Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

General Adjutant Milyutin was born in Moscow,

the scion of a Tver noble family. He completed the

gymnasium at Moscow University (1832) and the

Nicholas Military Academy (1836). After a brief pe-

riod with the Guards’ General Staff, he served from

1839 to 1840 with the Separate Caucasian Corps.

While convalescing from wounds during 1840 and

1841, he traveled widely in Europe, where he de-

cided to devote himself to the cause of reform in

Russia. As a professor at the Nicholas Academy

from 1845 to 1853, he founded the discipline of

military statistics and provided the impulse for

compilation of a military-statistical description of

the Russian Empire. In 1852 and 1853 he published

a prize-winning five-volume history of Generalis-

simo A. V. Suvorov’s Italian campaign of 1799.

As a member of the Imperial Russian Geographic

Society he associated with a number of future

reformers, including Konstantin Kavelin, P. P.

Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, Nikolai Bunge, and his

brother, Nikolai Milyutin. An opponent of serfdom,

the future war minister freed his own peasants and

subsequently (in 1856) wrote a tract advocating

the liberation of Russian serfs.

As a major general within the War Ministry

during the Crimean War, Milyutin concluded that

the army required fundamental reform. While

serving from 1856 to 1860 as chief of staff for

Prince Alexander Baryatinsky’s Caucasian Corps,

Milyutin directly influenced the successful outcome

of the campaign against the rebellious mountaineer

Shamil. After becoming War Minister in Novem-

ber 1861, Milyutin almost immediately submitted

to Tsar Alexander II a report that outlined a pro-

gram for comprehensive military reform. The ob-

jectives were to modernize the army, to restructure

military administration at the center, and to create

a territorial system of military districts for peace-

time maintenance of the army. Although efficiency

remained an important goal, Milyutin’s reform leg-

islation also revealed a humanitarian side: abolition

of corporal punishment, creation of a modern mil-

itary justice system, and a complete restructuring

of the military-educational system to emphasize

spiritual values and the welfare of the rank-and-

file. These and related changes consumed the war

minister’s energies until capstone legislation of

1874 enacted a universal military service obliga-

tion. Often in the face of powerful opposition,

Milyutin had orchestrated a grand achievement, al-

though the acknowledged price included increased

bureaucratic formalism and rigidity within the

War Ministry.

Within a larger imperial context, Milyutin con-

sistently advanced Russian geopolitical interests

and objectives. He favored suppression of the Pol-

ish uprising of 1863–1864, supported the conquest

of Central Asia, and advocated an activist policy in

the Balkans. On the eve of the Russo-Turkish War

of 1877–1878, he endorsed a military resolution of

differences with Turkey, holding that the Eastern

Question was primarily Russia’s to decide. During

the war itself, he accompanied the field army into

the Balkans, where he counseled persistence at

Plevna, asserting that successful resolution of the

battle-turned-siege would serve as prelude to fur-

ther victories. After the war, Milyutin became the

de facto arbiter of Russian foreign policy.

Within Russia, after the Berlin Congress of

1878, Milyutin pressed for continuation of Alexan-

der II’s Great Reforms, supporting the liberal

program of the Interior Ministry’s Mikhail Loris-

Melikov. However, after the accession of Alexander

III and publication in May 1881 of an imperial

manifesto reasserting autocratic authority, Mi-

lyutin retired to his Crimean estate. He continued

to maintain an insightful diary and commenced his

memoirs. The latter grew to embrace almost the

entire history of nineteenth-century Russia, with

important perspectives on the Russian Empire and

contiguous lands and on its relations with Europe,

Asia, and America.

See also: MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; GREAT REFORMS; MIL-

ITARY; SUVOROV, ALEXANDER VASILIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brooks, Edwin Willis. (1970). “D. A. Miliutin: Life and

Activity to 1856.” Ph.D. diss., Stanford University,

Stanford, CA.

Menning, Bruce W. (1992, 2000). Bayonets before Bullets:

The Imperial Russian Army, 1861–1914. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press.

Miller, Forrestt A. (1968). Dmitrii Miliutin and the Reform

Era in Russia. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

L

ARISSA

Z

AKHAROVA

MILYUTIN, NIKOLAI ALEXEYEVICH

(1818–1870), government official and reformer.

Nikolai Milyutin was born into a well-con-

nected noble family of modest means. One of his

brothers, Dmitry, would serve as Minister of War

MILYUTIN, NIKOLAI ALEXEYEVICH

943

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

from 1861 to 1881. Nikolai entered government

service at the age of seventeen and served in the

Ministry of Internal Affairs from 1835 until 1861.

A succession of ministers, recognizing his industry

and talent, had him draft major reports to be is-

sued in their names. He was largely responsible for

compiling the Urban Statute of 1846, which, as

applied to St. Petersburg and then to other large

cities, somewhat expanded the number of persons

who could vote in city elections.

Until 1858, Milyutin was a relatively obscure

functionary. In the next six years he was the prin-

cipal author of legislation that fundamentally

changed the Russian empire: the Statutes of Feb-

ruary 19, 1861, abolishing serfdom; the legislation

establishing elective agencies of local self-adminis-

tration (zemstva), enacted in 1864; and legislation

intended to end the sway of the Polish nobility af-

ter their participation in the insurrection of 1863.

He exercised this influence although the highest po-

sition he held was Acting Deputy Minister of In-

ternal Affairs from 1859 to 1861—“acting” because

Alexander II supposed that he was a radical. He was

dismissed as deputy minister as soon as the peas-

ant reform of 1861 was safely enacted.

In the distinctive political culture of autocratic

Russia, Milyutin demonstrated consummate skill

and cunning as a politician. None of the core con-

cepts of the legislation of 1861 was his handiwork.

He was, however, able to persuade influential per-

sons with access to the emperor, such as the Grand

Duchess Yelena Pavlovna, to adopt and promote

these concepts. He was able, in a series of memo-

randa written for the Minister of Internal Affairs

Sergei Lanskoy, to persuade the emperor to turn

away from his confidants who opposed the emerg-

ing reform and to exclude the elected representa-

tives of the nobility from the legislative process.

And, as chairman of the Economic Section of the

Editorial Commission, a body with ostensibly an-

cillary functions, he was able to mobilize a frac-

tious group of functionaries and “experts” and lead

them in compiling the legislation enacted in 1861.

Almost simultaneously he served as chairman

of the Commission on Provincial and District In-

stitutions. In that capacity he drafted the legisla-

tion establishing the zemstvo, an institution which

enabled elected representatives to play a role in lo-

cal affairs, such as education and public health. The

reform was also significant because the regime

abandoned the principle of soslovnost, or status

based on membership in one of the hereditary es-

tates of the realm, which had been the lodestone of

government policy for centuries. To be sure, the

landed nobility, yesterday’s serfholders, were guar-

anteed a predominant role, since there were prop-

erty qualifications for the bodies that elected

zemstvo delegates.

Concerning the “western region” (Eastern

Poland), Milyutin rewrote the legislation of Febru-

ary 19 so that ex-serfs received their allotments of

land gratis and landless peasants were awarded

land, often land expropriated from the Catholic

Church. He wished to bind the peasants, largely

Orthodox Christians, to the regime and detach

them from the Roman Catholic nobles, who had

risen in arms against it.

Milyutin was well aware of the shortcomings

of the reform legislation he produced. He counted

on the autocracy to continue its reform course and

eliminate these shortcomings. His expectations

were not realized. It is the paradox and perhaps the

tragedy of Milyutin that, despite his reputation as

a “liberal,” he saw the autocracy as the essential

instrument to produce a prosperous, modern, and

law-governed Russia.

See also: EMANCIPATION ACT; MILYUTIN, DMITRY ALEX-

EYEVICH; PEASANTRY; SERFDOM; ZEMSTVO

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Field, Daniel. (1976). The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bu-

reaucracy in Russia, 1856–1861. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1982). In the Vanguard of Reform: Rus-

sia’s Enlightened Bureaucrats, 1825–1861. DeKalb:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Zakharova, Larissa. (1994). “Autocracy and the Reforms

of 1861–1874 in Russia.” In Russia’s Great Reforms,

1855–1881, eds. B. Eklof, J. Bushnell, and L. G. Za-

kharova. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

D

ANIEL

F

IELD

MINGRELIANS

Mingrelians call themselves Margali (plural Mar-

galepi) and are Georgian Orthodox. Mingrelian (like

Georgian, Svan, and Laz) is a South Caucasian

(Kartvelian) language; only Mingrelian and Laz,

jointly known as Zan, are mutually intelligible.

MINGRELIANS

944

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The ancient Zan continuum along the Black Sea’s

eastern coast from Abkhazia to Rize was broken

by Georgian speakers fleeing the Arab emirate

(655–1122) in Georgia’s modern capital Tiflis, so that

Georgian-speaking provinces (Guria and Ajaria) now

divide Mingrelia (western Georgian lowlands

bounded by Abkhazia, Svanetia, Lechkhumi, Imere-

tia, Guria, and the Black Sea) from Lazistan (north-

eastern Turkey). The Dadianis ruled post-Mongol

Mingrelia (capital Zugdidi), which came under Rus-

sian protection in 1803, although internal affairs re-

mained in local hands until 1857. Traditional home

economy resembled that of neighboring Abkhazia.

A late-nineteenth-century attempt to introduce

a Mingrelian prayer book and language primer us-

ing Cyrillic characters failed; it was interpreted as a

move to undermine the Georgian national move-

ment’s goal of consolidating all Kartvelian speakers.

In the 1926 Soviet census, 242,990 declared Min-

grelian nationality, a further 40,000 claiming Min-

grelian as their mother tongue. This possibility (and

thus these data) subsequently disappeared; since

around 1930, all Kartvelian speakers have officially

been categorized as “Georgians.” Today Mingrelians

may number over one million, though fewer speak

Mingrelian. Some publishing in Mingrelian (with

Georgian characters), especially of regional newspa-

pers and journals, was promoted by the leading

local politician, Ishak Zhvania (subsequently de-

nounced as a separatist), from the late 1920s to

1938, after which only Georgian, the language in

which most Mingrelians are educated, was allowed

(occasional scholarly works apart). While some

Mingrelian publishing has restarted since Georgian

independence, Mingrelian has never been formally

taught. Stalin’s police chief, Lavrenti Beria, and Geor-

gia’s first post-Soviet president, Zviad Gamsakhur-

dia, were Mingrelians. The civil war that followed

Gamsakhurdia’s overthrow (1992) mostly affected

Mingrelia, where Zviadist sympathizers were con-

centrated; even after Gamsakhurdia’s death (1993),

local discontent with the central authorities fostered

at least two attempted coups, reinforcing long-

standing Georgian fears of separatism in the area.

See also: ABKHAZIANS; CAUCASUS; GEORGIA AND GEOR-

GIANS; SVANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hewitt, George. (1995). “Yet a third consideration of

Völker, Sprachen und Kulturen des südlichen Kaukasus.”

Central Asian Survey 14(2):285– 310.

B. G

EORGE

H

EWITT

MININ, KUZMA

(d. 1616), organizer, fundraiser, and treasurer of

the second national liberation army of 1611–1612.

Kuzma Minin was elected as an elder of the

townspeople of Nizhny Novgorod in September

1611, when Moscow was still occupied by the Poles.

After the disintegration of the first national libera-

tion army, Minin began to raise funds for the orga-

nization of a new militia. Its nucleus was provided

by the garrison of Nizhny Novgorod and neighbor-

ing Volga towns, together with some refugee ser-

vicemen from the Smolensk region. At the request

of Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, the military comman-

der of the new army, Minin became its official trea-

surer. When the militia was based at Yaroslavl, in

the spring of 1612, Minin was an important mem-

ber of the provisional government headed by

Pozharsky. After the liberation of Moscow in Octo-

ber 1612, Minin, together with Pozharsky and Prince

Dmitry Trubetskoy, played a major role in conven-

ing the Assembly of the Land, which elected Mikhail

Romanov tsar in January 1613. On the day after

Mikhail’s coronation, Minin was appointed to the

rank of dumny dvoryanin within the council of bo-

yars; he died shortly afterwards. Along with

Pozharsky, Minin became a Russian national hero

who served as a patriotic inspiration in later wars.

In early Soviet historiography, his merchant status

led him to be viewed as a representative of bourgeois

reaction against revolutionary democratic elements

such as cossacks and peasants. By the late 1930s he

was again seen as a patriot, and his relatively hum-

ble social origin made him particularly acceptable as

a popular hero during World War II.

See also: ASSEMBLY OF LAND; POZHARSKY, DMITRY

MIKHAILOVICH; TIME OF TROUBLES; COSSACKS; MER-

CHANTS; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunning, Chester L. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War: The

Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dy-

nasty. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Uni-

versity Press.

Perrie, Maureen. (2002). Pretenders and Popular Monar-

chism in Early Modern Russia: The False Tsars of the

Time of Troubles, paperback ed. Cambridge, UK: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Skrynnikov, Ruslan G. (1988). The Time of Troubles: Rus-

sia in Crisis, 1604–1618, ed. and tr. Hugh F. Gra-

ham. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International Press.

M

AUREEN

P

ERRIE

MININ, KUZMA

945

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MINISTRIES, ECONOMIC

The industrial ministries of the Soviet Union were

intermediate bodies that dealt directly with pro-

duction enterprises. They played a key role in re-

source allocation and were directly responsible for

the implementation of state industrial policy as de-

veloped and adopted by the Communist Party. In

fact, ministers had two lines of responsibilities: one

to the Council of Ministers, and the other, more

important in the long run, to the Party’s Central

Committee. The most important ministers were

members of Politburo. The ministries negotiated

output targets and input limits with Gosplan,

which was responsible for fulfilling the directives

of the party and the Council of Ministers.

Once output and input targets were set, the

ministries organized the activities of their enter-

prises to achieve output targets and stay within in-

put limits. Normally the ministries petitioned

Gosplan to reconsider their output and input tar-

get figures if plan fulfillment was threatened. This

practice was called corrections (korrektirovka). Nor-

mally aimed at decreasing planned outputs, it was

a common practice, although widely condemned

by Party officials. The Council of Ministers had the

formal authority to decide on these petitions, but

in most cases the actual decision was left to Gos-

plan. The minister or his deputy and even heads of

ministry main administrations (glavki) were mem-

bers of the Council of Ministers and participated in

its sessions. Most of the operational work of the

ministries was done by the main administrations.

The industrial ministries were the fund hold-

ers (fondoderzhateli) of the economy. Gosplan and

Gossnab (State Committee for Material Technical

Supply) allocated the most important industrial

raw materials, equipment, and semifabricates to

the industrial ministries. Moreover, the ministries

had their own supply departments that worked

with Gossnab. Centrally allocated materials were

called funded (fondiruyemie) commodities, which

were allocated to the enterprises only by ministries.

Enterprises were not legally allowed to exchange

funded goods, although they did so.

The ministries existed at three levels. The most

important were the All-Union ministries (Soyuznoe

ministerstvo). Based in Moscow, All-Union min-

istries managed an entire branch of the economy,

such as machine-building, coal, or electrical prod-

ucts. They concentrated enormous power and fi-

nancial and material resources, and controlled the

most important sectors of the economy. Ministries

of the military-industrial complex were concen-

trated in Moscow. They obtained priority funds

and limits allocated by Gosplan. Similarly, the sig-

nificance of corresponding ministers was very

high—they were the direct masters of the enter-

prises located in all republics that constituted the

Soviet Union.

At the second level were the ministries of dual

subordination—the Union-Republican Ministry

(Soiuzno-respublikanskoe ministerstvo). As a rule,

their headquarters were in Moscow. While the cap-

itals of individual republics were the sites of re-

public-specific branches that conducted everyday

activities, plan approval and resource allocation

were subordinated to Moscow. Among the dual

subordination ministries were the ministries of the

coal industry, food industry, and construction.

For example, Ukraine produced a bulk of Soviet

coal and food output; therefore Union-ministry

branches were located in its capital, Kiev.

The republican ministries occupied the lowest

level. They were controlled by the republican Coun-

cils of Ministers and the Republican Central Com-

mittees of the Communist Party. They produced

primarily local and regional products.

There were also committees under the Council

of Ministers that enjoyed practically the same

rights as the ministries: for example, the State

Committee on Radio and Television, or the notori-

ous KGB, which nominally was a committee but

probably enjoyed a wide scope of powers.

A typical ministry was run by the minister

and by deputy ministers who supervised corre-

sponding glavki that, in their turn, controlled all

work under their jurisdiction. A special glavk was

responsible for logistical aspects of the industry’s

performance; technical glavki were in charge of the

planning of the industry’s plant operations.

The ministries had authorized territorial repre-

sentatives in major administrative centers of the So-

viet Union who directly supervised the plant’s

operations. The ministry, however, was dependent

on its subordinated enterprises for information. The

enterprises possessed better local information and

were reluctant to share this information with the

ministry.

Ministries had their own scientific and research

institutes and higher education establishments that

trained professionals for the industry. The indus-

trial ministries were expected to perform a wide va-

MINISTRIES, ECONOMIC

946

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

riety of tasks: to plan production, manage mater-

ial and technical supply, arrange transportation,

develop scientific policy, and plan capital invest-

ment.

The ministers were responsible for the perfor-

mance of their enterprises as a whole; at the same

time, the employees were not motivated and did

not have any incentives to work creatively and to

their full potential. The bulk of ministerial decision

making was devoted to implementing and moni-

toring the operational plan after the annual plan

had been approved. Under constant pressure to

meet plan targets, industrial ministries exercised

opportunistic behavior: that is, they bargained for

lower output targets, demanded extra inputs, and

exploited horizontal and vertical integration strate-

gies to achieve more independence from centralized

supplies.

During the later period of the Soviet Union,

many attempts were made to improve the work of

industrial ministries to make them more effective

and efficient. However, these attempts were incon-

sistent, and the number of bureaucrats was hardly

reduced. The giant administrative superstructure of

the ministries was a heavy burden on the economy

and played an increasingly regressive role. It was

partially responsible for the economic collapse of

Soviet economy. The ministerial bureaucracy con-

tinued to play an important role after the collapse

of the Soviet Union. In Russia, for example, former

ministerial officials gained control of significant

chunks of industry during the privatization

process.

See also: COMMAND ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY; GOS-

PLAN; INDUSTRIALIZATION, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure.

Boston, MA: Addison Wesley.

Hewett, Edward A. (1988). Reforming the Soviet Economy:

Equality Versus Efficiency. Washington, DC: Brook-

ings Institution.

P

AUL

R. G

REGORY

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN TRADE

The Ministry of Foreign Trade was a functional

ministry subordinate to Gosplan and the Council

of Ministers that was responsible for foreign trade

in the Soviet economy.

It was a functional ministry in that its jurisdic-

tion cut across the responsibilities of the various

branch ministries that managed production and dis-

tribution of products. It reported directly to Gosplan

and the Council of Ministers. The operating units of

the Ministry of Foreign Trade were the Foreign Trade

Organizations (FTOs), which controlled exports and

imports of specific goods, such as automobiles, air-

craft, books, and so forth.

Soviet enterprises generally had no authority or

means to export or import to or from abroad. The

relevant FTO responded to requests from enterprises

under its jurisdiction and, if approved, conducted ne-

gotiations, financing, and all other arrangements

necessary for the transaction. Imports and exports,

and thus the FTOs and the Ministry of Foreign Trade,

were subject to the overall annual and quarterly eco-

nomic plans. In this way, foreign trade was utilized

to complement rather than to compete with the plan.

See also: COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, SOVIET; FOREIGN TRADE;

GOSPLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (1990). Soviet Eco-

nomic Structure and Performance, 4th ed. New York:

HarperCollins.

Hewett, Ed A. (1988). Reforming the Soviet Economy:

Equality versus Efficiency. Washington, DC: The

Brookings Institution.

J

AMES

R. M

ILLAR

MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS

The extent to which Russian regimes have depended

upon the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD, Min-

isterstvo vnutrennykh del) is symbolized by its sur-

viving the fall of tsarism and the end of the Soviet

Union intact and with almost the same name. The

ministry’s ancestry runs as far back as the six-

teenth century, when Ivan the Terrible established

the Brigandage Office to combat banditry. How-

ever, a formal Ministry of Internal Affairs was not

founded until 1802. From the first, its primary re-

sponsibility was to protect the interests of the state,

and this was so even before it was made responsi-

ble for the Okhranka, or political police, in 1880.

The close relationship between regular policing and

MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AFFAIRS

947

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

political control has been a central characteristic of

the MVD throughout its existence.

The Bolsheviks came to power with utopian

notions of policing by social consent and public vol-

untarism, but because of the new regime’s au-

thoritarian tendencies and the exigencies of the Civil

War (1918–1921), it became necessary, by 1918,

to transform the “workers’ and peasants’ militia”

into a full-time police force; one year later the mili-

tia was militarized. Originally envisaged as locally

controlled forces loosely subordinated to the Peo-

ple’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), the

militia, in practice, were soon closely linked with

the Cheka political police force and subject to cen-

tral control. The NKVD was increasingly identified

with political policing; in 1925, the militia and the

Cheka’s successor, the OGPU (Unified State Politi-

cal Directorate), were combined, and in 1932 the

NKVD was formally subordinated to the OGPU.

Two years later, the roles were technically reversed,

with the OGPU absorbed into the NKVD, but in

practice this actually reflected the colonization of

the NKVD by the political police.

The concentration of law enforcement in the

hands of the political police well suited the needs

of Josef V. Stalin during the era of purges and col-

lectivization, but in 1941 the regular and political

police were once again divided. Regular policing

again became the responsibility of the NKVD, while

the political police became the NKGB, the People’s

Commissariat of State Security. After the war, the

NKVD regained the old title of the Ministry of In-

ternal Affairs, and the NKGB became the MGB,

Ministry of State Security. The political police re-

mained very much the senior service, and for a

short time (1953–1954) the MVD was reabsorbed

into the MGB (which then became the Committee

of State Security, KGB), but from this point the reg-

ular and political police became increasingly dis-

tinct agencies, each with a sense of its own role,

history, and identity.

The police and security forces remained a key

element of the Communist Party’s apparatus of po-

litical control and thus the subject of successive re-

forms, generally intended to strengthen both their

subordination to the leadership and their author-

ity over the masses. In 1956, reflecting concerns

among the elite about the power of the security

forces, the MVD was decentralized. In 1960, the

USSR MVD was dissolved, and day-to-day control

of the police passed to the MVDs of the constituent

Union republics. In practice, though, the law codes

of the republics mirrored their Russian counterpart,

and the republican ministries were essentially local

agencies for the central government. In 1968 the

USSR MVD was reorganized in name as well

as practice, after yet one more name change (Min-

istry for the Defense of Public Order, MOOP,

1962–1968).

The structure of the Ministry for Internal Af-

fairs has not significantly changed, and thus the

post-Soviet Russian MVD is similar in essence and

organization, if not in scale. In 1991, Boris Yeltsin

tried to merge the MVD and the security agencies

into a new “super-ministry,” but this was blocked

by the Constitutional Court and the idea was

dropped. Other reforms were relatively minor, such

as the transfer of responsibility for prisons to the

Justice Ministry.

As guarantor of the Kremlin’s authority, the

MVD controls a sizea ble militarized security force,

the Interior Troops (VV). At its peak, in the early

1980s, this force numbered 300,000 officers and

men, and its strength of 193,000 in 2003 actually

reflected an increase in its size in proportion to the

regular army. In the post-Soviet era, most VV units

are local garrison forces, largely made up of con-

scripts, but there are also small commando forces

as well as the elite Dzerzhinsky Division, based on

the outskirts of Moscow, which has its own ar-

mored elements and artillery.

See also: STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Galeotti, Mark. (1993). “Perestroika, Perestrelka, Pere-

borka: Policing Russia in a Time of Change.” Europe-

Asia Studies 45:769–786.

Orlovsky, Daniel. (1981). The Limits of Reform. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shelley, Louise. (1996). Policing Soviet Society. London:

Routledge.

Weissman, Neil. (1985). “Regular Police in Tsarist Rus-

sia, 1990–1914.” Russian Review 44:45–68.

M

ARK

G

ALEOTTI

MIR

The word mir in Russian has several meanings. In

addition to “community” and “assembly,” it also

means “world” and “peace.” These seemingly diverse

meanings had a common historical origin. The vil-

lage community formed the world for the peasants,

MIR

948

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

where they tried to keep a peaceful society. Thus

mir was, in all probability, a peasant-given name

for a spontaneously generated peasant organization

in early Kievan or pre-Kievan times. It was men-

tioned in the eleventh century in the first codifica-

tion of Russian law, Pravda Russkaya, as a body of

liability in cases of criminal offense.

Over time, the meaning of mir changed, de-

pending on the political structure of the empire,

and came to mean different things to different peo-

ple. For peasants and others, mir presumably was

always a generic term for peasant village-type

communities with a variety of structures and func-

tions. The term also denoted those members of a

peasant community who were eligible to discuss

and decide on communal affairs. At the top of a

mir stood an elected elder.

Contrary to the belief of the Slavophiles, com-

munal land redistribution had no long tradition as

a function of the mir. Until the end of the seven-

teenth century, individual land ownership was

common among Russian peasants, and only special

land holdings were used jointly. All modern char-

acteristics, such as egalitarian landholding and land

redistribution, developed only as results of changes

in taxation, as the poll tax was introduced in 1722

and forced upon the peasants by the landowners,

who sought to distribute the allotments more

equally and thus get more return from their serfs.

In the nineteenth century, mir referred to any

and all of the following: a peasant village group as

the cooperative owner of communal land property;

the gathering of all peasant households of a village

or a volost to distribute responsibility for taxes and

to redistribute land; a peasant community as the

smallest cell of the state’s administration; and,

most importantly, the entire system of a peasant

community with communal property and land

tenure subject to repartitioning. The peasant land

was referred to as mirskaya zemlia.

Only at the end of the 1830s did a second term,

obshchina, come into use for the village commu-

nity. Unlike the old folk word mir, the term ob-

shchina was invented by the Slavophiles with the

special myth of the commune in mind. This term

specifically designated the part of the mir’s land

that was cultivated individually but that was also

redistributable. The relation between both terms is

that an obshchina thus coincided with some aspects

of a mir but did not encompass all of the mir’s

functions. The land of an obshchina either coin-

cided with that of a mir or comprised a part of mir

holdings. Every obshchina was perforce related to

a mir, but not every mir was connected with an

obshchina, because some peasants held their land

in hereditary household tenure and did not redis-

tribute it. With increasing confusion between both

terms, most educated Russians probably equated

mir and obshchina from the 1860s onward. Ob-

shchina was also used for peasant groups lacking

repartitional land.

Although the mir was an ancient form of peas-

ant self-administration, it was also the lowest link

in a chain of authorities extending from the indi-

vidual peasant to the highest levels of state control.

It was responsible to the state and later to the

landowners for providing taxes, military recruits,

and services. The mir preserved order in the village,

regulated the use of communal arable lands and

pastures, and until 1903 was collectively respon-

sible for paying government taxes. Physically, the

mir usually coincided with one particular settle-

ment or village. However, in some cases it might

comprise part of a village or more than one village.

As its meaning no longer differed from obshchina,

the term mir came out of use at the beginning of

the twentieth century.

See also: OBSHCHINA; PEASANT ECONOMY; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Grant, Steven A. (1976). “Obshchina and Mir.” Slavic Re-

view 35:636–651.

Moon, David. (1999). The Russian Peasantry 1600–1930:

The World the Russian Peasants Made. London: Long-

man.

Robinson, Geroid T. (1967). Rural Russia under the Old

Regime. Berkeley: University of California Press.

S

TEPHAN

M

ERL

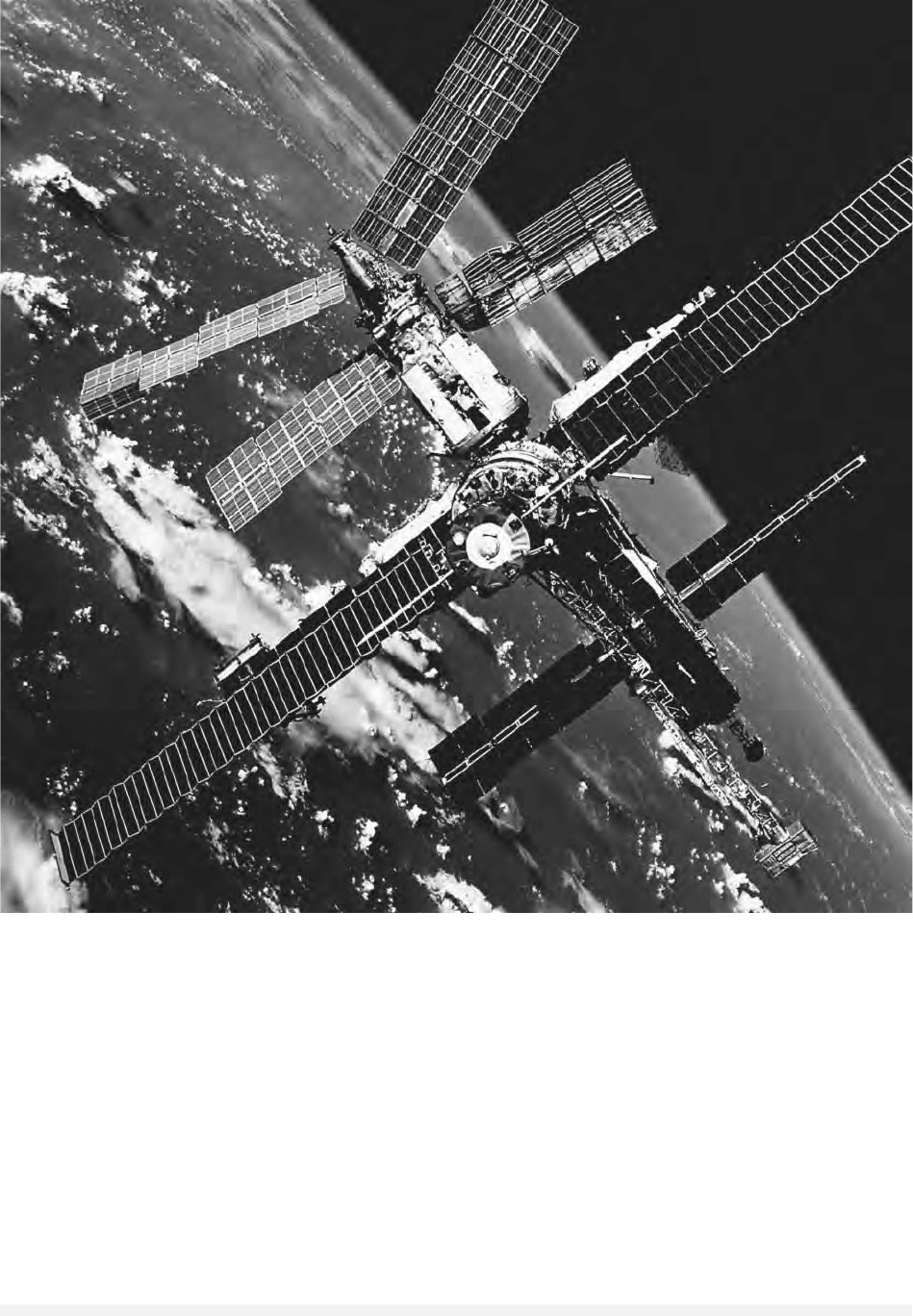

MIR SPACE STATION

The Mir (“world”) space station was a modular

space facility providing living and working ac-

commodations for cosmonauts and astronauts

during its fifteen-plus years in orbit around the

Earth. The core module of Mir was launched on

February 20, 1986, and the station complex was

commanded to a controlled re-entry into the earth’s

atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 23,

2001, where its parts either burned up or sank in

the ocean.

MIR SPACE STATION

949

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The core module provided basic services—living

quarters, life support, and power—for those stay-

ing aboard Mir. In subsequent years, five additional

modules were launched and attached to the core to

add to the research and crew support capabilities

of the space station; the last module was attached

in 1996.

More than one hundred cosmonauts and as-

tronauts visited Mir during its fifteen years in or-

bit. One, Soviet cosmonaut Valery Polyakov, stayed

in orbit for 438 days, the longest human space

flight in history. Beginning in 1995, the U.S. space

shuttle carried out docking missions with Mir, and

seven U.S. astronauts stayed on Mir for periods

ranging from 115 to 188 days. These Shuttle-Mir

missions were carried out in preparation for Russian-

U.S. cooperation in the International Space Station

program.

Toward the end of its time in orbit, there was

an attempt to turn Mir into a facility operated on

MIR SPACE STATION

950

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Russian Space Station MIR, photographed from the cargo bay of the U.S. Space Shuttle Atlantis. © AFP/CORBIS

a commercial basis: for instance, allowing noncos-

monauts to purchase a trip to the station. How-

ever, Mir was de-orbited before such a trip took

place.

The primary legacy of Mir is the extensive ex-

perience it provided in the complexities of organiz-

ing and managing long-duration human space

flights, as well as insights into the effect of long

stays in space on the human body. As the Mir sta-

tion aged, keeping it in operating condition became

a full-time task for its crew, and this limited its

scientific output.

See also: INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION; SPACE PRO-

GRAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burrough, Bryan. (1998). Dragonfly: NASA and the Cri-

sis aboard Mir. New York: HarperCollins.

J

OHN

M. L

OGSDON

MNISZECH, MARINA

(1588–1614), Polish princess and Tsaritsa of Rus-

sia (1606).

Marina Mniszech was the daughter of Jerzy

Mniszech (Palatine of Sandomierz), a Polish aristo-

crat who took up the cause of the man claiming

to be Dmitry of Uglich in his struggle against Tsar

Boris Godunov. The intelligent and ambitious Ma-

rina met the Pretender Dmitry in 1604, and they

agreed to marry once he became tsar. After invad-

ing Russia and toppling the Godunov dynasty, Tsar

Dmitry eventually obtained permission from the

Russian Orthodox Church to marry the Catholic

princess. In May 1606, Marina made a spectacular

entry into Moscow, and she and Tsar Dmitry were

married in a beautiful ceremony.

On May 17, 1606, Tsar Dmitry was assassi-

nated, and Marina and her father were taken pris-

oner and incarcerated for two years. Tsar Vasily

Shuisky released them in 1608 on the condition that

they head straight back to Poland and not join up

with an impostor calling himself Tsar Dmitry who

was then waging a bitter civil war against Shuisky.

In defiance, Marina traveled to Tushino, the second

false Dmitry’s capital in September 1608, and rec-

ognized the impostor as her husband, thereby

greatly strengthening his credibility. Tsaritsa Ma-

rina even produced an heir, Ivan Dmitrievich. When

Marina’s “husband” was killed in 1610, she and her

lover, the cossack commander Ivan Zarutsky, con-

tinued to struggle for the Russian throne on behalf

of the putative son of Tsar Dmitry. Forced to re-

treat to Astrakhan, Marina, Zarutsky, and Ivan

Dmitrievich held out until after the election of Tsar

Mikhail Romanov in 1613. Eventually expelled

from Astrakhan’s citadel, the three were hunted

down in the Ural Mountain foothills and executed

in 1614.

See also: DMITRY, FALSE; DMITRY OF UGLICH; OTREPEV,

GRIGORY; SHUISKY, VASILY IVANOVICH; TIME OF

TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunning, Chester. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War: The

Time of Troubles and the Founding of The Romanov Dy-

nasty. University Park: Pennsylvania State Univer-

sity Press.

Perrie, Maureen. (1995). Pretenders and Popular Monar-

chism in Early Modern Russia: The False Tsars of the

Time of Troubles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

C

HESTER

D

UNNING

MOISEYEV, MIKHAIL ALEXEYEVICH

(b. 1939), Army General Chief of the Soviet Gen-

eral Staff from 1988 to 1991.

Mikhail Moiseyev, born January 2, 1939, in

Amur Oblast, was raised in the Soviet Far East and

attended the Blagoveshchensk Armor School. He

joined the Soviet Armed Forces in 1961 and served

with tank units. Moiseyev attended the Frunze Mil-

itary Academy from 1969 to 1972 and rose rapidly

to the Rank of General-Major in the late 1970s. He

graduated from the Voroshilov Military Academy

of the General Staff as a gold medalist in 1982.

Moiseyev enjoyed the patronage of several se-

nior officers in the advancement of his career, in-

cluding General E. F. Ivanovsky, I. M. Tretyak, and

Dmitri Yazov. In the 1980s Moiseyev commanded

a combined arms army and then the Far East Mil-

itary District. With the resignation of Marshal

Sergei Akhromeyev in December 1988, Moiseyev

was appointed chief of the Soviet General Staff, a

post he held until August 22, 1991, when he was

removed because of his support for the hard-

liners’ coup. His tenure saw the culmination of

intense arms control negotiations, including the

MOISEYEV, MIKHAIL ALEXEYEVICH

951

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty; the de-

establishment of the Warsaw Treaty Organization;

and increased military activism in domestic poli-

tics. In 1992 Moiseyev defended his dissertation,

“The Armed Forces Command Structure,” at the

Center for Military-Strategic Studies of the General

Staff. He served as a military consultant to the

Russian Supreme Soviet in 1992.

Following his retirement, Moiseyev joined the

board of the Technological and Intellectual Devel-

opment of Russia Joint-Stock Company. In De-

cember 2000 he founded a new political party,

Union, which was supposed to attract the support

of active and returned military and security offi-

cers under the slogan, “law, order, and the rule of

law.” President Vladimir Putin appointed Moiseyev

to the governmental commission on the social pro-

tection of the military. In this capacity he has been

involved in programs to provide assistance to re-

tiring military personnel.

See also: ARMS CONTROL; AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; MILI-

TARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borawski, John. (1992). Security for a New Europe: The

Vienna Negotiations on Confidence- and Security-

Building Measures, 1989–90 and Beyond. London:

Brassey’s.

Golts, Aleksandr. (2002). “Trend Could Hatch Dozens of

Pinochets.” The Russian Journal 40(83).

Green, William C., and Karasik, Theodore, eds. (1990).

Gorbachev and His Generals: The Reform of Soviet Mil-

itary Doctrine. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Mil-

itary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

MOLDOVA AND MOLDOVANS

The independent Republic of Moldova has an area

of 33,843 square kilometers (13,067 square miles).

It is bordered by Romania on the west and by

Ukraine on the north, east, and south. The popu-

lation of as of 2002 was approximately 4,434,000.

Moldova’s population is ethnically mixed: Moldo-

vans, who share a common culture and history

with Romanians, make up 64.5 percent of the

total population. Other major groups include

Ukrainians (13.8%), Russians (13%), Bulgarians

(2.0%), and the Turkic origin Gagauz (3.5%). Ap-

proximately 98 percent of the population is East-

ern Orthodox.

Historically, the region has been the site of con-

flict between local rulers and neighboring powers,

particularly the Ottoman Empire and Russian Em-

pires. An independent principality including the

territory of present-day Moldova was established

during the mid-fourteenth century

C

.

E

. During the

late fifteenth century it came under increasing pres-

sure from the Ottoman Empire and ultimately be-

came a tributary state. The current differentiation

between eastern and western Moldova began dur-

ing the early eighteenth century. Bessarabia, the re-

gion between the Prut and Dniester rivers, was

annexed by Russia following the Russo-Turkish

war of 1806–1812. Most of the remainders of tra-

ditional Moldova were united with Walachia in

1858, forming modern Romania.

While under Russian rule, Bessarabia experi-

enced a substantial influx of migrants, primarily

Russians, Ukrainians, Bulgarians, and Gagauz.

Bessarabia changed hands again once again in

1918, uniting with Romania as a consequence of

World War I. Soviet authorities created a new

Moldovan political unit, designated the Moldavian

Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, on Ukrain-

ian territory containing a Romanian-speaking

minority to the east of the Dniester River. In June

1940, Romania ceded Bessarabia to the Soviet

Union as a consequence of the Ribbentrop-Molotov

agreement, allowing formation of the Soviet So-

cialist Republic of Moldavia.

Independence culminated a process of national

mobilization that began in 1988 in the context of

widespread Soviet reforms. In the first partly de-

mocratic elections for the Republican Supreme So-

viet, held in February 1990, candidates aligned with

the Moldovan Popular Front won a majority of

seats. The Supreme Soviet declared its sovereignty

in June 1990. The Republic of Moldova became in-

dependent on August 27, 1991. The current con-

stitution was enacted on July 29, 1994.

Moldova’s sovereignty was challenged by

Russian-speaking inhabitants on the left bank of

the Dniester (Trans-Dniestria), and the Gagauz

population concentrated in southern Moldova. The

Gagauz crisis was successfully ended in December

1994 through a negotiated settlement that estab-

lished an autonomous region, Gagauz-Yeri, within

Moldova. The Trans-Dniestrian secession remains

unresolved. Regional authorities declared indepen-

MOLDOVA AND MOLDOVANS

952

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY