Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MOROZOV, BORIS IVANOVICH

(1590–1661), lord protector and head of five chan-

celleries under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

Boris Ivanov syn Morozov was an important,

thoughtful leader, but he also stands out as an ex-

ceptionally greedy figure of the second quarter of

the seventeenth century. His cupidity provoked up-

risings in early June 1648 in Moscow and then in

a dozen other towns, forcing Tsar Alexei to con-

voke the well-known Assembly of the Land of

1648–1649, the product of which was the famous

Law Code of 1649.

Morozov in some ways personified the fact that

early modern Russia (Muscovy) was a service state.

He was not of princely (royal) origins; his ances-

tors had been commoners who rose through ser-

vice to the ruler of Muscovy. Thus his patronymic

would have been Ivanov Syn (son of Ivan), rather

than Ivanovich, which would have been the proper

form were he if noble origin.

By 1633 Morozov was tutor to the heir to the

throne, the future Tsar Alexei. He and Alexei mar-

ried Miloslavskaya sisters. After Alexis came to the

throne, Morozov became head of five chancelleries

(prikazy, the “power ministries”: Treasury, Alcohol

Revenues, Musketeers, Foreign Mercenaries, and

Apothecary) and de facto ruler of the government

(Lord Protector). He observed that there were too

many taxes and came up with the apparently in-

genious solution of canceling a number of them

and concentrating the imposts in an increased tax

on salt. Regrettably Morozov was not an econo-

mist and probably could not comprehend that

the demand for salt was elastic. Salt consumption

plummeted—and so did state revenues—while pop-

ular discontent rose.

As Morozov took over the government, he

brought a number of equally corrupt people with

him. They abused the populace, provoking a rebel-

lion in June 1648. The mob tore one of his cocon-

spirators to bits and cast his remains on a dung

heap. Another was beheaded. Tsar Alexei intervened

on behalf of Morozov, whose life was spared on

the condition that he would leave the government

and Moscow immediately. This arrangement helped

to calm the mob. Morozov was exiled on June 12

to the Kirill-Beloozero Monastery, but he returned

to Moscow on October 26. He never again played

an official role in government, though he was one

of Alexis’s behind-the-scenes advisers throughout

the 1650s.

Morozov’s greed led him to appropriate vast

estates for himself. They totalled over 80,000 desi-

atinas (216,000 acres) with over 55,000 people in

9,100 households; this made him the second

wealthiest Russian of his time. (The wealthiest in-

dividual was Nikita Ivanovich Romanov, Tsar

Mikhail’s uncle, who led the opposition to Moro-

zov’s government.) In 1645 the government, in re-

sponse to a middle service class provincial cavalry

petition, promised that the time limit on the re-

covery of fugitive serfs would be repealed as soon

as a census was taken. The census was taken in

1646–1647, but the statute of limitations was not

repealed. All the while Morozov’s extensive corre-

spondence with his estate stewards reveals that he

was recruiting peasants from other lords and mov-

ing such peasants about (typically from the center

to the Volga region) to conceal them. Morozov was

also active in the potash business: he ordered his

serfs to cut down trees, burn them, and barrel the

ashes for export.

See also: ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH; ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND;

BOYAR; CHANCELLERY SYSTEM; ENSERFMENT; LAW

CODE OF 1649

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crummey, Robert Owen. (1983). Aristocrats and Servi-

tors: The Boyar Elite in Russia, 1613–1689. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

MOROZOV, PAVEL TROFIMOVICH

(c. 1918–1932), young man murdered in 1932

who became a hero for the Pioneers (members of

the Soviet organization for children in the 10 to 14

age group); celebrated in biographies, pamphlets,

textbooks, songs, films, paintings, and plays.

Soviet accounts of the life of Pavel Morozov are

mythic in tone and often contradictory. All agree

that he was born in the western Siberian village of

Gerasimovka, about 150 miles from Sverdlovsk

(Ekaterinburg), probably in December 1918. He and

MOROZOV, PAVEL TROFIMOVICH

963

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

his younger brother Fyodor were murdered on Sep-

tember 3, 1932. The Morozov murders were taken

up by the local press about two weeks after they

happened; in late September 1932, the central chil-

dren’s press became aware of the case, and reporters

were dispatched to Siberia to investigate and to

press for justice against the boys’ supposed mur-

derers. In December 1932, the boys’ grandparents,

their uncle, their cousin, and a neighbor stood trial;

four of the five were sentenced to execution.

Like most child murders, the death of the two

Morozov brothers provoked outrage; equally typ-

ically, press coverage dwelt on the innocence and

goodness of the victims. But since the murders also

took place in an area that was undergoing collec-

tivization, they acquired a specifically Soviet polit-

ical resonance. They were understood as an episode

in the “class war”: A child political activist and

fervent Pioneer had been slaughtered by kulaks,

wealthy peasants, as a punishment for exposing

these kulaks’ activities.

Additionally, it was reported that Pavel (or, as

he became known, “Pavlik”) had displayed such

commitment to the cause that he had denounced

his own father, the chairman of the local collective

farm, for providing dekulakized peasants with false

identity papers. His murder by his relations was an

act of revenge, and an attempt by them to prevent

Pavlik from pushing them into collectivization. All

in all, Pavlik came to exemplify virtue so resolute

that it preferred death to betrayal of principle.

Learning about his life was an important part of

the teaching offered the Pioneers; the anniversaries

of his death were commemorated with pomp, and

statues of Pavlik went up all over the Soviet Union.

But indoctrination did not lead to the emer-

gence of millions of “copycat Pavliks.” Memoirs and

oral history suggest that most children found the

story disturbing, rather than inspiring, even dur-

ing the 1930s. And during the World War II, at-

tention switched to another type of child hero: the

boy or girl who refused to convey information,

even under torture. To the postwar generations,

Pavlik was a nasty little stukach, squealer. Learn-

ing about his life was a chore, and he had far less

appeal than the Komsomol war heroine Zoya Kos-

modemyanskaya. Indeed, surveys indicate that by

2002, the eightieth anniversary of his death, many

respondents either could not remember who Pavlik

was, or remembered his life inaccurately (e.g., “a

hero of the Great Patriotic War”). Statues of him

had disappeared (the Moscow statue in 1991), and

streets had been renamed. Though the Pavlik Mo-

rozov museum in Gerasimovka was still open, few

visitors bothered to call there.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; FOLKLORE; PURGES,

THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Druzhnikov, Iurii. (1997). Informer 001: the Myth of

Pavlik Morozov. (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction

Publishers.

Kelly, Catriona. (2004). Comrade Pavlik: The Life and Leg-

end of a Soviet Boy Hero. London: Granta.

C

ATRIONA

K

ELLY

MOSCOW

Moscow is the capital city of Russia and the coun-

try’s economic and cultural center.

Moscow was founded by Prince Yuri Vladimiro-

vich Dolgoruky in 1147 on the banks of the

Moscow River. Its earliest fortifications were raised

on the present-day site of the Kremlin. Located in

Russia’s forest belt, the city was afforded a limited

degree of protection from marauders from the

south. Its location adjacent several rivers also made

it a good trade center. By 1325, following the sack-

ing of Kiev and the imposition of the Mongol Yoke,

Moscow’s princes obtained the sole right to rule

over the Russian territories and collect tribute for

the Golden Horde. The head of the Russian Ortho-

dox church relocated to Moscow in recognition of

the city’s growing authority. A prince of Moscow,

Ivan III, ultimately rid Russia of Mongol rule, fol-

lowing which the city became the capital of the ex-

panding Muscovite state, which reunited the

Russian lands by diplomacy and military conquest

from the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries.

During the period of expansion, the young

state was thrown into chaos when Ivan IV passed

away without leaving an heir. His unsuccessful ef-

forts to regain access to the Baltic Sea and Black

Sea had left the state further exhausted. In the en-

suing power struggle, the country was invaded by

several foreign armies before the Russian people

were able once again to gain control of Moscow

and elect a new tsar, marking the beginning of the

Romanov dynasty (1613–1917).

In 1713, Peter the Great moved the Russian cap-

ital to St. Petersburg, which he had built on the

Baltic Sea as “Russia’s window to the West.”

MOSCOW

964

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moscow, which Peter loathed for its traditional

Russian ways, remained a major center of com-

merce and culture. Further, all Russian tsars were

crowned in the city, providing a link with the past.

Recognizing the city’s historical importance,

Napoleon occupied Moscow in 1812. He was forced

from the city and defeated by the Russian Army as

foreign invaders before him had been.

The Bolsheviks moved the capital of Russia back

to Moscow when German forces threatened Petro-

grad (previously St. Petersburg) in 1918. When the

Germans left Russian land later that year, the cap-

ital remained in Moscow and has not been moved

since.

During the Soviet era, a metro and many new

construction projects were undertaken in Moscow

as the city grew in population and importance. At

the same time, many cultural sites, particularly

churches, were destroyed. As a consequence, Moscow

lost much of its architectural integrity and ancient

charm. In an effort to recover this, the Russian gov-

ernment has engaged in a number of restoration

projects in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet

Union. One of the most important has been the re-

building of the Savior Cathedral, which was meant

to mark the city’s spiritual revival.

With a population of approximately 8.5 mil-

lion people (swelling to more than 11 million on

workdays), Moscow is the largest city in Russia

and its capital. The Kremlin houses the Presidential

Administration while both chambers of the na-

tional legislature are located just off of Red Square.

The prime minister and his most important

deputies have their offices in the White House, the

building on the banks of the Moscow River that

formerly was the location of the Russian Federa-

tion’s legislature. The various ministries of the gov-

ernment, which report to the prime minister, are

located throughout the city.

The city’s government historically has occupied

a high profile in national politics. This is particu-

larly true of the mayor, who is directly elected by

the city’s residents for a four-year term. The mayor

appoints the Moscow city government and is re-

sponsible for the administration of the city. Among

the city’s administrative responsibilities are man-

aging more than half of the housing occupied by

Muscovites, managing a primary health-care de-

livery system, operating a primary and secondary

school system, providing social services and utility

subsidies, maintaining roads, operating a public

transportation system, and policing the city.

Legislative power lies with the Moscow City

Duma, but the mayor has the power to submit bills

as well as to veto legislation to which he objects.

The city’s citizens elect the City Duma in direct elec-

tions for a four-year term. It comprises thirty-five

members elected from Moscow’s electoral districts.

Not only is Moscow the country’s political cap-

ital, it is also the country’s major intellectual and

cultural center, boasting numerous theaters and

playhouses. Its attractions include the world-

renowned Bolshoi Theater, Moscow State Univer-

sity, the Academy of Sciences, the Tretyakov Art

Gallery, and the Lenin Library. Only St. Petersburg

rivals it architecturally.

Not surprisingly, given its political and cultural

importance, Moscow is Russia’s economic capital

as well, attracting a substantial portion of foreign

investment. The city is the country’s primary busi-

ness center, accounting for 5.7 percent of indus-

trial production. More importantly, it serves as the

home for most of Russia’s export-import industry

as well as a major hub for international and na-

tional trade routes. As a consequence, the standard

of living of Muscovites is well above that of the

rest of the country. All of this owes in large part

to the substantial degree of economic restructuring

that has occurred in the city since 1991 in response

to the introduction of a market economy. There

has been particularly strong growth in finance and

wholesale and retail trade.

The growth of Moscow’s economy has not

come without problems. Muscovites are increas-

ingly concerned about crime as well as the plight

of pensioners and the poor. They are also concerned

about the strain being placed on the city’s trans-

portation system, increasing environmental pollu-

tion caused by the increased use of automobiles,

and the degradation of the city’s infrastructure, in-

cluding its schools and health care system.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; ARCHITECTURE; BOLSHOI

THEATER; KREMLIN; LUZHKOV, YURI MIKHAILOVICH;

MOSCOW ART THEATER; MUSCOVY; ST. PETERSBURG;

YURY VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Colton, Timothy J. (1995). Moscow: Governing the So-

cialist Metropolis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Government of the City of Moscow. (2002). “Informa-

tion Memorandum: City of Moscow.” <http://www.

moscowdebt.ru/eng/city/memorandum>.

T

ERRY

D. C

LARK

MOSCOW

965

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

MOSCOW AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY

A voluntary association chartered in 1819, the

Moscow Agricultural Society was a forum for dis-

cussing agricultural policy. Its membership came

mainly from the serf-owning nobility and included

prominent Slavophiles of the 1850s. In the 1830s

Finance Minister Egor Kankrin provided a small fi-

nancial subsidy, but the society’s main support

came from its members. Its meetings, exhibitions,

and publications were devoted to issues of agricul-

tural innovation, such as new crops and species of

livestock and new methods of crop rotation. Its ear-

liest activities included a model farm (khutor) near

Moscow and an agricultural school. After the end

of serfdom in 1861, the society’s focus turned to

economic and administrative questions: taxation,

the agricultural role of the new zemstvo organs of

local government, the provision of agricultural

credit, the creation of a Ministry of Agriculture. It

cooperated with the Free Economic Society and

other organizations in a multivolume study of

handicraft trades (1879–1887), advocated expan-

sion of grain exports through the construction of

railroad lines and storage facilities, and promoted

the mechanization of agriculture. The Moscow

Agricultural Society corresponded with agricul-

tural societies in other countries, and with local af-

filiates in various parts of Russia. At the beginning

of the twentieth century some of its members ad-

vocated abolition of the peasant commune and the

encouragement of private land ownership and a

market economy. Others helped create the All-

Russian Peasant Union in 1905, and later the mod-

erate League of Agrarian Reform. The organization

was dissolved after 1917, but its library was pre-

served in the Central State Agricultural Library of

the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

See also: AGRICULTURE; FREE ECONOMIC SOCIETY; PEAS-

ANTRY; SLAVOPHILES; ZEMSTVO

R

OBERT

E. J

OHNSON

MOSCOW ART THEATER

Celebrating its centennial anniversary in 1998, The

Moscow Art Theater (MAT) represents a twentieth-

century bastion of theatrical art. MAT insured the

dramatic career of Anton Chekhov, introduced Eu-

ropean trends in stage realism to Russia, and so-

lidified the role of the director as the artistic force

behind dramatic interpretation and the united ef-

forts of designers. MAT also significantly reformed

the procedures by which plays were rehearsed and

set new standards for ensemble acting that ulti-

mately influenced theaters around the world. The

majority of its productions created realistic illusions,

replete with sound effects, architectural details, and

archeologically researched costumes and sets.

Following the 1882 repeal of the 1737 Licensing

Act, which had made Russian theater an imperial

monopoly, playwright Vladimir Nemirovich-

Danchenko (head of Moscow’s acting school, the

Moscow Philharmonic Society) and actor Konstan-

tin Stanislavsky (founder of the renowned theater

club, The Society of Art and Literature) founded

MAT as a shareholding company. Nemirovich in-

stigated their first legendary meeting in 1897. The

enterprise opened in 1898 as The Moscow Publicly

Accessible Art Theater, its name embracing the

founders’ idealistic hopes of providing classic Russ-

ian and foreign plays at prices that the working

class could afford and fostering drama that

educated the community. The first company com-

prised thirty-nine actors—Nemirovich’s most tal-

ented students, notably Olga Knipper, later

Chekhov’s wife; Vsevolod Meyerhold, the future

theatricalist director; and Ivan Moskvin, who still

performed his popular 1898 role of Tsar Fyodor

on his seventieth birthday in 1944—joined with

Stanislavsky’s most successful amateurs, including

his wife Maria Lilina and Maria Andreyeva, the

future Bolshevik and wife to Maxim Gorky.

Within a few seasons, financial difficulties and

lack of governmental funding forced the founders

to raise ticket prices, to drop “Publicly Accessible”

from their name, and reluctantly to accept the pa-

tronage of the wealthy merchant Savva Morozov.

In 1902 Morozov financed the construction of their

permanent theater in the art nouveau style and

equipped it with the latest lighting technology and

a revolving stage.

Following the 1917 revolution, MAT’s realistic

productions attracted support from the liberal

Commissar of Enlightenment, playwright Anatoly

Lunacharsky, and Lenin (who was said to have es-

pecially admired Stanislavsky’s performance as the

fussy Famusov in Alexander Griboyedov’s Woe from

Wit). In 1920, MAT became The Moscow Acade-

mic Art Theater, its new adjective betokening state

support. At this time, Lunacharsky also intervened

on behalf of the destitute Stanislavsky in order to

secure for him and his family a house with two

rooms for rehearsals.

MOSCOW AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY

966

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

During the 1930s, Stanislavsky strenuously

objected to the appointment of Mikhail Geits (1929)

as MAT’s political watchdog and to governmental

pressure to stage productions with insufficient re-

hearsal. Believing in Stalin’s good intentions,

Stanislavsky naively appealed to the Soviet leader,

winning a pyrrhic victory. Stalin placed MAT un-

der direct governmental supervision in 1931,

changing its name to The Gorky Moscow Acade-

mic Art Theater one year later, despite the fact that

none of Maksim Gorky’s plays had been staged

since 1905. Under Stalinism, MAT received special

privileges denied other artists, in return for public

proof of political loyalty. Because of its past dedi-

cation to realism, MAT’s history could easily be

seen as constituting the vanguard of Socialist Re-

alism. Stalin thus turned the company into the sin-

gle most visible model for Soviet theater, and

Stanislavsky’s system of actor training, purged of

its spiritual and symbolist components, into the

sole curriculum for all dramatic schools. Press cam-

paigns ensured this interpretation of MAT’s work,

even as Stanislavsky’s continuing evolution as an

artist threatened the view. Given Stanislavsky’s in-

ternational renown, Stalin could not afford the

public scandal that would result from his arrest.

Instead, Stalin “isolated” Stanislavsky from his

public image, maintaining the ailing old man in his

house, the site of his internal exile (1934–1938).

Nemirovich and Stanislavsky administered the

theater jointly from its inception until 1911 when

Stanislavsky’s experimental stance toward acting

and his growing interest in symbolist plays created

unbearable hostility between them. Thereafter, Ne-

mirovich managed the theater until his death in

1943, and Stanislavsky moved his experiments into

a series of adjunct studios, some of which later be-

came independent theaters. Stanislavsky continued

to act for MAT until a heart attack in 1928, to di-

rect until his death in 1938, and to influence MAT

from the sidelines, as he had in 1931. He adminis-

tered MAT only in Nemirovich’s absence, most no-

tably in 1926 and 1927, when Nemirovich toured

in the United States. Among the theater’s subse-

quent administrators, actor and director Oleg

Yefremov (1927–2000) had the greatest impact on

the company. He had studied with Nemirovich at

the Moscow Art Theater’s school, and founded the

prestigious Sovremennik (Contemporary) Theater

in 1958, and spoke to the conscience of the coun-

try after Stalin’s death. He reinvigorated MAT’s

psychological realism in acting while he relaxed its

history of realistic design. When he took charge of

MAT in 1970, he found an unwieldy company of

more than one hundred actors. In 1987, with per-

estroika (“reconstruction”) occurring in the Soviet

Union, Yefremov decided to reconstruct the com-

pany by splitting MAT in two. Yefremov retained

The Chekhov Art Theater in the 1902 art nouveau

building, and actress Tatyana Doronina took

charge of The Gorky Art Theater. While Yefremov

focused on reviving artistic goals, Doronina made

The Gorky a voice for the nationalists of the 1990s.

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the Art Theater

and all of Russia’s theaters struggled to survive.

Not only did the loss of governmental subsidies cre-

ate extraordinary financial instability, but the tra-

ditional audiences, who looked to theater for

subversive political discussion, deserted theaters for

television news. In 2000, Yefremov’s student, ac-

tor-director Oleg Tabakov, took reluctant charge of

the theater’s uncertain future.

In its first twenty seasons (1898–1917), MAT

revolutionized theatrical art through the produc-

tion of a repertoire of more than seventy plays. The

theater opened in 1898 with two major works:

Alexei Tolstoy’s Tsar Fyodor Ionnovich, which

brought mediaeval Russia vividly to life with arche-

ologically accurate designs, and Chekhov’s The

Seagull, which added psychological realism in act-

ing to illusionistic stage environments. MAT pre-

miered all of Chekhov’s major plays between 1898

and 1904, with Stanislavsky’s staging of The Three

Sisters (1901) hailed as one of the company’s great-

est triumphs. Realistic productions, characterized

by careful detailing in costumes, properties, sets,

and acting choices, predominated. MAT produced

more plays by Henrick Ibsen than by any other

playwright, with An Enemy of the People (1900) pro-

viding Stanislavsky with one of his greatest roles.

Even Ibsen’s abstract play, When We Dead Awaken,

was directed realistically by Nemirovich (1901). For

Gorky’s The Lower Depths (1902) MAT used repre-

sentational detail to create a social statement about

the underclass. Nemirovich especially furthered the

cause of stage realism, often overburdening plays

with inappropriate illusion. His unwieldy realistic

production of William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

(1903) garnered much criticism.

Stanislavsky’s growing interest in abstracted

styles led to MAT’s production of a series of sym-

bolist plays. Notable among these were Stanislav-

sky’s stagings of Leonid Andreyev’s The Life of Man

(1907), which featured stunning stage effects de-

veloped by its director, and Maurice Maeterlinck’s

fantasy, The Blue Bird (1908), as well as Gordon

Craig’s theatricalist production of Shakespeare’s

MOSCOW ART THEATER

967

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Hamlet (1911). 1907 saw the two MAT styles col-

lide uncomfortably when Nemirovich presented his

overly naturalistic version of Ibsen’s Brand along-

side Stanislavsky’s abstracted production of Knut

Hamsun’s The Drama of Life. When Stanislavsky be-

gan to apply his new ideas about acting to Ivan

Turgenev’s A Month in the Country (1909), he uti-

lized abstraction both in the symmetrical set design

and in the actors’ use of static gestures in order to

focus on inner states. This production caused a per-

manent rift between Stanislavsky and the com-

pany.

Although MAT greeted the 1917 revolution op-

timistically, it lost economic viability. Its first

postrevolutionary production was Lord Byron’s

Cain in 1920, interpreted by Stanislavsky as a

metaphor of the postrevolutionary civil war. MAT

struggled to find the necessary funds and materi-

als to realize the production. In order to survive fi-

nancially, half of the company toured Europe and

the United States from 1924 to 1926 with their

most famous realistic productions, among them

Tsar Fyodor Ionnovich from 1898 and Chekhov’s The

Cherry Orchard from 1904. This tour solidified the

international fame of Stanislavsky and MAT. In

the late 1920s, MAT participated in the general

theatrical trend toward a Soviet repertoire.

Stanislavsky staged Mikhail Bulgakov’s controver-

sial view of White Russia in The Days of the Turbins

(1926) and Vsevolod Ivanov’s Armored Train 14-69

(1927). During the 1930s and 1940s, under the

yoke of Socialist Realism, MAT’s work lost its

verve, its productions becoming undistinguished.

In the 1970s, Yefremov reinvigorated the company

by employing talented actors and revived its reper-

toire by staging new plays, such as Mikhail

Roshchin’s portrait of young love in Valentin and

Valentina (1971) and Alexander Vampilov’s Duck

Hunting (1979), in which Yefremov played the

fallen hero.

See also: CHEKHOV, ANTON PAVLOVICH; MEYERHOLD,

VSEVOLOD YEMILIEVICH; MOSCOW; SILVER AGE;

SOCIALIST REALISM; STANISLAVSKY, KONSTANTIN

SERGEYEVICH; THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benedetti, Jean. (1988). Stanislavsky [sic]: A Biography.

New York: Routledge.

Carnicke, Sharon Marie. (1998). Stanislavsky in Focus.

London: Harwood/Routledge.

Leach, Robert and Borovsky, Victor. (1999). A History of

Russian Theatre. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Rich, Elizabeth. (2000). “Oleg Yefremov, 1927–2000: A

Final Tribute.” Slavic and East European Performance

20(3):17–23.

Worrall, Nick. (1996). The Moscow Art Theatre. New York:

Routledge.

S

HARON

M

ARIE

C

ARNICKE

MOSCOW BAROQUE

Moscow Baroque was the fashionable architectural

style of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth

centuries, combining Muscovite (Russo-Byzantine)

traditions with Western decorative details and pro-

portions; the term also sometimes applied to new

trends in late seventeenth-century Muscovite paint-

ing, engraving, and literature.

The term Moscow Baroque (moskovskoe barokko)

came into use among Russian art historians in the

1890s and 1900s as a way of categorizing the dis-

tinctive style of architecture which flourished in

and around Moscow from the late 1670s, and in

the provinces into the 1700s. In the 1690s, Peter

I’s maternal relatives the Naryshkins commissioned

many sumptuous churches in the style; hence the

supplementary art historical term “Naryshkin

Baroque,” which is sometimes erroneously applied

as a general term for the style. Some of the early

examples of Moscow Baroque are reminiscent of

mid-seventeenth-century Muscovite churches in

their general shape and coloration—cubes con-

structed in red brick with white stone decorations

and topped with one or five domes—but the

builders had evidently assimilated a new sense of

symmetry and regularity in their ordering of both

structural and decorative elements. Old Russian or-

namental details were replaced almost entirely by

Western ones based on the Classical order system:

half-columns with pediments and bases, window

surrounds of broken pediments, volutes, carved

columns, and shell gable motifs. One of the best

concentrations of Moscow Baroque buildings was

commissioned by the regent Sophia Alexeyevna in

the 1680s in the sixteenth-century Novodevichy

Convent in Moscow, which includes the churches

of the Transfiguration, Dormition, and Assump-

tion, with a refectory, belltower, nuns’ cells, and

crenelations on the convent walls in matching ma-

terials and style. Similar constructs can be found

in the Monastery of St. Peter (Vysokopetrovsky)

on Petrovka Street in Moscow. Civic buildings were

constructed on the same principles: for example,

MOSCOW BAROQUE

968

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Prince Vasily Golitsyn’s Moscow mansion (1680s)

and the Pharmacy on Red Square (1690s). A num-

ber of these projects were carried out by the archi-

tectural section of the Foreign Office.

In the 1690s builders regularly incorporated

octagonal structures, producing the so-called

octagon-on-cube church. One of the finest exam-

ples, the Intercession at Fili, built for Peter’s uncle

Lev Naryshkin in 1690–1693, with its soaring

tower of receding octagons, gold cupolas, and in-

tricately carved limestone decoration, bears witness

to both the Naryshkins’ wealth and their West-

ernized tastes. Inside, all the icons were painted in

a matching “Italianate” style and set in an elabo-

rately carved and gilded iconostasis. This and other

churches such as the Trinity at Troitse-Lykovo,

Boris and Gleb in Ziuzino, and Savior at Ubory,

with their tiers of receding octagons, also owe

something to distant prototypes in Russian and

Ukrainian architecture (the wooden architecture of

the former and the dome configuration of the lat-

ter), while the new sense of harmony in their de-

sign and planning evokes the Renaissance. The style

spread beyond Moscow.

Analogous developments can be seen in alle-

gorical prints of the period, embellished with a

characteristic Baroque mix of Christian and Classi-

cal imagery, most of which originated in Ukraine.

A characteristic example is Ivan Shchirsky’s en-

graving (1683) of Tsars Ivan and Peter hovering

above a canopy containing a double eagle, with

Christ floating between them and, above Christ, a

winged maiden, the Divine Wisdom (Sophia). In

icons painted in the Moscow Armory and in work-

shops in Yaroslavl, Vologda, and other major com-

mercial centers, influences from Western art can be

seen in the use of light and shade and decorative

details such as scrolls, putti-like angels, ornate

swirling cloud and rock motifs, dramatic gestures,

and even some borrowings from Catholic iconog-

raphy: for instance, saints with emblems of their

martyrdom; blood dripping from Christ’s hands

and side. In poetry, syllabic verse and Baroque mo-

tifs and devices were imported from Poland and

practiced by such writers as Simeon Polotsky, court

poet to Tsar Alexis, and Polotsky’s pupil Silvester

Medvedev.

Art historians have debated whether Moscow

Baroque was a direct derivative of Western

Baroque, represented a spontaneously generated

and original form of baroque, or was the deca-

dent, over-ornate last phase of the “classical”

forms of Russo-Byzantine art. It may be best to

view it as an example of the belated influence of

the Renaissance upon traditional art and architec-

ture, which picked up elements from both con-

temporary and slightly earlier Western art. No

Russian architects are known to have visited the

West during this period, and there is scant evi-

dence of Western architects working in Russia.

However, Russian craftsmen did have access to

foreign books and prints in the Armory, Foreign

Office workshops, and other libraries, while con-

tacts with Polish culture, both direct and via

Ukraine and Belarus, were influential, especially

in literature.

The term Moscow Baroque is not generally ap-

plied to the architecture of early St. Petersburg, al-

though many buildings constructed in the reigns

of Peter I and his immediate successors had much

in common with the preceding style: for instance,

the use of octagonal structures and the white dec-

orative details against a darker background. In

Moscow and the provinces, Moscow Baroque re-

mained popular well into the eighteenth century.

See also: ARCHITECTURE; GOLITSYN, VASILY VASILIEVICH;

MEDVEDEV, SYLVESTER AGAFONIKOVICH; POLOTSKY,

SIMEON; SOPHIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cracraft, James. (1990). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cracraft, James. (1997). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Imagery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1977). “Western European Graphic

Material as a Source for Moscow Baroque Architec-

ture.” Slavonic and East European Review 55:433–443.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1982). “Moscow Baroque: A Contro-

versial Style.” Transactions of the Association of

Russian-American Scholars in USA 15:69–93.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

MOSCOW, BATTLE OF

The Battle of Moscow was a pivotal moment in the

early period of the World War II, in which Soviet

forces averted a disastrous collapse and demon-

strated that the German army was, in fact, vul-

nerable. The battle can be divided into three general

segments: the first German offensive, from Sep-

tember 30 to October 30, 1941; the second German

offensive, from November 16 to December 5, 1941;

MOSCOW, BATTLE OF

969

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and the Soviet counteroffensive, from December 5,

1941, to April 5, 1942.

The German attack on Moscow began on Sep-

tember 30, 1941, under the code name “Typhoon.”

The German High Command hoped to seize the So-

viet capital before the onset of winter, surmising

that the fall of Moscow would presage the fall of

the Soviet Union. With this goal in mind they

arrayed a massive force against the Soviet capital,

concentrating 1,800,000 troops, 1,700 tanks,

14,000 cannons and mortars, and 1,390 aircraft

against Moscow. Led by General Heinz Guderain,

this enormous army quickly took advantage of the

weakened and retreating Soviet forces to capture

several towns on the approaches to the capital in

the first week of the campaign. By October 15, the

German army, having circumvented the Soviet de-

fensive lines and taken the key towns of Kaluga

and Mozhaisk, was within striking distance of the

capital.

The lightning speed with which the Germans

reached the outskirts of the capital spawned a panic

in Moscow as many Muscovites, fearing a German

takeover of the city, began to flee to the east. For

several days, local authority crumbled completely,

and Moscow seemed on the verge of chaos. Even

as the capital teetered on the edge of collapse, how-

ever, several factors combined to slow the German

onslaught. First, the German forces had begun to

outpace their supply lines. Second, Josef V. Stalin

and the Soviet High Command appointed General

Georgy Zhukov as the commander of the Western

Front. Fresh from his triumph stabilizing the

defensive lines surrounding Leningrad, Zhukov

moved to do the same for Moscow, and the Red

Army began to stiffen its defense of the capital.

Third, the German supply line problems gave the

Red Army time to bring reserves from the Far East

to Moscow. Until these reserves could be put in

place, however, the city’s defense leaders ordered

ordinary Muscovites organized into opolchenie, or

home guard units, into the breaches in the capital’s

defensive lines. These units, often quickly and poorly

trained, paid a high price to shore up Moscow’s de-

fenses.

Once the German supply had regrouped, Ger-

man forces mounted another attack in late No-

vember. Initially the German forces scored several

successes in the areas of Klin and Istra to the

northwest and around Tula to the south. The

tenacity of the Soviet defense and severity of the

Russian winter, however, slowed the German ad-

vance and allowed time for Soviet forces to recover

and even begin to mount limited counterattacks by

early December.

Emboldened by their success in stemming the

German onslaught, the Soviet command attempted

a more concerted attack against the German in-

vaders on December 5–6, 1941. With the aim of

driving the Germans back to Smolensk, Stalin and

Zhukov opened a 560-mile front stretching from

Kalinin, north of the capital, to Yelets in the south.

The ambitious operation quickly met with success

as the Red Army, bolstered by units from Central

Asia, drove the Germans back twenty to forty

miles, liberating Kalinin, Klin, Istra, and Yelets and

breaking the German encirclement attempt at Tula.

In many places German forces retreated quickly,

weakened by their supply problems and their ex-

posure to the Russian winter. Soviet forces, despite

their advances, could never capitalize on their ini-

tiative. While the Red Army advanced as much as

200 miles into German-held territory on the Ger-

man flanks to the north and south of Moscow,

they had great difficulty dislodging German forces

from the Rzhev-Gzhatsk-Viazma salient due west

of the capital. By late January their resistance had

stiffened to the point that the Red Army’s advance

began to stall. Although the Soviet offensive con-

tinued to grind its way westward, it had lost mo-

mentum. This stalemate continued until April 1942

when the Soviet command called a halt to the of-

fensive. It was not until the spring of 1943 that

the Red Army finally drove the Germans back from

Moscow.

The Battle of Moscow was important for sev-

eral reasons. It was the first real setback that Ger-

man forces had absorbed since World War II began

in 1939. Despite the fact that Moscow was on the

verge of collapse in mid-October 1941, Soviet forces

proved that the German army was not invincible.

Also, the struggle for the Soviet capital revealed a

new breed of Soviet commanders who came to

prominence in the defense of the capital. Comman-

ders such as Zhukov, Konstantin Rokossovsky,

Ivan Boldin, and Dmitry Lelyshenko demonstrated

their competence during this critical period and be-

came the backbone of the Soviet military command

for the remainder of the war. Finally, the defense

of the capital was an important moral victory for

the Soviet command and people alike, and made an

indelible impression on the Soviet nation and on the

other countries participating in World War II.

See also: MOSCOW; WORLD WAR II; ZHUKOV, GEORGY

KONSTANTINOVICH

MOSCOW, BATTLE OF

970

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, John. (1999). The Road to Stalingrad: Stalin’s

War with Germany. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

Overy, Richard. (1998). Russia’s War: A History of the So-

viet War Effort, 1941–1945. New York: Penguin.

Werth, Alexander. (1964). Russia at War, 1941–1945.

New York: Avon Books.

A

NTHONY

Y

OUNG

MOSCOW OLYMPICS OF 1980

The city of Moscow hosted the Summer Olympic

Games from July 19 to August 3, 1980. The In-

ternational Olympic Committee awarded Moscow

the games in 1974, in the hopes that international

competition might contribute to détente. But su-

perpower politics had a direct impact on these

games. Under the leadership of the United States,

sixty-two nations boycotted the Moscow Olympics

to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan dur-

ing December of 1979. The Soviet government,

along with its allies, retaliated by boycotting the

1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympic Games. Great

Britain, France, and Italy supported the condem-

nation of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, but

participated in the games.

The Moscow Olympic games were the first

held in a socialist country. Soviet leader Leonid

Brezhnev, visibly aged, opened the games. The So-

viet leadership intended to use the games to show-

case the advantages of the socialist system. Toward

that end the government ordered that the Moscow

streets and parks be cleaned and that petty crimi-

nals and prostitutes be rounded up. Government

officials also hoped that Soviet athletes would dom-

inate the games. They were not disappointed. The

USSR won 195 medals, including 80 gold; the Ger-

man Democratic Republic (East Germany) won 126

medals, including 47 gold; followed by Bulgaria,

Hungary, Poland, and Cuba in that order. Eighty–

one nations had participated in the Moscow games,

and the USSR and its East European and other so-

cialist allies won the vast majority of the medals.

Soviet fans demonstrated poor sportsmanship by

constantly jeering Polish and East German com-

petitors. Since 1952, when the USSR first partici-

pated in the Olympic games, government officials

recognized how gold, silver, and bronze medals

might be translated into propaganda achievements

for the nation.

Some of the notable individual achievements of

the games included gymnast Nadia Comaneci of

Romania winning two medals; Soviet swimmer

Vladimir Salnikov becoming the first to break fif-

teen minutes in the 1,500 meters; Teofilo Steven-

son, a Cuban boxer, becoming the first boxer to

win three gold medals in his division; Soviet gym-

nast Alexander Dityatin winning eight medals;

Miruts Yifter of Ethiopia winning the 5,000- and

10,000-meter runs in track; and Britain’s Sebast-

ian Coe outkicking countryman Steve Ovett in the

1,500 run. At the closing ceremony, it was said

that the mascot of the Moscow Olympics, Misha

the Bear, had a tear in his eye.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH; SPORTS POLICY;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

MOSCOW OLYMPICS OF 1980

971

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

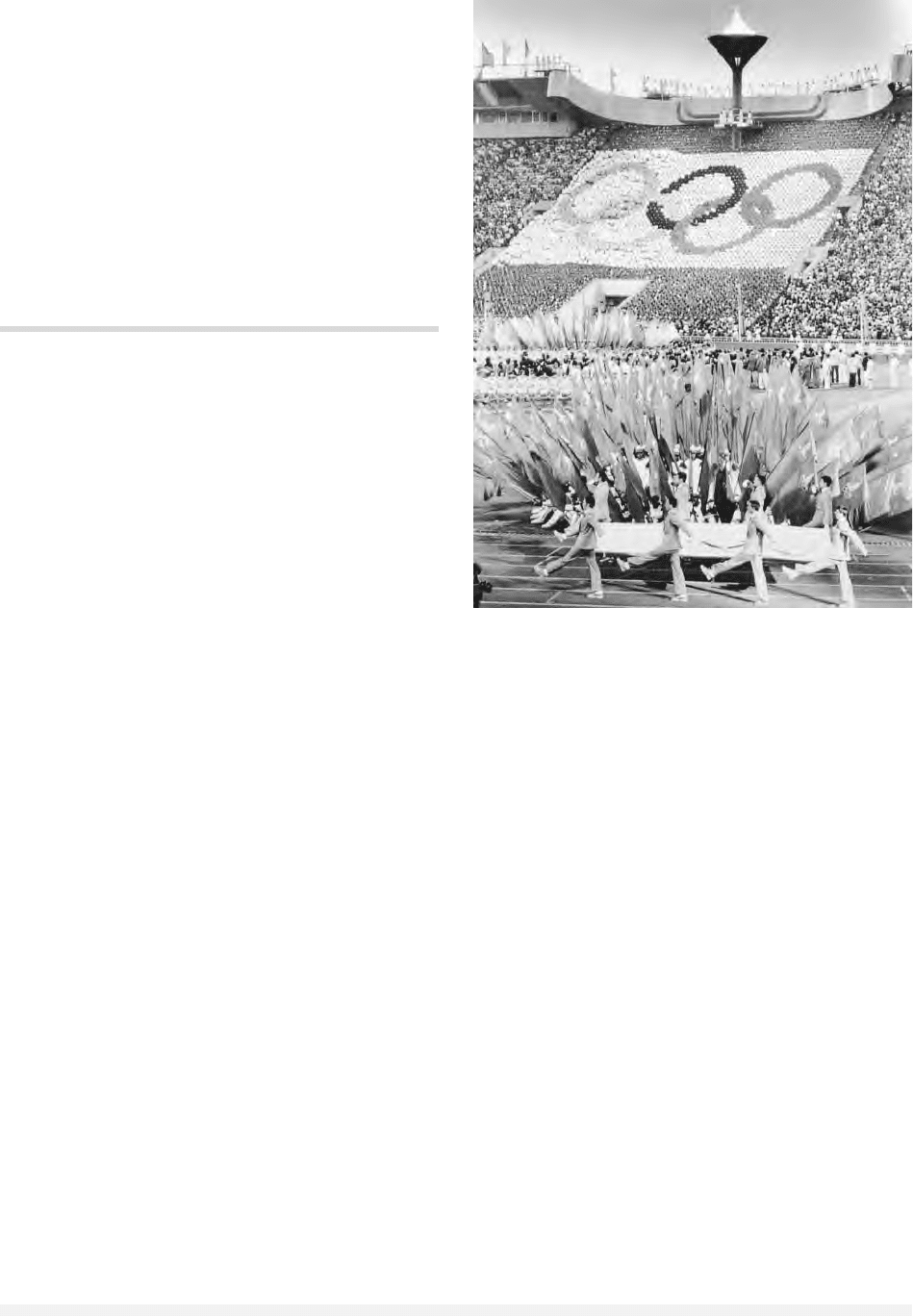

The Olympic flag is carried out of the Lenin Stadium at the

closing ceremony of the 1980 summer Olympic Games.

© B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hulme, Derick L. (1990). The Political Olympics: Moscow,

Afghanistan, and the 1980 U.S. Boycott. New York:

Praeger.

P

AUL

R. J

OSEPHSON

MOSKVITIN, IVAN YURIEVICH

Seventeenth-century Cossack and explorer of Rus-

sia’s Pacific coast.

The Cossack adventurer Ivan Yurievich Mosk-

vitin was one of the many explorers and fron-

tiersmen who took part in the great push eastward

that transformed Siberia during the reigns of tsars

Mikhail (1613–1645) and Alexei (1645–1676).

In 1639 Moskvitin left Yakutsk at the head of

a squadron of twenty Cossacks, seeking to confirm

the existence of what local natives called the

“great sea-ocean.” Proceeding east, then south-

ward, Moskvitin encountered the mountains of the

Jug-Jur Range, which forms a barrier separating

the Siberian interior from the Pacific coastline.

Moskvitin threaded his way through the moun-

tains by following the Maya, Yudoma, and Ulya

river basins.

Tracing the Ulya to its mouth brought

Moskvitin to the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk. He

and his men were therefore the first Russians to

reach the Pacific Ocean by land. The party also built

a fortress at the mouth of the Ulya, Russia’s first

Pacific outpost. Until 1641, Moskvitin charted much

of the Okhotsk shoreline. Mapping an overland

route to the eastern coast and establishing a pres-

ence there were key moments in Russia’s expan-

sion into Siberia and Asia.

See also: EXPLORATION; SIBERIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bobrick, Benson. (1992). East of the Sun: The Epic Conquest

and Tragic History of Siberia. New York: Poseidon.

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1993). Conquest of a Continent: Siberia

and the Russians. New York: Random House.

J

OHN

M

C

C

ANNON

MOTION PICTURES

The statement “Cinema is for us the most impor-

tant of all arts” has been attributed to Vladimir

Lenin. This statement, whether apocryphal or not,

became the motto of the Soviet motion picture in-

dustry. Because of the central part the movies

played in Soviet propaganda, the motion picture in-

dustry had an enormous impact on culture, soci-

ety, and politics.

EARLY RUSSIAN CINEMA, 1896–1918

The moving picture age began in Russia on May 6,

1896, at the Aquarium amusement park in St. Pe-

tersburg. By summer of that year, the novelty was

a featured attraction at the popular provincial trad-

ing fairs. Until 1908, however, the vast majority of

movies shown in Russia were French. That year,

Alexander Drankov (1880–1945), a portrait pho-

tographer and entrepreneur, opened the first Russ-

ian owned and operated studio, in St. Petersburg.

His inaugural picture, Stenka Razin, was a great suc-

cess and inspired other Russians to open studios.

By 1913, Drankov had been overshadowed by

two Russian-owned production companies, Khan-

zhonkov and Thiemann & Reinhardt. These were

located in Moscow, the empire’s Hollywood. The

outbreak of war in 1914 proved an enormous boon

to the fledgling Russian film industry, since distri-

bution paths were cut, making popular French

movies hard to come by. (German films were for-

bidden altogether.) By 1916 Russia boasted more

than one hundred studios that produced five hun-

dred pictures. The country’s four thousand movie

theaters entertained an estimated 2 million specta-

tors daily.

Until 1913 most Russian films were newsreels

and travelogues. The few fiction films were mainly

adaptations of literary classics, with some histori-

cal costume dramas. The turning point in the de-

velopment of early Russian cinema was The Keys to

Happiness (1913), directed by Yakov Protazanov

(1881–1945) and Vladimir Gardin (1881–1945) for

the Thiemann & Reinhardt studio. This full-length

melodrama, based on a popular novel, was the leg-

endary blockbuster of the time.

Although adaptations of literary classics re-

mained popular with Russian audiences, the con-

temporary melodrama was favored during the war

years. The master of the genre was Yevgeny Bauer

(1865–1917). Bauer’s complex psychological por-

traits, technical innovations, and painterly cine-

matic style raised Russian cinema to new levels of

artistry. Bauer worked particularly well with ac-

tresses and made Vera Kholodnaya (1893–1919) a

legend. Bauer’s surviving films—which include

MOSKVITIN, IVAN YURIEVICH

972

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY