Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

COMPARATIVE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 291

Source: Wymeersch (1998: 1189).

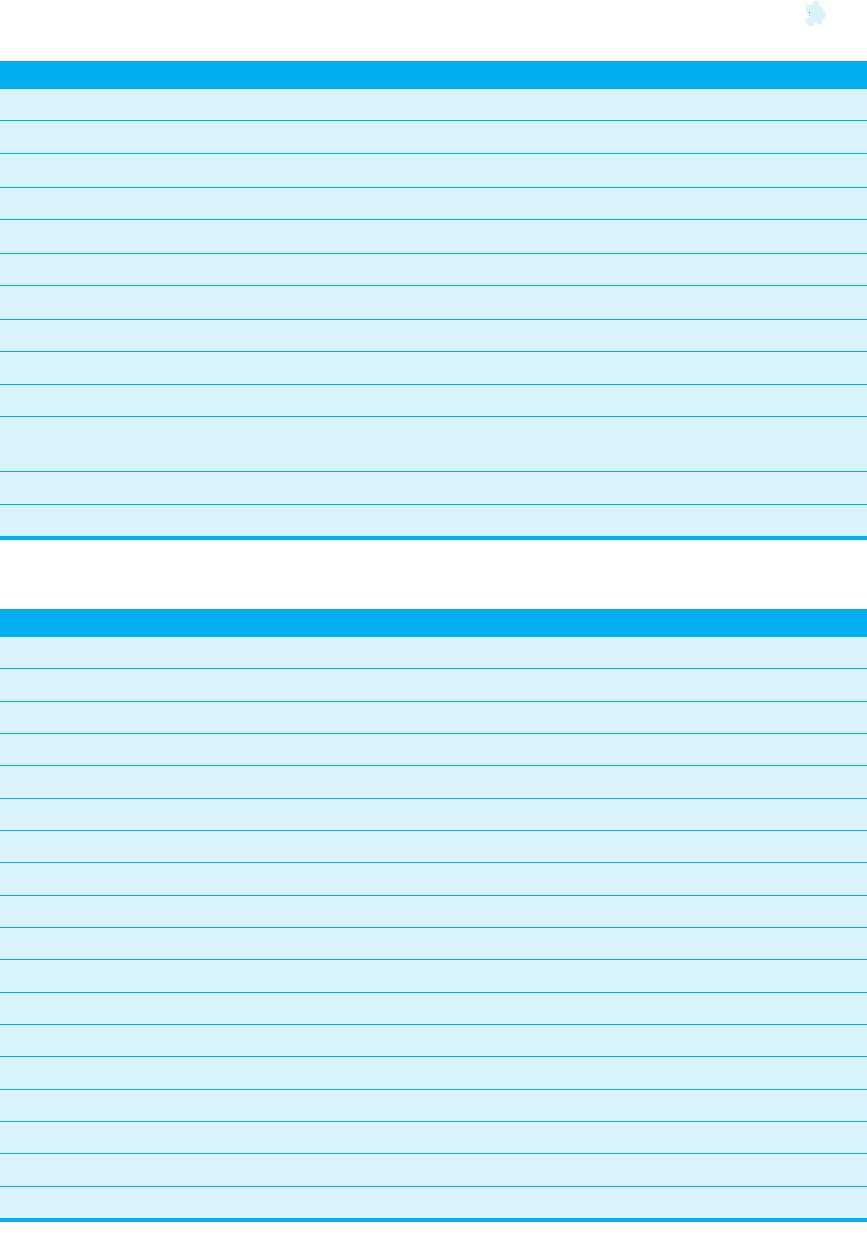

Table 6.7 Mergers and acquisitions in value of transactions ($bn)

Country 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

France 18.9 26.8 21.7 29.8 21.2 20.9

Germany 15.1 20.3 21.4 11.4 10.1 16.5

Italy 20.0 7.5 23.3 16.5 9.0 9.2

UK 77.4 56.6 45.5 42.3 36.4 124.2

Belgium 5.9 3.1 1.0 4.9 1.4 1.6

Netherlands 13.9 5.9 15.5 8.3 5.2 8.5

Spain 8.5 15.5 10.6 9.0 7.3 4.1

Sweden 6.9 11.5 6.9 12.5 7.7 8.8

Switzerland 5.8 0.7 2.2 3.4 2.7 8.2

Rest of

Europe

13.3 12.1 12.0 12.2 10.0 24.3

Europe 185.7 160.0 160.1 150.3 111.0 226.3

USA 108.2 71.2 96.7 176.4 226.7 356.0

Source: Wymeersch (1998: 1190).

Table 6.8 Mergers and acquisitions in number of transactions

Acquisitions Selling transactions

1995 1996 1995 1996

Belgium 49 55 55 89

France 378 343 350 332

Germany 444 450 362 322

Italy 109 130 170 162

Netherlands 273 319 145 136

Spain 32 46 160 107

UK 664 664 449 468

Sweden 93 152 72 120

Switzerland 186 192 76 74

Rest of Europe 365 463 645 745

Europe 2593 2814 2484 2564

Canada 298 323 180 250

USA 1228 1553 699 849

Japan 351 445 89 69

Rest of World 842 817 1890 2220

Total 2719 3138 2858 3388

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 291

292 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Case: Corporate Governance in China

13

F

rom 1978 onwards, the Chinese government embarked on an ambitious

programme of economic reform. One of the most important creations was

that of the firm as an independent business entity. Under the central plan-

ning regime, China’s industrial and commercial enterprises were not

autonomous but were workshops and production units with no independent

decision-making power. The central plan replaced the function of the market, and

the conditions for the existence of a firm (as understood in market economies)

were absent. All means of production were nominally owned by the state; con-

tracts and market transactions were not needed for organizing production

activities.

The workshop and production units within the central input–output planning

matrix have been replaced by business enterprises with independent legal status

(regardless of ownership composition). These have now become the primary form

of productive organization. The emergence of the company as a basic economic

entity was accompanied by a process of financial reform that has turned the newly

created or reorganized state-owned banks into the primary providers of finance

for Chinese enterprises, replacing the old system of state budgetary grants. Most

working capital needs of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are met through bank

lending. The banks were encouraged to use economic criteria for evaluating loan

applications on the basis of market demand for the enterprises’ output, the avail-

ability of raw materials and the profitability of investments. The transformation of

the Chinese banking system into a truly commercial one, however, is proving an

extremely slow process. Some party officials have been reluctant to increase the

independence of the central bank and of other banks because officials have been

exploiting the banks to finance their own needs. The Chinese government also

continues to use the banks to siphon surplus funds from private enterprises to

subsidize the losses of state enterprises. Moreover, the political upheaval and

mass unemployment involved in making the banks themselves efficient further

contribute to slowing the pace of progress. Hence, while banks are technically

more independent, in practice they are to a large extent still acting as cashiers for

the state and can hardly play a useful role in corporate governance.

From the mid-1980s onwards, when grass-roots efforts to develop China’s

capital markets began spontaneously, shareholding companies were formed. To

raise funds, state and collective enterprises issued various forms of shares and

bonds, and informal securities trading could be found in most major Chinese

cities. China’s first securities and brokerage company was established in

Shenzhen in 1987. In the following year, securities companies were set up in every

province under the auspices of the local branches of China’s central bank. By

1991, China’s two official stock exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen were ready

for full operation. Approval for a company to obtain listing on these markets,

however, is determined by the government on the basis of an annual quota broken

13

The majority of the information in this case is based on On Kit Tam (2002), Eu (1996) and Lin (2001).

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 292

COMPARATIVE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 293

down to each province and ministry. The latter then select companies to fill the

allocated quotas. The listing of a company is thus usually decided not on its com-

mercial merit but for political and sectional reasons. Just like the state banking

system, which supports SOEs through the debt market, the securities market in

China is essentially a state securities market, conceived and operated primarily

to support corporatized SOEs.

Chinese-listed companies are in the main partially privatized SOEs. That is,

their major shareholder is the state in its various forms, including other state-

owned enterprises. Shares owned by the state and by state-owned enterprises

are not permitted to be traded. The high degree of concentrated state ownership

has restricted the capacity of China’s equity market to perform a financial disci-

plinary role in the corporate governance of listed firms. Movements in stock price

are generated mainly by the trading of shares among individual shareholders.

