Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SAINTS

In addition to the saints inherited from the Early

Church and Byzantium, the Orthodox Church in

Rus soon began to create its own objects of vener-

ation. The saints belonged to three main categories:

(1) spiritual and secular leaders who rendered sig-

nificant service to the Church; (2) martyrs; and (3)

those who exhibited extraordinary spiritual gifts,

specifically the power to perform miracles, espe-

cially through their relics. Although the miracles

were not a formal precondition under canon law,

popular Orthodoxy placed a high value on this

quality, primarily if manifested in “uncorrupted re-

mains” (netlennye moshchi). The miracle of physical

preservation, attested by an official examination of

the crypt, reinforced belief in the power to perform

miracles and hence intercede on behalf of the dis-

abled and distressed.

Canonizations in the Russian Orthodox Church

have proceeded in a highly uneven fashion. In early

medieval Russia (from Christianization in 988 to

the 1547 Church Council), the Russian Church can-

onized only nineteen figures; the first to be so hon-

ored were the princes Boris and Gleb, whose

nonresistance to a violent death amidst the fratri-

cidal warfare made them the very model of kenoti-

cism. The first major burst of canonizations came

during the Church Councils of 1547 and 1549,

which, reflecting Muscovy’s new self-assertion as

the Third Rome, recognized thirty-nine new saints.

Subsequently the church slowly expanded the

number of saints, but that process came to a vir-

tual halt in 1721: It canonized only five new saints

before Nicholas II ascended the throne in 1894 and

sought to bolster autocracy by favoring canoniza-

tion and emphasizing the religious foundations of

autocracy. The Bolshevik Revolution brought all of

that to an end; the new regime actively engaged in

de-canonization, opening scores of saints’ crypts

(to demonstrate that the “uncorrupted relics” were

frauds) and consigning relics to museums and stor-

age. Although the Church was able to canonize five

saints in the 1960s and 1970s, an era of large-scale

canonizations opened in 1988. Over the next decade

the church canonized a long list of prominent me-

dieval figures (i.e., Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy

and the icon-painter Andrei Rublev) as well as

many martyred during the Soviet era.

By 1999 the Russian Orthodox Church had a

total of 1,362 saints. The majority came from the

hierarchy (11.5%) and monastic orders (49.9%); few

of the parish clergy were canonized (1.8%), all,

S

1343

indeed, on the basis of marytyrdom. In addition to

a substantial number of princes and tsars (6.9%),

the church canonized ordinary lay martyrs (24.5%),

some “fools-in-Christ” (3.2%), and laypersons ven-

erated for their extraordinary spirituality (2.3%).

These saints are, moreover, overwhelmingly male

(96.4%). Since 1999, the church has begun to

change these proportions, chiefly because of the on-

going canonization of martyrs (e.g., more than a

thousand in August 2000). While some decisions

have been exceedingly controversial (above all, the

canonization of Nicholas II and his family), the

church seeks to pay homage to the ordinary priests

and parishioners who paid the ultimate price for

their unswerving faith during the merciless repres-

sions of the first decades of Soviet rule.

See also: HAGIOGRAPHY; ORTHODOXY; RELIGION; RUSSIAN

ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freeze, Gregory. (1996). “Subversive Piety: Religion and

the Political Crisis in Late Imperial Russia.” Journal

of Modern History 68:308–50.

Grunwald, Constantin de. (1960). Saints of Russia. Lon-

don: Hutchinson.

G

REGORY

L. F

REEZE

SAKHA AND YAKUTS

The famous folklore scholar G. V. Ksenofontov has

compared the once nomadic Sakha people to a

branch of an apple tree carried around the world

by the wind and finally taking root. The Sakha, or

Yakut, people are the descendants of Turkic nomads

and originated in the region around Lake Baikal in

what is now Russia. But in the thirteenth and four-

teenth centuries Mongols arrived from the south,

along with other peoples, and the Sakha moved

north and east, settling eventually in the basin of

the river Lena, later called Yakutia.

In the early twenty-first century, Yakutia or

the Republic of Sakha is an autonomous republic

within Russia in the far northeast, five times the

size of France. Known as the “Land of Soft Gold”

for the rich furs that come from the region, Yaku-

tia is home to the Sakha people, as well as four

other indigenous cultural groups (the Even, the

Evenki, the Yukagir, and the Chukchi). The name

“Yakut” comes from the Evenk word yako, mean-

ing stranger. The Russians arriving in the seven-

teenth century adopted the Evenk word for the lo-

cal population. The capitol of the Republic of Sakha

is Yakutsk, its largest city.

Russians sent to gather fur and other riches for

the tsar, made Yakutia a stopping point on their

way to the Pacific Ocean during the eighteenth cen-

tury. They brought new agricultural techniques to

the Sakha, who were primarily cattle and horse

breeders, but the local population paid a price in

fur tax for these innovations.

