contaminated chocolate bars from a single factory.

The factory was very modern and clean but untreated

river water was used for the water circulation system

which kept the chocolate molten during transporta-

tion around the factory; S. napoli had previously been

isolated from river water in the region of the factory.

Contamination of the chocolate probably occurred as

a result of microleaks in the pipes of the water circu-

lation system, resulting in the seepage of water into

the chocolate. Chocolate manufactures agreed to a

code of hygienic practice following this incident.

Salmonella and Salami Sticks

0010A number of cases of salmonellosis, mainly amongst

infants and children, occurred as a result of the con-

sumption of salami sticks. The salami sticks were

manufactured using traditional methods but with a

very short maturation period. The short maturation

period was not sufficiently long to destroy any

2660 FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing

salmonella present in the meat used in the manufac-

ture of the salami. Thus very small numbers survived.

This survival was prolonged by the practice in retail

outlets in the UK of storing the sticks in chill cabinets;

no cases were reported in continental Europe where

the sticks were stored at ambient temperatures. The

manufacturers reviewed their manufacturing proced-

ures, introducing a heating step in the process, thus

guaranteeing the destruction of any salmonella

that might survive the usual salami-manufacturing

process.

Staphylococcus aureus

and Pasta

0011 Epidemiological and microbiological tracing attrib-

uted 47 cases of staphylococcal food poisoning,

occurring in several European countries, to a single

source of lasagne. The source of the problem was

traced back to contamination of the eggs used in the

manufacture of the pasta and was believed to be

associated with the hygiene of equipment used to

transport the eggs. As a result of this incident a code

of practice was drawn up by the pasta industry re-

quiring the use of pasteurized eggs in pasta manufac-

ture and improved hygienic design of the equipment

used for the preparation of the pasta.

Clostridium botulinum

and Yogurt

0012 After 27 cases of botulism were traced to the con-

sumption of a locally produced yogurt containing

hazelnuts, the source was identified as canned hazel-

nut pure

´

e; this was part of a batch of low-calorie

products prepared using artificial sweetener. Unfortu-

nately the manufacturer of the hazelnut pure

´

e had not

recognized that the heat process used for commer-

cially sterilizing the normal high-sugar product was

not suitable for the low-calorie product. Sugars

reduce the available water (a

w

) to a level at which

spores of C. botulinum are unable to initiate vegeta-

tive growth and are thus unable to grow and form

botulinum toxin; the organism grew well in the sugar-

free product that had a much higher a

w

. The outcome

of this incident was to inform producers of these and

other products of the need to obtain expert advice on

the required heat process before reformulating a

canned food. Also, the national code of practice for

low-acid canned foods was revised to clarify all

requirements for the production of microbiologically

safe low-acid canned foods.

Testing Foods for Foodborne disease-

causing Microorganisms

0013 Foods may be tested for foodborne pathogens for

a variety of reasons; the main reasons are listed in

Table 2.

0014Microbiological testing of foods has been widely

applied by health authorities and industry as a means

of identifying foods that have levels of microorgan-

isms or their toxins in excess of those regarded to be

acceptable and therefore are unsafe or unacceptable

for human consumption for other reasons. Such

testing was at one time believed to give adequate

protection to the consumer and was the linchpin of

microbiological control strategies practiced by gov-

ernments and industry for much of the twentieth

century. This was despite the recognition more than

30 years ago that such testing gave little or no assur-

ance of microbiological safety or quality. This can be

illustrated by reference to the most stringent testing

plan applied internationally for examining baby food

for salmonella. In this plan, a sample comprising 60

individual sample units is taken from a batch of baby

food and from each sample unit an analytical sample

unit of 25 g is taken and examined for salmonella

(total analytical sample is thus 1500 g); the pass

criterion is no detection of salmonella in any of the

analytical units examined. Even when this pass criter-

ion is met, there is 50% probability that up to 1% of

the sample units in the food batch will be contamin-

ated. Clearly this degree of confidence is not accept-

able, particularly when considering that such a

sampling plan may be applied to test the acceptability

of a baby food.

0015It is such considerations that have led to a total

reappraisal in recent years of the value of such testing

as a means of assuring the microbiological safety of a

foodstuff. This has led to the wide-scale introduction

of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP)-

based control systems whereby the potential hazards

associated with manufacture of a food in a particular

processing plant are identified using a structured

hazard analysis procedure and locations where these

hazards can be effectively controlled are identified.

These locations are called Critical Control Points and

means for their proper control (including means of

monitoring that control is maintained) are identified.

(See Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point.)

tbl0002Table 2 Uses of microbiological testing

Investigational testing Suspect contaminated food

Compliance testing Governmental regulations; industry

standards and purchasing

specifications

Monitoring Authorities monitoring imported and

domestic foods; industry monitoring

products and processes

Verification Good manufacturing practice and

Hazard Analysis Critical Control

Point

FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing 2661

0016 As a result of the introduction of HACCP as a

prime means of assuring the microbiological quality

and safety of foods, microbiological testing has

become less important as a primary control function

and increasingly is used mainly by industry for the

purpose of verification of HACCP. However, where

HACCP is not applied, the industry or a health au-

thority may apply microbiological testing if there is a

need to obtain a judgment about the acceptability of a

foodstuff. For instance, it may be appropriate for use

in a buying specification for a microbiologically sen-

sitive raw material from a new supplier or by a health

authority on a consignment of imported food, where

microbiological testing is the most appropriate ac-

ceptance criterion. For such a purpose, it is important

that statistically based sampling plans are used so that

the degree of confidence in the result obtained is

known; methods of analysis should also be agreed.

One of two types of sampling plans may be used for

such acceptance sampling. The first and most widely

used are the two- and three-class attribute plans es-

tablished by the International Commission on Micro-

biological Specifications for Foods. Such plans were

developed principally for testing foods in inter-

national trade for their acceptability, but are also

widely used by industry in buying specifications.

0017 Two-class plans have a single limit which distin-

guishes between an acceptable and unacceptable con-

centration of a microorganism or toxin and is used in

sampling plans for foodborne pathogens.

0018 Three-class plans are used principally for determin-

ing acceptability of levels of general microbial con-

taminants and indicator organisms and have two

limits: one is a lower limit generally established by

good manufacturing practice (GMP) requirements,

while the other is an upper limit based on some

index of unacceptable quality. The other main type

of plan used is the standard variables plan which is

based on knowledge of microbial distributions in

batches of foods and can be used when such distribu-

tions approximate to log normality. This limits their

use principally to industry, where their advantage

over attribute plans is greater accuracy and hence

greater confidence in decisions based on their use.

0019 The choice of a sampling plan and testing pro-

cedures for investigative sampling which may, for

example, be used to identify the level of contamin-

ation in a suspect consignment of food, or to investi-

gate food involved in a food-poisoning incident, is

more difficult than acceptance sampling. One major

problem is that there will usually be no information

on either the likely incidence of contaminated prod-

uct units (or the level of contamination); these factors

set requirements for the number of units of product

that should be examined and the size of the analytical

unit that should be tested. In investigative sampling,

unlike acceptance sampling, random sampling may

not be the most appropriate procedure. For example,

the location of the product units in relation to

possible source of the contamination may suggest

that cluster or stratified sampling may be more

appropriate.

Tracing the Origins of a Foodborne

Disease Incident

0020Investigation of the cause of an outbreak or case of

foodborne illness will usually require a number of

procedures depending on the type and circumstances

associated with the incident. These may include ex-

tensive testing of food and clinical samples for likely

causative agents; the use of epidemiological analytical

techniques to link illness to a common source if a

number of cases of illness are involved; field investi-

gations by public health and industry experts to find

the cause; and specialist food-processing knowledge

to identify what measures need to be taken to prevent

its recurrence.

0021The tracing of the source and cause of an outbreak

of foodborne disease associated with a well-defined

event, such as a banquet, is usually a relatively easy

matter. A list of foods consumed by the ill persons is

compared against a list of items consumed by persons

who are not ill, and using simple statistical correl-

ation procedures, any significant differences in foods

consumed by the two groups are identified and fur-

ther investigated to find the most likely food source.

Tracing the source of sporadic cases in a community

is much more difficult and, as well as extensive use of

well-founded epidemiological procedures, investiga-

tors need a certain amount of serendipity, backed

up by specialist laboratory resources, in order to be

successful.

Laboratory Investigations

0022Samples of suspect foods, together with clinical

samples, should be collected and transported under

conditions that protect them from external contamin-

ation and minimize changes in the concentration of

any food-poisoning agent that may be present, e.g., in

sealed sterile containers in a suitably cooled cool box.

Details of the history of the sample, e.g., where and

when sampled and by whom and how, together with

information on symptoms of illness should be submit-

ted to the laboratory as this will help in selecting the

most appropriate method of analysis. On receipt by

the laboratory the samples should be documented,

properly stored, and examined as soon as possible.

Such examinations must be undertaken by laboratory

staff who have been trained in the microbiological

2662 FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing

examination of foods as well as clinical specimens;

they should be particularly knowledgeable of the

analytical procedures to be applied. These should be

performed in accredited laboratories operating to

recognized good laboratory practice (GLP) standards

and using procedures and methods that have been

approved by an appropriate accreditation organiza-

tion. The microbiological examination of a foodstuff

can be problematic and a number of pitfalls may trap

the unwary or careless. For instance, examination

of food specimens in the same room where clinical

specimens are examined is bad practice; a heavy

microbial load in a clinical specimen can easily

cross-contaminate a food sample, where only light

contamination with the same organism in the clinical

specimen is sufficient evidence to implicate a food as

the source.

0023 Initial laboratory findings should always be inter-

preted with care. Isolates and where appropriate ori-

ginal specimens should be submitted to a reference

laboratory with expertise in the suspect agent of

concern in order to confirm an initial finding and,

if appropriate, to apply modern ‘fingerprinting’ and

typing methods such as DNA-based subtyping

methods. There are many examples of foods being

erroneously implicated in a food-poisoning incident

because of poor laboratory practice. There have also

been many examples where failure to identify a

causative agent, or a food source, has been the result

of failure of the laboratory to apply the correct

isolation or detection method. The microbiological

examination of foods is not an exact science, al-

though continued improvements in detection tech-

niques in recent years have considerably improved

our ability to detect pathogenic agents in foodstuffs.

Epidemiological Investigations

0024 Two main analytical tools are used by epidemiolo-

gists to trace the source of a foodborne disease inci-

dent: case-control studies and cohort studies. For

both, the first stage is to review and document all

available information. In an investigation of an out-

break, a questionnaire is prepared to detail when and

what was consumed and symptoms of illness. This

questionnaire is used in preliminary interviews with

persons affected by the outbreak to obtain basic infor-

mation as to the likely cause. A case definition is also

agreed, i.e., what symptoms should be searched for, as

it is important when case searching (in order to

identify the extent of an incident) that only the most

likely cases are identified.

0025 In a case-control study a series of questions based

on the preliminary questionnaire are asked of the

persons identified as corresponding to the case

definition (case group) and persons who have not

been ill (control group). These two groups are

matched as far as possible with respect to age, sex,

socioeconomic group, and place of work or residence.

Controls are often based on consultation with the

general practioners of the persons who have been ill.

Based on information in the completed question-

naires, differences between items consumed by the

ill and well group are identified and any statistically

significant differences subjected to further investiga-

tion. One problem with this procedure is that it is

common in food-poisoning incidents to have symp-

tomless cases and these may well be mistakenly iden-

tified as part of the control group.

0026In the analysis of the case data the following are the

most important.

1.

0027Time to onset of illness. Based on knowledge of

the incubation period of the illness it is possible to

determine the period of exposure to infection. This

information may then be plotted as a histogram

relating the frequency of cases chronologically to

date of onset of illness. This so-called ‘epidemio-

logical’ or ‘epidemic’ curve can then be used to

identify whether or not there has been secondary

transmission of illness and whether or not it is a

point-source outbreak, e.g., a single meal, or a

common-source outbreak, e.g., a number of cases

from the same source, such as a retail establish-

ment, occurring over a particular time period.

2.

0028The place where infection occurs. A map is drawn

of known cases, and researchers look for relation-

ships, such as clusters, which may assist in identi-

fying a source.

3.

0029The persons involved. Analysis of information on

individual cases such as age, sex, medical history,

occupation, home situation and any travel history

may also help one to form hypotheses as to the

source of infection.

0028In a cohort study, a group of people is identified by

some other means than illness. For example, this

might be all the persons who attended a conference

at which it is suspected that a meal was consumed

that led to illness. The persons are divided into two

groups according to whether or not they ate a par-

ticular meal; the attack rate in the group eating the

meal and that of the group not eating it is calculated.

If there is found to be a statistically significant correl-

ation for the consumption of a particular meal, the

next stage is to determine the attack rates for persons

eating and not eating a particular menu item. By this

means, if successful, a particular menu item will be

identified as the source of the agent that caused the

illness.

FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing 2663

Environmental Health Investigations

0029 As part of an investigation into a foodborne disease

incident, health inspectors may visit and investigate

the identified source, e.g., the place where a foodstuff

implicated in a food-poisoning incident was manufac-

tured or prepared for consumption. This may involve

a detailed examination of the hygienic practices, and

the collection of product and environmental samples

for laboratory examination. If an infectious disease is

suspected, food handlers may be asked to submit

samples for microbiological examination. Where a

source of contamination has been identified, the

health authority is most likely to require assurance

that the condition that caused the contamination has

been corrected prior to allowing the product to be

returned to the market place. Such assurance may

require evidence that checks have been done by a

third party to confirm that satisfactory control

measures are in place. If a HACCP plan is in place

this plan will need to be revalidated.

Withdrawal of a Suspect Food

0030 If a distributed food is found by a health authority or

a producer to be contaminated with a concentration

of a pathogen or toxin exceeding a legal limit or

exceeding a level generally regarded to be hazardous

to health, this food should be withdrawn from sale as

soon as possible and if necessary the public informed.

0031 Before announcing the public withdrawal of a food

it should be ascertained, as far as is technically pos-

sible, that this food is unsafe to eat. Wherever pos-

sible, results of microbiological analyses or evidence

clearly linking cases of illness to an implicated food

item should be available to the health authority and/

or producer, as adverse publicity is likely to result

from a public recall which may cause much damage

to the reputation of the producer. The prudent produ-

cer may not wish to run the risk of even worse publi-

city arising from an incident occurring as a result

of failure to inform the public and may voluntarily

withdraw the product and inform the public of this.

0032 Authorities will take different actions concerning

the extent of a recall depending on a judgment as to

the health risk involved by allowing food to remain

on sale or in the hands of a consumer. Thus a recall

may only be required down to the distribution level,

e.g., distribution warehouse, if it is judged that any

food remaining on sale is unlikely to cause further

illness. A similar decision may well be made for a

food containing a level of microorganisms exceeding

a legal limit but where no illness has been reported.

However, if it is judged that serious illness could

result from product on sale or in the hands of

consumers, recall down to retail level would be the

minimum requirement and a public warning (via the

media) would usually also be required. It is important

that a recall is properly coordinated by the owner or

supplier of the food; for this to be effective a food

company should have a documented recall procedure

in place. As part of this procedure a recall coordinator

should be appointed whose role is to coordinate the

recall, to liaise with the public and the authorities on

progress with the recall, and to act as the spokes-

person in contact with the media.

0033When carrying out a public recall it is important

that this is done as fast and thoroughly as possible.

Thus there will be the need for press statements via

the media and communication to customers (and re-

tailers) via e-mail or fax, advising them of the recall.

In the case of a national or international recall the

health authorities will inform their contacts via estab-

lished networks and if a particular ingredient is

involved may work with the supplier to identify and

advise producers who may be using this ingredient in

further products. Effective coding of food batches and

maintenance of records of distribution are essential

requirements as production failures will inevitably

occur from time to time.

See also: Bacillus: Food Poisoning; Clostridium:

Occurrence of Clostridium botulinum; Botulism;

Epidemiology; Food Poisoning: Statistics; Hazard

Analysis Critical Control Point; Listeria: Listeriosis;

Poultry: Chicken; Ducks and Geese; Turkey; Salmonella:

Properties and Occurrence; Vibrios: Vibrio cholerae;

Yersinia enterocolitica: Properties and Occurrence;

Zoonoses

Further Reading

Baird-Parker AC and Tompkin RB (2000) Risk and micro-

biological criteria. In: Lund BM, Baird-Parker AC and

Gould GW (eds) The Microbiological Safety and

Quality of Food, vol 11. pp. 1852–1885. Gaithersburg,

Maryland: Aspen.

CAST (1994) Foodborne Pathogens: Risks and Conse-

quences. Task Force report no. 122. Ames, Iowa: Coun-

cil for Agricultural Science and Technology.

FAO/WHO (1998) Codex Alimentarius, Vol. 1B. General

Requirements (Food Hygiene) Supplement. Rome: Food

& Agriculture Organization.

International Commission on Microbiological Specifica-

tions for Food (1986) Microorganisms in Foods 2.

Sampling for Microbiological Analysis: Principles and

Specific Applications, 2nd edn. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press.

International Commission on Microbiological Specifica-

tions for Food (2002) Microorganisms in Foods 7.

Microbiological Testing in Food Safety Management.

New York: Kluwer Academic / Plenum.

2664 FOOD POISONING/Tracing Origins and Testing

Jarvis B (2000) Sampling for microbiological analysis. In:

Lund BM, Baird-Parker AC and Gould GW (eds) The

Microbiological Safety and Quality of Food, pp.

1691–1733. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen.

Palmer SR (1990) Epidemiological methods in the investi-

gation of food poisoning outbreaks. Letters in Applied

Microbiology 11: 109–115.

Sharpe JCM and Reilly WJ (2000) Surveillance of food-

borne disease. In: Lund BN, Baird-Parker AC and

Gould GW (eds) The Microbiological Safety and Qual-

ity of Food, vol. 11, pp. 975–1011. Gaithersburg, Mary-

land: Aspen.

WHO (2001) WHO Surveillance Programme for Control

of Foodborne Infections and Intoxications. 7th Report

1990–1992. Berlin: Federal Institute for Health Protec-

tion of Consumers and Veterinary Medicine.

WHO (1997) Food safety and foodborne diseases. World

Health Quarterly 50: 3–154.

Statistics

S Palmer, University of Wales, College of Medicine,

Cardiff, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 The public health significance of food-poisoning stat-

istics can be properly understood only when set in the

context of public-health surveillance.

0002 Modern public-health surveillance of disease has

been defined as the continued watchfulness over the

distribution and trends of incidence through the sys-

tematic collection, consolidation, and evaluation of

morbidity and mortality reports and other relevant

data, and applying these data to prevention and

control.

0003 Surveillance needs to be distinguished from re-

search. The former focuses on problem detection

and characteristics, whereas research is mainly to do

with hypothesis testing. Surveillance systems generate

hypotheses and should not be expected to give

detailed answers. Surveillance data provide informa-

tion for action and as such should stimulate investi-

gation. Emphasis has to be on speed of detection of a

potential problem rather than full and accurate docu-

mentation. Consequently, great care has to be exer-

cised in interpreting surveillance statistics for food

poisoning. Surveillance systems by definition require

ongoing collection of data and therefore to be sus-

tained over time have to rely on minimal data which

are often incomplete. National surveillance systems

have often gone into decline because data collection

has been driven by a desire for full documentation

rather than the overriding requirements of timeliness

and sensitivity to trends.

0004Specific objectives of foodborne disease surveil-

lance include:

1.

0005early detection of clusters or outbreaks of food-

borne disease or new exposures and other risk

factors, to trigger rapid investigation and control;

2.

0006measuring trends in microbial agents and risk

factors in order to set priorities for interventions,

and to evaluate foodborne disease control pro-

grams; and

3.

0007to describe the basic epidemiology of foodborne

disease, such as its geographical spread and the age

distribution of cases in order to develop hypoth-

eses about causation, which can be tested by sep-

arate research studies.

Methods of Surveillance

0008The main steps in surveillance are

.

0009systematic collection of data;

.

0010analyses of these data to produce statistics;

.

0011interpetation of the statistics to produce informa-

tion;

.

0012distribution of this information to all those who

require it so that action can be taken; and

.

0013continuing surveillance to evaluate the action.

Data Collection

0014Surveillance is, by definition, an ongoing activity and

can be sustained only when the burden placed on the

data providers is light. Surveillance data should be

limited to the minimum required to meet its specified

objectives. Reporting methods should be simple

and streamlined. Successful systems have been de-

veloped using modern information technology. Elec-

tronic data collection should be linked to electronic

systems for dissemination of high-quality surveillance

information.

Statistical Analysis

0015Usually, the routine analysis of surveillance data is

simply the presentation of incidence rates by time,

place, and person using graphs, histograms, and

maps. However, more sophisticated methods are in-

creasingly being used. Particular statistical issues

include the use of time series analysis to model epi-

demics, the early recognition of unusual events in

routine data against a variable baseline rate, small

area analysis of clustering, adjustment for delays

and incompleteness of reporting, and the use of

FOOD POISONING/Statistics 2665

surveillance data in risk assessment models and in

prediction models to evaluate the consequences of

possible interventions.

Reporting

0016 Timely reporting to those responsible for public-

health action is an essential part of a bona fide

surveillance system. Timeliness is defined by the ob-

jectives of the surveillance. For foodborne disease,

timely reporting may need to be measured in hours

so that contaminated food can be removed from the

marketplace and warnings given to consumers, a

target which can now be achieved globally through

the internet. Typically, foodborne disease surveillance

reports appear either as specifically produced publi-

cations (e.g., the Communicable Disease Report), or

as electronic bulletins.

Sources of Data

0017 Foodborne disease surveillance relies on two main

sources of statistics; the statutory notifications of

food poisoning and the voluntary reporting of labora-

tory isolations.

Statutory Notifications

0018 In England and Wales, mandatory notification of

infectious disease was introduced nationally in

1899. All registered medical practitioners diagnosing

certain diseases have a duty by statute to report to the

proper officer of the local authority so that suspected

cases can be investigated and control measures taken

as appropriate. Currently, food poisoning is notifiable

under the Public Health (Control) Act 1984. In Eng-

land and Wales, weekly summaries of these data are

now published in the Public Health Laboratory Ser-

vice (PHLS) Communicable Disease Report (CDR).

The data are later corrected and published quarterly

and annually by the Office for National Statistics. In

addition to those cases formally notified by medical

practitioners, local authorities identify other sus-

pected cases informally. The notification system

now has the flexibility to record these ‘otherwise

ascertained’ cases which appear separately in reports.

0019 It is important to note that ‘food poisoning’ is a

notifiable disease, although the bacterial causes of

food poisoning are not in themselves notifiable. This

has led to some confusion. The Advisory Committee

on the Microbiology Safety of Food proposed a

working definition of food poisoning which was

accepted by government departments and circulated

to all doctors in the UK in 1992. Its definition of food

poisoning is ‘any disease of an infectious or toxic

nature thought to be caused by the consumption of

food or water.’ This definition had previously been

adopted by the World Health Organization.

0020Nevertheless, the way in which this definition is

applied is subject to various interpretations.

For example, verocytotoxic E. coli (VTEC) disease

is quite likely to be foodborne, even though person-

to-person spread and spread from direct contact with

animals and the contaminated environment are sig-

nificant problems. If the source of infection is un-

known, a doctor may or may not suspect foodborne

disease. If the source is suspected to be direct

contact, technically the disease is not food poisoning,

even though reporting to statutory agencies might

alert them to a foodborne disease risk. It seems pru-

dent, therefore, that suspected and confirmed VTEC

infection, together with all Salmonella and Campylo-

bacter species, however acquired, should be notified

as a suspected foodborne disease.

0021The purpose of notification is to alert local author-

ities to take appropriate action to investigate and

control incidents; data for surveillance are a second-

ary benefit. However, it is generally accepted that

food-poisoning notifications are a poor indication of

the true incidence of food poisoning, even though

they may provide useful information on trends. This

is because people with the symptoms of food

poisoning often do not visit their general practitioners

(GPs). When a GP does see a patient with foodborne

disease, it is usually not possible to distinguish this

from other more common causes of gastroenteritis. In

individual cases, the food history is seldom helpful.

Only when a feces sample yields a foodborne patho-

gen is a measure of confidence obtained. However,

from a clinical point of view, there is usually little, if

any, benefit to the patient from the results of a

feces sample, and therefore, GPs do not routinely

send samples to the laboratory. When they do,

it tends to be because of the severity or persistence

of symptoms.

0022Figure 1 shows that in England and Wales, notifi-

cations, ascertained both formally and otherwise, in-

creased greatly from 1982 to 2000. Interpretation of

these data is difficult since over this same period,

considerable efforts have been made in the National

Health Service and local authorities to improve

reporting. Inevitably, this means increasing the

numbers of cases notified. It is therefore unclear

how much of the increase is due to better reporting

and how much is due to a real increase in the inci-

dence of food poisoning in the community.

Laboratory Reporting of Microbiological Data

0023Reports by diagnostic laboratories provide the back-

bone of infectious disease surveillance in the UK. In

England and Wales, the PHLS developed reporting

2666 FOOD POISONING/Statistics

in the 1940s and 1950s. Data are analyzed within a

week of receipt by the Communicable Disease Sur-

veillance Centre (CDSC) to produce tables and line

lists, which are used in compiling narrative reports for

publication to the CDR. The recent introduction of

OSURV (business name of electronic reporting

system) has substantially replaced manual and elec-

tronic reporting.

0024 The PHLS receives reports from over 200 clinical

and public health laboratories and also uses the data

held by the PHLS Laboratory of Enteric Pathogens,

which is the national reference laboratory for Sal-

monella, Campylobacter, and VTEC infections. In

Scotland, the SCIEH (Scottish Centre for Infection

and Environmental Health) receives laboratory

reports. Although these data are highly specific be-

cause they are based on the most comprehensive

diagnostic tests, the number of reports received rep-

resents only a small fraction of the true incidence of

these pathogens because of both the low level of

microbiological investigation in general practice and

incomplete laboratory reporting. Information accom-

panying these reports is limited, and there are no data

on the outcome of infected patients. The data do not

include patient identifiable details, so the area of

residence cannot be mapped.

0025 The main benefits of laboratory reports are that

they are highly specific, since they are based on la-

boratory-diagnosed infections and the fine typing of

the infecting organism, they often include clinical and

epidemiological details, and they allow free-text com-

ment. The reporting system is flexible, and unusual or

new infections can be reported, even though they

have not been included in the original reporting in-

structions. However, the reports are limited to infec-

tions for which there is a suitable laboratory test.

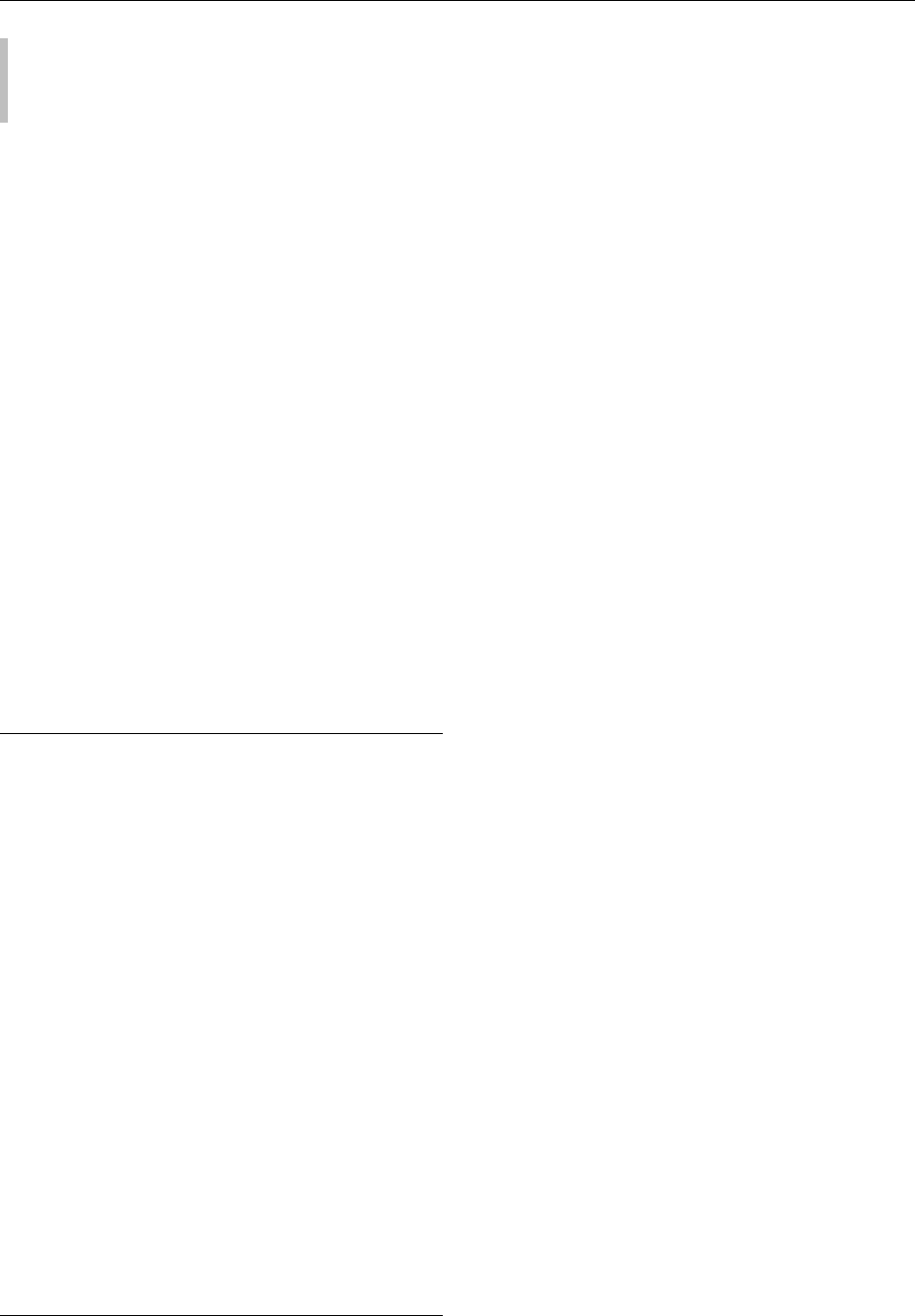

0026 Figure 2 shows that reports of Salmonella infection

in England and Wales tripled from 1981 to 1990.

From 1990 to 1997, the high level of reports was

maintained. From 1998 to 2000, Salmonella reports

fell steadily, but in 2001, provisional data suggest an

increase. These data correspond to the epidemic of

Salmonella enteritidis that affected egg production

internationally. The effect of the control measures,

especially the vaccination of laying flocks, is thought

to explain the sudden reversal of the epidemic in

1998.

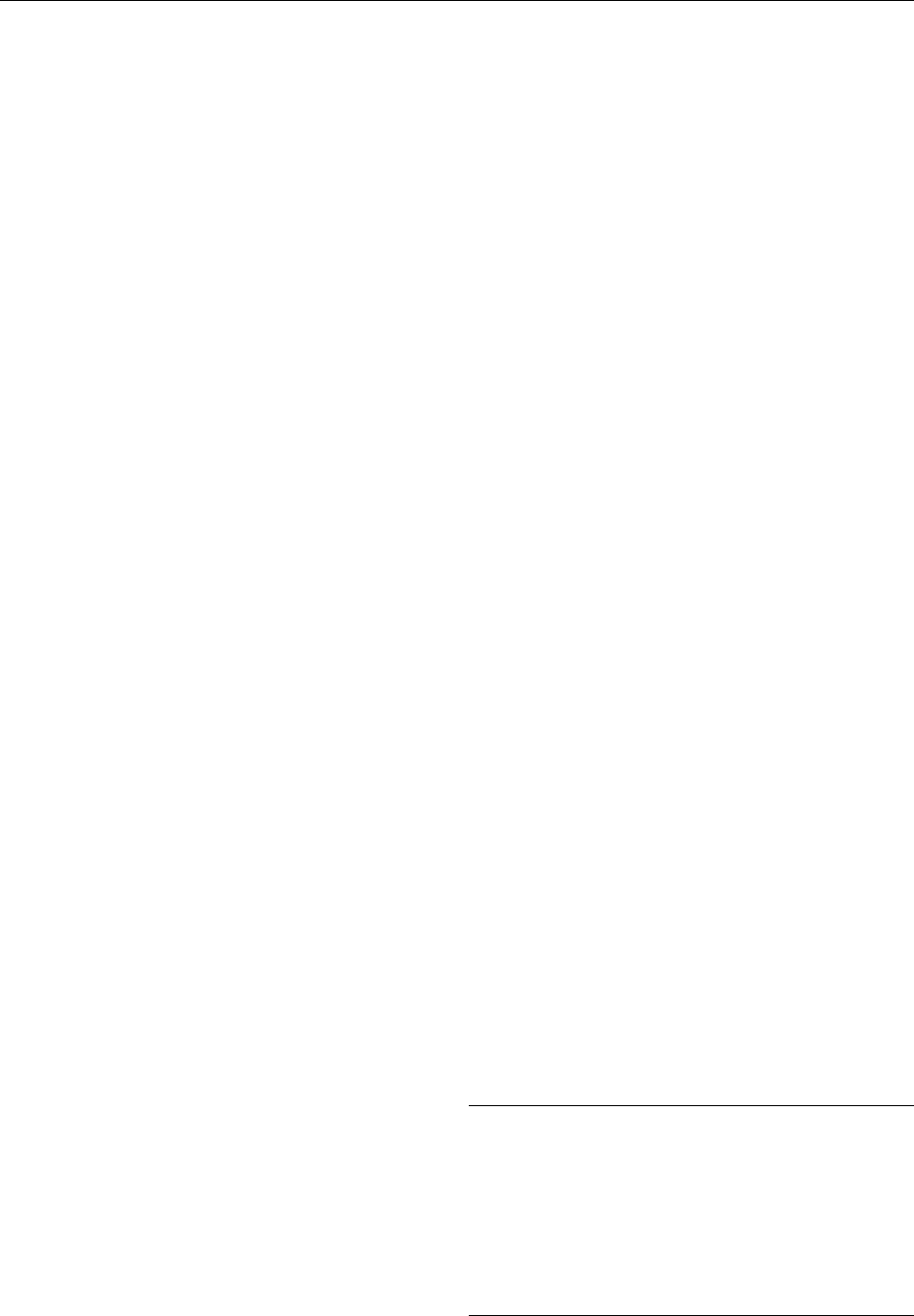

0027Figure 3 shows the trends for Campylobacter infec-

tion in England and Wales. The steady increase in

reports in the early years of its recognition could be

due to increasing numbers of laboratories involved in

testing and reporting. The sensitivity of laboratory

methods has continued to improve, but these data

are also compatible with a real increase in incidence

of the infection in the community.

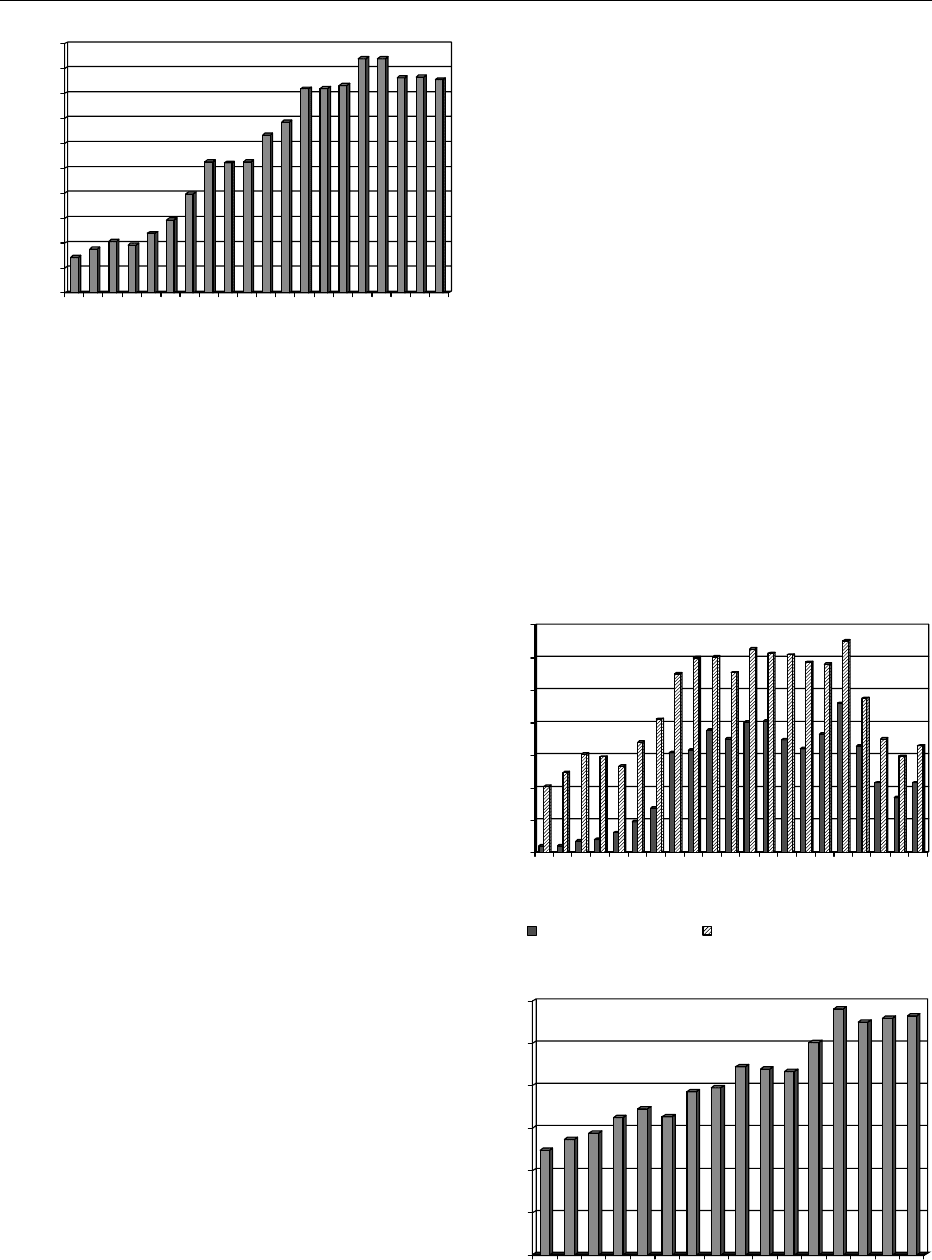

0028Figure 4 shows data for E. coli O157. In the UK,

the incidence of laboratory reported cases rapidly

increased through the 1980s following the first report

in 1982. This was certainly due to increasing numbers

of laboratories introducing screening tests for VTEC.

0

5 000

10 000

15 000

20 000

25 000

30 000

35 000

1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999

fig0002Figure 2 Reports of Salmonella infection in England and

Wales.

: Salmonella enteritidis; : total Salmonellas.

0

10 000

20 000

30 000

40 000

50 000

60 000

1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000

fig0003Figure 3 Reports of Campylobacter infection in England and

Wales.

0

10 000

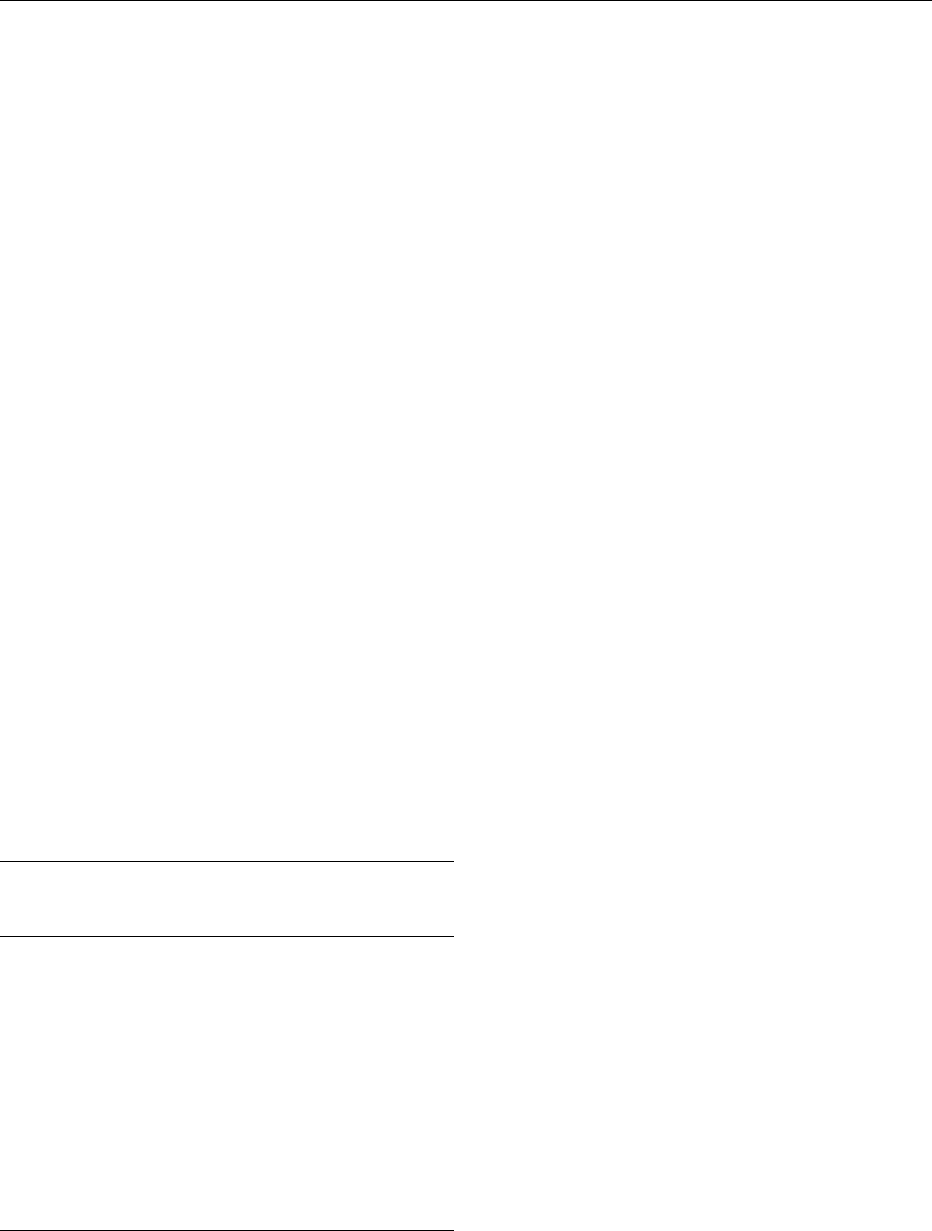

20 000

30 000

40 000

50 000

60 000

70 000

80 000

90 000

100 000

1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000

fig0001 Figure 1 Notifications of food poisoning in England and Wales.

FOOD POISONING/Statistics 2667