Because of the high rate of saving and the very limited range of investment instru-

ments available in China, individual investors in the stock market have from the

beginning exhibited a highly speculative tendency with a very short investment

horizon.

Despite its majority ownership, the state does not exercise effective control

over its companies. Control of China’s companies rests primarily with the insider

management and their party–ministerial associates. The Chinese government,

together with the party organization, exercise influence through, for example,

recruitment policy. For listed companies with the state as a majority shareholder,

the pool for appointment to the positions of chief executive, most senior man-

agers and a high proportion of the directors on the company board is restricted

and subject to government influence or direct intervention. Moreover, many

company executives may still have an affiliation to their previous state organiz-

ation.

In the Chinese system, companies operating under the country’s company

law have a two-tier board. The board of directors is essentially made up of execu-

tive directors. There are few independent directors in Chinese companies. In

addition to the board of directors, Chinese companies also have a supervisory

board. This board is small in size and usually has labour union and major share-

holder representatives. However, it only has a loosely defined monitoring role

over the board of directors and managers, and has not so far played any effective

governance role. The interests of employees are safeguarded primarily by party

representatives in consultation with the controlling shareholder, which is usually

the state.

While there has been progress in developing accounting standards, pro-

fessional organizations and media reports on company activities in China, it is still

a long way from achieving the degree of effectiveness and independence that is

required for the Anglo-Saxon model to work. It is widely believed that false

accounting and financial misreporting are pervasive among Chinese SOEs and

companies. However, as in other emerging markets, particularly those in transi-

tional economies, a company’s reputation for integrity and performance is often not

required in order to raise capital in the stock exchange. Indeed, the unpredictable

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 293

294 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

movements generated by market manipulation may, in fact, at times be applauded

by some investors, who hope to profit from such speculative waves and are eager

to follow the ‘winners’.

Many of the shortcomings in the actual practice of corporate governance in

China derive from weaknesses in the policy and institutional environment, as well

as from peculiar cultural and political governance traditions. For example, collu-

sion among insiders, and lack of transparency and disclosure to outsiders on the

actual performance and workings of the firms have been explained as a conse-

quence of the tradition of insiders versus outsiders with a built-in convention of

secrecy among insiders. Family or clan members, as ‘insiders’, are expected to

bear collective responsibility for promoting and safeguarding the interests of the

unit. The interests of outsiders are either secondary or irrelevant. Safeguarding

the interests of the unit involves maintaining confidentiality on internal affairs,

and disclosures are regarded as a betrayal of the unit’s interests. Also important

is the impact of political governance on corporate governance. Since the Chinese

system of political governance itself lacks accountability and transparency, it is

difficult, and perhaps incongruous, for corporate governance to be effective and

institutionalized. Moreover, the market-orientated legal system, and the cor-

porate and securities law framework in China has only been developed over the

past two decades and is still relatively rudimentary and untested in many aspects.

Questions

1. In an attempt to foster enterprise performance, China increased enterprise

autonomy, decentralizing investment and production decisions. From this

case it is clear, however, that increasing enterprise autonomy might be a

necessary but not sufficient condition to optimize allocative efficiency. What

in your opinion must be developed to achieve this aim?

2. Explain in what direction the Chinese corporate governance and finance

system seems to have evolved – towards a more Anglo-Saxon type of system

or towards the Rhineland system? Use the institutional–cultural framework

to support your explanation.

3. In your opinion, which corporate governance and finance system would be

most beneficial under the current conditions in China?

4. What can you learn from this case with respect to shareholder and other

stakeholder rights?

6.3 Conclusions

The comparative analysis of corporate governance systems and of their institutional–

cultural roots is not only useful in its own right but also for building an understanding of

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 294

the impact these systems might have on competitive advantage of national industries. It

also enables us to make a sensible judgement on the type of system that could best be

developed in less advanced and transitional countries. A comparative analysis of the type

that is conducted in this chapter shows that – aside from economics – history, politics and

societal traditions are important forces in shaping the development of financial and cor-

porate governance institutions. Corporate governance systems do not exist in an

institutional or historical vacuum. The lesson to be learned is that financial and corporate

governance reforms must adapt to the unique history and social–political structure of a

country. Less advanced and transitional countries cannot blindly follow the financial and

corporate governance reforms of other countries.

A striking example in this respect is the advice of the Japanese to top Chinese econ-

omic officials not to hasten the development of securities markets. In their view,

ordinary Chinese people do not yet understand the risks of stocks and bonds.

Moreover, strong securities markets undermine a tool of economic control that

Japan found useful during its own development. The Japanese think China should

keep its firms dependent on bank loans rather than securities, so making it easier

for the government to control who gets capital and when (Eu, 1996).

This chapter also shows that both the Anglo-Saxon and the Rhineland models of cor-

porate governance have their strengths and weaknesses, which help to explain their

divergent impact on industrial competitiveness (see Table 6.9). Major strengths of the

Anglo-Saxon system of corporate governance include efficiency, flexibility, responsiveness

and high rates of corporate profit. More explicitly, the Anglo-Saxon system is good at re-

allocating capital among sectors, funding emerging fields, shifting resources out of

‘unprofitable’ industries, and achieving high private returns each period, as measured by

higher corporate returns (Porter, 1997). Major weaknesses of the system stem essentially

from two of its features: the unitary board system and its short-term character. The

unitary board system, while allowing for efficient decision-making by management,

impedes effective monitoring of management performance. Managerial failures in the UK

during the 1980s and a number of cases of blatant malpractice in the USA and the UK

are an expression of the flaws in this system of corporate control. The election of outside

directors (which happens on a voluntary basis in the UK), the use of proxy voting mech-

anisms, and, as in recent times, the development of shareholder advisory committees

have emerged in the Anglo-Saxon system as preferred techniques for solving many of

these control problems. When these governance techniques fail, corporate control

becomes entirely dependent on the market.

Theoretically, the threat of a hostile take-over should ensure that assets are controlled

by those best able to manage them, and in the USA and UK, with their well-developed

markets for corporate control, a hostile take-over is the ultimate check on management.

When shareholders fail to take an interest in the governance of a company, or when their

governance proves ineffective, low-quality managers are able to remain in power or manage-

ment’s allegiance to the shareholder may falter. In either of these cases, a company’s share

price should drift lower so as to form a gap between the stock’s actual price and its potential

value. If the gap between a company’s market value and its perceived potential value were

to grow large enough, a take-over would ensure that control over the company’s assets

eventually goes to those who can earn a higher return on those assets (Lightfood, 1992).

COMPARATIVE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 295

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 295

Moreover, the unitary board system, combined with the threat of take-over, helps to

explain the difficulty of the Anglo-Saxon system with aligning the interests of private

investors and corporations with those of society as a whole, including employees, suppliers

and local communities. Indeed, the market for corporate control often disregards its effects

on both human and social capital. Short-term capital is also argued to contribute to

impeding the creation of the organizational competencies necessary for firms competing

in sectors characterized by incremental innovation processes (Streeck, 1992). In other

words, the system fails to encourage sufficient investment to secure competitive posi-

tions in existing business. It also induces investments in the wrong forms. It heavily

favours acquisitions, which involve assets that can easily be valued, over internal develop-

ment projects that are more difficult to value and that constitute a drag on current

earnings (Porter, 1997).

Major strengths of the Rhineland model are that it encourages investment to upgrade

capabilities and productivity in existing fields; it also encourages internal diversification

into related fields – the kind of diversification that builds on and extends corporate

strengths. The Rhineland model comes closer to optimizing long-term private and social

returns. The focus on long-term corporate position – encouraged by an ownership struc-

ture and governance process that, together, incorporate the interests of employees,

suppliers, customers and the local community – allows the German economy to utilize

more successfully the social benefits of private investment (Porter, 1997: 12–13).

Downsides of the Rhineland model, however, are the tendency to over-invest in capacity,

to produce too many products, and to maintain unprofitable businesses. Moreover, the

stable, long-term relationships between banks and firms are increasingly seen as

inhibiting the formation and growth of firms in new sectors. As indicated above, the long-

term stable shareholder relationships typical of the Rhineland model impede the

development of a large, liquid capital market. A large capital market is critical for risk

capital or venture capital providers, as it creates a viable ‘exit option’ via initial public

offering (IPO) and mergers or acquisitions (Casper, 1999). Without this exit option, it is

difficult for venture capitalists to diversify risks across several investments and to create a

viable refinancing mechanism.

The comparative approach of this chapter helps reveal the fact that there is no such

a thing as a ‘perfect’ or the ‘best’ system. While, at present, the majority view is that the

shareholder model will prevail due to the increasing dominance of institutional investors

on international capital markets (Lazonick and O’Sullivan, 2000), the intense and

ongoing competition between the Anglo-Saxon and the Rhineland models in Europe pro-

vides evidence to counter this argument. The impact of this competition provides few

signs of change in the UK and only small step-changes, incorporating some elements of

the Anglo-Saxon model into the ‘large firm’ Rhineland model in Germany. Since national

forms of corporate governance are embedded in established ‘practices’ and ‘regulatory

policies’, change in one area does not involve a change in the entire system.

In fact, as the example of Germany shows, modifications of the existing approach to

corporate governance that accommodate the new circumstances are more likely. Real

change would require root-and-branch change, and as there is not even a consensus on

the need for change, let alone a consensus on what that change should be, root-and-

branch change in both the UK and Germany – the European representatives of the two

strongest models of corporate governance – has not yet occured, and is unlikely to. Hence,

296 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 296

COMPARATIVE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 297

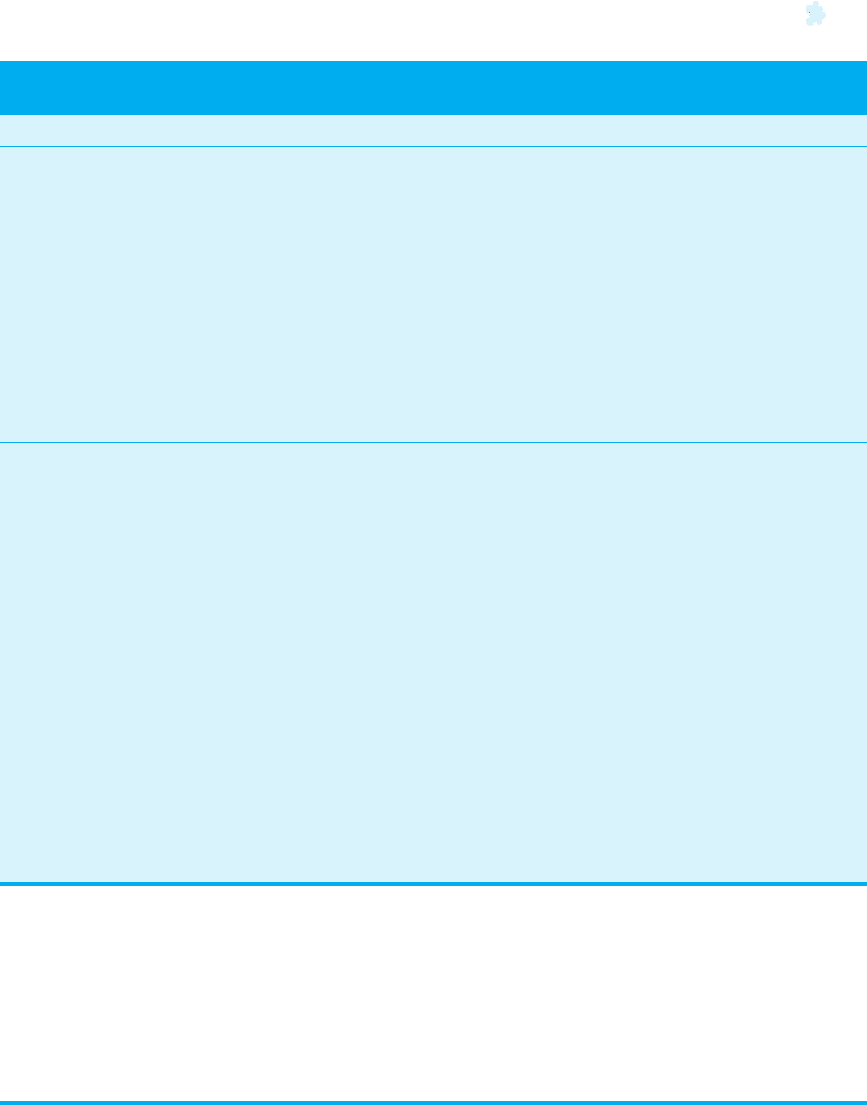

Table 6.9 The Anglo-Saxon and Rhineland models of corporate governance: major

weaknesses and strengths

Anglo-Saxon model Rhineland model

Major strengths

good reallocation of capital

between sectors

funding of emerging fields

shifting resources out of

‘unprofitable’ industries

high rates of profit

efficient decision-making by

management

encourages investment to

upgrade capabilities and

internal diversification in

related fields

utilizes the social benefits of

private investments more

successfully

effective monitoring

Major weaknesses

Stemming from board system

ineffective monitoring

Plus threat of take-over

no incentives to invest in

organizational capabilities

favours acquisitions instead

of internal development

projects

Stemming from stable bank

ties

tendency to over-invest in

capacity

tendency to produce too

many products

tendency to maintain

unprofitable business

tendency to impede the

development of liquid capital

markets and, as a result,

tendency to inhibit the

development and growth of

firms in new sectors

for the foreseeable future, companies within different countries will continue to be char-

acterized by different forms of governance. Evidence shows that there is, and will continue

to be, a spectrum of approaches, ranging from the Anglo-Saxon to the Rhineland model.

Study Questions

1. Explain the main differences between the ‘shareholder’ and the ‘stakeholder’

models of corporate governance.

2. What is the broad definition of corporate governance?

3. What do you understand by ‘effective corporate governance’?

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 297

4. The text gives examples of Ford Motor Company adopting extensive cross-own-

ership relationships through equity holdings and German firms adopting US

financial disclosure practices. Explain why this happens?

5. Explain how the German accounting system differs from the US one.

6. Explain the main differences between the Anglo-Saxon and the Rhineland model

of corporate governance.

7. What are the main strong and weak points of these two main systems of cor-

porate governance?

8. What is meant by the term ‘private’ capital markets?

9. What is meant by the terms ‘exit’ and ‘voice’ in the governance area?

10. What are the main strong and weak points of the Japanese system of corporate

governance?

11. Explain why the take-over option of the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate gover-

nance has militated against enterprise growth from small to medium size.

12. Is the German model converging towards the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate

governance? Give reasons for your argument.

13. Would it be economically beneficial for the German model to converge towards

the Anglo-Saxon model?

14. Which material preconditions are essential for a shareholder value economy?

15. What would you take into account when thinking of a ‘best fit’ model of corporate

governance for developing countries, and why?

16. What is the link between corporate social responsibility and corporate gover-

nance?

17. Explain the effects of globalization forces on corporate governance systems.

Further Reading

Aoki, M. and Kim, Hyung-Ki (1995) Corporate governance in transitional economies.

Washington, DC: World Bank.

Interesting book paying special attention to insider control, the possible role of

banks in corporate governance, and the desirability of taking a comparative analytic

approach to finding solutions.

Hopt, K.J., Kanda, H., Roe, M.J., Wymeersch, E. and Prigge, S. (1998) Comparative

Corporate Governance: the State of the Art and Emerging Research. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Extremely interesting book. It explains a wide range of corporate governance topics

in different countries.

298 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 298

Jürgens, U., Naumann, K. and Rupp, J. (2000) Shareholder value in an adverse

environment: the German case. Economy and Society 29(1), 54–79.

This article provides an interesting analysis of the ability of the German corporate

governance system to change in the direction of shareholder value.

Sheard, P. (1998) Japanese corporate governance in comparative perspective.

Journal of Japanese Trade and Industry 1, 7–11.

This article offers a brief but critical comparative analysis of the Japanese and

Anglo-Saxon systems of corporate governance.

Zhuang, J., Edwards, D. and Capulong, V.A. (2001) Corporate Governance and Finance

in East Asia: a Study of Indonesia, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand.

Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

One of the few and excellent books that treats the topic extensively in these East

Asian countries.

COMPARATIVE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 299

Case: Barings – a Case of Corporate Social

Responsibility

14

A

t the time of its collapse, Baring Brothers & Co., Ltd (BB&Co) was the

longest-established merchant banking business in the City of London.

Since the foundation of the business as a partnership in 1762 it had been

privately controlled and had remained independent. BB&Co was founded in 1890

to carry on the business of the bank in succession to the original partnership. In

November 1985, Barings plc acquired the share capital of BB&Co and became the

parent company of the Barings Group.

In addition to BB&Co, the two other principal operating companies of Barings

plc were Barings Asset Management Limited (BAM), which provided a wide range

of fund and asset management services, and Barings Securities Limited (BSL),

itself a subsidiary of BB&Co, which generally operated through subsidiaries as a

broker dealer in the Asia Pacific region, Japan, Latin America, London and New

York.

The business of what became BSL was acquired from Henderson Crosthwaite

by BB&Co in 1984. BSL was incorporated in the Cayman Islands, although its

head office, management and accounting records were all based in London. BSL

had a large number of overseas operating subsidiaries, including two that are of

particular relevance to this case study, namely Baring Futures (Singapore) (BFS)

and Baring Securities (Japan) Limited (BSJ).

BFS, a Singaporean-registered company, was an indirect subsidiary of BSL.

BFS was originally formed to allow Barings to trade on the Singapore Inter-

national Monetary Exchange. At the time of the collapse, BFS employed 23 staff.

BSL’s other significant Singaporean subsidiary was Baring Securities (Singapore)

14

This case is based on information from the website risk.ifci.ch.

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 299

300 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Pte Limited (BSS), which employed some 115 staff. BSS’s principal activity was

securities trading.

From late 1992 to the time of the collapse, BFS’s general manager and head

trader was Nick Leeson. Leeson started work for Barings in London in 1989 in a

back office capacity (the settlements department). In 1992, he transferred to

Barings Futures Singapore. He would occupy the same position and in addition he

would also become floor manager of SIMEX (the Securities and Futures Authority

of Singapore). As time went by, Leeson was also put in charge of both the dealing

desk and the back office, settling his own trades.

The back office records, confirms and settles trades transacted by the front

office, reconciles them with details sent by the bank’s counter-parties and

assesses the accuracy of prices used for its internal valuations. It also accepts

and releases securities and payments for trades. Some back offices also provide

the regulatory reports and management accounting. In a nutshell, the back office

provides the checks necessary to prevent unauthorized trading and minimize the

potential for fraud and embezzlement. Since Leeson was in charge of the back

office, he had the final say on payments, ingoing and outgoing confirmations and

contracts, reconciliation statements, accounting entries and position reports. He

was perfectly placed to relay false information back to London.

Leeson engaged in unauthorized activities almost as soon as he started

trading in Singapore in 1992. He took proprietary (that is, trading for own or, in

this case, for Barings’ account) positions on SIMEX on both futures and options

contracts. His mandate from London allowed him to take positions only if they

were part of ‘switching’ (a form of arbitrage trading) and to execute client orders.

He was never allowed to sell options. Leeson lost money from his unauthorized

trades almost from day one. Yet he was perceived in London as a wonderboy and

turbo-arbitrageur, who single-handedly contributed to half of Barings Singa-

pore’s 1993 profits and half of the entire firm’s 1994 profits. However, in 1994

alone, Leeson lost US$296 million; his bosses thought he made a profit of US$46

million, so they proposed paying him a bonus of US$720,000. However, the unau-

thorized trading activities within BFS, which intensified in January and February

1995, built up such massive losses that, when discovered on 23 February 1995,

they led to the collapse of Barings.

Leeson was able to deceive everyone around him by using the vehicle of cross-

trade. A cross trade is a transaction executed on the floor of an exchange by just

one member, who is both buyer and seller. If a member has matching buy and sell

orders from two different customer accounts for the same contract and at the

same price, he is allowed to cross the transaction (execute the deal) by matching

both his clients’ accounts. Leeson entered into a significant volume of cross-

transactions between account ‘88888’, an account which he set up, and account

‘92000’ (Barings Securities Japan – Nikkei and JGB Arbitrage), account ‘98007’

(Barings London – JGB Arbitrage) and account ‘98008’ (Barings London – Euroyen

Arbitrage). The bottom line of all the cross-trades, which Leeson executed, was

that Barings was counter-party to many of its own trades. Leeson bought from

one hand and sold to the other, and in doing so did not lay off any of the firm’s

MG9353 ch06.qxp 10/3/05 8:45 am Page 300