In 1923 Soviet power was established in

Yakutsk. It was declared an autonomous republic

under the name of Yakutia, but was still econom-

ically and politically controlled by the Soviet Union.

It received its official name (Republic of Sakha)

when the Declaration of Sovereignty of the Repub-

lic of Sakha (Yakutia) was signed on September 27,

1990. The Republic of Sakha has a president, elected

for a term of five years.

SAKHA AND YAKUTS

1344

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

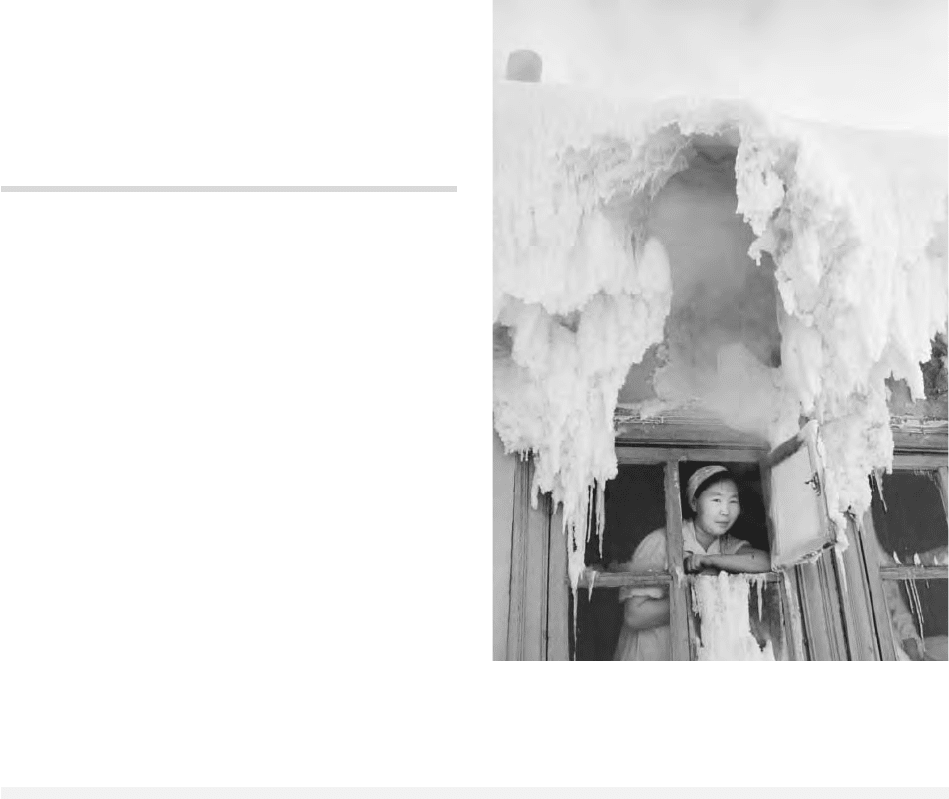

A Yakut cook peers out from a restaurant window encased in

frozen snow. © D

EAN

C

ONGER

/CORBIS

Always a resource-rich region, Yakutia plays a

large role in Russia’s economy. The main industry

in the republic is mining. The Republic of Sakha

produces 99 percent of Russia’s diamonds, 24 per-

cent of its gold, and 33 percent of its silver. It is

also a major producer of coal, natural gas, tin, tim-

ber, fish, and other natural resources. The diamond

mining industry is the main source of Russia’s for-

eign currency income; the multinational De Beers

company partnership with the Russian company

Almazy Rossii-Sakha (Diamonds of Russia and

Sakha) was established in 1992.

The Sakha summer festival, Ysyakh, is held in

June, celebrating the ancestors’ movement of their

cattle to pasture in the steppe. The festival opens

with the solemn ritual of feeding the fire and in-

cludes sport contests and horse races, as well as

kumys, a traditional beverage made of fermented

mare’s milk.

Since 1991, the Sakha language has been a

mandatory class in primary schools, and some 92

percent of ethnically Sakha people speak their own

language. It is not considered to be an endangered

language, unlike the Chukchi, Even, or Evenki lan-

guages. The some 400,000 Sakha people living and

working in the Republic of Sakha take pride in their

strong and unique heritage.

See also: CHUKCHI; EVENKI; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SO-

VIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Argounova, Tatiana. (2000). “Republic of Sakha (Yaku-

tia).” <http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/resources/rfn/

sakha.html>.

Hiller, Kristin. (1997). “Big River of Siberia.” Russian Life

9:16–24.

Slezkine, Yuri. (1994). Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small

Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Vitebsky, P. (1990). “Yakut.” In The Nationalities Ques-

tion in the Soviet Union, ed. Graham Smith. London:

Longman.

E

RIN

K. C

ROUCH

SAKHAROV, ANDREI DMITRIEVICH

(1921–1989), physicist, political dissident, and mem-

ber of the Council of People’s Deputies; recipient of

the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Andrei Sakharov was born into an intelligentsia

family in Moscow in 1921. Following in the foot-

steps of his physicist father, he enrolled at the

physics faculty of Moscow University in 1938. Ex-

empted from military service in World War II,

Sakharov graduated in 1942 and spent the war

years as an engineer at a munitions factory. There

he met and married Klavdia Vikhireva (1919–1969),

a laboratory technician.

After the war Sakharov undertook graduate

work in the laboratory of Igor Tamm. He received

his candidate’s degree (roughly equivalent to a

Ph.D.) in 1947. In the late 1940s, Sakharov con-

ducted research that led to the explosion of the So-

viet hydrogen bomb in 1953. The same year, he

was elected a full member of Academy of Sciences.

At thirty-two, he was the youngest member in the

history of that institution.

Sakharov began to support victims of political

oppression as early as 1951 when he sheltered a

Jewish mathematician fired from the Soviet

weapons program. In 1958 he published two papers

on the effects of nuclear explosions and appealed for

a ban on atmospheric testing. With this work he be-

gan to move beyond physics into political activism.

The 1968 publication in the New York Times of

Sakharov’s essay “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful

Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom” marked, he

wrote in his memoirs, a “decisive step” in his de-

velopment as a dissident. The essay called for dis-

armament and rapprochement with the West. As

a result of the essay, Sakharov was banned from

all weapons research. His wife died shortly there-

after, and Sakharov returned to Moscow and aca-

demic physics.

Sakharov became involved in the emerging

human rights movement, cofounding the Moscow

Human Rights Committee in 1970. Through arti-

cles, petitions, interviews, and demonstrations,

Sakharov and others in the movement aided polit-

ical prisoners and advocated the abolition of

censorship, an independent judiciary, and the in-

troduction of contested elections. Sakharov married

fellow human rights activist Yelena Bonner in

1972. She represented him at the Nobel Prize cer-

emony in 1975. The Nobel Committee’s citation

emphasized Sakharov’s linkage of human rights

and international cooperation.

Sakharov’s denunciation of the Soviet invasion

of Afghanistan in December 1979 led to his exile

to Gorky in January 1980. He maintained ties with

SAKHAROV, ANDREI DMITRIEVICH

1345

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moscow and the West via Bonner until her exile in

1984.

In 1986 Mikhail Gorbachev invited Sakharov to

return to Moscow. Sakharov immediately became

an important and ubiquitous figure in the democ-

ratization movement. He was elected to the Con-

gress of People’s Deputies in 1989. He participated

in drafting a new constitution. He lent his personal

support to numerous causes, advocating amnesty

for political prisoners, disarmament, peaceful solu-

tions to ethnic conflicts, and limits on Gorbachev’s

emergency powers. On the eve of his death in De-

cember 1989, he was working to abolish Article 6

of the Soviet constitution, which enshrined the

Communist Party’s monopoly on power. The arti-

cle was abolished in March 1990.

See also: BONNER, YELENA GEORGIEVNA; CONGRESS OF

PEOPLE’S DEPUTIES; DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; GLAS-

NOST; HUMAN RIGHTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bonner, Elena. (1986). Alone Together, tr. Alexander Cook.

New York: Knopf.

Lourie, Richard. (2002). Sakharov: A Biography. Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England.

Sakharov, Andrei. (1989). Moscow and Beyond, 1986 to

1989, tr. Antonina Bouis. New York: Vintage Books.

Sakharov, Andrei. (1990). Memoirs, tr. Richard Lourie.

New York: Knopf.

L

ISA

A. K

IRSCHENBAUM

SALT See STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION TREATIES.

SALTYKOV-SHCHEDRIN LIBRARY See NATIONAL

LIBRARY OF RUSSIA.

SALTYKOV-SHCHEDRIN,

MIKHAIL YEVGRAFOVICH

(1826–1889), one of Russia’s greatest satirists.

Writing for leading radical journals of his time,

Sovremennik (The Contemporary) (1862–1865) and

Otechestvennye zapiski (Notes of the Fatherland)

(1868–1889), Saltykov (pen name Shchedrin) cre-

ated the most biting satires in Russian literature.

Among his best-known books are Istoriia

odnogo goroda (History of a Town) (1869–1870) and

Gospoda Golovlevy (The Golovlyov Family) (1875—

1880). History is an account of despotic mayors’

rule of a fictitious town Glupov (Foolsville). The

mayors can be distinguished from each other only

by the degree of their incompetence and ill will. The

book is a satire on the whole institution of Russian

statehood and the very spirit that pervades the

Russian way of life: routine mismanagement, need-

less oppression, and pointless tyranny. At the same

time, it is an attack on the Russian people for their

passivity toward their own fate, for their accep-

tance of violence and oppression of their rulers.

The Golovlyov Family is a study of the institu-

tion of the family as cornerstone of society. In this

novel, Saltykov describes moral and physical

decline of three generations of a Russian gentry

family. The nickname of the novel’s protagonist,

Iudushka (“Little Judas”), whose treacherous be-

havior toward his nearest family is a matter of

daily business, became part of Russian speech.

Among Saltykov’s other better-known works

are Pompadur i pompadurshi (Pompadours and Pom-

padouresses) (1863–1874), Sovremennaia idilliia

SALT

1346

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

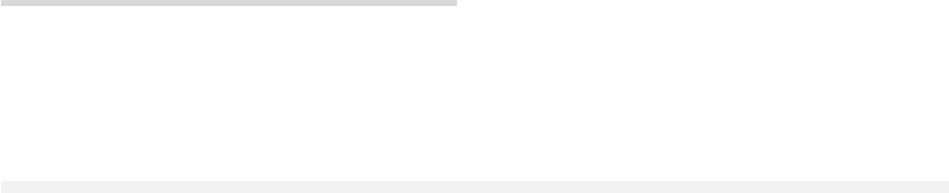

Andrei Dimitrievich Sakharov. AP/W

IDE

W

ORLD

P

HOTOS

.

R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

(Contemporary Idyll) (1877–1883), and Skazki (Fairy

Tales) (1869–1886).

See also: INTELLIGENTSIA; JOURNALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Draitser, Emil. (1994). Techniques of Satire: The Case of

Saltykov-Shchedrin. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Saltykov-Shchedrin, M. E. (1977). The Golovlyov Family.

Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Saltykov-Shchedrin, M. E. (1984). The Pompadours. Ann

Arbor, MI: Ardis.

E

MIL

D

RAITSER

SAMI

The fifty- to eighty thousand Sami (Lapps) live

mostly in northern Norway and Sweden, some in

Finland, and only about 3 percent (1,600) in the

Kola peninsula of the Russian Federation. They rep-

resent less than 0.2 percent of the Murmansk oblast

population. They reached the Gulf of Bothnia

around 1300. Sami and Finnic languages are not

mutually intelligible, having split some three thou-

sand years ago. Three to ten Sami languages are

distinguished, and the standard literary Sami in the

Nordic countries is difficult to understand for the

Kola (Kild) Sami, who are also unfamiliar with its

Latin script. The reputed Asian features are actu-

ally encountered in only 25 percent of the Sami

population.

Inhabiting most of present Finland and Karelia

one thousand years ago, the Sami were pushed to-

ward the Arctic Ocean by Scandinavian, Finnish,

Russian, and Karelian booty seekers. Those in the

west were forced to adopt Catholicism and later

Lutheranism. Greek Orthodoxy was imposed on the

Kola Samis in the early 1500s, after they were sub-

jected by Novgorod around 1300. The first west-

ern Sami book was printed in 1619, and the Bible

in 1811, while the first Kola Sami book appeared

in 1878.

Reindeer herding remains a major occupation.

The Soviet Russian authorities annihilated the tra-

ditional Kola Sami settlements in the 1930s, relo-

cating them repeatedly to ever larger state or

collective farms, where overgrazing severely re-

duced the number of reindeer. By now Lujaur

(Lovozero in Russian) in central Kola remains the

only partly Sami district. In 1937 Moscow ordered

all Sami publications destroyed. Ten years before

the collapse of the Soviet Union, Sami became again

an optional subject in Lujaur schools, and some ba-

sic texts were published. A Kola Sami association

was formed in 1989 and later joined the worldwide

Sami Council.

See also: FINNS AND KARELIANS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; NORTHERN

PEOPLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beach, Hugh. (1994). “The Sami of Lapland.” In Polar Peo-

ples: Self-Determination and Development, ed. Minority

Rights Group. London: Minority Rights Publications.

Slezkine, Yuri. (1994). Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small

Peoples of the North. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Taagepera, Rein. (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the

Russian State. London: Hurst.

R

EIN

T

AAGEPERA

SAMIZDAT

The term samizdat is most often translated as “self-

publishing.” It refers to the clandestine practice in

the Soviet Union of circulating manuscripts that

were banned, had no chance of being published in

normal channels, or were politically suspect. These

were generally typescripts, mimeograph copies, or

handwritten items.

The practice got its primary impetus in the mid

to late 1950s, a period that in a socio-literary con-

text is often referred to as The Thaw. This itself

is linked to Nikita Khrushchev’s campaign of de-

Stalinization, which provided an opening for liter-

ary themes previously disallowed. The opening

was frequently arbitrary as the case of Boris

Pasternak’s novel Dr. Zhivago proved in 1958. The

novel could not be published in the Soviet Union,

and Pasternak was brutally vilified despite being

awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

The fact that broad categories of literature and

sociopolitical themes still could not be addressed

moved much of this output underground into

samizdat. Sometimes this mode of literary output

was systematic as with later journals and chroni-

cles. But much of this was done spontaneously on

an individual basis. Of key importance is that

samizdat is inextricably linked to what came to

be the dissident movements in the Soviet Union.

SAMIZDAT

1347

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

These, in turn, were linked with other groups seek-

ing, in early manifestations, protection of human

rights, greater religious freedom, and more ethnic

autonomy. As Scammell notes (1984, p. 507),

samizdat “had come into existence in the late fifties

as a result of the clash between the intellectuals’

post-Stalinist hunger for more freedom of expres-

sion and the continuing repressiveness of the cen-

sorship.” Freedom of expression was one thing, but

it was deadly to the state’s perception of what could

be allowed when the political admixture was in-

cluded. The fact that samizdat and dissent were

coeval is impossible to avoid and had great conse-

quences for Soviet history.

From the early 1960s to the collapse of the So-

viet regime in 1991, samizdat had an uneven his-

tory. There were periods of extreme repression, for

instance in 1972–1973. But samizdat was not

quelled. Very often, trials were benchmarks in the

advancement of samizdat and its many causes. The

February 1966 trial of two writers, Andrei Sinyavsky

and Yuli Daniel, who had been publishing abroad

for several years using pseudonyms, was a sensa-

tion since they were given seven and five years re-

spectively at hard labor for allegedly writing

anti-Soviet material. Their arrest led to public

protests by dissidents. A number of them were then

arrested, and this, in turn, led to further protests

and corresponding arrests. Books and pamphlets

with documents from these trials were frequently

compiled and circulated widely in secret. These

added much fuel to the fire, and a constant cycle

was created. The Soviet government was also se-

verely criticized worldwide because of a new pol-

icy of punishing dissident writers by confining

them to mental hospitals.

Samizdat and dissent grew despite all impedi-

ments. It was a cultural opposition, an indepen-

dent subculture, as Meerson-Aksenov (1977) called

it, and it signified that social and political judg-

ments stemming from sources other than the state

were seen to be critically significant. In reality, the

Soviet state was stymied by this phenomenon be-

cause it no longer knew quite how to handle it. The

blanket executions of the 1930s were out of the

question. The breadth of the criticism was also

sometimes incomprehensible to the government. It

could include everything from opposing the inva-

sion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 to the latest broad-

sides against modern art.

The most famous of the systematic publica-

tions was The Chronicle of Current Events, which was

issued without interruption from 1968 to 1972

and sporadically thereafter. Other notable publica-

tions included the Ukrainian Herad, the Chronicle of

the Catholic Church of Lithuania, and historian Roy

Medvedev’s Political Diary (which ran from 1964

to 1971). This is by no means to minimize the huge

number of individual contributions. Together they

undercut the power and prestige of the Soviet state.

See also: CENSORSHIP; DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; GOSIZDAT;

JOURNALISM; SINYAVSKY-DANIEL TRIAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bukovsky, Vladimir. (1978). To Build a Castle. London:

Deutsch; New York: Viking.

Meerson-Aksenov, Michael, and Shragin, Boris. (1977).

The Political, Social and Religious Thought of Russian

‘Samizdat’—An Anthology, tr. Nickolas Lupinin. Bel-

mont, MA: Nordland.

Reddaway, Peter, ed. and tr. (1972). Uncensored Russia:

Protest and Dissent in the Soviet Union. New York:

American Heritage.

Scammell, Michael. (1984). Solzhenitsyn: A Biography.

New York: Norton.

N

ICKOLAS

L

UPININ

SAMOILOVA, KONDORDIYA

NIKOLAYEVNA

(1876–1920), Bolshevik; leader of Communist

Party Women’s Department.

Konkordiya Samoilova was one of the founders

of the Soviet Communist Party’s programs for

emancipating women. Born into a priestly family

in Irkutsk, she studied in the Bestuzhevsky Courses

for Women in St. Petersburg in the 1890s. In 1901

Samoilova became a full-time member of the So-

cial-Democratic Labor Party.

Samoilova spent sixteen years in the revolu-

tionary underground, mostly in St. Petersburg. An

editor of Pravda (Truth) in 1913, she created a col-

umn on the female proletariat and, in 1914, with

Inessa Armand, Nadezhda Krupskaia, and Lyud-

mila Stal, founded Rabotnitsa (Female Worker), a

newspaper devoted to working-class women. In

1913 she also organized the first celebration in Rus-

sia of International Woman’s Day.

In 1917 Samoilova revived Rabotnitsa, which

had been closed by the tsarist government. In 1918

she worked closely with Inessa Armand and Alexan-

SAMOILOVA, KONDORDIYA NIKOLAYEVNA

1348

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

dra Kollontai to establish a women’s department

(the Zhenotdel) within the Communist Party. While

Armand and Kollontai developed the program for

women’s emancipation, Samoilova concentrated on

building the department from the ground up. Al-

ways an enthusiastic supporter of Vladimir Lenin

and a reliable, hard-working, efficient Bolshevik,

Samoilova was trusted by the party leadership, de-

spite the fact that she was as ardent an advocate

for work among women as the more flamboyant

Kollontai. She was also an able propagandist who

crafted vivid, accessible speeches and pamphlets.

Samoilova died of cholera on a propaganda trip

down the Volga in 1920.

See also: FEMINISM; KOLLONTAI, ALEXANDRA MIKHAIL-

OVNA; ZHENOTDEL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1997). Bolshevik Women. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, Elizabeth A. (1997). The Baba and the Comrade:

Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

B

ARBARA

E

VANS

C

LEMENTS

SAMOUPRAVLENIE

Samoupravlenie, or self-management, was intro-

duced during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika as a

mechanism to induce enterprises to produce qual-

ity products desired by customers and as a way of

extending democratization to the workplace. Soviet

enterprises were placed on full economic account-

ing (polny khozraschet), which meant that current

operations had to be self-financed from sales rev-

enues rather than subsidized by central or minis-

terial authorities, and any change or expansion in

operations had to be financed from retained earn-

ings. Managers were to be elected by the employ-

ees and to work directly with a council selected

from among the workers. The objective of samou-

pravlenie was to reduce “petty tutelage,” the phrase

for interference in day-to-day enterprise operations

by planning or other administrative officials.

Samoupravlenie was part of a larger effort to

promote initiative and responsibility in Soviet en-

terprises. For example, the number of compulsory

plan targets given to enterprises was reduced, pro-

viding more flexibility for them to select produc-

tion strategies to improve their operations and per-

formance. Enterprise performance was to be gauged

relative to long-run plans and norms. A system of

state orders (goszakazy) was to replace compulsory

output targets, although the distinction between

state orders and plan targets was never clarified.

Enterprises were granted the right to exchange

goods, with contracts negotiated between firms to

include output, delivery, and price components

agreed upon by both firms. Enterprises were also

allowed to retain a greater share of their planned

profits to distribute as bonuses or to invest in ad-

ditional capital. Samoupravlenie was an attempt to

make Soviet managers responsible for the final re-

sults; that is, producing the quantity and quality

of output desired by customers, whether firms or

individual consumers.

See also: PERESTROIKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aganbegyan, Abel. (1988). The Economic Challenge of Per-

estroika. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Gregory, Paul R. (1990). Restructuring the Soviet Economic

Bureaucracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

SAN STEFANO, TREATY OF

The Treaty of San Stefano, signed March 3, 1878,

ended the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).

On January 31, 1878, with Russian victory

over Turkey a foregone conclusion, the belligerents

agreed to an armistice at Adrianople, followed by

peace negotiations at San Stefano, a village near

Constantinople. There, Count Nikolai Pavlovich Ig-

natiev, former ambassador to the Porte, and Savfet

Pasha worked out final terms for signature on

March 3, the anniversary date of Tsar Alexander

II’s imperial accession.

Accordingly, Turkey agreed to pay reparations

of 1.41 billion rubles, of which 1.1 billion would

be cancelled by cession to Russia in Asia Minor of

Ardahan, Kars, Batumi, and Bayazid. In the Bal-

kans, Turkey ceded northern Dobrudja and the

Danube delta to Russia for ultimate transfer to

Romania, in return for Romanian agreement to

Russian occupation of southern Bessarabia. With a

seaboard on the Mediterranean and an elected prince,

Bulgaria remained under nominal Turkish control,

SAN STEFANO, TREATY OF

1349

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

while Bosnia and Herzegovina received autonomy.

Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro received their in-

dependence, along with territorial enlargement.

Turkey was obliged strictly to observe concessions

for local participation in government that were in-

herent in the Organic Regulation of 1868 on Crete,

while analogous regimes were to be implemented

in Thessaly and Albania. The Porte was also to in-

troduce reforms in Turkish Armenia.

The San Stefano Treaty formally went into ef-

fect on March 16, 1878, but concerted opposition

from Great Britain and Austria-Hungary, together

with Russia’s growing diplomatic isolation, meant

that the agreement remained only preliminary. In-

deed, its main provisions subsequently underwent

substantial revision at the Congress of Berlin in

July 1878.

See also: BERLIN, CONGRESS OF; RUSSO-TURKISH WARS;

TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jelavich, Barbara. (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow:

Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

O

LEG

R. A

IRAPETOV

SARMATIANS

Between the sixth and fourth centuries

B

.

C

.

E

., the

Sarmatians settled in what is today southern Rus-

sia, eventually replacing the Scythians as the dom-

inant tribe in this region. They vanished from the

historical record after their land was overrun by

the Huns in the late fourth century

C

.

E

., and little

is known about them.

They rose again, however, in the realm of

mythology. According to a legend which gained

popularity in Poland in the fifteenth century, the

ancient Sarmatians rode into the Polish lands and

gave order and stability to the primitive local pop-

ulation. This myth helped justify serfdom, allow-

ing the nobles to imagine that they were of a

superior racial lineage. The Sarmatian story became

enormously popular, leading some to call Coperni-

cus the Sarmatian Ptolemy.

Sarmatianism did not have any specific reli-

gious content at first, but during the Counter-

Reformation, as Catholics worked to stamp out

religious diversity in the Polish Republic and as the

state fought against non-Catholic foes outside the

country, the legend mutated to include the idea that

the Sarmatians had a mission from God to spread

and defend the True Faith.

By the end of the seventeenth century, Sarma-

tianism had developed a xenophobic character, as

many Polish nobles turned away from all “foreign”

influences to glory in their indigenous Sarmatian

heritage. This myth even influenced the style of

clothing, art, and architecture of Poland during the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as the nobles

came to fancy pseudo-oriental designs that they felt

evoked their racial heritage.

The intellectuals of the Polish Enlightenment

blamed Sarmatianism for the crises of the eight-

eenth century and for Poland’s eventual destruc-

tion and partition. Although some of the stylistic

features lived on a bit longer, the broader ideology

of Sarmatianism faded away in the nineteenth cen-

tury or lived on as a trace element within new ide-

ological formations.

See also: HUNS; POLAND; SCYTHIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bogucka, Maria. (1996). The Lost World of the “Sarma-

tians”: Custom as the Regulator of Polish Social Life in

Early Modern Times. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sci-

ences.

Grabowska, Bozena. (1993). “Portraits after Life: The

Baroque Legacy of Poland’s Nobles.” History Today

43:18.

B

RIAN

P

ORTER

SARTS

Former term for Turkic-speaking Muslim residents

of cities along the Syr Darya River, the Ferghana

Valley, and Samarkand.

According to Russian Imperial sources, Sarts ex-

ceeded 800,000 people and comprised 26 percent of

the population of Turkestan and 44 percent of the

urban population of Central Asia in 1880. The term

was the subject of lively debate in the late-nineteenth

century when Russians colonized Central Asia.

Vasily Bartold described the Sarts as settled peoples

in Central Asia, Turkicized Old Iranian population,

emerging from a conglomeration of Saka, Sogdian,

Kwarazmian, and Kush-Bactrians.

SARMATIANS

1350

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The ancient Turkic word Sart, originally mean-

ing “merchant,” was used by Mongols and Turks

by the thirteenth century to identify the Iranian

population of Central Asia. In the sixteenth cen-

tury, Uzbeks who conquered Central Asia used

“Sart” to distinguish the sedentary population of

Central Asia from the nomadic Turkic groups set-

tling in the region. By the nineteenth century, the

urban Sart population had merged cultural, lin-

guistic, and ethnic elements from their Persian and

Turko-Mongolian lineage. They remained distinct

from Uzbeks even though their language belongs

to the Chagatay-Turkic group. On the eve of the

Russian Revolution, “Sart” was a self-denomina-

tion distinguished from Uzbeks and Tajiks despite

the cultural synthesis in Turkestan.

Soviet nationality policies made the term obso-

lete. Following the first counting of the 1926

census, Sarts were listed as a questionable nation-

ality. By the end of 1927, the majority of Sarts

were designated as Uzbek and others were named

Sart-Kalmyks. They were not considered Tajik be-

cause they were Turkic-speaking. Of the 2,880

Sart-Kalmyks listed in the 1926 census, there were

2,550 in Kirgiz ASSR, fewer than 250 in Uzbek SSR

(all located in Andijan), and none in Tajik ASSR. By

the 1937 census, the ethnic marker disappeared.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bregel, Yuri. (1978). “The Sarts in the Khanate of Khiva,”

Journal of Asian History 12 (2):120–151.

Schoeberlein, John. (1994). “Identity in Central Asia:

Construction and contention in the conceptions of

‘Özbek,’ ‘Tâjik,’ ‘Muslim,’ ‘Samarqandi’ and other

groups.” Ph.D. diss. Harvard University.

M

ICHAEL

R

OULAND

SBERBANK

Sberbank (the Savings Bank) was the monopoly,

state-owned household savings bank of the USSR.

It retained both its state ownership and its domi-

nance of the retail banking market in the post-

Soviet period, despite increasing competition from

commercial banks. In the Soviet period, Sberbank’s

retail banking network encompassed approxi-

mately 70,000 branches and smaller “cash offices”

(sberkassy) on almost every corner across the So-

viet Union. The Ministry of Finance directly con-

trolled this network until 1963, when it was in-

corporated into Gosbank (the state bank of the

USSR). Sberbank’s main task was to collect the in-

dividual deposits and invest them with the state. In

addition, Soviet citizens paid their bills and picked

up their pension checks at their local Sberbank of-

fices.

After the breakup of the USSR, Sberbank Rus-

sia became a quasicommercial savings bank, with

the Central Bank of Russia as its majority share-

holder. Sberbank continued to invest a high per-

centage of its resources with the government (e.g.,

in government securities), giving it the nickname

“the Ministry of Cash.” Although commercial

banks began to compete with Sberbank for retail

deposits, Sberbank’s share of the retail market

never fell below 60 percent in the 1990s. This oc-

curred for three reasons. First, no new bank could

compete with Sberbank’s extensive branch net-

work. Second, the government explicitly insured

deposits in Sberbank, while commercial banks had

no deposit insurance system. Third, repeated com-

mercial banking crises made Sberbank appear to be

a safer choice than other banks. However, it bears

noting that the vast majority of Russians chose to

keep their savings outside of the banking system

entirely.

See also: BANKING SYSTEM, SOVIET; GOSBANK; STROIBANK

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Johnson, Juliet. (2000). A Fistful of Rubles: The Rise and

Fall of the Russian Banking System. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press.

Tompson, William. (1998). “Russia’s ‘Ministry of Cash’:

Sberbank in Transition.” Communist Economies and

Economic Transformation 10(2):133–155.

J

ULIET

J

OHNSON

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY

Leading scientists and policy makers in the Soviet

Union rapidly reached an accommodation after the

revolution in October 1917. The scientific commu-

nity was decimated by deaths and emigration that

resulted from World War I, revolution, and civil

war. Those scientists who remained recognized that

the new regime, unlike the tsarist government, in-

tended to support scientific research. They quickly

established a number of research institutes and

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY

1351

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

received gold rubles to buy journal subscriptions,

equipment, and reagents abroad. Government offi-

cials, for their part, believed that scientific and en-

gineering expertise was critical to the establishment

of communism. Hesitantly at first, they offered

academic freedom as well as financial and admin-

istration support to the scientists. They remained

skeptical about the value of fundamental research.

Party officials also believed that scientists, most of

whom were trained in the tsarist era, required close

supervision by loyal communists.

Several different bureaucracies were responsi-

ble for the administration and funding of science,

and scientists were deft at playing them off against

each other to increase their funding. The major ones

were the Main Scientific Administration of the

Commissariat of Education (Glavnauka) and the

Scientific Technical Department of the Supreme

Economic Council (NTO). Generally speaking, in-

stitutes whose focus was basic research fell under

the jurisdiction of Glavnauka, while those of an ap-

plied profile fell under NTO.

When Josef Stalin rose to power in the late

1920s, fundamental changes in science policy oc-

curred that largely held sway until the collapse of

the USSR. The changes reflected crash programs in

rapid industrialization and collectivization of agri-

culture. First, officials intended that scientists em-

phasize applied research at the expense of basic

research. This led to the removal of many of the in-

stitutes under the jurisdiction of the Glavnauka to

the Commissariat of Heavy Industry and the estab-

lishment of a technical division within the Academy

of Sciences. Second, the Communist Party began a

concerted effort to place personnel loyal to it in re-

search institutes. It forced the relatively independent

Soviet Academy of Sciences to create many new po-

sitions, or chairs, for permanent members in such

new fields as the social sciences, and insisted that

party members be voted in during elections.

Third, officials required that scientists produce

detailed one-year and five-year plans of research

activity. Since the Commissariat of Heavy Indus-

try was relatively flush with funding, scientists

found leeway in planning and financial documents

to embark on research in several important new di-

rections, for example, nuclear physics and cryo-

genics in the 1930s. Finally, officials insisted upon

strict ideological control over the content of science

and effectively established autarchy (international

isolation) that persisted until the late 1980s.

Party officials had indicated their intention to

control scientists in a series of show trials in 1929

and 1930 where they used forced confessions of

engineers to prove “wrecking” of plans. They pun-

ished wrecking with long prison terms and in some

cases execution. During the Great Terror of the

mid-1930s, scientists, no less than other members

of society, also faced arrest, interrogation, intern-

ment in labor camps (there were several special

labor camps for scientists and engineers), and exe-

cution. Scientists’ professional associations were

subjugated to party organizations.

Several fields of science suffered from ideolog-

ical meddling. In the most notorious case, Trofim

Lysenko, a biologist who rejected modern genetics,

came to dominate the Soviet biology establishment

from the 1940s until the early 1960s. The author-

ities ordered references to genetics removed from

textbooks, and many geneticists lost their jobs.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY

1352

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A 1966 experiment in a chemistry laboratory at

Akademgorodok—the Siberian “Academic City.” © D

EAN

C

ONGER

/CORBIS