Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913), Child of the Big

City (1914), Silent Witnesses (1914), Children of the

Age (1915), The Dying Swan (1916), and To Happi-

ness (1917)—provide a vivid picture of a lost Rus-

sia.

The revolutionary year 1917 brought joy and

misgiving to filmmakers. Political, economic, and

social instability shuttered most theaters by the be-

ginning of 1918. Studios began packing up and

moving south to Yalta, to escape Bolshevik control.

By 1920, Russia’s filmmakers were on the move

again, to Paris, Berlin, and Prague. Russia’s great

actor Ivan Mozzhukhin (1890–1939, known in

France as “Mosjoukine”) was one of few who en-

joyed as much success abroad as at home.

SOVIET SILENT CINEMA, 1918–1932

The first revolutionary film committees formed in

1918, and on August 27, 1919, the Bolshevik gov-

ernment nationalized the film industry, placing it

under the control of Narkompros, the People’s

Commissariat for Enlightenment. Nationalization

represented wishful thinking at best, since

Moscow’s movie companies had already decamped,

dismantling everything that could be carried.

Filmmaking during the Civil War of 1917–1922

took place under extraordinarily difficult condi-

tions. Lenin was acutely aware of the importance

of disseminating the Bolshevik message to a largely

illiterate audience as quickly as possible, yet film

stock and trained cameramen were in short supply—

not to mention projectors and projectionists. Apart

from newsreels, the early Bolshevik repertory con-

sisted of “agit-films,” short, schematic, but excit-

ing political messages. Films were brought to

the provinces on colorfully decorated agit-trains,

which carried an electrical generator to enable the

agitki to be projected on a sheet. Innovations like

these enabled Soviet cinema to rise from the ashes

of the former Russian film industry, leading even-

tually to the formation of Goskino, the state film

trust, in 1922 (reorganized as Sovkino in 1924).

Since most established directors, producers, and

actors had already fled central Russia for territories

controlled by the White armies, young men and

women found themselves rapidly rising to posi-

tions of prominence in the revolutionary cinema.

They were drawn to film as “the art of the future.”

Many of them had some experience in theater pro-

duction, but Lev Kuleshov (1899–1970), who had

begun his cinematic career with the great prerevo-

lutionary director Bauer, led the way, though he

was still a teenager.

By the end of the civil war, most of Soviet Rus-

sia’s future filmmakers had converged on Moscow.

Many of them (Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein, and

their “collectives”) were connected to

the Proletkult theater, where they debated and

dreamed.

