Dinc Ibrahim. Refrigeration systems and applications 2th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Refrigerants 101

Stratospheric Ozone Layer

2.18 What is UVB? What are the harmful effects of UVB?

2.19 What is ozone? What is ozone layer? What is the effect of ozone layer on UVB?

2.20 What is column ozone? What is DU used for? What does a 300 DU mean?

2.21 What is the stratospheric ozone layer depletion? What are the ODS? What are the conse-

quences of the stratospheric ozone layer depletion?

2.22 What are the common ozone-depleting substances? How do they deplete ozone?

2.23 Which substance in CFCs is responsible for ozone depletion? Do HCFCs and HFCs deplete

ozone?

2.24 What is ODP? What is the ODP of R-11? What are the typical ODP ranges of CFCs,

HCFCs, halons, and HFCs?

2.25 R134a is commonly used as refrigerant in household refrigerators. What is the ODP of

R-134a?

2.26 What is the Montreal Protocol? What were the outcomes of this protocol?

Greenhouse Effect (Global Climate Change)

2.27 What are the greenhouse effect and the global warming? Which substances cause greenhouse

effect?

2.28 What is GWP? What are the GWP of CO

2

, R-11, R-12, and water?

2.29 What are the GWP and ODP characteristics of HCs and HFCs?

Clean Air Act

2.30 What is CAA? What were the outcomes of this act?

Alternative Refrigerants

2.31 Why are alternative refrigerants required?

2.32 Why was R-134a developed? What are the applications of R-134a?

2.33 What replacements are done during retrofitting to R-134a?

2.34 When a system using R-12 is retrofitted to R-134a, do compressor, condenser, and evaporator

need to be replaced? What is the amount of R-134a that needs to be charged in comparison

with the amount of R-12?

2.35 What are the suitable applications of R-123? It is used for the replacement of which refrig-

erant? What are the ODP and GWP of R-123?

2.36 What are the advantages of using ammonia as refrigerant?

102 Refrigeration Systems and Applications

2.37 Despite its superior characteristics as a refrigerant, why is ammonia not used in household

refrigerators?

2.38 What are the dangers associated with using ammonia as a refrigerant? Assess the level of

risks involved.

2.39 What are the suitable refrigeration applications of ammonia?

2.40 Compare propane to ammonia as a refrigerant in terms of thermodynamic properties and

risks associated with its use. What have been the applications of propane?

2.41 It is known that carbon dioxide (CO

2

) emission is responsible for at least 50% of greenhouse

emissions. Do we need to be concerned about GWP of CO

2

when using it as a refrigerant?

What is the ODP of CO

2

?

Selection of Refrigerants

2.42 What are some criteria that need to be considered in the selection of a refrigerant?

2.43 A refrigerator using R-134a is used to maintain a space at −6

◦

C. Would you recommend

an evaporator pressure of 140, 200, or 240 kPa? Why?

2.44 A refrigerator using R-134a is used to maintain a space at −6

◦

C while rejecting heat to a

reservoir at 30

◦

C. Would you recommend a condenser pressure of 700, 850, or 1000 kPa?

Why?

2.45 A refrigerator using R-134a is used to maintain a space at 0

◦

C while rejecting heat to a

reservoir at 14

◦

C. If a temperature difference of 10

◦

C is desired, which evaporating and

condensing pressures should be used?

2.46 A heat pump using R-134a is used to maintain a space at 25

◦

C while absorbing heat from

amediumat5

◦

C. If a temperature difference of 5

◦

C is desired, which evaporating and

condensing pressures should be used?

2.47 The evaporator and condenser pressures of an R-134a refrigerator are 200 kPa and 600 kPa,

respectively. Heat is rejected to lake water running through the condenser. If water enters

the condenser at 12

◦

C, what is the maximum temperature rise of water in the condenser?

2.48 It is known that lower temperatures in the condenser (thus higher COPs) can be maintained

if the refrigerant is cooled by a lower temperature medium such as liquid water. Based on

this, would you recommend designing a household refrigerator with water cooling for the

condenser? Explain.

Thermophysical Properties of Refrigerants

2.49 Determine surface tension of R-134a at −20, 0, and 20

◦

C.

Lubricating Oils and Their Effects

2.50 What is oil miscibility? How may refrigerants be grouped in terms of oil miscibility?

2.51 Compare the amount of oil in the refrigerant for ammonia and HCs.

Refrigerants 103

References

Anon. (1991) R123 – A promising future. Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, July, 32–33.

Badr, O., Probert, S.D. and O’Callaghan, P.W. (1990) Chlorofluorocarbons and the environment: scientific,

economic, social and political issues. Applied Energy, 37, 247–327.

Cengel, Y.A. and Boles, M.A. (2008) Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Cleland, A.C. (1986) Computer subroutines for rapid evaluation of refrigerant thermodynamic properties. Inter-

national Journal of Refrigeration, 9, 346–351.

Dincer, I. (1992) Chlorofluorocarbons and environment: I (in Turkish). Bulten, 1 (1), 7–8.

Dincer, I. (1997) Heat Transfer in Food Cooling Applications, Taylor & Francis, Washington, DC.

Dincer, I. (2003) Refrigeration Systems and Applications, 1st edn John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., New York.

Dossat, R.J. (1997) Principles of Refrigeration, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

EPA (2009) Significant New Alternatives Policy, under section 612 of the Clean Air Act Amendments, United

States Environmental Protection Agency.

Heide, R. and Lippold, H. (1990) Thermophysical Properties of the Refrigerants R134a and R152a, Proceedings

of the Meeting of I.I.R. Commissions B2, C2, D1, D2/3, September 24–28, Dresden, Germany, pp. 237–240.

Hickman, K.E. (1994) Redesigning equipment for R-22 and R-502 alternatives. ASHRAE Journal, 36, 42–47.

James, R.W. and Missenden, J.F. (1992) The use of propane in domestic refrigerators. International Journal of

Refrigeration, 15 (2), 95–100.

Konig, H. (1996) Performance Comparison of R-507 and R-404A in a Cold Store Refrigeration Installation,

Solvay Fluor und Derivate GmbH, Product Bulletin No: C/04.96/01/E.

Kramer, D.E. (1999) CFC to HFC conversion issues. Why not mineral oil? ASHRAE Journal, 41, 19–28.

Lorentzen, G. (1988) Ammonia, an excellent alternative. International Journal of Refrigeration, 11 (4), 248–252.

Lorentzen, G. (1993) Application of Natural Refrigerants, Proceedings of the Meeting of I.I.R. Commission

B1/2, May 12–14, Ghent, Belgium, pp. 55–64.

Pearson, S.F. (1991) Which refrigerant? Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, July, 21–23.

Pederson, P.H. (2001) Ways of Reducing Consumption and Emission of Potent Greenhouse Gases (HFCs, PFCs

and SF6), Project for the Nordic Council of Ministers, DTI Energy, Denmark.

Rowland, F.S. (1991) Stratospheric ozone depletion. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 42, 731–734.

Watanabe, K. and Sato, H. (1990) Thermophysical Properties Research on Environmentally Acceptable Refrig-

erants, Proceedings of the Meeting of I.I.R. Commission B1, March 5–7, Herzlia, Israel, pp. 29–36.

Wayne, R.P. (1991) Chemistry of Atmospheres, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

3

Refrigeration System Components

3.1 Introduction

Refrigeration is the process of removing heat from matter which may be a solid, a liquid, or

a gas. Removing heat from the matter cools it, or lowers its temperature. There are a number

of ways of lowering temperatures, some of which are of historical interest only. In some older

methods, lowering of temperature may be accomplished by the rapid expansion of gases under

reduced pressures. Thus, cooling may be brought about by compressing air, removing the excess

heat produced in compressing it, and then permitting it to expand.

A lowering of temperatures is also produced by adding certain salts, such as sodium nitrate,

sodium thiosulfate (hypo), and sodium sulfite to water. The same effect is produced, but to a lesser

extent, by dissolving common salt or calcium chloride in water.

As known, two common methods of refrigeration are natural and mechanical. In the natural

refrigeration, ice has been used in refrigeration since ancient times and it is still widely used. In

this natural technique, the forced circulation of air passes around blocks of ice. Some of the heat

of the circulating air is transferred to the ice, thus cooling the air, particularly for air-conditioning

applications. In the mechanical refrigeration, the refrigerant is a substance capable of transferring

heat that it absorbs at low temperatures and pressures to a condensing medium; in the region of

transfer, the refrigerant is at higher temperatures and pressures. By means of expansion, compres-

sion, and a cooling medium, such as air or water, the refrigerant removes heat from a substance

and transfers it to the cooling medium.

In this chapter, we provide information on refrigeration system components (e.g., compressors,

condensers, evaporators, throttling devices) and discuss various technical and operational aspects.

Auxiliary refrigeration system components are also covered.

3.2 History of Refrigeration

For centuries, people have known that the evaporation of water produces a cooling effect. At first,

they did not attempt to recognize and understand the phenomenon, but they knew that any portion

of the body that became wet felt cold as it dried in the air. At least as early as the second century,

evaporation was used in Egypt to chill jars of water, and it was employed in ancient India to make

ice (Neuberger, 1930).

The first attempts to produce refrigeration mechanically depended on the cooling effects of

the evaporation of water. In 1755, William Cullen, a Scottish physician, obtained sufficiently

low temperatures for ice making. He accomplished this by reducing the pressure on water in

Refrigeration Systems and Applications

˙

Ibrahim Dinc¸er and Mehmet Kano

ˇ

glu

2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

106 Refrigeration Systems and Applications

a closed container with an air pump. At a very low pressure the liquid evaporated or boiled

at a low temperature. The heat required for a portion of water to change phase from liquid to

vapor was taken from the rest of the water, and at least part of the water remaining turned to

ice. Since Cullen, many engineers and scientists have created a number of inventions for clari-

fying the main principles of mechanical refrigeration (Goosman, 1924). In 1834, Jacob Perkins,

an American residing in England, constructed and patented a vapor-compression machine with a

compressor, a condenser, an evaporator, and a cock between the condenser and the evaporator

(Critchell and Raymond, 1912). He made it by evaporating under reduced pressure a volatile

fluid obtained by the destructive distillation of India rubber. It was used to produce a small

quantity of ice, but not commercially. Growing demand over the 30 years after 1850 brought

great inventive accomplishments and progress. New substances, for example, ammonia and carbon

dioxide, which were more suitable than water and ether, were made available by Faraday, Thilo-

rier, and others, and they demonstrated that these substances could be liquefied. The theoretical

background required for mechanical refrigeration was provided by Rumford and Davy, who had

explained the nature of heat, and by Kelvin, Joule, and Rankine, who were continuing the work

begun by Sadi Carnot in formulating the science of thermodynamics (Travers, 1946). Refrigerating

machines appeared between 1850 and 1880, and these could be classified according to the substance

(refrigerant). Machines using air as a refrigerant were called compressed-air or cold-air machines

and played a significant role in refrigeration history. Dr John Gorrie, an American, developed a

real commercial cold-air machine and patented it in England in 1950 and in America in 1951

(DOI, 1952).

Refrigerating machines using cold air as a refrigerant were divided into two types, closed cycle

and open cycle. In the closed cycle, air confined to the machine at a pressure higher than the

atmospheric pressure was utilized repeatedly during the operation. In the open cycle, air was

drawn into the machine at atmospheric pressure and, when cooled, was discharged directly into the

space to be refrigerated. In Europe, Dr Alexander C. Kirk commercially developed a closed-cycle

refrigerating machine in 1862, and Franz Windhausen invented a closed-cycle machine and patented

it in America in 1870. The open-cycle refrigerating machines theoretically outlined by Kelvin and

Rankine in the early 1850s were invented by a Frenchman, Paul Giffard, in 1873 and by Joseph J.

Coleman and James Bell in Britain in 1877 (Roelker, 1906).

In 1860, a French engineer, Ferdinand P. Edmond Carre, invented an intermittent crude ammonia

absorption apparatus based on the chemical affinity of ammonia for water, which produced ice on

a limited scale. Despite its limitations, it represented significant progress. His apparatus had a hand

pump and could freeze a small amount of water in about 5 minutes (Goosman, 1924). It was

widely used in Paris for a while, but it suffered from a serious disadvantage in that the sulfuric

acid quickly became diluted with water and lost its affinity. The real inventor of a small, hand-

operated absorption machine was H.A. Fleuss, who designed an effective pump for this machine.

A comparatively large-scale ice-making absorption unit was constructed in 1878 by F. Windhausen.

It operated continuously by drawing water from sulfuric acid with additional heat to increase the

affinity (Goosman, 1924).

One of the earliest of the vapor-compression machines was invented and patented by an Amer-

ican professor, Alexander C. Twining, in 1853. He established an ice production plant using this

system in Cleveland, Ohio, and could produce close to a ton per day. After that, a number of

other inventors experimented with vapor-compression machines which used ether or its compounds

(Woolrich, 1947). In France, F.P.E. Carre developed and installed an ether-compression machine

and Charles Tellier (who was a versatile pioneer of mechanical refrigeration) constructed a plant

using methyl ether as a refrigerant. In Germany, Carl Linde, financed by brewers, established a

methyl ether unit in 1874. Just before this, Linde had paved the way for great improvements

in refrigerating machinery by demonstrating how its thermodynamic efficiency could be calcu-

lated and increased (Goosman, 1924). Inventors of compression machines also experimented with

ammonia, which became the most popular refrigerant and was used widely for many years. In

Refrigeration System Components 107

the 1860s, Tellier developed an ammonia-compression machine. In 1872, David Boyle made

satisfactory equipment for ice making and patented it in 1872 in America. Nevertheless, the

most important figure in the development of ammonia-compression machines was Linde, who

obtained a patent in 1876 for the one which was installed in Trieste brewery the following year.

Later, Linde’s model became very popular and was considered excellent in its mechanical details

(Awberry, 1942). The use of ammonia in the compression refrigerating machines was a signifi-

cant step forward. In addition to its thermodynamic advantage, the pressures it required were easy

to produce, and machines which used it could be small in size. In the late 1860s, P.H. Van der

Weyde of Philadelphia got a patent for a compression unit which featured a refrigerant composed of

petroleum products (Goosman, 1924). In 1875, R.P. Pictet at the University of Geneva introduced

a compression machine that used sulfuric acid. In 1866, T.S.C. Lowe, an American, developed

refrigerating equipment that used carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide compression machines became

important, because of the gas’ harmlessness, in installations where safety was the primary con-

cern, although they were not used extensively until the 1890s (Awberry, 1942). Between 1880 and

1890, ammonia-compression installations became more common. By 1890, mechanical refrigera-

tion had proved to be both practical and economical for the food refrigeration industry. Europeans

provided most of the theoretical background for the development of mechanical refrigeration, but

Americans participated vigorously in the widespread inventive activity between 1850 and 1880

(Dincer, 1997; 2003).

Steady technical progress in the field of mechanical refrigeration marked the years after 1890.

Revolutionary changes were not the rule, but many improvements were made, in several countries, in

the design and construction of refrigerating units, as well as in their basic components, compressors,

condensers, and evaporators.

3.3 Main Refrigeration Systems

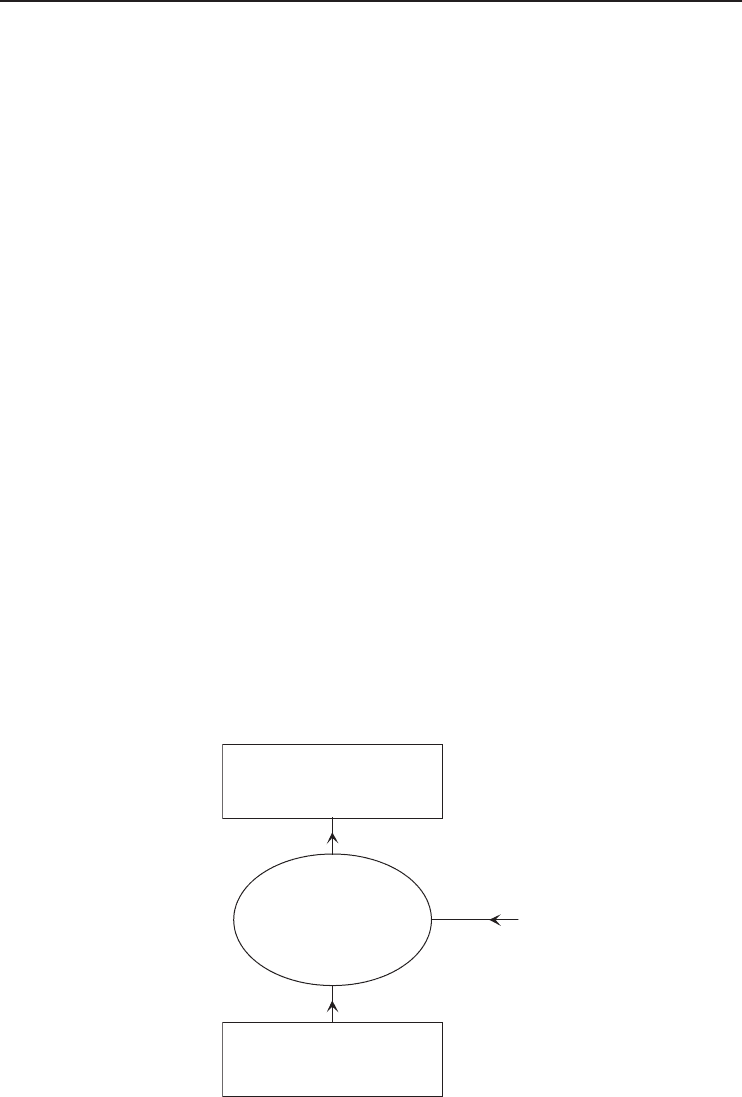

The main goal of a refrigeration system which performs the reverse effect of a heat engine is to

remove the heat from a low-level temperature medium (heat source) and to transfer this heat to a

higher level temperature medium (heat sink). Figure 3.1 shows a thermodynamic system acting as

Heat source

T

L

Work input

Heat transfer

Heat transfer

Q

L

Q

H

W

Heat sink

T

H

System

(Refrigerator)

·

·

·

Figure 3.1 A thermodynamic system acting as a refrigerator.

108 Refrigeration Systems and Applications

a refrigeration machine. The absolute temperature of the source is T

L

and the heat transferred from

the source is the refrigeration effect (refrigeration load) Q

L

. On the other side, the heat rejection

to the sink at the temperature T

H

is Q

H

. Both effects are accomplished by the work input W .For

continuous operation, the first law of thermodynamics is applied to the system.

Refrigeration is one of the most important thermal processes in various practical applications,

ranging from space conditioning to food cooling. In these systems, the refrigerant is used to

transfer the heat. Initially, the refrigerant absorbs heat because its temperature is lower than

the heat source’s temperature and the temperature of the refrigerant is increased during the pro-

cess to a temperature higher than the heat sink’s temperature. Therefore, the refrigerant delivers

the heat.

In this chapter, the main refrigeration systems and cycles that we deal with are

• vapor-compression refrigeration systems,

• absorption refrigeration systems,

• air-standard refrigeration systems,

• jet ejector refrigeration systems,

• thermoelectric refrigeration, and

• thermoacoustic refrigeration.

Before commencing on these refrigeration systems, we first introduce the refrigeration system

components and discuss their technical and operational aspects.

3.4 Refrigeration System Components

There are several mechanical components required in a refrigeration system. In this part, we discuss

the four major components of a system and some auxiliary equipment associated with these major

components. These components include condensers, evaporators, compressors, refrigerant lines and

piping, refrigerant capacity controls, receivers, and accumulators.

Major components of a vapor-compression refrigeration system are as follows:

• compressor,

• condenser,

• evaporator, and

• throttling device.

In the selection of any component for a refrigeration system, there are a number of factors that

need to be considered carefully, including

• maintaining total refrigeration availability while the load varies from 0 to 100%;

• frost control for continuous performance applications;

• variations in the affinity of oil for refrigerant caused by large temperature changes, and oil

migration outside the compressor crankcase;

• selection of cooling medium: (i) direct expansion refrigerant, (ii) gravity or pump recirculated

or flooded refrigerant, or (iii) secondary coolant (brines, e.g., salt and glycol);

• system efficiency and maintainability;

• type of condenser: air, water, or evaporatively cooled;

• compressor design (open, hermetic, semihermetic motor drive, reciprocating, screw, or rotary);

• system type (single stage, single economized, compound or cascade arrangement); and

• selection of refrigerant (note that the type of refrigerant is basically chosen based on operating

temperature and pressures).

Refrigeration System Components 109

3.5 Compressors

In a refrigeration cycle, the compressor has two main functions within the refrigeration cycle. One

function is to pump the refrigerant vapor from the evaporator so that the desired temperature and

pressure can be maintained in the evaporator. The second function is to increase the pressure of the

refrigerant vapor through the process of compression, and simultaneously increase the temperature

of the refrigerant vapor. By this change in pressure the superheated refrigerant flows through

the system.

Refrigerant compressors, which are known as the heart of the vapor-compression refrigeration

systems, can be divided into two main categories:

• displacement compressors and

• dynamic compressors.

Note that both displacement and dynamic compressors can be hermetic, semihermetic, or open

types.

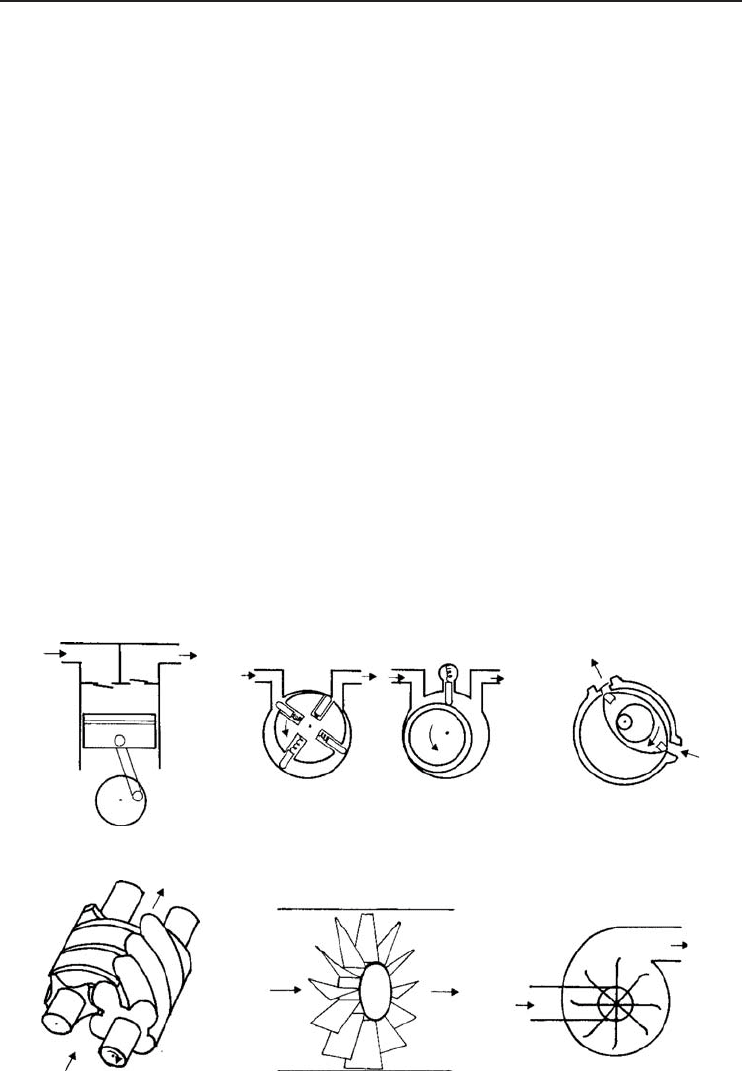

The compressor both pumps refrigerant round the circuit and produces the required substantial

increase in the pressure of the refrigerant. The refrigerant chosen and the operating temperature

range needed for heat pumping generally lead to a need for a compressor to provide a high pressure

difference for moderate flow rates, and this is most often met by a positive displacement compressor

using a reciprocating piston. Other types of positive displacement compressor use rotating vanes or

cylinders or intermeshing screws to move the refrigerant. In some larger applications, centrifugal

or turbine compressors are used, which are not positive displacement machines but accelerate the

refrigerant vapor as it passes through the compressor housing. These various compressor types are

illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Reciprocating

Rotary vane

Wankel

Screw Turbine

Centrifugal

Figure 3.2 Compressor types (Heap, 1979).

110 Refrigeration Systems and Applications

In the market, there are many different types of compressors available, in terms of both enclo-

sure type and compression system. Here are some options for evaluating the most common types

(DETR, 1999):

• Reciprocating compressors are positive displacement machines, available for every application.

The efficiency of the valve systems has been improved significantly on many larger models.

Capacity control is usually by cylinder unloading (a method which reduces the power consump-

tion almost in line with the capacity).

• Scroll compressors are rotary positive displacement machines with a constant volume ratio. They

have good efficiencies for air conditioning and high-temperature refrigeration applications. They

are only available for commercial applications and do not usually have inbuilt capacity control.

• Screw compressors are available in large commercial and industrial sizes and are generally fixed

volume ratio machines. Selection of a compressor with the incorrect volume ratio can result in a

significant reduction in efficiency. Part-load operation is achieved by a slide valve or lift valve

unloading. Both types give a greater reduction in efficiency on part load than the reciprocating

capacity control systems.

Expectations from the compressors

The refrigerant compressors are expected to meet the following requirements:

• high reliability,

• long service life,

• easy maintenance,

• easy capacity control,

• quiet operation,

• compactness, and

• cost effectiveness.

Compressor selection criteria

In the selection of a proper refrigerant compressor, the following criteria are considered:

• refrigeration capacity,

• volumetric flow rate,

• compression ratio, and

• thermal and physical properties of the refrigerant.

3.5.1 Hermetic Compressors

Compressors are preferable on reliability grounds to units primarily designed for the smaller range

of temperatures required in air conditioning or cooling applications. In small equipment where cost

is a major factor and on-site installation is preferably kept to a minimum, such as hermetically

sealed motor/compressor combinations (Figure 3.3), there are no rotating seals separating motor

and compressor, and the internal components are not accessible for maintenance, the casing being

factory welded.

In these compressors, which are available for small capacities, motor and drive are sealed in

compact welded housing. The refrigerant and lubricating oil are contained in this housing. Almost

all small motor-compressor pairs used in domestic refrigerators, freezers, and air conditioners are

of the hermetic type. An internal view of a hermetic-type refrigeration compressor is shown in

Figure 3.3. The capacities of these compressors are identified with their motor capacities. For