Drinkwater J.F. The Alamanni and Rome 213-496 (Caracalla to Clovis)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

he conducted his Wnal dealings with Macrianus of the Bucino-

bantes from a vessel.210 Valentinian, therefore, has some claim to be

regarded as Rome’s Wrst ‘sailor emperor’. His naval concerns have

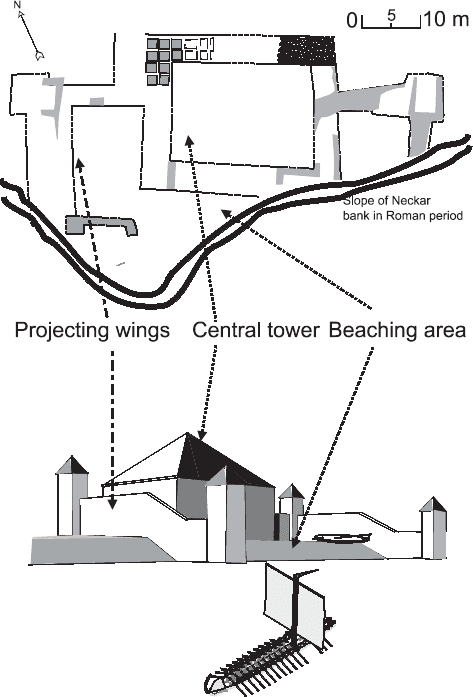

Fig. 24 The ‘SchiVsla

¨

nde’ at Mannheim-Neckarau. Upper: remains of

foundations. Lower: reconstruction [from Pabst (1989: 379 Fig. 6); ß Frau

Prof. Angela Pabst], with lusoriae [ß Prof. Dr. C. Scha

¨

fer].

210 Above 285, below 309.

298 ConXict 365–94

been further argued by Ho

¨

ckmann, who proposes that the distribution

of Valentinian’s riverside left-bank forts indicates that these too had a

primarily naval role. Each was home to a small (c.5–6 vessels) Xeet of

lusoriae, policing a short (c.33 km/20 statute mile-long) stretch of

the Rhine and its major tributaries. The forts were a key element

in a naval defence system in which the ‘SchiVsla

¨

nden’ had only a

subsidiary role.211

What was the purpose of this system? We must distinguish care-

fully between strategical and tactical considerations and, in respect of

the former, between how Valentinian’s strategy was presented and its

likely practical aim. Valentinian never intended to conquer the

Alamanni. He favoured short, focused campaigns, close to home.

However, conquest was the traditional Roman way of dealing with an

intractable enemy: the one which would have been expected of

Valentinian and which, to a large degree, he would have expected

of himself. He therefore pursued a defensive strategy, but presented it

as conquest.212 It was for this reason that Symmachus projected

Valentinian’s right-bank sor ties and the building of ‘SchiV sla

¨

nden’

as the extension of empire, which might (though not necessarily

immediately) lead to the creation of a province of ‘Alamannia’.213

Symmachus treats imperium as other than the direct control of

territory. Deploying an extended conceit, by which non-belligerent

neighbours are peaceful neighbours and therefore subject neigh-

bours, he claims that it is precisely by not subduing the Alamanni

by force but by exercising clementia (and by practising diplomacy

with the Burgundians), that the emperor could pacify, dominate and

even Romanize them. Imperium no longer produced pax; rather pax

was imperium. This allows Symmachus to maintain Roman claims of

world rule and aspirations to world domination.214 It also allows him

to present the Alamannic ‘wars’ of his day, which were no more than

expulsions of raiders and minor frontier skirmishes, as campaigns of

211 Ho

¨

ckmann (1986: 397–9, 402–7).

212 Asche (1983: 29, 50).

213 Symmachus, Orat. 2.31.

214 Asche (1983: 11–28, 31–2, 35–6, 42–5, 61, 73, 87, 90, 93, 96–108, 140–4). See

Sogno (forthcoming) for Symmachus’ stress on clementia as possible covert criticism

of Valentinian.

ConXict 365–94 299

conquest.215 And, Wnally, it allows him to develop a further conceit:

that Valentinian’s ‘SchiVsla

¨

nden’ were new ‘cities’ (civitates, oppida,

urbes), cowing Alamanni and impressing Burgundians.216 This ver-

sion of events will have been highly gratifying to domestic audiences.

The notion of a Roman presence on the right bank of the Rhine had

been popular since the days of Julius Caesar. Most recently, it had

been bruited by Julian.217 Satisfaction at Valentinian’s arrival on the

Neckar and, later, at the Danube source must have been compounded

by news of developments in Alamannia. Certainly, the idea of right-

bank fortiWcations appears to have touched a chord with fourth-

century writers who projected it back as an achievement of the ‘good’

emperors of the third-century Crisis.218

Some detect a core of substance in imperial propaganda. Lander

and Pabst, interpreting the beaching areas as tactical bridgeheads, saw

them as a means of expediting Roman amphibious expeditions, and

therefore aggressive in purpose: ‘Valentinian’s frontier system

included an oVensive component.’219 Pabst even proposes that

Valentinian was bent on some real extension of Roman power/imper-

ium, if not by conquest then through the cultivation of an extensive

sphere of inXuence east of the Rhine, based on client kings.220 Such

thinking is undermined by Ho

¨

ckmann’s analysis of the ‘La

¨

nden’. He

points out that the idea of a tactical role is not supported by the size

and design of these buildings. Both beaching and accommodation

areas are too small to have taken substantial attacking forces; and the

latter appear unsuitable as permanent quarters for naval crews. And,

anyway, there are no external gates from which troops might be

deployed against an enemy. It appears that, rather than the towers

defending the beaching areas, the beaching areas were there to secure

the towers, that is to give shelter to ships supplying their small

garrisons.221 In short, the right-bank installations were just defended

215 Asche (1983: 50–8, 64–5).

216 Symmachus, Orat. 2.2, 12–13, 18–19.

217 Julian, Ep. ad Ath. 280C; cf. Eutropius 10.14.2.

218 Historia Augusta, Tyranni Triginta 5.4; V. Probi 13.7–8. Cf. above 160.

219 Lander (1984: 284, quotation); Pabst (1989: 332).

220 Pabst (1989: 306). For still more bullish interpretations see Lorenz, S. (1997:

134–5).

221 Ho

¨

ckmann (1986: 400).

300 ConXict 365–94

observation posts, maintained from outside. The system was based on

naval control of the Rhine, but the naval bases proper were the left-

bank forts.

So what was Valentinian’s strategy? The creation of a new province

of ‘Alamannia’ was, as a statement of fact or as an aspiration, Wction.

Panegyrists and emperors were no fools. Both would have been aware

that old-fashioned annexation was impossible, no matter how deli-

cious were the lies that the former expressed and the latter graciously

accepted. The practical alternative was the maintenance of cooper-

ation with compliant border communities. The residual Roman pres-

ence over the Rhine may have been reduced by the unrest which

followed the rebellion of Magnentius and Julian’s campaigns of dom-

ination. On the other hand, Valentinian’s visit to the Danube source,

the continuing circulation of imperial bronze coins, and literary and

archaeological evidence for Romano-Alamannic collaboration sug-

gest that the Empire had no intention of turning its back on the

Rhine–Danube re-entrant. In this respect, at least, Alamannia Romana

was a reality. Therefore what was Valentinian about when he con-

structed a string of military sites over the Rhine? It appears that his

plan was, while marking Rome’s continued claim to territory over the

river, to use naval power to seal the Rhine against local hotheads and

long-distance intruders, Elbe-Germani and Burgundians alike: in

short, internal security.222 Roman forces would be alerted to danger

by the transrhenish outposts and the river patrols. If the enemy

attempted a crossing, the number and sophistication of Roman war-

ships would make short work of the primitive vessels available to the

barbarians (as was to happen to Goths on the Danube in 386).223

How eVective were Valentinian’s measures? Probably, not very.

War Xeets are notoriously diYcult to maintain and crew. More

particularly, Valentinian’s naval bases and towers must have been

vulnerable to the vagaries of the old Rhine: to being damaged by its

Xoodwaters, or being left high and dry by the shifting of its main

channel.224 Prolonged periods of drought or freezing would also have

222 Cf. Asche (1983: 88, 94–5, 99); Scho

¨

nberger (1969: 185–6); Lorenz, S. (1997:

133–5), with Symmachus, Orat. 2.13.

223 Zosimus 4.35.1, 38–9; Claudian, De Quarto Cos. Hon. 623–33, from

Ho

¨

ckmann (1986: 389 and n.47, 395).

224 Ho

¨

ckmann (1986: 369, 385–90); cf. above 282.

ConXict 365–94 301

made them vulnerable: in the case of the beaching areas, inaccessible

to lusoriae but accessible to anyone able to walk around their pro-

tecting wings. There was peace in the late fourth century, but this was

probably because the Alamanni, generally tractable, were for the

most part left undisturbed, and because there was a falling away in

long-distance raiding.225

The Alamanni were there to be exploited as the emperor saw Wt: as

the recipients of imperial clemency or as the victims of imperial

intolerance.226 The occasional goading of neighbouring Alamannic

communities into revolt was probably useful in maintaining the

illusion that they constituted a major enemy, requiring the perman-

ent presence of a large (and growing) army and a senior emperor and

his court, and justifying the resources that were needed to support

these. Valentinian may even have claimed that his system of defence

saved the Empire men and mate

´

riel.227 This brings us to the eVect of

Valentinian’s right-bank forts on Alamanni.

The Alamanni must have resented the new restraints. They were a

continuation of the exploitation by Julian, but on a greater scale: a

painful sign of Alamannic subservience; a slight on the honour of

precisely those communities which were, geographically and cultur-

ally, closest to Rome.228 To add insult to injury, Symmachus’ account

of the building of the Mannheim-Neckarau base suggests that the

construction, and perhaps the maintenance, of the ‘SchiVsla

¨

nden’

may have been a routine charge on adjacent Alamannic communi-

ties. And to add further insult to injury, given the dangers of dealing

with the old Rhine in w inter, and Julian’s odd 10-month-long

agreement with Alamanni around the former munimentum Traiani,

it may have been that riverside Roman bases were left unoccupied for

part of the year, with local Alamanni under strict instructions not to

interfere with them.229 What is certain is that the erection of these

structures caused the Romans to require local Alamanni to give

225 Below 317.

226 Clemency: Pabst (1989: 343–5); intolerance: AM 28.2.5–8.

227 Expansion of the army etc.: Nagl. (1948.: 2192); Lorenz, S. (1997: 104).

JustiWcation: Drinkwater (1996: 26–8), (1999a: 133); Heather (2001: 54, 60).

228 Cf. Asche (1983: 102).

229 Above 242.

302 ConXict 365–94

hostages for their good behaviour, a deeply unpopular and unsettling

stipulation.230

On the other hand, though by nature choleric, Valentinian was

no fool. He would not have thoughtlessly driven neighbouring

Alamannic communities into hostility to Rome. There were break-

downs in communication, causing serious incidents, as happened at

Mons Piri,231 but Valentinian’s ‘attack’ on the Alamannic settlement

suggests close cooperation with Alamannic rulers; and even the

trouble at Mons Piri may have been due as much to Alamannic

shock at a collapse in normally good relations as to Roman aggression.

Under Valentinian, leading Alamanni continued to hold high

positions in Roman service, albeit at not quite so exalted a level as

previously.232 The most dramatic evidence for a positive relationship

between the Empire and local Alamannic chiefs is to be found in the

massive hill-site of the Za

¨

hringer Burgberg.233

The picture that emerges from a study of Valentinian’s campaign-

ing and building is somewhat mixed. There was peace, though

this was due more to traditional Alamannic compliance than to

the emperor’s militar y genius. The relationship between leading

Alamanni and Rome was still positive, though less secure than

under Constantius II. In this respect, the initial change had come

about through Julian.234 Valentinian followed in Julian’s footsteps,

and under him Romano-Alamannic relations became more calculat-

ing.235 This led to a number of misunderstandings, chief among

which was Valentinian’s vendetta against Macrianus.

Ammianus’ account of events on the Rhine is now dominated by

Valentinian’s confrontation with Macrianus. He mentions two other

conXicts with Alamanni, in Raetia and before the building of the fort

at Robur; and Valentinian involved himself with matters not found in

Ammianus’ narrative, such as his visit to the Danube source. The

question is therefore whether Macrianus really was Valentinian’s

230 Above 282–3, 293.

231 Above 293.

232 Above 159.

233 Above 101–3.

234 Above 264–5.

235 Cf. Lorenz, S. (1997: 136).

ConXict 365–94 303

major concern during this period. Ammianus’ account of the later

part of Valentinian’s reign is selective. Though he praised the

emperor’s military building, he was not fond of him as a ruler.236

He may have chosen to concentrate on Valentinian’s dealings with

Macrianus to show how anger can lead to errors of judgement. A

case may, indeed, be made for the two other clashes with Alamanni

being more signi Wcant than Ammianus suggests. Though count

Theodosius’ incursion into Alamannic Raetia may have been

opportunistic, a turning to advantage of recent Burgundian penetra-

tion down the Main, this was an area that was to produce trouble

under Gratian.237 The same area, or, at least, its western portion, may

have been the target of Valentinian’s campaign before Robur, possibly

launched from the High Rhine,238 and, despite its cursory treatment

by Ammianus, probably more than just a raid. Were the Lentienses

proving diYcult before 378, a circumstance which Ammianus chose

to ignore in giving attention to Macrianus? Against this, justifying

Ammianus’ concentration on Macrianus, is the history of Romano-

Alamannic relations since the later third century, the strategic sig-

niWcance of the Main corridor and the ambiguous position of the

Burgundians as imperial allies. This is not just the story of a barbar-

ian troublemaker and a choleric emperor. Macrianus emerges as a

major historical Wgure: the greatest Alamannic leader we know.

From 359 Macrianus began to create a mini-empire down the Main,

with the blessing of Julian and then, presumably, to begin with,

Valentinian.239 Crucial to the understanding of initial Roman toler-

ance and of later developments is that Macrianus was steadfast in his

loyalty to Rome. He had supplied a regiment to Valentinian in the

period 365–8; and he is unlikely to have been responsible for Rando’s

raid of 368.240 There is no clear sign of his ever directly attacking the

Empire. The complaints against him by Valentinian’s counsellors in

236 His list of Valentinian’s vices is considerably longer than that of his virtues:

30.8–9.

237 Below 310–11. Gutmann (1991: 35) makes Theodosius’ campaign part of that

against Macrianus, but the distance between the two areas concerned is surely too

great for this.

238 Lorenz, S. (1997: 158).

239 Above 174, 250. Cf. Gutmann (1991: 34).

240 Above 170, 286.

304 ConXict 365–94

374241 are suspiciously alarmist. Given Alamannic numbers and tech-

nology, regular attacks on fortiWed cities are implausible, more likely

to reXect distorted and prejudiced recollection of what Mainz had

suVered at the hands of Rando than any actions by Macrianus, guilty

by association. Once his quarrel with Valentinian was patched up he

stayed a loyal ally. How, therefore, can we explain the breakdown in the

relationship between Valentinian and Macrianus? I propose that

trouble began with Rando’s raid, which exposed the vulnerability of

Mainz and allowed Macrianus to extend his inXuence close to the

Rhine in an area that was still ver y much Roman.242 It was this, raising

the spectre of barbarian ‘threat’, not any sort of direct incursions, that

was seen as arrogant and that amounted to the ‘restless disturbances’

that ‘confused the Roman state’.243

Valentinian’s assessment of the ‘danger’ is discernible in the

strength of his reaction to it. He was present in person at Wiesbaden

early in June 369, prior to leading the manoeuvres at Alta Ripa.244

(There is no reason to suppose that his visit to the right bank at this

time was conWned to Kastel.245) Here he probably ordered the con-

struction of the ‘Heidenmauer’, a massive defence work, begun but

never completed.246 A date of 369 is likely for this enigmatic structure

given the general pattern of Valentinian’s military building.247 It was,

perhaps, in response to Rando’s raid and its repercussions.248 More

dramatic, however, was Valentinian’s calling on Burgundian support.

The Burgundian alliance was not new.249 Valentinian’s links with

these people must have been forged in 369 or earlier: Symmachus,

in ‘looking forward’ to a Burgundian alliance early in 370, will have

known that cooperation against Macrianus was already planned.250

241 AM 30.3.3. Above 284–5.

242 Above 286–7.

243 AM 28.5.8: Macriani regis . . . fastus, sine Wne vel modo rem Romanam irrequietis

motibus confundentis. Above 283.

244 CT 10.19.6. Seeck (1919: 236): 4 June 369.

245 i.e. contra Lorenz, S. (1997: 118).

246 Schoppa (1974: 95–7); Scho

¨

nberger (1969: 185).

247 Above 295.

248 Contra Lorenz, S. (1997: 141): after 371.

249 Above 110, 190.

250 Symmachus, Orat. 2.13. Lorenz, S. (1997: 146). Cf. Wood (1990: 58) on the

possibility that by the time of Valentinian, Roman—including Catholic Christian—

inXuence on Burgundians was greater than is usually thought.

ConXict 365–94 305

What was new was the direct summoning of Burgundians to attack a

Roman ally.

In 370 the Burgundians exceeded their instructions. Supposed to

press Macrianus from the east while Valentinian struck from the west,

they attacked prematurely and came straight down the Main, appar-

ently meeting little resistance and causing enormous concern.251 They

gave an unwelcome demonstration of the vulnerability of Mainz and

its region to people other than Macrianus and his Bucinobantes.

Their request for Roman help could be interpreted as a request for

aid to break the local Alamanni. Thus, instead of protecting the

Main corridor, they now posed a threat to its security: one that

Rome, still in a commanding position, could easily handle, but one

that complicated frontier diplomacy. It comes as no surprise that

Valentinian apparently ceased to involve himself with Burgundians.

His sole desire was to re-establish the status quo, which returns us to

Macrianus.

Valentinian’s alternative strategy was not to break the Bucinobantes

but, having arrested Macrianus, to put them under a less redoubtable

ruler. This involved the customary Roman employment of deceit

in dealings with barbarians—as demonstrated, as Ammianus says,

by Julian, ever Valentinian’s model, in his treatment of Vadomarius.

Valentinian’s device was the snatch raid, launched in 371. This is

an illuminating episode. In order to understand it, we need to

decide precisely what happened. Key issues here are the location

of Valentinian’s pontoon bridge and the destination of the Roman

force.

As far as the bridge is concerned, one’s immediate thought is that it

must have been somewhere upstream from the permanent crossing

at Mainz/Kastel, since anywhere downstream would have landed

Valentinian’s troops south of the Main conXuence. A crossing into

the region of modern Biebrich (with its ‘SchiVsla

¨

nde’252) would have

brought the army very close to Wiesbaden. But this raises questions

as to why, since speed was so important, Valentinian did not use the

251 Above 283; cf. Lorenz, S. (1997: 147). Among the prisoners executed by the

Burgundians may well have been Roman citizens ordinarily resident on the right

bank and not just, say, Rando’s captives of 369. Cf. Lorenz, S. (1997: 148 n.532).

252 Above 295.

306 ConXict 365–94

Mainz bridge itself, and how, despite the Romans’ best endeavours, a

major military undertaking anywhere along the Upper Rhine could

have been kept secret from Macrianus. I suggest that Mainz was not

chosen because unusual activity here would indicate an imminent

expedition. Forces concentrated opposite, say, Biebrich mig ht, how-

ever, be passed oV as participating in manoeuvres, of the sort prac-

tised at Alta Ripa in 369. In describing the progress of Severus’

vanguard, Ammianus uses the phrase contra Mattiacas Aquas. Rolfe

translates contra straightforwardly as ‘against’, but Ammianus uses

this word in such a way only when describing conXicts against

persons or people. When he employs it to specify a location—

topographical, geographical or even astronomical—he always

means ‘over against’, ‘opposite’ or ‘facing’, very often implying ‘in

full view of ’.253 Thus, Severus was to proceed through Wiesbaden,

northwards into an area that looked towards the Taunus range, along

the military highway that led from Mainz via Wiesbaden to the old

limes fort at Zugmantel, the road along which Macrianus was able to

Xee to safety254 (Fig. 4).

This must be where Severus encountered and killed, as a security

risk, Ammianus’ scurrae—probably Germanic mercenaries, taking

war captives to market at Wiesbaden.255 Macrianus’ residence lay

along this road, not in Wiesbaden itself. Macrianus’ proximity to

what was still a Roman settlement256 will have resulted mainly from

his move down the Main after the Rando incident. However, the fact

that Macrianus’ attendants had to get him away in a covered carriage

suggests that he was indisposed, and so may have come close to

Wiesbaden to use its healing springs. This could have been what

Valentinian discovered from Alamannic deserters which persuaded

him that Macrianus was expecting no trouble and would not resist

253 AM 18.2.16; 22.8.4; 23.6.10, 53; 29.4.7; 30.3.5; 31.15.12. Cf. 19.5.6–6.6; 20.3.11,

11.26; 21.15.2; 22.8.20; 23.6.64.

254 Lorenz, S. (1997: 153).

255 AM 29.4.4. Above 135. Scurra is diYcult to translate: see Sabbah (1999: 187 at

n.107). In this context I interpret it as meaning Germanic warriors with some sort of

aYliation to the Roman army, i.e. not ‘hostiles’, engaged in disposing of boot y won

through raiding other Germanic communities (perhaps Frankish).

256 Above 305.

ConXict 365–94 307