Because film stock was carefully rationed un-

til the economy recovered in 1924, young would-

be directors had to content themselves with

rehearsing the experiments they hoped to film and

writing combative theoretical essays for the new

film journals. The leading director-theorists were

Kuleshov, Eisenstein (1898–1948), Vsevolod Pu-

dovkin (1893–1953), Dziga Vertov (1896–1954,

born Denis Kaufman), and the “FEKS” team of Grig-

ory Kozintsev (1905–1973) and Leonid Trauberg

(1902–1990). Kuleshov wrote most clearly about

the art of the cinema as a revolutionary agent, but

Eisenstein’s and Vertov’s theories (and movies) had

MOTION PICTURES

973

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

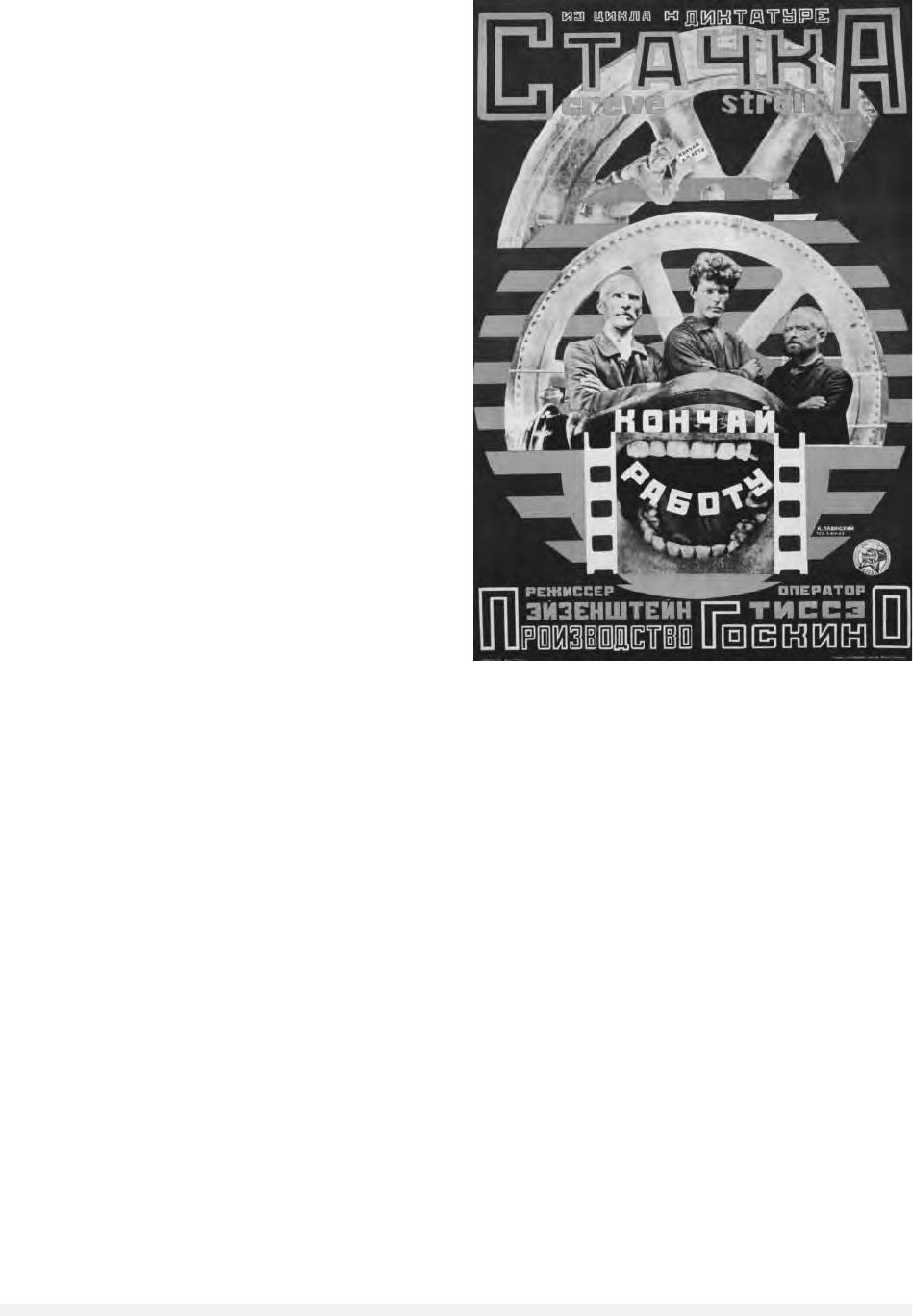

Poster advertising the 1925 Soviet film

Strike.

© S

WIM

I

NK

/

CORBIS

an impact that extended far beyond the Soviet

Union’s borders.

The debates between Eisenstein and Vertov

symbolized the most extreme positions in the the-

oretical conflicts among the revolutionary avant-

garde of the 1920s. Eisenstein believed in acted

cinema but borrowed Kuleshov’s idea of the

actor as a type; he preferred working with non-

professionals. Vertov privileged non-acted cinema

and argued that the movie camera was a “cinema

eye” (kino-glaz) that would catch “life off-guard”

(zhizn vrasplokh)—yet he was an inveterate ma-

nipulator of time and space in his pictures. Eisen-

stein believed in a propulsive narrative driven by a

“montage of attractions,” with the masses as the

protagonists, whereas Vertov was decisively anti-

narrative, believing that a brilliantly edited kalei-

doscope of images best revealed the contours of

revolutionary life.

Eisenstein’s first two feature films, Strike (1925)

and Battleship Potemkin (1926), enjoyed enormous

success with critics and politicians but were much

less popular with the workers and soldiers whose

interests they were supposed to service. The same

was true of Vertov’s pictures. The intelligentsia

loved Forward, Soviet! and One-Sixth of the World

(both 1926), but proletarians were nonplussed.

Kuleshov, Pudovkin, Kozintsev, and Trauberg

(who directed as a team) were more successful

translating revolutionary style and content for

mass audiences because they retained plot and char-

acter at the heart of their films. The Extraordinary

Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks

(1924), one of Kuleshov’s earliest efforts, appeared

as a favorite film in audience surveys through the

end of the 1920s. The same was true of Pudovkin’s

Mother (1926), a loose adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s

famous novel. Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Over-

coat (1926) is a good example of the extremes to

which young directors pushed the classical narra-

tive.

Despite this wealth of talent, Soviet avant-

garde films never came close to challenging the

popularity of American movies in the 1920s. Dou-

glas Fairbanks’s and Charlie Chaplin’s pictures

drew sell-out audiences. In response to the pres-

sures to make Soviet entertainment films—and the

need to show a profit—Goskino and the quasi-pri-

vate studio Mezhrapbom invested more heavily in

popular films than in the avant-garde, to the great

dismay of the latter, but to the joy of audiences.

The leading popular filmmaker was Protazanov,

who returned to Soviet Russia in 1923 to make a

string of hits, starting with the science fiction ad-

venture, Aelita (1924).

Also very successful with the spectators were

the narrative films of younger directors such as

Fridrikh Ermler (1898–1967, born Vladimir

Breslav), Boris Barnet (1902–1965), and Abram

Room (1894–1976). Ermler earned fame for his

trenchant social melodramas (Katka’s Reinette Ap-

ples, 1926 and The Parisan Cobbler, 1928). Barnet’s

intelligent comedies such as The Girl with the

Hatbox (1927) sparkled, as did his adventure serial

Miss Mend (1926),. Room was perhaps the most

versatile of the three, ranging from a revolutionary

adventure, Death Bay (1926), to a remarkable melo-

drama about a ménage à trois, Third Meshchanskaya

Street (1927, known in the West as Bed and Sofa).

It must be emphasized that moviemaking was

not a solely Russian enterprise, although distribu-

tion politics often made it difficult for films from

Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia to be considered

more than exotica. The greatest artist to emerge

from the non-Russian cinemas was certainly

Ukraine’s Alexander Dovzhenko (1894–1956), but

Armenia’s Amo Bek-Nazarov (1892–1965) and

Georgia’s Nikolai Shengelaya (1903–1943) made

important contributions to early Soviet cinema

as well.

In 1927, as the New Economic Policy era was

coming to a close, Soviet cinema was flourishing.

Cinema had returned to all provincial cities and

rural areas were served by cinematic road shows.

There was a lively film press that reflected a vari-

ety of aesthetic positions. Production was more than

respectable, about 140 to 150 titles annually. Six

years later, production had plummeted to a mere

thirty-five films.

Many factors contributed to the crisis in cin-

ema that was part of the Cultural Revolution. First,

in 1927, sound was introduced to cinema, an event

with significant artistic and economic implications.

Second, proletarianist organizations such as RAPP,

the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers, and

ARRK, the Association of Workers in Revolutionary

Cinematography were infiltrated by extremist ele-

ments who supported the government’s aims to

turn the film industry into a tool for propagandiz-

ing the collectivization and industrialization cam-

paigns. This became apparent at the first All-Union

Party Conference on Cinema Affairs in 1928. Third,

in 1929, Anatoly Lunacharsky, the leading propo-

nent of a diverse cinema, was ousted as commissar

MOTION PICTURES

974

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of enlightenment, and massive purges of the film

industry began that lasted through 1931.

These troubled times saw the production of

four great films, the last gasp of Soviet silent cin-

ema: Ermler’s The Fragment of the Empire, Kozint-

sev and Trauberg’s New Babylon, Vertov’s The Man

with the Movie Camera (all 1929), and the follow-

ing year, Dovzhenko’s Earth.

STALINIST CINEMA, 1932–1953

By the end of the Cultural Revolution, it was clear

to filmmakers that the era of artistic innovation

had ended. Movies and their makers were now “in

the service of the state.” Although Socialist Realism

was not formally established as aesthetic dogma

until 1934, (reconfirmed in 1935 at the All-Union

Creative Conference on Cinematographic Affairs),

politically astute directors had for several years

been making movies that were only slightly more

sophisticated than the agit-films of the civil war.

In the early 1930s, a few of the great artists of

the previous decade attempted to adapt their ex-

perimental talents to the sound film. These efforts

were either excoriated (Kuleshov’s The Great Con-

soler and Pudovkin’s The Deserter, both 1933) or

banned outright (Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow,

1937). Film production plummeted, as directors

tried to navigate the ever-changing Party line, and

many projects were aborted mid-production.

Stalin’s intense personal interest and involvement

in moviemaking greatly exacerbated tensions.

Some of the early cinema elite avant-garde were

eventually able to rebuild their careers. Kozintsev

and Trauberg scored a major success with their

popular adventure trilogy: The Youth of Maxim

(1935), The Return of Maxim (1937), The Vyborg Side

(1939). Pudovkin avoided political confrontations

by turning to historical films celebrating Russian

heroes of old in Minin and Pozharsky (1939), fol-

lowed by Suvorov in 1941. Eisenstein likewise found

a safe historical subject in the only undisputed mas-

terpiece of the decade, Alexander Nevsky (1938).

Others, such as Dovzhenko and Ermler, seriously

compromised their artistic reputations by making

movies that openly curried Stalin’s favor. Ermler’s

The Great Citizen (two parts, 1937–1939) is a par-

ticularly notorious example.

New directors, most of them not particularly

talented, moved to the forefront. Novices such as

Nikolai Ekk and the Vasiliev Brothers made two of

the enduring classics of Socialist Realism: The Road

to Life (1931) and Chapayev (1934). Another rela-

tive newcomer, Ivan Pyrev, churned out Stalin-

pleasing conspiracy films such as The Party Card

(1936), about a woman who discovers her hus-

band is a traitor, before turning to canned social-

ist comedies, of which Tractor Drivers (1939) is the

most typical.

Some of the new generation managed to main-

tain artistic standards. Mikhail Romm’s revisionist

histories of the revolution, Lenin in October (1937)

and Lenin in 1918 (1939), which placed Stalin right

at Lenin’s side, were the first major hits in his dis-

tinguished career. Mark Donskoy’s three-picture

adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s autobiography, be-

ginning with Gorky’s Youth (1938) also generated

popular acclaim. The most beloved of the major

directors of the 1930s was, however, Grigory

Alexandrov. Alexandrov, who had worked as Eisen-

stein’s assistant until 1932, successfully distanced

himself from the maverick director, launching a se-

ries of zany musical comedies starring his wife,

Lyubov Orlova, in 1934 with The Jolly Fellows.

When the German armies invaded the Soviet

Union in June 1941, the tightly controlled film in-

dustry easily mobilized for the wartime effort.

Considered central to the war effort, key filmmak-

ers were evacuated to Kazakhstan, where makeshift

studios were quickly constructed in Alma-Ata.

With very few exceptions—Eisenstein’s Ivan the

Terrible (1944–1946) being most noteworthy—

moviemaking during the war years focused almost

exclusively on the war. Newsreels naturally dom-

inated production. The fiction films that were made

about the war effort were quite remarkable com-

pared to those of the other combatant nations in

that they focused on the active role women played

in the partisan movement. One of these, Ermler’s

She Defends Her Motherland (1943), which tells the

story of a woman who puts aside grief for

vengeance, was shown in the United States during

the war as No Greater Love.

The postwar years, until Stalin’s death in 1953,

were a cultural wasteland. Film production nearly

ground to a halt; only nine films were made in

1950. The wave of denunciations and arrests

known as the anti-cosmopolitan campaign roiled

the cultural intelligentsia, particularly those who

were Jewish such as Vertov, Trauberg, and Eisen-

stein. Eisenstein’s precarious health was aggravated

by the extreme tensions of the time and the disfa-

vor that greeted the second part of Ivan the Terrible.

He became the most famous casualty among film-

makers, dying of a heart attack in 1948 at the age

of only fifty. Cold War conspiracy melodramas

MOTION PICTURES

975

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

dominated movie theaters (not unlike McCarthy era

films in the United States a few years later), along

with ever more extravagant panegyrics to Stalin.

Georgian director Mikhail Chiaureli’s first ode to

Stalin, The Vow (1946), was followed by The Fall of

Berlin (1949), which Richard Taylor has aptly

dubbed “the apotheosis of Stalin’s cult of Stalin.”

SOVIET CINEMA FROM THE THAW

THROUGH STAGNATION, 1953–1985

By the mid-1950s, filmmakers were confident that

the Thaw—as Khrushchev’s relaxation of censor-

ship was known-would last long enough for them

to express long-dormant creativity. The move from

public and political toward the private and personal

became a hallmark of the period. Thaw pictures

were appreciated not only at home, but also abroad,

where they received numerous prizes at interna-

tional film festivals. There was now a human face

to the Soviet colossus.

The greatest movies of the period rewrote the

history of World War II, the Great Patriotic War.

Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1958, signaling

that Soviet cinema was once again on the world

stage after nearly thirty years. Cranes is the story

of a woman who betrays her lover, a soldier who

is killed at the front, to marry his cousin, a craven

opportunist. There is no upbeat ending, no neat res-

olution. The same can be said of Sergei Bon-

darchuk’s The Fate of a Man and Grigory Chukhrai’s

The Ballad of a Soldier (both 1959). In the former,

a POW returns home to find his entire family dead;

in the latter, a very young soldier’s last leave home

to help his mother is movingly recorded.

A film that is often considered the last impor-

tant movie of the Thaw also launched the career of

the greatest film artist to emerge in postwar Soviet

cinema. This was Ivan’s Childhood (1962, known

in the United States as My Name Is Ivan), a stun-

MOTION PICTURES

976

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Movie still of a battle scene from Sergei Eisenstein’s classic

Alexander Nevsky

(1938)

.

© B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

ning antiwar film that won the Golden Lion at the

Venice Film Festival. The director was Andrei

Tarkovsky (1932–1986). By the time Tarkovsky

began work on Andrei Rublev in the mid-1960s,

Khrushchev had been ousted, and Leonid Brezh-

nev’s era of stagnation had begun. Cultural icon-

oclasm was no longer tolerated, and Tarkovsky’s

dystopian epic about medieval Russia’s greatest

painter was not released in the USSR until 1971,

although it won the International Film Critics’ prize

at Cannes in 1969. Tarkovsky toiled defiantly in

the 1970s to produce three more Soviet films, So-

laris (1972), The Mirror (1975), and Stalker (1980).

He emigrated to Europe in 1984 and died of can-

cer two years later.

Filmmaking under Brezhnev was generally un-

remarkable, although two films, Bondarchuk’s

War and Peace (1966) and Vladimir Menshov’s

Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1979) each won

the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. The most interest-

ing movies (such as Alexander Askoldov’s The Com-

missar, 1967) were shelved, not to be released until

the late 1980s as part of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glas-

nost. Among the exceptions to the mundane fare

were Larisa Shepitko’s tale of World War II collab-

oration, The Ascent (1976), and Lana Gogoberidze’s

Several Interviews on Personal Questions (1979),

which sensitively explored the drab, difficult lives

of Soviet women.

The best-known director to have started his ca-

reer during the Brezhnev era is Nikita Mikhalkov

(b. 1945). Son of Sergei Mikhalkov, a Stalinist

writer of children’s stories, the younger Mikhalkov

first made a name for himself as an actor. Mik-

halkov achieved his greatest successes in the 1970s

and 1980s with his “heritage” films, elegiac recre-

ations of Russian life in the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries, often adapted from literary

classics, among them An Unfinished Piece for Player

Piano (1977), Oblomov (1979), and Dark Eyes

(1983).

RUSSIAN CINEMA IN

TRANSITION, 1985–2000

When Gorbachev announced the advent of pere-

stroika and glasnost in 1986, the Union of Cine-

matographers stood at the ready. After a sweeping

purge of the union’s aging and conservative bu-

reaucracy, the maverick director Elem Klimov (b.

1933) took the helm. Although Klimov had made

a number of movies under Brezhnev, he did not

emerge as a major director until 1985, with the re-

lease of his stunning antiwar film Come and See.

Under Klimov’s direction, the union began releas-

ing the banned movies of the preceding twenty

years, in effect rewriting the history of late Soviet

cinema.

The film that most captured the public’s imag-

ination in that tumultuous period was Georgian,

not Russian. Tengiz Abuladze’s Repentance (1984,

released nationally in 1986) is a surrealistic black

comedy-drama that follows the misdeeds of the Ab-

uladze family, provided a scathing commentary on

Stalinism. Although a difficult film designed to

provoke rather than entertain, Repentance packed

movie theaters and sparked a national debate about

the legacy of the past and the complicity of the sur-

vivors.

Television also became a major venue for film-

makers. Gorbachev’s cultural policies encouraged

publicistic documentaries that exposed either the

evils of Stalin and his henchmen or the decay and

degradation of contemporary Soviet life. Fiction

films such as Little Vera (Vasily Pichul, 1988), In-

tergirl (Pyotr Todorovsky, 1989), and Taxi Blues

(Pavel Lungin, 1990) followed suit by telling seamy

tales about the Soviet underclass.

The movie industry began to fragment even be-

fore the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Union

of Cinematographers decentralized in mid-1990,

and Goskino and Sovexportfilm, which provided

central oversight over film production and distrib-

ution, had completely lost control by the end of

1990. The early 1990s saw the collapse of native

film production in all the post-Soviet states. Cen-

tralization and censorship had long been the bane

of the industry, but filmmakers had no idea how

to raise money for their projects—and were even

more baffled by being expected to turn a profit.

Market demands became known as “commercial

censorship.” Filmmakers also had to contend for

the first time with competition from Hollywood,

as second-rate American films flooded the market.

The Russian cinema industry began to rebound

in the late 1990s. It now resembled other European

cinemas quite closely, meaning that national pro-

duction was carefully circumscribed, focusing on the

art film market. Nikita Mikhalkov emerged the clear

winner. By the turn of the century he became the

president of the Russian Filmmakers’ Union, the

president of the Russian Cultural Foundation, and

the president of the only commercially successful

Russian studio, TriTe. He established a fruitful part-

nership with the French company Camera One,

MOTION PICTURES

977

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

which coproduced his movies and distributed them

abroad. He took enormous pride in the fact that

Burnt by the Sun, his 1995 exploration of the begin-

nings of the Great Terror, won the Oscar for Best

Foreign Picture that year, only the third Russian-

language film to have done so, and certainly the best.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century,

therefore, it seems that the glory days of Russian

cinema are past. This past, however, has earned

Russian and Soviet films and filmmakers an en-

during place in the history of global cinema.

See also: AGITPROP; ALEXANDROV, GRIGORY ALEXAN-

DROVICH; BAUER, YEVGENY FRANTSEVICH; CHA-

PAYEV, VASILY IVANOVICH; CULTURAL REVOLUTION;

EISENSTEIN, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH; MIKHALKOV,

NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; ORLOVA, LYUBOV PETROVNA;

SOCIALIST REALISM; TARKOVSKY, ANDREI ARSE-

NIEVICH; THAW, THE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Horton, Andrew, and Brashinsky, Mikhail. (1992). The

Zero Hour: Glasnost and Soviet Cinema in Transition.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kenez, Peter. (2001). Cinema and Soviet Society from the

Revolution to the Death of Stalin. London: I. B. Tau-

ris.

Lawton, Anna. (1992). Kinoglasnost: Soviet Cinema in Our

Time. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leyda, Jay. (1960). Kino: A History of the Russian and So-

viet Film. London: Allen & Unwin.

Taylor, Richard. (1979). The Politics of the Soviet Cinema,

1917–1929. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Taylor, Richard. (1998). Film Propaganda: Soviet Russia

and Nazi Germany, 2nd rev. ed. London: I. B. Tauris.

Taylor, Richard, and Christie, Ian, eds. (1988). The Film

Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents,

1896–1939. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Tsivian, Yuri, comp. (1989). Silent Witnesses: Russian

Films, 1908–1919. Pordenone and London, 1989.

Tsivian, Yuri. (1994). Early Cinema in Russia and Its Cul-

tural Reception. Friuli-Venezia: Edizioni Biblioteca

dell’immagine; London: British Film Institute.

Woll, Josephine. (2000). Real Images: Soviet Cinema and

the Thaw. London: I. B. Tauris.

Youngblood, Denise J. (1991). Soviet Cinema in the Silent

Era, 1918-1935. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Youngblood, Denise J. (1992). Movies for the Masses: Pop-

ular Cinema and Soviet Society in the 1920s. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Youngblood, Denise J. (1999). The Magic Mirror:

Moviemaking in Russia, 1908-1918. Madison: Uni-

versity of Wisconsin Press.

D

ENISE

J. Y

OUNGBLOOD

MOVEMENT FOR DEMOCRATIC REFORMS

On July 1, 1991, nine well-known close associates

of Mikhail Gorbachev, president of the USSR, and

Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Soviet Fed-

erated Socialist Republic (RSFSR), called for the es-

tablishment of a Movement for Democratic Reform

to unite all those who supported human rights and

a democratic future for the USSR. The appeal was

signed by Arkady Volsky, Gavril Popov, Alexander

Rutskoi, Anatoly Sobchak, Stanislav Shatalin, Ed-

uard Shevardnadze, Alexander Yakovlev, Ivan

Silayev, and Nikolai Petrakov. It endorsed the de-

velopment of a market economy and the mainte-

nance of the USSR in some form, and declared that

a founding Congress would be convened in Sep-

tember to decide whether or not to form a politi-

cal party.

Alexander Yakovlev explained that the move-

ment sought to overcome the Party apparat’s re-

sistance to the democratization of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and he openly

appealed to reformist Communists to join the

movement. President Gorbachev endorsed its for-

mation (many believed that it had been established

to provide him with an alternative political base in

the event of a formal split in the CPSU). The Cen-

tral Committee of the CPSU was skeptical of the

movement, and the Communists in the military

openly attacked it.

After the abortive coup against President Gor-

bachev in August 1991, the leaders of the move-

ment were named to important political posts

sought to fill the gap created by the dissolution of

the CPSU and openly recruited reformist leaders of

the Party as well as members of the “military in-

dustrial complex.”

The founding Congress of the movement was

finally convened in December 1991, just days af-

ter the collapse of the USSR and the formation of

the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

The Congress called for the formation of a broad

coalition of democratic movements and parties, en-

dorsed market reforms, sought the support of

emerging entrepreneurs, and supported the CIS

with some misgivings.

MOVEMENT FOR DEMOCRATIC REFORMS

978

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

In February 1992 the original movement was

replaced by the Russian Movement for Democratic

Reform (RMDR), and Gavril Popov was chosen as

its chairman. In June 1992 he resigned from his

position as mayor of Moscow to devote more time

to the development of the movement as a “demo-

cratic opposition” to the Yeltsin regime.

The RMDR became increasingly critical of the

Yeltsin regime’s economic policies in 1992 and

1993. It nominated a significant number of candi-

dates for the first elections to the state duma in De-

cember 1993. Although it endorsed much of the

new Constitution, it was sharply critical of the

growth of bureaucracy, the process of privatiza-

tion, and the continued power of the Communist

nomenklatura. It advocated sharp reduction of the

bureaucracy, the decentralization of economic

power, distribution of land to all citizens, local

controls over energy, and a clear demarcation of

authority between president, parliament, and gov-

ernment. It received almost 9 percent of the vote in

St. Petersburg, but failed to gain the 5 percent of

the vote needed for representation in the state

duma.

After the elections of December 1993 RMDR re-

peatedly assailed the entire reform model of the

Yeltsin regime and sought partners to establish an

effective democratic opposition. In September 1994

it formed an alliance with Democratic Russia, and

in 1995 it worked with other similar organizations

to create a Social Democratic Union (SDU) to con-

test the 1995 elections. After the SDU’s defeat in

the elections, the RMDR disappeared from public

view.

See also: AUSUST 1991 PUTSCH; POPOV, GAVRIL KHARITO-

NOVICH; RUTSKOI, ALEXANDER VLADIMIROVICH;

SHATALIN, STANISLAV SERGEYEVICH; SHEVARD-

NADZE, EDUARD AMVROSIEVICH; SOBCHAK, ANATOLY

ALEXANDROVICH; VOLSKY, ARKADY IVANOVICH;

YAKOVLEV, ALEXANDER NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Colton, Timothy J., and Hough, Jerry Hough, eds.

(1998). Growing Pains: Russian Democracy and the

Election of 1993. Washington, DC: Brookings Insti-

tution Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russia Democracy Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

J

ONATHAN

H

ARRIS

MOVEMENT IN SUPPORT OF THE ARMY

The movement, In Support of the Army, War In-

dustry, and War Science (DPA) was founded in July

1997 on the initiative and with the guidance of the

chair of the Duma defense committee, Lev Rokhlin,

a hero of the war in Chechnya. With the degrada-

tion of the army, it soon became a significant anti-

government force. After the murder of Rokhlin a

year later, his successor as chair of the committee,

Viktor Ilyukhin, became head of the party. Ilyukhin

was famous for having brought a legal action,

during his days as prosecutor, against Mikhail Gor-

bachev. Next in line to Ilyukhin was Colonel Gen-

eral Albert Mashakov, former commander of the

Privolga military district, candidate in the 1991

presidential elections, and notorious for his anti-

Semitic statements (he once suggested, for instance,

that the DPA should be unofficially called the DPZh,

or “Movement Against Jews”). Among the strate-

gies considered by the Left on the eve of the 1999

elections, the “three-columns” idea would have had

the DPA at the head of one column. Another strat-

egy called for the formation of a bloc of national-

patriotic forces consisting of the DPA, the Russian

Popular Movement, the Union of Compatriots “Fa-

therland,” and the Union of Christian Rebirth. The

second idea had the DPA join a united oppositional

bloc with the Communist Party of the Russian Fed-

eration (CPRF). A third proposal, the one adopted,

had the DPA enter the elections independently. The

first three places on the DPA list were taken by

Ilyukhin, Makashov, and Yuri Saveliev, rector of

the Petersburg Technical University, whose popu-

larity rested on his having fired a professor from

the United States because of the NATO bombing of

Yugoslavia. The DPA list disappeared, but Ilyukhin

and one other candidate were elected to the Duma.

In the early twenty-first century the DPA has

little influence and is essentially a satellite of the

Communist Party. Ilyukhin, its leader, is a mem-

ber of the Central Committee of the CPRF. He takes

entirely radical positions and plays a certain role in

the leadership of the National Patriotic Union of

Russia (NPSR).

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERA-

TION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

MOVEMENT IN SUPPORT OF THE ARMY

979

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergei. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

McFaul, Michael; Petrov, Nikolai; and Ryabov, Andrei,

eds. (1999). Primer on Russia’s 1999 Duma Elections.

Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Interna-

tional Peace.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. The Tragedy of Rus-

sia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democracy.

Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

MSTISLAV

(1076–1132), Vladimir Monomakh’s eldest son,

grand prince of Kiev, and the progenitor of the dy-

nasties of Vladimir in Volyn and of Smolensk.

In 1088 Mstislav Vladmirovich’s grandfather

Vsevolod appointed him to Novgorod, but in 1093

his father (Monomakh) sent him to Rostov and

Smolensk. In 1095 he returned to Novgorod where

he ruled for twenty years. In 1096 his father or-

dered him to campaign against Oleg Svyatoslavich

of Chernigov, who was pillaging his Suzdalian

lands. Mstislav’s most important victory was de-

feating Oleg and making him attend a congress of

princes in 1097 at Lyubech, where he was recon-

ciled with Monomakh and Svyatopolk of Kiev.

In 1117 Monomakh, now grand prince of Kiev,

summoned Mstislav to Belgorod where, it appears,

he made Mstislav coruler. He also designated

Mstislav his successor in keeping with his agree-

ment with the Kievans, who had promised to

accept Mstislav and his descendants as their hered-

itary dynasty. Monomakh therewith violated the

system of lateral succession allegedly introduced by

Yaroslav the Wise. When Monomakh died on May

19, 1125, Mstislav succeeded him. Two years later,

when Vsevolod Olgovich usurped Chernigov from

his uncle Yaroslav, Mstislav violated the lateral or-

der of succession again by confirming Vsevolod’s

usurpation and thus winning his loyalty. Whereas

Monomakh had driven the Polovtsy to the river

Don, in 1129 Mstislav drove them even beyond the

Volga. In 1130, in keeping with Monomakh’s pol-

icy of securing his family’s control over the other

princely families, Mstislav exiled the disloyal

princes of Polotsk to Constantinople and replaced

them with his own men. Thus, before he died, he

controlled, directly or through his brothers or his

sons, Kiev, Pereyaslavl, Smolensk, Rostov, Suzdal,

Novgorod, Polotsk, Turov, and Vladimir in Volyn.

Moreover, Vsevolod of Chernigov was his son-in-

law. Mstislav, called “the Great” by some, died on

April 15, 1132, and was buried in the Church of

St. Theodore, which he had built.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; NOVGOROD THE GREAT; ROTA SYS-

TEM; VLADIMIR MONOMAKH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1994). The Dynasty of Chernigov

1054–1146. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediae-

val Studies.

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

MURAVIEV, NIKITA

(1796–1843), army officer who conspired to over-

throw Nicholas I.

Nikita Muraviev was one of the army officers

involved in the Decembrist movement to overthrow

Tsar Nicholas I. He is best known for the consti-

tution he drafted for a new Russian state. Although

he did not actually participate in the uprising on

December 14, 1825, he was condemned to death

when it failed. His sentence was later commuted to

twenty years at hard labor in the Nerchinsk mines.

He died in Irkutsk Province.

In 1813, after studying at Moscow University,

Muraviev embarked on a military career, and in

1816 he joined with other aristocratic young offi-

cers in organizing a secret society called the Union

of Salvation. Led by Paul Pestel, it was renamed the

Union of Welfare a year later. Stimulated by the

French Revolution (1789) and the Napoleonic Wars

(1812–1815), the officers had been influenced by

the liberal ideas of French and German philosophers

while serving in Europe or attending European uni-

versities. The new Russian literature, with its moral

and social protest against Russia’s backwardness,

also was an important influence, especially the

works of Nikolai Novikov, Alexander Radishchev,

and the poets Alexander Pushkin and Alexander Gri-

boyedov. The Arzamas group, an informal literary

society founded around 1815, attracted several men

who later became Decembrists, including Nikita

Muraviev, Nikolai Turgenev, and Mikhail Orlov.

MSTISLAV

980

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Economic stagnation, high taxation, and the

need for major reforms motivated Muraviev and the

other Decembrists to take action. They advocated

the establishment of representative democracy but

disagreed on the form it should take: Muraviev fa-

vored a constitutional monarchy; Pestel, a democ-

ratic republic. To get rid of tsarist agents and

members who were either too dictatorial or too con-

servative, the organizers dissolved the Union of

Welfare in 1821 and set up two new groups: The

Northern Society, centered in St. Petersburg, was

headed by Muraviev and Nicholas Turgenev, an of-

ficial in the Ministry of Finance. The more radical

Southern Society was dominated by Pestel. During

the interregnum between Alexander I and Nicholas

I, the two societies plotted the coup.

Muraviev was the ideologist for the Northern

Society, drafting propaganda and a constitution

that was found among his papers following his ar-

rest. The uncompleted constitutional project reveals

the strong impact of the American constitution.

Like Pestel, he envisioned a republic: “The Russian

nation is free and independent. It cannot be the

property of a person or a family. The people are

the source of supreme power. And to them belongs

the sole right to formulate the fundamental law.”

Muraviev advocated a constitutional monarchy

along the lines of the thirteen original states of

North America, separation of powers, civil liberties,

and the emancipation of the serfs. Although his

constitution guaranteed the equality of all citizens

before the law, the landed classes were recognized

as having special rights and interests. Thus Mu-

raviev rejected Pestel’s idea of universal suffrage;

only property-holders would be allowed to vote

and to seek elective office.

What distinguishes Muraviev’s draft constitu-

tion is its advocacy of federalism, an idea not echoed

by any major political movement in Russia until

the twentieth century. Muraviev argued that “vast

territories and a huge standing army are in them-

selves obstacles to freedom.” Too much of a na-

tionalist to call for the breakup of the empire,

however, Muraviev urged that Russia adopt a fed-

eralist system as a way to reconcile “national

greatness with civic freedom.”

The Decembrist uprising failed because of the

plotters’ incompetence and lack of mass support.

Some defected, and others, at the last minute, failed

to carry out their assignments. Five of their leaders,

including the poet Kondraty Ryleyev, were executed.

Despite the stricter censorship Nicholas I imposed af-

ter the crushed rebellion, the memory of the De-

cembrists inspired many writers and revolutionar-

ies, especially the political refugee Alexander Herzen,

who established the journal The Bell (Kolokol) in Lon-

don in 1857 to “propagate free ideas within Russia.”

See also: DECEMBRIST MOVEMENT AND REBELLION; EM-

PIRE, USSR AS; NICHOLAS I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mazour, Anatole G. (1937). The First Russian Revolution,

1825: The Decembrist Movement, Its Origins, Develop-

ment, and Significance. Stanford, CA: Stanford Uni-

versity Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

MUSAVAT

Founded in secrecy in October 1911, Musavat

(Equality) ultimately grew into the largest, longest-

lived Azerbaijan political party. The founders of the

party were former members of Himmat (Endeavor)

party, Azerbaijan’s first political association, led by

Karbali Mikhailzada, Abbas Kazimzada, and Qulan

Rza Sharifzada. Formation of Musavat was a

response to their disillusionment with the 1905

Russian Revolution. They were also inspired by a

common vision of Turkic identity and Azeri na-

tionalism.

Musavat attracted many of its followers from

among Azerbaijan’s bourgeoisie-intelligentsia, stu-

dents, entrepreneurs, and other professionals; the

party also included workers and peasants among

its ranks. In 1917 a new party evolved from the

initial merger of these former Himmatists and the

Ganja Turkic Party of Federalists, as reflected in the

organization’s name, the Turkic Party of Federal-

ists-Musavat. At this stage Musavat came under the

leadership of Mammad Rasulzade and consisted of

two distinct factions, the Left or Baku faction and

the Right or Ganja faction. These factions differed

on economic and social ideology such as land re-

form, but closed ranks on two crucial issues, one

being secular Turkic nationalism. The other was the

vision of Azerbaijan as an autonomous republic and

part of a Russian federation of free and equal states.

In April 1920, when Azerbaijan came under Soviet

domination, the native intelligentsia were afforded

some amount of accommodation in accordance

with the Soviet nationalist program supervised by

Josef Stalin. However, the accommodation only

extended to the left wing of the Musavat party.

MUSAVAT

981

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Members of the right wing were subsequently im-

prisoned or killed. By 1923 the Musavat came un-

der pressure from communist apparatchiks to

dissolve the organization. Musavat members fortu-

nate enough to flee formed exile communities in

northern Iran or Turkey and remained abroad for

the duration of the Soviet era. The self-proclaimed

successor of the Musavat party, Yeni Musavat Par-

tiyasi (New Musavat Party) was reestablished in

1992. Its leadership was drawn from the Azerbai-

jan Popular Front, an umbrella group representing

a broad spectrum of individuals and groups opposed

to the communist regime in the waning years of

the Soviet Union and active in the post-Soviet tran-

sition. In the early twenty-first century Musavat is

currently in the forefront of the opposition move-

ment in competition with the Popular Front. Yeni

Musavat is characterized as the party of the Azeri

intelligensia and is led by Isa Gambar. The key

planks of the party platform are the liberation of

land captured by Armenian forces in the Karabakh

conflict and forcing the resignation of Heidar Aliev’s

regime, which it views as corrupt and illegitimate.

See also: AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS; CAUCASUS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

European Forum. (1999). “Major Political Parties in Azer-

baijan.” <http://www.europeanforum.bot–consult

.se/cup/azerbaijan/parties.htm>.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. (1972). The Baku Commune, 1917-

1918: Class and Nationality in the Russian Revolution.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Swietockhowski, Tadeusz. (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan:

A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press.

G

REGORY

T

WYMAN

MUSCOVY

The Russian realm that centered around Moscow

until approximately 1713 to 1721 is known as

Muscovy. Historians differ about when to set its

beginning. Moscow is first mentioned in a chron-

icle under the year 1147 as part of Yuri Dolgo-

ruky’s domain. Its first important prince was

Alexander Nevsky’s son Daniel (d. 1303). Between

1301 and 1304, he and his son Yuri (d. 1325) seized

three towns from neighboring Ryazan and

Smolensk, thereby making Moscow an important

center of power within the grand principality of

Vladimir. Yuri’s brother Ivan I (d. 1341), who ob-

tained the right to collect tribute for the Mongols

from other Rus principalities and persuaded the

head of the church to reside in Moscow, established

Moscow’s preeminent position in northern Rus.

Moscow’s territory continued to expand under his

grandson Dmitry Donskoy (r. 1359–1389) and

Dmitry’s progeny down to the end of Daniel’s sub-

dynasty in 1598, with only a few minor setbacks.

Highlights of this growth included the incorpora-

tion of Nizhny Novgorod and Suzdal under Basil I

(r. 1389–1425), Tver, Severia, and Novgorod un-

der Ivan III (r. 1462–1505), Pskov, Smolensk,

and Ryazan under Basil III (r. 1505–1533), the

Volga khanates Kazan and Astrakhan under Ivan

IV (r. 1533–1584), and western Siberia under

Fyodor Ivanovich I (1584–1598). Under Alexei (r.

1645–1676), Russia extended its power across

Siberia to the Pacific Ocean, recovered territory lost

to Poland-Lithuania between 1611 and 1619, added

eastern Ukraine, and became in area the world’s

largest contiguous state. By the time Peter I (r.

1682–1715) moved the capital to St. Petersburg in

1713, he had reacquired eastern Baltic territory lost

to Sweden in 1611 to 1617 and added some more.

He renamed his realm the Russian Empire in 1721.

Internationally, Moscow developed from a sub-

ordinate tributary of the Qipchak khanate (Golden

Horde) to a free successor state in the 1480s, and

then to ruler of the lands of other khanates, start-

ing in the 1550s. Aiming for semantic equality

with other fully sovereign states with imperial pre-

tensions, such as the Ottoman, Persian, and Holy

Roman empires, Moscow had to accept parity with

Poland-Lithuania and Sweden until the Battle of

Poltava in 1709. Refusing a humiliating rank

within the overall European state system and its

diplomatic hierarchy, Muscovy remained ceremo-

nially if not operationally aloof, but with the

Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, it became the first

European state to make a formal agreement with

China.

CHURCH AND CULTURE

Muscovy’s church moved from being the center of

an often all-Rus metropolitanate of the patriarchate

of Constantinople, to an autocephalous eastern Rus

or Russian entity after 1441—the only regional Or-

thodox church ruled essentially by sovereign Or-

thodox rulers—to a patriarchate of its own in 1589

with a sense of pan-Orthodox responsibilities, and

after 1654 to one actually dominating the Kievan

MUSCOVY

982

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY