Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

influence on actual decision-making. And far from

being a springboard for ambitious politicians, it

was more a tool for Boris Yeltsin to balance rival

figures.

Skokov was replaced as secretary in June 1993

by a former Soviet general, Yevgeny Shaposhnikov,

and then in October 1993 by a Yeltsin crony, Oleg

Lobov. In June 1996 Alexander Lebed was ap-

pointed secretary, in return for his support of

Yeltsin in the second round of the presidential elec-

tion. Lebed was assigned to end the war in Chech-

nya, and much to everyone’s surprise he succeeded,

signing a peace accord and withdrawing Russian

troops. Concerned about Lebed’s growing popular-

ity, Yeltsin created a separate Defense Council in

July and fired Lebed in October, accusing him of

plotting a military coup. Lebed was replaced by the

anodyne politician Ivan Rybkin, with the contro-

versial oligarch Boris Berezovsky as his deputy, in

charge of reconstructing Chechnya. (Berezovsky

quit in November 1997.)

From March to September 1998, the Security

Council was headed by an academic, Andrei

Kokoshin. He was replaced by a KGB general, Niko-

lai Boryuzha, who in turn was followed in March

1999 by Vladimir Putin, who was simultaneously

head of the Federal Security Service (FSB). In No-

vember 1999 Putin was replaced at the council by

his deputy at the FSB, Sergei Ivanov. In March 2001

Ivanov became defense minister, and the former in-

terior minister, Vladimir Rushailo, became Security

Council secretary.

During Vladimir Putin’s presidency, the Secu-

rity Council became slightly more visible as a fo-

rum through which he tried to press forward with

military reforms obstinately resisted by the gener-

als. The new National Security Concept drawn up

by the council in 2000 stressed internal threats,

such as Chechen terrorism, over traditional secu-

rity concerns, such as nuclear deterrence.

See also: POLITBURO; PRESIDENCY; PRESIDENTIAL COUN-

CIL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Jan. S. (1996). “The Russian National Security

Council.” Problems of Post-Communism 43(1):35–42.

Derleth, J. William. (1996). “The Evolution of the Rus-

sian Polity: The Case of the Security Council.” Com-

munist and Post-Communist Studies 29(1):43–58.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

SERAPION BROTHERS

The Serapion Brothers were a group of poets and

writers who insisted on the political autonomy of

the artist and the affirmation of imagination and

creative art. They argued that in order to remain au-

thentic, the writer’s voice needed freedom from all

social or political constraints. They denounced the

use of literature for utilitarian purposes and never

adopted a specific model of literary production.

The Serapion Brothers began meeting in 1921

at the Petrograd House of Arts at the suggestion of

Viktor Shklovsky. The group, which eventually

included Konstantin Fedin, Ilya Gruzdev, Vsevolod

Ivanov, Veniamin Kaverin, Lev Lunts, Nikolai

Nikitin, Elizaveta Polonskaya, Vladimir Pozner,

Mikhail Slonimsky, Nikolai Tikhonov, and Mikhail

Zoshchenko, adopted its name after a tale by E. T.

A. Hoffmann. Shklovsky occasionally participated,

and Maxim Gorky supported members with ma-

terial assistance and help in publishing their work.

The group met weekly to read and discuss one an-

other’s work, focusing on the refinement of the

craft of writing and leaving each member to de-

velop his or her own message, sometimes engag-

ing in heated debates about the purpose or meaning

of literature.

The closest the Brotherhood came to publish-

ing a manifesto was Lev Lunts’s “Why We are the

Serapion Brothers” (Pochemu my Serapionovy Bratya,

1922), in which he proclaimed that “Art is real, like

life itself. And, like life itself, it is without goal and

without meaning: It exists because it cannot help

but exist.” This statement of the group’s purpose

sparked a sharp debate with Marxist critics who

insisted on the utilitarian use of literature for com-

mon ideological purposes. Lunts, however, stressed

the autonomy of literature from political purposes

or control and, simultaneously, the preservation of

diverse ideological positions within the brother-

hood. The one collective work the group published,

the First Almanac (Serapionovy Brat’ia. Al’mankh

pervy, 1922) demonstrates this wide range of style

and philosophy. Throughout the 1920s they

promoted a nonpolitical approach to literature, tol-

erance, and friendship, and their connections con-

tinued after the group’s dissolution in 1929.

See also: CULTURAL REVOLUTION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hickey, Martha Weitzel. (1999). “Recovering the Au-

thor’s Part: The Serapion Brothers in Petrograd.”

Russian Review 58(1):103–123.

SERAPION BROTHERS

1363

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kern, Gary, and Collins, Christopher, eds. (1975). The

Serapion Brothers: A Critical Anthology. Ann Arbor:

Ardis.

E

LIZABETH

J

ONES

H

EMENWAY

SERBIA, RELATIONS WITH

From the first days of the initial Serb uprising in

1804 (against the tyranny of the Janissaries, mil-

itary units that had evolved from being the elite

troops of the Ottoman Empire into semi-indepen-

dent occupiers) until 1878 (when Belgrade obtained

complete independence from the Porte at the Con-

gress of Berlin), relations with Serbia were central

to Russia’s foreign policy. However, as Serbia pur-

sued both independence from Istanbul and expan-

sion of the state to include all Serb lands (Bosnia,

Hercegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Vojvodina),

Russia often found itself drawn into Serbian for-

eign affairs as Belgrade came to depend upon (and

use) Russian support for its own ends. This led to

a relationship that offered Serbia the greatest ad-

vantages as St. Petersburg became captive to two

critical forces: 1) the emergence of Panslavism, a

movement that stressed the solidarity of the Slavic

peoples ostensibly under Russian leadership, and

2) the Eastern Question, the increasing vacuum in

southeastern Europe brought about by the rapid

decay of the once great Ottoman Empire, which

presented an inviting target of opportunity for the

great powers.

The romantic image of Orthodox Christians

fighting the Muslim Turks for freedom continu-

ously vexed St. Petersburg. On the one hand, ad-

visers generally supported a policy of moderation

in the region and a concentration on domestic

needs. However, Panslavists, who had a powerful

effect upon Russian public opinion, attacked the no-

tion of passivity toward their Christian and Slavic

brethren who, they claimed, were suffering at the

hands of either the Turks or the Habsburgs.

After the disastrous Crimean War and the sub-

sequent humiliating Treaty of Paris in 1856, Rus-

sia was confronted by conflicting goals: the need

to deal with internal problems as well as to restore

its influence in the Balkans. When a revolt began

in Hercegovina against the Turks in 1875, the lore

and lure of Slavic Christians rising up against their

Muslim occupiers proved to be intoxicating. Russians

immediately volunteered to support the insurrec-

tion. General M. G. Chernyayev took command of

the Serbian army, and by 1876 Serbia was at war

with the Porte.

The conflict however was disastrous for Serbia.

Not only was the country poorly prepared for war,

but friction arose between the Russian and Serbian

forces as Chernyayev proved to be an inept com-

mander. While events inside Serbia deteriorated, St.

Petersburg concluded a series of agreements with

Vienna, providing that in the event Russia went to

war with the Turks, the Habsburgs would be neu-

tral.

In April 1877, Panslavist pressure forced Rus-

sian Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov to join

the conflict, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

Despite military setbacks, Russia forced the Turks

to sign the Treaty of San Stefano. However, Rus-

sia’s victory proved to be short-lived as the other

great powers quickly blocked St. Petersburg’s de-

signs to obtain primacy in the region through the

creation of a “big” Bulgaria. At the 1878 Congress

of Berlin, the powers compelled Russia to concede

on the issue of an enlarged Bulgarian state, while

the Turks were forced to grant complete indepen-

dence to Serbia (as well as Romania and Greece).

However, Russian support for Bulgaria had alien-

ated Belgrade. For the next quarter-century, Serbia

distanced itself from Russia. Only the murder of

King Alexander Obrenovic in 1903 and the as-

sumption of power by Peter Karadjordjevic led to

a reorientation of Serbian policy back to regional

cooperation and a reliance on Russia (especially

after the Bosnian crisis of 1908–1909, which saw

the formal annexation of Bosnia-Hercegovina by

Austria-Hungary).

Weakened by the events of the Russo-Japanese

War of 1904–1905 and the Revolution of 1905,

Russia could not challenge Vienna in 1908 on be-

half of its Serbian client state. Nevertheless, the

Bosnian crisis pushed Belgrade and St. Petersburg

closer together. The former became solely depen-

dent upon Russia for support among the great

powers, while the latter realized that it had to sup-

port its Serbian ally in the future lest it lose influ-

ence in the region. Russia now sought to foster a

regional alliance between Serbia and Bulgaria, an

act that led to the formation of a Balkan League

and subsequently the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913.

These wars, the unintended consequence of Rus-

sia’s attempt to create a defensive alliance in the re-

gion to counter the Habsburgs, further destabilized

southeastern Europe and left Russia even more

tethered to Belgrade.

SERBIA, RELATIONS WITH

1364

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

During the days and weeks following the as-

sassination of Habsburg archduke Franz Ferdinand

in June 1914, Russia steadfastly backed its sole re-

maining Balkan ally, a critical factor leading to the

outbreak of World War I. In its attempt to support

Belgrade against Austro-Hungarian demands, Rus-

sia now found itself immersed in a conflict for

which it was ill prepared and that would lead to

the destruction of the Romanov monarchy.

See also: BULGARIA, RELATIONS WITH; MONTENEGRO, RE-

LATIONS WITH; PANSLAVISM; TURKEY, RELATIONS

WITH; YUGOSLAVIA, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Glenny, Misha. (2000). The Balkans: Nationalism, War,

and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York: Viking

Penguin.

Jelavich, Barbara. (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow:

Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Jelavich, Charles, and Jelavich, Barbara. (1977). The Es-

tablishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920.

Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Rossos, Andrew. (1981). Russia and the Balkans: Inter-

Balkan Rivalries and Russian Foreign Policy, 1908–1914.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

R

ICHARD

F

RUCHT

SEREDNYAKI

The serednyaki, or middle peasants, were peasants

whose households in the 1920s had enough land

to support their extended family (dvor) and some-

times even the hiring of one of the poorer bednyaki

or landless batraki of the neighborhood in busy sea-

sons. In practice, some of the middle peasants lived

no differently from the poorer classes; they too had

no draft horse (malomoshchnyi) and might likewise

hire out a family member in the village commu-

nity or send him to a nearby city or rural enter-

prise as wage labor. Many were illiterate. Other

members of this intermediate stratum of peasants,

however, were prosperous (zazhitochnye or krepkie)

and thus close to the richer kulaks who constituted

about 5 to 7 percent of the peasantry. These bet-

ter-off peasants would sell some surplus grain if

provided an incentive in the form of manufactured

goods, and thus were crucial to the alliance of

workers and peasants (smychka) that was supposed

to be the political basis of the New Economic Pol-

icy (NEP) of 1921 to 1928.

Although the Marxist-Leninist categories barely

fit the complex reality of the Russian countryside,

Vladimir Lenin expected the serednyaki to be toler-

ant of Bolshevik power and policies in the rural ar-

eas, and saw them as a temporary ally until such

time as the regime could afford to incorporate them

into more modern collective farms. There was a dan-

ger, however, that industrious middle peasants who

prospered would became petty bourgeois allies of

the kulaks and thus would oppose Soviet industri-

alization and the heavy taxes and price discrimina-

tion it required. The Marxist-Leninist category of

middle peasant, unlike the traditional terms bednyak

or kulak, meant little to the peasants themselves.

Many other factors besides ownership of productive

capital influenced their behavior. Populist students

of the peasantry, notably A. V. Chayanov, and later

sociologists have challenged this conceptualization

of the NEP village as too static.

The schematic class analysis of the Soviet coun-

tryside was not merely ideological. Depending on

one’s class, one could obtain benefits or avoid

penalties. Poor peasants enjoyed tax exemptions

and preferential admission to schools and Com-

munist Party organizations; kulaks (along with

priests and the bourgeois) were deprived of these

and even of the right to vote. Late in the NEP, taxes

on middle peasants increased, though not as much

as those imposed on the kulaks. Not surprisingly,

middle peasants endeavored to be officially identi-

fied as poor—for example, by referring to past pro-

letarian occupations. They would sometimes try to

hide their prosperity by hiring out some labor or

a horse. Nonetheless, when forced requisitioning of

grain was reinstated in 1928, the prosperous peas-

ants were affected adversely. “Dekulakization” and

collectivization in 1929 to 1931 made it even more

important to avoid official identification with the

richest peasant stratum.

See also: KULAKS; PEASANT ECONOMY; PEASANTRY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1991). “The Problem of Class Iden-

tity in NEP Society.” In Russia in the Era of NEP,

ed. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Alexander Rabinowitch, and

Richard Stites. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Lewin, Moshe. (1968). Russian Peasants and Soviet Power.

London: Allen & Unwin.

SEREDNYAKI

1365

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Shanin, Teodor. (1972). The Awkward Class: Political So-

ciology of Peasantry in a Developing Society, Russia,

1910–1925. London: Oxford University Press.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

SERFDOM

Serfdom is the name of the condition of a peasant

who does not enjoy the rights of a free person, but

is not a slave. While the slave is an object of the

law, the serf is still a subject of the law. The clas-

sic definition of serfdom in the Russian context is

given in Jerome Blum’s Lord and Peasant in Russia

(pp. 6–8). Thus a serf is a peasant who (1) is bound

to the land; or (2) is bound to the person of a lord;

and (3) is not directly subject to the state, but is

subject to a lord who in turn is subject to the state

(such as it may be). Thus a serf bound to the land

cannot be moved by any lord, and is supposed to

be a “fixture” on that land regardless of who owns

or holds the land. But if a serf is bound to the per-

son of a lord, he essentially begins to resemble a

slave in that the lord nearly becomes the owner of

the serf: the lord can move the serf from one plot

of land to another (or even into his household), and

may even be able to sell the serf to a third party.

The first and second conditions are mutually ex-

clusive, for a serf cannot be bound to the land and

simultaneously bound to the person of a lord. The

third condition is most difficult to comprehend, but

can arise under one of two circumstances: either

state power does not exist (as during the manorial

era of Russia in the early period of the “Mongol

yoke,” from 1237 to 1300 or even 1350) and thus

the sole extant conflict-resolution power is exer-

cised by a large estate owner, or the existing state

power has abdicated or ceded judicial or taxing au-

thority to the owner or holder of land. The third

condition can exist by itself or in conjunction with

the first or second conditions.

Whether there was serfdom of the third cate-

gory in the early Mongol period, after the collapse

of Russian princely power and during the period

when the sole authority may have been the owner

of a large estate (votchina) or manor, is an issue.

While there may have technically been serfdom be-

tween 1237 and 1300 or 1350, the reality was cer-

tainly such that no peasant knew he was a serf. In

those decades most peasants lived on land they con-

sidered their own, not on a manor. Moreover, given

the reigning system of slash-and-burn (assartage)

agriculture, peasants were accustomed to farming

a new plot of land every three years and could

freely move away from any manorial lord who

was the slightest bit oppressive. Thus no one views

any of the peasants of Russia as “serfs” until the

second half of the fifteenth century.

Serfdom began as a result of the civil war of

1425–1453, which left much of Russia in ruins.

Selected monasteries were allowed to forbid their

peasant debtors to move at any time except around

St. George’s Day (November 26—compare with the

U.S. Thanksgiving holiday), the day in the pagan

calendar when the harvest was completed and thus

debts could be collected. In 1497 the St. George’s

Day limitation was extended to all peasants; they

were bound to the land and could not legally move

at other times of the year. Lords were limited to

collecting the traditional rent and had no author-

ity over the peasants.

Ivan IV’s mad Oprichnina (1565–1572) was re-

sponsible for initiating changes in the status of the

peasant. Ivan gave his special Oprichnina troops,

the oprichniki, control over the peasants living on

the lands they possessed, which allowed them to

raise their rents to whatever level they pleased. As

a result the oprichniki “collected as much rent in

one year as previously had been collected in ten.”

This and other barbarous acts of the Oprichnina re-

sulted in the depopulation of much of old Muscovy

as the peasants fled to newly annexed areas (colo-

nial expansion). Certain landholders (pomestie) then

successfully petitioned the government to repeal the

peasants’ right to move on St. George’s Day. In

1592 this repeal was temporarily extended to all

peasants. Thus serfdom became the temporary le-

gal status of all peasants.

Limitations were placed on the recovery of

fugitive peasants in 1592, but they were repealed

in the Law Code of 1649 (Ulozhenie). According to

Chapter 11, Article 1, of the Ulozhenie of 1649,

any peasants who had been recorded as living

on state, court, or peasant taxable lands could be

returned to those lands without any time limits.

Article 2 stated the same for peasants living on

seignorial lands. Thus all peasants in Russia within

the reach of the Ulozhenie were serfs. The code also

specified how runaways should be returned, and

especially what should happen if male and female

fugitives married. The Orthodox Church held that

marriage was inviolable, so the couple had to be

returned to the lord of one of them. The most ra-

SERFDOM

1366

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tional solution to this problem was that the lord

who received a fugitive lost the couple, as punish-

ment for having received the runaway. If the cou-

ple was on neutral territory, the contesting lords

cast lots; the winner got the couple and paid the

loser 10 rubles for the serf he had lost. The serf

family was not inviolable, however, and under cer-

tain circumstances could be broken up.

Other articles of the Ulozhenie established rules

that led to the further abasement of the serfs, ul-

timately to a change in their status to something

resembling slaves. It started with owners of hered-

itary estates, who were allowed to manumit their

serfs (a practice ominously borrowed from slav-

ery) and transfer them from one estate to another.

This seemed innocent enough, as the state was pri-

marily concerned about service landholdings and

having the serfs there to support whichever cav-

alryman might be holding it at the moment. Both

logical and juridical problems automatically arose

when service landholdings were converted into

hereditary estates in 1714.

Prior to that time, however, it appears that the

process of converting the serf from a peasant bound

to the land to a peasant bound to the person of a

lord was under way. Between the Ulozhenie and

the introduction of the soul tax in 1721, the ex-

tent to which this had progressed is disputed. Some

transactions appear to have been concealed sales of

peasants, for example. After 1721, conditions

worsened. Lords were held responsible for the col-

lection of the soul tax, which putatively gave them

additional power over the serfs. Then in 1762 lords

were freed from twenty-five-year (essentially life-

time) compulsory military service, so that many

of them spent most of their lives on their estates

and took an interest in the management of those

estates. This was the coup de grace, which often

SERFDOM

1367

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

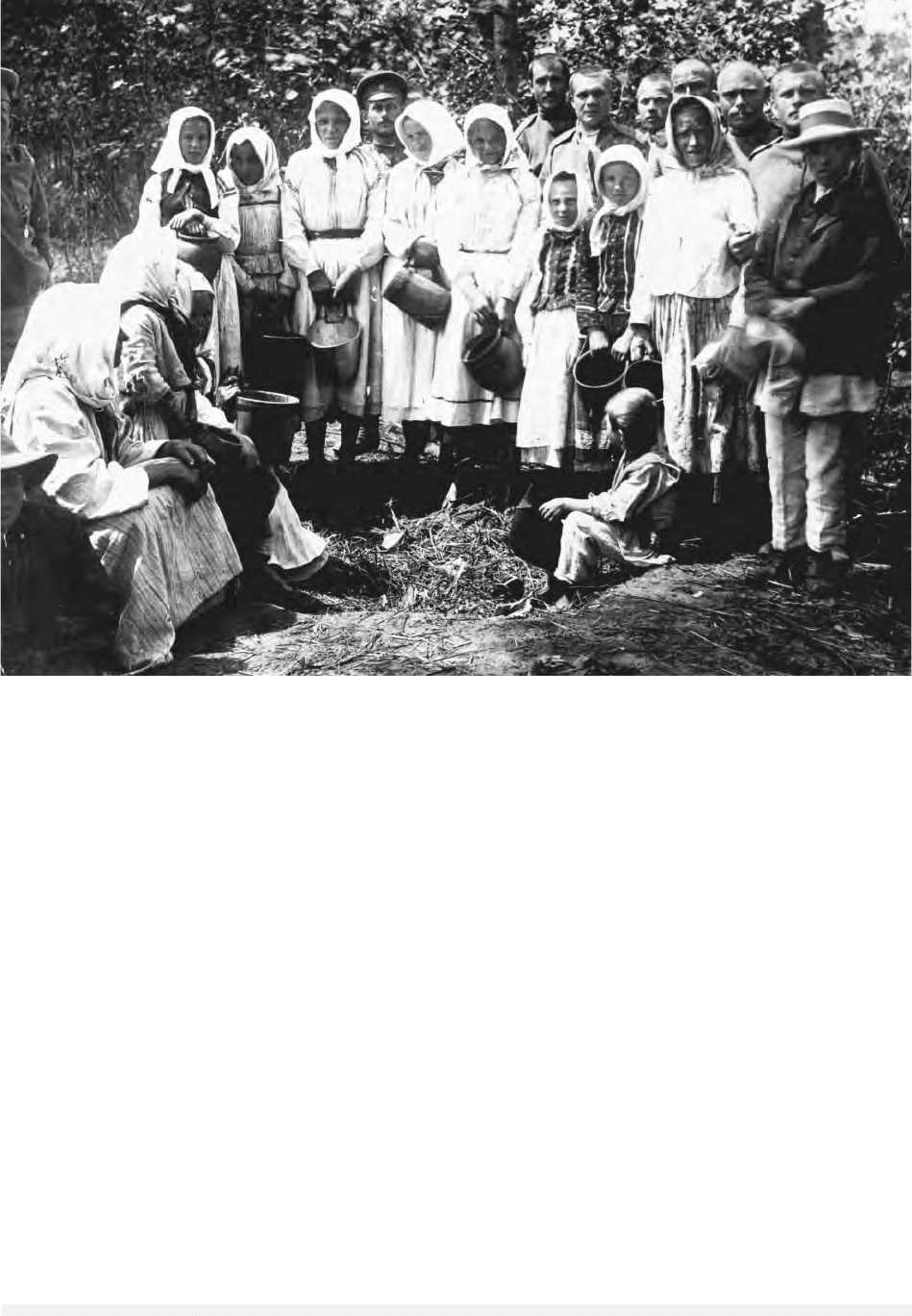

Serfs line up to draw water from a village well. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

converted seignorial serfdom into near slavery.

Serfs were auctioned, traded, moved to wherever

their lords wanted them to live, and even compelled

to breed. However, lords did not own a serf’s in-

ventory, clothing, personal property, and so on.

These features increasingly distinguished seignor-

ial serfs from serfs living on state and court lands,

who came to be called “state peasants” even though

they were still really serfs.

Serfdom was abolished in stages, depending on

which category peasants belonged to. In 1861

serfs serving in lords’ households (house serfs

[dvorovye lyudi], nominally, and probably fre-

quently literally, descendants of house slaves who

had been put on the tax rolls in 1721) and

possessional serfs (those assigned to work in fac-

tories, typically textile and metallurgical, whose

output collapsed in 1861) were freed in all respects

immediately. Seignorial serfs were immediately freed

from landlord control (from being bound to the

person of their lord) and were instead bound to the

commune (i.e., to the land). This was done to avoid

flooding the cities (officials knew the Manchester

phenomenon) and to ensure stability (the same of-

ficials believed the commune was a stabilizing fac-

tor in the countryside). A separate emancipation

freed the state serfs and peasants in 1863. Serfdom

was finally abolished in 1906 and 1907, when

communal control over the former seignorial peas-

ants was abolished and they were allowed to move

wherever they desired. Many peasants believed that

serfdom was reinstituted when the Soviets collec-

tivized agriculture at the end of the 1920s.

See also: EMANCIPATION ACT; ENSERFMENT; LAW CODE

OF 1649; OPRICHNINA; PEASANTRY; SLAVERY

SERFDOM

1368

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An illustration of serfs toiling in the field. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Jerome. (1961). Lord and Peasant in Russia: From

the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Emmons, Terence. (1968). The Russian Landed Gentry and

the Peasant Emancipation of 1861. London: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Field, Daniel. (1976). The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bu-

reaucracy in Russia, 1855–1861. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hellie, Richard, ed. and tr. (1967 and 1970). Muscovite

Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Syllabus

Division.

Hellie, Richard, editor and translator. (1988). The Mus-

covite Law Code (Ulozhenie) of 1649. Irvine, CA:

Charles Schlacks, Jr., Publisher.

Moon, David. (2001). The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia,

1762–1907. New York: Longman.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

SERGEI, PATRIARCH

(1867–1944), twelfth patriarch of Moscow and All

Russia, 1943–1944.

The son of a provincial priest, Ivan Nikolaevich

Stragorodsky graduated from the St. Petersburg

Theological Academy. He became the monk Sergei

in 1890 and was consecrated bishop in 1901. He

presided over the famous religious-philosophical

seminars in St. Petersburg (1901–1903) before be-

coming archbishop of Finland (1905–1917). After

1917, he wielded great influence as a metropolitan

while causing controversy with his willingness to

seek political compromise. Sergei recognized the

schismatic Living Church Movement in June 1922,

although he later publicly repented to Patriarch

Tikhon for this error in judgment. The Soviet gov-

ernment prevented election of a new patriarch

when Tikhon died in 1925. Metropolitan Peter Po-

liansky served as the locum tenens (guardian of the

patriarchate) and chose Sergei as his deputy. Sergei

became de facto leader of the church after Peter’s

arrest. Under pressure from the state and rival bish-

ops, Sergei issued a declaration in July 1927 that

proclaimed the church’s loyalty to the Soviet gov-

ernment and brought a temporary halt to religious

persecution. Orthodox leaders in the USSR and

abroad condemned Sergei’s declaration, however,

and renounced his authority.

The fractured Orthodox Church declined under

renewed persecution in the 1930s but experienced

rebirth during World War II. The day of the Ger-

man invasion (June 22, 1941), Sergei issued a mes-

sage asking all believers to rally to the defense of

the nation. He subsequently encouraged large-scale

offerings by Orthodox parishes for the war effort.

In September 1943, Josef Stalin met with Sergei

and two other metropolitans for the purpose of

reestablishing the church’s national organization.

That month, a council of bishops elected Sergei as

patriarch of Moscow and All Russia. He served un-

til his death on May 15, 1944.

See also: LIVING CHURCH MOVEMENT; PATRIARCHATE;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; TIKHON, PATRIARCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtiss, John S. (1952). The Russian Church and the So-

viet State, 1917–1950. Boston: Little, Brown.

Innokentii, Hegumen. (1993). “Metropolitan Sergii’s De-

claration and Today’s Church.” Russian Studies in

History 32(2):82–88.

E

DWARD

E. R

OSLOF

SERGIUS, ST.

(c. 1322–1392) Saist, founder of the Trinity mo-

nastery near Moscow, leader of a monastic revival,

participant in political and ecclesiastical politics, and

subject of a cult as intercessor for the Russian land.

Information about Sergius’s early life and

much of his later public career comes from the Life

composed by Epifany “the Wise” in 1418 and re-

visions of it by Pakhomy “the Serb” from 1438 to

1459. Baptized Varfolomei, he was the second of

three sons of a boyar family of Rostov. In 1327

and 1328 the Mongols devastated Rostov, ruining

his family. In 1331 Prince Ivan I “Kalita” of Moscow

annexed Rostov and resettled the family in

Radonezh. Varfolomei’s brothers married, but he

remained celibate. When his parents died, he and

elder brother Stefan, a monk since the death of his

wife, went to live as hermits in a nearby “wilder-

ness” in 1342. They built a chapel, dedicated to the

Trinity, and Varfolomei was tonsured as the monk

Sergius. Stefan left for Moscow, where he met the

future Metropolitan Alexei and became confessor

to magnates at court. Sergius lived alone in poverty

two years, sharing food with animals, tormented

SERGIUS, ST.

1369

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

by demons and the devil, an ordeal replicating nar-

ratives of hermit saints of early Christianity. He at-

tracted twelve disciples and in 1353 acceded to their

entreaties and became abbot. Sergius’s example of

humility, manual labor, and disdain for material

things attracted more monks and brought to his

house the support of neighboring peasants and

landowners. While Sergius lived a simple life, and

he and his disciples sought an intense spirituality

resembling that of Hesychast solitaries in Byzan-

tium, there is no evidence that he knew or prac-

ticed formal Hesychast methods of prayer.

Sergius became a historical person when a

source other than his Life recorded that he founded

a monastery at Serpukhov for Prince Vladimir

Andreyevich and baptized Yuri, the second son of

Grand Prince Dmitry I of Moscow, in 1374. Prob-

ably in 1377, at Metropolitan Alexei’s behest and

blessed by Patriarch Philotheos of Constantinople,

Sergius established a cenobite rule at Trinity mod-

eled on the rule of the Studios Monastery in Con-

stantinople. It mandated communal living and

control of property supervised by an elected abbot.

Some monks led by Stefan, who earlier had re-

turned probably expecting to become Trinity’s first

abbot, opposed this. Instead of resisting, Sergius

left. This caused defections and appeals from other

monks at Trinity to Metropolitan Alexei and Grand

Prince Dmitry, who intervened to reaffirm a ceno-

bite rule there and to restore Sergius as abbot.

Sergius’s example inspired a wave of monastic

foundings. He assisted in establishing six houses

and, reportedly, four more. Biographies of at least

seven other founders said their subjects were

Sergius’s disciples or inspired by him. These houses

became engines of agricultural, industrial, and

commercial development, as well as spiritual cen-

ters, contributing to the economic and cultural

integration of the Russian state. In 1422 Abbot

Nikon instituted worship at Trinity of Sergius’s

sanctity and probably originated the story related

by Pakhomy that the Mother of God appeared to

Sergius and put his house under her protection.

According to Pakhomy and later sources, Alexei

and Grand Prince Dmitry wanted Sergius to be met-

ropolitan upon Alexei’s death in 1378, but Sergius

refused. In reality a metropolitan-designate named

Kiprian, installed by Constantinople to assure the

unity of the eparchy in Moscow and Lithuania, was

waiting in Kiev. Also Dmitry and Alexei had a can-

didate, Dmitry’s confessor and former court offi-

cial Mikhail (“Mityai”). Kiprian’s three letters to

Sergius and his nephew Fyodor, requesting or ac-

knowledging their assistance, and other evidence

make clear that Sergius supported his candidacy,

which eventually was successful. The letters cause

some to argue that Sergius, like Fyodor, was

Dmitry’s confessor.

Sergius is most famous as intercessor for

Dmitry’s Russian army that defeated the Mongols

on Kulikovo Field near the Don River in 1380. It

was the first Russian victory over the Mongols, and

Sergius’s intercession was taken to mean that God

favored Russia’s liberation from the Mongol yoke.

Although the earliest text mentioning Sergius’s in-

tercession is Pakhomy’s revision of Sergius’s Life in

1438, the episode became widely accepted, and

Sergius was recognized throughout Russia as a saint

at some point between 1448 and 1450. Thenceforth

SERGIUS, ST.

1370

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

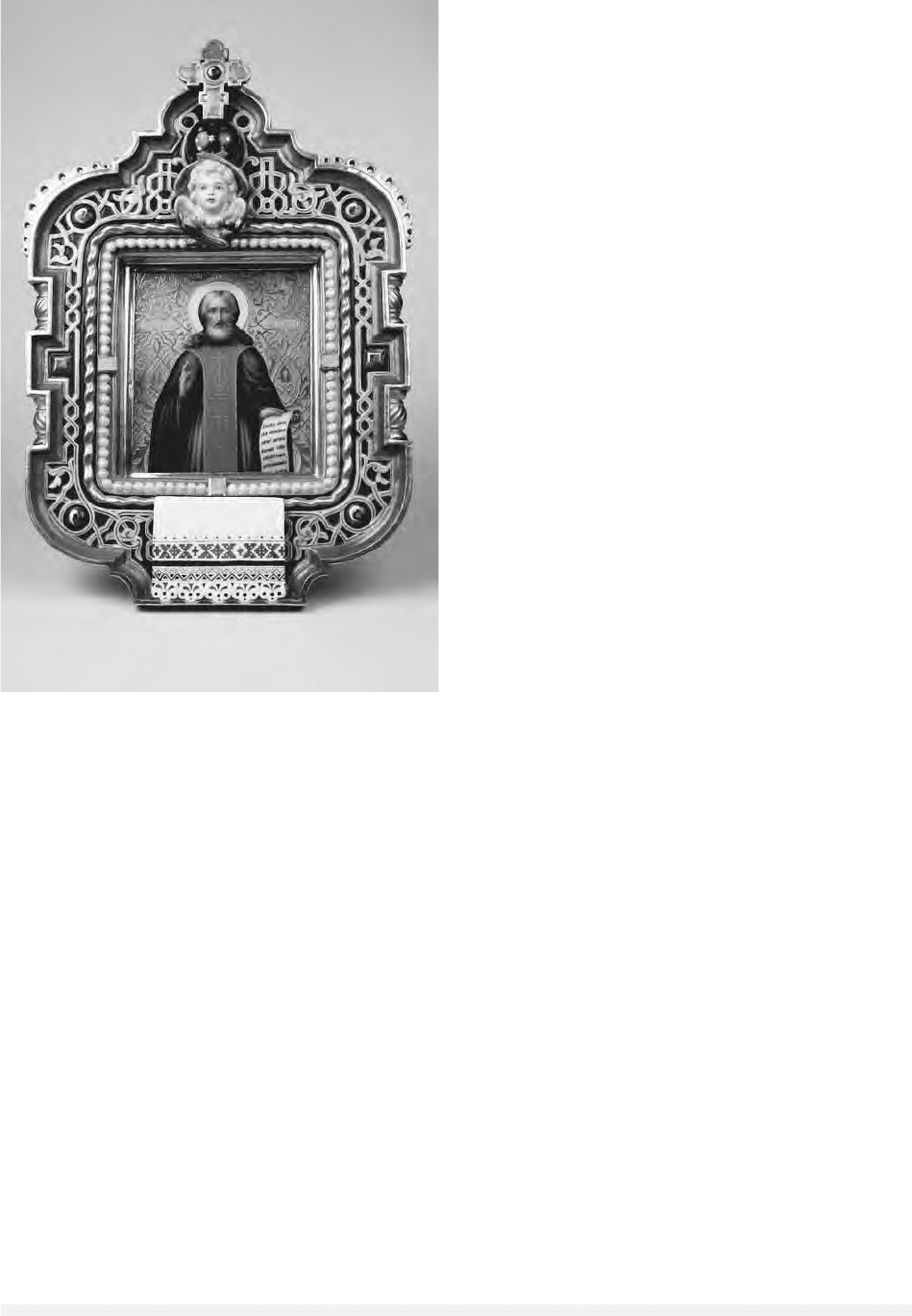

Icon of St. Sergius of Radonezh by Ivan Kholshevnikov.

© R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF THE

S

TATE

H

ERMITAGE

M

USEUM

, S

T

.

P

ETERSBURG

, R

USSIA

/CORBIS

this episode was embellished many times in tales

and histories and gave rise to legends of subsequent

interventions by Sergius against Russia’s enemies.

Sergius remains for many the personification of

Russian exceptionalism. On July 29, 1385, Sergius

baptized Dmitry’s son Pyotr. That same year Dmitry

asked Sergius to reconcile him with Grand Prince

Oleg of Ryazan and to compel Oleg to recognize

Dmitry as his senior, a task he performed success-

fully. A story that Sergius similarly intervened for

Moscow in 1365 in Nizhny Novgorod is probably

apocryphal.

See also: TRINITY ST. SERGIUS MONASTERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fedotov, G. P. (1965). A Treasury of Russian Spirituality.

New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Fedotov, G. P. (1966). The Russian Religious Mind, vol. 2.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Meyendorff, John. (1981). Byzantium and the Rise of Rus-

sia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, David B. (1993). “The Cult of Saint Sergius of

Radonezh and Its Political Uses.” Slavic Review 52:

680–699.

D

AVID

B. M

ILLER

SERVICE STATE

The service state has been the major factor in the

past half millennium of Russian history. It has

saved Russia from foreign conquest by mobilizing

and controlling at crucial moments the basic fac-

tors of the economy—land, labor, and capital. It

has used major ideologies to legitimize itself and

then has proceeded to try to control most areas of

artistic and intellectual life. The service state has

gone through three major phases which may be

described as “service class revolutions” and serve as

classic illustrations of path dependency.

Each service class revolution has been a re-

sponse by Russia’s rulers to perceptions of signifi-

cant military threats from foreign adversaries. The

first can be dated roughly to 1480, when Russia

threw off the Mongol yoke. From then the inde-

pendent state was on its own and faced foreign

threats from various quarters, but the major one

was from Lithuania, the largest state in Europe

with holdings in Vyazma, about 100 miles (160

kilometers) from Moscow. Moscow’s conquest of

the Republic of Novgorod in 1478, the execution

and deportation of its secular and religious elite,

and the annexation of their vast lands created the

opportunity for the creation of a service class, the

backbone of the new service state. The Novgoro-

dian lands were handed out as service landholdings

(pomestie) to provincial cavalrymen for their main-

tenance. These cavalrymen had no independent base

and were totally beholden to Moscow. They were

ranked according to perceived service performance

and compensated accordingly. In exchange for the

pomestie, they had to serve Moscow for life. As

Moscow annexed other territories, it converted

them to pomestie tenure. In time, Moscow had a

corps of 25,000 pomestie cavalrymen at its beck

and call to confront any military emergency. This

method of fielding an army was deemed so effec-

tive that in 1556 the government mobilized all

seignorial land and required estate owners to pro-

vide the army with one fully equipped, outfitted

cavalryman for each 100 cheti (1 chet ⫽ 1

1

/

3

acres)

of populated land.

In 1480 a master ideology was lacking to sup-

port the forming service state, but it did not take

long for one to appear. At the beginning of the six-

teenth century, Joseph, the abbot of Volokolamsk

Monastery, advanced the precept of Agapetos (fl.

527–548) that “in his person the ruler is a man,

but in his authority he is like God.” This conflicted

with the views of Grand Prince Ivan III, who

wanted to annex all church lands and convert them

into pomestie holdings; his son Basil III, who pre-

ferred to let the church continue to own a third of

all the populated land of Russia; and other church-

men who believed that the church should not be

so involved in “the world.” This variation on the

divine right of kings gave the Russian ruler un-

questioned control over everything. The idea

reigned at least until 1905, probably until 1917.

Such military might and autocratic pretensions

needed financial means and bureaucratic coordina-

tion to support them. After 1300 the government

apparatus was part of the Moscow ruler’s house-

hold, but around 1480 specialization began to

develop in the grand princely household adminis-

tration. Around 1550 special chancelleries with

their own record-keeping apparatus began to de-

velop to keep track of the service land fund, the

provincial cavalry, the new infantry arquebusiers

who had been created to complement the cavalry,

and the taxes needed to support these activities. By

SERVICE STATE

1371

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the mid-seventeenth century there were about

forty of these chancelleries, which seemingly were

as efficient and professional as any similar, con-

temporary organs on Earth.

The last element in the construction of the ser-

vice state was the inclusion of the masses. To sup-

port the cavalry, the peasantry was definitively

enserfed between the 1580s and 1649. In an at-

tempt to ensure the stability of the government’s

cash receipts, the townsmen were bound to their

urban places of residence and granted monopolies

on trade and industry and the right to own urban

property. By 1650 the service state was fully

formed. Its completion had been forced by the June

1648 Moscow rebellion against the corrupt regime

of Boris Morozov, which compelled the govern-

ment to convoke the Assembly of the Land, whose

product was the Law Code of 1649.

During the Thirteen Years’ War (1654–1667),

the old military service class’s obsolescence was re-

vealed, and it was replaced by new formation reg-

iments commanded by foreign officers. Yet the old

landed service class retained its privileges and its

monopolies over much of the country’s land and

peasant labor. This proved to be the trajectory of

all service classes: creation, hegemony, decline, and

obsolescence—yet retaining all privileges.

The second service class revolution was the

product of Peter the Great’s perception that Swe-

den’s Charles XII desired to annex Russia. After los-

ing to Charles at Narva in 1700, Peter completely

revitalized the service state. All the surviving mil-

itary servicemen were put back in harness, the

dependency of the serfs on the landowners was

strengthened, the army was reformed, the Table of

Ranks of 1721 told the service state’s agents where

they belonged in the merit-based hierarchy, and the

government apparatus was reformed. The Ortho-

dox Church, which had been created by the state

in 988 and was nearly always the state’s obedient

servant, was converted into a department of the

state government with the creation of the Holy

Synod in 1721. This continued the secularization

of the church administration that had been intro-

duced in 1649 but had been halted when Tsar Alexei

died in 1676. Alexei’s son Peter made the clergy

more active members of the service state by re-

quiring them to report to the police what they

heard in confessions as well as to read government

edicts to the populace from the pulpit.

Peter articulated one of the basic principles of

the service state: anyone was eligible to serve, as

long as he performed the duties demanded of him.

This was absolutely crucial in holding together an

ever-expanding multinational empire. Peter artic-

ulated this in comments about his foreign minis-

ter, Pyotr Shafirov, a Jew, and other Jewish people

in his administration: “I could not care less

whether a man is baptized or circumcised, only

that he knows his business and he distinguishes

himself by probity.” In the perfectly operating ser-

vice state, there was no place for nationalism (such

as Russification) or persecution of national mi-

norities or alien religions (e.g., Jews). Those oc-

curred only at times when the service state was in

decline.

The Petrine service state was very successful

in defeating Sweden and putting Russia’s other

major adversaries—the Rzeczpospolita and the

Crimean Khanate—on the defensive and ultimately

exterminating them. These successes lessened the

demands on the service state, and in 1762 Peter III

freed the gentry land- and serf-owners from com-

pulsory military service. Need for revenue forced

most younger gentry to render military service

anyway.

The other major personnel segment of the ser-

vice state, the peasantry, was not freed in 1762,

and the condition of the seignorial serfs was abased

to the extent that they became akin to slaves by

1800. Defeat during the Crimean War (1853–1856)

did not provoke Russia to initiate another service

class revolution, although a dozen major reforms

were enacted between 1861 and 1874. In 1861 all

seignorial serfs were freed from slavelike depen-

dency on their owners, but were bound instead to

their communes and were allowed to move freely

only in 1906. This largely ended the second service

class revolution, although the autocratic monar-

chy persisted until February 1917.

Certain features of the service state did not die

in 1762, 1861, or even 1906. The government

maintained its pretensions to control all higher cul-

ture by censoring literature, the theater, all art ex-

hibitions, and musical performances. Secret police

surveillance was continuously strengthened as the

government used repression, jailing, and exile in its

attempts to cope with the rising revolutionary

movement opposed to the autocracy and serfdom.

The industrialization of Russia launched by Minis-

ter of Finance Sergei Witte during the 1890s was

a demonstration of service state power reminiscent

of Peter I and anticipating Josef Stalin.

SERVICE STATE

1372

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY